Abstract

Background:

Biomarkers are being used increasingly to support the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Novel biomarkers that increase diagnostic specificity of DLB are needed. We assessed previously known FDG-PET occipital cortex hypometabolism, and cingulate island sign biomarkers of DLB against a novel amygdala signature.

Methods:

Retrospective analysis of 49 patients evaluated at one tertiary memory clinic. All had a FDG-PET brain scan performed as part of their diagnostic work up evaluating three common neurodegenerative etiologies: Alzheimer dementia (AD), Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and DLB. A consensus diagnosis of dementia was made based on accepted clinical criteria for AD, FTD and DLB. FDG-PET regional metabolism was delineated by automatic segmentation as well as manual tracing of amygdala and posterior cingulate volumes of interest. Mean normalized values calculated for regional FDG-PET signatures of DLB: occipital cortex hypometabolism and preservation of posterior cingulate and amygdala metabolism relative to whole brain metabolism were evaluated.

Results:

Significant overlap between DLB and AD patients (occipital, parietal, temporal and frontal hypometabolism) and between DLB and FTD (frontal hypometabolism and the posterior cingulate sign) were identified. Right amygdala (p=0.028) and right posterior cingulate (p=0.035) mean normalized regional metabolism levels were preserved in DLB compared to AD. Among subjects at less advanced stages of dementia (MoCA>10), relative preservation of regional metabolism was notable across both left (p=0.006) and right (p=0.020) amygdala.

Conclusion:

Relative preservation of amygdala metabolism could complement previously described FDG-PET findings in earlier stages of DLB.

Keywords: Dementia with lewy bodies, FDG PET, occipital hypometablism, cingulate island sign, amygdala, diagnostic utility

Graphical Abstract

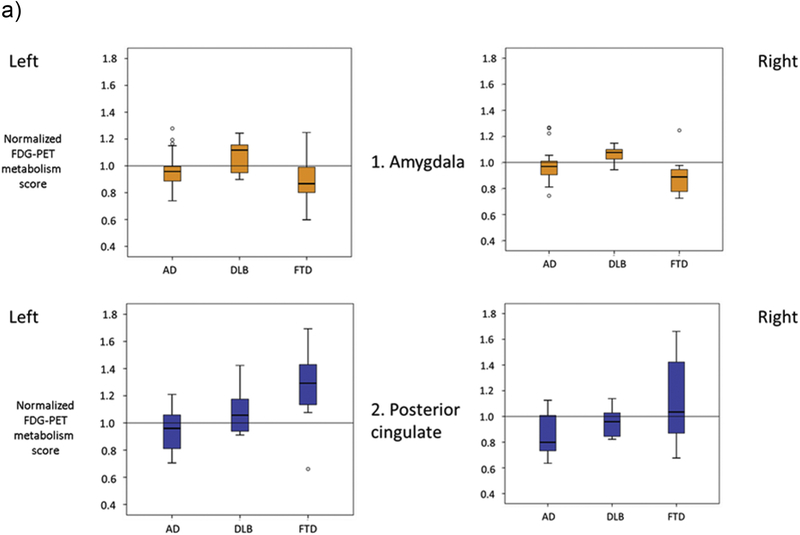

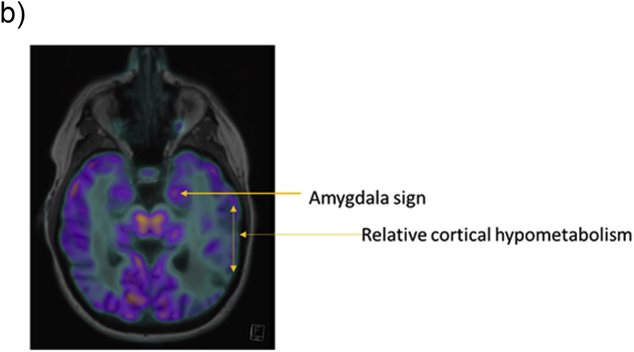

Mean regional amygdala and posterior cingulate metabolism in three disease groups Alzheimer’s dementia (AD), Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) & Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with ‘Amygdala sign’ delineated in false color brain FDG PET

