Abstract

Cold acclimation and vegetative/reproductive transition are two important evolutionary adaptive mechanisms for winter wheat surviving the freezing temperature in winter and successful seeds setting in the next year. MicroRNA (miRNA) is a class of regulatory small RNAs (sRNAs), which plays critical roles in the growth and development of plants. However, the regulation mechanism of miRNAs during cold acclimation and vegetative/reproductive transition of winter wheat is not much understood. In this study, four sRNA libraries from leaves of winter wheat grown in the field at the three-leaf stage, winter dormancy stage, spring green-up stage, and jointing stage were analyzed to identify known and novel miRNAs and to understand their potential roles in the growth and development of winter wheat. We examined miRNA expression using a high-throughput sequencing technique. A total of 373 known, 55 novel, and 27 putative novel miRNAs were identified. Ninety-one miRNAs were found to be differentially expressed at the four stages. Among them, the expression of six known and eight novel miRNAs was significantly suppressed at the winter dormancy stage, whereas the expression levels of seven known and eight novel miRNAs were induced at this stage; three known miRNAs and three novel miRNAs were significantly induced at the spring green-up stage; six known miRNAs were induced at the spring green-up stage and reached the highest expression level at the jointing stage; and 20 known miRNAs and 10 novel miRNAs were significantly induced at the jointing stage. Expression of a number of representative differentially expressed miRNAs was verified using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Potential target genes for known and novel miRNAs were predicted. Moreover, six novel target genes for four Pooideae species-specific miRNAs and two novel miRNAs were verified using the RNA ligase-mediated 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RLM-5’RACE) technique. These results indicate that miRNAs are key non-coding regulatory factors modulating the growth and development of wheat. Our study provides valuable information for in-depth understanding of the regulatory mechanism of miRNAs in cold acclimation and vegetative/reproductive transition of winter wheat grown in the field.

Keywords: winter wheat, miRNAs, expression, growth and development, target gene

Introduction

Flowering at favorable conditions is an important adaptive trait for reproductive success. Plants have evolved to transit from the vegetative to the reproductive growth phase at a particular time of year to ensure maximal reproductive success in a given region (Amasino and Michaels, 2010; Bouché et al., 2017). Generally, wheat cultivars are divided into two types: winter wheat and spring wheat; winter wheat requires prolonged exposure to cold temperatures to accelerate flowering (vernalization), whereas spring wheat does not require vernalization. Vernalization is regulated by diverse genetic and epigenetic networks (Xu and Chong, 2018). The roles of and interaction among several key vernalization associated genes, like VRN1, VRN2, VRN3, VER2 (a carbohydrate-binding protein) and wheat GRP2 (an RNA-binding protein), have been studied considerably well at gene expression and protein interaction levels (Danyluk et al., 2003; Yan et al., 2003; Yan et al., 2006; Oliver et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2014). Under natural growth conditions, seeds of winter wheat are usually sown in the autumn; therefore, cold acclimation and vegetative/reproductive transition are two important evolutionary adaptive mechanisms for winter wheat surviving the freezing temperature in winter and successful seeds setting in the next year. The molecular basis of cold acclimation in plants has been extensively studied in Arabidopsis, wheat, and barley (Thomashow, 1999; Kim et al., 2009; Thomashow, 2010; Vashegyi et al., 2013; Li et al., 2018). However, little is known about the regulatory mechanism of small RNAs (sRNAs), especially microRNAs (miRNAs), during cold acclimation and vegetative/reproductive transition of winter wheat grown in the field.

MicroRNAs are single-stranded, ∼20- to 22-nt-long RNA molecules, which have emerged as a prominent class of regulatory RNAs. They regulate target gene expression post-transcriptionally through sequence complementary dependent cleavage or translational inhibition (Llave et al., 2002; Rogers and Chen, 2013; Yu et al., 2017). The critical role of miRNAs in developmental processes is reflected not only in pleiotropic developmental defects associated with miRNA biogenesis mutants, dcl1, hyl1, hen1, se1, and ago1, but also in the fact that considerable data are available for the involvement of miRNAs in tissue and organ development in several plant species (Yu et al., 2017). miR156 is highly expressed early in juvenile plants and decreases as they transition to the reproductive stage, whereas miR172 shows an inverse temporal expression pattern (Poethig, 2009; Wu et al., 2009). Most squamosa promoter binding-like (SPL) transcription factors (TFs) in Arabidopsis are regulated by miR156 and influence plant developmental processes, such as phase transition from the juvenile to the adult stage, root development, and leaf morphology (Wu and Poethig, 2006; Gao et al., 2017). SPL9 directly activates the expression of miR172 to facilitate flowering by suppressing the APETALA2 (AP2) protein (Aukerman and Sakai, 2003; Wu et al., 2009; Zhu and Helliwell, 2011). Overexpression of miR156 in Arabidopsis, switchgrass, rice, maize, and Chinese cabbage was reported to prolong the juvenile phase and increase the total leaf/tiller numbers and biomass but resulted in delayed flowering (Wu and Poethig, 2006; Schwarz et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009; Fu et al., 2012). Elevated expression of miR159 in Arabidopsis resulted in a delay in flowering under a short-day photoperiod through its effects on gibberellin- and abscisic acid-regulated MYB (GAMYB) activity (Achard et al., 2004). miR396 regulates the expression of growth regulating factor (GRF) genes involved in the control of cell proliferation during leaf and root development (Rodriguez et al., 2010; Bazin et al., 2013). Increasing evidence indicates that miRNAs are involved in the regulation of seed/grain development in crop plants. In rice, OsSPL16/GW8, targeted by miR156, controls the size, shape, and quality of grains by promoting cell division and grain filling (Wang et al., 2012a). Overexpression of miR397 could improve the yield in rice plants by increasing the grain size and promoting panicle branching (Zhang et al., 2013).

In wheat, about a dozen studies have been performed on miRNA identification using sRNA sequencing (sRNA-Seq) (Yao et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2009; Li et al., 2013; Meng et al., 2013; De Paola et al., 2016; Fileccia et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). miRNAs responding to diverse stresses in wheat have also been reported (Xin et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2015; Akdogan et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2017; Zuluaga et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018). miRNAs related to the development and filling of wheat seeds have been studied (Meng et al., 2013; Han et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018). For example, Meng et al. (2013) identified 104 miRNAs associated with grain filling in wheat. Han et al. (2014) found that 4 known miRNA families and 22 novel miRNAs were preferentially expressed in developing seeds. Little is known about miRNAs and their regulatory functions in the cold acclimation and vegetative/reproductive transition of winter wheat grown in the field under natural weather conditions. Therefore, this study aimed to systematically identify the conserved and novel miRNAs in wheat leaves at different growth stages under natural growth conditions. To achieve this, we sequenced four sRNA libraries prepared from wheat leaves at the three-leaf stage, winter dormancy stage, spring green-up stage, and jointing stage. This study provides useful information for uncovering the regulatory networks of miRNAs in wheat leaves at different growth and developmental stages.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) variety Shimai 22 was used in this study. Shimai 22 is a high-yield semi-winter wheat variety bred by Shijiazhuang Academy of Agriculture and Forestry (Shijiazhuang, Hebei, China) and is widely grown in the northern region of the Huang-Hai plain (Fu et al., 2016). Wheat seeds were planted on October 1, 2015, at the Wheat Experimental Station of Henan Normal University (35°19′ N, 113°54′ E). The top two fully expanded leaves were collected at the three-leaf stage before the cold winter (Leaf_1, October 24, 2015), winter dormancy stage (Leaf_2, January 7, 2016), spring green-up stage or double ridge stage (Leaf_3, March 4, 2016), and jointing stage (Leaf_4, April 10, 2016). Three independent samples were collected and used as biological replicates. All the samples were collected at the same time (between 1:30 and 3:00 PM) to minimize the circadian rhythm effect, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until RNA isolation.

Construction and Sequencing of Small RNA Library

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity of the RNA samples was checked using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and further checked by Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. Equal amounts of total RNA samples from three biological replicates were mixed and sent to BGI (Shenzhen, China) for construction of sRNA libraries. Small RNAs, ranging in length from 18 to 30 nt, were enriched and purified by 15% denatured polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Thereafter, 3′- and 5′-RNA adaptors were ligated to sRNAs. This was followed by reverse transcription and final polymerase chain reaction (PCR) enrichment. The sRNA libraries were PAGE-purified (Wang et al., 2015). High-throughput sequencing of the four sRNA libraries was performed on a BGISEQ500RS platform.

Bioinformatics Analysis of sRNA Sequence Data

Raw reads generated by deep sequencing were analyzed, as described previously (Jagadeeswaran et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2016). Briefly, raw reads were first filtered by removing low-quality reads and trimming the adaptor sequences, and clean reads (18–30 nt) were obtained for each sRNA library. Identical reads were pooled to generate non-redundant sequences (unique reads). Small RNAs originating from rRNAs, tRNAs, small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), and repeat RNAs were further removed by alignment against database Rfam (r12) (Nawrocki et al., 2015), NONCODE (v3.0) (Bu et al., 2012), GtRNAdb (Chan and Lowe, 2008), Plant Repeat Databases (Bao et al., 2015), and Repbase (r20) (Bao et al., 2015) using SOAP (Li et al., 2009). The remaining sRNAs were first used to identify the known miRNAs. Sequences of mature miRNAs from all plant species were downloaded from miRBase Release 21.0 (http://www.mirbase.org) and combined to obtain all known plant miRNA sequences. The known miRNAs in wheat leaves were identified by BLAST search against all known plant miRNA sequences. Small RNAs with fewer than two mismatches with known plant miRNAs were considered as the known wheat miRNAs. The remaining sRNAs were used to identify novel wheat miRNAs using MIREAP software (http://sourceforge.net/projects/mireap/). They were first mapped to the genome of Chinese Spring wheat (ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/plants/release-31/fasta/triticum_aestivum/), and only perfectly matched sRNAs were used for further analysis. The flanking regions (150 nt upstream and 150 nt downstream) of sRNAs were isolated and used to predict fold-back structure with the RNAfold software (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi). The fold-back structures of novel miRNAs were further checked manually using the Mfold Web Server (Zuker, 2003). The key criteria for novel miRNA annotation were based on the ones described in a recent article (Axtell and Meyers, 2018). Only those miRNAs with an abundance of more than 50 reads in at least one leaf sample together with detected miRNA* were considered as novel miRNAs. Those for which miRNA* were not detected but that could form a typical miRNA precursor fold-back structure were considered as wheat putative miRNAs.

