Abstract

Chest wall chondrosarcoma is a rare malignant tumor of the bone. This study is aimed to identify the prognostic determinants of chest wall chondrosarcoma. We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to identify patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma from 1973 to 2015. Statistical analyses were performed using Kaplan–Meier method and Cox regression proportional hazards. A total of 779 patients were identified from the SEER database. The overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) rates of the entire group at 10 years were 66.2% and 77.2%, respectively. On multivariate Cox regression, age ≤40 years, localized tumor stage, low tumor grade, surgery, and no radiotherapy were significantly associated with improved both OS and CSS. This study may help clinicians to predict survival of patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma and to provide appropriate treatment recommendations.

Keywords: chondrosarcoma, prognosis, thoracic wall, treatment outcome

1. Introduction

Chondrosarcoma is the second most frequent primary bone sarcoma, characterized by neoplastic chondrogenesis.[1] It is the most frequently occurring malignant bone tumor in adults.[2] Chest wall chondrosarcoma is a rare malignant tumor of the bone.[3] Although some previous studies reported the prognosis of this population, they were small population-based studies.[4,5] As chondrosarcomas are relatively unresponsive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, surgery remains the mainstream treatment.[1] Some studies have reported that radiotherapy can provide chondrosarcoma patients with excellent local control and symptom relief, indicating its survival advantage in chondrosarcoma.[6–9] However, the role of radiotherapy in the prognosis of patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma has not been explored.

To obtain insight into chest wall chondrosarcoma, we carefully selected and analyzed all patients from 1973 to 2015, based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. This large-scale study firstly used the multivariable Cox regression model to evaluate the prognostic factors for patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient selection

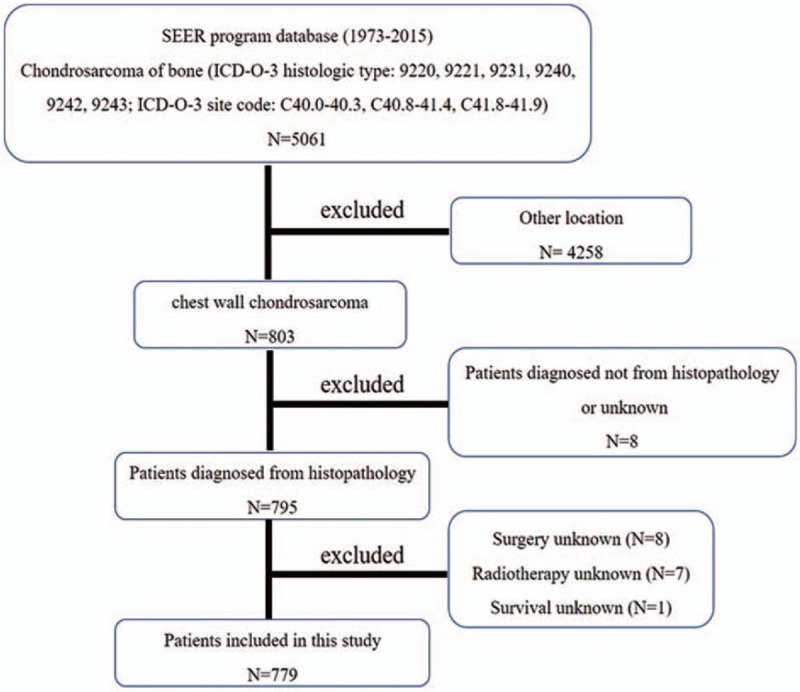

Patient data from 1973 to 2015 were obtained using the case-listing procedure from the SEER database. The SEER data are publicly available as the database contains no personal identification information. Thus, ethical approval was not necessary. First, we selected patients with a diagnosis of chondrosarcoma of bone (International Classification of Disease Oncology code: 9220 (chondrosarcoma, not otherwise specified), 9221 (juxtacortical chondrosarcoma), 9231 (myxoid chondrosarcoma), 9240 (mesenchymal chondrosarcoma), 9242 (clear cell chondrosarcoma), 9243 (dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma), and primary site code: C40.0–40.3, C40.8–41.4, and C41.8–41.9), using the case-listing process. Primary site was defined as chest wall and included rib, sternum, clavicle, and associated joints ribs. Only patients of chest wall chondrosarcoma were enrolled. All patient diagnoses were confirmed histologically, based either on biopsy results or the surgical specimen. Eight patients diagnosed only on the basis of the clinical presentation, or according to the radiography, or unknown were excluded. Fifteen patients with unknown therapy were excluded. One patient with unknown survival were also excluded. Figure 1 shows in detail the patient selection criteria. Demographic and clinical variables were extracted from the SEER database, including age, gender, tumor stage, tumor grade, tumor size, surgical treatment, radiation treatment, cause of death, and survival time. Surgery or radiation treatment for tumors in our study refers to treatment for local primary tumors. Tumor size was categorized as <5 cm, 5 to 10 cm, >10 cm or unknown. In addition, age at diagnosis was categorized as ≤40 and >40.

