1. Introduction

Genetic generalized epilepsy (GGE) accounts for nearly a third of all epilepsy types, and perampanel has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an adjunctive treatment for primary generalized tonic–clonic seizures (PGTS) in patients > 12 years and older in over forty countries worldwide [1,2]. Its efficacy and tolerability were evaluated in three phase III multi-centered, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (Trials 304, 305, and 306) in patients with partial onset seizures (POS) despite receiving one to three AEDs [3,4,5,6]. Their findings demonstrated significant reduction in seizure frequency of partial-onset seizures, secondarily generalized seizures, and complex partial with secondarily generalized seizures, when compared with the placebo group (median percentage reduction from baseline per 28 days). Other clinical studies in real-life settings reported similar improvements in clinical outcomes [7]. While there are increasingly more trials being conducted in North America and Europe [8,9,10,11], this, to our knowledge, is the first retrospective study from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, evaluating the use of perampanel as monotherapy and adjunctive treatment in the routine clinical care of patients with GGE.

2. Methods

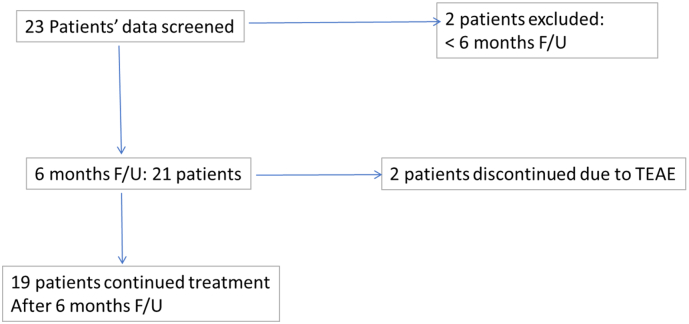

The study was conducted at a private neurology clinic in Abu Dhabi, UAE and was approved by an internal Institutional Review Board at the American Center for Psychiatry and Neurology, in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). Twenty-one patients (females and males aged between 13 and 47), diagnosed with GGE according to the 2017 International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification of epileptic seizures [12] and the 2017 ILAE classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes [13] were included in the study. They were included if they had a diagnosis of GGE during their clinical assessment by their attending neurologist (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification) [ICD-10-CM code G40.309] and received perampanel as monotherapy or adjunctively with other AEDs between March 2018 and August 2018. Disposition chart of all 21 enrolled subjects included in the study is displayed in Fig. 1. All enrolled patients were started on PER treatment both as adjunctive and monotherapy between March 2016 and March 2018. Nineteen of the patients were taking an average of three AEDs prior to starting PER treatment, while the remaining two were put on PER monotherapy from the start of treatment.

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition of all 21 enrolled subjects at 6-month follow-up.

Demographic and clinical data were collected from patients' clinical records upon obtaining their informed consent. These included age, sex, nationality, ethnicity, primary diagnosis, secondary diagnosis, previous AEDs, current concomitant AEDs, seizure type, seizure frequency, perampanel dose at titration, current perampanel dose, current perampanel treatment status, dose reduction, and reasons for dose reduction. We relied on patients' diaries to collect data on seizure frequency, checked at each clinic visit every four to six weeks; this is routinely scheduled for all patients with epilepsy. Adverse events were recorded on patients' medical archives at every clinic visit using open-ended questions. For dose titration, patients were initially put on a daily dose of 2 mg at night time, increased by 2 mg every two weeks until a 6 mg dose was maintained and well-tolerated. Further increments/decrements were made according to the neurologist's clinical judgment and based on patient response and tolerability. For safety assessments, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE), psychiatry-related adverse events, and reasons for discontinuation, if any, were recorded. Proportion of patients who were either previously or concomitantly on enzyme-inducing AEDs were also recorded. Table 1, Table 2 show patient demographics and epilepsy-specific details, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics.

| Demographics (full analysis set) | |

|---|---|

| N | 21 |

| Mean age, y (SD) | 27.48 (9.72) |

| Female, n (%) | 12 (57.1%) |

| Nationality/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Emirati (Arab) | 11 (52.4%) |

| Syrian (Arab) | 3 (14.3%) |

| Sudanese (Arab) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Egyptian (Arab) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Yemeni (Arab) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Palestinian (Arab) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Omani (Arab) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Indian (Asian) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Age of onset, y (SD) | 12.19 (7.16) |

Table 2.

