Abstract

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type-1 non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, efavirenz, is widely used to treat HIV-1 infection. Efavirenz is predominantly metabolized into inactive metabolites by CYP2B6, and patients with certain CYP2B6 genetic variants may be at increased risk for adverse effects, particularly central nervous system toxicity and treatment discontinuation. We summarize the evidence from the literature and provide therapeutic recommendations for efavirenz prescribing based on CYP2B6 genotypes.

Keywords: CYP2B6, efavirenz, HIV, AIDS, pharmacogenetics, pharmacogenomics, CPIC, pharmacokinetics, CNS toxicity, metabolism

INTRODUCTION

Efavirenz is a potent inhibitor of HIV type-1 (HIV-1) replication, with a relatively narrow therapeutic index and large inter-individual variability in pharmacokinetics, due in part to variants in the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2B6 gene (CYP2B6). The purpose of this guideline is to provide clinicians information that will allow the interpretation of clinical CYP2B6 genotype tests so that the results can be used to guide efavirenz prescribing. Detailed guidelines for use of efavirenz as well as cost effectiveness of CYP2B6 genotyping are beyond the scope of this document. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines are periodically updated at www.cpicpgx.org/guidelines/.

FOCUSED LITERATURE REVIEW

A systematic literature review focused on CYP2B6 genotype and efavirenz use was conducted (details in Supplemental Material).

GENE: CYP2B6

CYP2B6 is highly polymorphic with 38 known variant alleles and multiple sub-alleles (https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP2B6; CYP2B6 Allele Definition Table (1)). Substantial differences in allele frequencies occur across ancestrally diverse groups (CYP2B6 Frequency Table (1)). Alleles are categorized into functional groups as follows: normal function (e.g., CYP2B6*1), decreased function (e.g., CYP2B6*6 and *9), no function (e.g., CYP2B6*18), and increased function (e.g., CYP2B6*4). Allele function assignments, as described in the CYP2B6 Allele Functionality Table (1), have been made based on in vitro data with or without in vivo data. CYP2B6*6 (p.Q172H, p.K262R) is the most frequent decreased function allele (15% to 60% minor allele frequency depending on ancestry) and has been studied most extensively. While reduced protein expression due to aberrant splicing caused by the c.516G>T (rs3745274, p.Q172H) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) contributes to reduced function of CYP2B6*6 (2), in vitro studies also suggest complex substrate-dependent catalytic effects (reviewed in: (3)). Therefore, it is somewhat challenging to assign function to CYP2B6 alleles, as function may be substrate-specific.

The combination of inherited alleles determines a person’s diplotype. Table 1 defines each phenotype based on genotype and provides examples of diplotypes. Evidence based on few patients suggests that the CYP2B6*4 and *22 alleles are associated with modestly reduced plasma efavirenz exposure. Thus, CYP2B6*4 and *22 are categorized as increased function alleles. The phenotype categories of CYP2B6 rapid metabolizer (RM; one normal function allele and one increased function allele) and CYP2B6 ultrarapid metabolizer (UM; two increased function alleles) were created to allow for the possibility that these may be clinically relevant for efavirenz or other CYP2B6 substrates such as bupropion and methadone. See the CYP2B6 Diplotype-Phenotype Table (1) for a complete list of possible diplotypes and phenotype assignments.

TABLE 1.

ASSIGNMENT OF LIKELY CYP2B6 PHENOTYPES BASED ON GENOTYPES

| Likely phenotype | Genotypes | Examples of CYP2B6 diplotypesb |

|---|---|---|

| CYP2B6 ultrarapid metabolizer | An individual carrying two increased function alleles | *4/*4, *22/*22, *4/*22 |

| CYP2B6 rapid metabolizer | An individual carrying one normal function allele and one increased function allele | *1/*4, *1/*22 |

| CYP2B6 normal metabolizer | An individual carrying two normal function alleles | *1/*1 |

| CYP2B6 intermediate metabolizer | An individual carrying one normal function allele and one decreased function allele OR one normal function allele and one no function allele OR one increased function allele and one decreased function allele OR one increased function allele and one no function allelea | *1/*6, *1/*18, *4/*6, *4/*18, *6/*22, *18/*22 |

| CYP2B6 poor metabolizer | An individual carrying two decreased function alleles OR two no function alleles OR one decreased function allele and one no function allele | *6/*6, *18/*18, *6/*18 |

See text for discussion regarding CYP2B6 rs4803419.

