Abstract

Objectives

In vivo lipopolysaccharide (LPS) tolerance on bacterial infection was investigated, focusing on liver macrophages.

Methods

LPS tolerance was induced by intraperitoneal injections with 5 μg/kg of LPS for 3 consecutive days, and then mice were intravenously infected with Escherichia coli.

Results

All LPS-primed mice survived lethal bacterial infection. Drastic enhancement of bactericidal activity of liver macrophages strongly contributed to bacterial clearance. Although LPS-primed mice produced substantial amounts of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inside the liver, TNF efflux into the systemic circulation was markedly suppressed. These mice showed a dramatic increase in CD11b+ monocyte- derived macrophages in the liver. The CD11b+ macrophages that increased in LPS-primed mice were those with strong phagocytic/bactericidal activity and an upregulated expression of Fcγ receptor I, but the subfraction with a potent TNF-producing capacity and poor phagocytic activity diminished. The adoptive transfer of CD11b+ macrophages from LPS-primed mice to control mice increased survival after bacterial infection and reduced the elevation of plasma TNF. LPS priming did not affect the CD68+ resident Kupffer cells, and CD68+ Kupffer cell-depleted mice still exhibited LPS tolerance with strong resistance to bacteremia.

Conclusions

LPS tolerance recruits CD11b+ macrophages to the liver with enhanced bactericidal activity, which plays a central role in resistance to lethal bacteremia.

Keywords: Lipopolysaccharide tolerance, Escherichia coli infection, Bacterial septicemia, Tumor necrosis factor, CD11b+, Monocyte-derived macrophages

Introduction

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) tolerance, also called endotoxin tolerance, is a transient unresponsive state of the host to LPS stimulation in which cells or organs do not respond to further challenges with a large dose of LPS after prior exposures to low concentrations of LPS [1]. Macrophages are the principal cells responsible for the induction of this LPS tolerance [1, 2]. They are the main producers of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), particularly in response to LPS stimulation, and this TNF production by macrophages is considered to play a crucial role in the regulation of inflammatory processes of the host as well as in the induction of LPS tolerance. TNF is a key cytokine that drives local inflammation by activating macrophages in the tissue, and it also induces deleterious systemic effects after LPS exposure [3, 4]. The status of LPS tolerance, characterized by diminished TNF production in the host macrophages after a challenge with a high dose of LPS following precedent exposures to a low dose of LPS, correlates well with the avoidance of LPS-induced lethality [1, 2, 5]. Therefore, the reduction in the plasma TNF levels after a high-dose LPS challenge is considered to be one of the best markers for LPS tolerance induced in animals [5].

When macrophages phagocytose bacteria, they become potently activated and produce certain amounts of TNF [6]. Despite its deleterious effect, TNF is indispensable for the elimination of infecting bacteria. Accordingly, the induction of LPS tolerance, i.e., a low TNF production status of tissue macrophages, might impair the host resistance to bacterial infections [5]. Consistent with this line of thinking, it has been reported that the neutralization of TNF by the administration of anti-TNF antibodies (Abs) did reduce its deleterious effects (e.g., shock and organ injury) after LPS challenge; however, improvement in the mortality of Escherichia coli-infected animals or patients with bacterial sepsis could not be achieved by simply neutralizing TNF [7].

LPS tolerance not only reduces TNF levels but also augments phagocytosis and other activities of macrophages [1, 8]. Phagocytosis of invading bacteria by Kupffer cells is essential for host defense, especially against systemic bacterial infection, because 80% of all macrophages reside in the liver as Kupffer cells and are responsible for the elimination of circulating bacteria from the blood stream. We recently demonstrated that 2 types of F4/80+ Kupffer cells/macrophages exist in the mouse liver [9, 10]: one is a CD68+ subset which is considered to be tissue-resident macrophages and demonstrates a potent phagocytic activity, while a CD11b+ subset is monocyte-derived recruited macrophages and has a potent TNF-producing capability. In the present study, using a LPS tolerance mouse model, characterization of those Kupffer cells/macrophages and their roles in systemic E. coli infection were investigated. No marked change in the number or functions of CD68+ resident Kupffer cells was observed, whereas a dramatic increase in the number of CD11b+ monocyte-derived macrophages was obvious, and upregulated phagocytic as well as bactericidal activities with reduced TNF production were remarkable in that population. We also show that LPS-tolerant mice acquired significant resistance to lethal septicemia.

Materials and Methods

The experimental protocol of the present study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Animal Care and Experimentation, National Defense Medical College Japan (permission No. 14055).

Animals and Reagents

Male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old, body weight 20 g) were purchased from Japan SLC (Hamamatsu, Japan) and used for this study. E. coli strain B (ATCC 11303) and LPS (E. coli 0111:B4) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and FITC-labeled E. coli as well as pHrodo-conjugated E. coli were purchased from BioParticles (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

In vivo LPS Priming and Lethal Challenge with LPS or E. coli

To induce LPS tolerance, mice were primed with an intraperitoneal injection of 5 μg/kg LPS (dissolved in 0.5 mL phosphate-buffered saline, PBS) once daily for 3 times. Control animals were injected with PBS (0.5 mL). To monitor survival after LPS or E. coli challenge, 24 h after the last priming injection, the mice were intravenously challenged with a lethal dose of LPS (15 mg/kg) or viable E. coli (1 × 109 colony forming units [CFU]/mouse).

Collection of Blood or Tissue Samples and Measurement of Cytokines, Alanine Aminotransferase, and C-Reactive Protein

To measure plasma cytokine (e.g., TNF, interferon [IFN]-γ, interleukin [IL]-1β, IL-6, and IL-10), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), C-reactive protein (CRP), and tissue TNF levels after E. coli challenge, blood or tissue samples were obtained from the mice to measure the levels of cytokines, ALT, or CRP. The precise procedures are described in the online supplement (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000475931).

Isolation of Mononuclear Cells of the Liver, Spleen, and Other Organs, and Isolation of Neutrophils

To examine the TNF production by organ mononuclear cells (MNC) in E. coli-challenged mice, MNC were isolated from the liver, spleen, lung, Peyer patches, peripheral blood, and peritoneal exudate, using a Percoll solution-collagenase treatment method as previously described [9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. Neutrophils were also isolated from the blood as previously described [14]. The precise procedures are described in the online supplement.

Determination of Intracellular ATP Levels of Adherent Liver MNC

We examined intracellular ATP levels of adherent liver MNC in mice after LPS priming (1×, 2×, and 3×). Plastic adherent liver MNC were obtained as described in the online supplement [15] and their intracellular ATP levels were determined using a commercially available intracellular ATP assay kit (TOYO B-Net Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Viable Bacterial Count in the Liver

To examine the bacterial propagation in the liver after E. coli challenge, the livers were removed from the mice 12 h after bacterial challenge, and bacterial numbers were counted. Detailed information is described in the online supplement.

In situ Hybridization of TNF mRNA in the Liver

We examined the localization of TNF-producing cells in the liver after E. coli challenge. The removed livers were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) for regular histological examination. Also, in situ hybridization of TNF mRNA was performed as described previously [16]. Detailed information is described in the online supplement.

In vitro Stimulation of MNC with LPS or Cocultivation with E. coli (Bacterial Killing Assay)

To examine the in vitro LPS-stimulated TNF production in the liver MNC, liver MNC (5 × 105 cells/200 μL) were obtained from LPS-primed/control mice 24 h after 3× LPS priming and then cultured with 10 μg/mL LPS for 3 h. To examine the E. coli-killing activity, liver MNCs were also cocultured with 1 × 105 CFU of E. coli in antibiotic-free medium for 6 h, and their bacterial killing activity was measured as previously described [14, 17]. TNF concentrations of the medium were measured 3 h after coculture initiation.

Flow-Cytometric Analysis

To examine the proportion of CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets in the liver F4/80+ cells and alteration of their surface markers (e.g., CD69, CCR2, FcγRI, and C-type lectin domain family 4 member F [CLEC4F]), liver MNC were stained with the indicated fluorescence-labeled Abs of surface markers and a 3-color flow-cytometric analysis was performed using a FC500 flow cytometer, as described in detail in the online supplementary material.

Simultaneous Analysis of TNF Production and E. coli Phagocytic Activity in Liver F4/80+ Cells

We examined TNF production and E. coli phagocytosis simultaneously in the CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets of liver F4/80+ cells. LPS-primed/control mice were intravenously challenged with a sublethal dose of E. coli (7.5 × 108 CFU) containing 1 × 107 CFU of FITC-labeled E. coli as a tracer. After 20 min, liver MNC were obtained from the mice to examine TNF production capacity and E. coli phagocytic activity by F4/80+ liver MNC, using a PerFix-nc kit (no centrifuge assay kit, Beckman Coulter) and subsequently a flow cytometer. The precise details are described in the online supplement.

