Abstract

While serum anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) levels are inversely associated with all-cause mortality in men, the underlying mechanisms are unclear. Elevated levels of inflammation, also associated with all-cause mortality, and may be the link between AMH and mortality. Hence, we examined the association of AMH with serum c-reactive protein (CRP), a biomarker of inflammation, in men. We included men ≥20 years from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1999–2004). We used survey weight-adjusted linear regression to examine the association between AMH and CRP without and with adjustment for age, race, body mass index (BMI), smoking, hypertension, diabetes, cholesterol, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), testosterone, androstenedione, and sex hormone binding globulin. Of the 949 men, 212 (22%) were elderly, 493 (52%) Caucasian, 254 (27%) current smokers, 100 (10%) diabetics, and 312 (33%) had hypertension. Mean (SD) AMH was 8.4 (7.2) ng/mL and median (IQR) CRP level was 0.17 (3) mg/L. Using linear regression, each 10 ng/mL rise in AMH was associated with 0.09 mg/dL (95%CI = −0.14 to −0.03; p = 0.002) decrease before and 0.08 mg/dL (95%CI = −0.13 to −0.02; p = 0.004) decrease in CRP after adjusting for potential confounders. Similarly, men in the highest quartile of AMH had significantly lower CRP compared to those in the lowest quartile (unadjusted difference = −0.19 mg/dL; 95%CI = −0.31 to −0.06; p = 0.006, adjusted difference = −0.16 mg/dL; 95%CI = −0.3 to −0.01; p = 0.035). We found an independent, robust, and inverse association between CRP and AMH in men. Effect of AMH on mortality may be through amelioration of inflammation.

Subject terms: Predictive markers, Risk factors

Introduction

Anti-mullerian hormone (AMH), is a glycoprotein belonging to the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) superfamily. It is highly expressed in male fetal testis where it is responsible for regression of the mullerian duct. AMH remains elevated until puberty in men and rapidly declines during transition to the adulthood1,2. While the role of the persistence of AMH during adulthood is unclear, the presence of AMH-specific receptor (AMHRII) in several organs (such as adrenal gland, liver, lung, skeletal muscle, and spleen) suggests that AMH may play a role during adult life beyond the development of reproductive system3. In fact, epidemiological studies have demonstrated that serum AMH levels were inversely associated with cardiovascular events in elderly male, with infra-renal aortic diameter, and with all-cause mortality in men4–6. However, the mechanisms underlying of these associations are not known.

Growing body of evidence suggests that inflammation plays a critical role in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis, chronic pulmonary disease (including COPD), and malignancy7–9. Several studies have reported that serum c-reactive protein (CRP), an inflammatory biomarker, has the ability to predict cardiovascular disease, lung disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality risk in general population10,11. In one study, serum AMH levels were negatively associated with interleukin-6 level, an inflammatory cytokine, in men12. Therefore, we hypothesized that AMH and inflammation, and hence CRP, may be inversely associated with one another based on their proposed effects on clinical outcomes and aimed to examine this association between AMH and CRP in a large cohort of men.

Methods

We used the publicly-available National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) data to explore the relationship between AMH and CRP levels. NHANES is a complex, multistage, probability sampling series of surveys of the noninstitutionalized United States population with a goal to determine population’s health and nutritional status. The surveys oversample participants from certain population subgroups, such as African-Americans and Mexican-Americans, to ensure precision and reliability of estimates. Detailed methods of surveys are available on the NHANES website (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm). All participants provided informed consent and National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board approved all protocols.

The three NHANES continuous cycles (1999–2000, 2001–2002, 2003–2004), which were included in our study, had serum AMH levels measured in approximately 1/3 subsample of men. These men were selected based on availability of stored samples. Individuals <20 years of age or with missing AMH or CRP data were excluded. Data on age, sex, and gender were collected through self-report by study participants. Participants were subcategorized into three age groups (young =≤ 35 years, middle-age => 35 & <65 years, and elderly =≥ 65 years). We categorized participants as smokers if they were actively smoking at baseline, ever smokers if they had ever smoked ≥100 cigarettes during their lifetime, and nonsmokers if they had never smoked. We calculated BMI by dividing body weight (in kilograms) with height (in meters squared). We categorized participants as hypertensives if their systolic blood pressure was >140 mm Hg, if their diastolic blood pressure was >90 mm Hg, if they had history of hypertension, or if they were taking antihypertensive medications. We inferred the presence of diabetes mellitus if participants had a prior diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, were taking insulin or other oral medication for the blood glucose management, had hemoglobin A1C >7.0%, or had a blood glucose level >200 mg/dl.

