ABSTRACT

Here, we show that cells expressing the adherens junction protein nectin-1 capture nectin-4-containing membranes from the surface of adjacent cells in a trans-endocytosis process. We find that internalized nectin-1–nectin-4 complexes follow the endocytic pathway. The nectin-1 cytoplasmic tail controls transfer: its deletion prevents trans-endocytosis, while its exchange with the nectin-4 tail reverses transfer direction. Nectin-1-expressing cells acquire dye-labeled cytoplasmic proteins synchronously with nectin-4, a process most active during cell adhesion. Some cytoplasmic cargo remains functional after transfer, as demonstrated with encapsidated genomes of measles virus (MeV). This virus uses nectin-4, but not nectin-1, as a receptor. Epithelial cells expressing nectin-4, but not those expressing another MeV receptor in its place, can transfer infection to nectin-1-expressing primary neurons. Thus, this newly discovered process can move cytoplasmic cargo, including infectious material, from epithelial cells to neurons. We name the process nectin-elicited cytoplasm transfer (NECT). NECT-related trans-endocytosis processes may be exploited by pathogens to extend tropism.

This article has an associated First Person interview with the first author of the paper.

KEY WORDS: Cell adhesion, Nectin, Cell communication, Trans-endocytosis, Cytoplasm transfer, Neuronal entry, Virus receptor, Measles virsus

Highlighted Article: Characterization of a newly discovered nectin trans-endocytosis processes that not only transfers cell surface proteins but also cytoplasmic proteins. It can also transfer measles virus ribonucleocapsids, extending tropism to neurons.

INTRODUCTION

Receptor-mediated transfer of specific transmembrane proteins between cells was initially described in Drosophila retinal development, where the Bride of sevenless protein is internalized by the Sevenless tyrosine kinase receptor (Cagan et al., 1992). Transfer of specific transmembrane proteins also occurs during tissue patterning in embryonic development of higher vertebrates, during epithelial cell movement and at the immune synapse (Gaitanos et al., 2016; Hudrisier et al., 2001; Marston et al., 2003; Matsuda et al., 2004; Qureshi et al., 2011). At the immune synapse, the CTLA-4 protein captures its ligands CD80 and CD86 from donor cells by a process of trans-endocytosis; after removal, these ligands are degraded inside the acceptor cell, resulting in impaired co-stimulation (Qureshi et al., 2011).

We have discovered a process eliciting transfer of not only transmembrane proteins but also of cytoplasmic cargo between cells expressing different nectins. Nectins mediate Ca2+-independent cell–cell adhesion in many vertebrate tissues, including epithelia, endothelia and neural tissue (Rikitake et al., 2012; Takai et al., 2008). The nectin family of immunoglobulin-like transmembrane molecules comprises four members, nectin-1 (N1) to nectin-4 (N4). Nectin–nectin interactions have a defined heterophilic specificity pattern (Harrison et al., 2012). Nectins have roles in contact inhibition of cell movement and proliferation and, together with cadherins, form specific intercellular adhesive structures named adherens junctions (AJ) (Franke, 2009). Nectins and nectin-like proteins also serve as receptors for viruses (Campadelli-Fiume et al., 2000; Geraghty et al., 1998; Mateo et al., 2015; Mendelsohn et al., 1989). We use here measles virus (MeV) to characterize the newly discovered process.

MeV is an important pathogen: it caused 110,000 deaths worldwide in 2018 (Butler, 2015) (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles) mainly due to secondary infections facilitated by immunosuppression (Griffin, 2013; Mina et al., 2015). Receptors determine tropism and pathogenesis of MeV and the related animal morbilliviruses (Mateo et al., 2014a), which initially use the signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM, also known as SLAMF1 or CD150) to enter immune cells and cause immunosuppression (Tatsuo et al., 2000), and then N4 to infect the upper respiratory epithelia and to exit the host (Birch et al., 2013; Mateo et al., 2014b; Mühlebach et al., 2011; Noyce et al., 2011, 2013; Pratakpiriya et al., 2012). Since morbilliviruses also cause neurological diseases (Bellini et al., 2005; Cattaneo et al., 1988; da Fontoura Budaszewski and von Messling, 2016; Ludlow et al., 2015; Rudd et al., 2006), a neuronal receptor has been postulated but a consensus candidate has not emerged (Alves et al., 2015; Ehrengruber et al., 2002; Lawrence et al., 2000; Makhortova et al., 2007; Watanabe et al., 2015, 2019). With this in mind, we assessed whether the process we discovered can transfer MeV infections from N4-expressing epithelial cells to N1-expressing neurons. Indeed, N4-dependent infection transfer occurs.

RESULTS

N1-expressing epithelial cells take up N4

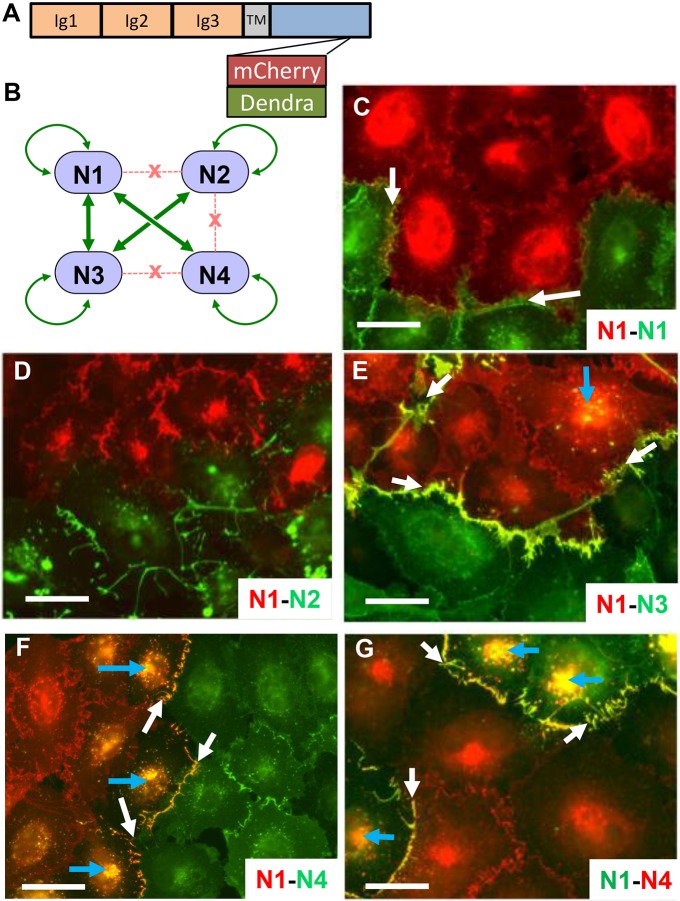

Nectins are type I transmembrane proteins whose ectodomains have three immunoglobulin-like domains followed by a single transmembrane region and a cytoplasmic region (Fig. 1A). Nectin–nectin interactions have a specific pattern (Harrison et al., 2012). For example, N1 interacts strongly with both nectin-3 (N3) and N4, weakly with itself, and does not interact with nectin-2 (N2) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, N4 only binds strongly to N1. To assess the consequences of these interactions for cell adhesion and AJ formation (Troyanovsky et al., 2015), we expressed N1–mCherry in A431D cells, an epithelial cell line that does not express the other major component of adherens junction, cadherins (Lewis et al., 1997), or endogenous nectin (Fig. S1A). We co-cultured the N1–mCherry-expressing cells with other A431D-derived cells expressing N1, N2, N3 or N4 proteins tagged with Dendra2.

Fig. 1.

Intercellular transfer of nectins. (A) Schematic showing the fluorescently tagged nectin constructs used here. Fluorescent tags were inserted upstream of the afadin-binding site located at the C-terminus of the cytoplasmic region (Kurita et al., 2011; Reymond et al., 2001). TM, transmembrane segment. (B) Interactions among nectins. Binding strengths were determined previously (Harrison et al., 2012). Gene name and main synonyms: N1, NECTIN1 (PVRL1, PRR1, HVEC, HigR, CD111); N2, NECTIN2 (PVRL2, PRR2, HVEB, CD112); N3, NECTIN3 (PVRL3, PRR3, CD113); N4, NECTIN4 (PVRL4, PRR4, LNIR). (C–F) Discovery of intercellular nectin transfer. N1–mCherry-expressing A431D cells co-cultured with A431D cells expressing N1–, N2–, N3– or N4–Dendra2, as indicated in the bottom right corners. Merged red and green signals are shown in yellow. White arrows point at colocalization signals at cell adhesion sites, blue arrows at internal colocalization signals. (G) Swap of fluorescent tags has no effect on direction of transfer. N1–Dendra2-expressing A431D cells co-cultured with N4-mCherry-expressing A431D cells. Scale bars: 40 µm.

Fig. 1E shows that when cells expressing N1 are co-cultured with cells expressing N3, the two proteins colocalize at adhesion sites (yellow signal, white arrows), the consequence of a strong interaction. Interestingly, limited colocalization also occurs within N1-expressing cells (yellow signal, blue arrow). In contrast, N1 does not colocalize with N2 (Fig. 1D) because these proteins do not interact. The weak N1–N1 interaction results in weak colocalization signals (Fig. 1C, yellow signals, white arrows).

The cellular localization of the N1–N4 complexes is most interesting; in addition to the strong signal at cell adhesion sites (Fig. 1F, white arrows) strong signals are documented within N1-expressing cells (Fig. 1F, blue arrows). Similar results are also seen when the fluorescent tags on N1 and N4 are switched (Fig. 1G, blue arrows); cells expressing N1, now tagged by green Dendra2, appear to contain mCherry-tagged N4 from co-cultured cells. Live video microscopy (Movie 1) documents how, after co-cultivation of N1–mCherry- and N4–Dendra2-expressing cells, the red cells uptake green fluorescence from certain adhesion sites, and yellow signals travel to an internal site.

While these observations suggest that N1-expressing cells uptake N1–N4 complexes, we considered the possibility that Dendra2, the N4 tag, could be transferred alone. However, immunoblot analyses of Fig. S1B,C document that chimeric N4–Dendra2 and chimeric N1–mCherry proteins are not cleaved. Thus, the fluorescent tags do report the cellular localization of the relevant nectins.

Since A431D cells do not express the other major component of adherens junction, cadherins, we assessed whether transfer of N1–N4 complexes occurs also in parental A431 cells, which express cadherins. Indeed, Fig. S1D-F demonstrate that uptake and internalization of N1–N4 complexes by N1-expressing cells also occurs in cadherin-functional A431 cells.

