Abstract

It is well-known that high protein intake increases glomerular filtration rate. Evidence from several studies indicated that nitric oxide and tubuloglomerular feedback mediate the effect. However, a recent study with a neuronal nitric oxide synthase α knockout model refuted this mechanism and concluded that neither neuronal nitric oxide synthase nor tubuloglomerular feedback response is involved in the protein-induced hyperfiltration. To examine the discrepancy, this study tested a hypothesis that neuronal nitric oxide synthase β in the macula densa mediates the high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration via tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism.

We examined the effects of high protein intake on nitric oxide generation at the macula densa, tubuloglomerular feedback response, and glomerular filtration rate in wild-type and macula densa–specific neuronal nitric oxide synthase knockout mice. In wild-type mice, high protein diet increased kidney weight, glomerular filtration rate and renal blood flow, while reduced renal vascular resistance. Tubuloglomerular feedback response in vivo and in vitro were blunted and nitric oxide generation in the macula densa was increased following high protein diet, associated with upregulations of neuronal nitric oxide synthase β expression and phosphorylation at Ser1417. In contrast, these high protein diet-induced changes in nitric oxide generation at the macula densa, tubuloglomerular feedback response, renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate in wild-type mice were largely attenuated in macula densa–specific neuronal nitric oxide synthase knockout mice.

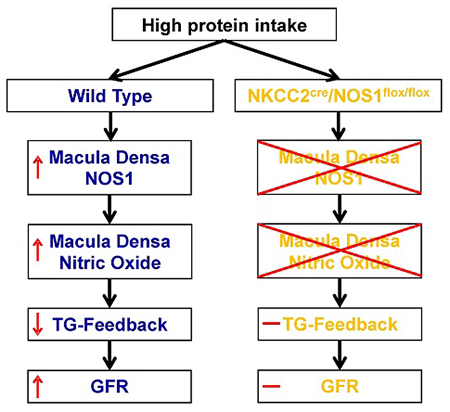

In conclusion, we demonstrated that high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration is dependent on neuronal nitric oxide synthase β in the macula densa via tubuloglomerular feedback response.

Keywords: high protein diet, glomerular filtration rate, tubuloglomerular feedback, neuronal nitric oxide synthase, renal physiology, nutrition

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

High protein diet is well-known to increase glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in humans1,2 and experimental animals,3–5 associated with an increased long-term risk for renal damage.6–9 The mechanism for the renal hemodynamic responses to high protein diet has been extensively investigated. Several studies from different laboratories provided strong evidence for the central role of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS1) and tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) mechanism in high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration. TGF response was reported to be less sensitive in Sprague-Dawley rats fed with high protein diet than low protein diet.3,10 In addition, administration of furosemide, a potent inhibitor of Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (NKCC2), completely blocks the high protein meal-induced increases of GFR in dogs.11 Moreover, Yao et al. showed that cortical NOS1 expression is increased in Sprague-Dawley rats with high protein intake, and inhibition of NOS1 activity with 7-nitroindazole abolishes the high protein diet-induced hyperfiltration.12

However, a recent study13 using a global NOS1 deletion model disputed the above mechanism. The results of this study showed that the global NOS1 knockout mice had a similar increase in GFR compared with the wild types on high protein diet. Consequently, the authors concluded that the high protein intake-induced glomerular hyperfiltration is independent of macula densa NOS1-mediated TGF mechanism. Actually, we recently found that macula densa cells express both α and β splice variants of NOS1; NOS1β is the primary splice variant and contributes to most of the nitric oxide (NO) generation by the macula densa;14,15 moreover, the global NOS1 knockout model is a NOS1α knockout and the NOS1β is intact.16 Therefore, macula densa NO generation and TGF responsiveness were not significantly affected in this global NOS1α deletion model.14,15

Recently, our laboratory generated a macula densa-specific NOS1 knockout (KO) mouse strain by crossing an NKCC2-Cre line (NKCC2cre) with an NOS1-floxed line (NOS1flox/flox). This floxed mouse line targets the exon 6 of NOS1 gene and excision of this exon by Cre recombinase inactivates all splice variants of NOS1.14,17 Furthermore, because the expression of NOS1 is negligible in the thick ascending limb of loop of Henle (TAL) compared with that in the macula densa,18,19 this NKCC2cre/NOS1flox/flox strain is considered as a macula densa–selective NOS1 knockout model. Thus, in the present study, this KO model was utilized to determine the significance of macula densa NOS1β-mediated TGF mechanism in high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration. The changes of expression and phosphorylation of NOS1 splice variants, NO generation at the macula densa, TGF response, renal blood flow (RBF) and GFR in response to high protein intake were assessed and compared between the KO and wild type mice.

METHODS

Data, analytical methods, and study materials are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The detail methods are available in the online supplement.

