Abstract

Background:

Management of pain and discomfort is important to make the postoperative period as pleasant as possible. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are traditionally prescribed; however, they are associated with numerous side effects. As a result, nutraceuticals such as curcumin are widely used for its well-known safety and medicinal values. Hence, the aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of a curcumin mucoadhesive film for postsurgical pain control.

Materials and Methods:

This was a split-mouth study, consisting of 15 systemically healthy patients with 30 sites, who were randomly allocated into test (curcumin mucoadhesive film) and control (placebo mucoadhesive film) groups using coin toss method. A questionnaire was given to patients to evaluate the postoperative pain and swelling and the number of rescue medications taken. Statistical analyses used were Friedman test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and McNemar's test.

Results:

No adverse effects were reported and healing was uneventful in all patients. The Numerical rating scale pain score showed significantly lesser pain at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 24 h in the test group. Significantly more number of analgesics was consumed in total in the control group than that in the test group.

Conclusion:

Within the limitations of this study, it may be concluded that curcumin mucoadhesive film showed promising results in reducing postoperative pain and swelling over a period of 1 week, hence showing its analgesic effect after periodontal surgeries.

Keywords: Analgesic, anti-inflammatory, chronic periodontitis, curcumin, mucoadhesive film, numerical rating scale, pain assessment, postoperative pain, swelling

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative pain is a very subjective emotion or sensation depending on various patient-related factors such as sex, psychological build-up of patients, fear, and apprehension[1] as well as operator-related factors such as poor handling of tissues, trauma, and poor infection control.[2] Periodontal postsurgical pain that lasts for 3 days, peaking at the first 12 h,[3] is considered normal and usually reduces after healing.[2]

The most common cause of postsurgical pain is the spread of inflammation or swelling at the surgical site.[4] It causes discomfort for a patient and affects their quality of life.[5] Therefore, management of pain and discomfort is important to make the postoperative period as pleasant as possible by following the pharmacological methods.

The administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) following periodontal flap surgeries is considered as the benchmark, due to its anti-inflammatory and analgesic actions[2,3,4] by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme which is responsible for the transformation of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins and thromboxanes and as a result suppresses pain.[6]

However, NSAIDs are associated with numerous side effects ranging from mild adverse effects to serious gastric problems (such as gastric bleeding or perforation), renal toxicity, and the risk of abnormal bleeding tendency due to the antiplatelet effect of these drugs. NSAIDs are also considered unsafe to use in pregnant and lactating women.[7] As a result, nutraceuticals (”nutrition” + “pharmaceuticals”) have gained much attention in recent times.

Curcumin or diferuloylmethane (1,7-bis-[4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl]-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione) is one such natural agent which has been characterized as the most active component of Curcuma longa (Turmeric), which is a popular kitchen spice in most Asian countries.[8]

Curcumin is well known for its anti-inflammatory,[9,10,11,12] antimicrobial,[13,14,15,16,17,18] antioxidant,[19,20] and wound-healing properties.[18,21,22] It has also demonstrated analgesic property in some animal studies[9,23,24,25] and some human studies in burn patients[26] and following laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[27]

Curcumin also has a good safety profile and is termed as a generally regarded as safe ingredient by the US Food and Drug Administration.[8] In addition to this, it is also highly economical, is easily available, and has a multitargeted mode of action on the various molecular signaling pathways, unlike NSAIDs.[28]

In spite of the promising biological effects, the clinical application of curcumin is still a challenge due to its poor bioavailability due to poor absorption, rapid metabolism, and rapid systemic elimination.[8]

To overcome these limitations, curcumin has also been studied in the form of local drug delivery agents such as gels,[29] mouth rinses,[30] subgingival irrigants,[31] and curcumin-incorporated collagen fibers,[32] which have shown to achieve a higher concentration in the oral cavity as compared to the oral administration.[33]

Mucoadhesive films are a form of local drug delivery system which employs the transmucosal route of drug delivery. This ensures maximum contact period of the desired concentration of a therapeutic agent at the desired site and better drug absorption.[34]

No previous human studies have been done that assessed the analgesic property of curcumin in the form of a mucoadhesive film after periodontal surgeries. Hence, keeping all these data in mind, the aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of mucoadhesive film-containing curcumin in postsurgical pain management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Based on a study by Rajeswari et al.,[35] the power of the study was 80% and the required sample size was calculated as 13, which was rounded off to 15 patients with bilateral moderate or advanced periodontitis.

Fifteen systemically healthy individuals, both males and females, within the age group of 30–55 years, who had bilaterally symmetrical, moderate or advanced periodontitis in at least one arch, were selected for this study from the outpatient department, by simple purposive sampling from October 2017 to August 2018.

