Abstract

Autoimmune diseases are characterized by impaired immune tolerance towards self-antigens, leading to enhanced immunity to self by dysfunctional B cells and/or T cells. The activation of these cells is controlled by non-receptor tyrosine kinases (NRTKs), which are critical mediators of antigen receptor and cytokine receptor signaling pathways. NRTKs transduce, amplify and sustain activating signals that contribute to autoimmunity, and are counter-regulated by protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs). The function of and interaction between NRTKs and PTPs during the development of autoimmunity could be key points of therapeutic interference against autoimmune diseases. In this review, we summarize the current state of knowledge of the functions of NRTKs and PTPs involved in B cell receptor (BCR), T cell receptor (TCR), and cytokine receptor signaling pathways that contribute to autoimmunity, and discuss their targeting for therapeutic approaches against autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: Non-receptor tyrosine kinase, Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase, Kinase Inhibitors, Effector T cells, Autoantibodies, Autoimmunity

Introduction

The mechanism by which the immune system is able to maintain a constant balance between tolerance and immunity is critical to understanding the etiology of autoimmunity (Goodnow, 1996). Under normal immune homeostasis, antigen-specific B and T lymphocytes are able to distinguish between foreign and self-antigens, and during an immune response to foreign antigen, receive activation signals that lead to either a robust immune response to protect against foreign pathogens, or a tolerogenic signal that dampens the immune response against self (Liston, et al., 2008). During the development of autoimmunity, there is an imbalance and self-tolerance is lost, resulting in auto-reactive lymphocytes (autoantibody-producing B cells and/or self-reactive T cells) that recognize self-antigens and mount an effector immune response that leads to immunopathology. Lymphocyte antigen receptors, including both the B cell receptor (BCR) and the T cell receptor (TCR), use similar signal transduction pathways for activating their downstream signaling, and are important in regulating lymphocyte activation. Furthermore, cytokine receptors are also important in regulating lymphocyte activation and function. Dysregulated cell signaling has therefore emerged as a major potential inducer of autoimmunity. BCR, TCR or cytokine receptor engagement results in the initiation of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation, which is regulated in concert by a number of tyrosine kinases (TKs) and protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) (Baird, et al., 1999; D. J. Rawlings, et al., 2017; Weiss & Littman, 1994). Unlike the receptor tyrosine kinases that present on the cell surface and sense ligands in the environment, non-receptor tyrosine kinases (NRTKs) reside in the cytoplasmic compartment and regulate the cells through modulating the intracellular signaling. NRTKs and PTPs are critical regulators of cellular signaling and are tightly controlled to regulate B and T cell development, activation, and effector functions (Andreotti, et al., 2010; Hubbard & Till, 2000; Mustelin, et al., 2005). This is underscored not only by the fact that many NRTKs have been identified as oncogenes, but also that dysfunctional kinase signaling is associated with malignant tumor growth (Gocek, et al., 2014; Gomez-Puerta & Mocsai, 2013). Given their prominent roles in controlling B and T cell development and activation, NRTKs were some of the first factors identified as regulators of the development of autoimmune disease (e.g. (Hibbs, et al., 1995; Jansson & Holmdahl, 1993; Macchi, et al., 1995)). In this review, we summarize the literature on the role of different NRTKs and PTPs implicated in a number of autoimmune diseases: multiple sclerosis (MS), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and type 1 diabetes (T1D). We also address the therapeutic application and implication of NRTK inhibitors and phosphatases in autoimmunity.

2. Non-receptor tyrosine kinases and protein tyrosine phosphatases

Protein tyrosine kinases are important regulators of signal transduction, and understanding how their activities impact B and T lymphocyte activation and function will provide insight not only into autoimmune diseases, but also provide a better understanding of cancers and inflammatory disorders (Acton, 2013; Gocek, et al., 2014). Protein tyrosine kinases are enzymes that covalently modify the hydroxyl groups of tyrosine residues through the transfer of the γ-phosphate from ATP onto protein substrates (D’Aura Swanson, et al., 2009). The resulting phosphorylation acts as a form of cellular communication by activating different signaling processes that lead to changes in cell activation and development, proliferation, differentiation, and survival (Hubbard & Till, 2000). Two classes of protein tyrosine kinases are responsible for these signaling cascades: receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and non-receptor tyrosine kinases (NRTKs). RTKs are glycoproteins that consist of an extracellular ligand sensing domain, a transmembrane domain, and intracellular domains that contain the kinase core (Gomez-Puerta & Mocsai, 2013). Typical RTKs include receptors for growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or insulin. Upon the transduction of an extracellular signal, RTKs can either autophosphorylate the intracellular tyrosine residues located on their own receptor, a neighboring receptor, or phosphorylate substrate proteins, creating binding sites for downstream signaling molecules (D’Aura Swanson, et al., 2009). By contrast, NRTKs lack both an extracellular and transmembrane domain, and most reside in the cytoplasm of cells, including in immune cells. In addition to their kinase domain, all nine families of NRTKs share homologous Src homology 2 (SH2) and 3 (SH3) protein-protein binding domains. (Gocek, et al., 2014; Hubbard & Till, 2000; Tsygankov, 2003). The SH2 domains are responsible for binding phosphotyrosines on proteins while SH3 domains bind to proline-rich regions in proteins. Both of these domains function in signal transduction by interacting with their target proteins and are thought to negatively regulate kinase activity (Hubbard & Till, 2000; Muller & Knapp, 2009; Pawson & Gish, 1992; Schlessinger, 1994). NRTK are separated into families, categorized by the prototypical members Src, Tec, Abl, Syk, Csk, and Jak (W. C. Yang, et al., 2000) (Fig. 1A).

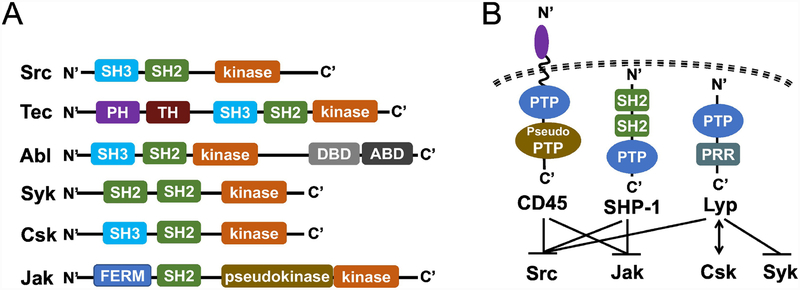

Figure 1: Schematic of the structure of NRTKs and PTPs with known roles in autoimmunity.

(A) Structure of representative NRTKs with a known role in autoimmunity. SH2, Src homology 2 domain; SH3, Src homology 3 domain; PH, Pleckstrin homology domain; TH, Tec homology domain; DBD, DNA binding domain; ABD, actin binding domain; FERM, Four-point-one, Ezrin, Radixin, Moesin domain; pseudokinase, a kinase-like structure that does not have enzymatic activity.

(B) Structure of PTPs known to regulate NRTKs in (A). Schematic representation of the PTPs with a known role in regulating the NRTKs discussed in (A). The receptor-like PTP CD45 and the non-transmembrane PTPs SHP-1 and Lyp (PTPN22) contain various functional domains. CD45 contains a membrane proximal PTP domain that is catalytically active and a membrane-distal PTP domain (pseudo PTP) that has residual activity. CD45 and SHP-1 are known to negative regulate Src and JAK family NRTKs, and Lyp can interact with Csk to down regulate Src and Syk signaling activity. PTP, protein tyrosine phosphatase; PRR, proline-rich region.

NRTKs are regulated by protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), which dephosphorylate protein targets and counterbalance the activity of protein kinases. As such, PTPs are critical in regulating tyrosine phosphorylation and signal transduction (Mustelin, et al., 2005; Oetken, et al., 1992). These PTPs carry a functionally conserved PTPase domain that has a highly conserved signature motif (H/V)C(X)5R(S/T), which employs the catalytic function to hydrolyze phosphate from the tyrosine residues of their substrates (Z. Y. Zhang, 2002). The classical PTPs can be categorized by their subcellular localization as membrane (receptor-like) PTPs, such as CD45, or cytoplasmic (non-transmembrane) PTPs, such as lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase (Lyp) (Tonks, 2006). CD45 is expressed on all bone marrow derived immune cells, and is an important regulator of T and B cell activation, in part, through its role in regulating Src family NRTK tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 1B and Fig. 2A) (Irie-Sasaki, et al., 2001). Lyp is a canonical PTP that is also expressed in bone marrow derived immune cells and plays a key role in regulating TCR signaling (Fig. 1B and Fig. 2A). PTPN22, the human gene encoding Lyp, binds to multiple intracellular signaling substrates proximal to the TCR: Lck, Zap-70, Csk, and Vav to negatively regulate and dampen TCR signals (Fig. 2A). Of the many Lyp ligands that have been proposed, the interaction between Lyp and c-Src tyrosine kinase (Csk) has been of focus in the context of type I diabetes, RA and SLE (Begovich, et al., 2004; Manjarrez-Orduno, et al., 2012). In fact, PTPN22 gene has been reported as a general autoimmunity locus (Smyth, et al., 2004), and the PTPN22 gene variant R620W is a major risk allele associated with general autoimmunity in several populations due to its defect in regulating BCR-mediated B cell tolerance (Burn, et al., 2011). Given the epidemiological data showing the prevalence of autoimmune disease in particular ethnic groups and families, risk alleles in PTP genes like PTPN22 may be informative markers for autoimmune disease susceptibility (Chung & Criswell, 2007). In the following sections, we will include discussion of the potential roles of CD45, SHP-1, and Lyp, PTPs that have been implicated in the interaction with and regulation of NRTKs in the context of autoimmune disorders.

