Abstract

Purpose: Sexual minority (SM) individuals are more likely to experience mental health concerns than heterosexual individuals. However, little is known to date about the psychological needs of SM cancer survivors. The objective of this systematic review was to identify whether SM cancer survivors experience disparate psychological outcomes compared with heterosexual cancer survivors.

Methods: PubMed/MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, and ProQuest databases were searched systematically to identify studies that compared mental health outcomes between SM and heterosexual survivors. A standardized data extraction form was used to extract data from eligible articles. The Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies was used to assess study quality.

Results: Twelve studies met the inclusion criteria and assessed distress, depression, anxiety, perceived stress, and mental and emotional quality of life (QOL). Most studies enrolled survivors diagnosed either with female breast cancer or with prostate cancer. Most studies reporting on mental health among women found no differences between SM and heterosexual survivors. Studies conducted among men found that SM survivors experienced higher distress, depression, and anxiety, and lower emotional/mental QOL than heterosexual survivors.

Conclusion: The findings of the present synthesis suggest that mental health disparities may exist among SM men diagnosed with cancer, particularly prostate cancer. More research is required to identify mental health disparities among SM survivors diagnosed with other cancers, as well as predisposing and protective factors. In addition, mental health screening and interventions are needed for SM men after cancer diagnosis.

Keywords: cancer, cancer survivors, health care disparities, mental health, sexual minorities

Introduction

Sexual minority (SM) individuals include those who identify as non-heterosexual (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, or queer), as well as those who do not self-identify as non-heterosexual but are attracted to individuals of the same sex or engage in same-sex sexual behavior (e.g., men who have sex with men [MSM] and women who have sex with women).1 It is estimated that between 2% and 3.2% of adults in North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia identify as non-heterosexual.2–5 For example, more than 8 million adults in the United States self-identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual in 2011.6 There is considerable evidence that SM populations are at greater risk for psychological distress and impairment compared with heterosexual populations.7 SM individuals are twice as likely to be depressed,8 ∼2.5 times more likely to attempt suicide,8 and experience higher rates of anxiety disorders and co-morbid mental health conditions compared with their heterosexual peers.8,9

The higher prevalence of mental health conditions among SM individuals may be due to chronic and specific stressors that they face, including prejudice, discrimination, anticipated rejection, and social marginalization (i.e., “minority stress”), as a result of their belonging to a stigmatized social group.10–12 Minority stress has been linked to poor mental health outcomes13–15 and is hypothesized to increase risk for poor mental health over the lifetime through disruption of social relationships and emotion regulation strategies.16 For example, there is evidence that minority stressors such as harassment, rejection, and discrimination are associated with increased shame, poorer quality peer relationships, and loneliness, which may contribute to psychological distress among SM individuals.17

In addition, SM individuals are more likely than heterosexual individuals to engage in cancer-related risk behaviors such as smoking,18–20 alcohol use,18–20 and physical inactivity,18,21 and there is evidence that lesbian and bisexual women are less likely to receive screening for cervical cancer and breast cancer than heterosexual women.19,20,22 Further, emerging research suggests that SM individuals are at increased risk for certain cancers, with SM men at disproportionate risk for anal cancer7 and skin cancer,23 and both SM men and women experiencing greater incidence of colorectal cancer.24 However, little is known about the psychological needs of SM individuals after a cancer diagnosis. Psychosocial oncology research has broadly defined “distress” among patients with cancer (commonly known as “cancer survivors”25,26) as a “multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (i.e., cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment.”27 Psychological distress is common among patients with cancer, with one study in the United States finding an overall prevalence of 35.1% across cancer sites.28 However, it is unclear whether SM cancer survivors experience rates of distress and mental health concerns similar to heterosexual survivors.

