Abstract

Background:

Patient attire is paramount to patient’s dignity and overall experience. In this pilot study and in concert with a designer and clinician, we developed, patented, tested, and evaluated patient and provider preference and experience with a novel patient gowning system. Our objective was to survey obstetrics and gynecology hospital inpatients’ and providers’ experience with a novel hospital attire system; the patient access linen system (PALS).

Methods:

Patients were provided a PALS item at the beginning of a provider’s shift or at the start of an outpatient visit. Following their use of the PALS item, the patients and providers completed a separate multiple-choice and free-response question survey. Surveys were completed by patients each time a PALS item was returned to the provider for processing.

Results:

Patients and providers had a significantly positive experience with the PALS. The majority of patients had positive responses to each question about comfort and function of the PALS system, showed consistent preference for the PALS in comparison to a traditional hospital gown and demonstrated that comfort of hospital clothing is a priority for patients. The majority of providers found PALS easy to use when compared to the traditional gown with regard to clinical examinations.

Conclusion:

Patients in our pilot prioritized hospital attire as a key element in their overall hospital experience, and both patients and providers preferred the PALS system over the traditional hospital gown. Further study is needed on patient attire and evaluation of the potential clinical impact of the PALS.

Keywords: hospital, gown, patient satisfaction, experience, patient feedback

Introduction

“The stone which the builders rejected has become the chief cornerstone.” (1) Psalm 118:22

As children, the phrase “snug as a bug in a rug” connotes comfort, warmth, and the protective cocoon of safety and home. As patients, we share the human experience of dealing with illness and hospitalization at some point in our lives. This is daunting enough without the depersonalization that hospitalization can cause. Patient clothing is central to patient’s dignity and well-being and is one of the first elements encountered during hospital admission. (2) The purpose of clothing is “to maintain bodily and mental efficiency and a feeling of comfort in a particular climatic condition.”(p. 20-22) (3) Clothing buffers us against environmental change and protects us in various social contexts. (4)

A gown that is considered scratchy and thin and where the back falls open due to poorly secured straps cannot impart warmth, coverage, or a sense of security. Prior studies have found patient preference for greater waist and pelvic coverage, and physicians find patient attire with greater coverage to be appropriate in most clinical circumstances. (5) A more accurate description for the current model would be “open and froze from your nose to your toes” and neither buffers us nor maintains our social or human connection. The “traditional” patient gown has cried out for a new tradition for a long time; the current model does not contribute to enhancing the overall patient experience.

There have been several attempts to address this issue, some by designers and others by hospitals. These models include wrap or kimono styles, and add at least 1 useful dimension to the current model. (6,7) Missing, however, are 3 major elements: (1) a gown thatt allows full body coverage for the patient, (2) a gown that allows examination of 1 area of the body at a time with rapid and secure gown closure following the examination, and (3) synergism of function and form.

There are 3 central tenets of quality in health care: patient safety, clinical efficacy, and patient experience. Prior data demonstrate consistent association among measures of patient experience and increased clinical efficacy and patient safety. (8) This association holds true across a spectrum of diseases and outcome measures. Physicians are now routinely assessed on their contribution to overall patient experience, including dignity, respect, and compassion. Thus, patient experience “the stone which the builders rejected” (formerly marginalized or overlooked) has become “the chief cornerstone” (1) of health-care quality. There is no more poignant example reflective of a patient’s experience than the traditional hospital gown as referenced earlier. From a human perspective, patient clothing has an intrinsic value to empathic care and sends a clear message to our patients that they are both valued and respected. Clinicians must resist sidelining patient experience as too “soft” or subjective, divorced from the “real” clinical work of measuring safety and clinical efficacy. After all, if our patients feel more protected and comfortable, they may also feel more confident. The expressive function of clothing helps establish our relationship as patients to our physicians and other hospital personnel. Once connections are strengthened and trust is gained, recovery may be eased. Patients will feel more comfortable to ambulate safely, potentially speeding recovery and even possibly reducing length of stay. (9 –11) In order to address this (literal) gap in hospital clothing, we have developed and patented the Patient Access Linen System (PALS) as described in detail in the following sections. This pilot study was undertaken to prospectively evaluate patient and provider experience with the PALS. In concert with a fabric artist/designer and clinician, we developed, patented, tested, and evaluated patient and provider preference and experience with the PALS as an alternative to the traditional hospital gown.

