Abstract

We summarize a new approach to neuromodulator detection that provides co-localized detection of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine at sub-second time scales and promises to provide sub-millisecond estimates of the same. The methodology, elastic net electrochemistry, is used to estimate dopamine and serotonin in the striatum of conscious human subjects during active decision-making. We show a proof-of-principle example of the same method working on commercially available depth electrodes in common use for epilepsy monitoring and neurosurgical planning in humans, which further promises to make such electrodes sources of fast neuromodulator information never before available in human subjects. We discuss the implications of this methodology for making direct tests in humans of the computations carried by these three important neuromodulatory systems. The methods also promise great utility in model organisms, but this chapter focuses on the possibilities for human use.

Introduction

Neuromodulatory systems that deliver dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine to target neural regions are crucial for sustaining healthy mental function. Disturbances in these systems by injury or disease underlie a wide range of psychiatric and neurological dysfunction. Over the last two decades, these systems have been the focus of modeling that seeks to understand in computational terms their role in learning, memory, mood and mental disorders. These systems are hypothesized to encode important learning signals about rewards, punishments, and attentional allocation as modulations in their spike rates. In principle, these modulations in spike rate translate into subsequent changes in the downstream delivery of their neuromodulators. As this modeling work progresses into its third decade, it’s important to highlight some critical gaps in our understanding of diffuse neuromodulatory systems that modern methodologies stand poised to surmount. We focus here on two big gaps allowing that there are many others: (1) the neurophysiology of these systems in humans and (2) the feasibility of ultra-fast neuromodulator measurements.

From a neurophysiological and signaling perspective, the vast majority of work on neuromodulatory systems has been in model organisms, which provide fantastically high-precision access and control. The caveat here, however, is in the difficulty of understanding the relationship of model organism behavior – alongside some interesting biological perturbation or measurement - to human behavior. This is simply a hard problem biologically and computationally. This kind of cross species behavior-gap is not easily bridged since it is difficult to know which behavioral primitives in rodents represent homologous behavioral capacities in humans. Moreover, experiments in model organisms must necessarily focus on simple behaviors (approach, avoidance, simple choices), and this leaves out the kind of important abstractions available to humans and that may be perturbed in humans by disease and injury. Human behavioral work – in the healthy and otherwise – brings its own face validity, but at a cost - the methodologies available for neural eavesdropping in humans have simply not been at the same level of granularity available in model systems.

A new inferential approach to fast, selective neuromodulator detection

We have recently developed new approaches that permit fast (sub-second), simultaneous, and co-localized detection of extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine and have extended the use of these tools for use in conscious human subjects (Kishida et al., 2011; Kishida et al., 2016; Moran et al., 2018; also see Platt and Pearson, 2016). Our electrochemical detection approaches require direct access to brain tissue, which in humans can only be gained through piggybacking on clinical procedures requiring neurosurgery. Nevertheless, direct investigation of human brain function is requisite if we are to develop an understanding of how moment- to-moment fluctuations in dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine encode information that affects human behavior, thoughts, and feelings. We review the general approach and its connection to established machine learning techniques and we further point out how these methods can be implemented on electrodes in routine use in model organisms and during neurosurgical planning in humans. These latter implementations have the potential to be transformative for our understanding of the computational underpinnings of neuromodulation (e.g. Dayan, 2012, Sutton and Barto, 2018) because they will make fast neuromodulator detection available using off-the-shelf hardware and software.

Despite the recent revolution in methods to record and induce neural activity, there has been relatively less progress in making dynamic, chemically specific measurements of neurotransmitter fluctuations in the extracellular space. Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry has been the only rapid way to monitor sub-second neurochemical changes in neural tissue (Stamford et al., 1984; Kuhr and Wightman, 1986; Mermet and Gonon, 1986; Stamford, 1990). However, the recent advent of an expressible dopamine sensor (DLIGHT, Patriarchi et al., 2018) should provide a host of new insights in model organisms where such an innovation can be expressed selectively in specific cells types. Cyclic voltammetry has been adapted for use in behaving animals over sufficiently long periods suitable for connecting neuromodulator fluctuations (e.g. typically dopamine) to behavior (Phillips et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 2008; Huffman and Venton, 2009; Clark et al., 2010). The basic approach is to introduce a voltage sweep on a carbon fiber, record the measured currents, and take advantage of the fact that different oxidizable species react on the surface of the carbon fiber at different rates at different voltages. These rates of reaction are time and concentration dependent. In this fashion, the induced current time series potentially carries a ‘signature’ for different important, oxidizable neurotransmitters that can be calibrated against known concentrations. These approaches contain pitfalls because of the potentially adulterating influences of compounds like ascorbate, pH, and other neurotransmitters with nearby oxidation peaks (e.g. norepinephrine versus dopamine) as well as a number of other potential confounds.