Please refer to the diplotype to phenotype translation table online for a complete list.

Genetic Test Interpretation

Many clinical laboratories report CYP2B6 genotype results using the star-allele (*) nomenclature. The star-allele nomenclature for CYP2B6 alleles is found at the Pharmacogene Variation (PharmVar) Consortium website (https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP2B6). Some laboratories test and report only on specific SNPs that have been most extensively studied, such as c.516G>T and c.983T>C (rs28399499, p.I328T). These variants are the only defining SNPs for CYP2B6*9 and *18, respectively, but c.983T>C is also found in combination with another variant in *16, and c.516G>T is found in combination with other variants in 11 other CYP2B6 alleles (*6, *7, *13, *19, *20, *26, *29, *34, *36, *37, *38). In cases where only these two SNPs are tested, it is not possible to distinguish between the (*) alleles which contain these variants. However, all alleles that carry c.516G>T or c.983T>C are considered decreased function or no function alleles, respectively, and result in the same CYP2B6 phenotypes based on diplotypes. Tables on the CPIC website contain a list of CYP2B6 alleles, the combinations of variants that define each allele, allele functional status, and allele frequency across major ancestral populations as reported in the literature (1).

The limitations of genetic testing as described here include: (1) known star alleles not tested for will not be reported, and instead, the allele will be reported as *1 by default; (2) in cases where only c.516G>T and/or c.983T>C variants are genotyped, it will not be known if they exist in combination with other variants, and the alleles may be reported as *9 and *18, respectively, by default (although this limitation should not affect efavirenz plasma exposure); (3) rare variants may not be genotyped; (4) tests are not designed to detect unknown or de novo variants; (5) CYP2B6 structural variations exist (hybrids, duplications), but little is known of their frequencies and clinical relevance.

Available Genetic Test Options

See the Genetic Testing Registry (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtr/) for more information on commercially available clinical testing options.

Incidental Findings

No diseases or conditions have been consistently or strongly linked to genetic variations in CYP2B6 independent of drug metabolism and response.

Other Considerations

In a genome-wide association study, CYP2B6 rs4803419 (g.15582C>T) was independently associated with increased plasma efavirenz exposure (4). Patients who were homozygous for the minor allele (g.15582T/T) had plasma efavirenz concentrations comparable to CYP2B6 intermediate metabolizers (based on CYP2B6 c.516G>T and c.983T>C status). This SNP is not defining for any particular star allele but is part of the CYP2B6 *13 and *15 haplotypes, and the CYP2B6*1C suballele as defined in PharmVar (https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP2B6).

Another CYP2B6 SNP, rs2279345 (g.18492T>C), has been associated with slightly decreased plasma efavirenz concentrations (5–9). This SNP is not part of any defined star alleles. The presence of this SNP together with co-administration of a strong CYP inducer may increase the likelihood of sub-therapeutic plasma efavirenz concentrations (5).

DRUG: EFAVIRENZ

Background

Efavirenz is a non-nucleoside human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitor that suppresses HIV-1 replication. For treatment-naïve, HIV-positive individuals, efavirenz in combination with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine has been a cornerstone of treatment for more than 15 years based on its efficacy in randomized clinical trials, long half-life that allows for once-daily dosing, and availability of co-formulation into a single tablet. It was part of the first “one pill, once a day” treatment for HIV and largely supplanted the more cumbersome protease inhibitor-based regimens as first-line therapy. However, in 2015 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services re-assigned efavirenz-based regimens from the “recommended” to the “alternative” therapy category based on comparisons to HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based therapy in randomized clinical trials, which has better tolerability (efavirenz is notable for central nervous system [CNS] side effects) and fewer drug-drug interactions than efavirenz-based regimens (10). Efavirenz is still extensively prescribed, especially in resource-limited countries worldwide, and is recommended as part of a first-line regimen for women who are pregnant or desiring pregnancy in World Health Organization guidelines (11). Unlike some other antiretrovirals, efavirenz-containing regimens can be prescribed to patients who are receiving rifampicin-containing therapy for tuberculosis.