Patients and Methods

This was a descriptive, prospective pilot study of obstetric or gynecology hospital inpatients and care providers, characterizing their experience with a novel hospital attire system, PALS. This system was developed and patented in concert with a designer and a clinician (PALS, US Provisional Application Number 62/339,186, May 20, 2016). As a pilot, PALS was granted an exemption from the the health system’’s Institutional Review Board. This is a unique and dynamic collaboration between a physician and a professional designer, within the realm of patient experience.

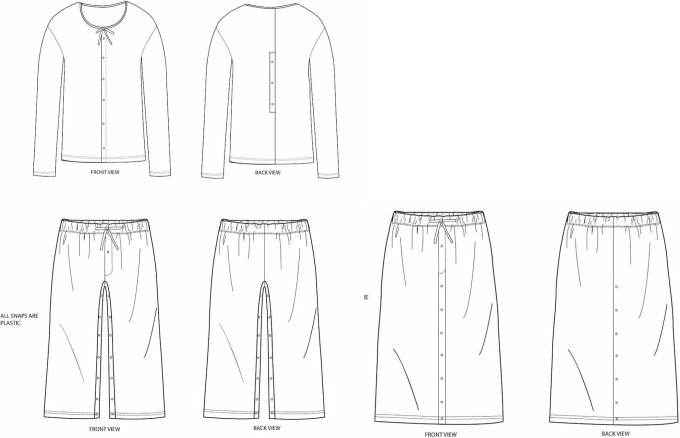

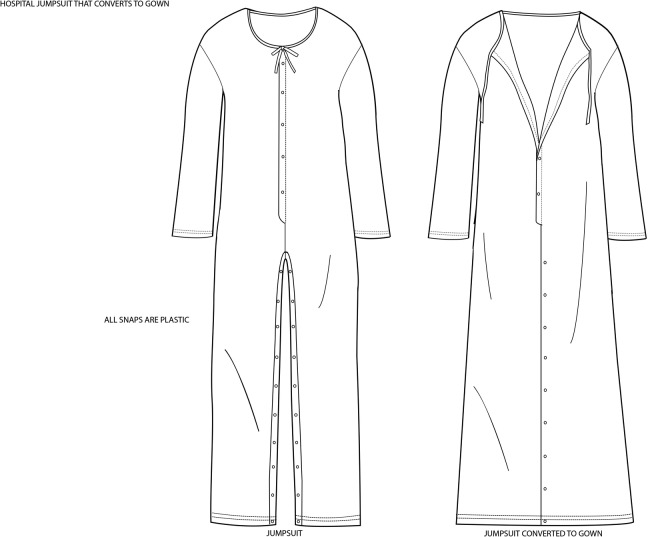

The system is comprised of 2 models, a top and bottom combination (Figure 1) and a jumpsuit, which includes each element of the 2-piece design, with the exception of the waist portion (Figure 2). All items were manufactured in a universal size. The design of the PALS permitted adjustments to the neckline (both models), the waist (2 piece model), and the length, allowing a comfortable fit for patients of body mass index (BMI) from 22 to 35. Once this project is expanded, the current model will be scaled both smaller (for children) and larger (for those over BMI of 35). The fabric used was 70% cotton/30% polyester, with medium fiber pore size, designed to feel similar to fabric used in many types of sleepwear. The system utilizes snap closures that are radiopaque yet MRI safe and can be opened and closed sequentially, to reduce unnecessary patient exposure during examinations.

Figure 1.

Patient access linen system (PALS) top and bottom shown with pants option (left) and skirt option (right).

Figure 2.

Patient access linen system (PALS) jumpsuit, pants option on left, dress option, and drop neckline on right.