Of the 15 patients in this split-mouth study, two bilaterally symmetrical contralateral sites in each patient (30 sites in total) were selected for the study and were randomly allocated into test and control sites by coin toss method. Each patient had a test and contralateral a control site.

The inclusion criteria were bilaterally symmetrical type and extent of surgical therapy indicated, minimum of ≥20 teeth, periodontal probing depth ≥5 mm, and consenting patients who were cooperative.

The following were the exclusion criteria: pregnant/lactating women, patients on antibiotic or NSAIDs therapy in the previous 6 months, patients who had undertaken any periodontal therapy in the past 6 months, smokers, patients who were medically compromised or under therapeutic regimen that may alter the probability of tissue healing, and patients who were known or suspected to be allergic to curcumin.

This split-mouth, placebo-controlled study was approved by the institutional review board of the institution and also registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI/2017/11/010594).

Informed consents were signed by all patients before participating in this study.

Preparation of the mucoadhesive films

The mucoadhesive films were formulated and were optimized for various formulation ingredients before making the final batches of mucoadhesive films. Curcumin mucoadhesive films of 0.5% [Figure 1] and placebo mucoadhesive films [Figure 2] were prepared using solvent casting technique.[34] All the steps were carried out in a sterile environment. The films were cut into smaller rectangular strips of 4–5 mm width and the length depending on the extent of flap surgery in each patient. Ultraviolet sterilization was done in small packets. The mechanical and physiochemical characterization of the films was done by performing various tests to assess the thickness and weight uniformity, folding endurance, swelling index, pH, and drug content of the films.

Figure 1.

Curcumin mucoadhesive film in a sterilization packet

Figure 2.

Placebo mucoadhesive film

Presurgical procedure

The patients who had fulfilled the inclusion criteria and who had willingly given consent underwent routine hematological investigations and Phase 1 therapy and were then recalled after 1 month to evaluate the response to Phase I therapy. If maintenance was found to be satisfactory, patients were scheduled for surgery.

Surgical procedure

After following the aseptic protocol, the defect sites were anesthetized using 2% lignocaine with 1:80000 adrenaline using block and infiltration techniques. In all patients, Kirkland flap surgery[36] was performed. After suturing, the preformed films were adapted on the gingiva in the test and control sites, respectively [Figures 3 and 4], over which periodontal pack (Coe-Pack) was placed. Antibiotics (amoxicillin 500 mg) were prescribed 8 hourly for 5 days and analgesics (aceclofenac 100 mg) had to be taken as a rescue drug only if it was necessary on a “need-to-treat” basis.

Figure 3.

Curcumin film placed over gingiva after suturing

Figure 4.

Placebo film placed over gingiva after suturing

Postoperative care

Postoperative instructions were given to all the patients, and they were instructed to report back after 7 days. Immediately after the placement of the film, manifestations of any allergic reaction were observed for the first 1 h postsurgery, subsequent to which patients were discharged.

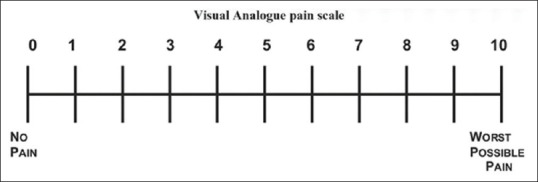

Questionnaire

A questionnaire[37] was given to the patients after surgery to evaluate the postoperative pain (numeric rating scale [NRS] for pain [NRSp]), swelling at the site of surgery (NRS for internal swelling [NRSis]), and facial swelling (NRS for facial swelling [NRSfs]) at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 24, and 48 h after surgery in both the groups. NRS-11[38] was used to measure pain and swelling. It consisted of a 10-cm line with both ends closed by vertical lines which correspond to no pain and maximum pain and a 10-point NRS. The patients were asked to give a score to their pain/swelling ranging from 0 (no pain/swelling) to 10 (maximum pain/swelling) on the NRS line [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Numerical rating scale-11 used for pain and swelling

Patients were also asked to mention in the questionnaire if they had to take a pain killer. They were instructed to make a note of the date and time of consumption and the total number of analgesics (rescue medications) taken over 5 days. All patients were prescribed 100 mg aceclofenac as painkiller to minimize bias.

Follow-ups

At 7 days following surgeries, the dressing and sutures were removed and the patients were enquired regarding discomfort, pain, and sensitivity. The completed questionnaire was collected at the end of 1 week.

Statistical analysis

The results obtained from these parameters were subjected to statistical analysis. Data were entered in Microsoft Excel and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Science software (SPSS, Ver. 24.0.0, IBM, New York, United States).

