Abstract

Background

An assessment of trends in lung cancer patient survival is very important to determine the outcomes and to modulate where advancements should be made. This study investigated whether the absolute lymphocyte count just after chemoradiation (after-ALC) and 3 months after chemoradiation initiation (post-ALC) could predict limited-stage small cell lung cancer (LS-SCLC) patients’ clinical outcomes.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 304 patients who were newly diagnosed with LS-SCLC and received treatment with chemoradiation (CRT). Finally we collected data at the time of pretreatment, after-ALC and post-ALC from 226 patients. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank statistics were used to assess the prognostic significance of after-ALC and post-ALC for survival rates. Cox proportional hazards models were used to generate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Two hundred and twenty-six patients had a documented ALC pretreatment, just after CRT and 3 months after CRT. Relative lymphopenia of pre-treatment ALC was in 47.8% of patients, whereas the lymphopenia (<655 cells/mm3) proportion was increased to 61.1% just after CRT, and the lymphopenia (<1,430 cells/mm3) proportion continued to rise to 70.4% at the time of 3 months after initiating CRT. After-ALC lymphopenia patients showed inferior median OS (18.1 vs. 36.0 months, P<0.001) and similar PFS (9.7 vs. 26.2 months, P<0.001) compared to patients without lymphopenia. Multivariate analysis demonstrated after-ALC <655 cells/mm3 and post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3 (HR: 1.339; P=0.038) had a 105% and 33% (HR: 2.056; P<0.001) increase in hazards of death respectively. Similarly, after-ALC <655 cells/mm3 and post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3 had a 160% (HR: 2.606; P=0.002) and 40% (HR: 1.409; P=0.015) increase in hazards of progression respectively. Furthermore, hyperfractionated RT showed more likely to cause lymphopenia in patients than conventional fractionated RT.

Conclusions

Nearly half of LS-SCLC patients treatment with CRT experienced severe lymphopenia and more than half patients exhibited prolonged lymphopenia. Statistical significance that lymphopenia after treatment was associated with decreased survival was obviously observed. Further study is warranted, given that explanation lymphopenia is a mechanism for shorter survival or just a predictor.

Keywords: Limited-stage small cell lung cancer (LS-SCLC); radiotherapy (RT); chemoradiation therapy (CRT); accelerated hyperfractionation, lymphopenia; absolute lymphocyte count (ALC)

Introduction

In world wide, lung cancer accounts for more deaths than any other cancers. And small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for approximately 15–20% of all lung cancers (1,2). The median survival time for limited-stage and extensive-stage of SCLC is 15–20 and 8–13 months respectively (3). Studies in referring to exploring effective predictive indicators that were associated with clinical outcomes were never stopped (4). According to immunoediting theory, the crosstalk between immune system and tumor cells plays a critical role in tumor control and immunotherapy indicates that a pool of functioning lymphocytes was critical for tumor surveillance (5). Several studies have demonstrated tumor infiltration by white blood cells, particularly lymphocytes, has favorable clinical outcomes than patients without this phenomenon (6-9). Multiple studies reported pre-treatment lymphopenia was associated with poor survival in several types of advanced cancers (10).

We focused that the conventional recognition radiation destroyed DNA double helix structure of tumor cells and induced them apoptosis. While the advent of immunotherapy has renewed the cognization radiotherapy (RT) actually serves as a double-edged sword on the immune system. Yovino et al. found after 30 conventional fractions of 2 Gy RT, the circulating lymphocytes received 2.2 Gy mean dose and 99% of circulating lymphocytes received ≥0.5 Gy (11). Thus, the potential correlation between RT induced lymphopenia and cancer patients’ clinical outcomes needs to be elucidated. Several studies have demonstrated RT, regardless of concurrent chemotherapy, induce lymphopenia which could predict poor OS and PFS in glioma, nasopharyngeal cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cervical cancer (12-24). However, whether CRT induced lymphopenia is predictive of SCLC patients’ outcomes is rarely reported.

In this study, we examined the relationship between ALC after CRT, ALC 3 months after CRT and clinical outcomes in LS-SCLC.

