Abstract

Background

Suicide is a leading cause of premature death in people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Although exposure to stressors can play a part in the pathways to death by suicide, there is evidence that some people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia can be resilient to the impact of suicide triggers.

Aims

To investigate factors that contribute to psychological resilience to suicidal thoughts and behaviours from the perspectives of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Method

A qualitative design was used, involving semi-structured, face-to-face interviews. Twenty individuals with non-affective psychosis or schizophrenia diagnoses who had experience of suicide thoughts and behaviours participated in the study. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and examined using inductive thematic analysis.

Results

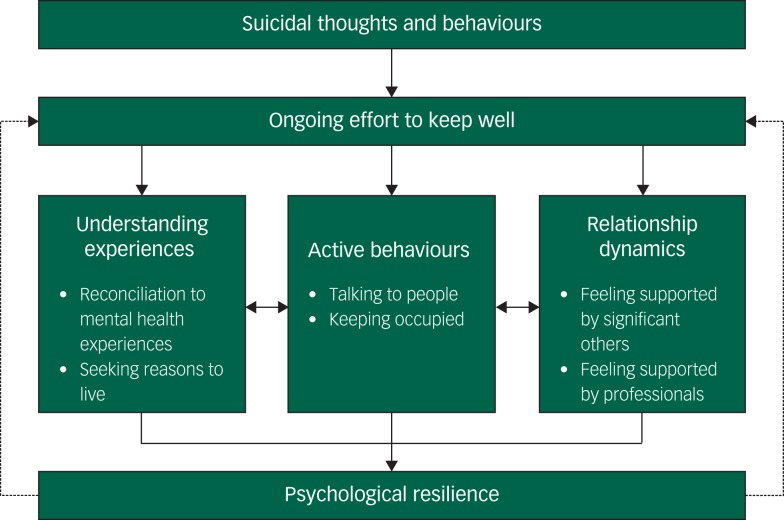

Participants reported that psychological resilience to suicidal thoughts and behaviours involved ongoing effort. This ongoing effort encompassed: (a) understanding experiences (including reconciliation to mental health experiences and seeking reasons to live), (b) active behaviours (including talking to people and keeping occupied), and (c) relationship dynamics (including feeling supported by significant others and mental health professionals).

Conclusions

Psychological resilience was described as a dynamic process that developed over time through the experiences of psychosis and the concomitant suicidal experiences. Psychological resilience can be understood using a multicomponential, dynamic approach that integrates buffering, recovery and maintenance resilience models. In order to nurture psychological resilience, interventions should focus on supporting the understanding and management of psychosis symptoms and concomitant suicidal experiences.

Declaration of interest

None.

Keywords: Psychological resilience, suicidal thoughts, suicidal behaviours, schizophrenia, psychosis

Schizophrenia is a severe mental health problem, associated with life-long disability, poor quality of life and high societal and economic costs.1,2 Suicide is a leading cause of premature death in people with schizophrenia diagnoses.3,4 The estimated lifetime risk of death by suicide in people with schizophrenia has been reported as around 10%.5 Although exposure to negative stressors can be central in the pathway to suicidal thoughts and behaviours, there is evidence that people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia can be resilient to the impact of suicide triggers.6–9 There are inconsistencies in the ways psychological resilience is conceptualised and defined.10,11 Definitions of resilience have included conceptualisations as a trait, as an outcome and as a process.12,13 More recently, multicomponential, dynamic definitions including all three conceptualisations have been proposed to fully encompass the complexity of resilience across both individual and societal levels.13 For example, a recent literature review identified resilience as a dynamic process, encompassing immunity, growth and bouncing back, and as a characteristic, including personal and social resources.14 In relation to the three conceptualisations, the current study defined psychological resilience as outcomes, attributes or processes of coping with, adapting to and rebounding from adverse events.13–16

Several studies have examined psychological resilience to suicidal experiences in people with schizophrenia.7,17–20 A qualitative study reported a spectrum of psychological factors including passive acceptance, resistance (inner strength, getting on with things, withstanding pressure), and active responses (cognitive and emotional coping strategies) as potentially contributing to psychological resilience.7 However, the study focused on factors that promoted resilience to negative life events and stressors (for example experiencing psychosis symptoms, hearing voices) as opposed to suicidal experiences, specifically. A mixed-methods study found that perceived social support from friends and family countered suicidal thoughts, potentially contributing to psychological resilience.17 A criticism of the study is that it used a vignette describing a character with psychosis and suicidal experiences, rather than examining individual accounts of such experiences. In order to understand the concept of psychological resilience to suicidal experiences, it is essential to examine it in individuals who have had such experiences.

Research aim

The current evidence is limited in two ways. First, largely missing from the literature is the in-depth investigation of the unique perspectives of individuals with experiences of suicidal thoughts and behaviours and schizophrenia diagnoses. No work to date has examined the factors perceived by people with schizophrenia diagnoses to be related to psychological resilience to suicidal experiences. Second, most studies investigating psychological resilience have primarily relied on questionnaire designs.19,20 This methodological approach may not capture the complex relationships between psychological resilience and suicidal experiences. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine which factors contribute to psychological resilience to suicidal experiences from the perspectives of individuals with schizophrenia diagnoses.

