Abstract

Purpose of review

Sensitive, scalable and affordable assays are critically needed for monitoring the success of interventions for preventing, treating and attempting to cure HIV infection. This review evaluates current and emerging technologies that are applicable for both surveillance of HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) and characterization of HIV reservoirs that persist despite antiretroviral therapy and are obstacles to curing HIV infection.

Recent findings

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has the potential to be adapted into high-throughput, cost-efficient approaches for HIVDR surveillance and monitoring during continued scale-up of antiretroviral therapy and rollout of preexposure prophylaxis. Similarly, improvements in PCR and NGS are resulting in higher throughput single genome sequencing to detect intact proviruses and to characterize HIV integration sites and clonal expansions of infected cells.

Summary

Current population genotyping methods for resistance monitoring are high cost and low throughput. NGS, combined with simpler sample collection and storage matrices (e.g. dried blood spots), has considerable potential to broaden global surveillance and patient monitoring for HIVDR. Recent adaptions of NGS to identify integration sites of HIV in the human genome and to characterize the integrated HIV proviruses are likely to facilitate investigations of the impact of experimental ‘curative’ interventions on HIV reservoirs.

Keywords: HIV cure, HIV drug resistance, HIV integration, HIV reservoirs, next-generation sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Sensitive, scalable and affordable assays are urgently needed for monitoring the success of interventions for preventing, treating and attempting to cure HIV infection. Eighteen million individuals are currently on antiretroviral therapy (ART), and recent UNAIDS targets aim to increase that number to 90% of all infected individuals [1]. Concurrently, preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) roll out with oral tenofovir/emtricitabine, which is also a key component of first-line ART, is planned for thousands of at-risk individuals throughout sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and the United States. The spread of drugesistant HIV remains the greatest threat to undermining the public health benefit of ‘Test and Treat’ [2] and PrEP rollout [3], yet resistance monitoring is not currently widely available because of high cost and low throughput. This situation is unlikely to change without technological advances that have major effects on cost and capacity.

Although ART and PrEP have the potential to lower HIV incidence, both approaches require drug adherence and continual drug supply, which are resource-intensive. The report of the ‘Berlin Patient’ in 2009, who was cured of HIV infection [4], galvanized worldwide efforts to achieve an affordable and scalable cure of HIV that would reduce HIV transmission without the need for lifelong ART. A major obstacle to progress toward an HIV cure has been difficulty in quantifying and characterizing the HIV reservoir that leads to viral relapse after ART is stopped. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is now being adapted to help identify intact (replication competent) HIV proviruses and their integration sites in the human genome. The latter application led to the recognition that clonal expansions of HIV infected cells are common. Further refinements of NGS assays should facilitate the assessment of efficacy of experimental interventions aimed at reducing HIV reservoirs and controlling HIV.

The current review discusses limitations of current assays for drug resistance surveillance and HIV cure research, recent advances in application of NGS as potential solutions and important improvements that are needed to realize the full potential of NGS assays.

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT HIV DRUG RESISTANCE SURVEILLANCE TECHNOLOGIES

Current assays to identify HIV-1 drug resistance mutations have relied on population sequencing of the HIV-1 protease (pro) and reverse transcriptase genes or on identifying specific point mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase associated with resistance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Technologic approaches for HIV drug resistance testing

| Category | Type | Assay | Application | Unique features | Status | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population-based | Sanger ‘Standard’ sequencing | Viroseq | Centralized | Genotyping HIV-1 protease gene from codons 1–99 and RT gene from codons 1–335 | Commercially available | [5,6■■] |

| Cost 120 USD per sample, VL threshold =2000cpm, Sensitivity >20% | ||||||

| Sanger ‘Standard’ sequencing | TruGene | Centralized | Genotyping HIV-1 protease gene from codons 4–99 and RT codons 38–248 | Discontinued | [7] | |

| Cost 150 USD per sample, VL threshold = 200cpm | ||||||

| Sanger ‘Standard’ sequencing | In-house | Centralized | Genotyping for non-B subtypes and flexible amplification of resistance codons | In development | [5,8–10] | |

| Cost 50–150 USD per sample | ||||||

| Sensitive | NGS | Illumina | Centralized | Detection of minor variants using unique tagging of individual virion genomes | In development | [11■] |

| High number of reads per run, but the read lengths are shorter than 454 | ||||||