In addition to experiencing higher baseline rates of psychological concerns,8,9 SM cancer survivors may experience additional stress within the context of cancer care that has a negative impact on their engagement in health care services and long-term treatment outcomes. For example, SM individuals frequently experience interpersonal and structural barriers to health care and preventive services, such as difficulty obtaining health insurance and lack of provider training in sexual and gender minority (SGM) health needs.29 Further, the Institute of Medicine has reported that SGM individuals routinely receive inadequate care in medical settings, including verbal abuse and treatment refusal.29 Accordingly, SM cancer survivors are less likely to be satisfied with their health care compared with heterosexual cancer survivors, report concerns about disclosing their sexual orientation to medical providers, and perceive providers as having little knowledge or interest in the issues that SM individuals face in coping with cancer.30,31 In addition to augmenting the minority stress of SM individuals, experiences of marginalization or discrimination in health care can have lasting negative effects, resulting in reduced health care utilization among SM individuals and limited disclosure of sexual orientation to providers. This lack of disclosure can compromise medical treatment and has been prospectively associated with poorer psychological health.32,33

Gaining a better understanding of the mental health needs of SM cancer survivors is of critical importance, as psychological distress and mental health disorders have been prospectively linked with decreased treatment adherence, faster disease progression, and higher mortality among cancer survivors.34,35 In addition, research has found that cancer survivors diagnosed with depression incur significantly greater health care costs, including outpatient, hospital, emergency department, and prescription services, compared with non-depressed survivors.36,37 In their 2015 review, Quinn et al.38 summarized cancer epidemiology, detection, treatment, and psychosocial concerns among SGM cancer survivors; however, this narrative review did not explicitly examine mental health outcomes or compare psychological outcomes between SM and heterosexual survivors. In a 2017 position statement,39 the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) stated: “there is insufficient knowledge about the health care needs, health outcomes, lived experiences, and effective interventions to improve outcomes for SGM individuals … research is needed to determine whether patterns of risk … and outcomes after a cancer diagnosis vary by SGM status.”39

In consideration of the ASCO position statement,39 the purpose of the current systematic review was to identify whether SM cancer survivors experience disparate psychological outcomes compared with heterosexual cancer survivors. This is the first known systematic review to examine disparities in mental health between SM and heterosexual cancer survivors.

Methods

Search strategy

PubMed/MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses databases were searched systematically by using a pre-defined search strategy developed with the assistance of a research librarian. The search was limited to articles published after 1973, the year in which homosexuality was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.40 Combinations of terms associated with cancer survivorship, sexual identity, and psychological outcomes were used. The final search strategy is presented in Table 1. Hand searching was also conducted by reviewing reference lists from eligible articles and using the Web of Science Citation Search to forward-search from eligible articles. The systematic search was originally conducted on January 17, 2017 and re-run on June 11, 2018 to identify any new articles published since the initial search. No new articles were identified for inclusion after the second search.

Table 1.

Search Strategy

| PubMed/MEDLINE |

| 1. (Malignanc* OR oncolog* OR cancer OR neoplasms[MH]) |

| 2. ((Sexual AND (minority OR minorities)) OR LGB* OR gay OR bisexual OR lesbian OR “sexual orientation” OR “men who have sex with men” OR “women who have sex with women” OR homosexuality[MH] OR bisexuality[MH]) |

| 3. (Heterosexual OR heterosexuality[MH]) |

| 4. (Depression OR anxiety OR distress OR stress OR “mental health” OR “adjustment disorder” OR (psychological AND (stress OR distress)) OR depression[MH] OR depressive disorder[MH] OR anxiety[MH] OR anxiety disorders[MH] OR adjustment disorder[MH] OR stress, psychological[MH] OR adaptation, psychological[MH]) |

| 5. 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 |

| PsycINFO/CINAHL/Web of Science/ProQuest |

| 1. (Malignanc* OR oncolog* OR cancer OR neoplasms) |

| 2. ((Sexual AND (minority OR minorities)) OR LGB* OR gay OR bisexual OR lesbian OR “sexual orientation” OR “men who have sex with men” OR “women who have sex with women” OR homosexuality OR bisexuality) |

| 3. (Heterosexual OR heterosexuality) |

| 4. (Depress* OR anxiety OR distress OR stress OR “mental health” OR “adjustment disorder” OR (psychological AND (stress OR distress OR adaptation))) |

| 5. 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 |

MH, MeSH terms.