Animals

C57BL/6 mice (male, 12 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. The KO mice (male, 12 weeks old) were generated by crossing NKCC2cre mice with NOS1flox/flox mice as we described previously.14 The number of animal used was indicated in the figure legends. Mice were fed either 40% protein diet (high protein diet group) or 6% protein diet (low protein diet group) for 4 weeks. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of South Florida, College of Medicine.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software; San Diego, CA). The effects of interest were tested using t-test, or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Sidak multiple comparisons test when appropriate. Data were presented as a mean ± SEM, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

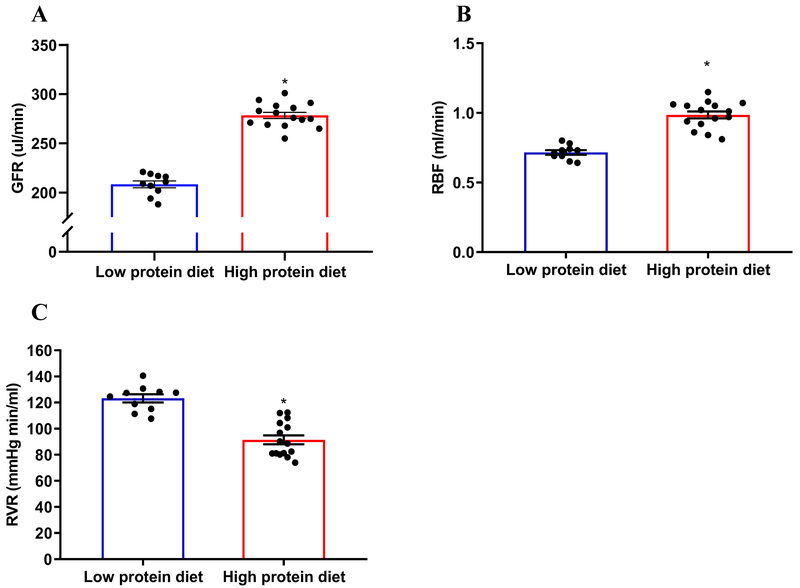

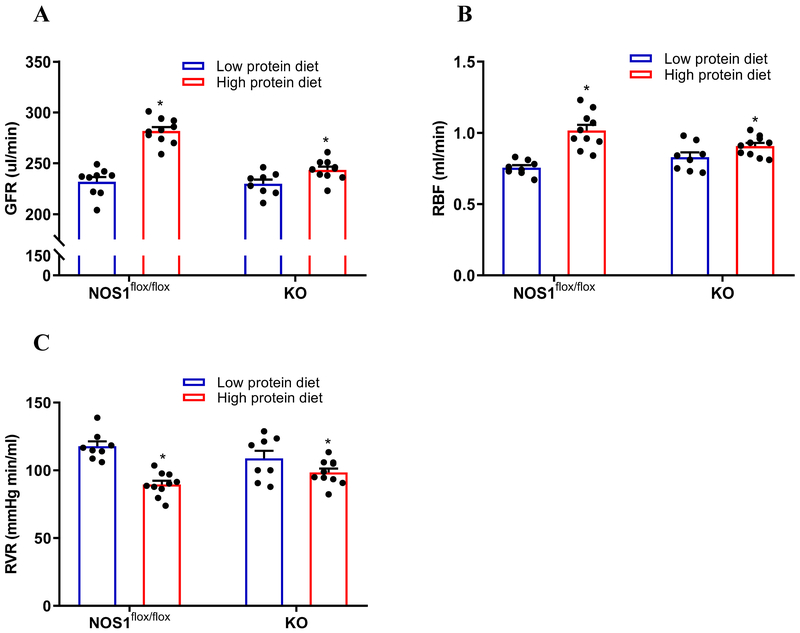

A high protein diet induces glomerular hyperfiltration and kidney hypertrophy

Following a 4 weeks diet, GFR was significant higher in the mice fed the high protein diet (278.4±12.2 µl/min) than low protein diet (208.4±10.9 µl/min) (Figure 1A); RBF was significant higher in high protein diet group (0.98±0.09) compared with low protein diet group (0.71±0.05 ml/min) (Figure 1B); the RVR was significant lower in high protein diet group (91.4±13.2 mmHg min/mL) compared with low protein diet group (123.2±9.9 mmHg min/ml) (Figure 1C). In addition, the kidney weight was greater in high protein diet group than low protein diet group, while the body weight was not significantly different between high protein diet and low protein diet groups (Supplemental Table S1). These data demonstrated that an increased intake of protein results in glomerular hyperfiltration, as well as kidney hypertrophy.

Figure 1. High protein diet induces significant rises in GFR and RBF, as well as reduction in calculated RVR.

(A) High protein diet resulted in higher GFR compared with low protein diet; n=10-15; *P<0.01 versus low protein diet. (B and C) High protein diet resulted in higher RBF and lower RVR compared with low protein diet; n=10-15; *P<0.01 versus low protein diet. Statistical difference was calculated by t-test.