The results were averaged (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) for continuous data and are presented in tables and graphs. Parameters were analyzed using nonparametric tests, as the values did not follow a normal distribution, such as Friedman test for intragroup comparison of parameters at different time intervals, Wilcoxon signed-rank test for intergroup comparison of parameters, and McNemar's test to analyze the dichotomous variables.

RESULTS

The present study is a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial with a split-mouth design, to evaluate the analgesic property of curcumin-containing mucoadhesive film after periodontal surgeries over 1 week.

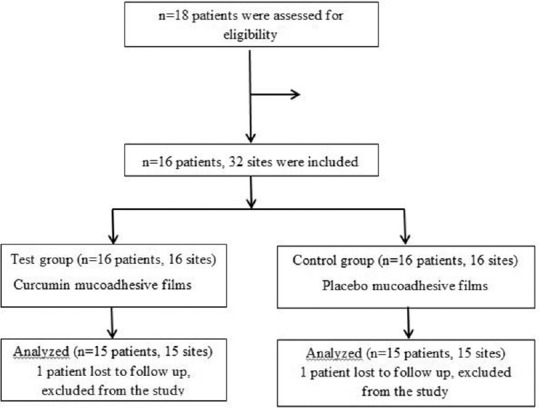

A total of 15 patients, 30 sites (test sites = 15, control sites = 15), were taken up in this split-mouth study.[Figure 6] The mean ± SD age of subjects was 42.27 ± 6.55 years including a total of 8 females (53.3%) and 7 males (46.7%) in this study. The outcome variable was self-reported pain and swelling based on the NRS and number of analgesics used during 5 days postoperative period. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and was denoted by *.

Figure 6.

Flowchart for sample selection

None of the patients reported any allergic reactions, discoloration of teeth, or alteration of taste and healing was uneventful in all patients.

The number of subjects with bilaterally symmetrical mandibular defects was significantly more than patients with bilaterally symmetrical maxillary defects [Table 1]. However, the quadrant number that was randomly selected as test and control sites showed no statistical significance [Table 2].

Table 1.

Maxillary or mandibular sites

| Number of sites | Jaw | Total, n (%) | Chi-square test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maxillary, n (%) | Mandibular, n (%) | χ2 | P | ||

| 0 | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) | 15 (50.0) | 6.53 | 0.01* |

| 2 | 4 (26.7) | 11 (73.3) | 15 (50.0) | ||

*P<0.05 statistically significant; P>0.05 (NS). NS – Nonsignificant; P – level of marginal significance

Table 2.

Quadrant number of test and control sites

| Quadrant number | Groups | Total, n (%) | Fisher’s exact test, P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test, n (%) | Control, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 4 (13.3) | 0.77 (NS) |

| 2 | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 4 (13.3) | |

| 3 | 4 (26.7) | 7 (46.7) | 11 (36.7) | |

| 4 | 7 (46.7) | 4 (26.7) | 11 (36.7) | |

*P<0.05 statistically significant; P>0.05 (NS). NS – Nonsignificant; P – level of marginal significance

Intragroup comparison of NRSp, NRSis, and NRSfs and number of analgesics consumed in test and control groups at different time intervals was done using the Friedman test and showed statistically significant decrease in both the groups (P < 0.05).

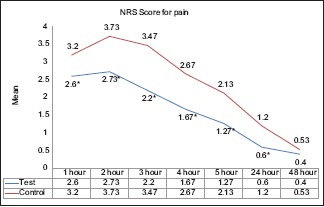

According to Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the intergroup comparison of NRSp between test and control groups showed statistically significant results at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 24 h in the test group than the control group (P < 0.05) but not at 48 h [Table 3 and Graph 1].

Table 3.

Intergroup comparison of numeric rating scale score for pain between test and control group at different time intervals

| n | Mean±SD | Range | Median (Q1-Q3) | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | P | |||||

| 1 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 2.60±2.03 | 0-7 | 3 (1-4) | −2.08 | 0.04* |

| Control | 15 | 3.20±2.31 | 0-7 | 3 (1-5) | ||

| 2 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 2.73±1.62 | 0-5 | 3 (1-4) | −2.80 | 0.005* |

| Control | 15 | 3.73±2.09 | 1-8 | 3 (2-5) | ||

| 3 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 2.20±1.37 | 0-4 | 2 (1-3) | −2.99 | 0.003* |

| Control | 15 | 3.47±1.64 | 1-6 | 3 (2-5) | ||

| 4 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 1.67±1.45 | 0-4 | 2 (0-3) | −2.97 | 0.003* |

| Control | 15 | 2.67±1.84 | 0-6 | 3 (1-4) | ||

| 5 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 1.27±1.34 | 0-4 | 1 (0-2) | −2.75 | 0.006* |

| Control | 15 | 2.13±1.64 | 0-4 | 2 (0-4) | ||

| 24 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.60±0.99 | 0-3 | 0 (0-1) | −2.12 | 0.03* |

| Control | 15 | 1.20±1.21 | 0-4 | 1 (0-2) | ||

| 48 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.40±0.74 | 0-2 | 0 (0-1) | −1.41 | 0.16 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.53±0.83 | 0-2 | 0 (0-1) | ||