The top opens and closes vertically in the front and middle third of the back (via snaps) and features a drawstring neckline (suitable for breastfeeding). Physician or nursing staff can thus perform cardiac, pulmonary, breast, or abdominal examinations, as clinically indicated, opening the portion of the gown thus required for examination and closing the PALS once the examination is concluded. The lower portion of the 2-piece model features a half elastic (back)/half drawstring (front) waist and provides more coverage than the traditional gown. The lower portion may also be worn as pants when snaps are closed front to back and as a skirt by closing the snaps horizontally (left to right), thus accommodating patients’ preference as well as cultural needs. Thus, perineal, pelvic, rectal, and lower extremity examinations may be performed while affording the patient minimal physical exposure. The jumpsuit model of the PALS includes each element as referenced above with elimination of the waist portion. Patients therefore have a choice in their hospital clothing and may choose to wear either the 1- or 2-piece model; in some cases, less tall patients chose to simply wear the top. Gowns underwent preliminary testing and modification with our research team prior to finalization, production, and initiation of patient testing.

Pilot testing of PALS was performed from January 2017 to December 2017 at a tertiary care hospital of a health system in New York. Data were collected by survey from patients as well as nurses, mid-level providers, and medical office assistants. Inclusion criteria for providers were full-time employees of the hospital who delivered direct patient care for inpatients or outpatients within the obstetrics and gynecology department. Patient inclusion criterion was either hospitalization as an inpatient on the obstetrics or gynecology service or presentation as an outpatient to our ambulatory care unit. Patients unable to understand instructions due to decreased level of consciousness were excluded from the pilot.

Patients were approached by their care providers with the option to participate in the trial. Patients were able to choose a garment (jumpsuit, top, or top and pant) from the PALS system. Inpatient participants wore a PALS item for up to 12 hours, and outpatient participants wore the PALS item for the duration of their appointment. Following the shift or appointment, both patient and staff completed a brief survey regarding their experience with the PALS system. Surveys for patients and providers were separate and anonymous and were returned to central drop boxes for periodic collection by the study personnel. Patients could repeat use of the PALS during their stay and had the option to evaluate a model other than the one they first chose as well as to select the traditional hospital gown. Thus, providers were able to provide multiple patients under their care with access to the PALS.

The patient survey consisted of 9 rating-scale questions and 1 free-response question. Response options were “definitely yes,” “somewhat yes’, “neutral/no opinion,” “somewhat no,” or “definitely no.” The provider survey consisted of 13 rating-scale questions with response options “difficult” to “easy,” “not beneficial” to “beneficial,” and “do not like” to “like a lot,” and 1 free response question, allowing for input on the provider’s experience caring for patients wearing a PALS item. Questions for both groups elicited which item of the PALS system was used, ease of donning and doffing a PALS item, comfort during use, and access for examination and breast-feeding. Additionally, patients were asked about how important the comfort of hospital clothing was to their stay.

Surveys were reviewed and coded by 3 research team members. Responses to rating-scale or free-response questions that were illegible were excluded. After 9 months of the study, a preliminary data analysis was performed. Due to the overall consistency of responses from providers, collection of data from providers was concluded; following this, only patient data were collected. Data were analyzed using SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows. Frequencies and percentages were tabulated and calculated for each item across the patient and provider surveys. Qualitative data from the patient and care provider open-ended survey items were pooled, tallied, and reviewed to determine patterns in experience and potential areas for improvement and future study.

Results

A total of 801 patients and 451 providers completed surveys, characterizing their experience with a novel hospital attire system. This represented approximately 20% of the total inpatient (3600) and 5% of the total outpatient population (1600) of the units studied. Inpatients comprised 90% (720) of the study group, and the remaining 10% (81) were outpatients. When choosing which PALS item to test, 49.1% of patients used the top only (at approximately 34 inches in length from neckline to hem, this option provided sufficient coverage for some of our patients), 26.7% used the jumpsuit, and 24.2% used the top and pant option (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Responses by Garment Used.

| N | Top Only | Top and Pants | Jumpsuit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Which garment type did you use? | 793 | 49.1% | 24.2% | 26.7% |

