Abstract

Emergencies range from unexpected injuries to natural disasters. Populations with access and functional needs are more likely than other populations to experience adverse health outcomes during an emergency. The three-county Appalachian District Health Department engaged a collaborative array of community partners to build an all-inclusive, all-hazards emergency plan. Tabletop and full-scale exercises demonstrated the plan’s ability to meet the needs of community members with access and functional needs.

Research has shown that a person’s vulnerability to an emergency or disaster is a social and community construct.1 In other words, the social and environmental factors that limit people’s everyday ability or resiliency to cope with daily life also make them vulnerable to the effects of emergencies. Because previous research has demonstrated that groups with access and functional needs are more likely to be adversely affected in emergencies, planning and implementation of mitigation strategies should incorporate these segments of the population to reduce the public health impact of emergencies.1

INTERVENTION

An emergency is a sudden event that calls for immediate measures to minimize its adverse consequences.2 Emergencies take many forms, from a 911 call to a national disaster. They can range in any combination of consequences stemming from the following2:

-

•

Personal: heart failure, injuries, seizures, kidney failure, anaphylactic shock, heat stroke, and so forth.

-

•

Technological and man-made hazards: nuclear waste disposal spills; radiological, toxic substance, or hazardous materials incidents; utilities failures; pollution; epidemics; crashes; explosions; urban fires.

-

•

Natural disasters: earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, tsunamis, sea surges, freezes, blizzards of snow and ice, extreme cold, forest fires, drought and range infestation.

-

•

Internal disturbances: civil disorders such as riots, demonstrations run amok, large-scale prison breaks, strikes leading to violence and acts of terrorism.

-

•

Energy and material shortages: shortages resulting from strikes, price wars, labor problems, and resource scarcity.

-

•

Attacks: nuclear, conventional, chemical, or biological warfare.

According to the North Carolina General Assembly’s legislative definition G.S. 166A-4(1) (https://bit.ly/2GPIDy8), a disaster is “an occurrence or imminent threat of widespread or severe damage, injury, or loss of life or property resulting from any natural or man-made accidental, military, paramilitary, terrorism, weather-related, public health, explosion-related, riot-related cause, or technological failure or accident.”

Access and functional needs populations, commonly referred to as special needs populations or socially vulnerable populations, are groups whose members may have additional needs before, during, and after an emergency in specific areas. These specific areas are defined by Kailes et al. through the C-MIST (Communication, Medical needs, maintaining functional Independence, Supervision and Transportation) framework.3,4 One can have an access or functional needs with or without having a disability. During an emergency, people who frequently need additional response assistance as a result of an access or functional need include those who live in institutional settings, older adults, children, people with disabilities, people with limited English proficiency, and people experiencing homelessness.4 More than half of the US population is estimated to have an access or functional need.3

The “whole community” approach to emergency management stems from systems thinking, which works to bring stakeholders from different facets (e.g., families, individuals, nongovernmental organizations) to the planning table instead of only emergency responders. Incorporation of individuals with access and functional needs is vital in terms of inclusive planning for the whole community.4 In addition, the whole community approach links the C-MIST framework to emergency planning, which then works to facilitate more inclusive emergency operations plans.3 It is important to note that this approach serves to assist emergency responders and managers in better preparing for whatever access and functional needs populations exist within the community, not to better prepare for direct assistance. To ensure that access and functional needs are met, it is imperative that emergency preparation include a plan for operationalizing support for the whole community.

Our goal was to build an all-inclusive, all-hazards emergency plan that was acceptable to the community and could be effectively used in practice.

PLACE AND TIME

We worked in Alleghany, Ashe, and Watauga counties in the Appalachian mountains of western North Carolina. We initiated community meetings with our collaborative partners throughout 2016–2017 to develop an all-inclusive, all-hazards public health plan. Once this plan was complete, we performed a tabletop exercise with more than 100 people in October 2017, and a full-scale exercise followed in October 2018.

PERSON

A variety of community members and stakeholders in the three-county region were involved in the project, including those with access or functional needs. We engaged partners who represented the interests of community members as well as partners with technical and topical expertise in emergency response, and therefore we label the group “collaborative partners” because some were members of our three-county community and others were not.

PURPOSE

The purpose of the intervention was to develop an all-inclusive and all-hazards plan for public health emergencies while also aligning efforts and plans with those of emergency managers and responders to better prepare for the access and functional needs of our community.

IMPLEMENTATION

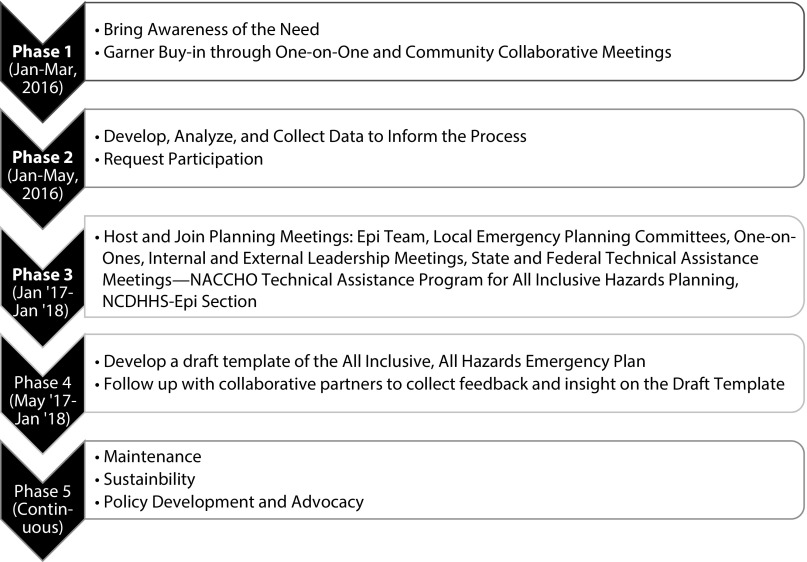

The implementation process involved a collective impact approach, depicted in Figure 1 (https://bit.ly/2KlKsVJ).5 Our collaborative partners are listed in the box on page S285. These partnerships had to be strengthened for the project to succeed; therefore, we held one-on-one meetings to establish relationships and identify shared goals related to the project.