N1–N4 complexes follow the endocytic pathway

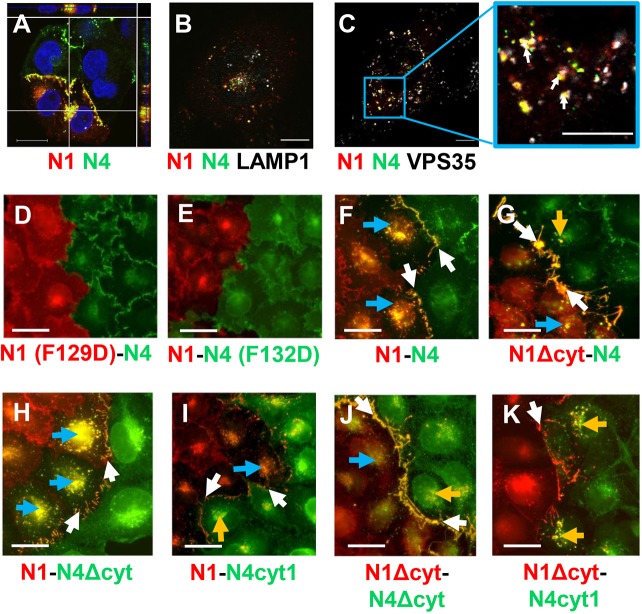

We then characterized the intracellular localization of the N1–N4 complexes. We first assessed whether, in analogy with trans-endocytosis processes, N1–N4 complexes follow the endocytic pathway. Confocal microscopy 3D analyses of Fig. 2A show that these complexes accumulate at a juxtanuclear location. Co-staining with the lysosomal marker LAMP-1 (white signals, white arrows) shows that complexes between N4–Dendra2 and N1–mCherry do not associate with LAMP1-positive structures (Fig. 2B). Co-staining with VPS35, a key component of the retromer-mediated endosomal protein-sorting machinery (Seaman et al., 2013), demonstrates association (Fig. 2C, white arrows). These results are consistent with endosomal uptake of N4-containing membrane patches by N1-expressing cells, and escape of the material from lysosomal degradation.

Fig. 2.

Cellular localization of N1–N4 complexes. (A) Confocal microscopy analyses of cellular localization of N1–N4 complexes. The z-dimension is shown on both the top and right-side bars. N4–Dendra2 (green) and N1–mCherry (red) cells were co-cultured for 24 h; nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Airyscan confocal microscopy of co-cultured N4 and N1 cells stained with anti-LAMP-1 antibody (white). (C) Airyscan confocal microscopy of co-cultured N4 and N1 cells stained with anti-VPS35 antibody. Association is pale yellow, denoted by white arrows. Scale bars: 20 µm. (D–K) Functions of the adhesive interface and of the cytoplasmic regions of nectins. All cell lines are derived from A431D cells. (D) Co-culture of adhesion mutant N1(F129D)–mCherry-expressing cells with N4–Dendra2-expressing cells. (E) Co-culture of N1–mCherry-expressing cells with adhesion mutant N4(F132D)–Dendra2-expressing cells. (G–K) Cells expressing N1 proteins with standard or altered cytoplasmic regions (all tagged with mCherry) co-cultured with cells expressing N4 proteins with standard or altered cytoplasmic regions (all tagged with Dendra2). The proteins expressed are indicated in the top-right corners. Color-coding: red, tagged with mCherry; green, tagged with Dendra2. Yellow: colocalization of red and green. Yellow signals in N1 cells, N4 cells and at the adherens junction are highlighted by blue, orange and white arrows, respectively. Scale bars: 40 µm.

The nectin adhesive interface is required for N4 uptake

Next, we sought to characterize interactions relevant for nectin uptake. We focused on the canonical adhesive interface, which is required for the nectin trans interaction (Harrison et al., 2012), and on the cytoplasmic domains, which are required for afadin binding and cytoskeletal interactions (Kurita et al., 2011; Reymond et al., 2001). As the exchange of a conserved phenylalanine residue centrally located in the adhesive surface of N2 for a charged residue (F136D mutation) interferes with recruitment of the mutant nectin to cell contacts (Harrison et al., 2012), we introduced analogous mutations in N1 (F129D) and N4 (F132D). As shown in Fig. 2D for the N1(F129D)–N4 interaction, and in Fig. 2E for the N1–N4(F132D) interaction, both mutations resulted in the loss of colocalization of N1 and N4 at adhesion sites. In addition, N4 transfer to N1-expressing cells was abolished. Thus, the nectin adhesive interface is required for uptake.

The N1 cytoplasmic region governs uptake

We then assessed whether the cytoplasmic regions of N1 and N4 influence uptake. First, we deleted the 141-residue N1 cytoplasmic region (Fig. S2). When cells expressing this N1Δcyt–mCherry protein mutant were co-cultured with cells expressing N4–Dendra2, colocalization of the two proteins remained strong at adhesion sites (Fig. 2G, white arrows). However, limited juxtanuclear colocalization was found in both N1Δcyt- and N4-expressing cells (Fig. 2G, blue or orange arrows, respectively), implying low levels of bi-directional nectin transfer. This is in contrast to co-cultures of cells expressing standard N1–mCherry and N4–Dendra2, which show extensive juxtanuclear nectin colocalization only in N1-expressing cells (Fig. 2F, blue arrows; see also Figs 1F and 2A). These data suggest that the N1 cytoplasmic region governs transfer.

To comparatively assess the relevance of the 140-residue N4 cytoplasmic region (Fig. S2) we deleted it (N4Δcyt), or replaced it with the corresponding region of N1 (N4cyt1). When cells expressing standard N1–mCherry protein were co-cultured with cells expressing N4Δcyt–Dendra2, colocalization of the two proteins was observed at adhesion sites (Fig. 2H, white arrows), and areas of juxtanuclear colocalization were extensive and occurred only in N1-expressing cells (Fig. 2H, blue arrows). Enhancement of uptake in N1-expressing cells suggests that the N4 cytoplasmic region counteracts the process, but only weakly. When cells expressing standard N1–mCherry protein were co-cultured with cells expressing the chimeric construct containing the ectodomain of N4 and the cytoplasmic region of N1 (N4cyt1–Dendra2), colocalization signals were weak both at cell adhesion sites and at juxtanuclear sites in both N1 and N4 cells (Fig. 2I, white, blue and orange arrows, respectively), consistent with some bi-directional transfer.

Co-culture of cells expressing N1 or N4 each with deleted cytoplasmic regions resulted in enhanced concentration of both mutants at adhesion sites, and weaker internalization in N1-expressing cells (Fig. 2J, white and blue arrows, respectively); weak juxtanuclear colocalization signals were also observed in N4 cells, indicative of some bi-directional transfer (Fig. 2J, orange arrow). Bi-directional transfer may reflect a weaker protein exchange process that is unmasked by cytoplasmic region deletions. These results indicate that the N1 cytoplasmic region is crucial for the directionality and efficiency of nectin transfer, and suggest that co-culture of N1Δcyt–mCherry cells with N4cyt1–Dendra2 cells may reverse uptake direction. Indeed, flow inversion occurred; yellow colocalization signals accumulated only in N4cyt1–Dendra2 cells (Fig. 2K, orange arrows).

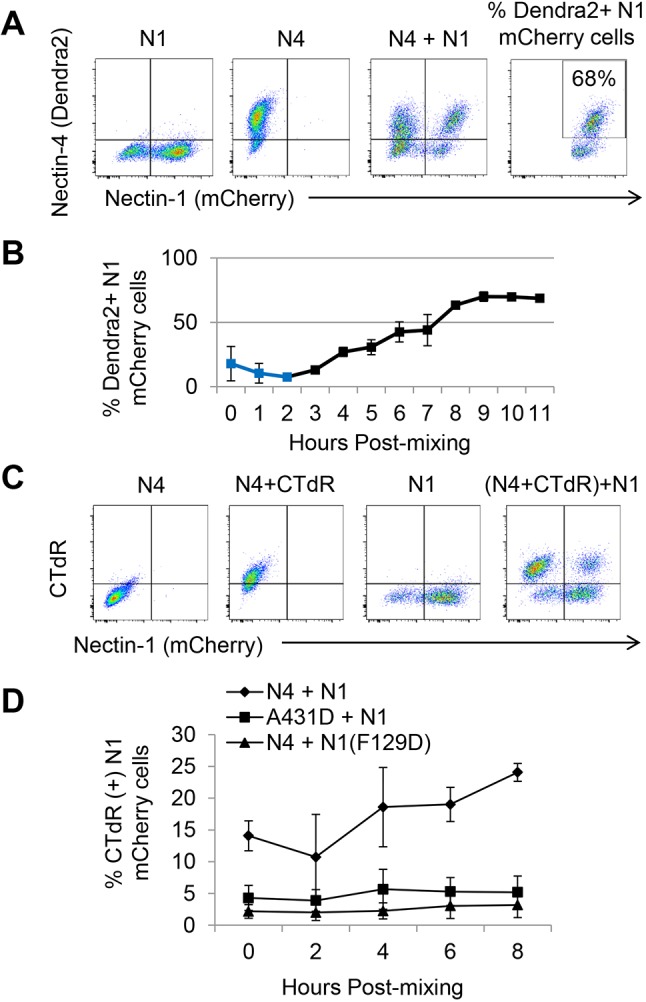

Synchronous uptake of N4 and cytoplasmic proteins

To further characterize this nectin-elicited process, we co-cultured N1–mCherry- with N4–Dendra2-expressing cells and analyzed dye transfer by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). Fig. 3A documents fluorescence emitted when the two cell types are cultured separately (first panel, N1–mCherry; second panel, N4–Dendra2) or co-cultured for 12 h (third panel). Comparison of the top- and bottom-right quadrants of the third panel indicates that more than half of N1-expressing cells were double positive.

Fig. 3.

Uptake kinetics of N4 and cytoplasmic proteins by N1-expressing cells. (A) Cell sorting analyses of N1- and N4-expressing cells. Fluorescence emitted by N1–mCherry cells (first panel), N4–Dendra2 cells (second panel), and by a 1:1 mixture of these two cells 12 h after co-culture (third panel). The fourth panel illustrates the gating strategy used to generate the graph shown in B. (B) One-hour interval kinetic analyses of N4–Dendra2 uptake by N1–mCherry cells. The mean±s.d. of three independent experiments, each one with three technical repeats, are shown. The primary data are in Fig. S3. Blue squares denote an early process causing double positivity in some cells. Since these cells are excluded by doublet discrimination, they are not canonical doublets. Since this effect reproducibly disappears at 2 h, it has no impact on data interpretation after that time point. (C) Cell sorting analysis of cytoplasmic protein uptake efficiency by N1-expressing cells. The first and third panels show N4–Dendra2 and N1–mCherry cells, respectively, without CTdR. The second panel shows CTdR staining of cytoplasmic proteins of N4–Dendra2-expressing cells. The fourth panel shows transfer of the CTdR-labeled proteins to N1–mCherry-expressing cells. The CTdR and mCherry emission spectra do not overlap (third panel). (D) Two-hour interval kinetic analyses of the percentage of N1–mCherry cells becoming CTdR positive. The mean±s.d. of three independent experiments, each one with three technical repeats, are shown. The primary data are in Fig. S4.