Seizure-specific details.

| Seizure-specific data | |

|---|---|

| Seizure type, n (%) | |

| Tonic–clonic | 21 (100%) |

| Myoclonic | 16 (76.2%) |

| Absence | 2 (9.5%) |

| Atonic | 1 (4.3%) |

| Number of previous AED trials (discontinued prior to starting PER) | 14 (66.7%) |

| 1 | 6 (28.6%) |

| 2 | 5 (23.8%) |

| 3 | 5 (23.8%) |

| 4 | 1 (4.8%) |

| 5 | 2 (9.5%) |

| Reasons for previous AED(s) discontinuation | |

| Inadequate efficacy | 10 (47.6%) |

| Poor tolerability | 4 (19.1%) |

| Number of concomitant baseline AEDs | 17 (80.9%) |

| 1 | 6 (26.6%) |

| 2 | 8 (38.1%) |

| 3 | 3 (14.3%) |

| Patients on concomitant enzyme-inducing AEDs | 3 (14.3%) |

| Patients who had dose reduction due to TEAE | 3 (14.3%) |

| Reasons for dose reduction | |

| Dizziness | 1 (4.8%) |

| Agitation | 1 (4.8%) |

| Aggression | 1 (4.8%) |

| Increased hand tremors | 1 (4.8%) |

| Patients currently on perampanel monotherapy | 7 (33.3%) |

| Current AEDs | |

| Perampanel monotherapy | 7 (33.3%) |

| Adjunctive perampanel | 12 (57.1%) |

| Others (discontinued perampanel) | 2 (9.52%) |

| Patients who had ≥ 50% response rate | 19 (90.5%) |

| Patients who achieved seizure freedom | 11 (52.4%) |

The primary efficacy endpoint was the percent decrease in seizure frequency. Seizure frequency was assessed by looking at the proportion of patients with a reduction in seizure frequency by at least 50%. The secondary efficacy endpoint was determined by the proportion of patients remaining on perampanel primary or conversion monotherapy at six months from baseline.

3. Results

There were 21 patients (12F, 9M), with a mean age of 27.48 years (13–47, SD ± 9.72). The mean age of seizure onset was 12.19. Two patients started on perampanel as initial monotherapy and 19 others were on it as an add-on, with an average number of prior AED trials at 2.47 (1–5, SD 1.81). The average perampanel dose was 7.90. Two patients were excluded from the final analysis because follow-up was lost before reaching six months. Eight patients (38.1%) achieved a ≥ 50% reduction in seizure frequency at six months from baseline, while 11 patients (52.4%) achieved seizure freedom at the same interval of time. Nineteen patients (90.5%) remained on perampanel treatment beyond the six month follow-up from baseline, while two patients (9.5%) discontinued PER treatment due to treatment-induced adverse events; namely, dizziness and somnolence. Treatment-induced adverse events (see Table 3) were reported in 11 patients (52.4%), with the most common symptom being dizziness (4M, 2F). Out of those, nine patients (42.9%) continued treatment beyond six months. Five patients (23.8%) were reported as experiencing psychiatric-related adverse events (see Table 4), with irritability and depressive symptoms as the most common. However, none discontinued treatment. Four patients had comorbid diagnosis of major depressive disorder, but only two of them experienced psychiatric-related adverse events (irritability and worsening of depressive symptoms). Out of the four with psychiatric comorbidity, only one discontinued treatment but due to experiencing somnolence. Co-administered AEDs for these patients include Levetiracetam, Topiramate, Valproic Acid, Phenytoin, and Clonazepam. Three out of four were offered treatment for their psychiatric disorders but declined, while one was started on Escitalopram for the same. Three patients were concomitantly taking enzyme-inducing AEDs, namely, Topiramate, Phenytoin, and Phenobarbitone. One patient (taking Topiramate) discontinued treatment due to somnolence, and the other two experienced depressive symptoms but continued treatment. Seven patients (33.3%) were on perampanel monotherapy at the time of analyzing the current data, while the rest (57.1%) continued adjunctive treatment with the number of baseline AEDs reduced on average by 1.33 at the six month interval.

