Abstract

Introduction

There are pervasive racial disparities in access to living donor kidney transplantation, which for most patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) represents the optimal treatment. We previously developed a theory-driven, culturally sensitive intervention for African American (AA) patients with kidney disease called Living ACTS (About Choices in Transplantation and Sharing) as a DVD and booklet, and found this intervention was effective in increasing living donor transplant knowledge. However, it is unknown whether modifying this intervention for a Web-based environment is effective at increasing access to living donor transplantation.

Methods

We describe the Web-based Living ACTS study, a multicenter, randomized controlled study designed to test the effectiveness of a revised Living ACTS intervention in 4 transplant centers in the southeastern United States. The intervention consists of a Web site with 5 modules: Introduction, Benefits and Risks, The Kidney Transplant Process, Identifying a Potential Kidney Donor, and ACT Now (which encourages communication with friends and family about transplantation).

Results

This study will enroll approximately 800 patients from the 4 transplant centers. The primary outcome is the percentage of patients with at least 1 inquiry from a potential living donor among patients who receive Living ACTS as compared with those who receive a control Web site.

Conclusion

The results from this study are expected to demonstrate the effectiveness of an intervention designed to increase access to living donor transplantation among AA individuals. If successful, the Web-based intervention could be disseminated across the >250 transplant centers in the United States to improve equity in living donor kidney transplantation.

Keywords: education, intervention, kidney transplant

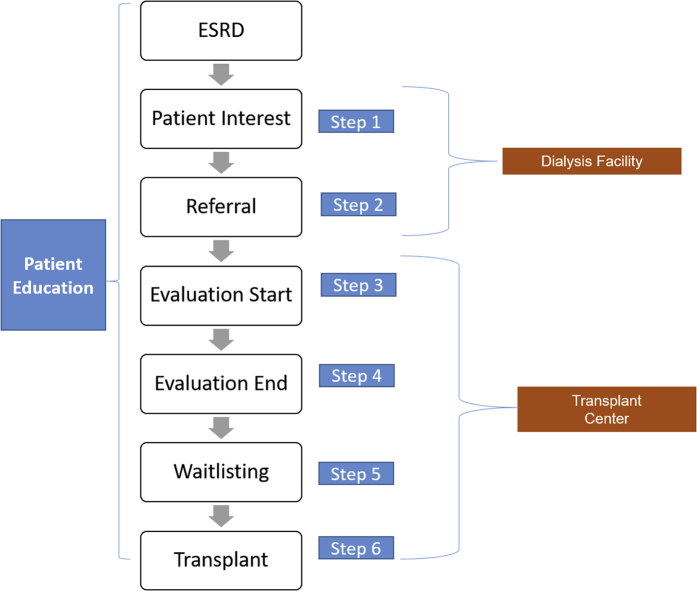

African American individuals (AAs) comprise 32% of the ESRD population1, 2 and have a disproportionately higher burden of ESRD than their white counterparts. Kidney transplantation is considered the optimal treatment for most patients with ESRD, but AAs are 24% less likely to receive a kidney transplant compared with white individuals.3 The relative odds of receiving a living donor kidney transplant (LDKT) are even lower.4 Disparities exist at each step in the transplantation process and can be attributed to patient, provider, and health system level barriers.5 For example, compared with white individuals, AAs are less likely to be educated about transplantation within a dialysis facility,6 express interest in receiving a transplant (step 1),6 receive a referral from a dialysis facility to a transplant center for transplant evaluation (step 2),7 start (step 3)8 and complete (step 4) the required medical evaluation at the transplant center, attain placement on the national deceased donor waiting list (i.e., waitlisting) (step 5),9 and receive an LDKT or diseased donor kidney transplant (step 6) (Figure 1).6, 8, 10, 11, 12

Figure 1.

Steps to kidney transplantation and role of dialysis facility and transplant center in facilitating transplant access. ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Patient barriers include lack of LDKT knowledge and awareness,13, 14, 15, 16 financial concerns,17, 18, 19, 20, 21 and religious beliefs that the body needs to remain whole to enter heaven.22, 23, 24 Another barrier to living donation is AAs’ distrust of the health care system in general and the organ allocation system specifically, due to historical and current abuses.25, 26 Moreover, potential kidney recipients may be reluctant to discuss LDKT with family members because of concerns of racial bias in the health care system, such as the belief that this bias could result in their kidney donors not receiving adequate transplant care.27, 28, 29 Health care providers’ attitudes and perceptions of the appropriateness of LDKT for their patients may also lead to lower LDKT rates and incomplete transplant evaluations.30, 31, 32 Nephrologists who treat predominantly minority ESRD populations spend less time providing patient education and counseling on LDKT compared with nephrologists with fewer minority patients,33 which may reflect providers’ attitudes about their patients’ suitability for transplant.32 Limited communication between dialysis facilities and transplant centers also can influence kidney transplant access.34 Although dialysis staff play a large role in education, generating interest in transplant (step 1), and referral for transplantation (step 2), staff also are essential in later transplant steps, via active partnering with transplant centers to help patients show up at the transplant center to start the medical evaluation (step 3), scheduling of medical tests and procedures required for evaluation completion (step 4), and maintaining patient health to ensure waitlisting (step 5; Figure 1).35

