This article assesses the association of hematologic parameters before starting high‐dose methotrexate‐based chemotherapy with the clinical evolution of primary central nervous system lymphoma, providing insight on the potential clinical value of blood test results as a simple surrogate marker of clinical outcome in this rare lymphoma.

Keywords: Primary central nervous system lymphoma, Prognosis, Hemoglobin, Blood test, C‐index

Abstract

Background.

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a rare subtype of extranodal lymphoma. Despite established clinical prognostic scoring such as that of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) and the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group, outcome prediction needs to be improved. Several studies have indicated an association between changes in hematologic laboratory parameters with patient outcomes in PCNSL. We sought to assess the association between hematological parameters and overall survival (OS) in patients with PCNSL.

Methods.

Pretreatment blood tests were analyzed in patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL (n = 182), and we divided the analysis into two cohorts (A and B, both n = 91). OS was evaluated using the Cox proportional hazards models and log‐rank test. Furthermore, the accuracy of the different multivariate models was assessed by Harrell's concordance index (C‐index).

Results.

Using prechemotherapy blood tests, anemia was found in 38 patients (41.8%) in cohort A and 34 patients (37.4%) in cohort B. In univariate analysis, anemia (<12 g/dL in women and <13 g/dL in men) was significantly associated with OS. None of the other blood tests parameters (neutrophils, lymphocyte, or platelets counts) or their ratios (neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil‐to‐platelets ratio) were associated with OS. In multivariate analysis, after adjusting by MSKCC score, anemia remained an independent prognostic factor. Interestingly, the prediction accuracy of OS using Harrell's C‐index was similar using anemia or MSKCC (mean C‐index, 0.6) and was increased to 0.67 when combining anemia and MSKCC.

Conclusion.

The presence of anemia was associated with poor prognosis in both cohorts of PCNSL. Validation of these results and biologic role of hemoglobin levels in PCNSL requires further investigation.

Implications for Practice.

The prediction of the outcome of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) using the most frequently used scores (i.e., Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [MSKCC] or International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group) needs to be improved. We analyzed a large cohort of PCNSL to dissect the potential prognostic value of blood tests in this rare entity. We found anemia as an independent predictor for overall survival in PCNSL. Interestingly, the accuracy to predict PCNSL outcome was improved using hemoglobin level. This improvement was additional to the currently used clinical score (i.e., MSKCC). Finally, none of the other blood tests parameters or their ratios had a prognostic impact in this study.

Introduction

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a rare extranodal non‐Hodgkin lymphoma involving the central nervous system, the eyes, or the meninges. More than 90% of PCNSLs belong to the diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) subtype and more precisely to the activated B‐cell expression phenotype [1]. PCNSL is associated with a dismal prognosis, and there is a broad range of clinical heterogeneity within this entity [2]. Furthermore, the chemotherapy response is also heterogeneous. Despite a high rate of objective response to initial standard high‐dose methotrexate‐based chemotherapy (HD‐MTX), half of patients present short‐lasting relapse, and about one‐third are refractory. Thus, several prognostic indexes have been proposed to stratify the clinical evolution of PCNSL. Among them, the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IESLG) score [3] and a simplified version, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) [4] score, are the most frequently used. The first one is based on a large retrospective study of 378 patients from 48 centers; however, only 105 patients had complete data for inclusion in the model, and the median follow‐up was relatively short, only 24 months [3]. The IESLG found age, performance status, serum lactate dehydrogenase level, cerebrospinal fluid protein concentration, and deep brain location to be significantly associated with outcome [3]. However, this score could not be confirmed by others [4]. Afterward, a study involving 338 patients recruited during two decades used a recursive‐partitioning analysis and a validation using data from the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 8806 and 9310 clinical trials [5], [6]. In the MSKCC score, patients are separated into three different groups according to age and Karnofsky Perfomance Status (KPS) [4]. These groups are (a) age ≤ 50 years, (b) age > 50 years and KPS ≥ 70%, and (c) age > 50 years with a KPS score < 70% [4]. Although these scores provide an easy approach to predict the clinical outcome of PCNSL, they should be further improved and should be updated with patients treated with the standard HD‐MTX regimen [7]. In this line, different recent studies suggest that simple blood tests used in real‐life clinical practice may provide relevant insight on the clinical evolution of different cancers as well as DLBCL and PCNSL [8], [9], [10]. In addition, other studies have also suggested that the hemoglobin value could be a simple easy‐to‐use biological marker of the prognosis in DLBCL [11], [12], [13]. However, these studies have been performed in small selected cohorts of PCNSL, and the external validity or the potential clinical use in a real‐life cohort of PCNSL is not well established.

