Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation is the most frequent sustained arrhythmia. Atrial fibrillation often recurs after restoration of normal sinus rhythm. Antiarrhythmic drugs have been widely used to prevent recurrence. This is an update of a review previously published in 2006, 2012 and 2015.

Objectives

To determine the effects of long‐term treatment with antiarrhythmic drugs on death, stroke, drug adverse effects and recurrence of atrial fibrillation in people who had recovered sinus rhythm after having atrial fibrillation.

Search methods

We updated the searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase in January 2019, and ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO ICTRP in February 2019. We checked the reference lists of retrieved articles, recent reviews and meta‐analyses.

Selection criteria

Two authors independently selected randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing any antiarrhythmic drug with a control (no treatment, placebo, drugs for rate control) or with another antiarrhythmic drug in adults who had atrial fibrillation and in whom sinus rhythm was restored, spontaneously or by any intervention. We excluded postoperative atrial fibrillation.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed quality and extracted data. We pooled studies, if appropriate, using Mantel‐Haenszel risk ratios (RR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All results were calculated at one year of follow‐up or the nearest time point.

Main results

This update included one new study (100 participants) and excluded one previously included study because of double publication. Finally, we included 59 RCTs comprising 20,981 participants studying quinidine, disopyramide, propafenone, flecainide, metoprolol, amiodarone, dofetilide, dronedarone and sotalol. Overall, mean follow‐up was 10.2 months.

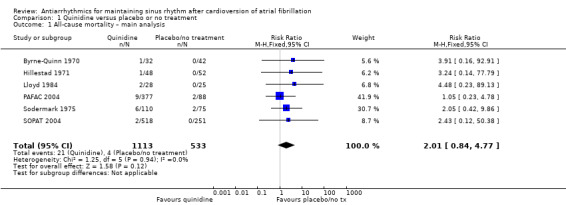

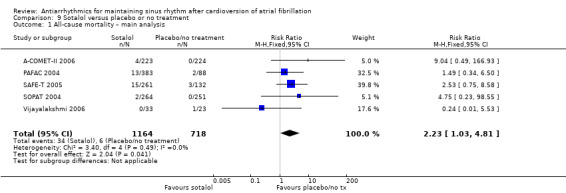

All‐cause mortality

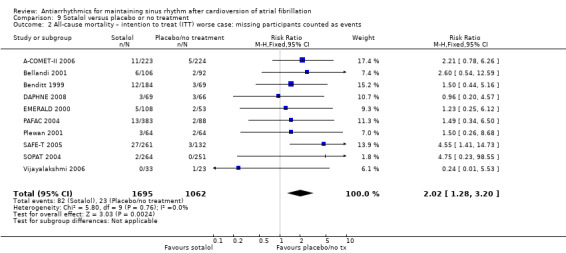

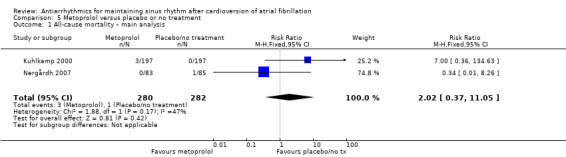

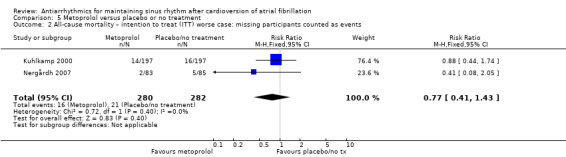

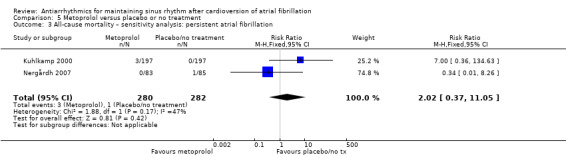

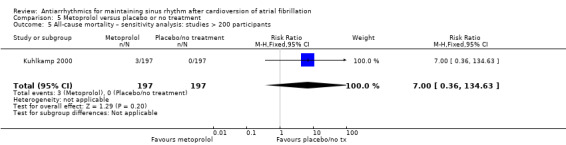

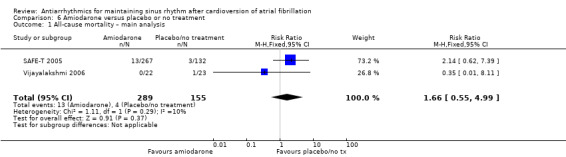

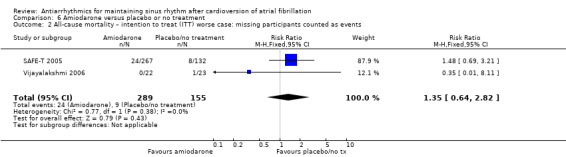

High‐certainty evidence from five RCTs indicated that treatment with sotalol was associated with a higher all‐cause mortality rate compared with placebo or no treatment (RR 2.23, 95% CI 1.03 to 4.81; participants = 1882). The number need to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) for sotalol was 102 participants treated for one year to have one additional death. Low‐certainty evidence from six RCTs suggested that risk of mortality may be higher in people taking quinidine (RR 2.01, 95% CI 0.84 to 4.77; participants = 1646). Moderate‐certainty evidence showed increased RR for mortality but with very wide CIs for metoprolol (RR 2.02, 95% CI 0.37 to 11.05, 2 RCTs, participants = 562) and amiodarone (RR 1.66, 95% CI 0.55 to 4.99, 2 RCTs, participants = 444), compared with placebo.

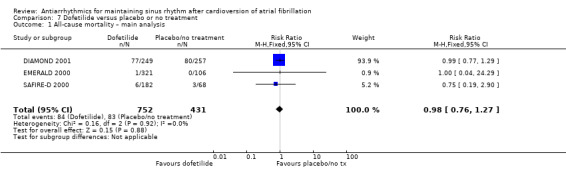

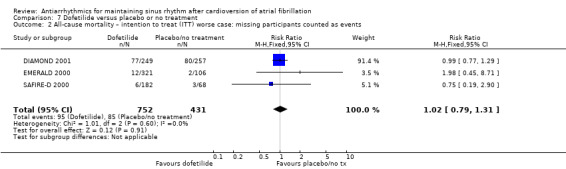

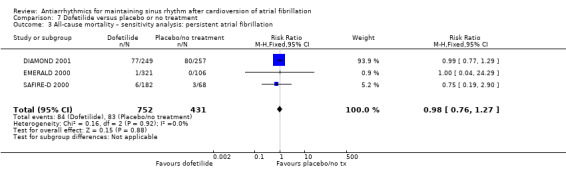

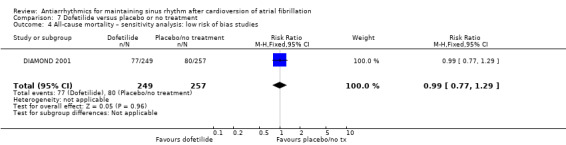

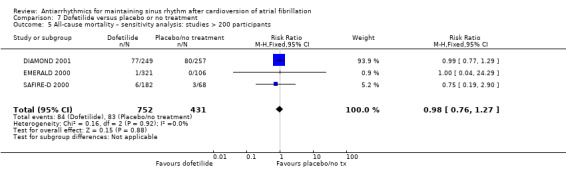

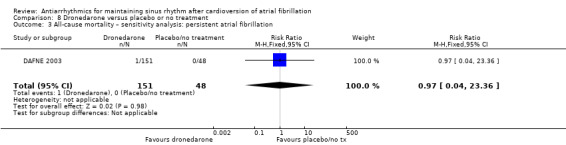

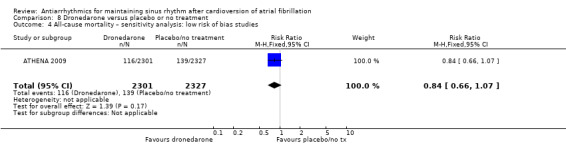

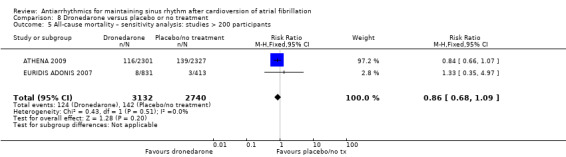

We found little or no difference in mortality with dofetilide (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.27; moderate‐certainty evidence) or dronedarone (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.09; high‐certainty evidence) compared to placebo/no treatment. There were few data on mortality for disopyramide, flecainide and propafenone, making impossible a reliable estimation for those drugs.