Study selection

Citations from all search results were downloaded into EndNote X7 reference management software.41 After removing duplicate citations, study titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine whether studies met pre-determined eligibility requirements. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were written in English and quantitatively compared mental health outcomes of a SM group with a heterosexual group among cancer survivors. Cancer survivors were defined as adults aged 18 or older at any stage after a cancer diagnosis (i.e., active treatment through long-term survivorship or end of life). Psychological outcomes were defined broadly as: depression (e.g., assessment of depression symptoms, diagnosis of a depressive disorder, or use of anti-depressant medications), anxiety (e.g., assessment of anxiety symptoms, diagnosis of anxiety or an anxiety-related disorder, or use of anti-anxiety medications), adjustment disorders (e.g., diagnosis of an adjustment disorder), psychological distress (e.g., assessment of broad emotional suffering of a psychological, social, or spiritual nature),27 stress (e.g., assessment of perceived stress or symptoms of stress in response to physical, mental, or emotional pressures),26,42 and emotional or mental components of quality of life (QOL) instruments (i.e., assessment of emotional well-being and its impact on daily functioning and life satisfaction).43,44

Dissertations and theses were included in the review. Studies published in a language other than English, book chapters, literature reviews, conference abstracts, and gray literature (not including dissertations and theses) were excluded. In addition, studies that did not include a comparison group of heterosexual cancer survivors were excluded. To allow for the direct comparison of mental health outcomes between SM and heterosexual samples, only studies that provided quantitative summary measures characterizing mental health in each group were included; thus, exclusively qualitative articles were not eligible for the review.

Data extraction

A standardized data extraction form was used to extract salient study data from eligible articles, including study location, design, sample size, participant characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity, age, gender identity, SM status, and cancer diagnosis), psychological outcomes measured, and data analytic methods. Data were extracted by the first author and reviewed independently for accuracy by the second author (S.H.B.) and a research assistant. Multiple quality assessment tools were considered. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies was selected for this study because it was specifically designed for the critical appraisal of cross-sectional studies,45 the design utilized by all but one study included in the review. Question 3, “Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way?” and Question 4, “Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition?” pertain to epidemiological studies examining the relationship between an exposure and disease, and were not applicable to the current review.

Included studies were assigned a rating of “Yes,” “No,” or “Unclear” on each of six criteria based on guidelines provided by the JBI. The six criteria on which studies were rated are: (1) report of inclusion criteria, (2) description of study subjects, (3) identification of confounding factors, (4) management of confounding factors, (5) use of valid and reliable outcome measures, and (6) use of appropriate data analysis techniques. As stated in the preceding sections, the present review focused on reporting mental health outcomes of SM compared with heterosexual cancer survivors. Therefore, ratings for identification and management of confounding factors, outcome measures, and analytic techniques were assigned at the outcome level rather than the study level, based on the specific comparisons of interest between SM and heterosexual survivors. Two authors (J.R.G. and K.T.G.S.) assessed studies independently for quality and met to identify discrepancies and obtain consensus.