We then sought to quantify N4 uptake, and to determine its kinetics. The rightmost panel in Fig. 3A shows a representative gate used for quantification. Fig. 3B shows a FACS-based kinetic analysis of N4 uptake at 1 h intervals with the average and standard deviation of the three independent experiments. Fig. S3 shows two of these experiments, each one with three technical repeats. Interestingly, immediately after cell mixing, ∼20% of the N1 cells became double positive, even when the N4 cell population was repeatedly washed. During the first 2 h, the fraction of double-positive cells dropped to ∼4%, but then increased steadily for 6 h reaching an ∼65% plateau that was maintained until the end of the experiment. The 2–8 h window of the nectin-elicited uptake process indicates that it is most active as the cells adhere to form a confluent monolayer.

One of the models for exchange of specific membrane proteins by trans-endocytosis considers internalization of vesicles with two membranes, one from each cell (Kusakari et al., 2008). These vesicles would transfer cytoplasmic proteins from ‘donor’ to ‘acceptor’ cells. To assess whether intercellular transfer of cytoplasmic proteins occurs, we stained N4–Dendra2-expressing A431D donor cells with a membrane-permeable dye (CellTracker Deep Red, CTdR) that reacts with intracellular thiols and labels cytoplasmic proteins and peptides, thereby becoming membrane impermeable (Zhou et al., 2016). This dye emits far-red fluorescence that does not overlap with that emitted by mCherry. We co-cultured these donor cells with N1–mCherry-expressing acceptor cells. As negative control donor cells, we used parental A431D cells, and as negative control acceptor cells we used N1(F129D)–mCherry cells, which express N1 with a defective adhesive interface. Fig. 3C documents that CTdR is efficiently transferred from N4- to N1-expressing cells: the two left panels show CTdR uptake by the donor N4-expressing cells; the third panel shows the acceptor N1-expressing cells before mixing; and the furthest right panel documents efficient CTdR uptake by N1-expressing cells 8 h after mixing (top right quadrant).

We then determined the kinetics of cytoplasm transfer. We performed two independent experiments, each one with three technical repeats. Fig. S4 shows complete analyses of independent experiments. Fig. 3D shows a kinetic graph with averages and standard deviations of three experiments: ∼24% of N1-expressing cells take up CTdR at 8 hours after co-culture, which is 5–8 times higher than what was seen for background controls. We conclude that cytoplasmic protein transfer has similar kinetics to N4 uptake.

Some incoming cargo remains functional

To assess whether incoming cargo remains functional, we set up a sensitive detection system based on the transfer of encapsidated viral genomes, namely MeV ribonucleocapsids (RNPs). Helical MeV RNPs comprise one molecule of negative strand RNA (∼16,000 bases) tightly encapsidated by nucleocapsid (N) protein. Many polymerase (L) and polymerase co-factor (P) proteins are bound to each RNP and can transcribe it (Lamb and Parks, 2013).

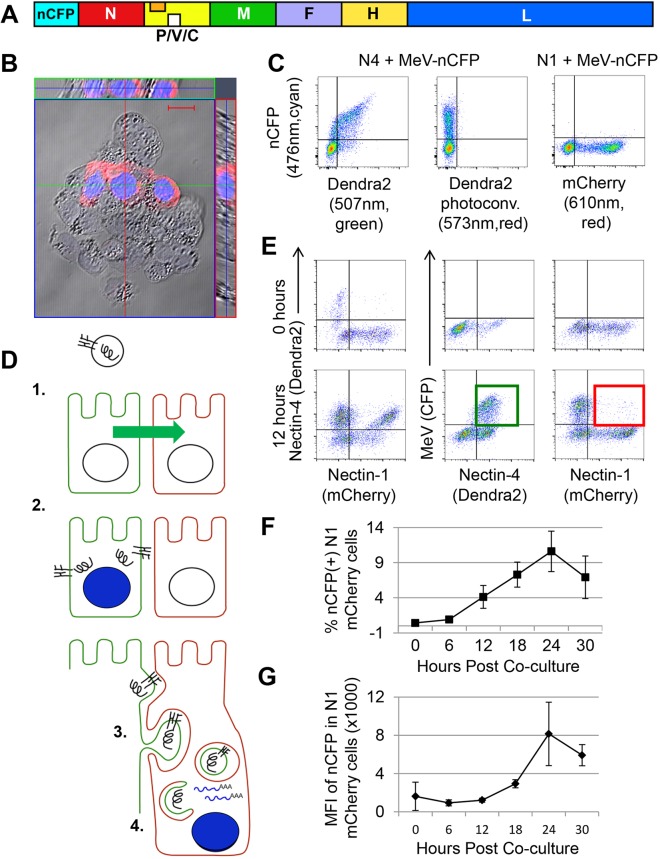

To easily monitor gene expression from RNPs, we generated a recombinant MeV-expressing nuclear cyan fluorescent protein (nCFP) from an additional transcription unit inserted upstream of the N gene (Fig. 4A). Nuclear localization of nCFP (Fig. 4B) minimizes confounding effects from uptake by acceptor cells of viral proteins located in the cytoplasm of donor cells (like N, visualized in red). Fig. 4C documents efficient infection of N4 (MeV receptor)-expressing A431D cells by MeV–nCFP (left panel), and minimal background in N1-expressing A431D cells that are not expected to be infected (right panel). As an additional control, we confirmed that the short pulse of 405 nm light activating CFP fluorescence causes minimal conversion of Dendra2 fluorescence to red fluorescence (Fig. 4C, central panel).

Fig. 4.

Transferred viral RNP remain functional in acceptor cells. (A) Schematic of the recombinant MeV–nCFP genome. The additional transcription unit expressing nCFP is inserted before the nucleocapsid (N) gene. (B) Nuclear localization of nCFP, which emits cyan fluorescence. H358 cells were infected with MeV–nCFP and imaged at 48 h post inoculation. Cytoplasmic N protein was visualized with a secondary antibody emitting red fluorescence. Scale bar: 20 µm. (C) MeV–nCFP infects only N4-expressing cells. N4–Dendra2 (left and center panel)- and N1–mCherry (right panel)-expressing cells were incubated with MeV–nCFP (MOI=2), and CFP expression was analyzed 12 h later. The center panel serves as a control for Dendra2 photoconversion in MeV–nCFP-infected cells. Emission maximum of the fluorescent proteins and filters are indicated. (D) Proposed steps in the RNP transfer process, and experimental approach to measure RNP transfer. (1) N4-expressing cells are shown in green, N1-expressing cells in red. An enveloped viral particle (top) is shown with the H and F glycoproteins inserted in its membrane and a helical RNP. (2) Viral particles enter only N4-expressing cells, where they produce cytoplasmic RNPs, glycoproteins that are transported to the cell membrane, and nCFP that is concentrated in the nucleus. (3) N1-expressing cells internalize membranes of N4-expressing cells that include viral glycoproteins and enclose the RNPs (top); double-membrane vesicles with an RNP cargo are formed (center); fusion between the two membranes occurs (close to bottom). (4) RNPs released in the cytoplasm of the acceptor cell are transcriptionally active, resulting in nCFP expression and nuclear concentration. (E) RNP transfer experiment. N4–Dendra2-expressing A431D cells were infected (MOI=2) and allowed to settle for 4 h; N1–mCherry-expressing cells were overlaid at a 1:1 ratio. Cells were analyzed either immediately after mixing (0 h, top row), or after 12 h of co-culture (bottom row). The three-color FACS analyses are shown in two-color combinations; for details see text. (F) Percentage of N1-expressing cells infected by MeV, as determined by nCFP expression. (G) Levels of MeV replication in N1-expressing cells, as determined by nCFP expression mean fluorescent intensity (MFI). The graphs in F and G show mean±s.d. of three independent experiments, each one with three technical repeats. The primary data are in Fig. S5.

The proposed steps in the RNP transfer process, and the experimental approach to characterize it, are illustrated in Fig. 4D. In step 1, N4–Dendra2 cells are infected and allowed to settle, and N1–mCherry-expressing cells are overlaid. In step 2, the co-cultures are incubated for 12 h to allow viral replication to generate RNPs and glycoproteins. During this step, RNPs could be transferred to N1–mCherry cells, possibly through uptake of double-membrane vesicles (step 3). This would be followed by membrane fusion and RNP release, resulting in nCFP expression in the acceptor cell (step 4).

Fig. 4E shows the results of an RNP transfer experiment. Cells were analyzed either immediately after mixing (0 h, top row), or after 12 h of co-culture (bottom row). The three-color FACS analyses are shown in two-color combinations: N1 and N4 channels (left column), MeV and N4 channels (middle column), or MeV and N1 channels (right column). The left panel of the top row shows that at 0 h, individual cells expressed only either N4 (top left quadrant) or N1 (bottom right quadrant). The center and right panels show that no virus replication was detected (background levels less than 0.1%, top right quadrants).

Fig. 4E (bottom row panels) documents processes occurring during the 12 h of co-culture. The left panel shows that the majority of the N1–mCherry-expressing cells become double positive (top right quadrant), as expected due to the uptake of N4–Dendra2. The center panel indicates that the majority of N4-expressing cells become infected, as they express nCFP (green square in the top right quadrant). The right panel reveals that a small fraction of the N1-expressing cells become nCFP positive, implying transfer of functional RNPs from N4-expressing cells (red square in the top right quadrant).

To measure the kinetics of RNP transfer, we analyzed nCFP expression in N1–mCherry cells at 0, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 30 h after overlay. Fig. S5 shows three repeats of this experiment, and Fig. 4F a graph with averages and standard deviations. Immediately after cell mixing, ∼0.4% of the N1 cells was double positive, setting a background threshold. After 6 h, the percentage of double-positive cells was slightly above background, and progressively increased to 10% at 24 h after co-cultivation before dropping at 30 h, when extensive cell death was noted.

Fig. 4G shows a kinetic analysis of the levels of nCFP expression in individual N1-expressing cells based on the primary data in Fig. S5. The mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of nCFP expression increased exponentially between 12 and 24 h, consistent with MeV replication. After 24 h, the nCFP levels decreased, as did the number of infected N1-expressing cells (Fig. 4F). We believe that uptake of substantial amounts of cytoplasm, together with viral replication, accounts for impaired viability of acceptor cells.