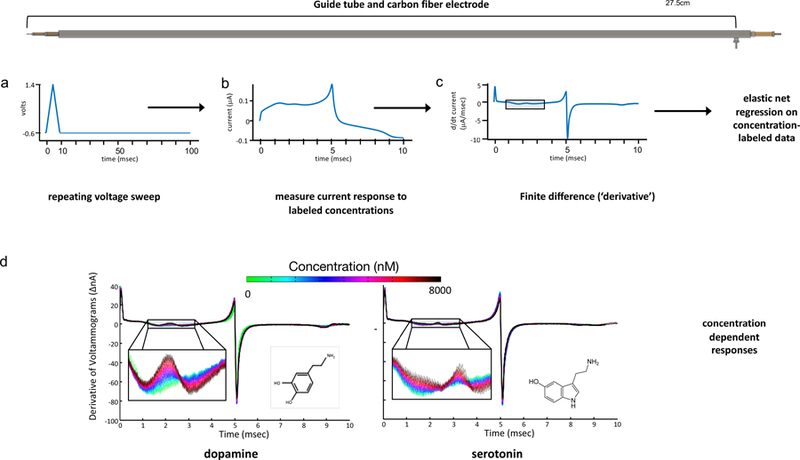

The aim of deploying voltammetric approaches in humans inherits another challenge. In a human subject, because of the risk for contamination, it is not feasible to calibrate sensors beforehand and then introduce the calibrated electrode into the brain. Instead, a model for dopamine-detection must be developed in an in vitro setting and used to infer concentrations on a similar, but distinct electrode to be deployed in vivo. Hence in vitro calibration models must be made stable to known influences such as pH and norepinephrine both of which could confuse a putative dopamine measurement in vivo. The models also must be shown to generalize across electrodes and must be robust to dopamine levels on which the models were not trained. These challenges strongly suggested to us the use of a modern statistical inference method alongside very large training datasets typical for modern machine learning approaches. In our initial work (Kishida et al., 2016; Moran et al., 2018), we retained the voltage sweeps typical of prior fast scan cyclic voltammetry work (here a 10 millisecond triangular sweep followed by a 90 msec waiting period – below we show in experiments that this waiting period is not necessary), but adopted a different approach to extracting a concentration-prediction model. As shown in figure 1, after recording the current time series we computed a finite difference through time (figure 1c) and entered this into an ‘elastic net’ regression (Zou and Hastie, 2005; Kishida et al, 2016) on labeled data (here the ‘label’ is the concentration). Each timestep in the differentiated current time series is entered as an independent predictor. The concentration prediction models were extracted using a standard cross-validation method (‘glmnet.m’ in MATLAB, Qian et al., 2013).

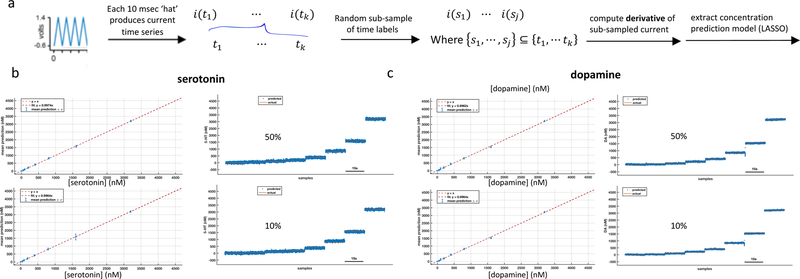

Figure 1. Elastic net electrochemistry.

(Top) Diagram of guide tube used during neurosurgery for DBS electrode implantation. The carbon fiber probe is inserted through guide-tube and the stainless-steel pin at right acts as reference ground. This is the same ground used during training of models from flow cell data. Workflow for elastic net electrochemistry (see Kishida et al., 2016; Moran et al., 2018). a. Voltage waveform on electrode. b. Measured current timeseries during ~10msec triangular waveform portion of the 100 msec duty cycle c. Finite time difference of current. d. Carbon fiber electrode responses to dopamine and serotonin concentrations in format of finite time difference plot. Concentration-specific information about dopamine and serotonin is ‘wiggly’ (and even inverts for dopamine) but this information is not simply concentrated at the theoretical oxidation potentials for both neuromodulators.

One motivation for this approach was that the fact that current responses measured throughout nearly the entire voltammetric cycle provide an excellent encoding of the known analyte concentrations. Traditional analytic approaches focus the development of inference models on a single point in the voltammogram (e.g., typically the oxidation peak), which forces a loss of the information contained in the rest of the voltammetric measurement that is required to determine the chemical species identity. This is illustrated in figure 1d where the color code shows the differentiated currents for different concentrations of dopamine and serotonin. Although each color traces out a ‘wiggly’ line, these concentration-dependent traces remain visibly discriminable throughout almost the entire timeseries between the start and the capacitive transient at 5 msec. The same claim holds for the time series from 5 msec onward (not shown). Thus, information about a particular dopamine or serotonin level is not concentrated solely at the theoretically reported oxidation potential for each, but is instead spread through a relatively broad region of the time series. This is visible for the approximately 2 milliseconds section shown (indicated by the rectangular box in fig 1c), but is present statistically for almost the entire time series. We believed that the highly distributed concentration information had not been exploited in the past, hence, we sought a way to ‘dig out’ a wiggling but coherent representation of each concentration-dependent response.

Specifics of elastic net electrochemistry.

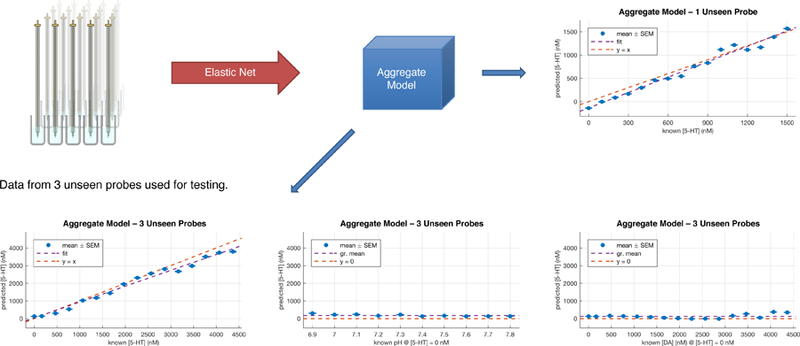

Figure 1a–1c introduces the basic elastic net electrochemistry work flow (Kishida et al., 2016; Moran et al., 2018; also see Kishida et al., 2011). The basic approach is to train a N-fold (in our case, 10-fold) cross-validated recognition model using data collected in a flow cell where mixtures of dopamine, serotonin, and other analytes (or contaminants) can be exactly controlled (and known), and then further validate this model using out-of-sample data in two ways. First, we test our within training set cross-validated models on measurements of dopamine and serotonin not used in building the cross-validated recognition model. Second, we test our models using out-of-probe datasets to show how well it generalizes to measurements made with completely naïve electrodes. Figure 2 shows one example of how a serotonin model generalizes out-of-probe. This figure also shows that the model reports 0 serotonin (when that’s actually the case) and reports no response to pH changes and dopamine changes over a large range. The same basic approach is taken for multi-analyte mixtures (figure 3) and for depth electrodes used for epilepsy monitoring in humans (figure 4).

