Abstract

The translocon associated protein (TRAP) complex facilitates the translocation of proteins across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane and associates with the oligosaccharyl transferase (OST) complex to maintain proper glycosylation of nascent polypeptides. Pathogenic variants in either complex cause a group of rare genetic disorders termed, Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation. We report an individual who presented with severe intellectual and developmental disabilities and sensorineural deafness with an unsolved type I CDG, and sought to identify the underlying genetic basis. Exome sequencing identified a novel homozygous variant c.278_281delAGGA [p.Glu93Valfs*7] in the signal sequence receptor 3 (SSR3) subunit of the TRAP complex. Biochemical studies in patient fibroblasts showed the variant destabilized the TRAP complex with a complete loss of SSR3 protein and partial loss of SSR1 and SSR4. Importantly, all subunit levels were corrected by expression of wild-type SSR3. Abnormal glycosylation status in fibroblasts was confirmed using two markers proteins, GP130 and ICAM1. Our findings confirm mutations in SSR3 cause a novel Congenital Disorder of Glycosylation.

Keywords: Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation, translocon associated complex, oligosaccharyl transferase complex, developmental delay

Synopsis:

A novel frameshift variant in the translocon associated protein, SSR3, disrupts the stability of the TRAP complex and causes a novel Congenital Disorder of Glycosylation.

Introduction

Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are a group of clinically complex metabolic disorders that frequently present with varying degrees of neurological impairments and, depending on the specific type, can have further organ system involvement (Freeze et al 2015; Ferreira et al 2018). To date more than one hundred and thirty unique disorders have been described covering nearly all known glycosylation pathways with most involving defects in the N-linked glycosylation pathway (Ferreira et al 2018; Ng and Freeze 2018; Francisco et al 2018).

A useful and often reliable biomarker for detecting N-linked related CDG’s is the abundant serum glycoprotein, transferrin (Lacey et al 2001; Bruneel et al 2018). Often referred to as carbohydrate deficient transferrin (CDT), an abnormal transferrin profile is frequently designated as a type I or type II, which can indicate the specific portion of the affected pathway, but usually not the specific defective protein (Bruneel et al 2018). A type I CDT profile typically results from a defect in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) localized assembly or transfer of a lipid linked oligosaccharide (LLO) molecule to nascent proteins (Abu Bakar et al 2018). However, type II profiles frequently involve glycan modification in the Golgi apparatus due to abnormalities in glycan processing, trafficking of proteins or nucleotide sugars, irregularities in architecture, pH regulation and ion transport (Abu Bakar et al 2018).

Within the type I group are several disorders involving two functionally and physically linked complexes required for proper N-glycosylation. First, the oligosaccharyl transferase complex (OST) which is required for the transfer of newly synthesized oligosaccharides from the lipid molecule, dolichol, to nascent polypeptide chains (Shrimal et al 2015). In humans, the subunit composition of the OST complex can vary to determine the mechanism of translational modification that occurs. For example, co-translational modification is thought to occur via a STT3A-dependent complex, while post-translational N-glycan addition is STT3B-dependent (Shrimal et al 2015). Second, the translocon associated protein (TRAP) complex is required for translocation of proteins across the ER membrane, enhancing the efficiency of N-linked glycosylation (Braunger et al 2018). A critical component of the TRAP complex is the family of signal sequence receptor proteins (SSR) 1–4, which are critical for the discrimination of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane substrates that must be translocated (Braunger et al 2018). The OST and TRAP complexes have been co-purified, and more recently, cryo-EM has been used to determine how each of the complex components interact to carry out N-glycosylation (Shibatani et al 2005; Braunger et al 2018).

Pathogenic variants causing glycosylation related disorders have been identified in four OST subunits STT3A (OMIM# 601134), STT3B (OMIM# 608605), DDOST (OMIM# 602202), TUSC3 (OMIM# 601385) and two in the translocon complex, SEC61 (OMIM# 609213), SSR4 (OMIM# 300090) (Shrimal et al 2013; Jones et al 2012; Garshasbi et al 2008; Molinari et al 2008; Bolar et al 2016; Losfeld et al 2014).

Methods and Materials

Carbohydrate deficient transferrin isoform (CDT) analysis

CDT analysis was performed as previously described using affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry (Lacey et al 2001).

