Abstract

We describe the use of red blood cells (RBCs) as carriers of cytoplasmically interned phototherapeutic agents. Photolysis promotes drug release from the RBC carrier thereby providing the means to target specific diseased sites. This strategy is realized with a vitamin B12-taxane conjugate (B12-TAX), in which the drug is linked to the vitamin via a photolabile Co-C bond. The conjugate is introduced into mouse RBCs (mRBCs) via a pore-forming/pore-resealing procedure and is cytoplasmically retained due to the membrane impermeability of B12. Photolysis separates the taxane from the B12 cytoplasmic anchor, enabling the drug to exit the RBC carrier. A covalently appended Cy5 antenna sensitizes the conjugate (Cy5-B12-TAX) to far red light, thereby circumventing the intense light absorbing properties of hemoglobin (350 – 600 nm). Microscopy and imaging flow cytometry revealed that Cy5-B12-TAX-loaded mRBCs act as drug carriers. Furthermore, intravital imaging of mice furnished a real time assessment of circulating phototherapeutic-loaded mRBCs as well as evidence of the targeted photorelease of the taxane upon photolysis. Histopathology confirmed that drug release occurs in a well resolved spatiotemporal fashion. Finally, we employed acoustic angiography to assess the consequences of taxane release at the tumor site in Nu/Nu-tumor-bearing mice.

Keywords: vitamin B12, drug delivery, photolysis, prodrugs, red blood cells

1. Introduction

Chemotherapeutics are an essential component of the therapeutic arsenal employed to treat solid and liquid tumors. However, chemotherapeutic potential is most often limited by systemic toxicity caused by off target side effects.[1–3] Consequently, drug platforms that locally deliver efficacious therapeutic agents to diseased sites, while sparing healthy tissue, are highly sought after.[4–6] For example, antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) bind to cancer-specific antigens on tumor cells and the subsequent release of the covalently bound drug induces cell death. However, uneven distribution at the tumor site impedes therapeutic efficacy.[7] In addition, the low drug payload of ADCs, combined with relatively few copies of the cancer antigen on the cell surface, limits the number of drug molecules that can be delivered to the diseased site.[8–10] Nanoparticles offer attractive properties as alternative drug delivery vehicles. Considerable attention has been given to enhancing nanoparticle circulation time as well as developing drug release mechanisms that can deliver the therapeutic to the diseased site with enhanced selectivity. For example, external triggers, including light, have been used to elicit drug discharge in a spatially-selective fashion.[11] Indeed, given the ability to modulate light spatially, temporally, by intensity, and by wavelength, it is not surprising that a wide variety of light responsive agents, including drugs and proteins, have been reported.[12–14] Nonetheless, the development of long-lived, widely distributed phototherapeutic agents that respond to tissue-penetrating wavelengths remains a sought-after goal. The primary objective of this study is to assess the light-triggered, site-specific, release of a therapeutic agent from carriers with a long circulation lifetime, namely red blood cells (RBCs).

We have tackled the challenges associated with targeted drug delivery using a finely tuned long wavelength-responsive fluorophore-vitamin B12 (B12) conjugate that acts as a scaffold for the light-sensitive release of appended therapeutic agents. This conjugate has the potential to release a wide array of small molecule drugs with spatial and temporal precision. In addition, modification of the B12 framework with red and far-red fluorophores extends the platform’s ability to collect light into the optical window of tissue (600 – 900 nm).[15] We have enhanced the bioavailability and circulation of the B12-drug conjugates by sequestering these agents into RBC carriers. RBCs are biocompatible, circulate for up to 4 months, and have a large payload capacity, thus making them attractive drug transporters.[16–18] In this study, we report the encapsulation of a B12-based phototherapeutic into murine RBCs (mRBCs) using a modified dialysis loading procedure[16, 19, 20] and demonstrate the spatially-targeted photo-triggered release of a taxane derivative (Figure 1) in two animal models. Taxanes are medicinally useful anti-mitotic chemotherapeutics used to treat various solid tumors including breast, gastric, prostate, and non-small cell lung cancers, but are known to elicit a plethora undesired off target short- and long-term side effects in a large fraction (>30%) of patients.[21, 22]

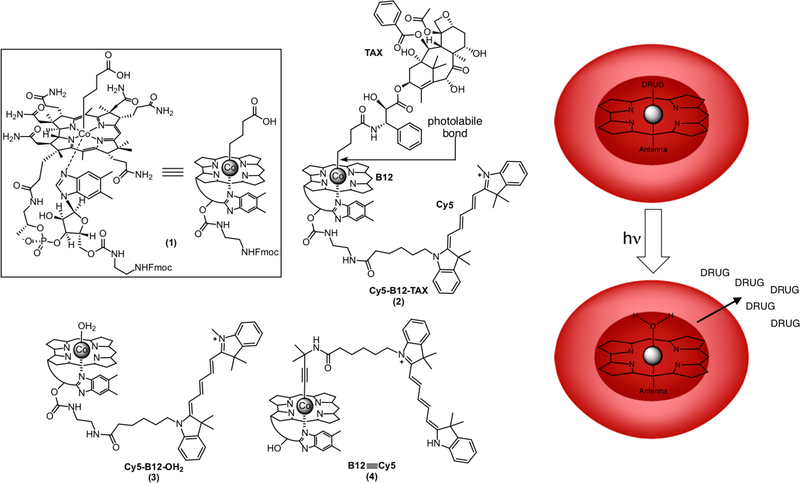

Figure 1.

