Summary

Recently, CRISPR‐Cas12a (Cpf1) from Prevotella and Francisella was engineered to modify plant genomes. In this report, we employed CRISPR‐LbCas12a (LbCpf1), which is derived from Lachnospiraceae bacterium ND2006, to edit a citrus genome for the first time. First, LbCas12a was used to modify the CsPDS gene successfully in Duncan grapefruit via Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration. Next, LbCas12a driven by either the 35S or Yao promoter was used to edit the PthA4 effector binding elements in the promoter (EBEP thA4‐CsLOBP) of CsLOB1. A single crRNA was selected to target a conserved region of both Type I and Type II CsLOBPs, since the protospacer adjacent motif of LbCas12a (TTTV) allows crRNA to act on the conserved region of these two types of CsLOBP. CsLOB1 is the canker susceptibility gene, and it is induced by the corresponding pathogenicity factor PthA4 in Xanthomonas citri by binding to EBEP thA4‐CsLOBP. A total of seven 35S‐LbCas12a‐transformed Duncan plants were generated, and they were designated as #D35s1 to #D35s7, and ten Yao‐LbCas12a‐transformed Duncan plants were created and designated as #Dyao1 to #Dyao10. LbCas12a‐directed EBEP thA4‐CsLOBP modifications were observed in three 35S‐LbCas12a‐transformed Duncan plants (#D35s1, #D35s4 and #D35s7). However, no LbCas12a‐mediated indels were observed in the Yao‐LbCas12a‐transformed plants. Notably, transgenic line #D35s4, which contains the highest mutation rate, alleviates XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4 infection. Finally, no potential off‐targets were observed. Therefore, CRISPR‐LbCas12a can readily be used as a powerful tool for citrus genome editing.

Keywords: Cas12a, citrus, Cpf1, CRISPR, genome editing

Introduction

Genome editing is a powerful tool for increasing plant yields, improving food quality, enhancing crop disease resistance and developing new cultivars to meet market needs (Begemann et al., 2017). At present, several strategies are being exploited to edit plant genomes, including CRISPR‐Cas, meganucleases, TALENs and zinc finger nucleases (Martín‐Pizarro and Posé, 2018). Among them, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)‐mediated genome editing is the most attractive, owing to its comparatively easier and less expensive implementation (Islam, 2018). To date, CRISPR‐SpCas9, which is derived from Streptococcus pyogenes, has been widely used to modify the genomes of a variety of organisms. However, one major drawback associated with the CRISPR‐SpCas9 system is its off‐target effects (Fu et al., 2013), which has raised concerns and limited its adoption. Recently, CRISPR‐Cas12a from Prevotella and Francisella, a class II/type V CRISPR nuclease, has been employed as an alternative system for genome editing, and notably, it is reported to have fewer off‐targets in comparison with Cas9 (Kim et al., 2016; Kleinstiver et al., 2016).

CRISPR‐Cas12a has several unique features distinct from those of CRISP‐SpCas9 (Zetsche et al., 2015, 2017), as follows. (i) The canonical protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) of CRISPR‐Cas12a is TTTV (V=A, C and G), which is located at the 5′ end of the target site, whereas the CRISPR‐SpCas9 PAM is NGG, which is located at the 3′ end of the target site. (ii) CRISPR‐Cas12a requires a 43 nt crRNA, and CRISPR‐SpCas9 requires ~100 nt gRNA. (iii) CRISPR‐Cas12a generates 5′ staggered ends distal from the PAM, while CRISPR‐SpCas9 generates blunt ends 3 bp upstream of the PAM. (iv) Cas12a has both DNase activity and RNase activity, which is useful for multiplexed genome editing (Zetsche et al., 2017). These complementary properties make the CRISPR‐Cas12a an indispensable genome‐editing tool. CRISPR‐Cas12a was first successfully employed to edit the mammalian genome (Zetsche et al., 2015). Since then, CRISPR‐Cas12a has been successfully used to modify other organisms, such as plants, Drosophila and zebrafish (Endo et al., 2016; Moreno‐Mateos et al., 2017; Port and Bullock, 2016). To date, Acidaminococcus sp. BV3L6 Cas12a (AsCas12a), Francisella novicida Cas12a (FnCas12a) and Lachnospiraceae bacterium ND2006 Cas12a (LbCas12a) have been used to edit the genomes of crop and model plants, including green alga, rice, soybeans and tobacco (Begemann et al., 2017; Endo et al., 2016; Ferenczi et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017a,b,c; Xu et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2017), but not citrus. In addition, the performances of the three Cas12a homologs are different. LbCas12a reportedly performs better than AsCas12a in rice (Tang et al., 2017).

Citrus is an important fruit crop around the world, and it faces many abiotic and biotic stresses such as citrus canker and Huanglongbing disease (Ference et al., 2018; Wang and Trivedi, 2013; Wang et al., 2017a,b). To promote citrus breeding, CRISPR‐SpCas9 has been employed to edit the citrus genome in several reports (Jia and Wang, 2014a; Jia et al., 2016, 2017b; Peng et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017). CsLOB1 is reportedly the canker susceptibility gene (Hu et al., 2014). To produce citrus varieties that are resistant to Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc) infection, CRISPR‐SpCas9 was used in two studies to modify the PthA4 effector binding elements (EBEs) in the CsLOB1 promoter (EBEPthA4‐CsLOBP; Jia et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2017). However, only the Type I EBEPthA4‐CsLOBP was modified in transgenic Duncan grapefruit, because no suitable sgRNAs can be designed to target both alleles of EBEPthA4‐CsLOBP owing to the single nucleotide polymorphisms in this region (Jia et al., 2016). Duncan grapefruit is a hybrid between the pummelo (Citrus maxima) and the sweet orange (Citrus sinensis; Velasco and Licciardello, 2014). Type I CsLOBP originates from sweet orange (Xu et al., 2013), and Type II CsLOBP comes from the pummelo (Wu et al., 2014). Therefore, one of the challenges of SpCas9‐mediated EBEPthA4‐CsLOBP modification is the fact that two types of CsLOBPs in Duncan grapefruits make a single sgRNA targeting infeasible for modifying two alleles. An alternative genome‐editing system that can be employed to edit two alleles of EBEPthA4‐CsLOBPs using a single sgRNA/crRNA would be helpful. CRISPR‐Cas12a recognizes a thymidine‐rich PAM site, TTTV, which commonly occurs in the promoter regions and the 5′ and 3′ UTRs (Moreno‐Mateos et al., 2017; Zetsche et al., 2015). Undoubtedly, it is worth testing whether CRISPR‐Cas12a can be employed to modify citrus to expand our biotechnology toolbox.

