Abstract

Gem-dimethylcyclobutanes are a common motif found in a multitude of natural products, and thus these structures have captivated synthetic chemists for years. However, until the turn of the century, most synthetic efforts relied upon the use of widely available terpenes, such as pinene or caryophyllene, that already contain the gem-dimethylcyclobutane motif. This approach limits the scope of molecules that can be accessed readily. This review highlights recent syntheses in which the gem-dimethylcyclobutane is assembled via de novo approaches. An outlook on the future of this research area is also provided.

1. Introduction

Almost one third of all naturally occurring cyclobutanes contain gem-dimethyl substitution.1 This structural motif can be found in a variety of classes of natural products, with the terpenes α-pinene and β-caryophyllene being the most prominent examples (see Scheme 1a).2 Biosynthetically, the genesis of gem-dimethylcyclobutanes can be traced back to geranyl pyrophosphate and/or its longer chain analogs, which ultimately originate from isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP).3 In nature, enzyme-mediated cationic cyclisations are believed to form a large percentage of these cyclobutanes; in some rare cases, light-promoted cycloadditions are also plausible. The gem-dimethylcyclobutane containing natural products can be further classified based on their proposed biosynthetic origin: natural products that derive from all-terpene precursors (terpenoids)4 and meroterpenes (terpene hybrids). The latter class is defined as structures that originate by pathways that are either intercepted by polyketide (PK) based fragments (PK-meroterpenoid)5 or by amino acid derived molecules (terpenoid-alkaloids).6 A representative example of each type of natural product is illustrated in Scheme 1b.

Scheme 1.

Biosynthetic overview and scope of this review.

The intriguing structure and, at times, interesting biological activity of gem-dimethylcyclobutane containing natural products has caught the attention of synthetic chemists for years. Early syntheses of molecules with this class typically relied on use of α/β-pinene or β-caryophyllene as a point of departure, which already contains the gem-dimethylcyclobutane motif. This approach can be limiting since extensive modification of the starting material may be necessary to arrive at the target structure. With advances in the assembly of cyclobutanes, novel approaches in pursuit of natural products containing a gem-dimethylcyclobutane have been developed. This review will cover recent syntheses (since 2000) that construct the gem-dimethylcyclobutane motif en route to the target molecule and organised according to the proposed biosynthetic origin (Scheme 1c). Syntheses based on chiral pool starting materials, such as α-pinene, and studies towards gem-dimethylcyclobutane natural products will only be mentioned in case they fit the context.7,8

2. Syntheses of sesquiterpene natural products

Sesquiterpenes make up the largest part of all-terpene based gem-dimethylcyclobutane containing natural products.4 Biosynthetically, they originate from farnesyl pyrophosphate, which undergoes a sequence of isomerisation, cyclisation, and/or rearrangement to form polycyclic structures. In the following section, recent strategies that generate the gem-dimethylcyclobutane en route to this diverse class of natural products will be discussed.

(−)-β-Caryophyllene

(−)-β-Caryophyllene can be found in numerous natural sources such as cloves,9 black pepper,10 and hops.11 Among many other bioactivities, (−)-β-caryophyllene has been described to have local anaesthetic activity.3,9,12 The complex bicyclo-[7.2.0]-undecane skeleton bearing an E-alkene moiety,13 makes β-caryophyllene itself an intriguing target for synthesis. While not discussed in this review, Corey’s first synthesis reported in 1963 assembled the gem-dimethylcyclobutane via a photochemical [2+2] cycloaddition between isobutene and cyclohexenone.14 Recently, the Corey group, among others,15 has investigated new strategies to access β-caryophyllene.16

In a recent synthesis by Corey and co-workers, Hajos-Parish-type ketone17 1 was converted into diol 2, which underwent Grob-fragmentation to provide cyclononadiene 3 (Scheme 2). The configurational stability of this nonadienone arose from restricted C-C bond rotation that prevents racemization even at room temperature. Treatment with trityl perchlorate and silyl ketene acetal 4 furnished neopentylic alcohol 5 in 84% yield. Regioselective deprotonation and SN2 displacement of preformed tosylate provided the gem-dimethylcyclobutane ring. Finally, Wittig methylenation afforded (−)-β-caryophyllene (6). Although (−)-β-caryophyllene can be easily accessed from natural sources, the synthesis illustrates an unconventional use of a chiral, configurationally stable cyclononadiene ring system.

Scheme 2.

Corey’s synthesis of β-caryophyllene. Ts = 4-toluenesulfonyl, py = pyridine, DIBAL = diisobutylaluminium.

(−)-Raikovenal

(−)-Raikovenal (8) is a sesquiterpenoid first isolated by Pietra and co-workers from marine ciliate Euplotes raikavi strains discovered on the Atlantic coast of Morocco.18 These ciliates presumably produce raikovenal to protect themselves against predators, as indicated by raikovenal’s toxicity dosages in the μg/mL range against Litonotus lamella cells. Biogenetically, it was proposed that (−)-raikovenal (8) originates from its putative precursor preraikovenal (7) by an enzyme-mediated cycloaddition (Scheme 3a). However, the possibility of a non-enzymatic photochemical process has not been excluded.19 Prior syntheses of raikovenal utilise both [2+2] photocycloadditions as well as cationic cyclisations.20 In 2008, Hsung and co-workers developed a Gassman-type21 cationic [2+2] cycloaddition to assemble the core structure of (±)-raikovenal ((±)-8) (Scheme 3b).22 Acetal 10, which derives from δ-enal 9, was subjected to FeCl3 at 0 °C to trigger the stepwise [2+2] cycloaddition. The authors proposed that the reaction preferentially proceeded via conformation 11b, which adopts a chair-like conformation and places the angular methyl group in the pseudo equatorial orientation. Reaction via conformation 11a is unfavourable due to adverse 1,3-diaxial interactions. Bicycle 12, which was formed in a 2:1 diastereomeric ratio, was further advanced to racemic raikovenal ((±)-8) through a series of straightforward transformations. This synthetic sequence highlights the power of biomimetic reaction planning, in which a cationic [2+2] cycloaddition assembles the key bicyclic structure, presumably closely related to the enzymatic process.