Figure 1.

The flow chart for selection of study population. SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results, ICD-O-3 = International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition.

2.2. Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2017 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS software (ver. 22.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to death from any cause. Cancer-specific survival (CSS) was regarded as the time from the date of diagnosis to the date of cancer-specific death. Univariate analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier estimates and the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression model was performed to determine the independent predictors of OS and CSS. The hazard ratio (HR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to show the effect of all known prognostic factors. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical characteristics of patients

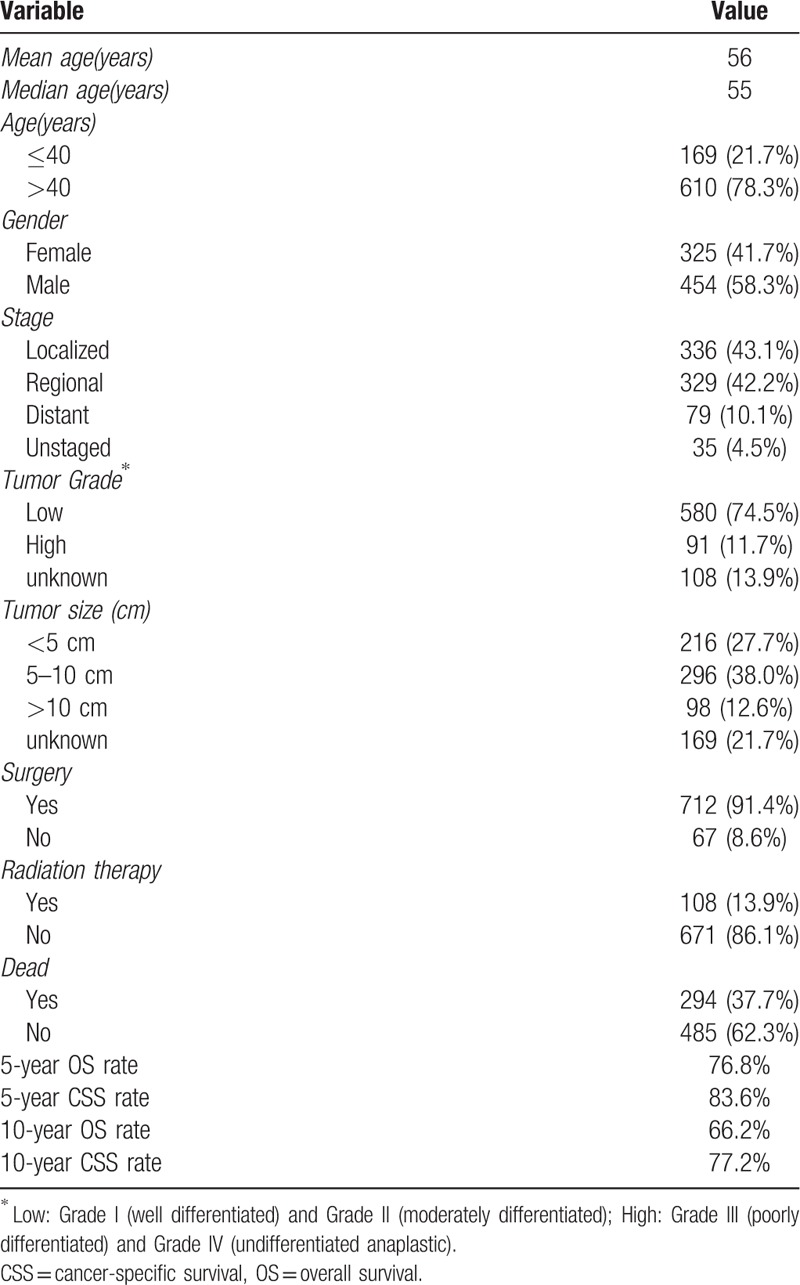

A total of 779 patients diagnosed with chest wall chondrosarcoma were eligible for our study. Demographically, 325 patients (41.7%) were female and 454 patients (58.3%) were male. The median age at presentation was 55 years, and most patients (78.3%) were aged over 40. Histologically, 74.5% of cases showed low-grade, and 11.7% showed high-grade. Among those patients, 665 of them (85.3%) had non-metastatic disease, while 79 patients (10.1%) developed metastasis at presentation. Tumor size >10 cm were more frequent in patients. Regarding the treatment, 91.4% of patients underwent surgical treatment and 13.9% of patients received radiotherapy. Ultimately, 294 patients (37.7%) died, of whom 121 died of this cancer. The OS and CSS rates of the entire group at 5 years were 76.8% and 83.6%, respectively. The 10-year OS and CSS rates of the entire group were 66.2% and 77.2%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 779 patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma.

3.2. Predictive factors of OS and CSS

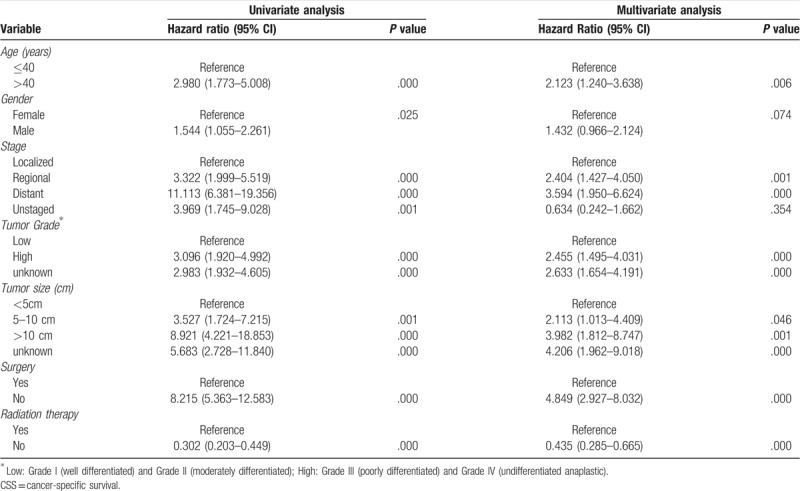