Method

Design

A qualitative design was used involving semi-structured, face-to-face interviews. This interview format was considered most appropriate for addressing the research aims because of its flexibility and the opportunity to explore perceptions and experiences as they were disclosed.21

Participants and recruitment

The participant inclusion criteria are presented in Appendix 1. A self-selected approach to sampling was adopted.22 Participants with the relevant mental health and suicidal experiences (i.e. lifetime suicidal thoughts and/or suicide attempts) were recruited from the National Health Service (for example community, early intervention and recovery mental health services, rehabilitation units) and self-help groups. In particular, participants were identified by mental health professionals (such as care coordinators) and informed about the study. Potential participants could self-refer to the study via posters displayed at mental health services and self-help groups (for example the Hearing Voices Network).

Procedure

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures were approved by North West – Greater Manchester Central Research Ethics Committee (17/NW/0211). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

A topic guide for semi-structured interviews facilitated in-depth examination of experiences23 (see Appendix 2 for the topic guide). It was developed from a review of the literature and consultations with individuals with suicidal experiences. Interviews covered three broad topics: (a) experiences of managing suicidal experiences, (b) factors that were perceived as conferring resilience to suicidal experiences, and (c) understanding of the concept of psychological resilience. Individual understanding of factors that contributed to psychological resilience were used during the interviews. This helped contextualise people's experiences of getting through times when they were feeling suicidal, providing further understanding of the concept of psychological resilience. Participants were interviewed in person by K.H. Participants also provided details about their age, gender, ethnicity, occupation, living arrangements, relationship status and diagnosis. Before and after the interview, participants completed a visual analogue scale (VAS), ranging from 0 (lowest mood) to 100 (best mood possible), to monitor changes in mood as a result of participating in the study.24 In addition, a risk protocol, developed collaboratively with patients, assured appropriate sensitivity to the context of interviewing participants who may experience distress following an interview. At the end of each interview, a task for inducing positive mood states was completed that aimed to minimise potential distress as a result of the interview.24,25 This task included thinking about positive personal characteristics that people liked or felt proud of, or remembering enjoyable activities or life events. Participants took part in the task, if they wished. This technique has been used by members of the research team in a range of previous studies.25,26

Data analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, at which point identifying information, such as names and places, was removed. NVivo qualitative data analysis software27 facilitated analysis. An inductive thematic analysis identifying semantic and latent codes and themes across the data corpus was used.28 A semantic level of analysis helped understand participants' descriptions of experiences, whereas a latent level of analysis facilitated the exploration of underlying assumptions and ideologies beyond the surface level of understanding.28,29 Thematic analysis was selected because it offers a flexible and systematic approach to examining individual experiences and perceptions.28

The data analysis was conducted by K.H., with S.P., P.G. and G.H. contributing to critical discussions of analytic interpretations.30 Two steps were taken to ensure trustworthiness of the analysis.31 First, a subset of the transcripts was read and coded by members of the research team, followed by a discussion of initial codes and themes suggested by the data. Second, Braun and Clarke's checklist of 15 strategies was followed throughout the study.28 As data collection and analysis were conducted concomitantly, the topic guide was revised iteratively to include ideas arising from the analysis.32,33 The formulation of codes and themes was discussed and reviewed by all authors as the study progressed. Data collection terminated when incoming data yielded no new themes and codes relevant to the research question.34

Results

Participants' characteristics are presented in Table 1. In total, 33 individuals were approached. Eighteen of those self-referred and 15 were referred to the study by mental health staff. Two of the individuals who self-referred and two who the staff referred were not eligible to participate because of having mental health problems other than schizophrenia. A further six of the self-referred and three of the staff-referred individuals withdrew prior to consenting to be interviewed for unknown reasons. The final sample comprised 20 participants. Interviews ranged between 15 and 207 min (mean 111 min; median 52 min). All participants reported past suicidal experiences, such as suicidal thoughts, plans, attempts and/or self-harm. Eight participants reported past suicide attempts. Four participants were experiencing suicidal thoughts around the time of the interview.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Years, mean (s.d.) | 48 (15.5) |

| Years, range | 23–75 |

| Gender, women: % (n) | 50 (10) |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | |

| White British | 80 (16) |

| Black British | 5 (1) |

| Mixed ethnicity | 15 (3) |

| Occupation, % (n) | |

| Unemployed | 55 (11) |

| Self-employed | 5 (1) |

| Retired | 20 (4) |

| Volunteer | 5 (1) |

| Student | 5 (1) |

| Living arrangements, % (n) | |

| Supported accommodation | 25 (5) |

| Rehabilitation unit | 5 (1) |

| Alone | 40 (8) |

| With family | 25 (5) |

| With carer | 5 (1) |

| Suicidal experiences, % (n) | |

| Lifetime | 100 (20) |

| Current (at the time of interview) | 20 (4) |

| Duration of illnessa | |

| Years, mean (s.d.) | 22.2 (13.2) |

| Years, range | 0.4–43 |

| Current diagnosis, % (n) | |

| Schizophrenia | 25 (5) |

| Paranoid schizophrenia | 40 (8) |

| Chronic schizophrenia | 5 (1) |

| Treatment resistant schizophrenia | 5 (1) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 10 (2) |

| Psychotic disorder | 5 (1) |

| Acute psychosis | 5 (1) |

| Unspecified non-organic psychosis | 5 (1) |

| Medication,b % (n) | |

| Clozapine | 25 (5) |

| Aripiprazole | 40 (8) |

| Quetiapine | 5 (1) |

| Olanzapine | 10 (2) |

| Zuclopenthixol | 10 (2) |

| Flupentixol | 10 (2) |

| Risperidone | 5 (1) |

| Fluphenazine | 5 (1) |

| Amisulpride | 5 (1) |

Based on data from 19 participants.

