Abstract

Objectives

To assess the association between hand grip strength (HGS) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among Korean cancer survivors.

Design

Population-based cross-sectional study.

Setting

A nationally representative population survey data (face-to-face interviews and health examinations were performed in mobile examination centres).

Participants

A total of 1037 cancer survivors (person with cancer of any type who is still living) with available data on HGS and HRQoL in the sixth and seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (2014–2017).

Primary outcome measures

Prevalence of impaired HRQoL by HGS.

Results

Among 1037 cancer survivors (60.7% women, mean age=62.2 years), 19.2% of them had weak HGS according to gender-specific cut-off values (lowest quintile<29.7 kg in men and <19.7 kg in women). In the study population, the most common cancer site was the stomach, followed by the thyroid, breast, colorectal and cervix. Individuals with weak HGS showed statistically significantly increased impairment in all five dimensions of the EuroQoL-5 dimension (EQ-5D) compared with those in patients with normal HGS. In a multinomial logistic regression analysis, impaired HRQoL (some or extreme problem in EQ-5D) was significantly reduced in each dimension of the EQ-5D, except for anxiety/depression, when HGS was increased. The OR for impaired HRQoL ranged from 0.86 to 0.97 per 1 kg increase in HGS in four dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activity and pain/discomfort).

Conclusions

Weak HGS was associated with impaired HRQoL in cancer survivors. Future longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the causality between HGS and HRQoL in cancer survivors.

Keywords: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, neoplasms, cancer survivors, hand strength, quality of life

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study identified that weak hand grip strength (HGS) is associated with impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in cancer survivors.

The data used in this study were derived from nationally representative and well-designed systematic surveys.

The cross-sectional design of this study limits the ability to establish causal-interference relationships between HGS and HRQoL.

Because our data were confined to the Korean population, the results cannot be generalised to other ethnic populations.

Introduction

Cancer is a fatal and serious disease. However, with improving diagnostic and therapeutic techniques, the survival rate of cancer patients is increasing worldwide.1 According to the Korea National Cancer Incidence Database, overall cancer mortality has decreased 2.7% annually since 2002, although the all-cancer incidence rate increased by 3.6% annually from 1999 to 2011, resulting in a long-term survival probability of 70.5% in the 2010s compared with the that in 1990s.2

Cancer survivor is defined as a person who has been diagnosed with cancer of any type, including before, during and after treatment.3 Compared with individuals in the general population, cancer survivors have increased risks of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, second primary malignancy and osteoporosis.4–6 Furthermore, deterioration of physical function and psychosocial problems are common.7

As these survival issues and the life expectancy of cancer survivors have increased, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) has become an important outcome measure for survivors. HRQoL is a subjective, multidimensional concept that encompasses physical, social, functional and psychological/emotional health factors related to an individual’s health. Several studies have reported that the HRQoL of cancer survivors is significantly lower than that of the non-cancer population.8–10 The poor quality of life of cancer survivors is probably due to cancer itself and/or side effects of cancer treatments. Thus, there is a need to better monitor the quality of life in cancer survivors.

Hand grip strength (HGS) is a simple, fast and reliable method for evaluating maximum voluntary squeezing force.11 12 The measurement of HGS is useful not only to evaluate the qualitative and functional aspects of muscle strength in clinical practice but also to predict nutritional and general health statuses.13 14 Additionally, HGS is associated with multiple chronic diseases and multimorbidity after adjusting for confounding factors.15 Recent data showed that HGS could be an independent predictor of the quality of life in various disease settings ranging from arthritis to chronic liver disease and depression.16–18 In contrast, data on the impact of HGS on HRQoL in cancer survivors are lacking.

Given the above, we evaluated the cross-sectional associations of HGS with HRQoL among cancer survivors, using nationally representative data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES).

Materials and methods

Study population

The KNHANES is a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey that has been conducted to assess the health and nutritional statuses of the general population of Korea since 1998. The KNHANES uses a stratified multistage probability sampling to accurately represent the general population of South Korea. The present study analysed data from the KNHANES VI-2,3 (2014–2015) and VII-1,2 (2016–2017). Adults who have been diagnosed with any type of cancer by a physician were included in this study as cancer survivors. As shown in figure 1, a total of 1037 participants who met the eligibility criteria were enrolled in this study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant selection (KNHANES VI–VII, Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey VI–VII). EQ-5D, EuroQoL-5 dimension.