Digestion of pHrodo-Conjugated E. coli by Liver F4/80+ Cells and Annexin V Staining

We examined the digestive activity of E. coli and apoptotic potential in the CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets of liver F4/80+ cells. Liver MNC were incubated with pHrodo (acidic pH-dependent fluorescence)-conjugated E. coli for 30 min to examine the acidification of phagolysosomes following the ingestion of E. coli. Additionally, to examine annexin V staining, the incubated cells were also stained with annexin V. Precise details are provided in the online supplement.

Depletion of CD68+ F4/80+ Cells by Clodronate Liposome Pretreatment

To examine the effect of CD68+ F4/80+ cell depletion on E. coli infection in LPS-primed mice, clodronate (LKT Laboratories, St. Paul, MN, USA) encapsulated into liposomes (100 μL of a 25 mg/mL suspension) was intravenously injected into LPS-primed mice 1 and 4 days before E. coli challenge [9].

Adoptive Transfer of CD11b+ Adherent Liver MNC from LPS-Primed Mice to Control Mice

To examine the effect of the transfer of CD11b+ liver macrophages on E. coli infection in LPS-primed mice, cells of the CD11b+ subset were magnetically sorted from the adherent liver MNC of the LPS-primed or control mice using a MACS system (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) and were transferred to the normal mice. An E. coli challenge was then performed. Precise details are provided in the online supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the StatView 4.02J software package (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA, USA). Data are expressed as means ± SE. Survival rates were compared using the Wilcoxon rank test, and other statistical evaluations were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test among multiple groups or unpaired Student t test between two groups. p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

Whole Experimental Study Design

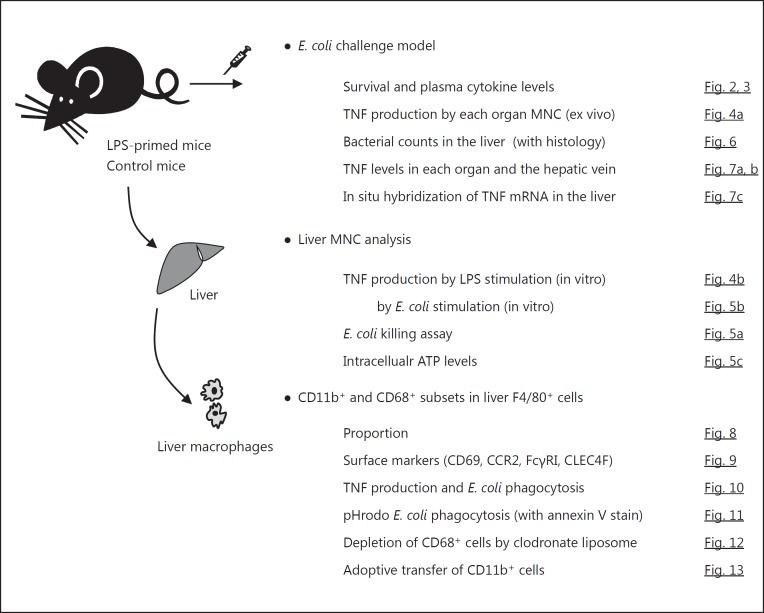

A schematic representation of the entire experimental study design is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the entire experimental study design.

LPS Priming Improves Mouse Survival after Lethal E. coli Challenge

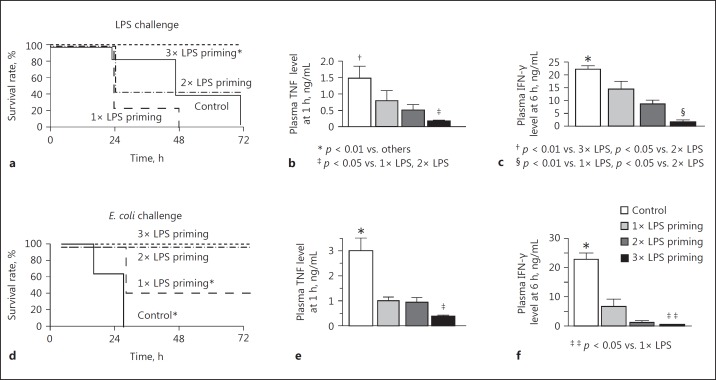

LPS priming with 3 daily intraperitoneal injections at a dose of 5 μg/kg successfully prevented all mice from lethal LPS challenge (15 mg/kg) although LPS priming with 1 or 2 injections of 5 μg/kg was not adequate to save the mice (Fig. 2a). These pretreatments with low-dose LPS (LPS priming) protected the mice from stress-induced elevation of plasma TNF levels at 1 h and IFN-γ levels at 6 h in response to lethal LPS challenge (Fig. 2b, c). This suggests that in vivo LPS tolerance was induced by LPS priming with 3 injections. Similarly, priming with 50 μg/kg LPS, but not 0.5 μg/kg, induced LPS tolerance in the mice (data not shown). LPS priming rescued mice from lethal E. coli challenge with a marked suppression of plasma TNF and IFN-γ (Fig. 2d, e, f, 3b, e). LPS priming also reduced the elevation of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 levels after bacterial challenge (Fig. 3a, c, d). These results indicate that LPS priming suppressed cytokine production and rendered the mice tolerant to lethal E. coli infection. However, LPS priming did not affect the neutrophil count after the bacterial challenge (Fig. 3f).

Fig. 2.

LPS or E. coli challenge in LPS-primed mice. LPS-primed (5 μg/kg, 1–3 times) mice and control mice were challenged with 15 mg/kg LPS i.v., then survival rates (a), plasma TNF levels at 1 h (b), and IFN-γ levels at 6 h (c) were observed. LPS-primed and control mice were also challenged with 1 × 109 CFU of E. coli to examine survival rates (d), plasma TNF levels at 1 h (e), and IFN-γ levels at 6 h (f). Data are means ± SE from 10 mice in each group.

Fig. 3.

Changes in the plasma cytokine levels and neutrophil counts after E. coli challenge in LPS-primed mice. LPS-primed/control mice were challenged with 1 × 109 CFU i.v. of E. coli to examine the plasma IL-1β (a), TNF (b), IL-6 (c), IL-10 (d), IFN-γ (e), and neutrophil count (f). Data are means ± SE from 10 mice in each group.