In this study, LbCas12a was employed to edit the Duncan grapefruit gene CsPDS via Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration. The results verified that LbCas12a could be harnessed to edit the citrus genome. Subsequently, using a single crRNA, EBEPthA4‐CsLOBP was successfully modified by LbCas12a in transgenic Duncan plants. Notably, one transgenic Duncan line could alleviate XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4‐induced canker symptoms.

Results

Modification of CsPDS in Duncan grapefruit via the Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration of GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐cspds

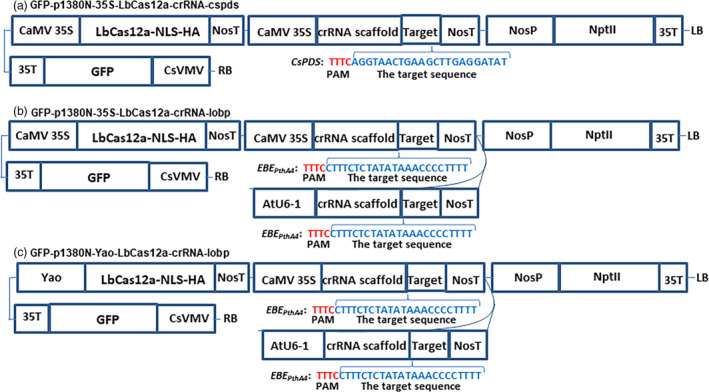

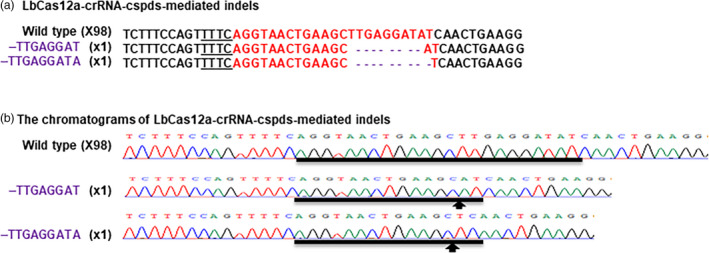

CaMV 35S‐SpCas9/CaMV 35S‐sgRNA and CaMV 35S‐SaCas9/CaMV 35S‐sgRNA were used to test the CRISPR‐Cas9 function through Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration (Jia and Wang, 2014a; Jia et al., 2017a). Therefore, CaMV 35S alone was used to drive both LbCas12a and crRNA in vector GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐cspds, which was harnessed for Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration (Figure 1a). First, CRISPR‐LbCas12a was used to edit the ninth exon of CsPDS in Duncan plants via transient expression (Figure S1) using Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration (Jia and Wang, 2014b). The binary vector GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐cspds was constructed and agroinfiltrated into Duncan leaves (Figure 1a), which were pretreated with Xcc (Jia and Wang, 2014b). Genomic DNA that was extracted from treated Duncan leaves four days later was subjected to PCR amplification, vector ligation and colony sequencing. The sequencing results confirmed that two colonies harboured LbCas12a‐directed CsPDS indels among the 100 random colonies sequenced here (Figure 2). Therefore, CRISPR/LbCfp1 is functional for citrus genome editing.

Figure 1.

The Schematic diagram of binary vectors. (a) Schematic diagram of GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐cspds. A 23 bp crRNA was used to target the CsPDS coding region, which is located in the ninth extron. (b) Schematic diagram of GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp. A 23 bp crRNA, driven by CaMV 35S and AtU6‐1, was employed to target EBEP thA4‐CsLOBP. (c) A schematic diagram of GFP‐p1380N‐Yao‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp. A 23 bp sgRNA was designed to edit the EBEP thA4‐CsLOBP. CsVMV, the cassava vein mosaic virus promoter; GFP, green fluorescent protein; CaMV 35S and 35T, the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and its terminator; AtU6‐1, Arabidopsis U6‐1 promoter; Yao, Yao promoter; LbCas12a‐NLS‐HA, the LbCas12a endonuclease containing nuclear location signal and HA tag at its C‐terminal; targets were highlighted in blue; PAM, protospacer adjacent motif, highlighted in red; crRNA scaffold, the CRISPR RNA scaffold; NosP and NosT, the nopaline synthase gene promoter and its terminator; NptII, neomycin phosphotransferase II; and LB and RB, the left and right borders of the T‐DNA region.

Figure 2.

Targeted genome engineering in Duncan grapefruit using the CRISPR‐LbCas12a system. (a) Targeted mutations induced by GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐cspds in the CsPDS gene in Duncan grapefruit. The crRNA‐targeted CsPDS sequence is highlighted in red, and the indels are shown in purple. (b) CRISPR‐LbCas12a‐mediated indel chromatograms in the CsPDS gene. Mutations are indicated by arrows.

Targeted mutagenesis of EBEPthA4‐CsLOBP in Duncan grapefruit

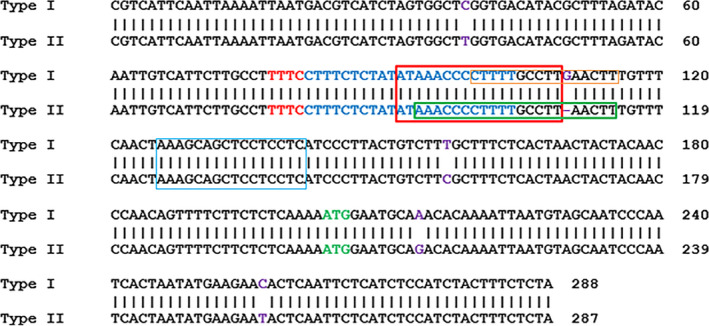

Two binary vectors, GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp and GFP‐p1380N‐Yao‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp, were constructed to edit EBEPthA4‐CsLOBP. When driven by either the CaMV35 promoter or the Yao promoter, SpCas9 was successfully used to edit the citrus genome in a previous study (Jia et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017). Here, we employed the CaMV 35S promoter and the Yao promoter to drive LbCas12a expression (Figure 1b and c). However, in transgenic citrus, both CaMV 35S and AtU6‐1 were successfully used to drive sgRNAs for CRISPR‐SpCas9 (Jia et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2017) and for CRISPR‐SaCas9 (Jia et al., 2017a). To guarantee that the crRNA could be efficiently expressed in LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐transformed citrus, both CaMV 35S and AtU6‐1 were employed to drive crRNA (Figure 1b and c). There are two types of CsLOBPs in Duncan grapefruits, Type I CsLOBP and Type II CsLOBP (Figure 3; Jia et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2017). A single crRNA was selected to target the conserved EBEPthA4‐CsLOBP region (Figures 1b and c, 3). By contrast, a single sgRNA could not be used to modify both types of CsLOBPs, since the sgRNA targeting region in the EBEPthA4‐CsLOBP contains single nucleotide polymorphisms between the two types of CsLOBPs in Duncan plants (Jia et al., 2016).