| NGS | 454 Pyrosequencing | Centralized | Longer read lengths, but limited to 1 million reads, high error rates with polybases >6 | In development | [12] | |

| Point mutation assay PCR primer amplification | ASPCR | Point-of-care | Selective amplification of PCR product by match or mismatch of 3’ end of primer | In development | [13] | |

| Cost <5 USD per sample, low VL threshold, problems with specificity (polymorphisms) | ||||||

| Point mutation assay PCR primer ligation | OLA | Point-of-care | Selective ligation of tagged-oligonucleotides on HIV PCR product by match or mismatch of 3’ end of primer, ligated-oligonucleotides can be identified with ELISA, plate or paper capture detection methods | Currently field testing in Kenya: Clinical trial: NCT01898754 | [14–16] | |

| Point mutation assay PCR primer ligation | LRA | Point-of-care | Simplified ligation amplification assay using a one-step single-buffer method and sequence-specific dual-labeled probe for detection | In development | [17,18] | |

ASPCR, allele-specific PCR; LRA, one-step ligation on RNA amplification; NGS, next-generation sequencing; OLA, oligonucleotide ligation assay; RT, reverse transcriptase; VL, viral load.

Standard genotyping

Population genotyping remains the current clinical standard for assessment of HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) mutations in individuals who seroconvert while using PrEP, for individuals starting ART (i.e. pretreatment or transmitted resistance) and for individuals on failing ART regimens. The Abbott Molecular ViroSeq HIV-1 is the only commercially available genotyping system for HIVDR assessment since Siemens discontinued TruGene HIV-1 in 2014 [6■■]. Standard genotyping assays have a high cost per sample (>150 USD), require high minimum viral loads (2000 copies/ml), have limited gene coverage (up to codon 335 in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase), are variably successful in genotyping nonsubtype B HIV-1, and only detect resistant variants that comprise more than 20% of the virus population in a sample [5,19–22]. Several in-house assays have reported improved performance for sequencing nonsubtype B HIV-1 and have significantly reduced the cost over commercial assays (to approximately 50–150 USD), but these methods remain labor-intensive with a high burden of manual data analysis and lack scalability [5,8–10].

Point mutation assays

Several real-time PCR-based point mutation assays (PMA) including allele-specific PCR [13], oligo-ligation assay [23], one-step ligation on RNA amplification [17] and pan-degenerate amplification and adaptation [24] have improved sensitivity (0.01–5%), lower cost per sample (<5 USD) and higher throughput capacity relative to standard genotyping (Table 1). However, large-scale implementation of PMAs has stalled due to issues with primer binding site polymorphisms and mutant codon variants, such as E138E/A/G/K that compromise assay specificity and increase assay complexity and cost [25,26]. Although recent advances in PMAs can accommodate the simultaneous detection of multiple mutations, analysis of mutation combinations, such as thymidine analog mutations for zidovudine resistance, remains challenging [27].

NEXT-GENERATION SEQUENCING FOR PREEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS AND ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY RESISTANCE MONITORING

NGS has the potential to be adapted into a high-throughput, low-cost HIVDR assay with low frequency mutation detection at 1–5% [5,28■■,29]. For NGS to be implementation-ready for HIVDR surveillance, improvements in nucleic acid preservation and simplification of assay procedures and data analysis are needed.

Current next-generation sequencing assays for sensitive detection of low-frequency resistance

NGS has the capacity to simultaneously obtain reads from millions of copies of HIV genomes per run enabling the potential detection of low-frequency viral quasispecies. The addition of patient identifiers (index sequences) enables multiplexing of samples to increase throughput and reduce cost per genotype relative to standard sequencing [30,31].

Earlier studies using the 454 platform could detect mutants at 1% frequency, but accuracy was compromised by PCRbias and sequencing errors. The newer Illumina platform has increased fidelity and reliability with shorter, more processive reads during NGS and can generate a greater number of reads per run [32]. Two recent advances have increased the sensitivity and accuracy of NGS by correcting for PCR resampling, recombination during PCR and sequencing errors. The addition of unique PrimerlDs composed of degenerate bases during cDNA synthesis can correct for preferential PCR amplification by tagging all the sequences derived from a single RNA template. Using bioinformatics, sequences with identical PrimerIDs are collapsed into one consensus, and sequences with gaps, errors or ambiguous bases indicative of PCR error, recombination or sequencing error are removed [11■,33,34]. Recent improvements of sample processing were made by adding the sequencing adaptors with an oligo-ligation step rather than through PCR amplification, which reduces the potential for recombination and lowers the mutant detection frequency to less than 0.1% [35].

