Abstract

Background

Tibia fracture is the most common long bone fracture. The fractures of tibia are commonly open fractures due to subcutaneous position of the tibia. The choice of technique for stabilization of open tibia fractures includes - External fixation, unreamed intra-medullary nails [URTN], Reamed intra-medullary nails, ORIF with Plating.

Objectives

To evaluate & compare the results of Unreamed Intra-Medullary Nail Versus Half Pin External Fixator in Grade III [A & B] Open tibia fractures.

Methods

This prospective clinical study [Randomized chit box] was done on 50 patients presenting to our institute within 24 h of injury. Only those who were skeletally mature with open tibia fracture Grade IIIA & IIIB [Gustilo-Anderson] were included in this study. After initial management, radiological assessment was done. Following this adequate wound debridement, skeletal stabilization with either primary URTN or external fixator was done. Inspection and debridement were repeated at 48-h intervals until the wound was considered clean.

Results

50 cases [25 each group] were compared in terms of - Final Alignment of the Fracture, Presence of Infection/Non-union/Mal-union, Hardware failure, Time to Bone Union, Number of Operative Procedures after index admission. Mean time to full weight bearing was 20.96 weeks in URTN group versus 24.8 weeks in Ex-fix group. 5 in URTN group required further surgery for non-union versus 11 patients in Ex-fix group. There were 6 significant pin track infection. Removal of nail was required in 1 case of deep infection.

Conclusion

This study supports the use of the URTN over External fixator in the treatment of severe open tibia fractures.

Keywords: Tibia fractures, Intra-Medullary Nail, Unreamed, External fixator, Soft tissue management

1. Introduction

Tibia fracture is the most common long bone fracture. The fractures of tibia are commonly open fractures due to subcutaneous position of the bone. The treatment of open tibia fractures remains controversial. The precarious blood supply and lack of soft-tissue cover of the shaft of tibia make these fractures vulnerable to non-union and infection. The rate of infection may be as high as 50% in grade-IIIB open fractures.1 Attempts to reduce these complications have led to aggressive protocols which include immediate intravenous antibiotics, repeated soft-tissue debridement, stabilization of the fracture, early soft-tissue cover and prophylactic bone-grafting.2,3

External fixation has been popular because of the relative ease of application and the limited effect on the blood supply of the tibia, but these advantages have been outweighed by high incidence of pin-track infection, difficulties related to soft-tissue management and the potential for mal-union.4, 5, 6, 7

The use of Unreamed Intra-medullary (IM) nails avoids pin-track infection but may potentially compromise stability at the fracture site.8

The use of reamed IM nails in the management of open tibia fractures is contentious.9 While reamed nails offer improved stability of the fracture, their use carries a theoretical risk of increasing infection and non-union as a consequence of disturbing the endosteal blood supply.10

This study was done to evaluate & compare the results of Unreamed Intra-Medullary Nail (URTN) Versus Half Pin External Fixator in Grade III [A & B] Open tibia fractures.

2. Materials & methods

This study was conducted in Orthopaedics department, SMS hospital, Jaipur from June 2012 to June 2013. During this study, 50 patients with open tibia fractures [Gustillo- Anderson Type IIIA & IIIB] were included according to following criteria.

Patients included in this study were

-

1.

Patients admitted within 24 h of injury

-

2.

Patients without concomitant fracture of other site

-

3.

Patients without any major co-morbid illnesses & fit for surgery.

-

4.

Fractures without bone loss or intra-articular fractures.

-

5.

Patients willing for the surgery and follow up with written and informed consent.

Patients excluded from the study were

-

1.

Fractures lying proximal to Tibial tuberosity and within 4c.m. of the Ankle

-

2.

Pathological Fractures

-

3.

Poly-traumatized pts.

-

4.

Grade IIIC Fractures

-

5.

Skeletally immature patients.

-

6.

Refusal for the inclusion in the study.