Here, we assessed the association of hematologic parameters before starting HD‐MTX with the clinical evolution of PCNSL. We used a single center cohort of 182 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL to provide further insight on the potential clinical value of blood test results as a simple surrogate marker of clinical outcome in PCNSL.

Material and Methods

We retrospectively collected data from all patients with PCNSL treated at Groupe Hospitalier Pitié‐Salpêtrière from January 2011 to February 2018 with available clinical follow‐up and blood tests results before chemotherapy. All patients were biopsy proven, were HIV negative, did not have any personal history of immunosuppression or organ transplantation, and did not have previous diagnosis of DLBCL. The patients were treated according to the national guidelines of the French Lymphome Oculo‐Cérébral Network. This study was conducted in accordance to good clinical practices of our local legislation.

The blood tests used in this study represented the blood drawn taken before chemotherapy. The following blood tests data were collected: hemoglobin (Hb) level, total white blood cell count (WBC), absolute neutrophil, lymphocyte, and platelet counts. Normal ranges were those of the clinical laboratory at Groupe Pitié‐Salpêtrière, Paris, France.

Missing data (<10%) were imputed using the mice R package (version 3.0.0) using the predictive mean matching method and 50 iterations [14]. We split our cohort in two equal‐sized datasets, cohort A and cohort B, using the sample function from R software with a seed to easily reproduce our results.

Comparisons of the clinical and biological features of the different cohorts, with or without corticosteroids, were performed with Fisher's exact test for discrete variables and the Mann‐Whitney U test was used for continuous variables.

We estimated the survival impact of different covariates: MSKCC score [4], Hb level, neutrophils, lymphocyte, platelets, and the different ratios between them (e.g., neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio [NLR]; platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio [PLR]) at the time of diagnosis before starting chemotherapy. Normal ranges were obtained based on the clinical laboratory at Groupe Hospitalier Pitié‐Salpêtrière. We defined leukocytosis as WBC >11.0 billion (bil) per L, neutrophilia as absolute neutrophil count >7.5 bil/L, lymphocytosis as absolute count >4 bil/L, lymphopenia as absolute count <1.5 bil/L, and prechemotherapy anemia as Hb value less than 12 g/dL in women and less than 13 g/dL in men [15]. We have binarized all ratio parameters by the median value of every cohort.

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the length of time from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or the last follow‐up. Then, we performed a univariate analysis of survival impact on OS from the different blood test parameters according to the log‐rank test, using binarized variable (i.e., by median or using the previously defined anemia cutoff). Next, we constructed different survival models using the Cox proportional hazard ratio with the covariates that had a log‐rank test p < .1 in cohorts A and B including anemia as a binary or as continuous covariate. Hazard ratios (HRs) were reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Finally, we compared the different multivariate Cox models using Harrell's concordance‐index (C‐index) [16], [17]. This index can be interpreted as a receiver operating curve for survival; the closer to 1 is this value, the better is the survival classification. Harrell's C‐index was implemented using the mlr R package (version 2.12.1) [18]. We used a 5‐fold cross‐validation procedure to fit a candidate model for the primary outcome using data from four of the five blocks in cohort A and cohort B in order to reduce overfitting [19].

All the analyses were performed with R software (version 3.4.3). A p value of less than .05 was considered as significant. All tests were two‐sided.

Results

Description of the Population

We included 182 patients with PCNSL treated at Groupe Hospitalier Pitié‐Salpêtrière from January 2011 to February 2018. Because of the rarity of this entity, we were not able to obtain a prospective validation cohort, and we decided to divide our population into two randomly split cohorts, cohort A and cohort B, both with 91 patients. The details on the distribution of the main clinical and blood tests values are summarized in Table 1.