The future of next-generation sequencing for resistance monitoring

Although there have been several technical innovations to improve NGS accuracy and precision, further modifications are still needed to simplify sample processing, NGS library preparation and bioinformatics analysis of sequences. Dried blood spot (DBS) technology is currently the WHO-recommended sample collection method in low–middle-income countries (LMIC) for plasma HIV-1 RNA and genotyping assays and has been shown to preserve specimens at ambient temperatures in sufficient quantities for population-based NGS on the 454 plat-form [12,36,37,38■]. There is potential, however, for improvements in DBS; for example, impregnating the filter paper with antioxidants and inhibitors of RNases to preserve HIV RNA templates [39]. Though novel blood storage devices such as HemaSpot (Spot On Sciences, Inc.; Austin, Texas, USA) [40] and Primestore Molecular Transport Media (Longhorn Vaccines and Diagnostics, LLC, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) [41] have improved recovery of HIV nucleic acids over DBS, their cost is too high for widespread use in LMIC. Additional advances in sample throughput could be accomplished by automated sample extraction (e.g. Abbott m2000sp, Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, Illinois, USA) or by replacing laborious sample preparation steps with liquid-handling equipment. Adaptor ligation steps, necessary for sensitive and accurate allele detection by NGS [34,35], could be simplified with commercial adaptor ligation kits and automated liquid handling. Finally, PrimerID bioinformatics scripts that are required for data analysis could be integrated into an automated internet-accessible pipeline processing application. Overall, the future is promising for higher throughput, lower cost and automated NGS plat-forms that will greatly increase accessibility of resistance monitoring for epidemiologic surveillance and patient management.

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT ASSAYS FOR HIV CURE

The HIV reservoir consists of HIV-infected cells carrying intact (replication-competent) proviruses, which are the source of rebounding virus after ART interruption. HIV reservoir assays attempt to either directly quantify intact proviruses or indirectly measure a biomarker that is strongly correlated with the viral reservoirs. The first major challenge of detecting reservoir cells is that they are very rare in peripheral blood or tissues in patients who initiated therapy early [42–44] or who have been on long-term suppressive therapy.

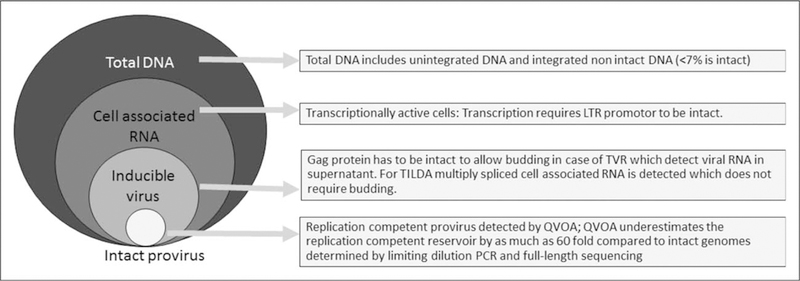

Although total HIV-1 DNA quantity correlates well with the number of infected cells [45], more than 90% of HIV-1 DNA is defective as a result of deletions, insertions, point mutations or apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC)-mediated hypermutation [46■■]. Such defective proviruses accumulate rapidly after acute infection [46■■]. As a consequence, assays of total HIV-1 DNA grossly overestimate the size of the HIV reservoir (Fig. 1). By contrast, the gold standard cell culture-based quantitative viral outgrowth assay (QVOA), which is most specific for the HIV reservoir, underestimates the reservoir relative to intact proviral sequences by as much as 60-fold because not all intact proviruses can be activated with a single round of cell activation [47]. Additional rounds of stimulation increases the yield but still only activate a small proportion of competent proviruses [48■]. Use of QVOA for assessing HIV reservoirs is also limited by large blood volume requirements, high-cost and low throughput. Simplified, culture–based and inducible virus recovery assays are more practicable and sensitive than QVOA but do not detect replication-competent virus [49,50■]. Similarly, current assays to detect intact provirus that rely on limiting dilution PCR and sequencing have low throughput and limited sensitivity (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

What do reservoir assays measure? QVOA, quantitative viral outgrowth assay; TILDA, tat/rev induced limiting dilution assay; TVR, total virus recovery assay [49].

Table 2.