Structures of the B12 derivatives 1 – 4 employed in this study. Compound 1, which is highlighted in the box, is shown as the full structure on the left and corresponding schematic form on the right. The photolabile Co-C bond is highlighted in 2, which was prepared from compound 1 in three steps (Supporting Information). The Cy5-B12-TAX 2 derivative is comprised of a photo-releasable taxane, the corrin ring of B12, and a Cy5 “antenna” that enables 2 to capture long wavelength photons (650 ± 25 nm). Derivative 3 is the side-product of the photolysis of 2. Compound 4 contains a Co≡C triple bond that is photostable, enabling this species to be visualized without concomitant photolysis. B12 and its conjugates are membrane impermeable. Installation of B12 derivatives into RBCs via pore-forming hypotonic conditions and subsequent resealing traps the B12-drug conjugates inside these cell-based drug carriers. Illumination releases the drug from its cytosolic B12-anchor.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Design and Synthesis of Phototherapeutics

The photoresponsive TAX species 2 is comprised of (1) a Cy5 fluorophore (650 nm excitation wavelength) appended to the ribose 5’-OH of (2) B12. A (3) TAX derivative is attached to the CoIII metal of the corrin ring system via a photolabile Co-C bond (Figure 1). The Cy5-B12-TAX conjugate 2 was prepared from a chemically modified derivative of B12 (1).[23] In brief, the three-step procedure includes condensation of N-Deboc docetaxel with the free carboxylate of 1, removal of the Fmoc protecting group, and a final condensation of the exposed amine with the N-hydroxysuccinimide activated form of Cy5 (Scheme S1, Figure S1, Supporting Information).[24] Alkyl-cobalamins are photolyzed only at the wavelengths absorbed by the corrin ring (330 – 575 nm). Consequently, they are photochemically inert to wavelengths longer than 600 nm. The appended Cy5 serves as an antenna that captures long wavelengths not absorbed by the corrin ring (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Since both TAX and Cy5 can be readily replaced with other drugs or fluorophores, respectively, B12-based phototherapeutics potentially can be used to convey and release a wide variety of drugs at selected wavelengths residing within the optical window of tissue (650 – 900 nm).

2.2. Assembly and Characterization of mRBCs Loaded with Phototherapeutics

The systemic lifetime of chemotherapeutics is typically on the scale of hours to days due to the robust nature of xenobiotic metabolism and/or rapid drug uptake by tissues. RBC carriers have the potential to extend the drug circulation lifespan of drugs from hours to weeks or even months.[16–18] In this regard, RBCs have been examined as transporters for anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antiinfectious agents. These blood-borne, cell-based carriers are ideal vehicles for long-term systemic release of therapeutics. More recently, stimuli-responsive (ultrasound, pH, magnetic, etc.) erythrocytes have been reported that offer the means to deliver drugs to diseased sites. Light, as a drug delivery stimulus, has received a great deal of attention due to three useful properties: high spatiotemporal resolution, wavelength-specific transmission, and ready modulation of photon flux.[12, 13] In this regard, we have developed an RBC-mediated, light-responsive, drug delivery technology by taking advantage of a unique property of the B12-drug conjugates: B12 and its corresponding conjugates are membrane impermeable. However, upon photolysis, the liberated drug is rendered membrane permeable and readily exits the RBC carrier. Loading of membrane impermeable phototherapeutics into the RBC interior is accomplished by incubating RBCs with Cy5-B12-TAX 2 or the control conjugate Cy5-B12-OH2 3 (Scheme S2; Figure S3, Supporting Information). The mixtures were dialyzed against hypotonic PBS containing 6 mm glucose. Low salt conditions promote entry of water into the RBCs, inducing the cells to swell, which generates pores in the membrane through which B12 conjugates can enter. Following dialysis, the pores are resealed in isotonic PBS, trapping membrane impermeable B12-based conjugates within the RBC interior. Widefield microscopy images indicate successful loading and normal morphology of loaded mRBCs (Figure 2a and Figure S3, Supporting Information). This procedure produces a final intracellular concentration of 39 ± 4 μm Cy5-B12-TAX 2 with a cell recovery of 53 ± 6%. The control B12 derivative, Cy5-B12-OH2 3 is loaded at a concentration of 32 ± 2 μm Cy5-B12-OH2, with a cell recovery of 63 ± 4%. RBCs were counted via a standard hemocytometer procedure to obtain cell recovery values before being lysed with ethanol to determine the concentrations of internal contents. (Figure 2b; Figure S4–S5, Supporting Information).