Withdrawals due to adverse events

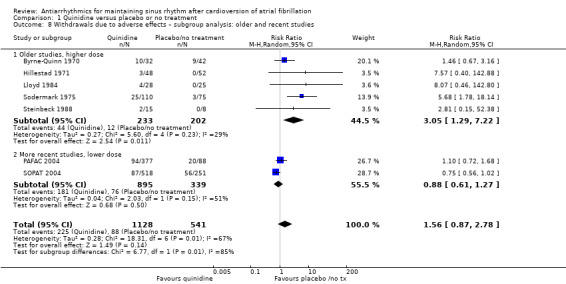

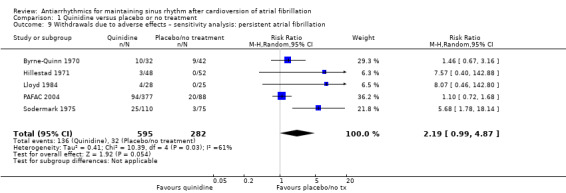

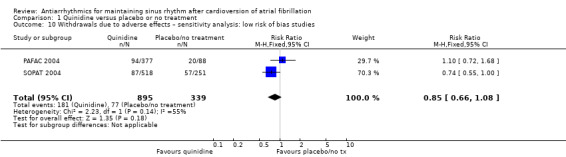

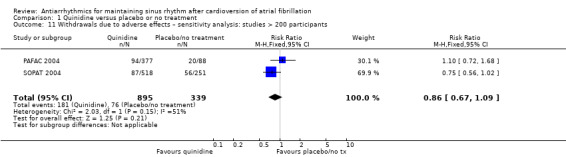

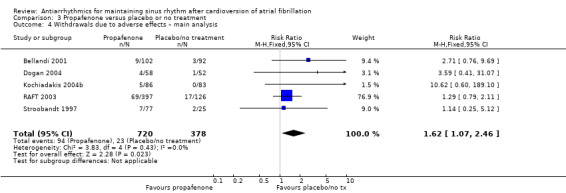

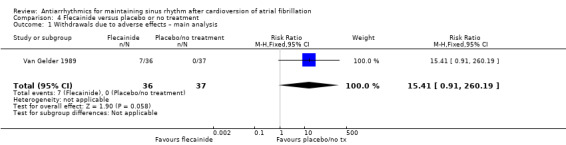

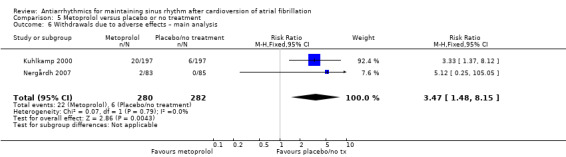

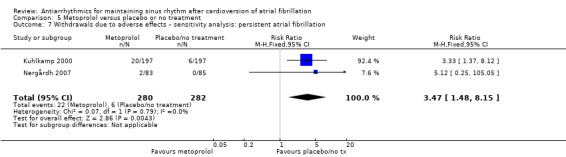

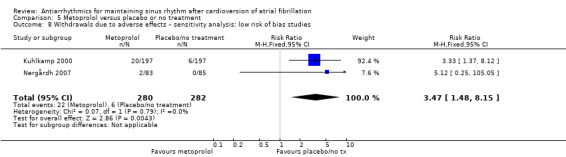

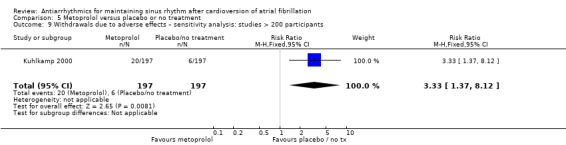

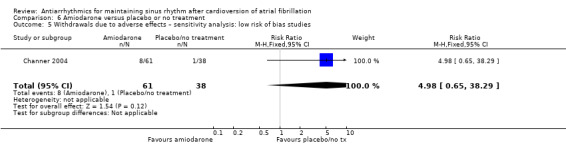

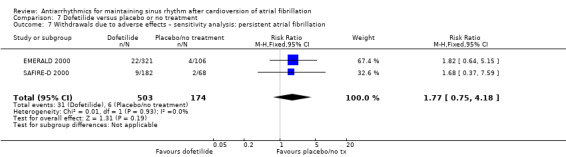

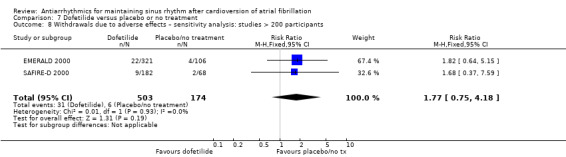

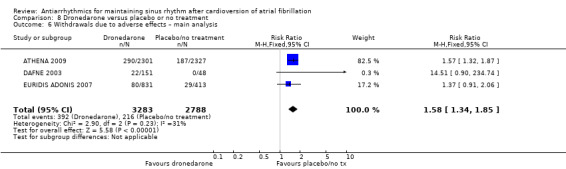

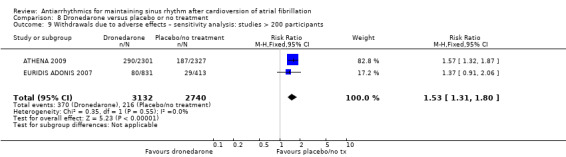

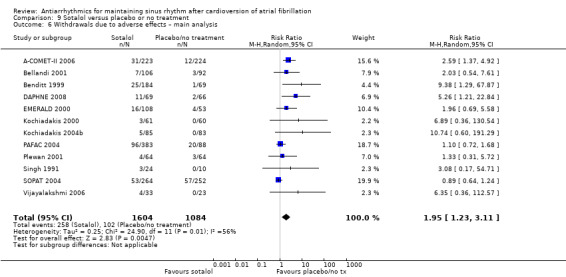

All analysed drugs increased withdrawals due to adverse effects compared to placebo or no treatment (quinidine: RR 1.56, 95% CI 0.87 to 2.78; disopyramide: RR 3.68, 95% CI 0.95 to 14.24; propafenone: RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.46; flecainide: RR 15.41, 95% CI 0.91 to 260.19; metoprolol: RR 3.47, 95% CI 1.48 to 8.15; amiodarone: RR 6.70, 95% CI 1.91 to 23.45; dofetilide: RR 1.77, 95% CI 0.75 to 4.18; dronedarone: RR 1.58, 95% CI 1.34 to 1.85; sotalol: RR 1.95, 95% CI 1.23 to 3.11). Certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low for disopyramide, amiodarone, dofetilide and flecainide; moderate to high for the remaining drugs.

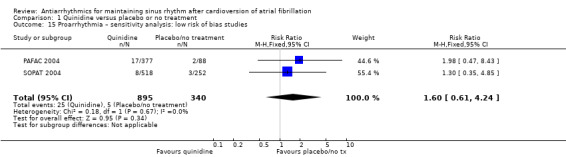

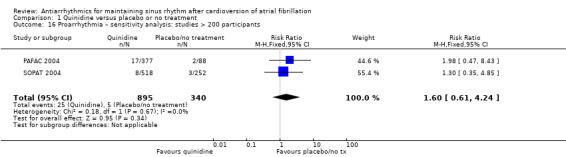

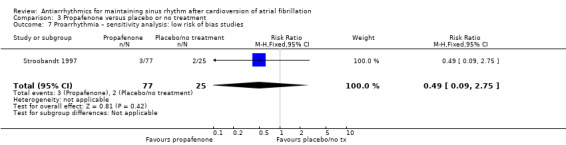

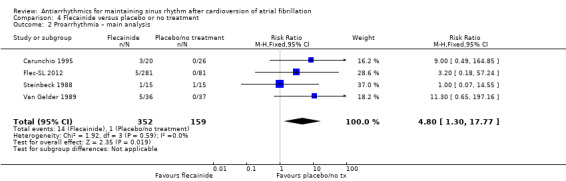

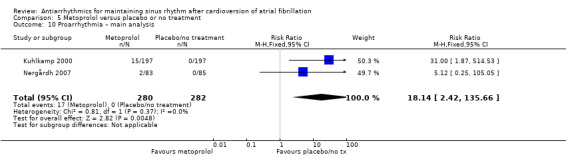

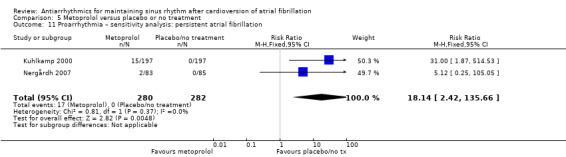

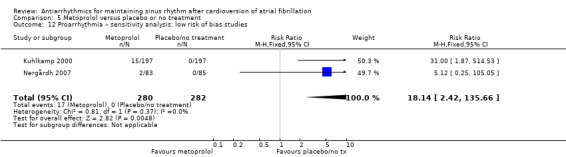

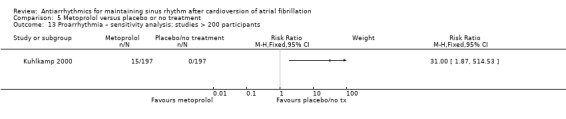

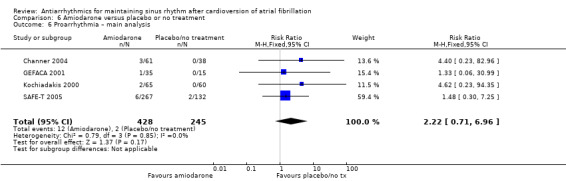

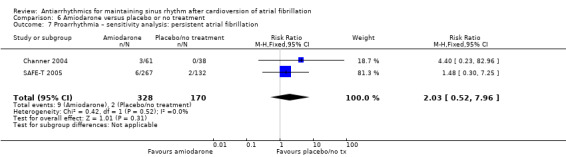

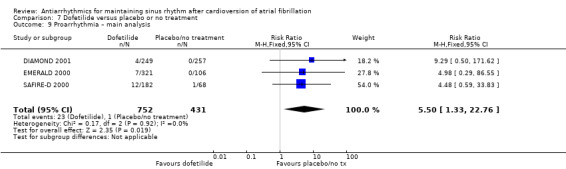

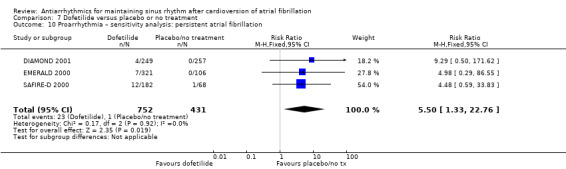

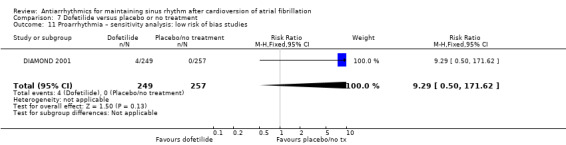

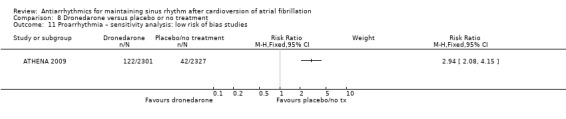

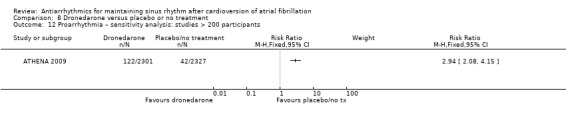

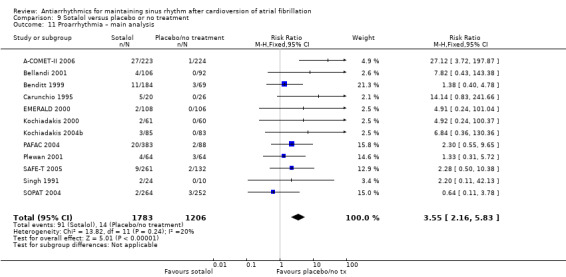

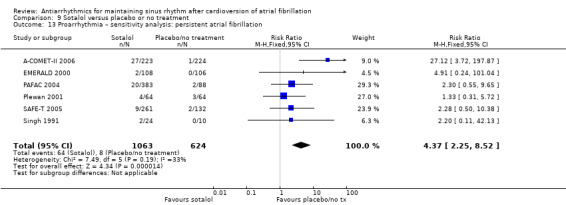

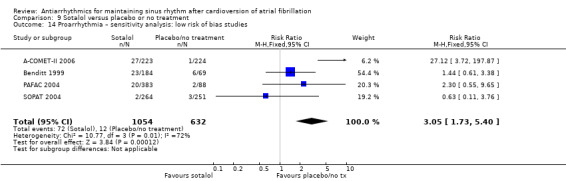

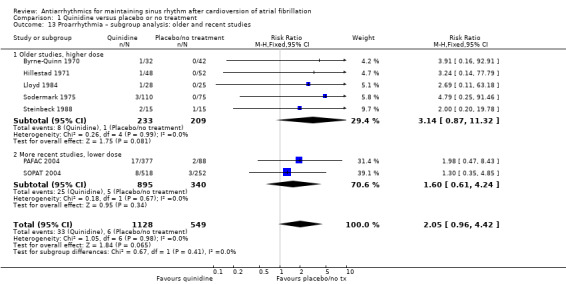

Proarrhythmia

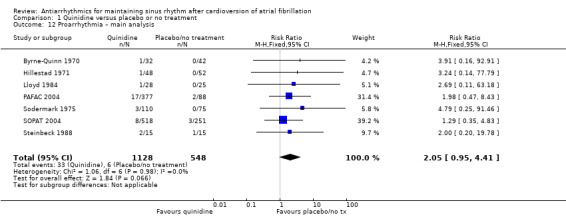

Virtually all studied antiarrhythmics showed increased proarrhythmic effects (counting both tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias attributable to treatment) (quinidine: RR 2.05, 95% CI 0.95 to 4.41; disopyramide: no data; flecainide: RR 4.80, 95% CI 1.30 to 17.77; metoprolol: RR 18.14, 95% CI 2.42 to 135.66; amiodarone: RR 2.22, 95% CI 0.71 to 6.96; dofetilide: RR 5.50, 95% CI 1.33 to 22.76; dronedarone: RR 1.95, 95% CI 0.77 to 4.98; sotalol: RR 3.55, 95% CI 2.16 to 5.83); with the exception of propafenone (RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.39 to 4.47) for which the certainty of evidence was very low and we were uncertain about the effect. Certainty of the evidence for this outcome for the other drugs was moderate to high.