Scheme 3.

a) Pietra’s proposed biosynthetic origin of (−)-raikovenal; and b) Hsung’s synthesis of (±)-raikovenal.

(−)-Hebelophyllene E

(−)-Hebelophyllene E (19) is one of eight members of an unusual cis-fused class of caryophyllene-type sesquiterpenes.23 Their isolation from ectomycorrhizal fungi was achieved in the late 1990s by Ayer et al. According to several reports, these natural products have shown potential for conifer seedling protection.24 Brown and co-workers reported the first enantioselective synthesis of (−)-hebelophyllene E (19) in 2018 (Scheme 4).25 Key to success was an intermolecular Lewis-acid (15) catalysed [2+2] cycloaddition between benzyl allenoate (13) and alkene 14 to provide gem-dimethylcyclobutane 16. The reaction likely occurred via a concerted asynchronous [π2s+π2s+π2s] pathway as illustrated in Scheme 4. The chemoselectivity for cycloaddition occurring at the trisubstituted alkene, in preference to the terminal alkene, is due to a higher orbital coefficient at C3. While the reaction did proceed with high levels of diastereoselectivity, only moderate control of alkene geometry was observed, thus requiring separation of the isomers. Separation was crucial as the minor alkene isomer was formed with lower levels of diastereoselectivity. Subsequent reduction in presence of catalytic amounts of copper hydride afforded cyclobutane 18.26 It was found that the use of Josiphos-type ligand 17 was necessary for overriding the inherent substrate control and allowed for establishing the cis-substitution within the cyclobutane ring. Further manipulations, including lactonisation and installation of the α-methyl group furnished (−)-hebelophyllene E (19). This work showcases how late-stage implementation of a [2+2] cycloaddition to access the gem-dimethylcyclobutane with control of enantioselectivity can allow for efficient synthesis. In addition to completing the synthesis, Brown’s work also established the relative and absolute configuration of (-)-hebelophyllene E (19).

Scheme 4.

Brown’s total synthesis of (−)-hebelophyllene E.

(−)-Punctaporonin C

Isolated from the nail fungus Poronia punctata, the tetracyclic punctaporonins represent a structurally interesting family of natural products (Scheme 5).27,28 (−)-Punctaporonin C, the most structurally complex member of the punctaporonins, presumably derives from farnesyl pyrophosphate via the humulene cation (α-caryophyllene cation). Direct access to the gem-dimethylcyclobutane core via [2+2] photocycloaddition is challenging, since neither of the corresponding alkene starting materials has a suitable chromophore. Bach and Fleck developed a multistep-sequence to circumvent this obstacle (Scheme 5).29 The authors described an intramolecular photocycloaddition of tetronate 21, which was derived from known30 meso-epoxide 20. Moderate differentiation between the two vinyl groups was achieved by using a polar protic solvent at low temperature to favour formation of cycloadduct 23 over its regioisomer (not shown). Preferential formation of 23 in polar protic solvents was attributed to hydrogen bonding interactions of the acetate with solvent, increasing its size and preference for the psuedoequatorial position. This allowed for optimal arrangement of the two reacting alkenes as shown in 22. The authors demonstrated that use of non-polar solvents reversed the regioselectivity of this [2+2] cycloaddition, although with only modest preference. The gem-dimethyl substitution of intermediate 25 was introduced post-cycloaddition by α-methylation and subsequent reduction from ester 24. Further steps allowed for annulation of the seven-membered ring to ultimately deliver the target molecule ((±)-26). Both the power and limitations of photochemical [2+2] cycloadditions to assemble cyclobutanes are evident in this synthesis. The route must be designed around substrates with appropriate chromophores, thus limiting potential strategies. This challenge was elegantly overcome by the use of a tetronate subunit, which placed appropriate functionality on the cyclobutane to allow for introduction of the gem-dimethyl motif.

Scheme 5.

Bach’s synthesis of (±)-punctaporonin C. TBDMS = tertbutyldimethylsilyl, TIPS = triisopropylsilyl, Ac = acetyl, BOM = benzyloxymethyl, HMDS = hexamethyldisilazide, Ms = methanesulfonyl, DMPU = 1,3-dimethyltetrahydropyrimidin-2(1H)-one

(+)-Rumphellaone A/(−)-Birkenol, (+)-Birkenal, and (+)-Hushinone

The groups of Kuwahara and Echavarren independently synthesized (+)-rumphellaone A (27)31 and members of the birkenol family (28-30)31b, 32 through common intermediates 32 and 36 (Scheme 6). (+)-Rumphellaone A (27)33 was isolated among several other natural products34 from the gorgonian coral Rumphella antipathies. These terpenes display moderate cytotoxicity activity against human T-cell lymbophoblastic leukemia tumor cells. On the other hand, (−)-birkenol (28), (+)-birkenal (29), and (+)-hushinone (30) were first isolated by Klika and co-workers from essential oils of birch trees.35 This class of cyclobutane natural products potentially arise from light or heat-induced [1,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of β-caryophyllene itself, followed by a one carbon-degradation to give the unusual 14-carbon skeleton.

Scheme 6.

Kuwahara’s and Echavarren’s syntheses of rumphellaone A and several members of the birkenol family. IPr = 1,3-di-(2,6-isopropylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene.