Serum AMH levels were measured on frozen stored samples using AMH Gen II ELISA (Beckman Coulter, USA) apparatus that has coefficient of variation of <10% and uses an enzymatically amplified two-site immunoassay13. Serum CRP levels were measured using nephlometer (Behring Nephelometer, Germany). Serum creatinine levels were measured using the Jaffe rate method (kinetic alkaline picrate). We estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) using Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation14. Serum glucose was measured using Beckman Synchron LX20 (Beckman Coulter, Brea, Calif) and hemoglobin A1C was measured using the Primus CLC300 (Primus Corporation, Kansas City, MO). Sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), estradiol, and total testosterone were measured using immunoassays based on emitted chemiluminescence. Androstenedione was measured by first, mixing patient samples containing unlabeled antigen with enzyme labeled antigen then, removing unbound materials and finally, measuring absorbance.

All analyses were performed using appropriate adjustments to survey weights for the 3- cycles of the NHANES. The sampling weights reflect the complex survey sampling method and were assigned to each person to account for the unequal probability of selection and nonresponse. In analyses, serum AMH was included as continuous variable and after dividing into quartiles. Relationships between categorical variables were calculated using Pearson’s Chi-square test. Relationships between continuous variables and AMH quartiles were examined using Student’s t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis’ rank test as appropriate. Survey weight-adjusted linear regression was conducted to examine the association of AMH with CRP without and with adjustment for potential confounders. We used a p-value of <0.05 as statistically significant. Multiple linear regression analyses were adjusted for age, race, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, smoking status, total cholesterol, estimated GFR, serum total testosterone, SHBG, and androstenedione. All analyses were performed on Stata/MP version 14.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas).

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was taken from each participant for both the in-home interview and the health exam during the survey.

Results

Of the 949 men, 212 (22%) were elderly, 493 (52%) were Caucasian, 254 (27%) current smokers, 100 (10%) were diabetics, and 312 (33%) had hypertension. Mean (SD) AMH was 8.4 (7.2) ng/mL and median (IQR) CRP level was 0.17 (3) mg/dL. When comparing the lowest quartile of AMH (1.9 [1.1] ng/mL) with the highest quartile (18.6[7.6] ng/mL), the later had more young men, lower BMI, and fewer Caucasians, diabetics, and hypertensives (all P < 0.001; Table 1). Elderly participants had higher CRP levels (geometric mean: 0.22 mg/dL) compared to middle-age and young participants (geometric mean: 0.21 and 0.13 mg/dL, respectively, all p-values < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in CRP levels between Caucasians and non-Caucasians (geometric mean: 0.17 vs. 0.17 mg/dL; p = 0.78). Serum CRP levels were higher in current smokers than in ever-smokers or non-smokers (geometric means: 0.20, 0.18 and 0.14 mg/dL, respectively; p = 0.001), in diabetics than in non-diabetics (geometric mean: 0.3 vs. 0.2 mg/dL; p < 0.001), and in hypertensive than in normotensive participants (geometric mean: 0.22 vs. 0.15 mg/dL; p < 0.001). We observed an inverse and significant correlation between serum CRP and AMH levels (r = −0.07; p = 0.02). While CRP had an inverse and statistically significant relationship with serum testosterone (r = −0.12; p < 0.001), there was no correlation between CRP and androstenedione (r = 0.01; p = 0.8) or SHBG (r = −0.06; p = 0.07).

Table 1.

Study population characteristics by anti-mullerian hormone quartiles.

| Variable | Q1 (N = 238) | Q2 (N = 237) | Q3 (N = 237) | Q4 (N = 237) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 57.9 (17.8) | 51.6 (16.9) | 45 (18) | 40.5 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| Age (in categories) | |||||

| Young, n (%) | 63 (26.5) | 88 (37.1) | 135 (67.5) | 160 (67.5) | |

| Middle Age, n (%) | 82 (34.45) | 96 (40.5) | 58 (24.5) | 55 (23.2) | <0.001 |

| Elderly, n (%) | 93 (39.1) | 53 (22.4) | 44 (18.6) | 22 (9.3) | |

| Race | |||||

| Caucasians, n (%) | 144 (60.5) | 132 (55.7) | 129 (54.4) | 88 (37.1) | <0.001 |

