Abstract

Two experiments were conducted to investigate the effects of phytonutrients (PN) on growth performance, antioxidant status, intestinal morphology, and nutrient utilization of birds fed low energy diets. In Exp. 1, a total of 1,440 one-day-old Ross 308 male broiler chickens were randomly divided into 3 treatment groups, with 16 replicates per treatment (48 pens; 30 birds per pen). Birds in treatment 1 were fed diets with normal energy content (NE). Birds in treatment 2 were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed (LE). Birds in treatment 3 were assigned to LE diet supplemented with PN (LE + PN). Results indicated that LE diet increased feed conversion ratio (FCR) compared with NE from d 1 to 38, while LE + PN diet prevented this response (P = 0.02). At d 26, birds in the LE + PN group had the highest ileal and jejunal villus height to crypt depth (VH:CD) ratio. At d 39, PN supplementation improved ileal and jejunal VH:CD ratio, compared with LE group. Moreover, birds fed PN diets received a better economic profit. In Exp. 2, 360 one-day-old Ross 308 male broiler chickens were used in a metabolism study. The treatments used in Exp. 2 were the same as those in Exp.1, with 4 replicates (pens) and 30 birds in each replicate. Dietary apparent metabolism energy (AME), energy and protein digestibility were determined between 21 and 28 d of age. Results showed that chickens fed LE + PN diet tended to have greater AME (P = 0.02) and nitrogen-corrected apparent metabolism energy (AMEn) (P = 0.03) than birds fed LE diets. It was concluded that LE + PN showed a potential advantage to improve feed conversion and gut health of broilers, as well as economic profits.

Keywords: Phytonutrient, Growth performance, Antioxidation, Intestinal morphology, Energy utilization, Broilers, Low energy

1. Introduction

Phytonutrients (PN), as secondary plant metabolites, have been shown to affect animal growth performance (Windisch et al., 2008, Wallace et al., 2010), immune status (Amerah et al., 2011, Karadas et al., 2013), and also have antioxidative or antiviral effects (Sökmen et al., 2004). Karadas et al. (2014) found that a combination of PN improved growth and feed efficiency of broilers. Pirgozliev et al. (2015) stated that supplementary PN improved body weight (BW) and feed efficiency of birds, but did not affect dietary metabolism energy (ME). It is proposed that although dietary PN did not affect dietary ME, they caused an improvement in the utilization of energy for growth (Bravo et al., 2014).

In China, dietary energy represents up to 70% of the feed cost for broilers, and experiments investigating the available energy concentration of poultry feedstuffs are using the metabolism energy system. Therefore, it is important to study the change in dietary ME in response to PN, especially the response to low energy diets (Bravo et al., 2011). The objective of the current study was to evaluate the effects of a blend of PN on broiler growth performance, antioxidative status, intestinal morphology, and apparent metabolism energy (AME) of broilers diets.

2. Materials and methods

The study was approved by the Animal Care and Experiment Committee of New Hope Liuhe Corporation.

2.1. Experiment one

The objective of this experiment was to evaluate effects of a mixture of PN on growth performance, antioxidative status and intestinal tract morphology. A total of 1,440 one-day-old Ross 308 male broilers were obtained from a commercial hatchery, individually weighed, and assigned to 48 pens of 2 m × 1.5 m in size, with 30 chicks in each pen. The chickens were reared on litter in floor pens. The litter was obtained from a commercial chick ranch and had been used to raise broilers for a batch. The brooding temperature was maintained at 33 °C for the first day and was gradually decreased by 2 °C per week until 21 °C and maintained at that level thereafter. During the whole experimental period, chickens had free access to feed and water. Birds were reared on the following lighting program: 22 h light (22 L):2 h dark (2 D) for the first 3 d, 19 L:5 D from d 4 to d 7, 16 L:8 D from d 8 to 40. Birds were vaccinated for Newcastle disease and infectious bronchitis via injection at d 7, and via water at d 21. The infectious bursal disease vaccination was given via water at d 14.

Birds in treatment 1 were fed normal energy diets (NE Group). In treatment 2, energy levels were reduced by 60 kcal/kg relative to NE (LE Group). Birds in treatment 3 were fed LE diets supplemented with a PN blend (LE + PN Group). Each treatment has 16 replicates of 30 chicks. The broilers were fed on a 4-phase feeding program (Table 1). With the exception of decreased energy, all diets were formulated to provide similar nutrients according to the requirement of broilers by NRC (1994). The active ingredients of PN product used in this experiment included 5% carvacrol, 3% cinnamaldehyde and 2% capsaicin.

Table 1.

Ingredients and nutrient content of experimental diets, as-fed basis (%).1

| Item | d 1 to 14 |

d 15 to 22 |

d 23 to 30 |

d 31 to 38 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE | LE | NE | LE | NE | LE | NE | LE | |

| Ingredients | ||||||||

| Corn | 45.90 | 47.42 | 47.66 | 49.11 | 46.28 | 47.71 | 45.07 | 46.51 |

| Soybean meal | 28.60 | 28.30 | 24.10 | 23.90 | 19.80 | 19.60 | 15.40 | 15.20 |

| Wheat | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 15.00 | 15.00 |

| Peanut meal | 4.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 |

| Barley | 3.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Corn DDGS | 2.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Soybean oil | 1.45 | 0.22 | 1.51 | 0.28 | 2.70 | 1.47 | 3.79 | 2.55 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 1.98 | 1.98 | 1.62 | 1.61 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 0.87 | 0.86 |

| Limestone | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.13 | 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.06 | 1.06 |

| L-lysine·H2SO4 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.64 |

| DL-methionine | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| L-threonine | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Salt | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Premix2 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Nutrient level3 | ||||||||

| Crude protein | 22.01 | 21.99 | 21.00 | 21.02 | 19.99 | 20.00 | 18.99 | 19.00 |

| Calcium | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| Total phosphorus | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| Lysine | 1.37 | 1.36 | 1.31 | 1.31 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.11 | 1.11 |

| Threonine | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| Methionine + Cystine | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| AMEn, kcal/kg | 2,600 | 2,540 | 2,650 | 2,589 | 2,750 | 2,690 | 2,850 | 2,790 |

DDGS = distillers dried grains with solubles; AMEn = nitrogen-corrected apparent metabolizable energy.

NE, birds were fed diets with normal energy content. LE, birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed.