Table 3.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE).

| TEAE | N (%) | Onset of TEAE | Relation to dose escalation | Action taken | Outcome at last FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dizziness | 6 (28.6%) | Between week 2 and week 4 | Probably related | No action taken (3 cases) Dose reduced (2 cases) Drug withdrawn (1 case) |

Resolved Resolved Resolved |

| Somnolence | 1 (4.8%) | Week 4 | Probably related | Drug withdrawn | Resolved |

| Headache | 1 (4.8%) | Between week 4 and week 6 | Probably related | No action taken | Resolved |

| Blurred vision | 1 (4.8%) | Week 8 | Possibly related | No action taken | Resolved |

| Decreased libido | 1 (4.8%) | Week 8 | Possibly related | No action taken | Resolved (improved over several weeks of follow-up) |

| Weight gain | 1 (4.8%) | Week 8 | Probably related | No action taken | Resolved (improved over several weeks of FU) |

| Snoring | 1 (4.8%) | Week 8 | Possibly related | No action taken | Resolved (improved over several weeks of FU) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (4.8%) | Between week 4 and week 6 | Possibly related | No action taken | Resolved (improved over several weeks of FU) |

| Depressive symptoms | 3 (14.3%) | Week 4 | Probably related | No action taken | Resolved |

| Irritability | 2 (9.5%) | Week 4 | Probably related | No action taken | Resolved |

| Anxiety | 1 (4.8%) | Week 4 | Probably related | No action taken | Resolved |

| Agitation | 1 (4.8%) | Week 6 | Probably related | Dose reduced | Resolved |

| Aggression | 1 (4.8%) | Week 6 | Probably related | Dose reduced | Resolved |

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics related to PER.

| Exposure to adjunctive therapy | Syndrome classificationa | Type of seizures | Seizure frequency before PER | Seizure frequency after PER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | GTCA | Tonic–clonic | Once every eight weeks | Zero |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Once every two months Three times per week |

Zero |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Once per month Once per week |

Zero |

| Yes | JME | Myoclonic | Four times daily | Zero |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic Absence Atonic |

Twice per week Four times daily Once daily Once per week |

Once per week Once per day Once every three weeks Once per month |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Once every three months Four times per day |

Zero Once per day |

| Yes | JME | Myoclonic | Twice per day | Once every two weeks |

| No | JME | Tonic–clonic | Once per month | Zero |

| Yes | JME | Myoclonic | Four times per day | Zero |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Once per month Two–three times per day |

Zero Zero |

| No | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Once every two months Three times per week |

Zero Zero |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Three–four per week Three–four per day |

Once per week Twice per week |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Once per week Three times per week |

Once every two months Once every two weeks |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Once every two weeks Once daily |

Once every six–eight weeks Once every seven–ten days |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Once every three–four months Two–three times per week |

Zero Zero |

| Yes | JAE | Tonic–clonic Absence |

Once per week Once daily |

Zero Zero |

| Yes | GTCA | Tonic–clonic | Once per month | Once every two–three months |

| Yes | GTCA | Tonic–clonic | Twice per month | Once every two–three months |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Once per month Once or twice per week |

Discontinued due to AE |

| Yes | JTCA | Tonic–clonic | Twice per month | Zero |

| Yes | JME | Tonic–clonic Myoclonic |

Two–three times per month Three–four times per week |

Discontinued due to AE |

GTCA — generalized tonic–clonic seizures alone; JME — juvenile myoclonic epilepsy; JAE — juvenile absence epilepsy.

