Abstract

Background and Aims

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has emerged as a safe and effective treatment for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but its role in patients with advanced HCC is not yet defined. In this study, we aim to assess the efficacy and safety of SBRT in comparison to sorafenib treatment in patients with advanced HCC.

Methods

We included 901 patients treated with sorafenib at six tertiary centers in Europe and Asia and 122 patients treated with SBRT from 13 centers in Germany and Switzerland. Medical records were reviewed including laboratory parameters, treatment characteristics and development of adverse events. Propensity score matching was performed to adjust for differences in baseline characteristics. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival.

Results

Median OS of SBRT patients was 18.1 (10.3–25.9) months compared to 8.8 (8.2–9.5) in sorafenib patients. After adjusting for different baseline characteristics, the survival benefit for patients treated with SBRT was still preserved with a median OS of 17.0 (10.8–23.2) months compared to 9.6 (8.6–10.7) months in sorafenib patients. SBRT treatment of intrahepatic lesions in patients with extrahepatic metastases was also associated with improved OS compared to patients treated with sorafenib in the same setting (17.0 vs. 10.0 months, p = 0.012), whereas in patients with portal vein thrombosis there was no survival benefit in patients with SBRT.

Conclusions

In this retrospective comparative study, SBRT showed superior efficacy in HCC patients compared to patients treated with sorafenib.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Sorafenib, Stereotactic body radiation therapy, Propensity score analysis, Overall survival

Introduction

The incidence and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are increasing, and HCC has emerged to be the second most common cause of cancer death worldwide [1, 2]. Although surveillance programs have improved, diagnosis of HCC is still made in advanced stages where treatment options are limited. Of note, during the last years, there have been research efforts leading to the development of immunotherapies targeting programmed cell death protein-1 showing promising efficacy [3]. However, currently, according to the current European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and American Association for the Study of the Liver (AASLD) guidelines, the oral multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib is the only recommended systemic first-line treatment in patients with advanced HCC [4, 5, 6, 7], but meanwhile further targeted therapies such as lenvatinib as a first-line treatment and regorafenib and cabozantinib in second/third-line treatments have demonstrated their efficacy [8, 9]. However, overall survival (OS) in these patients is still poor, and patients treated with sorafenib often show a high incidence of adverse events that worsen quality of life and often lead to dose reduction and even early cessation of sorafenib treatment [10, 11]. Therefore, alternative treatment options for patients with advanced HCC are urgently needed. Selective internal radiotherapy (SIRT) has shown early evidence of efficacy and better safety in HCC patients, therefore suggesting HCC radiosensitivity in a proportion of patients, but two phase 3 trials (SARAH and SIRveNIB) failed to demonstrate an advantage of SIRT compared to sorafenib [12, 13].

During the last years, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has emerged as an effective noninvasive treatment modality [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Although radiation therapy of liver tumors has historically been performed rarely and with mostly a short-term palliative intent due to relative low tolerance of the whole liver to irradiation, extensive research has shown that partial liver volumes can indeed tolerate very high doses [21]. The emergence of SBRT allowed delivering ablative doses while preserving the surrounding liver tissue. Although these reports have shown that SBRT is a feasible and well-tolerated treatment option for patients with HCC, there is no consensus in which clinical setting SBRT should be used in patients with HCC. In order to assess the role of SBRT in comparison to sorafenib treatment, we performed an international multi-center, retrospective analysis by using propensity score matching. We set out to analyze the toxicity profiles and OS in patients with HCC who are not eligible for other treatments such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE).

Materials and Methods

Selection of Patients

The sorafenib cohort consisted of patients from prospectively maintained databases from the University Hospital Freiburg, (Germany, n = 183), the Imperial College London (n = 96), the Academic Liver Unit in Novara (Italy, n = 53), the Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Milan (Italy, n = 263), the Kindai University School of Medicine in Osaka (Japan, n = 192) and the National Cancer Center Hospital in Goyang (South Korea, n = 114). Adult patients (> 18 years) with confirmed HCC eligible for sorafenib treatment were included in the study. In summary, 901 patients treated with sorafenib were included in the analyses.

The SBRT cohort consisted of 122 patients with 122 HCC lesions treated between 2013 and 2017 in the Department of Radiation Oncology of the University Hospital Freiburg (n = 46), the Ludwigs-Maximilians-University Munich (n = 21), the Technical University of Munich, Rechts der Isar (n = 18), the University Hospital Jena (n = 17), the University Hospital Würzburg (n = 9), the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel (n = 3), the University Hospital Halle (n = 3), the University Hospital Zurich (n = 2), the University Hospital Cologne (n = 2) and at the Klinikum Bautzen (n = 1).

Data from these patients were collected retrospectively in a common database report form. SBRT was performed after TACE failure (n = 51), as an alternative to systemic treatment with sorafenib (n = 50) or after progression under sorafenib (n = 21).

Definitions

HCC was diagnosed according to current guidelines by histopathology or computed tomography scan or dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showing the typical hallmark of HCC imaging (hypervascularity in the arterial phase with washout in the portal venous or delayed phases) [5, 22, 23]. The number of focal hepatic lesions, the maximum tumor diameter and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) and its extent were detected during contrast enhancement. The numbers of intrahepatic lesions are summarized in oligonodular (one or two intrahepatic lesions) and in multifocal HCC (three or more lesions or diffuse HCC growth pattern). HCC was staged according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification. Liver function was assessed using the Child-Pugh score.