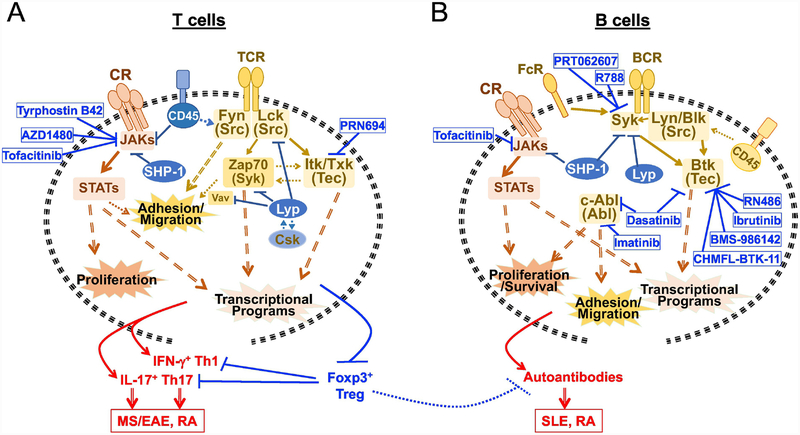

Figure 2. Cytokine and antigen receptor signaling via NRTKs and related PTPs in autoimmunity.

T and B cells respond to cytokine and antigen stimulation via NRTKs-mediated signaling. Activated cytokine receptors (CR) signal via JAK/STAT cascade, leading to cell proliferation and transcriptional activation.

(A) NRTKs, PTPs and NRTK inhibitors in T cell signaling and autoimmunity. TCR signals through Src family kinase Fyn and Lck, and via Syk family member Zap70 and Tec family kinases Itk/Txk, which contribute to cell mobility and transcriptional programing for pathogenesis. Membrane bound PTP CD45 can negatively regulate JAK and Fyn activity, while the cytoplasmic SHP-1 tunes JAK activity. The other cytoplasmic PTP Lyp (PTPN22) interacts with NRTK Csk and is dissociated from Csk upon TCR activation, which allows Lyp to negatively regulate Lck and thus Zap70 (along with the downstream Vav). In the presence of specific cytokines, T cell activation contributes to pathogenic IFN-γ-producing Th1 and IL-17-producing Th17 cell development, and differentially regulates Foxp3+ Treg cell development. When the balance leans toward proinflammatory Th1/Th17 cells, immunomodulatory control by Treg suppression of pathogenic effector cells is impaired, leading to autoimmunity such as multiple sclerosis (MS) in human, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in mice, and Rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

(B) NRTKs, PTPs and NRTK inhibitors in B cell signaling and autoimmunity. BCR signals through Syk and Src family kinases Lyn/Blk, both of which lead to activation of the Tec family kinase Btk. FcR can regulate Syk, Src family kinases and Btk, or can collaborate with the BCR to regulate Syk, Src family kinases and Btk. In B cells, the cytoplasmic PTPs SHP-1 and Lyp can both target Syk and downregulate Syk activity downstream of BCR, and SHP-1 targets JAK downstream of cytokine receptors; the membrane bound PTP CD45 however dephosphorylates the regulatory phosphotyrosine in the C-terminal of Src family kinases therefore positively regulating BCR signaling. Hyperactive B cell activity is linked to the production of auto reactive antibodies that substantially contribute to the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and RA.

3. Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease directed against the central nervous system, resulting in the destruction and atrophy of the myelin sheath and underlying neuronal axons (Dendrou, et al., 2015; Mirshafiey, et al., 2014; Moawad, 2014). Infiltrative autoreactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as pathogenic B cells breach the blood brain barrier and contribute to the neurodegeneration observed in MS patients, including the buildup of MS plaques in both the brain and spinal cord. This can lead to paralysis, vision loss, sensory impairment, and fatigue in some cases (Lehmann-Horn, et al., 2013; Steinman, 2001). The use of the murine model, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), to study the development of MS has allowed in-depth investigation of the mechanism of disease progression. EAE can be induced in genetically susceptible mice (e.g. Swiss Jim Lambert (SJL) mice) by immunizing with the immunodominant epitopes of myelin basic protein (MBP84–104), myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG92–106) or proteolipid protein (PLP139–151 and PLP178–191); or in the commonly used C57BL/6 mice, which requires immunization with the corresponding immunodominant epitope MOG35–55 in the presence of pertussis toxin (Miller, et al., 2010). These EAE models result in a T cell immune response against the protein expressed in myelin sheath, and subsequent development of autoimmune destruction and atrophy of the myelin sheath and underlying neuronal axons. Work done using these EAE models, as well as work in humans with MS, has implicated CD4+ T helper cell subsets Th1 and Th17 in the pathogenesis of both murine EAE and human MS (Bedoya, et al., 2013; El-behi, et al., 2010) (Fig. 2A). CNS-infiltrating, IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells, IL-17-producing Th17 cells, and IFN-γ/IL-17 double producers have been implicated as critical contributors of the immunopathology of this disease (Cao, et al., 2015; Frisullo, et al., 2008; Kebir, et al., 2009; Tabarkiewicz, et al., 2015; Tzartos, et al., 2008). Upon directly comparing the two cell types, Th17 cells seem to be more important in promoting EAE than Th1 cells. Passive transfer studies using isolated CD4+ T cells from SJL mice immunized with PLP underscore the importance of Th1 cells in causing EAE (Langrish, et al., 2005). Only mice receiving ex vivo-isolated PLP specific CD4+ T cells cultured with PLP under conditions that induce Th17 cells developed EAE, while those receiving PLP specific CD4+ T cells cultured under conditions that induce Th1 cells did not develop clinical signs of EAE (Langrish, et al., 2005). Further, merely disrupting or neutralizing IL-17 led to partial EAE protection (Haak, et al., 2009; Komiyama, et al., 2006; Langrish, et al., 2005), suggesting that IL-17 is not the only driver of this disease. Given the importance of TCR and cytokine receptor signaling pathways in regulating the induction of Th1 and Th17 cells, new potential treatment strategies for MS are being developed to target the signal transduction pathways involved in the cellular effector response of these CD4+ T effector subsets. There is an accumulating set of data suggesting the therapeutic potential of targeting the NRTKs to intervene in the induction of Th1/Th17 responses leading to the development of MS/EAE, which are detailed below.

3.1. JAK/STAT pathway in regulating MS/EAE

A number of immunoregulatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-12, IL-21, IL-17, IL-23, and IFN-γ, are involved in the development, differentiation and function of Th1 and Th17 cells (see review (Damsker, et al., 2010)). Many of these cytokines signal through cytokine receptors (CR) and act via the Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (JAK/STAT) cascade, which mediates the development of pathogenic Th1 and Th17 during the progress of MS (Benveniste, et al., 2014; Y. Liu, et al., 2014). These CR pathways utilize JAKs, a four-member family of NRTKs that cross-phosphorylate both themselves and cytokine receptors upon cytokine ligand stimulation (Figs. 1 & 2). The activation of JAKs promote the recruitment of one or more of the six STAT proteins, and the subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation of their C-terminus, leading to STAT dimerization and translocation into the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, STATs bind specific DNA sequences to regulate the transcription of selected genes, including cytokines and growth factors, as well as the effector function of immune cells (J. S. Rawlings, et al., 2004). The important function of the JAK/STAT cascade in regulating the effect of cytokines has been reported in many immune-mediated diseases (O’Shea & Plenge, 2012), including in the EAE model (X. Liu, et al., 2008). Supporting a role for STAT3 in regulating these processes that contribute to MS, human genome wide association screens have identified STAT3 as an MS susceptibility locus (Jakkula, et al., 2010; O’Shea & Plenge, 2012; Oksenberg & Baranzini, 2010).