The premix provides following per kilogram diet: 12,000 IU vitamin A, 2,500 IU vitamin D3, 40 mg vitamin E, 5 mg vitamin K3, 6 mg vitamin B1, 10 mg vitamin B2, 15 mg vitamin B6, 0.02 mg vitamin B12, 50 mg nicotinic acid, 15 mg D-pantothenic acid, 0.2 mg biotin, 60 mg Fe, 10 mg Cu, 80 mg Mn, 80 mg Zn, 0.1 mg I, 0.3 mg Se.

Nutrient levels were calculated values.

Body weights and feed intake by pen were recorded on 14, 22, 30 and 38 d of age, and the mortality was recorded daily. Europe production efficiency factor (EPEF) was calculated as follows: EPEF = ADG × [(100%−Mortality rate)/FCR]/10, where ADG is the average daily gain.

At 26 and 39 d of age, 12 chickens around average BW were selected from each treatment, weighed and killed by exsanguinations after CO2 stunning. After the abdominal incision, a middle section of the duodenum, jejunum and ileum were collected. The contents of each gut section were gently flushed with a saline solution (NaCl, 0.9%), and the intestinal section sample (2 cm in length) was fixed in 10% formalin solution for further analysis. The tissue samples were processed, embedded, sectioned, stained with hematoxylin-eosin and mounted, then intestinal slides were examined by optical microscopy, and images were captured by a camera attached to the microscope and transferred to an image analyzer software. Villus height (VH) in micrometer was measured from the tip of the villus to the villus crypt junction. Crypt depth (CD) in micrometer was defined as the depth of the invagination between adjacent villi. Then VH:CD ratio was calculated.

At 39 d of age, 12 chickens around average BW were selected from each treatment, then blood samples were aseptically collected from the wing vein into vacutainers and centrifuged at 3,600 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The serum was collected and stored at −20 °C for future analysis. The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), and malondialdehyde (MDA) content in the serum were measured using SOD, T-AOC and MDA assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), and then analyzed by an automated spectrophotometric analyzer (Shimadzu, Model UVmini-1240, Tokyo, Japan).

Feed cost for weight gain and profit of chicks were calculated at the end of experiment. Feed cost (CNY/kg) = Sum of feed cost for each phase/BW gain for the whole experiment; Profit (CNY/bird) = Price of live bird − Feed cost − Production cost − Labor cost − Cost of 1-day-old chick.

2.2. Experiment two

A total of 360 one-day-old Ross 308 male broiler chickens were allocated to 3 treatment groups of 4 replicates (pens), with 30 chickens in each pen from 1 to 21 d of age. The diets were allocated to pens in a randomized complete block design and feed was offered to chickens ad libitum. Treatment assignments, diets and birds husbandry were the same as that described in Exp. 1.

At 21 d of age, 6 chickens from each pen with a nearest average BW were selected, and transferred to metabolism cages following the same randomization and dietary treatments as in the floor pen phase. The adaptation period for cage housing was 3 d. Feed and water were provided ad libitum. The chickens selected were kept in the cages for approximately 72 h until 27 d of age, and total excreta samples were collected each day. Feed intake for the same period was recorded for the determination of dietary energy and protein digestibility coefficients.

The experimental diets and the excreta were analyzed for combustion energy content to determine dietary ME. Combustion energy was determined using a bomb calorimeter (IKA C5003 Calorimeter System, Calorimeter, C5003, IKA Co., IL). The crude protein (CP) values were obtained as N × 6.25 (AOAC, 2016). Dietary ME was calculated as follows: AME (kcal/kg DM) = (Energy intake−Energy output)/Feed intake, in which Energy intake is the energy (kcal/kg) intake of the chickens from d 24 to 27, and Energy output is the energy (kcal/kg) output of the chickens from d 24 to 27 (Bravo et al., 2011).

2.3. Statistical analyses

Data in Exp. 1 and 2 were analyzed as a completely randomized block design using the GLM procedure of SPSS 16.0. The data were analyzed with One-way ANOVA. For growth performance, the experimental unit was the floor pen, and for dietary ME, the experimental unit was the metabolism cage. If the test showed significant differences (P < 0.05), ranked scores were separated by the least significant difference procedure. Results in tables were reported as means ± SD.

3. Results

3.1. Growth performance

Table 2 shows the results on growth performance of the chickens (Exp. 1). From 1 to 14 d of age, birds in LE and the LE + PN groups had lower ADG, EPEF, and greater FCR than chickens fed normal energy diet (P < 0.05). From d 23 to 30 and d 31 to 38 periods, birds in LE + PN group has numerically the lowest FCR, though the difference was not significant (P > 0.05). In general, the low energy diet caused greater FCR from d 1 to 38 (P < 0.05). When adding PN in low energy diet, birds had the similar FCR to that of the normal energy group (P > 0.05). Birds fed normal energy diet had greater d 14 and 22 BW than those of LE and the LE + PN groups (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Effects of phytonutrients on growth performance of broilers in Exp. 1.1

| Item | NE | LE | LE + PN2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 14 d | ||||