Results

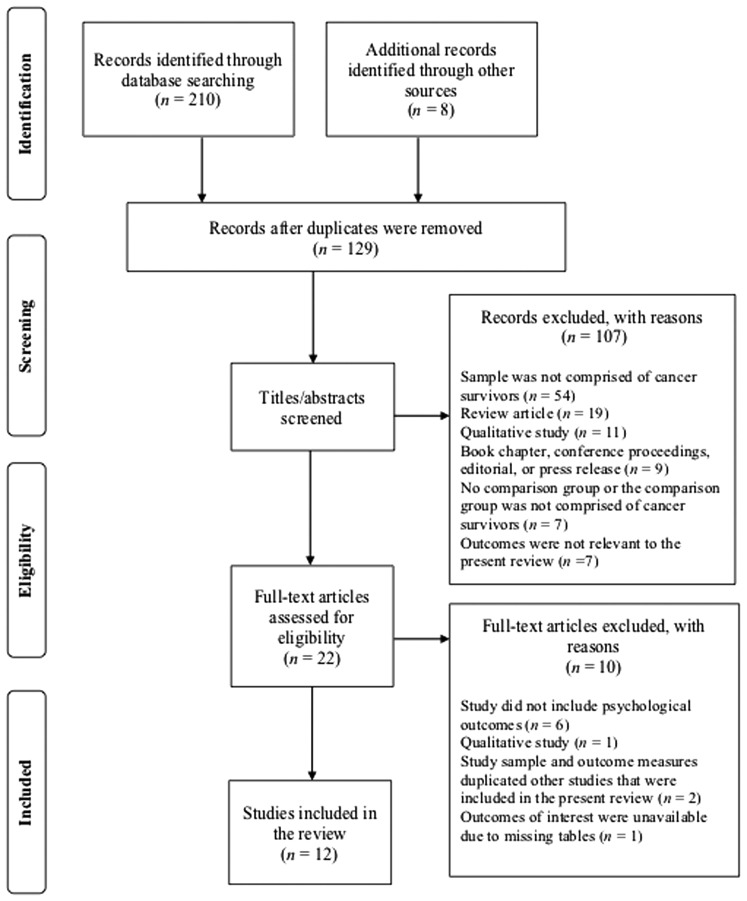

Figure 1 illustrates the study identification, screening, eligibility, and selection process from the final systematic search. Two hundred and eighteen records were identified via database searches and hand searching. Eighty-nine of these records were identified as duplicates, yielding 129 studies left to be screened for potential inclusion. After screening of titles and abstracts, 107 studies were excluded based on the designated inclusion/exclusion criteria. After review of the full text for the remaining 22 studies, an additional 10 were excluded. Twelve studies were eligible for inclusion in this synthesis.46–57 Study descriptions and results are presented in Table 2.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of study identification and selection process.

Table 2.

Summary of Studies Comparing Mental Health Outcomes Among Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Cancer Survivors

| Study | Study description | Sample recruitment and characteristics | Study methods and outcomes | Results | Quality assessmenta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies conducted with sexual minority women | |||||

| Arena et al., 200646 | Cross-sectional study comparing psychosocial responses to breast cancer treatment between lesbian and heterosexual women | Lesbian women (N = 39) recruited nationwide using flyers distributed via physicians, women's networks, and lesbian community resource centers Mean age: 48.3 (SD = 8.3) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White: 92.3% Hispanic: 5.1% Black: 2.6% Heterosexual women (N = 39) participating in one of two existing studies recruited from Miami-area hospitals and medical practices Mean age: 49.4 (SD = 8.9) Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White: 74.4% Hispanic: 10.2% Black: 15.4% |

Matched lesbian sample to heterosexual sample based on age, ethnicity, stage of disease, and time since diagnosis Compared samples on depression using CES-D scale Conducted analysis of covariance controlling for medical and demographic variables that significantly differed between groups (education and receipt of radiation therapy) |

No statistically significant difference in depression symptoms was found between lesbian women (M = 11.9, SD = 2.1) and heterosexual women (M = 15.8, SD = 2.1) when controlling for education and radiation status | Six of six criteria met |

| Boehmer et al., 201247 | Cross-sectional study comparing anxiety and depression between SMW and heterosexual women breast cancer survivors | SMW (N = 69) recruited from Massachusetts Cancer Registry (RSMW) Mean age: 55.9 (SD = 8.3) Race/ethnicity: White: 94.2% SMW (N = 112) convenience sample recruited nationwide via community outreach, internet advertising, and print publications Mean age: 55.1 (SD = 8.7) Race/ethnicity: White: 86.6% Heterosexual women (N = 257) recruited from Massachusetts Cancer Registry (RH) Mean age: 62.7 (SD = 11.0) Race/ethnicity: White: 85.2% |