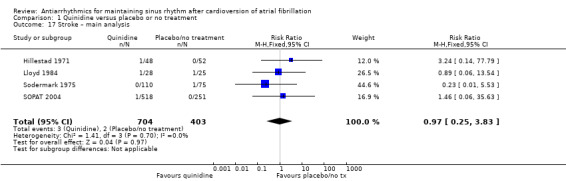

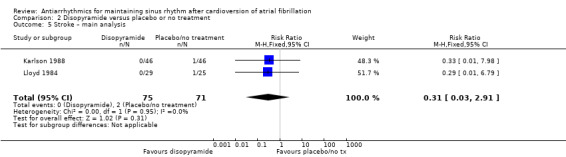

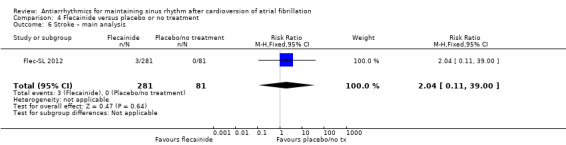

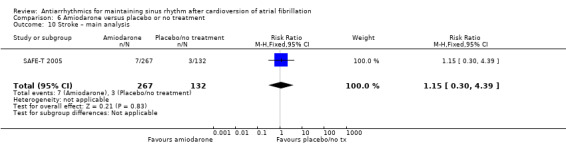

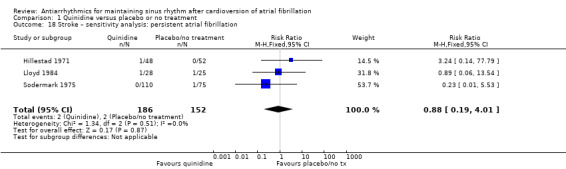

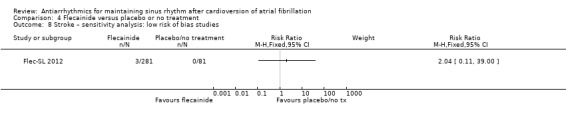

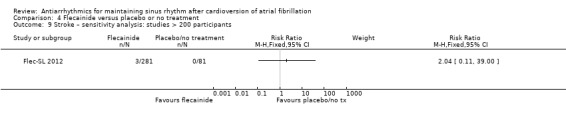

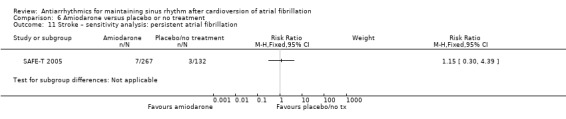

Stroke

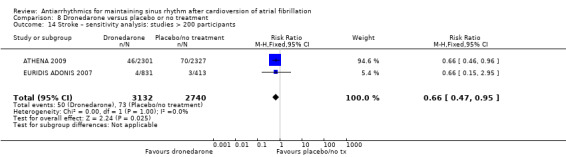

Eleven studies reported stroke outcomes with quinidine, disopyramide, flecainide, amiodarone, dronedarone and sotalol. High‐certainty evidence from two RCTs suggested that dronedarone may be associated with reduced risk of stroke (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.95; participants = 5872). This result is attributed to one study dominating the meta‐analysis and has yet to be reproduced in other studies. There was no apparent effect on stroke rates with the other antiarrhythmics.

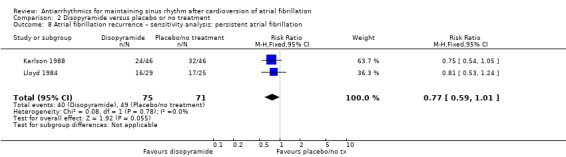

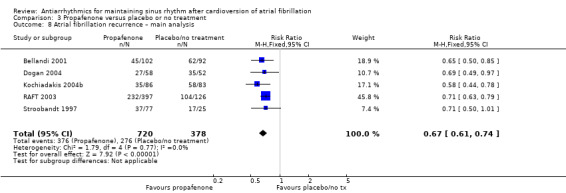

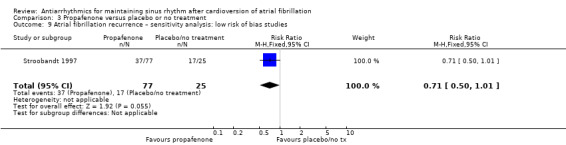

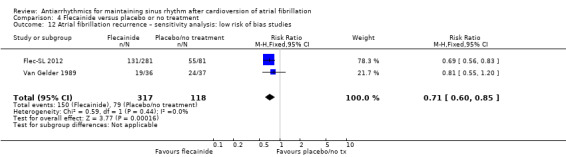

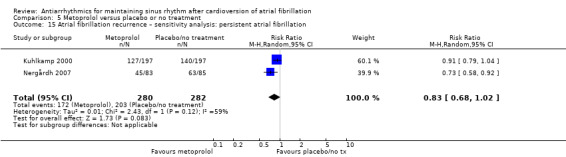

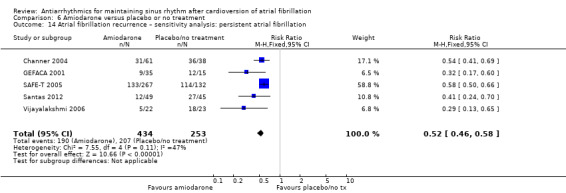

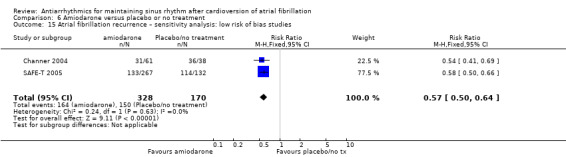

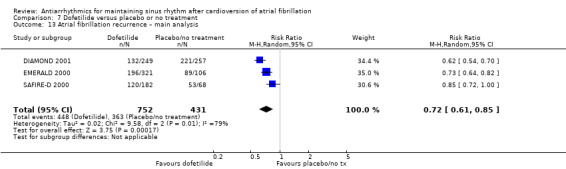

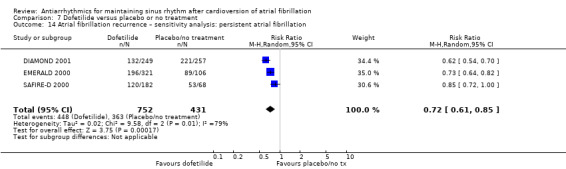

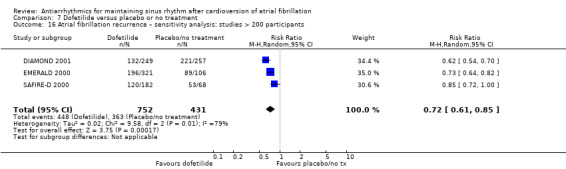

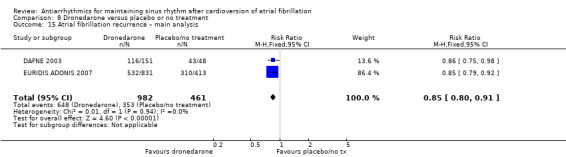

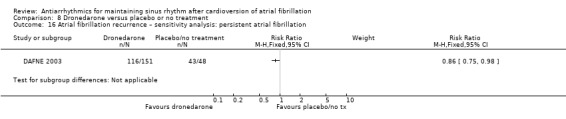

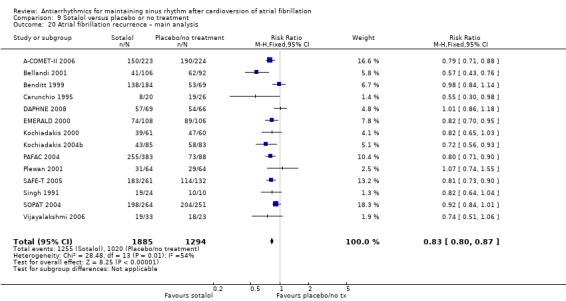

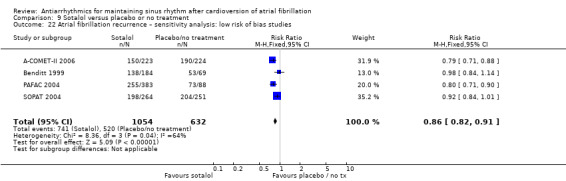

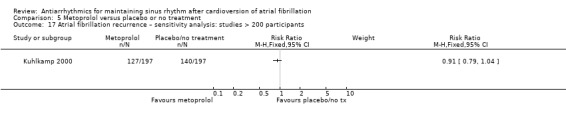

Recurrence of atrial fibrillation

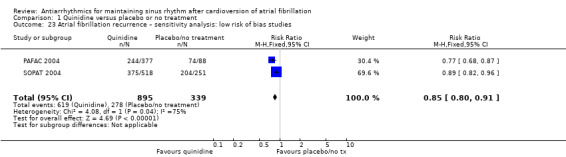

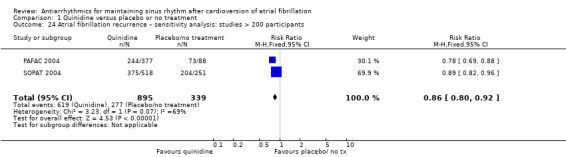

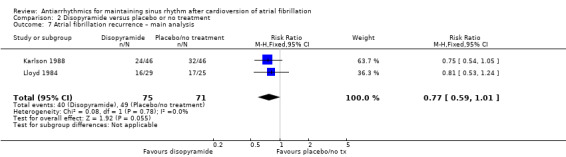

Moderate‐ to high‐certainty evidence, with the exception of disopyramide which was low‐certainty evidence, showed that all analysed drugs, including metoprolol, reduced recurrence of atrial fibrillation (quinidine: RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.88; disopyramide: RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.01; propafenone: RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.74; flecainide: RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.77; metoprolol: RR 0.83 95% CI 0.68 to 1.02; amiodarone: RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.58; dofetilide: RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.85; dronedarone: RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.91; sotalol: RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.87). Despite this reduction, atrial fibrillation still recurred in 43% to 67% of people treated with antiarrhythmics.