In an effort to reduce barriers, a recent national consensus conference on LDKT recommended collaborations among transplant centers, community organizations, dialysis facilities, and others.36 Technology was recommended as an educational tool for patients and their support systems,36 which has also been shown to be effective in several other Web-based kidney disease interventions.37, 38, 39, 40 Out of recognition for this needed improvement, dialysis facilities and transplant centers in ESRD Network 6 (Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina) are gradually implementing a new electronic application called the Transplant Referral Exchange (T-REX) to enhance communication between dialysis facilities and transplant centers. This novel electronic platform allows staff across health care settings to facilitate electronic referral (versus fax) of dialysis patients to transplant centers for evaluation and to monitor patients’ progress in the transplant process, including the tracking of education for LDKT. More specifically, the T-REX application allows dialysis staff to capture which specific transplant education materials they discussed with patients at the facility or provided for them to review on their own. On receipt of a referral for evaluation, transplant center staff also can view which transplant educational materials ESRD patients were previously exposed to at the dialysis facility and risk stratify which patients may need more intensive LDKT education during their evaluation. Additionally noted at the national consensus conference on LDKT, education on LDKT offered repeatedly throughout the disease progression and transplantation processes was also recommended as a higher priority among LDKT patients. To fulfill this recommendation, Living ACTS (About Choices in Transplantation and Sharing) was developed to serve as a culturally sensitive educational tool designed to address barriers to LDKT among AA patients with ESRD.

Study Design and Methods

Study Overview

The Living ACTS study is a 2-arm randomized trial to test the efficacy of the Web-based Living ACTS educational intervention administered to AA patients with ESRD being evaluated at 1 of 4 southeastern US transplant centers on improving living donor inquiries. All 4 transplant centers have plans to implement T-REX as a standard of care. Before initiation of study activities, the Living ACTS study will be registered on clinicaltrials.gov. This study was approved by Institutional Review Board at Emory University (IRB00098952).

Target Population, Study Sites, and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

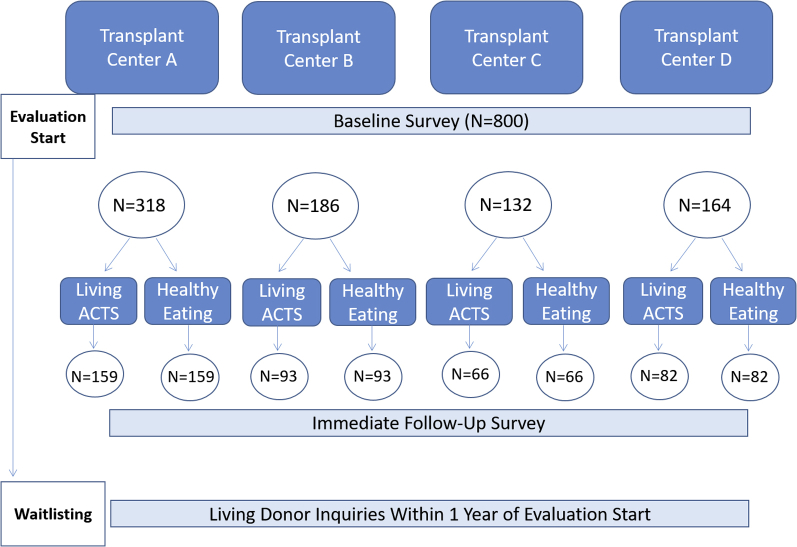

The study will be conducted in 4 kidney transplant centers with a high proportion of AA candidates but relatively low rates of living donor transplantation in the southeastern United States with an overall target enrollment of 800 patients. Enrollment will vary at each study site to account for the size of the patient population at each institution. To reduce sample bias, enrollment will be proportional to the number of AA candidates waitlisted at each transplant center: center A (n = 318), center B (n = 164), center C (n = 186), and center D (n = 132) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study design for Web-based Living ACTS (About Choices in Transplantation and Sharing) multicenter study.

All patients referred and scheduled for a transplant medical evaluation at 1 of the 4 study sites will be considered for study inclusion. Patients will be deemed eligible for this study if they meet the following criteria: (i) self-identified as AA or black, (ii) 18 to 65 years of age, (iii) body mass index <35 kg/m2, and (iv) English speaking.

Study Procedures

T-REX Application

Before starting patient recruitment at each study site, the T-REX application will be incorporated into transplant centers’ clinical workflow. The implementation of T-REX will occur in a staggered fashion to run parallel with patient recruitment and data collection, both of which are described in detail as follows. The implementation of T-REX among dialysis facilities in the southeast will be at the same time as the closest transplant center included in this study.

