This cross-sectional survey study examines the association of childhood and lifetime recalled exposure of gender identity conversion efforts by both secular and religious professionals with adverse mental health outcomes in adulthood within the previous year and during their lifetime.

Key Points

Question

Is recalled exposure to gender identity conversion efforts (ie, psychological interventions that attempt to change one’s gender identity from transgender to cisgender) associated with adverse mental health outcomes in adulthood?

Findings

In a cross-sectional study of 27 715 US transgender adults, recalled exposure to gender identity conversion efforts was significantly associated with increased odds of severe psychological distress during the previous month and lifetime suicide attempts compared with transgender adults who had discussed gender identity with a professional but who were not exposed to conversion efforts. For transgender adults who recalled gender identity conversion efforts before age 10 years, exposure was significantly associated with an increase in the lifetime odds of suicide attempts.

Meaning

The findings suggest that lifetime and childhood exposure to gender identity conversion efforts are associated with adverse mental health outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Gender identity conversion efforts (GICE) have been widely debated as potentially damaging treatment approaches for transgender persons. The association of GICE with mental health outcomes, however, remains largely unknown.

Objective

To evaluate associations between recalled exposure to GICE (by a secular or religious professional) and adult mental health outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cross-sectional study, a survey was distributed through community-based outreach to transgender adults residing in the United States, with representation from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and US military bases overseas. Data collection occurred during 34 days between August 19 and September 21, 2015. Data analysis was performed from June 8, 2018, to January 2, 2019.

Exposure

Recalled exposure to GICE.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Severe psychological distress during the previous month, measured by the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (defined as a score ≥13). Measures of suicidality during the previous year and lifetime, including ideation, attempts, and attempts requiring inpatient hospitalization.

Results

Of 27 715 transgender survey respondents (mean [SD] age, 31.2 [13.5] years), 11 857 (42.8%) were assigned male sex at birth. Among the 19 741 (71.3%) who had ever spoken to a professional about their gender identity, 3869 (19.6%; 95% CI, 18.7%-20.5%) reported exposure to GICE in their lifetime. Recalled lifetime exposure was associated with severe psychological distress during the previous month (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.56; 95% CI, 1.09-2.24; P < .001) compared with non-GICE therapy. Associations were found between recalled lifetime exposure and higher odds of lifetime suicide attempts (aOR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.60-3.24; P < .001) and recalled exposure before the age of 10 years and increased odds of lifetime suicide attempts (aOR, 4.15; 95% CI, 2.44-7.69; P < .001). No significant differences were found when comparing exposure to GICE by secular professionals vs religious advisors.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that lifetime and childhood exposure to GICE are associated with adverse mental health outcomes in adulthood. These results support policy statements from several professional organizations that have discouraged this practice.

Introduction

Transgender persons are those whose sex assigned at birth differs from their gender identity, the inner sense of their own gender.1 According to a study by the Williams Institute,1 approximately 1.4 million (0.6%) adults in the United States identify as transgender. Transgender persons in the United States experience a disproportionately high prevalence of adverse mental health outcomes, including a 41% lifetime prevalence of self-reported suicide attempts.2,3,4

Studies5,6,7 have shown that gender-affirming models of care are associated with positive mental health outcomes among transgender people. Gender identity conversion therapy refers to psychological interventions with a predetermined goal to change a person’s gender identity to align with their sex assigned at birth.8 Several US states have passed legislation banning conversion therapy for gender identity.8 Professional organizations including the American Medical Association,9 the American Psychiatric Association,10 the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry,11 and the American Academy of Pediatrics12 have labeled the practice unethical and ineffective. Despite these policy statements, however, the question of whether to ban gender identity conversion therapy remains a contentious policy debate.

State-level conversion therapy bans have been focused on gender identity conversion efforts (GICE) by licensed mental health practitioners. Nonlicensed religious advisors have also advertised GICE, and it is unknown whether GICE by these 2 groups of practitioners are distinct in their effects on mental health.13

Because gender identity is thought to be stable after puberty for most transgender persons, few have supported use of GICE after pubertal onset.4 Some, however, have supported these efforts for prepubescent children, theorizing that gender identity may be more modifiable at this age.14 Increasingly, this approach has fallen out of favor, with the growing understanding that gender diversity is not a pathologic finding that requires modification.14 To our knowledge, there have been no studies evaluating the associations between exposure to GICE during either childhood or adulthood and adult mental health outcomes.