| Initial BW, g | 42.3 ± 0.3 | 42.3 ± 0.2 | 42.3 ± 0.3 | 0.90 |

| ADG, g/d | 30.6 ± 0.7a | 29.8 ± 0.8b | 29.5 ± 0.6b | <0.01 |

| ADFI, g/d | 37.7 ± 0.7 | 37.5 ± 0.8 | 37.3 ± 0.8 | 0.28 |

| FCR | 1.232 ± 0.02b | 1.260 ± 0.02a | 1.264 ± 0.03a | <0.01 |

| EPEF | 243 ± 10.2a | 231 ± 12.7b | 229 ± 11.5b | 0.002 |

| Survival rate, % | 98.1 ± 2.2 | 97.6 ± 2.9 | 98.1 ± 2.5 | 0.88 |

| 14-d BW, g | 470 ± 9.8a | 459 ± 11.9b | 455 ± 8.8b | <0.01 |

| 15 to 22 d | ||||

| ADG, g/d | 74.5 ± 2.7a | 72.4 ± 2.8b | 72.0 ± 1.7b | 0.01 |

| ADFI, g/d | 108.7 ± 3.5 | 108.3 ± 2.9 | 106.6 ± 2.0 | 0.10 |

| FCR | 1.458 ± 0.03b | 1.497 ± 0.03a | 1.481 ± 0.02a | <0.01 |

| EPEF | 507 ± 21.7a | 481 ± 30.4b | 484 ± 18.8b | 0.01 |

| Survival rate, % | 99.2 ± 1.5 | 99.4 ± 1.4 | 99.6 ± 1.1 | 0.69 |

| 22-d BW, g | 1,068 ± 25.9a | 1,041 ± 30.8b | 1,034 ± 14.3b | <0.01 |

| 23 to 30 d | ||||

| ADG, g/d | 100.8 ± 4.1 | 100.4 ± 4.3 | 98.7 ± 3.6 | 0.30 |

| ADFI, g/d | 155.3 ± 5.2 | 155.3 ± 5.4 | 153.1 ± 3.3 | 0.30 |

| FCR | 1.541 ± 0.04 | 1.548 ± 0.03 | 1.552 ± 0.03 | 0.70 |

| EPEF | 652 ± 38 | 643 ± 41.7 | 635 ± 35.6 | 0.46 |

| Survival rate, % | 99.6 ± 1.1 | 99.0 ± 1.6 | 99.8 ± 0.9 | 0.16 |

| 30-d BW, g | 1,875 ± 52.4a | 1,847 ± 61.1ab | 1,828 ± 36.1b | 0.04 |

| 31 to 38 d | ||||

| ADG, g/d | 103.1 ± 6.3 | 103.3 ± 6.9 | 104.0 ± 6.7 | 0.92 |

| ADFI, g/d | 201.5 ± 7.6 | 203.9 ± 9.1 | 201.6 ± 8.0 | 0.65 |

| FCR | 1.957 ± 0.06 | 1.979 ± 0.09 | 1.941 ± 0.06 | 0.33 |

| EPEF | 526 ± 47.9 | 517 ± 59.0 | 535 ± 50.6 | 0.63 |

| Survival rate, % | 99.6 ± 1.2 | 98.6 ± 2.1 | 99.6 ± 1.2 | 0.13 |

| 38-d BW, g | 2,707 ± 83.7 | 2,678 ± 93.8 | 2,675 ± 64.6 | 0.48 |

| 1 to 38 d | ||||

| ADG, g/d | 70.1 ± 2.2 | 69.4 ± 2.5 | 69.3 ± 1.7 | 0.47 |

| ADFI, g/d | 111.9 ± 3.1 | 112.2 ± 3.3 | 110.8 ± 2.1 | 0.36 |

| FCR | 1.596 ± 0.02b | 1.619 ± 0.03a | 1.600 ± 0.03b | 0.02 |

| EPEF | 424 ± 22.9 | 406 ± 26.2 | 420 ± 22.4 | 0.08 |

| Survival rate, % | 96.5 ± 3.6 | 94.6 ± 3.6 | 97.0 ± 3.2 | 0.13 |

BW = body weight, ADG = average daily gain, ADFI = average daily feed intake, FCR = feed conversion ratio, EPEF = Europe production efficiency factor.

a, b Within a row, numbers with different superscripts differ statistically at P < 0.05.

NE, birds were fed diets with normal energy content. LE, birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed. n = 16 replications.

The active ingredients of PN products in this experiment included 5% carvacrol, 3% cinnamaldehyde and 2% capsaicin.

3.2. Serum anti-oxidation and intestinal morphology

The effects of PN on serum antioxidative status are showed in Table 3 (Exp. 1). There was no significant difference on serum antioxidation among the three groups. Malondialdehyde value in low energy group was lower than the other 2 groups (P = 0.09).

Table 3.

Effects of phytonutrients on serum antioxidant indicators of broilers in Exp. 1.1

| Item | NE | LE | LE + PN | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA, nmol/mL | 1.59 ± 0.16 | 1.46 ± 0.45 | 1.93 ± 0.28 | 0.09 |

| SOD, U/mL | 50.43 ± 5.23 | 50.07 ± 4.06 | 49.95 ± 3.97 | 0.98 |

| T-AOC, U/mL | 19.27 ± 5.64 | 22.22 ± 3.14 | 19.53 ± 4.67 | 0.38 |

MDA = malondialdehyde, SOD = superoxide dismutase, T-AOC = total antioxidant capacity.

NE, birds were fed diets with normal energy content. LE, birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed. n = 12 broilers.