Kuwahara’s strategy to generate the gem-dimethylcyclobutane intermediate 32 involves implementation of Stork’s36 4-exo-tet cyclisation of epoxynitrile 31, which was accessed through Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation (Scheme 6a). A poorly diastereoselective cyclisation was initially observed; however, this could be overcome by subsequent epimerisation to the thermodynamically favoured anti-arrangement (32) upon use of additional base and performing the reaction at elevated temperatures. Nitrile 32 served as a common intermediate for the synthesis of (+)-rumphellaone A (27),31c, 31d (−)-birkenol (28), (+)-birkenal (29), and (+)-hushinone (30).32

Echavarren and co-workers developed a gold-catalysed [2+2] cycloaddition between the aromatic alkyne and prenyl group of enantiomerically enriched ether 33 (Scheme 6b). The π-acidic gold complex activated the alkyne and triggered intermolecular stepwise [2+2] cycloaddition with the pendant alkene via a cyclopropyl gold carbene. The high diastereoselectivity (9:1) is remarkable given the distal stereocenter and flexible nature of the carbon chain, however a model rationalizing the observed selectivity was not proposed. Hydrogenation of the corresponding cyclobutene 34 and subsequent oxidative conversion of the tolyl group provided carboxylic acid 36, which was obtained in excellent yield over the two steps. The poor diastereoselectivity was inconsequential since downstream intermediates could be epimerised en route to (+)-rumphellaone A (27) and (+)-hushinone (30) in a similar fashion as described in Kuwahara’s sequence.31b In a subsequent report, Echavarren developed an enantioselective intermolecular [2+2] cycloaddition that accessed (+)-rumphellaone A (27) in only nine steps from alkene 38 and phenylacetylene (37).31a Key to the development of this method was the identification of Josiphos-type ligand 39, which allowed for the assembly of 40 in 70% yield and 91:9 er (likely via a similar cyclopropyl gold carbene as implicated in the conversion of 33 to 34). By application of this intermolecular gold-catalysed [2+2] cycloaddition, the authors were able to shorten the existing route to (+)-rumphellaone A (27) by a substantial margin, further emphasizing the importance of this methodology.

(+)-Pestalotiopsin A

(+)-Pestalotiopsin A (47) represents a highly oxygenated sesquiterpene, featuring a furan ring within the strained caryophyllene core. It was isolated in 1996 by Sugawara and co-workers from the endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis, which can be found on the bark and leaves of the pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia).37 The complex structure and immunosuppressive activity of pestalotiopsin A (47)38 has attracted attention among synthetic organic chemists as indicated by numerous reports.39

Tadano and co-workers reported the first total synthesis of pestalotiopsin A (47), which, in turn, allowed them to assign the absolute configuration of the natural product (Scheme 7). The enantioselective assembly of the gem-dimethylcyclobutane core employs Oppolzer’s camphorsultam (Xc) chiral auxiliary (41).40 Initially, a stepwise, Zr-catalysed [2+2] cycloaddition with ketene acetal 42 provided cyclobutene 43, which after conjugate reduction, diastereoselective protonation, and auxiliary removal furnished 44 in >97:3 er. Introduction of a cyano group and deprotection yielded cyclobutanone 45, which served as a precursor for the synthesis of bicyclic lactone 46 and ultimately (+)-pestalotiopsin A (47). This work is based on the identification of a [2+2] cycloaddition and subsequent auxiliary-controlled diastereoselective protonation that establishes the gem-dimethylcyclobutane early in the synthetic sequence.

Scheme 7.

Tadano’s synthesis of (+)-pestalotiopsin A. L-selectride= lithium tri-sec-butyl(hydrido)borate, DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine.

3. Synthesis of polyketide-derived meroterpenoids

Meroterpenoids are a class of natural products that are partially derived from terpenoid pathways. The prefix “mero-” (from Greek merus) means “part, partial, or fragment” and therefore, a myriad of secondary metabolites can be described as meroterpenoids.5,42 One of the larger groups of meroterpenoids are polyketide-terpenoid conjugates. These molecules typically arise from polyketide derived phenolic residues that intercept the terpene cyclisation pathway.43

Several meroterpenoids contain a gem-dimethylcyclobutane motif. One example, (+)-cytosporolide A (48),44 was synthesised by Tadano and co-workers through a biomimetic hetero Diels-Alder reaction of (−)-fuscoatrol A (50) with isochroman carboxylic acid 49 (Scheme 8, chromane = benzodihydropyran).45 The synthesis of fragment 50 relies on the same steps shown in Scheme 7.

Scheme 8.

Tadano’s synthesis of (+)-cytosporolide A from (−)-fuscoatrol A.

(+)-Psiguadial B

The small tree Psidium guajava, commonly found in tropical regions, has been used in folk medicine for its anti-inflammatory and hemostatic properties for centuries. In 2010, Shao and co-workers reported a new diformyl phloroglucinol-containing meroterpenoid, psiguadial B, which exhibits potent antiproliferative effects against the HepG2 human hepatoma cancer cell line (IC50 = 45.62 ± 1.41 nM).46

Biosynthetically, psiguadial B is proposed to be derived from a terpene-polyketide pathway in which β-caryophyllene intercepts a known Psidium guajava metabolite, 3,5-dimethyl-2,4,6-trihydroxybenzophenone,47 to furnish psiguadial B as well as many other isomeric natural products.48 Cramer49 and Lee50 have validated this biosynthetic hypothesis with syntheses utilising β-caryophyllene.

Reisman and co-workers developed the first enantioselective synthesis of (+)-psiguadial B (60) (Scheme 9), which involved a novel ring contraction.51,52 Irradiation of α-diazoketone 51 promoted a Wolff rearrangement53 that allowed for the in situ generation of ketene 54.54 While there are two potential mechanistic pathways for conversion of 54 to 56, a reasonable one involves stereoselective protonation of chiral C1 ammonium enolate 55 with 53. At this stage, Pd-catalysed coupling of 56 with vinyl iodide 57 provided cyclobutane 58 in 75% yield.55 Reduction of the amide with Schwartz reagent followed by epimerisation of the corresponding aldehyde with KOH afforded cyclobutane 59, and ultimately (+)-psiguadial B (60). This work showcases an interesting ring contraction approach toward gem-dimethylcyclobutanes that has potential for broader application as a strategy for synthesis.

