TCF4 acts as a master regulator affecting expression of other genes, which may contribute to the development of schizophrenia.

Abstract

Applying tissue-specific deconvolution of transcriptional networks to identify their master regulators (MRs) in neuropsychiatric disorders has been largely unexplored. Here, using two schizophrenia (SCZ) case-control RNA-seq datasets, one on postmortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and another on cultured olfactory neuroepithelium, we deconvolved the transcriptional networks and identified TCF4 as a top candidate MR that may be dysregulated in SCZ. We validated TCF4 as a MR through enrichment analysis of TCF4-binding sites in induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)–derived neurons and in neuroblastoma cells. We further validated the predicted TCF4 targets by knocking down TCF4 in hiPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and glutamatergic neurons (Glut_Ns). The perturbed TCF4 gene network in NPCs was more enriched for pathways involved in neuronal activity and SCZ-associated risk genes, compared to Glut_Ns. Our results suggest that TCF4 may serve as a MR of a gene network dysregulated in SCZ at early stages of neurodevelopment.

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a debilitating neuropsychiatric disease that affects about 1% of adults (1, 2), with the heritability ranging from 73 to 83% in twin studies (3); however, its underlying genetic architecture remains incompletely understood (4). Recent genome-wide approaches have identified a plethora of common disease risk variants (5), rare copy-number variants (CNVs) of high penetrance (6, 7), and rare protein-altering mutations (8) that confer susceptibility to SCZ. Although exciting, the biology underlying these genetic findings remains poorly understood, prohibiting the development of targeted therapeutic strategies. A major challenge is the polygenic nature of SCZ, where risk alleles in many genes, as well as noncoding regions of the genome, across the full allelic frequency spectrum are involved and likely act in interacting networks (4). Therefore, given the large number of genes potentially involved, it has been challenging to identify which are the core set of genes that play major roles in the pathways or networks. It becomes even more challenging if the recent hypothesis of omnigenic model is true for SCZ, in which case, almost all of the genes expressed in a disease-relevant cell type may confer risk for the disease through widespread network interactions with a core set of genes (9). Thus, it is imperative to identify disease-relevant core gene networks, and possibly, the network master regulators (MRs), which are more likely to be targeted for therapeutic interventions (10, 11), if they exist. We define the term MR for transcription factors (TFs) and genes inflicting regulatory effects on their targets. We have collected a comprehensive set of 2198 genes curated from three sources (12–14), which are used in the following sections.

Transcriptional networks, as a harmonized orchestration of genomic and regulatory interactions, play a central role in mediating cellular processes through regulating gene expression. One of the most commonly used network-based modeling approaches of cellular processes are scale-free coexpression networks (15). However, coexpression networks and other similar networks are not comprehensive enough to fully recapitulate the entire underlying molecular interactions driving the disease phenotype (16). Despite the wide adoption of coexpression network analysis approaches, these methods have several limitations (17), such as the inability to infer or incorporate causal regulatory relationships, the difficulty to handle mammalian genome-wide networks with many genes, and the presence of high false-positive rates due to indirect connections. In contrast, information-theoretic deconvolution techniques (16) aim to infer causal relationships between TFs and their downstream targets and have been recently successfully applied in a wide range of complex diseases such as cancers (18) and neurodegenerative diseases (19).

Inferring disease-relevant transcriptional gene networks requires well-powered transcriptomic case-control datasets from disease-relevant tissues or cell types. For SCZ, although abnormal gene expression in multiple brain regions (20) and different types of neuronal cells (21) may be involved in disease pathogenesis, abnormalities in cellular and neurochemical functions of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) have been demonstrated in patients with SCZ (22). Furthermore, DLPFC controls high-level cognitive functions, many of which are disturbed in SCZ. The CommonMind Consortium (CMC) RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data on DLPFC, which includes 307 SCZ cases and 245 controls, is currently the largest genomic dataset on postmortem brain samples for neuropsychiatric disorders (23). The CMC study validates ~20% of SCZ loci having variants that can potentially contribute to the altered gene expression, where five of which involve only a single gene such as FURIN, TSNARE1, and CNTN4 (23). A gene coexpression analysis in the CMC study implicated a gene network relevant to SCZ but does not address the question of whether an MR potentially orchestrates the transcriptional architecture of SCZ. In the current study, using CMC RNA-seq data, we deconvolved the regulatory processes mediating SCZ to identify critical MRs and to infer their role in orchestrating cellular transcriptional networks. Using another set of independent SCZ case-control RNA-seq data on cultured neuronal cells derived from olfactory neuroepithelium (CNON) (24), we observed five MRs shared between both datasets. Among the top candidate MRs identified from both datasets, we selected TCF4, a leading SCZ risk gene from a genome-wide association study (GWAS) (5), for empirical validation of predicted network activity using human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)–derived neurons. A general overview of both the computational and experimental stages of this study is provided in Fig. 1. On the basis of the results, we identified TCF4 as an MR that likely contributes to SCZ susceptibility at the early stages of neurodevelopment.

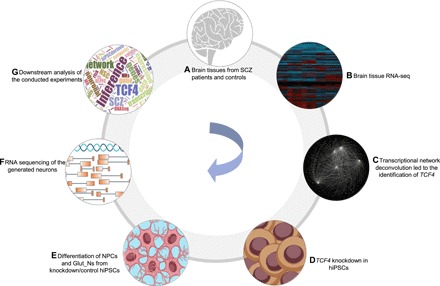

Fig. 1. An overview of the current study.

(A and B) Obtaining gene expression data generated from DLPFC (CMC data) and later CNON data as an independent validation. (C) Transcriptional network reconstruction based on the RNA-seq data using algorithm for reconstruction of accurate cellular networks (ARACNe) and identification of TCF4 as a disease-relevant MR. (D) Knockdown of TCF4 in hiPSCs derived from a patient with SCZ and two unaffected individuals. (E) Differentiation of hiPSC into neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and glutamatergic neurons (Glut_Ns). (F) RNA-seq of the generated neuronal cells with and without TCF4 knockdown. (G) Downstream inferences and analysis of the conducted experiments.

RESULTS

Deconvolution of transcriptional network of the CMC data uncovers MRs

The CMC transcriptomic study implicated 693 differentially expressed (DE) genes in SCZ postmortem brains (23). However, the magnitude of case-control expression differences was small, posing a challenge to inferring their biological relevance. We thus deconvolved the transcriptional regulatory networks to infer the MRs and their transcriptional targets (regulons), from which we constructed their corresponding subnetworks. To achieve this, we used Algorithm for Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks (ARACNe) to reconstruct cellular networks (see Materials and Methods) (17). This approach first identifies gene-gene coregulatory patterns by the information theoretic measure mutual information (MI), followed by network pruning through removing indirect relationships in which two genes are coregulated through one or more intermediate entities. This enabled us to observe network relationships that are more likely to represent direct transcriptional interactions (e.g., TF binding to a target gene) or posttranscriptional interactions (e.g., microRNA-mediated gene inhibition). We identified 1466 genes as hubs by computational analysis of the CMC RNA-seq data (table S1), where the corresponding subnetworks for these hub genes contain 24,548 transcriptional interactions (table S2).

Using the reconstructed network, we next performed a virtual protein activity analysis to investigate the activity of the identified hub genes by taking into account the expression patterns of their downstream regulons through a dedicated probabilistic algorithm called VIPER (Virtual Inference of Protein-activity by Enriched Regulon analysis) (18). This method exploits the regulator mode of action, the confidence of the regulator-target gene interactions, and the pleiotropic features of the target regulation. We fed the generated network into VIPER to evaluate whether any of the identified hub genes in the network has a significant regulatory role in the expression degrees of its downstream target genes. We then ranked the hub genes by VIPER-adjusted activity P values (representing the statistical significance of being an MR; see Materials and Methods). We further defined a short list of genes potentially regulating a large set of targets (n = 93). VIPER outputs a list of genes whose activity levels are highly correlated with the expression of their regulons in the input network. However, as recommended by the VIPER developers, many of these genes are not regulators of their corresponding targets in practice. Therefore, they recommended focusing on the highly active genes in the VIPER output, which are TFs or histone modification genes. As a result, among genes with highly significant VIPER P values, we only took the genes from the curated list of TFs as potential MRs. Moreover, as suggested by the VIPER developers, we set the activity P values at 0.005 to minimize the number of false-positive MRs and to avoid obtaining candidate MRs with very few numbers of regulons despite high-activity P values.

To reduce false-positive findings and to focus on MRs known to exert regulatory effects on their targets, we intersected the short list of potential MRs with our curated set of genes (fig. S1). This process resulted in five potential MRs: TCF4, NR1H2, HDAC9, ZNF436, and ZNF10. On the basis of previous studies (25), identification of the activated MRs in a disease state may be confounded when several of its regulons are all targets of a different transcriptional factor, that is, the “shadow effect” (25). Because of the highly pleiotropic nature of transcriptional regulations, we evaluated the shadow effects in the constructed networks. We should note that, during the process of network deconvolution, most of the potential coregulatory edges have been trimmed to preserve the scale-free topology of the network, so we expect to observe no shadow effects. As expected, no shadow connections were observed in this analysis, indicating a high confidence in the constructed transcriptional network to reflect a likely real regulatory connection between an MR and its targets.