Some participants were prescribed two types of antipsychotic medication.

The scores on the mood VAS ranged between 30 and 90 out of a maximum 100 at the beginning of the interview (mean 62.50, s.d. = 19.23) and between 30 and 95 at the end of the interview (mean 62.75, s.d. = 19.75). Participants reported an overall better mood after participation in the interviews.

Psychological resilience as an ongoing effort

This overarching theme describes participants' perception of psychological resilience as an ongoing effort to effectively manage psychosis and the concomitant suicidal thoughts and behaviours: ‘Put the effort in and you'll get there in the end…You keep going and you'll get there at the end.’ (participant 2, man). Experiences of psychotic symptoms and suicidal thoughts and behaviours were reported to be inextricably linked. Therefore, ability to cope with psychotic symptoms was perceived as reducing the severity of suicidal experiences. Participants were determined to ‘get on with life’ (participant 10, man) and ‘carry on’ (participant 9, man), despite the intensity of their psychotic symptoms: ‘…I'd have killed myself by now if I wasn't resilient. […] I managed to keep going, even though I was hearing voices.’ (participant 14, woman). It was individuals' initiative and effort to maintain their well-being that was reported to subsequently reduce suicidal experiences: ‘I'm trying to push myself to get better because the medicine will only do so much. You've got to help yourself as well.’ (participant 11, man). This ongoing effort to keep well was reported to encompass three aspects: (a) understanding experiences; (b) active behaviours; and (c) relationship dynamics (see Fig. 1 for a conceptual model).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model including factors that contribute to psychological resilience to suicidal thoughts and behaviours in people with schizophrenia diagnoses.

Theme 1: understanding experiences

This theme highlights having an understanding of personal suicidal experiences and a purpose in life as key aspects of developing psychological resilience to suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Understanding was based on individuals' perceptions of their experiences and the different ways they made sense of these over time. The process of understanding lead to reconciliation to and acceptance of these experiences, and ultimately, finding purpose in life. These were described as active, effortful processes that took time to develop.

Reconciliation to mental health experiences

Participants reported that it was important to understand the causes of their suicidal experiences, in order to be able to address and manage them effectively: ‘I wish I had more of an understanding on it [suicidal experience] because, it's like anything, if you understand that it's wrong, in your mind you know it's wrong.’ (participant 17, woman).

‘Insight into the illness is everything because you can then say, “right, these thoughts are happening because…”.’ (participant 12, woman)

For most participants, psychotic experiences, such as command hallucinations and delusions, were key contributing factors to suicidal thoughts and acts. Participants described a period of actively seeking an explanation for the origin of psychosis and the subsequent suicidal experiences through educating themselves:

‘I was trying really hard and I was developing insight, getting educated and thinking about myself, how's this happened to me, how did it happen, how can I stop that happening, how can I move forward.’ (participant 1, man)

Having a coherent understanding of psychotic experiences was seen as an essential aspect of recognising and managing suicidal thoughts and behaviours. From participants' perspectives, psychological resilience was shaped by previous experiences of psychosis and suicidal thoughts and behaviours: ‘It's just experience of the illness and the nature of the illness and know what it is and things like that.’ (participant 3, man). The ability to resist the voices that were telling participants to self-harm or take their own life developed through an understanding of the mental health problem, which was absent during the initial stages of psychosis. The longer people experienced such problems, the better they perceived were able to manage them effectively:

‘When I first got diagnosed, I did it [self-harm] quite a lot because it was scary seeing things in my head and that. They [the voices] were telling me to do that, but I know better now […] to challenge them, if you like, challenge the voices.’ (participant 11, man)

Participants described that their ability to rationalise their experiences helped them to not go through with a suicide attempt, and in turn, contributed to psychological resilience. They underwent a process of intermittent rationalisation, often during times of crisis, when they were able to recognise that the suicidal thoughts and behaviours were related to psychosis:

‘I have periods – it could be five minutes in the day – that I'm rational. So, it's like convincing myself that it was my illness that was the reason I was having these thoughts and not the actual fact that I was poisoning people […] it was only those thoughts that were making me suicidal.’ (participant 12, woman)

Participants explained that over the years of learning about and understanding the nature of their psychosis and suicidal thoughts and behaviours, they eventually became reconciled to them: ‘I think it's experience. The more you experience, the more you get to understand.’ (participant 9, men). Learning to live with these experiences and accepting them as part of life took time. This process emphasised the dynamic nature of psychological resilience (‘it comes, and it goes.’ participant 7, woman). Participants reasoned that their suicidal thoughts did not necessarily define them as individuals but were perceived as aspects of life that they had to adapt to in the long term: ‘…what you do is accept the fact that it [the suicidal thought] exists […] you just have it as an existing part of your mind.’ (participant 8, man). As opposed to this active, effortful process of understanding and accepting experiences, one participant, in particular, adopted a passive approach to coping:

‘I sort of got used to it [the suicidal experience]. So, I must have thought to myself, you know, and accepting this is just the way life is now. There's nothing I can fucking do about it […] I just accepted it.’ (participant 6, woman)

The process of understanding experiences was seen as a necessary aspect of developing psychological resilience: ‘[Resilience] is developed. Unless you experience some deep problems, you don't actually get to find out whether or not you're resilient.’ (participant 14, woman).