Figure 3.

Part of the CsLOB1 and its promoter in Duncan grapefruit. A sequence alignment of two alleles of CsLOB1, Type I and Type II. The crRNA‐targeting site is indicated in blue. PAM is indicated in red. The translation start site is indicated in green. The difference in the two alleles is shown in purple. The EBEP thA4‐CsLOBP is highlighted by a red rectangle, which is overlapped with artificial dTALE dCsLOB1.1. The dCsLOB1.2‐binding site is indicated with a blue rectangle, the dCsLOB1.3‐binding site is noted by an orange rectangle, and the artificial dTALE dCsLOB1.4 binding site is highlighted by a green rectangle.

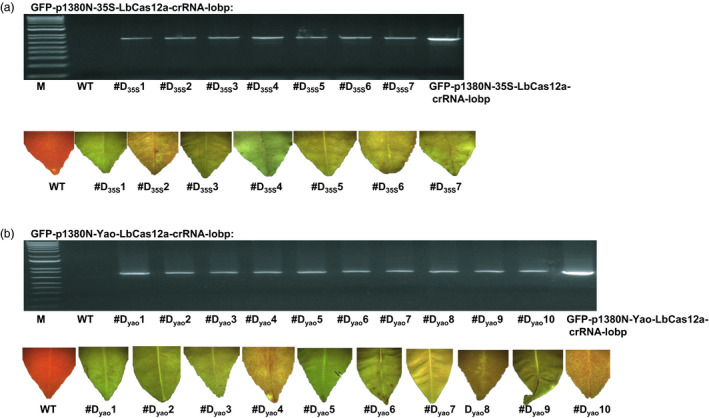

The Duncan epicotyls were transformed by Agrobacterium cells containing the binary vector. A total of seven GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐transformed Duncan plants (#D35s1 to #D35s7) were generated, and ten GFP‐p1380N‐Yao‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp transformants (#Dyao1 to #Dyao10) were generated. GFP fluorescence was detected in all of the transgenic plants (Figure 4a and b). Using Npt‐Seq‐5 and 35T‐3 as a pair of primers, the transgenic Duncan plants were further verified by PCR amplification (Figure 4a and b). As expected, a band measuring 750 bp was observed in transgenic plants and the positive plasmid control, whereas there was no band in the wild‐type Duncan grapefruit sample (Figure 4a and b). The results indicated that LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐transformed Duncan plants were successfully established.

Figure 4.

Analysis of CRISPR‐LbCas12a‐transformed Duncan grapefruit. (a) Seven GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐transformed Duncan grapefruit plants (from #D35s1 to #D35s7) were evaluated by PCR analysis using the primers Npt‐Seq‐5 and 35T‐3. The plasmid GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp was used as a positive control. The seven plants were GFP‐positive. The wild‐type grapefruit plant did not show GFP. (b) Ten GFP‐p1380N‐Yao‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐transformed Duncan plants (from #DY ao1 to #DY ao10) were tested by PCR analysis and GFP observation. M, 1 kb DNA ladder; WT, wild type.

Analysis of LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐mediated indels in Duncan transformants

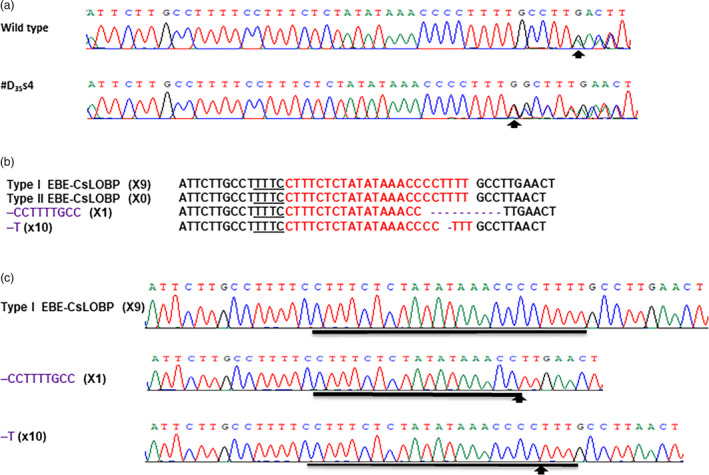

The PCR products were sequenced directly to evaluate the LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐mediated indels in seventeen transgenic Duncan plants (Table 1). The results indicated that one transgenic Duncan line, #D35s4, contains changes in its chromatogram in comparison with that of the wild type (Figure 5a), whereas the other lines exhibited no changes (Table 1). It should be noted that Type I CsLOBP has one more G nucleotide next to EBEPthA4 than the Type II CsLOBP (Figure 3), and thus, double peaks were present from the unique guanine in wild‐type Duncan plants (Figure 5a; Jia et al., 2016).

Table 1.

LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐mediated indel analysis and canker resistance of transgenic Duncan

| Analysis | Lines | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #D35s1 | #D35s2 | #D35s3 | #D35s4 | #D35s5 | #D35s6 | #D35s7 | #Dyao1 | #Dyao2 | #Dyao3 | #Dyao4 | #Dyao5 | #Dyao6 | #Dyao7 | #Dyao8 | #Dyao9 | #Dyao10 | |

| Direct sequencing of PCR products | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Mutant | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type | Wild type |

| Sequencing of 20 random colonies | 3 mutants | No mutant | No mutant | 11 mutants | No mutant | No mutant | 3 mutants | No mutant | No mutants | No mutant | No mutant | No mutant | No mutant | No mutant | No mutant | No mutant | No mutant |

| Mutation rates | 15% | 0 | 0 | 55% | 0 | 0 | 15% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Xcc (PthA4)‐eliciting canker | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| dCsLOB1.4‐eliciting canker | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Figure 5.