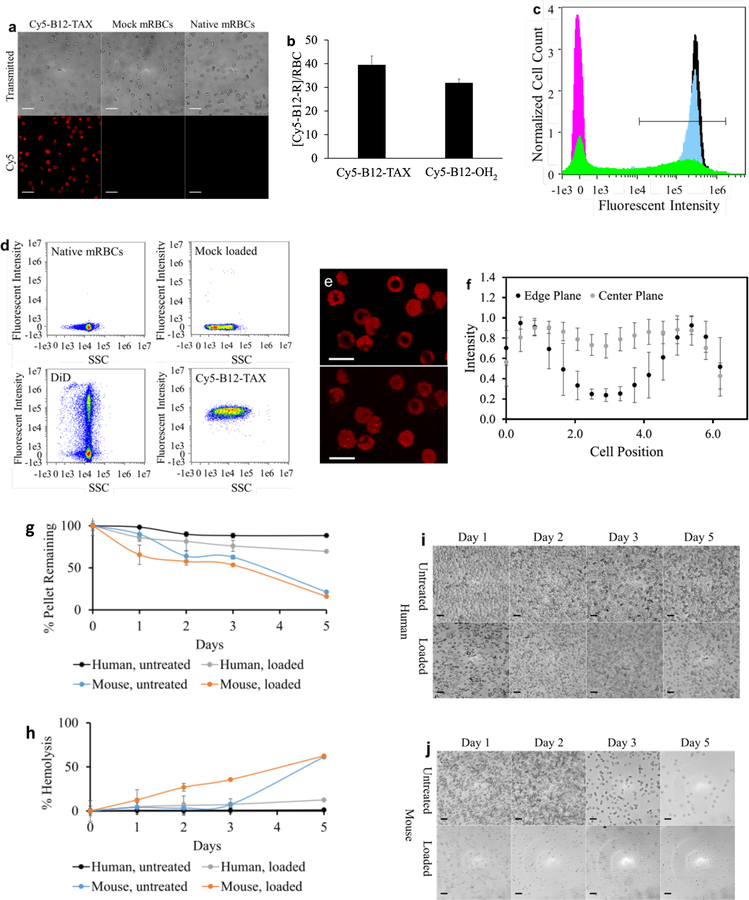

Figure 2.

Characterization of loaded mRBCs. a) Transmitted (top) and fluorescent (bottom) images of internally loaded and native mRBCs. Scale bar = 20 μm. b) Concentrations of Cy5-B12-TAX 2 (39 ± 4 μM) and Cy5-B12-OH2 3 (32 ± 2 μM) loaded into mRBCs. c) Flow cytometry histograms of internally and surface loaded mRBCs. Measurements of native mRBCs (magenta), DiD mRBCs (green), Cy5-B12-TAX mRBCs 2 (black), and Cy5-B12-OH2 mRBCs 3 (blue), reveal that internally loaded Cy5-B12-TAX and Cy5-B12-OH2 load homogenously with an efficiency of 99.4% and 99.7%, respectively. DiD loading is heterogeneous with an efficiency of 49.3%. Cells with a fluorescent intensity of at least 1×104 (defined by the straight-line region of interest) are considered loaded. Normalized cell count takes into account differences in the number of cells measured. d) Plots of Cy5 intensity versus side scattering (SSC) reveal variability of internal complexity by mRBCs exposed to hypotonic loading. e) Fluorescent confocal microscopy taken as a Z stack through mRBCs loaded with Cy5-B12-TAX. The top and bottom images are from different planes of the same cells, revealing different fluorescent patterns due to the biconcave shape of RBCs. Scale bar = 6 μm. f) Quantification across straight-line regions of interest in 15 representative cells confirm loading in the RBC internal cavity. mRBCs are more fragile than their human counterparts over time as evidenced by g) size of the centrifuged pellet, h) percentage of hemolysis, and i-j) density of cells by microscopy. Scale bar = 20 μm.

The mRBCs loaded with Cy5-B12-TAX 2, Cy5-B12-OH2 3, or the membrane labeling dye, 1,1-dioctadecyl-3,3,3,3-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine (DiD) were characterized using imaging flow cytometry. Results are provided as histograms of in-focus singlets (Figure 2c). Cells that display a fluorescent intensity value over 1 × 104 (linear region of interest) are considered to be loaded. Using this threshold, 99.4% and 99.7% of the Cy5-B12-TAX 2 and Cy5-B12-OH2 3 exposed cells contain the B12-conjugate, respectively. Narrow distributions indicate that internally loaded mRBCs display uniform concentrations of B12 conjugates. In contrast, the widened histogram of cells externally decorated with DiD indicates a heterogeneous dispersal of the fluorophore amongst the RBC population. Furthermore, loading efficiency is a more modest 49.2%. Flow cytometry side scattering (SSC) is related to the complexity of structures in the cell interior and surface shape.[25] Figure 2d and Figure S6 (Supporting Information) reveal that side scattering variability is more significant in cells subjected to the internal loading procedure, suggesting a less consistent internal composition. Since at least 90% of RBC internal composition is hemoglobin[26, 27] and since this component is visibly exchanged with the environment during the internal loading procedure, we suspect that that heterogeneous loss of this protein may be related to the observed side scattering effect. Slight alterations in surface shape due to membrane disruption in some cells after the loading procedure may also play a role.[28] By contrast, mRBCs surface decorated with DiD exhibit a narrow side scattering pattern that more closely resembles native mRBCs. These experiments indicate that while surface loading may preserve the internal characteristics of mRBCs to a greater degree, internal loading has the potential to pack material with a more uniform composition per RBC. Flow cytometry reveals that DiD is retained on the membrane, whereas the B12 conjugates are loaded in the cell interior (Figure 2e). Due to the imaging modality associated with widefield microscopy and flow cytometry imaging, internally loaded cells occasionally appear to be only membrane loaded due to apparent fluorescent differences between the edge and the center created by the RBC’s biconcave shape. Validation that mRBCs entrap Cy5-B12-TAX 2 in the cell interior is demonstrated by confocal microscopy (Figure 2f–g), in which both the center and edge planes are considered.

Loaded mRBCs retain fluorescent conjugates for at least 5 h in vitro, the length of time for the reported in vivo experiments. We do note that loaded mRBCs display lower stability and membrane integrity than native mRBCs when stored in vitro for 24 h (Figure S7, Supporting Information). However, this behavior in mouse cells is likely irrelevant to their human counterparts. As previously reported and as demonstrated (Figure 2 h–k), mRBCs are significantly more fragile and susceptible to lysis than their human counterparts ex vivo both during processing[29] and when exposed to an environment that mimics in vivo conditions.[30] This fragility suggests that preclinical work with resealed mRBCs should be conducted within hours of loading in order to obtain the most relevant physiological results. By contrast, internally loaded human RBCs exhibit a lifetime and hardiness similar to their native states, as has been observed in human clinical trials.[16] We found that photolysis of Cy5-B12-TAX 2 loaded in RBCs results in the release of 98% of the total TAX payload (Figure S8). As expected, we were unable to detect any measurable TAX release when loaded RBCs were incubated in the dark. In addition, light-triggered TAX release from RBCs promotes microtubule polymerization in co-plated HeLa cells, which is consistent with the mechanism of action of taxanes, including docetaxel (Figure S9a–d). Consistent with the latter observation is our finding that only illuminated Cy5-B12-TAX loaded RBCs are cytotoxic to HeLa cells (Figure S9e).