Seeking reasons to live

Experiencing distressing psychotic symptoms can give rise to feelings of hopelessness and suicidal experiences. Participants spoke about the importance of being able to find reasons to carry on with their life in such difficult circumstances. Some people could identify something that made them feel life was worth living: ‘I must have been [resilient], not to go through with it [the suicide attempt]. I must have felt there's something worth living for.’ (participant 4, man). Seeking out purpose in life was key in building psychological resilience to suicidal thoughts and behaviours. This purpose in life was unique to each person and seemed to relate to the individual's current circumstances and what they considered to be of main importance. For example, one participant described obtaining a sense of security after receiving his state pension as something worth living for:

‘Something worth living for… in August I'm getting my state pension, so that would be a bit of extra money […] I'd feel a bit more secure if I got my pension ’cause that's for life, isn't it?’ (participant 4, man)

Having a sense of responsibility for significant others, such as siblings, parents or children, was perceived as a strong reason to live that protected against suicidal thoughts and behaviours. In particular, connection to significant others and wanting to be there for them was an example of a specific reason to live:

‘Family, especially my little brother. He looks up to me, so I need to set a good example for him. And my mum and my sister and my brother […] I don't want to fail them. I want them to be proud of me.’ (participant 11, man)

Feeling responsibility to care for their own children was perceived as a reason to live: ‘That's what kept me going, my children, and the thought of them being left without a mum.’ (participant 17, woman). However, this sense of responsibility was removed from the individual when their children were no longer dependent on them. In this case, having children was no longer identified as a strong reason to live:

‘This time was the worst because all my kids have grown up. In the past when I've been psychotic and suicidal, I've always thought, “don't do that, the kids are only young, and you can't leave them without a mum”. […] But [daughter's name] is twenty-three now and that's why I think it was the worst.’ (participant 12, woman)

Having desire to develop personally and professionally was another example of a specific reason to live that could contribute to resilience to suicidal experiences: ‘I want to make a name for myself […]. I want to go back to college to learn some barbering and hopefully start working at some point again.’ (participant 11, male).

Therefore, having a sense of security, responsibility to others and a desire for personal development were reported as key precursors in determining individual reasons to live that contributed to building and maintaining psychological resilience to suicidal experiences.

Theme 2: active behaviours

This theme encompasses a range of behaviours that participants described as helpful in coping with suicidal thoughts and behaviours and developing resilience to such experiences. These behaviours included talking to people and keeping occupied.

Talking to people

Participants explained that talking to people about their experiences of suicide had a cathartic effect: ‘it is better to tell the truth of how you feel completely… because, then you have opened up, so, get it off your chest.’ (participant 15, man). Talking about these experiences was challenging because of the emotional nature of the topic: ‘it's depressing – people don't like mental health problems.’ (participant 9, man). However, talking to others was perceived as important and necessary for improving well-being and not feeling alone:

‘I don't have any tips and pointers on how to stop feeling suicidal, other than to talk to people… I know, it might upset people but it's just, when you are having feelings of suicide, and you feel like ending it all, it's just, it can be a very lonely place.’ (participant 1, man)

‘…a problem shared, is a problem halved. It shows you are not in a boat by yourself sorta thing, so… You're not feeling this and maybe talking to someone else can help you.’ (participant 3, man)

Finding out that there were other people with similar experiences, through talking, made participants feel less alone and gave them the perception that they can get through times of crisis: ‘…the more I talked to people, the more I realised I weren't on my own in this bullshit; it made me feel safer and better.’ (participant 6, woman).

The therapeutic effect talking had on the individual was a worthwhile endeavour, potentially reducing the psychological distress of psychotic and suicidal experiences and improving confidence: ‘It [talking] helps a lot. It's good to mix with people and that… It gives you confidence.’ (participant 9, man).

Keeping occupied (‘I do anything to take my mind off suicide’)

Performing daily activities and routines that required a level of concentration helped surpress thoughts of suicide. Examples were numerous (for example reading, listening to music, cooking, cleaning, going for a walk/to the gym, watching television, playing computer games): ‘I like cooking. It just takes your mind away […] you need to distract yourself in some way.’ (participant 2, man). Although participants identified the importance of keeping busy in countering suicidal thoughts and behaviours, they were not clear why or how this helped: ‘I don't know. They [distractions] just do help. Don't ask me how they do.’ (participant 13, woman). It is important to note that keeping busy did not completely remove the thoughts of suicide but was perceived as a way of weakening their impact on individuals: ‘It [music] takes the edge off it [the suicidal thought] but doesn't completely get rid of it… it's easier to manage.’ (participant 3, man).