Exome sequencing and analysis

Exome sequencing was executed on an Illumina HiSeq platform as previously described (Simon et al 2017). Sanger sequencing was performed to confirm candidates and segregation of the variants in parental samples. PCR conditions and primer sequences are available upon request.

Western blot analysis of the TRAP complex, GP130 and ICAM1

Western blot analysis was carried out as previously described using two commercially available control fibroblast lines GM-00038, GM-03348 (Coriell cell repository, USA) and CDG-0359 to determine the protein levels for SSR1–4 (Novus Biologicals, USA) (Losfeld et al 2014). GP130 and ICAM1 western blots were performed as previously described. (Chan et al 2016; He et al 2012).

Complementation of the TRAP complex in SSR3 deficient fibroblasts

Primary fibroblasts from CDG-0359 were transfected with either an empty or SSR3 cDNA (NM_007107.3, OMIM# 606213) expressing vector using an Amaxa nucleofector electroporation apparatus (Lonza, USA). Following electroporation, cells were allowed to recover for 48hrs prior to collecting samples for western blot analysis of SSR1–4 proteins. We determined the electroporation efficiency was >90% for those cells that survived, however survival was only ~40%.

Results

Clinical Report

The parents of the CDG-0359 are consanguineous first cousins of Brazilian origin with a prior pregnancy history of two miscarriages. During the fifth month of pregnancy, CDG-0359 who is a male, was found to have intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Born at term (~40 weeks via cesarean delivery) he presented with severe respiratory distress requiring oxygen support for twenty-four hours. A physical exam, shortly after birth and again at five years of age, revealed he was severely hypotonic with abnormal fat distribution and also had a micropenis with cryptorchidism. He had microcephaly and facial dysmorphisms that included downslanting palpebral fissures, high palate, hypoplastic nasal alae, and a short neck. Strabismus was also present. An overview of the skeletal system revealed scoliosis, osteopenia and hyperextension of the joints. He had failure to thrive due to persistent diarrhea, recurrent vomiting and was unable to eat on his own. Feeding via a nasogastric-tube facilitated weight gain. He also has a long history of recurrent infections. A hearing exam revealed sensorineural deafness. As with many types of CDG, he had significant neurological impairments including severe intellectual disabilities. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed delayed myelination and agenesis of the corpus callosum. His clinical condition has thus remained stable as of age 12.

All newborn screening and follow up testing were normal, except a clear type I CDT profile detected by electrospray ionizing mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) with a mono-oligo: di-oligo value of 0.234 (reference value <0.1) and an a-oligo/di-oligo reason: 0.010 (reference value < 0.050). Subsequently, the proband was screened by Sanger sequencing for potentially pathogenic variants in several type I CDG genes including PMM2 (OMIM# 601785), MPI (OMIM# 154550), ALG1 (OMIM# 605907), DPAGT1 (OMIM# 191350) and SRD5A3 (OMIM# 611715), revealed no known or predicted pathogenic variants. Since the affected individual had a type I CDT profile, we analyzed the LLO structure in primary fibroblasts, which revealed a similar structure (GlcNAc2Man9Glc3) to a healthy control (data not shown). These results eliminated the known N-linked disorders caused by mutations in proteins that result in truncated LLO structure as candidates.

Molecular analysis

Exome sequencing was performed solely on the proband and given the family history of consanguinity, we initially focused on rare variants (<1% allele frequency in gnomAD) in the homozygous state. This identified a novel homozygous INDEL variant c.278_281delAGGA [p.Glu93Valfs*7] in the signal sequence receptor 3 (SSR3). This variant is absent from the gnomAD database (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) (gnomAD r2.0.2 accessed 2.28.2019) of 125,748 exomes and 15,708 whole-genomes of unrelated individuals. Importantly, we have previously shown pathogenic variants in another TRAP complex subunit, SSR4, cause a type I CDG and because there were no actionable variants in other genes known to cause type I CDG, we prioritized SSR3 for further analysis (Losfeld et al 2014; Ng et al 2015).

Furthermore, no additional suspected subjects were identified at several large clinical and research sequencing centers. Sanger sequencing confirmed both parents to be heterozygous carriers.