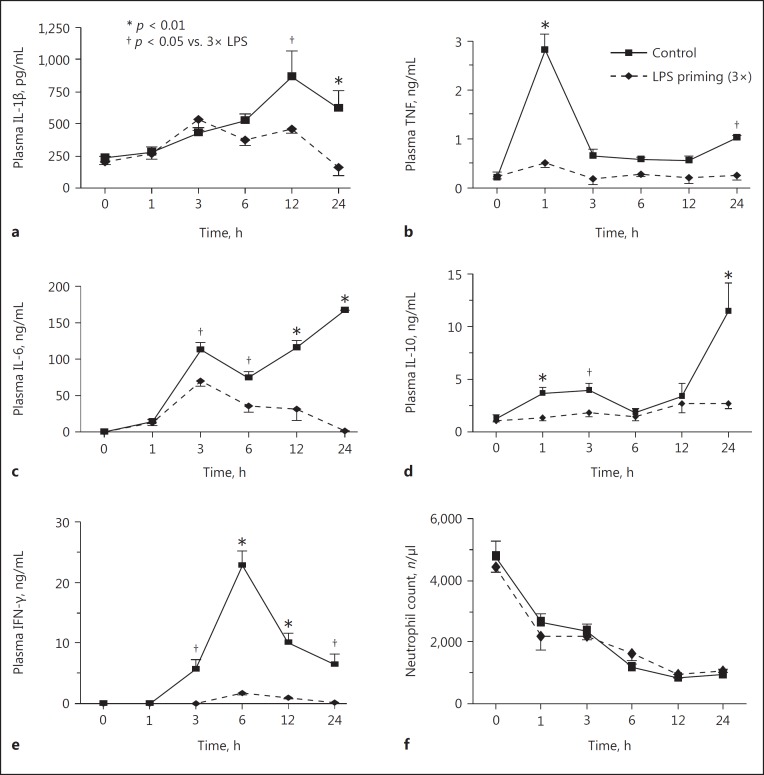

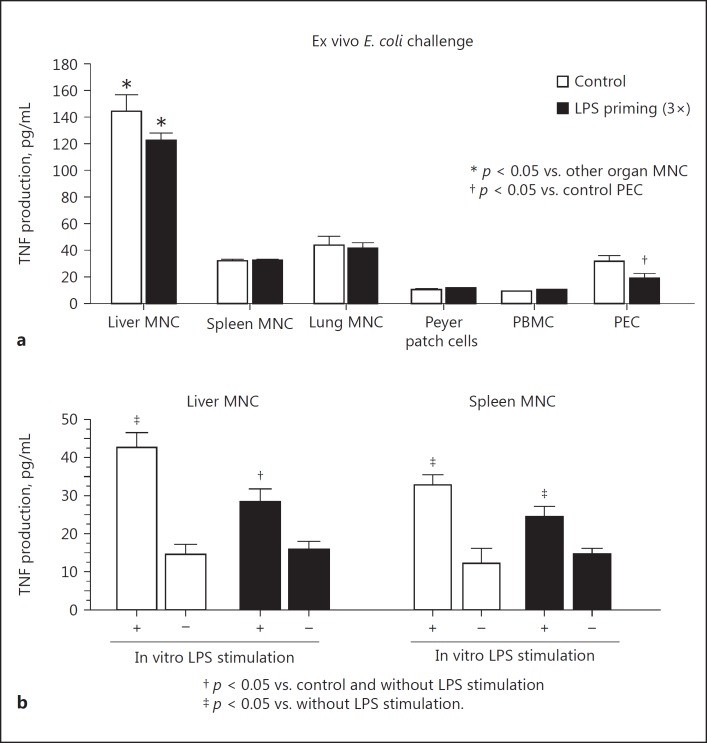

Increased TNF Production Capacity and Bactericidal Activity of Liver MNC

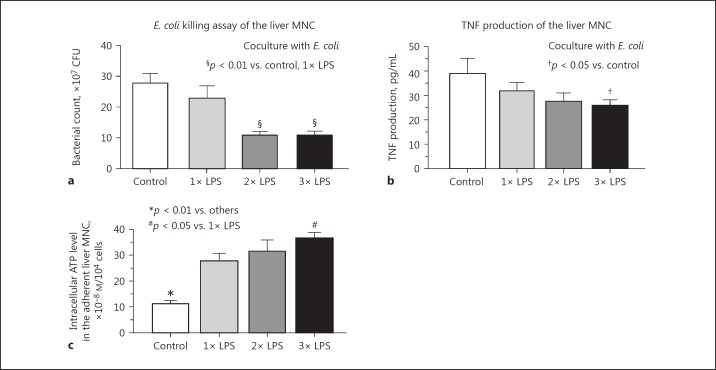

MNC were obtained from the liver, spleen, lung, Peyer patches, peripheral blood, and peritoneal exudates 20 min after E. coli challenge and were incubated for 3 h to evaluate their TNF production capacity. Liver MNC produced substantial amounts of TNF compared to other organ MNC in both LPS-primed and nonprimed control mice, whereas no significant difference was observed in the TNF production of liver MNC in LPS-primed and control mice, or in other organ MNC, with the exception of peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) that were the first macrophages to encounter LPS priming (Fig. 4a). However, when the method of LPS priming was changed to intravenous injections from intraperitoneal injections, the effect of PEC on TNF production disappeared (LPS priming vs. control, 26 ± 5 vs. 29 ± 4 pg/mL, respectively), while marked resistance to E. coli infection was successfully induced. Furthermore, intravenous LPS priming did not affect TNF production by peripheral blood MNC (data not shown). Liver and spleen MNC from the LPS-primed mice still produced a significant amount of TNF in response to in vitro stimulation with a stressful dose of LPS (10 μg/ml), although LPS priming somewhat reduced TNF production by liver MNC (but not spleen MNC) compared to that of the control mice (Fig. 4b). The liver MNC obtained from the mice after 2 or 3 LPS injections (5 μg/kg) injections, but not 1 injection, showed potent bactericidal activities, as assessed by coculture with viable E. coli at an MNC:bacteria ratio of 5:1 (5 × 105 cells to 1 × 105 CFU) (Fig. 5a). Their TNF production was also somewhat reduced (Fig. 5b). However, LPS priming did not affect the bactericidal activity of circulating neutrophils in mice (3× LPS priming vs. control: 329 ± 26 vs. 358 ± 50 CFU, 6-h culture with viable E. coli at a neutrophil:bacteria ratio of 5:1). We examined intracellular ATP levels the adherent liver MNC. LPS priming remarkably increased ATP levels, even after a single LPS injection (Fig. 5c). Moreover, adherent MNC showed significantly higher ATP levels after 3 LPS injections in comparison to after a single injection (Fig. 5c). LPS priming also significantly upregulated the in vivo phagocytic activity of F4/80+ Kupffer cells/macrophages when microspheres were intravenously injected (online suppl. Fig. 1A, method was described in the online supplement) and potently augmented the in vivo phagocytosis of FITC-labeled E. coli by F4/80+ cells in comparison to LPS nonprimed control mice (online suppl. Fig. 1B).

Fig. 4.

The effect of LPS priming on the TNF production in the organ MNC. a LPS-primed (3×) or control mice were challenged with 1 × 109 CFU i.v. of E. coli. After 20 min, indicated organ MNC were obtained from mice and incubated for 3 h to measure TNF production. Basal levels of TNF in liver MNC: LPS-primed mice 37 ± 3 pg/mL, control mice 37 ± 6 pg/mL; basal levels of TNF in lung MNC: LPS-primed mice 19 ± 3 pg/mL, control mice 26 ± 1 pg/mL; basal levels of TNF in spleen MNC: both LPS-primed/control mice 11 ± 1 pg/mL; basal levels of TNF in other MNC: both LPS-primed/control mice <10 pg/mL. b Liver/spleen MNC obtained 1 day after thrice LPS priming were cultured with or without 10 μg/mL LPS for 3 h to measure TNF production. Data are means ± SE from 5 mice in each group. PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PEC, peritoneal exudate cells.

Fig. 5.

The effect of LPS priming on the E. coli killing activity, TNF production, and intracellular ATP levels in the liver MNC. E. coli killing activity at 6 h (a) or TNF production capability at 3 h (b) by liver MNC from the LPS-primed (1× to 3×) and control mice were measured following coculture with E. coli (1 × 105 CFU). c Intracellular ATP levels in the adherent liver MNC from the LPS-primed (1× to 3×) and control mice were measured. Data are means ± SE from 5 mice in each group.