CRISPR‐LbCas12a‐mediated CsLOBP indels in transgenic Duncan #D35s4. (a) The chromatograms of direct PCR product sequencing. Using the primers LOBP2 and LOBP3, the CsLOBPs were amplified from wild‐type Duncan and #D35s4, and the CsLOB4 primer was employed for direct sequencing. The beginnings of double peaks are highlighted by arrows. (b) Targeted CsLOBP mutations directed by GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp in transgenic Duncan #D35s4. The crRNA‐targeted sequence is shown in red, and the indels are highlighted in purple. (c) CRISPR‐LbCas12a‐mediated indel chromatograms in CsLOBP. Arrows are used to indicate the mutation sites.

Next, colony sequencing was performed to analyse CRISPR‐LbCas12a‐mediated mutations in transgenic Duncan grapefruit plants. Among the 20 colonies sequenced for each transgenic line, no mutations were observed in all the Yao‐LbCas12a‐transformed Duncan plants and four 35S‐LbCas12a‐transformed lines (#D35s2, #D35s3, #D35s5 and D35s6; Table 1), whereas #D35s1, #D35s4 and #D35s7 contained indels (Figure 5b and c, Figure S2). The mutation rates of #D35s1, #D35s4 and #D35s7 were 15%, 55% and 15%, respectively (Table 1). The Type II EBE‐CsLOBPs were 100% mutated according to Figure 5. All the mutation genotypes were deletions (Figure 5b and c, Figure S2). Specifically, the deletion of one thymine took place only in Type II EBE‐CsLOBP among the sequenced colonies, whereas a longer deletion occurred only on Type I EBE‐CsLOBP (Figure 5b and c, Figure S2). Most importantly, as expected, both Type I EBE‐CsLOBP and Type II EBE‐CsLOBP were readily modified by the single crRNA‐targeting sequence (Figure 5b and c, Figure S2).

#D35s4 transgenic plant alleviating XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4 infection

Seventeen transgenic Duncan plants were treated with Xcc at a concentration of 5 × 108 CFU/mL. Canker symptoms were observed in all transgenic lines, similar to the wild‐type control plants, at 5 days post‐inoculation (DPI; Table 1). The results are consistent with those of a previous study, in which canker could readily develop on Cas9/sgRNA:CsLOBP1‐transformed Duncan plants harbouring one intact CsLOBP allele (Jia et al., 2016).

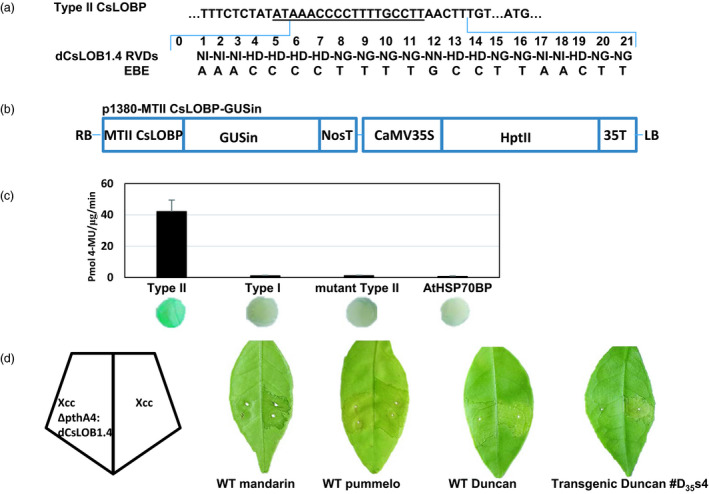

In our previous study, dCsLOB1.1 and dCsLOB1.2 were developed to activate two types of CsLOBPs (Hu et al., 2014). The dCsLOB1.1 binding site is 5′TAAAGCAGCTCCTCCTC3′, and the dCsLOB1.2 recognition sequence is 5′TATAAACCCCTTTTGCCTT3′ (Figure 3). Later, dCsLOB1.3 was built to recognize the Type I EBE‐CsLOBP allele only, the binding sequence of which is 5′CCTTTTGCCTTGAACTTT3′ (Figure 3; Jia et al., 2016). Two Cas9/sgRNA:CsLOBP1‐transformed lines with the highest mutation rate for the Type I EBE‐CsLOBP allele could resist XccΔpthA4: dCsLOB1.3 (Jia et al., 2016). Here, we constructed a novel dTALE, dCsLOB1.4 (Figure 6a), the repeat variable di‐residues (RVDs) of which specifically bind to the 21‐nucleotide sequence 5′TAAACCCCTTTTGCCTTAACTT3′ in the Type II CsLOBP (Figures 3, 6a), whereas one extra ‘G’ nucleotide is present in the Type I CsLOBP and one ‘T’ nucleotide is absent from the mutated Type II CsLOBP compared to the wild‐type II CsLOBP.

Figure 6.

Transgenic Duncan #D35s4 resistant against Xcc306ΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4. (a) Artificial dTALE dCsLOB1.4 was developed to activate Type II CsLOBP specifically. RVDs of the artificial dTALE dCsLOB1.4 bind to AAACCCCTTTTGCCTTAACTT, 2 bp downstream of EBE pthA4‐TII CsLOBP, which is underlined. (b) A schematic diagram of p1380‐MTII CsLOBP‐GUSin. MTII CsLOBP, mutant Type II CsLOBP; GUSin, the intron‐containing β‐glucuronidase; and HptII, the coding sequence of hygromycin phosphotransferase II. (c) Via Xcc306ΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4‐facilitated agroinfiltration, a quantitative GUS assay and GUS histochemical staining were used to study the effects of Xcc‐derived dCsLOB1.4 on CsLOBPs. Notably, only under the control of Type II CsLOBP could GUS expression be activated. The experiments were repeated twice. (d) Five days post‐Xcc inoculation, citrus canker symptoms were observed on mandarin (containing Type I CsLOBP), pummelo (containing Type II CsLOBP), Duncan grapefruit (containing Type I CsLOBP and Type II CsLOBP) and transgenic Duncan #D35s4 (containing Type I CsLOBP and mutant Type II CsLOBP) grapefruit, since the PthA4 derived from Xcc could activate Type I CsLOBP and Type II CsLOBP. Five days after Xcc306ΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4 treatment, citrus canker symptoms were not observed on mandarin and transgenic Duncan #D35s4, since dCsLOB1.4 could not activate Type I CsLOBP and mutant Type II CsLOBP.