Authors' conclusions

There is high‐certainty evidence of increased mortality associated with sotalol treatment, and low‐certainty evidence suggesting increased mortality with quinidine, when used for maintaining sinus rhythm in people with atrial fibrillation. We found few data on mortality in people taking disopyramide, flecainide and propafenone, so it was not possible to make a reliable estimation of the mortality risk for these drugs. However, we did find moderate‐certainty evidence of marked increases in proarrhythmia and adverse effects with flecainide.

Overall, there is evidence showing that antiarrhythmic drugs increase adverse events, increase proarrhythmic events and some antiarrhythmics may increase mortality. Conversely, although they reduce recurrences of atrial fibrillation, there is no evidence of any benefit on other clinical outcomes, compared with placebo or no treatment.

Plain language summary

Antiarrhythmics for maintaining sinus rhythm (normal heartbeat) after reversing atrial fibrillation (correcting an irregular heartbeat)

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of antiarrhythmic medicines on mortality (death), stroke, side effects that cause people to stop taking the medicine and recurrences of irregular heartbeat, in people who had recovered normal heart rhythm after having atrial fibrillation (a type of irregular heartbeat).

Background

Atrial fibrillation is a disease where the heart rhythm is irregular (called arrhythmia) and often, but not always, too fast. Atrial fibrillation may produce complications, either in the heart (heart failure, fainting) or in other organs by causing embolisms. Embolisms are blood clots that form in the cavities of the heart which may then travel to other places, for example the brain.

Atrial fibrillation can be reverted, restoring normal heart rhythm, by using medicines or a controlled electrical shock. However, a major problem is that atrial fibrillation frequently recurs. A variety of medicines have been used to avoid these recurrences and keep the normal heart rhythm.

Study characteristics

This is an update of a review previously published in 2006, 2012 and 2015, and includes results of a search for new studies in January 2019. We found 59 studies testing various antiarrhythmic drugs and involving 20,981 participants. The average age of participants was 65 years. The most frequent diseases were hypertension (high blood pressure) and diseases of the arteries and valves of the heart. We found studies for nine medicines: quinidine, disopyramide, propafenone, flecainide, metoprolol, amiodarone, dofetilide, dronedarone and sotalol.

Key results and certainty of the evidence

High‐certainty evidence from five studies found that deaths from any cause were twice as high in people taking sotalol compared with people taking a placebo (dummy treatment) or no treatment. We calculated that one extra person would die for every 102 people taking sotalol for one year. Evidence for quinidine was low certainty, but the average effect across six studies suggested that people who took quinidine may have a higher risk of death compared with people taking no treatment or placebo. However, the evidence was not strong enough to rule out the possibility that there was no increased risk of death with quinidine. We found few data on mortality for disopyramide, flecainide and propafenone, meaning that we are uncertain of the effect of these drugs on mortality. We found no clear evidence that the other medicines we studied had any effect on risk of death.

We found that people taking any of these medicines were more likely to stop taking them due to side effects, compared with people not taking them. We are less certain of the results for disopyramide, amiodarone, dofetilide and flecainide because the low‐certainty evidence mostly came from small studies with design limitations. Evidence was moderate or high for the other medicines.

One particular side effect of antiarrhythmic medications is proarrhythmia, which means that people have new or more frequent problems with irregular heartbeats. We found high‐certainty evidence that people taking quinidine or metoprolol had a higher risk of proarrhythmia than people taking no treatment or placebo. Moderate‐certainty evidence indicated a similar increased risk for flecainide, amiodarone, dofetilide, dronedarone and sotalol. Evidence from these studies was moderate certainty due to problems with study limitations, smaller size or imprecise results. We are uncertain of the effect of propafenone on proarrhythmia as we only had very low‐certainty evidence for this medicine. None of the disopyramide studies reported how many people had proarrhythmia.

We found high‐certainty evidence that dronedarone may reduce the risk of stroke. There was no evidence of an effect of sotalol (moderate‐certainty evidence); amiodarone, flecainide, quinidine (all low‐certainty evidence) or disopyramide (very low‐certainty evidence) on risk of stroke. No studies reported risk of stroke with propafenone, metoprolol or dofetilide.

Moderate‐ to high‐certainty evidence, except disopyramide which was low certainty, showed that all the medicines we assessed reduced recurrence of atrial fibrillation, compared with not taking any treatment or taking a placebo. However, atrial fibrillation still recurred in about half of participants (43% to 67%) treated with antiarrhythmics.

Overall, It is unclear whether long‐term treatment with antiarrhythmic medicines carries benefits that outweigh their risks for this group of people.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained arrhythmia and its incidence increases substantially with age (Go 2001; Knuiman 2014; Ruigomez 2002). Atrial fibrillation is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, due to stroke, other embolic complications and heart failure (Benjamin 1998; Heeringa 2006; Krahn 1995; Stewart 2002). In high‐income countries, atrial fibrillation has grown progressively since the 1990s as a contributing cause of hospitalisation and death (Ayala 2003; Chugh 2014; Wattigney 2003).

In people who have atrial fibrillation, normal sinus rhythm is interrupted by periods of atrial fibrillation that may be either symptomatic or asymptomatic. Symptoms can be mild (e.g. palpitations, breathlessness or reduced effort capacity) or severe, causing syncope, heart failure or acute coronary syndrome. Many of the symptoms caused by atrial fibrillation are related to the degree of tachycardia and can be improved by either controlling heart rate (rate control strategy) or converting atrial fibrillation to normal sinus rhythm by electrical or pharmacological means (rhythm control strategy).

Most patients alternate between atrial fibrillation and sinus rhythm. The frequency and duration of atrial fibrillation are highly variable, both within patients and between patients, and are employed to classify this arrhythmia (AHA/ACC/HRS 2014; ESC 2016; NICE 2014). If the arrhythmia terminates spontaneously, atrial fibrillation is designated as 'paroxysmal', and it may or may not recur. When atrial fibrillation is sustained beyond seven days, it is designated as 'persistent'. Termination with pharmacological or electrical intervention does not change the designation. When atrial fibrillation is first detected, and it is not known if it will resolve or persist, it is designated 'recent‐onset' or simply 'first‐detected' atrial fibrillation. Finally, 'permanent' atrial fibrillation refers to persistent atrial fibrillation where cardioversion has failed or has not been attempted because it is considered that there is no possibility to restore sinus rhythm. An individual patient can show different classes of atrial fibrillation over time.

Description of the intervention

Many patients recover sinus rhythm spontaneously after an episode of recent‐onset atrial fibrillation, as many as 70% in some studies (Geleris 2001). Electrical and pharmacological cardioversion are very effective in restoring sinus rhythm, even in long‐standing persistent atrial fibrillation. However, one major problem is that recurrence of atrial fibrillation occurs frequently. The risk of recurrence of atrial fibrillation is dependent on age, duration of the atrial fibrillation, and the existence and severity of underlying heart disease (Flaker 1995; Frick 2001). The overall rate of recurrence of atrial fibrillation without treatment is high; of patients who have converted to sinus rhythm, only 20% to 30% will have remained in sinus rhythm one year later (AFFIRM 2002; Golzari 1996; Van Gelder 1996).

Long‐term antiarrhythmic therapy has been widely used to prevent the recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Antiarrhythmic drugs are usually grouped into four classes following the classification by Vaughan Williams (Vaughan Williams 1984). Class I drugs are those with a direct membrane action (sodium channel blockade), subdivided to Ia, Ib and Ic depending on specific effects on conduction and repolarisation; class II drugs are beta‐blockers; class III drugs are those that prolong repolarisation; and class IV drugs are calcium channel blockers. There is evidence that several class I, class III and maybe class II antiarrhythmic drugs are more effective than placebo for maintaining sinus rhythm (Miller 2000; Nichol 2002). However, some questions remain concerning the long‐term use of antiarrhythmic drugs.

How the intervention might work

It has been assumed that keeping patients in sinus rhythm would improve their quality of life and reduce the risks of embolism, stroke, heart failure or increased mortality that are associated with atrial fibrillation (Anter 2009). However, this has not been confirmed and, unfortunately, many of the trials with antiarrhythmic drugs have focused only on maintenance of sinus rhythm and have not assessed other relevant outcomes (Connolly 2000). Overall, rhythm control strategy, using antiarrhythmics to maintain sinus rhythm, has shown no clear benefit on clinical outcomes (e.g. mortality or stroke) in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) compared to a rate control strategy (Caldeira 2012; Chatterjee 2013; Sethi 2017).

Chronic treatment with antiarrhythmic drugs can be associated with severe adverse effects, including the potential induction of life‐threatening arrhythmias (a phenomenon called proarrhythmia). Adverse effects could compromise any benefits of maintaining sinus rhythm, or even outweigh them, leading to worse outcomes overall. In fact, the results of some trials show increased mortality associated with the long‐term use of some antiarrhythmics, as in the case with quinidine (Coplen 1990; SPAF 1992), or flecainide (CAST 1991). Finally, it is not known if all antiarrhythmic drugs are equivalent in their effectiveness and safety in the treatment of atrial fibrillation.

Why it is important to do this review

Many trials have studied long‐term treatment with diverse antiarrhythmic drugs for maintaining sinus rhythm, sometimes compared to placebo and sometimes compared to other antiarrhythmic drugs. Attempts to summarise this evidence in systematic reviews of trials or meta‐analyses have been incomplete. They were combined in one narrative review (Golzari 1996); trials using different antiarrhythmics and with very dissimilar lengths of treatment were pooled together (Nichol 2002); and outcomes other than sinus rhythm maintenance were not evaluated (Miller 2000). Consequently, we planned to conduct a more exhaustive systematic review of RCTs studying the long‐term use of antiarrhythmic drugs to maintain sinus rhythm and aimed to determine their effects not only on the recurrence of atrial fibrillation but also on other important clinical outcomes.

