ABSTRACT

Senescence is activated in response to chemotherapy to prevent the propagation of cancer cells. In transformed cells, recent studies have shown that this response is not always definitive and that persistent populations can use senescence as an adaptive pathway to restart proliferation and become more aggressive. Here we discuss the results showing that an incomplete and heterogeneous senescence response plays a key role in chemotherapy resistance. Surviving to successive chemotherapy regimens, chronically existing senescent cells can create a survival niche through paracrine cooperations with neighboring cells. This favors chemotherapy escape of premalignant clones but might also allow the survival of adjacent clones presenting a lower fitness. A better characterization of senescence heterogeneity in transformed cells is therefore necessary. This will help us to understand this incomplete response to therapy and how it could generate clones with increased tumor capacity leading to disease relapse.

KEYWORDS: Chemotherapy, senescence, tumor escape, drug resistance, cancer relapse

Senescence as a tumor suppressor mechanism

Abnormal oncogenic pathways activate two tumor suppressive mechanisms, senescence and apoptosis. Whereas apoptosis leads to programmed cell death, senescence causes an irreversible cessation of proliferation [1,2]. This was initially described by Leonard Hayflick who showed that primary cells have a limited proliferative capacity and this was latter linked to telomere erosion. As a consequence of DNA damage, replicative senescence leads to a permanent state of proliferative arrest. This prevents the appearance of abnormal cells during aging. Subsequent studies extended these observations, showing that Oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) is activated at the early steps of neoplasia to prevent the propagation of malignant cells. Induced by oncogenes such as Ras, Raf or following PTEN inactivation, OIS results from the DNA double strand breaks generated by replicative stress [3].

Several studies have described this suppression [4], in vitro, in animal models or in human tissues such as naevi expressing the B-RAFV600E oncogene [5]. Its activation at the initial steps of cell transformation was demonstrated by the use of knockin mice expressing a reporter gene under the control of the CDKN2A promoter. Luminescence identified the early neoplastic growth of mammary cells expressing the SV40 large T oncogene [6]. Animal models were also used to demonstrate that senescence has to be inactivated during cancer progression. Mice lacking functional p16 but retaining p19Arf are tumor prone, demonstrating that senescence plays a key role in tumor suppression [7]. In the intestine, whereas K-ras overexpression induces only hyperplasia, the progression into invasive carcinoma occurs only when the Ink4/Arf locus is deleted [8]. In prostate tissue, inactivation of the PTEN phosphatase leads to a constitutive activation of Akt but any abnormal proliferation is restrained by senescence. Invasive and lethal prostate cancer only occurs following p53 inactivation and the resulting inhibition of senescence [9].

This tumor suppression relies on the activation of the p53-p21 and p16-Rb pathways which induce senescence through cyclin/cdk downregulation and E2F inhibition. The resulting association of Rb with E2F on proliferative genes leads to the formation of heterochromatin structures known as Senescence Associated Heterochromatin Foci (SAHFs [10],). These foci result from the association between Rb and HP1, DNMT1 or the Suv39 methyl-transferase which deposits repressive marks on chromatin, leading to the downregulation of E2F targets. SAHF formation also relies on two other chromatin regulators, HIRA and ASF1 which together with HP1-gamma are necessary for heterochromatin formation [11]. Provided that these modifications are stable (see below), these epigenetic modifications of proliferative promoters allow the long term maintenance of senescence.

Beside SAHFs, senescence is also characterized by the formation of persistant nuclear foci or DNA-SCARS (DNA segments with chromatin alterations reinforcing senescence). Senescence is most of the time activated by DNA damage, either as a consequence of telomere attrition, replicative stress and of genotoxic treatment in the context of CIS. Classical DNA damage generates early foci which are generally detected by gamma H2Ax or 53BP1 staining. These structures disappear rapidly when DNA repair is successful. During senescence, DNA damage induces the formation of DNA-SCARS which are different from these classical foci since they persist for several days [12]. They probably correspond to DNA breaks that are more difficult to repair. These late foci do not contain signs of active DNA repair and they are progressively located in close proximity to PML nuclear bodies. Interestingly, activated forms of p53 and chk2 are associated with these DNA-SCARS and this localization seems to induce a constant activation of p53. A correct assembly of DNA-SCARS is also necessary to maintain senescence and induce the production of inflammatory cytokines (see below). These persistent nuclear foci therefore connect DNA damage, p53 activation and inflammation during senescence. In addition to SAHFs and PML nuclear bodies, they are now considered as the main nuclear markers activated during senescence.

Senescent cells are also characterized by a reduced integrity of the nuclear envelope which is explained by the downregulation of lamin B1. As a result of this increased permeability, cytoplasmic chromatin fragments (CCFs) containing a tri-methylated form of H3K37 are extruded in the cytoplasm where they bind the p62 adaptor protein and are degraded by autophagy [13]. Detected in the cytoplasm by the cGAS-STING DNA sensing pathway, these abnormal CCFs lead to NF-kB activation and production of a specific secretome known as the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype or SASP [14]. The SASP is also regulated at the transcriptional level by the C/EBP transcription factor [15] or at the level of mRNA stability by mTOR and the RNA-binding protein ZFP36L1 [16]. This secretome maintains the proliferative arrest through an autocrine loop but some of its components also transmit this suppressive signal to neighboring cells [17]. In addition, the SASP plays a key role in attracting immune cells and eliminating senescent populations. This was shown for instance in the liver where senescent stellate cells produce a suppressive SASP that activates M1-type macrophages and prevents transformation of epithelial cells in carcinoma [18]. Macrophages represent a major component of the intratumoral infiltrate. This population has a high plasticity and is divided in two M1 and M2 subtypes [19]. Whereas M2 macrophages are generally immunosuppressive, the M1 population is characterized by a strong inflammatory phenotype, this subtype plays an important role in the elimination of cancer cells and appears to be activated by the SASP. Additional studies showed that during hepatocarcinoma development, the reactivation of p53 leads to senescence induction, resulting in a complete regression of the disease. This was related to an inflammatory reaction which induces macrophages and NK cells infiltration, leading to the elimination of malignant cells [20].