Importantly, although distracting activities appeared helpful in ameliorating suicidal thoughts, some participants described the opposite experience:

‘I've got a list of things that the crisis team drew up for me […] like try to watch the telly or I listen to music, or have a shower… Sometimes I get to the end of the list and I've tried everything, and it doesn't work.’ (participant 16, woman)

It was not clear why the identified activities that helped ameliorate suicidal thoughts were sometimes deemed as ineffective, but it appeared to relate to the perceived distress and severity of psychotic experiences: ‘I can resist them [the voices] for a few days and then… I just give up fighting. Sometimes it can go on and on, and on, and I just ignore it for so long. You can only take so much before you give in to it.’ (participant 11, man). In such instances, the role of significant others and mental health professionals in supporting individuals was essential.

Theme 3: relationship dynamics

This theme highlights the important role of significant others, such as family and friends, and mental health professionals in building individual resilience to suicidal thoughts and behaviours. It should be noted that, in some cases, feeling supported by others was instrumental in times of crisis, whereas in others actively seeking and maintaining supportive relationships was key in coping with suicidal experiences and developing psychological resilience.

Feeling supported by significant others

Significant others were reported to have a key role in helping develop psychological resilience to suicidal experiences. Participants also emphasised the role of significant others in making them feel supported and loved, which was key to building and maintaining psychological resilience to suicide:

‘I have got a lot of support at home and a loving family, I think that helps a lot. I sometimes think to myself […] if [people] haven't got a family to support them, then that [suicidal experience] can affect them more.’ (participant 15, man)

However, some participants felt that they lacked this source of support or felt unable to seek input from family or friends because they did not want to be perceived as a burden or to be rejected:

‘Well, you can bounce off them [friends], can't you? But if you become a pain, then you're back to suicide on your own because they just reject you.’ (participant 8, man)

Feeling supported by mental health professionals

Mental health professionals were seen as having a crucial role in providing support, particularly at times of crisis or when individuals' suicidal experiences felt too severe and difficult to cope with. It was at these times that participants perceived their psychological resilience to be at its weakest. In those cases, they tended to seek support from mental health professionals, such as care coordinators or crisis teams: ‘If the [suicidal] thought's there but it's not as strong, I can just get on with my day-to-day business because I'm used to it. If it's stronger, then that's when I'll ring my CPN [community psychiatric nurse].’ (participant 11, man). This emphasised the role of mental health services in providing support for individuals in managing their suicidal experiences: ‘I'm cared for, it's the fact that the effort has been made by me and the care community around me…’ (participant 8, man).

Participants believed that, in order to maintain psychological resilience and rebound from suicidal experiences, having supportive and caring professionals was key. Furthermore, the described changes in the levels of psychological resilience in relation to the severity of suicidal thoughts and acts highlighted psychological resilience as a dynamic concept:

‘But resilience is something that develops, isn't it? If you [the health professional] are able to say to a patient, “Look, you've been at rock bottom, you've come out. You've been resilient, you've become stronger,” it builds your confidence up.’ (participant 12, woman)

Providing support when it was most needed and reminding individuals about past experiences of resilience, were aspects of care which professionals could prioritise to help strengthen psychological resilience.

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first study to investigate factors that contribute to psychological resilience to suicidal thoughts and behaviours from the unique perspectives of individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. An important, novel contribution was that a dynamic model capturing psychological resilience to suicidal experiences in people with schizophrenia was developed, based on the data, which has the potential to inform clinical practice (see Fig. 1 for a conceptual model). Maintaining psychological resilience appeared to be difficult, particularly during times of being psychologically unwell, hence leaving individuals vulnerable to suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Psychological resilience to suicidal thoughts and behaviours was described as a complex, dynamic, temporal process that required substantial effort on behalf of the individual. This process included developing understanding of experiences with respect to psychotic symptoms, and the thoughts, plans and urges to attempt suicide, active behaviours (i.e. talking to others, keeping occupied) and relationship dynamics (i.e. feeling supported by others).

A criticism of the concept of resilience is that the definitions generated in the extant literature lack precision, and the psychological mechanisms underpinning the concept are therefore poorly understood.14 It has been proposed that psychological resilience mechanisms can be captured using a multicomponential, dynamic approach.13,19,35 Five models can be identified that are important in understanding psychological resilience, including the unidimensional (‘two poles’), two-dimensional (buffering), recovery, maintenance and psychological immunity models8,35–38 (see Appendix 3 for description of the resilience models).