SBRT Techniques

The analysis was performed on a multi-center SBRT database that was organized by the Working Group on Stereotactic Radiotherapy of the German Society of Radiation Oncology (DEGRO) on primary liver cancer. This database was designed as an SBRT patterns-of-care database within the DEGRO initiative and headed by the DEGRO Working Group on Stereotactic Radiotherapy. A detailed description of patient, tumor and treatment characteristics was collected retrospectively and collated in a tabular data structure. Most patients with advanced tumors were either ineligible or progressed after TACE or other treatments. Patients with BCLC stage C that progressed under sorafenib had no other treatment options. For patients (BCLC stage B) that progressed after TACE, SBRT was offered as a local ablative option, as an alternative to systemic therapy with sorafenib, which has a high toxicity profile. Furthermore, for patients with oligometastatic disease (BCLC stage C) there is emerging evidence that TACE, a local ablative treatment, significantly improves OS [24]. Taking these data into consideration, patients that progressed under TACE were also offered SBRT by the multidisciplinary tumor panel, as an alternative to systemic treatment.

The median number of fractions was 7 (range 3–12). Dose was prescribed most frequently to the 80% isodose (median) with an inhomogeneous dose profile as typical for SBRT treatments. Prescribed dose was available for all lesions. Planning target volumes (PTV) were chosen as surrogate tumor volumes which were available in all cases. The PTV was defined according to the institutional standards typically including the PVT when possible. Furthermore, in order to equate or compare the different fraction schedules, we converted the dose to biological effective dose (BED) [25]. In cases of multinodular disease, SBRT was performed either simultaneously or sequentially depending of the size of the PTV and the dose 700 cm3 of the uninvolved liver and the Child Pugh score, according to Pan et al. [26]. Motion management was categorized into simple (free breathing, abdominal compression) versus advanced (breath-hold, gating, tracking). For lesions where dose constraints for the OARs according to Timmermann [27] could not be achieved due to small overlaps with the PTV, a more moderate fractionation as well as a simultaneous integrated protection dose prescription was employed instead of reducing the dose to the entire PTV as described elsewhere [28]. In cases where the dose constraints for the liver which depended on the size of the lesion or the Child Pugh score or for the other organs at risk could not be achieved, these patients were considered ineligible for SBRT.

Importantly, some patients with extrahepatic disease received SBRT of the extrahepatic lesions (adrenal metastases [n = 1] or palliative radiotherapy of the bone metastases [n = 5]). Moreover, 33 patients who progressed after SBRT received further HCC treatment consisting of sorafenib in 20 patients (16.4%), TACE in 11 patients (9.0%) and TACE and sorafenib in 2 patients (1.6%).

Sorafenib Treatment and Toxicity

Sorafenib treatment was initiated after multidisciplinary discussion as the first tumor therapy or in patients who had relapse, failure or ineligibility to surgical or locoregional treatments. After initiation of sorafenib therapy, patients were followed-up after 4 weeks and thereafter every 3 months. During follow-up, safety and tolerability were reviewed. The cause for cessation of sorafenib treatment due to progressive disease, death, toxicity or patient preference was recorded. The occurrence of adverse events was recorded and graded according to the Common Toxicity Criteria Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 4.0). Treatment-associated toxicity was defined as occurrence of adverse events after the beginning of SBRT or sorafenib treatment.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and it has been approved by the local ethics committee of the University Hospital of Freiburg (No. EK 595/17).

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics of the patients were analyzed before sorafenib treatment or SBRT, respectively. The primary outcome in our analysis was OS and treatment-associated toxicity was defined as the secondary endpoint. Continuous variables are expressed as mean with standard deviation, whereas categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages unless stated otherwise. For continuous variables, differences were determined using Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests as there was no Gaussian distribution of the data confirmed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. χ2 tests or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables. p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

OS was defined from the day of initiation of sorafenib or SBRT treatment until death or last follow-up. At the end of the observation period (01/09/2017), 814 patients (78.6%) in the whole cohort and 128 patients (67.4%) in the matched cohort had died. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined from the day of starting sorafenib or SBRT treatment until death or radiological progression. Data concerning PFS were available in 786 of 1,023 patients (76.8%) (sorafenib group: 680 of 901 patients [75.5%], SBRT group: 106 of 122 patients [86.9%]). OS and PFS were calculated using Kaplan-Meier analyses, and they are reported as median OS or PFS with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Differences in OS were assessed using log rank tests and uni- and multivariable Cox regression models (forward selection method with likelihood ratio). Propensity score matching was performed to reduce selection bias for the allocation to sorafenib or SBRT. Multivariable logistic regression model was performed to generate the propensity score. The following factors were included in this model: Child-Pugh score, prior surgery, radiofrequency ablation, TACE, hepatic tumor burden, PVT, extrahepatic metastases, and ECOG performance status (PS) (ECOG PS 0 vs. 1 vs. 2). After establishing the propensity score, 1: 1 matching using the nearest-neighbor matching was performed with a caliper of 0.01 without replacement. Post hoc balance diagnostic was performed using mean standardized differences [29].

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 24.0, IBM, New York, NY, USA) GraphPad Prism (version 6, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and STATA (version 15, StataCorp Lp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient and Treatment Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the patient cohorts treated with sorafenib and SBRT. In the unmatched cohort, significantly more patients treated with sorafenib presented with multifocal HCC compared to SBRT patients (76.6 vs. 46.7%, p < 0.001). PVT was also more frequently observed in patients treated with sorafenib (34.0 vs. 18.0%, p < 0.001). A total of 35.7% of the sorafenib patients had extrahepatic metastases compared to 13.1% of SBRT patients (p < 0.001). In summary, sorafenib patients presented with more advanced tumor disease compared to SBRT patients, which is also underlined by higher BCLC stages in sorafenib-treated patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study patients and lesions treate

| Characteristics | Sorafenib (n = 901) | SBRT (n = 122) | p value | Mean standardized difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.627 | 0.049 | ||