After the first publication of this review, another meta‐analysis on the same subject was published by Freemantle and colleagues (Freemantle 2011). The meta‐analysis employed a mixed treatment comparison method, combining the estimates obtained from direct and indirect comparisons in a network of trials. Network meta‐analysis represents an interesting extension of traditional pair‐wise meta‐analyses and can potentially provide a more complete overview of a health set. However, appropriate use of these methods requires strict assumptions and standardisation (Caldwell 2015). Although assumptions underlying classical pair‐wise meta‐analyses are well understood, the conduction of network meta‐analysis still poses multiple challenges that should be carefully considered when using such methods (Cipriani 2013; Tonin 2017).

In any case, after the first publication of this review in 2007 and the publication of the meta‐analysis by Freemantle 2011, several new RCTs have been published. We have systematically searched, assessed and, when found adequate, included any new trial in this domain in the successive updates of this review.

Objectives

To determine the effects of long‐term treatment with antiarrhythmic drugs on death, stroke, drug adverse effects and recurrence of atrial fibrillation in people who have recovered sinus rhythm after having atrial fibrillation.

The primary aim was to assess the effects of any antiarrhythmic drug compared with no antiarrhythmic treatment, that is, no treatment, placebo or treatment for rate control. If several antiarrhythmic drugs appeared to be effective the secondary aim was to compare them.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs with concealed allocation of participants to intervention or placebo. We excluded studies that were not randomised or that used an overt allocation method, where future assignments could be anticipated (e.g. by date, by entry number, alternating or rotating). We also excluded cross‐over studies (as the recurrence rate of atrial fibrillation is not uniform over time), cluster‐randomised studies (more prone to selection bias and to local variations in other intervention applied to people with atrial fibrillation) and studies where duration of follow‐up was less than six months.

Types of participants

Adults (aged more than 16 years) who had atrial fibrillation of any type and duration and in whom sinus rhythm had been restored, spontaneously or by any therapeutic intervention.

We excluded people with atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery and people with any condition causing a life expectancy of less than 12 months.

Types of interventions

To be included, studies must have randomly allocated participants to an intervention group or a control group. The intervention group must have received oral long‐term treatment with any available antiarrhythmic drug, at an appropriate dosing regimen, aimed at preventing new episodes of atrial fibrillation and maintaining sinus rhythm.

For the primary comparison of the review, the control group was no active treatment, this is, any of the following: placebo, no treatment or drugs for rate control (digoxin, calcium channel blockers, beta‐blockers).

For the secondary objective of evaluating differences between antiarrhythmic drugs, the control group could have been any of the other antiarrhythmic drugs that have shown effectiveness compared to no antiarrhythmic treatment.

Both groups, intervention and control, had to be similar with regard to cardiac disease (frequency, type and severity) and type of atrial fibrillation (especially duration). Also, both groups must have been treated similarly apart from the experimental therapy, that is:

the guidelines used to manage initiation, discontinuation, dose and surveillance of anticoagulation had to be the same in both the intervention and control groups;

management and drugs used for hypertension and heart failure had to be similar.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Adverse effects: withdrawals from taking the study drug caused by adverse events.

Adverse effects: proarrhythmia, including any of the following: sudden death, any new symptomatic arrhythmia (including symptomatic bradycardia), aggravation of existing arrhythmias (i.e. rapid atrial fibrillation) and new appearance on electrocardiogram (ECG) of QRS or QT widening that led to stopping treatment (Friedman 1998).

Stroke, all types.

Secondary outcomes

Recurrence of atrial fibrillation (number of participants who had a recurrence of atrial fibrillation during follow‐up).

Use of anticoagulation (number of participants started on long‐term treatment with anticoagulants at the end of follow‐up).

Heart failure.

We analysed all outcomes at 12 months. If a trial did not measure outcomes at this exact time point then we used the nearest measure point (e.g. at six, nine or 15 months instead of 12 months).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We updated the searches from 2005 (Appendix 1), 2010 (Appendix 2), and 2014 (Appendix 3) and reran them on 31 January 2019 (Appendix 4).

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (2019, Issue 1 of 12), MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 28 January 2019) and Embase (Ovid, 1980 to 2019 week 4).

We also searched two clinical trials registers; ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (up to 7 February 2019) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (up to 7 February 2019).

We applied the RCT filter for MEDLINE was the Cochrane sensitivity‐maximising RCT filter, and for Embase, terms as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2011).

Searching other resources

In addition, we checked the reference lists of retrieved studies and the reference lists of recent guidelines, meta‐analyses and general reviews on atrial fibrillation.

We applied no language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Any of the authors read the titles (and abstracts where available) and retrieved any publication that seemed to possibly meet the inclusion criteria. Two authors independently read the full texts of the studies that were retrieved and selected the trials that met the criteria for inclusion. We developed and used a predefined form for this task. We compared the selected trials and resolved any discrepancy by discussion and consensus between the authors. We checked the articles that were finally selected for the review to avoid duplication of data. We kept records of the selection process and prepared a PRISMA flowchart (PRISMA 2009).

Data extraction and management

Two authors (from LV, WJ, JB, CLL) extracted data independently using a data collection form specifically developed for this task. When necessary, we contacted the authors of primary studies for additional information. We checked the completed data forms for agreement and resolved any differences by discussion and consensus.

In addition to data relating to the outcomes of the review, we collected information on the following.

Study methods and design (randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding).

Baseline characteristics of participants (age, gender, frequency and type of heart disease, echocardiographic measures, duration and type of atrial fibrillation, as defined in each study and knowing that definitions employed were not always consistent).

Details of treatments (method of cardioversion employed, time interval between conversion to sinus rhythm and initiation of intervention, antiarrhythmic drugs used and dose, treatment used in control group, concomitant treatments (beta‐blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, antiplatelets and warfarin)).

Follow‐up duration, participants lost to follow‐up and withdrawals.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (from LV, EA, WJ, JB, CLL) independently assessed the risk of bias of the selected studies across the following domains recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017): random sequence generation, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and any other source of bias.

We resolved any differences of opinion by discussion and consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

We determined the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all outcomes as they were all dichotomous variables. If evidence of an effect appeared for any outcome and the control group rates of the outcomes were broadly similar, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) to prevent or produce, respectively, one adverse outcome for the specified duration of treatment. We used the pooled RR and the pooled rate from the control groups.

Unit of analysis issues

The review includes no cross‐over trials or cluster randomised trials. For trials with multiple time points, we included only data at one year (or the nearest time point). For trials comparing two antiarrhythmics and placebo or no treatment, we divided the placebo (or no treatment) group into two groups with smaller sample size, to include two different comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

We analysed the data on the basis of intention‐to‐treat. By default, we considered missing participants not to have experienced an event and we used the randomised number of participants as the denominator. Nevertheless, we also carried out the worst‐case scenario intention‐to‐treat‐analysis for all outcomes as a sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested heterogeneity using the Mantel‐Haenszel Chi2 test and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2011). If we found important heterogeneity, we searched for an explanation based on the differences in clinical characteristics of the included studies. If the studies were clinically very dissimilar, they were not statistically combined.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots to test for the presence of publication bias, based on the data for each primary and secondary outcome.

Data synthesis

We pooled data using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). If there was no heterogeneity, we calculated Mantel‐Haenszel RRs for all outcomes using a fixed‐effect model. If there was heterogeneity between studies, we calculated RRs using a random‐effects model.

We pooled data for all antiarrhythmic drugs and analysed them individually (for each specific drug).

'Summary of findings' table

We created 'Summary of findings' tables using the following outcomes: all‐cause mortality, withdrawals due to adverse effects, proarrhythmia, stroke and recurrence of atrial fibrillation. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the certainty of a body of evidence as it related to the studies which contributed data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes. We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) using GRADEpro GDT. We prepared a separate 'Summary of findings' table for each drug. We justified all decisions to downgrade the certainty of studies using footnotes and we made comments to aid reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Two authors (AT, CLL) made GRADE assessments and justified, documented and incorporated their judgements into reporting of results for each outcome.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Predefined subgroup analyses were:

paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and persistent atrial fibrillation;

people with heart failure compared to people who had never developed heart failure;

studies where warfarin was mandatory versus studies where warfarin was discretionary; and

people with a structurally normal heart ('lone' atrial fibrillation).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed by selectively pooling:

studies having low risk of bias in the following domains: allocation concealment, blinding and incomplete outcome data; and

studies including more than 200 participants.

In addition, we carried out the worst‐case scenario intention‐to‐treat‐analysis (i.e. considering all missing participants as having events) for all outcomes to test if any potential difference might have arisen due to losses to follow‐up.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We found 6332 references and assessed 205 articles in more detail for the previous publication of this review (Lafuente‐Lafuente 2015). We retrieved, translated, when needed, and assessed articles in Chinese, English, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Swedish. Finally, 59 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and had useable data. They comprised 20,981 participants in total.

Compared with the previous publication of this review in 2015, which searched the medical literature until January 2014, we read 2185 additional references (LV, CLL, AT), assessed in detail 22 new articles (LV, EA, CLL, WJ), included one new RCT (Chun 2014), and identified one ongoing study (Park 2017). The new included trial compared dronedarone and propafenone, added 100 more participants and reported only atrial fibrillation recurrence rates, but not mortality or adverse events.

During our process of checking papers for duplicate publications, we became aware that the data from one study we had previously included by the SVA‐4 Investigators (SVA‐4 2008a), was already reported in another included publication (ASAP 2003). Therefore, we removed this study from the analysis, and listed it with the main ASAP 2003 reference in the list of Included studies.

Figure 1 illustrates the selection of articles, following the PRISMA model. Agreement between authors was good for both selecting studies and extracting the data. Details of each included study are shown in the Characteristics of included studies table, and the reasons for exclusion are shown in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

1.

Selection of studies for inclusion. AF: atrial fibrillation.

Included studies

Participants

Entry criteria differed between studies in several aspects. In some trials, atrial fibrillation was documented in the history but participants were in sinus rhythm at the time of inclusion, while in other trials, participants were in atrial fibrillation and needed to be converted to sinus rhythm (only those converted were included in the review). The duration of atrial fibrillation when persistent, or the time from the last documented episode of atrial fibrillation when paroxysmal, was highly variable (from one month to one year, or no time limit in some studies). Some of the studies required atrial fibrillation to be symptomatic while others did not. Six studies enrolled both people with atrial fibrillation and people with atrial flutter. When available, we used only data from people with atrial fibrillation.

Regarding the type of atrial fibrillation, eight studies included exclusively paroxysmal or recent‐onset atrial fibrillation, 28 studies included only persistent atrial fibrillation (i.e. lasting more than seven days), and the remaining 23 studies included both types. Overall, 48% of the pooled population had persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation.