Patient Recruitment, Consent, and Study Enrollment

A rigorous screening process will be used to ensure that we target patients most likely to be medically eligible to receive a transplant. Patients will be recruited and screened for enrollment in 1 of 2 ways: (i) Flyers detailing the study procedures and components of the inclusion criteria will be posted in the lobby and patient rooms of the 4 transplant centers in our study. Flyers will also include a 1-800 telephone number for patients to contact the project coordinator to express interest and determine eligibility. (ii) The project coordinator will be sent a secure, password-protected report from each study site of all patients referred and scheduled for an upcoming evaluation, along with some key demographics (race, sex, age, and body mass index). Patients who meet eligibility criteria will be recruited at the transplant center during their evaluation appointment by trained research assistants who will also facilitate data collection. Patient recruitment will occur in a staggered fashion across study sites to coincide with data collection.

Patients who agree to participate will be provided with detailed study information. Written informed consent will be obtained from each patient before enrollment. After obtaining consent, research assistants will generate a unique study identification number and use a computer-generated 1:1 random allocation sequence to assign patients to 1 of 2 study arms. The research assistants will not be blind to study condition; however, they will not be involved with the main outcome analyses, and analysts will be blind to condition.

Study Arms and Delivery of Interventions

Following consent and randomization, patients will be administered a baseline questionnaire via iPad. The baseline questionnaire was designed to address each of the theoretical constructs in the Information-Motivation-Behavioral skills (IMB) Model41 described later in this article and includes questions about knowledge of LDKT, perceived motivation to discuss LDKT, confidence and comfort in discussing LDKT with their family, use of social media, and patient demographics. Following completion of the questionnaire, both groups will receive the usual center-specific standard-of-care education about kidney transplantation. Although there are some minor differences in the educational information that patients receive at each study site, the overall purpose is to inform transplant candidates and their families about the option of LDKT. In addition, patients randomized to the control arm will be provided an iPad to watch one, 12-minute National Kidney Foundation video and explore the Web site content that broadly discusses ESRD and transplantation, but does not specifically address LDKT and is not culturally sensitive to AA patients. Those assigned to the intervention group will have their usual center-specific standard of care kidney transplant education supplemented with the Living ACTS intervention (explained in detail later in this article).

Participants will be asked to spend a minimum of 15 minutes exploring the Web site and watching the embedded videos of either the control or intervention Web-based tool, depending on randomization. Immediately following patients’ exploration of the National Kidney Foundation or Living ACTS Web site, research assistants will administer a follow-up questionnaire. This questionnaire will be a shortened version of the baseline that omits demographic questions and adds measures of satisfaction with the Web site interventions. Both patient questionnaires will be administered through an iPad using SurveyMonkey, an electronic, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant surveying tool. Paper questionnaires will be used in the event that Internet access is unavailable or if a patient prefers a paper copy of the questionnaire. Study procedures are expected to take 45 minutes for each patient from start to finish. Patients will be offered a $30 gift card for their participation and intervention patients will be given a business card with the Living ACTS URL so that they can review it at their leisure and use the information to share their story on social media or in an e-mail to family and friends.

Development of the Living ACTS Intervention

Original Living ACTS Intervention

The original Living ACTS intervention was adapted from a community intervention that sought to improve public commitment to deceased donation,38, 42 and consisted of (i) a culturally sensitive DVD about LDKT, and (ii) a detailed booklet with LDKT information. Study materials were informed by the Two-Dimensional Model of Cultural Sensitivity in Public Health,43 which conceptualizes cultural sensitivity as surface and deep structure and addresses core cultural values relevant to the intervention, such as a focus on family. For this intervention, it was clearly important to include AA patients, families, and health care professionals in the video footage in order to achieve surface structure cultural sensitivity. However, we also emphasized the impact of LDKT on families, how family decision making around LDKT may occur, myths about organ recipients taking on characteristics of the donor, and the availability of resources to help finance a transplant. All of these factors, in addition to the desire for the DVD to build trust in transplant health care professionals, were expected to address relevant aspects of deep structure cultural sensitivity.

The intervention was also informed by the IMB Model, which posits that health behavior can be explained, and changed by providing specific information relevant to the behavior and increasing motivation to engage in the desired behavior. Specifically, the intervention sought to provide Information about the opportunities for and the process, risks, and benefits of LDKT. It also sought to increase Motivation to talk to one’s family about LDKT. Finally, it sought to improve the behavioral skills to engage family in a discussion of LDKT. In situations whereby the skills to engage in the behavior cannot be directly observed, this aspect of the model may be conceptualized as confidence (or self-efficacy) in the behavioral skills to engage in the behavior. These 3 constructs both directly and indirectly (through an increase in the skills to engage in the behavior) impact engagement in the desired behavior.41

The Living ACTS DVD consisted of a 30-minute video featuring health professionals providing information about the process, risks, and benefits of LDKT; personal stories from donor/recipient pairs about the transplant process; and sibling pairs describing how family dynamics and family discussion played a role in their decisions to pursue LDKT. The Living ACTS booklet complements the DVD by providing additional information, including Web site links to various resources, and tips for starting conversations about LDKT with family. Results of a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that Living ACTS increased knowledge of LDKT among AA patients with ESRD over a 6-month period.44

Revised Living ACTS Web Site

The current Living ACTS Web site intervention sought to maintain the theoretical underpinnings of the original intervention materials while changing only the delivery modality (Table 1). We did this by ensuring that key aspects of deep structure cultural sensitivity were maintained in the Web site (e.g., ensuring that the emphasis on family and trust-building in health care professionals were maintained). In addition, we ensured that all of the content of the Web site aligned with at least 1 of the 3 IMB constructs. The specific steps we took to revise the intervention are outlined as follows.