*P<0.05 statistically significant; P>0.05 (NS). n – Total number of subjects; Q1 – Median in the lower half of the data; Q3 – Median for the upper half of data; Z – Confidence interval=1.96; NS – Nonsignificant; SD – Standard deviation; P – level of marginal significance

Graph 1.

Intergroup and intragroup comparison of numeric rating scale scores for pain at different time intervals; *P < 0.05 – Statistically significant

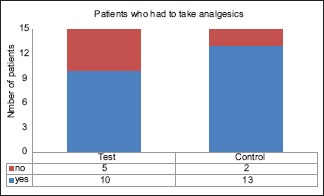

On the 4th and 5th postsurgical days, none of the patients consumed any analgesics; hence, the analysis was limited to the 3rd day. The number of analgesics taken between test and control groups was found to be statistically significant at day 1 and day 2 in the test group [Table 4].

Table 4.

Intergroup comparison of number of analgesics taken between test and control group at different time intervals

| Time | Group | n | Mean±SD | Range | Median (Q1-Q3) | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | P | ||||||

| Day 1 | Test | 15 | 1±0.85 | 0-2 | 1 (0-2) | −2.65 | 0.008* |

| Control | 15 | 1.47±0.74 | 0-2 | 2 (1-2) | |||

| Day 2 | Test | 15 | 0.33±0.62 | 0-2 | 0 (0-1) | −2.45 | 0.01* |

| Control | 15 | 0.73±0.80 | 0-2 | 1 (0-1) | |||

| Day 3 | Test | 15 | 0.07±0.26 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | −1.63 | 0.10 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.33±0.62 | 0-2 | 0 (0-1) | |||

| Day 4 | Test | 15 | 0±0 | 0-0 | 0 (0-0) | 0.00 | 1.00 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0±0 | 0-0 | 0 (0-0) | |||

| Day 5 | Test | 15 | 0±0 | 0-0 | 0 (0-0) | 0.00 | 1.00 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0±0 | 0-0 | 0 (0-0) | |||

*P<0.05 statistically significant; P>0.05 (NS). NS – Nonsignificant; n – Total number of subjects; SD – Standard deviation; Q1 – Median in the lower half of the data; Q3 – Median for the upper half of data; Z – Confidence interval=1.96; P – level of marginal significance

The McNemar's test, used for dichotomous variables, showed lesser number of patients who consumed analgesics in the test group. The intergroup comparison showed that 2 (13.3%) subjects did not take analgesics in both groups and 3 (30.0%) subjects took analgesics in the control group but not in the test group. However, these results were not statistically significant [Graph 2]. Nevertheless, the total number of analgesics consumed by the test group was significantly higher than the control group [Table 5].

Graph 2.

Intergroup comparison of analgesics taken between test and control groups

Table 5.

Intergroup comparison of total number of analgesics taken between test and control group

| n | Mean±SD | Range | Median (Q1-Q3) | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | P | |||||

| Test | 15 | 1.4±1.45 | 0-4 | 1 (0-3) | −3.03 | 0.002* |

| Control | 15 | 2.47±1.89 | 0-6 | 2 (1-4) | ||

*P<0.05 statistically significant; P>0.05 (NS). NS – Nonsignificant; n – Total number of subjects; SD – Standard deviation; Q1 – Median in the lower half of the data; Q3 – Median for the upper half of data; Z – Confidence interval=1.96; P – level of marginal significance

Intergroup comparison of NRSis score between test and control groups only at 2 and 3 h was significantly lower in the test group than the control group (P < 0.05) [Table 6]. Similarly, the intragroup comparison of NRSfs scores was significantly lesser in the test group than the control group only at 2 h [Table 7].

Table 6.