Western blot analysis

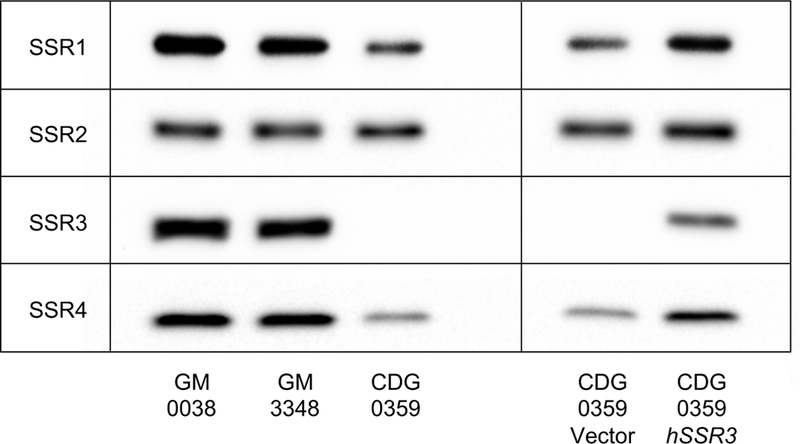

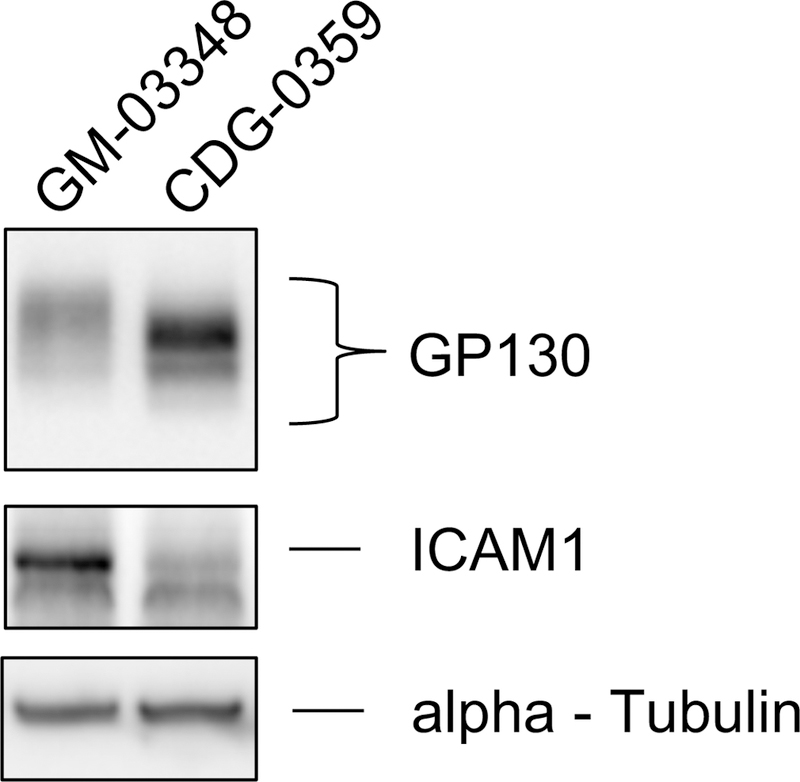

Loss of SSR4 protein in either individuals with SSR4-CDG or siRNA knockdown in HELA cells decreases stability of the TRAP complex (Ng et al 2015; Pfeffer et al 2017). Similarly, siRNA knockdown of SSR3 also has dramatic effects on TRAP complex stability (Pfeffer et al 2017). Consistent with this observation, western blot analysis showed the c.278_281delAGGA [p.Glu93Valfs*7] variant in CDG-0359 had a functional consequence for the TRAP complex, with complete loss of SSR3 and substantial loss of SSR1 and SSR4 proteins (Figure 1). Importantly, complementation of primary fibroblasts from CDG-0359 with a plasmid containing wild-type SSR3 cDNA completely restored the expression of SSR3 protein and the integrity of the TRAP complex as determined by the reappearance of SSR1 and SSR4 protein levels seen in control fibroblasts (Figure 1). Finally, we show that primary fibroblast from CDG-0359 have abnormal glycosylation of two previously reported marker proteins, GP130 and ICAM1 (Chan et al 2016; He et al 2012) (Figure 2). These results along with the abnormal CDT indicate that the mutation in SSR3 compromises N-linked glycosylation.

