Abstract

Objectives:

Latina/o adolescents are at particular risk for substance use disorders (SUDs) and effective treatments are needed. Some critics indicate that standard evidence-based treatments may not meet the needs of Latina/o adolescents and culturally accommodated treatments are needed; however, few comparative studies have been conducted to test this assumption. This randomized trial was designed to test a standard group-based version of a cognitive-behavioral treatment (S-CBT) against its culturally accommodated equivalent (A-CBT) for a sample of Latina/o adolescents with SUDs.

Methods:

Seventy Latina/o adolescents were randomly assigned to one of two treatment conditions and followed over four posttreatment time points with the last at 12-months. Generalized longitudinal mixed models for count data were conducted to evaluate treatment differences across time for adolescent substance use. The cultural variables ethnic identity, acculturation, and familism were included in the analysis as potential moderators of treatment outcome.

Results:

A significant difference was found at the 12-month follow-up in favor of the culturally accommodated treatment (d = .92, 95% CI [.43, 1.42]) and parental familism moderated treatment outcome (d = .60, 95% CI [.12, 1.08]).

Conclusion:

This is one of the first studies to demonstrate that a culturally accommodated treatment differentially improved outcomes compared to that of its standard equivalent for a sample of Latina/o adolescents with SUDs.

Keywords: Latina/o adolescents, substance abuse treatment, culturally accommodated treatment, randomized trial

Adolescent substance use disorders is a serious public health concern in the United States and effective treatments are needed to address this problem (CASA, 2011; SAMSHA, 2015). Latina/o adolescents are in particular need of efficacious treatments and some research indicates that they experience higher rates of substance use disorders (14%) compared to their White (12.7%) or African American (7%) counterparts (CASA, 2011). The efficacy of empirically supported treatments (ESTs) for substance use and other mental health disorders is predominately derived from studies developed for and conducted with White samples (APA, 2006; Whaley & Davis, 2007). More recent studies have included larger numbers of racial/ethnic minorities but few have analyzed their data to test their efficacy on different cultural groups (Greenbaum et al., 2015; Robbins et al., 2011; Waldron & Turner, 2008) and fewer have attempted to test culturally adapted interventions against their standard counterparts (Huey, Tilley, Jones, & Smith, 2014; Steinka-Fry, Tanner-Smith, Dakof, & Henderson, 2017). To address this concern, the present study compares standard and culturally accommodated versions of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for Latina/o adolescents with substance use disorders to determine any benefit that may be derived from the culturally accommodated adaptation.

Almost 10% or 2.3 million adolescents in the United States between the ages of 12–17 are considered current illicit drug users (i.e., reported use in past month) and about 5% or 1.3 million meet diagnostic criteria for a substance use disorder (SAMSHA, 2015). Unfortunately, only 10% of adolescents who need treatment actually receive it (SAMSHA, 2015) and fewer receive treatments that are evidence-based (NIDA, 2012). For the adolescents who do receive treatment it will most likely be delivered in group or individual formats and provided in outpatient settings (SAMHSA, 2014). A frequent referral source for adolescents to substance abuse treatment is the criminal justice system; in particular, Latina/o youth are more likely to be referred from the justice system and less likely to complete a course of treatment compared to their White counterparts (Alegria, Carson, Goncalves, & Keefe, 2011; Saloner, Carson, & Le Cook, 2014 ; Shillington & Clapp, 2003). Understanding the efficacy of ESTs for substance abuse for Latina/o youth is of great concern, in part, because they belong to one of the largest and fastest growing ethnic minority groups in the U.S at more than 50 million people with a third of the population under the age of 18 (Passel & D’Vera, 2008; Pew, 2011). However, the lack of representation of individuals from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds in studies of ESTs continues to be a barrier to our understanding (APA, 2006; Whaley & Davis, 2007).

A major criticism stemming from the general lack of representation in studies of ESTs is that we cannot assume treatments validated with predominately White samples will meet the needs of individuals from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds (Dumas, Rollock, Prinz, Hops, & Blechman, 1999; Hall, 2001; Lau, 2006; Szapocznik, Lopez, Prado, Schwartz, & Pantin, 2006; Whaley & Davis, 2007). One way researchers have suggested to address this criticism is to evaluate the efficacy of ESTs in studies that directly test a standard EST against its culturally accommodated counterpart (Castro, Barrera, & Holleran Steiker, 2010; Huey & Polo, 2008; Huey et al., 2014; Whaley & Davis, 2007). Such direct comparison studies can assist us in determining if and how racial/ethnic minorities benefit from standard or culturally accommodated versions of ESTs. While there has been theoretical and conceptual proliferation of models for culturally adapting treatments in general (see Bernal & Rodriguez, 2012; Castro et al., 2010) the empirical testing of such models is less prevalent in the literature. For example, a review by Huey and colleagues (2014) identified only three randomized studies (Burrow-Sánchez & Wrona, 2012; McCabe & Yeh, 2009; Szapocznik et al., 1986) that compared standard and culturally adapted versions of treatment with Latina/o youth; in general, results across these studies were similar in finding no differential effects between treatment conditions at posttest. However, a specific framework for the cultural accommodation and testing of substance treatments is needed to further our understanding of the efficacy of these ESTs for racial/ethnic minority youth.

The Cultural Accommodation Model for Substance Abuse Treatment (CAM-SAT; see Burrow-Sánchez, Martinez, Hops, & Wrona, 2011) is a framework for the development and testing of standard versus culturally accommodated versions of treatments. This model is based on an assumption that treatments with more cultural relevance for its participants will lead to greater benefits (Castro et al., 2010; Frankish, Lovatto, & Poureslami, 2007). The CAM-SAT was used in the present study to guide the development and subsequent testing of a standard versus culturally accommodated version of a substance abuse treatment for a sample of Latina/o adolescents. The three variables of acculturation, ethnic identity, and familism were integrated into the culturally accommodated version of the treatment because of their relevance for Latina/o adolescents experiencing substance abuse problems (see Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2011; Castro et al., 2010) and are discussed next.

Acculturation is a germane cultural variable to examine for Latina/o adolescents in relation to substance use and abuse. This construct refers to the extent that racial/ethnic minority individuals adopt the perspectives and behaviors of a dominant group and it has been linked to substance use for Latina/o adolescents (Berry, 2006; Lara, Gamboa, Kahramanian, Morales, & Bautista, 2005; Lawton & Gerdes, 2014). In a number of studies, researchers have found that higher levels of acculturation positively correlate with substance use rates for Latina/o adolescents (De La Rosa, Vega, & Radisch, 2000; Ebin et al., 2001; Vega & Gil, 1998, 1999; Vega, Gil, & Wagner, 1998) whereas others have found a negative correlation (Zamboanga, Schwartz, Jarvis, & Van Tyne, 2009) or no association all (Miller, 2011). Beyond the correlational studies, research is needed to understand the ways acculturation may influence Latina/o adolescents’ response to substance abuse treatment and whether acculturation plays a role in adolescents’ response to standard versus culturally accommodated interventions.

Ethnic identity is a second cultural variable that has relevance for Latina/o adolescents with substance use and abuse problems. Typically, ethnic identity refers to the level of identification that individuals have with their own ethnic group (Marcia, 1980; Phinney & Ong, 2007). For Latina/o adolescents, higher levels of ethnic identity positively correlate with well-being (e.g., self-esteem, coping) and negatively correlate with substance use (Felix-Ortiz & Newcomb, 1995; Phinney & Ong, 2007; Umana-Taylor, 2011). However, some researchers have found that higher levels of ethnic identity may increase the awareness of environmental stressors such as discrimination for Latina/os (Smith & Silva, 2010). What has yet to be determined, however, is the role that ethnic identity plays for Latina/o adolescents receiving treatment for substance use disorders.