Figure 2. Out-of-probe and out-of-concentration generalization of elastic net electrochemistry approach.

20 probes’ responses were aggregated to form a composite model for predicting dopamine and serotonin that would not track pH and would generalize well out-of-probe. Single unseen probe predictions versus actual serotonin levels in flow cell (upper right). Aggregate model tested on three unseen probes (bottom row – these plots are averages over responses of the three naïve probes). Here we show the serotonin model matching actual serotonin, not tracking pH, and not tracking dopamine. An average of 20,000 samples per probe were taken (this included 160 different concentration levels) for a grand total of ~ 400,000 samples for the entire 20- probe aggregate. The model so-extracted generalizes well out-of-probe and out-of-sample (the concentrations in these plots are out-of-sample).

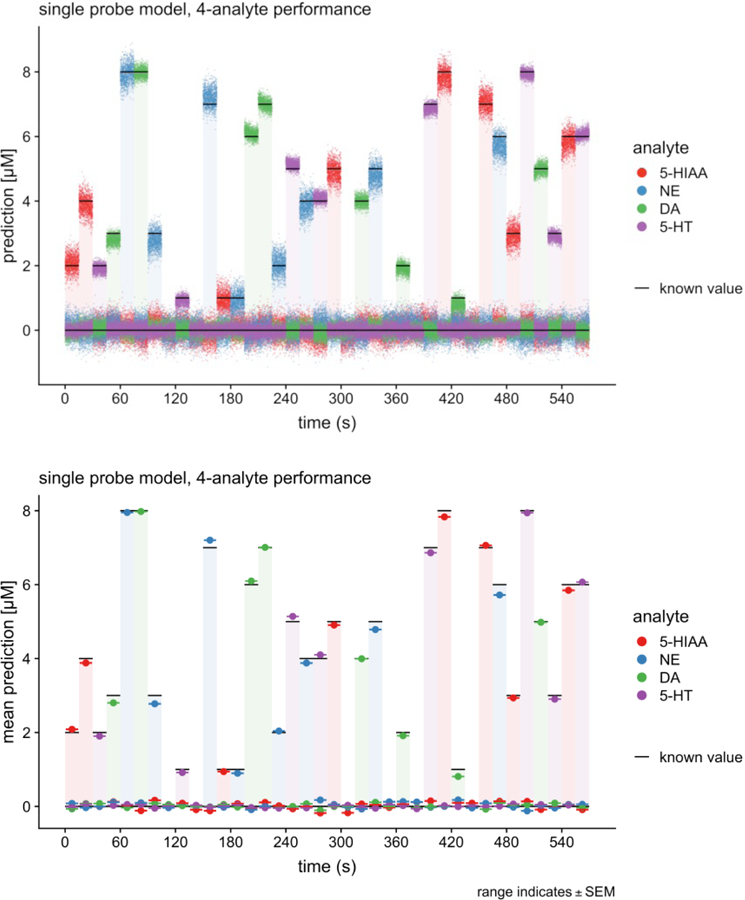

Figure 3. Four analyte model performance at ~10 milliseconds per estimate.

(top) Moment-to-moment predictions (10.3 msec per estimate (97Hz) ) of 4 analyte model extracted by elastic net from a 4 analyte mixture in a flow cell. (Bottom) Average performance of 4 analyte model. Notice the model can also separate serotonin from 5-hydroxy-indole-acetic acid. Carbon fiber electrode.

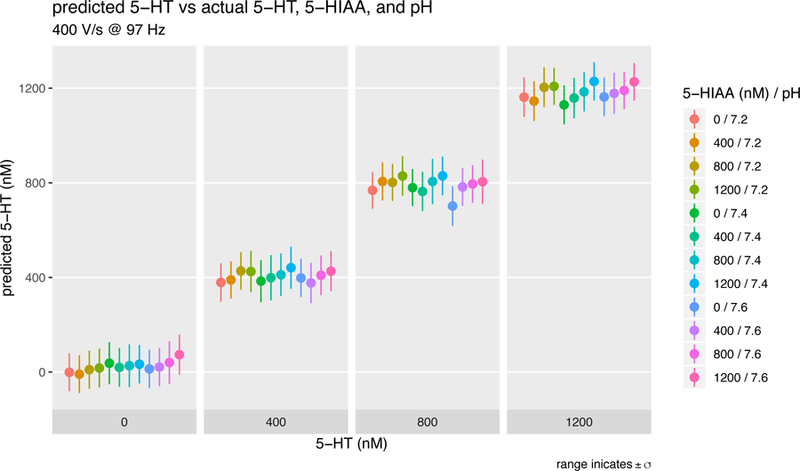

Figure 4. Serotonin model performance versus pH and 5HIAA (10.3 msec per estimate).

A 3-analyte model was trained to predict serotonin concentration in the context of varying pH and varying concentration of 5-HIAA, a known metabolite of serotonin that confuses prior voltammetric inference methods. From left to right, serotonin concentration prediction are stable against a background of increasing pH or increasing 5-HIAA concentration.