Altogether, these studies and several others have demonstrated using in vitro or in vivo models that senescence is activated at the early steps of neoplasia to prevent carcinogenesis. This tumor suppressive mechanism relies on DNA damage, on a constant compaction of proliferative genes and on the recruitment of immune cells through the production of the SASP.

Chemotherapy-induced senescence can be incomplete

Besides oncogene activation and telomere attrition, senescence is also induced in response to chemotherapy (Chemotherapy-Induced Senescence or CIS). When used at relevant concentrations, most genotoxic treatments will induce a senescence arrest in epithelial cells [21,22]. Therefore, CIS, like apoptosis, was initially seen as a favorable outcome of chemotherapy. However, specific populations of cancer cells can escape genotoxic treatments and induce disease relapse. One essential question is therefore to understand how cells can escape a definitive proliferative arrest. Recent results have suggested that this could be due to an incomplete CIS response.

By definition, tumor suppressive mechanisms have to be inactivated during the successive steps of cell transformation. It has long been known that apoptotic pathways are modified in malignant cells and that this is one the main causes of therapeutic failure [23]. As described above, several studies have shown that senescence has to be inhibited during cancer progression. Consequently, oncologists are faced with genotoxic treatments that might only activate an incomplete CIS program. It is therefore important to distinguish the definition of senescence in primary cells, where it leads to a definitive arrest, from its value in cancer cells where its effects are certainly more complex. It might be confusing that most CIS parameters can still be detected in treated malignant cells, but these criteria might not be always sufficient to conclude for a definitive proliferative arrest of cancer cell lines. We and others have demonstrated in this case that senescence is not always definitive and that persistent cells can escape senescence.

The first explanation is certainly related to the common inactivation of p16 since this protein is necessary to maintain senescence [24]. For this reason, CIS induction in cancer cell lines will often rely on the well-described inhibitory effects of CDKN1A on cell cycle progression. It should be noted that the upregulation of this protein also leads to apoptosis inhibition. It is well known that the cell cycle inhibitor is a prosurvival factor, inducing caspase 3 inhibition, the blockade of cytochrome C release or the inactivation of stress kinases [25]. p21 inhibition is often necessary to activate a full cell death pathway and for instance, Puma-mediated apoptosis is easier to detect in its absence [26]. These inhibitory effects certainly explain why senescent cells are considered to be resistant to apoptotic pathways. It is tempting to describe CIS as an inhibitory mechanism of apoptosis, at least in cancer cells treated with chemotherapy. This can raise doubt about the value of this suppression following chemotherapy treatment [27]. Illustrating the choice between the two suppressive pathways, we have recently shown that colorectal cancer cell lines preferentially enter senescence in response to chemotherapy. However, when this pathway was inactivated, the same treatment induced apoptosis and this allowed a more efficient response (see below [28],).

Besides p16 dowregulation, the maintenance of senescence also relies on the stability of epigenetic modifications and on histone turnover. Recent studies have shown that the expression of replication-dependent histone decreases in senescent cells. However, these cells retain specific histones expressing an alternatively spliced exon 2 that prevents their degradation [29]. Non-canonical histones such as histone variant H3.3 are incorporated by the HIRA chaperone in the vicinity of transcriptional start sites, together with the H4K16 acetylated mark. Preventing histone incorporation allows senescence bypass and the emergence of cells that surprisingly express significant levels of p53 and p21. Thus, HIRA and histone turnover play a key role in the stability of senescence. It remains to be determined whether the maintenance of epigenetic marks is stable during CIS and how it can be affected by constant DNA damage. If this fidelity is modified during the successive rounds of chemotherapy, we can expect that the chromatin organization of senescent cells will ultimately be modified, thus generating clones that could bypass CIS.

This epigenetic stability also allows the long term inactivation of E2F targets since a constant trimethylation of H3K9 is necessary to maintain senescence [30]. Yu et al. have shown that the LSD1 and JMJD2C demethylases can remove this repressive mark to reactivate proliferative promoters. When co-expressed with Ras, these proteins allow senescence bypass and cell transformation, even if cells have already entered this suppressive arrest. Further implicating epigenetic modifications, we have also recently shown that the EZH2 methyltransferase is also involved in senescence escape [31]. How LSD1, JMJD2C and EZH2 activities will evolve during a long term arrest and constant DNA damage remain also to be determined.

Altogether, these results show that CIS can be incomplete in cancer cells, either as a consequence of the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes or if epigenetic marks are unstable. We do not really know how these chromatin modifications are modified by the different regimens of chemotherapy. This raises the possibility that the CIS epigenetic marks are dynamic in treated malignant cells and that this could lead to an unstable proliferative arrest.