Familism is a third salient variable for Latina/o adolescents in the context of substance use and abuse. This construct reflects the impact that family has on the norms, values, and behavior of Latina/o adolescents. Major components of this construct include familial obligations, perceived levels of support, and attachment to family members (Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, & Marin, 1987). In general, Latina/o families reporting higher levels of familism do not condone the use and abuse of substances by its members (Vega, 1990); however, this relation is likely influenced by the quality of parenting. Some researchers have found that more supportive parenting behavior is related to less mental health concerns and substance use for Latina/o adolescents (Castro & Alarcon, 2002; German, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2009; Gonzales, Deardorff, Fromoso, Barr, & Barrera, 2006). In support of this finding, other researchers have found that non-supportive parenting practices, especially ones that lead to parent-child conflict, are related to increased risk for adolescent delinquency and substance use (McQueen, Gertz, & Bray, 2003; Pasch et al., 2006). From a broader perspective, familism is a representation of the influence that Latina/o families have on their adolescents and requires further investigation within the context of treatment. While the review of cultural variables above is brief, it does underscore the relevance they may have for Latina/o adolescents and potential influence in substance abuse treatment (see Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2011; Castro & Alarcon, 2002; Castro et al., 2010).

In the present study, 70 Latina/o adolescents were randomly assigned to one of two group-based treatment conditions: a standard cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) protocol (Kadden et al., 1992; Waldron & Kaminer, 2004) or its culturally accommodated counterpart (Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2011). We tested a group-based intervention because it is one of the most commonly used treatment formats for substance abuse (Engle & Macgowan, 2009; SAMHSA, 2014) and similarly, CBT is one of the most commonly used ESTs for adolescents (Waldron & Kaminer, 2004). Our first hypothesis predicted that a group by time effect for adolescent substance use levels would be found in favor of the culturally accommodated versus standard treatment. The rationale for this hypothesis is that Latina/o adolescents will respond more favorably to a treatment with higher culturally relevancy compared to one with less (Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2011; Castro et al., 2010; Hall, 2001; Whaley & Davis, 2007). The previous results we reported for the 3-month outcomes did not yield an effect of treatment on substance use levels (see Burrow-Sánchez, Minami, & Hops, 2015). Our second hypothesis predicted that substance use levels for adolescents in both treatment conditions would be moderated by the cultural variables of acculturation, ethnic identity, and familism. Specifically, we anticipated that lower substance use levels would be found when the level of cultural variable (i.e., low versus high) was congruent with the assigned treatment condition (i.e., standard vs. accommodated). This second hypothesis was predicated on the rationale that treatments are more or less culturally relevant for particular subgroups of Latina/o adolescents depending on the individual characteristics of the participants (Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2011; Castro et al., 2010; Frankish et al., 2007). The previous results we reported for the 3-month outcomes did yield moderation effects for adolescent parental familism and ethnic identity (see Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2015).

Method

Participant Demographics and Referral

Adolescent inclusion criteria in this study were: ages 13–18 years, having parental/adolescent consent/assent, meeting DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) diagnostic criteria for alcohol or drug abuse/dependence and self-identified as Latina/o or Hispanic. Adolescents exclusion criteria were: outside the 13–18 age range, mono-lingual Spanish speakers, lacking parental consent, not willing to provide assent, in need of a higher level of care than provided by the study, recipients of substance abuse treatment within 90 days of referral, or not identified as Latina/o or Hispanic. The 70 recruited Latina/o adolescents had a mean age of 15.2, were largely male (90%), and born in the United States (61.4%). Parents of the adolescents in the sample were mostly born in Mexico (74.3% = mothers and 81.4% = fathers), in their early 40’s (M = 41.3, SD = 6.29), and had yearly household incomes of $25,000 or less (75.7%). The majority of parents that completed measures at the pretreatment assessment were mothers (81.4%) followed by smaller percentages of both parents (11.4%) and fathers (7.1%). (See Table 1 for more participant demographics). All the procedures employed in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the university of the first author. The majority of adolescents in the study were recruited or referred through probation officers (63%) or case managers (33%) from the juvenile justice system in a mid-sized Mountain West city in the United States; the remaining adolescents (4%) were recruited or referred from parents or treatment providers. A majority of adolescents (74%) were mandated to treatment at the time of referral.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Baseline Variables

| Variable | S-CBT (n = 36) | A-CBT (n = 34) |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Demographics | ||

| Age | 15.31 (1.28) | 15.09 (1.19) |

| Grade | 9.72 (1.32) | 9.71 (1.27) |

| Male | 88.9% | 91.2% |

| Referred By: | ||

| Probation Officer | 72% | 53% |

| Case Manager | 25% | 41% |

| Othera | 3% | 6% |

| Mandated to Treatment: | ||

| Yes | 72% | 76% |

| Language Spoken at Home: | ||

| Spanish | 58%* | 85% |

| English | 28%* | 9% |

| Both | 14% | 6% |

| Birth Country: | ||

| U.S. | 69% | 53% |

| Mexico | 28% | 44% |

| Otherb | 3% | 3% |

| Annual Family Income: | ||

| 25,000 or less | 72% | 71% |

| 25,000 – 45,000 | 20% | 23% |

| 45,000 or more | 8% | 6% |

| Did not answer | 0% | 3% |

| DSM Diagnosis at Baseline | ||

| Substance Abusec | 44%* | 71% |

| Alcohol | 3% | -- |

| Marijuana | 31% | 50% |

| Two or more drugsd | 11% | 21% |

| Substance Dependencee | 56%* | 29% |

| Alcohol | 3% | 3% |

| Marijuana | 36% | 24% |

| 2 or more drugsd | 17% | 3% |

| Drug Use at Baselinef | ||

| Alcohol | 4.17 (7.39) | 4.50 (8.35) |

| Marijuana | 22.03 (23.65) | 18.35 (22.57) |

| Tobacco | 13.61 (27.28) | 7.26 (17.85) |

| Otherg | 1.16 (0.17) | 1.61 (0.19) |

| Cultural Variables at Baseline Acculturation | ||

| MOS | 3.30 (0.61) | 3.49 (0.77) |

| AOS | 3.40 (0.46) | 3.39 (0.53) |

| Ethnic Identity | ||

| COM | 3.93 (0.97) | 3.89 (1.13) |

| EXP | 3.04 (0.96) | 2.66 (0.90) |

| Familism | ||

| Adolescent | 2.97 (0.42) | 3.06 (0.44) |

| Parent | 3.60 (0.68) | 3.68 (0.77) |

Note. Cell entries are either means (SD) or a percentage of the subsample indicated. S-CBT = Standard Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment condition; A-CBT = Accommodated Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment condition.

Other = parent or treatment provider,

Other = South American country,

Primary abuse diagnosis,

Abuse or dependence diagnosis is for two or more drugs - most commonly alcohol and marijuana in this sample,

Primary dependence diagnosis;

Mean (SD) number of days used in past 90,

Other = hallucinogens, cocaine, opiates, inhalants, prescription meds, etc.; .