Advantages and limitations of newer HIV reservoir assays

| Assay description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible virus assays: HIV-1 RNA detected in supernatant after cell stimulation | Faster, less costly and more sensitive than QVOA | Does not differentiate inducible virus from replication competent virus |

| Limiting dilution and near full-length sequencing of proviruses | More sensitive for likely replication competent virus than QVOA | Limited throughput; costly; apparently intact proviral genome does not prove infectiousness |

| Fractional single cell assays by limiting dilution PCR | Allows investigation of the contribution of individual cells in transcription and virus production | Limited throughput. High-throughput single cell assays are in development |

| Integration site assays | Investigate the role of clonal proliferation in viral persistence | Current assays have a low throughput and cannot link proviral sequences to integration sites. Not suitable to study the effect of interventions on population size and survival of particular clones |

QVOA, quantitative viral outgrowth assay.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS THAT HAVE IMPROVED UPON HIV PERSISTENCE ASSAYS

Improvement in highly sensitive plasma HIV-1 RNA assays requires sufficiently large volume plasma processing, viral concentration and efficient exclusion of PCR inhibitors and detection of inhibition. This has enabled the detection of low-level viral persistence at levels of less than 1 copy per milliliter of plasma [51]. Similarly, for HIV-1 DNA detection, greater sampling through large blood volume draws or leukapheresis improves the chance of detecting rare HIV-infected cells, whereas the background human DNA signal can be reduced by purification of CD4+ cells or resting CD4+ memory cells [52■■].

Analytical improvements in HIV DNA/RNA detection

High HIV diversity contributes to reduced sensitivity by delaying the threshold cycle when primers or probes mismatch a viral template [53■■]. To address this, the choice of conserved genome targets in integrase [51], gag or the long terminal repeat (LTR) region have improved assay performance and the inclusion of more than one genome target in a multiplex assay has reduced the risk of mismatches to all targets [54,55]. Digitalization of PCR reactions into individual nanoliter or picoliter reactions, followed by detection of the number of positive reactions, has been reported to be more robust to primer mismatches [56] but has limited throughput and is prone to background signal that could be reduced by touchdown PCR [57].

An innovative approach combining the principles of quantitative PCR with digitalization is the use of real-time PCR with multiple replicates at the highest dilution. This is less prone to non-specific background and does not rely on the cycle threshold for the quantification of the highest dilutions [54].

Importance of postanalytical standardization of reporting

When reporting cure assay results, it is important to report the denominator of cells actually assayed [52■■]. This could be achieved by parallel quantification of a human reference gene, which controls for all assay steps.

NEW ASSAYS THAT WILL IMPROVE OUR UNDERSTANDING OF VIRAL PERSISTENCE AND IMPROVE MONITORING OF CURATIVE INTERVENTIONS

Advances in NGS, single cell and fractional expression assays, and assays of integrated provirus are providing new tools to characterize HIV reservoirs.

Next-generation single genome sequencing

Improvements in PCR and NGS will result in higher throughput assays for intact provirus. DNA polymerases with improved processivity and proofreading (3′–5′ exonuclease activity) allows amplification of near–full-length amplicons, but when relying on multiple Sanger sequencing reactions, have limited throughput. Recent NGS platforms (e.g. Pacific Bio-sciences, Menlo Park, California, USA) have improved template read length that allows the sequencing of whole HIV genomes [58■■]. This high-throughput approach has the potential to characterize individual full-length viral genomes and determine which are intact. Viral templates must be diluted to one template per PCR reaction to avoid artifacts from recombination between multiple viral genomes, but this endpoint dilution limits throughput.

Single cell and fractional expression assays

Recently, a limiting dilution assay has been developed to quantify cellular RNA levels expressed by individual cells, showing that the reduction of cellular HIV RNA during successful ART is not due to a smaller proportion of infected cells expressing HIV RNA but due to a smaller fraction of cells expressing high levels of RNA [59■■]. New developments in single cell assays will soon allow the simultaneous investigation of different characteristics of a single cell: the cellular phenotype, HIV-1 DNA and mRNA expression and virion production. Sequencing at a single cellular level could also investigate whether individual genomes are intact or defective [60■].