The mean age of participants varied from 46 to 72 years in the included studies and was 65 years in the pooled population. The proportion of participants having underlying heart disease varied widely, from 29% to 100%, with only one study selectively including people without structural heart disease (FAPIS 1996). The most frequent diseases were coronary artery disease (5% to 50% of participants), hypertension, and valvular abnormalities (less frequent in recent studies). The mean left ventricle ejection fraction was greater than 50% in almost all trials (exceptions being DIAMOND 2001; Kalusche 1994; Nergårdh 2007; Plewan 2001; Vijayalakshmi 2006).

Interventions

Twenty‐nine trials (with 13,443 participants) compared an antiarrhythmic with a control, 12 trials (4536 participants) compared two different antiarrhythmics and a control, and 18 trials (3,002 participants) compared two or more antiarrhythmics with each other. The comparator used in the 41 trials with control groups was a placebo in 32 trials, a beta‐blocker in two trials (DAPHNE 2008; Plewan 2001), digoxin in one trial (Steinbeck 1988), and no treatment in six trials (Flec‐SL 2012; Hillestad 1971; Santas 2012; Sodermark 1975; Van Gelder 1989; Vijayalakshmi 2006).

Drugs included in this review, for which there was at least one well‐designed RCT, were class IA: quinidine, disopyramide; class IC: flecainide, propafenone; class II (beta‐blockers): metoprolol; and class III: amiodarone, dofetilide, dronedarone and sotalol.

Follow‐up

The most frequent length of follow‐up was one year. It was shorter in 17 trials (six to nine months) and longer in six trials (15 to 19 months). Five trials followed participants for two years or more (AFFIRM Substudy 2003; ATHENA 2009; Kochiadakis 2000; Kochiadakis 2004a; Kochiadakis 2004b). We extracted and pooled all outcomes at one year of follow‐up or the nearest time point available. For studies with shorter duration of follow‐up, we used the last observation available. Overall, the mean follow‐up of the pooled population analysed was 10.2 months.

Excluded studies

Main reasons for exclusion of studies were not being controlled or randomised (43 studies), having a follow‐up shorter than six months (16 studies) and including in the control group participants who did not revert to sinus rhythm (10 studies). Additional details on excluded studies are given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

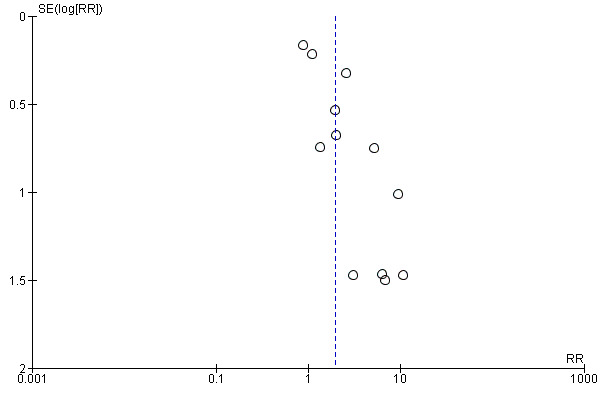

Risk of bias in included studies

There was asymmetry in the funnel plot of withdrawals because of adverse effects on treatment with sotalol (Figure 2). It showed fewer small studies on the left side (i.e. there were more small studies showing a trend to more withdrawals on active treatment). However, funnel plots for other outcomes with sotalol were symmetric, so we think the risk of substantial publication bias was low. Funnel plots for the remaining drugs were symmetric.

2.

Funnel plot of comparison: 9 Sotalol versus placebo/no treatment, outcome: 9.6 Withdrawals due to adverse effects – main analysis.

The results of the assessment of the risk of bias of included studies across different domains are showed in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All included studies were described as RCTs. However, only a minority detailed how the random number sequence was generated (18 studies, 30.5%) or how the allocation of participants was concealed (17 studies, 28.8%). Because of lack of details, the risk of bias on these items was unclear for the remaining studies.

Blinding

The majority of trials comparing an antiarrhythmic versus a control were described as blinded (of 41 trials: 25 were double‐blind and five single‐blind, the remaining 11 were open‐label). In contrast, most trials comparing two or more different antiarrhythmics were open‐label (15 out of 18). However, only 17 of the 25 studies said to be double‐blind adequately reported the method of blinding (and it was adequate in all cases). Nonetheless, we think that the risk of bias associated to this lack of adequate blinding is not very high because: 1. most outcomes assessed in this review were objective ones: recurrence of atrial fibrillation and proarrhythmia were established by ECG records, mortality and stroke are objective outcomes; 2. results from adequately double‐blind studies and open‐label studies were very consistent; 3. well described, adequate blinding was more frequent in studies comparing an active drug with no active treatment, which is the main comparison of the review.

Incomplete outcome data

Most studies adequately reported withdrawals and dropouts. The percentage of participants lost to follow‐up was detailed in 47 of the 59 included trials, was small (5% to 10%) and was well balanced across arms. However, virtually all studies only followed participants until atrial fibrillation recurred or until treatment was stopped for any reason. Therefore, data for some outcomes, such as mortality, were not extensive.

Selective reporting

All studies but three (Chun 2014; DAPHNE 2008; Santas 2012) had data on all‐cause mortality, all but two (ASAP 2003; PITAGORA 2008) on atrial fibrillation recurrence rates, and all but three (AFIB 1997; Chun 2014; Santas 2012) presented data for adverse effects, either withdrawals or proarrhythmia (Table 10). Other outcomes were less frequently reported: in studies with a placebo or no treatment arm, 11 trials reported stroke, to trials reported heart failure and none reported the actual frequency of anticoagulation. All studies reported the outcomes they had prespecified in the way they had prespecified.

1. Number of studies assessing each primary outcome.

| Primary outcomes | n trials reporting (n participants) | n trials NOT reporting (n participants) |

| All‐cause mortality | 39 (17,586) | 3a (393) |

| Cardiovascular mortality | Same as total mortality | Same as total mortality |

| Stroke | 11 (9139) | 30 (8840) |

| Adverse effects (proarrhythmia and withdrawals due to adverse effects) | 39 (16,558) | 3b (1421) |

Out of 41 studies comparing an active drug with a control group receiving no antiarrhythmic (total 17,979 participants).

aChun 2014; DAPHNE 2008; Santas 2012.

bAFIB 1997; Chun 2014; Santas 2012. Others studies did not reported proarrhythmia but reported withdrawals (DAPHNE 2008; Niu 2006; Villani 1992).

Other potential sources of bias

Conflict of interest could exist as almost all the studies included in the review were funded by the company manufacturing the antiarrhythmic drug tested.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Quinidine compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.

| Quinidine compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults in sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation Setting: hospital/community Intervention: quinidine Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no treatment | Risk with quinidine | |||||

| All‐cause mortality follow‐up: median 12 months | Study population | RR 2.01 (0.84 to 4.77) | 1646 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — | |

| 8 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (6 to 36) | |||||

| Withdrawals due to adverse effects follow‐up: median 12 months | Study population | RR 1.56 (0.87 to 2.78) | 1669 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec,d,e | Heterogeneity was high for the main analysis (I2 = 67%), but the test for subgroup differences indicated that the RR was higher in older studies which used a higher dose. | |

| 163 per 1000 | 254 per 1000 (142 to 452) | |||||

| Proarrhythmia follow‐up: median 12 months | Study population | RR 2.05 (0.95 to 4.41) | 1676 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Highc,f | — | |

| 11 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (10 to 48) | |||||

| Stroke follow‐up: median 12 months | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.25 to 3.83) | 1107 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,g | — | |

| 5 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (1 to 19) | |||||

| Recurrence of atrial fibrillation follow‐up: median 12 months | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.78 to 0.88) | 1624 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Highc | — | |

| 80.5 per 100 | 66.8 per 100 (62.8 to 70.8) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for study limitations: majority of studies were at low or unclear risk of bias for at least one of the key domains (allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data). bDowngraded one level for imprecision: confidence interval included no effect, the possibility of a beneficial effect and a strong harmful effect. cNot downgraded for study limitations, as the two studies contributing majority of weight were at low risk for key domains (allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data). dNot downgraded for inconsistency: although heterogeneity was high for the main analysis, this was partially explained by subgroup analysis. eDowngraded one level for imprecision: confidence interval included possibility of no effect or small beneficial effect as well as harmful effect. fNot downgraded for imprecision, although CI just included null. gDowngraded one level for imprecision: confidence interval included both important benefits and harms, and event rate was very low.

Summary of findings 2. Disopyramide compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.

| Disopyramide compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults in sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation Setting: hospital/community Intervention: disopyramide Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no treatment | Risk with disopyramide | |||||

| All‐cause mortality follow‐up: mean 12 months | Study population | RR 5.00 (0.25 to 101.37) | 92 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Anticipated absolute effects per 1000 could not be calculated because there were no deaths in the control group. Risks were the data from the RCT. | |

| 0/71 | 5/75 | |||||

| Withdrawals due to adverse effects follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 3.68 (0.95 to 14.24) | 146 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | — | |

| 28 per 1000 | 104 per 1000 (27 to 401) | |||||

| Proarrhythmia | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

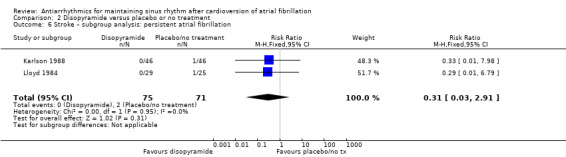

| Stroke follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 0.31 (0.03 to 2.91) | 146 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — | |

| 28 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (1 to 82) | |||||

| Recurrence of atrial fibrillation follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 0.77 (0.59 to 1.01) | 146 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | — | |

| 69.0 per 100 | 53.1 per 100 (40.7 to 69.7) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for study limitations: both studies had unclear risk of bias for one of the key domains. bDowngraded two levels for imprecision: very small sample size and wide confidence intervals including both important benefits and harms. cDowngraded one level for imprecision: very small sample size.

Summary of findings 3. Propafenone compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.

| Propafenone compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults in sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation Setting: hospital/community Intervention: propafenone Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no treatment | Risk with propafenone | |||||

| All‐cause mortality follow‐up: range 6–15 months | Study population | RR 0.19 (0.02 to 1.68) | 212 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Very few data available for this outcome: only 2 deaths reported in 5 included RCTs. | |

| 26 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (1 to 44) | |||||

| Withdrawals due to adverse effects follow‐up: range 6–15 months | Study population | RR 1.62 (1.07 to 2.46) | 1098 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 61 per 1000 | 99 per 1000 (65 to 150) | |||||

| Proarrhythmia follow‐up: range 6–15 months | Study population | RR 1.32 (0.39 to 4.47) | 381 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — | |

| 13 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (5 to 56) | |||||

| Stroke | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Recurrence of atrial fibrillation follow‐up: range 6–15 months | Study population | RR 0.67 (0.61 to 0.74) | 1098 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 73.0 per 100 | 48.9 per 100 (44.5 to 54.0) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for study limitations. All studies had unclear or high risk of bias in at least one of the three key domains (allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data). bDowngraded two levels for imprecision due to small sample size and confidence interval wide enough to include both important benefit and harm.