Intergroup comparison of numeric rating scale score for internal swelling between test and control group at different time intervals

| n | Mean±SD | Range | Median (Q1-Q3) | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | P | |||||

| 1 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.80±1.08 | 0-3 | 0 (0-1) | −1.73 | 0.08 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 1.00±1.20 | 0-4 | 1 (0-1) | ||

| 2 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.73±0.96 | 0-3 | 0 (0-1) | −2 | 0.04* |

| Control | 15 | 1.00±1.07 | 0-3 | 1 (0-2) | ||

| 3 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.73±0.88 | 0-3 | 1 (0-1) | −2 | 0.04* |

| Control | 15 | 1.00±1.00 | 0-3 | 1 (0-1) | ||

| 4 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.47±0.74 | 0-2 | 0 (0-1) | −1.34 | 0.18 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.67±0.82 | 0-3 | 1 (0-1) | ||

| 5 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.27±0.46 | 0-1 | 0 (0-1) | −1.73 | 0.08 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.47±0.64 | 0-2 | 0 (0-1) | ||

| 24 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.07±0.26 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | −1.41 | 0.16 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.20±0.41 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | ||

| 48 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.07±0.26 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | −1 | 0.32 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.13±0.35 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | ||

*P<0.05 statistically significant; P>0.05 (NS). NS – Nonsignificant; n – Total number of subjects; SD – Standard deviation; Q1 – Median in the lower half of the data; Q3 – Median for the upper half of data; Z – Confidence interval=1.96; P – level of marginal significance

Table 7.

Intergroup comparison of numeric rating scale score for facial swelling between test and control group at different time intervals

| n | Mean±SD | Range | Median (Q1-Q3) | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | P | |||||

| 1 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.47±0.74 | 0-2 | 0 (0-1) | −1.41 | 0.16 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.60±0.99 | 0-3 | 0 (0-1) | ||

| 2 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.40±0.63 | 0-2 | 0 (0-1) | −2 | 0.04* |

| Control | 15 | 0.67±0.98 | 0-3 | 0 (0-1) | ||

| 3 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.40±0.83 | 0-3 | 0 (0-1) | −1.41 | 0.16 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.53±0.99 | 0-3 | 0 (0-1) | ||

| 4 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.20±0.56 | 0-2 | 0 (0-0) | −1.41 | 0.16 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.33±0.62 | 0-2 | 0 (0-1) | ||

| 5 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.13±0.35 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | −1 | 0.32 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.20±0.41 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | ||

| 24 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.07±0.26 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | 0 | 1.00 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.07±0.26 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | ||

| 48 h | ||||||

| Test | 15 | 0.07±0.26 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | 0 | 1.00 (NS) |

| Control | 15 | 0.07±0.26 | 0-1 | 0 (0-0) | ||

*P<0.05 statistically significant; P>0.05 (NS). NS – Nonsignificant; n – Total number of subjects; SD – Standard deviation; Q1 – Median in the lower half of the data; Q3 – Median for the upper half of data; Z – Confidence interval=1.96; P – level of marginal significance

DISCUSSION

Pain is a subjective parameter and its perception varies from individual to individual. It is the duty of a physician to ensure a pleasant postsurgical period for the patients.[2]

In this study, curcumin was delivered locally in the form of mucoadhesive films as the transmucosal route of administration overcomes the drawbacks of systemic administration of curcumin, such as poor bioavailability due to poor absorption, rapid metabolism, and rapid systemic elimination;[8] it also ensures higher concentration directly at the required site for a longer period of time.[35]

The curcumin films were prepared with a concentration of 0.5% based on the results of a study by Sjahruddin et al.,[39] which showed a significant difference in the administration of curcumin 0.5%, on the diameter of the wound before and after 3 days, which is characterized by reduced size of the diameter of the wound.

Various tests were performed for the mechanical and physiochemical characterization of the curcumin films. The average thickness and weight of the films were 316 ± 41.7 μm and 26.4 ± 3.19 mg, respectively, with a neutral pH of 7.05. It also showed good results for folding endurance with an average of 370.4. It had a relatively good swelling index of 25.4% as a higher swelling value would have resulted in increased surface area which would have resulted in uncontrollable release of the drug. Further, higher swelling could bring about patient discomfort as it would occupy a larger space in the oral cavity, thus causing dislodgement of the film.[40] The results showed that the film had desirable characteristics in terms of weight, thickness, swelling index, drug content, folding endurance, and pH. However, the drug release pattern of the film was not evaluated and further studies are required using a curcumin film with a known drug release pattern using different concentrations.