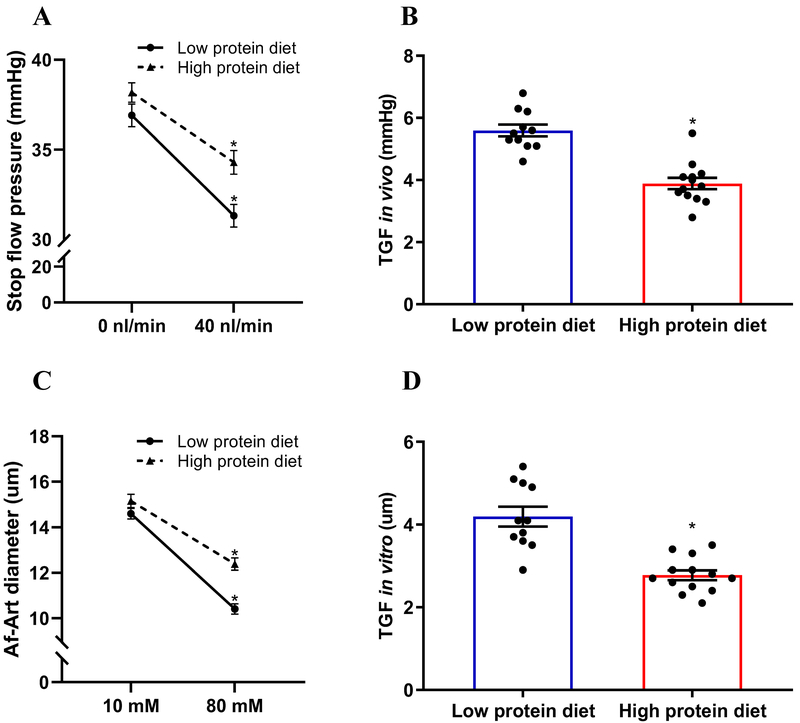

A high protein diet blunts TGF response in vivo and in vitro

To determine the effect of dietary protein on TGF response, TGF in vivo was measured by micropuncture. In low protein diet group, when tubular perfusion rate of ATF was increased from 0 to 40 nl/min, Psf decreased from 36.9±2.1 to 31.3±2.1 mmHg. TGF response indicated by ΔPsf, was 5.6±0.6 mmHg. In high protein diet group, the TGF response was inhibited to 3.8±0.6 mmHg (Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 2. High protein diet blunts TGF response in vivo and in vitro.

(A-B) TGF response in vivo was indicated by the ΔPsf when the tubular perfusion rate was increased from 0 to 40 nl/min. High protein diet inhibited TGF response in vivo compared with low protein diet; n=11-13 tubules/4-5 mice; *P<0.01 versus low protein diet. (C-D) TGF response in vitro was determined by the change of Af-Art diameter when switching the tubular perfusate from 10 to 80 mmol/L of NaCl. High protein diet inhibited TGF response in vitro compared with low protein diet; n=11-13; *P<0.01 versus low protein diet. Statistical difference was calculated by t-test.

TGF response in vitro was measured in isolated and double perfused JGAs. In low protein diet group, the Af-Art diameter decreased from 14.6±0.7 to 10.4±0.7 µm when NaCl concentration in tubular perfusate was increased from 10 to 80 mM. The TGF response indicated by the average change of Af-Art was 4.1±0.8 µm. In high protein diet group, TGF response was significantly decreased to 2.8±0.4 µm (Figure 2C and 2D). These data demonstrated that an increased protein intake blunts TGF response in vivo and in vitro.