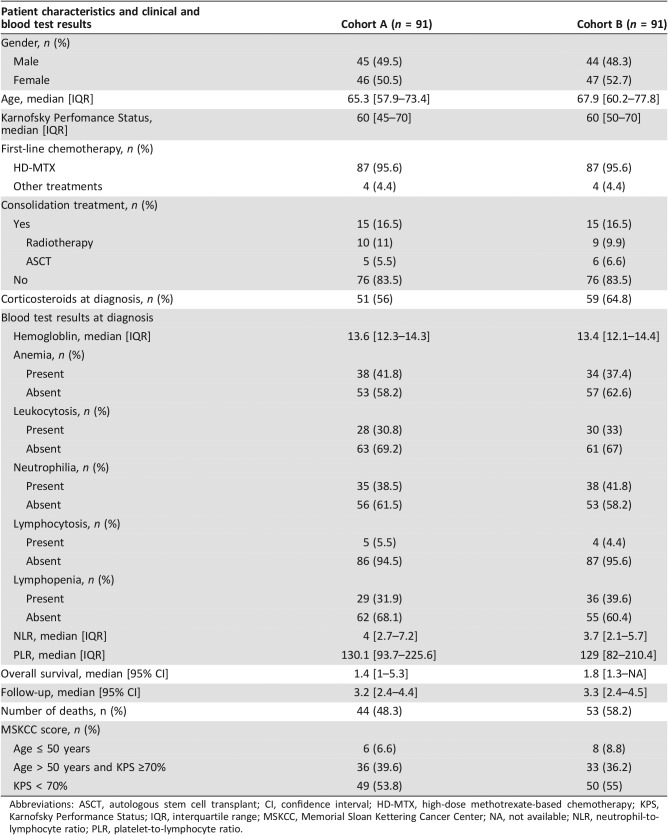

Table 1. Distribution of clinical and blood test results in cohorts A and B.

Abbreviations: ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CI, confidence interval; HD‐MTX, high‐dose methotrexate‐based chemotherapy; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; IQR, interquartile range; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; NA, not available; NLR, neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio.