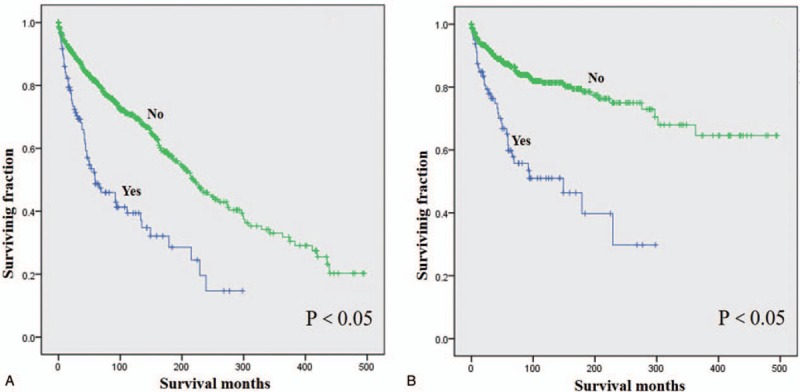

Prognostic factors for the OS and CSS are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. On univariate analysis of all patients, young age (≤40 years), no metastasis, low grade, small tumor size (≤10 cm), and surgical resection were significantly associated with better outcomes. Patients who received radiotherapy experienced significantly worse OS and CSS than those who did not (Fig. 2). Additionally, univariate analysis revealed that gender was significantly associated with CSS but not OS. On the multivariate analysis, age at presentation, tumor grade, tumor stage, surgery, and radiotherapy were identified as independent predictive factors of both OS and CSS, while gender lost significance for CSS.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for OS for 779 patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for CSS for 779 patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier method estimated OS (A) and CSS (B) in patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma stratified by radiation treatment.

4. Discussion

Chondrosarcoma is the most common primary malignant chest wall tumors.[4,10] Compared with other sarcomas in the chest wall, chondrosarcoma had a better survival.[11] Although chest wall chondrosarcoma is a rare malignancy, it has the potential for metastasis. Burt et al[3] reported that chest wall chondrosarcoma had the potential for distant metastasis and poor outcomes. Moreover, its clinical characteristics and appropriate treatments are not fully known. Previous studies have reported on the risk factors of recurrence or metastasis of chest wall chondrosarcoma.[5,12,13] Although some researchers retrospectively analyzed the prognostic factors of those patients, these studies were small heterogeneous cohorts.[4,5] To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore possible predictors of survival of such patients using the SEER database. Additionally, this study firstly reported the role of radiotherapy in survival in those patients.