| CRP, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 0.23 (0.39) | 0.2 (0.27) | 0.15 (0.3) | 0.12 (0.21) | <0.001 |

| AMH, ng/mL, mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.1) | 4.9 (0.8) | 8.2 (1.3) | 18.6 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 40 (16.8) | 24 (10.1) | 20 (8.4) | 16 (6.75) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 107 (45) | 81 (34.2) | 66 (27.8) | 58 (24.5) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.8 (6.1) | 28.1 (5.3) | 27.7 (5.3) | 26.5 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Current smokers, n (%) | 64 (26.9) | 61 (25.8) | 52 (21.9) | 77 (32.5) | 0.002 |

| Ever smokers, n (%) | 85 (35.7) | 80 (33.9) | 75 (31.6) | 47 (19.8) | |

| Non-smokers, n (%) | 89 (37.4) | 95 (40.25) | 110 (46.4) | 113 (47.7) | |

| GFR, mL/min, mean (SD) | 84.9 (23.6) | 90 (20.7) | 96 (20) | 99 (19.3) | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 198.3 (53.3) | 197.9 (40.7) | 198 (34.9) | 194.2 (40.3) | 0.69 |

| Androstenedione, ng/mL, mean (SD) | 8.7 (7.9) | 8.04 (4.95) | 7.6 (3.9) | 8.01 (4.7) | 0.25 |

| Testosterone, ng/mL, mean (SD) | 4.7 (3.6) | 5.15 (2.3) | 5 (2) | 5.55 (2.2) | 0.005 |

| SHBG, nmol/L, mean (SD) | 45 (24.3) | 44.7 (30.2) | 38.1 (21.3) | 38.2 (24.6) | 0.001 |

*CRP = c - reactive protein; AMH = anti-mullerian hormone; BMI = body mass index; GFR = glomerular filtration rate (calculated using CKD-EPI (chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration equation); SHBG = sex hormone-binding globulin.

**P-values for categorical variables were calculated using Pearson’s Chi-square test; P-values for continuous variables were calculated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and for CRP Kruskal-Wallis’ rank test.

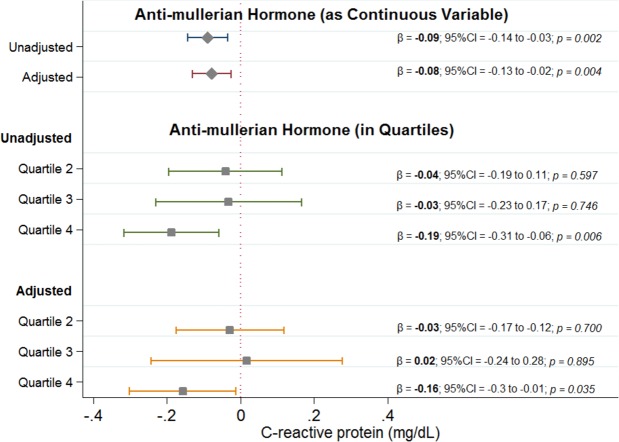

In unadjusted linear regression, each 10 ng/mL increase in AMH was associated with 0.09 mg/dL decrease in CRP (95%CI = −0.14 to −0.03; p = 0.002). The results were robust to adjustment for potential confounding variables; each 10 ng/mL increase in AMH was associated with a 0.08 mg/dL decrease in serum CRP levels (95%CI = −0.13 to −0.02; p = 0.004) (Fig. 1). When examined by quartiles of AMH, men in the highest quartile of AMH had significantly lower CRP levels compared to men in the lowest quartile (−0.19 mg/dL; 95%CI = −0.31 to −0.06; p = 0.006) (Fig. 2) and this difference remained significant after adjusting for potential confounding variables (−0.16 mg/dL; 95%CI = −0.3 to −0.01; p = 0.035).

Figure 1.

Results of unadjusted and adjusted survey weight-adjusted linear regression analyses. The first quartile is a reference hence not shown in the figure.