Introduction:

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a common cause of dementia among the elderly that is often diagnostically challenging. In addition to the core clinical signs and symptoms of DLB the 2017 criteria also include biomarkers weighted as ‘indicative’ or ‘supportive’ based on their diagnostic specificity and quality of evidence available [1]. Decreased perfusion or metabolism in the occipital lobes, as identified on SPECT or FDG-PET, respectively, and the cingulate island sign on FDG-PET imaging are noted as supportive imaging biomarkers of DLB [1]. These FDG-PET signs have been proposed as DLB diagnostic signs to distinguish from AD since 2005 and 2009 respectively [2,3].

More recently, a combined MRI tractography and volumetry study has identified elevated local diffusivity despite little loss of gray matter volume in the amygdala in DLB compared to AD [4]. The amygdala is a gray matter structure involved early and severely with Lewy body pathology and microvacuolation in DLB [5]. However, amygdala gray matter density, which is an indirect measure of the neuronal density is normal in DLB [4, 6]. This phenomenon of elevated local diffusivity with little gray matter volume loss in the amygdala may reflect local microvacuolation with relative neuronal preservation in patients with DLB compared to AD [7, 4]. Relative neuronal preservation in the amygdala raises the possibility of FDG-PET being a used as a tool to help distinguish DLB from AD, which was the principal motive of this study. We aimed to evaluate if relative preservation of metabolism in the amygdala on FDG-PET was a potential imaging marker for DLB (the "amygdala sign").

Methods:

This was a retrospective case study approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. All patients had a MRI brain, FDG-PET brain scan and had a stable clinical diagnosis for at least 2 years and had a baseline Montreal Cognitive Assessment score (MoCA). The consensus diagnosis of dementia of AD, FTD or DLB was made based on published clinical criteria by a team of neurologists, a geriatrician, and a radiologist [2, 8, 9]. The demographic data describing the patients and cognitive measures are presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographics, AD: Alzheimer dementia, DLB: Dementia with Lewy bodies, FTD: Frontotemporal dementia

| AD | DLB | FTD | F,χ | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 19 | 15 | 15 | ||

| Age, Yrs (mean, SD) | 65.2 (7.5) |

68.7 (8) |

64.4 (8.4) |

12.4 | 0.3 |

| Sex % F | 63.1% | 26.6% | 53.3% | 2.9 | 0.2 |

| Education, Yrs (mean, SD) | 14.4 (2.6) |

15.6 (3.4) |

14.3 (2.7) |

1.0 | 0.3 |

| MOCA (mean, SD) | 13.1 (4.7) 1 |

16.7 (4.9) 2 |

21.7 (4.9)1,2 |

1.2 | 0.0001 |

significant p values on post hoc Tukey

FDG-PET CT imaging protocol:

FDG-PET scans were obtained using a standard clinical protocol. Subjects fasted for at least 4 hours prior to administration of 18F-FDG (185–370 MBq), and then rested quietly for approximately 45 minutes. PET imaging was performed with a Siemens Biograph 6 HiRez scanner with a 15 minute 3D time-of-flight acquisition in one bed position. A low dose CT was obtained for attenuation correction. PET image reconstruction was performed using an ordered subsets expectation-maximization method with a 168 × 168 matrix.

FDG-PET regional cortical analysis:

All FDG-PET scans were analyzed by one of us (JAP) blinded to the clinical details and the previous read. FDG regional hypometabolism was delineated by either automatic segmentation (for frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital regions) using Siemens Syngo via LEONARDO™ work station or manual tracing (amygdala and posterior cingulate). Volume of interest (VOIs) were created by atlas registration when co-registered with PET template. VOI standardized uptake values (SUVs) found to be below the average whole brain SUV of that individual were noted as hypometabolic, while those above whole brain average in the posterior cingulate and amygdala were noted as ‘preserved.’ Common factors that impact SUV values were accounted for by standardized acquisition protocol in a single institution and scanner type. Additionally, we examined comparable stages of dementia between AD and DLB, such that diffuse brain atrophy differences are nevertheless not expected to lead to relative ‘preservation’ of regional metabolism in the amygdala and posterior cingulate regions of interest. We report posterior cingulate preservation relative to whole brain metabolism, and not as cingulate island sign (posterior cingulate cortex relative to the precuneus plus cuneus) for two principal purposes. This approach allowed us to a) compare two brain regions, amygdala and posterior cingulate, against a common baseline and, b) given the small number of subjects, to ensure effects of regional cortical atrophy differences between subjects (medial temporal versus occipital atrophy predominance) do not significantly impact the evaluation of relative preservation of amygdala and posterior cingulate compared to adjacent cortical regions.