| Male | 729 (80.9) | 101 (82.8) | ||

| Female | 172 (19.1) | 21 (17.2) | ||

| Age, years | 66.7±11.7 | 67.2±8.5 | 0.988 | 0.050 |

| ECOG | ||||

| 0 | 595 (66.0) | 75 (61.5) | 0.361 | 0.094 |

| 1 | 186 (20.6) | 46 (37.7) | <0.001 | 0.383 |

| 2 | 120 (13.3) | 1 (0.8) | <0.001 | 0.504 |

| Child score | 6.1±1.1 | 5.9±1.2 | 0.027 | 0.166 |

| Child A | 544 (60.4) | 79 (64.8) | 0.375 | 0.091 |

| Child B | 354 (39.3) | 37 (30.3) | 0.060 | 0.199 |

| Child C | 3 (0.3) | 6 (4.9) | <0.001 | 0.292 |

| Previous treatmenta | ||||

| Surgery | 163 (18.1) | 21 (17.2) | 0.900 | 0.024 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 184 (20.4) | 6 (4.9) | <0.001 | 0.480 |

| TACE | 485 (53.8) | 51 (41.8) | 0.016 | 0.242 |

| Intrahepatic tumor expansion | n = 719 | <0.001 | 0.646 | |

| Oligonodular | 168 (23.4) | 65 (53.3) | ||

| Multifocal | 551 (76.6) | 57 (46.7) | ||

| BCLC | ||||

| A | 41 (4.6) | 6 (4.9) | 0.999 | 0.014 |

| B | 242 (26.9) | 69 (56.6) | <0.001 | 0.632 |

| C | 618 (68.6) | 47 (38.5) | <0.001 | 0.633 |

| Largest tumor diameter, cm | 5.9±4.1 | 5.6±3.4 | 0.836 | 0.080 |

| PVT | 306 (34.0) | 22 (18.0) | <0.001 | 0.371 |

| Extrahepatic metastases | 322 (35.7) | 16 (13.1) | <0.001 | 0.545 |

| Laboratory | ||||

| AST, U/L | 87±80 | 94±67 | 0.358 | 0.094 |

| ALT, U/L | 61±58 | 57±42 | 0.813 | 0.089 |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.1±0.8 | 1.2±2.2 | 0.257 | 0.036 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.7±0.5 | 3.5±0.7 | 0.045 | 0.329 |

| AFP, ng/mL | 12,959.5±61,182.5 | 2,174.9±9,637.4 | 0.001 | 0.246 |

| Treatment characteristics of SBRT patients | ||||

| TD, Gy | 44 (21–66) | |||

| BED10,TD, Gy | 84.4 (36–180) | |||

| Dmax, Gy | 58 (26–72) | |||

| BED10,max, Gy | 119 (40–272) | |||

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± SD or median (range). ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; PVT, portal vein thrombosis; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy; TD, total prescribed dose; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; BED10,TD, biological equivalent dose of the prescribed dose; Dmax, maximum point dose; BED10max, biological equivalent dose of the maximum point dose.

Patients may have received more than one treatment.

In the sorafenib group, the mean treatment duration was 5.7 ± 6.7 months. In 522 patients (57.9%), sorafenib was applied with the recommended dose of 800 mg per day, and in 379 patients (42.1%) a reduced dose was given.

In patients with SBRT, the median prescribed SBRT dose was 44 (range: 21–66) Gy in 3–12 fractions with a median maximum dose (Dmax) of 58 (range: 26–72) Gy. The median BED (BED10) prescribed was 84.4 (range: 36–124) Gy.

Toxicity

Adverse Events in the Sorafenib Cohort

Overall, 73.6% (663/901) of sorafenib-treated patients experienced at least one sorafenib-associated adverse event at any grade (Table 2). A total of 39.3% developed diarrhea, 31.2% showed hand-foot skin reaction, 29.3% developed fatigue, 19.0% had significant weight loss, 13.3% developed sorafenib-related hypertension. Mucositis occurred in 4.7%, and 7.5% of the sorafenib-treated patients reported nausea and vomiting. Sorafenib was stopped in 175 patients (19.4%) due to adverse events. Data concerning dose reduction were available in 888 patients (98.6%), and of these 277 patients had dose reduction due to clinically significant adverse events (31.2%). In addition, sorafenib was stopped due to progressive HCC (53.8%), death (45.2%), patient preference (2.8%), and other reasons (6.2%). At the end of the observation period, 23 patients (2.6%) still received sorafenib.

Table 2.

Incidence of treatment-associated adverse events in the unmatched cohort

| Any grade | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse events in patients treated with sorafenib | |||||

| Hand-foot skin reaction | 281 (31.2) | 102 (36.3)a | 104 (37.0) | 73 (26.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Diarrhea | 354 (39.3) | 143 (40.4) | 102 (28.8) | 99 (27.9) | 10 (2.9) |

| Obstipation | 16 (1.8) | 11 (68.8) | 5 (31.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 264 (29.3) | 104 (39.4) | 96 (36.4) | 59 (22.3) | 5 (1.9) |

| Weight loss | 171 (19.0) | 98 (57.3) | 54 (31.6) | 14 (8.2) | 5 (2.9) |

| Hypertension | 120 (13.3) | 53 (44.2) | 50 (41.7) | 17 (14.2) | 0 |

| Mucositis | 42 (4.7) | 18 (42.9) | 18 (42.9) | 6 (14.3) | 0 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 68 (7.5) | 37 (54.4) | 26 (38.2) | 5 (7.4) | 0 |

| Adverse events in patients treated with SBRT | |||||

| Fatigue | 1 (1.0) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Increase in aminotransferases | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Increase in bilirubin | 9 (7.4) | 0 | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | 0 |

| Increase in alkaline phosphatase | 2 (1.6) | 0 | 2 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Increase in γ-glutamyl transferase | 3 (2.5) | 0 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 |

| Duodenitis/gastrointestinal bleeding | 3 (2.5) | 0 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 |

| Liver-associated toxicity | |||||

| Liver abscess | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Radiation-induced liver disease | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100)b | 0 |

| Hepatic decompensation | 3 (2.5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (66.7)b | 1 (33.3) |

| Cholangitis | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 |

Relative frequencies refer to any grade of the reported adverse event.