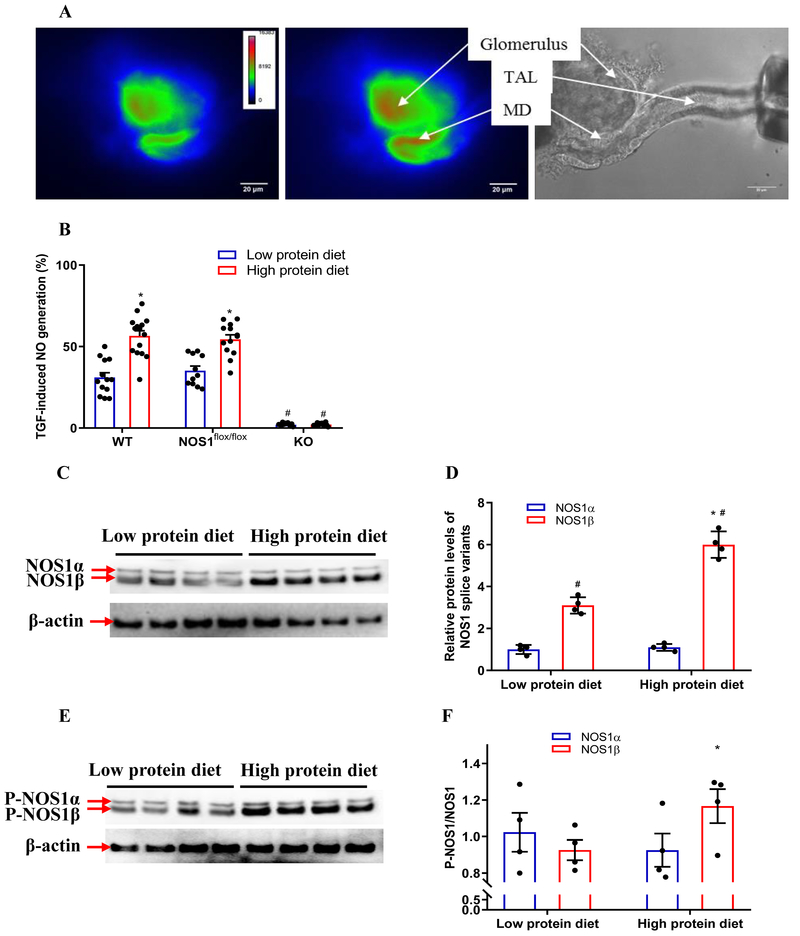

A high protein diet enhances NO generation in the macula densa

To determine the effect of dietary protein on NO generation in the macula densa, the TGF-induced NO generation was measured in isolated perfused JGAs loaded with DAF-2 DA (Figure 3A). In low protein diet group, the TGF-induced NO generation in the macula densa increased by 31±10.6 % from 108.4±8.1 to 141.5±7.7 units/min when NaCl concentration in tubular perfusate was increased from 10 to 80 mM. In high protein diet group, the TGF-induced NO generation in the macula densa increased by 56.5±12.3 % from 120.6±7.1 to 188.2±11.2 units/min, which was significantly greater than low protein diet group (Figure 3B). These data demonstrated that an increase in protein intake enhances NO generation in the macula densa.

Figure 3. High protein diet upregulates the expression and activity of NOS1β in the macula densa.

(A) The NO generation in the macula densa was measured in isolated perfused JGA with DAF-2 DA. The bright field image exhibited the anatomic structure of the perfused JGA. The florescent image of DAF-2 DA loaded JGA showed the NO generation in the macula densa. (B) The NO generation in the macula densa was higher in high protein diet group compared with low protein diet group in WT and NOS1flox/flox mice. The high protein diet had no effect on the macula densa NO generation in the KO mice; n=11-15; *P<0.01 versus low protein diet. (C-F) The protein levels of NOS1 splice variants and P-NOS1 splice variants in the renal cortex; n=4; *P<0.01 versus low protein diet. Statistical difference was calculated by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak multiple comparisons test.

A high protein diet increases macula densa NOS1β expression and phosphorylation at Ser 1417

To determine the effect of dietary protein on the expression and phosphorylation of NOS1 splice variants in the macula densa, the protein levels of NOS1 and P-NOS1 in the renal cortex, where most of the NOS1 comes from macula densa cells, were measured and compared between high protein diet and low protein diet groups. The high protein diet increased the protein level of NOS1β by 93.3±14.4% (Figure 3C and 3D) and the level of P-NOS1β/NOS1β by 25.8±12.9% (Figure 3E and 3F) in the renal cortex. The levels of NOS1α or P-NOS1α/NOS1α were not significantly different between high protein diet and low protein diet groups. These data demonstrated that a high protein diet increases macula densa NOS1β expression and phosphorylation at Ser 1417.

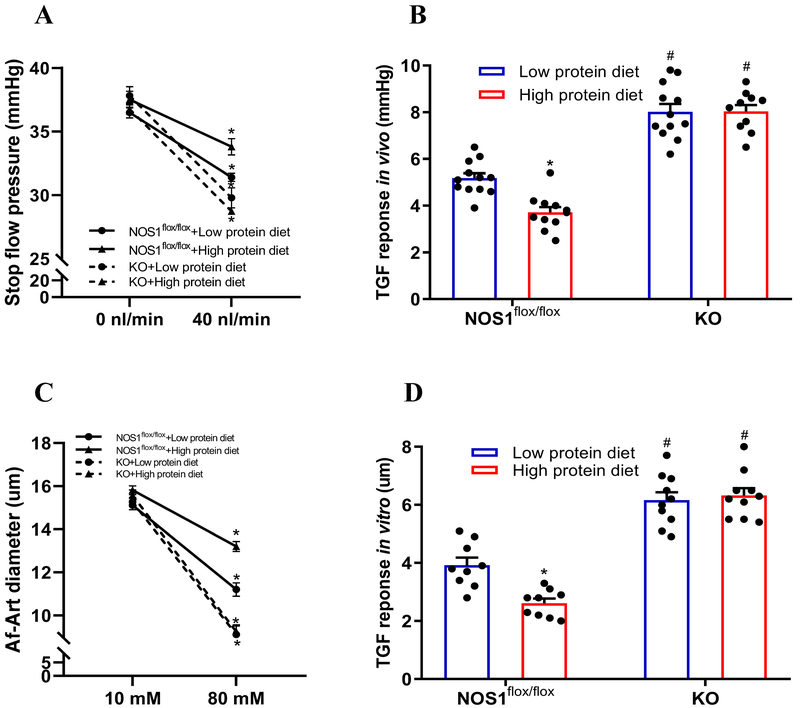

High protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration and kidney hypertrophy are dependent on macula densa NOS1β