Assays of integrated provirus

Two assays to detect HIV integration sites have been developed. The one HIV integration site loop amplification assay makes use of primers that have a random 3′ decamer tail and an LTR U5-specific 5′ region, which through several steps generates a stem-loop structure with a known HIV-1 LTR sequence in the stem region and unknown human genome sequence in the loop region. Limiting dilution PCR and sequencing of the individual integration sites allow the design of integration-site specific primers, which together with envelope specific primers allow amplification and sequencing of integration sites and HIV 3′ LTR to envelope. Although elegant, this approach is very labor-intensive and requires multiple PCR and Sanger sequencing reactions [61]. The other integration site assay (ISA) approach involves random ultrasonic shearing of HIV-1 DNA, blunt-end ligation of PCR linkers and amplification of the integration sites with and HIV-1 LTR-specific and linker-specific primer followed by a heminested PCR with another internal HIV-1-specific LTR-specific and linker-specific primer that enriches for HIV integration sites. Integration sites are then characterized by high-throughput Illumina sequencing. This provides an efficient approach but the very short HIV-1 sequence does not allow the linkage of the human genome integration site with specific proviral species [62]. Current proviral ISAs are too insensitive to examine the effect of curative interventions on individual clones and therefore need further development. Future assays should also link full HIV genomes to their integration sites. This will likely be facilitated by long fragment PCR and newer NGS platforms that allow single read sequencing of whole HIV genomes [58■■] to investigate the survival and expansion of cells with specific integrated proviruses (Table 2). This capability will accelerate the understanding of whether experimental interventions affect most cells containing intact proviruses or only a subset as a consequence of variation in host cell and proviral biology.

CONCLUSION

Population-based Sanger sequencing of HIV provided essential, initial insights into HIVDR and has been used for patient monitoring in well resourced settings, but recent advances in sample collection, automated sample processing and sequencing technologies are poised to greatly expand availability of resistance monitoring. Because low-frequency mutations have recently been shown to affect treatment outcome, NGS plat-forms offer the additional advantage of greater sensitivity than population sequencing for detection of minor viral variants.

Higher-throughput quantitative assays of proviral competence are a high priority to assess the effects of interventions on the HIV reservoir size. Recent developments in full-length sequencing show promise and could identify intact proviruses, but have limited throughput. Current assays for HIV integration sites have increased our understanding of clonal expansion as a key mechanism of HIV persistence but further assay refinements are needed to assess the impact of curative interventions on individual clonal populations of infected cells. Such assay refinements and other advances will undoubtedly occur and provide much greater insight into HIV reservoirs and the impact of interventions designed to achieve an HIV cure.

KEY POINTS.

The shortcomings of current methods for HIV drug resistance testing limit global access to resistance monitoring.

Next-generation sequencing technology has the potential to be adapted into a high-throughput, low-cost assay that will expand resistance testing to that needed for ‘Test and Treat’ and PrEP rollout programs.

Advances in DNA polymerase enzymes and next-generation sequencing technologies are providing new tools to characterize HIV reservoirs.

Improvements in the interpretation and throughput of sequencing assays for intact proviruses and clonal expansions of infected cells are needed before they can be applied to assess the impact of experimental interventions on HIV reservoirs.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Lauren Berner and Lorraine Pollini for assistance in preparing this article and Kerri Penrose for helpful discussions.

Financial support and sponsorship

This article is made possible by generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The contents are the responsibility of the University of Pittsburgh and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, PEPFAR or the United States Government. Cooperative agreement AID-OAA-A-15–00031. Support from the AIDS Clinical Trials Group Network (ACTG) to the University of Pittsburgh Virology Specialty Laboratory funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (UM1 AI106701). Support from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract number HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views of policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade name, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

J.W.M. is a consultant to Gilead Sciences and holds share options in Co-Crystal Pharma, Inc. No other conflicts are reported. U.M.P., K.M. and G.V. report no potential conflicts.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

■ of special interest

■■ of outstanding interest

- 1.UNAIDS. 90–90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014; http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/90-90-90, contract no.: UNAIDS /JC2684.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

- 2.Wagner BG, Blower S. Universal access to HIV treatment versus universal ‘test and treat’: transmission, drug resistance & treatment costs. PLoS One 2012; 7:e41212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbas UL, Hood G, Wetzel AW, Mellors JW. Factors influencing the emergence and spread of HIV drug resistance arising from rollout of antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). PLoS One 2011; 6:e1 8165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hütter G, Nowak D, Mossner M, et al. Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 delta32/delta32 stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 692–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inzaule SC, Ondoa P, Peter T, et al. Affordable HIV drug-resistance testing for monitoring of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:e267–e275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Laethem K, Theys K, Vandamme AM. HIV-1 genotypic drug resistance testing: digging deep, reaching wide? Curr Opin Virol 2015; 14:16–23.■■ A thorough review of HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) strategies including the strengths and limitations of surveillance technologies with a focus on next-generation sequencing (NGS) and its application for ‘Deep’ versus ‘Wide’ sequencing analysis.