2.3. Intravital Imaging of Fluorescent mRBCs

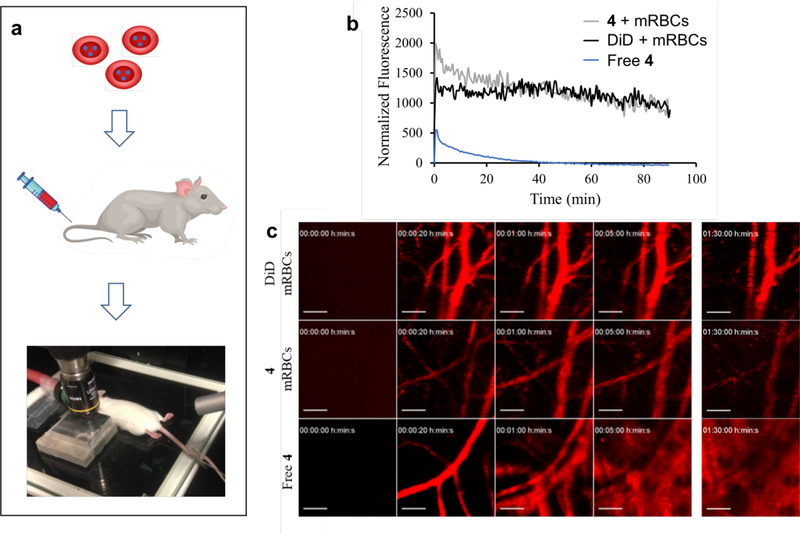

The circulation and cytotoxicity of TAX released within a well-defined region of the vasculature were evaluated in healthy FVB mice. Intravital imaging (Figure 3a) was used to assess whether loaded mRBCs maintain their cargo during circulation, by monitoring cells internally loaded with non-photocleavable B12≡Cy5 4[31, 32] (Scheme S3; Figures S10 – S11, Supporting Information) or externally loaded with DiD. Non-photocleavable models were necessary since the Cy5 excitation wavelength (633 nm) cleaves the otherwise photo-sensitive Co-C bond in Cy5-B12 derivatives. For each experiment, one ear was secured under the onboard microscope laser while the second ear was not exposed to laser illumination. A 633 nm laser at 30% laser power illuminated a roughly 0.5 mm diameter region every 5 s for a total of 90 min. The fluorescence associated with surface loaded DiD is fairly consistent, retaining 69 ± 2% of its fluorescence over 90 min. By contrast, the fluorescence of internally loaded photostable B12≡Cy5 is initially cleared more rapidly, but still maintains 53 ± 5% of its fluorescence after 90 min (Figure 3b–c). The initial rapid clearance of a subpopulation of the photostable B12≡Cy5 loaded mRBCs could be due to damage inflicted to some of the cells during the hypotonic loading procedure, which may structurally weaken the relatively fragile murine RBCs. As noted above, mice may be ideal candidates for preclinical investigation, but mRBCs are less than ideal models for circulation studies given their frailty relative to the more robust human cells. To validate that mRBC carriers extend B12 circulation, B12≡Cy5 was directly injected into the bloodstream in the absence of mRBC carriers. Within 1 min, the fluorescent conjugate was observed to extravasate from blood vessels and by 5 min, B12≡Cy5 had disseminated into the surrounding tissue (Figure 3b–c).

Figure 3.

Imaging of loaded mRBCs via intravital imaging. a) Imaging of the vasculature of the ear of an FVB mouse. Fluorescently labeled mRBCs were tail vein injected at 75 – 90% hematocrit and the blood vessels observed under a 10X objective using a 633 nm laser. b) Quantification of circulating labelled mRBCs. mRBCs loaded with DiD remain in circulation with a slope of −6 after the first 20 min and 76% of the initial fluorescence remaining after 90 min. Intensity of B12≡Cy5 4 loaded mRBCs likewise initially drops during the first 20 min, with a slope of −21. The fluorescence intensity remains stable (47% of the initial fluorescence) from 20 min to 90 min post-injection. By contrast, the free B12≡Cy5 4 conjugate is quickly and continuously cleared from vasculature and disseminated into the tissue. Plots are an average of six blood vessels measured across each mouse. c) Intravital imaging of DiD and B12≡Cy5 4 loaded mRBCs and free B12≡Cy5. Scale bar = 100 μm.