For purposes of discussion, here we focus the description of our approach on detecting dopamine, but the sample basic principles apply to generating multi-analyte models (like those shown in Figures 3–6). To fit a model using known concentrations of dopamine in the context of varying pH, we use the “elastic net” to perform regularization and automatic variable selection to determine a good fit for a linear regression model, that predicts the concentration of dopamine (y) given a fast-scan cyclic voltammetry measurement. Note, one fast-scan cyclic voltammetry measurement is equal to the current measured during the application of a 10 msec triangular voltage sweep as indicated in figure 1a followed by a 90 msec ‘wait period’ for total of a 100 msec duty cycle. Here, we aim to esimate ““ the predicted concentration of dopamine for each 100 msec cycle (fig 1a) given the vector of parameters, , which is the finite time derivative (‘dI/dt’) of a single cyclic voltammogram measurement. The betas are regression weights. The elastic net procedure for linear regression models minimizes the residual sum of squares with an additional penalty term, Pα(β). The elastic net penalty is a mixture (convex hull) of the ‘ridge regression penalty’ ( (Hoerl and Kennard, 1970)) and ‘lasso penalty’ , (Tibshirani, 1996)) parameterized by α, which takes a value between 0 and 1. To determine a best-fit linear regression model, we collect voltammetric measurements from samples of known concentrations of analyte in vitro and perform 10- fold cross-validation prior to further vaildating model performance on out-of-sample test cases (Kishida et al., 2016).

Figure 6. Evidence that 1 millisecond of data is sufficient for elastic net electrochemistry to extract a concentration prediction model.

a. Triangular voltage wave repeating at ~10 milliseconds is randomly down- sampled respectively at 50% and 10%, derivative of the sub-sampled current time series is computed, and as above this ‘derivative’ is entered into an elastic net regression to extract dopamine and serotonin prediction models. Note that the randomly chosen points while ordered in time will not be contiguous at the base sampling rate – nevertheless, the prediction models remain excellent. The plots in b and c show out-of-sample predictions for the mixtures averaged for two out-of-sample probes.

In one sense, our approach is not remarkable - we use off-the-shelf voltage clamp hardware (Molecular Devices) and off-the-shelf software (elastic net through calls to the glmnet toolbox in MATLAB). The model building approach, going from big data to a well-behaved models utilizes standard principles in statistical learning methods. However, one major departure from prior voltammetric inference methods is that we train on large data sets (e.g. 400,000 sweeps and hundreds of concentrations) and across many electrodes (figure 2 shows model extracted across recordings from 20 electrodes). Further, no experimenter judgement is necessary regardiung the shape of the voltammogram – with large amounts of data the non-specific variability in these responses is regressed out of the resulting model. In building models this way, we believe we have provided a path to standardization of these approaches in that we have removed the experimenter judgement bias that is implicit in standard voltmammetric inference methods. What bias remains, importantly, is reportable in that all of the bias resides in the calibration datasets used to train a given model. This allows re-interrogation of existing data and a scientific approach to identifying features that improve or degrade the precision of new models.

Elastic net electrochemistry on multi-analyte mixtures and common electrodes

A major challenge for recording dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine concurrently is the selectivity of the extracted models. That is, the goal of any inference method is to determine models that predict out-of-sample measurement of analyte mixtures (e.g., dopamine and serotonin), distinguish th analytes from one another, and distinguish them from other compounds that could confuse the measurements (e.g., norepinephrine, pH, and 5- hyrdoxy-indole-acetic acid). Figure 3 shows just such a separation (at 10.3 msec per estimate where the 90 msec ‘waiting period’ from figure 1a has been dropped). These measeurements were made in a flow cell where the concentrations of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, 5HIAA were controlled exactly. The top panel in figure 3 shows moment-by-moment predictions of the model (at 10 msec resolution) and the bottom panel shows the average value of these predictions for each known concentration. Figure 4 shows the elastic net extracted 5HT model prediction as a function of contaminating pH and 5HIAA concentrations (again, 10.3 msec per estimate as in figure 3).