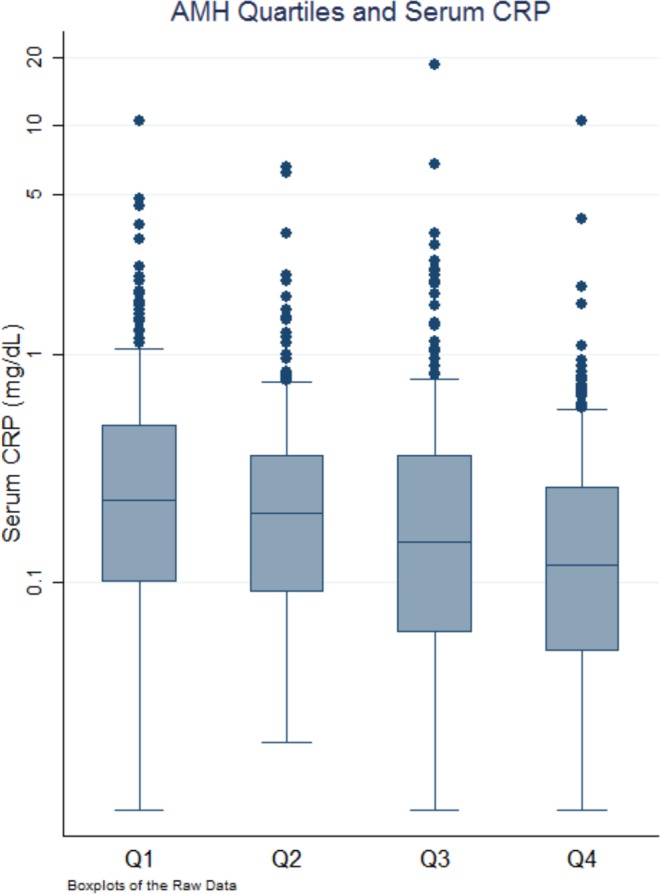

Figure 2.

Association of c-reactive protein (CRP) with anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) divided into quartiles. CRP level decreases as AMH level increases from 1st quartile to 4th quartile.

Discussion

We report an inverse relationship between serum AMH levels and CRP levels in this large cohort of men representative of the United States adult population. The observed relationship was robust and independent of potential confounders such as age, race, smoking status, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, estimated GFR, total cholesterol, total testosterone, SHBG, and androstenedione. Further, the relationship was independent of the distribution of AMH and was seen even when examined with quartiles of AMH. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show this relationship although the exact mechanism of this association needs further exploration.

AMH belongs to the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) superfamily that includes TGF-β and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs). It is secreted as proAMH and is cleaved by enzymes found in vascular tissues15,16. Once cleaved, it binds and activates non-specific receptors (AMH type I or activin receptor-like protein kinases [ALK2, ALK3, or ALK6]) or specific receptor (AMHRII). Activated receptors phosphorylate SMAD cytoplasmic proteins which translocate to the nucleus and modulate gene expression17.

AMH plays an important biological role in embryological development of male fetus by inducing the regression of mullerian ducts18. AMH levels remain high in male until puberty when its levels decline. These levels are negatively regulated by serum testosterone levels and are upregulated by follicular stimulating hormone19. Due to the central role of Sertoli cells in maintaining its levels, AMH has been proposed as a marker of Sertoli cell and testicular function. Further, it’s serum levels may be used to distinguish between anorchia and bilateral cryptorchidism, between testicular dysgenesis and dissociated tubular interstitial dysfunction, and between persistent mullerian duct syndrome and other intersex states19,20.

Several lines of evidence from molecular, cellular, animal, and epidemiological studies suggests biological plausibility for this association. Although its function in cardiovascular tissues remains unclear, the presence of AMHRII in heart and vasculature and proAMH-cleaving enzymes in vascular tissues indicate that cardiovascular system may be a putative target for AMH21–23. AMH has been shown to induce the expression of SMAD6 and, to a lesser extent of, SMAD7 in mouse Leydig cells and may do so in other cells; both SMAD6 and SMAD7 are important modulators of inflammation through regulation of BMP and TGF-beta/activin signaling24,25. In animal studies, exposure of chronic inflammation in pregnant rats using intraperitoneal lipopolysaccharide injections resulted in intrauterine growth restriction and was associated with significantly lower levels of serum AMH in offspring26. In female monkey (Cynomolgus macaques) model, serum AMH concentration was inversely related to the risk of atherosclerosis27.