Table 1.

Comparison of Living ACTS intervention and control Web sites

| Intervention: Living ACTS: About Choices in Transplantation and Sharing |

Control: National Kidney Foundation: Transplantation |

|---|---|

| General premise: LDKT is a viable treatment option to explore among patients with end-stage renal disease. | General premise: Dialysis patients should consider kidney transplantation, but it is not right for everyone. |

| Vehicle: Factual information from health care providers, personal stories from donor/recipient pairs that emphasize the role of family in LDKT, practical skills for identifying a living donor | Vehicle: Factual information from health care providers, illustrations depicting immune system mechanisms, personal stories that emphasize the importance of medication adherence after transplantation. |

| Key points related to each tab (with relevant theoretical constructs in parentheses): | Key points: |

| 1. Introduction to LDKT: The text outlines the 6 steps to transplantation and provides specific information about LDKT (Information). The video provides an overview of LDKT by health care providers (Information). |

|

| 2. Benefits and Risks of LDKT: The text compares the benefits of living donor transplantation over deceased donor transplantation and presents risks to both the recipient and donor (Information). The video presents live donors and recipients sharing testimonies, focusing on their decision to pursue living donation, and medical providers discussing potential risks and benefits to both donor and recipient (Motivation). | |

| 3. The Kidney Transplant Process: The text describes the steps to becoming a living donor (Information). The video presents medical professionals and actual living donor pairs describing the transplant process for both the donor and recipient (Information). | |

| 4. Identifying a Potential Kidney Donor: The text describes general criteria for a living kidney donor and the types of LDKT (Information). The video presents the testing process for the donor and presents the decision-making process for both donors and recipients (Information). | |

| 5. ACT NOW: The text and video provide tools for talking to friends and family about LDKT, including a sample letter (Self-efficacy for the behavioral skills). |

LDKT, living donor kidney transplant.

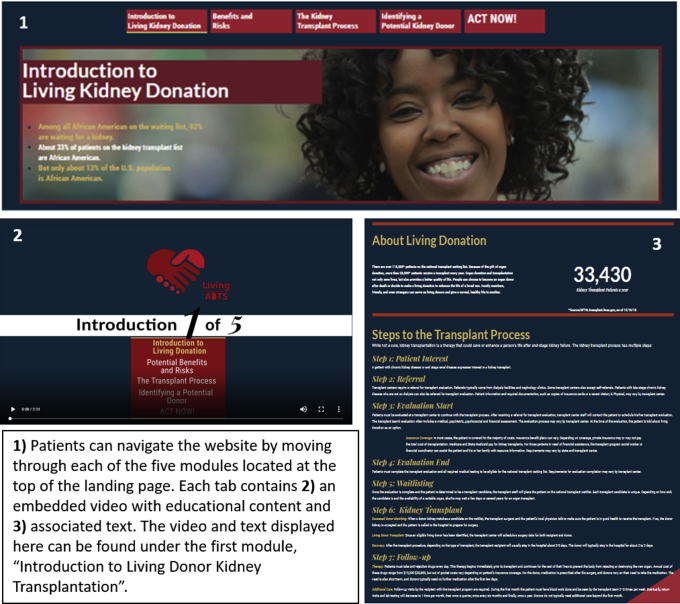

First, we modified Living ACTS to maximize its utility for a Web-based platform (http://projectlivingacts.org; Figure 3). We reorganized content from the original educational booklet and comprehensive video to construct 5 modules within the Web site: (i) Introduction to Living Kidney Donation, (ii) Benefits and Risks, (iii) The Kidney Transplant Process, (iv) Identifying a Potential Kidney Donor, (v) ACT NOW (emphasizing next steps for those ready to pursue LDKT as a treatment option and the use of social media to communicate with friends and family). Modules were separated by tabs within the Web site, such that participants could easily click on those topics most pertinent to their interests to get information related to LDKT. In addition, we reduced the 30-minute DVD to 5 videos (approximately 4–5 minutes in length, each) and included each shortened video on the tab most appropriate for the video content.

Figure 3.

Screenshots of Living ACTS (About Choices in Transplantation and Sharing) Web-based intervention, projectlivingacts.org.