One of the patients with hepatic decompensation developed radiation-induced liver disease

Adverse Events in the SBRT Cohort

Three SBRT patients with known portal hypertension developed gastric ulcers with bleeding, 3, 4 and 5 months after SBRT and were treated with proton pump inhibitors (2 patients, CTCAE grade 2) and transfusion (1 patient, grade CTCAE 3). The patient with CTCAE grade 3 gastroduodenitis who required a transfusion was treated in the past with liver SBRT for another HCC lesion, with an interval of 4 months between the two treatments. In all other cases, the constraints did not exceed the constraints proposed by Timmerman [27]. An increase in the Child-Pugh score without progression was observed in 4 patients (B7–B8, A6–B7, B8–C9, A5–A6), and 1 patient developed an increase of ≥2 points after treatment (A6–B8) due to a radiation-induced liver disease. This patient recovered fully from radiation-induced liver disease, but died 9 months after SBRT due to renal failure. One of these patients, with an increase of 1 point (A5–A6) died due to liver decompensation without tumor progression 4 months after SBRT, and 1 patient developed a liver decompensation and was transplanted without evidence of tumor disease (pathological complete response). One patient developed a necrotic abscess in the PTV of the liver due to a dislocation of a preexisting stent of the bile duct, and 1 patient developed a cholangitis probably deemed to be SBRT-related by the investigators. We did not observe any higher incidence of toxicities with higher doses, as different dose-fractionation schedules (Table 1) were used in order to respect the dose constraints for the organs at risk.

OS and PFS in Patients Treated with SBRT Compared to Sorafenib in the Unmatched and Matched Cohort

In patients treated with sorafenib, OS was 8.8 (8.2–9.5) months compared to 17.0 (9.8–24.2) months in the SBRT cohort. PFS was 4.0 (3.5–4.5) months in sorafenib-treated patients compared to 9.0 (5.2–12.7) months in SBRT patients (p < 0.001). We performed multivariable logistic regression model for development of the propensity score (online suppl. Table 1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000490260). After 1: 1 matching using the nearest-neighbor method, we identified 190 patients (95 sorafenib patients and 95 SBRT patients) with comparable patient and tumor characteristics (Table 3). Covariates which were used for development of the propensity score showed mean standardized differences ≤0.01 indicating adequate balance of the matched variables.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients after propensity score matching

| Characteristics | Sorafenib (n = 95) | SBRT (n = 95) | p value | Mean standardized difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 78 (82.1) | 79 (83.2) | 0.999 | 0.029 |

| Female | 17 (17.9) | 16 (16.8) | ||

| Age, years | 66.9±12.5 | 66.7±8.9 | 0.472 | 0.018 |

| ECOG | ||||

| 0 | 63 (66.3) | 71 (74.7) | 0.265 | 0.018 |

| 1 | 31 (32.6) | 23 (24.2) | 0.260 | 0.187 |

| 2 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0.999 | 0 |

| Child score | 5.8±0.9 | 5.9±1.2 | 0.629 | 0.094 |

| Child A | 70 (73.7) | 67 (71.3) | 0.426 | 0.054 |

| Child B | 25 (26.3) | 28 (29.5) | 0.999 | 0.071 |

| Previous treatmenta | ||||

| Surgery | 18 (18.9) | 16 (16.8) | 0.850 | 0.054 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 4 (4.2) | 5 (5.3) | 0.999 | 0.052 |

| TACE | 47 (49.5) | 48 (50.5) | 0.999 | 0.020 |

| Intrahepatic tumor expansion Oligonodular | 39 (41.1) | 40 (42.1) | 0.999 | 0.020 |

| Multifocal | 56 (58.9) | 55 (57.9) | ||

| BCLC | ||||

| A | 5 (5.3) | 4 (4.2) | 0.999 | 0.051 |

| B | 42 (44.2) | 48 (50.5) | 0.468 | 0.116 |

| C | 48 (50.5) | 43 (45.3) | 0.561 | 0.104 |

| Largest tumor diameter, cm | 6.5±4.1 | 6.2±3.6 | 0.495 | 0.008 |

| PVT | 20 (21.1) | 21 (22.1) | 0.999 | 0.024 |

| Extrahepatic metastases | 24 (25.3) | 16 (16.8) | 0.213 | 0.102 |

| Laboratory | ||||

| AST, U/L | 100±128 | 93±70 | 0.385 | 0.066 |

| ALT, U/L | 65±81 | 58±44 | 0.810 | 0.107 |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.1±0.7 | 1.7±1.4 | 0.023 | 0.041 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.6±0.5 | 3.5±0.5 | 0.321 | 0.021 |

| AFP, ng/mL | 16,100±69,008.7 | 22,611±10,016.1 | 0.016 | 0.322 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± SD. ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; PVT, portal vein thrombosis; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein.

Patients may have received more than one treatment.