Methods

Patient selection

After obtaining approval (ID: SDZLEC2016-001-01) from the ethics Review Board, 226 patients with LS-SCLC treated with CRT from 2006 through 2013 were identified. 226 patients met the following inclusion criterias: (I) biopsy-confirmed SCLC; (II) stage LS-SCLC; (III) initial treatment administered at our hospital (concurrent CRT or sequential CRT); (IV) absolute lymphocyte count of pre-treatment, just after CRT and 3-month after CRT were available. The standard treatment regimen at our hospital is to administer four to six cycles of platinum chemotherapy concurrently or sequentially with accelerated hyperfractionated RT or conventional fractionated RT.

Data collection

The clinical baseline data of patients’ characteristics including demographics, smoking habits, Karnofsky performance status, inflammation situation, chemotherapy regimen, and radiation modes were obtained from the electronic medical record system of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute. Besides this, hemoglobin, albumin, lactate dehydrogenase, and alkaline phosphatase were evaluated at diagnosis. Data from ALC were collected from three time points including pre-treatment, just after CRT and 3-month after CRT. The most recent ALC prior to treatment was utilized to analyze whether there are differences of initial lymphocyte count between two groups of lymphopenia and non-lymphopenia after CRT. The after-ALC and post-ALC were used to analyze post-treatment lymphopenia. We used the receiver operating characteristic analysis to define pretreatment ALC lymphopenia as <1,780 cells/mm3, after-ALC lymphopenia as <655 cells/mm3 and post-ALC lymphopenia as <1,430 cells/ mm3.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics, biochemical indicators, smoking habits, Karnofsky performance status, inflammation situation, and treatment characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. The cutoff values of after-ALC lymphopenia and post-ALC lymphopenia were set at the receiver operating characteristic curve yielded the combined maximum of sensitivity plus specificity. The primary clinical outcomes of interest were overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). OS was calculated from diagnosis to the date of any cause death, or to the last follow-up date. PFS was calculated from diagnosis to radiographic confirmed disease progression, including thorax failure and distant metastasis. The Kaplan-Meier analysis were used to estimate event rates and log-rank tests were used to compare between the groups. Continuous variables of patients were summarized by mean values with standard deviation. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare between lymphopenia and non-lymphopenia groups of after-ALC and post-ALC. Categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and analyzed with chi-square tests or two-sided Fisher’s exact test. All demographic and clinical variables were summarized in Table 1. To determine the independent prognostic factors, those factors with a significant unadjusted association with PFS and OS in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate stratified Cox regression model. The hazard ratios were reported as relative risks with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. All tests were two sided and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with LS-SCLC.

| Variables | All patients (N=226) N% or median value [range] | Pre-treatment absolute lymphocyte count | Absolute lymphocyte count after chemoradiation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALC <1,780 cells/mm3 (N=108) | ALC ≥1,780 cells/mm3 (N=118) | P | ALC <655 cells/mm3 (N=138) | ALC ≥655 cells/mm3 (N=88) | P | |||

| Age, years | 63 [28–82] | 63 [38–82] | 62 [28–79] | 0.361 | 63 [28–82] | 60.5 [35–75] | 0.011 | |

| Sex | 0.184 | 0.411 | ||||||

| Male | 171 (75.7) | 86 [80] | 85 [72] | 107 [78] | 64 [73] | |||

| Female | 55 (24.3) | 22 [20] | 33 [28] | 31 [22] | 24 [27] | |||

| Smoking status | 0.387 | 0.888 | ||||||

| Never smoker | 84 (37.2) | 37 [34] | 47 [40] | 52 [38] | 32 [36] | |||

| Current or ex-smoker | 142 (62.8) | 71 [66] | 71 [60] | 86 [62] | 56 [64] | |||

| KPS at diagnosis | 0.264 | 0.114 | ||||||

| ≥80 | 204 (90.3) | 95 [88] | 109 [92] | 128 [93] | 76 [86] | |||

| <80 | 22 (9.7) | 13 [12] | 9 [8] | 10 [7] | 12 [14] | |||

| Prophylactic cranial irradiation | 0.775 | 0.039 | ||||||

| Yes | 67 (29.6) | 33 [31] | 34 [29] | 34 [25] | 33 [38] | |||

| No | 159 (70.4) | 75 [69] | 84 [71] | 104 [75] | 55 [62] | |||

| Radiotherapy fractionation | 0.452 | 0.007 | ||||||

| Conventional fractionated RT | 145 (64.2) | 72 [67] | 73 [62] | 79 [57] | 66 [75] | |||