Next we inserted additional video footage across module videos to include real-life characters exhibiting behaviors related to the topic of LDKT. These images included patients talking with physicians (to encourage patient-provider communication) and family members enjoying one another’s company (to reemphasize the importance of remaining healthy for others). Although the original Living ACTS video included mostly hosts speaking directly to the camera, including real-life interactions was important for the revised intervention in an attempt to maximize the ability of the intervention to increase motivation to engage in specific LDKT behaviors.41

Last, Tab 5 (ACT NOW tab) includes information on how patients in need of a kidney transplant may share their story with others. Given the pervasiveness of social media use, we found it imperative to include information about how patients in need of LDKT can safely and efficiently use social media platforms to share their interests in LDKT with others. We identified related recommendations from the National Kidney Foundation’s “Big Ask, Big Give” campaign, the United Network of Organ Sharing Blue Ribbon Advisory Board recommendations, and the Living Kidney Donors Network on how patients can use social media to share their “story,” or journey about kidney disease. The identified information was used to create a 5-minute video animation encouraging participants to “share their story” about kidney disease (rather than “asking” for a kidney), and including tips on how to use social media safely. This tab was explicitly developed to enhance participants’ behavioral skills to discuss LDKT with friends and family.

Web Site Testing and Refinement

Before finalizing the Living ACTS Web site, we conducted 5 individual, face-to-face interviews to get feedback on the initial Living ACTS Web site. Interview participants were selected based on their potential eligibility to be participants for the Living ACTS study (i.e., AA adults with ESRD). Our goal was to interview a broad cross-section of individuals to ensure that the Web site feedback represented a diverse pool of individuals.

Study staff conducted all individual interviews, and used an institutional review board–approved interview guide. First, participants were asked to explore the Web site at their leisure for approximately 15 minutes. After exploring the Web site, participants were asked to provide feedback on (i) design, (ii) comprehension, (iii) function, and (iv) cultural competence. Last, participants were asked to perform a series of tasks to ensure positive usability with the Living ACTS Web site. Interviewers observed how the participants interacted with the learning tool and asked a series of questions at the end of the interview to identify ways to improve user experiences. Feedback from the interviews was compiled and used to refine and finalize the intervention Web site (www.projectlivingacts.org).

Outcome Measures

Living Donor Inquires: Primary Outcome

The primary outcome of this study is the proportion of study patients with at least 1 living donor inquiry over the subsequent 12 months from enrollment (i.e., evaluation start). Inquiries are defined by all centers as a telephone inquiry to the transplant center study site of the study patient (each center has a separate telephone number for this purpose). These data are captured for all patients as a discrete field from the electronic medical record for each potential recipient. A designated staff member at each study site will abstract the date of a living donor inquiry and the donor inquiry ID for each potential recipient ID (i.e., study participant) in the 12-month period following enrollment.

Secondary Outcomes

Psychosocial outcomes captured in the baseline and follow-up questionnaires include measures of information, motivation, and behavioral skills as they relate to LDKT. These measures aim to assess the following: (i) knowledge and understanding of LDKT, (ii) motivation to ask a family member to be a living donor, (iii) confidence in initiating a conversation about LDKT, (iv) intention to discuss LDKT with family members, and (v) comfort in initiating conversation about LDKT.

Other Covariates: Patient Factors

We will collect demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic variables from the baseline questionnaire, such as self-reported gender, age, race, marital status, education level, income, primary health insurance, and self-rated health. Research assistants will also track whether patients had a family member or friend with them at the evaluation appointment.

Data Management and Standardization

Before participant enrollment at each site, all research assistants will be trained in study procedures using a standard data collection protocol by the co-principal investigators and program manager. All data will be analyzed by a data analyst at Emory University with the oversight of the co-principal investigators, who will be blinded to study allocation. The de-identified SurveyMonkey data collected from the baseline and follow-up questionnaires will be merged and managed by a data analyst at Emory University. Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) will be used to prepare and merge study data.

Statistical Analyses for the Outcome Evaluation of the Intervention

Descriptive Analyses

All analyses will be conducted using an intention-to-treat approach whereby patients remain assigned to the study arm they were randomized to regardless of whether they receive the intervention. Descriptive analyses of all patient-level characteristics at time of evaluation will be compared across study groups to evaluate for differences. Student t tests and Pearson χ2 tests, or their nonparametric equivalents, will be conducted for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Continuous variables also will be examined for normality, and Cronbach’s alpha will be explored for the relevant scales. We note that detected differences may be site-specific and will explore site stratifications. Multivariable modeling techniques will be used, if necessary, to correct for lack of balance in demographic or clinical characteristics between groups.

Living Donor Inquiries: Primary Outcome

For the primary outcome, we will use generalized linear mixed models, specifying the logit link function for the binary outcomes (i.e., at least 1 living donor inquiry over a 12-month period). Study group will be the independent variable of interest, modeled as a fixed effect, with the control group specified as the reference group. We also will include fixed effects for any potential confounding covariates noted in bivariable analysis. A random intercept will be considered to increase generalizability of the results. To control for potential contamination bias over the course of the study, we will consider controlling for time of study entry.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Our secondary analyses draw from the IMB Model of individual-level behavior change, whereby we will measure patient knowledge of LDKT, motivation to share information about LDKT with friends/family, and self-efficacy for the behavioral skills to share information about LDKT. We will use a similar modeling technique as described in the preceding paragraph except that change in each of the 3 dependent variables will be the continuous (vs. binary) outcomes. We will conduct planned exploratory analyses whereby we assess change in behavioral intentions and comfort in initiating conversations about LDKT as outcomes.