Acculturation measured by Acculturation Rating Scale 9or Mexican Americans II: MOS = Mexioan Orientated Scale, AOS = Anglo OrienteO 0cale; Ethnic Identity measured by Multi Ethnic Identity Measufe: COM = commitment subscale, EXP = exploration subscale; Familism measured by Familism Scale.

Indicates significant different (a<.05, Chi-square test) between the two values in the corresponding columns.

Study Flow

At the beginning of each treatment round, participants were randomized into one of two study conditions: standard or accommodated cognitive behavioral treatment. In order to balance participants in each study arm a restricted randomization technique was employed (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). More specifically, 10 participants were randomized and then assigned to one of the two treatment conditions; this process was repeated until the two groups for each treatment round were filled. The principal investigator generated the random number sequences by using the Research Randomizer (Urbaniak & Plous, 2013) available on the internet and provided them to the program coordinator who then assigned participants to treatment conditions. Participants were assigned to conditions after they completed the pretreatment assessment and were not explicitly informed of the assigned condition. Recruitment, baseline assessments, treatment delivery, and follow-ups were for this study was completed between the years 2010 – 2014.

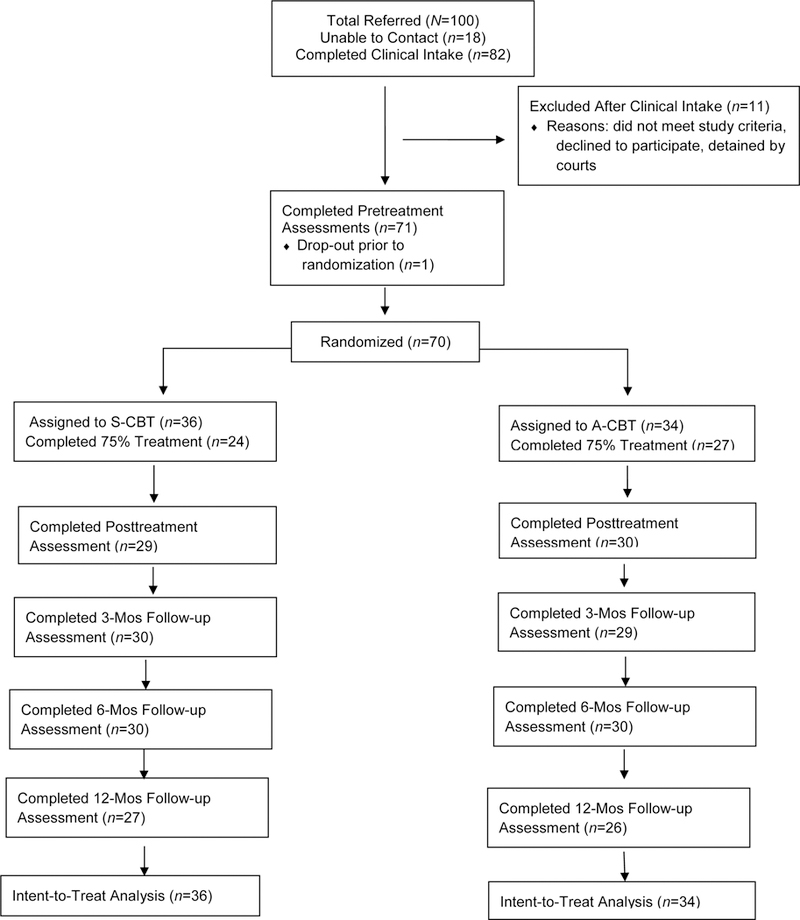

At the beginning of the study one therapist was assigned to each treatment condition by a coin toss (i.e., heads = standard condition and tails = accommodated condition). In order to minimize the potential for therapist effects they were counterbalanced throughout the study by switching therapists with conditions after each treatment round was completed. For example, therapist A was assigned S-CBT and therapist B assigned A-CBT at the beginning of the study then exchanged conditions (i.e., therapist A = A-CBT, therapist B = S-CBT) at the start of the next treatment round. In total, five treatment rounds were conducted over the course of the original study and produced a total of 10 treatment groups. Attendance rates for adolescents in the S-CBT (M = 10.42, SD = 1.14) and A-CBT (M = 10.59, SD = 1.05) conditions were similar. Treatment completion was defined as attending 9 out of a possible 12 (75%) group sessions; a majority of adolescents completed treatment (73%; S-CBT=67%, A-CBT=79%) with no significant differences in completion rates by condition. The majority of adolescents also completed the posttreatment (83%; S-CBT=81%, A-CBT=88%) and follow-up assessments at 3-months (84%; S-CBT=83%, A-CBT=85%), 6-months (86%; S-CBT=83%, A-CBT=88%), and 12-months (76%; S-CBT=75%, A-CBT=76%). Figure 1 is a flowchart for the study across all time points.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for Randomized Clinical Trial

Note. S-CBT = Standard Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment, A-CBT = Accommodated Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment.

Study Measures

All measures in this study were administered by bilingual (English/Spanish) undergraduate and graduate student research assistants (RAs) in the language preference of the participant. The RAs were blind to the participant assignment to treatment condition. Almost all of the adolescents (97%) preferred to complete measures in English and 83% of the parents preferred Spanish; of the measures described below parents only completed the Familism Scale.

Timeline Follow Back (TLFB).

The TLFB (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) is a semi-structured interview that has been used extensively with adolescents (Dennis, Funk, Godley, Godley, & Waldron, 2004; Sobell & Sobell, 2003). It utilizes a calendar format and establishes relevant life markers to help individuals remember their history and patterns of substance use over a specific period of time. The TLFB was used to measure the dependent variable that was the number of days substances (including alcohol; excluding tobacco) were used in the 90-day period prior to each assessment point.

Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II (ARSMA-II).

The ARSMA-II measures acculturation levels in participants of Mexican American descent (Cuéllar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995) by rating their preferences (e.g., “I enjoy reading books in English or Spanish”), attitudes (“I like to identify myself as Anglo American or Mexican”), and behaviors (e.g., “I speak Spanish or English”) from “1 – Not at All” to “5 – Extremely Often or Almost Always” scale. Past research has indicated good reliability and strong construct and discriminant validity with Mexican American samples (Cuéllar et al., 1995). Baseline scores from the 13-item Anglo Oriented Subscale and the 17-item Mexican Oriented Subscale were averaged separately consistent with a bi-dimensional view of acculturation (Berry, 2006; Cuéllar et al., 1995). Means and SDs for the AOS and MOS subscales were 3.40 (.49) and 3.40 (.69), respectively. Internal consistency was α = .66 for AOS and α = .85 for MOS.

The Multi Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM).

The MEIM measures ethnic identity for adolescents (Phinney, 1992); a 12-item modified version of this instrument was administered that has been validated for Latina/o adolescents with substance use disorders (Burrow-Sánchez, 2014). Participants rated their attitudes and behaviors of ethnic identity on a “1 – Disagree” to “5 – Agree” scale. Consistent with Phinney and Ong (2007) the measure was reduced to two 3-item subscales: commitment (i.e., personal affiliation to an ethnic group) and exploration (i.e., behavior related to seeking information about an ethnic group). Means and SDs for the baseline commitment and exploration subscales were 3.91 (1.04) and 2.86 (.94), respectively. Internal consistency was α = .78 for the commitment and α = .65 for the exploration subscales.

Familism Scale (FS).