2.4. Intravital Imaging of Light-triggered Site-specific Release of TAX from mRBCs

TAX (as well as other taxane derivatives) is a cytotoxic agent and endothelial cells, which line blood vessels, are especially susceptible to taxane cytotoxicity at sub-clinical concentrations.[33–36] We note that the taxanes are extremely lipophilic and primarily serum-protein bound in circulation.[37] Consequently, under conventional in vivo conditions, RBCs do not play a meaningful role in assisting with transport.[38] However, a few erythrocyte-derived taxane delivery systems have been reported, but these are almost exclusively nanoparticle-based carriers coated with RBC membranes.[39–44] The sole exception is an in vitro study describing the hypotonic loading of paclitaxel formulated with Cremophor EL into intact RBCs.[45] However, to the best of our knowledge, the latter has not been applied to either cell or animal models. Our strategy employs intact RBCs that release TAX upon photo-stimulation. Cy5-B12-TAX loaded mRBCs were administered to FVB mice at a dosage of 100 μL containing ~8 × 107 mRBCs. A small region of one ear was illuminated immediately after injection as described above. The excitation laser (633 nm) on the intravital imaging microscope both activates and visualizes photosensitive therapeutics. Extensive extravasation of Cy5 fluorescence overtakes the imaging frame within 90 min, signifying release of loaded fluorescent material (Figure 4a). Fluorescent extravasation is not observed with either DiD or B12≡Cy5 loaded mRBCs (Figure 3c). There are several possible explanations for the extravasation of fluorescence. First, blood vessel integrity is known to be compromised by taxanes and therefore it is possible that microhemorragic events have occurred as a consequence of TAX photo-release. However, we do not observe any significant tissue infiltration by RBCs via histopathology (vide infra). Second, the observed spread of fluorescence into the surrounding tissue may be a consequence of light-triggered mRBC rupture induced by taxane release, resulting in the discharge of the Cy5-B12-OH2 photo-byproduct. However, illumination of Cy5-B12-TAX loaded mRBCs in vitro does not lead to the release of fluorescent material, consistent with the notion that the mRBCs are intact following drug release (Figure S12, Supporting Information). Third, light triggered release of TAX could damage the endothelial layer, resulting in hemolysis of circulating RBCs. Release of the Cy5-B12-TAX/Cy5-B12-OH2 could then extravasate into the surrounding tissue. Damage to the endothelium is known to activate the coagulation cascade,[46] resulting in vessel congestion (packed RBCs), the deposition of fibrin particles and subsequent rupture of RBCs as they circumnavigate the impaired vessel.[47] Indeed, these events are observed in a variety of medical conditions (microangiopathic hemolytic anemias)[47–49] and with various agents (venoms and drugs),[33, 46] including taxol[50].

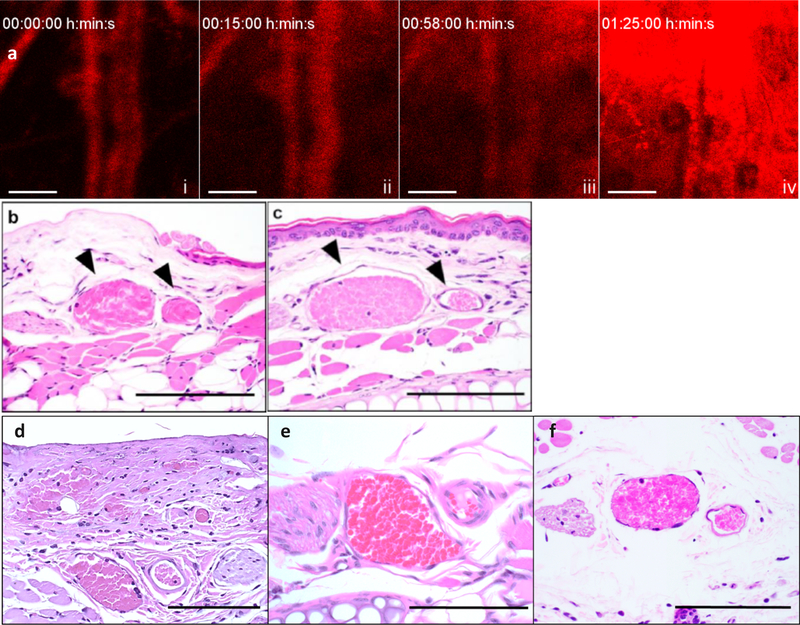

Figure 4.

Light-directed physiological effect of photoreleased taxane derivative from B12 scaffold. a) Representative time lapse of the extraversion of Cy5-B12-TAX 2 when circulating mRBC carriers are illuminated with a 633 nm laser. Over time, fluorescence originally encapsulated in the RBCs is seen to escape from the vasculature and spread into the surrounding tissue. i) 0 min, immediately after injection. ii) 15 min, fluorescence extravasation can begin to be seen in the upper right corner. iii) 58 min, more fluorescence in the upper right corner is observed iv) 85 min, large fluorescence accumulation at the illumination site. Scale bars = 100 μm. (b) Representative H&E-stained image of blood vessels and surrounding tissue after light treatment. Black arrows indicate vessels of interest which include the paired vein (left) and artery (right). The illuminated ear was treated with a 633 nm laser in 5 s pulses for 1.5 h while c) the non-illuminated ear was kept in the dark. Endothelial vascular congestion, a sign of endothelial disturbance, is only observed in the illuminated ear. d) A drop of free docetaxel (20 μM) in DMSO was placed on a mouse ear. The observed vessel morphology is analogous to that in the illuminated ear (2b). e) Blood vessels in untreated mouse ear. f) Blood vessels in mouse injected with Cy5-B12-OH2 3 loaded mRBCs and imaged under an IV 100 microscope. n = 3. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Following intravital imaging, mice were euthanized and the ears harvested. The ears were immediately fixed, subsequently embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained images reveal that the blood vessels in the light-treated ear (Figure 4b) are filled with abundant, packed red blood cells (congestion), which is consistent with damage to the endothelium.[51] The vasculature of the light-exposed area is extremely distended, with the lumina surrounded by an out-stretched layer of endothelial cells. In contrast, the non-illuminated ear (Figure 4c) displays no venous congestion, and the lumen contains a moderate number of RBCs with free space between cells. The same histological indications of vascular damage are observed when free docetaxel (2 mM) (Figure 4d) is topically administered to the ear vasculature. Damage is absent in untreated mouse ears (Figure 4e; Figure S13, Supporting Information). Finally, little to no histological damage is observed when Cy5-B12-OH2 loaded mRBCs were injected into mice and photo-illuminated during intravital imaging. It should be noted that with Cy5-B12-OH2-loaded mRBCs, no significant extravasation is observed under microscopy as was seen with Cy5-B12-TAX. We do detect a very slight disturbance in microvasculature (Figure S14, Supporting Information), which may be due to the photosensitizing effects of Cy5.[52] However, no endothelial damage is observed in histological slicing in mice injected with Cy5-B12-OH2-loaded RBCs under intravital imaging conditions (Figure 4f; Figure S14, Supporting Information). In short, illumination of mRBCs conveying Cy5-B12-OH2 has little or no effect on the integrity of the vasculature relative to that of mRBCs transporting Cy5-B12-TAX. Finally, we note that the maximum tolerated dose of docetaxel injected intravenously to mice is ~250 μg/mouse (10 mg kg−1).[53] Typical dosage for treatment in mice is anywhere between 75 μg/mouse for low dosage[44] up to the experimental maximum tolerated dose for high dosage.[45,46] In contrast, the sum total TAX content in the transfused mRBCs is only 1 μg/mouse. RBC-mediated circulation of Cy5-B12-TAX ensures the widespread dispersal of sequestered, and therefore inactive, TAX. The release of a high payload at the target site appears to account for its biological effect.