Sample Size and Power

Sample size calculations will be based on our primary aim to increase living donor inquiries. In the 4 transplant center study sites in 2017, there were a total of 4537 patients with ESRD evaluated for transplantation, and most of the evaluated patients (66.5%) were AA. We anticipate approximately 25% of patients evaluated will not be eligible for transplantation and thus will not have the opportunity to have an LDKT, and these patients will not be considered in the main outcome analyses. Thus, we will have a pool of more than 2000 potential study participants over the 4 study sites over 1 year, which will ensure that we meet our estimated sample size of n = 800 AA patients with ESRD (1:1 randomization).

Based on preliminary data showing that the proportion of AAs with ≥ 1 living donor inquiry is approximately 15% at baseline, we have 80% power to detect a 10% difference between the intervention and control groups, accounting for potential correlation of patients within study sites (correlation on the same subject of 0.5), with α = 0.05. We expect little attrition in this trial, because follow-up data on the number of living donor inquiries will be abstracted from electronic medical records. Based on our prior trial,44 we expect >90% participation.

Process Evaluation of the Intervention

We will conduct a process evaluation of our proposed intervention to understand how the Living ACTS intervention was implemented, and to provide additional insights of our outcome evaluation findings. Using key process evaluation constructs,45 we will incorporate process evaluation measures throughout the entire intervention implementation process. Research assistants responsible for primary data collection activities will maintain study implementation records, and complete ratings of study context, including aspects of the transplant center environment that may influence uptake of the intervention (i.e., the patient was called into his or her evaluation appointment and unable to complete the trial). Research assistants also will remain in the room with study participants as they complete the study activities and will be capturing individual-level data on the amount of time spent on the intervention Web site and which intervention videos were watched. Google Analytics46 will provide a range of group-level measures pertaining to Web site usage (i.e., average time spent on each page, number of starts/stops of the video, and use of the social media functions), and will provide a comprehensive assessment of dose received for intervention participants. Last, we will assess recruitment through study eligibility screeners (proportion of individuals recruited who were actually eligible) and participant reporting (asking participants how they were recruited into the study).

Discussion

Previous research documents the success of the Living ACTS intervention at improving knowledge about living donor transplantation among AA patients with ESRD. However, to change behavior, multilevel interventions are necessary to address health inequities that stem from complex challenges that are deeply rooted in the US health care system in general and the transplantation system more specifically. Furthermore, given the changes in the use of technology over the past decade, whereby there is a larger proportion of the population using Web-based platforms to access videos rather than DVDs,44 there is a need to adapt the previous Living ACTS intervention for a Web-based environment, as it confers greater convenience than a DVD. In an effort to reduce barriers to living donor transplantation, a recent national consensus conference on living donor transplantation recommended collaborations between transplant centers, community organizations, dialysis facilities, and others.36 Technology was recommended as an educational tool for patients and their support systems,36 which has also been shown to be an effective tool in several other Web-based kidney disease interventions.37, 38, 39, 40 Our proposed study follows these recommendations; it builds on our existing work whereby we are implementing education within an electronic referral and communication system (T-REX) to enhance communication between dialysis facilities and transplant centers. In addition, drawing from the findings of this conference on the importance of systems-level interventions to reduce barriers to living donor transplantation, this study is uniquely poised to answer the question of whether adding an individual-level theory-based intervention is necessary to increase access to LDKT among AA patients with ESRD above and beyond what the systems-level intervention is able to accomplish alone.

This approach differs from previous interventions that have been developed with the aim of improving access to LDKT. First, although there are several educational tools and decision aids to help patients learn about LDKT, few are culturally sensitive and theoretically driven.47 For example, the Live Donor Champion is a program that seeks to train a family, friend, or community advocate for a potential kidney transplant recipient to help spread the word about kidney donation that may help improve the comfort in initiating conversations about living donor transplantation. The Providing Resources to Enhance African American Patients’ Readiness to Make Decisions about Kidney Disease (PREPARED) is theoretically driven and was designed to address the risks and benefits of treatment options for kidney disease, including peritoneal dialysis, in-center hemodialysis, home dialysis, transplant, and conservative management.48 However, this individual-level intervention did not result in an improvement in patients’ actions to pursue LDKT, and did not address barriers inherent to the larger health system.49 The combination of the systems-level T-REX intervention that encourages communication between dialysis facilities and transplant centers and the individual-level culturally sensitive education intervention that Living ACTS provides is expected to improve access to living donor transplantation among AA patients with ESRD by affecting barriers that exist at multiple levels of the social ecology.