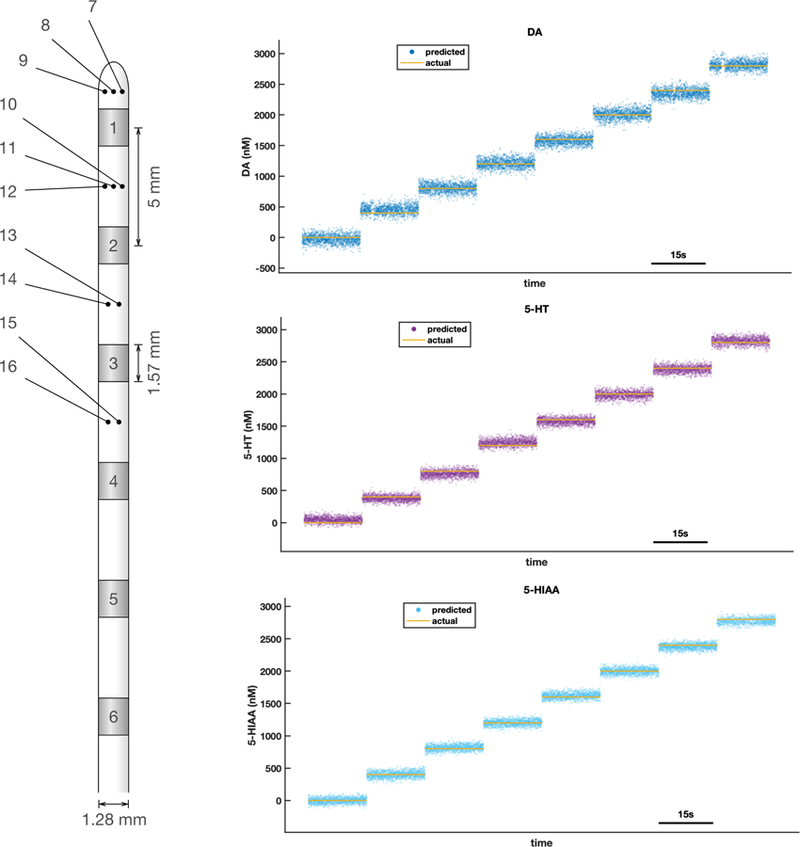

Figure 5 shows predictions of a dopamine, serotonin, and 5HIAA model extracted using an AdTech™ electrode used for stereo-EEG recording in humans. As noted in the figure legend, the models were extracted for the micro-contacts as indicated. These estimates are at 10.3 milliseconds per estimate (~97Hz) similar to the results reported in figures 2,3. These electrodes are just one example of platinum-iridium electrodes in common use in humans and similar electrodes in common use in model organisms. For model organisms, these methods open up many possibilities for neuromodulator recordings, but for humans they could transform any platinum-iridium contact (within an appropriate impedance range) into a source of fast neurochemical information about dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and even the oxidative metabolite of serotonin, 5HIAA. This kind of information could be used in a host of cognitive paradigms, sleep, or changes in consciousness to extract their dependence on these important neuromodulators.

Figure 5. Elastic net electrochemistry models on human electrophysiology electrodes.

3 analyte model on an AdTech™ human depth electrode with low impedance macro- and high impedance micro- contacts. Cartoon at left shows electrode configuration. Microcontacts are distributed radially (and uniformly), but shown here as small dots indicating number of contacts at each location. These data (shown to the right) are from a model extracted in a flow cell using contacts 7 and 10. Each colored dot (labelled prediction in each panel) is a prediction for each 10.3 millisecond bin. Here a triplet mixture of dopamine, serotonin, and 5HIAA is used. All predictions shown here are made from measurements not used in training the model.

Figure 6 suggests that the fast information at 10.3 milliseconds per sample (figures 2,3,4) could be reduced to the order of a millisecond or even faster. This latter possibility would put these measurements on the same order of magnitude as action potentials and modulations in their rate, which would make these neuromodulator measurements capable of tracking changes in spiking rates thought to carry prediction error signals to target neural structures. Figure 6a illustrates the impetus supporting the idea that order-millisecond estimates are possible. Here, the 10 msec triangular voltage waveform is sub-sampled at random, using only 50% of the points in the measured time series, a finite time difference is computed across the remaining downsampled data (here it’s actually a finite index difference since consecutive points are not necessarily contiguous in time), and this ‘time’ difference is used to fit an elastic net regression basde concentration-prediction model. As shown, this procedure works well at 50% and 10% downsampling. The predictions shown are out-of-sample concentration estimates, but generalization to naïve probes for such downsampling awaits future experiments.

Applications of elastic net electrochemistry in human striatum during active investment game

We have presented a summary of an approach to electrochemical detection that makes possible the co-localized detection of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin from both carbon fibers and high-impedance platinum-iridium electrodes that are in routine clinical use around the world. These technical developments open up the possibility of using human subjects where neuromodulator recordings at 10 milliseconds or better could be paired with quantitative behavioral estimates and using electrodes put in place for other reasons (currently clinical reasons). These same methodologies also offer promise for model organism research and should be very useful in calibrating new expressible optical sensors for neuromodulators – for example, the new and exciting DLIGHT reporter for dopamine (Patriarchi et al., 2018). Notably, simultaneous multi-analyte detection does not currently seem to be feasible using receptor based optogenetic methods suggesting complimentary, but distinct, roles for high-speed electrochemical detection methods alongside rapidly developing optogenetic approaches.

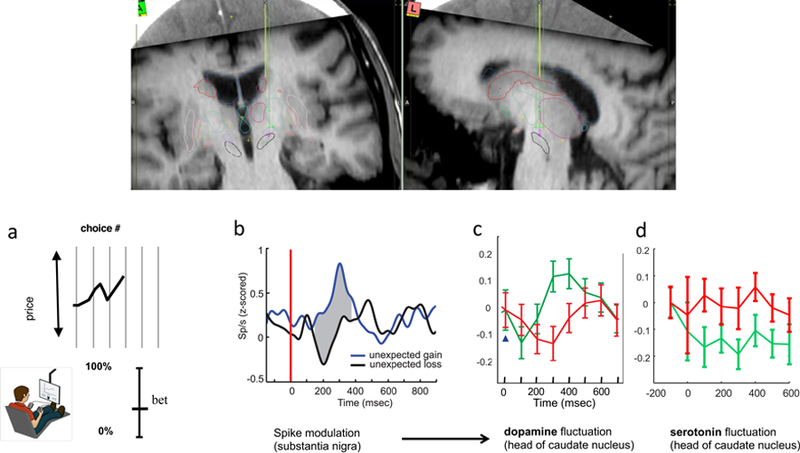

Using carbon fiber microelectrodes and the opportunity afforded by deep brain stimulating (DBS) electrode implantation in humans (for Parkinson’s Disease or Essential Tremors), elastic net electrochemistry has been carried out in conscious human subjects during the execution of a simple investment game (Kishida et al., 2016; Moran et al., 2018; also see Platt and Pearson for commentary). This game is cartooned in figure 7a. Subjects are endowed with 100 dollars, and presented with a market trace, they invest between 0% and 100% of their holdings, the market fluctuates, and they experience a gain or loss. This repeats for 20 rounds for each market. The surgical patients practiced this game prior to surgery. In the surgical suite, subjects played 6 markets (Lohrenz et al., 2007 for BOLD imaging on this task; Kishida et al., 2016 for dopamine recordings in caudate on this task; Moran et al., 2018 for serotonin recordings in caudate during this task).

Figure 7. Application of elastic net electrochemistry in human striatum during investment game.

