Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationship between insurer market structure, health plan quality, and health insurance premiums in the Medicare Advantage (MA) program.

Data Sources/Study Setting

Administrative data files from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, along with other secondary data sources.

Study Design

Trends in MA market concentration from 2008 to 2017 are presented, alongside logistic and linear regression models examining MA plan quality and premiums as a function of insurer market structure for 2011.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

Data are publicly available.

Principal Findings

MA plans that tend to operate in more concentrated MA markets have a higher predicted probability of receiving a high‐quality health plan rating. Operating in more concentrated MA markets was also found to be associated with higher premiums. Among plans that tend to operate in very concentrated MA markets, high‐quality MA plans were associated with premiums as much as two times higher than premiums associated with lower‐quality plans.

Conclusions

Any policies directed at enhancing insurer competition should consider implications for health plan quality, which may be very different than the implications for enrollee premiums.

Keywords: competition, health care markets, Medicare Advantage, quality

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, proposed mergers and acquisitions among major U.S. health insurers have attracted widespread media attention. Insurers argue that consolidation can lead to lower prices through increased bargaining power in negotiations with providers.1 However, consumer advocates, politicians, and policy experts alike have raised concerns that such mergers would adversely impact patients via higher cost sharing for care and a reduced focus on quality and innovation.2, 3, 4

These concerns are not new; market concentration has long been a key issue for policy makers, with numerous examples of efforts to promote competition in U.S. health insurance markets. While the most prominent example may be the health insurance marketplaces introduced through the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA), other legislation, such as the 2003 Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act, has included provisions designed to increase competition among health insurers. Arguments in favor of these policies often include rhetoric around the role of competition in fostering higher quality coverage.5

Despite the ubiquity of arguments around competition and quality, few studies have assessed the impact of insurer market concentration on health plan quality. Prior work in this area has focused primarily on the association between insurer market concentration and prices for health care services. More recently, studies have examined the impact of insurer market concentration on health insurance premiums in the employer‐sponsored market and in the health insurance marketplaces. However, less is known about market concentration in the Medicare Advantage (MA) program. This is important because mergers, such as those proposed between Anthem and Cigna, and Aetna and Humana in 2015, would potentially impact millions of elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries who receive their benefits through private plans. Initially just a small portion of the Medicare program, more than 17.5 million beneficiaries are now enrolled in private MA plans, with over a third enrolled in plans through one of these four companies.6, 7 Given the increasingly prominent role of private plans in Medicare, understanding the impact of insurer market concentration on the cost and quality of MA coverage is essential for better policy making.

The purpose of this study is to examine the intersection between insurer market structure, health plan quality, and health insurance premiums in the MA program, in order to begin to better understand the direct and indirect effects on patients of insurance company mergers and acquisitions, as well as policies aimed at increasing competition. This study has two specific aims: first, to assess the relationship between insurer market concentration and health plan quality in the MA program, and second, to assess whether health plan quality modifies the relationship between insurer market concentration and health insurance premiums in the MA program.

2. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

2.1. Health plan quality

Health plan quality is a multidimensional construct that includes such diverse elements as enrollee satisfaction, health plan design, and quality of clinical care. As an intermediary between the patient and providers, insurers do not always have a direct influence on clinical quality. Nonetheless, there are a number of mechanisms through which insurers may have a substantial influence on the quality of care that enrollees receive. These mechanisms include the initial recruitment of high‐quality providers, as well as ongoing quality improvement efforts such as support for the adoption of clinical protocols and evidence‐based medicine,8 provision of education for clinicians and/or enrollees,9 development of disease management programs,10 incentive programs for clinicians,11 incentive programs for enrollees,12 and structured cost sharing to encourage the use of high‐value care and discourage the use of low‐value care.13 While it is critical to understand these specific mechanisms through which insurers may play a role in enhancing quality of clinical care, the focus here is broader: to examine the wider picture of health plan quality. Therefore, this study focuses on the reduced‐form relationship between insurer market concentration and plan quality, as opposed to examining the specific mechanisms through which insurer market concentration may affect quality of care.

The importance of health plan quality is reflected in the decision by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to monitor and publish MA plan quality ratings. These quality ratings are visible to current and potential MA enrollees—as well as the general public—via a star rating system on the Medicare Plan Finder site.14 The visibility of these quality ratings theoretically provides an incentive to MA plans to improve the quality of care provided to patients. Further incentives were introduced via the ACA, which included provisions that modified MA payment policy such that benchmark payment rates and rebates would be based on plan quality from 2012.15 Payment incentives such as these theoretically provide a strong incentive for insurers to focus on quality.

2.2. Market concentration and health plan quality

The relationship between plan quality and insurance market concentration is somewhat ambiguous. On one hand, increased market power would provide insurers with greater leverage in negotiations with providers, allowing insurers to implement quality improvement programs and incentivize providers to deliver higher quality care. Increased market power could also create greater savings via economies of scale, thus freeing up more funds with which to improve quality. However, an alternative possibility is that with greater market share, insurers may reduce their emphasis on quality as consumers face limited plan choice.

Importantly, an insurer's leverage in negotiations with health care providers will also depend on the concentration of the local provider market, with insurers potentially facing more difficulty in negotiating quality standards and quality improvements in more concentrated provider markets as they are less able to exclude noncompliant or lower‐quality providers from their networks. In more competitive provider markets, providers may seek to distinguish themselves along both price and quality lines.

Many of the above factors—visibility of quality ratings, payment incentives, insurer market power, and provider market structure—likely impact the extent to which insurers focus on improving overall health plan quality. Given that increasing the competitiveness of insurance markets is an oft‐stated policy priority, understanding whether, and to what extent, insurer market concentration is associated with health plan quality is critically important.

