Abstract

Lysine methylation of cellular proteins is catalyzed by dozens of lysine methyltransferases (KMTs), occurs in thousands of different histone and nonhistone proteins, and regulates diverse biological processes. Dysregulation of KMT-mediated lysine methylations underlies many human diseases. A key unanswered question is how proteins, nonhistone proteins in particular, are specifically methylated by each KMT. Here, using several biochemical approaches, including analytical gel filtration chromatography, isothermal titration calorimetry, and in vitro methylation assays, we discovered that SET domain–containing 7 histone lysine methyltransferase (SETD7), a KMT capable of methylating both histone and nonhistone proteins, uses its N-terminal membrane occupation and recognition nexus (MORN) repeats to dock its substrates and subsequently juxtapose their Lys methylation motif for efficient and specific methylation by the catalytic SET domain. Such docking site–mediated methylation mechanism rationalizes binding and methylation of previously known substrates and predicts new SETD7 substrates. Our findings further suggest that other KMTs may also use docking-mediated substrate recognition mechanisms to achieve their catalytic specificity and efficiency.

Keywords: histone methylation, protein methylation, epigenetics, docking, enzyme catalysis, SET domain-containing 7 histone methyltransferase (SETD7), MORN repeats, lysine methylation, docking interaction, substrate specificity, gene regulation, protein-protein interaction, posttranslational modification, charge-charge interaction

Introduction

Methylation of lysine residues was first discovered exactly 60 years ago in bacterial flagellin by Ambler and Rees (1). For the following 40 years or so, lysine methylation was discovered to occur in abundant proteins, including mammalian histones (2) and universal Ca2+-signaling regulator calmodulin (3, 4), and established as a form of enzyme-catalyzed and reversible protein post-translational modification (5, 6). However, the biological relevance of lysine methylation has remained largely unclear, although specific Lys-115 trimethylation of calmodulin has been implicated in regulating calmodulin target enzyme NAD kinase (6, 7). The discoveries of lysine methyltransferase (KMT)3-catalyzed histone lysine methylation in regulating gene transcriptions 20 years ago have transformed protein lysine methylation research into a booming field (6, 8, 9). The human genome encodes more than 100 KMTs (10, 11), and these enzymes catalyze methylations on numerous proteins other than histones (6, 12–15). In fact, based on data curated in the PhosphoSite Plus database (http://www.phosphosite.org),4 more than 5,000 lysine methylation sites in ∼2,760 human proteins have been identified mainly by proteomics-based methods (16).

One of the key challenges facing the lysine methylation research field is to understand which of these identified methylations are truly functional and what the functions of the methylations are. Directly relevant to the above question is how KMTs can specifically recognize their protein substrates. Numerous biochemical and structural studies in the past 2 decades have uncovered protein substrate binding by various catalytic domains of KMTs (14, 17, 18). The converging picture is that the catalytic domain of KMTs recognizes 2–3 residues flanking both N and C termini of methylating Lys residue (14). If each KMT indeed only recognizes such short linear substrate recognition motifs, many KMTs would share overlapping substrates, and methylation reactions would be highly promiscuous, a deduction that appears to be contradictory to numerous functional studies of lysine methylations both on histone and nonhistone proteins (19). Furthermore, taking several better-studied KMTs, such as SETD7 (also known as SET7/9 and KMT7), G9a (also known as EHMT2), and SMYD2, for example, each of these enzymes may recognize ∼20,000 methylation sites in the human proteome if simply matching with each of their optimal substrate recognition sequence. Thus, it is safe to hypothesize that KMTs contain another layer(s) of substrate recognition mechanism in addition to their catalytic domains. Identification of such KMT substrate specificity mechanisms will not only be vital for understanding functional implications of each lysine methylation but will also be crucial for selecting KMTs as drug targets for disease therapies.

SETD7 is the first KMT that was identified to be able to methylate Lys residues both in histones and in nonhistone proteins (20–22). More than 40 different protein substrates, including p53, TAF10, DNMT1, estrogen receptor α E2F1, and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, have been identified for SETD7 (22–28), but how SETD7 specifically recognizes these substrates is poorly understood. For example, a number of reported SETD7 substrates, such as pRb, SIRT1, YAP, and β-catenin, do not contain the optimal (R/K)(S/T/A)K(D/N/S/T/Q) motif (29–32).

In this study, we discover that the N-terminal MORN repeats of SETD7, being highly negatively charged, can bind to positively charged proteins, including a panel of transcription factors, through charge–charge interaction. Importantly, we found that the MORN repeats serve as a specific substrate docking site for SETD7, thereby enhancing both the efficiency and specificity of SETD7-mediated Lys methylations. Mechanistically, binding of positively charged sequences/domains both from histone 3 and from nonhistone proteins physically position their Lys methylation (R/K)(S/T/A)K(D/N/S/T/Q) motif for optimal methylation by the catalytic domain. Given that essentially every KMT contains additional protein-binding domain(s) outside its catalytic core, substrate docking–mediated Lys methylations may be a common mechanism for other KMTs (or even other protein methyltransferases, such as Arg methyltransferases).

Results

SETD7 interacts with the DNA-binding domain of PDX1 through charge–charge interaction

The crystal structures of SETD7, both in its apo- and substrate-bound forms, showed that the enzyme contains a β-strand repeat domain (now known as a MORN repeat) physically coupled to the catalytic SET domain (17, 35, 36) (Fig. 1A). The role of MORN repeats in SETD7 is not known, and they have been proposed to stabilize the catalytic domain of the enzyme. Alterations of the MORN are known to perturb catalytic function of SETD7 (20, 35). MORN repeats also exist in other proteins, including MORN1–5 and junctophilin1–4, among others, but the role of MORN repeats has remained unknown. We recently discovered that the MORN repeats of MORN4 can specifically bind to a segment in the tail cargo–binding domain of unconventional Myo3a (37), providing a direct clue suggesting that MORN repeats can be a protein–protein interaction module. We therefore hypothesized that the MORN repeats of SETD7 may also function as a protein–protein interaction module, possibly serving as a substrate docking site of the enzyme.