We also note that under these experimental conditions, ∼30–35% of N1-expressing cells took up N4 (Fig. 4E), which is less than the 50–75% cytoplasm-receptive cells observed when the two cell populations settle simultaneously instead of being overlaid (Fig. 3). Since ∼10% of N1-expressing cells express nCFP, altogether, the data in Fig. 4E,G indicate that in almost a third of the cytoplasm-receptive cells viral RNPs remain functional and express nCFP.

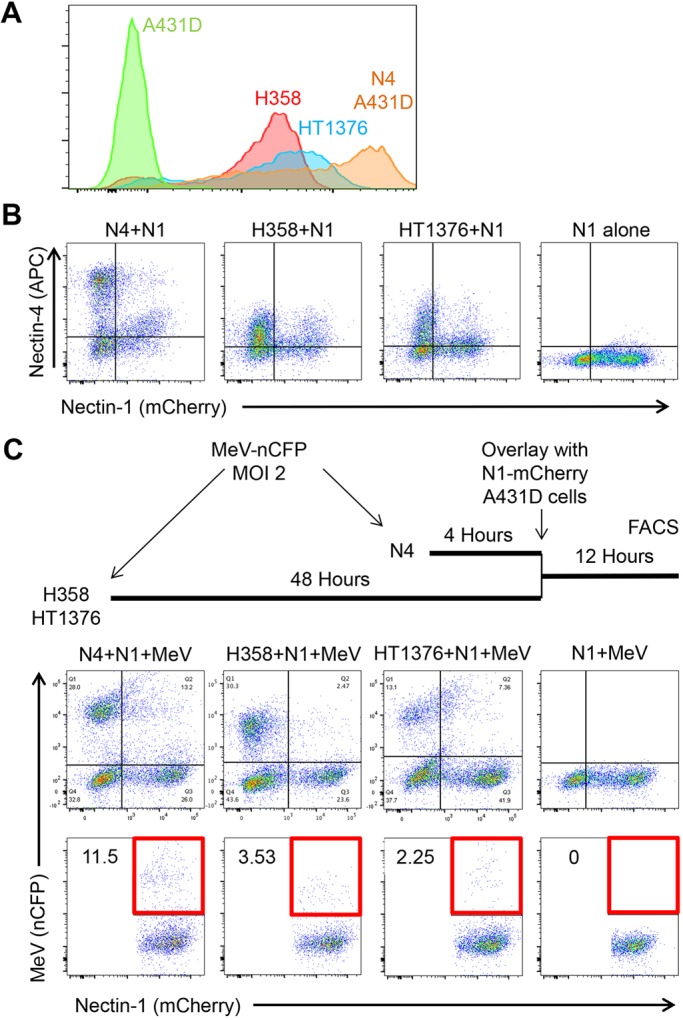

Different epithelial cell lines can spread infection

We then asked whether cell lines expressing physiological levels of N4 can ‘donate’ functional RNPs to nectin-1-expressing A431D cells. We used two human epithelial cell lines permissive to MeV infection, H358 and HT1376 (Leonard et al., 2008). The levels of endogenous N4 expressed by these cell lines were compared with those expressed by A431D N4–Dendra2-expressing cells using an N4-specific monoclonal antibody. Fig. 5A shows that HT1376 cells express ∼five times less N4 than A431D N4–Dendra2 cells, and H358 cells ∼10 times less. The cell mixing experiments of Fig. 5B show that N1–mCherry-expressing cells can take up N4 from H358 and HT1376 cells (second and third panels, respectively), albeit less efficiently than from A431D N4–Dendra2 cells (first panel). Fig. S6 shows that most N4 is internalized into N1–mCherry-expressing cells, as opposed to remaining on the cell surface or being recycled from there.

Fig. 5.

Epithelial cell lines expressing physiological N4 levels can spread infection. (A) FACS analysis of N4 expression levels in epithelial cell lines H358 and HT1376, as compared to N4–Dendra2 A431D cells. Primary antibody 337516 (R&D Systems) was used to detect N4, with a secondary antibody emitting fluorescence in the PE channel. (B) N1–mCherry-expressing cells internalize N4 from H358 and HT1376 cells. N1–mCherry A431D cells were overlaid on N4–Dendra2-expressing A431D cells (first panel), H358 cells (second panel) or HT1376 cells (third panel), or plated alone (fourth panel), incubated for 12 h, fixed, permeabilized, antibody stained and analyzed by FACS. Antibody 337516 was used to detect N4, with a secondary antibody emitting fluorescence in the APC channel. (C) N1–mCherry expressing cells can internalize MeV RNP from H358 and HT1376 cells. Top: schematic drawing of the experiment. Center row of panels: nCFP expression in mixed cultures infected by MeV–nCFP. Panel order is as in B. Bottom row of panels: quantitative analysis of the double-positive (N1-mCherry and nCFP) cells. The areas selected for quantification are indicated by a red square.

We then assessed whether and how efficiently the N1–mCherry-expressing cells take up MeV RNPs from H358 and HT1376 cells. The timeline on top of Fig. 5C illustrates that MeV infections were allowed to proceed for 48 h before cells were overlaid with N1–mCherry-expressing cells. The upper right quadrants of the top row of panels show that fewer N1-expressing cells became nCFP-positive after co-culture with H358 and HT1376 cells (second and third panel) than after co-culture with N4-Dendra2-infected cells (first panel). The bottom row of panels quantifies the fraction of nCFP-positive N1-mCherry-expressing cells as ∼3.5% or ∼2.2% after being overlaid on infected H358 or HT1376 cells, respectively. Even though this is 3–5 times less than 11.5% double-positive cells detected after overlay on infected A431D N4–Dendra2 cells (first panel), these experiments show that functional MeV RNPs can be taken up from epithelial cell lines expressing N4 at physiological levels. Direct inoculation of N1–mCherry cells shows gives detectable background infection (bottom row, fourth panel).

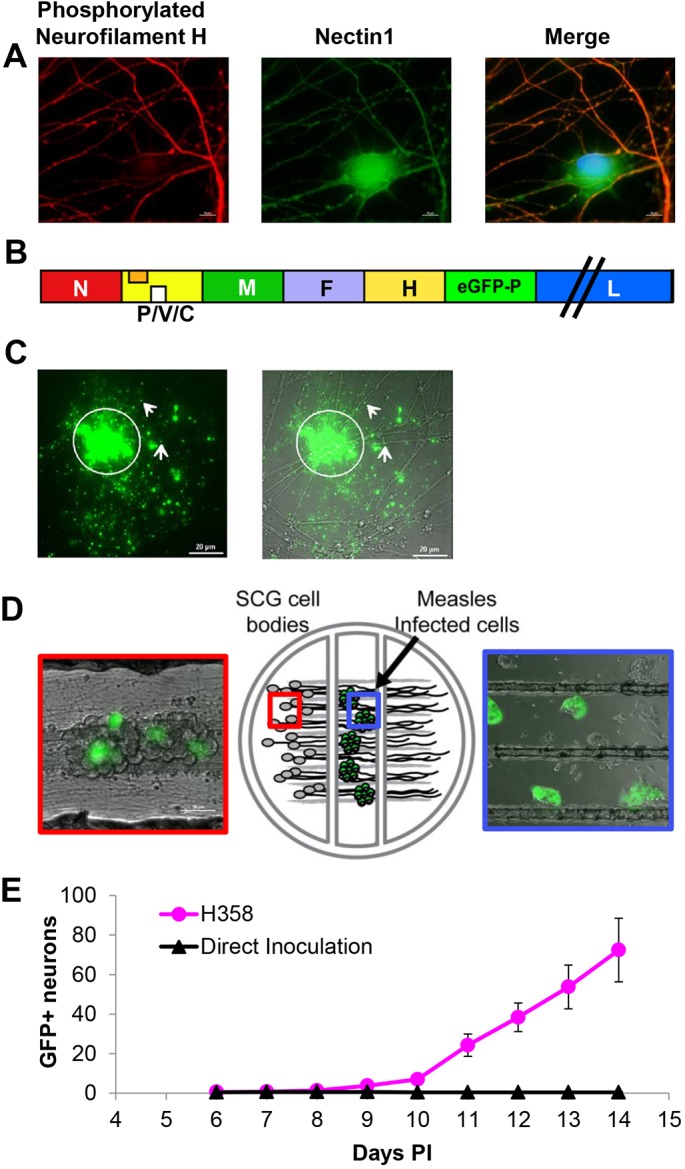

Primary neurons can take up infectious material from epithelial cells

Having shown that functional MeV RNPs can be transferred from cells expressing N4 at physiological levels to cells overexpressing N1, we asked whether they can also be transferred to cells expressing N1 at physiological levels, such as embryonic mouse superior cervical ganglia (SCG) neurons (Fig. 6A; Fig. S7). Note that mouse and human nectin-1 have structurally conserved adhesive surfaces and functional interactions with different nectins (Harrison et al., 2012).

Fig. 6.

MeV spreads from infected epithelial cells to primary neurons. (A) Primary mouse SCG neurons stained with mouse monoclonal phosphorylated neurofilament H-specific antibody (red) or rabbit polyclonal N1-specific antibody (green). Nuclei are contrasted with Hoechst staining (blue). While phosphorylated neurofilament H is only present in axons, N1 is observed in all neuronal structures. (B) Schematic of the recombinant MeV-RNPtracker genome. The additional transcription unit expressing eGFP–P is inserted after the H gene. (C) Viral RNP in association with neuronal axons after co-culture with H358 cells infected with MeV-RNPtracker. Left: GFP fluorescence associated with the MeV-RNPtracker structures. Right: merged phase-contrast image. The arrows indicate GFP positivity distal to cell contact sites. (D) Center panel: drawing of the compartmentalized neuronal culture system. Dissociated mouse SCG neurons are plated in the left compartment. The neurons extend neurite projections underneath two sequential barriers into the right compartment. Right panel: cells infected with MeV-RNPtracker are plated onto the neurites in the middle compartment; the picture was taken 48 h post co-culture. Left panel: SCG cell bodies 14 days after seeding infected H358 cells in the middle compartment. Infected cells emit green fluorescence. (E) Number of fluorescence-emitting SCG cell bodies in the left compartment after overlay of neurites with MeV-RNPtracker-infected H358 cells (red dots) or after direct inoculation with MeV-RNPtracker (black triangles). Six compartmentalized cultures were seeded for each condition. Results are mean±s.e.m.

To track MeV spread, we used a virus with a duplicated P gene that expresses a GFP–P hybrid protein (MeV-RNPtracker, Fig. 6B). This hybrid protein is incorporated in viral RNPs, allowing for their direct detection. For the experiment shown in Fig. 6C, H358 cells were infected with the MeV-RNPtracker and overlaid onto dissociated neurons. Following 4 days of co-culture, we observed multiple regions (one is indicated by the circle) where an infected H358 cell had interacted with axonal projections, resulting in the release of fluorescent RNPs. Some of the corresponding GFP puncta visibly associated with axonal structures at distal areas are indicated with white arrows. However, signals from donor cells complicated tracking of infection.