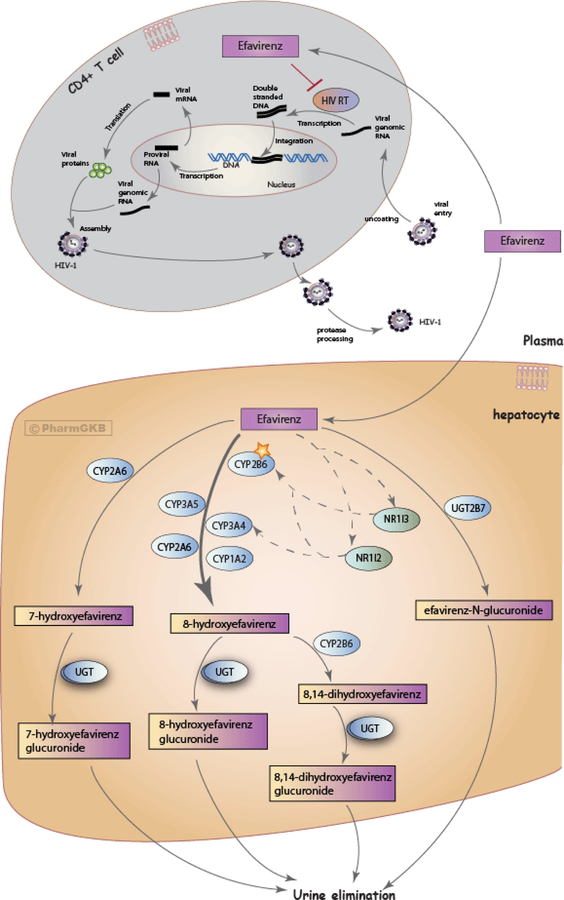

Efavirenz is metabolized by CYP enzymes to form inactive hydroxylated metabolites (12) and by UDP-glucuronsyltransferases (UGT)-mediated direct N-glucuronidation (13). The major efavirenz metabolite is 8-hydroxy-efavirenz, which is generated primarily by CYP2B6 and lacks antiviral activity. Other CYP enzymes, including CYP2A6, CYP3A4, and CYP1A2 play minor roles in efavirenz 8-hydroxylation. CYP2A6-mediated hydroxylation to 7-hydroxy-efavirenz and UGT2B7-mediated glucuronidation to efavirenz N-glucuronide are minor metabolic pathways, although these enzymes may play a larger role in CYP2B6 poor metabolizers. The hydroxylated metabolites of efavirenz undergo conjugation via glucuronidation and/or sulfation and are subsequently excreted in urine. Details of efavirenz metabolic pathways are provided at the PharmGKB website and in Figure 1 (12, 14). The contribution of these pathways may differ following a single dose of efavirenz versus chronic dosing. Efavirenz increases CYP2B6 expression via activation of the constitutive androstane receptor (15). As a result, chronic dosing of efavirenz enhances its own metabolism (“autoinduction”). The magnitude of efavirenz autoinduction varies among individuals and is in part affected by variations in the CYP2B6 gene. For example, there is considerable CYP2B6 induction with the CYP2B6*1/*1 and *1/*6 genotypes, but little or no autoinduction with CYP2B6*6/*6 (16). Relationships between CYP2B6 genotype and apparent oral clearance for efavirenz are shown in Figure S1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of efavirenz metabolism and mechanism of action against HIV (12, 14) An interactive version of the pathway is available at: https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA166123135). Image reproduced and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 from PharmGKB.

Therapeutic drug monitoring may be used in some situations to ensure adequate plasma efavirenz concentrations. A therapeutic range for plasma efavirenz concentrations of 1 to 4 μg/mL has been suggested (17), although concentrations somewhat less than 1 μg/mL do not consistently predict treatment failure, and concentrations greater than 4 μg/mL do not consistently predict toxicity. In one observational cohort study, virologic failure was observed in 50% of patients with plasma efavirenz concentrations less than 1 μg/mL (which may have reflected nonadherence in some patients) as compared to 22% and 18% of patients with concentrations between 1 to 4 μg/mL and greater than 4 μg/mL, respectively. CNS side effects were observed in 24%, 9%, and 0% of patients with plasma efavirenz concentrations of greater than 4 μg/mL, 1 to 4 μg/mL, and less than 1 μg/mL, respectively (17). CNS side effects may manifest as disordered sleep, impaired concentration, psychosis, suicidal ideation, and depression Such effects typically manifest within the first few days of treatment initiation and largely resolve with continued dosing. However, symptoms may persist in some patients, impacting quality of life and resulting in treatment discontinuation. To minimize CNS adverse effects during waking hours, efavirenz is typically taken at bedtime.