| Hyperfractionated RT | 81 (35.8) | 36 [33] | 45 [38] | 59 [43] | 22 [25] | |||

| Response for CRT | 0.392 | 0.441 | ||||||

| CR | 16 (7.1) | 8 [7] | 8 [7] | 10 [7] | 6 [7] | |||

| PR | 182 (80.5) | 89 [83] | 93 [79] | 111 [81] | 71 [81] | |||

| SD | 13 (5.8) | 7 [6] | 6 [5] | 10 [7] | 3 [3] | |||

| PD | 15 (6.6) | 4 [4] | 11 [9] | 7 [5] | 8 [9] | |||

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | 142 [92–179] | 142 [92–172] | 144 [106–179] | 0.021 | 142 [92–179] | 143 [98–170] | 0.259 | |

| Alkaline phosphatase (Alp) | 86 [47–239] | 86 [49–239] | 84 [47–234] | 0.201 | 87 [47–234] | 88 [49–239] | 0.125 | |

| Albumin (Alb) | 42 [20–79] | 42 [20–49] | 42 [25–79] | 0.622 | 42 [20–51] | 42 [25–79] | 0.383 | |

| Lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) | 192 [121–1,085] | 188 [133–710] | 189 [121–1,085] | 0.618 | 198 [121–710] | 188.5 [135–1,085] | 0.778 | |

| Pre-ALC | 1,890 [703–3,018] | |||||||

| After-ALC | 540 [10–1,600] | |||||||

| Post-ALC | 1,300 [630–2,140] | |||||||

LS-SCLS, limited-stage small cell lung cancer; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease.

Results

Three hundred and four patients diagnosed with LS-SCLC from 2007 to 2018 according to the inclusion criteria were included in the analysis. Whereas, both absolute lymphocyte count of after-ALC and post-ALC were available for only 226 of all these patients. The median follow-up was 23 months (range, 3–134 months). Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics for the study cohort. The median age was 63 years (range, 28–82 years). Two hundred and four patients (90.3%) had a Karnofsky performance status score of no less than 80. On radiation mode, 145 patients (64.2%) received conventional fractionated RT and 81 patients (35.8%) received hyperfractionated RT. Besides, prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) was delivered to 67 patients (29.6%).

The median pre-treatment ALC in our study patients decreased from 1,890 to 540 cells/mm3 just after CRT and then increased to 1,300 cells/mm3 three months after initiating CRT. The median hemoglobin was slightly higher with pre-treatment ALC ≥1,780 cells/mm3 compared to patients with ALC <1,780 cells/mm3 (P=0.021). In addition to this, there was no significant discrepancy between the two groups among other demographic and clinical characteristics. The median age was slightly younger with after-ALC ≥655 cells/mm3 compared to patients with after-ALC <655 cells/mm3 (P=0.011). Besides, more patients of after-ALC ≥655 cells/mm3 received prophylactic cranial irradiation compared to after-ALC <655 cells/mm3 subgroup (38% vs. 25%; P=0.039). For radiation mode, the patients who received hyperfractionated RT in group after-ALC <655 cells/mm3 were significantly more than those in group after-ALC ≥655 cells/mm3 (43% vs. 25%; P=0.007). Table 2 shows the association between ALC and radiation modes of patients with LS-SCLC. Thus, it is not difficult to conclude that hyperfractionated RT is more likely to cause lymphopenia in patients than conventional fractionated RT.

Table 2. The association between ALC and radiation modes of patients with LS-SCLC.

| Variables | Radiation modes (N=226) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional fractionated RT (N) | Hyperfractionated RT (N) | P | |

| Pre-ALC | 0.452 | ||

| <1,780 cells/mm3 | 72 | 36 | |

| ≥1,780 cells/mm3 | 73 | 45 | |

| After-ALC | 0.006 | ||

| <655 cells/mm3 | 79 | 59 | |

| ≥655 cells/mm3 | 66 | 22 | |

| Post-ALC | 0.075 | ||

| <1,430 cells/mm3 | 97 | 63 | |

| ≥1,430 cells/mm3 | 48 | 18 | |

LS-SCLS, limited-stage small cell lung cancer; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count.