3. RELEVANT LITERATURE

Few studies have examined the relationship between insurer market concentration and health plan quality, and fewer still assess this relationship in the context of the MA program. Most relevant to this study, a paper by Frakt, Pizer, and Feldman examines the relationship between vertical MA plan‐provider integration, premiums, and plan quality in 2009.16 Their work suggests that a positive relationship exists between plan quality and premiums, with their findings indicating that one additional quality star was associated with $9 higher premiums among MA plans.

Studies from the mid‐2000s by Scanlon et al examine quality and competition among non‐MA health maintenance organizations (HMOs).17, 18 Their earlier findings suggest that competition between HMOs was not statistically significantly associated with clinical process quality, but was associated with enrollee satisfaction.17 Later work found no statistically significant association between HMO competition and plan quality.18

Recent related literature examines market dynamics and dimensions of “benefit generosity” in MA. In a 2018 study, Pelech examines pre‐ACA policy changes impacting private fee‐for‐service (PFFS) plans, finding that reductions in county‐level plan offerings led to an increase in expected enrollee out‐of‐pocket spending and higher premiums for PFFS plans.19 A 2014 study by Cabral et al exploits the introduction of MA payment floors in 2000, finding that, among plans receiving higher payments, greater market share was associated with lower “pass through” of those payments to enrollees in the form of reduced premiums.20 McCarthy and Darden's 2017 study examines the impact of MA quality ratings on premiums and plan offerings for 2009‐10, finding that contracts receiving higher star ratings raised their premiums in the subsequent year.21 Taken together, these studies suggest predominantly positive relationships between market concentration and premiums, and between star ratings and premiums.

More broadly, a number of studies have found insurer market concentration to be associated with lower provider prices.22, 23, 24 However, research is mixed regarding whether these lower prices translate into lower premiums for enrollees.25, 26, 27, 28 This is important because quality improvement, which has a direct benefit to enrollees similar to reduced premiums, may therefore not improve with improved insurer bargaining power.

This study adds to the limited existing literature on plan quality and health insurer market concentration, incorporating more recent and comprehensive data on MA market concentration and quality than has been used in prior work. Moreover, by unpacking several complex factors—insurer market concentration, provider market concentration, overall quality, clinical quality, consumer satisfaction, MA premiums—via transparent analyses, this study aims to reflect on these theoretically ambiguous relationships and advance the policy conversation around quality and competition in MA.

4. DATA

This study draws on a number of administrative data files from CMS, as well as data from the American Hospital Association (AHA), the Area Health Resources File (AHRF), and the Current Population Survey (CPS).

MA market concentration was measured by the Herfindahl‐Hirschman Index (HHI), with counties serving as the relevant geographic market and each insurance company's county‐level MA enrollment serving as the measure of market share. HHI ranges from near zero (a perfectly competitive market) to 10 000 (a monopoly) and is calculated by summing the squared market share for every firm in a market. While the total number of competing firms factors into this calculation, this method lends greater weight to firms with a larger market share; for example, a county with five insurers with equal market share of 20 percent would have an HHI of 2000. However, if the same market had one dominant insurer with 80 percent market share and four insurers with a 5 percent share, HHI would equal 6500. The Federal Trade Commission generally considers any market with an HHI above 2500 to be highly concentrated.29

The county was chosen as the relevant geographic market for the HHI calculations as MA benchmark payment rates have historically been set at the county‐level. Moreover, prior work has demonstrated that some insurers will selectively offer MA plans in certain counties and not others, in part due to differences in payments across counties.30 Because many plans within a county belong to the same parent insurer, and for the purposes of this study, the focus is on the dominance of the parent company in a given market, market share is measured at the parent company level. The CMS Monthly MA Enrollment by State/County/Contract file was used to identify county‐level enrollment, and the MA plan directory was used to identify the parent organization for each MA contract in order to aggregate enrollment to the parent company level.31, 32

CMS does not share enrollment data for contracts with fewer than 11 enrollees, so all contracts with 10 or fewer enrollees in a county were excluded. Counties in which all participating contracts had 10 or fewer enrollees were also excluded as it was not possible to calculate HHI for these counties. Also excluded were counties in Puerto Rico, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. After these exclusions, HHI was calculated for 2963 counties.

MA quality star ratings are available at the contract level from the CMS MA Part C and D Quality Ratings files.33 Star ratings are based on measures gathered through the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey (CAHPS), CMS’ own Health Outcomes Survey, as well as other CMS administrative data sources.34 MA contracts are assessed on up to 55 individual quality measures.35 CMS aggregates the scores from each measure into five categories, with scores for each category translated into a 5‐star scale: “Staying Healthy: Screening, Tests and Vaccines,” “Managing Chronic (Long Term) Conditions,” “Ratings of Health Plan Responsiveness and Care,” “Health Plan Members’ Complaints and Appeals,” and “Health Plans’ Telephone Customer Service.” Scores from these categories are then used to calculate a summary score, also on a 5‐star scale.35

MA plan premium data were obtained from the CMS MA Landscape Source files.36 This study focuses on MA plans that include prescription drug benefits (MA‐PD plans), as these plans represent the vast majority (88 percent) of MA plans on the market.37 As both insurers and prospective enrollees are likely to consider Part C (health care) and D (prescription drug) premiums together rather than either premium in isolation, the joint Part C/D premium was used in the analytical models.

County‐level MA benchmark payment rates were obtained from the CMS MA rate calculation data files.38 These rates, along with Medicare fee‐for‐service expenditure averages, were used to calculate the ratio of the county‐level MA benchmark payment rate relative to average costs under fee‐for‐service Medicare in each county. The purpose of this was to serve as a measure approximating expected revenue relative to expected cost for MA plans in each county.