The FS is a 14-item instrument that measures familial obligations, perceived support, and family members as referents (Sabogal et al., 1987) . This measure was administered to adolescents and parents in the study. Participants rated items from “1 – Very Much in Disagreement” to “5 – Very Much in Agreement.” Baseline scores for the total scale were averaged for adolescents and parents separately. For parents, this measure was completed by mothers (81.4%), both parents (11.4%), and fathers (7.1%). If both parents completed the measure, their individual scores were averaged to produce a single score for the analysis. Means and SDs for the baseline adolescent and parent familism scores were 3.01 (.43) and 3.64 (.72), respectively. Internal consistency for adolescents was α = .73 and α = .85 for parents.

Treatment Conditions and Delivery

Treatment for both conditions was delivered in a group format via 12 weekly 1 ½-hour sessions at a community center. The Standard Cognitive Behavioral Treatment (S-CBT) manual (see Burrow-Sánchez, 2013b) was modeled after the Cognitive-Behavioral Coping Skills Therapy Manual (see Kadden et al., 1992) that was later adapted for adolescents (see Dennis, Godley, et al., 2004; Kaminer, Burleson, & Goldberger, 2002; Waldron, Slesnick, Brody, Turner, & Peterson, 2001). The S-CBT manual was then modified through a cultural accommodation process resulting in a second manual titled Accommodated Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment (A-CBT; see Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2011; Burrow-Sánchez, 2013a). Compared to the S-CBT, aspects of treatment content were modified for the A-CBT manual to increase cultural relevancy for Latina/o adolescents. These modifications included the use of Spanish names in examples, implementation of culturally relevant role-plays (e.g., problem solving a situation that involved racism or discrimination), and providing opportunities to discuss real-life stressors (e.g., translating for a parent). A new module was created for the A-CBT titled Ethnic Identity and Adjustment that was consistent with the principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy; it focused on identity awareness and development for Latina/o adolescents. Parents in the A-CBT condition were offered a Family Introduction Meeting prior to the first group session and then regular (i.e., every third session) phone and mail contact between the therapist and parents was encouraged whereas parents in the S-CBT condition did not receive these modified elements of treatment delivery. Adolescents in both treatment conditions received attendance reminder calls. All modifications made to the A-CBT were designed to be consistent with the theoretical and practical components of cognitive-behavioral therapy (see Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2011).

The two therapists in this study were bilingual (English/Spanish) doctoral students in counseling and school psychology with prior clinical experience working with Latina/o families. They received 20 hours of training in the theoretical and clinical delivery of CBT with adolescents from a licensed psychologist with expertise in this area. During training, therapists were provided with treatment manuals and session-by-session adherence checklists to orient themselves to study materials. During the study, group treatment sessions were videotaped and therapists received weekly supervision by a licensed psychologist. Prior to the supervision meetings, therapists and the supervisor provided independent ratings of the last treatment session video using a seven-item adherence checklist ranging from “1-Not Accomplished” to “7-Completely Accomplished”; ratings were compared in supervision to maintain treatment adherence and prevent therapist drift. The mean supervisor (S-CBT = 5.61 [SD=0.55]) and A-CBT = 5.77 [SD=0.50]) and therapist (S-CBT = 5.46 [SD=0.82]) and A-CBT = 5.56 [SD=0.72]) adherence ratings for sessions 3, 6, and 9 (i.e., 25% of total sessions) indicated that adherence was acceptable in both treatment conditions.

Analytical Plan

The data were cleaned and examined prior to analysis checking for statistical assumptions of the main analysis. The dependent variable (DV) in this study is the total number of days in the past 90 that any drug was used (including alcohol; excluding tobacco) as measured by the TLFB. The DV is a count variable and a generalized linear model approach was used to guide the main analysis. Generalized linear models can account for the dependence between participant scores in repeated measures and estimate parameters for missing data (see Shadish et al., 2002). Specifically, a Poisson model was chosen because it can appropriately model count data (see Atkins, Baldwin, Zheng, Gallop, & Neighbors, 2013; Cox, West, & Aiken, 2009; Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006); however, a prime assumption of this model, rarely met in practice, is the mean and variance of the distribution are the same. Thus, a standard error correction was included in all models to relax the mean-variance assumption (see Coxe, West, & Aiken, 2009; Stroup, 2013). For 18 of the 60 adolescents (30%) who completed the 6-month assessment point there was, on average, an 18-day overlap (M = 18.28, SD = 12.58) with the past 90-day TLFB data collected at the 3-month assessment. This overlap occurred for a portion of the adolescents because there was difficulty in scheduling (e.g., adolescent planned to be out of country for a period of time). For this subset of adolescents, data were collected as close as possible to the 6-month assessment point rather than risk not scheduling them at all. The 18 adolescents were evenly distributed across treatment conditions (S-CBT = 9 and A-CBT = 9) and a Mann-Whitney U test, U(18) = 28.00, p = .297 indicated substance use rates did not significantly differ between groups; this data issue only occurred for the 6-month follow-up due to its three month interval following the prior (i.e., 3-month) assessment point. For the analysis, a weighting procedure was used to correct for the 6-month TLFB data. Specifically, the total days of use for this 90-day period was multiplied by the percent of days that no overlap occurred between the two assessment points.

Missing data.

The attrition rate was generally balanced across conditions but highest (25%) at the 12-month time point (see Figure 1). A concern was that there may be differential attrition at the last study time point due to severity of diagnosis (i.e., dependence versus abuse) or pretreatment level of substance use. To examine the potential for attrition bias due to specific baseline variables, analyses via X2 and Mann Whitney U were conducted. Overall, it was found that attrition at the last study time point was not related to severity of substance use diagnosis X2(1, 17) = .529, p = .467 or pretreatment substance use U(70) = 391.50, p = .419 nor was it related to treatment condition: S-CBT X2(1, 36) = .600, p = .439 and A-CBT X2(1, 34) = .2.14, p = .144 for diagnostic severity or pretreatment substance use S-CBT U(36) = 109.50, p = .661 and A-CBT U(34) = 85.50, p = .452.

Results

Multilevel Generalized Models

Primary model.

A random intercept Poisson model with TLFB as the DV was used as the baseline model. This unconditional model included the terms Time (coded 0, 1, 2, 3, 4) and Quadratic (coded 0, 1, 4, 9, 16) and the model produced significant Time (F[1, 237.4] = 17.17, p < .0001, d = .99, 95% CI [.49, 1.49]) and Quadratic (F[1, 239] = 19.61, p < .0001, d = 1.06, 95% CI [.56, 1.56]) effects. The estimates produced were significant for between-subject (σ2 = 0.27, Wald Z = 3.18, p = .0007) and residual (σ2 = 15.90, Wald Z = 10.77, p < .0001) variances. Next, a conditional random intercept Poisson model was tested that included covariates for Age (grand mean centered) and Diagnosis (0=Substance Abuse, 1=Substance Dependence) as well as terms for Time, Quad, Group (i.e., treatment condition), and Group*Time (i.e., treatment condition by time). A Mann-Whitney U test, U(70) = 571.50, p = .634 indicated that baseline drug use did not differ by treatment condition and was therefore not included as a covariate. This conditional model produced significant Age (F[1, 66.6] = 5.86, p = .018, d = .58, 95% CI [.10, 1.06]), Diagnosis (F[1, 60.94] = 4.17, p = .045, d = .49, 95% CI [.01, .96]), Time (F[1, 241.4] = 9.40, p = .002, d = .73, 95% CI [.25, 1.22]), Quad (F[1, 241.5] = 17.85, p < .0001, d = 1.01, 95% CI [.51, 1.51]), and a Group*Time interaction (F[1, 248.9] = 10.89, p = .0011, d = .79, 95% CI [.30, 1.28]) effects (see Table 1).