- 7.Grant RM, Kuritzkes DR, Johnson VA, et al. Accuracy of the TRUGENE HIV-1 genotyping kit. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41:1586–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chew KK, Ng KY, Khong WX, et al. Clinical evaluation of an in-house human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) genotyping assay for the detection of drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 infected patients in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2012; 41:553–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee CK, Lee HK, Loh TP, et al. An in-house HIV genotyping assay for the detection of drug resistance mutations in Southeast Asian patients infected with HIV-1. J Med Virol 2012; 84:394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aitken SC, Bronze M, Wallis CL, et al. A pragmatic approach to HIV-1 drug resistance determination in resource-limited settings by use of a novel genotyping assay targeting the reverse transcriptase-encoding region only. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51:1757–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keys JR, Zhou S, Anderson JA, et al. Primer ID informs next-generation sequencing platforms and reveals preexisting drug resistance mutations in the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase coding domain. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015; 31:658–668.■ This manuscript demonstrates the tagging of individual cDNAs with primer IDs to correct for PCR resampling and sequencing errors, facilitating accurate deep sequencing analysis to identify low-frequency mutations in mixed populations.

- 12.Ji H, Li Y, Graham M, et al. Next-generation sequencing of dried blood spot specimens: a novel approach to HIV drug-resistance surveillance. AntivirTher 2011; 16:871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paredes R, Marconi VC, Campbell TB, Kuritzkes DR. Systematic evaluation of allele-specific real-time PCR for the detection of minor HIV-1 variants with pol and env resistance mutations. J Virol Methods 2007; 146: 136–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelstein RE, Nickerson DA,Tobe VO, et al. Oligonucleotide ligation assay for detecting mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pol gene that are associated with resistance to zidovudine, didanosine, and lamivudine. J Clin Microbiol 1998; 36:569–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung MH, Beck IA, Dross S, et al. Oligonucleotide ligation assay detects HIV drug resistance associated with virologic failure among antiretroviralnaive adults in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 67:246–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villahermosa ML, Beck I, Perez-Alvarez L, et al. Detection and quantification of multiple drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by an oligonucleotide ligation assay. J Hum Virol 2001; 4:238–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Wang J, Coetzer M, et al. One-step ligation on RNA amplification for the detection of point mutations. J Mol Diagn 2015; 17:679–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landegren U, Kaiser R, Sanders J, Hood L. A ligase-mediated gene detection technique. Science 1988; 241:1077–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuritzkes DR, Grant RM, Feorino P, et al. Performance characteristics of the TRUGENE HIV-1 genotyping kit and the opengene DNA sequencing system. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41:1594–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mouafo LC, Pere H, Ndjoyi-Mbiguino A, et al. Letter to the Editor performance of the ViroSeq(R) HIV-1 genotyping system v2.0 in Central Africa. Open AIDS J 2015; 9:9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiam M, Diop-Ndiaye H, Kebe K, et al. Performance of the ViroSeq HIV-1 genotyping system v2.0 on HIV-1 strains circulating in Senegal. J Virol Methods 2013; 188:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eshleman SH, Crutcher G, Petrauskene O, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the ViroSeq human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) genotyping system for detection of HIV-1 drug resistance mutations by use of an ABI PRISM 3100 genetic analyzer. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43:813–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Church JD, Towler WI, Hoover DR, et al. Comparison of LigAmp and an ASPCR assay for detection and quantification of K103N-containing HIV variants. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2008; 24:595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacLeod IJ, Rowley CF, Essex M, editor. Pan Degenerate Amplification and Adaptation for Highly Sensitive Detection of ARV Drug Resistance. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, CROI 2014; 2014 March 3–6, 2014; Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowley CF, Boutwell CL, Lockman S, Essex M. Improvement in allele-specific PCR assay with the use of polymorphism-specific primers for the analysis of minor variant drug resistance in HIV-1 subtype C. J Virol Methods 2008; 149:69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boltz VF, Maldarelli F, Martinson N, et al. Optimization of allele-specific PCR using patient-specific HIV consensus sequences for primer design. J Virol Methods 2010; 164:122–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis GM, Vlaskin TA, Koth A, et al. Simultaneous and sensitive detection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV) drug resistant genotypes by multiplex oligonucleotide ligation assay. J Virol Methods 2013; 192:39–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clutter DS, Jordan MR, Bertagnolio S, Shafer RW. HIV-1 drug resistance and resistance testing. Infect Genet Evol 2016; 46:292–307.■■ Comprehensive overview of HIVDR monitoring detailing the genetic mechanisms, epidemiology and management of HIVDR as well as the implications of HIVDR for patient management at both individual and population levels across diverse economic and geographic settings.