Three measures of provider market concentration are included. Hospital market concentration was measured by calculating HHIs with geographic markets set at the core‐based statistical area (CBSA) level and with market shares defined using each hospital's total annual Medicare days. This measure was constructed using AHA Annual Survey data.39 Additional measures of provider concentration include the number of county‐level hospital beds per 1000 population and number of county‐level physicians per 1000 population. Both variables are drawn from the AHRF.40

Additional market characteristics include the proportion of the county‐level Medicare population in fair/poor self‐rated health, the proportion of the county‐level population over 65 years, and county‐level median income. All were drawn from the CPS.41

MA plan characteristics, including plan type (HMO, preferred provider organization (PPO), PFFS) and profit status were drawn from the CMS MA plan directory file.32

5. METHODS

Descriptive analyses examining county‐level MA market concentration from 2008 to 2017 are presented to illustrate trends over time. Next, analytical models examining MA plan quality and plan premiums as a function of market structure are presented. While CMS quality and premium data are available for 2012 onward, the analytical models focus on 2011, as CMS implemented a new payment methodology incorporating plan‐level benchmark and rebate adjustments based on quality ratings beginning in 2012. Because the focus of this study is on understanding the relationship between market structure and plan quality, as opposed to the impact of this payment policy change on plan quality, 2011 represents the most recent “clean” year in which to examine the data.

The unit of analysis for the analytical models is the plan level. Enrollment‐weighted plan‐level means were calculated for all county‐level variables. Quality ratings, MA plan characteristics (plan type, profit status), and MA plan premiums are consistent across counties within each plan's service area, so these variables were not enrollment‐weighted.

5.1. Plan quality analyses

For the analyses examining plan quality, a logistic regression model (1) was estimated with the binary‐dependent variable High Quality representing the odds of plan p receiving a quality summary score of four stars or higher. These data are drawn from the 2013 MA Part C and D Quality Ratings datafiles,33 as these files report quality ratings that are based on data from prior years, including 2011.35 The model is specified as follows:

| (1) |

where HHI is the one‐year lagged enrollment‐weighted mean county‐level MA HHI for each plan. HospitalHHI is the lagged enrollment‐weighted mean CBSA‐level hospital HHI for each plan and Provider Concentration includes the lagged enrollment‐weighted mean county‐level physicians per 1000 population for each plan, and the lagged enrollment‐weighted mean county‐level hospital beds per 1000 population for each plan. Benchmark Ratio is the enrollment‐weighted mean ratio of the county‐level MA benchmark payment rate relative to county‐level average costs under fee‐for‐service Medicare for each plan in 2011 (this is not lagged, as benchmark rates are known by insurers well in advance of the benefit year). Market includes the lagged enrollment‐weighted mean CBSA‐level log per capita income, the lagged enrollment‐weighted mean proportion of the population over 65, and the lagged enrollment‐weighted mean proportion of the Medicare population in fair/poor health for each plan. PPO and PFFS are binary dummy variables for plan type (with HMO as the omitted category), and For Profit is a binary variable for profit status. Indices are MA plan p, year y, and εpt is the error term. Robust standard errors were used to correct for potential clustering.

The model above was repeated twice more, using high‐quality ratings on clinical process measures and high‐quality ratings on consumer satisfaction measures as the dependent variables in order to assess whether there may be differences in the association between MA market concentration and quality by dimension of quality. Predicted probabilities calculations were used to further explore model results.

5.2. Premium analyses

For the analyses examining MA plan premiums, an ordinary least‐squares linear regression model (2) was estimated, with the plan‐level premium as the dependent variable. The model is specified as follows:

| (2) |

where all variables are defined as above in (1). Model (2) also includes interaction terms to explore whether the relationship between MA premiums and MA market concentration is modified by plan quality or hospital market concentration. All analyses were performed in Stata v.14.

6. RESULTS

6.1. MA HHI trends

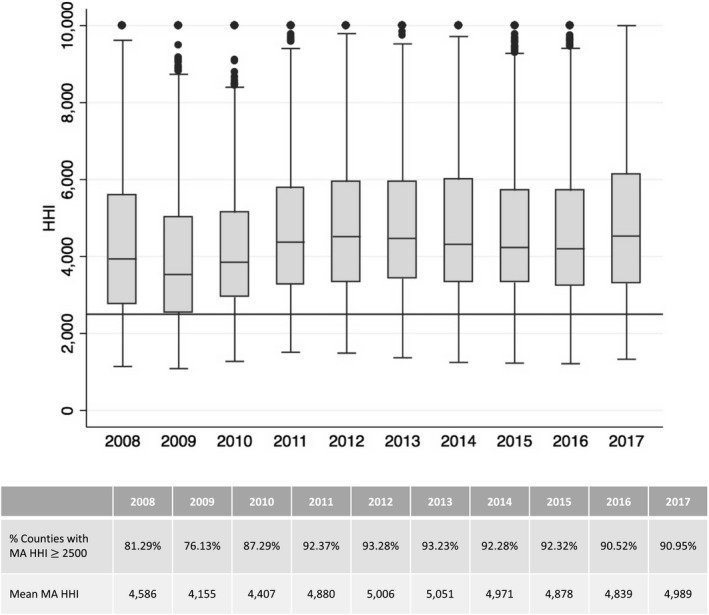

Over the last decade, the MA market has remained highly concentrated (Figure 1). Since 2011, over 90 percent of all county‐level MA markets were found to have an HHI over 2500. While the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission reports that the average Medicare beneficiary had 18 MA plans to choose from in 2017,6 this analysis suggests that the vast majority of beneficiaries live in counties dominated by a small number of insurers. So, although beneficiaries may have a great deal of choice among MA plans, they do not appear to have a great deal of choice among insurers.

Figure 1.