Fifty patients were divided equally into two groups based on the method of treatment by Randomized chit box. The soft tissue injury was classified according to the Gustillo and Anderson grading system at the time of initial assessment4,5 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Summary and comparison of patient characteristics in both groups.

| External Fixator group [n = 25] | URTN group [n = 25 ] | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (F/M) | 6/19 | 7/18 |

| Average age, years | 38.76 | 40.44 |

| Average follow up, weeks | 36 | 36 |

| Mechanism of Injury | ||

| RTA [ in car] | 3 | 2 |

| Motorcyclist | 10 | 12 |

| Pedestrian | 9 | 8 |

| Falls, Other | 3 | 3 |

| Soft tissue injury grade [Gustillo and Anderson] | ||

| IIIA | 20 | 21 |

| IIIB | 5 | 4 |

| AO classification type [from radiographs] | ||

| A | 7 | 9 |

| B | 7 | 6 |

| C | 11 | 10 |

| Injury severity score | ||

| Mean | 14.4 | 13.9 |

| Range | 8–40 | 8–35 |

The geometry and degree of bone communition was graded using admission radiograph according to the AO classification from type A to C. Associated injuries were classified and scored according to the Injury Severity Score [ ASIS Guideline]. All patients were initially assessed in the emergency room. Aseptic dressing was done and the limb was immobilised. Intravenous third generation cephalosporin, gentamycin and metronidazole were immediately administered and continued for minimum of 5 days. Irrigation, debridement, and primary skeletal stabilization, depending on the group allotted to the patient, were performed as soon as the patient's general condition became stable.

The URTN was inserted via a medial para-patellar approach. We used 9 mm diameter solid nail in all patients [Fig. 1, Fig. 2]. A six pin unilateral frame configuration was used in patients treated with external fixation. Inspection and debridement were repeated as required at 48-h intervals until the wound was considered clean and all necrotic tissue had been removed [Fig. 3, Fig. 4]. Soft tissue coverage was performed with skeletal stabilization or at a later date, as was appropriate for each individual patient with help of plastic surgeon if required. Outpatient physiotherapy was arranged for all patients before discharge. Pin site care was advised to patient's attendant. Pin sites were cleaned daily with a povidone-iodine solution and dressed with sterile dry gauze. Postoperatively, patients treated with the URTN were mobilized with ¼ body weight partial weight bearing until static locking was removed, usually at 6 weeks. Patients were then allowed full weight bearing according to the fracture pattern and condition of soft tissues.

Fig. 1.

Intraop and immediate postop clinical picture of patient of the URTN group.

Fig. 2.

Immediate postop Xray of the URTN group.

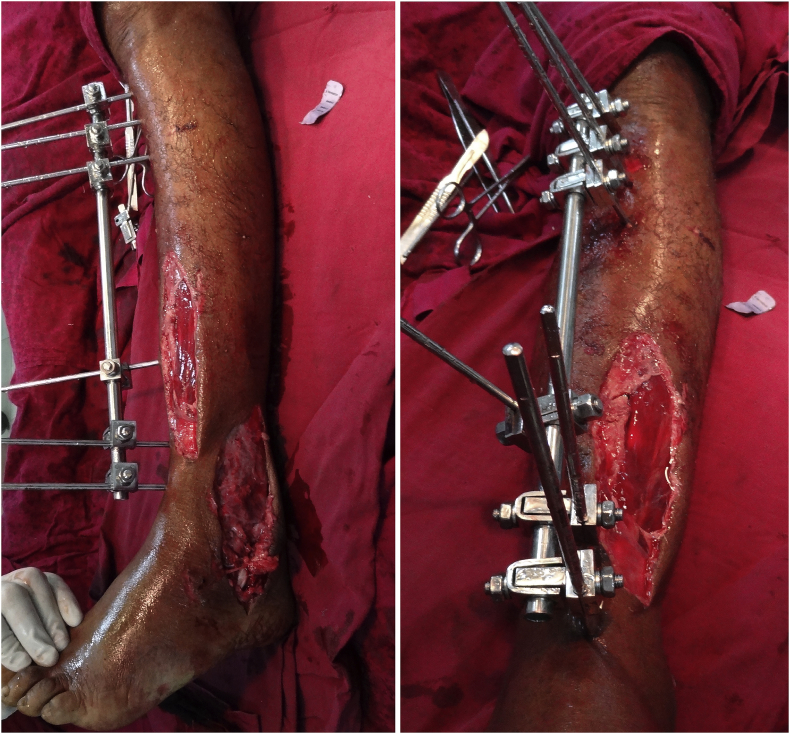

Fig. 3.

Immediate postop clinical picture of patient of the ExFix group.

Fig. 4.

Immediate postop Xray of the ExFix group.