Network deconvolution of CNON data independently identifies TCF4 as an MR

We next attempted a replication of the identified MRs in an independent RNA-seq dataset (with 23,920 transcripts) from CNON of 143 SCZ cases with 112 controls (24). The rationale is that if the TCF4 network identified in the CMC dataset is more of neuronal origin, then confirmation of the TCF4 MR in the CNON model would add supporting evidence for the predicted MR, given that olfactory cells are promising models in biological psychiatry and neuroscience (26). We acknowledge that the CNON culture likely contains non-neuronal cells such as epithelial cells. Because the CMC data are generated from postmortem brain tissues comprising both neuronal and non-neuronal cells, we first estimated the percentage of neuronal cells in postmortem brain DLPFC (used by CMC). On the basis of a recent study of cellular composition of the same brain region (DLPFC) by Lake et al. (27), in which 36,166 single cells were assayed for gene expression, we found that 26,064 cells (~72%) were neuronal cells, indicating that neuronal cells constitute a significant proportion of the brain cell types in postmortem DLPFC. Furthermore, of 101 TCF4 target genes predicted in CMC, 31 were found to have significantly higher expression in neuronal cells (enrichment P = 2.8 × 10−10 by Fisher’s exact test, fold enrichment = ~3.5), while the rest were all expressed in neuronal cells. We thus conclude that the constructed networks from the CMC dataset stem from neuronal cells, despite possible influence from the small fraction of non-neuronal cells.

Using setup criteria similar to those used on the CMC data, for CNON data, we observed 1836 TFs or expression regulatory nodes in the constructed network, including 34,757 predicted interactions (tables S3 and S4). To further analyze the activity of the identified hub genes, we ran VIPER on the constructed network and identified the top MRs. The five identified MRs in the CMC network (TCF4, NR1H2, HDAC9, ZNF436, and ZNF10) were observed to be MRs within the network created from CNON data. All of these five MRs were significant in both CMC and CNON data [false discovery rate (FDR) values are provided in table S11]. On the basis of the deconvolution analysis, these five MRs were predicted to regulate the expression of 101, 68, 36, 66, and 43 regulons combined, respectively (table S5). Among these genes, TCF4 is a well-established SCZ-associated risk factor identified by GWAS (5), which has been validated in several additional studies (28, 29). Rare variants in TCF4 have also been implicated in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome and intellectual disability (30). However, its regulatory mechanisms at a systems level are poorly understood. Although the other identified MR may also potentially contribute to SCZ pathogenesis, given the prior biological knowledge on TCF4, we have focused on TCF4 for additional analysis.

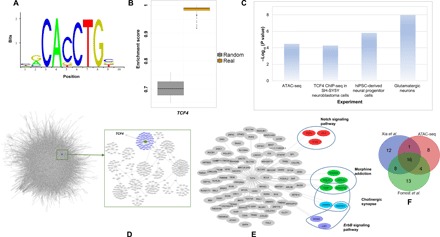

To further evaluate the connection between TCF4 dysregulation and SCZ, we conducted pathway enrichment analysis using WebGestalt (31). The predicted TCF4-associated regulons were enriched for several pathways such as Notch signaling pathway (FDR = 1 × 10−4) and long-term depression (FDR = 8 × 10−4). In addition, to check whether the promoter region of the predicted TCF4 targets is enriched for TCF4 binding motif sequence, we conducted TF binding enrichment analysis (TFBEA) using JASPAR (32). The TCF4 motif sequence is extracted from JASPAR and is used for binding enrichment analysis (Fig. 2A). We extracted the sequence of the target genes 2 kb upstream and 1 kb downstream of their transcription start sites (TSSs) and used a significance threshold of 0.80 to test the relative enrichment scores of its target genes. We found that the observed binding enrichment score is significantly higher than expected by chance (two-sided t test P = 2.2 × 10−16) based on a random list of genes outside the TCF4 subnetwork (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the predicted TCF4 regulons can be directly targeted by TCF4 binding events.

Fig. 2. Summary of TCF4 regulons in the CMC and CNON data.

(A) TCF4 motif from the JASPAR database used in the analysis. (B) TCF4 binding site enrichment scores (based on TCF4 motifs from the JASPAR database) among the TCF4 regulons compared to that of a set of random genes. (C) Enrichment P values of the TCF4 regulons, compared with several gene sets, including the predicted TCF4 sites from ATAC-seq, the differentially expressed genes from our TCF4 knockdown experiments, and the predicted TCF4 binding sites in neuroblastoma cells by ChIP-seq (P value obtained from Fisher’s exact test). (D) A schematic of the network created from CMC data as well as the TCF4 targets. (E) TCF4 targets from CMC and CNON data combined with some of the associated pathways. (F) List of overlapping predicted TCF4 targets with an ATAC-seq on hiPSC–Glut_Ns and two ChIP-seq datasets.

Predicted TCF4 regulons are significantly enriched for TCF4 targets from ATAC-seq and ChIP-seq experiments

Our observed enrichments of TF binding motif of TCF4 in its regulons were purely a DNA sequence–based prediction, so we next tested whether TCF4 can physically interact with its regulons. To address this question, we first identified the target genes of TCF4 by examining the empirical TF occupancy (i.e., TF binding footprints) inferred by the Protein Interaction Quantification (PIQ) tool (33, 34) from our previous assay for transposase-accessible chromatin (ATAC-seq) data in hiPSC and hiPSC-derived glutamatergic neurons (Glut_Ns) (34, 35). Twenty-nine target genes of 101 regulons of TCF4 were found to be bound by TCF4 in ATAC-seq from Glut_Ns (total TCF4 targets in ATAC-seq data in Glut_Ns = 3276) (enrichment P = 3.3 × 10−5 by Fisher’s exact test, fold enrichment = ~1.93), whereas only one TCF4 target was bound by TCF4 in hiPSCs (total TCF4 targets in ATAC-seq data in hiPSCs = 172) (no enrichment P = 0.417 by Fisher’s exact test).

Furthermore, with the list of empirically determined TCF4 targets in a recent TCF4 chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) study on human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells (36) (a total of 10,604 peaks for 5436 unique candidate target genes), we observed an overlap of 41 TCF4 targets between TCF4 ChIP-seq data and our inferred TCF4 regulons, representing a significant enrichment (P = 5.28 × 10−5 by Fisher’s exact test, fold change = ~1.65). Recently, Xia et al. (37) have examined the genes regulated by TCF4 in neuron-derived SH-SY5Y cells using ChIP-seq. They have reported a total of 11,322 peaks for 6528 unique candidate target genes. We observed 37 genes overlapping with the TCF4-predicted target genes (n = 101, P = 3 × 10−3 by Fisher’s exact test, fold change = ~1.5). Together, both ATAC-seq and ChIP-seq analyses demonstrated that our list of predicted regulons is significantly enriched for TCF4 transcriptional regulatory targets, reflecting the differences in different cell types (Fig. 2C). To further probe these overlapping genes, we compiled the predicted targets of TCF4 with the above ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq datasets on Glut_Ns (Fig. 2F and table S10). We observed that a large fraction of TCF4 targets are shared between two or all of the compared datasets, which is a strong indication of the reliability of the inferred TCF4 targets during network construction.

Network perturbation by TCF4 knockdown in hiPSC-derived neurons supports TCF4 as an MR and a regulator of neurodevelopment

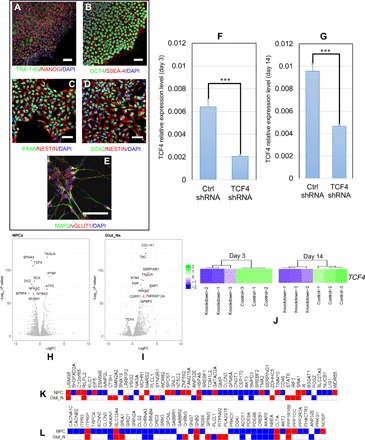

To further investigate the functional relevance of TCF4 dysregulation in SCZ, we examined how the predicted TCF4 transcriptional subnetwork changes with decreased TCF4 expression in hiPSC-derived neuronal cells. We acknowledge that similar experiments have been performed on the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line (36, 38), which is a cell type that may be less relevant to SCZ. We first derived relatively pure NPCs (NESTIN+/PAX6+/SOX2+) from hiPSCs (TRA-1-60+/SSEA4+/NANOG+/OCT4+) (Fig. 3, A to D), which were further differentiated into glutamatergic neurons (Glut_Ns) (VGLUT1+/MAP2+) (Fig. 3E). hiPSCs were captured from a patient with SCZ (see Materials and Methods). To capture possible differential effects of TCF4 on gene expression during different developmental stages, we carried out TCF4 knockdown by lentiviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA) in NPCs of day 3 after initiating neural differentiation (Fig. 3, C and D) and in the early stage of Glut_Ns of day 14 after initiating differentiation (Fig. 3E). We achieved significant TCF4 knockdown in both cell stages: TCF4 expression in the knockdown group was reduced to 32.2 and 48.6% of that in the control shRNA groups [as measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), P < 0.001; Fig. 3, F and G]. We also performed RNA-seq analysis on the same set of cells with three biological replicates at both time points in both cell types and found that the reduction of TCF4 transcript level was consistent with the qPCR results (Fig. 3J).

Fig. 3. TCF4 knockdown in hiPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and Glut_Ns (from a SCZ patient line).