It will also be interesting to determine if CIS has the same stability in solid or liquid tumors. Often investigated in fibroblasts or epithelial cancer cells, senescence has also a key importance in lymphomas [32]. This pathway certainly relies on DNA damage and on p53-p21 and p16-Rb in both tumors, but differences can be speculated. For instance, it could be interesting to determine if CIS signaling and its stability vary according to the leukemia differentiation stages. We can speculate that the composition of the SASP varies according to different malignant hematopoietic precursors. These liquid tumors are often driven by oncogenic fusion proteins such as BCR-ABL, Flt3-ITD or mixed-lineage leukemia proteins (MLL) which are not present in solid tumors. MLL translocations often result in aberrant methylation profiles that could affect the senescence epigenetic profile. Finally, one important difference is certainly the presence of the extracellular matrix. Following CIS escape, the spreading of solid tumors depends on the presence of metalloproteases which might not play such an important role in leukemia cells. In addition, immune cells might have a different accessibility to senescent cells located within this matrix as compared to senescent, liquid tumors which might express more accessible recognition markers. Further experiments will therefore be necessary to determine if liquid and solid tumors have the same ability to escape CIS.

Senescence: an heterogeneous response that can have tumorigenic properties

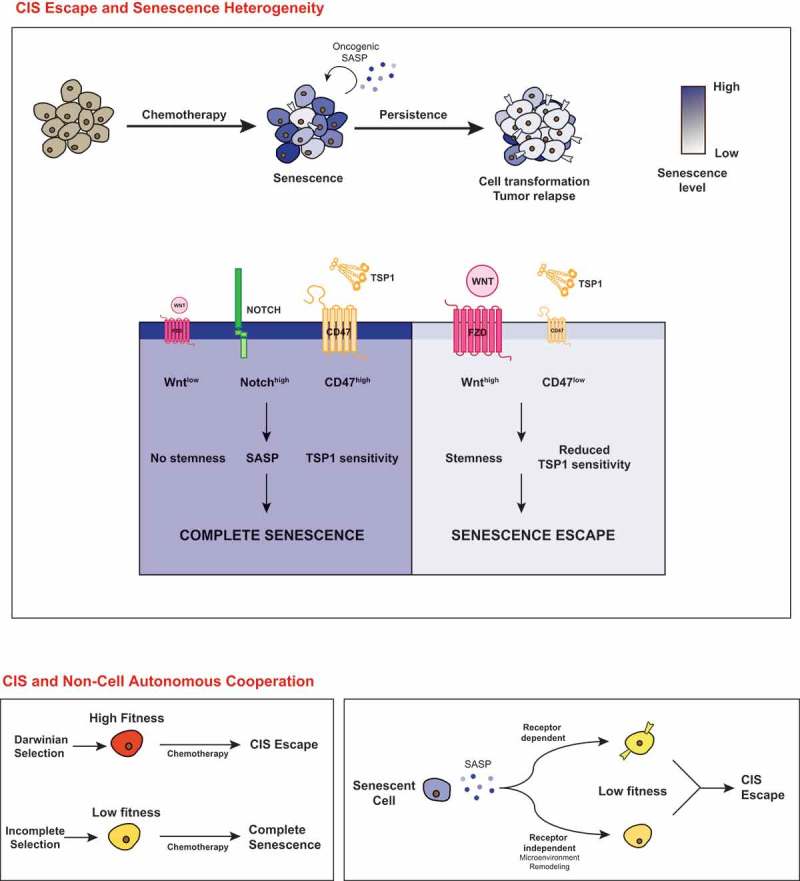

Depending on the background of responding clones, the CIS response in cancer cells is therefore probably heterogeneous. Some populations will enter a complete senescence state whereas other cells will express most markers of proliferative arrest but restart proliferation. If specific populations are able to escape CIS, one important question is to determine whether senescent cells provide a survival niche to generate more aggressive cells and whether emergent populations are more transformed than their parental counterparts.

Indeed, several studies have reported that these arrested cells have deleterious activities. Co-injecting senescent populations with epithelial cancer cells increases EMT, migration and tumor growth in vivo [33]. We have reported that colorectal cancer cells that bypass Ras-mediated senescence acquire more mesenchymal characteristics and enhanced migration capacities [34]. Enhanced cell transformation has also been described in primary keratinocytes that escape replicative senescence [35,36]. Specific populations of p21-expressing cells can also escape this suppressive arrest to become more transformed and proliferate despite a significant amount of genetic instability [37]. These detrimental effects are often related to the inflammatory secretome produced by senescent cells as the SASP can induce migration, cell dedifferentiation and EMT [38]. p53 inactivation significantly amplifies the secretion of these inflammatory cytokines, suggesting that this secretome plays an important role in cancer progression. Targeting the SASP prevents the deleterious activity of senescent cells without affecting the proliferative arrest [39]. It should be noted that some studies have reported a dynamic function of the SASP. In a mouse model of prostate cancer, PTEN downregulation leads to senescence but also to the concomitant production of an immunosuppressive SASP which allows cancer progression. This is the result of an abnormal activity of the JAK-STAT pathway which can favor senescence escape as we previously showed [40,41]. Inactivating JAK signaling restores a immune surveillance which prevents tumor progression. This is a clear example where the outcome of senescence could rely on tumor heterogeneity. Depending on the status of the JAK-STAT pathway in individual clones, senescence could exert opposite functions, either suppressive or oncogenic. Since STAT proteins are activated by chemotherapy [42–44], the heterogeneity of the CIS response could rely on the presence of clones expressing specific phosphorylated forms of STAT proteins.