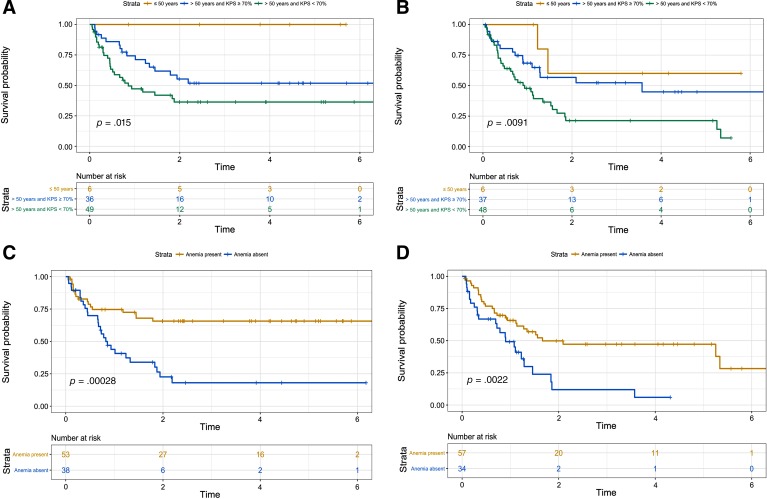

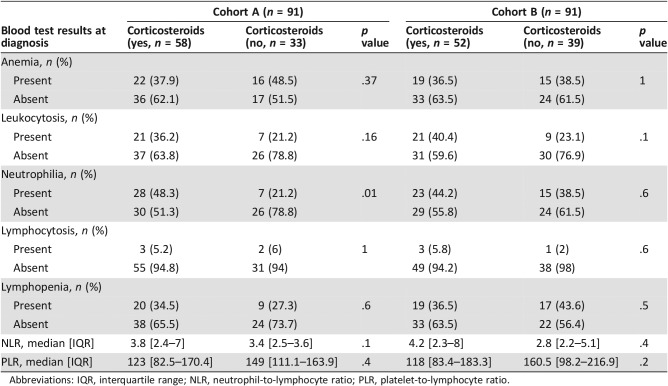

Participants in both cohorts were elderly patients with a median age at diagnosis more to 65 years (Table 1). The gender ratio showed an equal distribution of men and woman (male‐to‐female ratio of 0.98 and 0.94 in cohorts A and B, respectively), Table 1. Sixty‐eight (63.7%) and 52 (57.1%) patients in cohort A and cohort B had a history of corticosteroid use prior to chemotherapy. We also compared the potential impact of corticosteroids on the blood test values because more than half of patients were under this treatment at the moment of the blood test (supplemental online Table 1). The different clinical and biological values were distributed similarly when comparing treatment. Only neutrophilia was less frequently found in patients receiving corticosteroids in cohort A, but not in cohort B (supplemental online Table 1). Patients received standard HD‐MTX regimens in more than 95% of cases (eight patients received other chemotherapy regimens because of methotrexate‐based chemotherapy contraindication; Table 1). Moreover, consolidation treatments were performed (i.e., radiotherapy or autologous stem cell transplant) in the same proportion (16.5% of patients in both cohorts; Table 1). This low rate of consolidation treatment could be explained by only 27.4% of patients (50/182) being aged less than 60 years and eligible for this treatment. Patients’ median follow‐up in both cohorts was more than 3 years (Table 1). In total, 97 out of 182 (53.2%) patients died (Table 1). As expected, Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis showed that MSKCC score could stratify PCNSL prognosis in cohorts A and B (p = .015 and .009, respectively; Fig. 1A, B).

Figure 1.

Univariate survival analysis using Kaplan‐Meier curves showing the prognostic impact of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) score and of anemia in cohorts A and B. (A): Impact of the presence of MSKCC score on overall survival in primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL), cohort A. (B): Impact of the presence of MSKCC score on overall survival in PCNSL, cohort B. (C): Impact of the presence of anemia on overall survival in PCNSL, cohort A. (D): Impact of the presence of anemia on overall survival in PCNSL, cohort B.

Abbreviation: KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status.

Impact of WBC on OS

Leukocytosis.

More than 30% of patients in both cohorts presented with leukocytosis (Table 1). Univariate analysis showed that leukocytosis was not associated with OS in this study (log‐rank p = .4 in both cohorts; Table 2).

Table 2. Univariate and Cox proportional hazard multivariate analysis.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NLR, neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio.

Neutrophil, Lymphocyte, and Platelet Counts and Their Ratios.

We have analyzed the potential impact of neutrophilia, lymphocytosis, and lymphopenia, as well as the different ratios between them that have been previously associated as having prognostic impact in other types of solid cancers or diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas [10], [12], [20], [21], [22]. Only PLR showed a nonrobust prognostic impact on OS (p = .04 in cohort A but p = .7 in cohort B; Table 2). The rest of WBC or platelet did not show any prognostic impact in this study (Table 2).

Anemia and Hemoglobin as a Prognostic Factor of OS in PCNSL.

We identified anemia in more than a third of patients in both cohorts (Table 1). The distribution of hemoglobin was very similar with median values of 13.6 g/dL and 13.4 g/dL, also considering the stratification by gender (supplemental online Fig. 1A). More importantly, the distribution of the hemoglobin values was homogenously assigned among the three different categories of the MSKCC score (supplemental online Fig. 1B). Kaplan‐Meier analysis indicated that the presence of anemia was a significant predictor of poor OS in both cohorts (Fig. 1C, D). In addition, anemia was independently associated with poor prognosis in Cox multivariate analysis (HR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.5–5; p = .001 in cohort A and HR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.4–4.4; p = .001; Table 2). Furthermore, when Hb values were used as a continuous variable, we found that they remained a statistically significant parameter for OS (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.62–0.91; p = .004 in cohort A and HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63–0.96; p = .02, in cohort B). In addition, these results were not modified when we added gender as a covariate in the Cox model (not shown). Accordingly, when we used the whole cohort of patients, the results were the same (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.67–0.88; p < .001; not shown). This finding suggested that a unit decrease in the Hb level was associated with approximately a 25% increase in the rate of death.

Cox Proportional Hazards Ratio and Harrell's C‐Index.