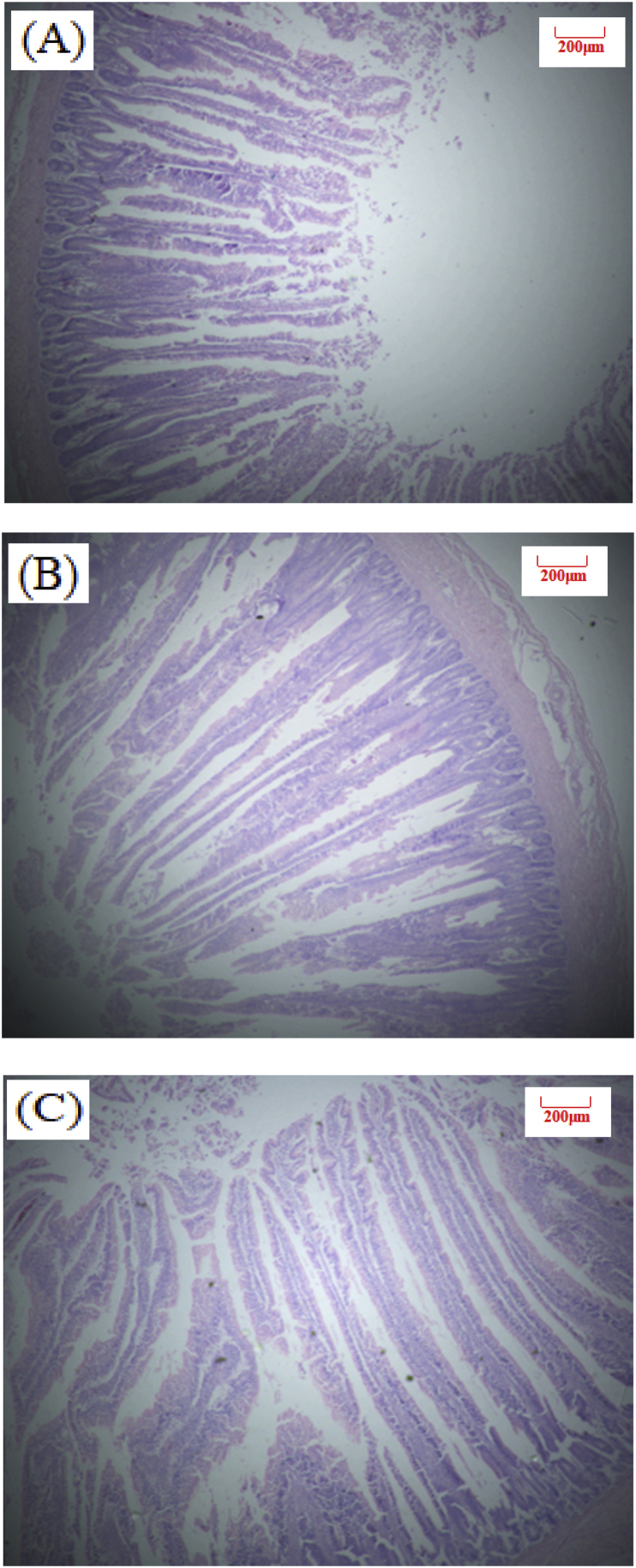

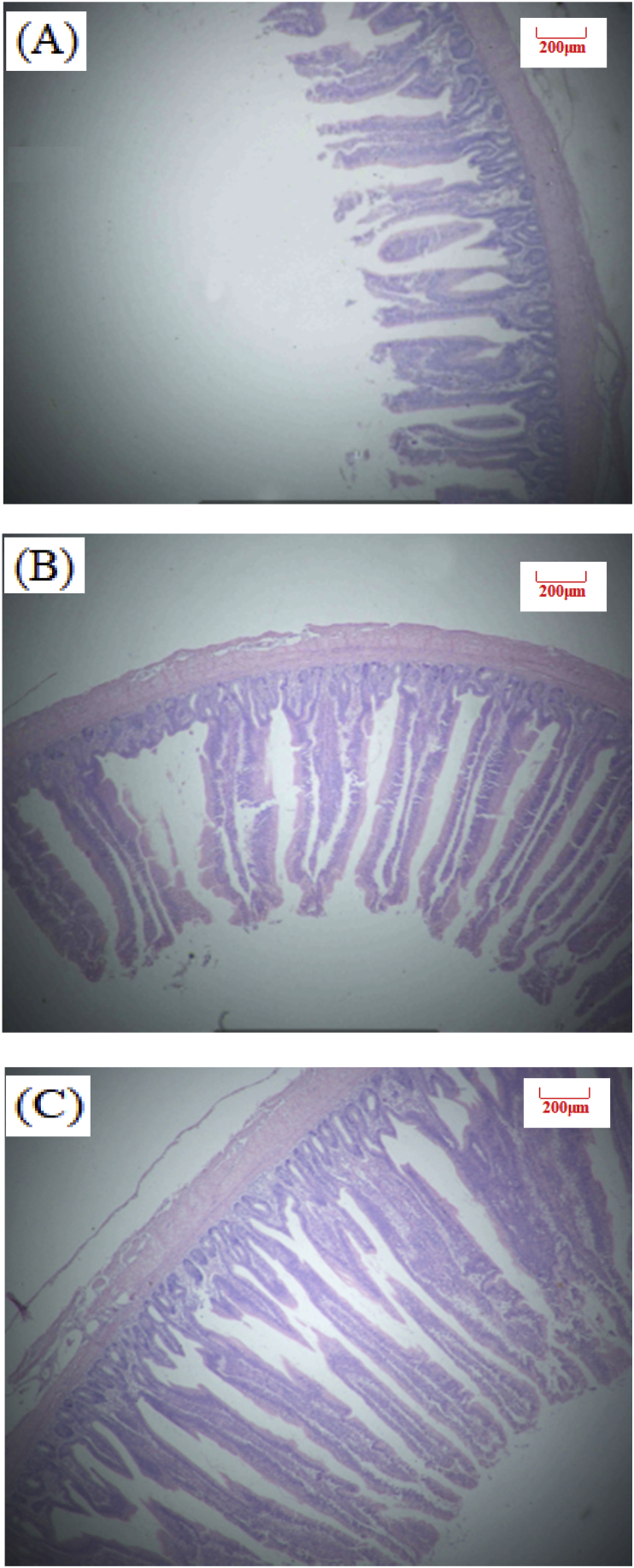

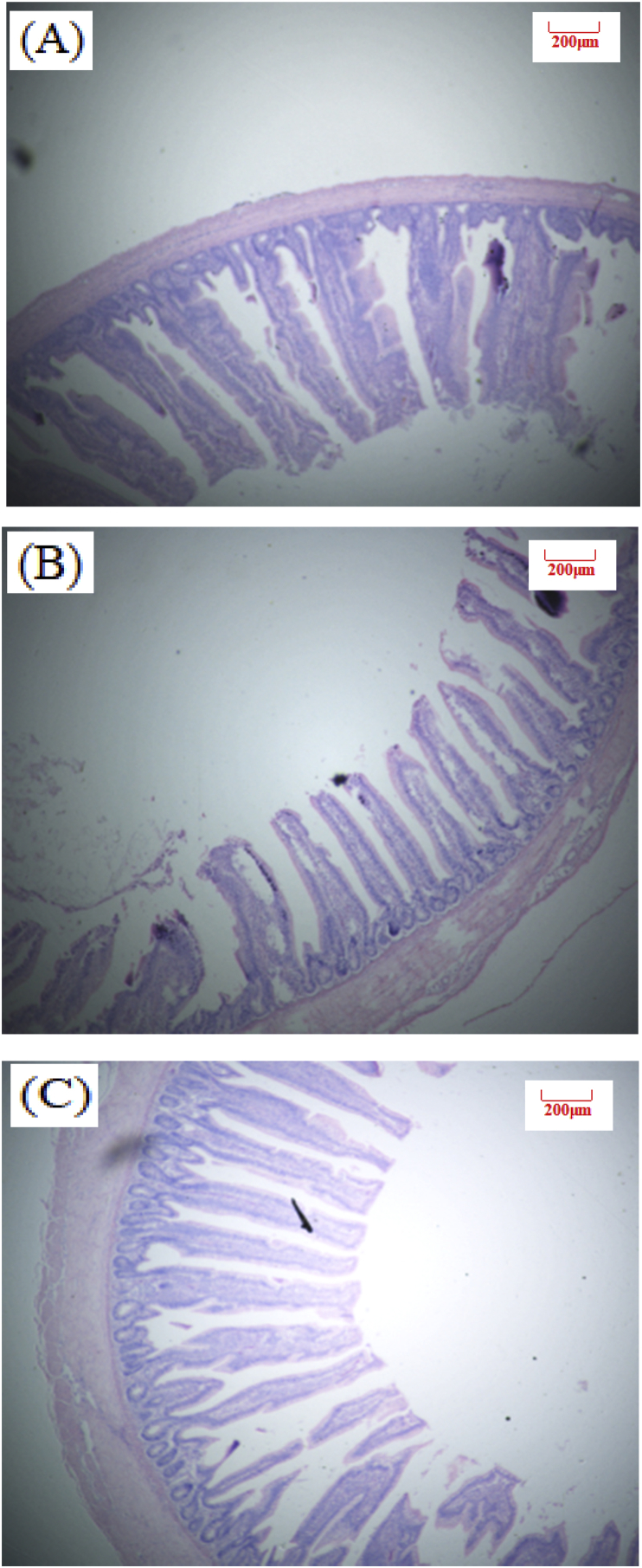

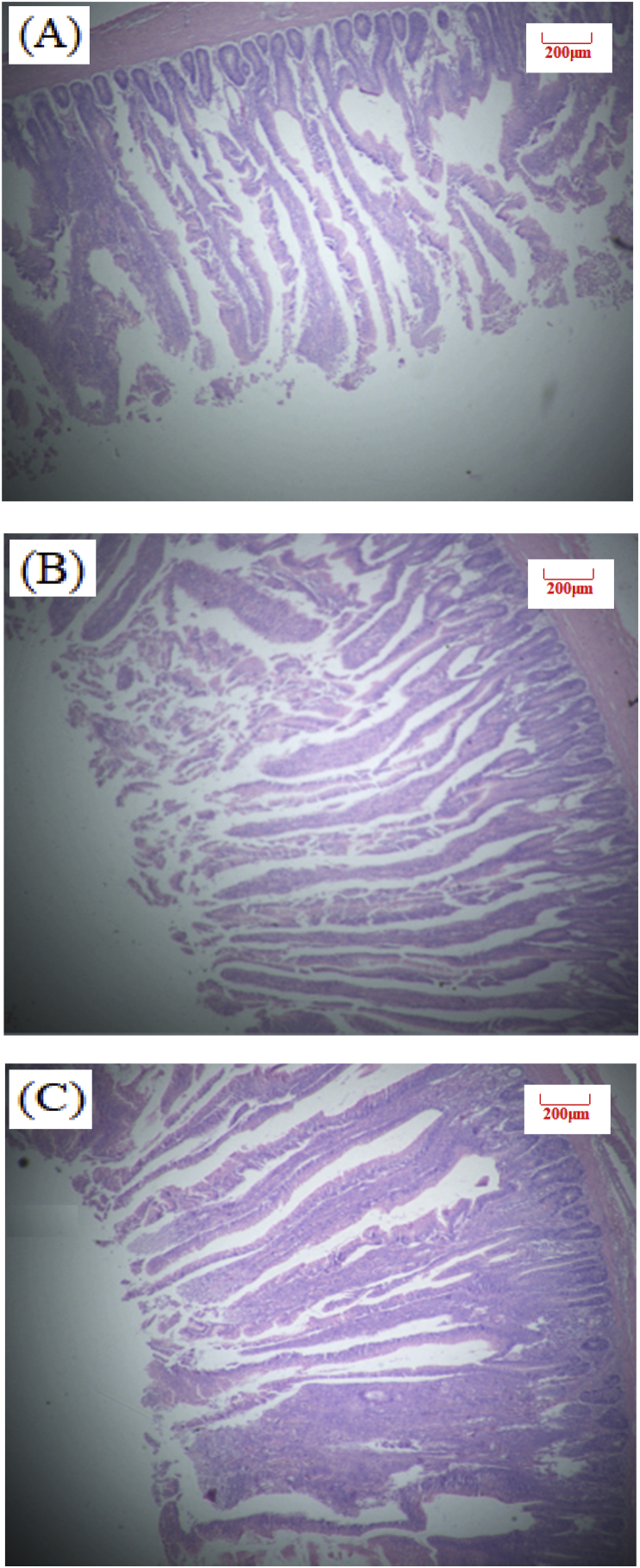

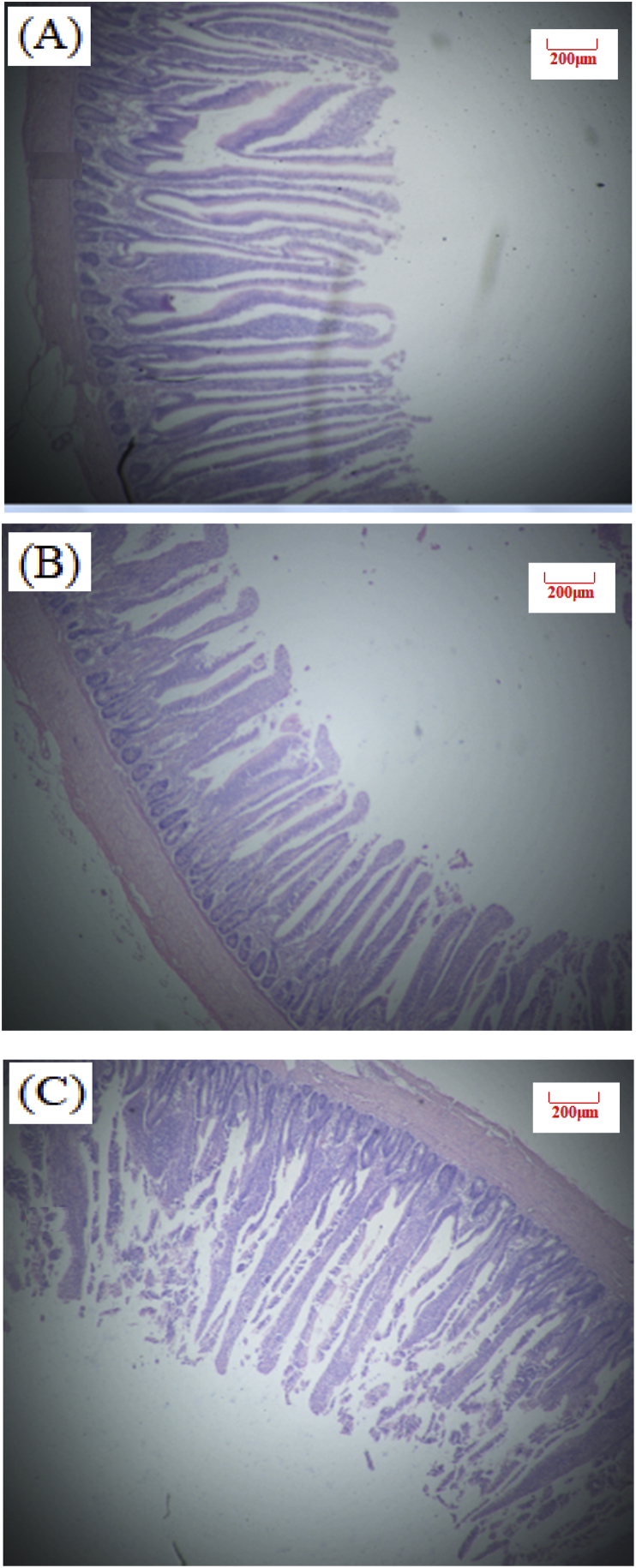

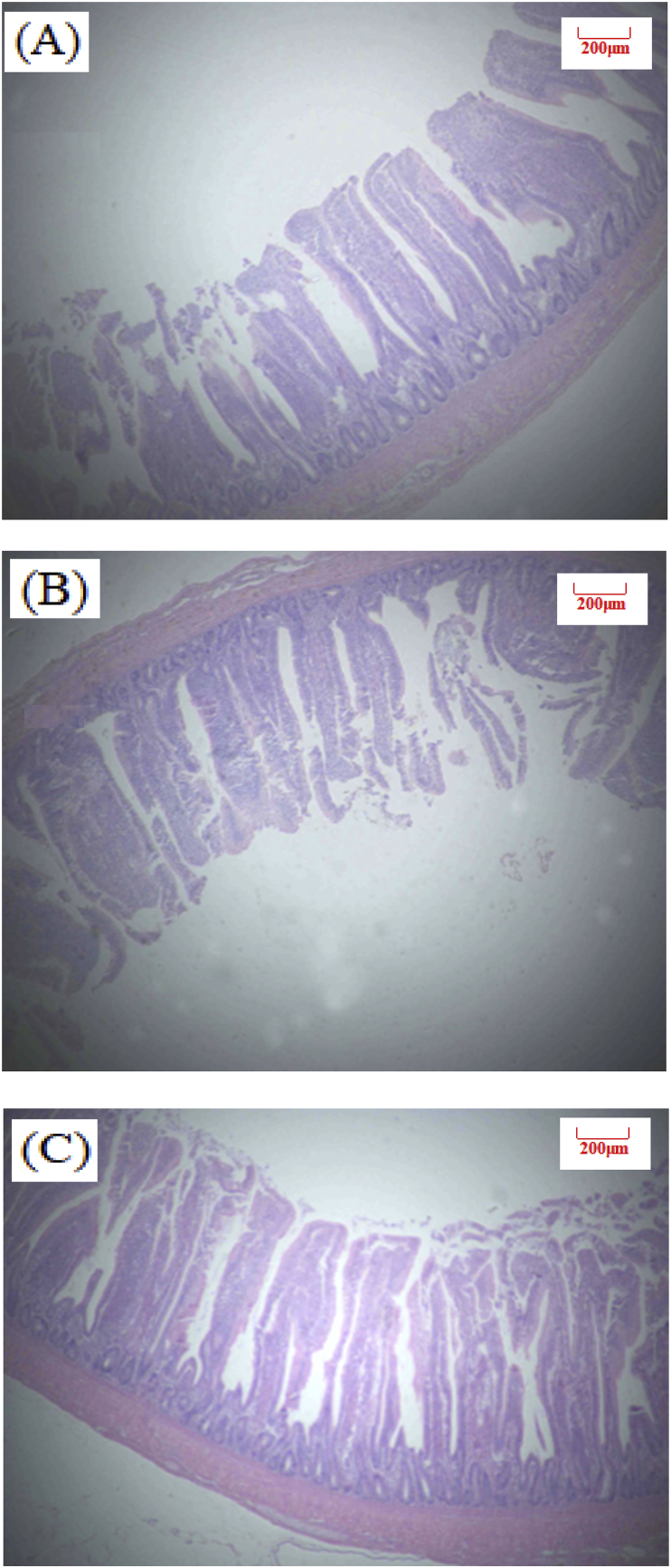

Table 4 shows the effect of dietary PN supplementation on intestinal morphology of broilers at d 26 and 39 (Exp. 1). There was no statistical significance observed for intestinal VH and VH:CD ratio in our study. Birds in LE + PN group had the higher ileal VH (P = 0.13) and jejunum VH:CD ratio (P = 0.74) than the other two groups at d 26. At d 39, PN inclusion can improve jejunum and ileum VH:CD ratio by 2.5% and 8.5%, compared with the low energy group. Images of intestinal morphology are shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6. Compared with the LE group, the villi from birds in the LE + PN group were