To determine the significance of macula densa NOS1β in the high protein diet-induced hyperfiltration, we repeated the experiments above in KO and NOS1flox/flox mice. The phenotype of the NOS1flox/flox mice in response to a high protein diet was similar to the C57BL/6 mice. In the KO mice, the high protein diet had no effect on the TGF-induced NO generation at the macula densa (Figure 3B). The TGF in vitro (Figure 5C and 5D) or TGF in vivo (Figure 5A and 5B) was not significantly changed in the KO mice on high protein diet. Furthermore, the increases of GFR and RBF, as well as decrease of RVR in response to the high protein intake were largely attenuated in the KO mice compared with the NOS1flox/flox mice (Figure 4A, 4B and 4C). These results indicated that the high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration and kidney hypertrophy are dependent on TGF response mediated by macula densa NOS1β.

Figure 5. High protein diet-induced TGF inhibition is dependent on macula densa NOS1β.

(A and B) TGF response in vivo (n=10-12 tubules/3-5 mice) and (C and D) TGF response in vitro (n=9-10) were measured in KO mice and compared with NOS1flox/flox mice; *P<0.01 versus low protein diet; #P<0.01 versus NOS1flox/flox. Statistical difference was calculated by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak multiple comparisons test.

Figure 4. High protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration is dependent on macula densa NOS1β.

The effects of high protein diet on GFR (A), RBF (B) and RVR (C) were measured in KO mice and compared with NOS1flox/flox mice; n=8-13; *P<0.05 versus low protein diet; #P<0.05 versus NOS1flox/flox. Statistical difference was calculated by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak multiple comparisons test.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated the significance of macula densa NOS1β-mediated TGF mechanism in high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration. We found that a high protein diet enhances the expression and activity of NOS1β in the macula densa, which blunts TGF response and promotes the elevation in GFR.

It has long been known that diets rich in protein are associated with increases in GFR1,4,5 and RBF.20–22 Consistent with these previous findings, the current study showed that the high protein intake resulted in significant rises in GFR and RBF, as well as reduction in RVR in C57BL/6 mice. We also found that the animals fed a high protein diet had larger kidney size and greater kidney weight, while the body weight was similar without significant difference compared with the animals on the low protein diet. These results are consistent with the previous report that C57BL/6 mice exhibited heavier kidney but comparable gain in body weight following a 10 days high protein diet than low protein diet.13 In addition, neither total extracellular fluid volume nor systemic blood pressure were significantly altered in response to the high protein diet, as shown in the present study, as well as previous records.3,23 Although high protein diet did not significantly increase whole kidney GFR factored by kidney weight (Supplemental Table S1), our results are in agreement with a previous study by Seney et al.3 showing that high protein diet induced an increase in kidney weight by 38% and an increase in whole kidney GFR by 29% in Sprague-Dawley rats. They also found a 21% increase in distally measured single nephron GFR (with TGF), but no significant change in proximally measured single nephron GFR (without TGF), suggesting that high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration is dependent on the intact TGF system and the renal hypertrophy might be a compensatory response secondary to the glomerular hemodynamic changes. However, the single nephron GFR was not assessed in the present study.

TGF is an important intrinsic mechanism in control of renal hemodynamics. It describes a negative feedback between tubule and Af-Art where an increase in NaCl delivery to the macula densa promotes the release and formation of ATP and/or adenosine, which then constricts the Af-Art, thereby resulting in a tonic inhibition of single nephron GFR.24–27 The changes in TGF responsiveness may contribute to the increases in GFR, which is thought to occur in several physiological and pathophysiological conditions such as high salt intake, volume expansion, diabetes, unilateral nephrectomy and pregnancy.28–31 However, the significance of TGF mechanism in high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration is still controversial. Seney et al. reported that TGF response, as indicated by the proximal-distal difference in single nephron GFR, was about 50% less sensitive in the Sprague-Dawley rats on a high protein die than low protein diet;3,10 whereas Sallstrom et al. observed that a mouse model of adenosine A1 receptor knockout that is lack of TGF response, developed the glomerular hyperfiltration in a comparable degree as their wild type controls in response to a high protein intake.13 The discrepancy might attribute to the inappropriate approach to assess significance of TGF in Sallstrom’s study. Although adenosine A1 receptor knockout mice lack the TGF response,25,32 it should be noted that these animals are global knockout. Adenosine receptors are widely expressed in rodents,33–35 and even within the kidney, adenosine receptors are present not only in the Af-Art but also in glomeruli and many tubular segments.34,35 Therefore, confounding factors can complicate the assessment utilizing this model for evaluating the systemic significance of TGF system. Consistent with the findings in Seney et al.’s study, we found that both TGF in vivo and in vitro were significantly inhibited in the C57BL/6 mice fed the high protein diet compared with the animals fed the low protein diet, indicating that an increase in protein intake blunts TGF response.