Top inset shows placement of an electrochemical sensor in the caudate during a DBS electrode implantation procedure for a patient with Parkinson’s disease. The electrochemical sensor (see Figure 1, top) follows the yellow path prior to functional mapping of the eventual DBS electrode path (green path terminating in purple cross in left panel). a. market investment task (Lohrenz et al, 2012; Kishida et al., 2016; Moran et al, 2018); b. reward prediction errors during a simple card game encoded in spike modulation in human substantia nigra (Zaghoul et al., 2009). c. sub-second dopamine release in the caudate encode reward prediction errors during investment task when investments are 100% of participants portfolio Kishida et al., 2016. d. sub-second serotonin release encodes an opponent signal to dopamine release for reward prediction errors (Moran et al, 2018) in the same task events as in panel c.

For Parkinson’s patients, this is a very engaging task, which is important, since subjects off their dopamine precursor medication fatigue quickly. One basic finding that comports with extant data from human single unit recordings in substantia nigra is that for high bets or bets ‘all in’, changes in dopamine delivery to the caudate encode positive prediction errors as positive-going transients (fig 7c) and negative reward prediction errors as negative-going transients (fig 7c). Using a slightly modified version of elastic net electrochemistry, Moran and colleagues (2018) showed an opponent pattern to serotonin fluctuations in human caudate nucleus (from same carbon fiber that recorded the dopamine transients) – positive going serotonin transients encoded negative reward prediction errors and negative going transients encoded positive reward prediction errors. This task is designed to ask how on a fixed budget subjects allocate their money with the amount ‘not risked in the market’ remaining in their pocket. Together, these data are the first sub-second recordings of either dopamine or serotonin in human subjects and the first clear sub-second report of such opponent encodings.

DISCUSSION

We have presented a new approach to the selective detection of biogenic amines that springboards off work in fast scan cyclic voltammetry on carbon fiber electrodes, but apparently exploits a feature of the current time series data that had not been targeted by previous approaches. We highlight this feature - that information encoding specific concentrations of dopamine and serotonin is distributed coherently throughout the electrochemical current time series. We showed how this information can be easily exploited by a modern machine learning method – the elastic net – to extract a concentration prediction model for multiple analytes that include dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. This was accomplished with off-the-shelf hardware and software, which we believe warrants the coupling of other, perhaps more sophisticated inference approaches, to similar electrochemical approaches. These methodological steps forward and their standardization open up the possibility of testing important hypotheses about dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine function at order millisecond time scales and in human brains (our focus in this paper).

We presented an array of experiments supporting the separation of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine from one another and from pH and at least one oxidative metabolite of serotonin, 5 hydroxy-indole-acetic acid. These models were extracted in flow cell environment by comparison to a stainless-steel ground capable of being used in human beings and we reviewed one application of the approach to dopamine and serotonin detection in the striatum of conscious humans (Kishida et al., 2016; Moran et al., 2018). We also showed a preliminary model extracted similarly from a commercially available epilepsy electrode in routine use in human depth electrode monitoring suggesting that such depth electrodes could become sources of (potentially) ultra- fast neurochemical information about dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and perhaps other oxidizable species. This exciting use of the approach has the potential to provide new information about neuromodulatory function in humans and invites similar work in model organisms where a flexible method for their co-localized recording has been lacking.

Lastly, we showed through a randomized down-sampling procedure that order-millisecond or better estimates were possible using elastic net electrochemistry (figure 6). This demonstration suggests that a random 10% of the points collected during the ~10msec triangular sweep contains sufficient information to estimate a reasonably accurate out-of-sample predictive model for both dopamine and serotonin. In figure 6, there are 1000 time points defining the triangular waveform (the voltage forcing function), which means the 10% case is only 100 random points spread throughout the ~10msec duty cycle. These data are not yet definitive since one needs to test these kinds of manipulations out-of-probe on naïve electrodes after training on a group of electrodes; however, it suggests that there is only a loose dependence of the models on the time ordering of the points and even on the voltage. These two observations together suggest radically different approaches might also be possible, but those await future experiments.

Testing the reward prediction error hypothesis throughout human brain

Dopamine signaling in the human brain represents a crucial physical substrate that supports motivated learning (Wise, 2004; Bromberg-Martin, et al., 2010), value-dependent action choice (Montague, et al., 2004), working memory (Cools, et al., 2011), motor learning (Graybiel, 1995) and a variety of other cognitive functions. Consequently, perturbed dopamine signalling plays a major, but complicated role in a range of conditions including drug addiction and Parkinson’s Disease. Despite the importance of dopamine signalling in human mental function, there has previously been no method to gain access to ongoing fast changes (sub-second) in dopamine delivery in the human brain.

As presented here, elastic net electrochemistry addresses this gap in our understanding of dopamine signaling by implementing a new methodology for recording ultrafast (potentially order millisecond) dopamine fluctuations on standard electrodes used in human electrophysiological recordings and using this methodology to test an influential computational model of reward learning: the temporal-difference (TD) reward prediction error hypothesis for dopamine (Glimcher, 2011; Dayan, 2012; Platt and Pearson, 2016; also see Montague et al., 1993, 1994, 1995,1996, 2004, 2006; Schultz et al., 1997; Tobler et al., 2005; O’Doherty et al., 2003, 2004; McClure et al., 2003).

What is the reward prediction error hypothesis for dopamine? To quote Michael Platt and John Pearson (2016),

“Dopamine encodes a key variable posited by theories of reinforcement learning. These theories posit that animals select behaviors on the basis of which ones they expect to result in reward, updating their beliefs on the difference between expectations and observed outcomes, good or bad (3). This reward prediction error is large when rewards are unexpected and small when rewards are fully predicted, and its magnitude and sign drive the speed and direction of learning, respectively.” (also see Glimcher, 2011; Bayer and Glimcher, 2005; Montague et al., 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2004, 2006; Schultz et al., 1997; Dayan and Niv, 2008; Dayan and Daw, 2008; Dayan, 2012).