Statistical analyses:

After testing for homogeneity of variance by Levene’s test, Analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were used to compare groups on demographics and Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) scores. Post hoc Tukey tests were performed when equal variances were confirmed. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare PET mean regional hypometabolism. Among variables of significance, Mann Whitney U test was used to compare pairwise sample differences. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS™ (Chicago, IL) statistical software package.

Results:

15 DLB and FTD patients each and 19 AD patients were included in this analysis. The three groups were not significantly different on mean age, sex and education years, but the FTD group had a higher mean MoCA score than the AD and DLB groups on ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test (Table 1).

Regional cortical hypometabolism

No differences in mean occipital, frontal, temporal or parietal metabolism between AD and DLB patients were noted. FTD patients had higher mean regional metabolism compared to AD and DLB (all p<0.001) in all four above regions. .

Preservation of posterior cingulate

DLB and FTD patients had higher mean normalized posterior cingulate metabolism than AD on the right (p=0.035, p=0.014, respectively), but only FTD patients differed from AD on the left (p=0.001). DLB patients had higher mean posterior cingulate metabolism than FTD on the left (p=0.022) and not on the right (p=0.34). The posterior cingulate metabolism was relatively preserved in 80% of DLB subjects, but also noted among 60% of FTD subjects and 31.5% of AD subjects

Amygdala Sign

DLB and FTD patients had higher mean normalized amygdala metabolism than AD only on the right (p=0.028, p=0.012, respectively). DLB patients had higher mean amygdala metabolism than FTD on the left (p=0.013) and not on the right (p=0.001). The presence of the positive amygdala sign was identified in 73.3% DLB subjects, compared with 21% AD and 26.6% FTD subjects. (Figure 1a, b).

Fig. 1a.

Mean regional amygdala and posterior cingulate metabolism in the three disease groups, Alzheimer dementia (AD), Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

Fig. 1b.

Relative preservation of the amygdala metabolism relative to whole brain, 'amygdala sign' in dementia with lewy bodies.

Among patients at earlier stages of dementia (MoCA >10)

In an exploratory analysis of patients with MoCA> 10 (41 of 49 subjects, AD=14, DLB=14, FTD=13), DLB patients had higher mean amygdala metabolism than FTD and AD on both left and right sides (all p<0.05) but not in the posterior cingulate region.

Discussion:

Regional amygdala metabolism was preserved in DLB patients compared to AD and FTD and was particularly notable bilaterally in patients at earlier stages of dementia (MoCA>10). The amygdala sign appears to complement previously described FDG-PET changes in distinguishing DLB from AD and FTD.

Regional cortical FDG-PET quantification revealed significant overlap between patients with DLB and AD and between DLB and FTD in the preservation of posterior cingulate. As our FTD group had higher mean MoCA scores than AD or DLB, it might explain the higher regional cortical metabolism even in the frontal and temporal regions. Changes in regional metabolism pattern in dementia subjects over time are to be expected with disease progression. The CIS has been reported to change over time with more prominence among subjects with milder dementia [10] and we note similar effects with the amygdala sign in this study.

A limitation of this study is the absence of neuropathologic confirmation. To overcome this limitation as best as feasible, all subjects met the strict diagnostic criteria and were followed clinically for 2 years with no change in diagnosis. Nevertheless, the prevalence of mixed pathology is likely. Additional limitations include, the small number of subjects in each diagnostic category, the severity of dementia within the dementia categories and the lack of comparative cohorts of normal cognition subjects and those with Parkinson’s disease dementia. It would be helpful to further evaluate these findings in a larger autopsy confirmed cohort of individuals to overcome the likelihood of a false positive (type 1) error.