(A) Representative immunofluorescence (IF)–staining images of hiPSCs. hiPSCs are stained positive for pluripotency markers TRA-1-60 (green) and NANOG (red). (B) Representative IF-staining images of hiPSCs. hiPSCs are stained positive for OCT4 (green) and SSEA-4 (red). (C) Representative IF-staining images of NPCs (3 days after plating cells): NPCs are stained positive for PAX6 (green) and NESTIN (red). (D) Representative IF-staining images of NPCs (3 days after plating cells): NPCs are stained positive for NESTIN (red) and SOX2 (green). (E) Representative image of day 14 neurons stained positive for MAP2 (green) and vGLUT1 (red). (F) TCF4 knockdown efficiency measured by qPCR in NPCs (3 days after plating). (G) TCF4 knockdown efficiency measured by qPCR in Glut_Ns (14 days after neuronal induction). (H) Volcano plot of DE genes in NPCs. (I) Volcano plot of DE genes in Glut_Ns. (J) TCF4 expression levels at days 3 and 14 in RNA-seq data (K) Overlap of the DE genes upon TCF4 knockdown with a list of GWAS-implicated SCZ risk genes (up- and down-regulated genes are shown in red and blue, respectively; white cells indicate that the gene is not DE). (L) Overlap of the DE genes upon TCF4 knockdown with a list of credible GWAS risk loci (up- and down-regulated genes are shown in red and blue, respectively; white cells indicate that the gene is not DE). Scale bars, 50 μm in all images. Cell nuclei are stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) (A to E), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is used as the endogenous control to normalize the TCF4 expression for qPCR. Error bars, mean ± SD (n = 4). ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test, two-tailed, heteroscedastic.

Transcriptomic analysis of the RNA-seq data of TCF4 knockdown revealed 4891 DE genes in the day 3 group (NPCs data; Fig. 3H), including 2330 up-regulated and 2561 down-regulated genes (FDR < 0.05) (see Materials and Methods). The day 14 group (Glut_Ns data; Fig. 3I) showed 3152 DE genes, of which 1862 were up-regulated and 1290 were down-regulated (FDR < 0.05) (table S7). To examine whether the gene network perturbed by TCF4 knockdown in hiPSC-derived neurons is concordant with the predicted TCF4 regulons, we compared the list of genes affected by TCF4 knockdown and the list of 101 TCF4 regulons from the CMC/CNON data. We found that 39 predicted TCF4 regulons showed altered expression by TCF4 knockdown in NPCs (enrichment P = 1.55 × 10−6 by Fisher’s exact test, fold change = ~1.75), while 33 predicted TCF4 regulons were dysregulated after TCF4 knockdown in Glut_Ns (enrichment P = 1.05 × 10−8 by Fisher’s exact test, fold change = ~2.28). This difference between the enrichment P values of the conducted experiments compared to the neuroblastoma cell line confirmed the importance of tissue-specific investigation of transcriptional regulation (although the set of regulons may be more conserved across tissues) and further supported the role of TCF4 as an MR in a transcriptional network (Fig. 2, D and E) relevant to neurodevelopment (Fig. 2E).

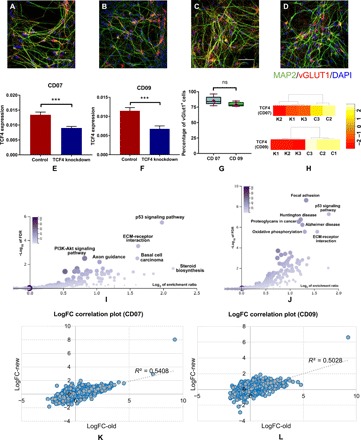

As our observed transcriptomic changes were from an SCZ patient line, we further carried out TCF4 knockdown in cells derived from hiPSC lines of two unaffected individuals (cell lines CD07 and CD09; Fig. 4, A to D) to account for variations due to individual genetic backgrounds. Because TCF4 regulons were initially found more enriched in the list of genes perturbed by TCF4 knockdown in Glut_Ns (Fig. 2C), we have focused on examining the robustness of our findings on Glut_Ns with three independent cultures for each condition. Using qPCR, we examined the knockdown efficiency in both cell lines (~40%) (Fig. 4, E and F). We also confirmed the relatively high homogeneity of the differentiated neurons (80 to 85%) (Fig. 4G). Further transcriptomic analysis from bulk RNA-seq data also confirmed the successful reduction in TCF4 expression in cell line CD09 (negative binomial test, FDR = 1.55 × 10−14), as well as cell line CD07 (FDR = 2.35 × 10−12) (Fig. 4H). During the quality assessment procedure, we removed one sequenced sample as an outlier from downstream analysis (fig. S10, see Materials and Methods). In total, we identified 2304 DE genes in CD09 and 1744 DE genes in CD07 (FDR < 0.05). Next, we examined the enrichment of TCF4 network regulons in the list of DE genes from both cell lines. We observed 22 predicted TCF4 regulons to be dysregulated after TCF4 knockdown in Glut_Ns of CD09 (enrichment P = 6.85 × 10−4 by Fisher’s exact test, fold enrichment = ~2.1) and 17 predicted TCF4 regulons in CD07 (enrichment P = 2 × 10−3 by Fisher’s exact test, fold enrichment = ~2). Moreover, we compared the log fold change of the genes in the two generated cell lines (CD07 and CD09) and compared them with the initial data on Glut_Ns (Fig. 4, K and L). To check the consistency of cellular responses to the TCF4 knockdown, we compared the log fold changes of the genes in the CD07 and CD09 lines with the initial SCZ Glut_Ns data. We observed a correlation coefficient of 0.54 and 0.50 for CD07 and CD09, respectively, between the log fold changes of gene expression (P = 10−15 and 10−14 for CD07 and CD09, respectively), which further supports our findings, implying that TCF4 knockdown had a consistent effect on the transcriptome change in the several cell lines used in our study. Together, these observations reconfirmed the role of TCF4 as an MR in the created regulatory networks across individuals.

Fig. 4. TCF4 knockdown in hiPSC-derived Glut_Ns in two independent cell lines CD07 and CD09 from unaffected control subjects.

(A and B) IF staining of hiPSC-derived Glut_Ns from the CD07 control line. (C and D) IF staining of hiPSC-derived Glut_Ns from the CD09 control line; MAP2, green; vGlut1, red; DAPI, blue. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E and F) Real-time qPCR (qRT-PCR) result of TCF4 expression level in two different lines, demonstrating knockdown efficiency; GAPDH is used as the endogenous control to normalize the TCF4 expression for qPCR; error bars, mean ± SD (n = 6 to 8); ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test, two-tailed, heteroscedastic. (G) Percentage of vGlut1-positive cells derived from two different hiPSC lines; cell counts were from five images in each line. (H) TCF4 expression levels in knockdown (K1, K2, and K3) and control samples (C1, C2, and C3) in the generated RNA-seq data on CD07 and CD09. (I) Pathway enrichment analysis results on the identified DE genes in CD07 (color legend indicates the number of overlapped DE genes with the corresponding pathway). (J) Pathway enrichment analysis results on the identified DE genes in CD09 (color legend indicates the number of overlapped DE genes with the corresponding pathway). (K) Correlation plot of the log fold changes (logFC) of the Glut_Ns from the SCZ cell line (“old”) and CD07. (L) Correlation plot of the log fold changes of the Glut_Ns from the SCZ cell line (“old”) and CD09. ns, not significant.

Although our deconvolution analysis identified 101 genes in the TCF4 subnetwork, we reasoned that it is likely part of a much larger transcriptional network that would contain neurobiological pathways relevant to SCZ. Previous studies in mice (39) and neuroblastoma cells (38) have demonstrated that TCF4 dysregulation affects a large number of genes and pathways; however, TCF4-related pathways have never been explored in human NPCs or Glut_Ns, a much stronger model for studying psychiatric disorders. To uncover the cellular pathways regulated by TCF4 in these cell types, we performed gene ontology (GO) and pathway analyses on the genes perturbed by TCF4 knockdown.

By using WebGestalt (31), we identified a number of shared gene pathways, including focal adhesion, axon guidance, mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, and apoptosis (table S6 and figs. S2 to S6). In table S6, we showed the altered pathways at both time points as a result of TCF4 knockdown and the detailed list of up- and down-regulated genes in each pathway. We found almost similar enrichment for “axon guidance” (FDR = 1.521 × 10−6 and fold enrichment = 1.77 in NPCs versus FDR = 5.941 × 10−5 and fold enrichment = 1.81 in Glut_Ns) while observing some unique pathways (long-term potentiation, neurotrophin signaling, and mTOR signaling) relevant to neuronal activity. An independent pathway analysis using MetaCore (see Materials and Methods and figs. S7 and S8) also showed consistent results. The top gene expression changes in NPCs converged on early neurodevelopmental processes such as axon guidance, neurogenesis, and attractive and repulsive receptors, which guide neuronal growth and axon targeting during development. In contrast, the most significant categories in Glut_Ns involved cell adhesion and cell-matrix interactions, suggesting that TCF4 regulates different subsets of genes during development. In parallel, the MetaCore analysis revealed that the up-regulated genes had distinct functions in NPCs and Glut_Ns, involving mRNA translation and cell-matrix interactions, respectively. However, down-regulated genes shared a number of categories, including axon guidance being the most significant pathway.