Figure 1:

Western blot analysis of SSR1–4 proteins from two apparently healthy controls (GM-00038, GM-03348) and CDG-0359 showing complete loss of SSR3 with partial loss of SSR1 and 4 in the affected individual. Transient expression of wild-type SSR3 cDNA, but not an empty vector, was able to restore the complex integrity with the reappearance of SSR1 and 4.

Figure 2:

Western blot analysis for two glycoprotein markers in GM-03348 and CDG-0359 fibroblasts. Western blot analysis of GP130 showed a reduced molecular weight in CDG-0359, when compared to the control GM-03348, suggestive of loss of N-glycan chains. ICAM1 showed significantly reduced protein expression and molecular weight in CDG-0359 compared to the control. GM-03348 is representative of three controls. Monoclonal alpha-Tubulin (12G10) was used to ensure equal loading for each sample.

Discussion

In mammals, it is estimated that one third of all proteins must be translocated across the ER membrane in a SEC61-dependent manner and specificity for client proteins is determined by the SSR proteins (Pfeffer et al 2017). Cryo-EM and siRNA knockdown studies have been useful in modeling how the OST and TRAP complexes cooperate to regulate glycosylation and human disorders highlight their importance in embryonic development (Pfeffer et al 2017). For example, we had previously reported that pathogenic variants in the TRAP complex subunit, SSR4, causes a CDG characterized by developmental and intellectual delays with varying system involvements (Losfeld et al 2014; Ng et al 2015). Yet, only one mouse model has been generated for studying the developmental role of either the OST or TRAP complex and it involved Ssr3 (Yamaguchi et al 2011).

Ssr3 knockout (KO) mice display severe intrauterine embryonic growth retardation (IUGR) and die shortly after birth, possibly from severe organ growth deficiency that is especially prominent in the lungs. The individual we report herein, also had severe respiratory distress at birth. When compared to wild-type litter mates, placenta from Ssr3 KO mice are smaller in total size, but also had widespread vascular network malformations which could explain the IUGR (Yamaguchi et al 2011). It is unclear if CDG-0359 had placenta abnormalities. Glycosylation studies were not performed on the Ssr3 knockout mice.

In addition to its role in translocation of proteins across the ER membrane, the TRAP complex is linked to the ER associated degradation (ERAD) pathway. When mammalian cells are exposed to ER stresses such as tunicamycin, dramatic up-regulation of SSR1–4 occurs (Nagasawa et al 2007). Furthermore, loss of any of the four SSR subunits by siRNA knockdown caused delayed clearance of known ERAD substrates, which was specifically due to an inability of the TRAP complex to bind unfolded substrate (Nagasawa et al 2007).

In summary, we describe a novel type I CDG involving a homozygous loss-of-function frameshift variant in the TRAP complex protein, SSR3. The variant resulted in complete loss of SSR3 protein and destabilization of the TRAP complex. These results confirm pathogenicity of the variant and a role for SSR3 in N-glycosylation.

Acknowledgements

We thank the families for their continued support and financial support from the family and friends of Isabella Conneran. We thank Jamie Smolin for her assistance.

Funding details: This work is supported by The Rocket Fund, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01DK099551 (to H.H.F).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Bobby G. Ng, Charles Marques Lourenço, Marie-Estelle Losfeld, Kati J. Buckingham, Martin Kircher, Deborah A. Nickerson, Jay Shendure, Michael J. Bamshad and Hudson H. Freeze declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Ethical approval and Informed consent: Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (IRB-2014-038-17). Written informed consent was obtained.

Animal rights: This article does not contain any studies with animal subjects.