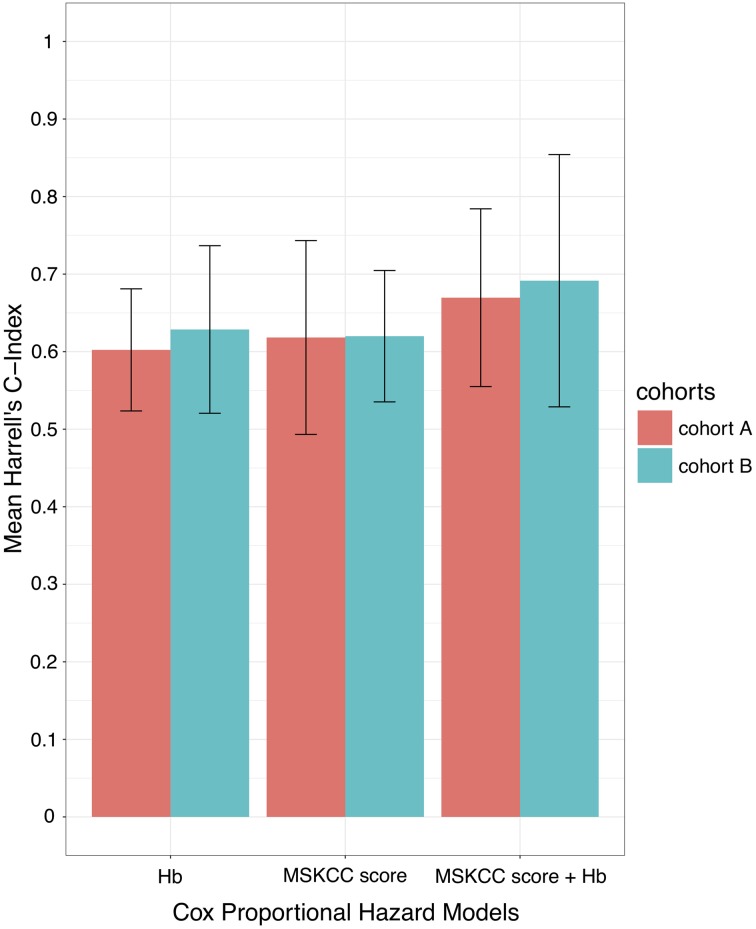

In order to compare the different Cox proportional hazards models and to better quantify the overall adequacy to predict the clinical evolution using OS, we used Harrell's C‐index [16]. Interestingly, the Cox model using only anemia achieved a mean C‐index of 0.6 (SD, 0.07) in cohort A and 0.62 (SD, 0.1) in cohort B, a performance similar to the one achieved by the MSKCC score (C‐index = 0.62 in both cohorts; Fig. 2). Remarkably, when we included MSKCC and anemia in the Cox model, the prediction of OS was higher than using clinical or biological data separately (C‐index, 0.66; SD, 0.11 in cohort A and C‐index, 0.69; SD, 0.16 in cohort B). Therefore, there was a gain in the accuracy of the prediction of survival by combining anemia with MSKCC score (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Bar plots representing the mean value of 5‐fold cross‐validations of Harrell's C‐index of three different Cox proportional hazard models: anemia alone, MSKCC score alone, and combining anemia plus MSKCC score in cohorts A and B. The error bars represent the standard error of the Harrell's C‐index.

Abbreviations: C‐index, concordance index; Hb, hemoglobin; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Discussion

The outcome prediction of PCNSL remains challenging. The MSKCC score is a simplified version of the IESLG, validated with two clinical trials, but only one of these trials used the standard HD‐MTX regimen [5], [6]. However, further efforts should be made to improve the clinical outcome of real‐life patients using HD‐MTX. In this study, the vast majority of patients were treated using HD‐MTX regimen (more than 95% in both cohorts) with a median age above 65 years and a relatively poor baseline clinical status (median KPS, 60%). We sought to identify pretreatment biological parameters that predict or improve the accuracy of prediction of the clinical course of PCNSL compared with the currently used the MSKCC score [4]. Our study identified Hb level and anemia as having prognostic impact in PCNSL.

Prechemotherapy hematologic testing is routine in all patients and can easily be widely used to improve the accuracy of the prediction the clinical evolution of PCNSL in combination with MSKCC. Indeed, we have also assessed the accuracy of prediction of the different multivariate models using Harrell's C‐index and found a similar degree of prediction accuracy using either anemia or MSKCC (C‐index roughly 0.6 in both models). Interestingly, this accuracy was improved when we added MSKCC and anemia with a mean C‐index of 0.67. Therefore, the role of anemia on the prognostic prediction is complementary to the currently used MSKCC score.

Our results are in accordance with previous findings regarding the prognostic value of Hb level in solid and hematologic malignancies with a poor prognosis found when anemia is present [11], [12], [13], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]. It should be noted that different cutoffs have been used to define anemia (i.e., <10 g/dL, <12 g/dL for women or 13 g/dL in men, <11.85 g/dL, etc.). However, we showed that hemoglobin was robustly associated with poor prognosis using either hemoglobin level as a continuous variable or the aforementioned cutoff (supplemental online Table 1).