Personal characteristics and clinical data

The demographic characteristics included age, sex, height, weight, body mass index, education (<10 years or ≥10 years), household income (low or high), residence (rural or urban) and marital status (living with someone or alone). Health behaviours, including smoking status (never, former or current), high-risk drinking and physical activity, were also assessed. High-risk drinking was defined as the consumption of more than seven (men) or five (women) drinks on a single occasion at least two times a week. Adequate physical activity was defined as at least 30 min of moderate-intensity activity 5 days a week or at least 20 min of vigorous physical activity 3 days per week. The comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease, stroke and depression. We collected data on cancer sites without data on current treatment and cancer-related symptoms.

Measurement of HGS

HGS was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital hand dynamometer (Digital Grip Strength Dynamometer, T.K.K.5401, Takei Scientific Instruments Co., Tokyo, Japan). During the assessment, the participants were required to stand upright with their feet hip-width apart and to stretch their elbows completely. The participants were asked to apply the maximum grip strength three times for their left and right hands individually. The participants were instructed to hold the grip continuously with full force for more than 3 s. At least 30 s of rest was allowed between each measurement. Grip strength was defined as the maximally measured value among the six measurements in both hands. Weak HGS was defined as the lowest quintile in both men and women.

Assessment of HRQoL

We assessed HRQoL using the EuroQoL-5 dimension (EQ-5D), which is a standardised instrument used to measure generic health status. It has been applied to a wide range of health conditions and treatments. The EQ-5D descriptive system comprises five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The participants had three possible responses depending on the severity for each dimension: ‘no problems’, ‘moderate problems’ and ‘severe problems’. The EQ-5D instrument has been translated into Korean.

Statistical analyses

We divided the participants into two groups based on HGS (normal or weak).

The baseline characteristics are reported as means and SD for all continuous variables and as frequencies and percentage for categorical variables. The differences in several covariates between the normal and weak HGS groups were assessed using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to examine the associations between HGS and impaired HRQoL. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.21.0. A two-tailed p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

We used publicly available and de-identified KNHANES data collected by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) for this study. No patients were involved in the design of this study.

Results

Among 1037 cancer survivors (60.7% women, mean age=62.2 years), the prevalent cancer site was the stomach, followed by the thyroid, breast, colorectum and cervix. Overall, cancer survivors most commonly reported problems in pain/discomfort domain, followed by mobility and anxiety/depression. The sex-specific HGS cut-off values (lowest quintile) were 29.7 kg in men and 19.7 kg in women. The weak HGS group comprised 199 participants (19.2%) (18.6% of men and 19.6% of women). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the normal and weak HGS groups. There were significant differences in several anthropometric measurements (height and weight), sociodemographic characteristics (education, household income, residential area, marital status and physical activity) and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes and stroke). Participants with weak HGS showed significantly more impaired status for all dimensions of the EQ-5D compared with those in participants with normal HGS.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1037 cancer survivors according to hand grip strength (HGS)

| Total (n=1037) |

Normal HGS (n=822) |

Weak HGS* (n=199) |

P value | |

| Age (years) | 62.2±12.4 | 60.3±12.1 | 70.1±10.3 | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.711 | |||

| Men | 408 (39.3) | 332 (39.6) | 76 (38.2) | |

| Women | 629 (60.7) | 506 (60.4) | 123 (61.8) | |

| Height (cm) | 160.4±8.2 | 161.3±7.8 | 156.3±8.6 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.7±10.1 | 61.6±10.0 | 56.7±9.3 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.6±3.2 | 23.6±3.3 | 23.2±3.2 | 0.071 |

| HGS (kg) | ||||

| Men | 36.3±7.7 | 38.7±6.2 | 25.9±3.7 | <0.001 |

| Women | 23.7±4.8 | 25.3±3.6 | 16.8±2.6 | <0.001 |

| Education, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| <10 years | 498 (48.0) | 365 (43.8) | 133 (66.8) | |

| ≥10 years | 535 (51.6) | 469 (56.2) | 66 (33.2) | |

| Income, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| First and second quartile (low) | 565 (54.5) | 419 (50.0) | 146 (73.4) | |