For both up-regulated and down-regulated genes by TCF4 knockdown, NPCs showed more enriched neuronal activity–related gene pathways than in Glut_Ns and with greater significance (tables S8 and S9). It is also noteworthy that most altered neuronal activity–related pathways were enriched in the down-regulated set of genes upon TCF4 knockdown. These results suggest that TCF4 gene targets act at the early stage of neurogenesis and may be more relevant to SCZ biology. We conducted a pathway enrichment analysis (Fig. 4, I and J) on our independently sequenced cell lines from unaffected individuals, which yielded very similar outcomes compared to the altered pathways upon TCF4 knockdown in the Glut_Ns in the SCZ cell line. These similarly altered pathways such as focal adhesion and p53 signaling pathway indicate that, despite cross-individual genetic variations, TCF4 plays a critical role in rewiring the transcriptional circuitry of SCZ.

Higher TCF4 gene network expression activity in NPCs may be more reflective of SCZ case-control difference in the prefrontal cortex

Although analyses of TCF4 knockdown in NPCs and Glut_Ns supported the role of TCF4 as an MR, the TCF4 gene network (interactome) expression activity, i.e., the correlation between TCF4 expression and its regulon’s expression patterns, may be different in NPCs and Glut_Ns cellular stages. This cell type–specific expression of the network activity may inform when the temporal expression of TCF4 is most relevant to SCZ. Toward this end, we carried out gene set enrichment analyses (GSEAs) in the CMC/CNON data, as well as the TCF4 knockdown RNA-seq data in NPCs and in Glut_Ns. We found that the SCZ case-control expression differences of TCF4 regulons in CMC data (i.e., prefrontal cortex) appeared to be more correlated with the TCF4 regulon expression changes upon TCF4 knockdown in NPCs than in Glut_Ns. To further demonstrate the closer similarity of the TCF4 interactome expression activity in the prefrontal cortex and in NPCs, we depicted the GSEA enrichment scores in three datasets (CMC/CNON, NPCs, and Glut_Ns) in a Circos plot (fig. S9A). We found that the pattern of SCZ case-control expression differences of TCF4 and its regulon in the prefrontal cortex appeared to be more similar to the pattern of higher TCF4 network expression activity in NPCs than in Glut_Ns. Similarly, the GSEA rank metric score of the TCF4 regulons also showed that the SCZ case-control differential TCF4 interactome expression pattern in the prefrontal cortex was more comparable to that in NPCs than in Glut_Ns (fig. S9B). We acknowledge that the prefrontal cortex, from which CMC data is generated, largely consists of differentiated cells. In this regard, our observation of higher TCF4 expression and its positively correlated regulon expression activity in NPCs is somewhat unexpected. One explanation could be that TCF4 expression peaks during early cortical development (40). One of the limitations of our observation is that both Glut_N and NPC represent early neurodevelopmental stages, which would not recapitulate the actual gene network in prefrontal cortex in adult brain. Nonetheless, our observation is intriguing and may arguably imply that TCF4 may be an SCZ risk factor at the early stages of neurodevelopment and neurogenesis, which warrants further investigation.

The TCF4 gene network in NPCs may be more relevant to SCZ disease biology

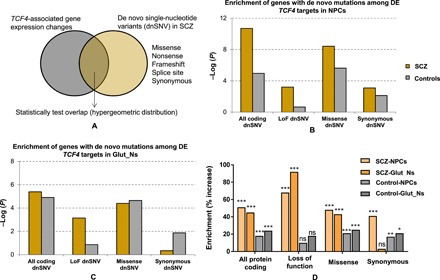

Given that the expression pattern of TCF4 and its regulons in the prefrontal cortex is more correlated to NPCs than Glut_Ns (fig. S9A), we reasoned that the TCF4 gene network in NPCs may be more relevant to SCZ disease biology. To test this hypothesis, we have examined the enrichments of genes regulated by TCF4 in NPCs, as compared to Glut_Ns for disease-relevant gene pathways, SCZ GWAS risk genes, and de novo SCZ mutations. We conducted a series of comparative tests. To test whether the TCF4 gene network acting in NPCs is more relevant to the genetic etiology of SCZ, we compared a list of known SCZ susceptibility genes from genome-wide significant risk loci (5) that showed gene expression change upon TCF4 knockdown in NPCs and in Glut_Ns. We found that 52 of those genes [out of the 148 genes reported in (5)] were altered by TCF4 across at least one of two time points in either NPCs or Glut_Ns. Of these 52 SCZ credible genes that showed TCF4-altered expression, 63.5% were uniquely found in NPCs (n = 33, Fisher’s exact test = 0.019, enrichment factor = 1.5), while 25% (n = 13, Fisher’s exact test = 0.950, enrichment factor = 0.6) were uniquely found in Glut_Ns (Fig. 3K). Furthermore, for the 92 SCZ-associated single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) that were indexed for genes related to neuronal electrical excitability and neurotransmission (41), 45 had altered expression by TCF4 knockdown in either NPCs or Glut_Ns. Among them, 24 genes (53.34%, Fisher’s exact test = 0.021, enrichment factor = 1.17) were uniquely found in NPCs, while only seven genes (15.6%, Fisher’s exact test = 0.90, enrichment factor = 0.54) were uniquely found in Glut_Ns (Fig. 3L). Similarly, we compiled 176 candidate SCZ risk genes from the CLOZUK GWAS study (42), and 54 genes were altered by TCF4 in either NPCs or Glut_Ns, where 72% (n = 39, Fisher’s exact test = 0.035, enrichment factor = 1.1) of the genes were uniquely found in NPCs compared to ~17% (n = 9, Fisher’s exact test = 0.98, enrichment factor = 0.36) of the genes uniquely found in Glut_Ns. Last, we conducted SCZ de novo SNV (dnSNV) enrichment analysis to probe the overlap of TCF4-associated gene expression changes and dnSNV previously reported in SCZ (Fig. 5A) using a list of de novo SNVs from patients with SCZ and control subjects (see Materials and Methods). We found that, while TCF4-affected genes in NPCs showed significant enrichment for both loss-of-function (LoF) and missense SCZ dnSNVs, and coding dnSNVs in general (Fig. 5, B and D), only LoF dnSNVs were enriched in Glut_Ns (Fig. 5, C and D). The analyses of both common variants and dnSNVs associated with SCZ in TCF4-affected genes nominated NPC as a more disease-relevant cell type and stage of development for the TCF4 gene network. Together, our results suggest that TCF4 and its regulons in the early stage of neurodevelopment and neurogenesis may be more relevant for SCZ pathogenesis. However, additional studies should be conducted to further validate this hypothesis.

Fig. 5. Enrichment of SCZ de novo SNVs in TCF4-associated gene expression changes from NPCs and Glut_Ns.

(A) Analysis framework. (B) Enrichment P values (−log10-transformed) of all DE genes at day 3 (NPCs). The P value on the y axis obtained from a hypergeometric test was used to test the statistical significance of each overlap (number of shared genes between lists) and using all protein coding genes as a background set. (C) Enrichment P values (−log10-transformed) of all DE genes at day 14 (Glut_Ns). (D) Enrichment of SCZ dnSNVs in TCF4-associated gene expression changes.

DISCUSSION

Like other complex disorders, SCZ is polygenic or even possibly omnigenic (9), with hundreds or even thousands of susceptibility genes each with a small effect size. A major challenge for understanding the biological implications of genetic findings is to identify the core gene networks in disease-relevant tissues or cell types (9). In this study, with the aim of uncovering the gene expression–mediating drivers that may contribute to SCZ pathogenesis, we have used an approach to assembling tissue-specific transcriptional regulatory networks on two independent RNA-seq datasets from DLPFC (CMC data) and cultured cells derived from olfactory neuroepithelium (CNON data). CNON was used as a validation dataset to evaluate whether findings from brain samples can be seen within in vitro cell culture that contains neuronal cells. We identified TCF4 as an MR based on the deconvolved transcriptional networks from the two independent datasets. For the predicted gene network of TCF4, a known leading SCZ GWAS locus, we have empirically validated the predicted TCF4 gene targets by analyzing both TF binding footprints in neuronal cells and by transcriptomic profiling of TCF4-associated gene expression changes in both hiPSC-derived NPCs and Glut_Ns upon TCF4 knockdown.

Compared to the commonly used weighted gene coexpression network analysis (43), the method used in our study aims to find MRs rather than to identify coexpression patterns, bearing a number of unique features, including the ability to elucidate potentially causal interactions, to illustrate the hierarchical structure of the identified transcriptional networks, and to identify potential feed-forward loops between MRs that may cause synergistic effects in the network. The confidence of the identified MRs and their subnetworks was further strengthened by their presence in both transcriptomic datasets and experimentally validated in hiPSC-derived neuronal cells using ATAC-seq data, ChIP-seq data, and transcriptomic profiling.