Linking Genetic Variability to Variability in Drug-related Phenotypes

Substantial evidence links CYP2B6 genotype with variability in plasma efavirenz concentrations and with adverse effects. Most studies have examined the impact of CYP2B6 c.516G>T and c.983T>C; therefore, these variants provide the basis for our clinical recommendations. As outlined in Table S1, the evidence associating these two variants with increased plasma efavirenz concentrations was strong. Multiple studies have shown that the CYP2B6 poor metabolizer genotype, particularly defined by homozygosity or compound heterozygosity for CYP2B6 c.516G>T and/or c.983T>C, is associated with decreased efavirenz clearance (Figure S1) and increased risk for efavirenz toxicity (particularly CNS toxicity, hepatic injury (18), and QTc prolongation (19)) and/or treatment discontinuation, although some studies have not shown such an association. Such associations appear to vary with race/ethnicity. For other CYP2B6 alleles that are associated with interindividual variability in plasma efavirenz concentrations (e.g., CYP2B6*4, *22, and g.15582C>T), associations have not been demonstrated with reduced efficacy, increased toxicity, or treatment discontinuation, perhaps because these alleles are either infrequent or have modest effects on plasma efavirenz exposure.

Therapeutic Recommendations

CYP2B6-guided efavirenz dosing, particularly in the presence of CYP2B6 c.516G>T, has been shown in clinical studies to be associated with therapeutic plasma efavirenz concentrations and decreased CNS toxicity, while maintaining virologic efficacy (see Table S1). Table 2 summarizes therapeutic recommendations for efavirenz prescribing in adults based on CYP2B6 phenotype. These recommendations also apply to children weighing more than 40 kg, as adult dosing applies to this group. Based on current evidence (Table S1), CYP2B6 normal metabolizers (NMs) are expected to have normal efavirenz metabolism and achieve therapeutic efavirenz concentrations with standard dosing (600 mg/day). CYP2B6 intermediate metabolizers (IMs) may experience higher dose-adjusted trough concentrations compared with NMs, which may put these patients up to a 1.3-fold increased risk of adverse effects (20–25). For these patients, there is a “moderate” recommendation to consider initiating efavirenz with a decreased dose of 400 mg/day. CYP2B6 poor metabolizers (PMs) are at greatest risk for higher dose-adjusted trough concentrations compared with NMs and IMs, and greater overall plasma efavirenz exposure, which puts these patients up to a 4.8-fold increased risk for adverse effects and treatment discontinuation (20–31). For these patients, there is a “moderate” recommendation to consider initiating efavirenz with a decreased dose of either 400 or 200 mg/day. This “moderate” rather than “strong” recommendation reflects the fact that most CYP2B6 PMs do not discontinue efavirenz 600 mg/day for adverse effects. Dose reduction to 400 mg/day may be feasible without increasing pill burden because in 2018 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a generic co-formulated product consisting of efavirenz (400 mg), lamivudine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. There is currently no co-formulated tablet with 200 mg efavirenz, so decreasing the dose to 200 mg/day may be complicated by increased pill burden. If therapeutic drug monitoring is available and a decreased efavirenz dose is prescribed, steady-state plasma efavirenz concentrations may be obtained to ensure therapeutic concentrations (~1 to 4 μg/mL). Among CYP2B6 IMs and PMs, prescribing efavirenz at 400 mg/day will almost certainly not reduce virologic efficacy, based on results of the ENCORE study in which treatment-naïve patients were randomized to initiate efavirenz-based regimens (combined with tenofovir and emtricitabine) at either 600 mg/day or 400 mg/day regardless of CYP2B6 genotype, and which showed that 400 mg/day was non-inferior (32).

TABLE 2.

EFAVIRENZ DOSING RECOMMENDATIONS BASED ON CYP2B6 PHENOTYPE IN CHILDREN ≥ 40 KG AND ADULT PATIENTS

| CYP2B6 phenotype | Implications for efavirenz pharmacologic measures | Therapeutic recommendations | Classification of recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2B6 ultrarapid metabolizer | Slightly lower dose-adjusted trough concentrations of efavirenz compared with normal metabolizers | Initiate efavirenz with standard dosing (600 mg/day) | Strong |

| CYP2B6 rapid metabolizer | Slightly lower dose-adjusted trough concentrations of efavirenz compared with normal metabolizers | Initiate efavirenz with standard dosing (600 mg/day) | Strong |