The designed TALE dCsLOB1.4 was developed here to specifically activate Type II EBE‐CsLOBP (Figure 6a), but not the Type I CsLOBP and mutant Type II CsLOBP. To confirm dCsLOB1.4‐specific recognition, the binary vectors p1380‐AtHSP70BP‐GUSin, p1380‐TI CsLOBP‐GUSin, p1380‐TII CsLOBP‐GUSin and p1380‐MTII CsLOBP‐GUSin (Figure 6b) were used to perform an XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4‐facilitated agroinfiltration. It should be noted that p1380‐AtHSP70BP‐GUSin was used as a negative control (Jia and Wang, 2014b). As expected, only Type II CsLOBP‐driven GUS expression could be specifically activated (Figure 6c), whereas neither MTII CsLOBP‐GUSin nor TI CsLOBP‐GUSin was activated (Figure 6c). The results indicated that dCsLOB1.4 specifically recognizes the Type II CsLOBP. The mandarin has two Type I EBE‐CsLOBP alleles, and the pummelo contains two Type II EBE‐CsLOBP alleles (Wu et al., 2014). In the presence of XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4, canker symptoms develop on pummelo but not on mandarin (Figure 6d). The results further confirmed that, as expected, dCsLOB1.4 specifically activates Type II EBE‐CsLOBP, resulting in canker on pummelo. After XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4 infection, #D35s4 showed alleviated XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4 infection owing to its 100% mutation on Type II EBE‐CsLOBP (Figures 5b, c and 6d, Table 1), whereas canker symptoms were observed in other transgenic Duncan lines (Table 1).

Potential off‐targets of LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp

Based on the sweet orange genome, the potential off‐targets generated by LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp were analysed (mismatch number = 2, RNA bulge size = 1) using a web tool (http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/; Bae et al., 2014). All the potential off‐targets using 1 or 2 mismatches are located at the LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐targeting site (Figure S3), indicating that there might be no potential off‐targets of LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp. However, we could not totally rule out the possibility that there could be mutations in potential off‐targets with three or more mismatches.

Discussion

For the first time, we demonstrated that a citrus genome could be modified specifically using either the transient expression of LbCas12a via Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration or the constitutive expression of LbCas12a in transgenic Duncan plants.

All of the mutations generated by CRISPR‐LbCas12a in citrus were deletions. In the LbCas12a‐mediated mutations of CsPDS and Type I CsLOBP, the indels were relatively long deletions, which are consistent with those in other plants (Begemann et al., 2017; Endo et al., 2016; Ferenczi et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017a,b,c; Xu et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2017). The longer deletions could be attributable to 5′ overhangs resulting from the stagger cutting of Cas12a at sites distal to the PAM (Tang et al., 2017; Zetsche et al., 2015). Interestingly, all of the Type II CsLOBP mutations generated by LbCas12a were 1 bp deletions among the colonies that were sequenced (Figure 5b and c, Figure S2A), and they are similar to the short indels (1–2 bp) induced by SpCas9 in citrus (Jia et al., 2016, 2017b; Peng et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017).

The mutation frequencies of #D35s1, #D35s4 and #D35s7 were 15%, 55% and 15%, respectively. The average mutant rate in #D35s1, #D35s4 and #D35s7 was 28.3%, which is similar to that of FnCas12a‐transformed tobacco (28.2%), but lower than that of FnCas12a‐transformed rice (47.2%; Endo et al., 2016). The authors suggested that the different processes, which were employed to develop transgenic tobacco and rice, might be the cause for the different mutation frequencies (Endo et al., 2016). Additionally, a low mutation efficacy of 2% was observed for citrus when LbCas12a transient expression was used. The mutation frequencies induced by the transient expression of AsCas12a ranged from 0.6% to 10%, whereas the mutation frequencies mediated by LbCas12a ranged from 15% to 25% in rice (Tang et al., 2017). A nearly 100% biallelic mutation efficiency was observed for LbCas12a‐mediated genome editing in rice, whereas the biallelic mutation efficiency from LbCas12a was only 5% in citrus. The lower mutation efficacy from LbCas12a in citrus might result from the different crRNA designs that were used (Tang et al., 2017). This finding signifies the need to improve the efficacy of LbCas12a‐mediated genome editing.

Unexpectedly, no indels were detected in the Yao‐LbCas12a‐transformed Duncan plants. The Yao promoter was used to drive SpCas9 expression for high‐efficiency citrus genome editing in a previous report (Zhang et al., 2017). There are some differences between the two studies. In the previous study, Carrizo was transformed by Yao‐SpCas9, and sgRNAs were driven by AtU6‐26 (Zhang et al., 2017), whereas Duncan grapefruit was transformed by Yao‐LbCas12a, and AtU6‐1 and CaMV 35S were employed to drive crRNA (Figure 1c). It remains unclear whether these differences affect the mutation efficiency induced by SpCas9 and LbCas12a. More work is needed to clarify whether the Yao promoter is suitable for driving the Cas12a. Interestingly, heat treatment has been used to enhance genome editing in Cas9‐transformed citrus (LeBlanc et al., 2018). It is worth testing whether heat shocks can enhance the mutations in LbCas12a‐transformed citrus. In addition, several novel strategies, including the ribozyme processing strategy (Tang et al., 2017), the crRNA processing strategy (Wang et al., 2018) and the single transcript unit strategy (Tang et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018), have been developed to enhance plant genome editing. Undoubtedly, these strategies might help to optimize the efficacy of citrus genome editing in future.

Intriguingly, CRISPR‐LbCas12a ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) have already been used to edit the genomes to generate transgene‐free mutations in soybeans and tobacco (Kim et al., 2017). The delivery of CRISPR‐LbCas12a RNPs bypasses the need to develop a system for removing foreign DNAs from genetically modified plants. It would be worth testing whether Cas12a RNPs could be harnessed to generate foreign DNA‐free genome‐modified citrus.

In summary, we presented our recent progress in using CRISPR‐LbCas12a to edit a citrus genome via Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration and stable transformation. Because of its unique targeted mutagenesis features, CRISPR‐LbCas12a can undoubtedly enhance the scope and specificity of citrus genome editing, which was supported by this study. To enhance the scope of citrus genome editing, we successfully used single crRNA targeting to modify two alleles of EBEPthA4‐CsLOBPs. Therefore, CRISPR‐LbCas12a should be regarded as a powerful complementary tool for citrus genome engineering, in addition to CRISPR‐SpCas9 and CRISPR‐SaCas9 (Jia and Wang, 2014a; Jia et al., 2016, 2017a,b; Peng et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017).