The current study used the largest cross-sectional survey to date of transgender adults living in the United States to assess whether recalled lifetime exposure to GICE is associated with adverse mental health outcomes, including suicide attempts. The study also assessed whether recalled childhood exposure to GICE before the age of 10 years is associated with adverse mental health outcomes in adulthood. We hypothesized that there would be associations between exposure to GICE by both secular and religious professionals and worse mental health outcomes.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

The 2015 US Transgender Survey15 is a cross-sectional survey that was conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE) between August 19 and September 21, 2015. It is the largest existing survey of transgender adults and was distributed via community-based outreach.15 The US Transgender Survey protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of California Los Angeles institutional review board, Los Angeles, California. The US Transgender Survey data set was organized and recoded as described in the NCTE report on the survey.15 The protocol for the present study was reviewed by the Fenway Institute institutional review board and was determined not to comprise human subjects research. Data analysis was performed from June 8, 2018, to January 2, 2019.

Study Population

The data set includes responses from 27 715 transgender adults residing in the United States, with representation from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and US military bases overseas. The NCTE report on the survey further characterizes recruitment strategies and the sample of respondents.15 Because the organizations that conducted outreach for the survey did not systematically document the number of individuals reached by their outreach efforts, a response rate could not be calculated.

Exposures

The primary exposure of interest was an affirmative response to the binary survey question, “Did any professional (such as a psychologist, counselor, or religious advisor) try to make you identify only with your sex assigned at birth (in other words, try to stop you being trans)?” This recalled exposure is herein referred to as GICE. Endorsement of lifetime exposure to GICE was examined among all those who confirmed having spoken to a professional about gender identity. Outcomes were compared among respondents who reported exposure to GICE before the age of 10 years with outcomes among those who endorsed lifetime exposure to therapy without GICE. Because the data set does not contain age of exposure to non-GICE therapy, participants with any lifetime exposure to non-GICE therapy were selected as the reference group in the analysis of those exposed to GICE before age 10 years. As data regarding ages of pubertal onset among respondents were not available, younger than 10 years was used as a cutoff to approximate a prepubertal population, with the understanding that there is significant individual variability in the age at onset of puberty.16,17 Furthermore, we examined whether there was a difference in outcomes between those who reported exposure to GICE from a secular professional compared with those who reported exposure to GICE from a religious advisor.

Outcomes

We compared respondents with and without recalled exposure to GICE with regard to the following binary mental health variables: severe psychological distress during the previous month (defined as a score of ≥13 on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, a cutoff that has been previously validated in US samples18); binge drinking during the previous month (defined as ≥1 day of consuming ≥5 standard alcoholic drinks on the same occasion, a threshold for which the rationale in alcohol research among transgender persons has been discussed in previous reports19); lifetime cigarette and illicit drug use (not including marijuana); suicidal ideation during the previous year; suicidal ideation with plan during the previous year; suicide attempt during the previous year; suicide attempt requiring inpatient hospitalization during the previous year; lifetime suicidal ideation; and lifetime number of suicide attempts (0, 1, or ≥2).

Control Variables

Demographic and socioeconomic variables were collected and analyzed as defined in the US Transgender Survey, including sex assigned at birth, present gender identity, sexual orientation, racial/ethnic identity according to the recoded NCTE categories reflecting those typically reported in the American Community Survey, age (both in integer form and using US census categories to capture cohort effects), family support of gender identity, relationship status (with partnered coded by these authors as binary and inclusive of both open and polyamorous relationships), educational achievement, employment status, and total household income. In supplemental analyses, we also controlled for exposure to sexual orientation conversion efforts undertaken by professionals.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS Studio, version 3.71, Basic Edition (SAS Institute). Participants were excluded from analyses if they did not report ever discussing their gender identity with a professional. Control variables were treated as unordered classification variables. Using the sample weights generated by the NCTE15 to improve generalizability by addressing sampling biases around age, educational level, and race/ethnicity, we generated descriptive statistics for control and outcome variables. Bivariate analyses comparing responses from transgender adults were conducted based on (1) whether or not they had any lifetime exposure to GICE, (2) whether they had experienced GICE before age 10 years vs never, and (3) whether GICE were conducted by a secular vs religious professional. These bivariate analyses were performed to detect potential confounders to control for in subsequent regression analysis. Except for age, all variables were categorical; thus, we used Rao-Scott χ2 tests for design-adjusted data with 1 df for bivariate comparisons. Age as an integer variable was nonnormally distributed; thus, bivariate comparison was performed with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Standard errors and 95% CIs were calculated for the prevalence estimates of exposure to GICE using the aforementioned 1.4 million persons as the total population estimate.1

Multivariable logistic regression models were conducted to test whether GICE were associated with the outcomes, adjusted for variables with significant differences between groups in the preceding bivariate analyses. These models also used survey weights generated by the NCTE for age, educational level, and race/ethnicity. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% CIs and 2-sided P values were reported, with a P < .001 threshold for significance.