| CYP2B6 normal metabolizer | Normal efavirenz metabolism | Initiate efavirenz with standard dosing (600 mg/day) | Strongc |

| CYP2B6 intermediate metabolizer | Higher dose-adjusted trough concentrations of efavirenz compared with normal metabolizers; increased risk of CNS adverse events. | Consider initiating efavirenz with decreased dose of 400 mg/daya,b | Moderate |

| CYP2B6 poor metabolizer | Higher dose-adjusted trough concentrations of efavirenz compared with normal metabolizers; significantly increased risk of CNS adverse events and treatment discontinuation | Consider initiating efavirenz with decreased dose of 400 or 200 mg/daya,b | Moderate |

If therapeutic drug monitoring is available and a decreased efavirenz dose is prescribed, consider obtaining steady-state plasma efavirenz concentrations to ensure concentrations are in the suggested therapeutic range (~1 to 4 μg/mL).

To prescribe efavirenz at a decreased dose of 400 mg/day or 200 mg/day in a multidrug regimen may require prescribing more than one pill once daily. If so, the provider should weigh the potential benefit of reduced dose against the potential detrimental impact of increased pill number.

The ENCORE study showed that in treatment-naïve patients randomized to initiate efavirenz-based regimens (combined with tenofovir and emtricitabine), 400 mg/day was non-inferior to 600 mg/day regardless of CYP2B6 genotype (32).

CYP2B6 RMs and UMs may experience slightly lower dose-adjusted trough concentrations of efavirenz compared with normal metabolizers, which may be clinically important for efavirenz. However, based on current evidence, the effect of the increased function alleles CYP2B6*4 and *22 appears to be modest (27, 33–35). As such, current data are not sufficient to recommend a change from normal prescribing at this time, and patients with the RM or UM phenotype should receive standard efavirenz dosing. Of note, to define CYP2B6*4 requires documenting the absence of c.516G>T.

Pediatrics:

Efavirenz is FDA-approved for use as part of antiretroviral therapy in children ≥ 3 months of age and weighing ≥ 3.5 kg. In the U.S. efavirenz is available as capsules (50 or 200 mg); tablets (600 mg); a fixed dose combination comprised of efavirenz 600 mg, emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg; and more recently a fixed dose combination called Symfi Lo® (efavirenz 400 mg, lamivudine 300 mg, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg) for children weighing ≥ 35 kg. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection recommends efavirenz in combination with two-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) as an alternative non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) regimen for initial treatment of HIV in children aged ≥ 3 years (36).

Children age < 3 years.

Determining the optimal efavirenz dose for children < 3 years of age or weighing < 10 kg has been particularly challenging, as pharmacokinetic studies have shown a greater effect of genotype on efavirenz metabolism in young children due to high apparent clearance rates, especially among normal metabolizers (37). In this population, as with adults (Figure S1), the apparent clearance was reduced by 19% and 57% with CYP2B6 c.516G/T and c.516T/T genotypes, respectively, compared to c.516G/G. With respect to CYP2B6 ontogeny, CYP2B6 mRNA expression levels and CYP2B6 activity are very low during fetal development and approach adult levels by one year of age (38). Modeling based on data from a 24-week prospective cohort trial of efavirenz plus two NRTIs in HIV-positive children 3 months to less than 36 months of age predicted that FDA-approved doses would produce sub-therapeutic plasma concentrations in almost one third of children who are CYP2B6 normal (c.516G/G) or intermediate (c.516G/T) metabolizers and supratherapeutic plasma concentrations in more than 50% of children who are CYP2B6 poor (c.516T/T) metabolizers (39). Subtherapeutic concentrations in this population may also be confounded by poor absorption. Given these data, similar to DHHS guidelines, we do not recommend use of efavirenz in infants and children aged 3 months to < 3 years, except under special circumstances such as tuberculosis co-infection. If a clinical situation requires use of efavirenz in this age group, CYP2B6 testing may be informative and dosing could be guided by the current DHHS guidelines, which were informed by IMPAACT study P1070 (36). The guidelines recommended an efavirenz dose reduction based on weight groups for CYP2B6 poor (c.516T/T) metabolizers: 5 kg to < 7 kg: 50 mg; 7 kg to < 14 kg: 100 mg; 14 kg to < 17 kg: 150 mg; and ≥ 17 kg: 150 mg. Dosing for normal (c.516G/G) metabolizers and intermediate (c.516G/T) metabolizers is as follows: 5 kg to < 7 kg: 300 mg; 7 kg to < 14 kg: 400 mg; 14 kg to < 17 kg: 500 mg; and ≥ 17 kg: 600 mg. Although current DHHS guidelines for efavirenz dosing in pediatrics do not consider c.983T>C, we recommend that dosing recommendations for c.516T/T also be applied to c.516T/c.983C and to c.983C/C. We also recommend measuring plasma efavirenz concentrations two weeks after initiation. The mid-dose plasma efavirenz concentration target of 1 to 4 mg/L derived from adult clinical monitoring data is typically also applied to trough concentrations in pediatric patients.