longer, organized, and generally neater, which indicates better gut health. This may explain the improved FCR and survival rate of these animals.

Table 4.

Effects of phytonutrients on gastrointestinal physiology of broilers in Exp. 1 (μm).1

| Item | NE | LE | LE + PN | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 26 | |||||

| Ileum | Villus height | 515.2 ± 58.7 | 523.6 ± 72.2 | 648.1 ± 153.0 | 0.13 |

| Crypt depth | 102.2 ± 15.2 | 113.5 ± 17.0 | 130.7 ± 24.9 | 0.12 | |

| VH:CD ratio | 5.17 ± 1.22 | 4.73 ± 1.13 | 4.94 ± 0.49 | 0.79 | |

| Jejunum | Villus height | 866.9 ± 216.6 | 1103.0 ± 377.1 | 1029.5 ± 321.0 | 0.43 |

| Crypt depth | 140.1 ± 15.1 | 161.7 ± 30.2 | 149.5 ± 52.2 | 0.57 | |

| VH:CD ratio | 6.27 ± 1.78 | 6.73 ± 1.63 | 7.03 ± 1.43 | 0.74 | |

| Duodenum | Villus height | 1,721.3 ± 504.0 | 1,804.8 ± 317.6 | 2,015.8 ± 105.7 | 0.41 |