Compared RSMW with RH on depression and anxiety using the HADS; conducted t-tests for each subscale Compared self-reported use of antidepressants and anxiety medications among RSMW and RH using χ2 tests Also used stepwise regression to examine the relationship between sexual orientation and HADS subscales for both registry (RSMW vs. RH) and combined samples (RSMW + SMW convenience sample vs. RH), including numerous demographic and clinical variables in the model |

For HADS depression subscale, no statistically significant difference was found between RSMW (M = 3.1, SD = 3.2) and RH (M = 3.2, SD = 3.0) For HADS anxiety subscale, no statistically significantly difference was found between RSMW (M = 5.3, SD = 3.7) and RH (M = 5.2, SD = 3.9) Significantly more RSMW reported current use of antidepressant medication compared to RH (40.6% vs. 21.0%) No statistically significant difference was found between RSMW and RH women on current use of anti-anxiety medication (8.7% vs. 7.4%) For stepwise regression analyses, no statistically significant relationship was found between sexual orientation and HADS depression for the registry or combined sample when controlling for age, marital status, education, income, insurance, co-morbidities, stage, receipt of radiation, use of mood stabilizer, discrimination, and four interactions between sexual orientation and stage, radiation, mood stabilizer, and discrimination There was a significant relationship between sexual orientation and HADS anxiety for the combined sample, but not for the registry sample, when controlling for age, marital status, income, employment, neighborhood household income, discrimination, use of mood stabilizer, and two interactions between sexual orientation and marital status and sexual orientation and employment, with the combined SMW sample reporting significantly less anxiety than RH women |

Six of six criteria met |

| Boehmer et al., 201248 | Cross-sectional study examining the association between sexual orientation and QOL among SMW and heterosexual women breast cancer survivors | SMW (N = 69) recruited from Massachusetts Cancer Registry (RSMW) Mean age: 55.9 (SD = 8.3) Race/ethnicity: White: 94.2% SMW (N = 112) convenience sample recruited nationwide via community outreach, internet advertising, and print publications Mean age: 55.1 (SD = 8.7) Race/ethnicity: White: 86.6% Heterosexual women (N = 257) recruited from Massachusetts Cancer Registry (RH) Mean age: 62.7 (SD = 11.0) Race/ethnicity: White: 85.2% |

Compared RSMW with RH on mental QOL using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) MCS; conducted t-test Used stepwise regression to examine the relationship between sexual orientation and MCS for both registry (RSMW vs. RH) and combined samples (RSMW + convenience sample vs. RH), including age, employment, and income in the model |

On the MCS, no statistically significant difference was found between RSMW (M = 48.8 SD = 10.1) and RH (M = 50.3, SD = 10.4) In stepwise regression analyses, sexual orientation was not significantly associated with MCS for either the registry or the combined sample when controlling for age, employment, and income |

Six of six criteria met |

| Jabson and Bowen, 201449 | Cross-sectional study comparing perceived stress between SMW and heterosexual breast cancer survivors | SMW (defined as lesbian, bisexual, queer, and women-loving) breast cancer survivors (N = 68) recruited online through breast cancer survivor groups, websites, discussion boards, and organizations; through lesbian-specific health organizations, discussion boards, and newsletters; as well as using hard-copy materials distributed at women's health centers, book stores, cafes, Pride festivals, lesbian health centers and clinics, and community events Mean age: 56; range 38–74 Race/ethnicityb: White: 60.3% Latina: 2.9% Black/African American: 1.5% Heterosexual female breast cancer survivors (N = 143) recruited online through breast cancer survivor groups, websites, discussion boards, and organizations; as well as using hard-copy materials distributed via women's health centers, book stores, and cafes Mean age: 54; range 30–79 Race/ethnicityb: White: 60.1% Latina: 2.8% American Indian/Alaska Native: 2.8% Asian American/Pacific Islander: 1.4% |