Identification and Validation of Differentially Expressed miRNAs

To quantify miRNA expression, tags per million reads (TPM) was used to normalize the miRNA expression levels. We first compared the expression patterns of the identified miRNAs at the four different growth and development stages using GENESIS (Sturn et al., 2002). Thereafter, DEGseq was used to screen the differentially expressed miRNAs (Wang et al., 2010). MicroRNAs with fold change ≥ 2 between samples and p-value less than 0.01 were defined as differentially expressed miRNAs (DEG miRNAs). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to validate the expression patterns of miRNAs. Briefly, total RNA, including sRNAs, was first polyadenylated and then reverse-transcribed with poly (T) oligonucleotide into cDNA using a Mir-X miRNA qRT-PCR SYBR Kit (Takara Co., Tokyo, Japan), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR was carried out using a SYBR Green (Takara) qPCR assay and LightCycler® 96 Real-Time PCR System (Roche). miRNA-specific forward primer was designed based on the miRNA sequence. The sequences of these primers are listed in Supplemental Table S1 . The universal reverse primer was provided in the Mir-X miRNA qRT-PCR SYBR Kit. All reactions were run in triplicates; U6 was used as the reference gene. Dissociation curves were checked to determine the presence of nonspecific products, and only primers resulting in a single peak and an amplicon of the correct size, as verified on an agarose gel, were used to evaluate the expression of miRNAs. The expression level of miRNAs at the three-leaf stage (Leaf_1) was set as 1.0, and the relative expression levels of miRNAs at other stages were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Prediction and Validation of the Targets of Wheat miRNAs

The potential targets of wheat miRNAs were predicted using the PsRobot pipeline (http://omicslab.genetics.ac.cn/psRobot/). Only those targets with alignment scores between the query miRNA and targets less than 2.5 were considered. RNA ligase-mediated 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RLM-5′RACE) was carried out to validate the predicted target genes using a GeneRacer kit (Invitrogen, USA). Total RNA was treated with DNase I; RNA oligo adaptor was directly ligated to total RNA, and GeneRacer oligo dT primer and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA) were used to synthesize the first-strand cDNAs. This was followed by nested PCR and electrophoresis of PCR products on a 2% agarose gel. The bands with expected sizes were purified using a QIAquickⓇ Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN) and ligated to pMD19-T (Simple) vector (Takara). The ligation was transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells, and positive colonies identified using colony PCR were used for isolation of plasmids, which were subjected to Sanger sequencing (Li et al., 2010).

Results

Overview of sRNA Library Sequencing Data

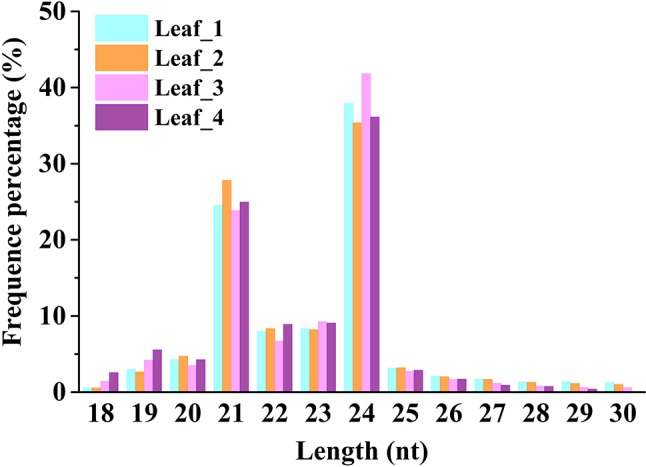

To study the involvement of regulatory miRNAs in wheat leaves during cold acclimation and vegetative/reproductive transition, four sRNA libraries were generated and sequenced. The four libraries represent the four growth stages of winter wheat grown in the field under natural weather conditions, viz. three-leaf stage, winter dormancy stage, spring green-up stage, and jointing stage. All sequencing data were first processed by filtering low-quality reads and trimming adaptor sequences, and clean reads were generated for each sRNA library. Identical reads were subsequently pooled to create unique reads. A total of 90,372,481 clean reads representing 36,634,063 unique reads, ranging in length from 18 to 30 nt, were obtained for further analysis. The length distribution of sRNA libraries is summarized in Figure 1 . All four libraries shared a similar distribution pattern. The most abundant sRNA reads were 24 nt long (about 30%), followed by reads of 21 nt length (15%), which is the typical length of canonical miRNAs ( Figure 1 ). The patterns were consistent with the typical read distribution reported in other studies. The percentage of reads mapping to wheat genome was >87.82%, and reads mapping to tRNAs, rRNAs, snoRNAs, and snRNAs accounted for ∼8.35%–14.42% of the total reads, indicating a high quality of all the sRNA libraries prepared ( Table 1 ).

Figure 1.

Size distribution of small RNAs in wheat leaves at four different growth and development stages. Leaf_1, Leaf_2, Leaf_3, and Leaf_4 represent wheat leaves collected at the three-leaf stage, winter dormancy stage, spring green-up stage, and jointing stage, respectively.

Table 1.

Read statistics of four wheat leaf small RNA libraries.

| Type | Raw reads | Clean reads | Mapped reads | rRNA | snRNA | snoRNA | tRNA | Unique reads |

Unique reads mapped |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf_1 | 23,609,453 | 22526694 (100%) | 20300798 (90.12%) | 2643342 (11.74%) | 8960 (0.04%) | 3684 (0.02%) | 485426 (2.15%) | 9355147 (100%) | 7915731 (84.61%) |

| Leaf_2 | 23,497,910 | 22543808 (100%) | 20548305 (91.15%) | 2591106 (11.49%) | 6251 (0.03%) | 1931 (0.01%) | 425319 (1.89%) | 8201915 (100%) | 6935745 (84.56%) |

| Leaf_3 | 21,410,747 | 20444752 (100%) | 18127870 (88.67%) | 1290962 (6.31%) | 3670 (0.02%) | 936 (0.005%) | 408480 (2%) | 8877395 (100%) | 7377298 (83.10%) |

| Leaf_4 | 25,877,348 | 24857227 (100%) | 21830151 (87.82%) | 1570443 (6.32%) | 16601 (0.07%) | 3007 (0.01%) | 768556 (3.09%) | 10199606 (100%) | 8090818 (79.32%) |

| Total | 94,395,458 | 90,372,481 (100%) |

80,807,124 | 8,095,853 | 35,482 | 9,558 | 2,087,781 | 36,634,063 | 30,319,592 |

Identification of Known miRNAs in Wheat Leaves

For identifying the known miRNAs in wheat, we first downloaded the mature miRNA sequences from all plant species present in miRBase and combined them to obtain all known plant miRNA sequences. The unique reads from the four wheat sRNA libraries were aligned with all known plant miRNA sequences using BLASTN search. The unique reads that matched the known plant miRNA sequences with ≤2 mismatches were annotated as known wheat miRNAs. A total of 373 known miRNAs belonging to 289 miRNA families were identified from the four libraries. The 24 most conserved plant miRNAs (miR156/157, miR159, miR160, miR161, miR162, miR164, miR165/166, miR167, miR168, miR169, miR170/171, miR172, miR319, miR390, miR391, miR393, miR394, miR395, miR396, miR397, miR398, miR399, miR408, and miR444) were identified among these known miRNAs. Wheat has 125 mature miRNAs belonging to 99 miRNA families in miRBase (Release 22.1), of which 77 miRNA families (77.8%) were found in this study, indicating the deep sequencing coverage of the four sRNA libraries.

Among the conserved miRNAs, miR168 was found to be the most abundant miRNA at all four stages (more than 109,365 TPM) and was followed in abundance by miR159, miR167, miR170/171, and miR396; miR156/157, miR164, miR165/166, miR319, miR393, and monocot-specific miR444 were also found to have high expression levels, whereas miR161, miR162, miR390, miR391, miR394, and miR408 showed relatively low expression levels. Among the less conserved known miRNAs, most exhibited low expression levels, whereas miR5048, miR5062, miR5200, miR7757, miR9962, miR9672b, miR9674, and miR9773 were expressed at high levels in wheat leaves at all four growth and development stages ( Supplemental Table S2 ). These data indicate that expression of miRNAs in leaf tissues at different growth stages varies greatly among the different miRNA families.

Identification of Novel miRNAs From Wheat Leaves

High-throughput sequencing has the potential for detecting novel miRNAs with low expression in the sRNA transcriptome. The remaining sRNA sequences that did not have any homologs with known plant miRNAs were used to predict potential novel miRNAs using MIREAP software. Only those sRNAs with more than 50 reads in at least one library were used for further analysis. We manually checked the hairpin structure of the predicted novel miRNAs by Mfold software (Zuker, 2003), and only those with the typical stem-loop structure were considered ( Supplemental File S1 – S2 ). A total of 55 novel miRNAs, for which corresponding miRNAs* were detected, were identified. The length of these novel miRNAs and miRNAs* varied from 20 to 23 nt ( Table 2 ). The locations of their precursors and their sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S3 . Among them, novel_miR127, novel_miR128, novel_miR390, novel_miR1544, novel_miR1560, and novel_miR1686 were the most abundantly expressed miRNAs, and their expression levels were higher than those of some conserved miRNAs ( Supplemental Table S4 ). We also assigned 27 putative novel miRNAs, and although no corresponding miRNA* was detected for them, their precursors could form the characteristic hairpin structure ( Supplemental File 2 ); novel_miR1202, novel_miR527, novel_miR1327, novel_miR1620, novel_miR1356, and novel_miR1615 were relatively abundant putative miRNAs identified in wheat leaves ( Supplemental Table S5 ). The information of the putative miRNA precursors and their chromosome location are shown in Supplemental Table S6 .