| Crypt depth | 195.6 ± 24.5 | 272.2 ± 165.5 | 206.8 ± 49.2 | 0.41 | |

| VH:CD ratio | 8.71 ± 1.81 | 8.11 ± 3.39 | 10.21 ± 2.47 | 0.43 | |

| Day 39 | |||||

| Ileum | Villus height | 867.1 ± 228.8 | 760.6 ± 182.8 | 743.4 ± 229.3 | 0.16 |

| Crypt depth | 197.6 ± 61.4 | 225.4 ± 66.6 | 199.2 ± 45.4 | 0.56 | |

| VH:CD ratio | 4.68 ± 1.63 | 3.65 ± 1.33 | 3.96 ± 1.76 | 0.18 | |

| Jejunum | Villus height | 1,659.7 ± 263.5 | 1,540.4 ± 297.0 | 1,348.5 ± 233.0 | 0.19 |

| Crypt depth | 291.8 ± 111.8 | 307.7 ± 80.2 | 264.2 ± 51.0 | 0.71 | |

| VH:CD ratio | 6.46 ± 2.66 | 5.17 ± 1.28 | 5.30 ± 1.45 | 0.47 | |

| Duodenum | Villus height | 1,669.2 ± 180.4 | 1,603.3 ± 273.5 | 1,692.3 ± 75.0 | 0.72 |

| Crypt depth | 339.1 ± 81.2 | 306.7 ± 48.7 | 337.3 ± 23.6 | 0.53 | |

| VH:CD ratio | 5.20 ± 1.49 | 5.37 ± 1.46 | 5.03 ± 0.3 | 0.89 | |

PN = phytonutrients, VH:CD ratio = villus height:crypt depth ratio.