Compared samples on perceived stress using the PSS-4 Conducted unadjusted linear regression between sexual orientation and perceived stress Conducted linear regression between sexual orientation and perceived stress controlling for age (dichotomized into <55 and ≥55 years of age) |

There was a statistically significant association between sexual orientation and perceived stress for both the unadjusted model and the model adjusted for age. SMW breast cancer survivors reported more perceived stress (M = 8.5, SD = 1.3) than did heterosexual breast cancer survivors (M = 8.1, SD = 1.5) | Six of six criteria met |

| Jabson et al., 201150 | Cross-sectional study examining the association between QOL and sexual orientation among lesbian and heterosexual breast cancer survivors | Lesbian breast cancer survivors (N = 61) recruited online through breast cancer survivor groups, websites, and discussion boards, social networking sites, regional news outlets, lesbian-health focused newsletters, organizations, and discussion boards, as well as through hard-copy materials distributed at women's health centers and hospitals, book stores, cafes, community message boards, Pride festivals, and community events Mean age: 55.7; range 38–74 Race/ethnicityb: White: 55.7% Latina: 1.6% Heterosexual female breast cancer survivors (N = 143) recruited online through breast cancer survivor groups, websites, and discussion boards, social networking sites and news outlets, as well as through hard-copy materials distributed at women's health centers and hospitals, book stores, cafes, and community message boards Mean age: 54.1; range 30–79 Race/ethnicityb: White: 60.1% Latina: 2.8% American Indian/Alaska Native: 2.8% Asian American/Pacific Islander: 1.4% |

Compared samples on psychological well-being using Ferrell and Hassey Dow's QOL Cancer Survivors psychological well-being domain subscale Domain scores were compared across groups using t-test |

No statistically significant difference in psychological well-being was found between lesbian (M = 6.3, SD = 0.9) and heterosexual (M = 6.4, SD = 0.1) breast cancer survivors | Five of six criteria met (“No” on “Strategies used to address confounders”) |

| Studies conducted with sexual minority men | |||||

| Allensworth-Davies, 201251 | Cross-sectional dissertation study examining QOL among gay men after treatment for prostate cancer, and comparing QOL between gay prostate cancer survivors and a comparison sample | Gay men older than the age of 50 (N = 111) recruited nationwide via LGBT print publications, community newspapers, and word of mouth Age range: 50–64: 41.4% 65–74: 41.4% ≥75: 17.2% Race/ethnicity White: 89.2% Non-White: 7.2% “Talcott sample” (N = 235) used as comparison group; Boston clinic-based sample of prostate cancer survivors assumed to be predominantly heterosexual Age range: 50–64: 27.0% 65–74: 40.8% ≥75: 32.2% Race/ethnicity: White: 99.1% |

Compared mental QOL of gay sample to comparison sample using the SF-12 MCS Conducted Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance |

No statistically significant difference in MCS scores was found between gay (M = 48.6, SD = 10.1) and comparison (M = 47.3, SD = 5.9) samples | Four of six criteria met (“No” on “Inclusion criteria clearly defined” and “Strategies used to address confounders”) |

| Hart et al., 201452 | Cross-sectional study comparing health-related QOL and sexual behavior between GB prostate cancer survivors and a normative group of prostate cancer survivors | GB men (N = 92) from the United States and Canada recruited using electronic listservs for prostate cancer survivors, flyers in community centers and support groups, and local media advertising Mean age: 57.8 (SE = 1.0) Race/ethnicity: Caucasian: 91.3% African American: 5.4% Asian: 1.1% Other: 2.2% CaPSURE study cohort (N = 730) used as comparison group; national registry of prostate cancer survivors assumed to be predominantly heterosexual Demographic information not available |