Approximately 66 comparisons (between bivariate tests and logistic regression models) were made in each analysis. To reduce risk of type I error, a modified Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was performed, with resulting α = .001 (ie, .05 divided by 50). Using the full number of comparisons yields only a slightly lower α = .0008, which ultimately would not have altered the findings. We therefore selected an α = .001 for both ease of reading and also the statistical consensus that unmodified Bonferroni correction tends to be maximally conservative, thereby unnecessarily inflating type II error.20 Thus, hypothesis tests were 2-sided with corrected significance level P < .001 for both primary and secondary analyses, and the 95% CIs reported reflect this correction.

Respondents with missing data for exposure and outcome variables comprised less than 2% of the analytic samples and were therefore excluded without compensatory methods, as is widely considered acceptable for this degree of data completeness.21 Data were missing for less than 9% of each control variable, thereby obviating the need for imputation, which can introduce bias, especially when data are nonrandomly missing. There is debate about the degree of incompleteness that is acceptable without compensatory measures, and although individuals with incomplete data may be of particular interest, thresholds for missingness as high as 10% are considered to be acceptable.22

Results

Of the 27 715 US Transgender Survey respondents (mean [SD] age, 31.2 [13.5] years), 11 857 (42.8%) were assigned male sex at birth, and 3869 (14.0%; 95% CI, 13.3%-14.7%) reported exposure to GICE. Of 19 751 respondents who had discussed their gender identity with a professional, 3869 (19.6%; 95% CI, 18.7%-20.5%) reported exposure to GICE in their lifetime. Of these individuals, 1361 (35.2%; 95% CI, 32.7%-37.7%) who reported exposure to GICE stated that these were enacted by a religious advisor.

Demographic variables among exposed and unexposed respondents are shown in Table 1. After adjusting for statistically significant demographic variables, lifetime exposure to GICE was significantly associated with multiple adverse outcomes, including severe psychological distress during the previous month (aOR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.09-2.24; P < .001) and lifetime suicide attempts (aOR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.60-3.24; P < .001). (Table 2).

Table 1. Demographics of Participants With and Without Lifetime Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Effortsa.

| Characteristic | Did any professional try to make you identify only with your sex assigned at birth?b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P Valuec | ||

| Yes (n = 3869) | No (n = 15 882) | ||

| Sex assigned at birth | |||

| Male | 1143 (29.5) | 5576 (35.1) | <.001 |

| Female | 2726 (70.5) | 10 306 (64.9) | |

| Gender identity | |||

| Cross-dresser | 101 (2.6) | 721 (4.5) | <.001 |

| Transgender woman (male to female) or woman (birth-assigned male) | 2452 (63.4) | 8980 (56.5) | <.001 |

| Trangender man (female to male) or man (birth-assigned female) | 816 (21.1) | 4084 (25.7) | <.001 |

| Nonbinary or genderqueer (birth-assigned female) | 327 (8.5) | 1454 (9.2) | .11 |

| Nonbinary or genderqueer (birth-assigned male) | 173 (4.5) | 643 (4.0) | .25 |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Asexual | 339 (8.8) | 1034 (6.5) | <.001 |

| Bisexual | 753 (19.5) | 2570 (16.2) | <.001 |

| Gay, lesbian, or same gender-loving | 811 (21.0) | 3369 (21.2) | .75 |

| Heterosexual or straight | 838 (21.7) | 4124 (26.0) | <.001 |

| Pansexual | 531 (13.7) | 2039 (12.8) | .15 |

| Queer | 353 (9.1) | 1933 (12.2) | <.001 |

| Other | 245 (6.3) | 812 (5.1) | .003 |

| Racial/ethnicity | |||

| Alaska Native or American Indian | 49 (1.3) | 133 (0.8) | .02 |

| Asian, Asian American, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander | 62 (1.6) | 511 (3.2) | <.001 |