Table 2.

Expression of novel miRNAs.

| miR_name | miRNA location | miRNA expression (TPM) | miRNA sequence | miRNA length (nt) | miRNA* sequence | miRNA* length (nt) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf_1 | Leaf_2 | Leaf_3 | Leaf_4 | ||||||

| novel_miR30 | 3p | 15.3 | 22.9 | 14.2 | 9.2 | CAUUUUCCUAUAGACUUGGUC | 21 | CCAAGUCUAGAGAAUAAUGUA | 21 |

| novel_miR127 | 5p | 49.5 | 53.8 | 50.8 | 34.6 | UUUGAAGACUAGUUUAUUACA | 21 | UAAUAAACAAGUCUUUAGAUG | 21 |

| novel_miR128 | 5p | 115.0 | 133.8 | 94.4 | 92.1 | UCUGAAGACUAGUUUAUUACA | 21 | UAAUAGACAAGUCUUUUGAUG | 21 |

| novel_miR193 | 3p | 24.6 | 17.6 | 8.6 | 9.9 | UAAGCACCUCCCCUAAGCACCU | 22 | AUGCUUAGGGAGGUGUUUAGA | 21 |

| novel_miR259 | 5p | 6.5 | 18.8 | 19.1 | 16.2 | GAGAUGACACCGACGCCGAUC | 21 | UCGGAGUUGGUGUCACCUCGC | 21 |

| novel_miR364 | 3p | 1.9 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 2.7 | UAAUGUUGCAACGUCCUGAAC | 21 | UCAGGACGUUGCAACAUUAAC | 21 |

| novel_miR381 | 5p | 2.7 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 2.0 | AUUACUUGUCGCGAAAAUGGA | 21 | CAUUUCCGAGACAAGUAAUUU | 21 |

| novel_miR390 | 3p | 101.2 | 143.1 | 246.9 | 220.2 | UCCGCGAUCAUCACGACCAAA | 21 | UUUGGUCGUGAUUAUCGCGGU | 21 |

| novel_miR553 | 3p | 3.2 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 1.0 | AAAAAAGAUGGAGUGGCAAUUC | 22 | AUUGCCACUUAAUACUUUUUUGC | 23 |

| novel_miR639 | 5p | 2.7 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.4 | AGUUGAAGAUGAGAUAUUGAA | 21 | CAAUAUCUCAUUUUCAACUAU | 21 |

| novel_miR641 | 3p | 3.2 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 2.4 | UUAUAUUAUGUGACAGAAGGA | 21 | CUUCCGUCUCAUAAUAUAAAA | 21 |

| novel_miR652 | 5p | 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.3 | GAAUUACUUGUCGCGAAAAUG | 21 | UUUUCGCGACAAGUAAUUCCG | 21 |

| novel_miR669 | 3p | 4.7 | 6.4 | 12.9 | 3.3 | AGUGGCCCAACUGCACCCUGC | 21 | GCAGGGUGCAGUUGGGUCACU | 21 |

| novel_miR678 | 5p | 4.7 | 11.4 | 2.9 | 7.2 | GAAGGGGAGCCUUGGCGCAGUGG | 23 | ACAUGCACCGGGCUGCCCUUUCUA | 24 |

| novel_miR692 | 3p | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0 | 6.5 | UCAGGUCGCCCCCGCUGGAGC | 21 | UCCUGCGGGGUCGAACUGGGA | 21 |

| novel_miR810 | 3p | 25.2 | 39.5 | 21.3 | 59.3 | AUGCCGUGUUGUUCUGAAAGAA | 22 | CUUCAGAAGAGCAUGUCAUUU | 21 |

| novel_miR866 | 5p | 14.0 | 19.0 | 11.1 | 0.4 | UAGUCUCGUCCUCUUGCUAAG | 21 | UGGCGAGGAUACGAGACUAUA | 21 |

| novel_miR1009 | 5p | 3.9 | 7.2 | 3.6 | 5.8 | UUCCGAAUUACUUGUCGCAGA | 21 | UGCGACGAGUAAGUUGGAACG | 21 |

| novel_miR1154 | 5p | 13.3 | 7.4 | 18.7 | 62.2 | AAAAAGAAUGACCUCAUUGUC | 21 | CAAUGAGAUCAUUCUUUUUAU | 21 |

| novel_miR1255 | 3p | 11.2 | 13.8 | 10.2 | 0 | AAGAAGAGGGUCAAGAAAGCUG | 22 | GCUUUCUUGAACUUCUCUUGC | 21 |

| novel_miR1304 | 3p | 15.6 | 16.8 | 14.9 | 6.9 | AUAUCAAGCACUCAUCGACAG | 21 | GCCGGUGAGUGCUUUAUAUCU | 21 |

| novel_miR1322 | 3p | 41.0 | 44.0 | 37.8 | 0 | UUUUUGGAUGUGCUCCUCUAG | 21 | AGAGAAGCACAUACAAAAAAA | 21 |

| novel_miR1372 | 5p | 10.0 | 19.5 | 9.9 | 7.7 | UUUCCGGUUCCACCUCGGCCGC | 22 | AGCCGAGUGGCACCGGUAACU | 21 |

| novel_miR1401 | 5p | 1.8 | 4.1 | 1.8 | 1.2 | CCCUCCGUCCCAUAAUAUAAG | 21 | UAUAUUAUGGAACGGGCGAA | 20 |

| novel_miR1419 | 3p | 33.0 | 33.2 | 13.9 | 4.9 | AAAUGCGGUUGUUGUUCCCUA | 21 | GGAACAACAACCGCAUUUUC | 20 |

| novel_miR1544 | 3p | 535.9 | 915.8 | 267.9 | 455.0 | AGUCUCUGCCAAUUCUUCGUG | 21 | CGAAGGAUUUGCAGAUACUCC | 21 |

| novel_miR1560 | 5p | 757.2 | 777.6 | 0 | 0 | UAAACCUUCACAAAUUCCCUUG | 22 | AGGAAUUUGUGAGGUUUACA | 20 |

| novel_miR1613 | 5p | 1.6 | 3.0 | 6.2 | 1.5 | UGGGCGUACGGAACACGGGUG | 21 | CCCGUGUUCACGUACGCCCAUC | 22 |

| novel_miR1617 | 5p | 5.6 | 4.9 | 0 | 5.5 | UGAAUCUUGGGAAAAAGCUG | 20 | GAUUUUUCACCAAUAUUCAAG | 21 |

| novel_miR1686 | 5p | 88.9 | 159.6 | 102.2 | 89.1 | UCAUCUGAAGACUAGUUUAUU | 21 | UCAUCUGAAGACUAGUUUAUU | 21 |

| novel_miR1737 | 3p | 8.7 | 13.4 | 6.9 | 19.1 | AUUGAACUAAGGAGGGGUGGA | 21 | CAACCCUCUUUAGUUCAAUCA | 21 |

| novel_miR1744 | 3p | 4.0 | 5.8 | 3.8 | 0.0 | AAUGACUUAUACACCGGGACG | 21 | UCCGGGUGUAUAAGUCAUUCG | 21 |

| novel_miR1875 | 3p | 17.9 | 17.0 | 31.3 | 38.3 | UAAUCUCACCUCAACAGCCGC | 21 | AGCCGUUGAGAUGAGAUUACC | 21 |

| novel_miR2079 | 5p | 49.3 | 28.7 | 8.4 | 0 | UGGUCUGUGUUUGUUUCAAAC | 21 | UUGAGACGAAAACAGACCAAC | 21 |

| novel_miR2133 | 3p | 1.3 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.1 | AUCCGUAUCUAGACAAAUCUAAG | 23 | UGGAUUUGUCUAGAUAUAGAUGU | 23 |

| novel_miR2185 | 3p | 17.0 | 0.0 | 13.7 | 10.7 | UCAUUUGGCAUUGCUUUCCCU | 21 | AGAAAGCAAUGUCAGAGGAGU | 21 |

| novel_miR2191 | 5p | 6.1 | 5.6 | 9.2 | 6.5 | UGAUCCCACGUCUAAGGCCUG | 21 | GGACUUAGAACAUGGGGUCGAC | 22 |

| novel_miR2567 | 5p | 0 | 12.1 | 11.6 | 0 | UCAUCAAUUUCUGUCUAACUA | 21 | GUUAGACAGAAAUUGAUGAAG | 21 |

| novel_miR2745 | 5p | 0 | 198.2 | 0 | 0 | AACUGGUCUUGCUUAAUUUUG | 21 | AGAUUAAGCAAGGUCACUUGA | 21 |

| novel_miR2917 | 3p | 0 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 | AUGCCGUGUUGUUCUGAAAGAAA | 23 | UCUUCAGAAGAGCAUGUCAUUU | 22 |

| novel_miR3314 | 5p | 0 | 6.7 | 0 | 0 | UGAAGAGCGCGGGCAGCACAA | 21 | GUGCUGCCCGCGCUCUUCAUG | 21 |

| novel_miR3417 | 3p | 0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 2.8 | GAAUGGGAUUCGCUUGGGCAA | 21 | UUCCAACGGACUCAUUCCA | 19 |

| novel_miR3607 | 3p | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 13.8 | GAAUGGGAUUCGCUUGGGCA | 20 | UCCAACGGACUCAUUCCAUG | 20 |

| novel_miR3791 | 3p | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 12.6 | GAGAGGGAGGGCAGAGGCCU | 20 | AAGCUCUGCCCUUCCAUCUCUUG | 23 |

| novel_miR4191 | 5p | 0 | 0 | 11.5 | 0 | CACGAUACUCUUGGACGAUUC | 21 | AUCGUCCAGCAGUAUCGUCUG | 21 |

| novel_miR4740 | 3p | 0 | 0 | 7.3 | 0 | AAAAAAGAUUGAGCCGAAUAA | 21 | ACUCGGCUCAAUCUUUUUUUU | 21 |

| novel_miR5134 | 3p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.7 | UGGAUACCGCCCAACUCUGUU | 21 | CAGAGUUGGGCAGUAUCCAUG | 21 |