Responses to questions about the PALS design and ease of use were overwhelmingly positive (Table 2). When asked “is the fabric comfortable to wear?” 97.6% of patients responded “definitely/somewhat yes,” 1.6% were “neutral/no opinion,” and the remaining 0.8% answered “somewhat/definitely no.” When asked “were you able to move about easily when walking and in bed?” 97% responded “definitely/somewhat yes,” 1.4% replied “neutral/no opinion,” and 1.4% answered “somewhat/definitely no.” The question “was this easy to put on and remove?” garnered 94.6% “definitely/somewhat yes” responses with the remaining 3.4% choosing neutral and 2.1% replying “somewhat no/no.” When asked about ease of breast-feeding, 91.1% of patients responded “definitely/somewhat yes,” 7.7% replied “neutral/no opinion,” and 1.2% answered “definitely/somewhat no.” Patients’ responses to the PALS in comparison to a traditional hospital gown were, again, mostly positive. When asked “did you feel more comfortable and protected than the traditional hospital gown?” 96.4% of patients responded “definitely/somewhat yes,” 2.1% were neutral, and 1.5% replied “somewhat no/no.” When asked about preference in comparison with the traditional gown, 91.5% said “definitely/somewhat yes,” 3.6% were neutral, and 4.9% responded “somewhat/definitely no.” Regarding the modesty and coverage of the new gown, 96.1% responded “definitely/somewhat yes,” 3.5% were neutral, and 0.4% replied “somewhat/definitely no.”

Table 2.

Patient Survey Responses.

| Question | Na | Definitely Yes | Somewhat Yes | Neutral/No Opinion | Somewhat No | Definitely No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is the fabric comfortable to wear? | 797 | 86.1% | 11.5% | 1.6% | 0.3% | 0.5% |

| Were you able to move about easily when walking and in bed? | 794 | 80.2% | 16.8% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 0.3% |

| Were you able to breastfeed more easily? | 588 | 75.5% | 15.6% | 7.7% | 1.2% | - |

| Was this easy to put on and remove? | 796 | 78.3% | 16.3% | 3.4% | 1.8% | 0.3% |

| Did you feel more comfortable and protected in it than the usual hospital gown? | 794 | 83.0% | 13.4% | 2.1% | 1.0% | 0.5% |

| Do you prefer it to the usual hospital gown? | 790 | 79.8% | 11.7% | 3.6% | 1.9% | 3.0% |

| Did the new garment(s) provide more modesty/coverage than what you have previously experienced | 793 | 84.6% | 11.5% | 3.5% | 0.3% | 0.1% |

a Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

The final rating-scale question on the patient survey asked “compared to other hospital services, how important is the comfort of hospital clothing?” Eighty-nine percent of patients responded “very important,” 10.5% answered “somewhat important,” and 0.9% replied “not important” (Table 3). The free-response question regarding the option to modify the jumpsuit into a nightgown or to convert the pants/bottom into a night skirt garnered enthusiastic responses (Table 4).

Table 3.

Patient Responses Regarding Importance of Hospital Clothing.

| N | Very Important | Somewhat Important | Not Important | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compared with other hospital services, how important is comfort of the hospital clothing? | 763 | 88.6% | 10.5% | 0.9% |

Table 4.

Excerpts of Patient Responses to Open-Ended Questions.

| Question: did you like the option to modify the jumpsuit and pants into a nightgown or skirt? |

|---|

| I liked the option to change the jumpsuit into a night gown because it was easier for me to use the bathroom |

| Nightgown is more modest and comfy |

| Make wearing comfortable with 2 options |

| The jumpsuit is perfect. The texture is great as well |

| Very convenient for the bathroom |

| Very modern and ingenious |

| Yes I did use it as a night gown and was more effective and beneficial to me, but I love having options to modify the gown |

| Yes, I really like it because it protects your body |

| Yes, either way is comfortable. Easy to change |

| Yes, being able to modify and not be overly exposed was great |

| Yes, gives women of different religious backgrounds to maintain their clothing restrictions. I personally prefer pants, these were great! |

| Question: excerpts of patient responses to open-ended cue for additional comments |

| I like it, so cozy, not thin like the normal ones |

| I truly enjoyed the top. It is designed as a nightgown and is very comfortable for breastfeeding |

| Too frustrating to deal with the traditional gown, and heal myself, and take care of my newborn |

| Fits any body type |

| Fits my drains after surgery |

| Great idea! I loved the feeling of being covered up more |

| Made me feel like home. I love it. I wish I could take it move with me. Thank you |

The provider survey also culled a host of positive results (Table 5). When asked their opinion about the fabric design and print, 87.5% of providers answered “like a lot/somewhat like,” 4.4% were neutral, and the remaining 7.8% responded “somewhat dislike/do not like.” In terms of whether the fabric seemed comfortable, 94.4% replied “definitely/somewhat yes,” 2.7% were neutral, and 2.9% responded “somewhat/definitely no.” When asked whether the provider would prefer PALS to the traditional gown if he or she were to be a patient, 93.2% of providers replied “definitely/somewhat yes,” 3.4% remained neutral, and 3.4% said “somewhat/definitely no” (Table 6).