The findings of this study support a multicomponential, temporally dynamic approach to understanding psychological resilience to suicide that is in accord with the five resilience models. The results suggest that the unidimensional and psychological immunity models are inadequate to explain the complex concept of psychological resilience. No participant attributed their psychological resilience to the absence of suicide triggers or to being immune to the negative impact of suicide triggers on their well-being. On the contrary, suicidal experiences were associated with great psychological distress that had a major impact on the participants' well-being. Instead, suicide triggers were perceived as perpetual factors that had to be actively buffered against, in an effort to maintain well-being, in the process of returning to previous levels of functioning. Therefore, a multicomponential approach to understanding psychological resilience, integrating buffering, recovery and maintenance factors appears to be the most optimal. Developing a resilience framework from a multifaceted theoretical and conceptual perspective clearly identifies a focus for evidence-based future resilience work.13,39,40

In the current study, individuals indicated that psychological resilience to suicidal thoughts and acts developed through the experience of countering the impact of psychotic symptoms, suicidal experiences and their influence on well-being. This resonated with the two-dimensional (buffering) and maintenance resilience models and with evidence from the extant literature that conceptualises psychological resilience as a dynamic process and is counter to the literature that presents it as a static entity or a personality trait.41,42 It has been suggested that psychological resilience exists on a continuum that fluctuates to varying degrees, depending on the stressors and protective factors present during different life circumstances.43 Hence, an individual who is resilient to a particular suicidal experience may not necessarily continue to be resilient if the circumstances surrounding these experiences have altered. This notion further supports the proposition for a dynamic approach to conceptualising psychological resilience.

The participants in this study considered psychological resilience to suicidal experiences an effortful endeavour that included developing understanding, active behaviours and feeling supported by others. This resonated with the two-dimensional (buffering), maintenance and recovery resilience models and the wider research that characterises recovery from psychosis as an ongoing process rather than an end result of an absence of symptoms.44,45 Highlighting psychological resilience as a dynamic process corroborates extant conceptualisations of resilience as an effort to integrate experiences and move forward.46,47 For example, a qualitative study investigating experiences of a first episode of psychosis identified two key themes, namely tenacity, which required long-term effort, and rebounding.48 Additional resources such as determination and support from others were described as resilience mechanisms.48 The results of that study identify a potential mechanism of effortful tenacity, bouncing back and social support.48 There appear to be a variety of interlinked factors reported in the wider literature that overlap with the current results and may contribute to psychological resilience. The findings of the current study in relation to developing understanding and purpose, and active behaviours should be investigated more robustly in order to elucidate potential resilience mechanisms and factors to focus on when developing and maintaining individual psychological resilience, specifically to suicidal thoughts and behaviours.

Participants described that maintaining psychological resilience appeared to be difficult, particularly during times of being psychologically unwell, hence leaving individuals vulnerable to suicidal thoughts and behaviours. In such instances, actively seeking and receiving support from significant others and mental health professionals was considered of paramount importance. A particular contribution of the conceptual resilience model developed in this study related to the importance of feeling supported by mental health professionals and significant others in developing and maintaining psychological resilience to suicidal thoughts and behaviours. This aspect of perceived support is not explicitly featured in any of the existing models of resilience.8,35–38 The role of perceived social support in reducing the severity of suicidal thoughts and behaviours is in accord with a vast body of research including individuals with severe mental health problems, such as schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and bipolar disorder.7,17,19,20,26,49,50 These studies indicate that feeling supported by others may be a transdiagnostic resilience factor that reduces suicidal thoughts and behaviours and, therefore, warrants incorporation into multicomponential models of resilience. The current findings also highlighted psychosis-specific aspects of psychological resilience that related to understanding psychosis and the suicidal experiences that may ensue. It is possible that certain psychological factors, such as perceived social support, are part of a general transdiagnostic mechanism, applicable to different mental health problems, but other factors, such as psychosis symptoms, are moderated by aspects pertinent to a particular mental health problem.6

Limitations

The study has four limitations that warrant discussion. First, those who participated were potentially the most interested in the study topic or most willing to openly talk about their experiences, resulting in self-selection bias.51 The findings, therefore, may not reflect the experiences of those who feel less willing to discuss their experiences and who may feel less able to manage their suicidal thoughts and urges. Second, the current findings are limited by the number of individuals who took part in the interviews. This has particular implications for the generalisability of the data to other studies.52 Although saturation was achieved, indicating the data corpus was sufficient to reach its conclusions, it may not capture the full range of experiences of psychosis and suicide. Hence, further research is needed to test the applicability of the conceptual model to the wider clinical population. Third, the majority of the participants were white British, which further limits the generalisability of the findings to other cultural backgrounds. Research has shown considerable underrepresentation of black and minority ethnic groups in mental health services.53,54 It is important to identify alternative sources of psychological resilience and strategies to facilitate access to mental health services by black and minority ethnic populations. This represents a clear objective for future research in this area. Fourth, only individuals under the care of mental health services were recruited into the study. These groups may have additional experiences of psychological resilience and different sources of support that were not captured, in particular their perceptions of health service staff as sources of support may be overrepresented.

Clinical implications

There are two main implications of this study for clinical practice. First, involving both significant others and mental health professionals in treatment plans that aim to develop psychological resilience was perceived as crucial by the participants. This was a key aspect of the conceptual resilience model developed in this study. The model could inform mental health professionals about what factors to prioritise in order to help develop and maintain psychological resilience in people. For example, professionals may play a role in consolidating previous instances of effectively coping with suicidal experiences, subsequently developing psychological resilience to future circumstance that can escalate suicidal experiences. Moreover, provision of support from mental health services should be a key consideration within suicide prevention initiatives given that in crisis participants relied on services when their sources of psychological resilience had depleted, and they felt unable to cope by themselves.