The hypothesis that STAT transcription factors could be involved in CIS heterogeneity is also illustrated by their function in the cGAS-STING response. This DNA sensing pathway can induce apoptosis through p53 activation and the up-regulation of proapoptotic proteins such as Noxa or Puma [45]. However and as stated above, the cGAS-STING pathway is also necessary to maintain senescence through the activation of the SASP. The choice between the two suppressive mechanisms seems to depend on the intensity of the STING response [46]. Upon STING activation, the NF-kB and IRF3 transcription factors upregulate several cytokines and chemokines which most of the time can induce STAT pathways in neighboring cells. As stated above, these proteins play a key role in chemotherapy escape and for this reason we can speculate that a resistance signal is transferred from cell to cell in response to the cGAS-STING pathway. A clear example comes from several studies describing the role of IFN in chemotherapy escape. Initial results have shown that STAT1 is over expressed in radioresistant cells [47] and that a specific signature associated with the IFN-signaling pathway predicts the efficacy of adjuvent treatment in early breast cancer (IFN-related DNA damage resistance signature or IRDS [48],). Importantly, IFN is one of the key member of the SASP, its expression is induced by IRF3 and this cytokine then activates the STAT1 and STAT2 transcription factors in neighboring cells. Thus, it appears that the cGAS-STING pathway can indirectly transmit a resistance signal through the indirect activation of STAT1/2 in the microenvironment (Figure 1). It is not known if the IRDS signature correlates with the SASP but it will be interesting to determine if the STAT1 pathway is indeed activated in neighboring cells as a consequence of CIS induction. Investigating this outcome can be challenging since senescent cells often produce IL-6, a well-known activator of STAT3 and of the prosurvival members of the bcl-2 family. It is therefore tempting to speculate that both STAT1 and STAT3 are active in cells which are adjacent to senescent populations. This could lead to a strong resistance phenotype driven by the IRDS and Bcl-2 pathways. However, it should not be concluded that STAT1 and STAT3 always cooperate since these transcription factors also play opposite roles in anti-tumor immunity. The STAT1 pathway is known to activate various immune populations such as NK or CD8 T cells which are known to eliminate senescent cells [49]. On the opposite, STAT3 is well known to restrain the antitumor activity of immune cells and as a consequence this protein might prevent the removal of senescent cells. Altogether, these studies illustrate the crucial role of the STAT pathway in the transmission of senescence and chemotherapy resistance but they also describe a complex situation that needs to be investigated to reconcile intra and extracellular functions.

Figure 1.

A paracrine activation of STAT1 pathway by cGAS-STING and IFN induces CIS resistance in neighboring cells ?

In senescent cells, cytoplasmic chromatin fragments activate the cGAS-STING pathway which results in upregulation of NFkB and IRF3 and the production of IFN. This is expected to induce the activation of the STAT1 pathway in neighboring cells which has been associated with chemotherapy resistance.

Several studies have also reported that senescent cells play a key role in CIS resistance and disease relapse. Clear evidence showing a negative impact of CIS on survival came from experiments on mice developing mammary tumors under the control of the Wnt pathway [50]. The activation of p53 following doxorubicin treatment induced cell cycle arrest and senescence. However, this also activated the production of an oncogenic secretome which allowed tumor progression. In contrast, mammary tumors expressing a mutated form of p53 did not enter senescence, but instead progressed to mitosis and activated cell death programs in response to mitotic catastrophy. As a result, tumors expressing mutated forms of p53 exhibited a superior response to treatment.

Recent results extended these observations, describing that CIS provides an oncogenic niche in vivo. Demaria et al. showed in normal mice that chemotherapy treatment induces senescence in normal tissues but most importantly that this favors the growth and metastasis of xenografted tumor cells. The elimination of endogenous senescent cells through the use of a suicide gene under the control of the CDKN2A promoter significantly prevents metastatic spreading [51]. This deleterious effect of senescence in vivo has also been investigated using the Eμ-Myc model. Upon CIS induction, a significant stem cell signature was detected in lymphomas entering proliferative arrest. Following Suv39 or p53 inactivation, malignant cells that escape senescence restart proliferation with a higher tumor initiation potential [52]. This was explained by the inactivation of GSK3ß and the abnormal upregulation of the Wnt pathway. Besides lymphoma, this effect was also observed in melanocytes, colon mucosa and breast epithelial cells. Previous results have already reported that senescent cells are necessary for dedifferentiation and reprogramming in vivo [53]. It remains to be determined if all arrested cells express a stem-cell signature, but this again suggests that CIS can be heterogeneous. Depending on Wnt activation during successive chemotherapies, subpopulations of senescent cells might express this pathway, be reprogrammed into renewing stem cells and then produce emergent populations with enhanced oncogenic activity.

Besides these investigations in mice, we and other have shown in in vitro studies and in human cancer cells that the presence of senescent cells plays an important role in chemotherapy resistance. Investigating the response to first line genotoxic treatments, we found that subpopulations of breast or colorectal cells escape CIS to become more transformed and invasive [54]. Emergent cells relied on cdk4 and EZH2 activation to proliferate [31] and on the Akt-Mcl-1 pathway to survive [28]. We also described that the heterogeneous populations generated during CIS resist anoikis and that senescent cells increased metastatic spreading in the lung [55]. As stated above, inducing senescence bypass leads to the activation of apoptosis and significantly prevents the emergence of more transformed cells [28]. We have proposed that cell death might be a superior mechanism to treat advanced cancer cells since specific subpopulations use CIS as an adaptive pathway.