Children age > 3 years and weighing < 40 kg.

While the effect of CYP2B6 genotype on efavirenz exposure has been demonstrated in children older than three years of age who weigh less than 40 kg, specific clinical data supporting CYP2B6 genotype-guided dosing are limited. Thus, although we cannot make a firm recommendation for dose adjustment based on CYP2B6 genotype in this age and weight group, CYP2B6 genotype almost certainly affects efavirenz exposure in these children such that efavirenz dose reduction in CYP2B6 poor metabolizers would also be reasonable. Therapeutic drug monitoring, where available and accessible, could help guide dosing adjustments in this age/weight group, especially in a setting of potential drug-related toxicity, virologic rebound, or lack of response in an adherent patient. For pediatric patients who weigh 40 kg or more, adult dosing applies (see Table 2).

Recommendations for Incidental Findings

Not applicable

Other Considerations

CYP2B6 rs4803419 (g.15582 C>T):

In a study involving 856 participants from several prospective clinical trials, and after controlling for both CYP2B6 c.516G>T and c.983T>C, increased plasma efavirenz concentrations were associated with CYP2B6 g.15582C>T (p = 4.4×10−15) (4). Other studies have not yet replicated this association for efavirenz, either because individual studies did not genotype this SNP, or because this SNP was infrequent in small studies of primarily African cohorts.

Implementation of this Guideline:

The guideline supplement and CPIC website (https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines/cpic-guideline-for-efavirenz-based-on-cyp2b6-genotype/) contains resources that can be used within electronic health records (EHRs) to assist clinicians in applying genetic information to patient care for the purpose of drug therapy optimization (see Resources to incorporate pharmacogenetics into an electronic health record with clinical decision support in the Supplemental Material).

POTENTIAL BENEFITS AND RISKS FOR THE PATIENT

The potential benefit of using CYP2B6 genotype data to guide efavirenz therapy is that patients with genotypes that predict higher dose-adjusted plasma exposure and adverse effects may be identified and prescribed a decreased dose that will decrease the likelihood of toxicity and treatment discontinuation while still achieving therapeutic plasma efavirenz concentrations. Risks include the potential for sub-therapeutic plasma efavirenz concentrations and treatment failure. As with any laboratory test, a possible risk to patients is an error in genotyping or phenotype prediction, which could have long-term adverse health implications for patients.

CAVEATS: APPROPRIATE USE AND/OR POTENTIAL MISUSE OF GENETIC TESTS

Rare CYP2B6 variants may not be included in the genotype test used, and patients with rare variants may be assigned an NM phenotype (CYP2B6*1/*1) by default. Thus, an assigned *1 allele could potentially harbor a decreased or no function variant. Therefore, it is important that test reports include information on which variant alleles were genotyped.

As with any diagnostic test, CYP2B6 genotype is just one factor that clinicians should consider when prescribing efavirenz.. It is important to consider that efavirenz is typically co-formulated in a fixed-dose combination tablet, which allows for one pill, once-daily dosing. If 400 mg or 200 mg doses of efavirenz are unavailable in a fixed-dose combination tablet, dose reduction may require prescribing two or three tablets daily, which not only increases pill burden, but also risk for non-adherence and virologic failure with drug-resistant virus. Another consideration is the impact of drug-drug interactions. For example, if co-administered with drugs that lower plasma efavirenz exposure (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, rifampin without isoniazid), it may be prudent to not further reduce efavirenz dose based on genotype. Although pregnancy does not substantially affect plasma efavirenz exposure (40), clinical judgment should be exercised if genotype-informed dose reduction is considered during pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the critical input of Dr. Mary Relling and members of the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) of the Pharmacogenomics Research Network, funded by the National Institutes of Health. CPIC members are listed here: https://cpicpgx.org/members/.