To quantitatively study transfer of MeV infection to neurons, we adapted the Campenot chamber system previously used to characterize the spread of neuroinvasive herpes viruses (Ch'ng and Enquist, 2006). In this system, SCG neurons are cultured within a Teflon ring. The ring is divided into compartments and attached to a treated culture surface, creating three hydrodynamically isolated compartments (Fig. 6D). Dissociated SCG neurons are plated in the left compartment and extend axons underneath the internal walls of the ring. The isolated axon termini contained in both the middle and right compartments can then be differentially treated with viral inoculum or infected cells (blue box). Infection of neuronal cell bodies requires the transfer of infectious particles or RNPs into the isolated axons followed by transport to the cell body (red box). As has been previously shown, a single barrier between axon termini and soma can be used to experimentally evaluate axonal transport of infection and axonal signaling (Campenot, 1977; Koyuncu et al., 2013).

To assess whether transfer of MeV infection occurs, we overlaid neuronal axons with MeV-infected H358 cells. We used the chamber proximal to the neuronal cell bodies to maximize axonal contacts (Fig. 6D, large blue box); as a negative control, we directly inoculated axons with a high titer of MeV particles. The number of GFP-positive neuronal cell bodies (Fig. 6D, large red box) observed after co-culture was then plotted for six replicates. Fig. 6E documents that, after co-culture with infected H358 cells, on average 72 GFP-positive SCG cell bodies were detected. After direct inoculation, on average, less than one GFP-positive SCG cell body was detected. Thus, cell-associated transfer of MeV infection to neurons is much more efficient than particle-mediated infection.

Infection of neurons is N4 dependent

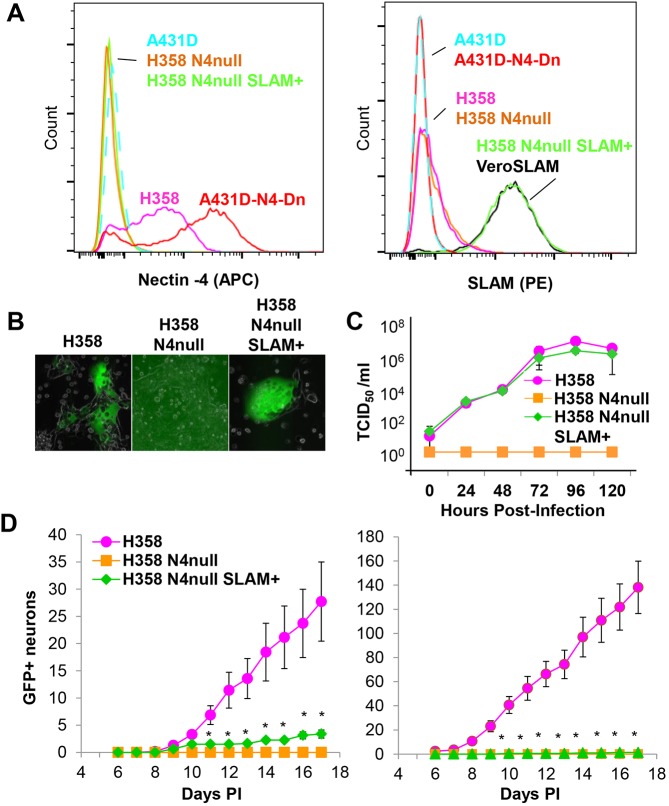

To assess whether MeV transfer from H358 cells to neurons depends on N4, we knocked out its expression while also providing an alternative receptor for cell entry in the form of the lymphocytic MeV receptor SLAM. We first knocked out N4 expression in H358 cells by CRISPR/Cas9 gene inactivation, generating H358 N4-null cells. We then used lentiviral transduction to express human SLAMF1, generating H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells.

In Fig. 7A, we verified surface expression of N4 (left panel) and SLAM (right panel) in the two H358-derived cells lines, and in control cell lines. These analyses confirmed complete inactivation of N4 expression, and SLAM expression at the expected level. In Fig. 7B, we compared MeV infection in the three cell lines by microscopy, and documented GFP expression only in H358 and H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells. We also compared replication kinetics, and documented similar levels of infection in these two cell lines (Fig. 7C). This sets up the assay to assess the relevance of N4 expression for infection transfer.

Fig. 7.

Cell-associated MeV infection of neurons is N4 dependent. (A) Characterization of H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells. Analysis of N4 (left panel) and SLAM (right panel) surface expression. Color coding of cell lines: A431D, light blue; A431D N4–Dendra2, red; H358, magenta; H358 N4-null, orange; H358 N4-null SLAM+, green; VeroSLAM, black. (B) Fluorescent microscopy analysis of H358, H358 N4-null, and H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells 48 h post-infection with MeV-RNPtracker. (C) Time course of MeV–nCFP production by H358, H358 N4-null, and H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells (n=3, error bars, 3× s.d.). (D) Kinetic analysis of infection transfer by cells expressing or not expressing N4. Two experiments are plotted in the left and right panels. H358, H358 N4-null, or H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells were inoculated with MeV-RNPtracker. Vertical axis: number of fluorescence-emitting SCG cell bodies in the left compartment after overlay of neurites in the middle compartment. Each experiment used a minimum of six compartmentalized cultures seeded with infected cells. Results are mean±s.e.m. Asterisks indicate a non-zero number for H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells.

Fig. 7D shows two repeats of a triplicate infection transfer experiment. H358, H358 N4-null, or H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells were inoculated with MeV-RNPtracker and co-cultured with primary neurons. Co-culture with infected H358 cells resulted in GFP expression in 30 to 148 SCG cell bodies, indicative of the extent of infectious virus transferred. H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells transferred infection inefficiently (average of three GFP-positive cell bodies), while H358 N4-null cells, which do not support primary infection, did not transfer infection. Thus, MeV spread from epithelial H358 cells to primary neurons is dependent on N4.

DISCUSSION

We have discovered a process transferring transmembrane and cytoplasmic proteins between cells expressing different nectins. Intercellular protein transfer relies on cell–cell contacts established by the nectin adhesive interface, and on the nectin cytoplasmic region. The new process is analogous to trans-endocytosis processes allowing cells to communicate and coordinate their activity (Gaitanos et al., 2016; Hudrisier et al., 2001; Marston et al., 2003; Matsuda et al., 2004; Qureshi et al., 2011). We show here that this new process, in addition to transmembrane proteins, transfers cytoplasm, and that a virus can take advantage of the cytoplasm flow to spread. We name the process nectin-elicited cytoplasm transfer, in short NECT. We do not think that NECT is a constitutive feature of cells expressing a specific combination of nectins. Rather, we have shown that cytoplasm transfer occurs efficiently only when the cell adhesion process begins. NECT may occur when new junctions are formed during tissue- and organ-specific differentiation and morphogenesis, and during abnormal growth due to carcinogenesis.

Once nectin trans-interactions on the plasma membrane are established, the cytoplasmic region of N1 governs transfer direction: unidirectional transfer occurs when the acceptor cell carries a nectin with the N1 cytoplasmic region, and the donor cell one with either the N3 or N4 cytoplasmic region. Transfer becomes bi-directional when interacting cells express nectins that each contain the N1 cytoplasmic region, or lack cytoplasmic regions entirely. Cytoplasmic regions from all nectins contain sequence motifs associated with endocytosis (Fig. S2). Some sequence signals are unique to N1, but further investigation is needed to identify the signals governing trans-endocytosis.

Internalized N1–N4 complexes associate with a part of the retromer cargo-sorting complex, indicating that they are being moved through an endocytic pathway. However, they do not associate with a lysosomal marker, implying that complexes escape the pathway and destruction. That led us to ask: can NECT transfer functional proteins to the N1 acceptor cell?

To address this question, we took advantage of a recombinant virus expressing a fluorescent protein reporting transcription, and thus functionality of the transferred RNPs. We detected nCFP expression in almost a third of the NECT-receptive cells, implying that some RNP can escape endocytic degradation. Thus, at least in the context of a viral infection, cytoplasm transfer by NECT is productive.

How NECT works requires further investigation. We know that cytoplasmic translocation of RNPs occurs even in the absence of a receptor on acceptor cells. We think that the MeV membrane fusion apparatus (MFA) facilitates translocation, but we do not know what triggers the MFA in N1-expressing cells. The MFA receptor attachment function can be replaced by an external tether (Rasbach et al., 2013), implying that triggering can occur through prolonged close contacts with membranes. Alternatively, low endosomal pH may trigger the MFA, as MeV cell entry can be facilitated by endocytic or macropinocytosis processes (Delpeut et al., 2017; Gonçalves-Carneiro et al., 2017).

Morbilliviruses, including MeV and canine distemper, can cause neurological diseases. However, a neuronal receptor has not yet emerged (Alves et al., 2015; Ehrengruber et al., 2002; Lawrence et al., 2000; Makhortova et al., 2007; Watanabe et al., 2015, 2019). We find that NECT can spread MeV infections from epithelial cells to primary neurons, which is possibly the first step of neuropathology. Neuronal uptake could occur in any innervated N4-expressing epithelial tissue, such as the nasal turbinate, where MeV infection has been documented in vivo (Ludlow et al., 2013). Subsequently, viral RNPs would reach the brain by retrograde transport. However, in the absence of a receptor, MeV spread would be limited to the first infected neuron, unless the infection becomes receptor independent. Indeed, in human brains, specific viral mutations that lower the activation threshold of the viral membrane fusion apparatus are consistently selected (Bellini et al., 2005; Cathomen et al., 1998; Cattaneo et al., 1988; Jurgens et al., 2015; Ludlow et al., 2015; Schmid et al., 1992; Watanabe et al., 2015, 2019). Thus, NECT would require a second hit in the form of virus mutations to cause neurological disease.

MeV spread within neurons is markedly slower than that of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and pseudorabies virus (Antinone and Smith, 2010). Direct inoculation of cell-free HSV-1 and pseudorabies viruses onto axons result in detectable infection of neuronal cell bodies within 12–24 h (Antinone and Smith, 2010; Koyuncu et al., 2013). In contrast, fluorescent protein-expressing neurons are first detected 6 days after overlay with MeV-infected cells. Additionally, an average of less than 100 fluorescent protein-positive neurons were observed, out of thousands present in the culture. This can partially be explained by the endocytic nature of NECT. Viral RNPs must escape a degradation pathway, which may be a relatively rare event. Another explanation for these differences is the kinetics of transport from distal axons to the cell body. Further experiments utilizing time-lapse video microscopy with MeV-RNPtracker will test this hypothesis, and could yield important insights on the type and efficiency of recruitment of the motor protein facilitating RNP transport in axons (Merino-Gracia et al., 2011).