Bacterial Propagation and TNF Production in the Liver of E. coli-Challenged Mice

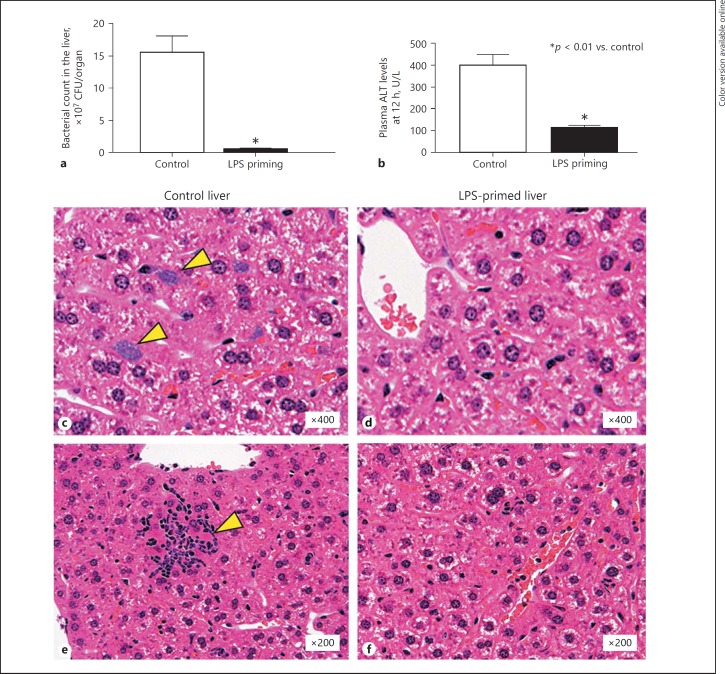

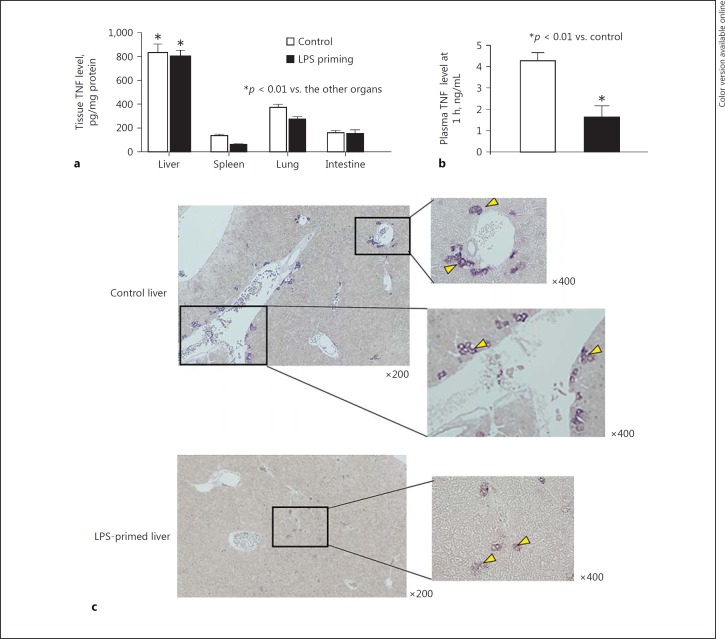

Enhanced bactericidal activity of liver MNC in LPS-primed mice was consistent with a dramatic reduction in the number of viable bacteria in the liver 12 h after an in vivo lethal E. coli challenge compared to control mice (Fig. 6a). Elevation of the plasma ALT levels was also reduced in these LPS-primed mice (Fig. 6b). Control livers showed marked formation of bacterial clots in the sinusoidal space (Fig. 6c, arrows) and hepatocyte necrosis with prominent infiltration of inflammatory cells (Fig. 6e, arrow) 12 h after E. coli challenge, whereas the livers from LPS-primed mice did not show such changes (Fig. 6d, f). Liver TNF levels 1 h after intravenous challenge with E. coli showed significantly higher values than those of other organs (e.g., spleen, lung, and intestine) in both LPS-primed and control mice, and in addition, LPS priming did not reduce liver TNF levels at all compared to control mice (Fig. 7a). Nevertheless, the plasma TNF levels in the hepatic vein (i.e., the drainage vein from the liver) in LPS-primed mice showed markedly lower values than those of control mice (Fig. 7b). Therefore, the efflux of tissue TNF into the systemic circulation via the hepatic vein after E. coli infection was considered to be drastically suppressed, despite the fact that LPS-primed mice produced a considerable amount of TNF in the liver. To determine the localization of TNF-producing cells in the liver, in situ hybridization was performed. Control mice showed an accumulation of TNF mRNA-positive Kupffer cells/macrophages around the central and portal veins (Fig. 7c, control liver, arrows), whereas most TNF mRNA-positive Kupffer cells/macrophages in LPS-primed mice localized to the midzonal area and apart from interlobular portal or central veins (Fig. 7c, LPS-primed liver, arrows). LPS priming thus markedly affected the distribution of TNF-producing cells in the liver after E. coli challenge, thereby reducing the systemic influence of TNF. Moreover, most of Kupffer cells/macrophages from LPS-primed mice showed a much weaker TNF mRNA expression in comparison to control mice.

Fig. 6.

The effect of LPS priming on the bacterial propagation in the liver after E. coli challenge. Bacterial counts in the liver (a), plasma ALT levels (b), and pathological findings of the liver (c–f) 12 h after challenge with E. coli (1 × 109 CFU i.v.) were investigated in LPS-primed (3×) and control mice. Arrowheads indicate the existence of bacterial clots (c) and hepatocyte necrosis with the infiltration of inflammatory cells (e) in the control liver, whereas such changes were not observed in the livers of LPS-primed mice. Data are means ± SE from 5 mice in each group (a, b) and are representative of 5 mice in each group with similar results (c–f).

Fig. 7.

The effect of LPS priming on the TNF levels in the tissues and hepatic vein and the distribution of TNF-producing cells in the liver after E. coli challenge. a Tissue TNF levels in LPS-primed/control mice 1 h after E. coli challenge. b Plasma TNF levels in the hepatic vein 1 h after E. coli challenge. c Distribution of TNF mRNA-positive Kupffer cells in the liver 1 h after E. coli challenge. Arrowheads indicate cells with positive staining for TNF mRNA. Data are means ± SE from 5 mice in each group (a, b) and representative of 5 mice in each group with similar results (c).

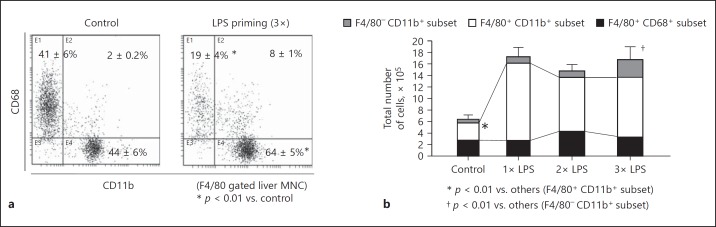

Alterations in CD11b+ and CD68+ Subsets in Liver F4/80+ Cells after LPS Priming

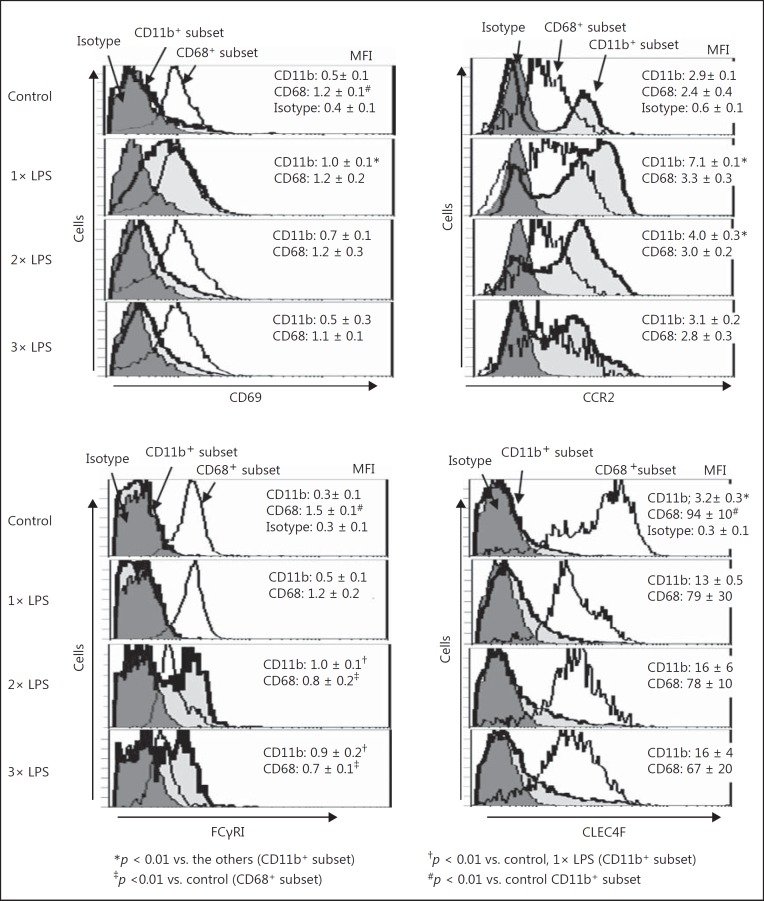

To further characterize liver macrophages from LPS-primed mice, flow-cytometric analyses were performed. LPS priming markedly increased the proportion of CD11b+ subset in F4/80+ cells in the liver, whereas the CD68+ subset was predominant in F4/80+ cells from control mice (Fig. 8a). The CD68+ subset showed a higher intensity of F4/80 than the CD11b+ subset in both the LPS-primed and nonprimed control mice (mean flow intensity [MFI] of F4/80; 4.9 ± 0.1 vs. 2.4 ± 0.3 in LPS-primed mice and 4.9 ± 0.4 vs. 2.0 ± 0.3 in control mice, p < 0.01). The total numbers of F4/80+ cells in the mouse liver were markedly increased even after a single LPS priming, and the increased numbers were maintained after 2× or 3× LPS priming (Fig. 8b). This increase in liver F4/80+ cells was mainly ascribed to an increased number of cells in the CD11b+ subset (Fig. 8b). F4/80− CD11b+ cells were also increased in the liver after 3× LPS priming (Fig. 8b), suggesting that neutrophils accumulated in the liver due to repetitive LPS priming. However, F4/80− CD11b+ cells still represented a smaller population than that of the F4/80+ CD11b+ cells in the liver after 3× LPS priming. F4/80+ CD11b+ cells markedly upregulated the expression of CD69 and CCR2 after a single LPS priming (Fig. 9a, b). The plasma monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) levels were also elevated in mice after a single LPS priming (online suppl. Fig. 2A). The CD11b+ subset may infiltrate the liver via MCP-1/CCR2. However, after 2× or 3× LPS priming, the CD11b+ subset downregulated the expression of CD69 and CCR2 (Fig. 9a, b) but strongly upregulated the expression of Fcγ receptor I (FcγRI) (Fig. 9c). The functional alteration in the CD11b+ subset may occur through repeated LPS priming. The expression of CD69 in the CD68+ subset of control mice was higher than that in the CD11b+ subset, but expression was neither drastically altered after LPS priming nor was their number or expression of CCR2 (Fig. 9a, b). The CD68+ cells in control mice also showed a significantly higher expression of FcγRI than the CD11b+ cells; however, their expression of FcγRI was gradually downregulated as the number of LPS primings increased (Fig. 9c). Interestingly, the expression of C-type lectin domain family 4 member F (CLEC4F) in the CD68+ subset was remarkably higher than that in the CD11b+ subset; however, the CLEC4F expression was not significantly changed by LPS priming in either the CD68+ or CD11b+ subsets (Fig. 9d).