Patient's with external fixators remained non-weight bearing for the first 4–6 weeks. Partial weight bearing then started, provided that radiographs showed some evidence of callus formation. Full weight bearing was allowed when adequate bridging callus was visible on radiographs. Conversion to patellar-tendon bearing cast followed removal of the external fixator [Fig. 5]. Time to full weight bearing and time to bony union were recorded. Union was defined as bridging callus crossing three of four cortices on orthogonal radiographs with no pain on palpation over the fracture site or when weight bearing.

Fig. 5.

Change of the ExFix to Patellar tendon bearing cast.

Statistical analysis was performed using sigma stat version 1.0 [jamdel corporation, san Rafael, CA]. The student's t-test/Levene” s test and fisher's exact/Pearson chi square test were used where appropriate. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Fifty cases were followed for 36 weeks. Out of which 25 were treated with the half pin external fixator and 25 with URTN. The average age of the study group was 39 years [range 20–72 years]. The most common mechanism of injury was a high-energy motor vehicle crash involving an unprotected road user [i.e. pedestrian, motorcyclist]. Both groups were comparable in terms of age, gender, fracture location, fracture communition, grade of soft tissue injury, and injury severity score. Soft tissue coverage was required in 9 of the 25 patients treated with external fixator and 8 of the 25 patients treated with the URTN. Primary muscle pedicle graft was done in 4 cases. Medial gastrocnemius flap was done in 3 cases; tibialis posterior flap was done in one case while soleal flap was done in one case [Fig. 6]. Skin grafting was required in 8 cases. Knee and ankle exercise were commenced at an average of 2.5 days. The average time to bony union was 34.4 weeks in the ex-fix group and 32.64 weeks in the URTN group [p = 0.009, t-test]. The average time to full weight bearing was 24.8 weeks in the ex-fix group and 20.96 weeks in the URTN group [p = 0.004, t-test]. 6 patients treated with the external fixator developed significant pin tract infections. These occurred after a mean of 12 weeks postoperatively and necessitated removal of the external fixator in 2 patients and change of pin sites in 4 patients. In contrast, only 2 patients in the URTN group developed an infection. In one a small abscess developed over the proximal locking screw at 26 weeks. After incision and drainage and removal of the locking screw, intravenous antibiotics started for 5 days. In other patient Nail had to be removed at 31 weeks. 5 of total 8 patients who developed an infection had sustained a grade IIIB injury. Staphylococcus aureus was the causative organism in all cases [Table 2]. Non-union was defined as an absence of bridging callus across a fracture site after an expected time interval for that injury. As such, deciding that a fracture was a delayed or non-union depended on the extent of injury incurred in each individual case. Most closed tibial fractures can be expected to unite within 6 months. These were high energy injuries with significant periosteal stripping and soft tissue compromise. 11 patients treated with the external fixator were classified as non-union at a mean of 28 weeks after their injury. All underwent a secondary procedure and went on to unite. 5 patients had an open reduction and internal fixation [ORIF] with autogenous bone grafting, 2 patients had a reamed nail inserted, and 4 patients underwent bone grafting alone. 5 patients treated with the URTN were classified as non-union at 22 weeks. All were managed with an exchanged reamed tibia nail and progressed to union. There was a delay in dynamization of the original URTN in all of these patients secondary to skin problems. 5 patients treated with the external fixator went to mal-union compared to only one in URTN group. The number of outpatient visits and operative procedure done for patients treated with the external fixator was significantly more than for patients treated with the URTN. Hardware failures were defined as external fixation schanz pin breakage and IM nail or locking screw breakage. Pin and screw loosening were not considered to be hardware failures. There was one case of screw breakage in URTN group. In the follow-up period, 8 of the 25 patients treated initially with the URTN required removal of their fixation. The five patients with non-union and one with infection have already been discussed. 2 patients developed knee pain after dynamization necessitating removal of their nail after 20 weeks.

Fig. 6.

2 cases showing the soft tissue coverage with the help of flap and with the help of skin grafting.

Table 2.