NECT-related cytoplasm transfer processes may spread other pathogens. Trans-endocytosis from N3- to N1-expressing cells (Fig. 1) implies that NECT could occur between neurons, since N1 and N3 asymmetrically localize respectively at the pre- and post-synaptic sides of puncta adherens in the hippocampus (Mizoguchi et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2017). Remarkably, N3 is the protein that C. difficile toxin binds in enteric epithelia (LaFrance et al., 2015), implying that NECT may facilitate the spread of certain bacterial toxins. Poliovirus, the causative agent of paralytic poliomyelitis, uses nectin-like protein 5 (Necl-5, also known as PVR or CD155) as a receptor (Mendelsohn et al., 1989). The adhesive interfaces of Necl-5 and N1 interact (Harrison et al., 2012), and this interaction may facilitate receptor-independent delivery to the central nervous system (Lancaster and Pfeiffer, 2010; Ohka et al., 2012; Yang et al., 1997). EphrinB2, a protein that is trans-endocytosed (Marston et al., 2003; O'Neill et al., 2016), serves as receptor for Hendra and Nipah viruses, respiratory pathogens that can cause neurological disease (Bonaparte et al., 2005; Negrete et al., 2005). The RNPs of these viruses might well remain functional after uptake, and spread infection.

The NECT bulk cytoplasm transfer process may be ancestral. After establishment of the precise and tunable signaling pathways required for cell specialization and tissue function, NECT would have been silenced, among other reasons, to control virus spread. Nevertheless, here we report that a virus can take advantage of NECT to spread intercellularly. It remains to be determined whether, and in which tissues, cytoplasm transfer processes occur and extend viral tropism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of recombinant viruses

The MeV encoding CFP with a nuclear localization signal (MeV-nCFP) was constructed based on the wild-type strain IC-B 323 genome (Takeda et al., 2000). The mCerulean (CFP) gene fused to a triple repeat nuclear localization signal was retrieved from pOK10 kindly provided by Lynn Enquist (Department of Molecular Biology, Neuroscience Institute, Princeton University, Princeton, USA) (Taylor et al., 2012). Flanking MluI and AatII restriction sites were added by PCR using primers 5′-TTACGCGTCGGTCGCCACCATG-3′ and 5′-GAGAAAGGTAGGATCCAGATAAACTGACGTCTT-3′ (restriction sites are underlined), the sequence verified, and the cassette cloned in place of GFP in an additional transcription unit upstream of the N gene of pMV323GFP (Leonard et al., 2008). MeV–nCFP was rescued in helper 293-3-46 cells and propagated as previously described (Radecke et al., 1995). Titrations were performed on Vero-hSLAM cells (Ono et al., 2001). The MeV encoding a GFP-tagged phosphoprotein (MeV-RNPtracker) was also derived from the same wild-type genome. A GFP-tagged phosphoprotein was constructed by inserting the GFP reading frame after the P gene initiation Met, as performed previously (Devaux and Cattaneo, 2004). Flanking MluI and AatII restriction sites were added by PCR using primers, and the cassette cloned in an additional transcription unit downstream of the H gene of pMV323GFP.

Propagation of cell lines

The human lung cell line H358 (catalog no. CRL-5807; ATCC, Manassas, VA) was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and adjusted to contain 1.5 g/l sodium bicarbonate, 4.5 g/l glucose, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.2–7.5, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, nonessential amino acids and 10% FCS. The bladder cell line HT-1376 (CRL-1472; ATCC) was maintained in MEM with Earle's BSS, nonessential amino acids and 10% FCS. The A431D cell line and its derivatives were maintained in DMEM and 10% FBS. The MeV rescue helper cell line 293-3-46 (Radecke et al., 1995) was grown in DMEM with 10% FCS and 1.2 mg/ml G418. Vero-hSLAM cells, kindly provided by Yusuke Yanagi (Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan), were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 0.5 mg/ml of G418.

Construction of plasmids expressing nectins and nectin mutants

The coding sequences of full-length human N1 isoform delta (Uniprot ID Q15223-1, residues Met1 to Val517) or full-length human N4 isoform 1 (Uniprot ID Q96NY8-1, residues Met1 to Val510) were inserted between the HindIII and NotI restriction sites of the mammalian expression vector pRc/CMV (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA). mCherry–FLAG or Dendra2–Myc fluorescent tags were inserted into the nectin cytoplasmic domains at 17 amino acids before the C-terminus to preserve the afadin-binding site, as described previously for N2 constructs (Harrison et al., 2012). Sequences encoding the fluorescent tags were flanked with BsiWI and NheI restriction sites, resulting in two additional residues before (Arg-Thr) and after (Ala-Ser) each tag. Phenylalanine to aspartic acid mutations, to ablate the trans binding interface in N1 (F129D) and N4 (F132D), were introduced by the QuikChange method (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Cytoplasmic region deletion mutants (N1Δcyt and N4Δcyt) were prepared by replacing the cytoplasmic regions after residue Arg382 (N1) or Lys378 (N4) with the mCherry–FLAG or Dendra2–Myc tags followed by a stop codon. A cytoplasmic region swapped construct (N4cyt1) containing the extracellular and transmembrane regions of N4 fused to the cytoplasmic tail of N1 was prepared by replacing the N4 cytoplasmic domain after Lys378 with the corresponding region from His383 onwards of N1, including the mCherry–FLAG tag.

Generation of cells expressing nectins

Transfection and culture of A431D and A431 cells (Lewis et al., 1997) were performed as described previously (Hong et al., 2010). In brief, cells were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were transfected with the nectin-expressing plasmids by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After Geneticin (Cardinal Healthcare, Dublin, OH) selection (0.5 mg/ml), FACS was used to identify and sort cell populations with moderate nectin expression levels. A431D cells were used for most experiments because we monitored background levels of MeV infection in A431 cells.

Culturing of primary neurons and their infection

Primary mouse SCG neurons were collected from day 14 mouse embryos. The protocol was adapted from methods used for rat SCG dissection and culturing (Ch'ng and Enquist, 2006). All of the procedures with mice were submitted and approved through Montana State University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol #2016-31) and conformed to best practices defined by AALAC and the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare guidelines. Timed pregnant C57Bl/6 mice were euthanized by CO2 narcosis, followed by thoracotomy and removal of the tubal uterus containing embryos. Embryos were dissected and the SCG removed. Ganglia were dissociated with trypsin and trituration, as previously described (Ch'ng and Enquist, 2006). Neurons were subsequently maintained in neuronal media which consists of neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (Invitrogen), B27 supplement (Invitrogen) and 50 ng/ml neuronal growth factor 2.5S (Invitrogen).

Compartmentalized neuronal cultures were produced as previously described (Ch'ng and Enquist, 2005). Cell culture surfaces were coated with poly-ornithine (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at 500 µg/ml in borate buffer, pH 8.2 followed by murine laminin (Invitrogen) at 10 µg/ml in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hank's balanced saline solution. Prior to adherence of the three-compartment chamber, treated dishes were air-dried and parallel grooves were etched into the surface. A 1% methylcellulose, 1× DMEM solution was spotted on the grooves to allow axon penetration. Teflon isolator rings (CAMP320, Tyler Research, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada) were coated with autoclaved vacuum grease on one side and gently applied to the treated culture surface such that the parallel grooves extended across the three compartments, perpendicular to the inner walls. The compartments were individually filled with neuronal medium, and tested for leaks. Dissociated mouse SCG neurons were then plated into the left compartment and continuously cultured for a minimum of 15 days before experimentation.

MeV infection of compartmentalized SCG neuronal cultures was either performed directly or following co-culture with infected cells. For direct inoculation, to maximize potential infection, we inoculated cells or axons with the minimal volume of medium possible (100 µl) from MeV-RNPtracker viral stock (∼1×108 TCID50/ml) on axons in the middle compartment. After 1 h, we supplemented neuronal cultures with 900 µl complete medium to assure cell viability, while leaving the viral inoculum on the cells.

For co-culture infections, 106 H358, H358 N4-null or H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells were cultured in a 6-cm culture dish. Then, 200 µl of MeV-RNPtracker viral stock was applied to the cells for 1 h, and medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS. At 2 h after inoculum removal, cells were trypsinized and counted. 105 infected cells were plated into the middle compartment. Infection was allowed to proceed for 14–17 days. Neuronal cell bodies were then inspected daily for fluorescent protein expression for up to 17 days after inoculation or co-culturing.

Utilizing the middle chamber for our infection condition enhanced two experimental variables: (1) it increased the number of axons in contact with cells and virus, and (2) it reduced the distance of transport of MeV to the neuronal cell body. The limited ability of MeV to directly infect neurons reduced the potential for inadvertent transmission via microfluidic flow under the single barrier, which is a concern when working with more neurotropic viruses such as Pseudorabies virus (Ch'ng and Enquist, 2006). Even with these enhanced conditions, cultures required incubation for a minimum of 8 days and up to 17 days before detectable MeV-associated fluorescence could be observed in neuronal cell bodies.

FACS analysis of N4 uptake kinetics

A431D cells (5×104) expressing either N4 or N1 were mixed 1:1 and co-cultured at 37°C for the specified time (0–12 h) in 24-well plates in DMEM containing 5% FBS. Cells were trypsinized for 2 min, washed with complete medium, and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Flow cytometry was performed on a BD LSRII (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) machine. Standard deviation and averages were calculated from three independent experiments.

FACS analysis of cytoplasmic dye transfer

A431D N4–Dendra2 cells (5×104) and negative control parental A431D cells were plated in 24-well plates and left overnight in DMEM containing 5% FBS. After washing with serum-free medium, cells were incubated for 45 min in a 1:10,000 dilution of CTdR (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C34565, Waltham, MA) in serum-free medium and washed twice with complete medium. N1–mCherry or negative control N1(F129D)–mCherry cells (5×104) were overlaid on the 24-well plate with the CTdR-labeled cells and incubated at 37°C for the specified times (0, 2, 4, 6 or 8 h). Cells were trypsinized for 2 min, washed with complete medium, and fixed with 2% PFA prior to FACS analysis.

FACS analysis of RNP transfer

A431D cells expressing N4–Dendra2 were infected with MeV–nCFP at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2. Infection proceeded for 4 h while the cells (5×104 per well in a 24-well plate) settled. A431D cells expressing N1–mCherry or a mutant thereof were then overlaid at a 1:1 ratio in the presence of fusion-inhibiting peptide Z-D-Phe-L-Phe-Gly-OH (FIP) (Firsching et al., 1999; Norrby, 1971) at a concentration of 0.02 mg/ml (Bachem California Inc., Torrance, CA) in order to preserve integrity of N4 cells during MeV infection. Co-cultured cells were incubated at 37°C for the specified time (0, 12 or 24 h), detached with EDTA and fixed with 2% PFA.