| Biracial, multiracial, or other | 79 (2.0) | 288 (1.8) | .38 |

| Black or African American | 477 (12.3) | 1926 (12.1) | .75 |

| Latino, Latina, or Hispanic | 609 (15.7) | 2219 (14.0) | .005 |

| White, Middle Eastern, or North African | 2593 (67.0) | 10 805 (68.0) | .23 |

| Census age cohort, y | |||

| 18-24 | 339 (8.8) | 1527 (9.6) | .11 |

| 25-44 | 1589 (41.1) | 5887 (37.1) | <.001 |

| 45-64 | 1408 (36.4) | 6141 (38.7) | .01 |

| ≥65 | 534 (13.8) | 2326 (14.6) | .19 |

| Family support of gender identity | |||

| Supportive | 1516 (39.2) | 8287 (52.2) | <.001 |

| Neutral | 672 (17.4) | 2659 (16.7) | .46 |

| Unsupportive | 1012 (26.2) | 2184 (13.7) | <.001 |

| Not asked | 549 (14.2) | 2752 (17.3) | <.001 |

| Relationship status | |||

| Partnered | 1754 (45.3) | 7845 (49.4) | <.001 |

| Educational level | |||

| Less than high school | 795 (20.5) | 1833 (11.5) | <.001 |

| High school graduate or GED | 904 (23.4) | 4290 (27.0) | <.001 |

| Some college or associate degree | 1137 (29.4) | 4883 (30.7) | .10 |

| Bachelor degree or higher | 1033 (26.7) | 4875 (30.7) | <.001 |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 1957 (50.6) | 9890 (62.3) | <.001 |

| Unemployed | 532 (13.7) | 1332 (8.4) | <.001 |

| Out of the labor force | 1346 (34.8) | 4578 (28.9) | <.001 |

| Unspecified | 35 (0.9) | 82 (0.5) | .01 |

| Total household income, $ | |||

| No income | 87 (2.2) | 432 (2.7) | .11 |

| 1-9999 | 503 (13.0) | 1608 (10.1) | <.001 |

| 10 000-24 999 | 1075 (27.8) | 2955 (18.6) | <.001 |

| 25 000-49 999 | 863 (22.3) | 3692 (23.2) | .22 |

| 50 000-99 999 | 728 (18.8) | 3732 (23.5) | <.001 |

| 100 000 or more | 430 (11.1) | 2468 (15.5) | <.001 |

| Unspecified | 184 (4.8) | 994 (6.3) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: GED, general equivalency diploma.

Descriptive statistics for transgender adults who reported receiving any therapy regarding gender identity, with bivariate comparisons of those with and without exposure to conversion efforts.

Professionals included psychologists, counselors, or religious advisors.

Rao-Scott χ2 tests were used for categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney test was used for comparison of age because of nonnormality.

Table 2. Outcomes for Those With Lifetime Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Effortsa.

| Outcome | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Suicidality in previous 12 mo | ||

| Ideation | 1.44 (1.03-2.02) | <.001 |

| Ideation with plan | 1.52 (1.09-2.14) | <.001 |

| Attempt | 1.49 (0.91-2.46) | .01 |

| Attempt requiring inpatient hospitalization | 1.62 (0.75-3.48) | .04 |

| Suicidality in lifetime | ||

| Ideation | 1.90 (1.12-3.23) | <.001 |

| Attempts | 2.27 (1.60-3.24) | <.001b |

| Mental health and substance use in previous month | ||

| Severe psychological distressc | 1.56 (1.09-2.24) | <.001 |

| Binge drinking | 0.88 (0.59-1.30) | .27 |

| Mental health and substance use in lifetime | ||

| Cigarette use | 1.18 (0.83-1.68) | .12 |

| Illicit drug use | 1.08 (0.75-1.54) | .50 |

Mental health outcomes among transgender adults exposed to gender identity conversion efforts compared with those who discussed gender identity with a professional without conversion efforts, adjusting for assigned sex at birth, gender identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, age cohort, family support of gender identity, partnership status, educational attainment, employment status, and total household income.

Ordinal logistic regression with outcome categories: 0, 1, and 2 or more.

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (defined as a score ≥13).

Overall, 206 (1.0%; 95% CI, 0.8%-1.2%) of those who reported discussing their gender identity with a professional also reported exposure to GICE before age 10 years. Demographics are shown in Table 3. After adjusting for statistically significant demographic variables, exposure to GICE before age 10 years was significantly associated with several measures of suicidality, including lifetime suicide attempts (aOR, 4.15; 95% CI, 2.44-7.69; P < .001) (Table 4).