Outcome and complications of the open fractures managed by IM nailing and External fixators.

| Ex- Fix Group [ n = 25] | URTN Group [ n = 25] | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to union | |||

| Mean [weeks] | 34.4 | 32.64 | 0.009 |

| SD [weeks ] | 2.64 | 1.80 | t- test |

| Time to full weight bearing | |||

| Mean [weeks ] | 24.8 | 20.96 | 0.004 |

| SD [weeks ] | 5.29 | 3.32 | t- test |

| Infection [%] | 6 [ 24] | 2 [ 8] | |

| Pin track | 6 | 0 | 0.012 X2 test |

| Superficial | 0 | 1 | |

| Deep | 0 | 1 | |

| Nonunion [%] | 11 [44%] | 5 [20%] | .006 x2 test |

| Mal-union [%] | 5 [20] | 1 [4] | .008 x2 test |

| Hardware failures | 0 | 1 | |

Thus no statistically significant difference was observed in two groups with respect to mechanism of injury, fracture characteristics, operative time, union rate and range of knee/ankle motion (p value > 0.05). However, URTN group had statistically significant lower rates of infection, mal-union, non-union, time to union and time to full weight bearing.

4. Discussion

The universally accepted principles of management of open fractures of the tibia include immediate wound debridement and irrigation, skeletal stabilization, repeated wound debridement and early soft tissue coverage. The methods of bony stabilization however have evolved over the years but remain controversial. Cast immobilization and plate fixation proved unacceptable for the management of these injuries, with high rates of non-union, mal-union and infection. Bach and Hansen compared ORIF with external fixation in a randomized trial. A threefold difference in infection rates was observed [ORIF, 35%; external fixation, 13%]. Concerns regarding the introduction of metal into an area of potential bacterial contamination meant that interest developed quickly in external fixation, and soon it was the accepted method of managing these injuries. External fixation is an excellent initial method of skeletal stabilization in these injured, often unstable patients. However, several studies have demonstrated that their value in the definitive management of these injuries is questionable, with high rates of pin loosening, sepsis, non-union and mal-union reported. The unilateral frame construct used in our population has a number of advantages. It can be applied quickly and with considerable ease and there is minimal obstruction to soft tissue access. There is little, if any, biomechanical evidence to suggest that additional dimensions on a frame confer significant advantages to the healing fracture site. Edwards at al. reported a 15% infection rate in 202 consecutive grade III open injuries. Following a more aggressive approach to debridement, they reduced their infection rate to 9% in the latter half of their study.

The concept of early bone grafting was suggested and has since become part of the baseline protocol used by most trauma centres when using external fixation in open tibial fractures. Mal-union is certainly more commonly encountered in patients treated with external fixation, and rate of up to 20% are quoted in published literature. Proponents of its use suggest that this is because of premature removal of the fixator and that callus should be strengthened by progressive loading of the fracture site. A staged disassembly of the frame increases flexibility, as the need for stability recedes with time. Alternatively, dynamization accelerates callus maturation without compromising stability. Mal-union was not evaluated in this series because the radiographs available for review, although orthogonal, were not consistently anteroposterior and lateral films. The true alignment [or mal-alignment] in the coronal and sagittal planes could not therefore be consistently measured for an accurate comparison. Before the introduction of locked unreamed intra-medullary nails, many institutions reported good results with unlocked unreamed nails [i.e. Lottes,11 Enders nails] when compared with external fixation.12 However, experience dictates that these devices are only suitable in stable diaphyseal fractures, and are totally unsuitable for the more comminuted injuries typically encountered in these patients.

Although a number of studies support the use of the unreamed intra-medullary nail over external fixation, the success of various treatment options is difficult to extract from many reports as, frequently, grade I, II, and III injuries are considered together. Santoro et al.13 prospectively compared the use of external fixation and unreamed locked nailing in open tibial fractures. In 65 patients, they reported a higher union rate, shorter time to union and fewer mal-unions in the group treated with the unreamed nail. There were only 12 grade IIIB injuries in this study, which unfortunately were not reported separately. Henley at al.7 reported on a series of 174 type II and III open tibial fractures and found a significantly lower incidence of infection and mal-union with URTN compared with external fixation. Although the external fixation group required significantly more secondary procedures, time to union was similar in both groups. Torne'tta et al.14 published the early results of a prospective, randomized study comparing external fixation with the URTN in grade IIIB injuries. All 29 patients healed within 9 months, with a similar time to union in both treatment groups. Of interest, 19 of the more severe injuries were prophylactically bone grafted after an average of 6 weeks. Schandelmaier et al.15 reviewed 32 patients with grade IIIB injuries treated with either external fixation or URTN. Time to bony union, infection, and non-union rates were not significantly different between the two groups, but patients treated with the URTN made an earlier return to full weight bearing and a better functional recovery. Early reconstruction of the soft tissue envelop is essential and, if possible, should be performed within 48 h, usually timed to coincide with the ‘second look.’ occasionally, it is not possible to achieve this, but every attempt should be made to close the wound within 5 days. Further delay beyond this period leads to increased rate of infection and non-union, with reduced success of free tissue transfers. Plastic and reconstructive surgeons must be involved early, at the time of admission or within 24 h. Inappropriate wound extensions performed by the inexperienced surgeon during the initial debridement may limit the options available when coverage is required. 9 of our 16 patients who developed non-union [11 in ex-fix group and 5 in URTN group] were grade IIIB injuries requiring soft tissue coverage. In 1 case, the coverage was delayed by more than 5 days. The strength of some of the observations in our study, although significant, was limited by the relatively small number of patients and short follow-up. However, at the outset, both groups were comparable with regards to age, gender, mechanism of injury, grade of soft tissue/bony injury, and associated injuries.