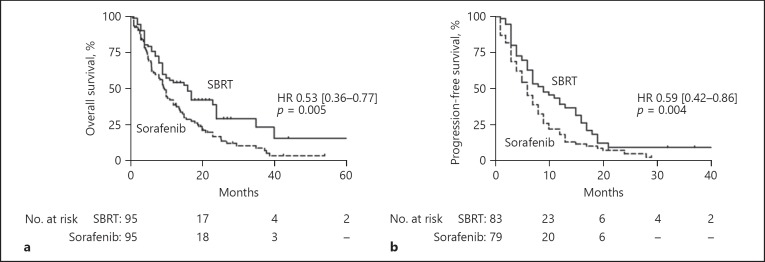

In the matched cohort, patients treated with SBRT still had improved OS of 16.0 (11.0–21.0) months compared to 9.6 (8.6–10.7) months in the sorafenib group (p = 0.005, Fig. 1a). After matching, PFS was 6.0 (4.8–7.2) months in patients with sorafenib compared to 9.0 (5.8–12.2) months in SBRT patients (p = 0.004, Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Patients treated with SBRT had significantly improved overall survival compared to patients treated with sorafenib in the matched cohort (9.6 vs. 16.0 months). b Further, patients treated with SBRT also had an improved progression-free survival compared to sorafenib patients (9.0 vs. 6.0 months).

Thirty-three patients (27.0%) who were treated with SBRT showed progression during the study period and received further treatment (sorafenib: n = 20, TACE: n = 11, TACE and sorafenib: n = 2) which may have affected OS. In order to adjust for this confounder, we excluded these patients and were able to reproduce the survival benefit of SBRT treated patients (online suppl. Fig. 1).

Further, we performed uni- and multivariate Cox regression analyses and confirmed SBRT as an independent positive prognostic factor for OS (Table 4; HR 0.53 [0.36–0.77], p = 0.001). In patients treated with SBRT, a higher median BED (biological equivalent dose: BED10,TD) did not affect OS (p = 0.674, online suppl. Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression model in the matched cohort of patients

| Variable | Univariable Cox regression |

Multivariable Cox regression |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.085 | |||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 1.15 | 0.74–1.80 | 0.530 | |||

| Child score | 1.23 | 1.05–1.45 | 0.012 | 1.39 | 1.16–1.66 | <0.001 |

| Previous treatment | ||||||

| Surgery | 0.99 | 0.65–1.54 | 0.995 | |||

| Radiofrequency ablation | 0.80 | 0.33–1.96 | 0.627 | |||

| TACE | 1.26 | 0.89–1.79 | 0.193 | |||

| Intrahepatic tumor expansion (olignodular vs. multifocal) | 1.51 | 1.05–2.16 | 0.025 | |||

| BCLC | ||||||

| A | 1 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.001 | ||

| B | 1.82 | 0.66–5.06 | 0.245 | 1.58 | 0.55–4.48 | 0.390 |

| C | 3.40 | 1.23–9.41 | 0.019 | 3.21 | 1.12–9.22 | 0.030 |

| Largest tumor diameter | 1.09 | 1.05–1.14 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.02–1.12 | 0.006 |

| PVT | 1.77 | 1.18–2.65 | 0.006 | |||

| Extrahepatic metastases | 1.26 | 0.84–1.90 | 0.264 | |||

| Treatment (sorafenib vs. SBRT) | 0.57 | 0.40–0.81 | 0.002 | 0.53 | 0.36–0.77 | 0.001 |

HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; PVT, portal vein thrombosis, SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy.

OS in Patients with Extrahepatic Metastases and PVT in Patients Treated with Sorafenib or SBRT

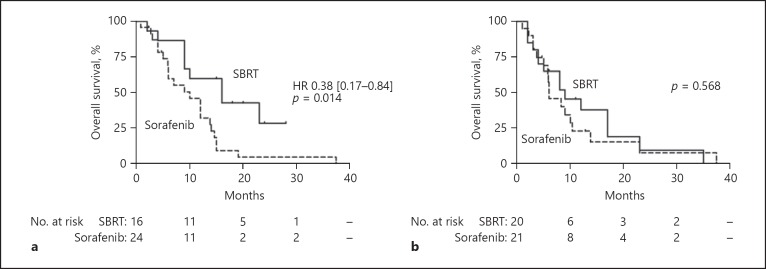

We further performed subgroup analyses in patients with PVT (n = 328) and extrahepatic metastases (n = 338). In the unmatched cohort, patients with extrahepatic metastases treated with SBRT (only SBRT of the hepatic tumor) showed a significantly improved OS compared to patients with sorafenib treatment (16.0 [6.7–25.4] vs. 7.6 [6.2–8.9] months, HR 0.43 [0.22–0.84], p = 0.014). Also, in the matched cohort, the survival benefit of SBRT treatment in metastatic patients (n = 40) was consistent (16.0 [6.6–25.4] vs. 10.0 [5.5–14.5] months, HR 0.38 [0.17–0.84], p = 0.018, Fig. 2a). Importantly, some patients with extrahepatic disease received SBRT of these extrahepatic lesions (adrenal metastases [n = 1] and palliative radiotherapy of the bone metastases [n = 5]). These patients were not included in the matched cohort due to the lack of an adequate matching partner.

Fig. 2.

a Patients with extrahepatic metastases treated with SBRT had improved overall survival compared to sorafenib treatment. b In patients with PVT, SBRT was not associated with longer overall survival compared to sorafenib treatment.

Patients with PVT treated with SBRT had a median OS of 8.0 (4.3–11.7) compared to 6.1 (5.2–6.9) months in sorafenib-treated patients in the unmatched cohort (p = 0.330). After propensity score matching, there was no difference concerning OS between patients with SBRT or sorafenib treatment (9.0 [2.9–15.1] vs. 6.0 [2.7–9.3] months, p = 0.568, Fig. 2b).