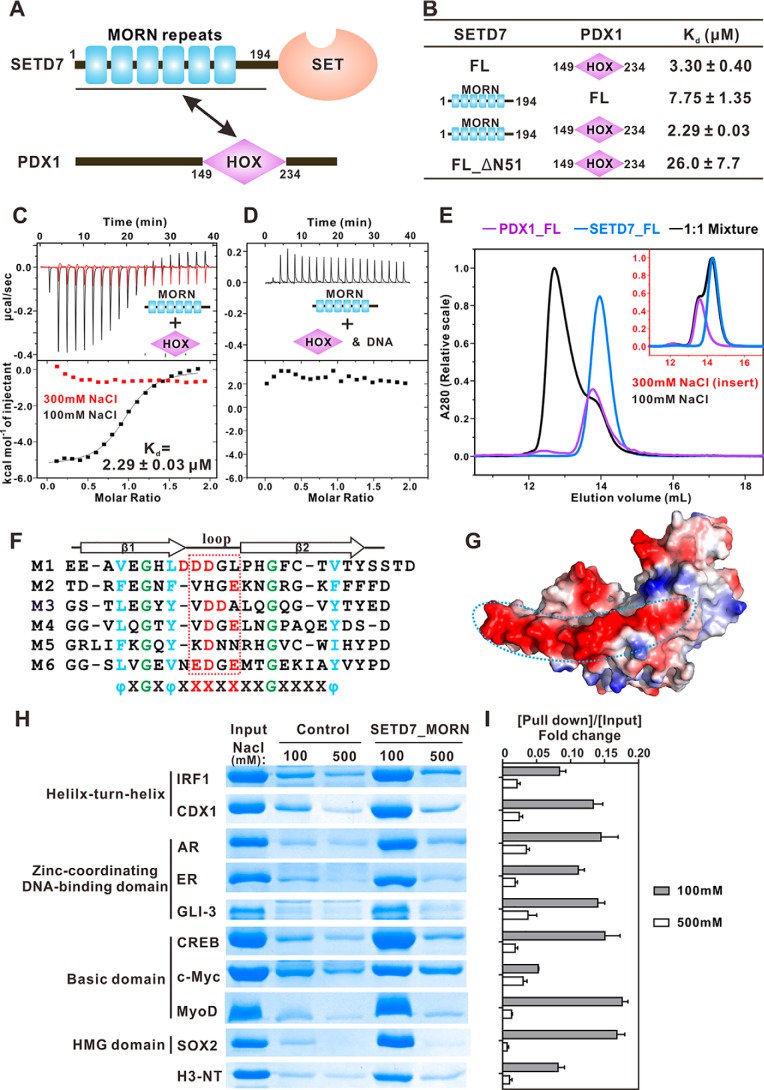

Figure 1.

SETD7_MORN binds to PDX1_HOX and other transcription factors through charge–charge interactions. A, schematic diagram showing the domain organizations of SETD7 and PDX1. B, table summarizing the ITC-derived binding affinities of SETD7 proteins and PDX1 proteins. C, ITC results comparing binding affinities between SETD7_MORN and PDX1_HOX in the presence of 100 mm NaCl (black) or 300 mm NaCl (red). D, ITC result showing that specific PDX1-binding DNA can disrupt the interaction between SETD7_MORN and PDX1_HOX. E, analytical gel filtration chromatography showing the binding profiles of SETD7 and PDX1 in low-salt buffer and in high-salt buffer (inset). F, sequence alignment of the six MORN repeats of SETD7 showing that the loop regions of these MORN repeats are enriched with negatively charged residues. In the alignment, totally conserved glycine residues are labeled in green, conserved hydrophobic residues are in blue, and negatively charged residues in the loop are in red. G, surface electrostatic potential of SETD7 52–344 (Protein Data Bank code 1H3I) showing that the negatively charged residues in the loop region are distributed in one side of MORN repeats, forming a negatively charged and concave surface. H, GST pulldown assays showing the interactions between GST-SETD7_MORN and an array of DNA-binding domains from different transcription factors. AR, androgen receptor; ER, estrogen receptor. I, quantification of GST pulldown results from three independent experiments. The intensity ratio of [pulldown]/[input] was calculated to indicate the interaction strength. Error bars, S.D. of triplicate experiments.

To test the above hypothesis, we dissected the interaction of SETD7 with one of its previously reported binders PDX1 transcription factor (38). We verified this interaction using purified recombinant full-length proteins of SETD7 and PDX1 through fast performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) (Fig. 1E). Further detailed mapping experiments via isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)-based binding assays revealed that the N-terminal MORN repeat (SETD7_MORN, amino acids (aa) 1–194) of SETD7 binds to the DNA-binding domain of PDX1 (PDX1_HOX, aa 149–234) with a dissociation constant (Kd) of ∼2.3 μm, a value comparable with that of SETD7_MORN/PDX1_FL interaction or SETD7_FL/PDX1_HOX interaction (Fig. 1 (C and D) and Fig. S1 (A, B, and E)). Interestingly, deletion of the N-terminal 51 residues dramatically diminished the binding (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1C; this 51-residue sequence was not defined in the crystal structure of SETD7 (17, 35)), indicating that the intact MORN repeats are required for binding to PDX1.

The PDX1_HOX is known to bind to specific DNA sequence with a high affinity (39) (Fig. S1D). We then asked whether SETD7_MORN and DNA compete for binding to PDX1 using ITC- and FPLC-based competition experiments. ITC data showed that SETD7_MORN displayed no detectable binding to PDX1_HOX premixed with a stoichiometric amount of the specific DNA duplex (Fig. 1D). Consistently, the PDX1_HOX-binding DNA duplex specifically disrupted the formation of the SETD7_MORN/PDX1_HOX complex on FPLC-based analysis (Fig. S2A). The above competitive bindings suggested that SETD7 and DNA bind to the overlapping positively charged region of PDX1 and that the interaction between SETD7 and PDX1 is largely mediated by charge–charge interactions. Indeed, both FPLC- and ITC-based assays showed that the interaction between SETD7 and PDX1 was disrupted by raising NaCl concentration to 300 mm in the assay buffer (Fig. 1, C and E).

Negatively charged SETD7_MORN binds to the DNA-binding domains of many transcription factors

The sequence alignment of the six SETD7 MORN repeats reveals that each repeat consists of two relatively conserved β-strands and a loop in between (Fig. 1F). Interestingly, the loop regions of each MORN repeat are enriched with acidic amino acids, which are distributed along one side of MORN repeats, forming a highly negatively charged and concave surface (Fig. 1, F and G). This highly negatively charged surface complements the positively charged surface of PDX1 HOX domain (39). The corresponding concave surface in the MORN4 MORN repeats binds to Myo3a with a Kd of ∼2.4 nm (37). Based on the above analysis, we speculated that other highly positively charged proteins, including many transcription factors, may be potential binders of SETD7.

To test this hypothesis, we selected nine transcription factors from four different classes (40) and tested their bindings to SETD7 using a GST pulldown assay (Fig. 1H). DNA-binding domains of these transcription factors were purified as Trx-fused proteins. Strikingly, every one of these transcription factors could be pulled down by GST-SETD7_MORN in low-salt concentration assay buffer (100 mm NaCl; Fig. 1, H and I). Again, all of these interactions were dramatically weakened or even disrupted by raising NaCl concentration to 500 mm in the assay buffer (Fig. 1, H and I). We have verified the direct binding of some of these transcription factors to SETD7 by FPLC by mixing each of the purified DNA-binding domains with SETD7_FL (Fig. S3). We have also shown that a specific MyoD-binding DNA duplex (41) specifically disrupted the interaction between SETD7 and MyoD (42) (Fig. S2B). The N-terminal tail of histone H3 was reported to be monomethylated at Lys-4 by SETD7 and is highly positively charged. As expected, the N-terminal tail of histone H3 was also pulled down by GST-SETD7_MORN (Fig. 1, H and I). Collectively, these above biochemical data demonstrated that SETD7_MORN can function as a protein recognition module by binding to highly positively charged proteins such as histones and DNA-binding domain–containing proteins through charge–charge interaction.