Table 3. Demographics of Those With and Without Childhood Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Effortsa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P Valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reported Exposure to Conversion Efforts Before Age 10 y (n = 206)b | Reported Exposure to Any Lifetime Therapy Without Conversion Efforts (n = 15 882) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Alaska Native or American Indian | 5 (2.4) | 133 (0.8) | .04 |

| Asian, Asian American, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander | 3 (1.5) | 511 (3.2) | .22 |

| Biracial, multiracial or other | 8 (3.9) | 288 (1.8) | .05 |

| Black or African American | 5 (2.4) | 1926 (12.1) | <.001 |

| Latino, Latina, or Hispanic | 24 (11.6) | 2219 (14.0) | .39 |

| White, Middle Eastern, or North African | 161 (78.2) | 10 805 (68.0) | .002 |

| Census age cohort, y | |||

| 18-24 | 17 (8.2) | 1527 (9.6) | .59 |

| 25-44 | 110 (53.4) | 5887 (37.1) | <.001 |

| 45-64 | 76 (36.9) | 6141 (38.7) | .65 |

| ≥65 | 3 (1.5) | 2326 (14.6) | <.001 |

| Family support of gender identity | |||

| Supportive | 59 (28.6) | 8287 (52.2) | <.001 |

| Neutral | 37 (18.0) | 2659 (16.7) | .71 |

| Unsupportive | 80 (38.8) | 2184 (13.8) | <.001 |

| Not asked | 30 (14.6) | 2752 (17.3) | .34 |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 95 (46.1) | 9890 (62.3) | <.001 |

| Unemployed | 31 (15.0) | 1332 (8.4) | <.001 |

| Out of the labor force | 77 (37.4) | 4578 (28.8) | .01 |

| Unspecified | 2 (0.8) | 82 (0.5) | .68 |

| Total household income, $ | |||

| No income | 10 (4.9) | 432 (2.7) | .10 |

| 1-9999 | 47 (22.8) | 1608 (10.1) | <.001 |

| 10 000-24 999 | 57 (27.7) | 2955 (18.6) | .001 |

| 25 000-49 999 | 32 (15.5) | 3692 (23.2) | .01 |

| 50 000-99 999 | 32 (15.5) | 3732 (23.5) | .01 |

| 100 000 or more | 14 (6.8) | 2468 (15.5) | <.001 |

| Unspecified | 14 (6.8) | 994 (6.3) | .86 |

Descriptive statistics for transgender adults who reported receiving any therapy regarding gender identity, with bivariate comparisons for those with and without exposure to conversion efforts before age 10 years.

Individuals with unspecified age of reported exposure to conversion efforts, unspecified exposure to conversion efforts, and unspecified exposure to any therapy (missing data; n = 100) were excluded from this analysis.

Rao-Scott χ2 tests were used, and the Mann-Whitney test was used for comparison of age because of nonnormality.

Table 4. Outcomes for Those With Childhood Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Effortsa.

| Outcome | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Suicidality in previous 12 mo | ||

| Ideation | 2.03 (1.01-4.07) | <.001 |

| Ideation with plan | 2.82 (1.42-5.62) | <.001 |

| Attempt | 2.40 (0.87-6.62) | .005 |

| Attempt requiring inpatient hospitalization | 1.72 (0.26-11.24) | .34 |

| Suicidality in lifetime | ||

| Ideation | 1.90 (0.66-5.52) | .05 |

| Attempts | 4.15 (2.44-7.69) | <.001b |

| Mental health and substance use in previous month | ||

| Severe psychological distressc | 1.75 (0.72-4.24) | .04 |

| Binge drinking | 0.84 (0.33-2.14) | .54 |

| Mental health and substance use in lifetime | ||

| Cigarette use | 1.53 (0.66-3.56) | .09 |

| Illicit drug use | 1.76 (0.83-3.75) | .01 |

Mental health outcomes of transgender adults exposed to gender identity conversion efforts before age 10 years compared with those who discussed gender identity with a professional without conversion efforts in their lifetime, adjusted for age cohort, sex assigned at birth, race/ethnicity, family support of gender identity, employment status, and total household income.

Ordinal logistic regression with outcome categories: 0, 1, and 2 or more.

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (defined as a score ≥13).