NOS1 is abundantly expressed in the macula densa cells36,37 and NO generated by NOS1 at the macula densa is a key modulator of TGF response,36–39 which buffers or attenuates the vasoconstrictor TGF tone via a cGMP-dependent protein kinase pathway.40,41 Nevertheless, the effect of high protein diet on the NO generation in the macula densa remains unclear. In the present study, we found that an increased intake of protein significantly enhanced the TGF-induced NO production in the macula densa. Furthermore, our laboratory recently reported that mouse macula densa cells express both α and β splice variants of NOS1 protein and NOS1β is the primary splice variant and contributes to most of the NO generation by the macula densa.14,15 It has also been reported that NOS1 phosphorylated at Ser1417 by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) increased NOS activity,42–44 while phosphorylation at Ser847 by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM-K) reduced its activity.45,46 In the current study, C57BL/6 mice with the high protein intake exhibited increased protein level of NOS1β and stimulated phosphorylation of NOS1β at Ser1417 in the renal cortex, where most of the NOS1 comes from the macula densa cells. Therefore, the high protein diet-induced TGF inhibition, as well as glomerular hyperfiltration might be associated with the upregulated expression and activity of NOS1β in the macula densa.

The findings of the present study also confirm the results of a previous study by Sällström et al. using a global NOS1 knockout mouse model, in which a high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfitration is not different between the global NOS1 knockout and wild type mice.13 As we recently reported that this global NOS1 knockout mouse line is actually a NOS1α knockout with intact NOS1β.16 Therefore, the macula densa NO generation and TGF responsiveness are basically normal. However, this study13 did demonstrate that NOS1α in the other tissues, such as brain and heart, does not play a major role in the high protein intake-induced hyperfiltration. Moreover, our laboratory recently developed a macula densa-specific NOS1 knockout mouse model by crossing an NKCC2cre line with a NOS1flox/flox line, in which all splice variants of NOS1 were selectively deleted from macula densa cells.14 Therefore, in the present study, this KO model was utilized to determine the significance of macula densa NOS1 in the effects of high protein intake on NO production at the macula densa, TGF responsiveness, RBF and GFR. We found that the changes in phenotype following a high protein diet that were observed in wild type mice were largely attenuated in the KO mice, indicating that these alterations induced by the high protein intake are dependent on macula densa NOS1.

Although the macula densa NOS1β-mediated TGF mechanism plays a major role in the high protein-induced hyperfiltration, we are aware that knockout of macula densa NOS1 does not completely block the hemodynamic changes in response to high protein intake, suggesting other factors also contribute to the high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration. Many studies have shown the involvement of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in high protein intake-induced changes in renal hemodynamics. Both renal COX-2 and prostaglandin production increase with high protein diet while decrease with protein restriction.12,47–49 Moreover, inhibition of prostaglandin production by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.47,48,50,51 or even selective inhibition of COX-212 prevents the increase in GFR following high protein diet or amino acid infusion. High protein intake has also been found to enhance NaCl reabsorption in the proximal tubule, and thereby reduce luminal NaCl delivery to macula densa and diminish the TGF signal, contributing to glomerular hyperfiltration.3,10,50,52

PERSPECTIVES

This study indicates a novel mechanism of high protein diet–induced hyperfiltration wherein an increased intake of protein upregulates the expression of NOS1β and stimulates the phosphorylation of NOS1β at Ser1417 in the macula densa, which blunts the TGF response and promotes the rise in GFR. These findings establish a critical role of macula densa NOS1β-mediated TGF mechanism in high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is New?

Using a variety of sophisticated techniques and a novel macula densa-specific NOS1 knockout model, we identified a new mechanism of high protein diet–induced hyperfiltration that an increase in protein intake upregulates the expression and activity of NOS1β in the macula densa, which enhances the generation of nitric oxide and blunts the tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) response, thereby promoting glomerular hyperfiltration.

What Is Relevant?

A high protein intake induces glomerular hyperfiltration, which is associated with an increased long-term risk for renal damage. However, the mechanism for high protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration has not been fully elucidated.

Summary

High protein diet-induced glomerular hyperfiltration is dependent on macula densa NOS1β-mediated TGF mechanism.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by American Society of Nephrology Ben J. Lipps Research Fellowship Awards (to J.Z. and J.W.), an American Heart Association Career Development Award 18CDA34110441 (to L.W.), and the National Institutes of Health grants DK099276, HL142814, and HL137987 (to R.L.).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