Most of the time, senescence is detected in studies using cancer cell lines with all the necessary markers indicative of this proliferative arrest, such as ß-galactosidase staining, cell cycle inhibitor expression, DNA damage, SAHF and DNA-SCARS foci or PML nuclear bodies. However it is always difficult to determine if the emergent populations are really entering a complete senescence to finally escape or whether they adapt before the complete inhibition of proliferative genes. As stated above, a bypass can result for example from low p16 levels. A true escape can be due to a long-term instability of epigenetic marks. Recent results have also shown that PTEN-deletion in melanocytes allows OIS escape, even if senescence was induced beforehand [56]. Further complexity is added by the fact that immune cells are generally not present in the in vitro experimental models. This makes it difficult to conclude that CIS is an incomplete program. However, we believe that these observations should not be viewed as experimental artifacts. These conditions do not represent the case of primary cells but certainly concern most of the advanced tumors that oncologists have to face.

A senescent ecosystem to adapt to chemotherapy

We do not really know how senescent cells will evolve under the pressure of constant genotoxic treatments and the consequent genetic instability. We can speculate that the successive rounds of CIS will induce the accumulation of senescent cells that could maintain a SASP-mediated survival niche and ultimately induce disease relapse. When feasible, this means that the detection of senescent cells during the course of adjuvant treatments should not always be viewed as a beneficial effect. The growth arrest detected by imaging techniques, often interpreted as a positive cytostatic response, will not always indicate a favorable response if it concerns senescent populations. To more precisely monitor chemotherapy responses, we have discussed elsewhere that a proteomic analysis of the circulating SASP could improve the sensitivity of medical imaging [57].

This SASP-mediated survival niche can favor senescence escape of premalignant clones as stated above but it can also allow the survival of adjacent clones with a lower fitness. This non-cell autonomous cooperation between heterogeneous cancer cells – which could include senescent populations – has been reported recently [58]. The classical, Darwinian, model of carcinogenesis states that tumor progression results from the successive dysregulation of tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes, all occurring within one cancer clone. This results in the inactivation of cell death pathways and the concomitant activation of cell cycle progression. As stated above, this has led to the conclusion that malignant cells are by definition resistant to chemotherapy. Translated into clinical practice, this means that tumor cells are addicted to specific oncogenes that block suppression and that these proteins should be identified and then considered as essential targets. The best confirmation of this theory is the success of BCR-ABL inactivation in chronic myeloid leukemia.

However, recent studies indicate that tumor progression also relies on the cooperation between different malignant cells. Single-cell analyses have described a significant genetic diversity among tumor sub-clones. Different populations coexist within tumors, raising the possibility that their transforming capacities could be different and that some clones need to cooperate to survive [58]. It has long been known that tumor progression is driven by a strong cooperation with the microenvironment. For instance, endothelial cells or cancer-associated fibroblasts provide essential signals that allow tumor progression. However, recent studies add complexity to the cancer ecosystem by showing that malignant clones bearing different mutations can also cooperate to enhance tumor growth. In Drosophila, Rasv12-expressing cells rely on adjacent populations, and tumor growth occurs only when these neighboring cells lose the scribbled tumor suppressor and propagate JNK activity to Rasv12-expressing clones [59]. In breast cancer cells, Marusyk et al. reported that tumor growth relies on a specific subpopulation that expresses IL-11. This IL-11-expressing clone was the main driver of a polyclonal population which grew inefficiently in its absence. Further illustrating this non-cell autonomous cooperation, metastatic spreading occurs only if polyclonal tumors contain IL-11 and FIGF-expressing subpopulations [60]. Together with other studies [61], these results lead to the important conclusion that clones with different fitness cooperate to induce tumor progression and that secreted factors play a key role in these interactions. In this condition, a complete dysregulation of tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes might not always be necessary. From a clinical point of view, this non-cell autonomous cooperation add significant complexity to the notion of oncogene addiction and to the design of targeted therapies.

Allowing the survival of clones with insufficient fitness may be a key hallmark of the role of senescent cells during CIS. It is clear in certain experimental models that the SASP induces EMT and dedifferentiation, characteristics which are well known to induce chemotherapy resistance. It is striking to note that some components of this secretome such as VEGF, metalloproteases or IL-6 are known to play a key role in the various stages of carcinogenesis. Therefore, it will be interesting to test the hypothesis that some senescent subpopulations provide less fit clones with essential characteristics of drug resistance that they had not acquired before. For instance, through IL-6 production, senescent cells might activate STAT3 in neighboring clones, leading to Bcl-xL or Mcl-1 upregulation and to the survival of clones that would otherwise die in response to treatment. Specific senescent subpopulations might also produce angiogenic factors or metalloproteases that the adjacent tumor clones are not able to secrete and this could allow CIS escape and metastatic spreading. Using colorectal cells, we have shown that senescent cells provide a survival niche that relies on Mcl-1 expression, allowing dividing clones to resist anoikis [54].

If this hypothesis is correct, the incomplete CIS of advanced cancer cells might be a necessary step in the resistance of polyclonal populations presenting an insufficient fitness. Further studies will be important to analyze the links between senescence and non-cell autonomous cooperations in more heterogeneous systems such as patient-derived organoids. As stated above, this will certainly add complexity to the rational of targeted therapies.

CIS heterogeneity: different receptors for different senescent cells?