| Third and fourth quartile (high) | 471 (45.4) | 419 (50.0) | 52 (26.1) | |

| Residence, n (%) | 0.005 | |||

| Urban | 722 (69.6) | 600 (71.6) | 122 (61.3) | |

| Rural | 315 (30.4) | 238 (28.4) | 77 (38.7) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Live alone | 148 (14.3) | 98 (11.7) | 50 (25.1) | |

| Live with someone | 889 (85.7) | 740 (88.3) | 149 (74.9) | |

| Former/current smoking, n (%) | 374 (36.1) | 308 (37.2) | 66 (33.5) | 0.339 |

| Problem drinking†, n (%) | 371 (35.8) | 309 (42.1) | 62 (35.8) | 0.132 |

| Inadequate physical activity‡, n (%) | 610 (58.8) | 464 (55.6) | 146 (74.1) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 383 (36.9) | 289 (34.5) | 94 (47.2) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 161 (15.5) | 118 (14.1) | 43 (21.6) | 0.008 |

| Ischaemic heart diseases | 51 (4.9) | 42 (5.0) | 9 (4.5) | 0.774 |

| Stroke | 32 (3.1) | 17 (2.0) | 15 (7.5) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 58 (5.6) | 45 (5.4) | 13 (6.5) | 0.521 |

| Cancer site§, n (%) | 0.052 | |||

| Stomach | 194 (18.7) | 149 (17.8) | 45 (22.6) | |

| Colorectum | 134 (12.9) | 103 (12.3) | 31 (15.6) | |

| Liver | 31 (3.0) | 24 (2.9) | 7 (3.5) | |

| Breast¶ | 134 (21.3) | 111 (22.9) | 23 (18.7) | |

| Cervix¶ | 117 (18.6) | 95 (18.8) | 22 (17.9) | |

| Lung | 37 (3.6) | 31 (3.7) | 6 (3.0) | |

| Thyroid | 217 (20.9) | 195 (23.3) | 22 (11.1) | |

| Prostate¶ | 42 (10.3) | 32 (9.6) | 10 (13.2) | |

| Other | 184 (17.7) | 145 (17.3) | 39 (19.6) | |

| EQ-5D (moderate/severe problem), n (%) | ||||

| Mobility | 230 (22.2) | 142 (16.9) | 88 (44.2) | <0.001 |

| Self-care | 42 (4.1) | 20 (2.4) | 22 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| Usual activities | 135 (13.0) | 78 (9.3) | 57 (28.6) | <0.001 |

| Pain/discomfort | 291 (28.1) | 205 (24.5) | 86 (43.2) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety/depression | 127 (12.2) | 91 (10.9) | 36 (18.1) | 0.005 |

Data are given as mean±SD or number (%). P values were analysed by t-test or χ2 test.

*Defined as less than 29.7/19.7 kg (for men/women).

†Defined as consuming more than seven/five (for men/women) drinks on a single occasion at least two times a week.

‡Defined as less than 150 min per week.

§Allows for patient to have more than one type of cancer.

¶Percentage is limited to women for breast/cervical cancer and to men for prostate cancer.

BMI, body mass index; EQ-5D, EuroQoL-5 dimension.

The patterns of impairment of EQ-5D differed depending on age group, as shown in figure 2. In the 61–70 years age group, the prevalence of pain/discomfort was very high, and there was a significant difference in the percentage of those having problems between the normal and weak HGS groups in terms of self-care, usual activity and pain/discomfort. Overall, participants aged 20–60 years were less likely to have any problems in the EQ-5D compared with those aged 61–70 years. However, the overall patterns of impairment in the EQ-5D (shown as a radar chart plot) showed similar shapes between 20–60 and 61–70 years age groups. The 71–80 years age group showed a unique pattern in the EQ-5D compared with those of the other age groups. Problems in the mobility domain were more frequent, and there were significant differences in the percentages of participants having problems in the anxiety/depression dimension as well as mobility, self-care and usual activity between the normal and weak HGS groups, while there was no difference in the pain/discomfort dimension. Compared with the general population who never had been diagnosed with cancer, the difference in the frequency of impaired HRQoL according to weak HGS was remarkable in cancer survivors.

Figure 2.