Anemia is a frequent finding in patients with cancer, occurring in more than 40% of cases [28]. In addition, in patients treated with chemotherapy, the incidence of anemia may rise to 90% [29]. Furthermore, anemia exerts a negative effect on the quality of life of patients with cancer, as it may contribute to cancer‐induced fatigue [30].

In patients with DLBCL, Hb level is also a potential prognostic factor associated with poor prognosis in pretreated patients [11], [12], [24], [26]. Interestingly, in DLBCL, anemia may be associated in part with the tumor‐promoting effect of inflammatory cytokines like IL‐6 [31].

We did not find any statistically significant association between neutrophil, lymphocyte, or platelets or their ratios like NLR and PLR, as has been previously suggested in other studies in in solid tumors as well as in brain tumors, DLBCL, and PCNSL [8], [10], [20], [21], [22], [32], [33]. A recent retrospective study analyzing the potential prognostic impact of NLR in a cohort of 62 patients with PCNSL showed that high NLR (≥2) was associated with poor prognosis in univariate analysis but not in multivariate analysis [10]. In the same line, there are contradictory results regarding the impact of NLR in DLBCL [21], [22], [34].

This study has several limitations that should be discussed. This is a retrospective single center study, it is an exploratory analysis, and there are potential confounding factors for anemia. In addition, more than half of patients were under corticosteroids. This could certainly modify the blood test, but its impact on Hb level is probably less important. However, we could not exclude other causes of anemia, including chronic illness, inflammation, or bleeding [35]. It is also important to highlight that all the patients had a prechemotherapy Hb level higher than 8 g/dL (our standard cutoff used in red blood cell transfusion) [36], potentially leading to a delayed treatment. Future studies will require following these changes longitudinally, after HD‐MTX.

Conclusion

Our study found a prognostic association of prechemotherapy anemia or Hb level in patients with PCNSL. If our results are validated in an independent cohort, it could potentially be used as one prechemotherapy predictor for poor prognosis in these patients. In addition, there is a need for future research studies to better understanding the biologic role of Hb level in PCNSL.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Khê Hoang‐Xuan, Agusti Alentorn

Provision of study material or patients: My Le, Karima Mokhtari, Caroline Houillier

Collection and/or assembly of data: My Le, Ytel Garcilazo, Maria‐José Ibáñez‐Juliá, Nadia Younan, Louis Royer‐Perron, Marion Benazra, Karima Mokhtari, Caroline Houillier, Khê Hoang‐Xuan, Agusti Alentorn

Data analysis and interpretation: My Le, Ytel Garcilazo, Maria‐José Ibáñez‐Juliá, Nadia Younan, Louis Royer‐Perron, Marion Benazra, Karima Mokhtari, Caroline Houillier, Khê Hoang‐Xuan, Agusti Alentorn

Manuscript writing: My Le, Ytel Garcilazo, Maria‐José Ibáñez‐Juliá, Nadia Younan, Louis Royer‐Perron, Marion Benazra, Karima Mokhtari, Caroline Houillier, Khê Hoang‐Xuan, Agusti Alentorn

Final approval of manuscript: My Le, Ytel Garcilazo, Maria‐José Ibáñez‐Juliá, Nadia Younan, Louis Royer‐Perron, Marion Benazra, Karima Mokhtari, Caroline Houillier, Khê Hoang‐Xuan, Agusti Alentorn