Summary of findings 4. Flecainide compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.

| Flecainide compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults in sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation Setting: hospital/community Intervention: flecainide Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no treatment | Risk with flecainide | |||||

| All‐cause mortality | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Withdrawals due to adverse effects follow‐up: mean 6 months | Study population | RR 15.41 (0.91 to 260) | 73 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Anticipated absolute effects per 1000 could not be calculated because there were no withdrawals in the control group. Risks were the data from the RCT. | |

| 0/37 | 7/36 | |||||

| Proarrhythmia follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 4.80 (1.30 to 17.7) | 511 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | — | |

| 6 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (8 to 112) | |||||

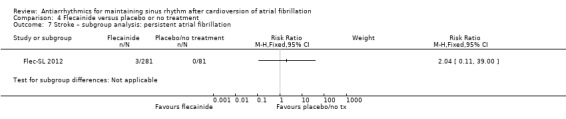

| Stroke follow‐up: mean 6 months | Study population | RR 2.04 (0.11 to 39) | 362 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Anticipated absolute effects per 1000 could not be calculated because there were no strokes in the control group. Risks were the data from the RCT. | |

| 0/81 | 3/281 | |||||

| Recurrence of atrial fibrillation follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 0.65 (0.55 to 0.77) | 511 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Highd | — | |

| 69.8 per 100 | 45.4 per 100 (38.4 to 53.8) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aNot downgraded for study limitations. the only included study was at high risk of bias for blinding (less relevant for this outcome) but low risk for other key domains. bDowngraded two levels for imprecision due to small sample size and wide confidence interval that included both possible harm and no effect. cDowngraded one level for study limitations; all studies were at high or unclear risk of bias in at least one of the key domains. dNot downgraded for study limitations. Majority of weight came from 2 largest studies which were at high risk of bias for blinding (less relevant for this outcome) but low risk for other key domains.

Summary of findings 5. Metoprolol compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.

| Metoprolol compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults in sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation Setting: hospital/community Intervention: metoprolol Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no treatment | Risk with Metoprolol | |||||

| All‐cause mortality follow‐up: mean 6 months | Study population | RR 2.02 (0.37 to 11.1) | 562 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 4 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 (1 to 39) | |||||

| Withdrawals due to adverse effects follow‐up: mean 6 months | Study population | RR 3.47 (1.48 to 8.1) | 562 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | — | |

| 21 per 1000 | 74 per 1000 (31 to 173) | |||||

| Proarrhythmia follow‐up: mean 6 months | Study population | RR 18.14 (2.42 to 135.6) | 562 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Anticipated absolute effects per 1000 could not be calculated because there were no events in the control group. Risks are the data from the RCTs. | |

| 0 / 282 | 17 / 280 | |||||

| Stroke | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Recurrence of atrial fibrillation follow‐up: mean 6 months | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.68 to 1.02) | 562 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | — | |

| 72.0 per 100 | 59.7 per 100 (49.0 to 73.4) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for imprecision. Confidence intervals included both possible harm and possible benefit. bDowngraded one level for inconsistency: high I2 statistic (59%) indicated heterogeneity and this could not be explored in subgroup analysis due to only two studies being included.

Summary of findings 6. Amiodarone compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.

| Amiodarone compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults in sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation Setting: hospital/community Intervention: amiodarone Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no treatment | Risk with amiodarone | |||||

| All‐cause mortality follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 1.66 (0.55 to 4.99) | 444 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 26 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 (14 to 129) | |||||

| Withdrawals due to adverse effects follow‐up: range 6–16 months | Study population | RR 6.70 (1.91 to 23.45) | 319 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | — | |

| 7 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (14 to 172) | |||||

| Proarrhythmia follow‐up: range 6–16 months | Study population | RR 2.22 (0.71 to 6.96) | 673 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea,d | — | |

| 8 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (6 to 57) | |||||

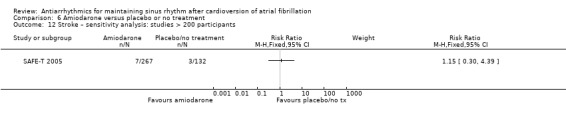

| Stroke follow‐up: mean 12 months | Study population | RR 1.15 (0.30 to 4.39) | 399 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe | — | |

| 23 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (7 to 100) | |||||

| Recurrence of atrial fibrillation follow‐up: median 12 months | Study population | RR 0.52 (0.46 to 0.58) | 812 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Highd | — | |

| 81.2 per 100 | 42.2 per 100 (37.3 to 47.1) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for imprecision: confidence interval included both possible benefit and harm. bDowngraded one level for study limitations: majority of weight was from studies with unclear or high risk of bias in key domains. cDowngraded one level for imprecision: small sample size. dNot downgraded for study limitations, as the majority weight was from studies at low risk of bias in all key domains. eDowngraded two levels for imprecision: small sample size and wide confidence interval which included both possible benefit and harm.

Summary of findings 7. Dofetilide compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.

| Dofetilide compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults in sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation Setting: hospital/community Intervention: dofetilide Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no treatment | Risk with dofetilide | |||||

| All‐cause mortality follow‐up: mean 12 months | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.76 to 1.27) | 1183 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 193 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (146 to 245) | |||||

| Withdrawals due to adverse effects follow‐up: mean 12 months | Study population | RR 1.77 (0.75 to 4.2) | 677 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — | |

| 34 per 1000 | 61 per 1000 (26 to 144) | |||||

| Proarrhythmia follow‐up: mean 12 months | Study population | RR 5.50 (1.33 to 22.8) | 1183 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 2 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (3 to 53) | |||||

| Stroke | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Recurrence of atrial fibrillation follow‐up: mean 12 months | Study population | RR 0.72 (0.61 to 0.85) | 1183 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec,d | — | |

| 84.2 per 100 | 60.6 per 100 (51.4 to 71.6) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for study limitations: majority of studies had unclear risk of selection bias. bDowngraded one level for imprecision: confidence interval included both possible benefit and harm. cNot downgraded for study limitations as 51% of weight came from a study with low risk of bias across all domains (but other two studies had unclear risk of selection bias). dDowngraded one level for heterogeneity due to very high I2 value (79%).

Summary of findings 8. Dronedarone compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.

| Dronedarone compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults in sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation Setting: hospital/community Intervention: dronedarone Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no treatment | Risk with dronedarone | |||||

| All‐cause mortality follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 0.86 (0.68 to 1.09) | 6071 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | — | |

| 51 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 (35 to 56) | |||||

| Withdrawals due to adverse effects follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 1.58 (1.34 to 1.85) | 6071 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 77 per 1000 | 122 per 1000 (104 to 143) | |||||

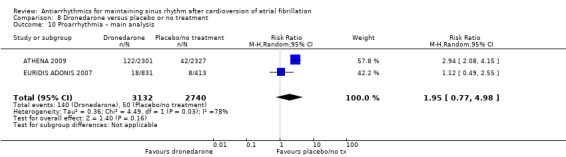

| Proarrhythmia follow‐up: mean 12 months | Study population | RR 1.95 (0.77 to 4.98) | 5872 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | — | |

| 18 per 1000 | 36 per 1000 (14 to 91) | |||||

| Stroke follow‐up: mean 12 months | Study population | RR 0.66 (0.47 to 0.95) | 5872 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | — | |

| 27 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (13 to 25) | |||||

| Recurrence of atrial fibrillation follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 0.85 (0.80 to 0.91) | 1443 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | — | |

| 76.6 per 100 | 65.1 per 100 (61.3 to 69.7) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for study limitations: 83% of weight came from a study with unclear blinding, which could be relevant to this outcome. bDowngraded one level for inconsistency due to very high I2 statistic of 78%. cDowngraded one level for study limitations: most weight came from a study with unclear allocation concealment.

Summary of findings 9. Sotalol compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.

| Sotalol compared to placebo or no treatment for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults in sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation Setting: hospital/community Intervention: sotalol Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no treatment | Risk with sotalol | |||||

| All‐cause mortality follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 2.23 (1.03 to 4.81) | 1882 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | — | |

| 8 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 (9 to 40) | |||||

| Withdrawals due to adverse effects follow‐up: range 6–19 months; median 12 months | Study population | RR 1.95 (1.23 to 3.11) | 2688 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea,b,c | Heterogeneity was high for the main analysis (I2 = 56%), but the test for subgroup differences indicated that the RR was higher in older studies with sotalol. | |

| 94 per 1000 | 183 per 1000 (116 to 293) | |||||

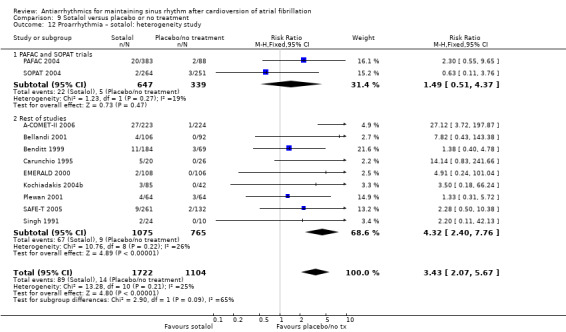

| Proarrhythmia follow‐up: median 12 months | Study population | RR 3.55 (2.16 to 5.83) | 2989 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea,c | — | |

| 12 per 1000 | 41 per 1000 (25 to 68) | |||||

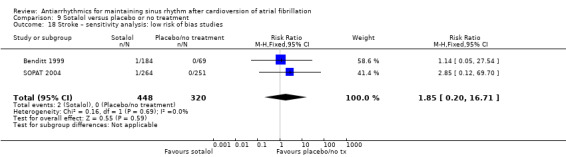

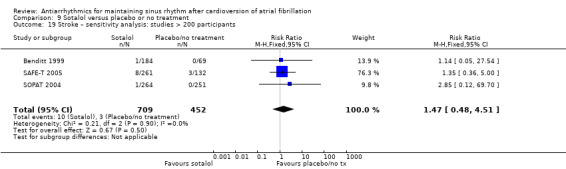

| Stroke follow‐up: range 6–12 months | Study population | RR 1.47 (0.48 to 4.51) | 1161 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderated | — | |

| 7 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (3 to 30) | |||||

| Recurrence of atrial fibrillation follow‐up: range 6–19 months; median 12 months | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.80 to 0.87) | 3179 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,e,f | — | |

| 78.8 per 100 | 65.4 per 100 (63.1 to 68.6) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aNot downgraded for study limitations. Although the majority of studies had unclear or high risk of bias in at least one of the key domains, the majority of the weight was from studies at low risk of bias in key domains. bNot downgraded for inconsistency. I2 statistic was 56% for the main analysis, but this was partially explained by subgroup analysis. cDowngraded one level for publication bias: forest plot appeared to be asymmetrical. dDowngraded one level for imprecision: confidence interval included both possible benefit and harm. eNot downgraded for publication bias: funnel plot appears to be broadly symmetrical. fNot downgraded for inconsistency. I2 statistic was 54% but the forest plot had good overlap in confidence intervals, so a fixed‐effect model was used to maintain the weight of the few larger studies.