Interpretation of two-way interaction.

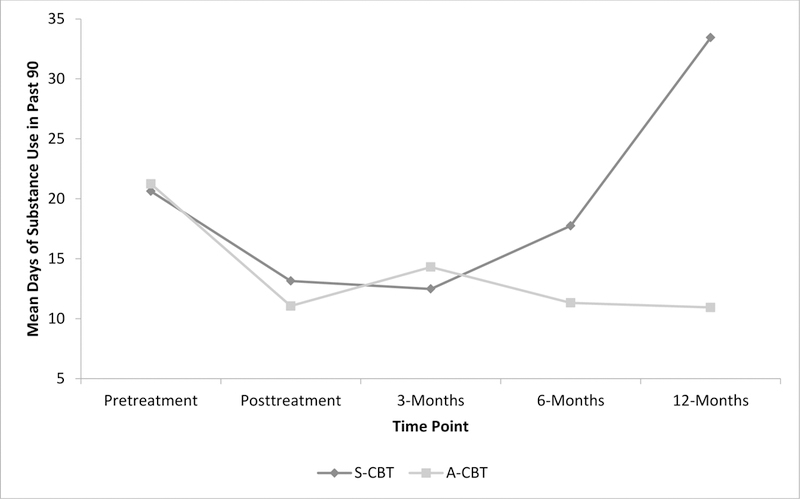

Coxe et al., (2009) suggests that an interaction (i.e., Group*Time) can be interpreted by plotting the trends for each group at different values of the X variable. Regression coefficients for Poisson models, however, represent the predicted logarithm of counts for the DV (Coxe et al., 2009) which are not directly interpretable. For the current study, the coefficients are interpreted as the predicted change in the logarithm of counts for the TLFB variable for a 1-unit change in the predictor. To make the Poisson coefficients interpretable they were exponentiated which places them on the original metric scale of the dependent variable (i.e., counts). Specifically, the exponentiated intercept represents the number of drug use days when other predictors in the model are zero whereas the exponentiated coefficients represent the multiplicative change in DV for a 1-unit change in the predictor (Coxe et al., 2009). The Group*Time interaction was then interpreted by plotting the estimated exponentiated means for each group across the five time points (see Figure 2). In order to further decompose the interaction in Figure 2 least squares means were calculated to determine the between group estimates across time points (see Hoffman, 2015). At the pretreatment (p = 0.95), posttreatment (p = 0.52), and 3-month time points (p = 0.70) the between group estimates were non-significant. The difference between groups appears larger at the 6-month time point although non-significant t([273.6] = 1.58, p = 0.115, d = .38, 95% CI [−.10, .85]). However, significant between group estimates were found t([273.5] = 3.86, p = 0.0001, d = .92, 95% CI [.43, 1.42) at the 12-month time point.

Figure 2.

Plot of Treatment Group by Time Interaction

Note. S-CBT = Standard Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment; A-CBT= Accommodated Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment.

Moderator models.

Four conditional Poisson models were developed to test the cultural moderator variables; specifically, one model for each adolescent variable (i.e., acculturation, ethnic identity, and familism) and one model for the parent familism variable. The general structure of each model included the following terms: Age, Diagnosis, Time, Quad, Group, Moderator Variable (MV), Group by Time, MV by Time, Group by MV, and Group by MV by Time. The cultural moderators were grand mean centered to ease interpretation (see Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006) and coded using the subscale acronym: commitment = COM, exploration = EXP, familism adolescent score = FS_A, familism parent score = FS_P, Mexican oriented scale = MOS, and Anglo oriented scale = AOS. The random intercept parent familism model produced a significant three-way interaction for Group by FS_P by Time (F[1, 259] = 6.33, p = .0125, d = .60, 95% CI [.12, 1.08]) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Random Intercept Poisson Model for Substance Use with Parental Familism Moderator

| Effect | Estimate | SE | Exp (E)a | 95% Confidence Interval for Estimate |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Fixed effects | |||||

| Intercept | 2.75*** | 0.18 | 15.63 | 2.40 | 3.10 |

| Age | 0.15* | 0.07 | 1.17 | 0.02 | 0.29 |

| Dxb | 0.40* | 0.17 | 1.50 | 0.06 | 0.74 |

| Timec | −0.39** | 0.14 | 0.68 | −0.66 | −0.13 |

| Quadd | 0.13* | 0.03 | 1.14 | 0.07 | 0.19 |

| Groupe | 0.15 | 0.21 | 1.16 | −0.26 | 0.56 |

| FS_Pf | −0.26 | 0.20 | 0.78 | −0.66 | 0.15 |

| Group*Time | −0.24** | 0.07 | 0.79 | −0.38 | −0.10 |

| FS_P*Time | 0.18* | 0.08 | 1.19 | 0.02 | 0.34 |

| Group*FS_P | 0.55 | 0.29 | 1.73 | −0.03 | 1.13 |

| Group*FS_P*Time | −0.29* | 0.12 | 0.75 | −0.52 | −0.06 |

| Random effects | |||||

| Intercept variance | 0.21** | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.49 | |

| Residual | 14.77*** | 1.38 | 12.40 | 17.88 | |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.0001

Note. Exponentiation of the estimate

compared to a diagnosis of substance abuse

Time = assessment time-point in study;

Quad = quadratic;

Group = treatment group

FS_P = familism score for parent.

Interpretation of three-way interaction.

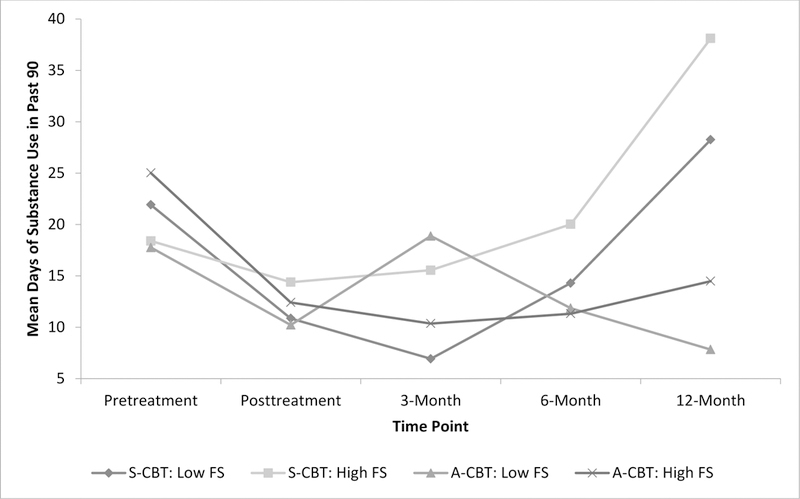

The interaction for the parent familism model was interpreted by dichotomizing the moderator variable into < 0 = low and > 0 = high categories which produced four subgroups: accommodated treatment for low (n = 15) and high (n = 19) parental familism and standard treatment for low (n = 16) and high (n = 20) parental familism. The estimated exponentiated means were plotted for each subgroup across the five time points (see Figure 3). In order to further decompose the interaction in Figure 3 least squares means were calculated for the group estimates across time points (see Hoffman, 2015). The estimates between the four subgroups at pretreatment were not significantly different. A visual inspection of Figure 3 indicates a change in trajectory at the 3-month follow-up for adolescents in the accommodated treatment low parental familism subgroup; however, the estimate for this subgroup was not significantly different (p = 0.18) from that of adolescents in the accommodated treatment high parental familism subgroup. The substance use rates visually appear lowest for youth within the accommodated treatment condition subgroups (i.e., low and high parental familism) at the 12-month time point but the estimates for these two subgroups are not significantly different (p = 0.20). Rather, there is a significant between group difference for youth in the accommodated treatment low familism subgroup compared to those in the standard treatment low familism subgroup t([275.6] = 2.82, p = 0.0052, d = .67, 95% CI [.19, 1.16]). In addition, there is a significant between group difference for youth in the accommodated treatment high parental familism subgroup compared to those in the standard treatment condition high parental familism subgroup t([244] = 2.69, p = 0.0076, d = .64, 95% CI [.16, 1.12]).