TCF4 is one of the leading SCZ risk genes identified by GWAS (5). However, the molecular mechanism underlying the genetic association remains elusive. Here, we have shown computationally that TCF4 is one of the top MRs of SCZ, and this was empirically validated in the hiPSC model of mental disorders. Although the downstream gene targets of TCF4 have been previously profiled in a neuroblastoma cell line (38), the hiPSC cellular model used here enabled us to examine the neurodevelopmental relevance of the TCF4 gene network. By examining the TCF4-pertubred gene networks in hiPSC-derived NPCs (early neuronal development/neurogenesis stage) and in differentiated Glut_Ns, we found that TCF4-altered genes in NPC are more enriched for gene pathways that are related to neuronal activities. Additional experiments on two independent cell lines from unaffected individuals further validated our findings as to how TCF4 targets a large body of genes in Glut_Ns. Furthermore, we have shown that TCF4-altered genes in NPC are more enriched for credible SCZ GWAS risk genes and for SCZ-associated dnSNVs. Thus, multiple lines of evidence from our study suggest that the TCF4 gene network expression activity in the early stages of neurodevelopment and neurogenesis may be more important for SCZ pathogenesis. In an attempt to further substantiate our findings on elucidating the transcriptional effects of TCF4, we combined the data from all three hiPSC lines (one SCZ case and two control lines) and identified differentially expressed genes upon TCF4 knockdown in Glut_Ns. This allowed us to boost the power of our analysis where we observed 5584 DE genes (FDR < 0.05) with 3017 up-regulated and 2567 down-regulated genes. Notably, we observed 47 DE genes overlapping with the 101 predicted TCF4 regulons (Fisher’s exact test, P = 1.3 × 10−5, fold enrichment = 1.83). This analysis further demonstrates the significance of our findings on the regulatory role of TCF4 on its regulons.

Although our empirical validation of MR has focused on TCF4, other MRs that we identified here suggest that additional gene networks are relevant to SCZ. The identified MRs contain many of the TFs previously reported in the literature that may potentially be involved in the pathogenesis of SCZ, such as JUND (44), NRG1 and GSK3B (45), and NFE2 and MZF1 (46). Among those newly identified MRs, methylation patterns of TMEM9 (47) have been reported to be associated with Parkinson’s disease, yet CRH is a protein-coding gene associated with Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and SCZ (48), and ARPP19 has been identified to be associated with nerve terminal function (49). A particularly noteworthy previously unidentified MR candidate is HDAC9, a histone deacetylase inhibitor that is important for chromatin remodeling. It has been shown to regulate mouse cortical neuronal dendritic complexities (50), as well as hippocampus-dependent memory and synaptic plasticity under different neuropsychiatric conditions (51). In our deconvoluted gene network of HDAC9, its regulons were moderately enriched for genes related to focal adhesion (P = 0.0115), a biological function that has been shown to be altered in SCZ (52). Of note, TCF4-altered genes in both NPCs and Glut_Ns also showed enrichment of focal adhesion pathway. The MRs we identified and their subnetworks may provide a rich resource of SCZ-relevant gene networks that can be perturbed to increase our understanding of SCZ disease pathophysiology. Moreover, we showed that, despite cross-individual genetic variations that may drive different expression patterns, TCF4 appears to be a strong SCZ MR in three different cell lines.

The selection of TCF4 as top MR candidate for validation was based on the consistency between CMC data and CNON datasets. However, we noted that TCF4 regulons predicted by CMC data and CNON data were different. This difference may have largely risen from the distinct cellular composition of the prefrontal cortex in CMC data and the primary olfactory neuroepithelium in CNON data. CMC data were generated from postmortem human prefrontal cortex, in which tens of different cell types might have been involved. On the other hand, CNON data, which were used as complementary data aimed at further probing the in silico effects of MRs on their targets, are less heterogeneous but with different cellular composition from the prefrontal cortex in CMC. We acknowledge that CNON could be a mixture of dividing neuronal cells and even epithelial cells. Nonetheless, our transcriptomic comparative analysis (fig. S11) indicated that the transcriptomic profiles of CNON, CMC samples, and our iPSC-derived NPCs were all moderately to highly correlated with each other and with GTEx brain frontal cortex and hippocampus (53), and CNON resembles CMC data more than NPCs. Alternatively, the different TCF4 regulons from the two different datasets may be due to the stochastic nature of network deconvolution approaches in general when sample size is moderate. The original developers recommended >100 samples in any analysis to reduce variation, and we had more than this recommended number in both datasets. Last, it is noteworthy that previous work also observed similar differences of predicted regulons when analyzing different cancer datasets from tissues and from cell lines (54). Thus, future network deconvolution in single cells within each cell type may minimize these variations.

Despite the possible effects of different cellular compositions on TCF4 regulons as discussed above, we have focused on our empirical validation in hiPSC-derived Glut_Ns. This is largely based on recent findings that show Glut_Ns to be one of the most relevant cell types to SCZ (55, 56). However, other cell types such as interneurons and microglia have also been implicated in pathogenesis of SCZ. Given cell type–specific expression profiles, the transcriptomic effects of TCF4 knockdown in different cell types are likely different to some extent, which would be an interesting future research subject. Furthermore, although our relatively homogeneous two-dimensional neuronal cultures (80 to 95%) have their advantages, they may not reflect the in vivo brain circuit where different cell types interact with each other. Therefore, it would be interesting to interrogate possible cell type–specific effects of TCF4 knockdown in a mixed cell culture or using brain organoids, followed by single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) analysis.

In summary, by using both a computational approach and a hiPSC neuronal developmental model, we have identified TCF4 as an MR that likely contributes to SCZ susceptibility at the early stages of neurodevelopment. Although powerful, we acknowledge the limitation of our approach in identifying top MRs, because selecting a top MR is not purely “data-driven”; for instance, TCF4 was identified as an MR among many other MRs and our selection of TCF4 as the top MR for validation was not only data-driven but also based on prior knowledge about the TCF4 association with SCZ. Nonetheless, our study suggests that MRs in SCZ can be identified by transcriptional network deconvolution and that MRs such as TCF4 as well as other MRs may constitute convergent gene networks that confer disease risk in a spatial and temporal manner. Therefore, TCF4 and other identified MRs may be a building block of SCZ polygenic/omnigenic architecture, which collectively drives SCZ onset and progression. Transcriptional network deconvolution in larger and more SCZ-relevant cell types/stages, combined with empirical network perturbation, will further deepen our understanding of the genetic contribution to SCZ disease biology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preprocessing of the RNA-seq datasets

RNA-seq data of DLPFC release 1.2 was downloaded from the “normalized SVA-corrected” directory of the CMC Knowledge Portal (www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn5609499) using Synapse Python client (http://docs.synapse.org/python/). The data being used in this study contained 307 SCZ cases and 245 controls where the paired-end RNA-seq data had been generated on an Illumina HiSeq 2500. Brain tissues in this dataset were obtained from several brain bank collections, including the Mount Sinai National Institutes of Health (NIH) Brain and Tissue Repository, the University of Pittsburgh NeuroBioBank and Brain and Tissue repositories, the University of Pennsylvania Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center, and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Human Brain Collection Core. Detailed procedure of tissue collection, sample preparation, data generation, and processing can be found in the CMC Knowledge Portal Wiki page (www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn2759792/wiki/69613).

The normalized RNA-seq read counts from 143 SCZ cases and 112 controls extracted from cultured primary neuronal cells derived from neuroepithelium were generated as previously described (24). Similar to the CMC data, the raw CNON data consisted of 100–base pair (bp) paired-end reads. The data had been preprocessed to exclude ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and mitochondrial genes. Later, normalized counts were calculated by the DESeq2 software.

Transcriptional network reconstruction

ARACNe, an information-theoretic algorithm for inferring transcriptional interactions, was used to identify candidate transcriptional regulators of the transcripts annotated to genes in both CMC and CNON data. First, mutual interaction between a candidate TF(x) and its potential target (y) was computed by pairwise MI, MI(x, y), using a Gaussian kernel estimator. A threshold was applied on MI based on the null hypothesis of statistical independence (P < 0.05, Bonferroni-corrected for the number of tested pairs). Second, the constructed network was trimmed by removing indirect interactions using the data processing inequality (DPI), a property of the MI. Therefore, for each (x, y) pair, a path through another TF(z) was considered, and every path pertaining to the following constraint was removed: MI(x, y) < min(MI(x, z),MI(z, y)). A P value threshold of 1 × 10−8 using DPI = 0.1 [as recommended (17)] was used when running ARACNe.

Virtual protein activity analysis

The regulon enrichment on gene expression signatures was tested by the VIPER algorithm. First, the gene expression signature was obtained by comparing two groups of samples representing distinctive phenotypes or treatments. In the next step, regulon enrichment on the gene expression signature can be computed using analytic rank-based enrichment analysis (56). At the end, significance values (P value and normalized enrichment score) were computed by comparing each regulon enrichment score to a null model generated by randomly and uniformly permuting the samples 1000 times. The output of VIPER is a list of highly active MRs as well as their activity scores and their enrichment P values. Further information about VIPER can be accessed in (18).

TF binding site enrichment analysis (TFBEA) and footprint analysis

Human reference genome (hg19) was used to extract the DNA sequence around TSSs for TFBEA. We obtained the gene coordinates from the Ensembl BioMart tool (57) and scanned 2000 bp upstream and 1000 bp downstream of the TSS. The motifs of the TFs were obtained from JASPAR, and the extracted sequences of each target were then fed into JASPAR and analyzed versus their corresponding TFs. Then, using the position weight matrix (PWM) of the TF, JASPAR used the modified Needleman-Wunsch algorithm to align the motif sequence with the target sequence in that the input sequence is scanned to check whether or not the motif is enriched. The output is the enrichment score of the input TF in the designated target genes.