The inflammatory cytokine IL-12 induces the differentiation of Th1 cells by activating JAK2/TYK2 and STAT4, while IL-6 and IL-23 activate JAK1/2 and STAT3 to drive Th17 differentiation. The critical role of STAT3 in this process, and in the pathogenesis of EAE, is illustrated by the fact that a T cell specific conditional knockout (CKO) of STAT3 protected mice from developing EAE (X. Liu, et al., 2008). This is due to a defect in the development of Th17 cells and subsequent lack of IL-17 production in the CNS. Although STAT3-deficient CD4+ T cells in mice are primed to develop a predominantly IFN-γ-producing Th1 cell program, these STAT3-deficient Th1 cells lack the ability to enter the CNS to contribute to EAE pathogenesis (X. Liu, et al., 2008). STAT3 is also able to regulate Th17 development as it is a master regulator of the Th17 transcription factor RORγt and IL-23R, and is required for Th17-mediated immunopathology and constraining the Th1 response (Egwuagu, 2009). Overexpressing a constitutively active form of STAT3 in naïve CD4+ T cells leads to enhanced Th17 cell development under Th17-differentiating conditions (i.e. in the presence of cytokines IL-6 and IL-23). This overexpressed constitutively active STAT3 reduces the expression of the Th1 master transcription factor T-bet, but increases the expression of Th17 master transcription factor RORγt, and therefore promotes an IL-17-mediated inflammatory response (X. O. Yang, et al., 2007). These data suggest that STAT3 plays an important role in regulating both Th1 and Th17 cell development and effector cytokine response. Similarly, ablation of the STAT4 gene in mice resulted defects in Th1 differentiation coupled with reduced IFN-γ levels, and therefore protection from EAE (Chitnis, et al., 2001). Therefore, dysregulation of the JAK/STAT pathway can induce alterations in the activation of STAT3 and STAT4 proteins, intervene Th1/Th17 effector T cell development and function, which has been associated with MS.

3.2. Tec Family Tyrosine Kinase Itk in regulating MS/EAE

The Tec family NRTK IL-2-inducible Tyrosine Kinase (Itk) is also important in mediating CD4+ T cell function during EAE. Itk belongs to the five-member family of Tec kinases, which, with the exception of Txk/Rlk, share a characteristic pleckstrin homology (PH) domain along with a Tec homology (TH) domain that allows them to bind to membrane phospholipids (Fig. 1A). All five kinases in this family resemble Src family kinases in that they contain a SH3-SH2 cassette, which allows Itk to interact with and bind to downstream adaptors and substrates to successfully transduce signals (Andreotti, et al., 2010). Upon TCR stimulation by antigen presented by antigen presenting cells, the Src kinase Lck transphosphorylates Itk on tyrosine 511, allowing for autophosphorylation of Itk on tyrosine 180. Once fully activated, Itk phosphorylates the downstream protein PLCγ1 (on tyrosines 775 and 783), which hydrolyzes the phospholipid PIP2 to produce the signaling molecules inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol (Grasis & Tsoukas, 2011). Both of these signaling molecules are integral for calcium influx and transcription factor release (NFAT, NFκB, AP-1) (Berg, 2009; W. C. Yang, et al., 2000).

Itk-deficient T cells have defects in developing into Th17 cells, in part, due to a decrease in intracellular calcium stores required for the activation of the transcription factor NFAT (Gomez-Rodriguez, et al., 2009). Itk−/− mice are protected from developing EAE, as Itk signals are required for the development of pathogenic Th17 cells and their ability to traffic into the CNS (Kannan, et al., 2015). Itk also functions as an important regulator of CD4+ T regulatory (Treg) cells, which are crucial suppressors of the immune system and essential in the maintenance of self-tolerance (Sakaguchi, et al., 2008; Vignali, et al., 2008). CD4+ Treg cells express the master transcription factor forkhead box protein P3 (Foxp3), and function in suppressing other leukocytes through a number of different mechanisms including the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β, IL-10), expression of the cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), and release of cytotoxic molecules (Fas, Granzyme β) (L. Lu, et al., 2017; Sojka, et al., 2008). Treg cells control autoimmunity by restraining the activation and effector functions of inflammatory T cells such as Th17 cells (Levine, et al., 2017). Foxp3 can bind to the promoter region of the Itk gene and suppress its expression (Marson, et al., 2007), suggesting that the Foxp3+ Treg cells have an intrinsic transcriptional program to tune Itk-mediated signals. Interesting, Itk negatively regulates the differentiation of Treg cells, as its level of expression is inversely correlated to the abundance of Foxp3+ Treg cells in murine models (Gomez-Rodriguez, et al., 2014; Huang, et al., 2014; Owen, et al., 2019). Itk may therefore control the balance of Th17 and Treg cells and thus modulate the development of MS.

3.3. PTPs in negative regulation of JAK/STAT in MS

Given the importance of the JAK/STAT pathway in MS, proper control of this pathway is critical. Indeed, aberrant activation of the JAK/STAT pathway can be attributed to defects in negative regulators that facilitate the attenuation of cytokine signaling. Although different classes of negative regulators exist, including suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) and protein inhibitors of activated STATs (PIAS), we focus here on PTPs that are able to dephosphorylate tyrosine residues on JAKs and STATs and are critical for the function of this pathway (J. S. Rawlings, et al., 2004). The phosphatase SHP-1 is constitutively expressed in hematopoietic cells and negatively regulates the JAK/STAT pathway. SHP-1 contains two SH2 domains followed by a phosphatase domain (Fig. 1B, (Yasukawa, et al., 2000)), and utilizes either an SH2-dependent mechanism to bind to receptor complexes or a SH2-independent mechanism to directly bind to JAK kinases, resulting in the dephosphorylation of the JAKs (Yasukawa, et al., 2000). Given the importance of SHP-1 in suppressing cytokine signaling, many autoimmune diseases are linked to abnormalities in PTPs (Vang, et al., 2008). For example, motheaten (me/me) mice containing a recessive allele mutation for SHP-1 (PTPN6), develop severe mucosal (skin and lung) inflammation and autoimmunity, accompanied with early death around 3 to 9 weeks of age (Shultz, et al., 1993). This was the first example in which a PTP was shown to be involved in immune modulation to limit the development of inflammation and autoimmunity. Me/me mice however don’t succumb to a “typical” autoimmunity due to T and B cell disorders. T and B cells are dispensable for the development of mucosal inflammation and its associated early death observed in the me/me model (Yu, et al., 1996). Instead, B cells are involved in the development of the autoimmune symptoms in the me/me model, and B cell-specific deletion of SHP-1 in mice results in aberrant BCR signaling in B1a cell subset and causes systemic autoimmunity (Pao, et al., 2007). Moreover, while neutrophil-specific deletion of SHP-1 led to dermal inflammation without any overt effects in causing immunity, dendritic cell (DC)-specific deletion of SHP-1 resulted in hyperactive DCs, significantly elevated T and B cell numbers, and severe autoimmunity in mice (Abram, et al., 2013). These data suggest a critical role of SHP-1 in mediated DC interaction with T and B cells and a B cell-intrinsic regulatory function in tuning BCR signaling activation. In support of these findings, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from human MS patients expressed lower levels of SHP-1 protein and mRNA, suggesting that SHP-1 may be involved in the pathogenesis of MS (Christophi, et al., 2008; Feng, et al., 2002).

Another PTP critical in regulating the JAK/STAT pathway involved in MS is CD45, a transmembrane phosphatase known for its role in positively regulating the Src-family kinases Lck and Fyn (Fig. 1B). However, CD45 is also involved in the inhibition of JAK/STAT cytokine receptor signaling (J. S. Rawlings, et al., 2004). Recombinant CD45 (rCD45) has been shown to dephosphorylate tyrosine residues Tyr1007 and Tyr1008 of JAK2, as well as decrease the kinase activity of JAK1 and Tyk2 in vitro. Furthermore, IFN-α stimulation of CD45−/− cells led to increased activation of JAKs and STAT proteins (Irie-Sasaki, et al., 2001), indicating that CD45 is a JAK phosphatase and has an inhibitory effect on cytokine signaling, and may thus regulate the development of MS by regulating the JAK/STAT pathway.

3.4. Therapeutic implications of NRTK inhibitors in MS

3.4.1. JAK inhibitors

Given the importance of the JAK/STAT pathway in mediating the expression of many proinflammatory cytokines involved in MS/EAE, JAK inhibitors hold significant therapeutic potential in the treatment of this neuroinflammatory disease. Indeed, the JAK1/2 inhibitor, AZD1480, functions as a competitive inhibitor of the kinase activity of JAK1 and JAK2, and has been shown to suppress the differentiation of Th1 cells and their production of IFN-γ in vitro, by inhibiting the tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT4 (Y. Liu, et al., 2014). AZD1480 also inhibits Th17 polarization, along with the STAT3 targeted genes IL-17A, RORγt, IL-22, and IL-23R (Y. Liu, et al., 2014). In vivo, administration of AZD1480 attenuates lymphocyte infiltration and demyelination, resulting in attenuated disease severity of mice induced to develop EAE. Similarly, in primary human CD4+ T cells from PBMCs, AZD1480 inhibits the expression of STAT1 and STAT3, and thus Th17 differentiation in vitro. This data suggests that AZD1480 can be used to inhibit the JAK/STAT pathway and its downstream targets, and may provide clinical efficacy in the treatment of human MS (Hamid, et al., 2017; Y. Liu, et al., 2014). Another JAK2 inhibitor, tyrphostin B42, has also been shown to prevent IL-12 induced tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK2 and attenuate disease severity in murine EAE (Bright, et al., 1999), supporting the idea that JAK inhibitors may have utility in treating MS.