Second, it is essential for professionals to consider the impact of psychotic experiences on the development of psychological resilience to suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Understanding people's perceptions of their mental health problems and the way they perceive them can help inform interventions.55,56 It is important to recognise the effort that individuals are undergoing to develop and maintain psychological resilience, especially at times of crisis when resilience may be low and individuals feel vulnerable. This highlights the need for planning additional mental healthcare support during such circumstances.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our Service User Reference Group (SURG), who kindly helped develop the interview topic guide, and all participants for contributing to this research by sharing their invaluable experiences and perspectives. The data that support the findings of this study are available from K.H., upon reasonable request.

Appendix 1

Participant inclusion criteria

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. | 18 years or older. |

| 2. | Capacity to provide informed consent. |

| 3. | English speaking. |

| 4. | Schizophrenia diagnosis (i.e. schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder or psychotic disorders not otherwise specified) or experiences of non-affective psychosis, confirmed by a member of the individual's mental health team. |

| 5. | Lifetime experience of suicidal thoughts and/or behaviours. Lifetime suicidal experiences were reported by individuals who self-referred to the study themselves, or by mental health professionals who identified potential participants. |

| 6. | Contact with a National Health Service mental health team. |

Appendix 2

Interview topic guide

The following two sets of questions and prompts serve as an interview guide.

Dealing with suicidal thoughts/behaviours:

People sometimes tell us that they can also feel suicidal or sometimes act on suicidal thoughts:

Have you ever felt suicidal?

What happens to you (mentally and physically) when you have suicidal thoughts?

How do you deal with suicidal thoughts?

What stopped you from/helps you when you are feeling that way?

How did you get through such bad times?

Is there anything in particular that you found was really important in such situations?

Can you tell me about a situation when that happened?

Can you think of anything that helped you bounce back/get through suicidal thoughts? Describe what/how that happened.

Probing suicide attempts:

Have you ever attempted to take your own life?

What do you think triggered your suicide attempt?

Is there anything in particular that caused you to transition from suicide ideas to concrete plans and acts?

What did you do to stop this transition?

What did you do to cope with suicidal behaviours?

What has been helpful for you in overcoming suicidal behaviours?

Resilience questions:

What does resilience mean to you?

How would you describe someone who is resilient?

Do you think you have shown resilience when you are/were feeling suicidal?

Can you give examples of how you would have liked to be resilient?

Close by thanking them very much for their time and ask if they have any questions.

Appendix 3

Description of five resilience models

| Resilience model | Description |

|---|---|

| Unidimensional (‘two poles’) | Includes risk (for example hopelessness) at one end of the dimension and a lack of risk (for example no hopelessness) at the other end of the dimension. |

| Two-dimensional (buffering) | Includes resilience factors that weaken/moderate the relationships between suicide triggers (for example negative stressors) and suicidal thoughts and acts. |

| Recovery | Incorporates regain of psychological functioning that occurs either during or following the experience of negative events or stressors. |

| Maintenance | Involves an ability to sustain a positive outlook despite negative stressors, in the long term. |

| Psychological immunity | Involves immunity to negative events or stressors (i.e. individuals' well-being is not affected by negative stressors). |