This model has been tested in non-human primates at the level of spiking activity in midbrain dopamine neurons (e.g. Hollerman and Schultz, 1998; Tobler et al., 2005; also see Schultz, 2015 for review). However, in human and non-human primates, the hypothesis has never been tested in terms of fast changes in dopamine delivery – this is a central gap in our understanding of reward learning in humans and its contribution to important features of human health.

A number of health disorders in humans involve changes in reward processing, value-based decision-making, and reward learning. These include (but are not limited to) substance use disorders (Bickel and Marsch, 2001; Chiu et al., 2008; Gu et al., 2015), psychosis (Sevy et al., 2007), anxiety disorders (Casada & Roache, 2005; Jovanovic et al., 2010; Tolin et al., 2003) and mood disorders (Pizzagalli, 2014; also see Beevers et al., 2013; Chase et al., 2010; Chiu et al., 2007; Gradin et al., 2011; Greenberg et al., 2015; Huys et al., 2008, 2013; Kumar et al., 2008; Kunisato et al., 2012; Rothkirch et al., 2017). Consequently, a central question arises for human health: How does sub-second dopamine delivery conform to the reward prediction error hypothesis? In humans, a clear answer to this question and its dependence on the target neural region would represent a major step forward in our understanding of dopamine’s role in neural processing and hence its potential contributions to diminished human health.

In humans, there is one experiment (a card game) showing clearly that spiking activity in neurons in substantia nigra changes according to a simple prediction error signal (Figure 7b; Zaghoul et al., 2009); however, there has been no direct assessment of the ‘other end of the problem’ in neural structures where dopaminergic neurons project. So the question arises, “Do measured fluctuations in dopamine delivery actually encode reward prediction error signals in human brain?”. The new methodological approaches presented here will allow these questions to be asked and allow them to be answered with selectivity, that is, separating dopamine from serotonin and norepinephrine. As for specific behavioral experiments designed around serotonin and norepinephrine delivery, those are far too numerous to list here.

REFERENCES

- Bayer HM, & Glimcher PW (2005). Midbrain dopamine neurons encode a quantitative reward prediction error signal. Neuron, 47(1), 129–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Worthy DA, Gorlick MA, Nix B, Chotibut T, Todd Maddox W. Influence of depression symptoms on history-independent reward and punishment processing. Psychiatry Res 2013. May 15; 207(1–2): 53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: Delay discounting processes. Addiction 2001. January; 96(1): 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Dopamine in motivational control: Rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuron 2010. December 9; 68(5): 815–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casada JH, Roache JD. Behavioral inhibition and activation in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2005. February; 193(2): 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase HW, Frank MJ, Michael A, Bullmore ET, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Approach and avoidance learning in patients with major depression and healthy controls: Relation to anhedonia. Psychol Med 2010. March; 40(3): 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu PH, Deldin PJ. Neural evidence for enhanced error detection in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2007. April; 164(4): 608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, D’Esposito M. Inverted-U-shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biol Psychiatry 2011. June 15; 69(12): e113–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JJ, Sandberg SG, Wanat MJ, Gan JO, Horne EA, Hart AS, Akers CA, Parker JG, Willuhn I, Martinez V, Evans SB, Stella N, Phillips PE. Chronic microsensors for longitudinal, subsecond dopamine detection in behaving animals. Nat Methods 2010. February; 7(2): 126–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P, Daw ND. Decision theory, reinforcement learning, and the brain. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2008. December; 8(4): 429–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P, Niv Y. Reinforcement learning: The good, the bad and the ugly. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2008. April; 18(2): 185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P Twenty-five lessons from computational neuromodulation. Neuron 2012. October 4; 76(1): 240–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glimcher PW. Understanding dopamine and reinforcement learning: The dopamine reward prediction error hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011. September 13; 108 Suppl 3: 15647–15654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradin VB, Kumar P, Waiter G, Ahearn T, Stickle C, Milders M, Reid I, Hall J, Steele JD. Expected value and prediction error abnormalities in depression and schizophrenia. Brain 2011. June; 134(Pt 6): 1751–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM. Building action repertoires: Memory and learning functions of the basal ganglia. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1995. December; 5(6): 733–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg T, Chase HW, Almeida JR, Stiffler R, Zevallos CR, Aslam HA, et al. (2015) Moderation of the relationship between reward expectancy and prediction error-related ventral striatal reactivity by anhedonia in unmedicated major depressive disorder: Findings from the EMBARC study. Am J Psychiatry, 172, 881–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerl AE, & Kennard RW (1970). Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics, 12(1), 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hollerman JR, Schultz W. Dopamine neurons report an error in the temporal prediction of reward during learning. Nat Neurosci 1998. August; 1(4): 304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman ML, Venton BJ. Carbon-fiber microelectrodes for in vivo applications. Analyst 2009. January; 134(1): 18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huys QJ, Pizzagalli DA, Bogdan R, Dayan P. Mapping anhedonia onto reinforcement learning: A behavioural meta-analysis. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord 2013. June 19; 3(1): 12–5380-3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic T, Norrholm SD, Blanding NQ, Davis M, Duncan E, Bradley B, Ressler KJ. (2010) Impaired fear inhibition is a biomarker of PTSD but not depression. Depress Anxiety, 27, 244–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida KT, Sandberg SG, Lohrenz T, Comair YG, Saez I, Phillips PE, Montague PR. Sub-second dopamine detection in human striatum. PLoS One 2011; 6(8): e23291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida KT, Saez I, Lohrenz T, Witcher MR, Laxton AW, Tatter SB, White JP, Ellis TL, Phillips PE, Montague PR. Subsecond dopamine fluctuations in human striatum encode superposed error signals about actual and counterfactual reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016. January 5; 113(1): 200–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhr WG & Wightman RM. Real-time measurement of dopamine release in rat brain. Brain Res 1986; 381, 168–171. 1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Waiter G, Ahearn T, Milders M, Reid I, Steele JD. (2008) Abnormal temporal difference reward-learning signals in major depression. Brain, 131, 2084–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunisato Y, Okamoto Y, Ueda K, Onoda K, Okada G, Yoshimura S, Suzuki S, Samejima K, Yamawaki S. Effects of depression on reward-based decision making and variability of action in probabilistic learning. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2012. December; 43(4): 1088–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohrenz T, McCabe K, Camerer CF, Montague PR. Neural signature of fictive learning signals in a sequential investment task. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007. May 29; 104(22): 9493–9498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, Berns GS & Montague PR Temporal prediction errors in a passive learning task activate human striatum. Neuron 2003. 38(2): 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermet C & Gonon F In vivo voltammetric monitoring of noradrenaline release and catecholamine metabolism in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Neuroscience 1986; 19, 829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Dayan P, Nowlan SJ, Pouget A, Sejnowski TJ. Using aperiodic reinforcement for direct self-organization. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 5 SanMateo, CA: Morgan Kauffman Publishers; 1993. p. 969–976. [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR & Sejnowski TJ (1994) The predictive brain: Temporal coincidence and temporal order in synaptic learning mechanisms. Learn Mem 1(1): 1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Dayan P, Person C, Sejnowski TJ. Bee foraging in uncertain environments using predictive hebbian learning. Nature 1995. October 26; 377(6551): 725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Dayan P, Sejnowski TJ. A framework for mesencephalic dopamine systems based on predictive hebbian learning. J Neurosci 1996. March 1, 1996; 16(5): 1936–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Hyman SE, Cohen JD. Computational roles for dopamine in behavioural control. Nature 2004. October 14; 431(7010): 760–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, King-Casas B, Cohen JD. Imaging valuation models in human choice. Annu Rev Neurosci 2006; 29: 417–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran RJ, Kishida KT, Lohrenz T, Saez I, Laxton AW, Witcher MR, Tatter SB, Ellis TL, Phillips PE, Dayan P, Montague PR. The protective action encoding of serotonin transients in the human brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018. May; 43(6): 1425–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JP, Dayan P, Friston K, Critchley H & Dolan RJ Temporal difference models and reward-related learning in the human brain. Neuron 2003. 38(2): 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty J, Dayan P, Schultz J, Deichmann R, Friston K, Dolan RJ. Dissociable roles of ventral and dorsal striatum in instrumental conditioning. Science 2004. April 16; 304(5669): 452–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patriarchi T, Cho JR, Merten K, Howe MW, Marley A, Xiong WH, Folk RW, Broussard GJ, Liang R, Jang MJ, Zhong H, Dombeck D, von Zastrow M, Nimmerjahn A, Gradinaru V, Williams JT, Tian L. Ultrafast neuronal imaging of dopamine dynamics with designed genetically encoded sensors. Science 2018. June 29; 360(6396): 10.1126/science.aat4422. Epub 2018 May 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PE, Stuber GD, Heien ML, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Subsecond dopamine release promotes cocaine seeking. Nature 2003. April 10; 422(6932): 614–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA. Depression, stress, and anhedonia: Toward a synthesis and integrated model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2014; 10: 393–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt ML, Pearson JM. Dopamine: Context and counterfactuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016. January 5; 113(1): 22–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Hastie T, Friedman J, Tibshirani R and Simon N (2013) Glmnet for Matlab http://www.stanford.edu/~hastie/glmnet_matlab/