REFERENCES

- Abu Bakar N, Lefeber DJ, van Scherpenzeel M (2018) Clinical glycomics for the diagnosis of congenital disorders of glycosylation. J Inherit Metab Dis 41: 499–513. 10.1007/s10545-018-0144-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolar NA, Golzio C, Zivna M, et al. (2016) Heterozygous Loss-of-Function SEC61A1 Mutations Cause Autosomal-Dominant Tubulo-Interstitial and Glomerulocystic Kidney Disease with Anemia. Am J Hum Genet 99: 174–187. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunger K, Pfeffer S, Shrimal S, et al. (2018) Structural basis for coupling protein transport and N-glycosylation at the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Science 360: 215–219. 10.1126/science.aar7899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneel A, Cholet S, Drouin-Garraud V, et al. (2018) Complementarity of electrophoretic, mass spectrometric, and gene sequencing techniques for the diagnosis and characterization of congenital disorders of glycosylation. Electrophoresis 10.1002/elps.201800021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chan B, Clasquin M, Smolen GA, et al. (2016) A mouse model of a human congenital disorder of glycosylation caused by loss of PMM2. Hum Mol Genet 25: 2182–2193. 10.1093/hmg/ddw085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira CR, Altassan R, Marques-Da-Silva D, Francisco R, Jaeken J, Morava E (2018) Recognizable phenotypes in CDG. J Inherit Metab Dis 41: 541–553. 10.1007/s10545-018-0156-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco R, Marques-da-Silva D, Brasil S, et al. (2018) The challenge of CDG diagnosis. Mol Genet Metab 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Freeze HH, Eklund EA, Ng BG, Patterson MC (2015) Neurological aspects of human glycosylation disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci 38: 105–125. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-034019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garshasbi M, Hadavi V, Habibi H, et al. (2008) A defect in the TUSC3 gene is associated with autosomal recessive mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet 82: 1158–1164. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He P, Ng BG, Losfeld ME, Zhu W, Freeze HH (2012) Identification of intercellular cell adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) as a hypoglycosylation marker in congenital disorders of glycosylation cells. J Biol Chem 287: 18210–18217. 10.1074/jbc.M112.355677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MA, Ng BG, Bhide S, et al. (2012) DDOST mutations identified by whole-exome sequencing are implicated in congenital disorders of glycosylation. Am J Hum Genet 90: 363–368. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey JM, Bergen HR, Magera MJ, Naylor S, O’Brien JF (2001) Rapid determination of transferrin isoforms by immunoaffinity liquid chromatography and electrospray mass spectrometry. Clin Chem 47: 513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losfeld ME, Ng BG, Kircher M, et al. (2014) A new congenital disorder of glycosylation caused by a mutation in SSR4, the signal sequence receptor 4 protein of the TRAP complex. Hum Mol Genet 23: 1602–1605. 10.1093/hmg/ddt550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari F, Foulquier F, Tarpey PS, et al. (2008) Oligosaccharyltransferase-subunit mutations in nonsyndromic mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet 82: 1150–1157. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng BG, Raymond K, Kircher M, et al. (2015) Expanding the Molecular and Clinical Phenotype of SSR4-CDG. Hum Mutat 36: 1048–1051. 10.1002/humu.22856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng BG, Freeze HH (2018) Perspectives on Glycosylation and Its Congenital Disorders. Trends Genet 34: 466–476. 10.1016/j.tig.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa K, Higashi T, Hosokawa N, Kaufman RJ, Nagata K (2007) Simultaneous induction of the four subunits of the TRAP complex by ER stress accelerates ER degradation. EMBO Rep 8: 483–489. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S, Dudek J, Schaffer M, et al. (2017) Dissecting the molecular organization of the translocon-associated protein complex. Nat Commun 8: 14516 10.1038/ncomms14516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrimal S, Ng BG, Losfeld ME, Gilmore R, Freeze HH (2013) Mutations in STT3A and STT3B cause two congenital disorders of glycosylation. Hum Mol Genet 22: 4638–4645. 10.1093/hmg/ddt312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrimal S, Cherepanova NA, Gilmore R (2015) Cotranslational and posttranslocational N-glycosylation of proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Semin Cell Dev Biol 41: 71–78. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibatani T, David LL, McCormack AL, Frueh K, Skach WR (2005) Proteomic analysis of mammalian oligosaccharyltransferase reveals multiple subcomplexes that contain Sec61, TRAP, and two potential new subunits. Biochemistry 44: 5982–5992. 10.1021/bi047328f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MT, Ng BG, Friederich MW, et al. (2017) Activation of a cryptic splice site in the mitochondrial elongation factor GFM1 causes combined OXPHOS deficiency. Mitochondrion 34: 84–90. 10.1016/j.mito.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi YL, Tanaka SS, Oshima N, Kiyonari H, Asashima M, Nishinakamura R (2011) Translocon-associated protein subunit Trap-gamma/Ssr3 is required for vascular network formation in the mouse placenta. Dev Dyn 240: 394–403. 10.1002/dvdy.22528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]