We used PIQ to assess the local TF occupancy footprint from ATAC-seq data (33, 34). We extracted the corresponding BED files for TF footprint analysis using the PIQ R package. All the footprints were annotated using the TF matrix with the names of different TFs annotated in the BED files. For each sample, footprints were generated using three different PIQ purity scores (0.7, 0.8, or 0.9; equivalent to an FDR of 0.3, 0.2, or 0.1, respectively). The corresponding files were then extracted using the MR list, and the peak names/coordinates containing TCF4 gene were collected as a subset of the original BED file. These subsets of genomic coordination were then annotated using the findPeaks.pl included in the HOMER package with the hg19 reference genome.

hiPSC generation and cell culture

The hiPSC lines used for deriving neurons were generated using the Sendai virus method at the Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository–NIMH Stem Cell Center from cryopreserved lymphocytes of the Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia (MGS) collection (58). The patient line was derived from a 29-year-old male patient with SCZ (cell line ID: 07C65853), and the other two lines were derived from unaffected controls (cell line IDs: 05C39664 and 05C43758, designated as CD07 and CD09, respectively). All three lines do not have large CNVs associated with SCZ. The NorthShore University HealthSystem Institutional Review Board approved the study. hiPSCs were cultured using the feeder-free method in Geltrex (Thermo Fisher Scientific)–coated plates in mTeSR1 medium (StemCell). The media were changed daily, and cells were passaged as clumps every 5 days using ReLeSR (StemCell) in the presence of 5 μm ROCK inhibitor (R&D Systems). hiPSCs were characterized by positive IF staining of pluripotent stem cell markers OCT4, TRA-1-60, NANOG, and SSEA4 (Fig. 3, A and B).

hiPSC-derived NPCs

NPCs were differentiated from hiPSCs using the PSC Neural Induction Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with modifications. In brief, hiPSCs were replated as clumps in Geltrex (Thermo Fisher Scientific)–coated six-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in mTeSR1 (StemCell) on day 0. From day 2, the medium was switched to PSC Neural Induction Medium and changed daily. On day 11, NPCs were harvested using Neural Rosette Selection Reagent (StemCell). NPCs were maintained in Neural Expansion Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and were passaged every 4 to 6 days in the presence of 5 μM ROCK inhibitor (R&D Systems) until the fourth passage (P4). P4 NPCs were characterized by positive IF staining for Nestin and Pax6 (Fig. 3, C and D).

hiPSC differentiation and shRNA-mediated TCF4 (ITF-2) knockdown

hiPSC-derived NPCs were plated at a density of 3 × 105 per well in a 12-well plate precoated with Geltrex for 2 hours. The differentiation media used for induced differentiation of NPCs contain neural basal medium, B-27 supplement, l-glutamine, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (10 ng/ml), glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor (10 ng/ml), and NT-3 (10 ng/ml) (34). NPCs were allowed to grow and differentiate for 3 or 14 days after induction. At the corresponding day, 20 μl (1.0 × 105 infectious units of virus) of either TCF4 or control shRNA lentiviral particles (Santa Cruz sc-61657-V for TCF4, which contains a pool of three target-specific, propriety constructs targeting human TCF4 gene locus at 18q21.2, and sc-108080 for control, which contains a set of scrambled nonspecific shRNA sequence) was added into each well (three replicates for each group), and the transduced cells were further cultured for 48 hours before collection. Total RNAs were extracted from homogenized cell lysate using the RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen), and the quality of extracted total RNA was examined using NanoDrop spectrum analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis. The day 14 excitatory neurons were characterized by positive IF staining for VGLUT1 (Fig. 3E).

qPCR validation of TCF4 shRNA knockdown efficiency

We used qPCR to verify the knockdown efficiency of shRNA before applying RNA-seq. Briefly, cDNAs were reverse-transcribed from total RNAs using the High-Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Fifty nanograms of total RNA was used for each reverse-transcription (RT) reaction (20 μl), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was diluted 15-fold before applying it to qPCR. Subsequent qPCR analysis was performed on a Roche LightCycler 480 II real-time PCR machine using TaqMan probes against TCF4 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (as internal reference). Briefly, 5 μl of diluted RT product was applied to each 10 μl of qPCR reaction using the TaqMan Universal Amplification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific/Applied Biosystems) with customized TaqMan probes (Hs.PT.58.21450367 for TCF4, Integrated DNA Technologies, and Hs03929097_g1 for GAPDH, Applied Biosystems). Cycle parameters were as follows: 95°C, 10 min; 95°C, 15 s; 60°C, 1 min, 45 cycles. Data analysis was performed using the build-in analysis software of Roche 480 II with relative quantification (ΔΔCt method applied).

RNA-seq analysis on hiPSC-derived NPCs and Glut_Ns

RNA-seq libraries were prepared from total RNAs from the collected neuronal cells of 12 samples (three biological replicates, i.e., independent cell cultures, of four distinct groups). These sample groups are for TCF4 expression knockdown and control at hiPSC-derived NPC stage (day 3 after differentiation) and Glut_N stage (day 14 after differentiation). Total RNAs were extracted as described above. Three main methods for quality control (QC) of RNA samples were conducted, including (i) preliminary quantification, (ii) testing RNA degradation and potential contamination (Agarose Gel Electrophoresis), and (iii) checking RNA integrity and quantification (Agilent 2100) (10). After the QC procedures, a library was constructed and library QC was conducted consisting of three steps, including (i) testing the library concentration (Qubit 2.0), (ii) testing the insert size (Agilent 2100), and (iii) precise quantification of library effective concentration (qPCR) (10). The quantified libraries were then sequenced using Illumina HiSeq sequencers with 150-bp paired-end reads, after pooling according to its effective concentration and expected data volume.

The paired-end sequenced reads for each sample were obtained as FASTQ files. Initial quality check of the raw data was performed using FastQC. All FASTQ files passed the QC stage, including removing low-quality bases, adapters, short sequences, and checking for rRNA contamination. The average number of preprocessed reads per sample was ~22,740,000. High-quality reads were mapped to the reference genome GRCh38 using STAR (59). Sorting and counting were also performed using STAR based on the procedure recommended by the developers. To detect DE genes, the output read counts were fed to edgeR software package (60). Normalization, batch correction, and differential expression analysis were conducted using the recommended settings.

Pathway enrichment and GO analysis

Pathway enrichment and GO analysis were conducted using WebGestalt (31) v. 2017. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) was used as the functional database where the list of expressed genes, with fragments per kilobase of transcript per million (FPKM) >1, was used as the background. The maximum and minimum number of genes for each category were set to 2000 and 5, respectively, based on the default setting. Bonferroni-Hochberg multiple test adjustment was applied to the enrichment output. FDR significance threshold was set to 0.05.

MetaCore pathway analysis

Ensembl transcript IDs of differentially expressed genes were imported in MetaCore (v6.32) and processed using the “enrichment analysis” workflow. For each time point (day 3 or day 14), all the up-regulated (FDR < 0.05), all the down-regulated (FDR < 0.05), and the top 2000 differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05) were analyzed. Each list was compared to a defined background set of genes consisting of all the expressed transcripts (FPKM > 1) at the relevant time point (day 3 or day 14). The “pathway maps” or “process networks” that were enriched in each analysis were considered significant when FDR < 0.05.

Enrichment analysis on de novo mutations in SCZ

Data on de novo variants in SCZ and controls were obtained from http://denovo-db.gs.washington.edu/denovo-db (accessed 11 April 2017) (61). Variants identified in patients with SCZ and control subjects were stratified into four categories (all protein coding, missense, loss of function, and synonymous) based on annotations from the denovo-db. To generate a list of variants affecting protein coding (“all protein coding”), de novo variants outside exonic coding regions were excluded [including those in 5′ untranslated regions (5′UTRs), 3′UTRs, intronic and intergenic regions, and noncoding exons], as well as synonymous variants. The “loss-of-function” list included frameshift, stop gained, stop lost, start lost, splice acceptor, and donor variants. We then compiled a total of six lists containing different sets of differentially expressed genes from the TCF4 knockdown (KD) experiments at day 3 and day 14, as follows: day3_all_sig (all differentially expressed genes FDR < 0.05; 4898 genes), day3_up_sig (all up-regulated genes FDR < 0.05; 2332 genes), day3_down_sig (all down-regulated genes FDR < 0.05; 2566 genes), day14_all_sig (all differentially expressed genes FDR < 0.05; 3156 genes), day14_up_sig (all up-regulated genes FDR < 0.05; 1864 genes), day14_down_sig (all down-regulated genes FDR < 0.05; 1292 genes). Each of the de novo lists for SCZ and controls was intersected with the relevant list of differentially expressed genes from the TCF4 KD experiments to determine the shared number of genes in each comparison. A hypergeometric test was used to test the statistical significance of each overlap (number of shared genes between lists) and using all protein coding genes as a background set (20,338, human genome build GRCh38.p10). The data were displayed as the −log10 (P value) for each comparison.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the CMC for generating the RNA-seq data on DLPFC from patients and control subjects (the data were generated as part of the CMC supported by funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Limited, F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd., and NIH grants R01MH085542, R01MH093725, P50MH080405, R01MH097276, R01MH075916, P50MH096891, P50MH084053S1, R37MH057881, R37MH057881S1, HHSN271201300031C, AG02219, AG05138, and MH06692). We thank the developers of the ARACNe software for comments on the software usage, and we thank the Wang lab members for helpful suggestions and discussions. Funding: This study was supported by NIH grant MH108728 (to K.W.), the Alavi-Dabiri Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (to A.D.T.), HG006465 (to K.W.), the CHOP Research Institute (to K.W.), MH086874 (O.V.E. and J.A.K.), MH102685, MH106575, and MH116281 (to J.D.). Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Author contributions: A.D.T. conceived the study, designed the study, performed the computational experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. C.A., O.V.E., T.S., and J.A.K. generated and preprocessed the CNON data and edited the manuscript. S.Z. and H.Z. generated hiPSCs, conducted TCF4 knockdown and other experiments, and wrote the relevant Materials and Methods sections. M.P.F. advised on the study and performed additional enrichment analysis on TCF4. K.W. conceived the study, wrote and edited the manuscript, and supervised the project. J.D. supervised the experimental sections of the study and wrote and edited the manuscript. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Data generated in this study are deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE128333. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/9/eaau4139/DC1

Fig. S1. Representation of the top active MRs identified in the CMC data.

