Abstract

Objective

Childbirth is suggested to be associated with elevated levels of sickness absence (SA) and disability pension (DP). However, detailed knowledge about SA/DP patterns around childbirth is lacking. We aimed to compare SA/DP across different time periods among women according to their childbirth status.

Design

Register-based longitudinal cohort study.

Setting

Sweden.

Participants

Three population-based cohorts of nulliparous women aged 18–39 years, living in Sweden 31 December 1994, 1999 or 2004 (nearly 500 000/cohort).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Sum of SA >14 and DP net days/year.

Methods

We compared crude and standardised mean SA and DP days/year during the 3 years preceding and the 3 years after first childbirth date (Y−3 to Y+3), among women having (1) their first and only birth during the subsequent 3 years (B1), (2) their first birth and at least another delivery (B1+), and (3) no childbirths during follow-up (B0).

Results

Despite an increase in SA in the year preceding the first childbirth, women in the B1 group, and especially in B1+, tended to have fewer SA/DP days throughout the years than women in the B0 group. For cohort 2005, the mean SA/DP days/year (95% CIs) in the B0, B1 and B1+ groups were for Y−3: 25.3 (24.9–25.7), 14.5 (13.6–15.5) and 8.5 (7.9–9.2); Y−2: 27.5 (27.1–27.9), 16.6 (15.5–17.6) and 9.6 (8.9–10.4); Y−1: 29.2 (28.8–29.6), 31.4 (30.2–32.6) and 22.0 (21.2–22.9); Y+1: 30.2 (29.8–30.7), 11.2 (10.4–12.1) and 5.5 (5.0–6.1); Y+2: 31.7 (31.3–32.1), 15.3 (14.2–16.3) and 10.9 (10.3–11.6); Y+3: 32.3 (31.9–32.7), 18.1 (17.0–19.3) and 12.4 (11.7–13.0), respectively. These patterns were the same in all three cohorts.

Conclusions

Women with more than one childbirth had fewer SA/DP days/year compared with women with one childbirth or with no births. Women who did not give birth had markedly more DP days than those giving birth, suggesting a health selection into childbirth.

Keywords: sick leave, disability pension, childbirth, cohort study, postpartum, pregnancy, child delivery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study involved longitudinal analyses of both sickness absence and disability pension.

It was population based, we included virtually all nulliparous women in Sweden during the study periods.

By analysing three cohorts of women 5 years apart we explored potential time-period effects.

Since we used large, nationwide data, statistical precision in our analyses was high.

We had no information on sickness absence spells ≤14 days.

Background

In many countries with high labour force participation of women, women have higher levels of sickness absence (SA) and disability pension (DP) than men.1–4 One suggestion to explain this gender difference focuses on SA during pregnancy and after childbirth.5–8 Also for DP, pregnancy has been suspected to be a factor behind this gender gap, although findings are less consistent than for SA.8 Swedish studies have shown that women have higher SA during pregnancy, as well as during the years following childbirth, as compared with other years.5 6 9 10 Yet, it is unclear whether women have elevated rates of SA also during the years preceding their first childbirth. Findings from twin studies have shown that women who gave birth had lower average number of SA days compared with their nulliparous twin sisters.5 10 11 After delivery the average number of SA days was similar in both groups. However, few studies have focused on SA and DP in different groups of women; most have focused on gender differences.

Pregnancy and the postpartum period are characterised by important alterations in endocrine, metabolic, immune and cardiovascular function.12 13 Changes in immunity in pregnancy may result in higher maternal susceptibility to certain common infectious diseases and in diminished immune responses. This could lead to more severe disease courses in pregnancy than in the non-pregnant state and consequently to longer SA spells. Similarly, while women’s conditions with certain autoimmune diseases improve during pregnancy and may deteriorate after delivery, for others there is a deterioration or no change during gestation.14 Also, women with a genetic vulnerability or certain risk factors may experience pregnancy-induced hypertension/pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, peripartum and postpartum thrombotic events, or peripartum and postpartum psychiatric disorders. Several of these conditions reverse shortly after delivery/the postpartum period, but may reappear later in vulnerable women and result in SA or DP.13 Women with in vitro fertilisation may have increased SA also in the time preceding conception.

Regarding SA, a Norwegian study found that the higher SA risk in women in the years after pregnancy disappeared when SAs during subsequent pregnancies were accounted for.15 However, this study included mothers only and no information on DP was included, which means that long-term or permanent reductions in work capacity were not accounted for.

The mean age for first childbirth, and the prevalence of several maternal chronic diseases, of obesity and in vitro fertilisation have increased over the past decades, which may contribute to an increase in rates over time of certain complications related to pregnancy and childbirth6 16 17 and subsequently higher SA rates during and shortly after pregnancy.

It has also been argued that the combination of paid and unpaid work could be one reason for women having higher levels of SA and DP than men.18–20 However, other findings have reported a positive association between multiple roles and health and well-being, respectively.21 22 One exception is single mothers, for whom DP levels according to a Swedish study are higher than for married or cohabiting mothers, a difference that increases with the number of children.23

There might also be a positive health selection into giving birth, where women not giving birth may have poorer health and thus are unable to, or choose not to give birth.5 10 11 However, with these three studies having included twins only, the generalisability to the general population is unclear.

Our aim was to gain knowledge on SA and DP over time in women, in relation to childbirth while accounting for period effects. Specifically, we wanted to compare annual mean net days of SA and DP among women giving and not giving birth, covering a period of 3 years before and after childbirth. As both childbirth and age are associated with socioeconomic position, another aim was to examine if the association between childbirth and SA/DP varied between age groups.

Methods

Longitudinal population-based cohort studies were conducted. We created three different population-based cohorts using the unique personal identity number assigned to all residents in Sweden for linkage of microdata from five Swedish nationwide registers, from the following three authorities24:

From Statistics Sweden: the Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labor Market Studies (LISA) regarding sociodemographic information, year of immigration and emigration.25

From the National Board of Health and Welfare: (1) the Medical Birth Register (MBR) for dates of childbirth and parity. This register covers 97%–99% of all births in Sweden since 197317; (2) the National In-Patient Register for information since 1964 on childbirths not found in the MBR.26 We used main or secondary diagnoses related to childbirth (as defined by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD): ICD-7: 660, 670–678; ICD-8: 650–662; ICD-9: 650, 651, 652, 659X, W/659.W–659.X, 669.E,F,G,H,W,X; ICD-10: O75.7–O75.9, O80–84). If a delivery appeared in both registers, the date from the MBR was used; (3) the Causes of Death Register for date of death.

From the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, information from their register Micro Data for Analysis of Social Insurance on SA and DP (start and end dates and extent) for the period 1994–2008.27 Only SA spells >14 days were included.

In Sweden, all individuals aged 16 years or older with income from work, unemployment benefits or parental leave benefits, as well as students are entitled to SA benefits from the public sickness insurance system, if their disease or injury is so severe that it has led to work incapacity in relation to ordinary work duties. There is one waiting day and a physician certificate is needed from day 8. For employees, sick pay is paid by the employer during the first 14 days of an SA spell. People aged 19–64 who, due to disease or injury, have a long-term or permanently reduced work capacity can be granted DP. Both SA and DP can be granted for full time or part-time (25%, 50% or 75%) of ordinary work hours. Approximately 80% of the lost income, up to a certain limit, is covered by SA benefits, while DP covers up to 65%. If on parental leave at the time of disease or injury, the parent may receive SA benefits (instead of parental leave benefits) in circumstances that involve hospital care or if due to the morbidity he/she cannot take care of the child. Women on full or partial DP before giving birth remain on DP also after giving birth. Parents can stay home to care for a sick child for 60 days/year/child, with benefits at the same level as SA. There is no waiting day. The number of days can be prolonged in the case of severe disease of the child (eg, cancer).

Cohorts

We created three cohorts (Cohort1995, Cohort2000, Cohort2005) of all women living in Sweden and aged 18–39 years on 31 December 1994, 1999 or 2004, respectively, using the LISA register. To study SA and DP during the 3 years prior to 3 years after first child delivery date (T0), and to allow comparisons with women not having any births during this period, we only included women who resided in Sweden during the 3 years prior to the respective inclusion year. To handle that the outcome (SA/DP) might be influenced by a new pregnancy, all women were followed up also for a new childbirth in the 43 weeks after Y+3. For each cohort, we identified three groups of women:

B0: Women having no childbirths registered neither before nor during the follow-up.

B1: Women having their first childbirth during the index year and no additional births registered during the follow-up.

B1+: Women having their first childbirth during the index year and at least one more birth during the follow-up.

Thus, all women with a childbirth prior to the index year (1995, 2000 or 2005) were excluded. For the women in B0, T0 was set to 2 July of each index year.

Outcome

We calculated the number of annual mean net SA and DP days for each of the 3 years preceding T0 and the 3 years after, for each cohort, respectively. However, as data on SA and DP were only available from 1994, only 1 year prior to T0 was considered for Cohort1995. Part-time SA/DP days were combined, for example, 2 days of half-time SA or DP was counted as 1 net day.

Sociodemographics

The following covariates were included: age (categorised into four groups: 18–24, 25–29, 30–34 and 35–39 years), country of birth (Sweden, other Scandinavian country, other European Union 25 countries and rest of the world), type of living area (based on the H-classification scheme20), categorised as: large city (Stockholm, Gothenburg, Malmö); medium-sized city (≥90 000 inhabitants); and small city/village (<90 000 inhabitants), family situation (married/cohabitant and single) and educational level (categorised as elementary (≤9 years), high school (10–12 years) and university/college (>12 years)). These variables were obtained from the LISA register and were measured on 31 December 1994, 1999 and 2004, respectively.

Statistical analyses

We calculated annual mean numbers of net SA and DP days, starting 3 years preceding the date of the first childbirth (Y−3) until 3 years after (Y+3) for the three comparison groups (B0, B1, B1+) within each cohort. Both crude and standardised mean numbers of net days were calculated. We used a direct standardisation using Cohort2005 as the standard population. In the standardisation, all sociodemographic variables were taken into account: age (in four categories), country of birth, place of residence, educational level and family status (as binary). Women who died or emigrated within 3 years after child delivery were excluded from the analyses from the year after death or emigration.

Further, for Cohort2005, we calculated the proportion of all women who had DP or at least one SA spell >14 days, respectively, and also the proportion of women with SA among those who had no DP.

As age is strongly associated with both SA/DP and childbirth,6 we also performed analyses stratified by age for Cohort2005, calculating 95% CIs for the means of the sums of SA and DP net days. All analyses were conducted using SAS V.9.4.

Patient and public involvement

The study participants or the general public were not involved in decisions about the research question, the design of the study, the outcomes, the conduct of the study, the drafting of the paper, nor in the dissemination of the study results.

Results

In all three cohorts, 92%–93% of the women had no childbirths, that is, they belonged to the group B0 (table 1). Around 13 000–15 000 women had had their first childbirth during the index year (3%) but no more births during the study period, that is, belonged to group B1. About 21 000–25 000 women belonged to B1+, that is, had their first delivery during the index year and at least one additional childbirth during follow-up (4%–5%). Women in B0 were younger (18–24 years), had lower educational level and were to a higher extent single. A lower rate of women in B1+ were in the oldest age group (ie, 35–39 years), as compared with women in B0 and B1. Furthermore, women in group B1+ were more likely to have higher education and to be married or cohabiting than those in B0 and B1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the three cohorts of women, by cohort and childbirth group

| Cohort 1995 (n=486 628) (%) | Cohort 2000 (n=490 878) (%) | Cohort 2005 (n=492 504) (%) | |||||||

| B0 | B1 | B1+ | B0 | B1 | B1+ | B0 | B1 | B1+ | |

| n | 450 630 | 15 096 | 20 902 | 455 962 | 13 569 | 21 347 | 453 532 | 14 299 | 24 673 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 18–24 | 58.1 | 36.2 | 35.3 | 55.4 | 29.4 | 25.6 | 56.7 | 25.8 | 21.4 |

| 25–29 | 19.9 | 35.5 | 43.7 | 21.6 | 36.0 | 46.2 | 20.4 | 32.1 | 42.0 |

| 30–34 | 11.9 | 20.1 | 17.7 | 12.4 | 24.4 | 23.8 | 12.4 | 28.6 | 30.9 |

| 35–39 | 10.1 | 8.2 | 3.3 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 4.4 | 10.5 | 13.5 | 5.8 |

| Country of birth | |||||||||

| Sweden | 90.5 | 91.1 | 94.0 | 89.0 | 88.2 | 93.0 | 87.6 | 86.6 | 91.5 |

| Other Scandinavian country | 2.2 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| Other EU-25 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| Rest of the world | 5.7 | 5.0 | 3.5 | 8.1 | 8.8 | 5.0 | 9.7 | 10.5 | 6.5 |

| Type of living area | |||||||||

| Large cities | 41.7 | 39.7 | 37.0 | 43.3 | 41.6 | 41.4 | 43.4 | 43.8 | 44.1 |

| Medium-sized cities | 34.9 | 34.9 | 35.4 | 35.1 | 34.5 | 34.2 | 35.7 | 33.7 | 34.2 |

| Small cities/village | 23.4 | 25.4 | 27.6 | 21.7 | 23.9 | 24.4 | 20.9 | 22.5 | 21.8 |

| Educational level | |||||||||

| Elementary school (≤9 years) | 19.4 | 15.3 | 9.2 | 21.9 | 18.5 | 9.6 | 20.0 | 12.7 | 7.1 |

| High school (10–12 years) | 57.2 | 60.0 | 57.3 | 49.5 | 52.7 | 48.1 | 45.9 | 47.2 | 38.6 |

| University/college (≥13 years) | 23.4 | 24.7 | 33.5 | 28.6 | 28.8 | 42.3 | 34.1 | 40.1 | 54.3 |

| Family situation | |||||||||

| Married or cohabitant | 6.0 | 22.0 | 28.7 | 5.1 | 22.3 | 29.2 | 4.5 | 22.5 | 27.7 |

| Single | 94.0 | 78.0 | 71.3 | 94.9 | 77.7 | 70.8 | 95.5 | 77.5 | 72.3 |

B0, no childbirth during follow-up; B1, first childbirth during index year (at date T0) of each cohort and no more children during follow-up; B1+, first childbirth at T0 and at least one more during follow-up; EU-25, European Union 25.

For Cohort2005, women in B1 had the highest proportion of SA/DP combined during Y-3 to Y-1, as well as the highest proportion of SA between Y−3 and Y+1, while B1+ had both highest proportion of SA/DP combined and SA the other years (table 2). The highest proportions of women on DP were found for B0 during all years, ranging from 3.4% to 5.8%. Among DP recipients, the proportion on part-time DP was lowest in B0 and highest in B1+ (table 2). Among SA recipients, women in B1+ were more likely to have shorter SA spells than women in B0 or B1+ (table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of women with a sickness absence spell >14 days and disability pension during the 6 different years before and after childbirth, for Cohort2005, by childbirth group

| Year | Childbirth group | Total study population | Of DP recipients, received DP | Of SA recipients, received SA for a period of | |||||||

| n | SA/DP* (%) |

DP* (%) |

SA† (%) |

Part of the year (%) |

All year (%) |

>0–30 days (%) |

>30–90 days (%) |

>90–180 days (%) |

>180 days (%) |

||

| Y−3 | B0 | 453 532 | 9.5 | 3.4 | 6.6 | 26.8 | 73.2 | 40.0 | 22.8 | 13.6 | 23.6 |

| B1 | 14 299 | 12.6 | 1.4 | 11.6 | 53.8 | 46.2 | 43.1 | 22.6 | 14.9 | 19.4 | |

| B1+ | 24 673 | 8.9 | 0.5 | 8.6 | 63.4 | 36.6 | 51.0 | 24.0 | 12.7 | 12.3 | |

| Y−2 | B0 | 453 532 | 9.5 | 3.9 | 6.2 | 24.3 | 75.7 | 34.2 | 23.3 | 14.8 | 27.7 |

| B1 | 14 299 | 12.7 | 2.0 | 11.4 | 52.8 | 47.2 | 40.8 | 22.3 | 14.1 | 22.8 | |

| B1+ | 24 673 | 8.6 | 0.7 | 8.1 | 60.9 | 39.1 | 45.7 | 25.5 | 13.8 | 14.9 | |

| Y−1 | B0 | 453 532 | 10.3 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 25.5 | 74.5 | 36.3 | 23.6 | 15.3 | 24.8 |

| B1 | 14 299 | 36.2 | 2.4 | 35.0 | 44.7 | 55.3 | 37.8 | 36.9 | 15.8 | 9.5 | |

| B1+ | 24 673 | 30.6 | 0.8 | 30.2 | 50.8 | 49.2 | 45.4 | 35.8 | 13.3 | 5.6 | |

| Y+1 | B0 | 453 532 | 11.1 | 5.0 | 6.9 | 25.5 | 74.5 | 41.1 | 23.2 | 13.9 | 21.9 |

| B1 | 14 299 | 10.7 | 2.4 | 8.7 | 36.2 | 63.8 | 61.5 | 22.5 | 8.4 | 7.7 | |

| B1+ | 24 673 | 6.8 | 0.8 | 6.1 | 49.7 | 50.3 | 67.9 | 20.2 | 6.5 | 5.4 | |

| Y+2‡ | B0 | 448 921 | 11.8 | 5.4 | 7.3 | 26.5 | 73.5 | 43.1 | 22.6 | 13.7 | 20.6 |

| B1 | 14 270 | 10.7 | 2.6 | 8.7 | 37.1 | 62.9 | 44.1 | 21.5 | 14.1 | 20.3 | |

| B1+ | 24 671 | 15.1 | 0.8 | 14.5 | 45.4 | 54.6 | 50.4 | 33.4 | 11.7 | 4.6 | |

| Y+3‡ | B0 | 443 320 | 12.0 | 5.8 | 7.1 | 27.1 | 72.9 | 43.7 | 23.1 | 13.2 | 20.0 |

| B1 | 14 183 | 12.7 | 2.9 | 10.6 | 43.0 | 57.0 | 44.7 | 20.9 | 13.2 | 21.1 | |

| B1+ | 24 667 | 19.1 | 0.8 | 18.5 | 47.5 | 52.5 | 50.8 | 34.7 | 11.0 | 3.5 | |

*Having DP was defined as 1 ≤DP net annual days ≤364.

†SA spell >14 days after excluding those with full-time DP.

‡Numbers of women in Y+2 and Y+3 are lower due to the fact that some died or emigrated during these years.

DP, disability pension; SA, sickness absence.

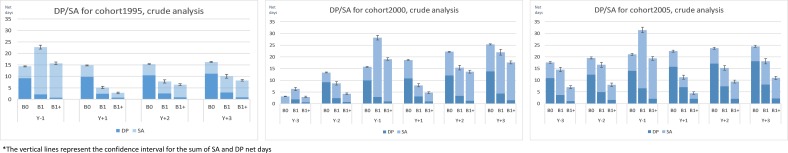

Comparing crude annual mean net SA and DP days, we found a similar pattern regardless of cohort (figure 1). Group B0 had the highest mean SA/DP days combined, followed by group B1 and group B1+. The only exception to this was year Y−1, that is, the year of the first pregnancy for B1 and B1+, when group B0 had the lowest crude number of combined SA and DP days. During all years, the largest difference was found in DP days, where women with no childbirths had up to 10 times the number of DP days as compared with women in group B1+.

Figure 1.

Crude mean annual net days of sickness absence (SA) and disability pension (DP) from Y−3 to Y+3, in Cohort1995, Cohort2000 and Cohort2005, respectively, by childbirth group.

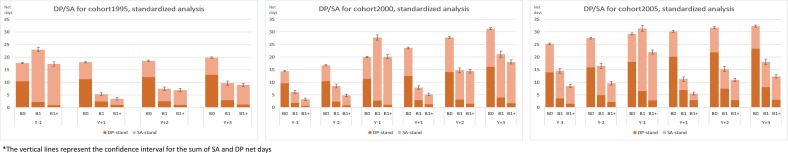

The standardised mean number of combined SA/DP days showed similar patterns for the three different cohorts (figure 2). Women with no childbirths (B0) had the highest number of SA/DP days at all years except at Y−1, when B1 had the highest number of SA/DP days, followed by group B1+. Also for standardised number of days, the largest differences were seen for DP. Regardless of year, women in B0 had 3–10 times more DP days than did the other groups. SA days were more evenly spread. In Cohort2005 during Y-3 and Y-2 group B0 and group B1 had similar number of mean SA days (11.3; 10.9 and 11.6; 11.6, respectively). Women with at least one additional childbirth had fewer mean SA days, 7.0 and 7.5 SA days at Y−3 and Y−2. The pattern for the association between childbirth and SA/DP was largely similar across cohorts. There was also an increase in SA and DP over time in all groups.

Figure 2.

Standardised mean annual net days of sickness absence (SA) and disability pension (DP) from Y−3 to Y+3 in Cohort1995, Cohort2000 and Cohort2005, respectively, by childbirth group.

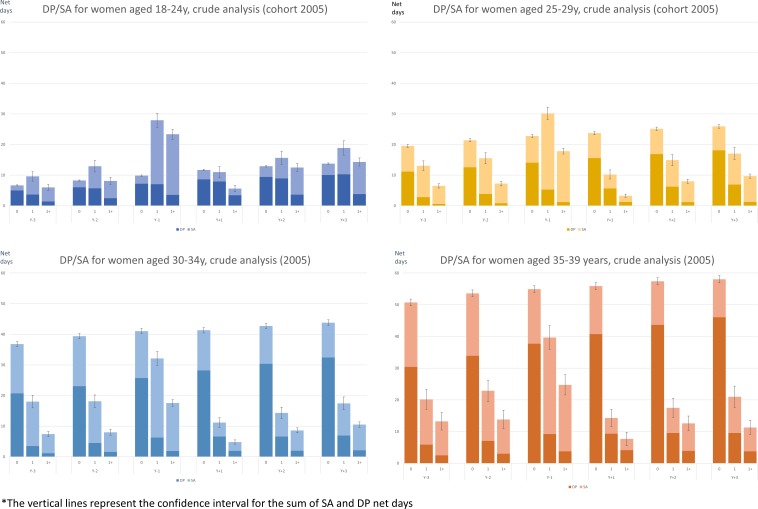

In the age-stratified analyses for Cohort2005, we found that the youngest women (18–24 years) in B1 had the highest mean SA and DP days, whereas B0 women had the lowest mean number of corresponding days (figure 3). Still, B0 women had slightly more DP days, regardless of year. In the other age groups, B0 women had most DP days during all years, as compared with B1 and B1+, while women in B1+ had the lowest number of SA days during all years, except during Y−1. Women aged 30–39 in B0 had the highest mean SA and DP days, regardless of year. Their combined mean number of SA/DP days varied between 50 and 60, whereas the range was 30–40 in group B1 and 8–25 in B1+.

Figure 3.

Crude mean annual net days of sickness absence (SA) and disability pension (DP) from Y−3 to Y+3 in Cohort2005, by age group and childbirth group.

Discussion

In this exploratory population-based study using three cohorts from different time periods, we found that women who had no childbirths had up to 10 times higher rates of DP than their counterparts who gave at least one birth, regardless of cohort and year studied. Women having one additional, subsequent childbirth during follow-up tended to have fewer days of combined SA and DP than women having no childbirths. The findings suggest no period effects regarding the linkages between childbirth and the investigated outcomes.

Our finding that women with no childbirths had higher levels of DP is in line with those of a Swedish study of twins up to 10 years after childbirth, which reported that the number of DP days was significantly higher in women not giving birth than in their twin sisters who did.10 Further, that twin study found that except for the year of childbirth, the number of mean annual SA days (for SA spells >14 days) was similar among women giving birth and those who did not. Our study showed similar results, except that women who had more than one childbirth had slightly fewer mean SA days than the other two groups of women.

Women with poor health or other characteristics associated with adverse health may decide against going through a pregnancy.19 21 This may be part of the explanation for the substantially higher levels of DP among women with no childbirths in our study, that is, a positive health selection into giving birth or into having more than one birth is likely, as has been suggested by others.10 However, with improvements in medical care, more women with severe diseases who earlier had to refrain from pregnancy due to disease might now choose otherwise. In line with the above-mentioned results, a Swedish twin study also indicated a health selection into giving birth.11 It also emphasised their findings regarding multiple hospitalisations before subsequent DP. Future studies with good measures of morbidities (eg, in terms of specific medical diagnoses) are needed to more closely investigate the health selection mechanisms into childbirth.

In our study, women aged 30 years or more, with no childbirths, had higher mean SA days than those with one or more childbirths. The mean number of DP days was higher in all age groups among women with no childbirths. These findings indicate that the hypothesis of that childbirth leads to more SA28 strongly can be questioned and that information of DP is also warranted in studies of SA in women with and without children.

We found that women having a subsequent childbirth during the follow-up (B1+) had—except for the year before delivery—fewer days of both SA and DP up until Y+1 than B0 or B1 did, but from Y+2 the levels were closer to those in B1, an increase possibly due to a new pregnancy. This is in accordance with a Norwegian study reporting that the higher SA risk in women in the years after pregnancy disappeared, when SAs during subsequent pregnancies were accounted for.15 As expected, those who gave birth had lower SA in the year after childbirth (Y+1) as most women are on parental leave for at least some months in that year.28 Even if it is possible to claim SA benefits also when on parental leave, this is not usual, unless the morbidity leads to not being able to care for the child.

When we analysed period effects, our results indicated similar patterns between the three exposure groups regardless of cohort. Nevertheless, the levels of SA/DP combined increased in a graded manner from Cohort1995 to Cohort2000 and were highest in Cohort2005. Our data did not allow to investigate the reasons for the increasing SA/DP time trends, but we speculate that among childbearing women potential explanations may be related to the increase in age at first childbirth, the better medical care thanks to which women with severe conditions who earlier refrained from now can engage in pregnancy, as well as better possibilities to remain in paid work during pregnancy. Nevertheless, the fact that the SA/DP levels increased over time also among women not giving birth may suggest that factors not related to childbearing and childrearing may also be important, for example, changes in mental disorder rates at the population level, in possibilities to combine paid and unpaid work and to remain in employment with certain medical conditions, in physicians’ sick-listing practices and in rules or practices concerning SA and DP at the Social Insurance Agency. Furthermore, there have been extensive changes in Swedish work-life since the 1990s, as in other Western countries. More organisational instability and downsizing accompanied by a higher prevalence of adverse psychosocial work situations have increased the work demands in ways that can interfere with work and family life balance, potentially increasing SA/DP over time.29–31

The strengths of this study include its population-based and longitudinal design, and the use of high-quality and nationwide register data with high completeness, validity and no dropouts.24 The use of National Patient Register data in addition to the MBR allowed us to include childbirths not captured by the MBR. Furthermore, we were able to account for factors related both to the occurrence of SA/DP and childbirth such as maternal age, educational level and type of living area by means of a standardised analysis taking these variables into account. Another strength is related to characteristics of the Swedish labour market and public insurance system, that is, high employment rates among women32 (ie, low health selection bias) and a public sickness insurance covering basically the whole population. However, two study limitations warrant consideration in contextualising the present results. First, women who had only given birth outside of Sweden would not appear in the registers and may thus be incorrectly categorised as not having had any childbirth. This may result in differential misclassification of exposure, and biased levels of SA/DP in women having no childbirths. To mitigate this, and to make sure we had information on their possible SA/DP, residency in Sweden for at least 3 years prior to childbirth was an inclusion criterion. We had no information on SA spells <15 days, this can be considered both a limitation and a strength. The shorter SA spells only represent a limited number of all SA days, and most are self-reported and not verified by any physician certificate.33 The underestimation of the mean yearly SAs is more likely to affect women who gave birth than those who did not since small children are vulnerable to infections and their parents are likely to catch these; nevertheless, parents probably choose the very generous social benefits for caring for sick children if they were sick at the same time as the child. We had no information on if and in that case how much the women in the three groups were in paid work, studying, or on different types of parental leave during the studied years.

In conclusion, women who had more than one childbirth had—except for the year before delivery—lower rates and fewer days of both SA and DP, than women with one childbirth only and women not giving birth. Further, women not giving birth had markedly more DP days than women who gave birth. These findings are suggestive of a health selection into childbirth. No period effects in the association between childbirth and these outcomes were detected. High levels of SA and DP among parous women appear to be mainly restricted to pregnancy. DP should also be included in studies of SA in relation to childbirth.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CB conducted the analyses, wrote the first draft and revised the paper. CO contributed to analyses and revised the paper. KDL contributed to writing, interpretation of the findings and revised the paper. PS and KA contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the findings and revised the paper. MV, UL and PL contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of the findings and revised the paper. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the AFA Insurance (grant number 160318).

Disclaimer: The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, or analysis of the data, interpretation of the results, writing of the paper nor in decisions about the manuscript submission.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The project was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Stockholm. The Ethical Review Board waived the requirement that informed consent of research subjects should be obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1. Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Swedish Council on technology assessment in health care (SBU). Chapter 1. Aim, background, key concepts, regulations, and current statistics. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2004;63:12–30. 10.1080/14034950410021808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parrukoski S, Lammi Taskula J. Parental leave policies and the economic crisis in the Nordic countries. Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Svedberg P, Ropponen A, Alexanderson K, et al. Genetic susceptibility to sickness absence is similar among women and men: findings from a Swedish twin cohort. Twin Res Hum Genet 2012;15:642–8. 10.1017/thg.2012.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ugreninov E. Can Family Policy Reduce Mothers’ Sick Leave Absence? A Causal Analysis of the Norwegian Paternity Leave Reform. J Fam Econ Issues 2013;34:435–46. 10.1007/s10834-012-9344-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Björkenstam E, Alexanderson K, Narusyte J, et al. Childbirth, hospitalisation and sickness absence: a study of female twins. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006033 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brehmer L, Alexanderson K, Schytt E. Days of sick leave and inpatient care at the time of pregnancy and childbirth in relation to maternal age. Scand J Public Health 2017;45:222–9. 10.1177/1403494817693456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mastekaasa A. Sickness absence in female- and male-dominated occupations and workplaces. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:2261–72. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vistnes JP. Gender differences in days lost from work due to illness. ILR Review 1997;50:304–23. 10.1177/001979399705000207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kvinnors sjukfrånvaro- En studie av förstagångsföräldrar. [Women’s sick leave: a study of first-time parents] [in Swedish]; 2014.

- 10. Narusyte J, Björkenstam E, Alexanderson K, et al. Occurrence of sickness absence and disability pension in relation to childbirth: a 16-year follow-up study of 6323 Swedish twins. Scand J Public Health 2016;44:98–105. 10.1177/1403494815610051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Björkenstam E, Narusyte J, Alexanderson K, et al. Associations between childbirth, hospitalization and disability pension: a cohort study of female twins. PLoS One 2014;9:e101566 10.1371/journal.pone.0101566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Soma-Pillay P, Nelson-Piercy C, Tolppanen H, et al. Physiological changes in pregnancy. Cardiovasc J Afr 2016;27:89–94. 10.5830/CVJA-2016-021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williams D. Pregnancy: a stress test for life. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2003;15:465–71. 10.1097/00001703-200312000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adams Waldorf KM, Nelson JL. Autoimmune disease during pregnancy and the microchimerism legacy of pregnancy. Immunol Invest 2008;37:631–44. 10.1080/08820130802205886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rieck KME, Telle K. Sick leave before, during and after pregnancy. Acta Sociol 2013;56:117–37. 10.1177/0001699312468805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. OECD OECD family database. secondary OECD family database 2017, 2017. Available: http://www.oecd.org/social/family/database.htm [Accessed 30 Jun 2017].

- 17. The National Board of Health and Welfare The Swedish medical birth Register- a summary of content and quality. The Centre for Epidemiology: The National Board of Health and Welfare; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Åkerlind I, Alexanderson K, Hensing G, et al. Sex differences in sickness absence in relation to parental status. Scand J Soc Med 1996;24:27–35. 10.1177/140349489602400105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bratberg E, Dahl S-A RA. 'The double burden': do combinations of career and family obligations increase sickness absence among women? Eur Sociol Rev 2002;18:233–49. 10.1093/esr/18.2.233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rikets indelningar: Årsbok over regionala indelningar med koder, postadresser, telefonnummer m m. 2003 [Country classifications: Yearbook of regional classifications with codes, postal addresses, phone numbers, etc. 2003]. Stockholm; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mastekaasa A. Parenthood, gender and sickness absence. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1827–42. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00420-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Voss M, Floderus B, Diderichsen F. How do job characteristics, family situation, domestic work, and lifestyle factors relate to sickness absence? A study based on Sweden post. J Occup Environ Med 2004;46:1134–43. 10.1097/01.jom.0000145433.65697.8d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Floderus B, Hagman M, Aronsson G, et al. Disability pension among young women in Sweden, with special emphasis on family structure: a dynamic cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000840 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy A-KE, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:125–36. 10.1007/s10654-016-0117-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ludvigsson JF, Svedberg P, Olén O, et al. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;34:423–37. 10.1007/s10654-019-00511-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. The Swedish Social Insurance Agency MiDAS Sjukpenning och rehabiliteringspenning [The MiDAS register. Sickness absence benefits]; 2011.

- 28. Angelov N, Johansson P, Lindahl E. Sick of family responsibilities? Empir Econ 2018;63 10.1007/s00181-018-1552-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rostila M. The Swedish labour market in the 1990s: the very last of the healthy jobs? Scand J Public Health 2008;36:126–34. 10.1177/1403494807085067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lidwall U, Bergendorff S, Voss M, et al. Long-term sickness absence: changes in risk factors and the population at risk. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2009;22:157–68. 10.2478/v10001-009-0018-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bryngelson A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Fritzell J, et al. Reduction in personnel and long-term sickness absence for psychiatric disorders among employees in Swedish County councils: an ecological population-based study. J Occup Environ Med 2011;53:658–62. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31821aa706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Labour force surveys: fourth quarter 2017; 2017.

- 33. Hensing G, Alexanderson K, Allebeck P, et al. How to measure sickness absence? literature review and suggestion of five basic measures. Scand J Soc Med 1998;26:133–44. 10.1177/14034948980260020201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.