Table 5.

Provider Survey Responses.

| Survey Item | N | Very Easy | Somewhat Easy | Normal/Typical | Somewhat Difficult | Very Difficult |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regarding the top | ||||||

| Is the top easy to assist patient with donning and doffing (removal)? | 318 | 75.2% | 14.2% | 9.4% | 1.3% | – |

| Ease for examination with the back snaps, the front snaps, and the sleeves? | 317 | 72.9% | 18.3% | 7.3% | 1.6% | – |

| Rate the new top in comparison with standard current hospital gown | 319 | 70.5% | 21.0% | 7.5% | 0.9% | – |

| Regarding the pants: | ||||||

| Are the pants easy to assist patient with donning and doffing removal? | 294 | 71.4% | 15.7% | 11.9% | 1.0% | – |

| Regarding the jumpsuit | ||||||

| Is the jumpsuit easy to assist patient with donning and doffing (removal)? | 313 | 72.2% | 18.9% | 8% | 0.6% | 0.3% |

| Ease for examination with the back snaps, the front snaps and the sleeves? | 314 | 75.2% | 17.5% | 5.7% | 1.3% | 0.3% |

| Very Beneficial | Somewhat Beneficial | No Difference | Not Beneficial | N/A | ||

| Are the crotch snaps beneficial for examination ease and for bathroom use? | 309 | 68% | 16.8% | 6.5% | 4.9% | 3.9% |

| Are the crotch snaps beneficial for transition from pants to skirt and back to pants? | 309 | 69.3% | 21.0% | 2.9% | 1.9% | 4.9% |

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

Table 6.

Overall Provider Impressions of PALS System.

| Survey Item | N | Like A Lot | Somewhat Like | Neutral/No Opinion | Somewhat Dislike | Do Not Like |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What do you think of the fabric design and print? | 409 | 68.2% | 19.3% | 4.4% | 4.7% | 3.4% |

| Definitely Yes | Somewhat Yes | Neutral/No Opinion | Somewhat No | Definitely No | ||

| Does the fabric seem comfortable? | 412 | 79.1% | 15.3% | 2.7% | 1.9% | 1.0% |

|

If you were an inpatient, would you like to wear it over the traditional gown? |

409 | 72.9% | 20.3% | 3.4% | 1.0% | 2.4% |

Abbreviation: PALS, patient access linen system.

Regarding helping patients with donning and doffing the PALS top, 89.4% of providers perceived this to be “very/somewhat easy,” while 9.4% said “normal/typical,” and 1.3% found it “somewhat difficult.” Ease of examination with the top was reported to be “very/somewhat easy” by 91.2% of providers, while 7.3% remained neutral and 1.6% found it “somewhat difficult.” Regarding assisting patients with donning and doffing the PALS pants/bottom, 87.1% of providers found this to be “very/somewhat easy,” 11.9% found it “normal/typical,” and 1% found it “somewhat difficult.” No providers reported the top or the pants/bottom to be “very difficult.” The donning and doffing of the jumpsuit was found to be “very/somewhat easy” for 91.1% of providers, while 8% remained neutral, and only 0.9% said “somewhat/very difficult.” Ease of examination with the jumpsuit was reported as “very/somewhat easy” by 92.7% of providers, followed by 5.7% who were neutral, and 1.6% who responded “somewhat/very difficult.” Questions regarding specific features of the jumpsuit, such as the snaps and the ability to transform the pants to a skirt, and so on, were met with similar patterns of mostly positive responses (see Table 5). Responses and predominant themes (eg, comfort and coverage) for the open-ended item that asked for “additional comments” are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Excerpts of Provider Responses to Open-Ended Cue for Additional Comments.