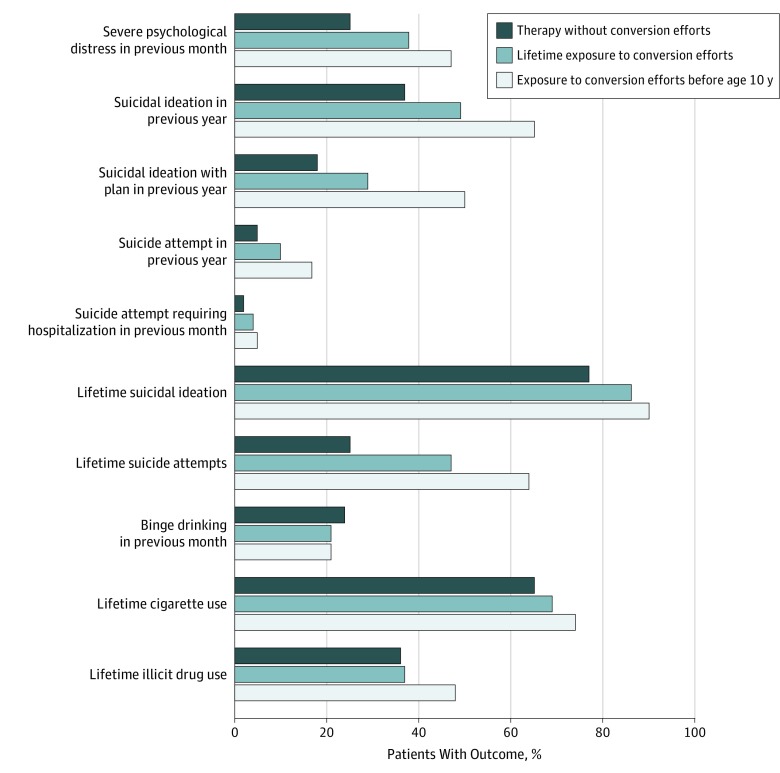

Raw frequencies of outcome variables among exposure groups are shown in the Figure. There were no statistically significant differences in outcomes between those who were exposed to GICE enacted by religious advisors and those exposed to GICE by secular professionals (all aOR, P > .001) (eTable 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Figure. Mental Health Outcomes Among Those With and Without Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Efforts.

Raw frequencies for outcome variables among those with a lifetime history of non–gender identity conversion efforts therapy, lifetime history of exposure to gender identity conversion efforts, and exposure to conversion efforts before age 10 years. Severe psychological distress in the previous month was defined as a score of 13 or more on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, a cutoff that has been previously validated in US samples.17 Binge drinking was defined as at least 1 or more day of consuming 5 or more standard alcoholic drinks on the same occasion, a threshold for which the rationale in alcohol research among transgender people has been discussed in previous reports.18 Illicit drug use excludes marijuana use.

We also repeated all analyses adjusting for lifetime exposure to sexual orientation conversion efforts, defined as a positive response to the survey question, “Did any professional (such as a psychologist, counselor, or religious advisor) ever try to change your sexual orientation or who you are attracted to (such as try to make you straight or heterosexual)?” After this adjustment, both lifetime exposure (aOR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.38-2.80; P < .001) and childhood exposure (aOR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.55-6.02; P < .001) to GICE were associated with increased odds of lifetime suicide attempts but not with the other outcome variables (eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement). Because this question was unclear regarding the referent gender (sex assigned at birth vs gender identity) when defining sexual orientation conversion efforts, we refer to the models not adjusted for this variable throughout the article.

Discussion

This study was the first, to our knowledge, to show an association between exposure to GICE (lifetime and childhood) and adverse mental health outcomes among transgender adults in the United States. We found that recalled lifetime exposure to GICE was highly prevalent among adults: 14.0% of all transgender survey respondents and 19.6% of those who had discussed gender identity with a professional reported exposure to GICE.

The Generations Study23 by the Williams Institute found that 6.7% of sexual minority group adults in the United States reported lifetime exposure to conversion efforts for sexual orientation.23 Based on the findings of the current study, it appears that transgender people are exposed to GICE at high rates, perhaps even higher than the percentage of cisgender nonheterosexual individuals who are exposed to sexual orientation conversion efforts, although direct comparisons are not possible. One potential explanation for this is that compared with persons in the sexual minority group, many persons in the gender minority group must interact with clinical professionals to be medically and surgically affirmed in their identities. This higher prevalence of interactions with clinical professionals among people in the gender minority group may lead to greater risk of experiencing conversion efforts.