Scheme 9.

Reisman’s synthesis of (+)-psiguadial B. TBME = tertbutyl methyl ether

Cannabinoids and cannabinoid-like chromanes

Cyclols belong to a diverse family of meroterpenoids characterised by a tricyclic terpene core that includes a dihydropyran, cyclopentane, and cyclobutane ring.56 Several cannabinoids, found in Cannabis sativa, also contain this cyclol motif and are referred to as cannabicyclols. The structure of these meroterpenoids was elucidated in the 1970s and lack typical psychotomimetic properties that other cannabinoids display.57 Apart from cannabinoids, other molecules that share the cyclol structure have been isolated from a variety of sources. Clusiacyclol A and B (64 and 65) were first isolated from the fruits of a Colombian species, Clusia multiflora.58 Eriobrucinol (66) has also been isolated from another flowering plant, Eriostemon brucei, native to western Australia.56, 59 Ranhuadujuanine A (71), isolated from Rhododendron anthopogonoides, has been reported to have inhibitory effects (IC50 = 83μM) of histamine release from peritoneal mast cells in rats.60 Biosynthetically, it is proposed that the cyclobutane motif found in these molecules is formed through a light-induced pathway from prenylated benzochromenes.56,61 In practice, formation of the cyclobutane ring of cyclols has been achieved photochemically, thermally, and under acid-catalysis (vide infra).

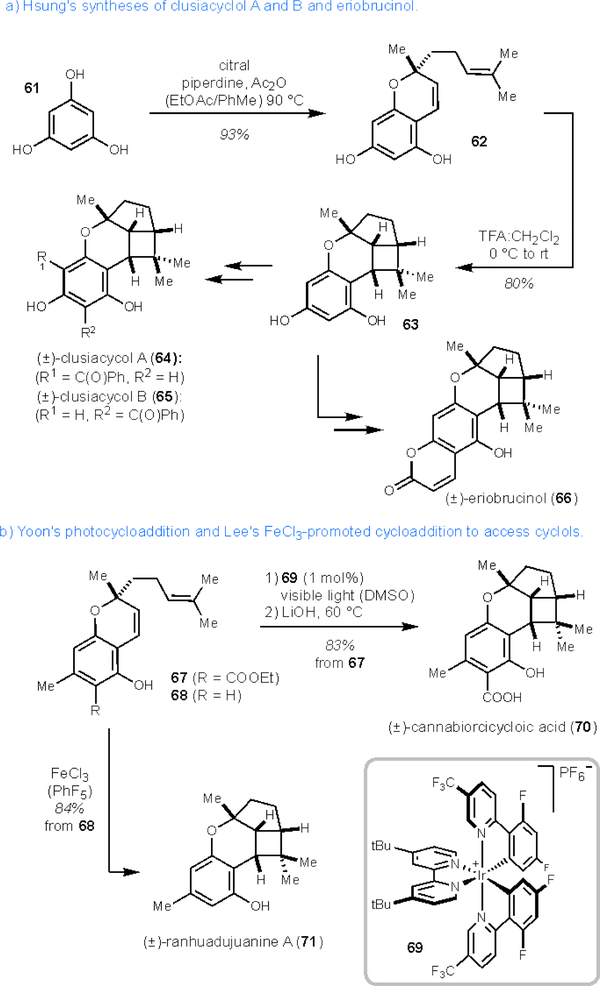

In 2013, Hsung and co-workers were able to construct chromanyl cyclobutane 63 via oxa-[3+3] cycloaddition of 1,3,5-trihydroxybenzene (61) with citral to access chromene 62, which then underwent stepwise cationic [2+2] cycloaddition upon treatment with acid.62,63 It is of note that the oxa-[3+3] annulation can proceed in tandem with the [2+2]-cycloaddition through minor modification of the described conditions. Cyclobutane 63 could be elaborated to clusiacycol A or B (64 or 65) via Lewis acid-controlled C-benzoylation, or eriobrucinol (66) by a Lewis acid-promoted annulation with ethyl propiolate (Scheme 10a). Utilising this strategy, Hsung was also able to synthesise iso-eriobrucinol A and B in addition to cannabicyclol.

Scheme 10.

Hsung’s, Yoon’s, and Lee’s syntheses of cannabinoids and other chromane meroterpenoids. DMSO = dimethyl sulfoxide

In 2012, Yoon and co-workers completed the synthesis of (±)-cannabiorcicyloic acid (70) from chromene 67 through a photosensitised [2+2] cycloaddition under visible light irradiation and subsequent hydrolysis in 83% yield.64 In contrast, irradiation at 254 nm provides the cycloadduct in low yield with concomitant decomposition of chromene 67.

Lee has also shown that FeCl3-promoted [2+2] cycloaddition of chromene 68 provides ranhuadujuanine A (71) in good yield (Scheme 10b).65 This reaction is likely a stepwise process similar to the conversion of 62 to 63. The versatility of this method allowed the authors to access other cannibinoids such as cannabicyclol66 and cannabicyclovarin. Both the photosensitised and Lewis/bronsted acid promoted cycloadditions allow for the construction of the gem-dimethylcyclobutane in high yields and showcase the ease with which this transformation occurs.