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The CaMV 35S promoter was amplified using the primers CaMV35‐5‐SbfI (5′‐AGGTCCTGCAGGTCCCCAGATTAGCCTTTTCAATTT‐3′) and CaMV35‐3‐KpnI‐BamHI (5′‐AGGTGGATCCGGTACCTATCGTTCGTAAATGGTGAAAATT‐3′) and then cloned into SbfI‐BamHI‐digested GFP‐p1380N‐Cas9 to produce GFP‐p1380N‐KpnI‐Cas9. GFP‐p1380N‐Cas9 was constructed in a previous study (Jia et al., 2017a). LbCas12a harbouring a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and an HA tag at its C‐terminus was obtained from Addgene plasmid pY016 after a KpnI and EcoRI cut (Zetsche et al., 2015). The KpnI‐LbCas12a‐EcoRI fragment was inserted into KpnI‐EcoRI‐cut GFP‐p1380N‐KpnI‐Cas9 to generate GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a. By using Arabidopsis genomic DNA as a template, the Yao promoter was amplified with a pair of primers, Yao‐5‐SbfI (5′‐AGGTCCTGCAGGATGGGAAATTCATTGAAAACCCT‐3′) and Yao‐3‐KpnI (5′‐AGGTGGTACCGGATCCTTTCTTCTTCTCGTTGTTGTACTTCAT‐3′). The SbfI‐KpnI‐digested Yao promoter was cloned into SbfI‐KpnI‐cut GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a to obtain GFP‐p1380N‐Yao‐LbCas12a. The Nos terminator (NosT) was amplified using NosT‐5‐EcoRI (5′‐AGGATCCACCGGTGCACGAATTCCGAATTTCCCCGATCGTTCAA‐ 3′) and NosT‐3‐XhoI‐AscI‐XbaI‐PmeI (5′‐AGTTTAAACTCTAGACAAGGCGCGCCATTTAAATCTCGAG CCGATCTAGTAACATAGATGACAC‐3′). After EcoRI digestion, NosT was inserted into EcoRI‐SfoI‐digested pUC18 to generate pUC‐NosT‐MCS.

From p1380N‐sgRNA (Jia et al., 2017a), the CaMV 35S promoter was amplified using the primers CaMV35‐5‐XhoI (5′‐ACTCGAGACTAGTACCATGGTGGACTCCTCTTAA‐3′) and CaMV35‐crRNA‐3 (5′‐phosphorylated CTACACTTAGTAGAAATTCCTCTCCAAATGAAA TGAACTTCCT‐ 3′), and the crRNA‐cspds‐NosT fragment was amplified using the primers crRNA‐cspds‐P (5′‐phosphorylated‐ATAGGTAACTGAAGCTTGAGGATATGAATTTCCCCGA TCGTTCAAACATTTG‐3′) and NosT‐3‐AscI (5′‐ACCTGGGCCCGGCGCGCCGATCTAGT AACATAGATGA‐3′). Through three‐way ligation, XhoI‐cut CaMV35S and AscI‐digested crRNA‐cspds‐NosT were inserted into XhoI‐AscI‐treated pUC‐NosT‐MCS to build pUC‐NosT‐crRNA‐cspds. Subsequently, the EcoRI‐NosT‐crRNA‐cspds‐NosT‐PmeI fragment was cloned into EcoRI‐PmeI‐cut GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a to construct GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐cspds (Figure 1a), which was designed to edit the sequence located 15 641 bp downstream of the ATG in CsPDS (Figure S1).

Similarly, the CaMV 35S promoter was PCR‐amplified using the primers CaMV35‐5‐XhoI and CaMV35‐crRNA‐3, and the crRNA1‐lobp‐NosT was PCR‐amplified using the primers crRNA‐lobp‐P (5′‐phosphorylated‐ ATCTTTCTCTATATAAACCCCTTTTGAATTTCCCCG ATCGTTCAAACATTTG‐3′) and NosT‐3‐AscI. XhoI‐cut CaMV35S and AscI‐digested crRNA‐lobp‐NosT were inserted into XhoI‐AscI‐cut pUC‐NosT‐MCS to build pUC‐NosT‐35S‐crRNA‐lobp through three‐way ligation. With GFP‐p1380N‐SaCas9/35S‐sgRNA1:AtU6‐sgRNA2 as a template (Jia et al., 2017a), the AtU6‐1 was amplified using AtU6‐1‐5‐AscI (5′‐AGGT GGCGCGCCTCTTACAGCTTAGAAATCTCAAA‐3′) and AtU6‐1‐crRNA‐3 (5′‐phosphorylated‐CTACACTTAGTAGAAATTCAATCACTACTTCGTCTCTAACCATATA‐3′). Using crRNA‐lobp‐P and NosT‐3‐SpeI (5′‐AGGTACTAGTCCGATCTAGTAACATAGA TGACA‐3′), the crRNA2‐lobp‐NosT fragment was amplified. Through three‐way ligation, AscI‐cut AtU6‐1 and SpeI‐digested crRNA2‐lobp‐NosT were inserted into AscI‐XbaI‐treated pUC‐NosT‐35S‐crRNA‐lobp to form pUC‐NosT‐crRNA‐lobp. Finally, the EcoRI‐NosT‐35S‐crRNA‐lobp‐NosT‐AtU6‐1‐crRNA‐lobp‐NosT‐PmeI fragment was cloned into EcoRI‐PmeI‐cut GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a to construct GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp (Figure 1b) or into EcoRI‐PmeI‐cut GFP‐p1380N‐Yao‐LbCas12a to form GFP‐p1380N‐Yao‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp (Figure 1c).

Using forward primer LOBP1 and reverse primer LOBP2 (Jia et al., 2016), the mutant Type II CsLOBP, which contains a thymine deletion, was amplified from transgenic line #D35s4. After sequencing, the HindIII‐BamHI‐digested PCR fragment was inserted into HindIII‐BamHI‐treated p1380‐35S‐GUSin to form binary vectors p1380‐MTII CsLOBP‐GUSin (Figure 6b). Binary vectors p1380‐AtHSP70BP‐GUSin, p1380‐TI CsLOBP‐GUSin and p1380‐TII CsLOBP‐GUSin were developed previously (Jia et al., 2016).

Through the electroporation method, the binary vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105. Recombinant Agrobacterium cells were cultivated for Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration or epicotyl citrus transformation.

Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration in Duncan grapefruit

The Duncan grapefruit (Citrus paradisi) was grown in a greenhouse at approximately 27 °C and then pruned for uniform shooting before Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration.