Radar chart plot of the percentages of participants with impaired health-related quality of life according to age group in cancer survivors (compared with general population). Asterisk indicates a significantly (p value<0.05) larger percentage of impairment in health-related quality of life (some or extreme problems in EQ-5D dimensions) in the weak hand strength group compared with that in the normal group. AD, anxiety/depression; EQ-5D, EuroQoL-5 dimension; HGS, hand grip strength; MO, mobility; PD, pain/discomfort; SC, self-care; UA, usual activity.

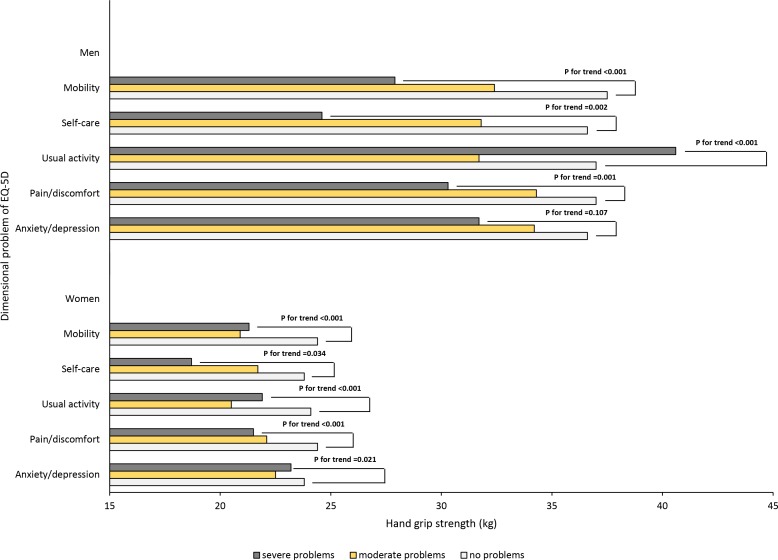

When the participants were divided into three groups according to the degree of problems as per the EQ-5D (no problem/moderate problem/severe problem), the mean HGS tended to decrease as the severity of the impairment increased in all the dimensions except for anxiety/depression for men and in all the dimensions for women (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparisons of hand grip strengths according to three levels of health-related quality of life for each dimension. The trend of hand grip strength according to the severity of dimension was assessed using Jonckheere-Terpstra tests. EQ-5D, EuroQoL-5 dimension.

Logistic regression analysis was performed to confirm the association between HGS and HRQoL represented by the five dimensions of the EQ-5D according to sex. All three models were used for logistic regression analysis. The first model was adjusted for just age, and the fully adjusted model included all covariables, showing a significant correlation in simple correlation. Finally, selective adjustment was performed by backward elimination with the significance set at p<0.05. The results of the logistic analysis are presented in table 2. In the selectively adjusted model, the OR for impairment of HRQoL decreased significantly (range 0.90–0.94) per 1 kg increase in HGS in terms of mobility, self-care, usual activity and pain/discomfort but not for anxiety/depression in men. In women, there was a similar association between HGS and HRQoL in each dimension except for anxiety/depression after selective adjustment.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis of the associations between hand grip strength (per 1 kg increase) and impaired status of health-related quality of life* (five dimensions of the EQ-5D)

| Adjusted for age | Fully adjusted† | Selectively adjusted‡ | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Men | ||||||

| Mobility | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.97) | 0.001 | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.98) | 0.003 | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.99) | 0.011 |

| Self-care | 0.89 (0.82 to 0.95) | 0.001 | 0.89 (0.80 to 0.97) | 0.009 | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.98) | 0.011 |

| Usual activity | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.97) | 0.001 | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | 0.015 | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.97) | 0.002 |

| Pain/discomfort | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.98) | 0.002 | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.99) | 0.017 | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.98) | 0.002 |

| Anxiety/depression | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) | 0.034 | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.04) | 0.429 | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.01) | 0.118 |

| Women | ||||||

| Mobility | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.98) | 0.009 | 0.94 (0.89 to 1.01) | 0.074 | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | 0.018 |

| Self-care | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.05) | 0.288 | 0.93 (0.82 to 1.06) | 0.257 | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.95) | 0.003 |

| Usual activity | 0.91 (0.86 to 0.97) | 0.003 | 0.93 (0.86 to 1.00) | 0.045 | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.97) | 0.006 |

| Pain/discomfort | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.98) | 0.003 | 0.94 (0.89 to 0.98) | 0.010 | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.97) | 0.002 |

| Anxiety/depression | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.01) | 0.077 | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.03) | 0.315 | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.02) | 0.234 |

*Impaired status of health-related quality of life: some or extreme problem in EQ-5D domains.