- 29.Hauser A, Kuecherer C, Kunz A, et al. Comparison of 454 ultra-deep sequencing and allele-specific real-time PCR with regard to the detection of emerging drug-resistant minor HIV-1 variants after antiretroviral prophylaxis for vertical transmission. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0140809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casadella M, Paredes R. Deep sequencing for HIV-1 clinical management. Virus Res 2016. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekici H, Rao SD, Sonnerborg A, et al. Cost-efficient HIV-1 drug resistance surveillance using multiplexed high-throughput amplicon sequencing: implications for use in low-and middle-income countries. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69:3349–3355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo C, Tsementzi D, Kyrpides N, et al. Direct comparisons of Illumina vs. Roche 454 sequencing technologies on the same microbial community DNA sample. PLoS One 2012; 7:e30087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou S, Jones C, Mieczkowski P, Swanstrom R. Primer ID validates template sampling depth and greatly reduces the error rate of next-generation sequencing of HIV-1 genomic rNa populations. J Virol 2015; 89:8540–8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jabara CB, Jones CD, Roach J, et al. Accurate sampling and deep sequencing of the HIV-1 protease gene using a Primer ID. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:20166–20171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boltz VF, Rausch J, Shao W, et al. Analysis of resistance haplotypes using primer IDs and next gen sequencing of HIV RNA. Seattle, WA, USA: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2015); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertagnolio S, Parkin NT, Jordan M, et al. Dried blood spots for HIV-1 drug resistance and viral load testing: a review of current knowledge and WHO efforts for global HIV drug resistance surveillance. AIDS Rev 2010; 12:195–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hearps AC, Ryan CE, Morris LM, et al. Stability of dried blood spots for HIV-1 drug resistance analysis. Curr HIV Res 2010; 8:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Tully DC, et al. Use of dried blood spots to elucidate full-length transmitted/founder HIV-1 genomes. Pathog Immun 2016; 1:129–153.■ Study showing that 454 pyrosequencing NGS can be used to genotype from dried blood spot with a high concordance to standard genotyping, from samples with a viral load as low as 1700 copies/ml and an estimated ~50 viral copies per blood spot.

- 39.Li Z, Wu J, Deleo CJ. RNA damage and surveillance under oxidative stress. IUBMB Life 2006; 58:581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks K, DeLong A, Balamane M, et al. HemaSpot, a novel blood storage device for HIV-1 drug resistance testing. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54:223–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gous N, Scott L, Stevens W, editors. Can dried blood spots or whole blood liquid transport media extend access to HIV viral load testing?. Cape Town, South Africa: African Society for Laboratory Medicine; 2014; Abstract 663. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ananworanich J, Puthanakit T, Suntarattiwong P, et al. Reduced markers of HIV persistence and restricted HIV-specific immune responses after early antiretroviral therapy in children. AIDS 2014; 28:1015–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strain MC, Little SJ, Daar ES, et al. Effect of treatment, during primary infection, on establishment and clearance of cellular reservoirs of HIV-1. J Infect Dis 2005; 191:1410–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Josefsson L, von Stockenstrom S, Faria NR, et al. The HIV-1 reservoir in eight patients on long-term suppressive antiretroviral therapy is stable with few genetic changes overtime. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:E4987–E4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Josefsson L, Palmer S, Faria NR, et al. Single cell analysis of lymph node tissue from HIV-1 infected patients reveals that the majority of CD4+ T-cells contain one HIV-1 DNA molecule. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9:e1003432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruner KM, Murray AJ, Pollack RA, et al. Defective proviruses rapidly accumulate during acute HIV-1 infection. Nat Med 2016; 22:1043–1049.■■ This study describes the proportion of HIV DNA that is intact after acute and chronic infection. It emphasizes the small proportion of intact HIV DNA genomes making up the ‘true’ reservoir.