NE, birds were fed diets with normal energy content. LE, birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed. n = 12 broilers.

Fig. 1.

Slices of broilers duodenum at 26 d of age (Hematoxylin-eosin staining, 40×). (A) NE, Birds were fed diets with normal energy content. (B) Birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed. (C) Phytonutrient group (LE + PN).

Fig. 2.

Slices of broilers jejunum at 26 d of age (Hematoxylin-eosin staining, 40×). (A) NE, Birds were fed diets with normal energy content. (B) Birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed. (C) Phytonutrient group (LE + PN).

Fig. 3.

Slices of broilers ileum at 26 d of age (Hematoxylin-eosin staining, 40×). (A) NE, Birds were fed diets with normal energy content. (B) Birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed. (C) Phytonutrient group (LE + PN).

Fig. 4.

Slices of broilers duodenum at 39 days of age (Hematoxylin-eosin staining, 40×). (A) NE, Birds were fed diets with normal energy content. (B) Birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed. (C) Phytonutrient group (LE + PN).

Fig. 5.

Slices of broilers jejunum at 39 days of age (Hematoxylin-eosin staining, 40×). (A) NE, Birds were fed diets with normal energy content. (B) Birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed. (C) Phytonutrient group (LE + PN).

Fig. 6.

Slices of broilers ileum at 39 d of age (Hematoxylin-eosin staining, 40×). (A) NE, Birds were fed diets with normal energy content. (B) Birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed. (C) Phytonutrient group (LE + PN).

3.3. Economic benefit

Table 5 showed the economic benefit of different energy reduction and PN addition (PN cost was included). Compared with the NE group, including PN product in the low energy diet cut the feed cost by 0.07 CNY/kg BW. The LE + PN diet also increased the profit by 0.09 and 0.05 CNY/bird, compared with NE and LE diets, respectively. Also, PN supplementation reduced birds feed intake, which brought lower feed cost and better profit.

Table 5.

Feed cost for weight gain and profit of chicks at 39 d of age in Exp. 1.1

| Item | NE | LE | LE + PN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feed cost for weight gain, CNY/kg BWG | 4.87 | 4.83 | 4.8 |

| Economic profit, CNY/bird | 2.25 | 2.29 | 2.34 |

PN = phytonutrients, CNY = china yuan.

NE, birds were fed diets with normal energy content. LE, birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed.

3.4. Energy content and nutrient digestibility

Table 6 shows the data from the energy and nutrient metabolism experiment (Exp. 2). The AMEn values of the NE and LE groups were consistent with our experimental design (−60 kcal/kg). Compared with the NE group, the AME and AMEn of birds fed LE diet were lower by 1.9% (P < 0.05) and 1.8% (P < 0.05), respectively. The LE + PN treatment had no significant effect on AME and AMEn values, compared with the LE group (2,863 vs. 2,852 kcal/kg). Moreover, dietary PN had no impact on dietary energy digestibility (72.9% vs. 73.1%) (P = 0.29) and protein apparent digestibility (61.2% vs. 61.1%) (P = 0.26).

Table 6.

Effects of phytonutrients on AME and nutrient digestibility of broilers in Exp. 2.1

| Item | NE | LE | LE + PN | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet AME, kcal/kg | 2,907 ± 29a | 2,852 ± 50b | 2,863 ± 51b | 0.02 |

| Diet AMEn, kcal/kg | 2,748 ± 28a | 2,696 ± 44b | 2,709 ± 47b | 0.03 |

| Energy digestibility, % | 73.7 ± 0.7 | 72.9 ± 1.3 | 73.1 ± 1.3 | 0.29 |

| Protein apparent digestibility, % | 62.7 ± 0.7 | 61.2 ± 1.3 | 61.1 ± 2.5 | 0.26 |

AME = apparent metabolizable energy, AMEn = nitrogen-corrected AME.

NE, birds were fed diets with normal energy content. LE, birds in were fed NE diet but with 60 kcal removed.

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth performance

The result from this study showed that when diet energy content was decreased by 60 kcal/kg, there was a negative effect on broiler growth and AME value. Many studies have been conducted to test the effect of diet energy level on broiler growth performance and health condition. High-energy diets promoted efficiency of feed utilization and maximized growth rate of broilers (Leeson and Summers, 1991). It was reported that as energy intake was restricted, there was a direct negative effect on growth rate (Leeson and Summers, 1997). These previous researches were partly in agreement with our results.

One experimental diet was formulated to be relatively lower in ME for testing the responses to supplementation of PN. The improvement in performance observed when PN included in low-energy diets has been previously reported (Amerah et al., 2009, Cowieson et al., 2010). To our knowledge, this is the first report of such effects in a large commercial setting. It was also indicated that dietary supplementation of 100 mg/kg of a mixture of PN increased dietary AMEn (Bravo et al., 2011). In the present study, the birds fed diet with PN in low energy diets, had no significant difference on BW gain, but had lower FCR compared with birds fed the low energy diet. The results obtained in the present study confirmed the improvement in feed efficiency by the mixture of PN (Bravo et al., 2011, Jamroz et al., 2005). This positive effect on feed efficiency, probably due to the function of spices to increase bile secretion, higher activity of the pancreatic and brush border enzymes (Platel and Srinivasan, 2001).

4.2. Serum anti-oxidative activity and intestinal morphology

Botsoglou et al. (2002) revealed that oregano oil can increase the antioxidative status of broiler meat by reducing MDA values. Terenina et al. (2011) reported that PN could increase antioxidative enzymes activities, non-enzymatic antioxidant glutathione peroxidase (GSH) concentration and decrease lipid peroxidatic MDA concentration in intestinal mucosa of broilers. According to Hsu et al. (2011), Portulaca extracts can improve liver GSH, SOD and hydrogen peroxidase activities, and induce oxidative stress in mouse. While in this study, no significant effect was observed between LE and the LE + PN groups, and the different result may be due to the different PN or animals used.