Medicare Advantage (MA) market concentration, 2008‐2017. This figure depicts the distribution of MA market concentration across counties within each year, using box plots. The boxes represent the interquartile range (the 25th to 75th percentile) of the values, with the line within each box representing the median. Dots represent outlier values. The Federal Trade Commission generally considers any market with an Herfindahl‐Hirschman Index (HHI) above 2500 to be highly concentrated. A horizontal line denotes where HHI equals 2500

6.2. Plan quality analyses

A total of 1232 MA plans were included in the analyses. Table 1 presents the characteristics of these plans. Across all plans, the mean Part C/D premium was $46.09 (standard deviation [SD] $53.71). 42.1 percent of plans received a summary quality rating of four stars or higher, with 35 percent of plans receiving ratings of four stars or higher on clinical process measures of quality, and 36.6 percent of plans receiving ratings of four stars or higher on consumer satisfaction measures of quality. MA plans tended to operate in highly concentrated MA markets in 2011, with a mean MA HHI of 3275 (SD 1059). MA plans tended to operate in highly concentrated hospital markets as well, with a mean hospital HHI of 3608 (SD 1931) across all plans. The majority of plans included in the analyses are HMOs (61.1 percent), with fewer PPOs (29.9 percent) and PFFS plans (9.0 percent). Nearly two‐thirds (66.5 percent) of plans are for‐profit.

Table 1.

MA plan characteristicsa

| Mean (SD) or % | |

|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |

| Premium | 46.09 (53.71) |

| % Zero premium plan | 32.9 |

| % High‐quality plan: Summary score | 42.1 |

| % High‐quality plan: Process measuresb | 35.4 |

| % High‐quality plan: Satisfaction measuresc | 36.6 |

| Independent variables | |

| Mean 2010 MA HHId | 3274.5 (1058.9) |

| Mean 2010 Hospital HHIe | 3607.8 (1931.0) |

| Mean 2010 County‐level Hospital beds per 1000 pop. | 2.6 (1.0) |

| Mean 2010 County‐level MDs per 1000 pop. | 2.3 (0.9) |

| Mean MA benchmark payment rate relative to average FFS Medicare spending | 1.16 (0.09) |

| Mean 2010 Log county‐level population over 65 | 10.7 (1.2) |

| Mean 2010 County median income | 49 447 (9150) |

| Mean 2010 County‐level proportion of Medicare beneficiaries in fair or poor health | 36.4 (8.7) |

| % HMO plans | 61.1 |

| % PPO plans | 29.9 |

| % PFFS plans | 9.0 |

| % For‐profit plans | 66.5 |

| n | 1232 |

The unit of analysis is the MA plan level. In the above table, most variables have been enrollment‐weighted and aggregated to the plan level to calculate the mean value across each plan's service area. Premiums, plan quality, plan type (HMO, PPO, PFFS), and plan profit status are consistent across the service area so these variables were not enrollment‐weighted.

A high‐quality score on process measures is operationalized as a total score of 4 stars or higher for both of the two categories “Staying Healthy: Screening, Tests and Vaccines” and “Managing Chronic (Long Term) Conditions.”

A high‐quality score on satisfaction measures is operationalized as a total score of 4 stars or higher for each of the three categories “Ratings of Health Plan Responsiveness and Care,” “Health Plan Members’ Complaints and Appeals,” and “Health Plans’ Telephone Customer Service.”

MA HHI is Medicare Advantage health insurance market concentration, as measured by the Herfindahl‐Hirschman Index (HHI), with counties serving as the relevant geographic market and each insurance company's county‐level MA enrollment serving as the measure of market share. MA HHI was enrollment‐weighted and aggregated to the plan level to calculate mean MA HHI across each plan's service area.

Hospital market concentration was measured by calculating HHIs with geographic markets set at the core‐based statistical area (CBSA) level and with market shares defined using each hospital's total annual Medicare days. As above, hospital HHI was enrollment‐weighted and aggregated to the plan level to calculate mean hospital HHI across each plan's service area.

Table 2 presents the results of logistic regression analyses examining the odds of an MA plan receiving a high‐quality rating in 2011. MA market concentration is positively and statistically significantly associated with odds of a high‐quality summary rating, though the magnitude of the association is negligible (odds ratio [OR]: 1.02, 95% CI: 1.01‐1.03, P < .01). PPO plans, PFFS plans, and for‐profit plans were statistically significantly associated with lower odds of high‐quality summary ratings.

Table 2.

Logistic regression models examining adjusted odds of a High‐quality summary score (4 stars or higher)

| High‐quality summary score | High‐quality score: process measures a | High‐quality score: satisfaction measures b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| MA HHI/100c | 1.02 (1.01‐1.03)** | 1.01 (0.99‐1.02) | 1.02 (1.00‐1.03)* |

| Hospital HHI/100d | 1.02 (1.01‐1.03)*** | 1.02 (1.01‐1.03)** | 1.02 (1.01‐1.02)** |

| Hospital beds per 1000 pop. | 1.24 (1.04‐1.47)* | 1.24 (1.05‐1.48)* | 1.22 (1.04‐1.43)* |

| MDs per 1000 pop. | 0.93 (0.77‐1.12) | 1.03 (0.85‐1.26) | 1.06 (0.87‐1.28) |

| MA benchmark payment rate relative to average FFS Medicare spending | 6.27 (1.43‐27.6)* | 2.61 (0.58‐11.81) | 1.40 (0.30‐6.48) |

| Log county‐level population over 65 | 1.30 (1.08‐1.56)** | 1.34 (1.11‐1.63)** | 0.80 (0.67‐0.96)* |

| County median income (in 1000s) | 1.01 (0.99‐1.02) | 1.02 (0.99‐1.04) | 0.99 (0.98‐1.01) |

| County‐level proportion of Medicare beneficiaries in fair or poor health | 0.99 (0.98‐1.00) | 0.98 (0.97‐0.99)* | 0.99 (0.97‐1.00) |

| PPO plan | 0.51 (0.37‐0.71)*** | 0.49 (0.35‐0.69)** | 0.78 (0.56‐1.08) |

| PFFS plan | 0.20 (0.11‐0.38)*** | 0.37 (0.20‐0.67)*** | 0.27 (0.15‐0.49)*** |

| For‐profit plan | 0.18 (0.14‐0.25)*** | 0.28 (0.21‐0.38)*** | 0.22 (0.16‐0.29)*** |

| n | 1232 | 1232 | 1232 |

| Pseudo R 2 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.13 |

aA high‐quality score on process measures is operationalized as a total score of 4 stars or higher for both of the two categories “Staying Healthy: Screening, Tests and Vaccines” and “Managing Chronic (Long Term) Conditions.”