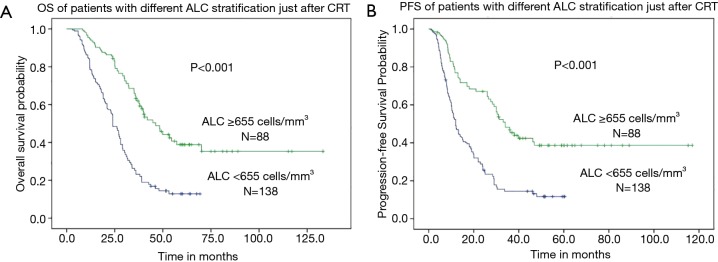

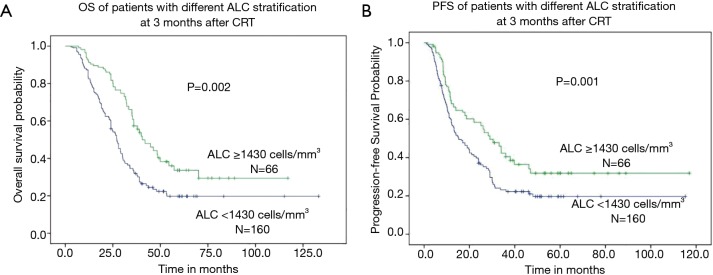

The median OS was 22.6 months (range, 3.0–133.2 months) for all patients. When subdivided into groups according to ALC, the median OS was 18.1 months (range, 3.0–69.3 months) in patients with after-ALC lymphopenia (ALC <655 cells/mm3) compared to 36.0 months (range, 8.3–133.2 months) for patients with after-ALC ≥655 cells/mm3 (P<0.001, log-rank test). As shown in Figure 1A, patients with after-ALC ≥655 cells/mm3 had obvious longer OS compared to patients with after-ALC <655 cells/mm3. The median PFS was 11.3 months (range, 1.0–117.0 months) for the entire cohort. The median PFS was 9.7 months (range, 1.0–60.4 months) in patients with after-ALC lymphopenia (ALC <655 cells/mm3) compared to 26.2 months (range, 1.2–117.0 months) for patients with after-ALC ≥655 cells/mm3 (P<0.001, log-rank test). As shown in Figure 1B, patients with after-ALC ≥655 cells/mm3 had significant longer PFS compared to patients with after-ALC <655 cells/mm3. Besides, the median OS was 19.0 months (range, 3.0–133.2 months) in patients with post-ALC lymphopenia (ALC <1,430 cells/mm3) compared to 35.3 months (range, 7.0–117.0 months) for patients with post-ALC ≥1,430 cells/mm3 (P=0.002, log-rank test). As shown in Figure 2A, patients with post-ALC ≥1,430 cells/mm3 had obvious longer OS compared to patients with post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3. The median PFS was 10.4 months (range, 1.0–115.2 months) in patients with post-ALC lymphopenia (ALC <1,430 cells/mm3) compared to 18 months (range, 1.6–117.0 months) for patients with post-ALC ≥1,430 cells/mm3 (P=0.001, log-rank test). As shown in Figure 2B, patients with post-ALC ≥1,430 cells/mm3 had significant longer PFS compared to patients with post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3.

Figure 1.

Clinical outcomes of patients with different ALC stratification just after CRT (after-ALC). (A) patients with after-ALC ≥655 cells/mm3 had obvious longer OS compared to patients with after-ALC <655 cells/mm3; (B) patients with after-ALC ≥655 cells/mm3 had significant longer PFS compared to patients with after-ALC <655 cells/mm3. ALC, absolute lymphocyte count.

Figure 2.

Clinical outcomes of patients with different ALC stratification 3 months after CRT (post-ALC). (A) patients with post-ALC ≥1,430 cells/mm3 had obvious longer OS compared to patients with post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3; (B) patients with post-ALC ≥1,430 cells/mm3 had significant longer PFS compared to patients with post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3. ALC, absolute lymphocyte count.