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Camilleri‐Broët S, Crinière E, Broët P et al. A uniform activated B‐cell‐like immunophenotype might explain the poor prognosis of primary central nervous system lymphomas: Analysis of 83 cases. Blood 2006;107:190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoang‐Xuan K, Bessell E, Bromberg J et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: Guidelines from the European Association for Neuro‐Oncology. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:e322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreri AJM, Blay JY, Reni M et al. Prognostic scoring system for primary CNS lymphomas: The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group experience. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrey LE, Ben‐Porat L, Panageas KS et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: The Memorial Sloan‐Kettering Cancer Center prognostic model. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:5711–5715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz C, Scott C, Sherman W et al. Preirradiation chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone for primary CNS lymphomas: Initial report of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group protocol 88‐06. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:556–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeAngelis LM, Seiferheld W, Schold SC et al. Combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study 93‐10. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:4643–4648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoang‐Xuan K, Taillandier L, Chinot O et al. Chemotherapy alone as initial treatment for primary CNS lymphoma in patients older than 60 years: A multicenter phase II study (26952) of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor Group. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2726–2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorente D, Mateo J, Templeton AJ et al. Baseline neutrophil‐lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with survival and response to treatment with second‐line chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer independent of baseline steroid use. Ann Oncol 2015;26:750–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ochi Y, Kazuma Y, Hiramoto N et al. Utility of a simple prognostic stratification based on platelet counts and serum albumin levels in elderly patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol 2017;96:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung J, Lee H, Yun T et al. Prognostic role of the neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio in patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Oncotarget 2017;8:74975–74986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim T, Lee HS, Jeong JY et al. Effect on clinical outcomes of anemia and serum level of ferritin in diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with rituximab combined chemotherapy. Blood 2017;130(suppl 1):4158–4158. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melchardt T, Troppan K, Weiss L et al. Independent prognostic value of serum markers in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma in the era of the NCCN‐IPI. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 2015;13:1501–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troppan KT, Melchardt T, Deutsch A et al. The significance of pretreatment anemia in the era of R‐IPI and NCCN‐IPI prognostic risk assessment tools: A dual‐center study in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma patients. Eur J Haematol 2015;95:538–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jolani S, Debray TPA, Koffijberg H et al. Imputation of systematically missing predictors in an individual participant data meta‐analysis: A generalized approach using MICE. Stat Med 2015;34:1841–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M et al. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood 2014;123:615–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB. Overall C as a measure of discrimination in survival analysis: Model specific population value and confidence interval estimation. Stat Med 2004;23:2109–2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bischl B, Schiffner J, Weihs C. Benchmarking local classification methods. Comput Stat 2013;28:2599–2619. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith GCS, Seaman SR, Wood AM et al. Correcting for optimistic prediction in small data sets. Am J Epidemiol 2014;180:318–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keam B, Ha H, Kim TM et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio improves prognostic prediction of International Prognostic Index for patients with diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone. Leuk Lymphoma 2015;56:2032–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porrata LF, Ristow K, Habermann T et al. Predicting survival for diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma patients using baseline neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio. Am J Hematol 2010;85:896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Zhou X, Liu Y et al. Prognostic significance of neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma: A meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0176008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caro JJ, Salas M, Ward A et al. Anemia as an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients with cancer: A systemic, quantitative review. Cancer 2001;91:2214–2221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams HJA, de Klerk JMH, Fijnheer R et al. Prognostic value of anemia and C‐reactive protein levels in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2015;15:671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Céfaro GA, Genovesi D, Vinciguerra A et al. Prognostic impact of hemoglobin level and other factors in patients with high‐grade gliomas treated with postoperative radiochemotherapy and sequential chemotherapy based on temozolomide: A 10‐year experience at a single institution. Strahlenther Onkol Organ Dtsch Rontgengesellschaft Al 2011;187:778–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chien SH, Tzeng CH, Chiou TJ et al. Anemia is an important prognostic factor for very elderly patients with diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma treated with rituximab and attenuated chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(suppl 15):e20518. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dubsky P, Sevelda P, Jakesz R et al. Anemia is a significant prognostic factor in local relapse‐free survival of premenopausal primary breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant cyclophosphamide/methotrexate/5‐fluorouracil chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:2082–2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knight K, Wade S, Balducci L. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Am J Med 2004;116(suppl 7A):11S–26S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tas F, Eralp Y, Basaran M et al. Anemia in oncology practice: Relation to diseases and their therapies. Am J Clin Oncol 2002;25:371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stasi R, Abriani L, Beccaglia P et al. Cancer‐related fatigue: Evolving concepts in evaluation and treatment. Cancer 2003;98:1786–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tisi MC, Bozzoli V, Giachelia M et al. Anemia in diffuse large B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma: The role of interleukin‐6, hepcidin and erythropoietin. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55:270–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopes M, Carvalho B, Vaz R et al. Influence of neutrophil‐lymphocyte ratio in prognosis of glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol 2018;136:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Zhang S, Song Y et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio in patients with glioma. Oncotarget 2017;8:59217–59224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groopman JE, Itri LM. Chemotherapy‐induced anemia in adults: Incidence and treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:1616–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spivak JL. The anaemia of cancer: Death by a thousand cuts. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:543–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bokemeyer C, Aapro MS, Courdi A et al. EORTC guidelines for the use of erythropoietic proteins in anaemic patients with cancer: 2006 update. Eur J Cancer 2007;43:258–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]