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Mental Health Research UK and the Schizophrenia Research Fund. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Kirkbride JB, Errazuriz A, Croudace TJ, Morgan C, Jackson D, McCrone P, et al. Systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in England, 1950–2009. PLoS One 2012; 7: e31660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millier A, Schmidt U, Angermeyer MC, Chauham D, Murthy V, Toumi M, et al. Humanistic burden in schizophrenia: a literature review. J Psych Res 2014; 54: 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 334–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reininghaus U, Dutta R, Dazzan P, Doody GA, Fearon P, Lappin J, et al. Mortality in schizophrenia and other psychoses: a 10-year follow-up of the ÆSOP first-episode cohort. Schizophr Bull 2014; 41: 664–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hor K, Taylor M. Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol 2010; 24: 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolton C, Gooding P, Kapur N, Barrowclough C, Tarrier N. Developing psychological perspectives of suicidal behaviour and risk in people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia: we know they kill themselves, but do we understand why? Clin Psychol Rev 2007; 27: 511–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gooding PA, Littlewood D, Owen R, Johnson J, Tarrier N. Psychological resilience in people experiencing schizophrenia and suicidal thoughts and behaviours. J Ment Health 2017: Feb 27 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson J, Wood AM, Gooding P, Taylor PJ, Tarrier N. Resilience to suicidality: the buffering hypothesis. Clin Psycol Rev 2011; 31: 563–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips LJ, Francey SM, Edwards J, McMurray N. Strategies used by psychotic individuals to cope with life stress ad symptoms of illness: a systematic review. Anxiety Stress Coping 2009; 22: 371–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev 2010; 71: 543–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pecillo M. The concept of resilience in OSH management: a review of approaches. Int J Occup Safe Ergon 2016; 22: 291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu T, Zhang D, Wang J. A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Pers Individ Diff 2015; 76: 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalisch R, Muller MB, Tuscher O. A conceptual framework for the neurobiological study of resilience. Behav Brain Sci 2015; 38: e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayed N, Toner S, Priebe S. Conceptualizing resilience in adult mental health literature: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Psychol Psychother 2018; Jun 11 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garmezy N, Masten AS. Stress, competence, and resilience: common frontiers for therapist and psychopathologist. Behav Ther 1986; 17: 500–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolin J, Wolin S. The Resilient Self: How Survivors of Troubled Families Rise Above Adversity. Villard Books, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gooding PA, Sheehy K, Tarrier N. Perceived stops to suicidal thoughts, plans, and actions in persons experiencing psychosis. Crisis 2013; 34: 273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson J, Gooding P, Tarrier N. Suicide risk in schizophrenia: explanatory models and clinical implications, the Schematic Appraisal Model of Suicide (SAMS). Psychol Psychother 2008; 81: 55–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson J, Gooding PA, Wood AM, Tarrier N. Resilience as positive coping appraisals: testing the Schematic Appraisals Model of Suicide (SAMS). Behav Res Ther 2010; 48: 179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson J, Gooding PA, Wood AM, Taylor PJ, Pratt D, Tarrier N. Resilience to suicidal ideation in psychosis: positive self-appraisals buffer the impact of hopelessness. Behav Res Ther 2010; 48: 883–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J 2008; 204: 291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (2nd edn). Sage Publications, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards R, Holland J. What is Qualitative Interviewing? Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biddle L, Cooper J, Owen-Smith A, Klineberg E, Bennewith O, Hawton K, et al. Qualitative interviewing with vulnerable populations: individuals’ experiences of participating in suicide and self-harm based research. J Affect Dis 2013; 145: 356–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarrier N. Broad minded affective coping (BMAC): a ‘positive’ CBT approach to facilitating positive emotions. Int J Cogn Ther 2010; 3: 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owen R, Gooding P, Dempsey R, Jones S. A qualitative investigation into the relationships between social factors and suicidal thoughts and acts experienced by people with a bipolar disorder diagnosis. J Affect Dis 2015; 176: 133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.QSR. NVivo qualitative data analysis software, Version 10. QSR International Pty Ltd, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qUalitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Sage Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters S. Qualitative research methods in mental health. Evid Based Ment Health 2010; 13: 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrow SL. Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counselling psychology. J Counsell Psychol 2005; 52: 250–60. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine De Gruyter, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverman D. Qualitative Research (4th edn). Sage, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006; 18: 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson J, Wood AM. Integrating positive and clinical psychology: viewing human functioning as continua from positive to negative can benefit clinical assessment, interventions and understandings of resilience. Cogn Ther Res 2017; 41: 335–49. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goubert L, Trompetter H. Towards a science and practice of resilience in the face of pain. Eur J Pain 2017; 2: 1201–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davydov DM, Stewart R, Ritchie K, Chaudieu I. Resilience and mental health. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30: 479–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. J Personal 2004; 7: 1161–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnston MC, Porteous T, Crilly MA, Burton CD, Elliott A, Iversen L, et al. Physical disease and resilient outcomes: a systematic review of resilience definitions and study methods. Psychosom 2015; 56: 168–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rutten BP, Hammels C, Geschwind N, Menne-Lothmann C, Pishva E, Schruers K, et al. Resilience in mental health: linking psychological and neurobiological perspectives. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2013; 128: 3–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mancini AD, Bonanno GA. Predictors and parameters of resilience to loss: toward an individual differences model. J Personal 2009; 77: 1805–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zautra AJ, Hall JS, Murray KE. Resilience: a new definition of health for people and communities In Handbook of Adult Resilience (eds Reich JW, Zautra AJ, Hall JS). Guildford Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pietrzak RH, Southwick SM. Psychological resilience in OEF-OIF Veterans: application of a novel classification approach and examination of demographic and psychosocial correlates. J Affect Dis 2011; 133: 560–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deegan PE. Recovery: the lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1988; 11: 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leete E. How I perceive and manage my illness. Schizophren Bull 1989; 15: 197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2014; 5: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srivastava K. Positive mental health and its relationship with resilience. Industrial Psych J 2011; 20: 75–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henderson AR, Cock A. The responses of young people to their experiences of first-episode psychosis: harnessing resilience. Commun Ment Health J 2015; 51: 322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kleiman EM, Lui RT. Social support as a protective factor in suicide: findings from two nationally representative samples. J Affect Dis 2013; 150: 540–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panagioti M, Gooding P, Taylor PJ, Tarrier N. Perceived social support buffers the impact of PTSD symptoms on suicidal behavior: implications into suicide resilience research. Comprehen Psychiatry 2014; 55: 104–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heckman JJ. Selection bias and self-selection In Microeconometrics. The New palgrave Economics Collection (eds Durlauf SN, Blume LE). Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leung L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J Family Med Prim Care 2015; 4: 324–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Memon A, Taylor K, Mohebati LM, Sundin J, Cooper M, Scanlon T, et al. Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: a qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e012337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suresh K, Bhui K. Ethnic minority patients’ access to mental health services. Psychiatry 2006; 5: 413–6. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Connell M, Schweitzer R, King R. Recovery from first-episode psychosis and recovering self: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Rehab J 2015; 38: 359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sumskis S, Moxham L, Caputi P. Meaning of resilience as described by people with schizophrenia. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2016; 26: 273–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]