SETD7_MORN is required for histone H3 N-terminal tail interaction and efficient methylation

For histone H3, we hypothesized that the highly positively charged sequence C-terminal to the Lys-4 methylation site can bind to the SETD7_MORN and serve to dock the histone protein to the full-length SETD7 for specific and efficient Lys-4 methylation (Fig. 2A). To test this hypothesis, we took advantage of the fact that the binding of the methylation site sequence of substrates to SETD7 requires the presence of its cofactor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) or the product S-adenosyl homocysteine (SAH) (43) (also see Fig. S4 (A and B)). We could study the binding of various substrate proteins with SETD7, either with or without the presence of SAH, to determine the possible existence of SETD7-docking sequence and to isolate the contribution of such docking sequence to the enzyme binding and catalysis (Fig. 2B).

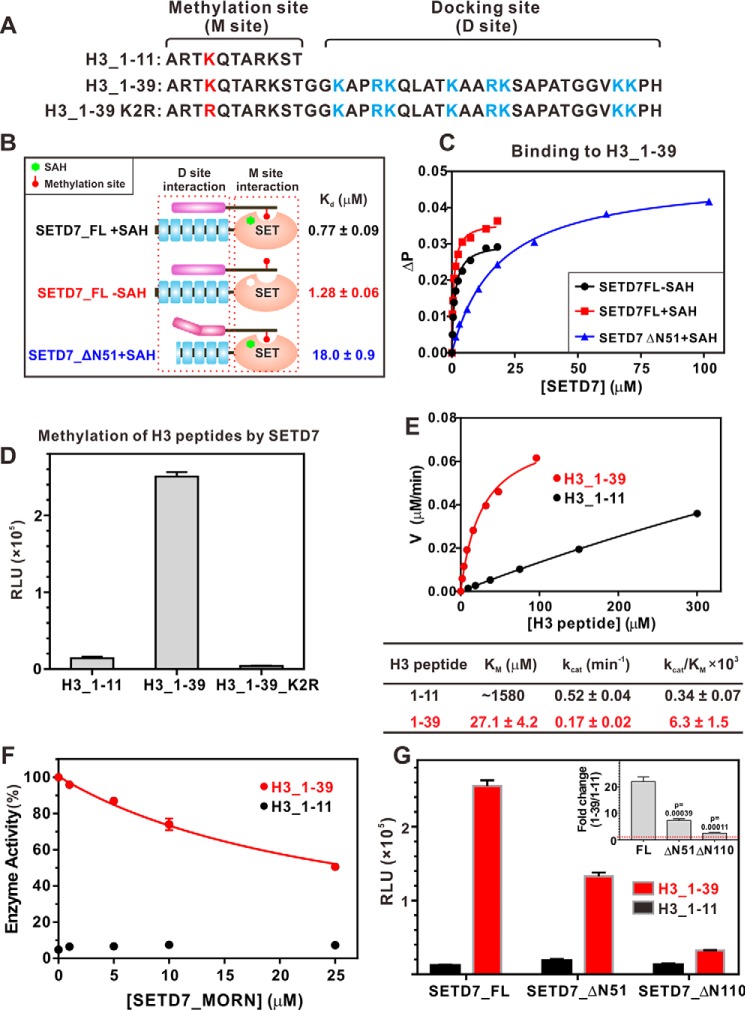

Figure 2.

SETD7_MORN is required for histone H3 N-terminal tail interaction and efficient methylation. A, sequence analysis showing the methylation site and docking site of the histone H3 N-terminal region. B, SETD7_MORN is required for the histone H3 N-terminal region interaction. The schematic diagram summarizes the binding affinities of H3_1–39 with various forms of SETD7. C, fluorescence polarization–based measurements of the bindings of H3_1–39 with various forms of SETD7. D, in vitro assay comparing SETD7-mediated methylations of various H3 N-terminal peptides. The concentration of SETD7 used in the assay was 0.5 μm. E, Michaelis–Menten plots comparing the methylation kinetics of H3_1–11 and H3_1–39 by SETD7. F, in vitro methylation assay showing that the addition of the SETD7_MORN specifically inhibited SETD7-mediated methylation of H3_1–39, but not of H3_1–11. G, progressive truncations of the MORN repeats proportionally and specifically weakened methylation of H3_1–39 but had no effect on H3_1–11. The inset shows the methylation -fold changes of [H3_1–39]/[H3_1–11] by different SETD7 MORN repeat truncations. For D, F, and G, error bars show the S.D. of three different batches of experiments.

The ITC assay showed that the histone H3 methylation site peptide (H3_1–11; Fig. 2A) binds to SETD7_FL with a very weak affinity (Kd ∼276 μm) in the presence of SAH, and the binding was undetectable in the absence of SAH (Fig. S4B). Using a fluorescence-based binding assay, we determined that an elongated H3 peptide (H3_1–39) binds to SETD7_FL with a Kd of ∼0.8 μm and 1.3 μm in the presence and absence of SAH, respectively (Fig. 2 (B and C) and Fig. S4C). The above results indicated that the residues C-terminal to the methylation sites serve as a specific and strong binding element for histone H3 to bind to SETD7_MORN, and the methylation site of H3 (i.e. H3_1–11) plays a minor role in binding to SETD7. Therefore, we defined the H3_13–39 segment of histone H3 as the SETD7-docking sequence chiefly responsible for the enzyme binding (Fig. 2A). This finding is consistent with the observation that mutation of basic residues far from H3K4 in primary sequence decreases the catalytic activity of the enzyme (35). Additionally, removal of the N-terminal 51 residues of SETD7 dramatically weakened its binding to H3_1–39 (Fig. 2 (B and C), blue curve), again demonstrating that the intact MORN repeats are required for SETD7 to bind to histone H3.

In vitro methylation assays were then used to investigate the role of the docking interaction in SETD7-mediated substrate methylations. Methylation of the H3_1–11 peptide was very inefficient (Fig. 2D). In contrast, SETD7 catalyzed H3_1–39 methylation with much higher efficiency (∼20-fold higher than that of H3_1–11; Fig. 2D). The increased methylation on H3_1–39 was not caused by methylation of additional lysine residues, as substitution of Lys-4 with Arg totally abolished H3_1–39 methylation by SETD7 (Fig. 2D). This finding further indicates that the docking event increased both the efficiency and specificity of the H3K4 methylation by SETD7. To further determine the steady-state kinetic parameters, we performed methylation assays at different substrate concentrations (Fig. 2E). Steady-state kinetic studies showed that SETD7 catalyzed the H3_1–39 peptide with a much lower Km value than did the H3_1–11 peptide (Fig. 2E; 27.1 μm for H3_1–39, 1580 μm for H3_1–11). The kcat value difference for the two H3 peptides was small, and the kcat value for the H3_1–11 peptide may have relatively large errors due to the very sluggish reactions (Fig. 2E). The overall specificity, as indicated by kcat/Km of SETD7 toward H3_1–39, was ∼18.5-fold higher than that toward H3_1–11 (Fig. 2E).