As described before (Jia and Wang, 2014b), the Duncan leaves were first inoculated with a culture of actively growing Xcc, which was resuspended in sterile tap water at a concentration of 5 × 108 CFU/mL. Twenty‐four hours later, the leaf areas, which were pretreated with XccΔgumC, were subjected to agroinfiltration with recombinant Agrobacterium cells harbouring GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐cspds. Four days after the agroinfiltration, the genomic DNA was extracted from the treated leaves. Similarly, the XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4‐treated leaf areas were agroinfiltrated with recombinant Agrobacterium containing p1380‐TI CsLOBP‐GUSin, p1380‐TII CsLOBP‐GUSin, p1380‐MTII CsLOBP‐GUSin or p1380‐AtHSP70BP‐GUSin. Four days later, the leaves were collected for a GUS assay.

Agrobacterium‐mediated Duncan grapefruit transformation

A citrus transformation was performed as reported before (Jia et al., 2017b). In summary, Duncan epicotyl explants were coincubated with recombinant Agrobacterium cells harbouring a binary vector, with either GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp or GFP‐p1380N‐Yao‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp. Five weeks later, all the explants were inspected for GFP fluorescence. Later, GFP‐positive sprouted shoots were micrografted onto ‘Carrizo’ citrange rootstock plants [C. sinensis (L.) Osbeck × Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.] for continuous cultivation and further analysis.

The transgenic plants were subjected to PCR analysis with a pair of primers, Npt‐Seq‐5 (5′‐TGTGCTCGACGTTGTCACTGAAGC‐3′) and 35T‐3 (5′‐TTCGGGGGATCTGGATTT TAGTAC‐3′).

PCR amplification of mutagenized CsPDS and CsLOBP

Genomic DNA was extracted from the Duncan leaves that were treated with Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration or each transgenic Duncan line.

To test the GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐cspds‐mediated indels in the CsPDS gene, PCR was performed using the primers CsPDS‐5‐P7 (5′‐TGGCAATGTGATTGACGGAGATGC‐3′) and CsPDS‐3‐P8 (5′‐ATGAGTCCTCCTTGTTACTTCAGT‐3′), which flanked the targeted site of CsPDS. The template was genomic DNA, which was extracted from Duncan leaves treated with GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐cspds. Using blunt‐end cloning, the CsPDS PCR products were ligated into a PCR Blunt II‐TOPO vector (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). A total of one hundred random colonies were chosen for DNA sequencing. A Chromas Lite program was employed to analyse the sequencing results.

To analyse the LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐mediated CsLOBP mutations, PCR was performed using a pair of primers, LOBP3 (5′‐AGGTAAGCTTATTCATATTAACGTTATCAATGATT‐3′) and LOBP2 (5′‐ACCTGGATCCTTTTGAGAGAAGAAAACTGTTGGGT‐3′; Jia et al., 2016). Following purification, the PCR products were subjected to either ligation or direct PCR product sequencing using the primer CsLOB4 (5′‐CGTCATTCAATTAAAATTAATGAC‐3′). After transformation, 20 random colonies for each transgenic Duncan line were chosen for detailed sequencing. The sequencing results were further analysed using the Chromas Lite program.

GFP detection

A Zeiss Stemi SV11 dissecting microscope (Thornwood, NY) equipped with an Omax camera was used to study the GFP‐p1380N‐35S‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐transformed and GFP‐p1380N‐Yao‐LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp‐transformed Duncan plants under illumination by a Stereo Microscope Fluorescence Adapter (NIGHTSEA). Subsequently, the transgenic plant leaves were photographed with Omax ToupView software.

GUS assay

Four days after the Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration, the histochemical staining of GUS and a quantitative GUS assay were performed on the treated citrus leaves as described previously (Jia and Wang, 2014b).

Canker symptom assay in citrus

All the citrus plants were grown in a greenhouse. Prior to the canker pathogen inoculation, the Duncan grapefruit (Citrus paradisi), pummelo (C. maxima), Willowleaf mandarin (Citrus reticulata) and transgenic Duncan grapefruit plants were pruned to promote shooting. With a needleless syringe, the same aged leaves were inoculated with Xcc or XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.4, which were resuspended in sterile tap water (5 × 108 CFU/mL). The ensuing canker development was observed and photographed at different time points.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Schematic map of CsPDS.

Figure S2 CRISPR‐LbCas12a‐mediated CsLOBP indels in transgenic Duncan #D35s1 and #D35s7.

Figure S3 Potential off‐targets of LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp in transgenic Duncan grapefruit.

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by USDA‐NIFA Plant Biotic Interactions Program 2017‐67013‐26527, Florida Citrus Research and Development Foundation, and Florida Citrus Initiative.