Results of our study concurred with that of a retrospective study conducted by Fintan j. Shannon, AFRCSI, Hannan Mullet, FRCSI, and Kieran and O'Rourke, FRCSI in St. Vincent's University Hospital, Elm park, Dublin, Ireland. They retrospectively reviewed 30 patients with Grade III Open tibia fractures treated with Ex-Fix or URTN with 5 years' retrospective study & concluded that both methods achieved good functional outcomes; however, the URTN group had a lower complication rate. Our study had not a long follow-up series, but it's prospective one.

5. Conclusion

Our study showed that unreamed intramedullary nailing with adequate soft tissue management offers advantage of rigid fixation, low incidence of infection, non-union, good functional results and early return to work. A proper soft tissue management is mandatory in treatment of these fractures. In conclusion, we recommend the unreamed intra-medullary nail over external fixation in the treatment of grade III injuries of the tibial diaphysis. It is a safe, effective technique with a comparably low complication rate. Management of concomitant soft tissue injuries is consistently easier, and patients make an earlier functional recovery.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2018.10.016.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Chapman M.W. The role of intramedullary fixation in open fractures. Clin Orthop. 1986;212:26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellinger E.P., Caplan E.S., Weaver L.D. Duration of preventative antibiotic administration for open extremity fractures. Arch Surg. 1988;123:333–339. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400270067010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dellinger E.P., Miller S.D., Wertz M.J., Grypma M., Droppert B., Anderson P.A. Risk of infection after open fracture of the arm or leg. Arch Surg. 1988;123:1320–1327. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400350034004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gustilo R.B., Anderson J.T. Prevention of infection in the treatment of 1025 open fractures of long bones: retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(4):453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gustilo R.B., Gruninger R.P., Davis T. Classification of type III (severe) open fractures relative to treatment and results. Orthopaedics. 1987;10:1781–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustilo R.B., Mendoza R.M., Williams D.N. Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: a new classification of type III open fractures. J Trauma. 1984;24:742–746. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henley M.B. Intramedullary devices for tibial fracture stabilization. Clin Orthop. 1989;240:87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holbrook J.L., Swiontkowski M.F., Sanders R. Treatment of open fractures of the tibial shaft: ender nailing versus external fixation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71A:1231–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson K.D. Use of small-diameter “unreamed” locked intramedullary nails in the treatment of open tibial shaft fractures. Mediguide Orthop. 1991;10(3):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein M.P.M., Rahn B.A., Frigg R., Kessler S., Perren S.M. Reaming versus non-reaming in medullary nailing: interference with cortical circulation of the canine tibia. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1990;109:314–316. doi: 10.1007/BF00636168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lottes J.O. Medullary nailing of the tibia with the triflange nail. Clin Orthop. 1974;105:253–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pankovich A.M., Tarabishy I.E., Yelda S. Flexible intramedullary nailing of tibial-shaft fractures. Clin Orthop. 1981;160:185–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santoro V., Henley M., Benirschke S., Mayo K. Proceedings of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association Meeting, Toronto. 1990. Prospective comparison of unreamed interlocking nails versus half-pin external fixation in open tibial fractures; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tornetta P., III, Bergman M., Watnik N., Berkowitz G., Steurer J. Treatment of grade-IIIb open tibial fractures. A prospective randomised comparison of external fixation and non-reamed locked nailing. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76B:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schandelmaier P., Krettek C., Rudolf J., Kohl A., Katz B.E., Tscherne H. Superior results of tibial rodding versus external fixation in grade IIIB fractures. Clin Orthop. 1997;342:164–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.