Discussion

HCC is often diagnosed in intermediate or advanced tumor stages [5, 30]. Especially in advanced tumor stages, treatment options are limited, and there is no consensus concerning the best treatment option according to the current NCCN guidelines [31]. However, sorafenib is recommended in these patients according to the current EASL, AASLD and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines [6, 32, 33]. Sorafenib is associated with many adverse events as shown in our study which may lead to a significant deterioration of quality of life. Moreover, the development of adverse events during sorafenib treatment is associated with application of a reduced dose of sorafenib [11, 34, 35]. In our study, only 57.9% of the patients were treated with the recommended dose of 800 mg per day, and 31.2% of the patients had dose reduction. Taken together, there is a need for a well-tolerable treatment strategy in patients with advanced HCC. During the last years, there have been many research efforts leading to immunotherapies targeting programmed cell death protein-1 with nivolumab, and these treatment approaches showed promising results in HCC patients with few adverse events [36, 37]. The efficacy of these therapies in direct comparison to sorafenib is still under investigation and is not yet clarified (NCT 02576509). However, the main limitation of these immunotherapeutic approaches is that only 20% of the patients showed an objective tumor response, and to date there are no biomarkers available to select those patients who will benefit most from immunotherapies.

SBRT has emerged as an effective and safe treatment approach, even in patients with advanced liver disease with acceptable toxicity [14, 17, 18, 20, 38, 39] without compromising quality of life [40, 41]. Recently, it has been suggested that SBRT is as effective as radiofrequency ablation [42] and TACE [43] in selected patients. Moreover, SBRT has shown good efficacy in local control of HCC lesions as a bridging therapy to liver transplantation [44, 45, 46, 47]. However, there have been no studies focusing on the efficacy of SBRT in comparison to sorafenib in advanced HCC, and the combination of both was correlated with a higher incidence of adverse events [48]. In order to answer this important clinical question, we analyzed an international, multicenter HCC database with patients treated with sorafenib and a German/Swiss cohort of SBRT patients. In our unmatched cohort, patients treated with sorafenib presented with more advanced tumor disease as shown by a higher prevalence of PVT, extrahepatic metastases, and also more extensive hepatic disease. Moreover, significantly more patients were classified as BCLC A in the sorafenib group, although in this BCLC stage, sorafenib is not recommended by the current HCC guidelines. These observations are in line with the GIDEON study showing that, especially in Asia, patients were significantly more often treated with sorafenib in BCLC A stages [35]. These patients also had multiple prior HCC treatment including several TACE sessions. Indeed, after several embolization procedures, further transarterial approaches may be limited due to impaired vascular architecture so that sorafenib is also used in this setting although the patient is formally classified as having an earlier BCLC stage [49].

As patients allocated to sorafenib treatment versus to SBRT show different baseline tumor and patient characteristics which may directly affect OS and PFS and therefore lead to a significant bias, we performed a propensity score matching to adjust for these confounders. The significant survival benefit of patients treated with SBRT compared to sorafenib patients in the unmatched cohort was also reproducible after propensity score matching.

Importantly, patients with advanced tumor disease are very heterogeneous as they may show PVT and/or extrahepatic metastases, and it needs to be clarified if both patient groups show the same survival benefit when treated with SBRT compared to sorafenib. Patients with extrahepatic metastases who were treated with SBRT of the intrahepatic HCC nodules (excluding radiation therapy of the extrahepatic metastases as these patients were not included in the matched analyses) showed significantly improved OS compared to patients who were treated systemically with sorafenib alone. This finding is in line with our previous results showing that intrahepatic tumor control with TACE is associated with improved OS compared to sorafenib treatment [24, 50]. Moreover, rare events such as abscopal effects on metastases after local tumor therapy have been described in other tumor entities and also in cases of HCC as the SBRT can modulate antitumor immune responses [51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59]. As we did not focus on the changes of extrahepatic metastases in our study, we cannot answer this question. However, in summary, our results may provide the rationale for treating intrahepatic HCC with SBRT also in patients with extrahepatic metastases.

In comparison to patients with extrahepatic metastases, we were not able to confirm a survival benefit in patients with PVT treated with SBRT compared to sorafenib treatment. We only observed a trend to a better OS which may be due to the reduced sample size after propensity score matching. In this setting, selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) has shown good efficacy in several studies [60, 61]. However, in the recently published SARAH trial, sorafenib tended to be superior to SIRT in patients with PVT. However, considering all patients, SIRT was not able to show superior OS compared to sorafenib [12]. Taken together, due to the controversial results, further studies have to evaluate the efficacy of SBRT in comparison to sorafenib and SIRT in well-powered prospective and randomized trials.

We have to acknowledge limitations of our study. It was a retrospective, observational study and therefore treatment allocation was not controlled and may be biased due to different factors such as the intrahepatic tumor burden, liver function, and especially the PS of the patient. Especially the PS of the patients and the toxicities are difficult to assess retrospectively. Furthermore, it is difficult to overcome the institutional differences of the treatment decision policies in patients with advanced or recurrent HCCs after prior treatments. In order to equate or compare the different fraction schedules, we converted the dose to BED, which was similar to the published literature (ranging between 33.6 and 103 Gy in the study of Bujold et al. [62]) which did not correlate with OS (data not shown).

Further, we tried to adjust for these differences by propensity score matching. As we applied strict matching criteria with a caliper of 0.01, our sample size in the matched cohort was significantly reduced compared to the unmatched cohort. The small sample size may especially limit the conclusions, which can be drawn from our subgroup analyses. We were not able to do analyses concerning PFS in the subgroups (PVT, extrahepatic metastases) as numbers were too small to draw adequate conclusion.

Importantly, it is difficult to compare the prognosis in patients with advanced HCCs, as HCCs are very heterogeneous even in the same stage. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing a survival benefit of patients treated with SBRT compared to sorafenib in patients with HCC. Therefore, these analyses may be the rationale for designing randomized-controlled trials to further evaluate this treatment approach.