Artochamins H, I, and J

The family of molecules known as artochamins were isolated from Artocarpus chama, a species of tree found in tropical areas of Asia.67 The fruit, seeds, and timber of these trees have been used in folk medicines in Indonesia called ‘Jamu’ to treat malaria, fever, dysentery and tuberculosis. Specifically, three of the six members contain the unique gem-dimethylcyclobutane motif: artochamin I and J, which display cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells (IC50 = 49.04 and 48.99 μM respectively), and noncytotoxic artochamin H.68

In 2007, Nicolaou and co-workers reported the first synthesis of artochamins F, H, I, and J (Scheme 11).69 Inspired by the possible biogenetic relation between them, a prenylated stilbene was envisioned to serve as the precursor to the unique bicyclo[3.2.0]heptane system. It was speculated that the cyclobutane motif could be accessed through a cascade sequence under thermal conditions and further elaborated to various members of the family. Thus, two Claisen rearrangements of stilbene 72 followed by cleavage of the two Boc groups and oxidation with Ph3PO provided ortho-quinone intermediate 74 (via 73). The prenylated stilbene 74 underwent stepwise [2+2] cycloaddition to provide tetracyclic product 76 (via 75) in 55% yield and 5:1 diastereomeric ratio. Common intermediate 76 could then be advanced to artochamin H (78), I (79), and J (77).69b Nicolaou’s syntheses of artochamins H, I, and J demonstrate how the rapid build-up of molecular complexity can be achieved with cascade reactions.

Scheme 11.

Nicolaou and co-workers synthesis of artochamin H, I, and J via cascade reaction. Boc = C(O)OtBu

4. Synthesis of alkaloid-terpenoid natural products

Many cyclobutane-containing alkaloids have been isolated from plants, with a few reports of isolation from marine organisms.70 This class of molecules is derived from amino acids, or amino acid fragments, that intercept the terpene biosynthetic pathway. Although gem-dimethyl substitution of cyclobutanes is uncommon in terpenoid-alkaloids, welwitindolinone A isonitrile is a notable exception.

Welwitindolinone A Isonitrile

(+)-Welwitindolinone A isonitrile ((+)-83) is one of many oxindole-containing alkaloids originating from the cyanobacteria Stigonemataceae. First isolated in 1984 by Moore and co-workers, the scaffold contains a highly functionalised spirocyclic cyclobutane oxindole core, and is the only chlorinated member of this class of alkaloids.71 In addition to the unique structure, the molecule has shown antifungal activity and is proposed to be a biosynthetic precursor to welwitindolinones B-D.71b, 72

The first reported synthesis was by Baran and was based on an alternative biosynthetic proposal in which welwitindolinone A isonitrile could arise from epi-fischerindole I (80).73 Their synthesis of (+)-welwitindolinone A isonitrile ((+)-83) successfully implemented an oxidative ring contraction,74 despite concerns about the feasibility of such a transformation (Scheme 12a).75 It was discovered that treatment of previously synthesized epi-fischerindole I (80) with XeF2 promoted a [1,5]-sigmatropic rearrangement of azaortho-quinodimethane 82 from fluorinated-indole 81 to provide (+)-welwitindolinone A isonitrile (83) in 55% yield. Due to the facility with which the ring contraction takes place, the authors speculate that a similar process may be involved in the biosynthesis.

Scheme 12.

Baran’s and Wood’s total syntheses of welwindolinone A isonitrile.

Shortly after, Wood and co-workers reported an alternative strategy to access the spirocyclic cyclobutane moiety (Scheme 12b).76 Readily available cyclohexadiene acetonide 84 underwent stereo- and regioselective [2+2] cycloaddition to afford cyclobutanone 85 in 85% yield. Diastereoselective addition of ortho-metallated aniline 86 provided aryl alcohol 87.77 To complete the functionalization of the cyclobutane, treatment of 88 with COCl2 generated isocyano-isocyanate 89. The crude material was then subjected to LiHMDS and resulted in formation of (±)-welwitindolinone A isonitrile ((±)-83) to complete the bold late-stage cascade sequence.

The two syntheses of welwitindolinone A isonitrile employ different approaches with respect to the assembly of the gem-dimethylcyclobutane motif. Baran utilised a late-stage oxidative ring contraction in which the chemo- and diastereo-selectivity of fluorination by XeF2 was critical for the [1,5]-sigmatropic rearrangement. Wood targeted the molecule with a different approach that took advantage of early-stage ketene-alkene [2+2]-cycloaddition. Comparison of both strategies showcases the impact of a biomimetic design as well as the robust nature of ketene-alkene [2+2] cycloadditions.

5. Conclusions

The syntheses outlined in this review illustrate the diverse family of gem-dimethylcyclobutane containing natural products that can be accessed by an assorted repertoire of strategies for cyclobutane assembly. Analysis of the routes described reveal cyclisations, ring contractions, and [2+2] cycloadditions as the three major strategies to construct the cyclobutane. Ring contraction can provide unique opportunities for synthesis, beautifully demonstrated by Reisman’s and Baran’s syntheses of psiguadial B and welwitindolinone A isonitrile, respectively, but design of the precursor is not always straightforward. Cyclisations have been used in the Corey synthesis of caryophyllene (Scheme 2) and the Kuwahara approach towards (+)-rumphellaone A and derivatives (Scheme 6a). These sequences can be efficient; however, multistep construction of the cyclobutane can be required in which each bond is formed through separate transformations (Scheme 2). However, judicious selection of the starting material can provide more efficient sequences (Scheme 6a). The [2+2] cycloaddition disconnection can be advantageous for implementing a convergent synthesis of the target natural product in an atom-economical fashion from simple alkene and/or alkyne starting materials. Despite the rapid build-up of structural complexity, [2+2] cycloadditions still have limitations. Many methods rely on cycloadditions that proceed via a stepwise mechanism, which can make control of diastereoselectivity challenging. Photochemical methods described in this review provide an elegant strategy, but the synthesis must be structured around a substrate that has a suitable chromophore as exemplified by Bach’s synthesis of punctaporonin C (Scheme 5). To utilize a substrate with an appropriate chromphore, the gem-dimethyl substitution had to be installed post cycloaddition, adding additional steps. Catalytic enantioselective variants bear great potential in synthesis and have already been utilized by Echavarren and Brown in their routes to rumphellaone A (Scheme 6b) and hebelophyllene E (Scheme 4), respectively. However, the use of protecting groups is common and the selectivities are far from ideal. Use of olefin partners that are not greatly restricted based on substitution or electronic properties as well as increasing functional group tolerance are logical next steps in the development of enantioselective [2+2] cycloaddition reactions.