References

- Bae, S. , Park, J. and Kim, J.S. (2014) Cas‐OFFinder: a fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off‐target sites of Cas9 RNA‐guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics, 30, 1473–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begemann, M.B. , Gray, B.N. , January, E. , Gordon, G.C. , He, Y. , Liu, H. , Wu, X. et al. (2017) Precise insertion and guided editing of higher plant genomes using Cpf1 CRISPR nucleases. Sci. Rep. 7, 11606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo, A. , Masafumi, M. , Kaya, H. and Toki, S. (2016) Efficient targeted mutagenesis of rice and tobacco genomes using Cpf1 from Francisella novicida. Sci. Rep. 6, 38169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ference, C.M. , Gochez, A.M. , Behlau, F. , Wang, N. , Graham, J.H. and Jones, J.B. (2018) Recent advances in the understanding of Xanthomonas citri ssp. citri pathogenesis and citrus canker disease management. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 1302–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenczi, A. , Pyott, D.E. , Xipnitou, A. and Molnar, A. (2017) Efficient targeted DNA editing and replacement in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii using Cpf1 ribonucleoproteins and single‐stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 114, 13567–13572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. , Foden, J.A. , Khayter, C. , Maeder, M.L. , Reyon, D. , Joung, J.K. and Sander, J.D. (2013) High‐frequency off‐target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR‐Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 822–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. , Zhang, J. , Jia, H. , Sosso, D. , Li, T. , Frommer, W.B. , Yang, B. et al. (2014) Lateral organ boundaries 1 is a disease susceptibility gene for citrus bacterial canker disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, E521–E529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X. , Wang, C. , Liu, Q. , Fu, Y. and Wang, K. (2017) Targeted mutagenesis in rice using CRISPR‐Cpf1 system. J. Genet Genom. 44, 71–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam, W. (2018) CRISPR‐Cas9; an efficient tool for precise plant genome editing. Mol. Cell. Probes, 39, 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H. and Wang, N. (2014a) Targeted genome editing of sweet orange using Cas9/sgRNA. PLoS ONE, 9, e93806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H. and Wang, N. (2014b) Xcc‐facilitated agroinfiltration of citrus leaves: a tool for rapid functional analysis of transgenes in citrus leaves. Plant Cell Rep. 33, 1993–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H. , Orbovic, V. , Jones, J.B. and Wang, N. (2016) Modification of the PthA4 effector binding elements in Type I CsLOB1 promoter using Cas9/sgRNA to produce transgenic Duncan grapefruit alleviating XccΔpthA4:dCsLOB1.3 infection. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 1291–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H. , Xu, J. , Orbović, V. , Zhang, Y. and Wang, N. (2017a) Editing citrus genome via SaCas9/sgRNA system. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H. , Zhang, Y. , Orbović, V. , Xu, J. , White, F.F. , Jones, J.B. and Wang, N. (2017b) Genome editing of the disease susceptibility gene CsLOB1 in citrus confers resistance to citrus canker. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 817–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. , Kim, J. , Hur, J.K. , Been, K.W. and Yoon, S.H. (2016) Genome‐wide analysis reveals specificities of Cpf1 endonucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 863–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. , Kim, S.T. , Ryu, J. , Kang, B.C. , Kim, J.S. and Kim, S.G. (2017) CRISPR/Cpf1‐mediated DNA‐free plant genome editing. Nat. Commun. 8, 14406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstiver, B.P. , Tsai, S.Q. , Prew, M.S. , Nguyen, N.T. , Welch, M.M. , Lopez, J.M. , McCaw, Z.R. et al. (2016) Genome‐wide specificities of CRISPR‐Cas Cpf1 nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 869–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc, C. , Zhang, F. , Mendez, J. , Lozano, Y. , Chatpar, K. , Irish, V.F. and Jacob, Y. (2018) Increased efficiency of targeted mutagenesis by CRISPR/Cas9 in plants using heat stress. Plant J. 93, 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín‐Pizarro, C. and Posé, D. (2018) Genome editing as a tool for fruit ripening manipulation. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno‐Mateos, M.A. , Fernandez, J.P. , Rouet, R. , Vejnar, C.E. , Lane, M.A. , Mis, E. , Khokha, M.K. et al. (2017) CRISPR‐Cpf1 mediates efficient homology‐directed repair and temperature‐controlled genome editing. Nat. Commun. 8, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, A. , Chen, S. , Lei, T. , Xu, L. , He, Y. , Wu, L. , Yao, L. et al. (2017) Engineering canker‐resistant plants through CRISPR/Cas9‐targeted editing of the susceptibility gene CsLOB1 promoter in citrus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 1509–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port, F. and Bullock, S.L. (2016) Augmenting CRISPR applications in Drosophila with tRNA‐flanked sgRNAs. Nat. Methods, 13, 852–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X. , Lowder, L.G. , Zhang, T. , Malzahn, A.A. , Zheng, X. , Voytas, D.F. , Zhong, Z. et al. (2017) A CRISPR‐Cpf1 system for efficient genome editing and transcriptional repression in plants. Nat. Plants, 3, 17018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X. , Ren, Q. , Yang, L. , Bao, Y. , Zhong, Z. , He, Y. , Liu, S. et al. (2018) Single transcript unit CRISPR 2.0 systems for robust Cas9 and Cas12a mediated plant genome editing. Plant Biotechnol. J. 10.1111/pbi.13028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, R. and Licciardello, C. (2014) A genealogy of the citrus family. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 640–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. and Trivedi, P. (2013) Citrus Huanglongbing – an old problem with an unprecedented challenge. Phytopathology, 103, 652–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. , Mao, Y. , Lu, Y. , Tao, X. and Zhu, J.K. (2017a) Multiplex gene editing in rice using the CRISPR‐Cpf1 system. Mol. Plant, 10, 1011–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. , Pierson, E.A. , Setubal, J.C. , Xu, J. , Levy, J.G. , Zhang, Y. , Li, J. et al. (2017b) The Candidatus Liberibacter‐Host interface: insights into pathogenesis mechanisms and disease control. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 55, 451–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. , Stelinski, L.L. , Pelz‐Stelinski, K.S. , Graham, J.H. and Zhang, Y. (2017c) Tale of the huanglongbing disease pyramid in the context of the citrus microbiome. Phytopathology, 107, 380–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. , Mao, Y. , Lu, Y. , Wang, Z. , Tao, X. and Zhu, J.‐K. (2018) Multiplex gene editing in rice with simplified CRISPR‐Cpf1 and CRISPR‐Cas9 systems. J. Int. Plant Biol. 60, 626–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.A. , Prochnik, S. , Jenkins, J. , Salse, J. , Hellsten, U. , Murat, F. , Perrier, X. et al. (2014) Sequencing of diverse mandarin, pummelo and orange genomes reveals complex history of admixture during citrus domestication. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 656–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q. , Chen, L.L. , Ruan, X. , Chen, D. , Zhu, A. , Chen, C. , Bertrand, D. et al. (2013) The draft genome of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). Nat. Genet. 45, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R. , Qin, R. , Li, H. , Li, D. , Li, L. , Wei, P. and Yang, J. (2016) Generation of targeted mutant rice using a CRISPR‐Cpf1 system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 713–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R. , Qin, R. , Li, H. , Li, J. , Yang, J. and Wei, P. (2018) Enhanced genome editing in rice using single transcript unit CRISPR‐LbCpf1 systems. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 553–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X. , Biswal, A.K. , Dionora, J. , Perdigon, K.M. , Balahadia, C.P. , Mazumdar, S. , Chater, C. et al. (2017) CRISPR‐Cas9 and CRISPR‐Cpf1 mediated targeting of a stomatal developmental gene EPFL9 in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 36, 745–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetsche, B. , Gootenberg, J.S. , Abudayyeh, O.O. , Slaymaker, I.M. , Makarova, K.S. , Essletzbichler, P. , Volz, S.E. et al. (2015) Cpf1 is a single RNA‐guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR‐Cas system. Cell, 163, 759–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetsche, B. , Heidenreich, M. , Mohanraju, P. , Fedorova, I. , Kneppers, J. , DeGennaro, E.M. , Winblad, N. et al. (2017) Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR‐Cpf1 using a single crRNA array. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 31–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F. , LeBlanc, C. , Irish, V.F. and Jacob, Y. (2017) Rapid and efficient CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in Citrus using the YAO promoter. Plant Cell Rep. 36, 1883–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Schematic map of CsPDS.

Figure S2 CRISPR‐LbCas12a‐mediated CsLOBP indels in transgenic Duncan #D35s1 and #D35s7.

Figure S3 Potential off‐targets of LbCas12a‐crRNA‐lobp in transgenic Duncan grapefruit.