We further showed that the SETD7_MORN inhibited SETD7-mediated methylation of H3_1–39, but not to H3_1–11, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2F). Deletion of the N-terminal 51 or 110 residues of SEDT7, corresponding to the first two or four MORN repeats, significantly decreased methylation of H3_1–39 by the mutant enzymes (Fig. 2G, red bars). Notably, these two N-terminal truncations did not affect the catalytic activity of SETD7 toward H3_1–11 (Fig. 2G, black bars), suggesting that deletion of N-terminal MORN repeats did not cause an overall conformational change of SET domain of the enzyme. Taken together, the above biochemical results demonstrated that the MORN repeats of SETD7 functions as the docking site for histone H3 and thereby increase the methylation efficiency and specificity of H3K4 by the enzyme.

MORN repeat–mediated docking enhances nonhistone substrate methylation

TAF10 is one of the better known nonhistone substrates for SETD7 (17, 23), and it does not contain any sequence capable of binding to SETD7_MORN (data not shown). We therefore used TAF10 as a model to investigate how a docking sequence might influence Lys methylation of nonhistone proteins. We constructed a chimeric protein in which the TAF10 methylation peptide was fused to the N terminus of PDX1_HOX, with a linker length of 16 residues (5 residues from TAF10 and 11 residues from PDX1) (Fig. 3A). TAF10 methylation site peptide (TAF10_P; Fig. 3A) binds to SETD7 with a quite strong affinity (Kd ∼9.6 μm; Fig. 3B), as the TAF10_P has the optimal binding sequence for the catalytic domain of SETD7 (14, 17). The PDX1_HOX binds to SETD7_FL or SETD7_MORN with a Kd of ∼2–3 μm (Fig. 1B). The TAF10_P/PDX1_HOX chimera has an enhanced Kd of ∼0.35 μm (Fig. 3, C and D), showing that TAF10_P and PDX1_HOX in the chimera cooperatively bind to SETD7. Next, we measured the impact of the docking sequence on the methylation of TAF10_P by SETD7 using the in vitro methylation assay. Due to its relatively strong binding, the methylation of TAF10_P by SETD7 is much more efficient than that of the H3_1–11 peptide (Fig. 3E versus Fig. 2D). The methylation efficiency of the TAF10_P/PDX1_HOX chimera was significantly higher than that of the TAF10_P alone. We confirmed that the improvement of the chimera methylation was not due to a potential additional methylation site(s) introduced by PDX1_HOX, as no methylation could be detected for a chimera mutant with its methyl acceptor Lys substituted by Arg or for PDX1_HOX only as a substrate (Fig. 3E). The result in Fig. 3E also indicated that SETD7-mediated methylation of the chimera is highly specific, likely due to spatial constraint of the methylation site on TAF10_P by the binding between the SETD7_MORN and PDX1_HOX.

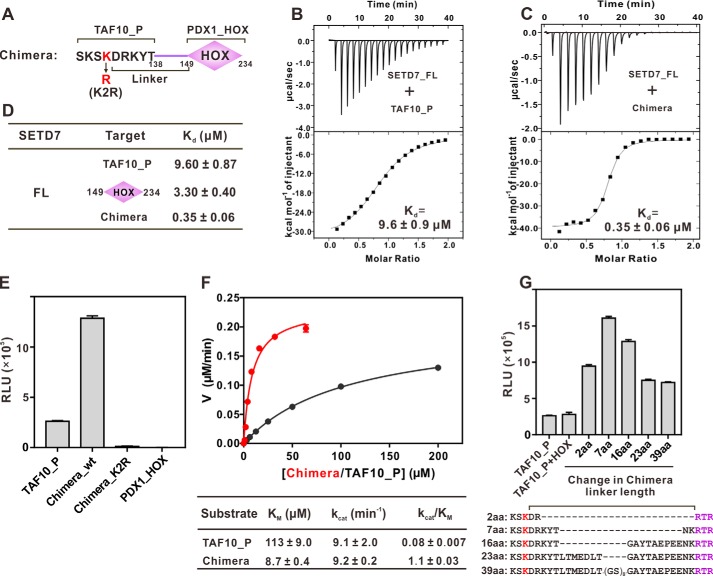

Figure 3.

Docking-induced enhancement of TAF10 methylation by SETD7. A, schematic diagram illustrating a chimera composed of TAF10 peptide (TAF10_P) fused with PDX1_HOX. The linker is defined as residues between the methylating Lys and Arg-149 of PDX1. B and C, ITC results quantifying the binding affinities of SETD7 to TAF10_P (B) and the chimera (C). D, ITC results summarizing the binding affinities of SETD7 to TAF10_P, PDX1_HOX, and chimera. E, in vitro assay of TAF10_P or chimera methylation by SETD7. The concentration of SETD7 used in the assay was 0.025 μm. F, Michaelis–Menten plots comparing the methylation kinetics of SETD7-mediated methylations of TAF10_P and the chimera. G, linker length between methylation site and docking site affects substrate methylation efficiency by SETD7. The detailed linker sequences are indicated in the bottom panel. For E and G, error bars represent the S.D. of three different batches of experiments.

Kinetic studies further showed that fusion of PDX1_HOX to TAF10_P lowered its Km value of the substrates from 113 to 8.7 μm (Fig. 3F). The fusion of the PDX1_HOX, however, did not change the kcat value of TAF10_P methylation (Fig. 3F), indicating that there is no obvious allosteric conformational coupling between the MORN repeats and the SET domain in SETD7. As a result, the fusion of the docking PDX1_HOX domain increased the overall methylation efficiency and specificity (kcat/Km) of TAF10_P by ∼14-fold.

Next, we investigated what might be the optimal distance between the docking sequence and the methylation site for SETD7-mediated methylation of the TAF10_P/PDX1_HOX chimera by varying the linker length between TAF10_P and PDX1_HOX. We found that the optimal linker length is around 7 amino acids, and lengthening or shortening of the linker reduced the methylation efficiency of the chimera (Fig. 3G). In an extreme case, the mixture of TAF10 peptide and PDX1_HOX, which is equivalent to a chimera with an infinite-length linker, displayed a similar level of methylation compared with TAF10_P alone (Fig. 3G).

MORN repeat–mediated substrate docking is a general mechanism for SETD7 to specifically methylate its substrates

Our above studies on histone H3 and the TAF10-PDX1 chimera point to a possibility that an optimal substrate for SETD7 should contain a MORN repeat–binding docking sequence and a SET domain recognition methylation site (Fig. 4A). We analyzed the currently identified substrates of SETD7 (28) and noticed that the majority of these proteins are DNA/RNA-binding proteins, each of which contains at least one positively charged DNA/RNA-binding domain (Fig. 4B and Table S1). We selected a transcription factor, IRF1, for further analysis. Consistent with our model, the DNA-binding domain of IRF1 could bind to SETD7_MORN in a salt concentration–dependent manner (Fig. 1, H and I). The methylation reaction catalyzed by SETD7 toward the methylation site peptide only was inefficient. Inclusion of the DNA-binding domain dramatically increased the methylation efficiency of IRF1 (Fig. 4, C and D). Additionally, the efficient methylation mainly occurred on Lys-125, as substitution of Lys-125 with Arg dramatically weakened IRF1 methylation by SEDT7 (Fig. 4D) (44). The above results suggested that the MORN repeat–mediated substrate docking is a general mechanism for SETD7 to specifically and efficiently methylate its substrates.