Table 3 shows the univariate analysis of potential variables associated with OS and PFS. Pre-ALC <1,780 cells/mm3 (HR: 1.296; P=0.04), after-ALC <655 cells/mm3 (HR: 2.633; P<0.001), post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3 (HR: 1.812; P=0.002) and current or ex-smokers (HR: 1.407; P=0.012) were statistically significant associated with shorter OS. Whereas, only after-ALC <655 cells/mm3 (HR: 2.582; P<0.001) and post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3 (HR: 1.573; P=0.001) were significantly associated with shorter PFS. Furthermore, Albumin ≥35 g/L was significantly associated with longer PFS (HR: 0.239; P=0.003). On multivariate analysis (Table 4), after-ALC <655 cells/mm3 (HR: 2.056; P<0.001) and post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3 (HR: 1.339; P=0.038) were significantly associated with shorter OS. Similarly, after-ALC < 655 cells/mm3 (HR: 2.606; P=0.002) and post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3 (HR: 1.409; P=0.015) were significantly associated with shorter PFS.

Table 3. Univariate analysis of potential variables associated with OS and PFS of patients with LS-SCLC.

| Variables | Overall survival (N=226) | Progression-free survival (N=226) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P | ||

| Age | 0.960 (0.652–1.412) | 0.834 | 0.894 (0.595–1.343) | 0.59 | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Current or ex-smoker | 1.407 (1.079–1.835) | 0.012 | 1.145 (0.869–1.509) | 0.337 | |

| Never Smoker | |||||

| KPS at diagnosis | |||||

| ≥80 | 0.757 (0.493–1.162) | 0.203 | 0.845 (0.542–1.319) | 0.459 | |

| <80 | |||||

| Prophylactic cranial irradiation | |||||

| Yes | 0.900 (0.692–1.170) | 0.43 | 1.086 (0.826–1.428) | 0.556 | |

| No | |||||

| Radiotherapy fractionation | |||||

| Conventional fractionated RT | 0.803 (0.603–1.068) | 0.132 | 0.865 (0.646–1.158) | 0.33 | |

| Hyperfractionated RT | |||||

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | |||||

| ≥110 | 0.981 (0.519–1.854) | 0.953 | 0.663 (0.338–1.303) | 0.233 | |

| <110 | |||||

| Albumin (Alb) | |||||

| ≥35 | 0.753 (0.420–1.350) | 0.341 | 0.239 (0.118–0.484) | 0.003 | |

| <35 | |||||

| Lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) | |||||

| <240 | 0.939 (0.678–1.301) | 0.707 | 1.061 (0.754–1.493) | 0.734 | |

| ≥240 | |||||

| Alkaline phosphatase (Alp) | |||||

| ≥120 | 1.389 (0.853–2.260) | 0.186 | 1.283 (0.796–2.069) | 0.306 | |

| <120 | |||||

| Pre-ALC | |||||

| <1,780 cells/mm3 | 1.296 (1.011–1.662) | 0.04 | 1.128 (0.815–1.562) | 0.467 | |

| ≥1,780 cells/mm3 | |||||

| After-ALC | |||||

| <655 cells/mm3 | 2.633 (2.025–3.424) | <0.001 | 2.582 (1.987–3.354) | <0.001 | |

| ≥655 cells/mm3 | |||||

| Post-ALC | |||||

| <1,430 cells/mm3 | 1.812 (1.381–2.378) | 0.002 | 1.573 (1.200–2.063) | 0.001 | |

| ≥1,430 cells/mm3 | |||||

LS-SCLS, limited-stage small cell lung cancer; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of potential variables associated with OS and PFS of patients with LS-SCLC.

| Variables | Overall survival (N=226) | Progression-free survival (N=226) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P | ||

| Pre-ALC | |||||

| <1,780 cells/mm3 | 1.524 (0.979–2.374) | 0.062 | 1.279 (0.915–1.789) | 0.15 | |

| ≥1,780 cells/mm3 | |||||

| After-ALC | |||||

| <655 cells/mm3 | 2.056 (1.470–2.875) | <0.001 | 2.606 (1.901–3.573) | 0.002 | |

| ≥655 cells/mm3 | |||||

| Post-ALC | |||||

| <1,430 cells/mm3 | 1.339 (1.016–1.766) | 0.038 | 1.409 (1.070–1.857) | 0.015 | |