- 47.Ho YC, Shan L, Hosmane NN, et al. Replication-competent noninduced proviruses in the latent reservoir increase barrier to HIV-1 cure. Cell 2013; 155: 540–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bruner KM, Hosmane NN, Siliciano RF. Towards an HIV-1 cure: measuring the latent reservoir. Trends Microbiol 2015; 23:192–203.■ This article reviews current viral culture and PCR-based methods to characterize and quantify the latent reservoir.

- 49.Cillo A, Sobolewski M, Buckley T, Bui J, Cyktor J, Mellors J. editor Latent HIV is missed by assaying only resting CD4+ T cells. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2017); 2017 February 13–16, 2017; Seattle, WA, USA2017. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Procopio FA, Fromentin R, Kulpa DA, et al. A novel assay to measure the magnitude of the inducible viral reservoir in HIV-infected individuals. EBio-Medicine 2015; 2:874–883.■ This manuscript describes the tat/rev induced limiting dilution assay, an inducible virus recovery assay that quantifies cells producing multiply spliced mRNA, after stimulation. It is more practicable than the quantitative virus recovery assay but is not specific for replication competent provirus.

- 51.Cillo AR, Vagratian D, Bedison MA, et al. Improved single-copy assays for quantification of persistent HIV-1 viremia in patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:3944–3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hong F, Aga E, Cillo AR, et al. Novel assays for measurement of total cell-associated HIV-1 DNA and RNA. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54:902–911.■■ This manuscript describes the development of accurate assays to measure total HIV-1 DNA and RNA; the use of a cellular gene quantified in parallel controls for cell input and extraction steps and provides an accurate denominator for the cells assayed.

- 53.Riddler SA, Aga E, Bosch RJ, et al. Continued slow decay of the residual plasma viremia level in HIV-1-infected adults receiving long-term antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:556–560.■■ This study describes the decay rate of residual HIV-1 plasma RNA using an improved single copy assay.

- 54.Somsouk M, Dunham RM, Cohen M, et al. The immunologic effects of mesalamine in treated HIV-infected individuals with incomplete CD4+ T cell recovery: a randomized crossover trial. PLoS One 2014; 9:e116306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sizmann D, Glaubitz J, Simon CO, et al. Improved HIV-1 RNA quantitation by COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HIV-1 test, v2.0 using a novel dualtarget approach. J Clin Virol 2010; 49:41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strain MC, Lada SM, Luong T, et al. Highly precise measurement of HIV DNA by droplet digital PCR. PLoS One 2013; 8:e55943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Spiegelaere W, Malatinkova E, Kiselinova M, et al. Touchdown digital polymerase chain reaction for quantification of highly conserved sequences in the HIV-1 genome. Anal Biochem 2013; 439:201–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dilernia DA, Chien JT, Monaco DC, et al. Multiplexed highly-accurate DNA sequencing of closely-related HIV-1 variants using continuous long reads from single molecule, real-time sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43:e129.■■ This manuscript describes continuous long read single genome sequencing of HIV genomes with Pacific Biosciences SMRT technology; a method that may allow an accurate study of near full genome HIV haplotypes.

- 59.Hong F, Spindler J, Musick A, et al. , editor ARt Reduces Cellular HIV RNA but Not the Fraction of Proviruses Transcribing RNA. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2016); 2016 February 22–25, 2016; Boston, MA, USA.■■ This abstract compares the proportion of cells transcribing HIV RNA and the level of HIV RNA expression of infected cells in viremic and successfully treated individuals. It found that the proportion of cells expressing HIV RNA is not significantly different on therapy, but fewer cells on therapy express high levels of HIV RNA.

- 60.Wiegand A, Spindler J, Shao W, et al. , editor Analysis of HIV RNA in Single Cells Reveals Clonal Expansions and Defective Genomes. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2015); 2015 February 23–26, 2015; Seattle, WA, USA.■ This investigation describes a method sequencing single HIV DNA genomes of cells and the mRNA that they express, which allowed the investigation of clonal expansion and the detection of defective genomes expressing mRNA.

- 61.Wagner TA, McLaughlin S, Garg K, et al. HIV latency. Proliferation of cells with HIV integrated into cancer genes contributes to persistent infection. Science 2014; 345:570–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maldarelli F, Wu X, Su L, et al. HIV latency. Specific HIV integration sites are linked to clonal expansion and persistence of infected cells. Science 2014; 345:179–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]