When H358 or HT1376 cells were used as N4-expressing cells, infection proceeded for 48 h, at which time the N1–mCherry cells were overlaid in the presence of FIP. After detachment with EDTA, cells were fixed for 15 min in 4% PFA, permeabilized by 0.1% Triton-X treatment for 15 min, and washed with FACS buffer (2% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide in PBS). Permeabilized cells were then blocked in FACS buffer for 1 h. The mouse anti-human N4 antibody MAB2659 was used to detect N4 clone 337516 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 1 h. After three washes with FACS buffer, allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated AffiniPure F(ab′)2 fragment (H+L) goat anti-mouse-IgG secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:200 for 1 h at room temperature was used (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Cells were washed with FACS buffer to remove excess antibody and fixed in 2% PFA. Flow cytometry was carried out using a Canto X flow cytometer with FACSDiva software to measure expression levels of Dendra2 or APC (N4), mCherry (N1) or CFP (MeV-nCFP) fluorophores in individual cells. Compensation and analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Treestar Inc., Ashland, OR).

FACS analysis of N4 and SLAM

To measure expression levels of N4, cells were detached with 10 mM EDTA in PBS, suspended in FACS buffer for 1 h, washed three times with FACS buffer, and incubated with mouse anti-human N4 antibody MAB2659, clone 337516 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 1 h. After three washes with FACS buffer, cells were incubated with the R-phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse F(ab′)2 Fragment IgG (H+L) (115-116-146) as secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc.), at a dilution of 1:200 for 1 h. After three washes with FACS buffer, cells were fixed in 2% PFA in PBS prior to FACS analysis. SLAM expression was verified using PE-conjugated mouse anti-human SLAM antibody (1:10, BD Pharmingen, 559592, San Diego, CA).

Microscopy

N4–Dendra2- and N1–mCherry-expressing A431D or A431 cells were simultaneously plated on glass coverslips for 48 h then fixed with 3% PFA and imaged using wide-field Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon, Minato, Tokyo, Japan) and a digital camera CoolSNAP EZ (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). The images were processed using NIS-Element software (Nikon). For movies, cells were imaged on the second day after plating essentially as described previously (Indra et al., 2013). Green and red images were taken simultaneously using an image splitter in 1 min intervals using halogen light that minimized phototoxicity and photobleaching.

For MeV infection analyses, H358 cells were stained 48 h after inoculation with the nucleocapsid protein-specific N505 rabbit antiserum (Toth et al., 2009). An Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody was used, and cells were fixed in 2% PFA. Confocal analyses were performed on a LSM 780 microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany). N4–Dendra2 and N1–mCherry A431D or A431 cells were co-cultured 24 h for confocal analysis on 3.5 mm glass bottom dishes, fixed with 2% PFA and mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

For LAMP-1 and VPS35 staining, A431D N1–mCherry and N4–Dendra2 cells were mixed in a ratio 1:1 and plated on glass coverslips for 24 h at 37°C. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS and stained with anti-Lamp1 (1:500, Abcam, #ab24170, Cambridge, UK) or goat poly-clonal anti-VPS35 antibody (1:1000, Abcam, #ab10099). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 647-labeled donkey anti-rabbit-IgG (Invitrogen) or Alexa Fluor 633-labeled donkey anti-goat-IgG (Invitrogen). Coverslips were mounted on glass slides using SlowFade. Prepared slides were examined on Zeiss LSM 800 microscope equipped with the Airyscan detector and a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.40 DIC M27 oil objective. All files were Airyscan processed and saved in the czi format.

For nectin-1 staining, SCG primary neurons were cultured for 8 days in neural basal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (Invitrogen) and 2% B27 supplement (Invitrogen). Then, neurons were gently washed with PBS, fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min, washed twice with PBS, then blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. Rabbit polyclonal nectin-1-specific antibody (used at 1 μg/ml final conc.; 1:200; SC-28639, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) and mouse monoclonal phosphorylated neurofilament H-specific antibody (used at 2 μg/ml final conc.; 1:500 dilution; 801601, BioLegend, San Diego, CA) were diluted in staining buffer containing 0.5% saponin and 0.125% BSA in PBS. Neurons were incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Cells were washed carefully three times with staining buffer, then incubated with secondary anti-rabbit IgG-NL493 (R&D Systems) and anti-mouse IgG-DyLight 550 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) mix in staining buffer for 2 h. After washing, cells were incubated for 5 min with 2 µg/ml Hoechst 33258 stain to contrast nuclei. Fluorescence was acquired using a Nikon Eclipse 80Ti microscope and analyzed with NIS Element software (Nikon).

Generation of H358 N4-null and H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells

H358 N4-null cells were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 utilizing guide RNAs 5′-GAGTGCTAAGGAACTTTAAAA-3′ and 5′-TGGCTTCCACATGTCTCTCTG-3′ targeting exon 3 of N4 (Uniprot ID Q96NY8-1) following the previously established Ran et al. protocol (Ran et al., 2013). Briefly, H358 cells were transfected with the CRISPR/Cas9-2A-GFP system then clonally sorted for GFP positivity. Viable clones were then screened functionally by resistance to MeV–nCFP infection. Resistant clones were then screened by FACS analysis for surface N4 expression. SLAM expression was introduced to produce H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells using pTsin-IRES-SLAM-puro generated lentiviral vector (Morrison et al., 2014) with a copy of the SLAMF1 coding region (Cocks et al., 1995) between flanking restriction sites ClaI and XhoI, and maintained under 0.5 mg/ml puromyocin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with expression verified by FACS.

To determine viral growth kinetics H358, H358 N4-null, and H358 N4-null SLAM+ cells were infected with MeV-nCFP in six-well plates (MOI=0.5) for 72 h. Three samples were collected per cell type at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h post infection. Titers were determined on Vero-hSLAM cells as described above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Crystal Mendoza for help characterizing MeV–nCFP. A.R.G. thanks the Mayo Microscopy and Cell Analysis core, and Aaron Johnson, for training and consultations.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.R.G., M.M., C.K.N., D.D.B., L.S., R.C.; Methodology: A.R.G., O.J.H., R.B.T., M.M., C.K.N., R.C.D., C.K.P., O.A., A.P.S., I.I., T.T., I.K., M.P.T.; Validation: C.K.N., C.K.P.; Formal analysis: A.R.G., O.J.H., R.B.T., M.M., C.K.N., C.K.P., O.A., A.P.S., I.I., T.T., I.K., D.D.B.; Investigation: A.R.G., O.J.H., R.B.T., R.C.D., C.K.P., I.K., R.C.; Resources: R.C.D., D.D.B., M.P.T., S.M.T., B.H., L.S., R.C.; Data curation: A.R.G., O.A., T.T., I.K., R.C.; Writing - original draft: A.R.G., C.K.N., R.C.; Writing - review & editing: A.R.G., O.J.H., R.B.T., M.M., C.K.N., R.C.D., C.K.P., A.P.S., I.I., M.P.T., S.M.T., B.H., L.S., R.C.; Visualization: A.R.G., O.A., A.P.S., I.I., T.T., R.C.; Supervision: D.D.B., M.P.T., S.M.T., B.H., L.S., R.C.; Project administration: M.P.T., S.M.T., B.H., L.S., R.C.; Funding acquisition: D.D.B., R.C.

Funding

C.K.N., C.K.P., O.A. and R.C. were supported, in part, by grants AI125747 and AI128037 from the National Institutes of Health, and from a grant of the Mayo Clinic Center for Biological Discovery to R.C. The salaries of A.R.G. and R.C.D. were provided by Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. C.K.N. was supported in part by the Marcia T. Kreyling Career Development Award in Pediatric and Neonatal Research from the Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science. M.M. was a Merck fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation. R.B.T., I.I. and S.M.T. were supported by grants AR44016 and AR070166 from the National Institutes of Health to S.M.T. O.J.H. and L.S. were supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM062270 to L.S. A.P.S. and B.H. were supported by National Science Foundation grant Division of Molecular and Cellular Biosciences 1412472 to B.H. T.T., I.K. and M.T. were supported by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Development Award (IDeA) Program grant GM110732 [8P20GM103500-10] and the Montana Agriculture Experiment Station. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.235507.supplemental