If CIS generates heterogeneous senescent cells and non-cell autonomous cooperations, it will be important to characterize these specific subpopulations by their cell-surface receptors. This will help to identify the different clones that either enter a complete senescence or use an incomplete suppression as an adaptive pathway. This should be also useful to characterize the cooperations between senescent cells and their neighboring clones. It is obvious that these cooperations will rely on the expression of SASP receptors on the target cells. We can speculate that this cell surface expression will vary during the successive rounds of chemotherapy so that less fit clones might not always be able to take advantage of the senescent populations. However, the pressure of genotoxic treatment might lead to the selection of specific clones that express the necessary receptors to benefit from the inflammatory environment. FACS analysis could analyze the dynamics of these populations, in experimental models but most importantly in tumor samples and if feasible in biopsies (and body fluids or circulating tumor cells), during the course of neo-adjuvant treatment. This should help to monitor CIS heterogeneity and to predict disease relapse.

Indeed, recent results suggest that senescent cells can be identified by cell-surface receptors which could define subpopulations with a specific behavior. Using a proteomic screen of cell surface proteins, Hoare et al. recently described that the expression of Notch1 is upregulated in primary cells entering Ras-mediated senescence [62]. Importantly, this receptor defines a unique phenotype of arrested cells as its signaling is associated with a specific SASP composition. The expression of inflammatory cytokines is reduced in Notch-expressing cells which rather produce a significant amount of the TGF-ß family of ligands. As a result, these cells transmit a proliferative arrest to neighboring cells, either by their secretome or through lateral contacts. Notch1 downregulation is then necessary to allow the production of an inflammatory SASP that finally activate an immune response. This regulation was described in fibroblasts and confirmed in vivo in pancreatic and liver cells, suggesting that this is a general mechanism. This elegant study clearly suggests that the presence or absence of Notch-1 expressing cells could affect the outcome of the chemotherapy response. It will be interesting to determine whether the expression of this protein or of the Jagged and Delta-like ligands varies during CIS. The Notch-JAG pathway might define specific subpopulations of arrested cells that could influence the survival of neighboring clones, the generation of emergent cells and as a consequence the behavior of a polyclonal population during CIS.

Kim et al., also used proteomic experiments to identify membrane receptors expressed in senescent cells. They described that SCAMP4 and DPP4 are upregulated at the cell surface of human fibroblasts entering senescence [63,64]. Unfortunately, these proteins are not completely specific of arrested cells and for instance DPP4 is also known as a protease that regulates glucose homeostasis. Interestingly, flow cytometry was used to detect DPP4-expressing cells in the blood of young and old individuals. This approach successfully identified senescent cells in circulating mononuclear cells, illustrating the feasibility of detecting specific subpopulations of arrested cells within a complex population. This study also shows that ADCC assays and NK cells can be used to target senescent cells expressing a specific antigen. Using an anti-DPP4 antibody, it was shown that these immune cells essentially kill senescent populations and not their proliferative counterparts. Thus, it will be interesting to determine whether DPP4 expression identifies deleterious subpopulations of senescent cells during CIS and whether its targeting could reduce any non-cell autonomous cooperations provided by these clones.

Our recent results suggest that the CD47 receptor might also be useful to identify specific subpopulations of senescent cells [55]. Using breast or colorectal cancer cell lines or primary lung fibroblasts, we have observed that cells that escape CIS have a reduced expression of CD47 as a result of Myc-mediated repression. In contrast, the population that enters a complete arrest remains CD47high. We also identified TSP1 as a suppressive member of the SASP. Secreted by the arrested cells, this protein maintains senescence and prevents the emergence of persistent clones. Since CD47 is one of the TSP1 receptors, CD47low cells have probably a reduced sensitivity to this inhibitory effect. Previous studies have already described a link between the CD47-TSP1 pathway and senescence [65] or irradiation [66]. In addition, it has also been previously reported that CD47 is expressed in cancer initiating cells [67] and that its targeting inactivates CD44highCD24low cancer stem cells. Thus, CD47 plays an important role in response to genotoxic treatments and further experiments are needed to understand how this pathway affects CIS signaling. As stated above, it actually difficult to conclude that emergent cells are entering a true senescent phenotype to finally generate CD47low cells. A reduced expression of the receptor might also identify a subpopulation expressing a defective CIS pathway. It will therefore be interesting to determine if CD47low emergent cells are generated from the senescent CD47high population or if CD47low cells are selected under the pressure of TSP1 signaling.

As stated above for DPP4, specific receptors expressed at the surface of senescent cells are useful to characterize CIS heterogeneity but they can also be used to eliminate senescent cells. CD47 is well known to bind to the signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) expressed on macrophages to prevent their phagocytic activity. Anti-CD47 antibodies block this interaction and induce the phagocytosis of tumor cells [68]. Preclinical models have shown that the 5F9 antibody allows the specific elimination of malignant cells, both in vitro and in mice models. Recent phase 1 studies have confirmed this promising activity, showing that targeting CD47 in combination with retuximab induced a partial or complete response in 50% of patients suffering from refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma [69]. Partial responses were also observed in ovarian and fallopian tube carcinomas [70]. This confirms several preclinical studies and CD47 targeting will probably be an important way to restore anti-tumor immunity in patients [71]. However, in light of our results and others, further experiments are necessary to determine if this targeting will have the same activity when used in combination with chemotherapy. Since the CD47 pathway regulates DNA damage, CIS responses and cancer-initiating cells in different experimental models, its targeting in combination with genotoxic treatments should be tested with caution. If sequential treatments are used, it will be important to determine if CD47 expression evolves under the pressure of antibodies such as 5F9. This first line treatment might lead to the selection of CD47low cells that could then be difficult to eliminate by classical genotoxic chemotherapies.