2.5. Visualization of the Impact of Light-triggered Site-specific TAX Delivery on the Tumor Vasculature

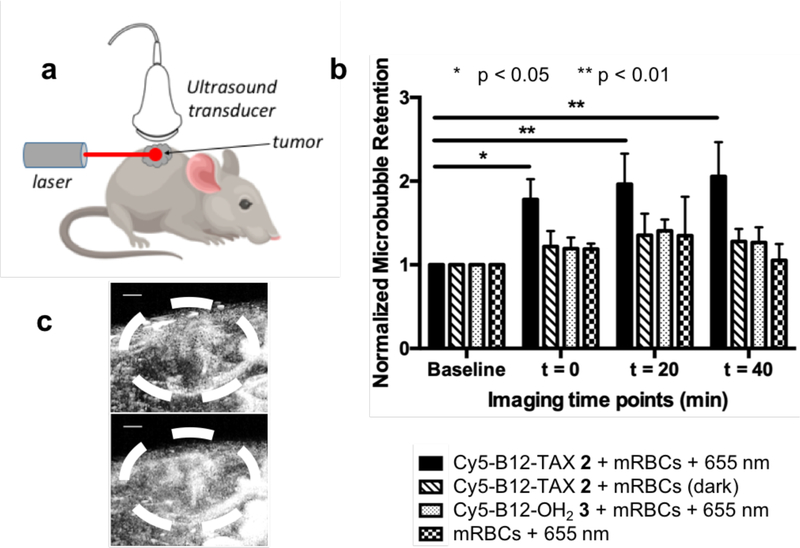

We also explored the local effect of released TAX on blood vessel integrity using Cy5-B12-TAX loaded mRBCs injected into immunodeficient Nu/Nu mice bearing the highly aggressive SVR angiosarcoma.[54] The tumor microenvironment and surrounding vasculature were visualized with acoustic angiography, using microbubbles as contrast agents (Figure 5a).[55, 56] After injection of the Cy5-B12-TAX-containing mRBCs, TAX was released at the tumor site by spatial illumination of the diseased tissue with a 100 mW, 655 nm laser for 5 min. Acoustic angiography was performed prior to injection (baseline), immediately after injection, and at 20 and 40 min post-injection time points (Figure 5 and Figure S15, Supporting Information). Microbubble retention was quantified by taking the ratio of the sum of microbubble coverage within the tumor volume over the sum of the total tumor area for the entire 3D volume. Results obtained with Cy5-B12-TAX loaded mRBCs and light treatment reveal microbubble tumor-retention values (calculated as the amount of contrast agent in a region) more than double the initial baseline 40 min after light treatment (Figure 5b–c). By contrast, mice treated with a variety of controls, including mRBCs containing Cy5-B12-TAX in the dark, mRBCs containing Cy5-B12-OH2 and light, or mock-loaded mRBCs and light, do not display any significant infiltration of microbubbles into tumor sites. In short, the increase in contrast agent pooling in the tumor upon treatment with mRBCs/Cy5-B12-TAX and light is consistent with the notion that that integrity of the illuminated blood vessels has been compromised in a TAX- and light-dependent fashion. These results correlate well with the intravital imaging studies, in which extravasation begins to be observed within 15 min and intensifies by 60 min (Figure 4a). Contrast agent accumulation at the tumor site was not observed with mock loaded mRBCs, Cy5-B12-OH2 loaded mRBCs with light treatment, or Cy5-B12-TAX in the dark. These controls confirm that the combined action of light and Cy5-B12-TAX are responsible for contrast agent accumulation in the tumor.

Figure 5.

Vascular effects of photoreleased TAX in SVR-tumor-bearing, female Nu/Nu mice. a) Ultrasound imaging/laser illumination setup. Maximum intensity projection acoustic angiography images were acquired from the flank of SVR-tumor-bearing, female Nu/Nu mice. Images were obtained prior to injection (baseline) and 5, 15, 25, 35, and 45 min after beginning of l5 min laser (655 nm) illumination (or dark incubation in the case of the control; see Figure S15, Supporting Information). b) Quantitative analysis of microbubble retention at the tumor is normalized to the baseline. Retention of microbubbles in the tumor, consistent with vessel damage, is significantly higher with Cy5-B12-TAX 4 loaded mRBCs and 655 nm exposure than with the controls. c) Ultrasound image of tumor from a mouse injected with RBC/Cy5-B12-TAX 2 prior to (top) and 45 min after (bottom) exposure to a 655 nm laser (100 mW, 5 min) at the tumor site. Scale bar = 1 mm.