Figure 3.

Plot of Parental Familism Moderator

Note. S-CBT = Standard Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment; A-CBT= Accommodated Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment; FS = Familism Scale.

Discussion

The comparative efficacy of standard and culturally accommodated versions of a group-based EST was evaluated over four posttreatment time points with a sample of Latina/o adolescents. Our primary hypothesis was supported by a significant group by time interaction indicating adolescents in the culturally accommodated treatment had lower levels of substance use at 12-months posttreatment compared to adolescents in the standard treatment; this finding suggests that the effects of the cultural accommodation were most pronounced well after treatment ended. The secondary hypothesis was partially supported for one cultural variable indicating that treatment outcome was moderated by parental familism. Findings from this study constitute new contributions to understanding ways ethnic minority adolescents respond to standard and culturally accommodated versions of an EST.

Confirmation of the first hypothesis provides evidence that a culturally accommodated EST can provide differential benefit compared to that of its standard version at 12-months posttreatment. In contrast, these differential treatment effects were not observed at earlier follow-up time points and this is consistent with other direct comparison studies that have brief follow-up time periods (see Burrow-Sánchez & Wrona, 2012; Huey & Pan, 2006; Lee et al., 2013; McCabe & Yeh, 2009) and the overall meta-analytic research in this area (see Huey et al., 2014; Robles, Maynard, Salas-Wright, & Todic, 2016; Steinka-Fry et al., 2017). The lack of differential treatment effects found in the aforementioned studies may be due to comparing active treatment conditions that were too similar or study follow-up periods that were too brief (Carroll & Onkin, 2005; Shadish et al., 2002). However, our findings at the 12-month time point indicate that the treatment conditions were distinct enough to produce a differential effect but only after more time had passed since treatment termination.

The primary results raise two important points for consideration. First, the significant differential treatment effects observed at the most distal posttreatment time period raise the issue of why delayed treatment effects were discovered after non-significant effects were found at posttreatment. Second, the differential effects seen in the relatively flat trend in the accommodated treatment (see Figure 2) across the four posttreatment time points compared to the steadily increasing trajectory from the 6- to 12-month assessment for the standard treatment raises a question about how to explain delayed treatment effects for a subset of Latina/o youth. To address the first issue, evidence suggests in some studies that the emergence of treatment effects for cognitive-behavioral interventions can be greater at more distal posttreatment time points; in particular, such delayed effects have been observed in adolescent (Liddle et al., 2001; Waldron et al., 2001) and adult (Carroll et al., 1994; Epstein, Hawkins, Covi, Umbricht, & Preston, 2003) substance abuse treatment studies. Carroll and colleagues (2005; 1994) argue that delayed effects may occur because participants receive a variety of nonspecific interventions (e.g., attention from study staff, weekly therapy meetings) during the active phase of treatment studies that produce therapeutic benefit but are difficult to separate from the specific effects of treatment. The decrease in exposure to nonspecific interventions that participants experience at the end of treatment, however, may provide the circumstances required for the emergence of durable treatment specific effects that are observed at more distal time points.

The second issue we address is why Latina/o adolescents in the culturally accommodated condition reported significantly lower substance use levels at 12-months posttreatment compared to their counterparts in the standard condition. The modifications made to the culturally accommodated condition, as described earlier in this paper, were based on the assumption that a more culturally relevant treatment would produce better outcomes for Latina/o adolescents compared to one with less relevancy (Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2011; Castro et al., 2010; Hall, 2001; Whaley & Davis, 2007). In prior work, we found that Latina/o adolescents’ experience better substance use outcomes when their cultural characteristics are congruent with treatment assignment (see Burrow-Sánchez & Wrona, 2012; Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2015). Thus, the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral treatments may depend, in part, on the cultural relevancy or congruency it has for Latina/o adolescents.

In partial support of the second hypothesis, the level of parental familism moderated treatment outcome and these findings were consistent with results from our prior work (see Burrow-Sánchez & Wrona, 2012; Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2015). The analysis of a cultural moderator in the current study, however, indicates that subgroups of adolescents experienced outcomes across time that were influenced by an interaction between levels of parental familism and treatment condition. Specifically, adolescents whose parents endorsed lower levels of familism in the accommodated treatment reported significantly lower substance use levels at 12-months compared to their low parental familism counterparts in in the standard condition. On the other hand, adolescents whose parents endorsed higher levels of familism in the accommodated treatment reported significantly lower substance use levels at 12-months compared to their high parental familism counterparts in the standard condition. Taken together, these results suggest that adolescents in the low and high familism subgroups assigned to the accommodated treatment displayed significantly lower substance use scores at 12-months compared to their respective counterparts in the standard treatment condition. Due to the fact that the low and high familism subgroups were not significantly different within each treatment condition we could not determine if parent-adolescent congruency on the cultural variable of familism provided benefit beyond that of assignment to the accommodated or standard treatment condition. Overall, we interpret these results to suggest that parental familism is a relevant cultural variable when examining substance abuse treatment outcomes for Latina/o adolescents and is an important area for further study but any other conclusions are beyond the scope of our findings.

Findings from the current study have a number of implications for research and practice and are considered next. First, some ESTs have demonstrated efficacy for ethnic minority adolescents but few have been directly tested against a culturally accommodated equivalent (see Huey et al., 2014; Steinka-Fry et al., 2017) and the few direct comparison studies that have been conducted report only short-term outcomes. We argue that direct comparison studies are needed to demonstrate the potential benefit from culturally accommodated treatments compared to their standard counterparts and accumulating evidence suggest that treatment effects may take time to develop (Carroll et al., 1994; Patterson, Forgatch, & DeGarmo, 2010; Waldron & Kaminer, 2004). Thus, we suggest that researchers include longer-term posttreatment follow-ups in the design and implementation of future studies in order to test the hypothesis that some treatments may have delayed effects. A second important implication is that relevant cultural variables, such as parental familism or ethnic identity, should not be overlooked in either research or clinical settings for Latina/o youth. Specifically, the influence that cultural variables have on treatment outcome may change across time. For example, in prior studies (see Burrow-Sánchez & Wrona, 2012; Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2015) we found that ethnic identity moderated outcome at 3-months posttreatment but results from the current paper did not support those findings at 12-months posttreatment. One reason for this difference may be that the delayed effect of treatment was not observed until the longer-term follow-up time point; however, the inclusion of cultural variables for Latina/o youth in research or clinical assessments can provide information about the ways cultural characteristics moderate treatment outcome at different time points. We suggest that researchers look beyond group by time interactions when assessing treatment efficacy for Latina/o adolescents by examining the salience of cultural variables.