| novel_miR5169 | 5p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 88.6 | UAAUCUUCUGGAUAUAUGCUUG | 22 | AGUAUGUUUUUAGAAGAUUAGA | 22 |

| novel_miR5172 | 3p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.8 | GGCGGCAUGGGGAUGUCAAAA | 21 | UUGGCGUCCCCAUGUCCCCC | 20 |

| novel_miR5542 | 5p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28.6 | AUGAAGAGCGCGGGCAGCACA | 21 | UGCUGCCCGCGCUCUUCAUGG | 21 |

| novel_miR5552 | 5p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.0 | CCUCCCGGACCAGAACUUCUU | 21 | GAGGUUUUGGUCAGGGGGACG | 21 |

| novel_miR5598 | 3p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.7 | GAGCACGGGCUUUUCUGGUCA | 21 | ACCGAAGAAGCCUGUGCUCGA | 21 |

| novel_miR5756 | 3p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.2 | UAGAGAGGGAGGGCAGAGGC | 20 | CUCUGCCCUUCCAUCUCUUGG | 21 |

| novel_miR5816 | 5p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.9 | GGUCUGUGUUUGUUUCAAAC | 20 | UUGAGACGAAAACAGACCAA | 20 |

| novel_miR5831 | 3p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.6 | UCGAGAUCCAACGGCUGAGGU | 21 | CUCGGCCGUUGGAUCUUUGAUA | 22 |

TPM, tags per million reads; target for novel_miR692-5p was validated by RLM-5’RACE.

Identification of Differentially Expressed miRNAs

A knowledge of the expression patterns of differentially expressed miRNAs during cold acclimation and vegetative/reproductive transition of winter wheat could provide clues about their potential functions. We first compared the expression patterns of miRNAs in leaves at different growth and developmental stages. All the known miRNAs were clustered by subjecting them to K-means clustering using Euclidian distance measures with Genesis v1.8.1 (Sturn et al., 2002). The results revealed several distinct expression patterns ( Supplemental Figure S1 ). Most miRNAs had similar expression patterns at the four growth stages; the expression level was either high (clusters 7 and 10) or low (clusters 5 and 11). miRNAs in clusters 1 and 8 were mainly expressed at the jointing stage, whereas miRNAs in clusters 13 and 14 were highly expressed at seedling stages, and their expression was extremely suppressed at the jointing stage; miRNAs in cluster 15 were relatively induced at the spring green-up and jointing stages. miRNAs in cluster 16 were induced at the spring green-up stage. miRNAs in cluster 9 were highly expressed in the cold winter and jointing stages.

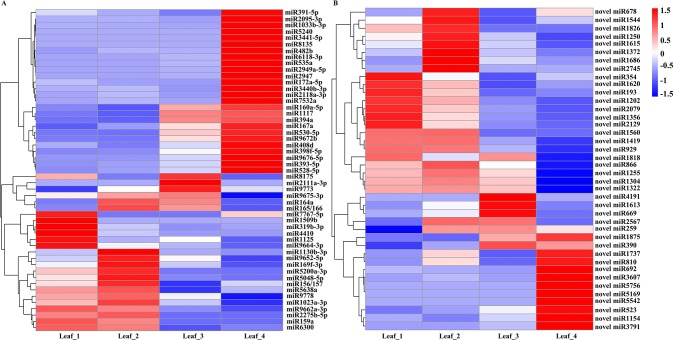

We further selected DEG miRNAs by considering fold changes greater than twofold between any two stages (|log2 fold change| > 1, p-value < 0.01) and with more than 5 TPM in at least one stage. A total of 51 known miRNAs were designated as significantly differentially expressed miRNAs. Generally, 19 miRNAs, including miR159a, miR1125, miR169f-3p, miR319b-3p, miR1130b-3p, miR5200a-3p, and miR9662a-3p, were abundant in at least one of the vegetative stages and had low expression levels at the spring green-up and jointing stages. miR8175, miR2111a-3p, and miR9773 were significantly induced at the spring green-up stage. miR164a, miR165/166, and miR9675-3p were highly expressed at the winter dormancy and spring green-up stages. Six miRNAs (miR160a-5p, miR167a, miR394a, miR530-5p, miR1117, and miR9672b) were induced at the spring green-up stage and exhibited the highest expression level at the inflorescence initiation stage; 20 miRNAs, including miR391-5p, miR172a-5p, miR393-5p, miR398f-5p, miR408d, miR528-5p, miR2095-3p, miR5240, miR2118a-3p, miR7532a, and miR9672b, were highly induced at the jointing stage ( Figure 2A ). Forty novel/putative miRNAs were identified as DEG miRNAs. Ten novel miRNAs (novel_miR354, novel_miR1620, novel_miR193, novel_miR1202, novel_miR2079, novel_miR1356, novel_miR2129, novel_miR1560, novel_miR1419, and novel_miR929) showed higher expression at the three-leaf and winter dormancy stages; five novel miRNAs (novel_miR1818, novel_miR866, novel_miR1255, novel_miR1304, and novel_miR1322) were abundantly expressed at the three-leaf stage, winter dormancy stage, and spring green-up stage, while they were suppressed at the jointing stage. Novel_miR2567 and novel_miR259 were preferentially expressed at the winter dormancy and spring green-up stages; novel_miR4191, novel_miR1613, and novel_miR669 were highly expressed at the spring green-up stage but were suppressed at the jointing stage; novel_miR1875 and novel_miR390 were induced at the spring green-up and jointing stages. Ten novel miRNAs (novel_miR1737, novel_miR810, novel_miR692, novel_miR3607, novel_miR5756, novel_miR5169, novel_miR5542, novel_miR523, novel_miR1154, and novel_miR3791) were exclusively induced in leaves at the jointing stage ( Figure 2B ).

Figure 2.

Heat map of differentially expressed known miRNAs (A) and novel miRNAs (B) in wheat leaves at four different development stages. Each column represents a stage, and each row represents a miRNA. The bar represents the scale of relative expression levels of miRNAs.

Under natural growth conditions, winter wheat is simultaneously exposed to cold weather and short photoperiod conditions in winter and then transits from the vegetative to reproductive growth in the next spring. Comparison of miRNA expression at winter dormancy and the three-leaf stage might reveal miRNAs essential for cold acclimation and/or miRNAs responsive to a short photoperiod. Compared to the three-leaf stage, miR7767-5p, miR1509b, miR319b-3p, miR1125, miR4410, miR9664-3p, and eight novel miRNAs (novel_miR354, novel_miR1620, novel_miR193, novel_miR1202, novel_miR2079, novel_miR1356, novel_miR2129, and novel_miR1818) in leaves were suppressed at the winter dormancy stage, whereas miR164a, miR165/166, miR1130b-3p, miR169f-3p, miR5048-5p, miR5200a-3p, miR9652-5p, and eight novel miRNAs (novel_miR678, novel_miR1544, novel_miR1826, novel_miR1250, novel_miR1615, novel_miR1372, novel_miR1686, and novel_miR2745) were significantly induced in winter and were suppressed at the spring green-up stage ( Figure 2 ). These data specify the potential regulatory function of miRNAs in modulating the growth and development of wheat at the winter dormancy stage.

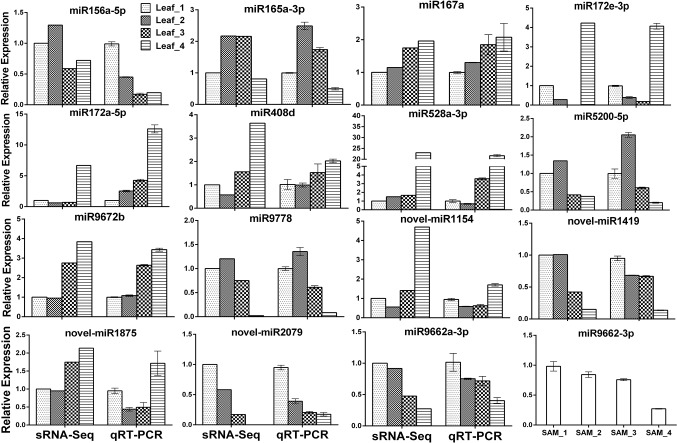

To validate the expression profiles obtained by sRNA-Seq, the RNA samples were first polyadenylated and then reverse-transcribed to cDNA. Eighteen DEG miRNAs were randomly selected for verification by qRT-PCR; three of them failed due to multiple amplification products. The expression patterns of the remaining 15 miRNAs detected by qRT-PCR were consistent or partially consistent with those determined by deep sequencing, although the fold change in expression varied between the sRNA-Seq and qRT-PCR results ( Figure 3 ). Previous studies have shown that miR156 is highly expressed in juvenile plants and is suppressed in adult plants. Compared with the three-leaf stage, the expression of miR156a-5p at the spring green-up stage and jointing stage was relatively low by both sRNA-Seq and qRT-PCR, while the downregulation pattern at the winter dormancy stage detected by qRT-PCR was not observed by sRNA-Seq ( Figure 3 ), probably due to the two mismatches allowed during the annotation of known miRNAs.

Figure 3.

Validation of differentially expressed known and novel miRNAs derived from high-throughput sequencing by qRT-PCR.

Prediction of Potential Target Genes of Known and Novel miRNAs

Identification of miRNA target transcripts is essential to comprehensively understand miRNA-mediated gene regulation. Potential target transcripts for the known and novel miRNAs from wheat were predicted using the PsRobot pipeline (only those with alignment scores between the query miRNA and targets less than 2.5 were considered). Consequently, 4,780 targets for 224 known miRNAs and 1,467 targets for 48 novel miRNAs and 25 putative miRNAs were predicted ( Supplemental Tables S7 – S8 ). A number of targets were found to be TFs, including MYB TFs (target of miR159), homeobox-leucine zipper protein (target of miR164), TF IIIB 90 kDa subunit (target of miR394), and MADS-box TF (target of miR444). Other conserved miRNA targets, including transport inhibitor response 1 (target of miR393), auxin response factor (target of miR160 and miR167), sulfate transporter 2 (target of miR395), laccase (target of miR397), and Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD, target of miR398) were also found ( Supplemental Table S7 ). In addition to the well-documented conserved targets, three VRN3 genes were also predicted as targets of miR5200 ( Supplemental Table S7 ). Many novel targets were also predicted for known and novel miRNAs. Although most of the predicted miRNA–target relationships need to be further validated experimentally, these results strongly suggest that wheat miRNAs are involved in the regulation of various biological processes, like plant architecture, development, and biotic and abiotic stress response.