3. Conclusion

We have devised a drug delivery system utilizing a vitamin B12 scaffold to retain a taxane drug within the interior of circulating RBCs. Illumination at the appropriate wavelength results in scission of the B12-Drug bond and subsequent release of the drug from the RBC carrier. The wavelength of photolysis is designated by the fluorophore appended to B12, which in this study is a Cy5 derivative capable of capturing far red photons (633 – 655 nm). We have shown that phototherapeutic agents can be homogenously loaded into mRBCs at high concentrations (>30 μM) and that the RBCs can be imaged in vivo. Illumination of a targeted tissue site results in the release of the taxane from circulating erythrocytes in a spatially selective fashion and induces changes to the vasculature consistent with that observed with docetaxel.

RBC-based phototherapeutics offer a biocompatible, localized delivery alternative for a wide range of potent therapeutics, with light providing both spatial and temporal control over where and when a drug is released. These properties have the potential to reduce side effects and decrease the administered dose. Our system extends phototherapeutics into the optical window of tissue, where light enjoys the greatest depth of tissue penetration. In addition, phototherapeutics in combination with RBCs offer a number of potential advantages relative to synthetic drug carriers, including enhanced circulatory lifetime, biocompatibility, and a large drug payload per carrier. As natural carriers, RBCs serve as a barrier, protecting the phototherapeutic from clearance mechanisms while protecting healthy tissue from the undesired assault of the cytotoxic agent. These advantages suggest that the amalgamation of B12-based phototherapeutics and RBCs carriers have the potential to serve as a synergistic combination for the precision delivery of therapeutic agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

D. S. Lawrence and P. A. Dayton acknowledge a Developmental Research Award from the Lineberger Cancer Center and the UNC Eshelman Institute for Innovation. D. S. Lawrence and T. K. Tarrant thank the Rheumatology Research Foundation. P. A. Dayton acknowledges the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA170665). C.M. Marvin and E. M. Zywot were supported from a T32 CA71341 training grant. B. M. Vickerman was supported by an American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship (18PRE33960038). The UNC Flow Cytometry Core Facility is supported by a P30CA016086 Cancer Center Core Support Grant to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and by a grant from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health under award number 1 S10 OD017984–01A1. Animal histopathology services was performed by the Animal Histopathology & Laboratory Medicine Core at the University of North Carolina, which is supported in part by an NCI Center Core Support Grant (5P30CA016086–41) to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Animal Studies were performed within the UNC Lineberger Animal Studies Core Facility at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The UNC Lineberger Animal Studies Core is supported in part by an NCI Center Core Support Grant (CA16086) to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. We also thank the Hooker Imaging Core at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the UNC Mouse Phase I unit for providing animals and expertise. The team appreciates the contributions of Samantha Fix in preliminary studies for this project.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Christina M. Marvin, Department of Chemistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA

Song Ding, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Rachel E. White, Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA

Natalia Orlova, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Qunzhao Wang, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Emilia M. Zywot, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA

Brianna M. Vickerman, Department of Chemistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA

Lauren Harr, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Teresa K. Tarrant, Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology and Immunology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27710, USA

Paul A. Dayton, Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA

David S. Lawrence, Department of Chemistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; Department of Pharmacology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