3.4.2. Itk kinase inhibitors

The absence of the Tec kinase Itk has been shown to protect mice from developing EAE (Kannan, et al., 2015). While inhibitors of Itk have not been examined in this model, this data suggests that inhibitors of Itk may have some therapeutic benefit in this disease. PRN694 is a selective and irreversible covalent inhibitor of Itk (targeting Cys442), but also targets the related Tec kinase Txk (a.k.a. Rlk; targeting Cys350). Both Itk and Txk are expressed in Th1 cells while Th2 cells express Itk exclusively. Deletion of Itk leads to defects in Th17 differentiation and function, the absence of Txk does not have any reported effects, however, deletion of both Itk and Txk has been reported to lead to more severe defects in T cell activation (Schaeffer, et al., 2001). PRN694 targets both Itk and Txk, and has been shown to inhibit the release of proinflammatory cytokines IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ by human primary CD4+ T cells. PRN694 also inhibits production of IL-17A by enriched human Th17 cells (Zhong, et al., 2015). As a dual Itk and Txk inhibitor, PRN694 may be beneficial in reducing IL-17A production in vivo, and may be efficacious for MS.

4. Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory joint disease characterized by the infiltration of autoreactive T and B cells into synovial tissue, leading to the degradation of cartilage and bone. Synoviocytes are responsible for the healthy state of surrounding cartilage tissue and infiltrating immune cells contribute to hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the synovial membrane (Feldmann, et al., 1996). During development of RA, both T and B cells migrate into the synovial tissue and release different immune mediators along with degradative molecules that ultimately promote chronic inflammation and joint destruction (D’Aura Swanson, et al., 2009; Smolen & Steiner, 2003). A critical role for the formation and pathogenic role of autoantibodies by B cells is illustrated by the fact that in RA patients, B cell depletion with Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody that targets B cell CD antigen CD20 in humans, leads to better clinical outcomes (Edwards, et al., 2004). The effector response of these pathogenic T and B cells is regulated by a number of NRTKs including Syk, JAKs, and the Tec kinase Btk (D’Aura Swanson, et al., 2009). The inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1, and TNF-α have also been found in the synovial tissue of RA patients, and are known to contribute to the pathogenesis of RA (Feldmann & Maini, 2001; Kay & Calabrese, 2004; Smolen, et al., 2008). Therefore, studying the underlying signaling mechanism associated with cytokines can further our understanding of autoimmune synovitis.

4.1. Syk in the development of RA

The spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) is a mediator of immunoreceptor signaling, regulating activating signals transduced through the BCR and Fc receptors present on B cells, granulocytes, dendritic cells and macrophages (D’Aura Swanson, et al., 2009). Syk has tandem SH2 domains (Fig. 1A) that bind to proteins containing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motifs (ITAM) within immune cell receptors during signal transduction (Gomez-Puerta & Mocsai, 2013; Greenhalgh & Hilton, 2001; Lowell, 2011). Upon Syk activation, a signaling cascade is initiated and downstream proteins such as the mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are activated. Activation of MAPKs has broad effects and in B cells, results in the increase of production of IL-6 and metalloproteinase (MMP), both of which can contribute to the pathobiology of RA (Okamoto & Kobayashi, 2011). Additionally, Syk plays a critical role in BCR-induced B cell activation and antibody secretion (Fig. 2B). Syk−/− mice are embryonically lethal, and so cannot be used in assessing the role of Syk in autoantibody-induced arthritis. However, Syk−/−/WT chimeras can be generated via transplantation of Syk−/− fetal liver stem cells into lethally irradiated wildtype recipient. Syk−/− hematopoietic chimeric mice have been used to assess for autoantibody-mediated arthritis using a K/BxN serum-transfer model. The K/BxN murine model expresses a transgenic TCR that recognizes the ubiquitously expressed self-antigen glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI), resulting in T cell-mediated hyperactive production of anti-GPI autoantibodies by B cells and the induction of joint-specific inflammation that resembles RA (Kouskoff, et al., 1996). Transferring K/BxN serum containing anti-GPI autoantibodies to recipient mice can reliably cause arthritic inflammation (Monach, et al., 2008). Syk−/− bone marrow chimeric mice are protected from K/BxN autoantibody-mediated arthritis, with no inflammation and significantly less bone erosions compared to wildtype chimeric controls (Jakus, et al., 2010). This in vivo data provides direct evidence that Syk is important in the development of autoimmune arthritis, and suggests that Syk may play an important role downstream of Fc receptors on B cells, granulocytes, dendritic cells and macrophages in regulating disease. However, whether this is due to its role downstream of the BCR in B cells, or downstream of Fc receptors is not clear (D’Aura Swanson, et al., 2009).

4.2. JAKs in the development of RA

As previously mentioned, JAKs are intimately involved in cytokine signaling (Gomez-Puerta & Mocsai, 2013). Elevated levels of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 have been identified in rheumatoid joints, and it is thought to be a key promoter of chronic inflammation in RA patients. IL-6 activates the JAK/STAT3 pathway (Heinrich, et al., 1998; Kuuliala, et al., 2015; Mori, et al., 2011), and increased STAT3 levels have also been reported in the synovial cell linings and in infiltrating T cells from the joints of RA patients (Krause, et al., 2002). Further, STAT3 phosphorylation/activation in CD4+ T cells is thought to be linked to RA activity, and has been proposed as a biomarker to predict recent onset RA (Isomaki, et al., 2015; Kuuliala, et al., 2015; Oike, et al., 2017). Since STAT3 knockout mice are embryonically lethal, Oike et al established an interferon-activated Cre-driven (Mx1-Cre) STAT3 conditional knockout mouse to examine the role of STAT3 in a murine model of RA, collagen-induced arthritis (CIA). CIA utilizes the immunization against heterologous type II collagen to induce collagen-specific effector T cells and antibodies that recognize collagen antigens in the immunized hosts and cause arthritic syndrome (Brand, et al., 2007; Courtenay, et al., 1980). In CIA, serum levels of IL-6 and IL-17 were significantly reduced, and joint inflammation was blocked in the conditional STAT3 knockout mice, compared to controls (Oike, et al., 2017). In humans, IL-6 levels are also elevated in RA patients, correlating with STAT3 phosphorylation in CD4+ T cells (Kuuliala, et al., 2015). Th17 cells and the cytokine IL-17 can promote RA pathogenesis in the CIA murine model of arthritis (Fujimoto, et al., 2008; Lubberts, et al., 2001; Nakae, et al., 2003), while STAT3 can modulate Th17 and Treg cell differentiation in RA patients. Indeed, knockdown of STAT3 using siRNA in CD4+ T cells derived from the synovial fluid and peripheral blood of RA patients resulted in an increase in the percentage of Foxp3+ Treg cells and prevented Th17 differentiation, suggesting a critical role for STAT3 in counter-regulating Th17 and Treg cell differentiation in RA (Ju, et al., 2012). Dysregulation of the IL-6/STAT3 pathway is therefore a major inducer of arthritis and promotes RA pathogenesis (Isomaki, et al., 2015).

4.3. Btk in the development of RA

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) also belongs to the five-member family of Tec kinases (Fig. 1A), and B cells rely on Btk for BCR-mediated signal transduction. Upon BCR activation, Btk is recruited to the plasma membrane and activated in a similar manner to Itk, and phosphorylates phospholipase C-γ2 (PLC-γ2), catalyzing the generation of diacylglycerol and inositol triphosphate, which increase Ca2+ uptake and activates different transcription factors (Shao & Cohen, 2014a). Hence, Btk plays a major role in BCR signaling and is linked to B cell development, selection, activation, and survival. Indeed, Btk-deficiency in mice and humans results in the B cell immunodeficiency known as Bruton’s X linked agammaglobulinemia (Mano, 1999). Due to the role of Btk in controlling B cell proliferation and survival, prior attention has been focused on Btk as a modulator of B cell expansion in B cell lymphoma and leukemia (Satterthwaite, et al., 1998). The selective Btk inhibitor, CHMFL-BTK-11 (targets Cys481) has been shown to block Btk and ERK phosphorylation following stimulation of the BCR in human B cell lines as well as in primary human B cells. Wu and colleagues have examined CHMFL-BTK-11 in a rat model of adjuvant-induced arthritis, and found that its administration protected the joint’s connective tissue from destruction caused by synovial infiltrating inflammatory cells, normalized levels of serum IgG1 and IgM, and reduced IL-6 production (Wu, et al., 2017). The Btk inhibitor BMS-986142 has also been shown to be therapeutically effective in the murine CIA model, and when combined with the immunosuppressive drug Methotrexate, there was a 53% reduction in inflammation and bone resorption, compared to 24% and 10% by a single drug respectively (Gillooly, et al., 2017). BMS-986142 also reduced the production of cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α in stimulated human B cells (Gillooly, et al., 2017). Anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) is present in a majority of RA patients and is a powerful biomarker in clinic for diagnostics (Puszczewicz & Iwaszkiewicz, 2011) and RA subtype classification (Aletaha, et al., 2010). A role for Btk has been recently suggested in RA patients since the levels of Btk protein are found to be increased in all B cell subsets (naïve and memory B cells) in ACPA-positive RA patient samples, compared to samples collected from healthy cohorts and ACPA-negative RA patients (Corneth, et al., 2017). This data suggests that enhanced Btk expression may be a driver of autoimmunity in RA.