Reference List

- 1.Bosch JP, Saccaggi A, Lauer A, Ronco C, Belledonne M, Glabman S. Renal functional reserve in humans. Effect of protein intake on glomerular filtration rate. Am J Med 1983; 75(6):943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tirosh A, Golan R, Harman-Boehm I, Henkin Y, Schwarzfuchs D, Rudich A, Kovsan J, Fiedler GM, Bluher M, Stumvoll M, Thiery J, Stampfer MJ, Shai I. Renal function following three distinct weight loss dietary strategies during 2 years of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(8):2225–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seney FD Jr., Wright FS. Dietary protein suppresses feedback control of glomerular filtration in rats. J Clin Invest 1985; 75(2):558–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connor WJ, Summerill RA. The effect of a meal of meat on glomerular filtration rate in dogs at normal urine flows. J Physiol 1976; 256(1):81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dicker SE. Effect of the protein content of the diet on the glomerular filtration rate of young and adult rats. J Physiol 1949; 108(2):197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Moore LW, Tortorici AR, Chou JA, St-Jules DE, Aoun A, Rojas-Bautista V, Tschida AK, Rhee CM, Shah AA, Crowley S, Vassalotti JA, Kovesdy CP. North American experience with Low protein diet for Non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 2016; 17(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenner BM, Lawler EV, Mackenzie HS. The hyperfiltration theory: a paradigm shift in nephrology. Kidney Int 1996; 49(6):1774–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lew QJ, Jafar TH, Koh HW, Jin A, Chow KY, Yuan JM, Koh WP. Red Meat Intake and Risk of ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28(1):304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin J, Fung TT, Hu FB, Curhan GC. Association of dietary patterns with albuminuria and kidney function decline in older white women: a subgroup analysis from the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 57(2):245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seney FD Jr., Persson EG, Wright FS. Modification of tubuloglomerular feedback signal by dietary protein. Am J Physiol 1987; 252(1 Pt 2):F83–F90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woods LL, DeYoung DR, Smith BE. Regulation of renal hemodynamics after protein feeding: effects of loop diuretics. Am J Physiol 1991; 261(5 Pt 2):F815–F823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao B, Xu J, Qi Z, Harris RC, Zhang MZ. Role of renal cortical cyclooxygenase-2 expression in hyperfiltration in rats with high-protein intake. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2006; 291(2):F368–F374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sallstrom J, Carlstrom M, Olerud J, Fredholm BB, Kouzmine M, Sandler S, Persson AE. High-protein-induced glomerular hyperfiltration is independent of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism and nitric oxide synthases. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2010; 299(5):R1263–R1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu Y, Wei J, Stec DE, Roman RJ, Ge Y, Cheng L, Liu EY, Zhang J, Hansen PB, Fan F, Juncos LA, Wang L, Pollock J, Huang PL, Fu Y, Wang S, Liu R. Macula Densa Nitric Oxide Synthase 1beta Protects against Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27(8):2346–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu D, Fu Y, Lopez-Ruiz A, Zhang R, Juncos R, Liu H, Manning RD Jr., Juncos LA, Liu R. Salt-sensitive splice variant of nNOS expressed in the macula densa cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2010; 298(6):F1465–F1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Chandrashekar K, Wang L, Lai EY, Wei J, Zhang G, Wang S, Zhang J, Juncos LA, Liu R. Inhibition of Nitric Oxide Synthase 1 Induces Salt-Sensitive Hypertension in Nitric Oxide Synthase 1alpha Knockout and Wild-Type Mice. Hypertension 2016; 67(4):792–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gyurko R, Leupen S, Huang PL. Deletion of exon 6 of the neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene in mice results in hypogonadism and infertility. Endocrinology 2002; 143(7):2767–2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tojo A, Gross SS, Zhang L, Tisher CC, Schmidt HH, Wilcox CS, Madsen KM. Immunocytochemical localization of distinct isoforms of nitric oxide synthase in the juxtaglomerular apparatus of normal rat kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 1994; 4(7):1438–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachmann S, Bosse HM, Mundel P. Topography of nitric oxide synthesis by localizing constitutive NO synthases in mammalian kidney. Am J Physiol 1995; 268(5 Pt 2):F885–F898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer TW, Anderson S, Brenner BM. Dietary protein intake and progressive glomerular sclerosis: the role of capillary hypertension and hyperperfusion in the progression of renal disease. Ann Intern Med 1983; 98(5 Pt 2):832–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singer MA. Dietary protein-induced changes in excretory function: a general animal design feature. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 2003; 136(4):785–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabinowitz L, Gunther RA, Shoji ES, Freedland RA, Avery EH. Effects of high and low protein diets on sheep renal function and metabolism. Kidney Int 1973; 4(3):188–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ichikawa I, Purkerson ML, Klahr S, Troy JL, Martinez-Maldonado M, Brenner BM. Mechanism of reduced glomerular filtration rate in chronic malnutrition. J Clin Invest 1980; 65(5):982–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomson S, Bao D, Deng A, Vallon V. Adenosine formed by 5’-nucleotidase mediates tubuloglomerular feedback. J Clin Invest 2000; 106(2):289–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun D, Samuelson LC, Yang T, Huang Y, Paliege A, Saunders T, Briggs J, Schnermann J. Mediation of tubuloglomerular feedback by adenosine: evidence from mice lacking adenosine 1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001; 