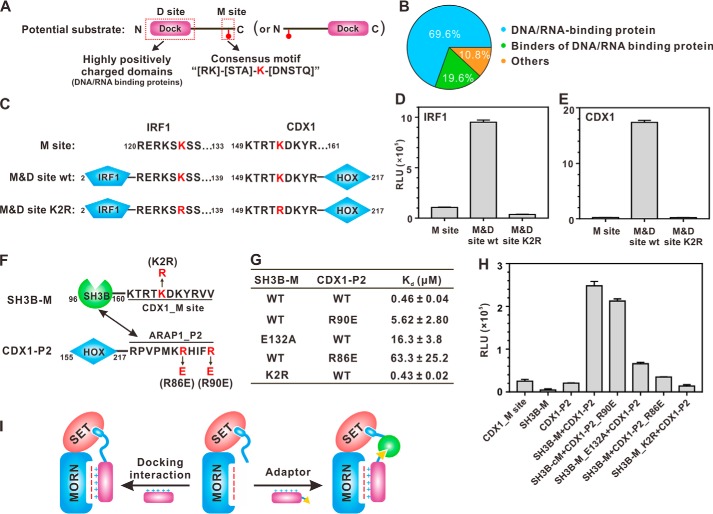

Figure 4.

Docking-mediated methylation is a general catalytic mechanism for specific substrate methylation by SETD7. A, schematic diagram showing the substrate-searching strategy. Potential substrates contain a highly positively charged DNA/RNA-binding domain capable of docking to the MORN repeats and a consensus methylation site with the sequence motif of (R/K)(S/T/A)K(D/N/S/T/Q). B, distribution of currently identified substrates of SETD7 (see Table S1 for detailed substrate information). C, schematic diagram showing the docking site + methylation site arrangements of IRX1 and CDX1, two selected examples of SETD7 substrates matching the searching criteria. D and E, in vitro analysis of specific methylation of IRF1 (D) and CDX1 (E) by SETD7. The concentration of SETD7 used in the assay was 0.5 μm. F, schematic diagram showing the design of adaptor protein binding–mediated substrate methylation by SETD7. The methylation sequence of CDX1 was fused to the C terminus of the CIN85_SH3B domain (denoted as SH3B-M, Lys methylation motif–containing protein). The SH3B-M–binding sequence from ARAP1 was fused to the C terminus of CDX1_HOX domain (denoted as CDX1-P2, adaptor). G, ITC-based measurements summarizing the binding affinities of various SH3B-M proteins to different forms of CDX1-P2. H, methylation of CDX1-P2 by SETD7 is positively correlated with its binding affinity with SH3B-M. The concentration of SETD7 used in the assay was 0.5 μm. I, cartoon illustrating docking-enhanced substrate methylation by SETD7. Without docking, a substrate can only be recognized by the SETD7 catalytic domain, and the methylation is inefficient and with low specificity (middle). A substrate can directly dock onto the SETD7_MORN (left) or use an adaptor protein to dock onto the SETD7_MORN (right) to achieve efficient methylation and high specificity. For D, E, and H, error bars represent the S.D. of three different batches of experiments.

The above SETD7 substrate recognition model prompted us to search for new substrates of the enzyme. Thousands of matches were found in the entire human proteome when searching for the SETD7 methylation site consensus motif, (R/K)(S/T/A)K(D/N/S/T/Q). Searching a transcription factor database (45) for proteins containing this motif still returned more than 200 proteins. We further restricted the linker length between docking DNA-binding domain (excluding zinc fingers, the boundaries of which are hard to define) and methylation sites to 50 amino acids or less, and this narrowed the potential targets down to 21; CDX1 is one such transcription factor. A recombinant CDX1 containing both the positively charged DNA-binding domain and methylation site was very efficiently methylated by SETD7. In contrast, very weak methylation was observed if the methylation site peptide alone was reacted with SETD7 (Fig. 4E). Again, SETD7 mainly methylated one Lys in the methylation site (Lys-154), and substitution of Lys-154 by Arg almost blocked CDX1 methylation by SETD7 (Fig. 4E).

It is noted that the methylation site of IRF1 is located C-terminal to the DNA-binding domain, and the methylation sites of CDX1, the TAF10_P/PDX1_HOX chimera, and histone H3 are all located N-terminal to their MORN repeat–binding domains (Figs. 2A, 3A, and 4C). This analysis suggests that the methylation site peptides of the SETD7 substrates can be situated either N- or C-terminal to their MORN repeat–docking domains.

An alternative possibility is that a SETD7 MORN repeat–binding protein may function as an adaptor to tether Lys methylation motif–containing proteins to be specifically and efficiently methylated by SETD7 (Fig. 4I, right). To test this model, we conducted a proof-of-concept study by dividing CDX1 into two parts (Fig. 4F). The DNA-binding HOX domain was fused to the N terminus of a proline-rich peptide from ARAP1 (denoted as CDX1-P2), and the methylation site of CDX1 was fused to the C terminus of CIN85_SH3B domain (denoted as SH3B-M). CIN85_SH3B has been shown to be able to bind to ARAP1_P2 with submicromolar affinity, and the binding can be fine-tuned by point mutations (33) (Fig. 4G). Essentially no methylation was observed when the recombinant SH3B-M protein alone was reacted with SETD7, whereas the methylation became efficient when adaptor protein CDX1-P2 was added to the reaction system (Fig. 4H). Moreover, weakening the binding between SH3B-M and CDX1-P by point mutations invariably led to decreases of methylation efficiency (Fig. 4, G and H), suggesting that the methylation efficiency was positively correlated with the binding affinity between adaptor protein and substrate protein.