Disclosure Statement

D.B.: consulting Bayer Healthcare. L.R.: consulting Bayer Healthcare and Sirtex Medical.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: D.B., T.B.B., E.G. Acquisition of data: D.B., D.J.P., L.R., T.P., M.E.B, M.P., M.K., J.W.P., D.H., O.R., M.G., J.T., N.A-.S., S.G., W.B., H.A., C.O., O.B. Interpretation of data: D.B., M.S., N.B., T.B.B., E.G. Statistical analyses: D.B, E.G. Drafting the manuscript: D.B., T.B.B., E.G. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: M.S., D.J..P, L.R., T.P., M.E.B., M.P., M.K., J.W.P., N.B., C.N.-H., T.B., D.H., O.R., M.G., O.B., J.T., N.A.-S., S.G., W.B., H.A., C.O., A.-L.G., R.T.

All authors approved the final version of the article, including the authorship.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

D.B. is supported by the Berta-Ottenstein-Programme, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg.

References

- 1.Wallace MC, Preen D, Jeffrey GP, Adams LA. The evolving epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global perspective. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:765–779. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1028363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruix J, Gores GJ, Mazzaferro V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical frontiers and perspectives. Gut. 2014;63:844–855. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase ½ dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc J-F, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llovet JM, Ducreux M, Lencioni R, Di Bisceglie AM, Galle PR, Dufour JF, et al. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogasawara S, Chiba T, Ooka Y, Kanogawa N, Motoyama T, Suzuki E, et al. Efficacy of sorafenib in intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients refractory to transarterial chemoembolization. Oncology. 2014;87:330–341. doi: 10.1159/000365993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang Y-H, Bodoky G, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng AL, Finn RS., QS A phase III trial of lenvatinib (LEN) vs sorafenib (SOR) in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (REFLECT study) (abstract) J Clin Oncol. 2017;35((suppl)):4001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogasawara S, Chiba T, Ooka Y, Kanogawa N, Motoyama T, Suzuki E, et al. Efficacy of sorafenib in intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients refractory to transarterial chemoembolization. Oncology. 2014;87:330–341. doi: 10.1159/000365993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howell J, Pinato DJ, Ramaswami R, Bettinger D, Arizumi T, Ferrari C, et al. On-target sorafenib toxicity predicts improved survival in hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-centre, prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1146–1155. doi: 10.1111/apt.13977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vilgrain V, Pereira H, Assenat E, Guiu B, Ilonca AD, Pageaux GP, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective internal radiotherapy with yttrium-90 resin microspheres compared with sorafenib in locally advanced and inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma (SARAH): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1624–1636. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandhi M, Choo SP, Thng CH, Tan SB, Low ASC, Cheow PC, et al. Single administration of Selective Internal Radiation Therapy versus continuous treatment with sorafeNIB in locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (SIRveNIB): study protocol for a phase III randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:856. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2868-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gkika E, Schultheiss M, Bettinger D, Maruschke L, Neeff HP, Schulenburg M, et al. Excellent local control and tolerance profile after stereotactic body radiotherapy of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiat Oncol. 2017;12:116. doi: 10.1186/s13014-017-0851-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendez Romero A, de Man RA. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for primary and metastatic liver tumors: from technological evolution to improved patient care. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;30:603–616. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tse RV, Hawkins M, Lockwood G, Kim JJ, Cummings B, Knox J, et al. Phase I study of individualized stereotactic body radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:657–664. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterzing F, Brunner TB, Ernst I, Baus WW, Greve B, Herfarth K, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for liver tumors: principles and practical guidelines of the DEGRO Working Group on Stereotactic Radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2014;190:872–881. doi: 10.1007/s00066-014-0714-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bujold A, Massey CA, Kim JJ, Brierley J, Cho C, Wong RKS, et al. Sequential phase I and II trials of stereotactic body radiotherapy for locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1631–1639. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiu H, Moravan MJ, Milano MT, Usuki KY, Katz AW. SBRT for hepatocellular carcinoma: 8-year experience from a regional transplant center. J Gastrointest Cancer. doi: 10.1007/s12029-017-9990-1. DOI: 10.1007/s12029-017-9990-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray LJ, Dawson LA. Advances in stereotactic body radiation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2017;27:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrence TS, Ten Haken RK, Kessler ML, Robertson JM, Lyman JT, Lavigne ML, et al. The use of 3-D dose volume analysis to predict radiation hepatitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:781–788. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90651-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bettinger D, Spode R, Glaser N, Buettner N, Boettler T, Neumann-Haefelin C, et al. Survival benefit of transarterial chemoembolization in patients with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma: a single center experience. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:98. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0656-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fowler JF. 21 years of biologically effective dose. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:554–568. doi: 10.1259/bjr/31372149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan CC, Kavanagh BD, Dawson LA, Li XA, Das SK, Miften M, et al. Radiation-associated liver injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timmerman RD. An overview of hypofractionation and introduction to this issue of seminars in radiation oncology. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2008;18:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunner TB, Nestle U, Adebahr S, Gkika E, Wiehle R, Baltas D, et al. Simultaneous integrated protection. Strahlentherapie Onkol. 2016;192:886–894. doi: 10.1007/s00066-016-1057-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:221–239. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;119:751–752. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benson AB, 3rd, D'Angelica MI, Abbott DE, Abrams TA, Alberts SR, Saenz DA, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Hepatobiliary Cancers, Version 1.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:563–573. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verslype C, Rosmorduc O, Rougier P. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO-ESDO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23((suppl 7)):vii41–vii48. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruix J, Sherman M. Practice Guidelines Committee, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–1236. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunocilla PR, Brunello F, Carucci P, Gaia S, Rolle E, Cantamessa A, et al. Sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma: prospective study on adverse events, quality of life, and related feasibility under daily conditions. Med Oncol. 2013;30:345. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kudo M, Lencioni R, Marrero JA, Venook AP, Bronowicki JP, Chen XP, et al. Regional differences in sorafenib-treated patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: GIDEON observational study. Liver Int. 2016;36:1196–1205. doi: 10.1111/liv.13096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase ½ dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng D, Hui X, Shi-Chun L, Yan-Hua B, Li C, Xiao-Hui L, et al. Initial experience of anti-PD1 therapy with nivolumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:96649–96655. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culleton S, Jiang H, Haddad CR, Kim J, Brierley J, Brade A, et al. Outcomes following definitive stereotactic body radiotherapy for patients with Child-Pugh B or C hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2014;111:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Connor JK, Trotter J, Davis GL, Dempster J, Klintmalm GB, Goldstein RM. Long-term outcomes of stereotactic body radiation therapy in the treatment of hepatocellular cancer as a bridge to transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2012;18:949–954. doi: 10.1002/lt.23439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendez Romero A, Wunderink W, van Os RM, Nowak PJCM, Heijmen BJM, Nuyttens JJ, et al. Quality of life after stereotactic body radiation therapy for primary and metastatic liver tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1447–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klein J, Dawson LA, Jiang H, Kim J, Dinniwell R, Brierley J, et al. Prospective longitudinal assessment of quality of life for liver cancer patients treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wahl DR, Stenmark MH, Tao Y, Pollom EL, Caoili EM, Lawrence TS, et al. Outcomes after stereotactic body radiotherapy or radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:452–459. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.4925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sapir E, Tao Y, Schipper MJ, Bazzi L, Novelli PM, Devlin P, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy as an alternative to transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sapisochin G, Barry A, Doherty M, Fischer S, Goldaracena N, Rosales R, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy versus TACE or RFA as a bridge to transplant in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. An intention-to-treat analysis. J Hepatol. 2017;67:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katz AW, Chawla S, Qu Z, Kashyap R, Milano MT, Hezel AF. Stereotactic hypofractionated radiation therapy as a bridge to transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical outcome and pathologic correlation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:895–900. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandroussi C, Dawson L, Lee M, Guindi M, Fischer S, Ghanekar A, et al. Radiotherapy as a bridge to liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Transpl Int. 2010;23:299–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohamed M, Katz AW, Tejani MA, Sharma AK, Kashyap R, Noel MS, et al. Comparison of outcomes between SBRT, yttrium-90 radioembolization, transarterial chemoembolization, and radiofrequency ablation as bridge to transplant for hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2016;1:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brade AM, Ng S, Brierley J, Kim J, Dinniwell R, Ringash J, et al. Phase 1 trial of sorafenib and stereotactic body radiation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94:580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yen C, Sharma R, Rimassa L, Arizumi T, Bettinger D, Choo HY, et al. Treatment stage migration maximizes survival outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib: an observational study. Liver Cancer. 2017;6:313–324. doi: 10.1159/000480441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao Y, Cai G, Zhou L, Liu L, Qi X, Bai M, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma with vascular invasion or extrahepatic metastasis: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2013;9:357–364. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Desar IME, Braam PM, Kaal SEJ, Gerritsen WR, Oyen WJG, van der Graaf WTA. Abscopal effect of radiotherapy in a patient with metastatic diffuse-type giant cell tumor. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:1510–1512. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1243805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brix N, Tiefenthaller A, Anders H, Belka C, Lauber K. Abscopal, immunological effects of radiotherapy: narrowing the gap between clinical and preclinical experiences. Immunol Rev. 2017;280:249–279. doi: 10.1111/imr.12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu ZI, McArthur HL, Ho AY. The abscopal effect of radiation therapy: what is it and how can we use it in breast cancer? Curr Breast Cancer Rep. 2017;9:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s12609-017-0234-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siva S, MacManus MP, Martin RF, Martin OA. Abscopal effects of radiation therapy: a clinical review for the radiobiologist. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohba K, Omagari K, Nakamura T, Ikuno N, Saeki S, Matsuo I, et al. Abscopal regression of hepatocellular carcinoma after radiotherapy for bone metastasis. Gut. 1998;43:575–577. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.4.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miyanaga O, Shirahama M, Ishibashi H. A case of remission in metastatic lung tumor from hepatocellular carcinoma after combined CDDP and PSK therapy (in Japanese) Gan No Rinsho. 1990;36:527–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakanishi M, Chuma M, Hige S, Asaka M. Abscopal effect on hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1320–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01782_13.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Okuma K, Yamashita H, Niibe Y, Hayakawa K, Nakagawa K. Abscopal effect of radiation on lung metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:111. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Popp I, Grosu AL, Niedermann G, Duda DG. Immune modulation by hypofractionated stereotactic radiation therapy: therapeutic implications. Radiother Oncol. 2016;120:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hong Rim C, Yong Kim C, Sik Yang D, Sup Yoon W. Comparison of radiation therapy modalities for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Radiother Oncol. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.11.013. DOI: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kulik LM, Carr BI, Mulcahy MF, Lewandowski RJ, Atassi B, Ryu RK, et al. Safety and efficacy of 90Y radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with and without portal vein thrombosis. Hepatology. 2008;47:71–81. doi: 10.1002/hep.21980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bujold A, Massey CA, Kim JJ, Brierley J, Cho C, Wong RKS, et al. Sequential phase I and II trials of stereotactic body radiotherapy for locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1631–1639. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data