| Question: staff open response to gown |

|---|

| It covers you back/butt which is great |

| Keep them |

| Much more comfortable fabric compared [to] gown, and better to wear while having visitors, moving around the floor |

| My patients loved it! |

| Patient seemed eager to wear gown over conventional gown |

| Patient was very comfortable and requested no modification to gown |

| My patients really like it and look like they feel better in it |

Discussion

The PALS patient gowning system created, patented, and studied in this pilot project enhanced patient and provider experience relative to traditional hospital attire based on the evidence from the mostly positive feedback it received. We attribute a portion of this success to the design itself, developed in concert with an obstetrician, gynecologist and a clothing designer/fabric artist. Considerations concerning anatomic access to various patient examinations, patient comfort, physical coverage, and freedom of movement and mobility/ambulation were taken into account during the design process. Admittedly, and in addition to helping the provider accomplish clinical examinations/duties, the PALS was initially created with the patient in mind. Our goal was to design a system of hospital attire that would enhance patient comfort, encourage a sense of control (via choice of garment and physical coverage), and lend a sense of normalcy to the hospital experience. We sought to close the gap (literally and metaphorically) between home and hospital and between patient and care providers in order to emphasize the patient’s inherent humanity. Our collective ability to care for our patients is enhanced through identification and connection. The PALS may be a small link in this process by ameliorating the difference between those giving and receiving care.

We have demonstrated thus far that the PALS contributes to overall enhancement of the patient experience and eases providers’ care of their patients. Hopefully, now and through future studies, we may find that PALS may assist in bringing patients and providers closer at a human level, since our patients have been or will be caregivers/providers and our providers, patients.

The PALS system assures that anatomic coverage is complete, thereby maintaining modesty and patient dignity. The lack of coverage associated with the traditional gown often causes the patient embarrassment and does not maintain his or her sense of dignity. (12) For medical personnel, the traditional hospital gown does not easily accommodate medical procedures (eg, connecting/changing IV lines and placing or removing tubes or catheters), nor does it provide ease when helping a patient change into a clean gown if the patient is connected to tubes or leads for medical treatment. Some gowns are not acceptable for radiologic procedures or for radiation therapy, thus making gown removal necessary. (13) Providers in our pilot not only endorsed the PALS system for ease of examination and assisting with donning and doffing, but they also responded quite positively to the fabric design and print. In addition, the majority of providers responded that if hospitalized, they would choose PALS over the conventional gown for their own use.

Patients’ general impressions of the PALS were clearly positive. Major themes included that it maintained their modesty, attended to their cultural/religious beliefs (for those preferring nightgown/skirt over pants), and that PALS “felt more like home.” The importance of hospital clothing was ranked higher than other hospital services by the vast majority of our patients in this pilot. We did not provide patients with examples of specific hospital services to compare to PALS, since we wanted them to respond based on their own experiences and whatever frame of reference was important to them. Patients were informed by their care provider that they were welcome to add any impressions they had regarding PALS (in the open comment section), the importance (if any) of hospital clothing, and PALS in relation to their overall hospital experience.

The mission of our study was validated by comments from patients such as: “I can’t believe this is finally being done” and “it’s just what we need.” Some specific comments were quite heartwarming, for example, “this really fits my drains” and “I don’t feel like just another case.” Despite patients asking countless times if they could take the gowns home, the loss rate was under 1%. We attribute this to actively engaging patients in the process and communicating our intent to enhance the hospital experience for them and for future patients.

Overall, patient evaluation with regard to flexibility/choice of garment type was quite positive as was maintenance of modesty/anatomic coverage. The comfort, feel, texture, and style of PALS were also highly rated by patients. Comfort is “a condition of ease or well-being that is affected by many factors.” (14) Comfort of clothing is multifactorial and is generally classified into psychological, physiological, and physical aspects. (4,15) For example, psychological comfort is interrelated with color, garment style, fashion, and suitability for an occasion. (4) The PALS takes into account style, functionality, color, and fabric weight/type for maximal thermoregulatory flexibility.

Of patients who breast-fed, many reported greater ease both feeding and pumping while maintaining modesty. Comments regarding breast-feeding were notably enthusiastic, for example, “finally someone is paying attention to nursing moms!,” “I can finally feel more connected to my baby during breast-feeding,” “the fabric is so soft,” and “I don’t feel like I’m hanging in the breeze anymore.”