The mean age of the patients in this study was 42.27 ± 6.55 years of which 8 were females and 7 were males. According to recent findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, half of adults aged 30 or older have periodontitis and severity of bone defects increases with age.[40] No significant difference was observed between the prevalence in males and females in this study as was also implied by Indurkar and Verma[41] and Nielsen et al.[42]

A split-mouth design was employed in this study in which contralateral, bilaterally symmetrical, moderate or advanced defects were chosen. This study design was selected to minimize the subjective errors as subjective parameters such as pain, swelling, and consumption of analgesics for pain relief vary from person to person. The inflammatory response and wound-healing activities also depend on patient-related factors.[43] A similar study design was employed by Moghadam et al.[1] and Mishra et al.[4] for comparison of postsurgical pain management between test and control groups.

The films were placed along the flap margins after suturing to ensure release of curcumin directly to the site of injury. This was followed by the placement of a noneugenol periodontal pack (Coe-Pack™). A periodontal pack secures the film in its position to ensure maximum contact time, while protecting the wound from mechanical trauma, food lodgment, and root hypersensitivity following the first few hours after surgery.

Postoperative healing was uneventful in all patients, and no adverse side effects were reported during or after the procedure in both the groups. The patch was found to be compliant as patients did not report any discomfort, change in taste, or discoloration of teeth following the placement of curcumin film.

A questionnaire was designed which was adapted from the questionnaire used by Hagenaars et al.[37] to evaluate the pain and swelling at the site of surgery at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 24, and 48 h after surgery in both the groups. These time intervals were selected based on the results of a study by Rajeswari et al.,[35] who evaluated periodontal postoperative pain control using meloxicam mucoadhesive films.

In this study, NRS score was used as opposed to visual analog scale (VAS) because NRS had better compliance in 15 of 19 studies and were the recommended tool in 11 studies on the basis of higher compliance rates, better responsiveness and ease of use, and good applicability relative to VAS.[44,45]

The NRSp scores showed significant results between the test and control groups at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 24 h intervals (P < 0.05).

Of 15 patients, two did not take any analgesics in both test and control groups. Three patients took analgesics in the control group but not in the test group, and the rest took analgesics after both test and control surgeries. However, these results were not statistically significant.

The intragroup comparison of the number of analgesics taken at different time intervals showed statistically significant results between test and control groups on day 1 and day 2 (P < 0.05) These results suggest an analgesic effect of curcumin.

There are no similar studies to compare owing to the lack of literature on intraoral human studies using curcumin to evaluate the efficacy of the postoperative pain control. However, there are some other systemic studies where the analgesic property of curcumin was earlier demonstrated by Cheppudira et al.[26] to treat pain in burns patients and showed a significant relief of pain. Agarwal et al.[27] administered curcumin systemically and showed its ability to control postoperative pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

There are three proposed mechanisms of action of curcumin in pain control.

First, like NSAIDs, curcumin is said to inhibit the COX pathways in human colon cancer cells and thus suppresses pain, by Menon and Sudheer.[9]

Second, curcumin is shown to have an antagonizing effect on transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 ion channels.[24]

Another possible mechanism of analgesic action of curcumin is by the activation of potassium ATP channels. Hence, curcumin may be directly stimulating potassium ATP channels, activating Gi/o proteins, stimulating the particulate form of guanylyl cyclase, or acting through the hydrogen sulfide-KATP channel pathway, thus producing an analgesic action.[25]

In this study, the NRSis and NRSfs scores showed significantly lesser swelling in the test group at 2 and 3 h, and 2 h respectively. These results are on account of the anti-inflammatory property of curcumin.

Studies by Muglikar et al.,[30] Waghmare et al.,[46] Suhag et al.,[47] Gottumukkala et al.,[31] and Behal et al.[29] support the anti-inflammatory property of curcumin by showing improvement in the periodontal clinical parameters, such as plaque and gingival indices, pocket probing depth, and clinical attachment level, after using curcumin in the form of gels, mouth rinses, subgingival irrigants, collagen sponges, etc., as an adjunct to scaling and root planing.

The main mechanism that is common to anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects is by the inhibition of COX pathway. Pulikkotil and Nath[48] are the only ones who evaluated the effect of curcumin oral gel on experimental gingivitis by comparing the levels of IL-1β and chemokine ligand 28 at baseline and 29 days, showing its anti-inflammatory mechanism of action on a molecular level in gingivitis in humans. No studies are reported that assessed the effect of curcumin on postoperative facial or internal swelling after periodontal surgery.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of a curcumin mucoadhesive film in the periodontal postsurgical pain control by evaluating patient-reported postoperative pain and swelling and the number of analgesics (rescue medications) consumed.

The positive point in this study is that curcumin was administered locally in the form of mucoadhesive films at the site of surgery which was convenient, comfortable, and patient-friendly.

Pain and swelling are two of the five cardinal signs of inflammation, and thus, it is safe to suggest that curcumin has an anti-inflammatory effect.