Several epidemiological studies have explored the role of serum AMH as a marker of ovarian reserve and fertility in women but only a few studies have demonstrated its inverse association with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease28–30. Even fewer studies examining the role of AMH with inflammation have been conducted in men. In women, lower AMH was associated with higher serum CRP levels31. Further, lower AMH levels were also found in women with Crohn’s disease, with polymyositis, and in those with juvenile idiopathic arthritis as compared to healthy controls32–34. Serum AMH levels are also negatively associated with interleukin-6 levels in men12. Abundant data suggest that inflammation is involved in the atherosclerosis, lung disease, and malignancy and that anti-inflammatory therapy reduces the incidence of cardiovascular events and lung cancer in high-risk patients35,36. Thus, AMH, through its effect on inflammation, may reduce cardiovascular disease, COPD, and malignancy and hence overall mortality. However, further studies are needed to strengthen the plausibility for a causal argument of an inverse relationship between AMH and inflammation, morbidity, and mortality.

Our study has important research implications. While AMH is not currently thought to play a vital role during adult life, its inverse association with mortality and with CRP, an inflammatory biomarker, suggests further research on AMH’s role in human disease, mortality, and perhaps longevity is needed. This includes research in better understanding of the genetic and environmental determinants of the AMH levels, molecular signaling pathways, and its interactome. Further, as there is an ongoing research in developing AMH analogues, understanding and examining the effect of any such analogues on non-reproductive systems will also be important37.

Our study has several strengths and potential limitations. We used data representative of the adult men in the United States population. Our results are robust to underlying statistical assumptions about the AMH distribution. As with any observational study, association found in this study does not prove causality. Examining the effect of serum FSH on the relationship between serum CRP and AMH would have been important, however, serum FSH levels were not measured in men who had AMH levels measured. Another potential limitation is that serum CRP levels and AMH levels were measured once and, hence, inferring a longitudinal relationship is not possible with some assumptions. In fact, AMH has been shown to be variable on repeat sampling in women38. However, such variability should result in bias of effect estimates towards null and the true effect size of the relationship may be larger than what is observed in our study.

In summary, results from our study demonstrate a robust inverse correlation of AMH with CRP levels. Although cross-sectional, the findings of the present study call for additional studies to test the hypothesis that modulation of inflammatory processes is a potential pathway by which AMH reduces all-cause mortality in men.

Author Contributions

Dinesh Kadariya and Rehan Qayyum contributed to the conception, design of the work, and the acquisition and analysis of data. Nargiza Kurbanova contributed to the design of work and the interpretation of the data. Dinesh Kadariya drafted the paper. Rehan Qayyum and Nargiza Kurbanova critically revised the paper. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lee, M. M. et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance in humans: normal levels from infancy to adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Feb; 81(2), 571–6 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Aksglaede, L. et al. Changes in anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) throughout the life span: a population-based study of 1027 healthy males from birth (cord blood) to the age of 69 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Dec; 95(12), 5357–64 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor type 2 [Homo sapiens (human). from, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/269 [uid].