bA high‐quality score on satisfaction measures is operationalized as a total score of 4 stars or higher for each of the three categories “Ratings of Health Plan Responsiveness and Care,” “Health Plan Members’ Complaints and Appeals,” and “Health Plans’ Telephone Customer Service.”

cMA HHI is Medicare Advantage health insurance market concentration, as measured by the Herfindahl‐Hirschman Index (HHI), with counties serving as the relevant geographic market and each parent insurance company's county‐level MA enrollment serving as the measure of market share. The unit of analysis is the MA plan level, so for these analyses, county MA HHI was enrollment‐weighted and aggregated to the plan level to calculate mean HHI across each plan's service area. For the above analyses, MA HHI was divided by 100 to allow for easier interpretation of coefficients.

dHospital market concentration was measured by calculating HHIs with geographic markets set at the core‐based statistical area (CBSA) level and with market shares defined using each hospital's total annual Medicare days. As above, CBSA‐level hospital HHI was enrollment‐weighted and aggregated to the plan level to calculate mean hospital HHI across each plan's service area. For the above analyses, hospital HHI was divided by 100 to allow for easier interpretation of coefficients.

***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05.

The results of the models examining adjusted odds of high‐quality clinical process ratings, and adjusted odds of high‐quality consumer satisfaction ratings look relatively similar to the main model (Table 2, Columns 3‐4). One notable difference is that MA market concentration was not found to be statistically significantly associated with odds of high‐quality clinical process ratings (OR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.99‐1.02, P = .29), but was statistically significantly associated with high‐quality consumer satisfaction ratings (OR: 1.02, 95% CI: 1.00‐1.03, P < .05). For both models, the magnitude of the association is small.

Table 3 presents predicted probabilities calculations examining the probability of a plan receiving a high‐quality summary rating at various levels of MA market concentration. Results suggest that plans that tend to operate in monopolistic MA markets (HHI = 10 000) have a much higher predicted probability of receiving a high‐quality summary rating (predicted probability [PP]: 71.73, 95% CI: 52.14‐85.52) as compared to plans that tend to operate in very competitive (HHI = 100) MA markets (PP: 23.92, 95% CI: 16.98‐32.59). When the results are stratified by hospital market concentration, we find that plans that tend to operate in more competitive hospital markets (hospital HHI < 2500), as well as highly competitive MA markets (HHI = 100), generally have the lowest predicted probability of receiving a high‐quality summary rating (PP: 19.63, 95% CI: 12.14‐30.14). In contrast, plans that tend to operate in more competitive hospital markets but that tend to also operate in monopolistic MA markets (HHI = 10 000) have the highest predicted probability of receiving a high‐quality summary rating (PP: 82.89, 95% CI: 59.98‐93.99).

Table 3.

Predicted probability of a High‐quality summary score (four stars or higher)a

| Mean MA market concentrationb | All plans | Concentrated hospital market (HHI ≥ 2500)c | Competitive hospital market (HHI < 2500)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted probability (95% CI) | Predicted probability (95% CI) | Predicted probability (95% CI) | |

| MA HHIb = 100 | 23.92 (16.98‐32.59) | 25.78 (17.97‐35.51) | 19.63 (12.14‐30.14) |

| MA HHI = 2500 | 34.28 (30.58‐38.19) | 34.64 (30.50‐39.03) | 33.50 (28.67‐38.71) |

| MA HHI = 5000 | 46.92 (40.91‐53.01) | 44.72 (38.86‐50.73) | 51.72 (42.90‐60.44) |

| MA HHI = 7500 | 59.96 (46.68‐71.92) | 55.25 (42.11‐67.70) | 69.49 (51.75‐82.87) |

| MA HHI = 10 000 | 71.73 (52.14‐85.52) | 65.33 (44.93‐81.32) | 82.89 (59.98‐93.99) |

Predicted probabilities calculations based on logistic regression models examining adjusted odds of receiving a high‐quality summary score. The models above include an interaction term for MA market concentration and hospital market concentration. Because one cannot directly interpret coefficients from interacted logistic models, results from the interacted regression models which form the basis for the above calculations are not presented.

MA HHI is Medicare Advantage market concentration, as measured by the Herfindahl‐Hirschman Index (HHI), with counties serving as the relevant geographic market and each insurance company's county‐level MA enrollment serving as the measure of market share. The unit of analysis is the MA plan level, so for the analyses that underpin the predicted probabilities presented above, HHI was enrollment‐weighted and aggregated to the plan level to calculate mean HHI across each plan's service area.

Hospital market concentration was measured by calculating HHIs with geographic markets set at the core‐based statistical area (CBSA) level and with market shares defined using each hospital's total annual Medicare days. As above, hospital HHI was enrollment‐weighted and aggregated to the plan level to calculate mean hospital HHI across each plan's service area. The analyses then differentiated between plans that tend to operate in more concentrated hospital markets (hospital HHI ≥ 2500) and those that tend to operate in more competitive hospital markets (hospital HHI < 2500).