Both VH and CD are important indicators of the digestive health and directly related to the absorptive capacity of the mucous membrane (Buddle and Bolton, 1992). However, the literature is equivocal regarding the use of PN as feed additives in relation to gut morphology (Zeng et al., 2015). In the current study, there is a tendency that the PN fed birds got greater VH and VH:CD ratio, this may be the reason of better conversion. Pictures also indicated that villus in PN group was arranged neatly, and mucosa membrane was thicker. The results were consistent with other previous study, in which PN increased villus height, reduced CD in ileum, and also decreased the energy required for intestinal maintenance (Bravo et al., 2011).

4.3. Energy content and nutrient digestibility

It was reported that PN improved nutrient digestibility and group uniformity (Sökmen et al., 2004). Pirgozliev et al. (2015) defined that PN did not affect dietary ME, but caused a significant improvement in the utilization of dietary energy, which did not always relate to growth performance. Bravo et al. (2011) indicated that PN combinations improved energy content by 50 kcal/kg, this enhancement may be caused by a direct improvement in dietary energy digestibility or absorption, and a reduction in the energy required for the maintenance of the digestive tract. Thus it is expected that better results may be obtained when combinations of essential oils extracted from different plants are supplied (Zeng et al., 2015). Our results showed that including PN product in the low energy diet increased the AMEn content by 11 kcal/kg, but no improvement on energy and protein digestibility was observed, the different results may be due to different PN products and their activities. Meanwhile, rearing conditions should take into account for experiments involving use of PN (Pirgozliev et al., 2015).

5. Conclusion

Low energy content in the diet can decrease broiler performance, lower AME value and nutrient digestibility. Supplementing PN to a low energy diet can maintain FCR thus increase economic profit of broilers apparently via improved gut health.

Conflictsof interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the content of this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by Shandong Taishan Industry Leading Talent Project (LJNY2015006) and Major Special Science and Technology Project of Sichuan Province (2018NZDX0005).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

Contributor Information

Zhengpeng Zhu, Email: zhuzp@newhope.cn.

Yuming Guo, Email: guoyum@cau.edu.cn.

References

- Amerah A.M., Peron A., Zaefarian F. Influence of whole wheat inclusion and a blend of essential oils on the performance, nutrient utilisation, digestive tract development and ileal microbiota profile of broiler chickens. Br Poult Sci. 2011;52:124–132. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2010.548791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amerah A.M., Ravindran V., Lentle R.G. Influence of wheat hardness and xylanase supplementation on the performance, energy utilisation, digestive tract development and digesta parameters of broiler starters. Anim Prod Sci. 2009;49:71–78. doi: 10.1080/00071660802251749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . 20th ed. Assoc Off Anal Chem; Arlington, VA: 2016. Official methods of analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Botsoglou N.A., Florou P.P., Christaki E. Effect of dietary oregano essential oil on performance of chickens and on iron-induced lipid oxidation of breast, thigh and abdominal fat tissues. Br Poult Sci. 2002;43:223–230. doi: 10.1080/00071660120121436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo D., Pirgozliev V., Rose S.P. A mixture of carvacrol, cinnamaldehyde, and capsicum oleoresin improves energy utilization and growth performance of broiler chickens fed maize-based diet. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:1531–1536. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo D., Utterback P., Parsons C.M. Evaluation of a mixture of carvacrol, cinnamaldehyde, and capsicum oleoresin for improving growth performance and metabolizable energy in broiler chicks fed corn and soybean meal. J Appl Poult Res. 2011;20:115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Buddle J.R., Bolton J.R. The pathophysiology of diarrhea in pigs. Pig News Inf. 1992;13:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cowieson A.J., Bedford M.R., Ravindran V. Interactions between xylanase and glucanase in maize-soy-based diets for broilers. Br Poult Sci. 2010;51:246–257. doi: 10.1080/00071661003789347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C.K., Yeh J.Y., Wei J.H. Protective effects of the crude extracts from yam (Dioscorea alata) peel on tertbutyl hydroperoxide induced oxidative stress in mouse liver cells. Food Chem. 2011;126:429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Jamroz D., Wiliczkiewicz A., Wertelecki T. Use of active substances of plant origin in chicken diets based on maize and locally grown cereals. Br Poult Sci. 2005;46:485–493. doi: 10.1080/00071660500191056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karadas F., Beccaccia A., Pirgozliev V. Dietary essential oils improve hepatic vitamin E concentration of chickens reared on recycled litter. Br Poult Abstr. 2013;9:31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Karadas F., Pirgozliev V., Rose S.P. Dietary essential oils improve the hepatic antioxidative status of broiler chickens. Br Poult Sci. 2014;55:329–334. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2014.891098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson S., Summers J.D. Com Poul Nutr University Books; Guelph, ON, Canada: 1991. Broiler diet specifications. [Google Scholar]

- Leeson S., Summers J.D. 2nd ed. Com. Poul Nutr; 1997. Feeding programs for broilers; pp. 207–254. [Google Scholar]

- Pirgozliev V., Beccaccia A., Rose S.P. Partitioning of dietary energy of chickens fed maize- or wheat-based diets with and without a commercial blend of phytogenic feed additives. J Anim Sci. 2015;93:1695–1702. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platel K., Srinivasan K. A study of the digestive stimulation action of select spices in experimental rats. J Food Sci Technol. 2001;38:358–361. [Google Scholar]

- Sökmen M., Serkedjieva J., Daferera D. In vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antiviral activities of the essential oil and various extracts from herbal parts and callus cultures of origanum acutidens. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:3309–3312. doi: 10.1021/jf049859g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terenina M.B., Misharana T.A., Krikunovan I. Antioxidant properties of essential oils. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2011;47:4445–4449. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R.J., Oleszek W., Franz C. Dietary plant bioactives for poultry health and productivity. Br Poult Sci. 2010;51:446–487. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2010.506908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windisch W., Schedle K., Plitzner C. Use of phytogenic products as feed additives for swine and poultry. J Anim Sci. 2008;86:140–148. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z.S., Zhang H., Wang X. Essential oil and aromatic plants as feed additives in non-ruminant nutrition: a review. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2015;6:7–19. doi: 10.1186/s40104-015-0004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]