In our series, there were 454 (58.3%) males and 325 (41.7%) females with a mean age of 56 years that is similar to that reported by other researchers.[4,5,12,14] Our study revealed that 79 (10.1%) patients experienced metastasis at diagnosis. However, Widhe et al[12] found that none of the patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma had metastasis at diagnosis. Meanwhile, they found 21 of the 106 patients (19.8%) developed metastasis during follow-up. McAfee et al[4] also reported that metastatic disease was diagnosed in 14 of 71 patients (19.7%) with chest wall chondrosarcoma after operation. Maybe those developing metastasis had micrometastasis before treatment. The 10-year OS rate for the 72 patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma treated at the Mayo Clinic from 1982 to 1909 was 53.4%.[4] The 10-year OS rate for the 106 patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma diagnosed in Sweden from 1980 to 2002 was 64%.[12] Similarly, the 10-year OS rate for our cohort was 66.2%. Among our series, the 5-year OS rate was 76.8% compared to 64% to 92% in the previous studies.[3,13,15] Therefore, the prognosis of patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma was more favorable than that of patients with other malignant chest wall tumors.[3,16]

On both univariate and multivariate analyses, age >40 years was significantly associated with worse OS and CSS. Marulli et al[5] revealed that age ≤55 years was an independent predictor of better survival for chest wall chondrosarcoma. However, McAfee et al[4] found that age did not have a significant effect on survival for chest wall chondrosarcoma. Although univariate survival analysis revealed male was associated with poorer outcomes, gender was not an independent predictor of either OS or CSS, which was similar to the result reported by Marulli et al.[5] Tumor grade, stage, and size are important prognostic variables of chondrosarcoma.[17–19] This study also revealed that these 3 variables were independently associated with OS and CSS. McAfee and Marulli also found that tumor size and tumor grade had significant effects on survival for chest wall chondrosarcoma. However, they did not explore the effect of tumor staging on the prognosis of patients. Patients with metastasis usually experience a poorer outcome than those with localized disease. And there is no standard treatment procedure for these patients.

Chondrosarcoma is 1 primary malignant bone tumor without an effective chemotherapy. Moreover, chondrosarcoma showed radiotherapy insensitivity. Thus, surgery is crucial for the outcome in chondrosarcoma including chest wall chondrosarcoma.[12,20,21] Our study also suggested that surgery can offer a favorable outcome for patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma. Some studies have reported that radiotherapy can provide chondrosarcoma patients with excellent local control and symptom relief, suggesting its potential benefits on survival of chondrosarcoma. Contrary to our hypothesis, patients who received radiotherapy had significantly inferior OS and CSS compared with those who did not. Abdel Rahman et al[10] reviewed 98 patients with malignant chest wall tumors and reported that absence of adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy was a univariate predictor rather than an independent predictor associated with better disease-free survival. Multi-center prospective studies are needed to confirm the role of radiotherapy in chest wall chondrosarcoma in the future. To improve the prognosis of the chest wall chondrosarcoma, elaborative staging, accurate grading, and proper treatment are of great importance.

This study has several limitations. First, data about local recurrence or distant metastasis during follow-up are not provided in the SEER database. Second, the roles of surgical procedure and chemotherapy, were not explored because those data are also not available in this database. Third, the specific location of chondrosarcoma such as the sternum or the rib is not known, which may be a risk factor. Additionally, the role of histological type was not explored because most of the cases (709/779, 91.0%) were 9220 (chondrosarcoma, not otherwise specified), which might be a risk factor.

5. Conclusion

This study included the largest number of patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma. The OS and CSS rates of the entire group at 10 years were 66.2% and 77.2%, respectively. Independent predictors of both OS and CSS were age at diagnosis, tumor stage, tumor grade, surgery, and radiotherapy. Our study is helpful for clinicians to better understand the characteristics and prognosis of chest wall chondrosarcoma and to provide suggestions for treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank the contribution of the SEER database.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Renbo Zhao.

Data curation: Hongliang Gao, Yuanxi Zhou, Zhan Wang.