Similar to all research the current study has limitations that we address next. First, the majority of adolescents in this study were male, juvenile justice involved, and of Mexican American descent. We suggest that future research include more female adolescents and youth from a wider range of Latina/o subgroups (e.g., Puerto Rican, Cuban). Increasing the proportion of Latina females and Latina/o youth from different subgroups will assist in understanding the generalizability of the results found in the current study. Prior research, however, has indicated that adolescent participants recruited from juvenile justice are more likely to be male (see Waldron & Turner, 2008). Second, two subscales (i.e., AOS of the ARSMA and commitment of the MEIM) had less than optimal internal consistencies and were measurement limitations in the current study. In the design of future studies, we suggest that researchers consider the inclusion of more than one measure of a cultural construct to further assess the psychometrics of such measures with Latina/o youth samples. Third, the sample size for the current study was modest and therefore may have limited overall statistical power, although some suggest that 30 participants per treatment condition provides a reasonable level of statistical power (see Huey et al., 2014). We do, however, recommend that researchers of future treatment studies recruit larger numbers of ethnic minority adolescents to ensure statistical power is not an issue. One suggestion to increase recruitment and retention in future studies is to test interventions that have greater cultural relevance for ethnic minority youth in general, and Latina/o youth, in particular (Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2011).

The study described in this article was part of a larger set of studies focused on the development and testing of a culturally accommodated EST against its standard counterpart with a sample of Latina/o adolescents with substance use disorders. The cultural accommodation model for substance abuse treatment (CAM-SAT; Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2011) guided the development of the culturally accommodated treatment. A pilot study was conducted to test feasibility and initial efficacy of the accommodated treatment against its standard counterpart (Burrow-Sánchez & Wrona, 2012) and then methods from the pilot study were used in a larger randomized trial for which the posttreatment and 3-month outcomes were reported (Burrow-Sánchez et al., 2015). This study is one of first to utilize a comparative research design for adolescent substance abuse treatment and report outcomes across four posttreatment time points. We recommend that the type of comparative research design employed in the current study be replicated with additional samples of ethnic minority youth.

Table 2.

Random Intercept Poisson Model for Substance Use

| Effect | Estimate | SE | Exp (E)a | 95% Confidence Interval for Estimate |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Fixed effects | |||||

| Intercept | 2.82*** | 0.17 | 16.80 | 2.48 | 3.17 |

| Age | 0.16** | 0.07 | 1.17 | 0.03 | 0.29 |

| Dxb | 0.33* | 0.16 | 1.39 | 0.007 | 0.66 |

| Timec | −0.42** | 0.14 | 0.66 | −0.69 | −0.15 |

| Quadd | 0.14*** | 0.03 | 1.15 | 0.07 | 0.20 |

| Groupe | 0.14 | 0.20 | 1.15 | −0.26 | 0.54 |

| Group*Time | −0.24** | 0.07 | 0.79 | −0.38 | −0.10 |

| Random effects | |||||

| Intercept variance | 0.19** | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.46 | |

| Residual | 15.18*** | 1.41 | 12.76 | 18.36 | |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.0001

Note. Exponentiation of the estimate;

compared to a diagnosis of substance abuse;

Time = assessment time-point in study;

Quad = quadratic;

Group = treatment group.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number K23DA019914 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse awarded to the first author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alegria M, Carson NJ, Goncalves M, & Keefe K (2011). Disparities in treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring disorders for ethnic/racial minority youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(1), 22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Text Revision (4th ed). Washington, D.C.: Author. [Google Scholar]

- APA. (2006). Presidential task force on evidence-based practice. American Psychologist, 61, 271–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Baldwin SA, Zheng C, Gallop RJ, & Neighbors C (2013). A tutorial on count regression and zero-altered count models for longitudinal substance use data. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(1), 166–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, & Rodriguez MMD (2012). Cultural adaptations: Tools for evidence-based practice with diverse populations. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW (2006). Acculturation: A conceptual overview In Bornstein MH & Cite LR (Eds.), Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships: Measurement and Development (pp. 13–30). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Burrow-Sánchez, Martinez CR, Hops H, & Wrona M (2011). Cultural accommodation of substance abuse treatment for Latino adolescents. J Ethn Subst Abuse, 10(3), 202–225. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2011.600194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow-Sánchez, & Wrona M. (2012). Comparing culturally accommodated versus standard group CBT for Latino adolescents with substance use disorders: a pilot study. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol, 18(4), 373–383. doi: 10.1037/a0029439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow-Sánchez JJ (2013a). A-CBT: Cognitive-behavioral treatment for adolescent substance use disorders: Culturally accommodated version (Unpublished manual). University of Utah; Salt Lake City, UT. [Google Scholar]

- Burrow-Sánchez JJ (2013b). S-CBT: Cognitive-behavioral treatment for adolescent substance use disorders: Standard version (Unpublished manual). University of Utah; Salt Lake City, UT. [Google Scholar]