| ≥1,430 cells/mm3 | |||||

LS-SCLS, limited-stage small cell lung cancer; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the absolute lymphocyte count of after-ALC and post-ALC were independent negative prognostic factors in LS-SCLC. As a reproducible and conveniently available hematology index, the absolute lymphocyte count was reported to have prognostic significance in glioma, nasopharyngeal cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cervical cancer (12-24). In SCLC, Cho et al. (25), reported radiation-related lymphopenia might be a new negative prognostic factor in LS-SCLC patients receiving CRT. Nevertheless, this study enrolled only 73 patients. Besides, Suzuki et al. (26), proposed that pretreatment total lymphocyte count (TLC) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) were found to have prognostic significance in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC). Pretreatment TLC ≤1.5×103/µL and pretreatment NLR >4.0 predicted inferior survival. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large sample retrospective study about the prognostic significance of absolute lymphocyte count in LS-SCLC receiving CRT. Our study showed that after-ALC <655 cells/mm3 (HR: 2.056; P<0.001) and post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3 (HR: 1.339; P=0.038) were significantly associated with shorter OS. Similarly, after-ALC <655 cells/mm3 (HR: 2.606; P=0.002) and post-ALC <1,430 cells/mm3 (HR: 1.409; P=0.015) were significantly associated with shorter PFS. Furthermore, we found hyperfractionated RT was more likely to cause lymphopenia in patients than conventional fractionated RT.

Peripheral blood lymphocytes are mainly lymphocytes in the blood circulation and are composed of T cells and B cells. Among them, T cells account for 70–80%, and B cells account for 20–30%. T cells include CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTL) and CD4+ helper T cells (Th). A subset of CD4+ helper T cells is critical for providing cytokine-mediated promotion of CTL proliferation and function. B cells, after being specifically activated by an antigen, form plasma cells that produce antibodies (Ab), thereby mediating the anti-tumor immunity.

Lymphocytes were known to be the only nondividing cell which is radiosensitive just like a cell in mitosis (27). Yovino et al. (11) found after 30 conventional fractions of 2 Gy RT, the circulating lymphocytes received 2.2 Gy mean dose and 99% of circulating lymphocytes received ≥0.5 Gy. The circulating lymphocyte reduction and cytogenetic abnormalities in lymphocytes caused by radiation exposure can persist for up to 10 years following low-dose total body radiation (28). Furthermore, the radiosensitivity of B-lymphocytes was higher than T-lymphocyte and the radiosensitivity of naïve T lymphocytes was higher than memory T lymphocytes (29). The radiosensitivity discrepancy and productivity of T lymphocyte subset may contributes to different tumor local control rate and distant recurrence rate, which leads to differences in patient survival. Several studies have been trying to under biochemical and physiologic mechanisms of lymphocytes radiosensitivity. Candeias et al. explored the mechanisms of low doses effects through analyzing the modulation of T-cell receptor gene repertoire in mice exposed to a single low (0.1 Gy) or high (1 Gy) dose of radiation and found low-dose radiation exposure specifically accelerated aging of the T-lymphocyte repertoire (30). Kuo et al. demonstrated radiation-related systemic lymphopenia appeared to be mediated by radiation-induced tumor Gal-1 secretion, which led to intratumoral immune suppression and enhanced angiogenesis and then promoted tumor progression. Thus, combining Gal-1 blockade with RT may be a potent strategy to overcome radiation-related lymphopenia and immune suppression within the tumor microenvironment (31). With regard to radiation-induced apoptosis of lymphocytes passing radiation field might also lead to systemic lymphopenia (32) and the extent of the tumor might be related to lymphocyte reduction. Tang et al. founded the association between lymphopenia, larger gross tumor volume (GTV) and higher lung V5 to V10 (14). Thus, the potential benefit of techniques that minimized the V5-V10 might be a choice to reduce the degree of lymphopenia.

Mole et al. demonstrated RT could produce tumor control outside the radiation field (33), which is described as abscopal effect. Radiation resulted in an immunogenic death and antigen release to stimulate antigen-presenting cells (APCs) maturation.