This study suffers from limitations as does any other. Those described as follows were carefully considered to be tolerable given the alternatives. First, this study uses a convenience sample of AA patients with ESRD who are undergoing evaluation for transplantation at 1 of the 4 collaborating transplant centers. Although all eligible patients will be recruited for participation, we acknowledge that those who agree to be in the study may be different in some ways from those who decline participation. Second, our study population does not include patients with ESRD who are yet to be referred for kidney transplantation or to start the evaluation at a transplant center. We acknowledge that the demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic characteristics of patients with ESRD starting the evaluation at a transplant center may differ from dialysis patients who have yet to initiate the kidney transplant process. We will be cognizant not to generalize the findings from this study to all patients with ESRD. Third, the design does not allow us to collect individual-level data from patients beyond the initial interaction. This prohibits us from being able to assess long-term changes in the IMB constructs. Moreover, the process evaluation is unable to measure Web site usage after patients leave the clinic. Given the challenges of tracking Web site usage over time at the individual level as well as of tracking participants to collect valid and reliable follow-up data, the decision was made to make this a single point of contact study. The primary outcome (living donor inquiries) will be captured through medical records abstraction and requires no patient contact.

In addition, there will be challenges with collecting data in the context of a busy clinic appointment process. It is important that this study not interrupt the delivery of clinical care at the same time the study protocols are adhered to with integrity. Given this challenge, we will make concessions for patients to participate in the study on the first day of their evaluation, before, in-between appointments, or at the end of the day, although this can affect what information they receive about living donor transplantation from other health care professionals throughout the evaluation process. Indeed, aside from the timing of exposure to other living donor transplantation–related information, there are other nuances of data collection across and within the 4 sites that cannot be controlled (e.g., presence of family/friends during intervention, the specific information included in standard patient education materials). Nevertheless, the existence of a control group is expected to silence the effect of these potential threats to internal validity.

In conclusion, this study sought to describe the process of testing an intervention that seeks to address persistent and profound racial disparities in access to LDKT. This study is unique in that the intervention takes a multilevel approach to a complex problem, yet there are few studies in the literature that fully describe a rigorous test of such an intervention. Such a description facilitates replication and a critical assessment of the validity of the findings, once they are determined. If effective, the Living ACTS/T-REX multilevel intervention could help improve access to living donor transplantation among AAs, who are underrepresented in the receipt of LDKT. There are aspects of this process that this intervention does not address, such as the medical suitability of friends/family, the size of the pool of eligible friends/family members, and patient adherence to medical instructions needed to be approved for transplantation. But this multilevel intervention is expected to address well-known barriers to living donor transplantation among AA patients and in doing so lessen the well-established inequities in access to renal transplantation. It is expected that with evidence of efficacy, this intervention could be replicated in other settings around the United States.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by funding from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK114891). The authors also acknowledge Rich Mutell (Apex Health Innovations) for the creation of the T-REX application.

References

- 1.Choi A.I., Rodriguez R., Bacchetti P. White/Black racial differences in risk of end-stage renal disease and death. Am J Med. 2009;122:672–678. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.USRDS . National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2014. United States Renal Data System, 2014 Annual Data Report: An overview of the epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patzer R., Perryman J., Schrager J. The role of race and poverty on steps to kidney transplantation in the southeastern United States. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:358–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gore J., Danovitch G., Litwin M. Disparities in the utilization of live donor renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1124–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arriola K.J., Robinson D.H., Boulware L.E. Narrowing the gap between supply and demand of organs for transplantation. In: Braithwaite R.L., Taylor S.E., Treadwell H.M., editors. Health Issues in the Black Community. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2009. pp. 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waterman A.D., Peipert J.D., Hyland S.S. Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:995–1002. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08880812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garg P.P., Frick K.D., Diener-West M., Powe N.R. Effect of the ownership of dialysis facilities on patients' survival and referral for transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1653–1660. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911253412205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weng F.L., Joffe M.M., Feldman H.I., Mange K.C. Rates of completion of the medical evaluation for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:734–745. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patzer R.E., Amaral S., Wasse H. Neighborhood poverty and racial disparities in kidney transplant waitlisting. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1333–1340. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashby V.B., Kalbfleisch J.D., Wolfe R.A. Geographic variability in access to primary kidney transplantation in the United States, 1996–2005. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1412–1423. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stolzmann K., Bautista L., Gangnon R. Trends in kidney transplantation rates and disparities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:923–932. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waterman A., Rodrigue J., Purnell T. Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in live donor kidney transplantation: priorities for research and intervention. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arriola K., Perryman J., Doldren M. Understanding the role of clergy in African American organ and tissue donation decision-making. Ethn Health. 2007;12:465–482. doi: 10.1080/13557850701616896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson N.J., McClintock H.O. Centers for Disease Control and Prvention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Atlanta, GA: 1998. Demonstrating Your Program's Worth: A Primer on Evaluation for Programs to Prevent Unintentional Injury. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krueger R.A. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Department of Health and Human Services . US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2006. Research-Based Web Design & Usability Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klarenbach S., Gill J., Knoll G. Economic consequences incurred by living kidney donors: a Canadian multi-center prospective study. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:916–922. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke K.S., Klarenbach S., Vlaicu S. The direct and indirect economic costs incurred by living kidney donors—a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1952–1960. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulware L., Ratner L.E., Sosa J.A. The general public's concerns about clinical risk in live kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:186–193. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.020211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang R., Thiessen-Philbrook H., Klarenbach S. Insurability of living organ donors: a systematic review. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1542–1551. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ommen E., Gill J. The system of health insurance for living donors is a disincentive for live donation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:747–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callender C., Miles P., Hall M., Gordon S. Blacks and whites and kidney transplantation: a disparity! But why and why won't it go away? Transplant Rev. 2002;16:163–176. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callender C., Miles P. Obstacles to organ donation in ethnic minorities. Pediatr Transplant. 2001;5:383–385. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.2001.t01-2-00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rumsey S., Hurford D., Cole A. Influence of knowledge and religiousness on attitudes toward organ donation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:2845–2850. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gamble V. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Washington H. Harlem Moon; New York: 2006. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans From Colonial Times to the Present. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lunsford S., Simpson K., Chavin K. Racial disparities in living kidney donation: is there a lack of willing donors or an excess of medically unsuitable candidates? Transplantation. 2006;82:876–881. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000232693.69773.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeves-Daniel A., Adams P., Daniel K. Impact of race and gender on live kidney donation. Clin Transplant. 2009;23:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2008.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shilling L., Norman M., Chavin K. Healthcare professionals' perceptions of the barriers to living donor kidney transplantation among African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:834–840. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghahramani N. Perceptions of patient suitability for kidney transplantation: a qualitative study comparing rural and urban nephrologists. Abstract presented at: American Transplant Congress. April 30–May 4, 2011; Philadelphia, PA.

- 31.Ayanian J.Z., Cleary P.D., Keogh J.H. Physicians’ beliefs about racial differences in referral for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:350–357. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanson C.S., Chadban S.J., Chapman J.R. Nephrologists' perspectives on recipient eligibility and access to living kidney donor transplantation. Transplantation. 2016;100:943–953. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balhara K, Kucirka L, Jaar B, Segev D. Race, age, and insurance status are associated with duration of kidney transplant counseling provided by non-transplant nephrologists. Abstract presented at: American Transplant Congress. April 30–May 4, 2011; Philadelphia, PA.

- 34.Waterman A., Goalby C., Hyland S. Transplant education practices and attitudes in dialysis centers: dialysis leadership weighs in. J Nephrol Ther. 2012;2012:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patzer R.E., Gander J., Sauls L. The RaDIANT community study protocol: community-based participatory research for reducing disparities in access to kidney transplantation. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waterman A.D., Robbins M.L., Peipert J.D. Educating prospective kidney transplant recipients and living donors and living donation: practical and theoretical recommendation for increasing living donation rates. Curr Transplant Rep. 2016;3(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s40472-016-0090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Godin S, Truschel J, Singh V, eds. Assessing quality assurance of self-help sites on the Internet. In: Godin S, ed. Technology Applications in Prevention. New York, NY: Routledge; 2005.

- 38.Arriola K.R.J., Robinson D.H.Z., Perryman J.P. Testing the efficacy of project ACTS II: a revised donation education intervention for African American adults. Ethnicity and Disease. 2013;23:230–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diamantidis C.J., Fink W., Yang S. Directed use of the internet for health information by patients with chronic kidney disease: prospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e251. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gordon E., Feinglass J., Carney P. A culturally targeted website for Hispanics/Latinos about living kidney doantion and transplantation: a randomized controlled trial of increased knowledge. Transplantation. 2016;100:1149–1160. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fisher J.D., Fisher W.A. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model. In: DiClemente R.J., Crosby R.A., Kegler M.C., editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research: Strategies for Improving Public Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2002. pp. 40–70. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arriola K.R.J., Robinson D.H.Z., Thompson N.J., Perryman J.P. Project ACTS: an intervention to increase organ and tissue donation intentions among African Americans. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37:264–274. doi: 10.1177/1090198109341725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Resnicow K., Baranowski T., Ahluwalia J.S., Braithwaite R.L. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethnicity and Disease. 1999;9:10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arriola K.J., Powell C.L., Thompson N.J. Living donor transplant education for African American patients with end-stage renal disease. Prog Transplant. 2014;24:362–370. doi: 10.7182/pit2014830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linnan L., Steckler A. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. In: Steckler A., Linnan L., editors. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2002. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Google Analytics. 2012. http://www.google.com/intl/en/analytics/ Available at:

- 47.Garonzik-Wang J.M., Berger J.C., Ros R.L. Live donor champion: finding live kidney donors by separating the advocate from the patient. Transplantation. 2012;93:1147–1150. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31824e75a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ephraim P.L., Powe N.R., Rabb H. The providing resources to enhance African American patients' readiness to make decisions about kidney disease (PREPARED) study: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boulware L.E., Ephraim P.L., Ameling J. Effectiveness of informational decision aids and a live donor financial assistance program on pursuit of live kidney transplants in African American hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:107. doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-0901-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]