- Robinson DL, Hermans A, Seipel AT, Wightman RM. Monitoring rapid chemical communication in the brain. Chemical reviews 2008; 108:2554–2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothkirch M, Tonn J, Kohler S, Sterzer P. Neural mechanisms of reinforcement learning in unmedicated patients with major depressive disorder. Brain 2017. April 1; 140(4): 1147–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamford JA, Kruk ZL, Millar J & Wightman RM Striatal dopamine uptake in the rat: in vivo analysis by fast cyclic voltammetry. Neurosci. Lett 1984; 51, 133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamford JA Fast cyclic voltammetry: measuring transmitter release in ‘real time’. J. Neurosci. Methods 1990; 34, 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1996; 267–288.

- Tobler PN, Fiorillo CD, Schultz W. Adaptive coding of reward value by dopamine neurons. Science 2005. March 11; 307(5715): 1642–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Carelli RM, Wightman RM. Phasic dopamine signals: From subjective reward value to formal economic utility. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2015. October; 5: 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 1997. March 14, 1997; 275(5306): 1593–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevy S, Burdick KE, Visweswaraiah H, Abdelmessih S, Lukin M, Yechiam E, Bechara A. Iowa gambling task in schizophrenia: A review and new data in patients with schizophrenia and co-occurring cannabis use disorders. Schizophr Res 2007. May; 92(1–3): 74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton RS and Barto AG (2018) Reinforcement learning: an introduction, (MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.) [Google Scholar]

- Tobler PN, Fiorillo CD, Schultz W. Adaptive coding of reward value by dopamine neurons. Science 2005. March 11; 307(5715): 1642–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Abramowitz JS, Brigidi BD, Foa EB. Intolerance of uncertainty in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord 2003; 17(2): 233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci 2004. June; 5(6): 483–494. 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaghloul KA, Blanco JA, Weidemann CT, McGill K, Jaggi JL, Baltuch GH, Kahana MJ. Human substantia nigra neurons encode unexpected financial rewards. Science 2009. March 13; 323(5920): 1496–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H and Hastie T Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2005; 67, 301–320. [Google Scholar]