4.4. Lyp/PTPN22 Deficiency in RA

Interaction between Lyp (a.k.a. PTPN22) and Csk leads to the inhibition of Lck and functions to attenuate TCR signaling (Fig. 1A). A single nucleotide polymorphism in Lyp, C1858T, prevents Lyp from interacting with Csk, and has been associated with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis (de la Puerta, et al., 2013). Importantly, a dominant negative isoform of the phosphatase known as PTPN22.6, has been proposed as a potential biomarker for RA (Chang, et al., 2012). Moreover, analysis of gene polymorphisms in human RA patients found that the most clinically relevant risk alleles in both Lyp and Csk led to downregulated expression of these PTPs, suggesting that the sufficient expression of Lyp and Csk may play a role in preventing autoimmunity associated with RA (Remuzgo-Martinez, et al., 2017). Chan et al assessed how Lyp deficiency affects TCR signaling and T/B cell development. Using Ptpn22−/− mice, they showed that aged Lyp-deficient mice had an increase in both effector and memory T cell numbers (Hasegawa, et al., 2004), and associated with an increase in spontaneous well-developed germinal centers in the spleen and peyer’s patches, follicular B cells, and autoantibody levels (Hasegawa, et al., 2004; Maine, et al., 2014). Intriguingly, although B cells express Lyp, the increase in antibody levels in Ptpn22−/− mice was attributed to the T cell compartment, as Lyp deficiency has little effect on BCR signaling, and seems to be more important in regulating the activity of T cells in order to prevent a hyperactive follicular helper T cell (Tfh) mediated antibody response (Maine, et al., 2014). Furthermore, increased disease severity is observed in the KBxN mouse model of arthritis using Ptpn22−/− mice. While Ptpn22−/− models provide insight into autoimmune development, studies have begun examining Ptpn22 knockin models to more accurately recapitulate the human risk variant condition in hopes of understanding how this single nucleotide polymorphism increases susceptibility to autoimmunity (see section SLE) (Samuelson, et al., 2012; Texido, et al., 2000; Y. Y. Wu, et al., 2015).

4.5. Therapeutic benefit of NRTK inhibitors in RA

4.5.1. Syk inhibitors

The Syk inhibitor fostamatinib disodium (R788, Fig. 2B) has been examined in the CIA murine model, and was found to ameliorate clinical signs of arthritis and bone erosion (Pine, et al., 2007). Furthermore, in phase II clinical trials in RA patients, those receiving R788 had significantly less IL-6 and MMP-3 in their serum, accompanied by a reduction in arthritis activity when compared to placebo (Okamoto & Kobayashi, 2011). Typical of many kinase inhibitors, R788 has off-target effects towards Lck, JAK1, JAK3, and c-Kit. PRT062607 is a more potent and selective Syk inhibitor than R788, with over 80 fold greater in affinity for Syk than any other kinase (Spurgeon, et al., 2013). PRT06260 inhibits BCR/Syk signaling (40%) and hind paw inflammation (55%) in the rat CIA model at a lower dose than R788 (10 mg/Kg vs. 100 to 50 mg/Kg for R788). PRT062607 was shown to be safe and well tolerated without any adverse effects by healthy human volunteers, and whole blood from these volunteers (receiving 200/300mg/kg of the inhibitor) revealed that BCR mediated B cell activation was inhibited (75%) (Coffey, et al., 2017). Targeting Syk may be therefore be an attractive target for the treatment of RA.

4.5.2. JAK inhibitors

JAK antagonists are also being explored for their ability to regulate STAT activation downstream of IL-6 (Pesu, et al., 2008). Tofacitinib, a JAK inhibitor was approved by the FDA in 2012 as a second-line treatment for RA in adults (Gomez-Puerta & Mocsai, 2013). The combined use of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib and Syk inhibitor PRT062607 not only prevented the development of arthritis, but also reduced disease severity in established arthritis in mice (Llop-Guevara, et al., 2015). This suggests that combining JAK/Syk kinase inhibition may be more effective than using a single kinase inhibitor, since these kinases are involved in distinct pathways and the combined use may allow for inhibition of multiple pathogenic pathways (Llop-Guevara, et al., 2015).

Since JAK/STAT3 pathway also influences the proportions of Th17 and Treg cells, a JAK inhibitor may work to increase the percentage of immunomodulatory Treg cells while decreasing the number of pathogenic Th17 cells in RA.

4.5.3. Btk inhibitors

The NRTK inhibitor Dasatinib, which targets the NRTK Abl, as well as Btk, thus blocking BCR signaling, shows promise in limiting the severity of RA (Hantschel, et al., 2007). Dasatinib has been shown to mitigate the severity of disease in both the CIA and K/BxN mice models of arthritis (Smolen & Steiner, 2003). Additionally, other Btk inhibitors such as Ibrutinib, approved for the treatment of B cell lymphomas, are also being analyzed for their potential use in treating RA (Norman, 2016; Smolen & Steiner, 2003). Indeed, the reversible Btk inhibitor BMS-986142 was recently shown to selectively inhibit Btk in human B cells and is in clinical trials for the treatment of RA (Gillooly, et al., 2017). BMS-986142 inhibits B cell responses (anti-KLH IgM and IgG) in vivo, and is able to reduce clinical disease in mouse models of CIA, and when co-administered with either methotrexate or Etanercept (a blocker of the inflammatory cytokine TNFα), there was a significant additive clinical benefit (Gillooly, et al., 2017). This work suggests that targeting Btk may be a promising approach for treating RA.

5. Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystemic inflammatory autoimmune disease characterized by a breakdown in tolerance, resulting in the production of autoreactive antibodies against nuclear components such as double stranded DNA (dsDNA), nucleosomes, and histones (Chasset & Arnaud, 2018). Additionally, immune cell complexes of autoantibodies and chromatin are formed within various tissues and participate in the pathogenesis of SLE (Rother & van der Vlag, 2015). Chronic inflammation leads to damage of many different organs in SLE patients, with one of the more grave organ complications being lupus nephritis (Kong, et al., 2017). Investigations of SLE patients have implicated tyrosine kinases as major pathogenic players in autoreactive T cells and autoantibody-producing B cells in this disease, and are thought to be culpable for the cellular abnormalities that develop during SLE (Shao & Cohen, 2014a).

5.1. Btk in SLE

In SLE, B cell tolerance is lost, giving rise to autoantibodies against nuclear self-antigens that are in turn responsible for the severe inflammation and damage observed in various organs. Given the role of Btk in B cell development and function, this kinase has been investigated for a potential role in this disease. Overexpression of a constitutively active Btk mutant in B cells led to an SLE-like pathology state in mice, and in enhanced plasma cell numbers as well as the production of antinuclear autoantibodies, which is dependent on the kinase activity of Btk (Kil, et al., 2012; Paley, et al., 2017). Additionally, infection of mice overexpressing Btk leads to defects in negative selection, and gives rise to self-reactive B cells in the lung. This suggests that Btk kinase activity regulates the production of autoantibodies. Studies in humans revealed that patients with SLE exhibit an elevated frequency of Btk+ B cells in peripheral blood compared to healthy patients. The increased percentage of Btk+ B cells was also associated with lupus nephritis, as patients with this disease had greater Btk expression in their glomeruli (Kong, et al., 2017). Thus, Btk-mediated BCR signaling is essential in regulating the development of SLE.

5.2. Src family NRTK Lyn in SLE

Lyn is a member of the Src family tyrosine kinases (Fig. 1A). All nine members of the Src family contain a conserved protein structure and participate in both stimulatory and inhibitory signaling pathways (Boggon & Eck, 2004). Lyn is expressed in B cells, not T cells, and regulates signals from the BCR by phosphorylating CD19 and the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs of Igα/Igβ subunits, thereby controlling B cell activation, differentiation and antibody secretion. Lyn can also function by phosphorylating immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs found in receptors on B cells, and has been identified as an important signaling modulator in promoting self-tolerance (Proekt, et al., 2016; Shao & Cohen, 2014a; Y. Xu, et al., 2005). This is exemplified by the overactive humoral response to nuclear antigens and severe lupus-like autoimmunity that develops in Lyn−/− mice (Yu, et al., 2001). Lyn−/− mice were also shown to manifest autoreactive IgE antibodies, which were responsible for activating basophils and promoting a Th2 response. Decreases in Lyn expression, along with elevated IgE levels, are also found in human SLE patients and are thought to contribute to lupus nephritis (Charles, et al., 2010). Indeed, B cell specific knockout of Lyn was sufficient to induce autoimmunity and the presence of autoreactive antibodies and glomerulonephritis in mice. This data suggests that B cell-intrinsic defects are sufficient in driving SLE (Lamagna, et al., 2014). Indeed, a Lyn single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was found to be associated with SLE in European individuals (R. Lu, et al., 2009).