Fig. 8.

CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets in liver F4/80+ cells and alteration in their numbers after 1×, 2×, and 3× LPS priming. a Proportion of the CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets in F4/80+ cells were investigated in LPS-primed/control mice. b Total numbers of the CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets in F4/80+ cells and CD11b+ F4/80− cells were also investigated after 1×, 2×, and 3× LPS priming. Representative data of 5 mice in each group with similar results are shown (a). Data are means ± SE from the 5 mice in each group (a, b).

Fig. 9.

Expression of CD69, CCR2, FcγRI, and CLEC4F on the CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets in liver F4/80+ cells after 1×, 2×, and 3× LPS priming. The expression of CD69 (a), CCR2 (b), FcγRI (c), and CLEC4F (d) on the CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets in F4/80+ cells was examined in the LPS-primed (1× to 3×) and control mice. Data are representative of 5 mice in each group with similar results and means ± SE from the 5 mice in each group.

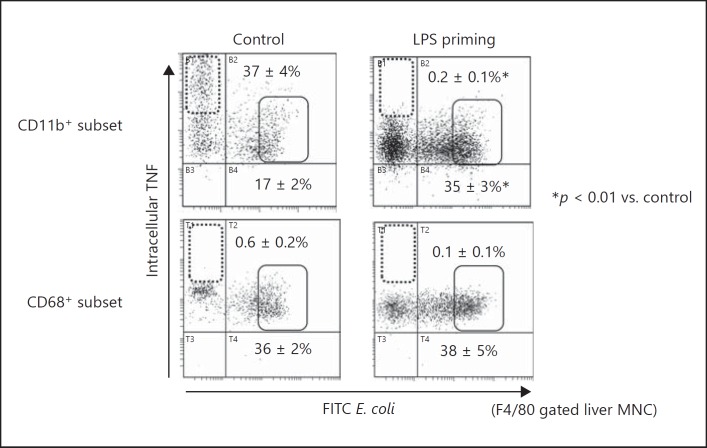

Roles of the CD11b+ Subset in Liver F4/80+ Cells in Bacterial Phagocytosis and TNF Production

Next, we investigated the roles of CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets in liver F4/80+ cells from LPS-primed mice in bacterial clearance in vivo. The CD11b+ subset in liver F4/80+ cells from control mice after E. coli infection showed both fractions of active phagocytosis with low TNF production (Fig. 10 upper left panel, solid square) and high TNF production without phagocytic activity (Fig. 10 upper left panel, dotted square). In contrast, the CD11b+ subset cells from LPS-primed mice exclusively showed low TNF production with strong phagocytic activity (Fig. 10, upper right panel, solid square). Thus, following LPS priming, the role of CD11b+ cells shifted from inflammatory responses via the production of TNF to bacterial clearance by increasing the fraction with active phagocytosis. Notably, there was no CD11b+ subset fraction that showed both high TNF production capacity and active phagocytosis. Therefore, TNF production and phagocytosis were considered to be independently regulated by distinct CD11b+ subpopulations. Regarding the phagocytic activity of the CD68+ subset in hepatic F4/80+ cells, no obvious difference was observed between control and LPS-primed mice. Additionally, no fraction of CD68+ cells demonstrated high TNF-producing capacity (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Simultaneous analysis of E. coli phagocytosis and TNF production in the CD11b+ and CD68+ liver F4/80+ cells. A simultaneous analysis of intracellular TNF levels and phagocytic activity against FITC-labeled E. coli was achieved by multi-colored flow cytometry. In LPS-primed mice, the disappearance of a high TNF fraction in the CD11b+ subset is remarkable. Dotted squares indicate the cells with high TNF production but no phagocytic activity, and solid squares indicate the cells with low TNF production but potent phagocytosis. Data are representative of 5 mice in each group with similar results and show means ± SE from the 5 mice in each group.

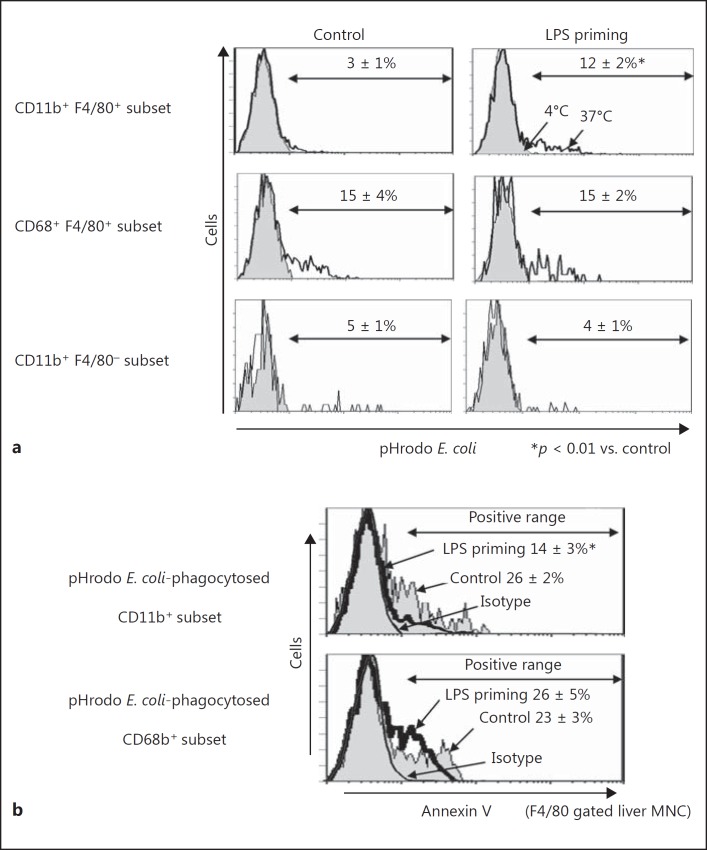

Enhanced Phagolysosome Formation in the CD11b+ Subset of Liver F4/80+ Cells from LPS-Primed Mice

Analysis using pHrodo-conjugated E. coli revealed that phagolysosome formation was upregulated in the CD11b+ subset of liver F4/80+ cells by LPS priming (Fig. 11a). Because the bactericidal activity inside Kupffer cells is strongly dependent on the fusion of phagosomes with lysosomes to make activated phagolysosomes, enhanced pHrodo fluorescence in CD11b+ cells from LPS-primed mice showed that they are the main fraction which takes charge of bacterial clearance in systemic infection. Although the CD68+ subset also showed active phagocytosis against pHrodo-conjugated E. coli, the proportion of positive cells did not differ between LPS-primed and control mice (Fig. 11a). F4/80− CD11b+ cells in the liver did not upregulate phagocytosis of pHrodo-conjugated E. coli by LPS priming (Fig. 11a). In addition, the CD11b+ subset in F4/80+cells phagocytosing pHrodo-conjugated E. coli in the LPS-primed mice showed much weaker reactivity to annexin V than those in the control mice (Fig. 11b). However, there was no obvious difference in the reactivity to annexin V between CD68+ subset cells from LPS-primed mice and those from control mice. Thus, LPS priming recruited a distinct CD11b+ fraction that showed augmented phagocytosis and bactericidal activity with resistance to apoptosis. Strong resistance to systemic bacterial infection in LPS-primed mice was considered to be explained by the existence of this distinct CD11b+ fraction.

Fig. 11.