In addition to this, RT reprogrammed the tumor microenvironment conducive to effector T-cell recruitment and function through inducing expression of inflammatory mediators, interferons (IFNs), and appropriate chemokines that attracted T cells. Besides, RT transformed tumor macrophages to M1 hypotype to enable T-cell homing and played antitumor immunity function. With regard to the importance of lymphocyte in the immune response to cancer, many immunotherapy strategies were focused on modulation of lymphocyte activity for efficacy. For example, several studies chose CD40 agonists or Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists or IFN to enhance dendritic cell maturation. Furthermore, agonistic antibodies directed against costimulatory molecules on T cells such as OX-40, CD137 and CD27 were delivered to stimulate T cells. Besides, the blocking antibodies against coinhibitory molecules such as CTLA-4, PD-1 and PD-L1 were also chosen to increase T-cell function. Considering the conventional dose/fraction schemes were designed from the radiobiology principles instead of immunological principles and it was associated with a significant immune-suppressive response in tumors through upregulation of Treg cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC), and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) (34). Whereas stereotactic body RT (SBRT) could maximize antigen presentation and in situ vaccination to boost effector T cells function. Furthermore, Maclennan et al. demonstrated lymphocyte count was inversely proportional to the number of fractions when the total radiation dose was delivered invariable (35). Considering that the PTV size and fraction numbers were significantly associated with dose to circulating blood passing radiation field, SBRT might be a promising strategy for relative small primary tumors. Recent evidence suggested a single fraction of low-dose irradiation (LDI) (single doses ≤1 Gy) could reprogram tumor microenvironment to recruit effector T cells and allow T cell infiltration (36). Thus, LDI might be a promising strategy for larger primary tumors. Considering the negative impact of systemic lymphopenia on survival, optimal dose/fractionation schemes combing immune modulation therapies and immunogenic chemotherapies may be effective.