5.3. Blk in SLE

B lymphocyte kinase (BLK) belongs to the Src kinase family, and is expressed in γδ T cells, pancreatic β cells, dendritic cells and to a much larger extent in B cells, and is activated by the BCR and plays a role in intracellular signaling and cell differentiation of B cells (Texido, et al., 2000). Blk−/− and Blk+/− mice have significantly reduced numbers and percentages of marginal zone (MZ) B cells, as well as enhanced numbers of peritoneal cavity and splenic B1a cells, and the MZ B cells were hyper responsive following BCR activation in vitro. Blk−/− and Blk+/− mice also produced antinuclear antibodies suggesting a role in B cell tolerance (Samuelson, et al., 2012). Increased numbers of B1 cells, like MZ B cells, correlate with lupus pathogenesis and aged female Blk−/− mice manifest immune complex mediated glomerulonephritis along with higher amounts of serum IgG anti-dsDNA antibodies. In fact, biopsies taken from SLE confirmed patients reveal that B cells, including B1-like cells (CD20+CD43+), were detectable within affected kidney samples (Y. Y. Wu, et al., 2015). Several Blk polymorphisms in the promoter region of the gene have been identified in human populations, such as the SNP rs2736340, which predispose to developing SLE. Healthy human homozygous carriers of the risk allele recapitulated the murine data with an increase in B1a cell percentages and IgG anti-dsDNA antibodies, along with a decrease in Blk mRNA expression. This offers further support that lupus nephritis is dependent on Blk expression, with reduced Blk expression causing significant changes in the B cell subset population of MZ B and B1 cells. Hence, Blk inhibitors may be promising in the treatment of SLE. To date, broad specific inhibitors of Src family kinases have been developed (such as Dasatinib), but Blk-specific inhibitors remain under development (Petersen, et al., 2017; Shao & Cohen, 2014b).

5.4. Lyp/PTPN22 in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Lyp isoforms are differentially expressed in various hematopoietic cells, and primary T cells isolated from the peripheral blood of SLE patients were found to express higher transcript levels of PTPN22 compared to healthy controls (Chang, et al., 2014). In fact, two different PTPN22 SNPs were associated with SLE disease risk in European American (rs2476601) and Hispanic populations (rs3765598) (Namjou, et al., 2013). Researchers have generated a knockin mouse model by mutating the murine orthologue of PTPN22, to encode for the variant protein PepR619W to mirror the human gene variant Lyp-R620W. These knockin mice developed SLE like features, including a reduction in lifespan and glomerular lesions, along with enlarged spleen/thymus and high titers of antinuclear antibodies (Dai, et al., 2013; J. Zhang, et al., 2011). Further, these mice had a significant increase in the number and percentage of age dependent B cells compared to WT controls, which are known to develop earlier, at a higher proportion in lupus prone mice, and produce autoantibodies. The R620W polymorphism is a gain of function variant that has been shown to impair central and peripheral B cell tolerance, resulting in the escape of autoreactive B cells which promote autoimmunity (Menard, et al., 2011).

As previously mentioned, Lyp is a negative regulator of T cell activation and regulates Src family of tyrosine kinases via its ability to dephosphorylate Csk. Csk is also involved in autoimmunity, as a Csk polymorphism, rs34944043, has been identified as a risk allele associated with SLE, and peripheral blood from patients carrying this SNP exhibit increased phosphorylation of Lyn at Tyr508, along with higher concentrations of IgM (Deng & Tsao, 2014). This data suggests that Csk should be included when examining the canonical PTPN22 autoimmunity gene (Manjarrez-Orduno, et al., 2012). Therefore studying the effect of different allelic variants of the PTPN22 gene, in concert with its interaction with Csk, will be crucial due to its predisposition for autoimmunity (Burn, et al., 2011).

5.5. Therapeutic Benefit of NRTK inhibitors in SLE

Dysfunctional Btk has been implicated in SLE, and therefore small molecule inhibitors of Btk have received wide attention as potential therapies for this disease. Ibrutinib, the FDA approved irreversible inhibitor of Btk (Shao & Cohen, 2014a), has been evaluated for effect on SLE using a transgenic mouse model that over-express Btk specifically in B cells, and which spontaneously develops antinuclear autoantibodies and manifest SLE-like autoimmunity. Administration of Ibrutinib to this transgenic mouse model results in reduced plasma cell numbers and normalized production of autoantibodies, suggesting a potential therapeutic benefit for systemic autoimmune diseases like SLE (Kil, et al., 2012). The use of another Btk inhibitor, RN486, in the NZB/NZW, autoimmune prone mouse model of SLE, also resulted in reduced glomerulonephritis (Mina-Osorio, et al., 2013). Whether Btk inhibitors are effective in ameliorating SLE disease in humans remains to be seen since to date Btk inhibitors have not been approved for use in SLE patients. However there is promising data that Btk may be a possible target for the treatment of SLE in human patients (Kong, et al., 2017).

6. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) is a chronic disease in which T cell mediated destruction of pancreatic islet β cells results in insulin deficiency and hyperglycemia (van Belle, et al., 2011). Self-reactive T cells are thought to be a contributory factor in the pathogenesis of the disease, with islet targeting autoantibodies against insulin being identified prior to the onset of T1D (Katsarou, et al., 2017). Both CD4+ and CD8+ cells are involved in the progression of the disease, and CD4+ T cells specific for the most well defined autoantigens, insulin and the neuroenzyme GAD65, have been identified in T1D patients (Oling, et al., 2012; Roep & Peakman, 2012). However, the exact mechanism responsible for the breakdown in CD4+ T cell tolerance towards insulin autoantigens in unknown.

6.1. NRTK c-Abl in T1D

C-Abl (mammalian version of Abl, also known as Abl1) is a PTK belonging to the two-member Abl family. C-Abl is expressed in both B and T cells, and is thought to be activated by growth factors and phosphorylated by Src family kinases (Plattner, et al., 1999). All kinases in this family share conserved Src homology-2 (SH2) and −3 (SH3) domains which allow for autophosphorylation, and contain a long carboxy-terminal extension known as the last exon region (Hantschel, et al., 2007) (Fig. 1A). The last exon region consists of proline-rich motifs, protein-protein interaction sites for adaptor proteins, and nuclear localization and export signals that allow c-Abl to easily shuttle from the nucleus to the cytosol (Hantschel & Superti-Furga, 2004). Abl kinases have been shown to be required for T cell development and function, as Abl/Arg conditional double knockout T cells undergo impaired T cell signaling and proliferation (Gu, et al., 2009). Additionally, c-Abl has been reported to interact with CD19 and may be a target of the BCR complex (Zipfel, et al., 2000). Aside from its role in immune cell antigen receptor signaling, c-Abl is thought to be important in cytoskeleton reorganization, cell division, and cell stress (Plattner, et al., 1999). Furthermore, c-Abl has been implicated in the development of T1D, with a role in cellular stress. During the development of T1D, β cell destruction is known to occur through the induction of apoptosis (Lee, et al., 2004). This spontaneous cell death is thought to originate from the high endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress experienced during the process known as the unfolded protein response (UPR), required for insulin secretion (Scheuner & Kaufman, 2008). Due to the resultant decrease in the number of β cells in T1D, the remaining functional β cells are thought to compensate for the decline in cell numbers by increasing insulin production in an effort to maintain blood glucose homeostasis. However, this condition also increases the existing UPR of the ER (Morita, et al., 2017; Scheuner & Kaufman, 2008). Indeed, removing the islets of human T1D patients from the stressful ER environment of the “diabetic milieu” can lead to recovery of previously nonfunctional β cells in vitro. This data reinforces the idea that ER stress is a major contributor to β-cell death and dysfunction. Abl kinases are important components of the UPR and participate in regulating the endoribonuclease, IRE1α (Morita, et al., 2017). Abl can increase the enzymatic activity of IRE1α, leading to an increase in ER stress mediated apoptosis. Abl inhibitors may therefore be able to relieve ER stress in β-cells and thus prevent their apoptosis.

6.2. Therapeutic Benefit of NRTK inhibitor Imatinib in T1D

Imatinib (Gleevec), one of the most prescribed inhibitors, is an inhibitor of the Abl kinase and was approved by the FDA in 2001 for treatment of different types of leukemia (Bloudek, et al., 2015; P. Wu, et al., 2015). Imatinib has also been reported to have immunomodulatory effects and can alter adaptive immune responses by inhibiting T cell proliferation and activation (Crunkhorn, 2008). Due to Imatinib’s immunosuppressive effect, the drug has been explored as a treatment for T1D (Sadanaga, et al., 2005). Treatment of prediabetic nonobese mice with Imatinib protected these mice from developing diabetes over the 7-week timeframe (Louvet, et al., 2008). However, the underlying mechanism responsible for Imatinib’s function in controlling T1D is still controversial, as treatment with the inhibitor did not alter the absolute number of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells and has been shown to have no effect on human T cell function or response (Louvet, et al., 2008). However, Imatinib may be functioning to reduce β cell death by modulating UPR, suggesting that a link between IRE1α, and Abl may be responsible for the therapeutic effects of the drug (Morita, et al., 2017). Hence, Imatinib is currently being repurposed for the treatment of new-onset T1D and is currently undergoing phase 2 clinical trials (Morita, et al., 2017).