6.3. Premium analyses

Table 4 presents adjusted mean premium calculations based on the linear regression model outlined in Equation (b). Results suggest that MA plan premiums are higher among plans that operate in more concentrated MA markets as compared to less concentrated MA markets (Column I). Operating in highly competitive MA markets (HHI = 100) is associated with adjusted mean premiums of $31.25 (95% CI: $22.49‐$40.02), whereas operating in more highly concentrated MA markets (HHI = 7500) is associated with adjusted mean premiums of $65.54 (95% CI: $53.72‐$77.36). Operating in monopolistic MA markets (HHI = 10 000) is associated with adjusted mean premiums of $77.12 (95% CI: $58.71‐$95.54).

Table 4.

Adjusted mean MA plan premiums by degree of MA market concentration, degree of hospital market concentration, and plan qualitya

| Mean MA market concentrationb | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower‐quality plans (summary score < 4 stars) | High‐quality plans (summary score ≥ 4 stars) | ||||||||

| All plans | Lower‐quality plans (summary score <4 stars) | High‐quality plans (summary score ≥4 stars) | Concentrated Hospital Market (HHI ≥ 2500)c | Competitive Hospital Market (HHI < 2500)c | Concentrated Hospital Market (HHI ≥ 2500) | Competitive Hospital Market (HHI < 2500) | Concentrated Hospital Market (HHI ≥ 2500) | Competitive Hospital Market (HHI < 2500) | |

| MA HHIb = 100 | $31.25 (22.49‐40.02) | $32.09 (22.42‐41.76) | $29.98 (14.89‐45.07) | $39.22 (29.30‐49.15) | $13.56 (3.70‐23.42) | $40.64 (30.30‐50.97) | $13.75 (2.24‐25.25) | $37.11 (20.96‐53.26) | $13.25 (0.17‐28.07) |

| MA HHI = 2500 | $42.38 (39.10‐45.66) | $37.01 (33.41‐40.60) | $50.63 (44.87‐56.39) | $48.17 (44.18‐52.17) | $29.50 (25.80‐33.20) | $43.24 (38.95‐47.53) | $23.62 (19.62‐27.63) | $55.55 (49.37‐61.74) | $39.09 (33.07‐45.11) |

| MA HHI = 5000 | $53.96 (48.47‐59.45) | $42.13 (35.92‐48.33) | $72.15 (62.23‐82.06) | $57.50 (51.97‐63.02) | $46.10 (38.00‐54.20) | $45.95 (40.16‐51.74) | $33.91 (24.75‐43.08) | $74.76 (64.47‐85.06) | $66.01 (55.15‐76.87) |

| MA HHI = 7500 | $65.54 (53.72‐77.36) | $47.25 (33.98‐60.51) | $93.66 (72.76‐114.56) | $66.82 (54.67‐78.98) | $62.70 (46.59‐78.81) | $48.67 (36.09‐61.24) | $44.20 (25.63‐62.77) | $93.98 (72.07‐115.88) | $92.92 (71.07‐114.78) |

| MA HHI = 10 000 | $77.12 (58.71‐95.54) | $52.37 (31.75‐72.98) | $115.18 (82.79‐147.55) | $76.15 (56.97‐95.32) | $79.30 (54.91‐103.70) | $51.38 (31.57‐71.18) | $54.49 (26.23‐82.75) | $113.19 (79.14‐147.23) | $119.84 (86.43‐153.24) |

Full regression model results can be viewed in Table S3.

Adjusted mean premiums calculated in Stata v.14, applying the margins command to ordinary least‐squares linear regression models based on Equation (b). Regression models include interactions between MA market concentration and hospital market concentration and MA market concentration and quality rating.

MA HHI is Medicare Advantage health insurance market concentration, as measured by the Herfindahl‐Hirschman Index (HHI), with counties serving as the relevant geographic market and each insurance company's county‐level MA enrollment serving as the measure of market share. The unit of analysis is the MA plan level, so for the analyses that underpin the predicted probabilities presented in this table, HHI was enrollment‐weighted and aggregated to the plan level to calculate mean HHI across each plan's service area.

Hospital market concentration was measured by calculating HHIs with geographic markets set at the core‐based statistical area (CBSA) level and with market shares defined using each hospital's total annual Medicare days. As above, hospital HHI was enrollment‐weighted and aggregated to the plan level to calculate mean hospital HHI across each plan's service area. The analyses then differentiated between plans that tend to operate in more concentrated hospital markets (hospital HHI ≥ 2500) and those that tend to operate in more competitive hospital markets (hospital HHI < 2500).

Columns II‐III of Table 4 stratify these results by plan quality. MA plan premiums appear to be more sensitive to MA market concentration among plans with higher quality ratings (Column III) than among plans with lower‐quality ratings (Column II). High‐quality plans operating in highly competitive MA markets (HHI = 100) are associated with premiums of $29.98 (95% CI: $14.89‐$45.07). However, high‐quality plans operating in highly concentrated MA markets (HHI = 7500) are associated with premiums of $93.66 (95% CI: $72.76‐$114.56). As above, this suggests that less competitive MA markets are associated with higher premiums. This relationship persists, but is less pronounced, among lower‐quality plans. Lower‐quality plans operating in highly competitive MA markets (HHI = 100) are associated with premiums of $32.09 (95% CI: $22.42‐$41.76), whereas lower‐quality plans operating in highly concentrated MA markets (HHI = 7500) are associated with premiums of $47.25 (95% CI: $33.98‐$60.51).

Columns IV‐V of Table 4 stratify the results by hospital market concentration. Again, operating in more concentrated MA markets is seen to be associated with higher premiums, and here, this relationship holds regardless of level of hospital market concentration. However, operating both in more competitive hospital markets and more competitive MA markets is associated with lower premiums. Findings from Columns VI‐IX, which stratify model results by both quality rating and hospital market concentration, suggest that higher quality plans operating in areas with highly concentrated MA markets are associated with higher premiums at either level of hospital market concentration (Columns VIII‐IX, Table 4) as compared to premiums among lower‐quality plans operating in highly concentrated MA markets.