References

- [1].Ai D; Banchs J; Owusu-Agyemang P; Cata JP, Minerva Anestesiol. 2014, 80 (5), 586–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kydd J; Jadia R; Velpurisiva P; Gad A; Paliwal S; Rai P, Pharmaceutics 2017, 9 (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Raucher D; Dragojevic S; Ryu J, Frontiers in oncology 2018, 8, 624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ding S; O’Banion CP; Welfare JG; Lawrence DS, Cell Chem. Biol 2018, 25 (6), 648–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nam L; Coll C; Erthal LCS; de la Torre C; Serrano D; Martinez-Manez R; Santos-Martinez MJ; Ruiz-Hernandez E, Materials (Basel) 2018, 11 (5), 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhang J; Tang H; Liu Z; Chen B, Int J Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 8483–8493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Firer MA; Gellerman G, J Hematol Oncol 2012, 5, 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dawidczyk CM; Kim C; Park JH; Russell LM; Lee KH; Pomper MG; Searson PC, J Control Release 2014, 187, 133–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Diamantis N; Banerji U, Br J Cancer 2016, 114 (4), 362–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shi J; Kantoff PW; Wooster R; Farokhzad OC, Nat Rev Cancer 2017, 17 (1), 20–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Karimi M; Sahandi Zangabad P; Baghaee-Ravari S; Ghazadeh M; Mirshekari H; Hamblin MR, J Am Chem Soc 2017, 139 (13), 4584–4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ankenbruck N; Courtney T; Naro Y; Deiters A, Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit 2018, 57 (11), 2768–2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yang Y; Mu J; Xing B, Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 2017, 9 (2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].O’Banion CP; Lawrence DS, Chembiochem 2018, 19 (12), 1201–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shell TA; Shell JR; Rodgers ZL; Lawrence DS, Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit 2014, 53 (3), 875–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pierige F; Bigini N; Rossi L; Magnani M, Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 2017, 9 (5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Villa CH; Anselmo AC; Mitragotri S; Muzykantov V, Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2016, 106 (Pt A), 88–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yan J; Yu J; Wang C; Gu Z, Small Methods 2017, 1 (12), 1700270. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dale GL; Villacorte DG; Beutler E, Biochem Med 1977, 18 (2), 220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Deloach J; Ihler G, Biochim Biophys Acta 1977, 496 (1), 136–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ganesh T, Bioorg Med Chem 2007, 15 (11), 3597–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jordan MA; Wilson L, Nat Rev Cancer 2004, 4 (4), 253–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wierzba AJ; Hassan S; Gryko D, Asian Journal of Organic Chemistry 2018, 8 (1), 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hughes RM; Marvin CM; Rodgers ZL; Ding S; Oien NP; Smith WJ; Lawrence DS, Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit 2016, 55 (52), 16080–16083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Minetti G; Egee S; Morsdorf D; Steffen P; Makhro A; Achilli C; Ciana A; Wang J; Bouyer G; Bernhardt I; Wagner C; Thomas S; Bogdanova A; Kaestner L, Blood Rev 2013, 27 (2), 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].D’Alessandro A; Righetti PG; Zolla L, J Proteome Res 2010, 9 (1), 144–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kakhniashvili DG; Bulla LA Jr.; Goodman SR, Mol Cell Proteomics 2004, 3 (5), 501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shin S; Ku Y; Babu N; Singh M, Indian J Exp Biol 2007, 45 (1), 121–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Makley AT; Goodman MD; Friend LA; Johannigman JA; Dorlac WC; Lentsch AB; Pritts TA, Shock 2010, 34 (1), 40–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pan D; Vargas-Morales O; Zern B; Anselmo AC; Gupta V; Zakrewsky M; Mitragotri S; Muzykantov V, PLoS One 2016, 11 (3), e0152074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chrominski M; Lewalska A; Gryko D, Chem Commun (Camb) 2013, 49 (97), 11406–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chrominski M; Lewalska A; Karczewski M; Gryko D, J Org Chem 2014, 79 (16), 7532–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cameron AC; Touyz RM; Lang NN, Can J Cardiol 2016, 32 (7), 852–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fung AS; Lee C; Yu M; Tannock IF, BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].McAuliffe G; Roberts L; Roberts S, Biotechnology Letters 2002, 24 (12), 959–964. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Soultati A; Mountzios G; Avgerinou C; Papaxoinis G; Pectasides D; Dimopoulos MA; Papadimitriou C, Cancer Treat Rev 2012, 38 (5), 473–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sonnichsen DS; Relling MV, Clin Pharmacokinet 1994, 27 (4), 256–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schrijvers D, Clin Pharmacokinet 2003, 42 (9), 779–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chen H; Sha H; Zhang L; Qian H; Chen F; Ding N; Ji L; Zhu A; Xu Q; Meng F; Yu L; Zhou Y; Liu B, Int J Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 5347–5359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Fu Q; Lv P; Chen Z; Ni D; Zhang L; Yue H; Yue Z; Wei W; Ma G, Nanoscale 2015, 7 (9), 4020–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gao L; Wang H; Nan L; Peng T; Sun L; Zhou J; Xiao Y; Wang J; Sun J; Lu W; Zhang L; Yan Z; Yu L; Wang Y, Bioconjug Chem 2017, 28 (10), 2591–2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jiang X; Wang K; Zhou Z; Zhang Y; Sha H; Xu Q; Wu J; Wang J; Wu J; Hu Y; Liu B, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 488 (2), 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Su J; Sun H; Meng Q; Yin Q; Zhang P; Zhang Z; Yu H; Li Y, Advanced Functional Materials 2016, 26 (41), 7495–7506. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhu DM; Xie W; Xiao YS; Suo M; Zan MH; Liao QQ; Hu XJ; Chen LB; Chen B; Wu WT; Ji LW; Huang HM; Guo SS; Zhao XZ; Liu QY; Liu W, Nanotechnology 2018, 29 (8), 084002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Harisa GI; Ibrahim MF; Alanazi F; Shazly GA, Saudi Pharm J 2014, 22 (3), 223–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Copple BL; Banes A; Ganey PE; Roth RA, Toxicol Sci 2002, 65 (2), 309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rubenberg ML; Bull BS; Regoeczi E; Dacie JV; Brain MC, Lancet. 1966, 2, 1121–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].George JN; Nester CM, N Engl J Med 2014, 371 (7), 654–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Jones SL, Hematopathol Mol Hematol 1998, 11 (3–4), 147–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Rabah SO, Saudi J Biol Sci 2010, 17 (2), 105–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Faivre S; Demetri G; Sargent W; Raymond E, Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007, 6 (9), 734–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zheng Q; Jockusch S; Zhou Z; Blanchard SC, Photochem Photobiol 2014, 90 (2), 448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Huck JJ; Zhang M; Mettetal J; Chakravarty A; Venkatakrishnan K; Zhou X; Kleinfield R; Hyer ML; Kannan K; Shinde V; Dorner A; Manfredi MG; Shyu WC; Ecsedy JA, Mol Cancer Ther 2014, 13 (9), 2170–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Arbiser JL; Moses MA; Fernandez CA; Ghiso N; Cao Y; Klauber N; Frank D; Brownlee M; Flynn E; Parangi S; Byers HR; Folkman J, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94 (3), 861–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Gessner RC; Frederick CB; Foster FS; Dayton PA, Int J Biomed Imaging 2013, 2013, 936593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lin F; Shelton SE; Espindola D; Rojas JD; Pinton G; Dayton PA, Theranostics 2017, 7 (1), 196–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.