Finally, while innovations in de novo approaches to gem-dimethylcyclobutanes will undoubtedly lead to improved syntheses, we also expect a continued reliance on strategies that utilize chiral pool starting materials (e.g., α-pinene and β-caryophyllene), especially given emerging innovations in selective C-H functionalization. This latter strategy will enable tailoring of chiral pool materials to provide more appropriately substituted building blocks. Overall, due to the prevalence of gem-dimethylcyclobutane containing natural products, these targets will continue to be used as inspiration for the development of innovative methods and strategies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Indiana University and the National Institutes of Health (R01GM110131) for financial support. The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (WI 4933/1–2) is acknowledged for postdoctoral fellowship support to J.M.W.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Literature search performed on https://www.reaxys.com/#/search/quick, 28 September 2018.

- 2.Rilling HC and Poulter CD, in Biosynthesis of Isoprenoid Compounds, eds. Porter JW and Spurgeon SL, Wiley, New York, 1981, vol. 1, pp. 161–224. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isoprenoids, Including Carotenoids and Steroids, Elsevier, Oxford, 1999. Vol.2 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cane DE, Chem. Rev, 1990, 90, 1089–1103. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geris R and Simpson TJ, Nat. Prod. Rep, 2009, 26, 1063–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherney EC and Baran PS, Isr. J. Chem, 2011, 51, 391–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. (a).Lovchik MA, Fráter G, Goeke A and Hug W, Chem. Biodiversity, 2008, 5, 126–139; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Erden I and Watson SE, Tetrahedron Lett, 2016, 57, 237–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. (a).Faure S and Piva O, Tetrahedron Lett, 2001, 42, 255–259; [Google Scholar]; (b) Paduraru MP and Wilson PD, Org. Lett, 2003, 5, 4911–4913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghelardini C, Galeotti N, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Mazzanti G and Bartolini A, Il Farmaco, 2001, 56, 387–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jirovetz L, Buchbauer G, Ngassoum MB and Geissler M, J. Chromatogr. A, 2002, 976, 265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang G, Tian L, Aziz N, Broun P, Dai X, He J, King A, Zhao PX and Dixon RA, Plant Physiol, 2008, 148, 1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collado IG, Hanson JR and Macías-Sánchez AJ, Nat. Prod. Rep, 1998, 15, 187–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. (a).Dawson TL and Ramage GR, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun, 1951, 3382–3386; [Google Scholar]; (b) Robertson JM and Todd G, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun, 1955, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar]

- 14. (a).Corey EJ, Mitra RB and Uda H, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1964, 86, 485–492; [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Mitra RB and Uda H, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1963, 85, 362–363. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowling MS and Vanderwal CD, J. Org. Chem, 2010, 75, 6908–6922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larionov OV and Corey EJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2008, 130, 2954–2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajos ZG and Parrish DR, J. Org. Chem, 1974, 39, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guella G, Dini F, Erra F and Pietra F, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun, 1994, 2585–2586. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guella G, Pietra F and Dini F, Helv. Chim. Acta, 1995, 78, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar]

- 20. (a).Snider BB and Lu Q, Synth. Commun, 1997, 27, 1583–1600; [Google Scholar]; (b) Rosini G, Laffi F, Marotta E, Pagani I and Righi P, J. Org. Chem, 1998, 63, 2389–2391. [Google Scholar]

- 21. (a).Gassman PG, Chavan SP and Fertel LB, Tetrahedron Lett, 1990, 31, 6489–6492; [Google Scholar]; (b) Gassman PG and Lottes AC, Tetrahedron Lett, 1992, 33, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko C, Feltenberger JB, Ghosh SK and Hsung RP, Org. Lett, 2008, 10, 1971–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. (a).Wichlacz M, Ayer WA, Trifonov LS, Chakravarty P and Khasa D, J. Nat. Prod, 1999, 62, 484–486; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wichlacz M, Ayer WA, Trifonov LS, Chakravarty P and Khasa D, Phytochemistry, 1999, 51, 873–877; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wichlacz M, Ayer WA, Trifonov LS, Chakravarty P and Khasa D, Phytochemistry, 1999, 52, 1421–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. (a).Boyle CD, Robertson WJ and Salonius PO, Can. J. For. Res, 1987, 17, 1480–1486; [Google Scholar]; (b) Boyle CD and Hellenbrand KE, Can. J. Botany, 1991, 69, 1764–1771. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiest JM, Conner ML and Brown MK, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2018, 57, 4647–4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. (a).Conner ML, Xu Y and Brown MK, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2015, 137, 3482–3485; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu Y, Hong YJ, Tantillo DJ and Brown MK, Org. Lett, 2017, 19, 3703–3706; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wiest JM, Conner ML and Brown MK, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 15943–15949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. (a).Anderson JR, Edwards RL, Poyser JP and Whalley AJS, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1, 1988, 823–831; [Google Scholar]; (b) Anderson JR, Edwards RL, Freer AA, Mabelis RP, Poyser JP, Spencer H and Whalley AJS, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun, 1984, 917–919. [Google Scholar]