- 4.Chong,Y. H. et al. Elderly men have low levels of anti-Müllerian hormone and inhibin B, but with high interpersonal variation: a cross-sectional study of the sertoli cell hormones in 615 community-dwelling men. PLoS One. Aug 5; 8(8), e70967 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Dennis, N. A., Jones, G. T., Chong,Y. H., van Rij, A. M. & McLennan, I. S. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels correlate with infrarenal aortic diameter in healthy older men: is AMH a cardiovascular hormone? J Endocrinol. Sep 6; 219(1), 13–20 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Qayyum, R. & Akbar, S. Serum anti-mullerian hormone and all-cause mortality in men. Endocrine. Oct; 54(1), 225–231 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ross, R. Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. Jan 14; 340(2), 115–26 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Barnes, P. J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. Jul 27; 343(4), 269–80 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Coussens, L. M. & Werb, Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. Dec 19–26; 420(6917), 860–7 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Kaptoge, S. et al. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet. Jan 9; 375(9709), 132–40 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Li, Y. et al. Hs-CRP and all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality risk: A meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. Apr; 259:75–82 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Tremellen, K., McPhee, N. & Pearce, K. Metabolic endotoxaemia related inflammation is associated with hypogonadism in overweight men. Basic Clin Androl. Mar 8; 27:5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Wallace, A. M., Faye, S. A., Fleming, R. & Nelson, S. M. A multicentre evaluation of the new Beckman Coulter anti-Mullerian hormone immunoassay (AMH Gen II). Ann Clin Biochem. Jul; 48(Pt 4), 370–3 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Levey, A. S. et al. CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. May 5; 150(9), 604–12 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Stawowy, P. et al. Selective expression of the proprotein convertases furin, pc5,and pc7 in proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells of the rat aorta in vitro. J Histochem Cytochem. Mar; 49(3), 323–32 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Veinot, J. P. et al. Implications of proprotein Convertase 5 (PC5) in the arterial restenotic process in a porcine model. Cardiovasc Pathol. Sep-Oct; 13(5), 241–50 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Massagué, J. & Gomis, R. R. The logic of TGFbeta signaling. FEBS Lett. May 22; 580(12), 2811–20 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lewis, K. & Lee, P. A. Endocrinology of male puberty. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. Feb; 16(1), 5–9 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Rey, R. Assessment of seminiferous tubule function (anti-müllerian hormone). Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. Sep; 14(3), 399–408 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Sharpe, R. M. Pathways of endocrine disruption during male sexual differentiation and masculinization. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. Mar; 20(1), 91–110 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Ricci, M. et al Differential changes in TGF-β/BMP signaling pathway in the right ventricular myocardium of newborns with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Card Fail. Aug; 16(8), 628–34 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Giusti, B. et al. Gene expression profiling of peripheral blood in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. Jul; 38(1), 104–12 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.McLennan, I. S. & Pankhurst, M. W. Anti-Müllerian hormone is a gonadal cytokine with two circulating forms and cryptic actions. J Endocrinol. Sep; 226(3), R45–57 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Lee,Y. S. et al. Smad7 and Smad6 bind to discrete regions of Pellino-1 via their MH2 domains to mediate TGF-beta1-induced negative regulation of IL-1R/TLR signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. Mar 19; 393(4), 836–43 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Clarke, T. R. et al. Müllerian inhibiting substance signaling uses a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-like pathway mediated by ALK2 and induces SMAD6 expression. Mol Endocrinol. Jun; 15(6), 946–59 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Shalom-Paz, E. et al. IUGR induced by maternal chronic inflammation: long-term effect on offspring’s ovaries in rat model-a preliminary report. J Endocrinol Invest. Oct; 40(10), 1125–1131 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Appt, S. E., Chen, H., Clarkson, T. B. & Kaplan, J. R. Premenopausal antimüllerian hormone concentration is associated with subsequent atherosclerosis. Menopause. Dec; 19(12), 1353–9 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.de Kat, A. C., Verschuren, W. M., Eijkemans, M. J., Broekmans, F. J. & van der Schouw,Y. T. Anti-Müllerian Hormone Trajectories Are Associated With Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Results From the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Circulation. Feb 7; 135(6), 556–565 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kim, C. et al. DCCT/EDIC Research Group. Anti-Müllerian hormone and its relationships with subclinical cardiovascular disease and renal disease in a longitudinal cohort study of women with type 1 diabetes. Womens Midlife Health. Aug 18; 3:5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Looby, S. E. et al. Reduced ovarian reserve relates to monocyte activation and subclinical coronary atherosclerotic plaque in women with HIV. AIDS. Jan 28; 30(3), 383–93 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Verit, F. F., Akyol, H. & Sakar, M. N. Low antimullerian hormone levels may be associated with cardiovascular risk markers in women with diminished ovarian reserve. Gynecol Endocrinol.; 32(4), 302–5 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Şenateş, E. et al. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels are lower in reproductive-age women with Crohn’s disease compared to healthy control women. J Crohns Colitis. Mar; 7(2), e29–34 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.de Souza, F. H. et al. Reduced ovarian reserve in patients with adult polymyositis. Clin Rheumatol. Oct; 34(10), 1795–9 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Ferreira, G. R. V. et al. Ovarian reserve in young juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients. Mod Rheumatol. May; 29(3), 447–451 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Ridker, P. M. et al. CANTOS Trial Group. Effect of interleukin-1β inhibition with canakinumab on incident lung cancer in patients with atherosclerosis: exploratory results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. Oct 21; 390(10105), 1833–1842 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Ridker, P. M. et al. CANTOS Trial Group. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N Engl J Med. Sep 21; 377(12), 1119–1131 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Kushnir, V. A., Seifer, D. B., Barad, D. H., Sen, A. & Gleicher, N. Potential therapeutic applications of human anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) analogues in reproductive medicine. J Assist Reprod Genet. Sep; 34(9), 1105–1113 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Rustamov, O. et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone: poor assay reproducibility in a large cohort of subjects suggests sample instability. Hum Reprod. Oct; 27(10), 3085–91 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]