One study24 showed that conversion efforts for sexual orientation were associated with an increased risk of depression and suicidal ideation. The current study was the first, to our knowledge, to find associations between any type of conversion efforts and both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. A plausible association of these practices with poor mental health outcomes can be conceptualized through the minority stress framework; that is, elevated stigma-related stress from exposure to GICE may increase general emotion dysregulation, interpersonal dysfunction, and maladaptive cognitions.25 Of note, having a lifetime suicide attempt was a more common outcome compared with severe psychological distress during the previous month, a result that was likely attributable to the time frames during which these variables were defined. Although this study suggests that exposure to GICE is associated with increased odds of suicide attempts, GICE are not the only way in which minority group stress manifests, and thus other factors are also likely to be associated with suicidality among gender-diverse people.

Respondents from more socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds (eg, low educational attainment or low household income) more commonly reported exposure to GICE. These individuals may have been more likely to receive GICE, or exposure to GICE may have been so damaging that they were impaired in educational, professional, and economic advancement. The cross-sectional nature of this study limits further interpretation. This finding warrants additional attention in the context of nationally representative data showing lower educational attainment and lower income among transgender people in the United States compared with their cisgender counterparts.26

Given the considerable debate surrounding the merits of GICE for prepubertal youth,4 we examined recalled early exposure to GICE (ie, before age 10 years) and found this to be less prevalent, with 1% of those who had ever discussed gender identity with a professional reporting that they had been exposed before age 10 years. Many experts have expressed concern that early exposure to GICE may lead to persistent feelings of shame because of physicians and parents defining gender-expansive experience as unacceptable.4 A study27 in Canada found a higher prevalence of shame-related feelings among youth treated with GICE. Both family and peer rejection of a child’s gender identity have been associated with adverse mental health outcomes.27,28,29,30 Extending those findings, the current study showed that recalled early exposure to GICE was associated with adverse mental health outcomes, including lifetime suicide attempts, compared with discussion of gender identity with a professional and no exposure to conversion efforts. Although not compared directly, the aOR of lifetime suicide attempts was higher for those exposed to GICE before age 10 years than the aOR for those with lifetime exposure, suggesting that rejection of gender identity may have more profound consequences at earlier stages of development. Further research is needed to better understand the associations between stage of development at time of exposure to GICE and risk of lifetime suicide attempts.

Our results support the policy positions of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,11 the American Psychiatric Association,10 the American Academy of Pediatrics,12 and the American Medical Association,9 which state that gender identity conversion therapy should not be conducted for transgender patients at any age. Our finding of no difference in mental health outcomes between respondents who received GICE from a secular-type professional and those who received it from a religious advisor suggests that any process of intervening to alter gender identity is associated with poorer mental health regardless of whether the intervention occurred within a secular or religious framework.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include its sample size, more than 90% completeness in the data set, and participants from a wide geographic area within the United States. Limitations include its cross-sectional study design, which precludes determination of causation. It is possible that those with worse mental health or internalized transphobia may have been more likely to seek out conversion therapy rather than non-GICE therapy, suggesting that conversion efforts themselves were not causative of these poor mental health outcomes. This interpretation, however, would also imply a mechanism whereby societal rejection leads to internalized transphobia and life-threatening adult mental health outcomes.

We also lack data regarding the degree to which GICE occurred (eg, duration, frequency, and forcefulness of GICE, as well as what specific modalities were used). If a sizable proportion of those reporting exposure to GICE in the current study experienced relatively mild or infrequent conversion efforts, this might suggest the findings of this study are even more concerning (ie, even mild or infrequent conversion efforts were associated with adverse mental health outcomes, including suicide attempts). Because the survey question asked about exposure to GICE from professionals, it is possible that exposures to GICE from other people (eg, family members) were not captured. Although the survey included respondents from a wide geographic distribution across the United States, these participants were not recruited via random sampling. The sample may not be nationally representative. Data are also lacking regarding when respondents entered puberty, making it difficult to define a prepubertal sample; we therefore set an approximate prepubertal cutoff at age 10 years. In this study, we compared exposure to GICE before age 10 years with lifetime exposure to non-GICE therapy. Although it would have been ideal to compare the former group with those who experienced non-GICE therapy before age 10 years, we lacked data on the age at which respondents were exposed to non-GICE therapy.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that recalled exposure to GICE is associated with adverse mental health outcomes in adulthood, including severe psychological distress, lifetime suicidal ideation, and lifetime suicide attempts. In this study, exposure to GICE before age 10 years was associated with adverse mental health outcomes compared with therapy without conversion efforts. Results from this study support past positions taken by leading professional organizations that GICE should be avoided with children and adults.