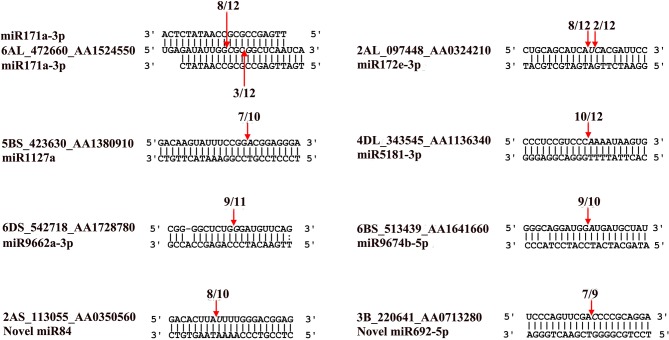

Using the RLM-5′RACE technique, eight genes were verified as bona fide miRNA targets ( Table 3 and Figure 4 ). Among them, two conserved targets for miR171 (TRIAE_CS42_6AL_TGACv1_472660_AA1524550.1, scarecrow-like protein) and miR172 (TRIAE_CS42_2AL_TGACv1_097448_AA0324210.1, AP2-like ethylene-responsive TF) were verified. Four novel targets for Pooideae-specific/wheat-specific miRNAs were validated. miR1127 was found only in wheat and Brachypodium distachyon; we confirmed that this miRNA targets TRIAE_CS42_5BS_TGACv1_423630_AA1380910, a disease resistance protein, RGA1. miR5181, miR9662a-3p, and miRNA9674 were found in wheat, and its progenitor, Aegilops tauschii, TRIAE_CS42_4DL_TGACv1_343545_AA1136340 (a predicted protein), TRIAE_CS42_6DS_TGACv1_542718_AA1728780 (transcription termination factor mTERF15), and TRIAE_CS42_6BS_TGACv1_513439_AA1641660 (protein Rf1, mitochondrial-like) were verified as their corresponding targets. Notably, targets for two novel miRNAs were also verified. TRIAE_CS42_3B_TGACv1_220641_AA0713280 (integrator complex subunit 9) and TRIAE_CS42_2AS_TGACv1_113055_AA0350560 (beta-galactoside alpha-2, 3-sialyltransferase) were targeted by novel_miR692-5p and novel_miR84, respectively. It is worth noting that no miRNA* was detected for novel_miR84, but its precursor has a perfect fold-back structure ( Supplemental File S2 ).

Table 3.

Validated miRNA target genes and primer sequence.

| miRNA | Target gene ID | Primer sequence (5’–3’) | Target annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| novel_miR692-5p | 3B_220641_AA0713280.1 (Traes_3B_E1131EA03.1) |

Rev1: AACACCAATCTCCGTCCGTC | Integrator complex subunit 9 homolog |

| Rev2: AGTAGAATCGATCGCTACAAC | |||

| novel_miR84 | 2AS_113055_AA0350560.2 (Traes_2AS_6BF19AB61.1) |

Rev1: ACAGACCGTATGCTAGCAATG | Beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase |

| Rev2: ACACTCCTGTGTTCAGCCTC | |||

| tae-miR1127a | 5BS_423630_AA1380910.2 | Rev1: ACTGCACGATATTTGGATGCTTAAC | Putative disease resistance protein RGA1 |

| Rev2: TATTCTTGAGTCCACTGAGAATCC | |||

| tae-miR171a-3p | 6AL_472660_AA1524550.1 (Traes_6DL_26DDCA106.1) |

Rev1: AGTACCACGGCGATGAGCAAG | Scarecrow-like protein 6 |

| Rev2: AGGCGATTTCGTCGAGAAGC | |||

| tae-miR172e-3p | 2AL_097448_AA0324210.1 (Traes_2AL_5BA7E2623.1) |

Rev1: ACCACATCCATCCGTCCTCTC | AP2-like ethylene-responsive TF |

| Rev2: AGTTCCAGTTGAGTTGTGGTG | |||

| tae-miR5181-3p | 4DL_343545_AA1136340.2 (Traes_4DL_9294C72F2.1) |

Rev1: AGCGAGTACACATATACAGGACAG | vulgare mRNA for predicted protein |

| Rev2: TAACAGGAGGCAAAATGCCG | |||

| tae-miR9662a-3p | 6DS_542718_AA1728780.1 (Traes_6DS_F6C7E588F.1) |

Rev1: AGCTCAAGTCACGATCTAGCAG | Transcription termination factor MTERF15 |

| Rev2: TGATCGATGAGCAATGTACACG | |||

| tae-miR9674b-5p | 6BS_513439_AA1641660.1 | Rev1: TTACCTTCTGCAGCCTATGAC | Protein Rf1, mitochondrial-like |

| Rev2: AGCTCTGTCATGAGGTACCCTG |

3B_220641_AA0713280.1 is a short name of TRIAE_CS42_3B_TGACv1_220641_AA0713280.1 in ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/plants/release-37/fasta/triticum_aestivum/; the same abbreviation applies to other target gene IDs. Gene ID in parenthood is the gene ID in ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/plants/release-31/fasta/triticum_aestivum/.

Figure 4.

Validation of known and novel miRNA targets using RLM-5’RACE assay. Arrows indicate the cleavage sites detected by RLM-5’RACE.

Discussion

Winter wheat requires prolonged exposure to cold temperatures for acceleration of flowering. miRNAs play important roles in the growth and development of plants, adjusting to various stress and hormone response (Rogers and Chen, 2013; Yu et al., 2017). To investigate the potential roles of miRNAs during cold acclimation and vegetative/reproductive transition of winter wheat under natural growth conditions, we performed a comprehensive analysis of sRNAs in the wheat leaves at four different growth and development stages. In total, 373 known miRNAs belonging to 289 miRNA families, 55 novel miRNAs, and 27 putative novel miRNAs were identified by high-throughput sequencing. The abundance of conserved miRNAs varied; miR168 was found to be the most abundant conserved miRNA. Other highly expressed miRNAs included miR159, miR167, miR156, miR66, miR167, miR5048, miR5062, miR7757, miR9662, miR9672, and miR9674, in agreement with the results of a previous report (Han et al., 2014). Conserved miRNAs and their corresponding target genes are commonly found in all or most of the plant species (Pokoo et al., 2018). All 23 most conserved miRNAs (miR156/157, miR159, miR160, miR161, miR162, miR164, miR165/166, miR167, miR168, miR169, miR170/171, miR172, miR319, miR390, miR391, miR393, miR394, miR395, miR396, miR397, miR398, miR399, and miR408) in eudicots (Zhang et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013; Meng et al., 2013; Pokoo et al., 2018) and miR444, a monocot-specific miRNA (Sunkar et al., 2008), were identified in this study, suggesting that these highly conserved miRNA families are evolutionarily conserved across all major lineages of plants and play specific functions in a variety of physiological processes in plant species. The number of less conserved and wheat-specific miRNAs is very high; this fact, together with the diverse expression pattern of miRNAs at four different growth and development stages ( Figure 2 , Supplemental Tables S2 , S4 , and S5 ), indicates the wide range of regulatory functions mediated by miRNAs in leaves during wheat growth and development.

MicroRNAs function by regulating target genes via sequence complementary based cleavage or translation repression (Llave et al., 2002; Rogers and Chen, 2013; Yu et al., 2017). Therefore, identification of miRNA target transcripts is essential for comprehensive understanding of miRNA-mediated gene regulation. Bioinformatics analysis predicted 4,780 targets for 224 known miRNAs ( Supplemental Table S7 ) and 1,467 targets for novel and putative novel miRNAs ( Supplemental Table S8 ). A number of conserved target genes were identified, including MYB TFs, homeobox-leucine zipper protein, MADS-box TF, transport inhibitor response 1, auxin response factor, sulfate transporter 2, laccase, and Cu/Zn SOD ( Supplemental Table S7 ). Besides these known targets, a large number of novel targets for known miRNA and novel miRNAs were also predicted ( Supplemental Tables S7 – S8 ). Because not all predicted targets are the real targets, experimental validation is necessary to illustrate the biological function of these miRNAs in wheat. Using RLM-5′RACE, we confirmed eight miRNA target genes. Among these, two genes are conserved targets for miR171 and miR172, respectively; four targets for four Pooideae-specific/wheat-specific miRNAs were validated. miR1172a targets RGA1, a disease resistance protein; miR5181-3p targets a predicted protein; miR9674b-5p targets Rf1; TRIAE_CS42_6DS_TGACv1_542718_AA1728780.1, encoding mTERF15, is a target gene of miR9662a-3p ( Figure 4 ). The mTERF family is comprised of a wide range of proteins localized in mitochondria, which have been shown in in vitro and in vivo studies to have roles in transcription initiation and DNA replication in animals, in addition to transcription termination (Roberti et al., 2009). Plant mTERFs also localize to chloroplast. A previous study showed that mTERF6 is required for maturation of chloroplast tRNAILE in Arabidopsis (Romani et al., 2015). Mutations in mTERFs alter the expression of organellar genes and impair the development of chloroplast and mitochondria. Changes in nuclear gene expression were also observed in mterf plants (Quesada, 2016). Moreover, a recent study revealed that mTERF5 can cause plastid-encoded RNA polymerase (PEP) complex to pause at psbEFLJ (encoding four key subunits of photosystem II) in Arabidopsis, confirming that RNA polymerase transcriptional pausing also occurs in plant organelles (Ding et al., 2019) and indicating the critical role of mTERFs in the growth and development of plants. We found that the expression of miR9662a-3p in leaves was gradually decreased with the growth of wheat plants ( Figure 3 ) and speculate that it might be an important regulator during wheat growth and development. We further checked the expression of miR9662a-3p in shoot apical meristem (SAM) at the same growth stage and found a similar expression pattern in SAM to that in leaves ( Figure 3 ). Further studies are required to determine the potential roles of mTERF15 in wheat. Most importantly, targets for two novel miRNAs were validated in this study; novel_miR692-5p targets an integrator complex subunit 9, and novel_miR84 targets beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase. These results not only prove that they are true miRNAs but also demonstrate that these novel miRNAs are functional in modulating the expression of their target genes at the post-transcriptional level in wheat.