†Adjusted for age, height, weight, education, household income, residential area, marital status, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, stroke and depression).

‡Backward elimination method was used with significance set at p<0.05.

EQ-5D, EuroQoL-5 dimension.

Discussion

The major findings of this study are that weak HGS is significantly associated with having a poor HRQoL in cancer survivors among a representative population sample, according to the EQ-5D. Particularly, in multivariate analysis, the risk of impaired HRQoL was significantly reduced when HGS was increased in all dimensions of the EQ-5D except for anxiety/depression. The OR for impaired HRQoL ranged from 0.86 to 0.97 per 1 kg increase in HGS in four dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activity and pain/discomfort).

In the present study, the mean HGS value of cancer survivors by age was not different from that previously reported for the Korean general population.19 20 The reasons might be that patients with poor physical condition were excluded by chance due to the nature of the KNHANES or that most cancer survivors have well-managed physical function. However, these results were similar to those of a previous small-sized study. Morishita et al reported no difference in muscle strength between cancer survivors and healthy subjects. More importantly, they suggested that cancer survivors showed a meaningful correlation between muscle strength and HRQoL, whereas there was no association in healthy subjects.21 The results of the present study were also in good agreement with these results. These results that the weak HGS is more closely related to the impaired HRQoL in cancer survivors than the general population will be a basis for the need to monitor and rehabilitate muscle strength in cancer survivors.

The pain/discomfort dimension showed the highest proportion of participants with problem, accounting for 28.1% of the participating cancer survivors; this was followed by mobility (22.2%), usual activity (13.0%), anxiety/depression (12.2%) and self-care (4.1%) dimensions. These results were consistent with previous findings.10 22 Additionally, it was well-known that cancer survivors had a lower quality of life, which represented the impairment of not only physical function but also mental health, compared with those in non-cancer populations.10 23 24

Because HGS is a direct measure of muscle strength, it is an important predictor of muscle mass and overall muscle strength and also reflects part of the physical function.13 14 The HGS showed a strong correlation with the pain/discomfort dimension as well as the dimensions presumed to be directly related to physical function in cancer survivors, such as mobility, self-care and usual activity. There is evidence indicating that pain is related to muscle strength. Some studies showed that experimental pain reduced muscle strength directly25 and others suggested that variables, such as psychosocial factors, might affect both muscle strength and pain.26

The cancer survivors with weak HGS had significantly more anxiety/depression problems compared with those with normal HGS. However, after adjusting for covariates, the anxiety/depression dimension showed the weakest association with HGS in comparison with other dimensions. Other studies have shown similar results suggesting that HGS was positively correlated with global, physical and environmental domains but not with the psychological domain in quality of life.27 However, opposite results have also been reported. Jakobsen et al observed that HGS was correlated not only with mobility and physical function but also with the mental component of HRQoL.28 Recently, many studies have assessed the relationship between HGS and depression in the general population or elderly.18 29 Most have shown a positive correlation; in particular, a longitudinal study with a 6-year follow-up period reported that weak HGS increased the risk of depression.29 In recent years, cytokines, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and several interleukins (IL-6, IL-7 and IL-15) have been reported to be secreted by skeletal muscle and act on the brain, ultimately affecting cognitive function.30 31 One study suggested that low BDNF levels were associated with cognitive impairment and that high IL-6 levels were strongly associated with depression in cancer patients.32 HGS was also strongly correlated with the anxiety/depression domain only for elderly aged over 70 years in the age-based analysis of the present study. Taking the above into consideration, the time factor may need to be considered to confirm the association between HGS and anxiety/depression domain. Therefore, longitudinal studies are necessary.