However, further long-term studies including histological analysis, microbiological analysis, and investigation of inflammatory mediator levels after the application of curcumin films on periodontal flap surgery wounds are required. The most effective concentrations and ways to increase the substantivity and control the curcumin release patterns must also be determined to assess qualities such as low daily dosage and longer half-life at varying concentrations.

CONCLUSION

Hence, within the limitations of this study, curcumin-containing films showed better analgesic property and anti-inflammatory effect as compared to the placebo film. Thus, curcumin mucoadhesive film is a promising phytochemical drug delivery agent that can emerge as a commercially available medication for postoperative relief of pain and discomfort.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moghadam ET, Sargolzaie N, Rajabi O, Arab H, Moeintaghavi A. Analgesic efficacy of Aloe vera and green tea mouthwash after periodontal pocket reduction surgery: A randomized split-mouth clinical trial. J Dent Sch. 2016;34:176–85. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirmani M, Trivedi H, Bey A, Sharma VK. Post – Operative complications of periodontal surgery. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2016;3:1285–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seymour RA, Blair GS, Wyatt FA. Post-operative dental pain and analgesic efficacy. Br J Oral Surg. 1983;21:290–7. doi: 10.1016/0007-117x(83)90017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mishra A, Amalakara J, Avula H, Reddy K. Effect of diclofenac mouthwash on postoperative pain after periodontal surgery. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:ZC24–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/22165.9658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt VP, McHugh K. Factors influencing patient loyalty to dentist and dental practice. Br Dent J. 1997;183:365–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poveda Roda R, Bagán JV, Jiménez Soriano Y, Gallud Romero L. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in dental practice. A review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:E10–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gor AP, Saksena M. Adverse drug reactions of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in orthopedic patients. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2:26–9. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.77104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liju VB, Jeena K, Kumar D, Maliakel B, Kuttan R, Im K. Function curcumagalactomannosides as a dietary ingredient. Food Funct. 2015;6:276–86. doi: 10.1039/c4fo00749b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menon VP, Sudheer AR. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:105–25. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shishodia S, Amin HM, Lai R, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) inhibits constitutive NF-kappaB activation, induces G1/S arrest, suppresses proliferation, and induces apoptosis in mantle cell lymphoma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:700–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guimarães MR, Coimbra LS, de Aquino SG, Spolidorio LC, Kirkwood KL, Rossa C, Jr, et al. Potent anti-inflammatory effects of systemically administered curcumin modulate periodontal disease in vivo . J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:269–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2010.01342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawamori T, Rao CV, Seibert K, Reddy BS. Chemopreventive activity of celecoxib, a specific cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, against colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1998;58:409–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta SC, Patchva S, Aggarwal BB. Therapeutic roles of curcumin: Lessons learned from clinical trials. AAPS J. 2013;15:195–218. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9432-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawhavinit OA, Kongkathip N, Kongkathip B. Antimicrobial activity of curcuminoids from Curcuma longa L. on pathogenic bacteria of shrimp and chicken. Kasetsart J Nat Sci. 2010;44:364–71. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Negi PS, Jayaprakasha GK, Jagan Mohan Rao L, Sakariah KK. Antibacterial activity of turmeric oil: A byproduct from curcumin manufacture. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:4297–300. doi: 10.1021/jf990308d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen D, Shien J, Tiley L, Chiou S, Wang S, Chang T, et al. Curcumin inhibits influenza virus infection and haemagglutination activity. Food Chem. 2010;119:1346–51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Divya CS, Pillai MR. Antitumor action of curcumin in human papillomavirus associated cells involves downregulation of viral oncogenes, prevention of NFkB and AP-1 translocation, and modulation of apoptosis. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:320–32. doi: 10.1002/mc.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ungphaiboon S, Tanomjit S, Pechnoi S, Supreedee S, Pranee R, Itharat A. Study on antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of turmeric clear liquid soap for wound treatment of HIV patients. Int Inf Syst Agric Sci Technol. 2005;27:569–78. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaul S, Krishnakantha TP. Influence of retinol deficiency and curcumin/turmeric feeding on tissue microsomal membrane lipid peroxidation and fatty acids in rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;175:43–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1006829010327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohly HH, Taylor A, Angel MF, Salahudeen AK. Effect of turmeric, turmerin and curcumin on H2O2-induced renal epithelial (LLC-PK1) cell injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akbik D, Ghadiri M, Chrzanowski W, Rohanizadeh R. Curcumin as a wound healing agent. Life Sci. 2014;116:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sidhu GS, Singh AK, Thaloor D, Banaudha KK, Patnaik GK, Srimal RC, et al. Enhancement of wound healing by curcumin in animals. Wound Repair Regen. 1998;6:167–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.1998.60211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Q, Sun Y, Yun X, Ou Y, Zhang W, Li JX, et al. Antinociceptive effects of curcumin in a rat model of postoperative pain. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4932. doi: 10.1038/srep04932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JY, Shin TJ, Choi JM, Seo KS, Kim HJ, Yoon TG, et al. Antinociceptive curcuminoid, KMS4034, effects on inflammatory and neuropathic pain likely via modulating TRPV1 in mice. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:667–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Paz-Campos MA, Chávez-Piña AE, Ortiz MI, Castañeda-Hernández G. Evidence for the participation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in the antinociceptive effect of curcumin. Korean J Pain. 2012;25:221–7. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2012.25.4.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheppudira B, Fowler M, McGhee L, Greer A, Mares A, Petz L, et al. Curcumin: A novel therapeutic for burn pain and wound healing. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22:1295–303. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.825249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agarwal KA, Tripathi CD, Agarwal BB, Saluja S. Efficacy of turmeric (curcumin) in pain and postoperative fatigue after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3805–10. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1793-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keith CT, Borisy AA, Stockwell BR. Multicomponent therapeutics for networked systems. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:71–8. doi: 10.1038/nrd1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behal R, Mali AM, Gilda SS, Paradkar AR. Evaluation of local drug-delivery system containing 2% whole turmeric gel used as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in chronic periodontitis: A clinical and microbiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:35–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.82264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muglikar S, Patil KC, Shivswami S, Hegde R. Efficacy of curcumin in the treatment of chronic gingivitis: A pilot study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2013;11:81–6. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a29379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottumukkala SN, Koneru S, Mannem S, Mandalapu N. Effectiveness of sub gingival irrigation of an indigenous 1% curcumin solution on clinical and microbiological parameters in chronic periodontitis patients: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4:186–91. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.114874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gopinath D, Ahmed MR, Gomathi K, Chitra K, Sehgal PK, Jayakumar R. Dermal wound healing processes with curcumin incorporated collagen films. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1911–7. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00625-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ps J, Nath S, Os S. Use of curcumin in periodontal inflammation. Interdiscip J Microinflamm. 2014;1:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munot NM, Gujar KN. Orodental delivery systems: An overview. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;5:74–83. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajeswari SR, Gowda TM, Kumar TA, Thimmasetty J, Mehta DS. An appraisal of innovative meloxicam mucoadhesive films for periodontal postsurgical pain control: A double-blinded, randomized clinical trial of effectiveness. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6:299–304. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.161857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirkland O. Modified flap operation in surgical treatment of periodontoclasia, May 23, 1932. J Am Dent Assoc. 1932;19:1918–21. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hagenaars S, Louwerse PH, Timmerman MF, Van der Velden U, Van der Weijden GA. Soft-tissue wound healing following periodontal surgery and emdogain application. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:850–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Griensven H, Strong J, Unruh AM. Pain: A Textbook for Health Professionals. 2; 429 Elsevier. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sjahruddin AD, Irawananwar A, Tabri F, Djawad K, Daud D, Alam G. The effect of curcumin on the acute wound healing of mice. Am J Clin Exp Med. 2015;3:189–93. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel RS, Poddar SS. Development and characterization of mucoadhesive buccal patches of salbutamol sulphate. Curr Drug Deliv. 2009;6:140–4. doi: 10.2174/156720109787048177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Indurkar MS, Verma R. Evaluation of the prevalence and distribution of bone defects associated with chronic periodontitis using conebeam computed tomography: A radiographic study. J Interdiscip Dent. 2016;6:104–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nielsen IM, Glavind L, Karring T. Interproximal periodontal intrabony defects. Prevalence, localization and etiological factors. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:187–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1980.tb01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–29. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bijur PE, Latimer CT, Gallagher EJ. Validation of a verbally administered numerical rating scale of acute pain for use in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:390–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, et al. Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: A systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:1073–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waghmare PF, Chaudhari AU, Karhadkar VM, Jamkhande AS. Comparative evaluation of turmeric and chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash in prevention of plaque formation and gingivitis: A clinical and microbiological study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2011;12:221–4. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suhag A, Dixit J, Dhan P. Role of curcumin as a subgingival irrigant: A pilot study. PERIO Periodontal Pract Today. 2007;2:115–21. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pulikkotil SJ, Nath S. Effects of curcumin on crevicular levels of IL-1β and CCL28 in experimental gingivitis. Aust Dent J. 2015;60:317–27. doi: 10.1111/adj.12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]