Digestion of pHrodo-conjugated E. coli in CD11b+ and CD68+ subset cells and annexin V staining. a Liver MNC were incubated with pHrodo-E. coli for 30 min at 37 or 4°C (as a negative control) to examine the digestion of pHrodo-E. coli by flow cytometry. b Annexin V staining in the pHrodo E. coli-phagocytosing CD11b+ or CD68+ subsets. After incubation with pHrodo-E. coli, the cells were stained with FITC-labeled annexin V for examination by flow cytometry. Data are representative of 5 mice in each group with similar results and show means ± SE from the 5 mice in each group.

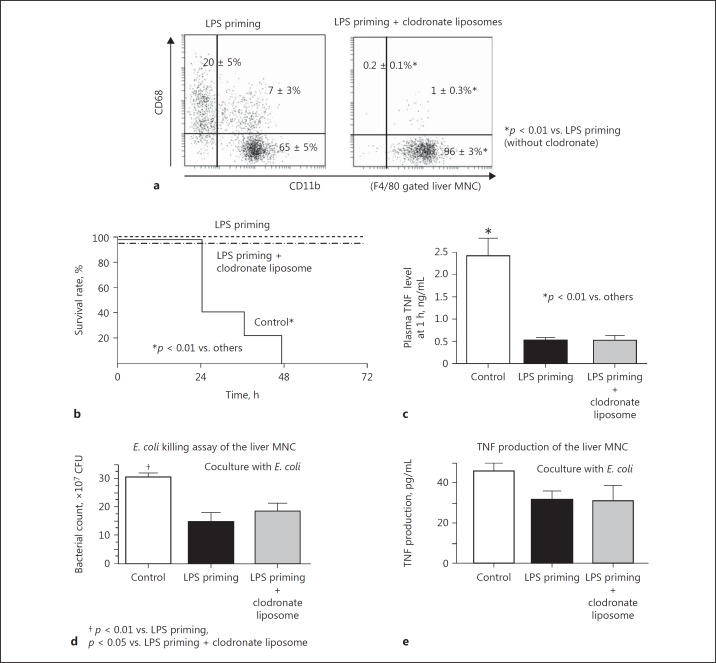

Depletion of the CD68+ Subset in Liver F4/80+ Cells with Clodronate Liposomes Does Not Affect LPS Tolerance

To further examine the roles of the CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets in liver F4/80+ cells of LPS-primed mice, liposome-encapsulated clodronate injection was employed. Clodronate liposomes almost completely depleted CD68+ subset from the liver, while the CD11b+ subset remained as a main fraction in LPS-primed mice (Fig. 12a). This result was consistent with previous reports [9, 10, 18]. Despite the depletion of the CD68+ subset in the liver, LPS-primed mice still showed strong resistance to a lethal bacterial challenge (Fig. 12b), and the plasma TNF response to bacterial infection was effectively suppressed (Fig. 12c). The liver MNCs obtained from LPS-primed mice injected with clodronate liposomes still showed significant bactericidal activity and a certain degree of TNF production by coculture with E. coli, similarly to the LPS-primed mice that did not receive clodronate treatment (Fig. 12d, e).

Fig. 12.

The effects of treatment with clodronate liposomes on LPS-primed mice. The CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets in liver F4/80+ cells of the LPS-primed mice with or without clodronate liposome treatment (a). LPS-primed mice with or without clodronate liposome treatment and control mice were challenged with E. coli (1 × 109 CFU i.v.) to examine the survival (b) and plasma TNF levels at 1 h (c). Liver MNC were obtained from the LPS-primed mice (with or without clodronate liposome treatment) and control mice and were cocultured with E. coli (1 × 105 CFU) to examine bactericidal activity at 6 h (d) or the TNF production capability at 3 h (e). Data are means ± SE from 5 mice (a, d, e) or 10 mice (b, c) in each group and representative of 5 mice in each group with similar results (a).

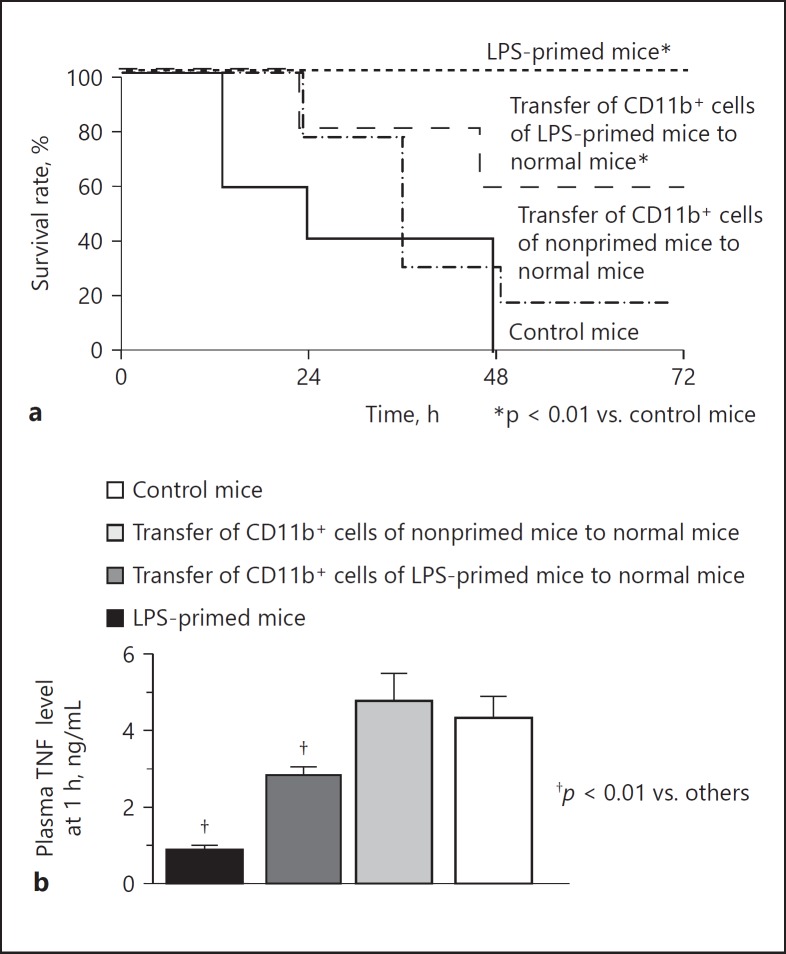

Adoptive Transfer of CD11b+ Adherent Liver MNC from LPS-Primed Mice to Control Mice Induces Partial LPS Tolerance

The CD11b+ cells were magnetically sorted from the adherent liver MNC of LPS-primed mice (F4/80 positivity: 80%, online suppl. Fig. 3) or nonprimed control mice (F4/80 positivity: 81%) and were transferred to normal mice. F4/80-negative cells were mainly neutrophils (online suppl. Fig. 3). An E. coli challenge was then performed. The transfer of the CD11b+ adherent liver MNC from the LPS-primed mice significantly increased the survival of the mice after the E. coli challenge in comparison to nontransferred control mice (Fig. 13a), while the transfer of the CD11b+ cells from the nonprimed mice did not significantly increase mouse survival after the bacterial challenge. Interestingly, the transfer of CD11b+ cells from the LPS-primed mice significantly suppressed the elevation of plasma TNF in mice 1 h after the E. coli challenge, whereas the transfer of the CD11b+ cells from the nonprimed mice did not affect the plasma TNF after the bacterial challenge (Fig. 13b). These results support the notion that CD11b+ monocyte-derived macrophages are a key fraction in the induction of LPS tolerance and play a major role in resistance to bacterial infection.

Fig. 13.

The effect of the adoptive transfer of CD11b+ adherent liver MNC from LPS-primed mice on bacterial infection. CD11b+ adherent liver MNC were obtained from the LPS-primed or nonprimed mice and transferred to normal mice. An E. coli challenge (1 × 109 CFU) was then performed to examine survival (a) and the plasma TNF levels at 1 h (b). LPS-primed mice and nonprimed control mice without receiving cell transfer treatment were subjected to a similar intravenous challenge with E. coli. Data are means ± SE from 10 mice in each group.

Expression of TLR4 and TNF Receptors on Liver F4/80+ Cells in LPS-Primed Mice and Plasma MCP-1, TNF, and CRP Levels in Response to Priming Injection with LPS

Details on plasma MCP-1, TNF, and CRP levels in response to priming injection with LPS expression of TLR4 and TNF receptors on liver F4/80+ cells in LPS-primed mice are shown in the online supplementary materials and Figures.