While the amygdala sign described here may be useful to lend confidence to a diagnosis regarding the presence or absence of DLB, the data obtained in this study do not permit precise calculation of positive or negative predictive values. Similarly, a recent meta-analysis of studies evaluating the use of FDG PET in neurodegenerative disorders found that no studies were able to provide measures of accuracy of FDG PET for the diagnosis of DLB in patients with mild cognitive impairment [11]. Accordingly, all available data must be considered in the formulation a diagnosis, and FDG PET examinations must be analyzed for all evidence related to relevant diagnoses. We suggest that the amygdala sign should be considered a potentially relevant FDG PET finding.

Conclusion:

Relative preservation of amygdala metabolism, described here as the amygdala sign appears to complement previously described FDG-PET findings for the evaluation of DLB.

Biomarkers have a supportive role in the clinical diagnosis of Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB).

Current FDG PET and SPECT biomarkers of DLB have limited specificity and sensitivity.

Relative preservation of amygdala metabolism complements previously described FDG- PET signs in earlier stages of DLB.

D.

Funding

Additional support was provided by the National Institute on Aging, J.P, grant number 1K23AG055685-01 and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke JBL, grant number UO1 NS100610).

Full financial disclosures of all authors for the past year:

JAP: has received a) Grant support: Alzheimer Association, Keep Memory Alive Foundation, NIA K23AG055685-01,b) Royalty: from Oxford University Press and Springer for serving as a book author/editor.

BT: has received a) Consulting fees from Lilly and Axovant, b) Grant support from Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation and c) funds supporting clinical trials from Biogen, Eisai, Axovant, Avanir, Grifols and Jenssen

James B. Leverenz has received a) Consulting fees from Axovant, GE Healthcare, Navidea Biopharmaceuticals, Takeda, b) Grant support from Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Biogen, Department of Defense, Genzyme/Sanofi, Michael J Fox Foundation, National Institute of Health.

GW, GL and ML: None

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study of retrospective medical records received ethical approval from the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board before initiation, Approval #: 15-1572.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as manuscript does not contain identifiable individual person data.

Availability of data and material

Please contact author for data requests.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References:

- 1.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim SM, Katsifis A, Villemagne VL, Best R, Jones G, Saling M, Bradshaw J, Merory J, Woodward M, Hopwood M, Rowe CC. The 18F-FDG PET cingulate island sign and comparison to 123I-beta-CIT SPECT for diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(10):1638–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantarci K, Avula R, Senjem ML, Samikoglu AR, Zhang B, Weigand SD, Przybelski SA, Edmonson HA, Vemuri P, Knopman DS, Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr. Dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer disease: neurodegenerative patterns characterized by DTI. Neurology. 2010;74(22):1814–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leverenz JB, Hamilton R, Tsuang DW, Schantz A, Vavrek D, Larson EB, Kukull WA, Lopez O, Galasko D, Masliah E, Kaye J, Woltjer R, Clark C, Trojanowski JQ, Montine TJ. Empiric refinement of the pathologic assessment of Lewy-related pathology in the dementia patient. Brain Pathol. 2008;18(2):220–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, Shiung MM, et al. Focal atrophy in dementia with Lewy bodies on MRI: a distinct pattern from Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2007;130:708–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujino Y, Dickson DW. Limbic Lobe Microvacuolation is Minimal in Alzheimer's Disease in the Absence of Concurrent Lewy Body Disease. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 2008;1(4):369–375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on AgingAlzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2011;7(3):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rascovsky K et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011; 134(pt9): 2456–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iizuka T, Iizuka R, Kameyama M. Cingulate island sign temporally changes in dementia with Lewy bodies. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nobili F et al. European Association of Nuclear Medicine and European Academy of Neurology recommendations for the use of brain 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in neurodegenerative cognitive impairment and dementia. Delphi consensus. European Journal of Neurology: The Official Journal of the European Federation of Neurological Societies. 2018; 25(10), 1201–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]