7. DISCUSSION

Private insurers are playing an increasingly important role in the Medicare program. In 2017, Medicare paid private insurers over $210 billion to cover the approximately one‐third of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in private MA plans.42 Although the average Medicare beneficiary had as many as 18 plans to choose from in 2017, the MA market is dominated by a small number of firms: The findings presented here indicate that over 90 percent of county‐level MA markets were highly concentrated in 2017. With just 10 health insurance companies accountable for 70 percent of all MA enrollment, understanding the implications of MA market concentration is critical.6

The results of this study suggest that operating in more concentrated MA markets is associated with a much higher probability of receiving a high‐quality rating, as compared to MA plans that tend to operate in more competitive MA markets. This seems to support the notion that greater market share enables insurers to negotiate higher quality care more effectively. MA plans operating in competitive hospital markets but that tend to also operate in highly concentrated MA markets were found to have the highest probability of receiving a high‐quality summary rating. Thinking more broadly about these results, it is possible that MA plans may be able to more effectively recruit higher quality providers and negotiate higher quality care when they are the dominant insurer in an area with a more competitive provider market.

In line with prior literature in this area,16 the premium analyses show that plans that tend to operate in more concentrated MA markets are associated with higher premiums as compared to those that tend to operate in competitive MA markets. However, the impact of insurer market concentration on premiums may be modified by MA plan quality. Notably, premiums appear to be more sensitive to MA market concentration among high‐quality plans at all levels of hospital market concentration. Among plans operating in very competitive MA markets, premiums associated with high‐quality plans are similar to those of lower‐quality plans. However, among plans operating in very concentrated MA markets, high‐quality MA plans are associated with premiums as much as two times higher as compared to lower‐quality plans.

8. LIMITATIONS

There are important limitations to this work. A chief limitation of this study is its cross‐sectional design, which limits causal inference. To mitigate this issue, time‐lagged variables are used, both for MA market and hospital market concentration, and for the county‐ and CBSA‐level control variables. However, as the results only identify cross‐sectional associations, it remains possible that an alternate interpretation of results—that high‐quality plans tend to locate in less competitive areas—is true. While longitudinal analyses would theoretically resolve some of these issues, shifts in CMS’ quality metrics over time and the potential for strategic plan consolidation by insurers suggest that longitudinal analyses may also be problematic. In addition, as is common to analyses of market concentration, omitted variable bias is a potential issue, as is endogeneity if MA plan quality or premiums influence MA market share. For these reasons, the results presented here should be interpreted with caution.

Another limitation relates to the measurement of MA plan quality. In particular, it remains unclear whether CMS’ simplified star ratings fully reflect the multidimensional, complex construct of health plan quality more broadly. Indeed, plans with identical summary ratings may actually perform quite differently on various dimensions of quality. In addition, data on star ratings are only available at the contract level, not the individual plan level. The advantage to this is that MA contract‐level data are more stable over time, as insurers merge individual MA plans or modify benefit packages more frequently than contract mergers occur. However, enrollment‐weighted contract‐level quality ratings data obscure any differences in quality at the individual plan level, making it difficult to know whether a high‐quality rating reflects high performance across all plans within a contract, or whether there is variable performance across plans. Importantly, additional sensitivity analyses using county‐level models less subject to plan‐level variation yielded similar results (Tables S1 and S2). It is worth noting that, following the introduction of quality bonus payments in 2012, strategic plan‐ and contract‐level consolidation for the purpose of inflating star ratings has become an emergent concern.39 The potential gaming of quality ratings warrants further examination and underscores the importance of CMS making more granular quality ratings data available to researchers.

These analyses do not delve into differences between vertically integrated and nonvertically integrated insurers, nor do they adjust for provider payment mechanisms, both of which may have implications for plan quality. While some of these market dynamics have been captured through the inclusion of plan type in the models (as PFFS plans and PPOs are likely to rely more heavily on fee‐for‐service reimbursement than HMOs, and HMOs may be more likely to be vertically integrated), future work examining vertical integration and reimbursement methods in relation to plan quality and market share would be an important addition to the literature. Finally, these analyses primarily rely on data from 2011, due to the introduction of the new quality‐related MA benchmark bonus and rebate policies in 2012. Future studies should examine the impact of these payment policy changes in the relationship between competition and plan quality.

9. CONCLUSION

This study has broad implications for policy, as the findings suggest that the relationship between insurer market concentration and health plan quality may be more nuanced than typically acknowledged in policy discussions. Policy makers often propose competition‐enhancing policies with the goal of improving consumer welfare. These findings, while preliminary, suggest that any policies directed at enhancing insurer competition should consider implications for health plan quality, which may be very different than the implications for enrollee premiums. Thus, procompetition policies may require additional regulatory efforts to ensure plan quality at the local market level, necessitating coordination between federal and state actors. Such efforts would likely be bolstered by policies aimed at increasing transparency of health plan quality ratings. In the already highly concentrated MA market, the impact of insurance company mergers and acquisitions on the cost and quality of care must be carefully considered.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: The author conducted this research as an employee of the University of Edinburgh. Decisions regarding the design and conduct of the study, the statistical analysis and all publication decisions were made by the author alone.

Disclosures: No other disclosures.

Adrion ER. Competition and health plan quality in the Medicare Advantage market. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:1126–1136. 10.1111/1475-6773.13196

REFERENCES

- 1. Fuchs VR, Lee PV. A Healthy Side of Insurer Mega‐Mergers. The Wall Street Journal. August 26, 2015.

- 2. Abelson R. Bigger May Be Better for Health Insurers, but Doubts Remain for Consumers. New York Times. August 2, 2015.