Limitations of this study include confining the pilot population to obstetric/gynecologic patients, the lack of randomization, and the ability of participants to complete more than 1 survey per PALS item worn. Another possible limitation is that patients who agreed to take part in the study were more dissatisfied with the traditional gown. Approximately, 20% of all inpatients and 5% of all outpatients for the time period in question participated; nearly, all agreed to participate when PALS was offered; thus, the likelihood of this limitation, although not absent, is quite low. Our pilot study was limited to female patients cared for by providers in our obstetrics and gynecology department. Given that this was a pilot study and that we wanted to keep the number of confounding variables to a minimum, we targeted a female sample based on the evidence that female patients may be more sensitive to psychological comfort issues. (16 –19) An additional factor is that each patient acted as their own control, using the traditional hospital gown and one or more items from PALS during the course of their hospital stay or ambulatory care visit. Future research would randomize patients (all genders and service lines) and providers to the traditional gown or a PALS item to compare ease of use, functionality, patient preference, and other parameters examined in this pilot. A final limitation is that patients and providers could complete the survey more than once, although we believe this to have occurred with a relatively small percentage of patients/providers.

Strengths of our study include the PALS design itself, its attendant features aligning function and form, focus on provider and patient needs, and its development of a synergistic partnership between designer and practicing physician. Other strengths include preserved response anonymity and the overall diversity of our hospital population. Although we did not collect demographic information from our respondents, since our hospital serves one of the most diverse populations in the area (approximately 34% Caucasian, 20% African-American, 16% Asian, 24% Latino/Hispanic, and 6% other) and approximately 1 in 5 of our patients were surveyed, we have every reason to expect that the diversity of the study group was preserved during the study period. The response to the PALS, as shown by our pilot study, demonstrates consistent approval of and preference for the PALS over the traditional hospital gown, across multiple questions in both patient and provider surveys. As this was a prospective study where surveys were completed directly after patient or provider use of a PALS item, the data are less subject to recall bias. Furthermore, surveys were anonymous, thus allowing for honest responses and reduced observation bias. Finally, our studied patient base consisted of a large sample size with patients from diverse backgrounds. For example, a recent census taken from our unit indicates that our patient base is 35.5% Caucasian, 22.9% Asian, 20.1% Hispanic, and 20.1% black, with remaining ethnicities unknown (20). The inherent diversity of patients at this hospital is of benefit to our study as it allowed inclusion of perspectives across multiple cultures.

Further studies assessing PALS would examine the experience of adult and pediatric patients of all genders and across other service lines. Additionally, future research could evaluate the potential impact of PALS on behaviors affecting clinical outcomes, such as increased ambulation, and reduction in recovery time and length of stay. At our institution, we are currently developing an expansion model for PALS (eg, scaling the current design to fit children, men, and those of higher BMI) in order to continue our work in these areas.

Over the past several centuries, patient apparel as an element of self-expression and its effect on well-being and connectedness to providers have been largely overlooked. At the very least, there is much work to be done in these areas. Patients still wish to remain connected to the outside world with regard to social activities and other human endeavors. Thus, the expressive function of patient clothing is an idea whose time has not only come, but is long overdue. “Clothes make a statement about the individual” (21) including aesthetic and design elements. It is well known among artistic circles that colors are associated with emotions, and that certain colors can elicit positive responses such as relaxation and happiness. Aesthetic considerations may enhance a patient’s recovery process by lessening negative feelings of tension, stress, anger, or psychological depression (22,23).

Finally, the more comfortable and better one feels and looks in clothing, the more self-confidence generally follows. Patients who are more comfortable and confident in their attire are thus more likely to ambulate, and this can lead to a more rapid recovery and shorter length of stay. Not only does this have obvious health benefits but also a potential positive impact on health-care costs (24). More has been written about medical apparel than about patient attire. It is time for the dignity aspect of patient experience to drive innovation and to realize that simply because patients require medical care does not automatically relegate them to a lower status during their hospitalization (or ever). (25) The time has come for us to more closely examine the hospital experience regarding attire from the patient’s perspective. This first pilot study of PALS will hopefully advance the element and import of patient experience to take its rightful place next to clinical efficacy and patient safety in the triad of hospital experience. The PALS, we believe, is a solid, first step toward this goal.