Concluding remarks

Senescence is a tumor suppressive mechanism induced during the early steps of cell transformation. Like apoptosis, this pathway is inactivated during carcinogenesis and as a result, CIS will only activate an incomplete senescence signaling in advanced cancer cells. It is therefore actually difficult to define a unique state of senescence. Depending on their genetic and epigenetic modifications, some clones will effectively enter a definitive proliferative arrest but others will restart proliferation and become more aggressive. Through non-cell autonomous interactions, this might also allow the adaptation of tumor clones presenting a lower fitness that would otherwise die in response to chemotherapy (Figure 2). In these conditions, CIS can therefore be considered as an adaptive response to the treatment and its consequences are probably more complex than what was expected from studies in primary cells. Further experiments are therefore needed to characterize CIS heterogeneity and identify the specific subpopulations that use this pathway as an adaptive mechanism. Delineating how an incomplete CIS could be implicated in tumor resistance and which clones will induce tumor relapse is an essential goal of future chemotherapy.

Figure 2.

Chemotherapy-induced senescence is an heterogeneous response in cancer cells.

In response to chemotherapy, senescence normally induces a definitive proliferative arrest. As a consequence of cell transformation, the CIS response can be incomplete, generating specific clones that restart proliferation and become more aggressive (top). CIS escape can be explained by the genetic and epigenetic modifications of transformed cells but also by non-cell autonomous interactions that allow the survival of cells with a lower fitness, either through a direct activation or through the modification of the microenvironment (bottom).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the Ligue Contre le Cancer (Comité du Maine et Loire).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Perez-Mancera PA, Young AR, Narita M.. Inside and out: the activities of senescence in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lee S, Schmitt CA. The dynamic nature of senescence in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, et al. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Soengas MS, et al. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436:720–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Burd CE, Sorrentino JA, Clark KS, et al. Monitoring tumorigenesis and senescence in vivo with a p16(INK4a)-luciferase model. Cell. 2013;152:340–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sharpless NE, Bardeesy N, Lee KH, et al. Loss of p16Ink4a with retention of p19Arf predisposes mice to tumorigenesis. Nature. 2001;413:86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bennecke M, Kriegl L, Bajbouj M, et al. Ink4a/Arf and oncogene-induced senescence prevent tumor progression during alternative colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chen Z, Trotman LC, Shaffer D, et al. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;436:725–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Narita M, Nunez S, Heard E, et al. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell. 2003;113:703–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang R, Chen W, Adams PD. Molecular dissection of formation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2343–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rodier F, Munoz DP, Teachenor R, et al. DNA-SCARS: distinct nuclear structures that sustain damage-induced senescence growth arrest and inflammatory cytokine secretion. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:68–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ivanov A, Pawlikowski J, Manoharan I, et al. Lysosome-mediated processing of chromatin in senescence. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:129–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dou Z, Ghosh K, Vizioli MG, et al. Cytoplasmic chromatin triggers inflammation in senescence and cancer. Nature. 2017;550:402–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell. 2008;133:1019–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Herranz N, Gallage S, Mellone M, et al. mTOR regulates MAPKAPK2 translation to control the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1205–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Acosta JC, Banito A, Wuestefeld T, et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:978–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell. 2008;134:657–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, et al. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:399–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Roninson IB, Broude EV, Chang BD. If not apoptosis, then what? Treatment-induced senescence and mitotic catastrophe in tumor cells. Drug Resist Updat. 2001;4:303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Roninson IB. Tumor cell senescence in cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2705–2715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Leverson JD, Sampath D, Souers AJ, et al. Found in translation: how preclinical research is guiding the clinical development of the BCL2-selective inhibitor venetoclax. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:1376–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Beausejour CM, Krtolica A, Galimi F, et al. Reversal of human cellular senescence: roles of the p53 and p16 pathways. Embo J. 2003;22:4212–4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Abbas T, Dutta A. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:400–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yu J, Wang Z, Kinzler KW, et al. PUMA mediates the apoptotic response to p53 in colorectal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1931–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Childs BG, Baker DJ, Kirkland JL, et al. Senescence and apoptosis: dueling or complementary cell fates? EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1139–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vetillard A, Jonchere B, Moreau M, et al. Akt inhibition improves irinotecan treatment and prevents cell emergence by switching the senescence response to apoptosis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:43342–43362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rai TS, Cole JJ, Nelson DM, et al. HIRA orchestrates a dynamic chromatin landscape in senescence and is required for suppression of neoplasia. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2712–2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yu Y, Schleich K, Yue B, et al. Targeting the senescence-overriding cooperative activity of structurally unrelated H3K9 demethylases in Melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Le Duff M, Gouju J, Jonchere B, et al. Regulation of senescence escape by the cdk4-EZH2-AP2M1 pathway in response to chemotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schmitt CA, Fridman JS, Yang M, et al. A senescence program controlled by p53 and p16INK4a contributes to the outcome of cancer therapy. Cell. 2002;109:335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Krtolica A, Parrinello S, Lockett S, et al. Senescent fibroblasts promote epithelial cell growth and tumorigenesis: a link between cancer and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12072–12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].de Carne Trecesson S, Guillemin Y, Belanger A, et al. Escape from p21-mediated oncogene-induced senescence leads to cell dedifferentiation and dependence on anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL and MCL1 proteins. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12825–12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gosselin K, Martien S, Pourtier A, et al. Senescence-associated oxidative DNA damage promotes the generation of neoplastic cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7917–7925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Deruy E, Nassour J, Martin N, et al. Level of macroautophagy drives senescent keratinocytes into cell death or neoplastic evasion. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Galanos P, Vougas K, Walter D, et al. Chronic p53-independent p21 expression causes genomic instability by deregulating replication licensing. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:777–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Rodier F, Coppe JP, Patil CK, et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:973–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Georgilis A, Klotz S, Hanley CJ, et al. PTBP1-mediated alternative splicing regulates the inflammatory secretome and the pro-tumorigenic effects of senescent cells. Cancer Cell. 2018;34(85–102):e109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Vigneron A, Roninson IB, Gamelin E, et al. Src inhibits adriamycin-induced senescence and G2 checkpoint arrest by blocking the induction of p21waf1. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8927–8935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Vigneron A, Gamelin E, Coqueret O. The EGFR-STAT3 oncogenic pathway up-regulates the Eme1 endonuclease to reduce DNA damage after topoisomerase I inhibition. Cancer Res. 2008;68:815–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Slupianek A, Schmutte C, Tombline G, et al. BCR/ABL regulates mammalian RecA homologs, resulting in drug resistance. Mol Cell. 2001;8:795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Thomas M, Finnegan CE, Rogers KM, et al. STAT1: a modulator of chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8357–8364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Courapied S, Sellier H, De Carne Trecesson S, et al. The cdk5 kinase regulates the STAT3 transcription factor to prevent DNA damage upon topoisomerase I inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26765–26778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Vanpouille-Box C, Demaria S, Formenti SC, et al. Cytosolic DNA sensing in organismal tumor control. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:361–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gulen MF, Koch U, Haag SM, et al. Signalling strength determines proapoptotic functions of STING. Nat Commun. 2017;8:427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Khodarev NN, Beckett M, Labay E, et al. STAT1 is overexpressed in tumors selected for radioresistance and confers protection from radiation in transduced sensitive cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1714–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Weichselbaum RR, Ishwaran H, Yoon T, et al. An interferon-related gene signature for DNA damage resistance is a predictive marker for chemotherapy and radiation for breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18490–18495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Jackson JG, Pant V, Li Q, et al. p53-mediated senescence impairs the apoptotic response to chemotherapy and clinical outcome in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:793–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Demaria M, O’Leary MN, Chang J, et al. Cellular senescence promotes adverse effects of chemotherapy and cancer relapse. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:165–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Milanovic M, Fan DNY, Belenki D, et al. Senescence-associated reprogramming promotes cancer stemness. Nature. 2018;553:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Mosteiro L, Pantoja C, Alcazar N, et al. Tissue damage and senescence provide critical signals for cellular reprogramming in vivo. Science. 2016 Nov 25;354(6315). pii: aaf4445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Jonchere B, Vetillard A, Toutain B, et al. Irinotecan treatment and senescence failure promote the emergence of more transformed and invasive cells that depend on anti-apoptotic Mcl-1. Oncotarget. 2015;6:409–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Guillon J, Petit C, Moreau M, et al. Regulation of senescence escape by TSP1 and CD47 following chemotherapy treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Vredeveld LC, Possik PA, Smit MA, et al. Abrogation of BRAFV600E-induced senescence by PI3K pathway activation contributes to melanomagenesis. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1055–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Petit C, Guillon J, Toutain B, et al. Proteomics approaches to define senescence heterogeneity and chemotherapy response. Proteomics. 2019;e1800447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Tabassum DP, Polyak K. Tumorigenesis: it takes a village. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wu M, Pastor-Pareja JC, Xu T. Interaction between Ras(V12) and scribbled clones induces tumour growth and invasion. Nature. 2010;463:545–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Marusyk A, Tabassum DP, Altrock PM, et al. Non-cell-autonomous driving of tumour growth supports sub-clonal heterogeneity. Nature. 2014;514:54–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Calbo J, van Montfort E, Proost N, et al. A functional role for tumor cell heterogeneity in a mouse model of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:244–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Hoare M, Ito Y, Kang TW, et al. NOTCH1 mediates a switch between two distinct secretomes during senescence. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:979–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kim KM, Noh JH, Bodogai M, et al. Identification of senescent cell surface targetable protein DPP4. Genes Dev. 2017;31:1529–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kim KM, Noh JH, Bodogai M, et al. SCAMP4 enhances the senescent cell secretome. Genes Dev. 2018;32:909–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Baek KH, Bhang D, Zaslavsky A, et al. Thrombospondin-1 mediates oncogenic Ras-induced senescence in premalignant lung tumors. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4375–4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Soto-Pantoja DR, Ridnour LA, Wink DA, et al. Blockade of CD47 increases survival of mice exposed to lethal total body irradiation. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kaur S, Elkahloun AG, Singh SP, et al. A function-blocking CD47 antibody suppresses stem cell and EGF signaling in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:10133–10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Veillette A, Chen J. SIRPalpha-CD47 Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Anticancer Therapy. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Advani R, Flinn I, Popplewell L, et al. CD47 blockade by Hu5F9-G4 and Rituximab in Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1711–1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Sikic BI, Lakhani N, Patnaik A, et al. First-in-human, first-in-class phase I Trial of the Anti-CD47 Antibody Hu5F9-G4 in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:946–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Veillette A, Tang Z. Signaling regulatory protein (SIRP)alpha-CD47 blockade joins the ranks of immune checkpoint inhibition. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1012–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]