- 3. Bomey N. Anthem to buy Cigna for $54B in mega insurance merger. USA Today. July 24, 2015.

- 4. Johnson C. Anthem announces it will buy Cigna to create new health insurance giant. The Washington Post. July 24, 2015.

- 5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) . Remarks by the President at Signing of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Baltimore, MD: CMS; 2003. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/History/downloads/BushSignMMA2003.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) . Status Report on the Medicare Advantage Program. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jacobson G, Damico A, Neuman T. Data Note: Medicare Advantage Enrollment, by Firm, 2015. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2015. http://files.kff.org/attachment/data-note-data-note-medicare-advantage-enrollment-by-firm-2015. Accessed July 3, 2017.

- 8. Grol R, Grimshaw J. Evidence‐based implementation of evidence‐based medicine. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1999;25(10):503‐513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davis D, O'Brien MAT, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor‐Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282(9):867‐874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mattke S, Seid M, Ma S. Evidence for the effect of disease management: is $1 billion a year a good investment? Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(12):670‐676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mendelson A, Kondo K, Damberg C, et al. The effects of pay‐for‐performance programs on health, health care use, and processes of care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(5):341‐353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giles EL, Robalino S, McColl E, Sniehotta FF, Adams J. The effectiveness of financial incentives for health behaviour change: systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e90347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chernew ME, Rosen AB, Fendrick AM. Value‐based insurance design. Health Aff. 2007;26(2):w195‐w203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Medicare.gov . Medicare Plan Finder. [online] 2017. https://www.medicare.gov/find-a-plan/questions/home.aspx. Accessed April 10, 2017.

- 15. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) . Status Report on the Medicare Advantage Program. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frakt AB, Pizer SD, Feldman R. Plan‐provider integration, premiums, and quality in the medicare advantage market. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6):1996‐2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scanlon DP, Swaminathan S, Chernew M, Lee W. Market and plan characteristics related to HMO quality improvement. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(6):56‐89S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scanlon DP, Swaminathan S, Lee W, Chernew M. Does competition improve health care quality? Health Serv Res. 2008;43(6):1931‐1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pelech D. Paying more for less? Insurer competition and health plan generosity in the Medicare Advantage program. J Health Econ. 2018;61:77‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cabral M, Geruso M, Mahoney N. Do larger health insurance subsidies benefit patients or producers? Evidence from Medicare Advantage. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 20470. Cambridge, MA: NBER ; 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCarthy IM, Darden M. Supply‐side responses to public quality ratings: evidence from medicare advantage. Am J Health Econ. 2017;3(2):140‐164. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roberts ET, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM. Market share matters: evidence of insurer and provider bargaining over prices. Health Aff. 2017;36(1):141‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Melnick GA, Shen Y, Yaling WuV. The increased concentration of health plan markets can benefit consumers through lower hospital prices. Health Aff. 2011;30(9):1728‐1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moriya AS, Vogt WB, Gaynor M. Hospital prices and market structure in the hospital and insurance industries. Health Econ Policy Law. 2010;5(4):459‐479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scheffler RM, Arnold DR, Fulton BD, Glied SA. Differing impacts of market concentration on affordable care act marketplace premiums. Health Aff. 2016;35(5):880‐888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Trish EE, Herring BJ. How do health insurer market concentration and bargaining power with hospitals affect health insurance premiums? J Health Econ. 2015;42:104‐114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jacobs PD, Banthin JS, Trachtman S. Insurer competition in federally run marketplaces is associated with lower premiums. Health Aff. 2015;34(12):2027‐2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dafny L, Duggan M, Ramanarayanan S. Paying a premium on your premium? Consolidation in the us health insurance industry. Am Econ Rev. 2012;102(2):1161‐1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Department of Justice, Federal Trade Commission . Horizontal Merger Guidelines. Washington, DC: DOJ; 2010. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2010/08/19/hmg-2010.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brown RS, Gold MR. What drives medicare managed care growth? Health Aff. 1999;18(6):140‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. CMS.gov . Monthly MA Enrollment by State/County/Contract ‐ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [online] https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MCRAdvPartDEnrolData/Monthly-MA-Enrollment-by-State-County-Contract.html. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- 32. CMS.gov . MA Plan Directory ‐ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [online] https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MCRAdvPartDEnrolData/MA-Plan-Directory.html. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- 33. CMS.gov . Part C and D Performance Data ‐ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [online] https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/PerformanceData.html. Accessed April 6, 2017.

- 34. Jacobson G, Damico A, Huang J, Neuman T. Reaching for the Stars: Quality Ratings of Medicare Advantage Plans, 2011. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2011. http://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/reaching-for-the-stars-quality-ratings-of/. Accessed April 10, 2017.

- 35. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Medicare Health & Drug Plan Quality and Performance Ratings 2013 Part C & Part D Technical Notes. Baltimore, MD: CMS; 2013. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/prescription-drug-coverage/prescriptiondrugcovgenin/downloads/2013-part-c-and-d-preview-2-technical-notes-v090612-.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36. CMS.gov . MA Landscape Source Files ‐ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [online] https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/index.html?redirect=/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/02_EnrollmentData.asp. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- 37. Kaiser Family Foundation . Fact Sheet: Medicare Advantage. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Fact-Sheet-Medicare-Advantage. Accessed July 3, 2017.

- 38. CMS.gov . Ratebooks & Supporting Data ‐ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [online] https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Ratebooks-and-Supporting-Data.html. Accessed May 16, 2016.

- 39. American Hospital Association . AHA Annual Survey. http://www.ahadata.com. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 40. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) . Area Health Resources File. https://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/topics/ahrf.aspx. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 41. Census.gov . U.S. Census Current Population Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 42. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) . The Medicare Advantage Program: Status Report. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials