Abstract

Objectives

To describe and summarise how the results of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that did not find a significant treatment effect are reported, and to estimate how commonly trial reports make unwarranted claims.

Design

We performed a retrospective survey of published RCTs, published in four high impact factor general medical journals between June 2016 and June 2017.

Setting

Trials conducted in all settings were included.

Participants

94 reports of RCTs that did not find a difference in their main comparison or comparisons were included.

Interventions

All interventions.

Primary and secondary outcomes

We recorded the way the results of each trial for its primary outcome or outcomes were described in Results and Conclusions sections of the Abstract, using a 10-category classification. Other outcomes were whether confidence intervals (CIs) and p values were presented for the main treatment comparisons, and whether the results and conclusions referred to measures of uncertainty. We estimated the proportion of papers that made claims that were not justified by the results, or were open to multiple interpretations.

Results

94 trial reports (120 treatment comparisons) were included. In Results sections, for 58/120 comparisons (48.3%) the results of the study were re-stated, without interpretation, and 38/120 (31.7%) stated that there was no statistically significant difference. In Conclusions, 65/120 treatment comparisons (54.2%) stated that there was no treatment benefit, 14/120 (11.7%) that there was no significant benefit and 16/120 (13.3%) that there was no significant difference. CIs and p values were both presented by 84% of studies (79/94), but only 3/94 studies referred to uncertainty when drawing conclusions.

Conclusions

The majority of trials (54.2%) inappropriately interpreted a result that was not statistically significant as indicating no treatment benefit. Very few studies interpreted the result as indicating a lack of evidence against the null hypothesis of zero difference between the trial arms.

Keywords: clinical trials, reporting, statistics & research methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We surveyed every issue of four journals for a recent 12-month period; hence, the results are comprehensive and up to date.

This was not a systematic review, but was restricted to four high-impact general journals. This means that we cannot draw any conclusions about other publications.

Our classification system was developed by the authors and is not a validated tool.

We only looked at reporting in abstracts; in the main text of papers, authors may have made different and more accurate statements.

Introduction

Reports of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) usually attempt to draw conclusions about treatment effectiveness from their statistical analysis. It is common for results that pass a threshold for statistical significance, usually a p value of less than 0.05, to be interpreted as indicating a real and clinically important effect. ‘Non-significance’ (p>0.05) is often taken to mean that there is no difference between the treatments, or that the intervention is not effective. As has been pointed out many times, this is an erroneous conclusion.1 2 Failure to reach a conventional threshold for ‘statistical significance’ does not mean that it is safe to conclude that there is no difference. Every statistical test has a type II error rate, which is the probability of obtaining a non-significant result, if the null hypothesis is false (there really is a difference). Trials are often designed with a 20% type II error rate (80% power), for a true treatment effect of a specified size. With such a design, even if the true treatment effect is exactly as assumed (and designs often assume unrealistically large treatment effects), non-significance would be expected 20% of the time, and a conclusion of no difference would be wrong. Moreover, common issues such as fewer recruits than expected, more variability, or a lower incidence of outcomes, will reduce power and make non-significant results more likely, even if in reality there is a real and important treatment effect. There is no way of discriminating between non-significant results that derive from chance or lack of power, and those that derive from a true lack of treatment benefit, except by more research.

Misinterpretation of non-significant results in clinical trials may be particularly damaging, because trials provide high-quality evidence, and their results often determine clinical guidelines and practice. Erroneous conclusions of ineffectiveness may result in non-adoption or abandonment of treatments that could actually be beneficial, and the existence of an apparently ‘definitive’ trial that concluded ineffectiveness is likely to discourage further research. This problem was identified over 20 years ago3 (‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’), and subsequent studies have documented its persistence.4 5

The motivation for this study was our observation that, despite these warnings, poor interpretations of non-conclusive trial results remain common, even in the most prestigious journals. Many trials where the main results are not statistically significant conclude that there is no difference between the treatments, the intervention did not improve outcomes, or that it was not effective, none of which is a justified interpretation.

We examined how results were described in the Abstracts of recent reports of RCTs where the primary outcome did not show a statistically significant difference between the treatment arms, published in four leading general medical journals.

Methods

We hand searched issues of four journals (New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), The Lancet and British Medical Journal (BMJ)) published between June 2016 and June 2017. Papers were included if they were primary reports of RCTs that had results for their primary outcome that were not statistically significant’ that is, did not reach a pre-specified threshold p value that was regarded as indicating a true effect. We excluded non-inferiority, equivalence, single armed, dose-finding and pharmacokinetic trials, as they have different reporting issues, and those that used Bayesian statistical methods. We included trials with more than two arms, and trials with multiple primary comparisons, if no treatment differences were claimed.

We extracted information from the abstract of each report on the description (from Results or Findings section) and interpretation (from Conclusions or Interpretation section) of the trial's results for the primary outcome or outcomes. We concentrated on the abstracts because these are the most frequently viewed parts of papers, so conclusions expressed here will have the most impact. We classified the descriptions into ten categories (table 1). The classification was developed at the start of the project, by reviewing trial reports from the same journals that were published in January to May 2016, the period immediately before our study’s eligibility window. The classification made a distinction between reporting that claimed a lack of directional effect (eg, ‘no improvement’) and reporting that did not include any directional information (eg, ‘no difference’), as well as whether the claim was qualified by reference to statistical significance (eg, ‘no significant difference’) or something else (eg, ‘no substantial difference’). We created additional categories during the study for reports that used methods that did not fit into any of the predetermined categories; for example, statements such as ‘there was a lack of evidence for a difference,’ or ‘treatments were similar’. We also recorded whether confidence intervals (CIs) and p values were presented, and whether the CI, or uncertainty more generally, was referred to in the conclusions.

Table 1.

Categories of reporting of randomised controlled trial results in Results and Conclusion sections of Abstracts. For trials with multiple results, all were reported in the same way in all trials except one; for this trial, we have included the results for the survival co-primary outcome rather than the ordinal composite outcome.

| Category | Description | Examples | Number of comparisons, n (%) (n=120) |

Number of papers (%) (n=94) | ||

| Results | Conclusions | Results | Conclusions | |||

| 1 | Statement of no difference between treatments. | “did not differ,” “no difference,” “no effect,” “no change.” | 9 (7.5) | 5 (4.2) | 7 (7.4) | 1 (1.1) |

| 2 | Statement that there was no difference between treatment, qualified by reference to statistical significance. | “no significant difference,” “not statistically different,” “not statistically significant,” “no significant effect.” | 38 (31.7) | 16 (13.3) | 29 (30.9) | 15 (16.0) |

| 3 | Statement that there was no difference between treatments, qualified by something other than statistical significance. | “no substantial difference,” “no clinically relevant difference.” | 3 (2.5) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| 4 | Statement that the intervention was not beneficial. | “did not result in increase (or decrease or improve),” “was not superior,” “did not increase (or decrease or improve),” “did not prevent.” | 7 (5.8) | 65 (54.2) | 3 (3.2) | 50 (53.2) |

| 5 | Statement that the intervention was not beneficial, qualified by reference to statistical significance. | “not significantly better (or worse),” “did not significantly increase (or decrease),” “not statistically increased (or decreased).” | 2 (1.7) | 14 (11.7) | 2 (2.1) | 12 (12.8) |

| 6 | Statement that the intervention was not beneficial, qualified by reference to something other than statistical significance. | “not substantially increased (or decreased).” | 0 (0) | 3 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.1) |

| 7 | Statement that there was a lack of evidence for a difference. | “no evidence that (intervention) reduced the risk of (outcome).” | 0 (0) | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.1) |

| 8 | Statement that the treatments compared were similar. | “yield similar outcomes” “similar risk of [outcome]” “rate of [outcome] was similar.” |

3 (2.5) | 7 (5.8) | 3 (3.2) | 4 (4.3) |

| 9 | Quotation of the results, without any claim about the size or direction of effect. | Estimate and 95% CI. | 58 (48.3) | 4 (3.3) | 48 (51.1) | 4 (4.3) |

| 10 | Clinical recommendation, without interpretation of results. | “There is no harm in (using intervention)” “The choice between (interventions) should be made based on clinical knowledge.” |

0 (0) | 3 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.2) |

Data were extracted by both authors independently and discrepancies resolved by discussion, leading to consensus in all cases. The authors were not blinded to the journals and authorship of individual articles.

Results

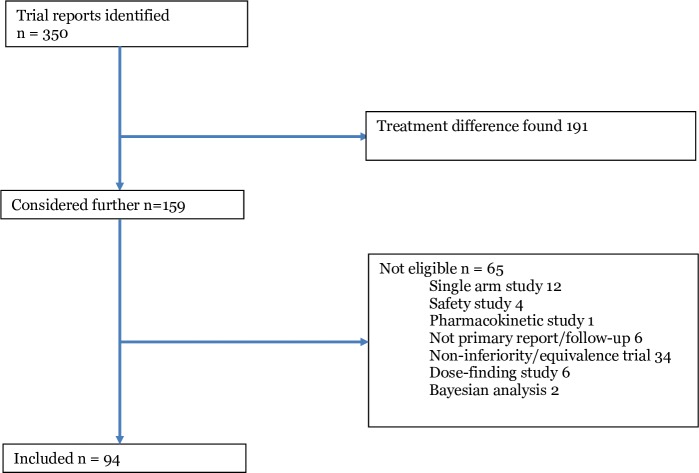

We identified 351 trial reports, of which 257 were not eligible, leaving 94 eligible papers, which reported 120 treatment comparisons (figure 1). Three journals published the majority of studies (JAMA 28, Lancet 26, NEJM 32 and BMJ 8). Significance tests were presented for 94/120 (78.3%) comparisons (79/94 papers (84%)), and CIs for 96/120 (80%) comparisons (79/94 papers (84%)).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of studies.

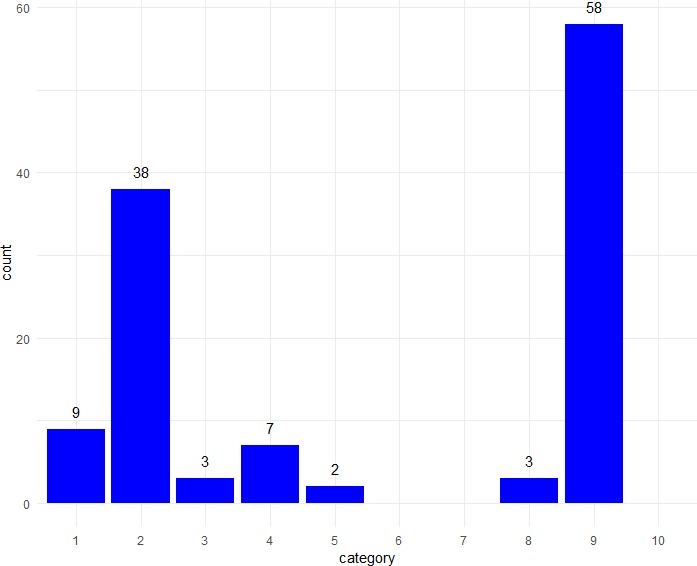

In Results section (figure 2), the most common reporting style was to present the point estimate and CI, without any interpretation (58/120; 48.3%). A substantial number also referred to lack of statistical significance (38/120; 31.7%) or stated that there was no difference (9/120; 7.5%) or no improvement (7/120; 5.8%).

Figure 2.

Frequencies of different types of description of results in Results section of Abstracts (n=120 treatment comparisons). Categories (described fully in table 1): 1. no difference; 2. no statistically significant difference; 3. no substantial or clinically important difference; 4. no improvement or no treatment benefit; 5. no significant improvement; 6. no substantial improvement; 7. lack of evidence for a difference; 8. treatments were similar; 9. statement of results; 10. clinical recommendation.

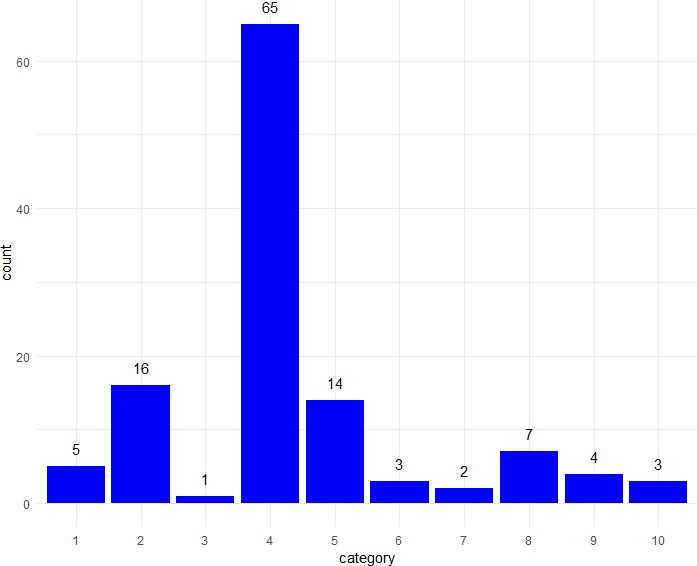

In Conclusions (figure 3), a substantial majority of comparisons were classified as stating that there was no treatment benefit (65/120; 54.2%). The main alternative approach was to re-state the lack of a statistically significant difference (16/120; 13.3%) or lack of statistically significant benefit (14/120; 11.7%).

Figure 3.

Frequencies of different types of description of results in Conclusions section of Abstracts (n=120 treatment comparisons). Categories (described fully in table 1): 1. no difference; 2. no statistically significant difference; 3. no substantial or clinically important difference; 4. no improvement or no treatment benefit; 5. no significant improvement; 6. no substantial improvement; 7. lack of evidence for a difference; 8. treatments were similar; 9. statement of results; 10. clinical recommendation.

Results for papers rather than comparisons were similar (table 1).

A threshold of p<0.05 for statistical significance was used in all but two studies, which used lower values (0.04 and 0.01), as part of a correction for multiple comparisons. Similarly, all except these two studies used 95% CIs. CIs for the main treatment comparison were presented by 79/94 studies (84.0%). This was surprisingly low, given that they have been a required part of trial reporting in the CONSORT guidelines for many years. Those that did not present CIs for the main comparison either presented CIs for the difference of each randomised group from baseline, or used only p values. Both of these are poor reporting practices. The proportion of trials presenting p values was the same (79/94; 84%). Sixty-four studies presented both CIs and p values, 15 CIs without p values, and 15 only p values. Very few trials (3/94; 3.2%) explicitly referred to the CI or uncertainty around the treatment effect estimate when drawing conclusions.

Discussion

Main results

Over 50% of the studies interpreted a non-significant result inappropriately, as indicating that there was ‘no difference’ or ‘no benefit’ to the intervention. Lack of statistical significance does not mean that no difference exists; this is one of the most basic misinterpretations of significance testing.1

Many of the studies that concluded a lack of benefit had substantial uncertainty about the direction and size of the treatment effect. For example, one trial concluded that the incidence of the outcome was ‘not reduced’ by the intervention, based on a risk ratio of 1.13 (95% CI 0.63, 2.00).6 The CI indicates that both substantial reduction or substantial increase (risk ratios as low as 0.63 or as high as 2.00) are compatible with the data, so the conclusion of no reduction does not seem justified. Conversely, some trials concluded ‘no benefit’ when the results were actually strongly in one direction. One trial that concluded that the intervention was ‘not found to be superior,’ with an HR of 0.89 and a 95% CI of 0.78 to 1.01.7 The conclusion seems inadequate; the study did suggest benefit, but not strongly enough to meet the arbitrary criterion for statistical significance. It does not seem reasonable for the conclusions from these two examples to be so similar, when the results are substantially different.

A further 24.3% of comparisons qualified their conclusion of lack of treatment benefit by referring to statistical significance (categories 2 and 5). This description is uninformative, because simply knowing that an arbitrary threshold was not achieved does not give much useful information, and relies on the reader being able to decode correctly what ‘significant’ means in this context. It invites confusion between the technical meaning of ‘statistical significance’ and the common English meaning of the word (important, substantial, worthy of attention), especially as results are often reported using phrases such as ‘not significantly different’ or ‘no significant benefit’ which can be read (and make sense) either as a statement about a formal statistical significance test, or as a regular English sentence. There is substantial empirical evidence that statistical significance is often misinterpreted by the public,8 academic researchers9 and statisticians.10

Statements that the interventions were ‘similar’ (category 8), there was no ‘substantial’ difference (category 3) or no ‘clinically important’ difference (category 6), which were used by smaller numbers of studies, are also difficult to interpret. None of them can be generally recommended as a way to describe non-significant results, but all might be appropriate in different circumstances.

The most reasonable way to describe non-significant results is probably that the study did not find convincing evidence against the hypothesis that that the treatment effect was zero. Only one study contained a statement that referred to lack of evidence for a difference: ‘We found no evidence that an intervention comprising cleaner burning biomass-fuelled cookstoves reduced the risk of pneumonia in young children in rural Malawi,’11 describing an estimated incidence rate ratio of 1.01, with 95% CI 0.91 to 1.13. Hence the data were compatible with either a small increase, or a small decrease, in the risk of pneumonia.

Statistical methods

All of the trials in our sample used traditional frequentist statistical methods. Although this is the dominant statistical methodology in clinical trials, there are many problems in the understanding and interpretation of p values, significance tests,1 12 13 and CIs,14 15 which have recently received substantial publicity, in the wake of publication of the American Statistical Association’s guidance on p values and significance testing2 and more recent publications.16–19

One important issue is the use of a threshold for ‘significance’, creating a binary classification of results, which is usually interpreted as indicating treatments that ‘work’ and ‘don’t work’ (or ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ trials, or ‘effective’ and ‘ineffective’ treatments).19–21 In reality, there is no such sharp dividing line between treatments that work and do not work, and significance tests simply impose an arbitrary criterion. The persistence of dichotomisation of results may be largely due to an unrealistic expectation that trials will provide certainty in their conclusions and treatment recommendations. Sometimes trials will reduce our uncertainty sufficiently that the best clinical course of action is clear, but often they will not. An argument that is often advanced in favour of dichotomisation of results is that because many trials seek to inform clinical practice, a decision needs to be made about whether the intervention should be used in patient care. The counter-argument to this is that decisions about use of healthcare interventions should be based not on whether a single primary outcome reaches an arbitrary significance threshold, but on consideration of the overall benefits, harms and costs of the intervention, using appropriate decision modelling methodology.

Improving the language for describing results

One straightforward way to improve reporting of results is to be more careful about the language that is used to describe them and draw conclusions, and ensure that written descriptions match the numerical results. We should avoid language that is ambiguous or open to misinterpretation, for example, only describing treatments as ineffective if we have a high degree of confidence that the treatment does not have clinically important effects. We should also pay more attention to uncertainty, and consider what possible values of the unknown underlying treatment effect could have given rise to the data that were observed. Often, this range will be wide. We should not expect every trial to lead to a clear treatment recommendation, but be honest about the degree to which a study is able to reduce our uncertainty. CIs were originally promoted for trial reporting to encourage this sort of interpretation, and to avoid the false certainty provided by significance tests.22 23 But even though most trials now present them, they are rarely considered in the conclusions,24 25 and are often used simply as an alternative way to perform significance tests, concentrating only on whether the CI excludes the null value.

A recent online discussion26 about language for describing frequentist trial results gave some examples of accurate statements that could be used. Three examples of statements for trials that did not find a treatment difference, from this discussion, are given in table 2. These statements are very different from those used by most of the papers in our sample, and make much more limited claims than many real papers. However, these claims accurately reflect the conclusions that can be drawn from frequentist statistical analyses. More accurate language would help to prevent common over-interpretations, such as the belief that non-significance means that a treatment difference of zero has been established.

Table 2.

Examples of accurate statements for describing non-significant frequentist results, from https://discourse.datamethods.org/t/language-for-communicating-frequentist-results-about-treatment-effects/934,23 concerning a hypothetical trial that evaluating differences in systolic blood pressure (SBP)

| Example 1 | We were unable to find evidence against the hypothesis that A=B (p=0.4) with the current sample size. More data will be needed. As the statistical analysis plan specified a frequentist approach, the study did not provide evidence of similarity of A and B. |

| Example 2 | Assuming the study’s experimental design and sampling scheme, the probability is 0.4 that another study would yield a test statistic for comparing two means that is more impressive that what we observed in our study, if treatment B had exactly the same true mean SBP as treatment A. |

| Example 3 | Treatment B was observed in our sample of n subjects to have a 4 mm Hg lower mean SBP than treatment A with a 0.95 two-sided compatibility interval of (−13, 5), indicating a wide range of plausible true treatment effects. The degree of evidence against the null hypothesis that the treatments are interchangeable is p=0.11. |

Improving the statistical methods

A more radical solution is to change the statistical approach that we use. One fundamental problem with traditional frequentist statistical methods is that they do not provide the results that clinicians, policy makers and patients actually want to know: what are the most plausible values of the treatment effect, given the observed data? Significance tests actually do the reverse; they calculate probabilities of the data (or more extreme data), assuming a specific null value of the treatment effect. This is a major reason why reporting frequentist results accurately is so convoluted, and why they are so difficult to understand. However, easily-interpretable probabilities of clinically relevant results can be readily obtained using Bayesian methods. The output from a Bayesian analysis is a probability distribution giving the probability of all possible values of the treatment effect, taking into account the trial’s data, and usually (via the prior), external information as well. We can use this distribution (the posterior probability distribution) to calculate relevant and informative results, such as the probability of a benefit exceeding a threshold for clinical importance, the probability of the treatment effect being within a range of clinical equivalence, or the range of treatment effects with 95% probability (or 50%, or any other value). Some examples of the sorts of informative statements that can be made from Bayesian results are given in a blog post by Frank Harrell.27 A particular advantage is that, with Bayesian methods, there is no need to reduce results to a dichotomy, but instead we can refer directly to probabilities of events of interest.

Limitations of this study

This study looked only at reporting of results in abstracts of published RCTs. We concentrated on abstracts because they are the most frequently read parts of papers, and always report the main results. They are therefore likely to be particularly important in determining readers’ interpretation of the trial’s results. It is possible that in other parts of the papers, reporting may have been different, and potentially more accurate. However, this is much harder to assess because results are typically reported in several different places, and often inconsistently.

We concentrated on four of the highest profile general medical journals. Obviously, RCTs are also published in a large number of other, more specialised, journals, but we cannot say whether they have the same issues of reporting as we found. Our expectation would be that, as the journals we selected are seen as some of the most prestigious publications, reporting problems would be at least as common elsewhere.

Our classification of reporting types was invented by the authors, and is not intended as a general tool for conducting this type of study. However, we feel that it is a reasonable classification that makes distinctions between the different types of reporting that we wished to identify.

Conclusions

Despite many years of warnings, inappropriate interpretations of RCT results are widespread in the most prestigious medical journals. We speculatively suggest several possible factors that may be responsible. First, authors and editors may want to present a clear message, and there is a widespread expectation that RCTs should result in clear recommendations for clinical practice. It is easier to understand a conclusion that ‘X did not work’ than a complicated statement that more accurately reflects what a non-significant result means. Second, use of significance testing as the main analytical method provides a ready means of dichotomisation of results, encouraging an over-simplified binary interpretation of interventions. Third, the general difficulty of understanding frequentist results means that correct interpretation is convoluted and difficult to relate to real life.

We suggest that interpretation of results should pay more attention to uncertainty and the range of treatment effects that could plausibly have given rise to the observed data. Use of Bayesian statistical methods would facilitate this by addressing the clinical questions of interest directly.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SG designed the study, assisted with data extraction, performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. EE collected the data, assisted with analysis and revised the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. SG is a National Institute of Health Research Senior Investigator.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository (https://osf.io/chsva/files/).

References

- 1. Greenland S, Senn SJ, Rothman KJ, et al. Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:337–50. 10.1007/s10654-016-0149-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA statement on p -values: context, process, and purpose. Am Stat 2016;70:129–33. 10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics notes: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ 1995;311:485 10.1136/bmj.311.7003.485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alderson P, Chalmers I. Research pointers: survey of claims of no effect in Abstracts of Cochrane reviews. BMJ 2003;326:475 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greenland S. Null misinterpretation in statistical testing and its impact on health risk assessment. Prev Med 2011;53:225–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomusch O, Wiesener M, Opgenoorth M, et al. Rabbit-ATG or basiliximab induction for rapid steroid withdrawal after renal transplantation (harmony): an open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2016;388:3006–16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32187-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Albers GW, et al. Ticagrelor versus aspirin in acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2016;375:35–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1603060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tromovitch P. The lay public’s misinterpretation of the meaning of ’significant’: A call for simple yet significant changes in scientific reporting. Journal of Research Practice 2015;11. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haller H, Krauss S. Misinterpretations of significance: a problem students share with their teachers. Methods of Psychological Research 2002;7:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10. McShane BB, Gal D. Blinding us to the obvious? the effect of statistical training on the evaluation of evidence. Manage Sci 2016;62:1707–18. 10.1287/mnsc.2015.2212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mortimer K, Ndamala CB, Naunje AW, et al. A cleaner burning biomass-fuelled cookstove intervention to prevent pneumonia in children under 5 years old in rural Malawi (the cooking and pneumonia study): a cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2017;389:167–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32507-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goodman S. A dirty dozen: twelve p-value misconceptions : Seminars in hematology. 45 Elsevier, 2008: 135–40. 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goodman SN. Toward evidence-based medical statistics. 1: the P value fallacy. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:995–1004. 10.7326/0003-4819-130-12-199906150-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoekstra R, Morey RD, Rouder JN, et al. Robust misinterpretation of confidence intervals. Psychon Bull Rev 2014;21:1157–64. 10.3758/s13423-013-0572-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morey RD, Hoekstra R, Rouder JN, et al. The fallacy of placing confidence in confidence intervals. Psychon Bull Rev 2016;23:103–23. 10.3758/s13423-015-0947-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amrhein V, Greenland S, McShane B. Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature 2019;567:305–7. 10.1038/d41586-019-00857-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Benjamin DJ, Berger JO, Johannesson M, et al. Redefine statistical significance. Nat Hum Behav 2018;2:6–10. 10.1038/s41562-017-0189-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lakens D, Adolfi FG, Albers CJ, et al. Justify your alpha. Nat Hum Behav 2018;2:168–71. 10.1038/s41562-018-0311-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McShane BB, Gal D. Statistical significance and the Dichotomization of evidence. J Am Stat Assoc 2017;112:885–95. 10.1080/01621459.2017.1289846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Senn S. Dichotomania: an obsessive compulsive disorder that is badly affecting the quality of analysis of pharmaceutical trials. Proceedings of the International Statistical Institute, 55th Session, Sydney, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gelman A, Stern H. The Difference Between “Significant” and “Not Significant” is not Itself Statistically Significant. Am Stat 2006;60:328–31. 10.1198/000313006X152649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. Consort 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gardner MJ, Altman DG. Confidence intervals rather than P values: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. BMJ 1986;292:746–50. 10.1136/bmj.292.6522.746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fidler F, Thomason N, Cumming G, et al. Editors can lead researchers to confidence intervals, but can’t make them think: Statistical reform lessons from medicine. Psychological Science 2004;15:119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gewandter JS, McDermott MP, Kitt RA, et al. Interpretation of cis in clinical trials with non-significant results: systematic review and recommendations. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017288 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Datamethods Language for communicating frequentist results about treatment effects, 2018. Available: https://discourse.datamethods.org/t/language-for-communicating-frequentist-results-about-treatment-effects/934

- 27. Statistical Thinking Bayesian vs. Frequentist statements about treatment efficacy, 2018. Available: https://www.fharrell.com/post/bayes-freq-stmts/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.