This study has significant strength of using a nationally representative and well-designed systematic data. This study identified that weak HGS is associated with impaired HRQoL in cancer survivors. Previous studies have investigated the relationships in the general population or other disease settings,16 27 28 33 or have assessed other endpoints, such as cognitive dysfunction.34 As the number of cancer survivors has rapidly increased and monitoring and managing the quality of life of cancer survivors has become important, the results of this study are noteworthy. The results of this study suggest the possibility of weak HGS as a tool to predict poor HRQoL in cancer survivors. In addition, the measurement of HGS is easy, fast, inexpensive, reproducible and reliable enough to be used in clinical practice to monitor patient quality of life.

A major limitation of this study was its cross-sectional design, which makes it difficult to assess causality between HGS and quality of life. It is possible that poor physical function represented by weak HGS may have been the direct cause of poor quality of life. Conversely, cancer survivors with better HRQoL may be more independent, so that the physical function is well maintained. Of course, both may behave in a bidirectional way. Second, there may be a selection bias, even if this survey was well-designed to include a sample representing the Korean population. Subjects who died early or cancer survivors living in nursing homes or long-term care facilities may not have been included in this study. In addition, there was a possibility of under-reporting because it was a self-reporting system about the history of cancer. Third, we did not collect detailed medical information related to cancer, such as cancer stage, types of cancer treatments and family history of cancer. Fourth, since our data were confined to the Korean population, the results cannot be generalised to other ethnic populations. Finally, there was a disadvantage that the cut-off value of the HGS used in this study was arbitrarily determined. We classified the normal HGS group and the weak HGS group as the lowest quintiles (29.7 kg for men and 19.7 kg for women). These values were similar to the cut-off values for low muscle strength of 30 kg for men and 20 kg for women for diagnosing sarcopenia defined by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP).35 Although the recently updated guideline recommended the low cut-off value for low muscle strength of 27 kg for men and 16 kg for women by the EWGSOP2,36 we could not analyse data according to these values since the number of cases under 27 kg for men and 16 kg for women was extremely small.

Conclusion

Our results from a population-based sample show that weak HGS is significantly associated with impaired HRQoL in cancer survivors. HGS can be used as a predictor of quality of life in cancer survivors as it is easy, inexpensive and reliable. The anxiety/depression dimension had a relatively weak correlation with HGS compared with those of mobility, self-care, usual activity and pain/discomfort. Future prospective studies on the management of weak HGS in cancer survivors will increase understanding of the causal relationships and determine the clinical implications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the KCDC, who performed the KNHANES.