Because DNA can efficiently compete with the MORN repeats for binding to the DNA-binding domains of transcription factors (Fig. 1 (D and H) and Fig. S2), we also tested whether DNA can inhibit substrate methylation in vitro. A specific DNA sequence (IRF1-DNA; Fig. S5A) that can efficiently bind to transcription factor IRF1 can dramatically inhibit IRF1 methylation by SETD7 (Fig. S5, A and B), whereas a nonspecific DNA (CDX1-DNA) can neither bind to IRF1 nor inhibit IRF1 methylation (Fig. S5, A, B, and F). Similarly, PDX1-specific and CDX1-specific DNA sequences could inhibit the TAF10_P/PDX1_HOX chimera (Fig. 3) and CDX1 (Fig. 4) methylations by SETD7, respectively (Fig. S5, A, C, D, G, and H). Notably, a specific DNA sequence can inhibit methylation of a transcription factor with a docking site, but not a peptide containing only a methylation site (Fig. S5, B and C), further demonstrating the critical role of the MORN repeat–mediated docking interaction in substrate methylation by SETD7.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that the N-terminal MORN repeats of SETD7 function as a protein-binding module that can bind to a number of highly positively charged proteins. We further show that, via the MORN repeat–mediated substrate docking, SETD7 can efficiently and specifically methylate both histone and nonhistone proteins. Our results support a model in which the SETD7_MORN binds to positively charged docking sequence situated not too far away from the Lys methylation motif (i.e. with a limited linker length), thereby facilitating specific methylation of substrate proteins (Fig. 4I, left). An alternative model is that a positively charged SETD7_MORN binding protein functions as an adaptor to tether Lys methylation motif–containing proteins to be specifically and efficiently methylated by SETD7 (Fig. 4I, right). Combining the two modes of substrate docking, SEDT7 is likely to be capable of specifically methylating a large set of substrates. We have manually curated over 40 proteins that have been confirmed as substrates of SETD7 in past studies (Table S1). Among them, 69.6% are DNA/RNA-binding proteins, and 19.6% are binders of DNA/RNA-binding proteins (Fig. 4B and Table S1), supporting the SETD7 substrate recognition model proposed in Fig. 4I. Our finding that specific DNA sequences can compete with SETD7 for binding to transcription factors suggests that DNA binding may function as a regulatory mechanism for substrate accessibility of SETD7.

The substrate docking–mediated specific Lys methylation mechanism proposed for SETD7 may have general implications to other SET domain–containing methyltransferases. Most of the methyltransferases contain additional protein interaction domains either N- or C-terminal to the catalytic SET domains (SMART database; http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/).4 For example, apart from the SET domain, NSD2 has two PWWP domains, and G9a has seven ANK repeats. The PWWP domains of NSD2 and ANK repeats of G9a have been shown to bind to methylated histones, thereby tethering the enzymes to specific chromatin loci and promoting methylation of specific substrates (46–48). By analogy, the WW domain, another common protein interaction domain, in SETD2 may also function as a substrate-docking site for their specific methylation by SETD2. It is also noted that most of the protein Arg methyltransferases (PRMTs) contain various protein–protein interaction modules flanking their catalytic domain. It is tempting to speculate that PRMTs may also use an analogous substrate docking–mediated Lys methylation mechanism to achieve their catalytic specificities. Therefore, we caution that, when searching for substrates of protein methyltransferases, one should not be limited to the short methylation site motifs of potential substrates, as these peptide motifs often bind to the catalytic domain of the enzymes with low affinity and high promiscuity.

Experimental procedures

Constructs and protein expression

The full-length SETD7 (NCBI accession number NP_542983.3) and PDX1 (NCBI accession number NP_032840.1) were PCR-amplified from a mouse cDNA library. The coding sequences of DNA-binding domains of IRF1 (NCBI accession number NP_032416.1, aa 2–139), CDX1 (NCBI accession number NP_034010.3, aa 149–217), androgen receptor (NCBI accession number NP_038504.1, aa 535–625), estrogen receptor (NCBI accession number NP_031982.1, aa 181–279), GLI3 (NCBI accession number NP_032156.2, aa 431–645), CREB (NCBI accession number NP_034082.1, aa 284–341), c-Myc (NCBI accession number NP_001170823.1, aa 318–439), MyoD (NCBI accession number NP_034996.2, aa 102–170), and SOX2 (NCBI accession number NP_035573.3, aa 41–123) were PCR-amplified from a mouse cDNA library. The coding sequence of CIN85_SH3B was PCR-amplified from the mouse CIN85 cDNA as described (33). All constructs used in this study were cloned into a home-modified pET32a vector except that chimera constructs were cloned into a PETM.3C vector. In addition to pET32a, SETD7_1–194 was also cloned into a PGEX-6P-1 vector. All truncations, point mutations, and fusion constructs were generated with the standard PCR-based mutagenesis method and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Recombinant proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). The N-terminal thioredoxin-His6-tagged or His6-tagged proteins were purified with a nickel-SepharoseTM 6 Fast Flow column and subsequent Superdex 200 preparation grade size-exclusion chromatography. GST-tagged proteins were purified with GSH-Sepharose affinity chromatography. Recombinant SETD7 proteins purified through normal procedure are contaminated with cofactor SAM (34), which leads to technical difficulties in ITC titration and the in vitro methylation assay. Therefore, we incubated purified SETD7 with excess Trx-tagged TAF10 peptide encompassing the methylation site at room temperature overnight to consume SAM, and then ion-exchange and size-exclusion chromatography were performed to remove cofactor product SAH and TAF10 protein.

Analytical gel filtration chromatography

Protein samples (typically 180 μl at a concentration of 50–100 μm) were injected into an ÄKTA FPLC system with a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) using column buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100/300 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm DTT).

ITC assay

ITC measurements were performed on a MicroCal iTC200 (Malvern) at 30 °C. All proteins were dissolved in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100/300 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm DTT. When substrates (H3, TAF10 peptides, and chimera proteins) were titrated to SETD7, 300 μm SAH was included in the buffer. The concentrations of the protein in the syringe were typically 400–800 μm, whereas the concentrations of the protein in the cell were typically 40–80 μm. Each titration point was performed by injecting a 2-μl aliquot of the syringe sample into the cell sample at a time interval of 120 s to ensure that the titration curve returned to the baseline. The titration data were analyzed by Origin7.0 (Microcal) and fitted by the one-site binding model.

GST pull-down assay

GST or GST-tagged proteins were first loaded to 40 μl of GSH-Sepharose beads in an assay buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100/500 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, and 1 mm EDTA). The GST fusion protein–loaded beads were then mixed with target proteins, and the mixtures were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C. After extensive washing, proteins captured by affinity beads were eluted by SDS-PAGE sample buffer by boiling, resolved by 15% SDS-PAGE, and detected by Coomassie Blue staining. Band intensities were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Fluorescence assay

Fluorescence assays were carried out on a PerkinElmer Life Sciences LS-55 fluorimeter equipped with an automated polarizer at 25 °C. For a typical assay, an FITC-labeled peptide (∼0.1–1 μm) was titrated with a potential binding partner in 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5) buffer containing 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, and 300 μm SAH (optional). Curves were fitted by one-site binding model using Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad).

In vitro methylation assay

Methylation assays were performed in a continuous, high-throughput fashion using the MTase-GloTM methyltransferase assay kit. For a typical assay, methylation reactions were initiated by the addition of 20 μm substrates to a mixture containing 0.05–1 μm SETD7, 40 μm SAM, 2× MTase-Glo reagent in a PCR tube at 1:1 ratio. The reaction buffer contained 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mm NaCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT. After a 30-min incubation at room temperature, MTase-GloTM Detection Solution was added to the reaction at a 1:1 ratio and transferred to a 96-well solid white plate. Luminescence was determined at exactly 30 min after the addition of the Detection Solution using the GloMax 96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega). The kinetic parameters for the methylation of the TAF10, histone H3 peptides, and chimera protein were measured in duplicate using a MTase-GloTM methyltransferase assay. A series of concentrations of substrates were added to a mixture containing SETD7 (0.05 μm for TAF10 peptide and chimera protein, 0.8 μm for histone H3 peptides), 40 μm SAM, 2× MTase-Glo reagent. After a 5- or 20-min incubation, MTase-GloTM Detection Solution was added to the reaction for another 30-min incubation. Rate plots for substrate methylation were fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation (V = kcat[E][S]/(Km+[S]), using the nonlinear least-squares method in Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad). The Km and kcat values were calculated as the average of values derived from three separate experiments, and errors were S.D.