The current study is limited by its retrospective nature. We can not distinguish between lymphocyte subsets, cytokines in peripheral blood and tumor tissues to obtain direct evidence that lymphopenia leads to shorter overall survival and progression free survival in patients. Other than this, treatment techniques may have discrepancy in our study period and lead to different dose to circulating blood passing radiation field. Despite these limitations, this study investigated both pre- and post- CRT lymphopenia on clinical outcomes in LS-SCLC patients. Whereas, larger and cooperative study was needed to verify lymphopenia is a mechanism for shorter survival or just a predictor. Possible novel strategies may include immunoprotection or modulation before or after treatment to improve response rates and overall survival in small cell lung cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National key research and development program of China (2018YFC1313201).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Obtaining approval (ID: SDZLEC2016-001-01) from the ethics Review Board.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, et al. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4539-44. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schabath MB, Nguyen A, Wilson P, et al. Temporal trends from 1986 to 2008 in overall survival of small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer 2014;86:14-21. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Meerbeeck JP, Fennell DA, De Ruysscher DK. Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet 2011;378:1741-55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60165-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argiris A, Murren JR. Staging and clinical prognostic factors for small-cell lung cancer. Cancer J 2001;7:437-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 2011;331:1565-70. 10.1126/science.1203486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlin AM, Henriksson ML, Van Guelpen B, et al. Colorectal cancer prognosis depends on T-cell infiltration and molecular characteristics of the tumor. Mod Pathol 2011;24:671-82. 10.1038/modpathol.2010.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohr J, Ratliff T, Huppertz A, et al. Effector T-cell infiltration positively impacts survival of glioblastoma patients and is impaired by tumor-derived TGF-beta. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:4296-308. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiraoka K, Miyamoto M, Cho Y, et al. Concurrent infiltration by CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells is a favourable prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2006;94:275-80. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohtani H. Focus on TILs: prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Immun 2007;7:4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray-Coquard I, Cropet C, Van Glabbeke M, et al. Lymphopenia as a prognostic factor for overall survival in advanced carcinomas, sarcomas, and lymphomas. Cancer Res 2009;69:5383-91. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yovino S, Kleinberg L, Grossman SA, et al. The etiology of treatment-related lymphopenia in patients with malignant gliomas: modeling radiation dose to circulating lymphocytes explains clinical observations and suggests methods of modifying the impact of radiation on immune cells. Cancer Invest 2013;31:140-4. 10.3109/07357907.2012.762780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossman SA, Ye X, Lesser G, et al. Immunosuppression in patients with high-grade gliomas treated with radiation and temozolomide. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:5473-80. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu LT, Chen QY, Tang LQ, et al. The prognostic value of treatment-related lymphopenia in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Cancer Res Treat 2018;50:19-29. 10.4143/crt.2016.595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang C, Liao Z, Gomez D, et al. Lymphopenia association with gross tumor volume and lung V5 and its effects on non-small cell lung cancer patient outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;89:1084-91. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi N, Usui S, Kikuchi S, et al. Preoperative lymphocyte count is an independent prognostic factor in node-negative non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2012;75:223-7. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davuluri R, Jiang W, Fang P, et al. Lymphocyte nadir and esophageal cancer survival outcomes after chemoradiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017;99:128-35. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang P, Jiang W, Davuluri R, et al. High lymphocyte count during neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is associated with improved pathologic complete response in esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol 2018;128:584-90. 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afghahi A, Purington N, Han SS, et al. Higher absolute lymphocyte counts predict lower mortality from early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:2851-8. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ownby HE, Roi LD, Isenberg RR, et al. Peripheral lymphocyte and eosinophil counts as indicators of prognosis in primary breast cancer. Cancer 1983;52:126-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chadha AS, Liu G, Chen HC, et al. Does unintentional splenic radiation predict outcomes after pancreatic cancer radiation therapy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017;97:323-32. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fogar P, Sperti C, Basso D, et al. Decreased total lymphocyte counts in pancreatic cancer: an index of adverse outcome. Pancreas 2006;32:22-8. 10.1097/01.mpa.0000188305.90290.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark EJ, Connor S, Taylor MA, et al. Preoperative lymphocyte count as a prognostic factor in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2007;9:456-60. 10.1080/13651820701774891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho O, Chun M, Chang SJ, et al. Prognostic value of severe lymphopenia during pelvic concurrent chemoradiotherapy in cervical cancer. Anticancer Res 2016;36:3541-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu ES, Oduyebo T, Cobb LP, et al. Lymphopenia and its association with survival in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2016;140:76-82. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho O, Oh YT, Chun M, et al. Radiation-related lymphopenia as a new prognostic factor in limited-stage small cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol 2016;37:971-8. 10.1007/s13277-015-3888-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki R, Lin SH, Wei X, et al. Prognostic significance of pretreatment total lymphocyte count and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol 2018;126:499-505. 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schrek R. Qualitiative and quantitative reactions of lymphocytes to x-rays. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1961;95:839-48. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1961.tb50080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Massarani G, Najjar F, Aljapawe A, et al. Evaluation of circulating microparticles in healthy medical workers occupationally exposed to ionizing radiation: A preliminary study. Int J Occup Med Environ health 2018;31:783-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belka C, Ottinger H, Kreuzfelder E, et al. Impact of localized ra- diotherapy on blood immune cells counts and function in hu- mans. Radiother Oncol 1999;50:199-204. 10.1016/S0167-8140(98)00130-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Candéias SM, Mika J, Finnon P, et al. Low-dose radiation accelerates aging of the T-cell receptor repertoire in CBA/Ca mice. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017;74:4339-51. 10.1007/s00018-017-2581-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuo P, Bratman SV, Shultz DB, et al. Galectin-1 mediates radiation-related lymphopenia and attenuates NSCLC radiation response. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:5558-69. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yovino S, Grossman SA. Severity, etiology and possible consequences of treatment-related lymphopenia in patients with newly diagnosed high- grade gliomas. CNS Oncol 2012;1:149-54. 10.2217/cns.12.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mole RH. Whole body irradiation; radiobiology or medicine? Br J Radiol 1953;26:234-41. 10.1259/0007-1285-26-305-234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrera FG, Bourhis J, Coukos G. Radiotherapy combination opportunities leveraging immunity for the next oncology practice. Ca Cancer J Clin 2017;67:65. 10.3322/caac.21358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacLennan IC, Kay HE. Analysis of treatment in childhood leukemia. IV. The critical association between dose fractionation and immunosuppression induced by cranial irradiation. Cancer 1978;41:108-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klug F, Prakash H, Huber PE, et al. Low- dose irradiation programs macrophage differentiation to an iNOS(1)/M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective T cell immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2013;24:589-602. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]