Author Biographies

Jill Maura Rabin, MD, is a practicing obstetrician/gynecologist and urogynecologist for over three decades and is an active researcher, consultant, frequently invited lecturer and media spokesperson. Dr. Rabin holds seven patents and two copyrights for urogynecologic medical devices, is widely published and has authored three books on women’s health including “Mind Over Bladder”, a step-by-step guide to continence.

Katherine C Farner is currently a chief resident in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell. She received her undergraduate degree from Carnegie Mellon and her medical degree from the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern.

Alice H Brody is a prominent fiber artist and clothing designer based in New York City whose works have been displayed in various museums across the country. A graduate of Barnard College (AB) and NYU (Masters in Rehabilitation Counseling), she continues to explore the intersection of art and the human experience with various media.

Alexandra Peyser is currently in her third year of residency in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell. She received her undergraduate degree from Columbia University and her medical degree from the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology.

Myriam Kline as a research statistician, assists investigators in all aspects of their research, including study design, survey/questionnaire development, data analysis, and manuscript preparation for publication. Dr. Kline’s primary research interests include psychometrics, multivariate modeling, nonparametric methods, and survival analysis.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Psalm 118:22. Amplified Bible. USA: Classic Edition, Zondervan publishing house. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Turnock C, Kelleher M. Maintaining patient dignity in intensive care settings. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2001;17:144–54. doi:10.1054/iccn.2000.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tarafdar N. Selection of appropriate clothing in relation to garment comfort. Man-made Textiles India. 1995;38:17–211. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheng KPS, Cheung YK. Comfort in clothing. Textile Asia. 1994;25:48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 5. McDonald EG, Dounaevskaia V, Lee TC. Inpatient attire: an opportunity to improve the patient experience. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1865–7. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sfaronova V. The Hospital Gown Gets a Modest Redesign. Retrived 4 March, 2018. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/03/style/hospital-gown-parsons-care-wear.html. Accessed June 26, 2018.

- 7. Tedeschi B. Why do hospitals bare butts when there are better gowns around? Retrieved 3, 2018, from: https://www.statnews.com/2018/01/25/hospital-gowns-design/. Accessed June 26, 2018.

- 8. Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001570 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adogwa O, Elsamadicy AA, Fialkoff J, Cheng J, Karikari IO, Bagley C. Early ambulation decreases length of hospital stay, perioperative complications and improves functional outcomes in elderly patients undergoing surgery for correction of adult degenerative scoliosis. Spine. 2017;42:1420–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pua YH, Ong PH. Association of early ambulation with length of stay and costs in total knee arthroplasty: retrospective cohort study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93:962–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oldmeadow LB, Edwards ER, Kimmel LA, Kipen E, Robertson VJ, Bailey MJ. No rest for the wounded: early ambulation after hip surgery accelerates recovery. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:607–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Simone J. Combination Robe and Gown. U.S. Patent No. 6,032,288. 7 March 2000.

- 13. Orlando CJ. Garment. U.S. Patent No. 5,001,784. 26 March 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Collier B, Epps HH. Fabric hand and drape In: Collier BJ, Epps HH. eds. Textile Testing and Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall;259–280. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sarkar RK. Comfort properties of defense clothing. Man-made Textiles India. 1994;37:541–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tiggemann M, Andrew R. Clothing choices, weight, and trait self-objectification. Body Image. 2012;9:409–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rudd NA, Lennon SJ, Rudd NA. Body image and appearance-management behaviors in college women. Clothing Textiles Res J. 2000;18:152–162. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tiggemann M, Lacey C. Shopping for clothes: body satisfaction, appearance investment and clothing selection in female shoppers. Body Image. 2009;6:285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kwon YH, Parham ES. Effects of state of fatness perception on weight conscious women’s clothing practices. Clothing Textiles Res J. 1994;12:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Internal Survey Data, Long Island Jewish Medical Center, 2016.

- 21. Hoffman AM, Morris WW. Clothing for the Handicapped, the Aged, and Other People with Special Needs. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Pub Ltd;1979. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hemphill M. A note on adults’ color-emotion associations. J Genet Psychol. 1996;157:275–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baker HE. Music and color in the holistic healing of grief. J Holist Nurs. 1991;9:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311:2169–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matiti MR, Trorey GM. Patients’ expectations of the maintenance of their dignity. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(20):2709–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]