A total of 91 differentially expressed miRNAs were identified. Conserved miR156, miR164a, miR165/166, miR159a, miR169f-3p, and miR319b-3p were highly expressed at the vegetative growth stage, and miR160a-5p, miR167a, miR172a-5p, miR393-5p, miR398f-5p, and miR408d were abundantly expressed at the jointing stage ( Supplemental Table S2 and Figure 3 ). The target genes of the most conserved miRNAs are TFs (Li et al., 2010). It is well known that a TF can regulate the expression of multiple downstream target genes by either activation or suppression; therefore, the different regulation patterns of these conserved miRNAs imply that complicated transcription and post-transcription regulation underlie the growth and development processes in winter wheat. Previous studies have shown that miR156 and miR172 have opposite patterns of temporal regulation in several plant species (Wu and Poethig, 2006; Poethig, 2009; Wu et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2017). In this study, the expression level of miR156a-5p in leaves was low at the spring green-up stage and jointing stage compared with that at the three-leaf stage, while miR172 was expressed at very low levels during the vegetative growth and spring green-up stages, but its expression was increased significantly at the jointing stage ( Figure 3 ), confirming that the regulatory circuit of the miR156/miR172 module is highly conserved among phylogenetically distinct plant species and plays important roles in regulating flowering (Wang and Wang, 2015; Wang et al., 2015). miR156 was reported to be induced by cold stress in Brassica rapa (Zeng et al., 2018), whereas it was downregulated by cold stress in rice (Cui et al., 2015), young spikes of wheat (Song et al., 2017), and Astragalus membranaceus (Abla et al., 2019). Overexpression of rice miR156 in Arabidopsis, pine, and rice resulted in improved cold stress tolerance by increasing cell viability and growth rate under cold stress (Zhou and Tang, 2018). The altered expression of miR156a-5p at the winter dormancy stage indicates that miR156 is not only a flowering regulator but also a cold stress responder in plants.

MicroRNAs have been demonstrated to be involved in the regulation of cold stress in different plant species (Megha et al., 2018). In the present study, the expression of miR319b-3p, miR1125, miR1509, miR4410, miR7767, and miR9664 was highly repressed at the winter dormancy stage compared to their expression at the three-leaf stage ( Figure 2A , Supplemental Table 2 ). In previous studies, it has been reported that miR319 is a cold stress–responsive miRNA, which was shown to be upregulated in Arabidopsis and sugarcane (Sunkar and Zhu, 2004; Thiebaut et al., 2012) but was downregulated by cold stress in rice (Yang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014b). Overexpression of miR319 or RNA interference of its targets (OsPCF5 RNAi and OsPCF8 RNAi) in rice leads to the upregulation of cold-responsive genes and improved cold tolerance (Yang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014b). The downregulation of miR319b-3p at the winter dormancy stage demonstrated the essential role of miR319 in cold acclimation of wheat grown in the field. Compared to the three-leaf stage, the expression of miR164a, miR165/166, miR169f-3p, miR1130b-3p, miR5048-5p, miR5200a-3p, and miR9652-5p was significantly induced in winter ( Figure 2 ). The induction of miR164 and miR169 by cold stress has been reported in Astragalus membranaceus (Abla et al., 2019); miR165 and miR1130 were reported to be induced by cold stress in young wheat spikes (Song et al., 2017). Wheat miR166 was induced at the winter dormancy stage, in agreement with the previous finding that it is a cold-responsive miRNA in Brassica rapa (Zeng et al., 2018).

FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) is a key gene involved in the regulation of flowering time. FT is a mobile florigen, transported from leaves into the phloem and then to SAMs, and initiates phase transition (Corbesier et al., 2007). Wheat FT1 (VRN3) is one of the most important flowering promoters. Expression of VRN3 is activated by vernalization, suppressed in short-day conditions, and induced under long-day conditions (Yan et al., 2006). Recent studies revealed that expression of VRN3 is also directly or indirectly regulated by miRNAs at the post-transcription level. miR5200, a Pooideae-specific miRNA, targets FT orthologs in Brachypodium distachyon. bdi-miR5200 was reported to be abundantly expressed in the leaves of plants grown under short-day conditions but was dramatically suppressed in plants under long-day conditions (Wu et al., 2013). It was reported that wheat miR5200 is under negative control of the light receptor PhyC and also targets VRN3 in wheat (Pearce et al., 2016). We found that wheat miR5200a-3p was highly expressed in leaves under short-day conditions (three-leaf stage and winter dormancy stage), indicating that miR5200 functions in the degradation of VRN3 transcripts and provides another layer of assurance that flowering does not occur in late autumn or transient warm conditions in winter. Low expression level of miR5200a-3p at the spring green-up and jointing stages contributes to the accumulation of VRN3 transcript and protein. TIME OF CAB EXPRESSION 1 (TOC1) is a key component of the plant circadian clock and is closely linked to the CO-FT flowering pathway (Niwa et al., 2007). miR408 is a copper deprivation responsive miRNA and targets plantacyanin and copper-containing protein genes (Li et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011). Wheat TOC1s were confirmed as target genes of miR408; both knockdown of wheat TOC1 and overexpression of miR408 resulted in early heading phenotype (Zhao et al., 2016); further study revealed that miR408-mediated cleavage of TOC1s could activate the expression of wheat VRN3 gene and promoted phase transition (Zhao et al., 2016). sRNA-Seq showed that the expression level of miR408 was relatively low at all four stages, but induction of miR408d at the jointing stage was obvious and was validated by qRT-PCR ( Figure 3 ), confirming previous findings that miR408 is a promoter of wheat flowering.

miRNA159 targets GAMYB TFs. Previous studies in wheat, barley, and rice identified the role of GAMYB in anther development (Murray et al., 2003; Kaneko et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2012b). We found that the expression of wheat miR159a was significantly suppressed at the spring green-up stage and jointing stage ( Figure 2 and Supplemental Table S2 ), which suggests that miR159 is a suppressor of flowering in wheat. This correlates well with a previous finding that elevated expression of miR159 results in delayed flowering in Arabidopsis (Achard et al., 2004). miR2111a-3p, miR8175, and miR9733 were significantly induced in wheat leaves at the spring green-up stage. The induction of miR2111 after cold stress was reported in A. membranaceus (Abla et al., 2019). Auxin efflux carrier and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 13 were predicted as targets of miR2111 ( Supplemental Table S7 ); however, the exact biological function of miR2111 in regulating growth and development in wheat remains unclear.

Several miRNAs, such as miR160a-5p, miR167a, miR172a-5p, miR391-5p, miR394a, miR398f-5p, miR528-5p, and miR530-5p, were highly expressed at the jointing stage. miR528 is a monocot-specific miRNA, which accumulates in old plants of rice and exhibits diurnal rhythms of expression. It promotes flowering in rice under long-day conditions by targeting RED AND FAR-RED INSENSITIVE 2 (OsRFI2) (Yang et al., 2019). In wheat, the expression of miR528-5p was significantly induced at the jointing stage ( Figure 2A ), indicating that miR528-5p is essential for wheat flowering. In a previous study, it was shown that miR167 was abundantly accumulated in floral organs during the early stage of anther development in rice (Fujioka et al., 2008). In this study, miR167a was observed to be constantly induced after the winter season, and its expression reached the highest level at the jointing stage ( Figure 2A , Supplement Table S1 ), indicating that miR167 might function as a promoter of flowering in wheat.

Cu/Zn SODs are target genes of miR398. miR398 is expressed at optimal levels under normal growth conditions and is downregulated by oxidative stress in Arabidopsis (Sunkar et al., 2006). The inverse relationship between miR398 and Cu/Zn SODs has been observed under cold stress in wheat and other plants (Lu et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2014a). Expression of miR398 in wheat leaves was not altered at the winter dormancy stage. Other cold stress–responsive miRNAs, such as miR394, miR396, and miR397 (Megha et al., 2018), did not show significant changes between the three-leaf stage and winter dormancy stage, the main reason for which could be attributed to the fact that winter wheat was grown in the field under natural weather conditions in this study. The temperature was fluctuant and decreased gradually, and the duration of cold weather was very long (cold acclimation), while most cold stress studies were conducted in controlled environments for short periods (cold stress). Moreover, photoperiod is another parameter; the impact of photoperiod on the expression of miRNAs has been confirmed (Wu et al., 2013; Pearce et al., 2016). Most of the studies on cold stress–responsive miRNAs were done under certain photoperiod conditions, while the photoperiod varied at different stages in this study.

Besides these conserved miRNAs, 30 other less conserved known miRNAs and 40 novel miRNAs were found to be differentially expressed in leaves during cold acclimation and vegetative/reproductive transition of winter wheat. Although target genes for most of these miRNAs were predicted, their regulatory role in the growth and development of wheat can only be clarified upon further experimental validation.