FIGURE 1—

Process of Implementing an All-Inclusive, All-Hazards Plan Through a Collective Impact Approach

List of and Details on Collaborative Partners Included in the Development of the All-Inclusive, All-Hazards Plan.

| Partner Agency | Level(s) Represented by Partner | Example of Partnership |

| Emergency Management | Local and state | Integrated access and functional needs into medical countermeasures and strategic national stockpile |

| Local Emergency Planning Committee | Local | Varied by county; group of local and regional stakeholders who focused on emergency planning for all hazards at the local level |

| Office of Disability Services | State | Developed access and functional needs elements for exercises |

| Department of Education | Local (county) | Formed a public information officer subcommittee |

| Department of Social Services | Local | Integrated mass care and sheltering for access and functional needs |

| Division of Public Health Preparedness and Response Team | Local (regional) | Provided technical assistance around preparedness planning and epidemiology from a state perspective |

| National Association for the Advancement of Colored People | Local | Held a faith action identification drive to provide IDs for populations with access and functional needs |

| Parent2Parent | Local | Held family-focused emergency preparedness training sessions and provided go bags designed for those with access and functional needs |

Together, we created an all-inclusive, all-hazards public health plan that is interactive and searchable. This represented a major overhaul of the existing emergency plan. We also developed training sessions to incorporate contents of the revised plan. Specifically, we developed both tabletop and full-scale exercises, including PowerPoint slides and handouts, an exercise planning and implementation workbook, and an after-action report. All of these materials are available from the authors on request.

EVALUATION

To evaluate our plan, we conducted a tabletop and full-scale exercise with a strong focus on supporting people with access and functional needs during emergency mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery efforts. Nearly all relevant staff (95%) participated in both exercises. Among participating staff, 98% reported that the exercise improved their knowledge and resilience in mitigating and responding to public health emergencies. The after-action report included developing signage, technology, and just-in-time training to address point-of-distribution policies for unaccompanied minors, people needing translation services, and symptomatic individuals.

ADVERSE EFFECTS

During implementation, we discovered that more time was needed than anticipated to address various mandates and assess the history of federal, state, and local emergency plans. As we worked through existing policies and plans, we connected our local modifications to the requirements to ensure that we were meeting the needs of collaborative partners while adhering to all regulations.

SUSTAINABILITY

This project was not supported by any supplemental funding; AppHealthCare integrated it into normal work activities. The epidemiological team is continuing to meet quarterly to review and maintain the updated plan. We developed a new policy to ensure that a tabletop and full-scale exercise with a clear focus on cultural competency and integration of people with access and functional needs will be conducted annually with diverse stakeholders. Changes to existing funding streams at the state and federal levels to explicitly require the inclusion of people with access and functional needs might facilitate these activities and changes throughout local health departments.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

Historically, populations with access and functional needs have been marginalized. According to the National Council on Disability, this can be attributed to the fact that such populations were generally placed into one large category, without consideration of the unique elements of each type of access and functional need.6 It is critical for people with access and functional needs to be consulted and included in the emergency planning arena. If they are not key members of the planning team, people with access and functional needs may become alienated, thus increasing their vulnerability during emergencies and disasters.6

The field of emergency management is shifting toward the whole community approach as a result of shifts in demographic trends, the outcomes of previous disasters, and recent court cases.1,2,5,7 To ensure that the needs of more than half of the US population with access and functional needs are met, it is imperative that emergency preparations include a plan to operationalize support for the whole community. This approach offers an opportunity to build resiliency among people with access and functional needs.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Institutional review board approval was not required because this study did not involve human participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolkin AF. Reducing public health risk during disasters: identifying social vulnerabilities. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5769961. Accessed July 29, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Emergency Management Institute. EM terms and definitions. Available at: https://training.fema.gov/hiedu/termdef.aspx. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- 3.Kailes JI, Enders A. Moving beyond “special needs”: a function-based framework for emergency management and planning. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2007;17(4):230–237. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Federal Emergency Management Agency. Guidance on planning for integration of functional needs support services in general population shelters. Available at: https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/26441. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services. Public health emergency: access and functional needs. Available at: http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Pages/afn-guidance.aspx. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- 6.National Council on Disability. Effective emergency management: making improvements for communities and people with disabilities. Available at: http://www.ncd.gov/publications/2009/Aug122009. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- 7.Parsons BS, Fulmer D. The paradigm shift in planning for special-needs populations. Available at: https://training.fema.gov/hiedu/07conf/presentation/tuesday%20-%20lea%20-%20paradigm%20shift%20in%20planning%20for%20special%20needs.doc. Accessed July 29, 2019.