Formal analysis: Hongliang Gao, Yuanxi Zhou, Zhan Wang.

Investigation: Hongliang Gao, Yuanxi Zhou, Zhan Wang, Renbo Zhao.

Methodology: Hongliang Gao, Yuanxi Zhou, Zhan Wang, Shengjun Qian.

Project administration: Hongliang Gao, Renbo Zhao, Shengjun Qian.

Resources: Renbo Zhao, Shengjun Qian.

Software: Hongliang Gao, Yuanxi Zhou.

Supervision: Renbo Zhao, Shengjun Qian.

Writing – original draft: Hongliang Gao.

Writing – review & editing: Renbo Zhao, Shengjun Qian.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, CSS = cancer-specific survival, HR = hazard ratio, OS = overall survival, SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

How to cite this article: Gao H, Zhou Y, Wang Z, Zhao R, Qian S. Clinical features and prognostic analysis of patients with chest wall chondrosarcoma. Medicine 2019;98:36(e17025).

HG, YZ, and ZW contributed equally to this work

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Rizzo M, Ghert MA, Harrelson JM, et al. Chondrosarcoma of bone: analysis of 108 cases and evaluation for predictors of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;224–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Whelan J, McTiernan A, Cooper N, et al. Incidence and survival of malignant bone sarcomas in England. Int J Cancer 2012;131:E508–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Burt M, Fulton M, Wessner-Dunlap S, et al. Primary bony and cartilaginous sarcomas of chest wall: results of therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;54:226–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].McAfee MK, Pairolero PC, Bergstralh EJ, et al. Chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: factors affecting survival. Ann Thorac Surg 1985;40:535–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Marulli G, Duranti L, Cardillo G, et al. Primary chest wall chondrosarcomas: results of surgical resection and analysis of prognostic factors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:e194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Krochak R, Harwood AR, Cummings BJ, et al. Results of radical radiation for chondrosarcoma of bone. Radiother Oncol 1983;1:109–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Goda JS, Ferguson PC, O'Sullivan B, et al. High-risk extracranial chondrosarcoma: long-term results of surgery and radiation therapy. Cancer 2011;117:2513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Andreou D, Ruppin S, Fehlberg S, et al. Survival and prognostic factors in chondrosarcoma: results in 115 patients with long-term follow-up. Acta Orthopaedica 2011;82:749–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kemmerer EJ, Gleeson E, Poli J, et al. Benefit of radiotherapy in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a propensity score weighted population-based analysis of the SEER database. Am J Clin Oncol 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Abdel Rahman ARM, Rahouma M, Gaafar R, et al. Contributing factors to the outcome of primary malignant chest wall tumors. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:5184–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kachroo P, Pak PS, Sandha HS, et al. Single-institution, multidisciplinary experience with surgical resection of primary chest wall sarcomas. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:552–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Widhe B, Bauer HC. Surgical treatment is decisive for outcome in chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: a population-based Scandinavian Sarcoma Group study of 106 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:610–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fong YC, Pairolero PC, Sim FH, et al. Chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: a retrospective clinical analysis. Clin Orthopaed Relat Res 2004;427:184–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Al-Refaie RE, Amer S, Ismail MF, et al. Chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: single-center experience. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2014;22:829–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Briccoli A, De Paolis M, Campanacci L, et al. Chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: a clinical analysis. Surgery today 2002;32:291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].King RM, Pairolero PC, Trastek VF, et al. Primary chest wall tumors: factors affecting survival. Ann Thorac Surg 1986;41:597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Song K, Song J, Shi X, et al. Development and validation of nomograms predicting overall and cancer-specific survival of spinal chondrosarcoma patients. Spine 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Giuffrida AY, Burgueno JE, Koniaris LG, et al. Chondrosarcoma in the United States (1973 to 2003): an analysis of 2890 cases from the SEER database. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:1063–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].2017;Strotman PK, Reif TJ, Kliethermes SA, et al. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma: a survival analysis of 159 cases from the SEER database (2001–2011). 116:252–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Song K, Shi X, Wang H, et al. Can a nomogram help to predict the overall and cancer-specific survival of patients with chondrosarcoma? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018;476:987–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bus MPA, Campanacci DA, Albergo JI, et al. Conventional Primary Central Chondrosarcoma of the Pelvis: Prognostic Factors and Outcome of Surgical Treatment in 162 Patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2018;100:316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]