7. Conclusion

NRTKs are integral in regulating activation signals in immune cells (Patterson, et al., 2014). The initiation and regulation of signal transduction cascades in immune cells are crucial in mediating cell differentiation, activation, survival, and effector responses. Dysfunction/dysregulation of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases have been implicated in the pathogenesis of a number of autoimmune diseases. In particular, dysregulated signaling in kinase pathways regulated by the JAK/STAT, Tec family kinases Itk and Btk, c-Abl, Syk, and the Src family kinase Lyn and Blk have been shown to regulate the development of multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes. Additionally, PTPs present a major control mechanism over signaling by counterbalancing the activity of protein kinases, and the PTPs SHP-1, CD45 and PTPN22 have been suggested to play important roles in regulating the development of autoimmune diseases by virtue of their ability to regulate critical NRTK pathways. Lastly, the success of small molecule protein kinase inhibitors for the treatment of various cancers holds great translatable promise for immune-mediated diseases, and the (re)purposing of these drugs for autoimmune conditions is currently underway (see Table 1, (Patterson, et al., 2014)).

Table 1:

NRTK inhibitors with potential for treatment of autoimmune disease

| Generic Drug Name | Stage of Development | Relevant Target | Primary Disease Indication | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZD1480 (Verstovsek, et al., 2015) | Phase I | JAK1, JAK2 | Solid & myeloproliferative neoplasm | JAK/STAT pathway |

| Tyrphostin B42 (AG490) (Davoodi-Semiromi, et al., 2012) | Preclinical studies with mice | JAK2 | Cancer cell lines, murine model of type 1 diabetes | |

| Tofacitinib (Pfizer Inc) (Cohen, et al., 2017) | Approved in 2012 | JAK1, JAK3 | Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis | |

| PRN694 (Fuhriman, et al., 2018) | N/A | Itk, Txk/Rlk | Murine models of colitis and psoriasis | TCR signaling and function |

| Fostamatinib Disodium (Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc) (Newland, et al., 2018) | Approved in 2018 | Syk | Immune thrombocytopenia | BCR signaling |

| PRT062607 (Portola Pharmaceuticals Inc) (Coffey, et al., 2017) | N/A | Research in B cell mediated malignancies | ||

| Ibrutinib (AbbVie) (Akinleye, et al., 2013) | Approved in 2013 | Btk | Mantle cell lymphoma, Graft versus host disease, B cell malignancies | BCR signaling |

| RN486 (D. Xu, et al., 2012) | Preclinical studies with mice | Murine models of rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| BMS-986142 (Bristol-Myers Squibb) (Gillooly, et al., 2017) | Approved in 2012 | Rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome | ||

| Dasatinib (Bristol-Myers Squibb) (Ishida, et al., 2016) | Approved in 2006 | Bcr-Abl, Src, Lck, Btk | Chronic myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia | TCR and BCR signaling |

| Imatinib (Novartis) (Iqbal & Iqbal, 2014) | Approved in 2001 | Bcr-Abl, Lck | Chronic myeloid leukemia, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, various cancers | Unclear; leads to inhibited proliferation and apoptosis |

Acknowledgements

We thank members in the August and Huang laboratories for helpful discussions. Research related to this review by the authors are supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI120701, AI138570 and AI126814 to A.A.; AI137822 and GM130555-Sub#6610 to W.H.; and AI129422 and AI138497 to A.A. and W.H.;), a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Professorship (to A.A.), a Pilot Grant from the Center for Experimental Infectious Disease Research (funded by NIH P30GM110760) and an award from the Competitive Research Programs of the Louisiana State University (to W.H).