Funding:

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for CPIC (R24GM115264 and U24HG010135), PharmGKB (R24GM61374) and PharmVar (R24 GM123930). Additional grant funding included R01 AI077505, UM1 AI069439, UM1 AI106701, P30 AI110527, TR 002243 (DWH); UO1 HG007762, RO1 GM121707 and RO1 GM078501 (ZD); CAMH (RFT), a Canada Research Chair in Pharmacogenomics (RFT) and CIHR grant FDN-154294 (RFT); a European and Developing Countries Clinical Trial Partnership (EDCTP) grant TMA 20016-1508 PRACE TMA2016SF, a SANBIO/BiofisaII grant (CM).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

As an Associate Editor for Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, Rachel Tyndale was not involved in the review or decision process for this paper. All other authors declared no competing interests for this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: DISCLAIMER

Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines reflect expert consensus based on clinical evidence and peer-reviewed literature available at the time they are written and are intended only to assist clinicians in decision-making, as well as to identify questions for further research. New evidence may have emerged since the time a guideline was submitted for publication. Guidelines are limited in scope and are not applicable to interventions or diseases not specifically identified. Guidelines do not account for all individual variation among patients and cannot be considered inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of other treatments. It remains the responsibility of the health care provider to determine the best course of treatment for the patient. Adherence to any guideline is voluntary, with the ultimate determination regarding its application to be solely made by the clinician and the patient. CPIC assumes no responsibility for any injury to persons or damage to property related to any use of CPIC’s guidelines, or for any errors or omissions.

REFERENCES

- (1).CPIC. CPIC Guideline for Efavirenz based on CYP2B6 genotype <https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines/cpic-guideline-for-efavirenz-based-on-cyp2b6-genotype> (2018).

- (2).Hofmann MH et al. Aberrant splicing caused by single nucleotide polymorphism c.516G>T [Q172H], a marker of CYP2B6*6, is responsible for decreased expression and activity of CYP2B6 in liver. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325, 284–92 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zanger UM & Klein K Pharmacogenetics of cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6): advances on polymorphisms, mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Front Genet 4, 24 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Holzinger ER et al. Genome-wide association study of plasma efavirenz pharmacokinetics in AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocols implicates several CYP2B6 variants. Pharmacogenet Genomics 22, 858–67 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Manosuthi W, Sukasem C, Thongyen S, Nilkamhang S, Manosuthi S & Sungkanuparph S CYP2B6 18492T->C polymorphism compromises efavirenz concentration in coinfected HIV and tuberculosis patients carrying CYP2B6 haplotype *1/*1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58, 2268–73 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Sukasem C et al. Pharmacogenetics and clinical biomarkers for subtherapeutic plasma efavirenz concentration in HIV-1 infected Thai adults. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 29, 289–95 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sukasem C et al. Low level of efavirenz in HIV-1-infected Thai adults is associated with the CYP2B6 polymorphism. Infection 42, 469–74 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Manosuthi W et al. Impact of pharmacogenetic markers of CYP2B6, clinical factors, and drug-drug interaction on efavirenz concentrations in HIV/tuberculosis-coinfected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57, 1019–24 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Sukasem C et al. Pharmacogenetic markers of CYP2B6 associated with efavirenz plasma concentrations in HIV-1 infected Thai adults. Br J Clin Pharmacol 74, 1005–12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents <https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf> (2018). Accessed June 18 2018.

- (11).Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection <http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/208825/9789241549684_eng.pdf?sequence=1> (2016). Accessed June 18 2018.

- (12).McDonagh EM, Lau JL, Alvarellos ML, Altman RB & Klein TE PharmGKB summary: Efavirenz pathway, pharmacokinetics. Pharmacogenet Genomics 25, 363–76 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Belanger AS, Caron P, Harvey M, Zimmerman PA, Mehlotra RK & Guillemette C Glucuronidation of the antiretroviral drug efavirenz by UGT2B7 and an in vitro investigation of drug-drug interaction with zidovudine. Drug Metab Dispos 37, 1793–6 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).PharmGKB. Efavirenz pathway, pharmacokinetics <https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA166123135>. Accessed July 25 2018.