Synthetic peptides

Peptides of histone H3, TAF10, IRF1, and CDX1 were purchased from Shanghai GL Biochem Co., Ltd. The detailed sequences are as follows: TAF10_P, SKSKDRKYTL; H3_1–39, ARTKQTARKSTGGKAPRKQLATKAARKSAPATGGVKKPHY; H3_1–11, ARTKQTARKSTY; IRF1, RKERKSKSSRDTKSY; CDX1, SGKTRTKDKYRVVY. All of the above peptides except for the TAF10 peptide were synthesized with a tyrosine residue added to the C terminus to determine peptide concentrations. The FITC-labeled peptides were synthesized by Shenzhen PepBiotic Co., Ltd. FITC was labeled onto a lysine residue attached to the very C terminus. Peptide concentrations were determined by measuring their absorbance at 280 nm.

Author contributions

H. L. and J. L. formal analysis; H. L., Z. L., Q. Y., and J. L. investigation; H. L., J. L., and M. Z. methodology; H. L., J. L., and M. Z. writing-original draft; W. L. and J. W. project administration; J. L. and M. Z. supervision; J. L. and M. Z. writing-review and editing; M. Z. conceptualization; M. Z. funding acquisition.

Supplementary Material

This research was supported by National Key R&D Program of China Grant 2016YFA0501903 from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China and RGC of Hong Kong Grants AoE-M09-12 and C6004-17G (to M. Z.); National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31670765 (to W. L.), 31700673 (to H. L.), and 81571043 (to J. W.); Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province Grant 2016A030312016 (to M. Z.); and Shenzhen Basic Research Grants JCYJ20160229153100269 (to M. Z.) and JCYJ20170411090807530 (to W. L.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Table S1 and Figs. S1–S5.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- KMT

- lysine methyltransferase

- MORN

- membrane occupation and recognition nexus

- SAM

- S-adenosylmethionine

- SAH

- S-adenosyl homocysteine

- FPLC

- fast protein liquid chromatography

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- PRMT

- protein Arg methyltransferase

- aa

- amino acids

- H3K4

- histone H3 Lys-4.