4. Discussion

This retrospective study evaluated archives of clinical data on 21 patients with genetic generalized epilepsy who received perampanel treatment as both monotherapy and adjunctive therapy. We evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of perampanel with a minimum of six month follow-up and observed a 38.1% seizure reduction and 52.4% seizure freedom rate in our cohort. There was also a 90.5% response rate where patients continued treatment beyond six months from baseline. On average, the 19 patients who continued with adjunctive treatment had 1.33 of their baseline AEDs discontinued with the prospect of achieving perampanel monotherapy. Comparing the results to the three phase-III randomized regulatory trials which evaluated perampanel treatment for partial seizures (studies 304, 305, and 306), seizure reduction rates at 8 mg/day dose ranged between 33.3% and 37.6%, similar to the observed 38% responder rate in this cohort [3,4,5]. However, their seizure freedom rate was much lower and ranged between 2.2% and 4.8% at a dose of 8 mg/day.

The most common TEAE among our cohort was dizziness, causing one out of the six patients with the experience to discontinue treatment. The three regulatory trials also reported dizziness, irritability, and aggression as the most common adverse effects causing at least 1% of their studied population to discontinue treatment [3,4,5]. A retrospective multicenter study [7] from Spain also found dizziness as the most common TEAE in their studied cohort. Moreover, a sub analysis of the phase III trials which looked at perampanel efficacy and safety by gender found female subjects experienced dizziness and headache more frequently than males [11]. In our cohort, four out of the six patients who experienced dizziness were female among whom one patient also experienced headache. Our study also found five patients (23.8%) having had experienced psychiatry-related adverse events. Irritability and depressive symptoms were the most common, although none of the reported patients discontinued treatment because of them. Safety data from the three phase-III trials show that irritability and aggression were dose-related occurrences although the investigators did not confirm causality [14]. It is important to mention that four of the patients in our cohort had pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses and two of them reported worsening of their symptoms, which could be a predicting factor of the PRAE associated with perampanel treatment.

Other real-world studies such as the one by Villanueva and colleagues [15] have reported similar results while also looking at different seizure types in GGE. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) was the most common syndrome in their subjects at 40%, compared with 76% in the current cohort. The seizure-freedom rate was similar at 59% across all seizure types compared with 52.4% in the current study. Fifty percent of the patients with JME in the current cohort achieved seizure freedom whereas their study reported 65% among the same group. This study [15] also reported dizziness as one of the most common treatment-emergent adverse events. Relatedly, a randomized, multicenter, double-blind study [8] on patients with tonic–clonic seizures in GGE had a comparable rate of seizure freedom at 30.9%. Moreover, the same study had enrolled subjects who were also using between one and three AEDs, and reported dizziness as one of the most common treatment-emergent adverse events. The percentage of patients with generalized tonic–clonic seizure type (81%) receiving perampanel treatment was comparable to the current cohort (86%). Unlike the current cohort, however, this study [8] had 11.1% of patients discontinuing treatment due to psychiatric-related adverse events, including severe cases of abnormal behavior, aggression, anxiety and insomnia, mood swings, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. That said, in the current cohort, a 23-year-old male patient who experienced behavioral issues (agitation and aggression) had his dose temporarily reduced to 4 mg from 6 mg/day. Some studies have reported higher rates of occurrence in psychiatric-related adverse events when administering perampanel as compared with any other antiepileptic drugs [16,17]. The occurrence of both treatment-emergent and psychiatric-related adverse events suggests that patients should be monitored carefully for clinical response and tolerability, and dosing should be individualized as part of the routine clinical care. None of the patients in this cohort reported experiencing suicidal or homicidal ideation threats.

This study has some limitations: the sample, while being small, is also made up of a heterogeneous group and data was collected retrospectively, potentially creating selection bias of results. It would have also been preferred if archived data beyond six months was considered to draw more meaningful conclusions. Abu Dhabi being one of the most developed cities in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), generalizability of the results to other less affluent areas in the region is restricted where quality of life, access to, and quality of treatment may be limited. Nevertheless, we anticipate that it provides additional insight into the use of perampanel as both monotherapy and adjunctive treatment for GGE.