- 28. (a).Paquette LA and Sugimura T, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1986, 108, 3841–3842; [Google Scholar]; (b) Sugimura T and Paquette LA, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1987, 109, 3017–3024; [Google Scholar]; (c) Kende AS, Kaldor I and Aslanian R, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1988, 110, 6265–6266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. (a).Fleck M and Bach T, Chem. Eur. J, 2010, 16, 6015–6032; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fleck M and Bach T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2008, 47, 6189–6191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleck M, Yang C, Wada T, Inoue Y and Bach T, Chem. Commun, 2007, 822–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. (a).García-Morales C, Ranieri B, Escofet I, López-Suarez L, Obradors C, Konovalov AI and Echavarren AM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 13628–13631; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ranieri B, Obradors C, Mato M and Echavarren AM, Org. Lett, 2016, 18, 1614–1617; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hirokawa T, Nagasawa T and Kuwahara S, Tetrahedron Lett, 2012, 53, 705–706; [Google Scholar]; (d) Hirokawa T and Kuwahara S, Tetrahedron, 2012, 68, 4581–4587. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirokawa T and Kuwahara S, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2013, 2780–2782. [Google Scholar]

- 33. (a).Chung H-M, Chen Y-H, Lin M-R, Su J-H, Wang W-H and Sung P-J, Tetrahedron Lett, 2010, 51, 6025–6027; [Google Scholar]; (b) Chung H-M, Wang W-H, Hwang T-L, Li J-J, Fang L-S, Wu Y-C and Sung P-J, Molecules, 2014, 19, 12320–12327; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chung H-M, Wang W-H, Hwang T-L, Fang L-S, Wen Z-H, Chen J-J, Wu Y-C and Sung P-J, Mar. Drugs, 2014, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. (a).Chuang L-F, Fan T-Y, Li J-J and Sung P-J, Biochem. Syst. Ecol, 2007, 35, 470–471; [Google Scholar]; (b) Chung H-M, Hwang T-L, Chen Y-H, Su J-H, Lu M-C, Chen J-J, Li J-J, Fang L-S, Wang W-H and Sung P-J, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn, 2010, 84, 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- 35. (a).Klika KD, Demirci B, Salminen J-P, Ovcharenko VV, Vuorela S, Başer KHC and Pihlaja K, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2004, 2627–2635; [Google Scholar]; (b) Başer KHC and Demirci B, ARKIVOC, 2007, 335–348. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stork G and Cohen JF, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1974, 96, 5270–5272. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pulici M, Sugawara F, Koshino H, Uzawa J, Yoshida S, Lobkovsky E and Clardy J, J. Org. Chem, 1996, 61, 2122–2124. [Google Scholar]

- 38. (a)).Pulici M, Sugawara F, Koshino H, Okada G, Esumi Y, Uzawa J and Yoshida S, Phytochemistry, 1997, 46, 313–319 [Google Scholar]; (b) Magnan Rodrigo F, Rodrigues-Fo E, Daolio C, Ferreira AG and Souza Antonia Q. L. d., Z. Naturforsch., C: J. Biosci, 2003, 58, 319; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Deyrup ST, Swenson DC, Gloer JB and Wicklow DT, J. Nat. Prod, 2006, 69, 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. (a).Johnston D, Francon N, Edmonds DJ and Procter DJ, Org. Lett, 2001, 3, 2001–2004; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnston D, Couché E, Edmonds DJ, Muir KW and Procter DJ, Org. Bio. Chem, 2003, 1, 328–337; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Edmonds DJ, Muir KW and Procter DJ, J. Org. Chem, 2003, 68, 3190–3198; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Paquette LA and Cunière N, Org. Lett, 2002, 4, 1927–1929; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Dong S, Parker GD, Tei T and Paquette LA, Org. Lett, 2006, 8, 2429–2431; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Paquette LA, Parker GD, Tei T and Dong S, J. Org. Chem, 2007, 72, 7125–7134; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Paquette LA, Dong S and Parker GD, J. Org. Chem, 2007, 72, 7135–7147; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Dong S and Paquette LA, Heterocycles, 2007, 72, 111–114; [Google Scholar]; (i) Takao K.-i., Saegusa H, Tsujita T, Washizawa T and Tadano K.-i., Tetrahedron Lett, 2005, 46, 5815–5818; [Google Scholar]; (j) Maulide N and Markó IE, Chem. Commun, 2006, 1200–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heravi MM and Zadsirjan V, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2014, 25, 1061–1090. [Google Scholar]

- 41. (a).Wessjohann LA and Scheid G, Synthesis, 1999, 1999, 1–36; [Google Scholar]; (b) Fürstner A, Chem. Rev, 1999, 99, 991–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsuda Y and Abe I, Nat. Prod. Rep, 2016, 33, 26–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.While many meroterpenoids can be classified as polyketide-terpenoids or non-polyketide-terpenoids, this family of natural products is very structurally diverse. Cytokinins, phenylpropanoids, and alkaloids containing isoprenoid residues are included in this class of molecules. See ref. 42 for more information and subsequent references.