References

- 1. Ambler R. P., and Rees M. W. (1959) ϵ-N-Methyl-lysine in bacterial flagellar protein. Nature 184, 56–57 10.1038/184056b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray K. (1964) The occurrence of ϵ-N-methyl lysine in histones. Biochemistry 3, 10–15 10.1021/bi00889a003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Watterson D. M., Sharief F., and Vanaman T. C. (1980) The complete amino acid sequence of the Ca2+-dependent modulator protein (calmodulin) of bovine brain. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 962–975 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang M., Huque E., and Vogel H. J. (1994) Characterization of trimethyllysine 115 in calmodulin by 14N and 13C NMR spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 5099–5105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clarke S. (1993) Protein methylation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 5, 977–983 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90080-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murn J., and Shi Y. (2017) The winding path of protein methylation research: milestones and new frontiers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 517–527 10.1038/nrm.2017.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roberts D. M., Rowe P. M., Siegel F. L., Lukas T. J., and Watterson D. M. (1986) Trimethyllysine and protein function: effect of methylation and mutagenesis of lysine 115 of calmodulin on NAD kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 1491–1494 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strahl B. D., Ohba R., Cook R. G., and Allis C. D. (1999) Methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 is highly conserved and correlates with transcriptionally active nuclei in Tetrahymena. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14967–14972 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rea S., Eisenhaber F., O'Carroll D., Strahl B. D., Sun Z. W., Schmid M., Opravil S., Mechtler K., Ponting C. P., Allis C. D., and Jenuwein T. (2000) Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature 406, 593–599 10.1038/35020506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu S., Hausmann S., Carlson S. M., Fuentes M. E., Francis J. W., Pillai R., Lofgren S. M., Hulea L., Tandoc K., Lu J., Li A., Nguyen N. D., Caporicci M., Kim M. P., Maitra A., et al. (2019) METTL13 methylation of eEF1A increases translational output to promote tumorigenesis. Cell 176, 491–504.e21 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clarke S. G. (2013) Protein methylation at the surface and buried deep: thinking outside the histone box. Trends Biochem. Sci. 38, 243–252 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Biggar K. K., and Li S. S. (2015) Non-histone protein methylation as a regulator of cellular signalling and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 5–17 10.1038/nrm3915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Del Rizzo P. A., and Trievel R. C. (2011) Substrate and product specificities of SET domain methyltransferases. Epigenetics 6, 1059–1067 10.4161/epi.6.9.16069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cornett E. M., Dickson B. M., Krajewski K., Spellmon N., Umstead A., Vaughan R. M., Shaw K. M., Versluis P. P., Cowles M. W., Brunzelle J., Yang Z., Vega I. E., Sun Z. W., and Rothbart S. B. (2018) A functional proteomics platform to reveal the sequence determinants of lysine methyltransferase substrate selectivity. Sci. Adv. 4, eaav2623 10.1126/sciadv.aav2623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carlson S. M., and Gozani O. (2016) Nonhistone lysine methylation in the regulation of cancer pathways. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 6, a026435 10.1101/cshperspect.a026435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hornbeck P. V., Zhang B., Murray B., Kornhauser J. M., Latham V., and Skrzypek E. (2015) PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D512–D520 10.1093/nar/gku1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Couture J. F., Collazo E., Hauk G., and Trievel R. C. (2006) Structural basis for the methylation site specificity of SET7/9. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 140–146 10.1038/nsmb1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luo M. (2018) Chemical and biochemical perspectives of protein lysine methylation. Chem. Rev. 118, 6656–6705 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martin C., and Zhang Y. (2005) The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 838–849 10.1038/nrm1761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang H., Cao R., Xia L., Erdjument-Bromage H., Borchers C., Tempst P., and Zhang Y. (2001) Purification and functional characterization of a histone H3-lysine 4-specific methyltransferase. Mol. Cell 8, 1207–1217 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00405-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nishioka K., Chuikov S., Sarma K., Erdjument-Bromage H., Allis C. D., Tempst P., and Reinberg D. (2002) Set9, a novel histone H3 methyltransferase that facilitates transcription by precluding histone tail modifications required for heterochromatin formation. Genes Dev. 16, 479–489 10.1101/gad.967202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chuikov S., Kurash J. K., Wilson J. R., Xiao B., Justin N., Ivanov G. S., McKinney K., Tempst P., Prives C., Gamblin S. J., Barlev N. A., and Reinberg D. (2004) Regulation of p53 activity through lysine methylation. Nature 432, 353–360 10.1038/nature03117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kouskouti A., Scheer E., Staub A., Tora L., and Talianidis I. (2004) Gene-specific modulation of TAF10 function by SET9-mediated methylation. Mol. Cell 14, 175–182 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00182-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Subramanian K., Jia D., Kapoor-Vazirani P., Powell D. R., Collins R. E., Sharma D., Peng J., Cheng X., and Vertino P. M. (2008) Regulation of estrogen receptor α by the SET7 lysine methyltransferase. Mol. Cell 30, 336–347 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kontaki H., and Talianidis I. (2010) Lysine methylation regulates E2F1-induced cell death. Mol. Cell 39, 152–160 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Estève P. O., Chin H. G., Benner J., Feehery G. R., Samaranayake M., Horwitz G. A., Jacobsen S. E., and Pradhan S. (2009) Regulation of DNMT1 stability through SET7-mediated lysine methylation in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5076–5081 10.1073/pnas.0810362106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu X., Chen Z., Xu C., Leng X., Cao H., Ouyang G., and Xiao W. (2015) Repression of hypoxia-inducible factor alpha signaling by Set7-mediated methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 5081–5098 10.1093/nar/gkv379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Batista I. A. A., and Helguero L. A. (2018) Biological processes and signal transduction pathways regulated by the protein methyltransferase SETD7 and their significance in cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 3, 19 10.1038/s41392-018-0017-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Munro S., Khaire N., Inche A., Carr S., and La Thangue N. B. (2010) Lysine methylation regulates the pRb tumour suppressor protein. Oncogene 29, 2357–2367 10.1038/onc.2009.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu X., Wang D., Zhao Y., Tu B., Zheng Z., Wang L., Wang H., Gu W., Roeder R. G., and Zhu W. G. (2011) Methyltransferase Set7/9 regulates p53 activity by interacting with Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1925–1930 10.1073/pnas.1019619108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oudhoff M. J., Freeman S. A., Couzens A. L., Antignano F., Kuznetsova E., Min P. H., Northrop J. P., Lehnertz B., Barsyte-Lovejoy D., Vedadi M., Arrowsmith C. H., Nishina H., Gold M. R., Rossi F. M., Gingras A. C., and Zaph C. (2013) Control of the hippo pathway by Set7-dependent methylation of Yap. Dev. Cell 26, 188–194 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shen C., Wang D., Liu X., Gu B., Du Y., Wei F. Z., Cao L. L., Song B., Lu X., Yang Q., Zhu Q., Hou T., Li M., Wang L., Wang H., Zhao Y., Yang Y., and Zhu W. G. (2015) SET7/9 regulates cancer cell proliferation by influencing β-catenin stability. FASEB J. 29, 4313–4323 10.1096/fj.15-273540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li Q., Yang W., Wang Y., and Liu W. (2018) Biochemical and structural studies of the interaction between ARAP1 and CIN85. Biochemistry 57, 2132–2139 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Del Rizzo P. A., Couture J. F., Dirk L. M., Strunk B. S., Roiko M. S., Brunzelle J. S., Houtz R. L., and Trievel R. C. (2010) SET7/9 catalytic mutants reveal the role of active site water molecules in lysine multiple methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 31849–31858 10.1074/jbc.M110.114587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wilson J. R., Jing C., Walker P. A., Martin S. R., Howell S. A., Blackburn G. M., Gamblin S. J., and Xiao B. (2002) Crystal structure and functional analysis of the histone methyltransferase SET7/9. Cell 111, 105–115 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00964-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kwon T., Chang J. H., Kwak E., Lee C. W., Joachimiak A., Kim Y. C., Lee J., and Cho Y. (2003) Mechanism of histone lysine methyl transfer revealed by the structure of SET7/9-AdoMet. EMBO J. 22, 292–303 10.1093/emboj/cdg025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li J., Liu H., Raval M. H., Wan J., Yengo C. M., Liu W., and Zhang M. (2019) Structure of the MORN4/Myo3a tail complex reveals MORN repeats as protein binding modules. Structure 27 10.1016/j.str.2019.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Francis J., Chakrabarti S. K., Garmey J. C., and Mirmira R. G. (2005) Pdx-1 links histone H3-Lys-4 methylation to RNA polymerase II elongation during activation of insulin transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36244–36253 10.1074/jbc.M505741200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Longo A., Guanga G. P., and Rose R. B. (2007) Structural basis for induced fit mechanisms in DNA recognition by the Pdx1 homeodomain. Biochemistry 46, 2948–2957 10.1021/bi060969l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wingender E., Schoeps T., Haubrock M., Krull M., and Dönitz J. (2018) TFClass: expanding the classification of human transcription factors to their mammalian orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D343–D347 10.1093/nar/gkx987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ma P. C., Rould M. A., Weintraub H., and Pabo C. O. (1994) Crystal structure of MyoD bHLH domain-DNA complex: perspectives on DNA recognition and implications for transcriptional activation. Cell 77, 451–459 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90159-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tao Y., Neppl R. L., Huang Z. P., Chen J., Tang R. H., Cao R., Zhang Y., Jin S. W., and Wang D. Z. (2011) The histone methyltransferase Set7/9 promotes myoblast differentiation and myofibril assembly. J. Cell Biol. 194, 551–565 10.1083/jcb.201010090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ibáñez G., McBean J. L., Astudillo Y. M., and Luo M. (2010) An enzyme-coupled ultrasensitive luminescence assay for protein methyltransferases. Anal. Biochem. 401, 203–210 10.1016/j.ab.2010.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dhayalan A., Kudithipudi S., Rathert P., and Jeltsch A. (2011) Specificity analysis-based identification of new methylation targets of the SET7/9 protein lysine methyltransferase. Chem. Biol. 18, 111–120 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wilson D., Charoensawan V., Kummerfeld S. K., and Teichmann S. A. (2008) DBD–taxonomically broad transcription factor predictions: new content and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D88–D92 10.1093/nar/gkm964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sankaran S. M., Wilkinson A. W., Elias J. E., and Gozani O. (2016) A PWWP domain of histone-lysine N-methyltransferase NSD2 binds to dimethylated Lys-36 of histone H3 and regulates NSD2 function at chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 8465–8474 10.1074/jbc.M116.720748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu N., Zhang Z., Wu H., Jiang Y., Meng L., Xiong J., Zhao Z., Zhou X., Li J., Li H., Zheng Y., Chen S., Cai T., Gao S., and Zhu B. (2015) Recognition of H3K9 methylation by GLP is required for efficient establishment of H3K9 methylation, rapid target gene repression, and mouse viability. Genes Dev. 29, 379–393 10.1101/gad.254425.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Collins R. E., Northrop J. P., Horton J. R., Lee D. Y., Zhang X., Stallcup M. R., and Cheng X. (2008) The ankyrin repeats of G9a and GLP histone methyltransferases are mono- and dimethyllysine binding modules. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 245–250 10.1038/nsmb.1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.