Abbreviations

- NRTK

Non-Receptor Tyrosine Kinase

- PTP

Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase

- MS

Multiple Sclerosis

- RA

Rheumatoid Arthritis

- SLE

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- T1D

Type 1 Diabetes

- BCR

B Cell Receptor

- TCR

T Cell Receptor

- CR

Cytokine Receptor

- JAK

Janus Kinase

- STAT

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription

- EAE

Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- Itk

IL-2-inducible T cell kinase

- Syk

Spleen tyrosine kinase

- CIA

Collagen-Induced Arthritis

- Btk

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase

- BCR

B Cell Receptor

- Lyp

Lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase

- Blk

B lymphocyte kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

A.A. declares receiving research funding from the 3M Corporation. S.S. and W.H. declare no commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abram CL, Roberge GL, Pao LI, Neel BG, & Lowell CA (2013). Distinct roles for neutrophils and dendritic cells in inflammation and autoimmunity in motheaten mice. Immunity, 38, 489–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acton A (2013). Autoimmune Diseases: New Insights for the Healthcare Professional: 2013 Edition In Autoimmune Diseases: New Insights for the Healthcare Professional: 2013 Edition (pp. 151–120): ScholarlyEditions, Atlanta, Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- Akinleye A, Chen Y, Mukhi N, Song Y, & Liu D (2013). Ibrutinib and novel BTK inhibitors in clinical development. J Hematol Oncol, 6, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO 3rd, et al. (2010). 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis, 69, 1580–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti AH, Schwartzberg PL, Joseph RE, & Berg LJ (2010). T-cell signaling regulated by the Tec family kinase, Itk. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2, a002287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird AM, Gerstein RM, & Berg LJ (1999). The role of cytokine receptor signaling in lymphocyte development. Curr Opin Immunol, 11, 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoya SK, Lam B, Lau K, & Larkin J 3rd. (2013). Th17 cells in immunity and autoimmunity. Clin Dev Immunol, 2013, 986789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begovich AB, Carlton VE, Honigberg LA, Schrodi SJ, Chokkalingam AP, Alexander HC, et al. (2004). A missense single-nucleotide polymorphism in a gene encoding a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet, 75, 330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste EN, Liu Y, McFarland BC, & Qin H (2014). Involvement of the janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway in multiple sclerosis and the animal model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Interferon Cytokine Res, 34, 577–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg LJ (2009). Strength of T cell receptor signaling strikes again. Immunity, 31, 529–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloudek LM, Makenbaeva D, & Eaddy M (2015). Anticipated Impact of Generic Imatinib Market Entry on the Costs of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Am Health Drug Benefits, 8, 472–480. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggon TJ, & Eck MJ (2004). Structure and regulation of Src family kinases. Oncogene, 23, 7918–7927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand DD, Latham KA, & Rosloniec EF (2007). Collagen-induced arthritis. Nat Protoc, 2, 1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright JJ, Du C, & Sriram S (1999). Tyrphostin B42 inhibits IL-12-induced tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of Janus kinase-2 and prevents experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol, 162, 6255–6262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn GL, Svensson L, Sanchez-Blanco C, Saini M, & Cope AP (2011). Why is PTPN22 a good candidate susceptibility gene for autoimmune disease? FEBS Lett, 585, 3689–3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Goods BA, Raddassi K, Nepom GT, Kwok WW, Love JC, et al. (2015). Functional inflammatory profiles distinguish myelin-reactive T cells from patients with multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med, 7, 287ra274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HH, Tai TS, Lu B, Iannaccone C, Cernadas M, Weinblatt M, et al. (2012). PTPN22.6, a dominant negative isoform of PTPN22 and potential biomarker of rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One, 7, e33067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HH, Tseng W, Cui J, Costenbader K, & Ho IC (2014). Altered expression of protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 22 isoforms in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther, 16, R14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles N, Hardwick D, Daugas E, Illei GG, & Rivera J (2010). Basophils and the T helper 2 environment can promote the development of lupus nephritis. Nat Med, 16, 701–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasset F, & Arnaud L (2018). Targeting interferons and their pathways in systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev, 17, 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis T, Najafian N, Benou C, Salama AD, Grusby MJ, Sayegh MH, et al. (2001). Effect of targeted disruption of STAT4 and STAT6 on the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Invest, 108, 739–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophi GP, Hudson CA, Gruber RC, Christophi CP, Mihai C, Mejico LJ, et al. (2008). SHP-1 deficiency and increased inflammatory gene expression in PBMCs of multiple sclerosis patients. Lab Invest, 88, 243–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SA, & Criswell LA (2007). PTPN22: its role in SLE and autoimmunity. Autoimmunity, 40, 582–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey G, Rani A, Betz A, Pak Y, Haberstock-Debic H, Pandey A, et al. (2017). PRT062607 Achieves Complete Inhibition of the Spleen Tyrosine Kinase at Tolerated Exposures Following Oral Dosing in Healthy Volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol, 57, 194–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SB, Tanaka Y, Mariette X, Curtis JR, Lee EB, Nash P, et al. (2017). Long-term safety of tofacitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis up to 8.5 years: integrated analysis of data from the global clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis, 76, 1253–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneth OBJ, Verstappen GMP, Paulissen SMJ, de Bruijn MJW, Rip J, Lukkes M, et al. (2017). Enhanced Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Activity in Peripheral Blood B Lymphocytes From Patients With Autoimmune Disease. Arthritis Rheumatol, 69, 1313–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay JS, Dallman MJ, Dayan AD, Martin A, & Mosedale B (1980). Immunisation against heterologous type II collagen induces arthritis in mice. Nature, 283, 666–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunkhorn S (2008). Type 1 diabetes: New link to kinases as targets. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 8, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aura Swanson C, Paniagua RT, Lindstrom TM, & Robinson WH (2009). Tyrosine kinases as targets for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 5, 317–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, James RG, Habib T, Singh S, Jackson S, Khim S, et al. (2013). A disease-associated PTPN22 variant promotes systemic autoimmunity in murine models. J Clin Invest, 123, 2024–2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsker JM, Hansen AM, & Caspi RR (2010). Th1 and Th17 cells: adversaries and collaborators. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1183, 211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoodi-Semiromi A, Wasserfall CH, Xia CQ, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Wabitsch M, Clare-Salzler M, et al. (2012). The tyrphostin agent AG490 prevents and reverses type 1 diabetes in NOD mice. PLoS One, 7, e36079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Puerta ML, Trinidad AG, Rodriguez Mdel C, de Pereda JM, Sanchez Crespo M, Bayon Y, et al. (2013). The autoimmunity risk variant LYP-W620 cooperates with CSK in the regulation of TCR signaling. PLoS One, 8, e54569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dendrou CA, Fugger L, & Friese MA (2015). Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol, 15, 545–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, & Tsao BP (2014). Advances in lupus genetics and epigenetics. Curr Opin Rheumatol, 26, 482–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close DR, et al. (2004). Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med, 350, 2572–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egwuagu CE (2009). STAT3 in CD4+ T helper cell differentiation and inflammatory diseases. Cytokine, 47, 149–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-behi M, Rostami A, & Ciric B (2010). Current views on the roles of Th1 and Th17 cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol, 5, 189–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann M, Brennan FM, & Maini RN (1996). Rheumatoid arthritis. Cell, 85, 307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann M, & Maini RN (2001). Anti-TNF alpha therapy of rheumatoid arthritis: what have we learned? Annu Rev Immunol, 19, 163–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Petraglia AL, Chen M, Byskosh PV, Boos MD, & Reder AT (2002). Low expression of interferon-stimulated genes in active multiple sclerosis is linked to subnormal phosphorylation of STAT1. J Neuroimmunol, 129, 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisullo G, Nociti V, Iorio R, Patanella AK, Marti A, Caggiula M, et al. (2008). IL17 and IFNgamma production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from clinically isolated syndrome to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Cytokine, 44, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhriman JM, Winge MCG, Haberstock-Debic H, Funk JO, Bradshaw JM, & Marinkovich MP (2018). ITK and RLK Inhibitor PRN694 Improves Skin Disease in Two Mouse Models of Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol, 138, 864–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto M, Serada S, Mihara M, Uchiyama Y, Yoshida H, Koike N, et al. (2008). Interleukin-6 blockade suppresses autoimmune arthritis in mice by the inhibition of inflammatory Th17 responses. Arthritis Rheum, 58, 3710–3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillooly KM, Pulicicchio C, Pattoli MA, Cheng L, Skala S, Heimrich EM, et al. (2017). Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor BMS-986142 in experimental models of rheumatoid arthritis enhances efficacy of agents representing clinical standard-of-care. PLoS One, 12, e0181782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gocek E, Moulas AN, & Studzinski GP (2014). Non-receptor protein tyrosine kinases signaling pathways in normal and cancer cells. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci, 51, 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Puerta JA, & Mocsai A (2013). Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Top Med Chem, 13, 760–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Rodriguez J, Sahu N, Handon R, Davidson TS, Anderson SM, Kirby MR, et al. (2009). Differential expression of interleukin-17A and −17F is coupled to T cell receptor signaling via inducible T cell kinase. Immunity, 31, 587–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Rodriguez J, Wohlfert EA, Handon R, Meylan F, Wu JZ, Anderson SM, et al. (2014). Itk-mediated integration of T cell receptor and cytokine signaling regulates the balance between Th17 and regulatory T cells. J Exp Med, 211, 529–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow CC (1996). Balancing immunity and tolerance: deleting and tuning lymphocyte repertoires. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 93, 2264–2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasis JA, & Tsoukas CD (2011). Itk: the rheostat of the T cell response. J Signal Transduct, 2011, 297868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh CJ, & Hilton DJ (2001). Negative regulation of cytokine signaling. J Leukoc Biol, 70, 348–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu JJ, Ryu JR, & Pendergast AM (2009). Abl tyrosine kinases in T-cell signaling. Immunol Rev, 228, 170–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haak S, Croxford AL, Kreymborg K, Heppner FL, Pouly S, Becher B, et al. (2009). IL-17A and IL-17F do not contribute vitally to autoimmune neuro-inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest, 119, 61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid KM, Isiyaku A, Kalgo MU, Yahaya IS, & Mirshafiey A (2017). JAK-STAT Lodges in Multiple Sclerosis: Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Approach Overview. OALib, 04, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hantschel O, Rix U, Schmidt U, Burckstummer T, Kneidinger M, Schutze G, et al. (2007). The Btk tyrosine kinase is a major target of the Bcr-Abl inhibitor dasatinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104, 13283–13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantschel O, & Superti-Furga G (2004). Regulation of the c-Abl and Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 5, 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa K, Martin F, Huang G, Tumas D, Diehl L, & Chan AC (2004). PEST domain-enriched tyrosine phosphatase (PEP) regulation of effector/memory T cells. Science, 303, 685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Muller-Newen G, Schaper F, & Graeve L (1998). Interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling through the gp130/Jak/STAT pathway. Biochem J, 334 (Pt 2), 297–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs ML, Tarlinton DM, Armes J, Grail D, Hodgson G, Maglitto R, et al. (1995). Multiple defects in the immune system of Lyn-deficient mice, culminating in autoimmune disease. Cell, 83, 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Jeong AR, Kannan AK, Huang L, & August A (2014). IL-2-inducible T cell kinase tunes T regulatory cell development and is required for suppressive function. J Immunol, 193, 2267–2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard SR, & Till JH (2000). Protein tyrosine kinase structure and function. Annu Rev Biochem, 69, 373–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal N, & Iqbal N (2014). Imatinib: a breakthrough of targeted therapy in cancer. Chemother Res Pract, 2014, 357027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie-Sasaki J, Sasaki T, Matsumoto W, Opavsky A, Cheng M, Welstead G, et al. (2001). CD45 is a JAK phosphatase and negatively regulates cytokine receptor signalling. Nature, 409, 349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Murai K, Yamaguchi K, Miyagishima T, Shindo M, Ogawa K, et al. (2016). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dasatinib in the chronic phase of newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 72, 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomaki P, Junttila I, Vidqvist KL, Korpela M, & Silvennoinen O (2015). The activity of JAK-STAT pathways in rheumatoid arthritis: constitutive activation of STAT3 correlates with interleukin 6 levels. Rheumatology (Oxford), 54, 1103–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakkula E, Leppa V, Sulonen AM, Varilo T, Kallio S, Kemppinen A, et al. (2010). Genome-wide association study in a high-risk isolate for multiple sclerosis reveals associated variants in STAT3 gene. Am J Hum Genet, 86, 285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakus Z, Simon E, Balazs B, & Mocsai A (2010). Genetic deficiency of Syk protects mice from autoantibody-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum, 62, 1899–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson L, & Holmdahl R (1993). Genes on the X chromosome affect development of collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol, 94, 459–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju JH, Heo YJ, Cho ML, Jhun JY, Park JS, Lee SY, et al. (2012). Modulation of STAT-3 in rheumatoid synovial T cells suppresses Th17 differentiation and increases the proportion of Treg cells. Arthritis Rheum, 64, 3543–3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan AK, Kim DG, August A, & Bynoe MS (2015). Itk signals promote neuroinflammation by regulating CD4+ T-cell activation and trafficking. J Neurosci, 35, 221–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsarou A, Gudbjornsdottir S, Rawshani A, Dabelea D, Bonifacio E, Anderson BJ, et al. (2017). Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 3, 17016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay J, & Calabrese L (2004). The role of interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford), 43 Suppl 3, iii2–iii9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebir H, Ifergan I, Alvarez JI, Bernard M, Poirier J, Arbour N, et al. (2009). Preferential recruitment of interferon-gamma-expressing TH17 cells in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol, 66, 390–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]