5. Conclusion

Our study provides supplemental information towards the decision to approve perampanel as monotherapy, based on similar findings from retrospective and non-interventional studies in various locations in Europe and Russia [7,15]. Our findings, although based on a relatively smaller sample size, are representative of a population from the Middle East and North Africa region and suggest that perampanel is well-tolerated in patients with GGE. For non-compliant patients, monotherapy may ease the burden of having to take multiple AEDs daily, but slow-titration is always preferred to lessen the occurrence of TEAEs including PRAEs.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by an internal Institutional Review Board at the American Center for Psychiatry and Neurology, in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). Informed consent was solicited from patients after explaining the voluntary nature of the study and guaranteeing confidentiality and anonymity.

Funding source

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Caraballo R.H., Bernardina D.B. Idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;111:579–589. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52891-9.00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faulkner M.A. Spotlight on perampanel in the management of seizures: design, development, and an update on place in therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:2921–2930. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S122404. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.French J.A., Krauss G.L., Biton V. Adjunctive perampanel for refractory partial-onset seizures: randomized phase III study 304. Neurology. 2012;79:589–596. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182635735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French J.A., Krauss G.L., Steinhoff B.J. Evaluation of adjunctive perampanel in patients with refractory partial-onset seizures: results of randomized global phase III study 305. Epilepsia. 2013;54:117–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krauss G.I., Serratosa J.M., Villaneuva V. Adjunctive perampanel for refractory partial-onset seizures: randomized phase III study 306. Neurology. 2012;78(18):1408–1415. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318254473a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinhoff B.J., Ben-Menachem E., Ryvlin P. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive perampanel for the treatment of refractory partial seizures: a pooled analysis of three phase III studies. Epilepsia. 2013;54:1481–1489. doi: 10.1111/epi.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gil-Nagel A., Burd S., Toledo M., Sander J.W. A retrospective, multicenter study of perampanel given as monotherapy in routine clinical care in people with epilepsy. Seizure. 2018;54:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.French J.A., Krauss G.L., Wechsler R.T. Perampanel for tonic–clonic seizures in idiopathic generalized epilepsy: a randomized trial. American Academy of Neurology. 2015;85:950–957. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maurousset A., Limousin N., Praline J. Adjunctive perampanel in refractory epilepsy: experience at tertiary epilepsy care center in Tours. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;61:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swiderska N., Tan H.J., Rajai A. Effectiveness and tolerability of perampanel in children, adolescents and young adults with refractory epilepsy: a UK national multicenter study. Seizure. 2017;52:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vazquez B., Yang H., Williams B. Perampanel efficacy and safety by gender: sub-analysis of phase III randomized clinical studies in subjects with partial seizures. Epilepsia. 2015:1–5. doi: 10.1111/epi.13019. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ILAE classification of the epilepsies. International League Against Epilepsy; 2017. Available from: https://www.ilae.org/guidelines/definition-and-classification/ilae-classification-of-the-epilepsies-2017. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- 13.Operational classification of seizure types. International League Against Epilepsy; 2017. Available from: https://www.ilae.org/guidelines/definition-and-classification/operational-classification-2017. Accessed January 24, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ettinger A.B., LoPresti A., Yang H. Psychiatric and behavioral adverse events in randomized clinical studies of the noncompetitive AMPA receptor antagonist perampanel. Epilepsia. 2015;56(8):1252–1263. doi: 10.1111/epi.13054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villanueva V., Montoya J., Castillo A. Perampanel in routine clinical use in idiopathic generalized epilepsy: the 12-month GENERAL study. Epilepsia. 2018;00:1–13. doi: 10.1111/epi.14522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber B., Schmid G. A two-year retrospective evaluation of perampanel in patients with highly drug-resistant epilepsy and cognitive impairment. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;66:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snoeijen-Schouwenaars F.M., van Ool J.S., Tan I.Y. Evaluation of perampanel in patients with intellectual disability and epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;66:64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]