Fig. S2. GOSlim summary of the up-regulated genes on day 3.

Fig. S3. GOSlim summary of the down-regulated genes on day 3.

Fig. S4. GOSlim summary of the up-regulated genes on day 14.

Fig. S5. GOSlim summary of the down-regulated genes on day 14.

Fig. S6. Biological pathways altered upon TCF4 knockdown in hiPSC-derived neuronal cells.

Fig. S7. MetaCore analysis of top 2000 dysregulated genes upon TCF4 knockdown in hiPSC-derived neurons.

Fig. S8. MetaCore analysis of all gene sets dysregulated upon TCF4 knockdown in hiPSC-derived neurons.

Fig. S9. The identified TCF4 interactome and their contributions to expression of TCF4.

Fig. S10. Batch correction of CD07 cell line data.

Fig. S11. Correlations between the expression profile (summarized as median gene expression of each gene across samples) of the CMC, CNON, and NPC data with the 53 tissues from the GTEx consortium.

Table S1. Targets of the identified hub genes in the CMC network.

Table S2. Network structure created from the CMC data.

Table S3. Network structure created from the CNON data.

Table S4. Targets of the identified hub genes in the CNON network.

Table S5. Targets of five MRs in the CMC and CNON data.

Table S6. List of the altered pathway upon TCF4 knockdown in NPCs and Glut_Ns in the SCZ cell line.

Table S7. List of differentially expressed genes in NPCs and Glut_Ns in the SCZ cell line.

Table S8. MetaCore enrichment analysis on NPCs in the SCZ cell line.

Table S9. MetaCore enrichment analysis on Glut_Ns in the SCZ cell line.

Table S10. List of TCF4 targets in other studies.

Table S11. VIPER enrichment scores of the identified MRs in the CMC and CNON data.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.McGrath J., Saha S., Chant D., Welham J., Schizophrenia: A concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol. Rev. 30, 67–76 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler R. C., Birnbaum H., Demler O., Falloon I. R., Gagnon E., Guyer M., Howes M. J., Kendler K. S., Shi L., Walters E., Wu E. Q., The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Biol. Psychiatry 58, 668–676 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilker R., Helenius D., Fagerlund B., Skytthe A., Christensen K., Werge T. M., Nordentoft M., Glenthoj B., Heritability of schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum based on the nationwide Danish Twin register. Biol. Psychiatry 83, 492–498 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rees E., O’Donovan M. C., Owen M. J., Genetics of schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2, 8–14 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium , Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511, 421–427 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall C. R., Howrigan D. P., Merico D., Thiruvahindrapuram B., Wu W., Greer D. S., Antaki D., Shetty A., Holmans P. A., Pinto D., Gujral M., Brandler W. M., Malhotra D., Wang Z., Fajarado K. V. F., Maile M. S., Ripke S., Agartz I., Albus M., Alexander M., Amin F., Atkins J., Bacanu S. A., Belliveau R. A. Jr., Bergen S. E., Bertalan M., Bevilacqua E., Bigdeli T. B., Black D. W., Bruggeman R., Buccola N. G., Buckner R. L., Bulik-Sullivan B., Byerley W., Cahn W., Cai G., Cairns M. J., Campion D., Cantor R. M., Carr V. J., Carrera N., Catts S. V., Chambert K. D., Cheng W., Cloninger C. R., Cohen D., Cormican P., Craddock N., Crespo-Facorro B., Crowley J. J., Curtis D., Davidson M., Davis K. L., Degenhardt F., Del Favero J., DeLisi L. E., Dikeos D., Dinan T., Djurovic S., Donohoe G., Drapeau E., Duan J., Dudbridge F., Eichhammer P., Eriksson J., Escott-Price V., Essioux L., Fanous A. H., Farh K.-H., Farrell M. S., Frank J., Franke L., Freedman R., Freimer N. B., Friedman J. I., Forstner A. J., Fromer M., Genovese G., Georgieva L., Gershon E. S., Giegling I., Giusti-Rodríguez P., Godard S., Goldstein J. I., Gratten J., de Haan L., Hamshere M. L., Hansen M., Hansen T., Haroutunian V., Hartmann A. M., Henskens F. A., Herms S., Hirschhorn J. N., Hoffmann P., Hofman A., Huang H., Ikeda M., Joa I., Kähler A. K., Kahn R. S., Kalaydjieva L., Karjalainen J., Kavanagh D., Keller M. C., Kelly B. J., Kennedy J. L., Kim Y., Knowles J. A., Konte B., Laurent C., Lee P., Lee S. H., Legge S. E., Lerer B., Levy D. L., Liang K.-Y., Lieberman J., Lönnqvist J., Loughland C. M., Magnusson P. K. E., Maher B. S., Maier W., Mallet J., Mattheisen M., Mattingsdal M., McCarley R. W., McDonald C., McIntosh A. M., Meier S., Meijer C. J., Melle I., Mesholam-Gately R. I., Metspalu A., Michie P. T., Milani L., Milanova V., Mokrab Y., Morris D. W., Müller-Myhsok B., Murphy K. C., Murray R. M., Myin-Germeys I., Nenadic I., Nertney D. A., Nestadt G., Nicodemus K. K., Nisenbaum L., Nordin A., O’Callaghan E., O’Dushlaine C., Oh S.-Y., Olincy A., Olsen L., O’Neill F. A., Van Os J., Pantelis C., Papadimitriou G. N., Parkhomenko E., Pato M. T., Paunio T.; Psychosis Endophenotypes International Consortium, Perkins D. O., Pers T. H., Pietilainen O., Pimm J., Pocklington A. J., Powell J., Price A., Pulver A. E., Purcell S. M., Quested D., Rasmussen H. B., Reichenberg A., Reimers M. A., Richards A. L., Roffman J. L., Roussos P., Ruderfer D. M., Salomaa V., Sanders A. R., Savitz A., Schall U., Schulze T. G., Schwab S. G., Scolnick E. M., Scott R. J., Seidman L. J., Shi J., Silverman J. M., Smoller J. W., Söderman E., Spencer C. C. A., Stahl E. A., Strengman E., Strohmaier J., Stroup T. S., Suvisaari J., Svrakic D. M., Szatkiewicz J. P., Thirumalai S., Tooney P. A., Veijola J., Visscher P. M., Waddington J., Walsh D., Webb B. T., Weiser M., Wildenauer D. B., Williams N. M., Williams S., Witt S. H., Wolen A. R., Wormley B. K., Wray N. R., Wu J. Q., Zai C. C., Adolfsson R., Andreassen O. A., Blackwood D. H. R., Bramon E., Buxbaum J. D., Cichon S., Collier D. A., Corvin A., Daly M. J., Darvasi A., Domenici E., Esko T., Gejman P. V., Gill M., Gurling H., Hultman C. M., Iwata N., Jablensky A. V., Jonsson E. G., Kendler K. S., Kirov G., Knight J., Levinson D. F., Li Q. S., McCarroll S. A., McQuillin A., Moran J. L., Mowry B. J., Nothen M. M., Ophoff R. A., Owen M. J., Palotie A., Pato C. N., Petryshen T. L., Posthuma D., Rietschel M., Riley B. P., Rujescu D., Sklar P., St Clair D., Walters J. T. R., Werge T., Sullivan P. F., O’Donovan M. C., Scherer S. W., Neale B. M., Sebat J.; CNV and Schizophrenia Working Groups of the Psychiatric Genomics , Contribution of copy number variants to schizophrenia from a genome-wide study of 41,321 subjects. Nat Genet. 49, 27–35 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genovese G., Fromer M., Stahl E. A., Ruderfer D. M., Chambert K., Landén M., Moran J. L., Purcell S. M., Sklar P., Sullivan P. F., Hultman C. M., McCarroll S. A., Increased burden of ultra-rare protein-altering variants among 4,877 individuals with schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1433–1441 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh T., Kurki M. I., Curtis D., Purcell S. M., Crooks L., McRae J., Suvisaari J., Chheda H., Blackwood D., Breen G., Pietiläinen O., Gerety S. S., Ayub M., Blyth M., Cole T., Collier D., Coomber E. L., Craddock N., Daly M. J., Danesh J., DiForti M., Foster A., Freimer N. B., Geschwind D., Johnstone M., Joss S., Kirov G., Körkkö J., Kuismin O., Holmans P., Hultman C. M., Iyegbe C., Lönnqvist J., Männikkö M., McCarroll S. A., McGuffin P., McIntosh A. M., McQuillin A., Moilanen J. S., Moore C., Murray R. M., Newbury-Ecob R., Ouwehand W., Paunio T., Prigmore E., Rees E., Roberts D., Sambrook J., Sklar P., St Clair D., Veijola J., Walters J. T., Williams H., Schizophrenia S. S.; INTERVAL Study; DDD Study; UK10 K Consortium, Sullivan P. F., Hurles M. E., O’Donovan M. C., Palotie A., Owen M. J., Barrett J. C., Rare loss-of-function variants in SETD1A are associated with schizophrenia and developmental disorders. Nat Neurosci. 19, 571–577 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle E. A., Li Y. I., Pritchard J. K., An expanded view of complex traits: From polygenic to omnigenic. Cell 169, 1177–1186 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mondragón E., Maher L. J. III, Anti-transcription factor RNA aptamers as potential therapeutics. Nucleic Acid Ther 26, 29–43 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corbett B. F., You J. C., Zhang X., Pyfer M. S., Tosi U., Iascone D. M., Petrof I., Hazra A., Fu C. H., Stephens G. S., Ashok A. A., Aschmies S., Zhao L., Nestler E. J., Chin J., ΔFosB regulates gene expression and cognitive dysfunction in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Cell Rep. 20, 344–355 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lizio M., Harshbarger J., Shimoji H., Severin J., Kasukawa T., Sahin S., Abugessaisa I., Fukuda S., Hori F., Ishikawa-Kato S., Mungall C. J., Arner E., Baillie J. K., Bertin N., Bono H., de Hoon M., Diehl A. D., Dimont E., Freeman T. C., Fujieda K., Hide W., Kaliyaperumal R., Katayama T., Lassmann T., Meehan T. F., Nishikata K., Ono H., Rehli M., Sandelin A., Schultes E. A., ‘t Hoen P. A., Tatum Z., Thompson M., Toyoda T., Wright D. W., Daub C. O., Itoh M., Carninci P., Hayashizaki Y., Forrest A. R., Kawaji H.; FANTOM Consortium , Gateways to the FANTOM5 promoter level mammalian expression atlas. Genome Biol. 16, 22 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaquerizas J. M., Kummerfeld S. K., Teichmann S. A., Luscombe N. M., A census of human transcription factors: Function, expression and evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 252–263 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han H., Shim H., Shin D., Shim J. E., Ko Y., Shin J., Kim H., Cho A., Kim E., Lee T., Kim H., Kim K., Yang S., Bae D., Yun A., Kim S., Kim C. Y., Cho H. J., Kang B., Shin S., Lee I., TRRUST: A reference database of human transcriptional regulatory interactions. Sci. Rep. 5, 11432 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan I. K., Mariño-Ramírez L., Wolf Y. I., Koonin E. V., Conservation and coevolution in the scale-free human gene coexpression network. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 2058–2070 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basso K., Margolin A. A., Stolovitzky G., Klein U., Dalla-Favera R., Califano A., Reverse engineering of regulatory networks in human B cells. Nat. Genet. 37, 382–390 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Margolin A. A., Wang K., Lim W. K., Kustagi M., Nemenman I., Califano A., Reverse engineering cellular networks. Nat. Protoc. 1, 662–671 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarez M. J., Shen Y., Giorgi F. M., Lachmann A., Ding B. B., Ye B. H., Califano A., Functional characterization of somatic mutations in cancer using network-based inference of protein activity. Nat. Genet. 48, 838–847 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brichta L., Shin W., Jackson-Lewis V., Blesa J., Yap E. L., Walker Z., Zhang J., Roussarie J. P., Alvarez M. J., Califano A., Przedborski S., Greengard P., Identification of neurodegenerative factors using translatome–regulatory network analysis. Nat Neurosci. 18, 1325–1333 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haroutunian V., Katsel P., Dracheva S., Stewart D. G., Davis K. L., Variations in oligodendrocyte-related gene expression across multiple cortical regions: Implications for the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 10, 565–573 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arion D., Horváth S., Lewis D. A., Mirnics K., Infragranular gene expression disturbances in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia: Signature of altered neural development? Neurobiol. Dis. 37, 738–746 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guillozet-Bongaarts A. L., Hyde T. M., Dalley R. A., Hawrylycz M. J., Henry A., Hof P. R., Hohmann J., Jones A. R., Kuan C. L., Royall J., Shen E., Swanson B., Zeng H., Kleinman J. E., Altered gene expression in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 478–485 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fromer M., Roussos P., Sieberts S. K., Johnson J. S., Kavanagh D. H., Perumal T. M., Ruderfer D. M., Oh E. C., Topol A., Shah H. R., Klei L. L., Kramer R., Pinto D., Gümüs Z. H., Cicek A. E., Dang K. K., Browne A., Lu C., Xie L., Readhead B., Stahl E. A., Xiao J., Parvizi M., Hamamsy T., Fullard J. F., Wang Y. C., Mahajan M. C., Derry J. M., Dudley J. T., Hemby S. E., Logsdon B. A., Talbot K., Raj T., Bennett D. A., De Jager P. L., Zhu J., Zhang B., Sullivan P. F., Chess A., Purcell S. M., Shinobu L. A., Mangravite L. M., Toyoshiba H., Gur R. E., Hahn C. G., Lewis D. A., Haroutunian V., Peters M. A., Lipska B. K., Buxbaum J. D., Schadt E. E., Hirai K., Roeder K., Brennand K. J., Katsanis N., Domenici E., Devlin B., Sklar P., Gene expression elucidates functional impact of polygenic risk for schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci. 19, 1442–1453 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O. V. Evgrafov, C. Armoskus, B. B. Wrobel, V. N. Spitsyna, T. Souaiaia, J. S. Herstein, C. P. Walker, J. D. Nguyen, A. Camarena, J. R. Weitz, J. M. H. Kim, E. Lopez Duarte, K. Wang, G. M. Simpson, J. L. Sobell, H. Medeiros, M. T. Pato, C. N. Pato, J. A. Knowles, Gene expression in patient-derived neural progenitors provide insights into neurodevelopmental aspects of schizophrenia. bioRxiv 209197 [Preprint] 26 October 2017. 10.1101/209197. [DOI]