eTable 1. Demographics for Those With Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Efforts by a Secular or Religious Advisor.

eTable 2. Outcomes Comparison for Secular and Religious Gender Identity Conversion Efforts

eTable 3. Outcomes for Those With Lifetime Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Efforts

eTable 4. Outcomes for Those With Childhood Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Efforts

References

- 1.Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, Brown TN. How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States. Los Angeles, California: The Williams Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckwith N, McDowell MJ, Reisner SL, et al. Psychiatric epidemiology of transgender and nonbinary adult patients at an urban health center. LGBT Health. 2019;6(2):51-61. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turban JL, Ehrensaft D. Research review: gender identity in youth: treatment paradigms and controversies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018:59(12):1228-1243. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vries AL, McGuire JK, Steensma TD, Wagenaar EC, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):696-704. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durwood L, McLaughlin KA, Olson KR. Mental health and self-worth in socially transitioned transgender youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(2):116-123.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson KR, Durwood L, DeMeules M, McLaughlin KA. Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20153223. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byne W. Regulations restrict practice of conversion therapy. LGBT Health. 2016;3(2):97-99. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Medical Association Health care needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. H-160.991. 2017. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/gender%20identity?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-805.xml Accessed April 5, 2019.

- 10.Byne W, Bradley SJ, Coleman E, et al. ; American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Treatment of Gender Identity Disorder . Report of the American Psychiatric Association Task Force on treatment of gender identity disorder. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(4):759-796. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9975-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Conversion Therapy. 2018. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Policy_Statements/2018/Conversion_Therapy.aspx. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- 12.Rafferty J; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Adolescence; Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness . Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20182162. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salzman J. Colorado’s Ban on “Conversion Therapy” Won’t Stop the Catholic Church. Rewire.News. Published January 28, 2019. https://rewire.news/article/2019/01/28/colorados-ban-on-conversion-therapy-wont-stop-the-catholic-church/. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- 14.Drescher J, Pula J. Ethical issues raised by the treatment of gender-variant prepubescent children. Hastings Cent Rep. 2014;44(suppl 4):S17-S22. doi: 10.1002/hast.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herman-Giddens ME, Steffes J, Harris D, et al. Secondary sexual characteristics in boys: data from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1058-e1068. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman-Giddens ME, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, et al. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network. Pediatrics. 1997;99(4):505-512. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(suppl 1):4-22. doi: 10.1002/mpr.310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert PA, Pass LE, Keuroghlian AS, Greenfield TK, Reisner SL. Alcohol research with transgender populations: a systematic review and recommendations to strengthen future studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:138-146. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sedgwick P. Multiple hypothesis testing and Bonferroni’s correction. BMJ. 2014;349:g6284. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong Y, Peng C-YJ. Principled missing data methods for researchers. Springerplus. 2013;2(1):222. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett DA. How can I deal with missing data in my study? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25(5):464-469. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallory C, Brown TNT, Conron KJ Conversion therapy and LGBT youth. Published January 2018. Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Conversion-Therapy-LGBT-Youth-Jan-2018.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- 24.DeLeon PH. Appropriate therapeutic responses to sexual orientation. Proceedings of the American Psychological Association, Inc, for the legislative year 1997: minutes of the annual meeting of the Council of Representatives. Am Psychol. 1998;53:882-939. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? a psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(5):707-730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer IH, Brown TN, Herman JL, Reisner SL, Bockting WO. Demographic characteristics and health status of transgender adults in select US regions: behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(4):582-589. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallace R, Russell H. Attachment and shame in gender–nonconforming children and their families: toward a theoretical framework for evaluating clinical interventions. Int J Transgenderism. 2013;14(3):113-126. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2013.824845 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;23(4):205-213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):943-951. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Vries AL, Steensma TD, Cohen-Kettenis PT, VanderLaan DP, Zucker KJ. Poor peer relations predict parent- and self-reported behavioral and emotional problems of adolescents with gender dysphoria: a cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(6):579-588. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0764-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Demographics for Those With Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Efforts by a Secular or Religious Advisor.

eTable 2. Outcomes Comparison for Secular and Religious Gender Identity Conversion Efforts

eTable 3. Outcomes for Those With Lifetime Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Efforts

eTable 4. Outcomes for Those With Childhood Exposure to Gender Identity Conversion Efforts