- 44.Takao K.-i., Noguchi S, Sakamoto S, Kimura M, Yoshida K and Tadano K.-i., J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2015, 137, 15971–15977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng X, Harzdorf NL, Shaw T and Siegel D, Org. Lett, 2010, 12, 1304–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao M, Wang Y, Liu Z, Zhang D-M, Cao H-H, Jiang R-W, Fan C-L, Zhang X-Q, Chen H-R, Yao X-S and Ye W-C, Org. Lett, 2010, 12, 5040–5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shao M, Wang Y, Jian Y-Q, Huang X-J, Zhang D-M, Tang Q-F, Jiang R-W, Sun X-G, Lv Z-P, Zhang X-Q and Ye W-C, Org. Lett, 2012, 14, 5262–5265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. (a).Yang X-L, Hsieh K-L and Liu J-K, Org. Lett, 2007, 9, 5135–5138; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fu H-Z, Luo Y-M, Li C-J, Yang J-Z and Zhang D-M, Org. Lett, 2010, 12, 656–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newton CG, Tran DN, Wodrich MD and Cramer N, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2017, 56, 13776–13780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawrence AL, Adlington RM, Baldwin JE, Lee V, Kershaw JA and Thompson AL, Org. Lett, 2010, 12, 1676–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. (a).Hodous BL and Fu GC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2002, 124, 10006–10007; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wiskur SL and Fu GC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2005, 127, 6176–6177; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) France S, Wack H, Taggi AE, Hafez AM, Wagerle TR, Shah MH, Dusich CL and Lectka T, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2004, 126, 4245–4255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. (a).Chapman LM, Beck JC, Lacker CR, Wu L and Reisman SE, J. Org. Chem, 2018, 83, 6066–6085; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chapman LM, Beck JC, Wu L and Reisman SE, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 9803–9806; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kinebuchi M, Uematsu R and Tanino K, Tetrahedron Lett, 2017, 58, 1382–1386. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghosh A, Banerjee UK and Venkateswaran RV, Tetrahedron, 1990, 46, 3077–3088. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banerjes UK and Venkateswaran RV, Tetrahedron Lett, 1983, 24, 423–424. [Google Scholar]

- 55. (a).Shabashov D and Daugulis O, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2010, 132, 3965–3972; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reddy BVS, Reddy LR and Corey EJ, Org. Lett, 2006, 8, 3391–3394; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Corbet M and De F Campo, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2013, 52, 9896–9898; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yamaguchi J, Yamaguchi AD and Itami K, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2012, 51, 8960–9009; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Gutekunst WR and Baran PS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2011, 133, 19076–19079; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Gutekunst WR, Gianatassio R and Baran PS, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2012, 51, 7507–7510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bukuru J, Nguyen Van T, Van Puyvelde L, He W and De Kimpe N, Tetrahedron, 2003, 59, 5905–5908. [Google Scholar]

- 57. (a).Gaoni Y and Mechoulam R, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1971, 93, 217–224; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Turner CE, Elsohly MA and Boeren EG, J. Nat. Prod, 1980, 43, 169–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonzalez JG, Olivares EM and Monache FD, Phytochemistry, 1995, 38, 485–489. [Google Scholar]

- 59. (a).Jefferies PR and Worth GK, Tetrahedron, 1973, 29, 903–908; [Google Scholar]; (b) Rashid MA, Armstrong JA, Gray AI and Waterman PG, Phytochemistry, 1992, 31, 3583–3588. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iwata N and Kitanaka S, Chem. Pharm. Bull, 2011, 59, 1409–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crombie L, Ponsford R, Shani A, Yagnitinsky B and Mechoulam R, Tetrahedron Lett, 1968, 9, 5771–5772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mondal M, Puranik VG and Argade NP, J. Org. Chem, 2007, 72, 2068–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yeom H-S, Li H, Tang Y and Hsung RP, Org. Lett, 2013, 15, 3130–3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lu Z and Yoon TP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2012, 51, 10329–10332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li X and Lee YR, Org. Bio. Chem, 2014, 12, 1250–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. (a).Kane VV and Razdan RK, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1968, 90, 6551–6553; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Crombie L and Ponsford R, Chem. Commun. (London), 1968, 894–895; [Google Scholar]; (c) Crombie L and Crombie WML, Phytochemistry, 1975, 14, 213–220; [Google Scholar]; (d) Crombie L and Ponsford R, J. Chem. Soc. C, 1971, 796–804. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Y-H, Hou A-J, Chen L, Chen D-F, Sun H-D, Zhao Q-S, Bastow KF, Nakanish Y, Wang X-H and Lee K-H, J. Nat. Prod, 2004, 67, 757–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Y-H, Hou A-J, Chen D-F, Weiller M, Wendel A and Staples RJ, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2006, 3457–3463. [Google Scholar]

- 69. (a).Nicolaou KC, Lister T, Denton RM and Gelin CF, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2007, 46, 7501–7505; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Lister T, Denton RM and Gelin CF, Tetrahedron, 2008, 64, 4736–4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. (a).Dembitsky VM, J. Nat. Med, 2008, 62, 1–33; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sergeiko A, Poroikov VV, Hanuš LO and Dembitsky VM, Open Med. Chem. J, 2008, 2, 26–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. (a).Jimenez JI, Huber U, Moore RE and Patterson GML, J. Nat. Prod, 1999, 62, 569–572; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stratmann K, Moore RE, Bonjouklian R, Deeter JB, Patterson GML, Shaffer S, Smith CD and Smitka TA, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1994, 116, 9935–9942. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patterson GML, Larsen LK and Moore RE, J. Appl. Phycol, 1994, 6, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- 73. (a).Baran PS and Richter JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2005, 127, 15394–15396; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Richter JM, Ishihara Y, Masuda T, Whitefield BW, Llamas T, Pohjakallio A and Baran PS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2008, 130, 17938–17954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Witkop B and Patrick JB, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1953, 75, 2572–2576. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wenkert E, Moeller PDR, Piettre SR and McPhail AT, J. Org. Chem, 1987, 52, 3404–3409. [Google Scholar]

- 76. (a).Ready JM, Reisman SE, Hirata M, Weiss MM, Tamaki K, Ovaska TV and Wood JL, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2004, 43, 1270–1272; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reisman SE, Ready JM, Hasuoka A, Smith CJ and Wood JL, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2006, 128, 1448–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoppe D, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl, 1974, 13, 789–804. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA, Montagnon T and Vassilikogiannakis G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2002, 41, 1668–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. (a).Xu Y, Conner ML and Brown MK, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 11918–11928; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Poplata S, Tröster A, Zou Y-Q and Bach T, Chem. Rev, 2016, 116, 9748–9815; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang M and Lu P, Organic Chemistry Frontiers, 2018, 5, 254–259. [Google Scholar]