- 25.Lefebvre C., Rajbhandari P., Alvarez M. J., Bandaru P., Lim W. K., Sato M., Wang K., Sumazin P., Kustagi M., Bisikirska B. C., Basso K., Beltrao P., Krogan N., Gautier J., Dalla-Favera R., Califano A., A human B-cell interactome identifies MYB and FOXM1 as master regulators of proliferation in germinal centers. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6, 377 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang K., Sawa A., Open sesame: Open chromatin regions shed light onto non-coding risk variants. Cell Stem Cell 21, 285–287 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lake B. B., Chen S., Sos B. C., Fan J., Kaeser G. E., Yung Y. C., Duong T. E., Gao D., Chun J., Kharchenko P. V., Zhang K., Integrative single-cell analysis of transcriptional and epigenetic states in the human adult brain. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 70–80 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinberg S., de Jong S.; Irish Schizophrenia Genomics Cosortium, Andreassen O. A., Werge T., Børglum A. D., Mors O., Mortensen P. B., Gustafsson O., Costas J., Pietiläinen O. P., Demontis D., Papiol S., Huttenlocher J., Mattheisen M., Breuer R., Vassos E., Giegling I., Fraser G., Walker N., Tuulio-Henriksson A., Suvisaari J., Lönnqvist J., Paunio T., Agartz I., Melle I., Djurovic S., Strengman E.; GROUP, Jürgens G., Glenthøj B., Terenius L., Hougaard D. M., Ørntoft T., Wiuf C., Didriksen M., Hollegaard M. V., Nordentoft M., van Winkel R., Kenis G., Abramova L., Kaleda V., Arrojo M., Sanjuán J., Arango C., Sperling S., Rossner M., Ribolsi M., Magni V., Siracusano A., Christiansen C., Kiemeney L. A., Veldink J., van den Berg L., Ingason A., Muglia P., Murray R., Nöthen M. M., Sigurdsson E., Petursson H., Thorsteinsdottir U., Kong A., Rubino I. A., De Hert M., Réthelyi J. M., Bitter I., Jönsson E. G., Golimbet V., Carracedo A., Ehrenreich H., Craddock N., Owen M. J., O’Donovan M. C.; Wellcome Trust Case Control Costortium 2, Ruggeri M., Tosato S., Peltonen L., Ophoff R. A., Collier D. A., St Clair D., Rietschel M., Cichon S., Stefansson H., Rujescu D., Stefansson K., Common variants at VRK2 and TCF4 conferring risk of schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet 20, 4076–4081 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kharbanda M., Kannike K., Lampe A., Berg J., Timmusk T., Sepp M., Partial deletion of TCF4 in three generation family with non-syndromic intellectual disability, without features of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 59, 310–314 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forrest M. P., Hill M. J., Quantock A. J., Martin-Rendon E., Blake D. J., The emerging roles of TCF4 in disease and development. Trends Mol. Med. 20, 322–331 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J., Duncan D., Shi Z., Zhang B., WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt): Update 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W77–W83 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]