Discussion

During phagocytosis of bacterial pathogens, activated macrophages typically produce a certain amount of TNF, which is crucial for the effective elimination of troublesome bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis[19] or Streptococcus pneumoniae[20]. However, it is well known that high levels of circulating TNF deteriorate septicemia. Thus, too much TNF production is not a good sign in the host with systemic infection. In this study, LPS-tolerant mice showed significantly reduced plasma TNF levels after E. coli challenge but maintained a dramatic enhancement of bactericidal activity of CD11b+-recruited macrophages. Kupffer cells/macrophages with potent TNF-producing capacity did not emerge after E. coli challenge in LPS-primed mice; however, both CD11b+ and CD68+ subsets of Kupffer cells/macrophages retained TNF-producing capabilities to a certain degree. Interestingly, the outflow of TNF into the systemic circulation was markedly suppressed, thus TNF-induced deterioration of the host condition was considered to be suppressed to an insignificant level.

The heterogeneity of macrophages has been noted by many investigators and they are generally classified into two distinct populations, tissue-resident macrophages that are F4/80high and bone marrow-derived monocytes/macrophages that are F4/80low[18, 21, 22, 23, 24]. The former is also CD11blow, while the latter are CD11bhigh. Interestingly, Davies et al. [22] demonstrated that the F4/80high (CD11blow) macrophages in the liver are CD68+ while the F4/80low (CD11bhigh) macrophages are not. We have also classified F4/80+ Kupffer cells/macrophages into two subtypes of different lineages, a CD68+ subset with strong phagocytic activity (tissue resident) and a CD11b+ subset with potent proinflammatory cytokine-producing capability (bone marrow derived) [9, 10]. Consistent with the report of Davies et al. [22], the CD68+ subset was F4/80high but the CD11b+ subset was F4/80low. Hettinger et al. [18] demonstrated that clodronate liposomes delete the F4/80high CD11blow subset but not the F4/80low CD11bhigh subset. We have also demonstrated that the clodronate liposomes delete the CD68+ subset but not the CD11b+ subset (Fig. 6a) [9, 10]. Taken together with these findings, the F4/80high CD68+ subset in the present study is presumably similar to the F4/80high CD11blow subset, which is considered to be composed of tissue-resident Kupffer cells, and the F4/80low CD11b+ subset is similar to the F4/80low CD11bhigh subset, which is considered to be composed of the monocyte-derived macrophages in the liver. Additionally, Klein et al. [21] demonstrated that tissue-resident (sessile) Kupffer cells are radioresistant while monocyte-derived macrophages are radiosensitive. The CD68+ subset is also radioresistant but the CD11b+ subset is radiosensitive [25]. The authors of the present study and many other investigators believe that tissue-resident Kupffer cells are involved in the clearance of microorganisms while the monocyte-derived macrophages are involved in the induction of inflammation and play a role in immune surveillance [22].

In vivo LPS tolerance almost completely depleted a CD11b+ subfraction which showed potent TNF-producing capability but lacked phagocytic activity (Fig. 10 upper right panel, dotted square). According to the results of the immunohistochemical analysis, we speculate that CD11b+ monocyte-derived macrophages are located in the perivascular/periportal area in normal mice and produce substantial amounts of TNF in response to bacterial stimuli. TNF produced by these CD11b+ perivascular macrophages may efflux into the systemic circulation and also plays a role in activating the phagocytic function of CD68+ tissue-resident Kupffer cells that are located in the midzonal area [9, 10]. TNF activates liver macrophages via NF-κB activation in the presence of IFN-γ, which is plentifully produced in the infected liver [26, 27]; the activated macrophages then enhance the phagocytic activity against microorganisms. The secretion of TNF and the phagocytic activity of the activated macrophages are closely related to each other [6]. As previously reported, CD11b+ monocyte-derived macrophages recruited from the bone marrow have an immune surveillance function [21, 22], and exaggerated TNF production by these cells may on occasion cause severe inflammation and tissue damage in the host [12, 28, 29].

Under conditions of LPS tolerance, however, such CD11b+ liver macrophages with potent TNF-producing capacity were not seen in the perivascular/periportal area. In contrast, the TNF-producing liver macrophages (albeit weak TNF mRNA expression) were increased in number and located in the midzonal area in LPS-tolerant mice (Fig. 7c). In addition, after large amounts of E. coli challenge the plasma ALT levels were decreased in these mice (Fig. 6b), suggesting that hepatocytes remain relatively intact after severe infection. The TNF produced by the midzone macrophages may have been consumed by the surrounding hepatocytes in order to protect against hepatocyte injury and prevent TNF spillover into the circulation. TNF is known to be either hepatotoxic or hepatoprotective, depending on the condition of the liver [30, 31]. Consistently, TNF in the liver of LPS-tolerant mice may enhance the reactivity of CRP production to E. coli challenge (online suppl. Fig. 2D), suggesting that hepatocytes effectively use/consume TNF to produce acute-phase proteins. These findings could explain why LPS tolerance reduces the TNF levels in the hepatic vein and sera and suppresses systemic inflammatory responses after intravenous bacterial challenge. However, in LPS-primed mice, the CD11b+ subset as well as the CD68+ subset in liver F4/80+ cells still showed a certain (albeit weak) TNF-producing capability. Therefore, appropriate amounts of TNF may be required for Kupffer cells/macrophages to exhibit effective phagocytic activities against bacteria.

Although in vivo LPS tolerance did not significantly affect the number or function of the CD68+ subset in liver F4/80+ cells, it dramatically affected the ability of the CD11b+ subset both quantitatively and qualitatively. Several investigators have suggested that monocyte-derived macrophages can replace tissue-resident macrophages and may do so under certain inflammatory conditions [18, 22, 23]. Previously, we also found that mouse CD11b+ liver macrophages acquire the phagocytic activity after E. coli challenge [9]. LPS tolerance actually changed the predominant Kupffer cell/macrophage fraction from the CD68+ subset to the CD11b+ subset. The CD11b+ subset from LPS-primed mice gained both phagocytic and bactericidal activities; however, this was associated with reduced TNF-producing capability.

LPS tolerance downregulates TLR4 expression on Kupffer cells/macrophages [32, 33], thus indicating their hyporesponsiveness to LPS. Although in vivo LPS tolerance dramatically reduced the inflammatory response to LPS challenge or bacterial infection, it was not an immunosuppressive condition because adherent liver MNC (macrophages) showed a significant increase in their ATP levels, and CD11b+ liver macrophages showed a potent phagocytic/bactericidal activity. Severe stress, such as burn injury, may also reduce the inflammatory responses to bacterial infections [34]. However, such stress is quite different from in vivo LPS tolerance since Kupffer cells/macrophages after burn injury show a markedly reduced phagocytic activity and contribute to the aggravation of infectious diseases [11].

Contradictory results are intermingled in LPS tolerance. While LPS priming stimulates intracellular signaling through TLR4 [35] and upregulates the phagocytic function in CD11b+ macrophages, LPS-TLR4 signaling is presumably diminished in these cells after the induction of LPS tolerance, and the production of TNF via the NF-κB pathway is strongly suppressed [2, 33, 36]. However, the phagocytic activity of CD11b+ liver macrophages is upregulated by the enhanced FcγRI expression [8]. Using an in vitro LPS-tolerant model, Foster et al. [37] elegantly demonstrated that TLR4-induced genes were divided into two categories according to their functional status; genes encoding proinflammatory mediators were transiently inactivated in bone marrow-derived mouse macrophages, whereas the expression of genes that encode antimicrobial effectors was preserved in LPS-tolerant macrophages. Thus, LPS tolerance is shown to induce “gene reprogramming” rather than downregulation of LPS-related genes.

The LPS dose used to induce in vivo tolerance in the present study was only 5 μg/kg, which was much lower than that of the previous reports. Nevertheless, even the administration of 2–4 ng/kg LPS evoked various inflammatory responses in healthy human volunteers [38, 39], suggesting that humans are extremely sensitive to LPS compared to mice. Because in vitro LPS tolerance was successfully induced using peripheral blood monocytes from healthy donors [40], it is theoretically possible to induce in vivo LPS tolerance in humans. From a therapeutic aspect, in vivo LPS tolerance may be beneficial for augmenting host resistance against infections, in particular in immunocompromised hosts, although the establishment of a safe LPS tolerance induction procedure is crucial for preventing undesirable systemic inflammatory responses.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI grant No. 25293369 (M.K. and S.S.).

References

- 1.Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Endotoxin tolerance: new mechanisms, molecules and clinical significance. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho PC, Tsui YC, Feng X, Greaves DR, Wei LN. NF-κB-mediated degradation of the coactivator RIP140 regulates inflammatory responses and contributes to endotoxin tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:379–386. doi: 10.1038/ni.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tracey KJ, Beutler B, Lowry SF, Merryweather J, Wolpe S, Milsark IW, Hariri RJ, et al. Shock and tissue injury induced by recombinant human cachectin. Science. 1986;234:470–474. doi: 10.1126/science.3764421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Poll T, Buller HR, ten Cate H, Wortel CH, Bauer KA, van Deventer SJ, Hack CE, et al. Activation of coagulation after administration of tumor necrosis factor to normal subjects. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1622–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006073222302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavaillon JM, Adib-Conquy M. Bench-to-bedside review: endotoxin tolerance as a model of leukocyte reprogramming in sepsis. Crit Care. 2006;10:233. doi: 10.1186/cc5055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray RZ, Kay JG, Sangermani DG, Stow JL. A role for the phagosome in cytokine secretion. Science. 2005;310:1492–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1120225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham E, Wunderink R, Silverman H, Perl TM, Nasraway S, Levy H, Bone R, et al. Efficacy and safety of monoclonal antibody to human tumor necrosis factor alpha in patients with sepsis syndrome. A randomized, controlled, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial. TNF-alpha MAb Sepsis Study Group. JAMA. 1995;273:934–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.del Fresno C, Garcia-Rio F, Gomez-Pina V, Soares-Schanoski A, Fernandez-Ruiz I, Jurado T, Kajiji T, et al. Potent phagocytic activity with impaired antigen presentation identifying lipopolysaccharide-tolerant human monocytes: demonstration in isolated monocytes from cystic fibrosis patients. J Immunol. 2009;182:6494–6507. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinoshita M, Uchida T, Sato A, Nakashima M, Nakashima H, Shono S, Habu Y, et al. Characterization of two F4/80-positive Kupffer cell subsets by their function and phenotype in mice. J Hepatol. 2010;53:903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikarashi M, Nakashima H, Kinoshita M, Sato A, Nakashima M, Miyazaki H, Nishiyama K, et al. Distinct development and functions of resident and recruited liver Kupffer cells/macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:1325–1336. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0313144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inatsu A, Kinoshita M, Nakashima H, Shimizu J, Saitoh D, Tamai S, Seki S. Novel mechanism of C-reactive protein for enhancing mouse liver innate immunity. Hepatology. 2009;49:2044–2054. doi: 10.1002/hep.22888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakashima H, Kinoshita M, Nakashima M, Habu Y, Shono S, Uchida T, Shinomiya N, et al. Superoxide produced by Kupffer cells is an essential effector in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis in mice. Hepatology. 2008;48:1979–1988. doi: 10.1002/hep.22561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ami K, Kinoshita M, Yamauchi A, Nishikage T, Habu Y, Shinomiya N, Iwai T, et al. IFN-gamma production from liver mononuclear cells of mice in burn injury as well as in postburn bacterial infection models and the therapeutic effect of IL-18. J Immunol. 2002;169:4437–4442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinoshita M, Miyazaki H, Ono S, Inatsu A, Nakashima H, Tsujimoto H, Shinomiya N, et al. Enhancement of neutrophil function by interleukin-18 therapy protects burn-injured mice from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2670–2680. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01298-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinoshita M, Uchida T, Nakashima H, Ono S, Seki S, Hiraide H. Opposite effects of enhanced tumor necrosis factor-alpha production from Kupffer cells by gadolinium chloride on liver injury/mortality in endotoxemia of normal and partially hepatectomized mice. Shock. 2005;23:65–72. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000144423.40270.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiroi S, Nakanishi K, Kawai T. Expressions of human telomerase mRNA component (hTERC) and telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) mRNA in effusion cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:212–216. doi: 10.1002/dc.10352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyazaki H, Kinoshita M, Ono S, Nakashima M, Hara E, Ohno H, Seki S, et al. Augmented bacterial elimination by Kupffer cells after IL-18 pretreatment via IFN-gamma produced from NK cells in burn-injured mice. Burns. 2011;37:1208–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hettinger J, Richards DM, Hansson J, Barra MM, Joschko AC, Krijgsveld J, Feuerer M. Origin of monocytes and macrophages in a committed progenitor. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:821–830. doi: 10.1038/ni.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bean AG, Roach DR, Briscoe H, France MP, Korner H, Sedgwick JD, Britton WJ. Structural deficiencies in granuloma formation in TNF gene-targeted mice underlie the heightened susceptibility to aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, which is not compensated for by lymphotoxin. J Immunol. 1999;162:3504–3511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wellmer A, Gerber J, Ragheb J, Zysk G, Kunst T, Smirnov A, Bruck W, et al. Effect of deficiency of tumor necrosis factor alpha or both of its receptors on Streptococcus pneumoniae central nervous system infection and peritonitis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6881–6886. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6881-6886.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein I, Cornejo JC, Polakos NK, John B, Wuensch SA, Topham DJ, Pierce RH, et al. Kupffer cell heterogeneity: functional properties of bone marrow derived and sessile hepatic macrophages. Blood. 2007;110:4077–4085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:986–995. doi: 10.1038/ni.2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epelman S, Lavine KJ, Randolph GJ. Origin and functions of tissue macrophages. Immunity. 2014;41:21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheng J, Ruedl C, Karjalainen K. Most tissue-resident macrophages except microglia are derived from fetal hematopoietic stem cells. Immunity. 2015;43:382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakashima H, Nakashima M, Kinoshita M, Ikarashi M, Miyazaki H, Hanaka H, Imaki J, et al. Activation and increase of radio-sensitive CD11b+ recruited Kupffer cells/macrophages in diet-induced steatohepatitis in FGF5 deficient mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34466. doi: 10.1038/srep34466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parameswaran N, Patial S. Tumor necrosis factor-α signaling in macrophages. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2010;20:87–103. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v20.i2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wesemann DR, Benveniste EN. STAT-1 alpha and IFN-gamma as modulators of TNF-alpha signaling in macrophages: regulation and functional implications of the TNF receptor 1:STAT-1 alpha complex. J Immunol. 2003;171:5313–5319. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakashima H, Ogawa Y, Shono S, Kinoshita M, Nakashima M, Sato A, Ikarashi M, et al. Activation of CD11b+ Kupffer cells/macrophages as a common cause for exacerbation of TNF/Fas-ligand-dependent hepatitis in hypercholesterolemic mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e49339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato A, Nakashima H, Nakashima M, Ikarashi M, Nishiyama K, Kinoshita M, Seki S. Involvement of the TNF and FasL produced by CD11b Kupffer cells/macrophages in CCl4-induced acute hepatic injury. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webber EM, Bruix J, Pierce RH, Fausto N. Tumor necrosis factor primes hepatocytes for DNA replication in the rat. Hepatology. 1998;28:1226–1234. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishiyama K, Nakashima H, Ikarashi M, Kinoshita M, Nakashima M, Aosasa S, Seki S, et al. Mouse CD11b+Kupffer Cells Recruited from Bone Marrow Accelerate Liver Regeneration after Partial Hepatectomy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomura F, Akashi S, Sakao Y, Sato S, Kawai T, Matsumoto M, Nakanishi K, et al. Cutting edge: endotoxin tolerance in mouse peritoneal macrophages correlates with down-regulation of surface toll-like receptor 4 expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:3476–3479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medvedev AE, Lentschat A, Wahl LM, Golenbock DT, Vogel SN. Dysregulation of LPS-induced Toll-like receptor 4-MyD88 complex formation and IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 activation in endotoxin-tolerant cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:5209–5216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinoshita M, Miyazaki H, Ono S, Seki S. Immunoenhancing therapy with interleukin-18 against bacterial infection in immunocompromised hosts after severe surgical stress. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93:689–698. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1012502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medvedev AE, Kopydlowski KM, Vogel SN. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction in endotoxin-tolerized mouse macrophages: dysregulation of cytokine, chemokine, and toll-like receptor 2 and 4 gene expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:5564–5574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foster SL, Hargreaves DC, Medzhitov R. Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin modifications. Nature. 2007;447:972–978. doi: 10.1038/nature05836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suffredini AF, Fromm RE, Parker MM, Brenner M, Kovacs JA, Wesley RA, Parrillo JE. The cardiovascular response of normal humans to the administration of endotoxin. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:280–287. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908033210503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Deventer SJ, Buller HR, ten Cate JW, Aarden LA, Hack CE, Sturk A. Experimental endotoxemia in humans: analysis of cytokine release and coagulation, fibrinolytic, and complement pathways. Blood. 1990;76:2520–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dominguez-Nieto A, Zentella A, Moreno J, Ventura JL, Pedraza S, Velazquez JR. Human endotoxin tolerance is associated with enrichment of the CD14+ CD16+ monocyte subset. Immunobiology. 2015;220:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data