Conclusions

We performed a transcriptome-wide identification and characterization of miRNAs from wheat leaves at four different stages of growth and development. A total of 373 known miRNAs belonging to 289 miRNA families and 82 novel miRNAs were identified. Ninety-one miRNAs were found to be differentially expressed at the four stages. The expression of six known and eight novel miRNAs was suppressed at the winter dormancy stage, whereas seven known and eight novel miRNAs were induced at this stage. Twenty known miRNAs and 10 novel miRNAs were significantly induced at the jointing stage. The expression of a number of representative miRNAs was verified by qRT-PCR analysis. Eight miRNA target genes were validated using an RLM-5′RACE assay; these included targets for two novel miRNAs and four Pooideae-specific miRNAs. This study provides valuable information for in-depth understanding of the regulatory mechanism of miRNAs in the growth and phase transition of winter wheat. Further studies are required to decipher how these miRNAs are involved in the growth and development of wheat.

Data Availability

The sequencing data of this study have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (NCBI, GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE125391.

Author Contributions

Y-FL conceived the idea and designed the study. KW, MW, LW, and DZ performed sample collection and RNA extractions. Y-FL, KW, MW, JG, and YZ analyzed the sRNA library data sets. KW, MW, JC, and MZ performed qRT-PCR analyses and miRNA target validation. Y-FL and KW prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31771703) and a stand-up fund from Henan Normal University to Y-FL.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Lifeng Wang, who helped with sample collection and qRT-PCR analyses.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2019.00779/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abla M., Sun H., Li Z., Wei C., Gao F., Zhou Y., et al. (2019). Identification of miRNAs and their response to cold stress in Astragalus membranaceus. Biomolecules 9, 182. 10.3390/biom9050182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard P., Herr A., Baulcombe D. C., Harberd N. P. (2004). Modulation of floral development by a gibberellin-regulated microRNA. Development 131, 3357–3365. 10.1242/dev.01206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akdogan G., Tufekci E. D., Uranbey S., Unver T. (2016). miRNA-based drought regulation in wheat. Funct. Integr. Genomics 16, 221–233. 10.1007/s10142-015-0452-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amasino R. M., Michaels S. D. (2010). The timing of flowering. Plant Physiol. 154, 516–520. 10.1104/pp.110.161653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aukerman M. J., Sakai H. (2003). Regulation of flowering time and floral organ identity by a microRNA and its APETALA2-like target genes. Plant Cell 15, 2730–2741. 10.1105/tpc.016238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell M. J., Meyers B. C. (2018). Revisiting criteria for plant microRNA annotation in the era of big data. Plant Cell 30, 272–284. 10.1105/tpc.17.00851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao W., Kojima K. K., Kohany O. (2015). Repbase update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mobile DNA 6, 11. 10.1186/s13100-015-0041-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazin J., Khan G. A., Combier J. P., Bustos-Sanmamed P., Debernardi J. M., Rodriguez R., et al. (2013). miR396 affects mycorrhization and root meristem activity in the legume Medicago truncatula . Plant J. 74, 920–934. 10.1111/tpj.12178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouché F., Woods D. P., Amasino R. M. (2017). Winter memory throughout the plant kingdom: different paths to flowering. Plant Physiol. 173, 27–35. 10.1104/pp.16.01322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu D., Yu K., Sun S., Xie C., Skogerbo G., Miao R., et al. (2012). NONCODE v3.0: integrative annotation of long noncoding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D210–D215. 10.1093/nar/gkr1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P. P., Lowe T. M. (2008). GtRNAdb: a database of transfer RNA genes detected in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D93–D97. 10.1093/nar/gkn787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. Y., Yang Y., Ran L. P., Dong Z. D., Zhang E. J., Yu X. R., et al. (2017). Novel insights into miRNA regulation of storage protein biosynthesis during wheat caryopsis development under drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1707. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L., Vincent C., Jang S., Fornara F., Fan Q., Searle I., et al. (2007). FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis . Science 316, 1030–1033. 10.1126/science.1141752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui N., Sun X. L., Sun M. Z., Jia B. W., Duanmu H. Z., Lv D. K., et al. (2015). Overexpression of OsmiR156k leads to reduced tolerance to cold stress in rice (Oryza sativa). Mol. Breed. 35, 214. 10.1007/s11032-015-0402-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danyluk J., Kane N. A., Breton G., Limin A. E., Fowler D. B., Sarhan F. (2003). TaVRT-1, a putative transcription factor associated with vegetative to reproductive transition in cereals. Plant Physiol. 132, 1849–1860. 10.1104/pp.103.023523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paola D., Zuluaga D. L., Sonnante G. (2016). The miRNAome of durum wheat: isolation and characterisation of conserved and novel microRNAs and their target genes. BMC Genomics 17, 505. 10.1186/s12864-016-2838-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S., Zhang Y., Hu Z., Huang X., Zhang B., Lu Q., et al. (2019). mTERF5 acts as a transcriptional pausing factor to positively regulate transcription of chloroplast psbEFLJ. Mol. Plant. 12, 1259–1277. 10.1016/j.molp.2019.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fileccia V., Bertolini E., Ruisi P., Giambalvo D., Frenda A. S., Cannarozzi G., et al. (2017). Identification and characterization of durum wheat microRNAs in leaf and root tissues. Funct. Integr. Genomics 17, 583–598. 10.1007/s10142-017-0551-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C., Sunkar R., Zhou C., Shen H., Zhang J. Y., Matts J., et al. (2012). Overexpression of miR156 in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) results in various morphological alterations and leads to improved biomass production. Plant Biotechnol. J. 10, 443–452. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00677.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X. Y., Li C. H., Zhao Y. K., Shi Z. L., Guo J. K., He M. Q. (2016). Analysis of high-yield, stability and adaptation of new wheat variety ‘Shimai22’. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 32, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka T., Kaneko F., Kazama T., Suwabe K., Suzuki G., Makino A., et al. (2008). Identification of small RNAs in late developmental stage of rice anthers. Genes Genet. Syst. 83, 281–284. 10.1266/ggs.83.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R., Wang Y., Gruber M. Y., Hannoufa A. (2017). miR156/SPL10 modulates lateral root development, branching and leaf morphology in Arabidopsis by silencing AGAMOUS-LIKE 79. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 2226. 10.3389/fpls.2017.02226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H., Wang Q., Wei L., Liang Y., Dai J., Xia G., et al. (2018). Small RNA and degradome sequencing used to elucidate the basis of tolerance to salinity and alkalinity in wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 18, 195. 10.1186/s12870-018-1415-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han R., Jian C., Lv J., Yan Y., Chi Q., Li Z., et al. (2014). Identification and characterization of microRNAs in the flag leaf and developing seed of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Genomics 15, 289. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadeeswaran G., Nimmakayala P., Zheng Y., Gowdu K., Reddy U. K., Sunkar R. (2012). Characterization of the small RNA component of leaves and fruits from four different cucurbit species. BMC Genomics 13, 329. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M., Inukai Y., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Itoh H., Izawa T., Kobayashi Y., et al. (2004). Loss-of-function mutations of the rice GAMYB gene impair alpha-amylase expression in aleurone and flower development. Plant Cell 16, 33–44. 10.1105/tpc.017327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H., Doyle M. R., Sung S., Amasino R. M. (2009). Vernalization: winter and the timing of flowering in plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 25, 277–299. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Byrns B., Badawi M. A., Diallo A. B., Danyluk J., Sarhan F., et al. (2018). Transcriptomic insights into phenological development and cold tolerance of wheat grown in the field. Plant Physiol. 176, 2376–2394. 10.1104/pp.17.01311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. Q., Yu C., Li Y. R., Lam T. W., Yiu S. M., Kristiansen K., et al. (2009). SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics 25, 1966–1967. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Ma L., Geng Y., Hao C., Chen X., Zhang X. (2015). Small RNA and degradome sequencing reveal complex roles of miRNAs and their targets in developing wheat grains. PLoS One 10, e0139658. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. F., Zheng Y., Addo-Quaye C., Zhang L., Saini A., Jagadeeswaran G., et al. (2010). Transcriptome-wide identification of microRNA targets in rice. Plant J. 62, 742–759. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04187.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. F., Zheng Y., Jagadeeswaran G., Sunkar R. (2013). Characterization of small RNAs and their target genes in wheat seedlings using sequencing-based approaches. Plant Sci., 203–204, 17–24. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llave C., Xie Z., Kasschau K. D., Carrington J. C. (2002). Cleavage of Scarecrow-like mRNA targets directed by a class of Arabidopsis miRNA. Science 297, 2053–2056. 10.1126/science.1076311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. Z., Feng Z., Bian L. Y., Xie H., Liang J. S. (2010). miR398 regulation in rice of the responses to abiotic and biotic stresses depends on CSD1 and CSD2 expression. Funct. Plant Biol. 38, 44. 10.1071/FP10178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megha S., Basu U., Kav N. N. V. (2018). Regulation of low temperature stress in plants by microRNAs. Plant Cell Environ. 41, 1–15. 10.1111/pce.12956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F. R., Liu H., Wang K. T., Liu L. L., Wang S. H., Zhao Y. H., et al. (2013). Development-associated microRNAs in grains of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 13, 140. 10.1186/1471-2229-13-140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray F., Kalla R., Jacobsen J., Gubler F. (2003). A role for HvGAMYB in another development. Plant J. 33, 481–491. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01641.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki E. P., Burge S. W., Bateman A., Daub J., Eberhardt R. Y., Eddy S. R., et al. (2015). Rfam 12.0: updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D130–D137. 10.1093/nar/gku1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa Y., Ito S., Nakamichi N., Mizoguchi T., Niinuma K., Yamashino T., et al. (2007). Genetic linkages of the circadian clock–associated genes, TOC1, CCA1 and LHY, in the photoperiodic control of flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 925–937. 10.1093/pcp/pcm067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver S. N., Deng W., Casao M. C., Trevaskis B. (2013). Low temperatures induce rapid changes in chromatin state and transcript levels of the cereal Vernalization1 gene. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 2413–2422. 10.1093/jxb/ert095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce S., Kippes N., Chen A., Debernardi J. M., Dubcovsky J. (2016). RNA-seq studies using wheat PHYTOCHROME B and PHYTOCHROME C mutants reveal shared and specific functions in the regulation of flowering and shade-avoidance pathways. BMC Plant Biol. 16, 141. 10.1186/s12870-016-0831-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poethig R. S. (2009). Small RNAs and developmental timing in plants. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19, 374–378. 10.1016/j.gde.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokoo R., Ren S., Wang Q., Motes C. M., Hernandez T. D., Ahmadi S., et al. (2018). Genotype- and tissue-specific miRNA profiles and their targets in three alfalfa (Medicago sativa L) genotypes. BMC Genomics 19, 913. 10.1186/s12864-018-5280-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada V. (2016). The roles of mitochondrial transcription termination factors (MTERFs) in plants. Physiol. Plant. 157, 389. 10.1111/ppl.12416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberti M., Polosa P. L., Bruni F., Manzari C., Deceglie S., Gadaleta M. N., et al. (2009). The MTERF family proteins: mitochondrial transcription regulators and beyond. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 303–311. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R. E., Mecchia M. A., Debernardi J. M., Schommer C., Weigel D., Palatnik J. F. (2010). Control of cell proliferation in Arabidopsis thaliana by microRNA miR396. Development 137, 103–112. 10.1242/dev.043067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K., Chen X. (2013). Biogenesis, turnover, and mode of action of plant microRNAs. Plant Cell 25, 2383–2399. 10.1105/tpc.113.113159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani I., Manavski N., Morosetti A., Tadini L., Maier S., Kühn K., et al. (2015). A member of the Arabidopsis mitochondrial transcription termination factor family is required for maturation of chloroplast transfer RNAIle(GAU). Plant Physiol. 169, 627. 10.1104/pp.15.00964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S., Grande A. V., Bujdoso N., Saedler H., Huijser P. (2008). The microRNA regulated SBP-box genes SPL9 and SPL15 control shoot maturation in Arabidopsis . Plant Mol. Biol. 67, 183–195. 10.1007/s11103-008-9310-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G., Zhang R., Zhang S., Li Y., Gao J., Han X., et al. (2017). Response of microRNAs to cold treatment in the young spikes of common wheat. BMC Genomics 18, 212. 10.1186/s12864-017-3556-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturn A., Quackenbush J., Trajanoski Z. (2002). Genesis: cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics 18, 207–208. 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkar R., Kapoor A., Zhu J. K. (2006). Posttranscriptional induction of two Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase genes in Arabidopsis is mediated by downregulation of miR398 and important for oxidative stress tolerance. Plant Cell 18, 2051–2065. 10.1105/tpc.106.041673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkar R., Zhou X., Zheng Y., Zhang W., Zhu J. K. (2008). Identification of novel and candidate miRNAs in rice by high throughput sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 8, 25. 10.1186/1471-2229-8-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkar R., Zhu J. K. (2004). Novel and stress-regulated microRNAs and other small RNAs from Arabidopsis . Plant Cell 16, 2001–2019. 10.1105/tpc.104.022830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiebaut F., Rojas C. A., Almeida K. L., Grativol C., Domiciano G. C., Lamb C. R., et al. (2012). Regulation of miR319 during cold stress in sugarcane. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 502–512. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomashow M. F. (1999). Plant Cold Acclimation: freezing tolerance genes and regulatory mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 571–599. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomashow M. F. (2010). Molecular basis of plant cold acclimation: insights gained from studying the CBF cold response pathway. Plant Physiol. 154, 571–577. 10.1104/pp.110.161794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashegyi I., Marozsan-Toth Z., Galiba G., Dobrev P. I., Vankova R., Toth B. (2013). Cold response of dedifferentiated barley cells at the gene expression, hormone composition, and freezing tolerance levels: studies on callus cultures. Mol. Biotechnol. 54, 337–349. 10.1007/s12033-012-9569-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Sun Y. F., Song N., Wei J. P., Wang X. J., Feng H., et al. (2014. a). MicroRNAs involving in cold, wounding and salt stresses in Triticum aestivum L. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 80, 90–96. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Wang H. (2015). The miR156/SPL module, a regulatory hub and versatile toolbox, gears up crops for enhanced agronomic traits. Mol. Plant 8, 677–688. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. W., Czech B., Weigel D. (2009). miR156-regulated SPL transcription factors define an endogenous flowering pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana . Cell 138, 738–749. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Feng Z., Wang X., Wang X., Zhang X. (2010). DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 26, 136–138. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Zhao J., Zhang M., Li W., Luo K., Lu Z., et al. (2015). Identification and characterization of microRNA expression in Ginkgo biloba L. leaves. Genet. Genomes 11, 76. 10.1007/s11295-015-0897-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.-T., Sun X.-L., Hoshino Y., Yu Y., Jia B., Sun Z.-W., et al. (2014. b). MicroRNA319 positively regulates cold tolerance by targeting OsPCF6 and OsTCP21 in rice (Oryza sativa L.). PLoS One 9, e91357. 10.1371/journal.pone.0091357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Wu K., Yuan Q., Liu X., Liu Z., Lin X., et al. (2012. a). Control of grain size, shape and quality by OsSPL16 in rice. Nat. Genet. 44, 950–954. 10.1038/ng.2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Shi C., Yang T., Zhao L., Chen J., Zhang N., et al. (2018). High-throughput sequencing revealed that microRNAs were involved in the development of superior and inferior grains in bread wheat. Sci. Rep. 8, 13854. 10.1038/s41598-018-31870-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Sun F. L., Cao H., Peng H. R., Ni Z. F., Sun Q. X., et al. (2012. b). TamiR159 directed wheat TaGAMYB cleavage and its involvement in anther development and heat response. PLoS One 7, e48445. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei B., Cai T., Zhang R., Li A., Huo N., Li S., et al. (2009). Novel microRNAs uncovered by deep sequencing of small RNA transcriptomes in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and Brachypodium distachyon (L.) Beauv. Funct. Integr. Genomics 9, 499–511. 10.1007/s10142-009-0128-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Park M. Y., Conway S. R., Wang J. W., Weigel D., Poethig R. S. (2009). The sequential action of miR156 and miR172 regulates developmental timing in Arabidopsis . Cell 138, 750–759. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Poethig R. S. (2006). Temporal regulation of shoot development in Arabidopsis thaliana by miR156 and its target SPL3. Development 133, 3539–3547. 10.1242/dev.02521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Liu D., Wu J., Zhang R., Qin Z., Liu D., et al. (2013). Regulation of flowering locus T by a microRNA in Brachypodium distachyon. Plant Cell 25, 4363–4377. 10.1105/tpc.113.118620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J., Xu S., Li C., Xu Y., Xing L., Niu Y., et al. (2014). O-GlcNAc–mediated interaction between VER2 and TaGRP2 elicits TaVRN1 mRNA accumulation during vernalization in winter wheat. Nat. Commun. 5, 4572. 10.1038/ncomms5572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Xin M., Wang Y., Yao Y., Xie C., Peng H., Ni Z., et al. (2010). Diverse set of microRNAs are responsive to powdery mildew infection and heat stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 10, 123. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Chong K. (2018). Remembering winter through vernalisation. Nat. Plants 4, 997–1009. 10.1038/s41477-018-0301-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Fu D., Li C., Blechl A., Tranquilli G., Bonafede M., et al. (2006). The wheat and barley vernalization gene VRN3 is an orthologue of FT. Proc. Nat. Acad.Sci. 103, 19581–19586. 10.1073/pnas.0607142103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Loukoianov A., Tranquilli G., Helguera M., Fahima T., Dubcovsky J. (2003). Positional cloning of the wheat vernalization gene VRN1. Proc. Nat. Acad.Sci. 100, 6263–6268. 10.1073/pnas.0937399100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Li D., Mao D., Liu X. U. E., Ji C., Li X., et al. (2013). Overexpression of microRNA319 impacts leaf morphogenesis and leads to enhanced cold tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Environ. 36, 2207–2218. 10.1111/pce.12130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R., Li P., Mei H., Wang D., Sun J., Yang C., et al. (2019). Fine-tuning of MiR528 accumulation modulates flowering time in rice. Mol. Plant. 12, 1103–1113. 10.1016/j.molp.2019.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Guo G., Ni Z., Sunkar R., Du J., Zhu J. K., et al. (2007). Cloning and characterization of microRNAs from wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Genome Biol. 8, R96. 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Jia T., Chen X. (2017). The ‘how’ and ‘where’ of plant microRNAs. New Phytol. 216, 1002–1017. 10.1111/nph.14834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Xu Y., Jiang J., Zhang F., Ma L., Wu D., et al. (2018). Identification of cold stress responsive microRNAs in two winter turnip rape (Brassica rapa L.) by high throughput sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 18, 52. 10.1186/s12870-018-1242-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zheng Y., Jagadeeswaran G., Li Y., Gowdu K., Sunkar R. (2011). Identification and temporal expression analysis of conserved and novel microRNAs in Sorghum. Genomics 98, 460–468. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. C., Yu Y., Wang C. Y., Li Z. Y., Liu Q., Xu J., et al. (2013). Overexpression of microRNA OsmiR397 improves rice yield by increasing grain size and promoting panicle branching. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 848–852. 10.1038/nbt.2646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Hong P., Wu J., Chen X., Ye X., Pan Y., et al. (2016). The tae-miR408–mediated control of TaTOC1 genes transcription is required for the regulation of heading time in wheat. Plant Physiol. 170, 1578–1594. 10.1104/pp.15.01216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Li T., Xu Z., Wai C. M., Chen K., Zhang X., et al. (2016). Identification of microRNAs, phasiRNAs and their targets in pineapple. Trop. Plant Biol. 9, 176–186. 10.1007/s12042-016-9173-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Cheng Y., Yin M., Yang E., Gong W., Liu C., et al. (2015). Identification of novel miRNAs and miRNA expression profiling in wheat hybrid necrosis. PLoS One 10, e0117507. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Tang W. (2018). MicroRNA156 amplifies transcription factor–associated cold stress tolerance in plant cells. Mol. Gen. Genomics 294, 379–393. 10.1007/s00438-018-1516-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q. H., Helliwell C. A. (2011). Regulation of flowering time and floral patterning by miR172. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 487–495. 10.1093/jxb/erq295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]