References

- Alves L., Khosravi M., Avila M., Ader-Ebert N., Bringolf F., Zurbriggen A., Vandevelde M. and Plattet P. (2015). SLAM- and nectin-4-independent noncytolytic spread of canine distemper virus in astrocytes. J. Virol. 89, 5724-5733. 10.1128/JVI.00004-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinone S. E. and Smith G. A. (2010). Retrograde axon transport of herpes simplex virus and pseudorabies virus: a live-cell comparative analysis. J. Virol. 84, 1504-1512. 10.1128/JVI.02029-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini W. J., Rota J. S., Lowe L. E., Katz R. S., Dyken P. R., Zaki S. R., Shieh W. J. and Rota P. A. (2005). Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: more cases of this fatal disease are prevented by measles immunization than was previously recognized. J. Infect. Dis. 192, 1686-1693. 10.1086/497169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch J., Juleff N., Heaton M. P., Kalbfleisch T., Kijas J. and Bailey D. (2013). Characterization of ovine Nectin-4, a novel peste des petits ruminants virus receptor. J. Virol. 87, 4756-4761. 10.1128/JVI.02792-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaparte M. I., Dimitrov A. S., Bossart K. N., Crameri G., Mungall B. A., Bishop K. A., Choudhry V., Dimitrov D. S., Wang L.-F., Eaton B. T. et al. (2005). Ephrin-B2 ligand is a functional receptor for Hendra virus and Nipah virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 10652-10657. 10.1073/pnas.0504887102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler D. (2015). Measles by the numbers: a race to eradication. Nature 518, 148-149. 10.1038/518148a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagan R. L., Krämer H., Hart A. C. and Zipursky S. L. (1992). The bride of sevenless and sevenless interaction: internalization of a transmembrane ligand. Cell 69, 393-399. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90442-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campadelli-Fiume G., Cocchi F., Menotti L. and Lopez M. (2000). The novel receptors that mediate the entry of herpes simplex viruses and animal alphaherpesviruses into cells. Rev. Med. Virol. 10, 305-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campenot R. B. (1977). Local control of neurite development by nerve growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74, 4516-4519. 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathomen T., Naim H. Y. and Cattaneo R. (1998). Measles viruses with altered envelope protein cytoplasmic tails gain cell fusion competence. J. Virol. 72, 1224-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo R., Schmid A., Eschle D., Baczko K., ter Meulen V. and Billeter M. A. (1988). Biased hypermutation and other genetic changes in defective measles viruses in human brain infections. Cell 55, 255-265. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90048-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch'ng T. H. and Enquist L. W. (2005). Neuron-to-cell spread of pseudorabies virus in a compartmented neuronal culture system. J. Virol. 79, 10875-10889. 10.1128/JVI.79.17.10875-10889.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch'ng T. H. and Enquist L. W. (2006). An in vitro system to study trans-neuronal spread of pseudorabies virus infection. Vet. Microbiol. 113, 193-197. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocks B. G., Chang C.-C., Carballido J. M., Yssel H., de Vries J. E. and Aversa G. (1995). A novel receptor involved in T-cell activation. Nature 376, 260-263. 10.1038/376260a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Fontoura Budaszewski R. and von Messling V. (2016). Morbillivirus experimental animal models: measles virus pathogenesis insights from canine distemper virus. Viruses 8, E274 10.3390/v8100274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpeut S., Sisson G., Black K. M. and Richardson C. D. (2017). Measles virus enters breast and colon cancer cell lines through a PVRL4-mediated macropinocytosis pathway. J. Virol. 91, e02191 10.1128/JVI.02191-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaux P. and Cattaneo R. (2004). Measles virus phosphoprotein gene products: conformational flexibility of the P/V protein amino-terminal domain and C protein infectivity factor function. J. Virol. 78, 11632-11640. 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11632-11640.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrengruber M. U., Ehler E., Billeter M. A. and Naim H. Y. (2002). Measles virus spreads in rat hippocampal neurons by cell-to-cell contact and in a polarized fashion. J. Virol. 76, 5720-5728. 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5720-5728.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firsching R., Buchholz C. J., Schneider U., Cattaneo R., ter Meulen V. and Schneider-Schaulies J. (1999). Measles virus spread by cell-cell contacts: uncoupling of contact-mediated receptor (CD46) downregulation from virus uptake. J. Virol. 73, 5265-5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke W. W. (2009). Discovering the molecular components of intercellular junctions–a historical view. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 1, a003061 10.1101/cshperspect.a003061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaitanos T. N., Koerner J. and Klein R. (2016). Tiam-Rac signaling mediates trans-endocytosis of ephrin receptor EphB2 and is important for cell repulsion. J. Cell Biol. 214, 735-752. 10.1083/jcb.201512010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty R. J., Krummenacher C., Cohen G. H., Eisenberg R. J. and Spear P. G. (1998). Entry of alphaherpesviruses mediated by poliovirus receptor-related protein 1 and poliovirus receptor. Science 280, 1618-1620. 10.1126/science.280.5369.1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves-Carneiro D., McKeating J. A. and Bailey D. (2017). The measles virus receptor SLAMF1 can mediate particle endocytosis. J. Virol. 91, e02255-16 10.1128/JVI.02255-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin D. E. (2013). Measles virus. In Fields Virology, Vol. 1 (ed. Knipe D. M. and Howley P. M.), pp. 1042-1069. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison O. J., Vendome J., Brasch J., Jin X., Hong S., Katsamba P. S., Ahlsen G., Troyanovsky R. B., Troyanovsky S. M., Honig B. et al. (2012). Nectin ectodomain structures reveal a canonical adhesive interface. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 906-915. 10.1038/nsmb.2366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S., Troyanovsky R. B. and Troyanovsky S. M. (2010). Spontaneous assembly and active disassembly balance adherens junction homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3528-3533. 10.1073/pnas.0911027107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudrisier D., Riond J., Mazarguil H., Gairin J. E. and Joly E. (2001). Cutting edge: CTLs rapidly capture membrane fragments from target cells in a TCR signaling-dependent manner. J. Immunol. 166, 3645-3649. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indra I., Hong S., Troyanovsky R., Kormos B. and Troyanovsky S. (2013). The adherens junction: a mosaic of cadherin and nectin clusters bundled by actin filaments. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 2546-2554. 10.1038/jid.2013.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens E. M., Mathieu C., Palermo L. M., Hardie D., Horvat B., Moscona A. and Porotto M. (2015). Measles fusion machinery is dysregulated in neuropathogenic variants. mBio 6, e02528 10.1128/mBio.02528-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyuncu O. O., Perlman D. H. and Enquist L. W. (2013). Efficient retrograde transport of pseudorabies virus within neurons requires local protein synthesis in axons. Cell Host Microbe 13, 54-66. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurita S., Ogita H. and Takai Y. (2011). Cooperative role of nectin-nectin and nectin-afadin interactions in formation of nectin-based cell-cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36297-36303. 10.1074/jbc.M111.261768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakari S., Ohnishi H., Jin F. J., Kaneko Y., Murata T., Murata Y., Okazawa H. and Matozaki T. (2008). Trans-endocytosis of CD47 and SHPS-1 and its role in regulation of the CD47-SHPS-1 system. J. Cell Sci. 121, 1213-1223. 10.1242/jcs.025015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFrance M. E., Farrow M. A., Chandrasekaran R., Sheng J., Rubin D. H. and Lacy D. B. (2015). Identification of an epithelial cell receptor responsible for Clostridium difficile TcdB-induced cytotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7073-7078. 10.1073/pnas.1500791112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb R. A. and Parks G. (2013). Paramyxoviridae. In Fields Virology, Vol. 1 (ed. Knipe D. M. and Howley P. M.), pp. 957-995. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster K. Z. and Pfeiffer J. K. (2010). Limited trafficking of a neurotropic virus through inefficient retrograde axonal transport and the type I interferon response. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000791 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D. M. P., Patterson C. E., Gales T. L., D'Orazio J. L., Vaughn M. M. and Rall G. F. (2000). Measles virus spread between neurons requires cell contact but not CD46 expression, syncytium formation, or extracellular virus production. J. Virol. 74, 1908-1918. 10.1128/JVI.74.4.1908-1918.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard V. H., Sinn P. L., Hodge G., Miest T., Devaux P., Oezguen N., Braun W., McCray P. B. Jr., McChesney M. B. and Cattaneo R. (2008). Measles virus blind to its epithelial cell receptor remains virulent in rhesus monkeys but cannot cross the airway epithelium and is not shed. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 2448-2458. 10.1172/JCI35454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. E., Wahl J. K. III, Sass K. M., Jensen P. J., Johnson K. R. and Wheelock M. J. (1997). Cross-talk between adherens junctions and desmosomes depends on plakoglobin. J. Cell Biol. 136, 919-934. 10.1083/jcb.136.4.919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow M., Lemon K., de Vries R. D., McQuaid S., Millar E. L., van Amerongen G., Yuksel S., Verburgh R. J., Osterhaus A. D., de Swart R. L. et al. (2013). Measles virus infection of epithelial cells in the macaque upper respiratory tract is mediated by subepithelial immune cells. J. Virol. 87, 4033-4042. 10.1128/JVI.03258-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow M., McQuaid S., Milner D., de Swart R. L. and Duprex W. P. (2015). Pathological consequences of systemic measles virus infection. J. Pathol. 235, 253-265. 10.1002/path.4457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhortova N. R., Askovich P., Patterson C. E., Gechman L. A., Gerard N. P. and Rall G. F. (2007). Neurokinin-1 enables measles virus trans-synaptic spread in neurons. Virology 362, 235-244. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston D. J., Dickinson S. and Nobes C. D. (2003). Rac-dependent trans-endocytosis of ephrinBs regulates Eph-ephrin contact repulsion. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 879-888. 10.1038/ncb1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo M., Generous A., Sinn P. L. and Cattaneo R. (2015). Connections matter–how viruses use cell-cell adhesion components. J. Cell Sci. 128, 431-439. 10.1242/jcs.159400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo M., Navaratnarajah C. K. and Cattaneo R. (2014a). Structural basis of efficient contagion: measles variations on a theme by parainfluenza viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 5, 16-23. 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo M., Navaratnarajah C. K., Willenbring R. C., Maroun J. W., Iankov I., Lopez M., Sinn P. L. and Cattaneo R. (2014b). Different roles of the three loops forming the adhesive interface of nectin-4 in measles virus binding and cell entry, nectin-4 homodimerization, and heterodimerization with nectin-1. J. Virol. 88, 14161-14171. 10.1128/JVI.02379-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda M., Kubo A., Furuse M. and Tsukita S. (2004). A peculiar internalization of claudins, tight junction-specific adhesion molecules, during the intercellular movement of epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 117, 1247-1257. 10.1242/jcs.00972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn C. L., Wimmer E. and Racaniello V. R. (1989). Cellular receptor for poliovirus: molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of a new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Cell 56, 855-865. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90690-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino-Gracia J., Garcia-Mayoral M. F. and Rodriguez-Crespo I. (2011). The association of viral proteins with host cell dynein components during virus infection. FEBS J. 278, 2997-3011. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08252.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mina M. J., Metcalf C. J. E., de Swart R. L., Osterhaus A. D. M. E. and Grenfell B. T. (2015). Long-term measles-induced immunomodulation increases overall childhood infectious disease mortality. Science 348, 694-699. 10.1126/science.aaa3662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi A., Nakanishi H., Kimura K., Matsubara K., Ozaki-Kuroda K., Katata T., Honda T., Kiyohara Y., Heo K., Higashi M. et al. (2002). Nectin: an adhesion molecule involved in formation of synapses. J. Cell Biol. 156, 555-565. 10.1083/jcb.200103113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison J. H., Guevara R. B., Marcano A. C., Saenz D. T., Fadel H. J., Rogstad D. K. and Poeschla E. M. (2014). Feline immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins antagonize tetherin through a distinctive mechanism that requires virion incorporation. J. Virol. 88, 3255-3272. 10.1128/JVI.03814-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlebach M. D., Mateo M., Sinn P. L., Prüfer S., Uhlig K. M., Leonard V. H. J., Navaratnarajah C. K., Frenzke M., Wong X. X., Sawatsky B. et al. (2011). Adherens junction protein nectin-4 is the epithelial receptor for measles virus. Nature 480, 530-533. 10.1038/nature10639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrete O. A., Levroney E. L., Aguilar H. C., Bertolotti-Ciarlet A., Nazarian R., Tajyar S. and Lee B. (2005). EphrinB2 is the entry receptor for Nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Nature 436, 401-405. 10.1038/nature03838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrby E. (1971). The effect of a carbobenzoxy tripeptide on the biological activities of measles virus. Virology 44, 599-608. 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90374-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyce R. S., Bondre D. G., Ha M. N., Lin L.-T., Sisson G., Tsao M.-S. and Richardson C. D. (2011). Tumor cell marker PVRL4 (nectin 4) is an epithelial cell receptor for measles virus. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002240 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]