98(17):9983–9988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren Y, Arima S, Carretero OA, Ito S. Possible role of adenosine in macula densa control of glomerular hemodynamics. Kidney Int 2002; 61(1):169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren Y, Garvin JL, Liu R, Carretero OA. Role of macula densa adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in tubuloglomerular feedback. Kidney Int 2004; 66(4):1479–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomson SC, Blantz RC, Vallon V. Increased tubular flow induces resetting of tubuloglomerular feedback in euvolemic rats. Am J Physiol 1996; 270(3 Pt 2):F461–F468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schnermann J Juxtaglomerular cell complex in the regulation of renal salt excretion. Am J Physiol 1998; 274(2 Pt 2):R263–R279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaufman JS, Hamburger RJ, Flamenbaum W. Tubuloglomerular feedback: effect of dietary NaCl intake. Am J Physiol 1976; 231(6):1744–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baylis C, Blantz RC. Tubuloglomerular feedback activity in virgin and 12-day-pregnant rats. Am J Physiol 1985; 249(1 Pt 2):F169–F173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown R, Ollerstam A, Johansson B, Skott O, Gebre-Medhin S, Fredholm B, Persson AE. Abolished tubuloglomerular feedback and increased plasma renin in adenosine A1 receptor-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2001; 281(5):R1362–R1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adenosine Schrader J.. A homeostatic metabolite in cardiac energy metabolism. Circulation 1990; 81(1):389–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallon V, Muhlbauer B, Osswald H. Adenosine and kidney function. Physiol Rev 2006; 86(3):901–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welch WJ. Adenosine, type 1 receptors: role in proximal tubule Na+ reabsorption. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015; 213(1):242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilcox CS, Welch WJ, Murad F, Gross SS, Taylor G, Levi R, Schmidt HH. Nitric oxide synthase in macula densa regulates glomerular capillary pressure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992; 89(24):11993–11997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mundel P, Bachmann S, Bader M, Fischer A, Kummer W, Mayer B, Kriz W. Expression of nitric oxide synthase in kidney macula densa cells. Kidney Int 1992; 42(4):1017–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu R, Ren Y, Garvin JL, Carretero OA. Superoxide enhances tubuloglomerular feedback by constricting the afferent arteriole. Kidney Int 2004; 66(1):268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Role of nitric oxide in tubuloglomerular feedback: effects of dietary salt. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1997; 24(8):582–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren YL, Garvin JL, Carretero OA. Role of macula densa nitric oxide and cGMP in the regulation of tubuloglomerular feedback. Kidney Int 2000; 58(5):2053–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kovacs G, Komlosi P, Fuson A, Peti-Peterdi J, Rosivall L, Bell PD. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase: its role and regulation in macula densa cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14(10):2475–2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bredt DS, Ferris CD, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide synthase regulatory sites. Phosphorylation by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, protein kinase C, and calcium/calmodulin protein kinase; identification of flavin and calmodulin binding sites. J Biol Chem 1992; 267(16):10976–10981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adak S, Santolini J, Tikunova S, Wang Q, Johnson JD, Stuehr DJ. Neuronal nitric-oxide synthase mutant (Ser-1412 --> Asp) demonstrates surprising connections between heme reduction, NO complex formation, and catalysis. J Biol Chem 2001; 276(2):1244–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hurt KJ, Sezen SF, Lagoda GF, Musicki B, Rameau GA, Snyder SH, Burnett AL. Cyclic AMP-dependent phosphorylation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase mediates penile erection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109(41):16624–16629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayashi Y, Nishio M, Naito Y, Yokokura H, Nimura Y, Hidaka H, Watanabe Y. Regulation of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by calmodulin kinases. J Biol Chem 1999; 274(29):20597–20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Komeima K, Hayashi Y, Naito Y, Watanabe Y. Inhibition of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIalpha through Ser847 phosphorylation in NG108–15 neuronal cells. J Biol Chem 2000; 275(36):28139–28143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levine MM, Kirschenbaum MA, Chaudhari A, Wong MW, Bricker NS. Effect of protein on glomerular filtration rate and prostanoid synthesis in normal and uremic rats. Am J Physiol 1986; 251(4 Pt 2):F635–F641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vanrenterghem YF, Verberckmoes RK, Roels LM, Michielsen PJ. Role of prostaglandins in protein-induced glomerular hyperfiltration in normal humans. Am J Physiol 1988; 254(4 Pt 2):F463–F469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Daniels BS, Hostetter TH. Effects of dietary protein intake on vasoactive hormones. Am J Physiol 1990; 258(5 Pt 2):R1095–R1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woods LL. Mechanisms of renal hemodynamic regulation in response to protein feeding. Kidney Int 1993; 44(4):659–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirschberg RR, Zipser RD, Slomowitz LA, Kopple JD. Glucagon and prostaglandins are mediators of amino acid-induced rise in renal hemodynamics. Kidney Int 1988; 33(6):1147–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woods LL, Smith BE, De Young DR. Regulation of renal hemodynamics after protein feeding: effects of proximal and distal diuretics. Am J Physiol 1993; 264(2 Pt 2):R337–R344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.