We calculated all outcomes at one year of follow‐up or the nearest time point (overall mean follow‐up: 10.2 months).

Imputing missing participants as events (the worst‐case intention‐to‐treat scenario) generally did not modify the results, so we reported the best‐case intention‐to‐treat analysis (missing participants counted as being free of events) as the default; where differences existed, we reported details.

See Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9.

All‐cause mortality

The all‐cause mortality rate was low (0% to 5.1% at one year). The only exception to this generally low mortality rate was the DIAMOND study (DIAMOND 2001). This trial recruited people with advanced heart failure and had an overall all‐cause mortality of 31% at one year.

The quantity and quality of data on mortality varied markedly between drugs. We found no data on mortality with flecainide and very few data with disopyramide and propafenone.

More data were available for other drugs. We found evidence suggesting an increase in the risk of death with two drugs, quinidine and sotalol. For the remaining drugs studied, available evidence show no apparent effect in mortality.

There was no important heterogeneity between studies for all‐cause mortality for any of the drugs studied.

Drugs with very few or no data on mortality

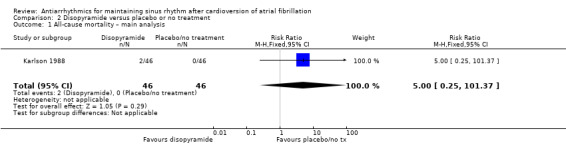

Disopyramide

Only one study reported all‐cause mortality in people receiving disopyramide compared with placebo or no treatment. It included only 92 participants and had a very wide CIs for mortality that included both possible benefits and harms (RR 5.00, 95% CI 0.25 to 101.37; I2 = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disopyramide versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality – main analysis.

Counting missing participants as having died did not change this finding (Analysis 2.2). No other sensitivity analysis could be carried out.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disopyramide versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality – intention to treat (ITT) worse case: missing participants counted as events.

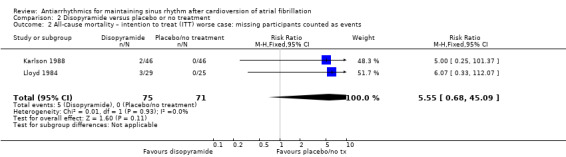

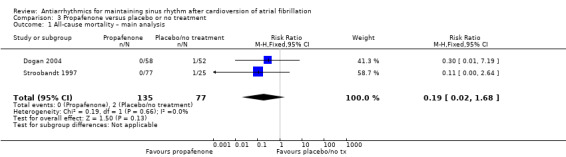

Propafenone

Of the five included trials (998 participants), only two studies reported any deaths (one each). The CIs were wide, including both possible benefits and harms, and the results varied markedly between the main analysis (RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.68; studies = 2, participants = 212; I2 = 0%; Analysis 3.1) and the sensitivity analysis which treated missing participants as having died (RR 1.28, 95% CI 0.45 to 3.62; studies = 3, participants = 406; I2 = 19%; Analysis 3.2). Restricting the analysis to the only study at low risk of bias did not differ from the main analysis (Analysis 3.3).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Propafenone versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality – main analysis.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Propafenone versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality – intention to treat (ITT) worse case: missing participants counted as events.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Propafenone versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis: low risk of bias studies.

Overall, the evidence for this outcome was very low‐certainty, meaning that we were uncertain of the effect of propafenone on mortality.

Flecainide

None of the four trials studying flecainide (511 participants in total) reported any death from any cause.

Drugs associated with an increase in mortality

Quinidine

Six studies that compared quinidine with placebo or no treatment reported all‐cause mortality. The GRADE rating was low‐certainty for this outcome. The pooled RR suggested that risk of mortality was higher in people receiving quinidine compared with placebo or no treatment, although the CIs also included the possibility of a lower or similar mortality rate (RR 2.01, 95% CI 0.84 to 4.77; studies = 6, participants = 1646; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.1). This corresponded to 8 deaths per 1000 people in the control group and 15 (95% CI 6 to 36) per 1000 people in the quinidine group.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Quinidine versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality – main analysis.

Sensitivity analysis which treated missing participants as having died increased the RR slightly, but was not substantially different to the main analysis (RR 2.12, 95% CI 0.96 to 4.67; studies = 6, participants = 1646; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Quinidine versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis intention to treat (ITT) worse case: missing participants counted as events.

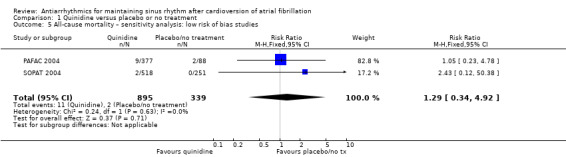

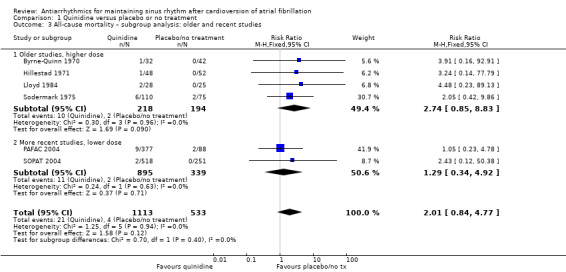

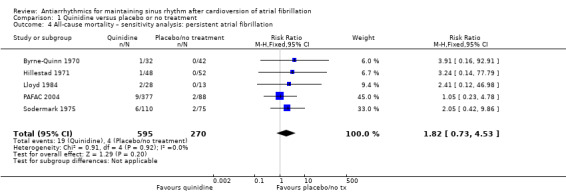

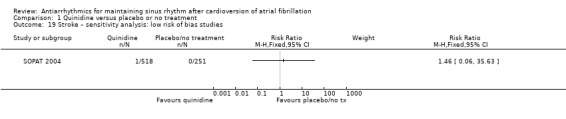

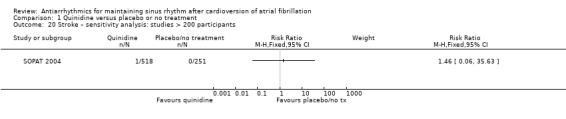

Conversely, sensitivity analysis of quinidine studies at low risk of bias (Analysis 1.5), or studies with more than 200 participants (Analysis 1.6), left only two studies (PAFAC 2004; SOPAT 2004). There was no evidence of a difference in all‐cause mortality compared with controls (RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.34 to 4.92; studies = 2, participants = 1234; I2 = 0%). These two trials were more recent, employed a lower dose of quinidine (320 mg/day to 480 mg/day) than other studies (800 mg/day to 1800 mg/day) and combined quinidine with verapamil. However, when comparing those two studies against older, higher‐dose studies, the test for subgroup differences did not indicate that the effect differed between those two groups (P = 0.4; Analysis 1.3).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Quinidine versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 5 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis: low risk of bias studies.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Quinidine versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 6 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis: studies > 200 participants.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Quinidine versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 All‐cause mortality – subgroup analysis: older and recent studies.

The other sensitivity analysis did not differ from the main analysis (Analysis 1.4: persistent atrial fibrillation).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Quinidine versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis: persistent atrial fibrillation.

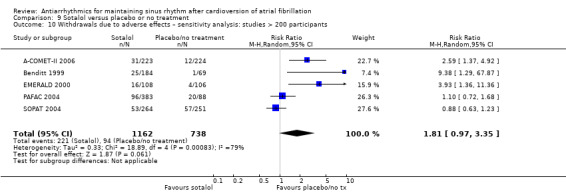

Sotalol

High‐certainty evidence from five RCTs indicated that people receiving sotalol had a higher all‐cause mortality rate than those with placebo or no treatment (RR 2.23, 95% CI 1.03 to 4.81; studies = 5, participants = 1882; I2 = 0%; Analysis 9.1; Figure 5). This corresponded to 8 deaths per 1000 people in the control group and 19 (95% CI 9 to 40) deaths per 1000 people in the sotalol group. The NNTH for sotalol was 102 (95% CI 33 to 4167) participants treated for one year to have one additional death, with a wide CI.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sotalol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality – main analysis.

5.

All‐cause mortality with sotalol compared with placebo/no treatment: main analysis.

This association with increased mortality persisted in all sensitivity analyses undertaken, either counting missing participants as deaths (RR 2.02, 95% CI 1.28 to 3.20; studies = 10, participants = 2757; I2 = 0%; Analysis 9.2), restricting to those studies at low risk of bias (RR 2.51, 95% CI 1.06 to 5.98; studies = 3, participants = 1311; I2 = 0%; Analysis 9.4), or which included only persistent atrial fibrillation (RR 2.51, 95% CI 1.06 to 5.98; studies = 3, participants = 1311; I2 = 0%; Analysis 9.3). There was an even larger effect when restricting the analysis to just those studies with at least 200 participants (RR 2.65, 95% CI 1.16 to 6.09; studies = 4, participants = 1826; I2 = 0%; Analysis 9.5).

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sotalol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality – intention to treat (ITT) worse case: missing participants counted as events.

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sotalol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis: low risk of bias studies.

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sotalol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis: persistent atrial fibrillation.

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sotalol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 5 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis: studies > 200 participants.

Drugs with no apparent effect on mortality

For the remaining drugs studied, available evidence showed no apparent difference in mortality with respect to placebo or no treatment. However, data for mortality were rarely extensive and the data obtained could have been underpowered to detect mild differences in mortality for several of the drugs studied.

Metoprolol

Moderate‐certainty evidence from two studies comparing metoprolol with placebo or no treatment produced very wide CIs (RR 2.02, 95% CI 0.37 to 11.05; studies = 2, participants = 562; I2 = 47%; Analysis 5.1). Results did not change in any of the sensitivity analyses (Analysis 5.2; Analysis 5.3; Analysis 5.4; Analysis 5.5).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Metoprolol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality – main analysis.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Metoprolol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality – intention to treat (ITT) worse case: missing participants counted as events.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Metoprolol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis: persistent atrial fibrillation.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Metoprolol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis: low risk of bias studies.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Metoprolol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 5 All‐cause mortality – sensitivity analysis: studies > 200 participants.

Amiodarone