- Burrow-Sánchez JJ (2014). Measuring ethnic identity in Latino adolescents with substance use disorders. Subst Use Misuse, 49(8), 982–986. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.794839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow-Sánchez JJ, Minami T, & Hops H (2015). Cultural Accommodation of Group Substance Abuse Treatment for Latino Adolescents: Results of an RCT. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Onkin LS (2005). Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry(162), 1452–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, Gordon LT, Wirtz PW, & Gawin F (1994). One-year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence. Delayed emergence of psycholotherapy effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 51(12), 989–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASA. (2011). Adolescent substance use: America’s #1 public health problem. Retrieved from New York, NY: https://www.centeronaddiction.org/download/file/fid/850 [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, & Alarcon EH (2002). Integrating cultural variables into drug abuse prevention and treatment with racial/ethnic minorities. Journal of Drug Issues, 32, 783–810. [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera MJ, & Holleran Steiker LK (2010). Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 213–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox S, West SG, & Aiken LS (2009). The analysis of count data: A gentle introduction to Poisson regression and its alternatives. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 121–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxe S, West SG, & Aiken L (2009). The analysis of count data: A gentle introduction to Poisson regression and its alternatives. Journal of Personality Assessment, 31(2), 121–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, & Maldonado R (1995). Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans II: A revision fo the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 17(3), 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa M, Vega R, & Radisch MA (2000). The role of acculturation in the substance abuse behavior of African-American and Latino adolescents: Advances, issues, and recommendations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 32(1), 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Funk R, Godley SH, Godley MD, & Waldron HB (2004). Cross-validation of the alchohol and cannabis use measures in the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) and Timeline Followback (TLFB; Form 90) among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Addiction, 99(2), 120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, … Funk R. (2004). The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27, 197–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Rollock D, Prinz RJ, Hops H, & Blechman EA (1999). Cultural sensitivity: Problems and solutions in applied and preventive intervention. Applied & Preventive Psychology, 8, 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Ebin VJ, Sneed CD, Morisky DE, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Magnusson AM, & Malotte CK (2001). Acculturaion and the interrelationships between problem and helath-promoting behaviors among Latino adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 28, 62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle B, & Macgowan MJ (2009). A critical review of adolescent substance abuse group treatments. J Evid Based Soc Work, 6(3), 217–243. doi: 10.1080/15433710802686971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Hawkins WE, Covi L, Umbricht A, & Preston KL (2003). Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy Plus Contingency Management for Cocaine Use: Findings During Treatment and Across 12-Month Follow-Up. Psychology of addictive behaviors : journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 17(1), 73–82. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz M, & Newcomb MD (1995). Cultural identity and drug use among Latino and Latina adolescents In Botvin GJ, Schinke SP, & Orlandi MA (Eds.), Drug abuse prevention with multiethnic youth (pp. 147–165). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Frankish CJ, Lovatto CY, & Poureslami I (2007). Models, theories, and principles of health promotion In Kline MV & Huff RM (Eds.), Health promotion in multicultural popluations: A handbook for practitioners and students (2nd ed). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- German M, Gonzales NA, & Dumka L (2009). Familism values as a protective factor for Mexican-origin adolescents exposed to deviant peers. Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(1), 16–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Deardorff J, Fromoso D, Barr A, & Barrera M (2006). Family mediators of the relation between acculturation and adolescent mental health. Family Relations, 55, 318–330. [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum PE, Wang W, Henderson CE, Kan L, Hall K, Dakof GA, & Liddle HA (2015). Gender and ethnicity as moderators: Integrative data analysis of multidimensional family therapy randomized clinical trials. J Fam Psychol, 29(6), 919–930. doi: 10.1037/fam0000127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN (2001). Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities: Empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 502–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, & Gibbons RD (2006). Longitudinal Data Analysis. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L (2015). Longitudinal Analysis: Modeling within-person fluctuation and change. New York, NY: Routlede. [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, & Pan D (2006). Culture responsive one session treatment for phobic asian americans: A pilot study. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43(4), 549–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, & Polo AJ (2008). Evidence-based psychological treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 262–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Tilley JL, Jones EO, & Smith C (2014). The contribution of cultural competence to evidence-based care for ethnically diverse popluations. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 305–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadden RM, Carroll K, Donovan D, Cooney N, Monti P, Abrams D, … Hester R. (Eds.). (1992). Cognitive-behavioral coping skills therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence (Vol. 3). Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer Y, Burleson JA, & Goldberger R (2002). Cognitive-behavioral coping skills and psychoeducation therapies for adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190(11), 737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, & Bautista DEH (2005). Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. annual Review of Public Health, 26, 367–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A (2006). Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(4), 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton KE, & Gerdes AC (2014). Acculturation and Latino adolescent mental health: Integration of individual, environmental, and family influences Clinical Child and Family Psychological Review, on-line prepublication copy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Lopez SR, Colby SM, Rohsenow D, Hernandez L, Borrelli B, & Caetana R (2013). Culturally adapted motivational interviewng for Latino heavy drinkers: Results form a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Ethnicity and Substance Abuse, 12(4), 356–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Parker K, Diamond GS, Barrett K, & Tejeda M (2001). Multidimensional family therapy for adolescent drug abuse: results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 27(4), 651–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia J (1980). Identity in Adolescence In Adelson J (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 159–187). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe K, & Yeh M (2009). Parent-child interaction therapy for Mexican Americans: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38(5), 753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Gertz JG, & Bray JH (2003). Acculturation, substance use, and deviant behavior: Examining separation and family conflict as mediators. Child Development, 74, 1737–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller HV (2011). Acculturation, social context, and drug use: Findings from a sample of Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- NIDA. (2012). Report of the adoption of NIDAs evidence-based treatments in real world settings workgroup. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/evidence-based_treatments_in_real_world_settings_workgroup_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pasch LA, Deardorff J, Tschann JM, Flores E, Pennila C, & Pantoja P (2006). Acculturation, parent-adolescent conflict, and adolescent adjustment in Mexican American families. Family Processes, 45, 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, & D’Vera C (2008). U.S. Population Projections: 2005–2050. Retrieved from www.pewhispanic.org [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Forgatch MS, & DeGarmo DS (2010). Cascading effects following intervention. Development and Psychopathology, 22(4), 949–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew. (2011). Pew Research Hispanic Center Tabulations of the 2011 American Community Survey. Retrieved from www.pewhispanic.org [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1992). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7(2), 156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins MS, Feaster DJ, Horigian VE, Rohrbaugh M, Shoham V, Bachrach K, … Szapocznik J. (2011). Brief strategic family therapy versus treatment as usual: results of a multisite randomized trial for substance using adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol, 79(6), 713–727. doi: 10.1037/a0025477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles EH, Maynard BR, Salas-Wright CP, & Todic J (2016). Culturally adapted substance use interventions for Latino adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, & Marin BV (1987). Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9, 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, Carson N, & Le Cook B (2014. ). Explaining racial/ethnic differences in adolescent substance abuse treatment completion in the United States: A decomposition analysis. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 54, 646–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2014). 2014 State Profile - United States: National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS). Retrieved from https://wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/dasis2/nssats.htm

- SAMSHA. (2015). Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Retrieved from Rockville, MD: http://www.samsha.gov/data

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, & Campbell DT (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. [Google Scholar]

- Shillington AM, & Clapp JD (2003). Adolescents in public substance abuse treatment programs: The impacts of sex and race on referrals and outcomes. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse, 12, 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, & Silva L (2010). Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 42–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB (1992). Timeline follow-back. In Litten R & Allen J (Eds.), Measuring alcohol consumption (pp. 41–72). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB (Eds.). (2003). Alcohol consumption measures (2nd ed). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- Steinka-Fry KT, Tanner-Smith EE, Dakof GA, & Henderson C (2017). Culturally sensitive substance use treatment for racial/ethnic minority youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 75, 22–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup WW (2013). Generalized Linear Mixed Models: Modern Concepts, Methods and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Lopez B, Prado G, Schwartz SJ, & Pantin H (2006). Outpatient drug abuse treatment for Hispanic adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 84, 54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Rio A, Perez-Vidal A, Kurtines W, Hervis O, & Santisteban D (1986). Bicultural effectiveness training (BET): An experimental test of an intervention modality for families experiencing intergenerational/interculutral conflict. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 8, 303–330. [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ (2011). Ethnic identity In Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, & Vignoles VL (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 791–810). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniak GC, & Plous S (2013). Research Randomizer (Version 4.0). Retrieved from http://www.randomizer.org/

- Vega WA (1990). Hispanic families in the 1980’s: A decade of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, & Gil AG (1998). Drug Use and Ethnicity in Early Adolescence. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, & Gil AG (1999). A model for explaining drug use behavior among Hispanic adolescents In Rosa MDL, Segal B, & Lopez R (Eds.), Conducting Drug Abuse Research with Minority Populations: Advances and Issues (pp. 57–74): The Haworth Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil AG, & Wagner E (1998). Cultural adjustment and Hispanic adolescent drug use In Vega WA & Gil AG (Eds.), Drug Use and Ethnicity in Early Adolescence (pp. 125–148). New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, & Kaminer Y (2004). On the learning curve: The emerging evidence supporting cognitive-behavioral therapies for adolescent substance abuse. Addiction, 99, 93–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, Slesnick N, Brody JL, Turner CW, & Peterson TR (2001). Treatment outcomes for adolescent substance abuse at 4 month and 7 month assessments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 802–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, & Turner CW (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 238–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL, & Davis KE (2007). Cultural competence and evidence-based practice in mental health services. American Psychologist, 62(6), 563–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Jarvis LH, & Van Tyne K (2009). Acculturation and substance use among Hispanic early adolescents: Investigating the mediating role of acculturative stress and self-esteem. Journal of Primary Prevention, 30, 315–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]