Footnotes

Contributors: YJC: conceived the study question and contributed to the study design, supervision of data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. JP: contributed to the study design and undertook data collection, analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study’s protocol for performing an analysis of the 2014–2017 KNHANES data was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. 10.3322/caac.21442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, et al. . Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2016. Cancer Res Treat 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mayer DK, Nasso SF, Earp JA, et al. . Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:e11–18. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30573-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivorship: the interface of aging, comorbidity, and quality care. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:504–5. 10.1093/jnci/djj154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lustberg MB, Reinbolt RE, Shapiro CL. Bone health in adult cancer survivorship. JCO 2012;30:3665–74. 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kenzik KM, Morey MC, Cohen HJ, et al. . Symptoms, weight loss, and physical function in a lifestyle intervention study of older cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol 2015;6:424–32. 10.1016/j.jgo.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer 2008;112:2577–92. 10.1002/cncr.23448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Annunziata MA, Muzzatti B, Flaiban C, et al. . Long-Term quality of life profile in oncology: a comparison between cancer survivors and the general population. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:651–6. 10.1007/s00520-017-3880-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Annunziata MA, Muzzatti B, Giovannini L, et al. . Is long-term cancer survivors' quality of life comparable to that of the general population? an Italian study. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:2663–8. 10.1007/s00520-015-2628-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oh MG, Han MA, Park C-Y, et al. . Health-Related quality of life among cancer survivors in Korea: the Korea National health and nutrition examination survey. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2014;44:153–8. 10.1093/jjco/hyt187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Günther CM, Bürger A, Rickert M, et al. . Grip strength in healthy Caucasian adults: reference values. J Hand Surg Am 2008;33:558–65. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bohannon RW. Test-Retest reliability of measurements of Hand-Grip strength obtained by dynamometry from older adults: a systematic review of research in the PubMed database. J Frailty Aging 2017;6:83–7. 10.14283/jfa.2017.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bohannon RW. Hand-grip dynamometry predicts future outcomes in aging adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2008;31:3–10. 10.1519/00139143-200831010-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bohannon RW. Muscle strength: clinical and prognostic value of hand-grip dynamometry. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2015;18:465–70. 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheung C-L, Nguyen U-SDT, Au E, et al. . Association of handgrip strength with chronic diseases and multimorbidity: a cross-sectional study. Age 2013;35:929–41. 10.1007/s11357-012-9385-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rashed AM, Abdel-Wahab N, Moussa EMM, et al. . Association of hand grip strength with disease activity, disability and quality of life in children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Adv Rheumatol 2018;58 10.1186/s42358-018-0012-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nishikawa H, Enomoto H, Yoh K, et al. . Health-Related quality of life in chronic liver diseases: a strong impact of hand grip strength. J Clin Med 2018;7 10.3390/jcm7120553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee M-R, Jung SM, Bang H, et al. . The association between muscular strength and depression in Korean adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the sixth Korea National health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES VI) 2014. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1123 10.1186/s12889-018-6030-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim CR, Jeon Y-J, Kim MC, et al. . Reference values for hand grip strength in the South Korean population. PLoS One 2018;13:e0195485 10.1371/journal.pone.0195485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoo JI, Choi H, Ha YC. Mean hand grip strength and cut-off value for sarcopenia in Korean adults using KNHANES VI. J Korean Med Sci 2017;32:868–72. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.5.868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morishita S, Tsubaki A, Fu JB, et al. . Cancer survivors exhibit a different relationship between muscle strength and health-related quality of life/fatigue compared to healthy subjects. Eur J Cancer Care 2018;27:e12856 10.1111/ecc.12856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Glaser AW, Fraser LK, Corner J, et al. . Patient-Reported outcomes of cancer survivors in England 1-5 years after diagnosis: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002317 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sánchez-Jiménez A, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Delgado-García G, et al. . Physical impairments and quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors: a case-control study. Eur J Cancer Care 2015;24:642–9. 10.1111/ecc.12218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Claridy MD, Ansa B, Damus F, et al. . Health-Related quality of life of African-American female breast cancer survivors, survivors of other cancers, and those without cancer. Qual Life Res 2018;27:2067–75. 10.1007/s11136-018-1862-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Henriksen M, Rosager S, Aaboe J, et al. . Experimental knee pain reduces muscle strength. J Pain 2011;12:460–7. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baert IAC, Meeus M, Mahmoudian A, et al. . Do psychosocial factors predict muscle strength, pain, or physical performance in patients with knee osteoarthritis? J Clin Rheumatol 2017;23:308–16. 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Musalek C, Kirchengast S. Grip strength as an indicator of health-related quality of life in old Age-A pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14 10.3390/ijerph14121447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jakobsen LH, Rask IK, Kondrup J. Validation of handgrip strength and endurance as a measure of physical function and quality of life in healthy subjects and patients. Nutrition 2010;26:542–50. 10.1016/j.nut.2009.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fukumori N, Yamamoto Y, Takegami M, et al. . Association between hand-grip strength and depressive symptoms: locomotive syndrome and health outcomes in Aizu cohort study (LOHAS). Age Ageing 2015;44:592–8. 10.1093/ageing/afv013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pedersen BK. Muscle as a secretory organ. Compr Physiol 2013;3:1337–62. 10.1002/cphy.c120033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ng T, Teo SM, Yeo HL, et al. . Brain-Derived neurotrophic factor genetic polymorphism (rs6265) is protective against chemotherapy-associated cognitive impairment in patients with early-stage breast cancer. Neuro Oncol 2016;18:244–51. 10.1093/neuonc/nov162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jehn CF, Becker B, Flath B, et al. . Neurocognitive function, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and IL-6 levels in cancer patients with depression. J Neuroimmunol 2015;287:88–92. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kilgour RD, Vigano A, Trutschnigg B, et al. . Handgrip strength predicts survival and is associated with markers of clinical and functional outcomes in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:3261–70. 10.1007/s00520-013-1894-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang L, Koyanagi A, Smith L, et al. . Hand grip strength and cognitive function among elderly cancer survivors. PLoS One 2018;13:e0197909 10.1371/journal.pone.0197909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. . Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working group on sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing 2010;39:412–23. 10.1093/ageing/afq034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. . Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019;48:16–31. 10.1093/ageing/afy169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.