- (15).Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE et al. Compartment-specific gene regulation of the CAR inducer efavirenz in vivo. Clin Pharmacol Ther 92, 103–11 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ngaimisi E et al. Long-term efavirenz autoinduction and its effect on plasma exposure in HIV patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther 88, 676–84 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Marzolini C, Telenti A, Decosterd LA, Greub G, Biollaz J & Buclin T Efavirenz plasma levels can predict treatment failure and central nervous system side effects in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 15, 71–5 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Yimer G et al. High plasma efavirenz level and CYP2B6*6 are associated with efavirenz-based HAART-induced liver injury in the treatment of naive HIV patients from Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. Pharmacogenomics J 12, 499–506 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Abdelhady AM et al. Efavirenz Inhibits the Human Ether-A-Go-Go Related Current (hERG) and Induces QT Interval Prolongation in CYP2B6*6*6 Allele Carriers. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 27, 1206–13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Dooley KE et al. Pharmacokinetics of efavirenz and treatment of HIV-1 among pregnant women with and without tuberculosis coinfection. J Infect Dis 211, 197–205 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).McIlleron HM et al. Effects of rifampin-based antituberculosis therapy on plasma efavirenz concentrations in children vary by CYP2B6 genotype. AIDS 27, 1933–40 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Dooley KE et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic interactions of the antituberculous agent TMC207 (bedaquiline) with efavirenz in healthy volunteers: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5267. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 59, 455–62 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Robarge JD et al. Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling To Estimate the Contributions of Genetic and Nongenetic Factors to Efavirenz Disposition. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Mollan KR et al. Race/Ethnicity and the Pharmacogenetics of Reported Suicidality With Efavirenz Among Clinical Trials Participants. J Infect Dis 216, 554–64 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Rotger M et al. Influence of CYP2B6 polymorphism on plasma and intracellular concentrations and toxicity of efavirenz and nevirapine in HIV-infected patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics 15, 1–5 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ribaudo HJ et al. Effect of CYP2B6, ABCB1, and CYP3A5 polymorphisms on efavirenz pharmacokinetics and treatment response: an AIDS Clinical Trials Group study. J Infect Dis 202, 717–22 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rotger M et al. Predictive value of known and novel alleles of CYP2B6 for efavirenz plasma concentrations in HIV-infected individuals. Clin Pharmacol Ther 81, 557–66 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Gross R et al. CYP2B6 genotypes and early efavirenz-based HIV treatment outcomes in Botswana. AIDS 31, 2107–13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Cummins NW et al. Investigation of Efavirenz Discontinuation in Multi-ethnic Populations of HIV-positive Individuals by Genetic Analysis. EBioMedicine 2, 706–12 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Leger P et al. Pharmacogenetics of efavirenz discontinuation for reported central nervous system symptoms appears to differ by race. Pharmacogenet Genomics 26, 473–80 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Johnson DH et al. Neuropsychometric correlates of efavirenz pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics following a single oral dose. Br J Clin Pharmacol 75, 997–1006 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Group ES Efficacy of 400 mg efavirenz versus standard 600 mg dose in HIV-infected, antiretroviral-naive adults (ENCORE1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 383, 1474–82 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ariyoshi N et al. Q172H replacement overcomes effects on the metabolism of cyclophosphamide and efavirenz caused by CYP2B6 variant with Arg262. Drug Metab Dispos 39, 2045–8 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Desta Z et al. Impact of CYP2B6 polymorphism on hepatic efavirenz metabolism in vitro. Pharmacogenomics 8, 547–58 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zukunft J et al. A natural CYP2B6 TATA box polymorphism (-82T--> C) leading to enhanced transcription and relocation of the transcriptional start site. Mol Pharmacol 67, 1772–82 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection <https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/pediatricguidelines.pdf>. Accessed Dec 14 2018.

- (37).Saitoh A et al. Efavirenz pharmacokinetics in HIV-1-infected children are associated with CYP2B6-G516T polymorphism. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 45, 280–5 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Pearce RE et al. Developmental Expression of CYP2B6: A Comprehensive Analysis of mRNA Expression, Protein Content and Bupropion Hydroxylase Activity and the Impact of Genetic Variation. Drug Metab Dispos 44, 948–58 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Bolton Moore C et al. CYP2B6 genotype-directed dosing is required for optimal efavirenz exposure in children 3–36 months with HIV infection. AIDS 31, 1129–36 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Hill A, Ford N, Boffito M, Pozniak A & Cressey TR Does pregnancy affect the pharmacokinetics of efavirenz? AIDS 28, 1542–3 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.