Compared GB survivors with published CaPSURE norms on mental QOL using SF-36 MCS Conducted independent samples t-test |

GB prostate cancer survivors had significantly lower MCS scores (M = 43.9, SE = 1.4) compared with the CaPSURE study cohort (M = 51.9, SE = 1.4) | Three of six criteria met (“No” on “Subjects and setting described in detail,” “Confounding factors identified,” and “Strategies used to address confounders”) |

| Kamen et al., 201453 | Cross-sectional study examining prevalence of cancer diagnosis and health risk behavior in a national sample of gay and heterosexual men, including non-survivors, as well as disparities in psychological distress between subsamples of gay and heterosexual cancer survivors | Gay male cancer survivors (N = 53) surveyed in the 2009 BRFSS conducted by the CDC in Arizona, California, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Wisconsin Heterosexual male cancer survivors (N = 1545) surveyed in the 2009 BRFSS conducted in Arizona, California, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Wisconsin Participants were part of a broader study sample, including men who had never been diagnosed with cancer. Demographic information was not provided for the subsample of cancer survivors Cancer types included prostate cancer, colon cancer, bladder cancer, melanoma, and “other cancers” |

Psychological distress was compared between the gay and heterosexual subsamples of cancer survivors using a single-item BRFSS measure asking participants to report the number of days over the past 30 days in which they experienced poor mental health Conducted independent samples t-test for this comparison, accounting for sample weights and yielding weighted mean estimates and standard errors |

Gay male cancer survivors endorsed significantly more days of poor mental health in the past 30 days (weighted M = 5.3, weighted SE = 9.5) than did heterosexual male cancer survivors (weighted M = 2.4, weighted SE = 6.8) | Two of six criteria met (“No” on “Subjects and setting described in detail,” “Confounding factors identified,” and “Strategies used to address confounders”; “Unclear” on “Outcome measures valid and reliable”) |

| Ussher et al., 201654 | Cross-sectional study comparing GB prostate cancer survivors with heterosexual prostate cancer survivors on health-related QOL, psychological distress, and sexual health | GB men (N = 124) recruited using an information sheet distributed via cancer research volunteer databases, physicians' offices, prostate cancer support groups, GB community organizations, GB social media, and electronic listservs serving prostate cancer survivors Mean age: 64.3 (SD = 8.2) Race/ethnicity: Anglo-Celtic 67.7% Other: 32.3% Heterosexual men (N = 225) recruited using an information sheet distributed via cancer research volunteer databases Mean age: 71.5 (SD = 9.0) Race/ethnicity: Anglo-Celtic: 88.0% Other: 11.1% Sample predominantly recruited from Australia, with a minority recruited from the United States and the United Kingdom |

Compared samples using independent-sample t-tests for the following outcomes: Emotional QOL was assessed using the FACT-P Psychological distress was measured by the BSI-18 Cancer-related distress was measured using the MAX-PC |

GB prostate cancer survivors endorsed significantly worse emotional well-being on the FACT-P (M = 17.1, SD = 4.5) compared with heterosexual prostate cancer survivors (M = 18.3, SD = 4.0) GB prostate cancer survivors reported significantly more psychological distress on the BSI-18 (M = 10.7, SD = 12.4) than heterosexual prostate cancer survivors (M = 7.0, SD = 10.4) GB men were also significantly more likely to meet BSI-18 criteria for distress (13.7%) than heterosexual men (7.1%) GB men scored significantly higher on the BSI-18 depression subscale (M = 4.7, SD = 5.4) than heterosexual men (M = 2.7, SD = 4.4) GB men scored significantly higher on the BSI-18 anxiety subscale (M = 2.0, SD = 2.6) compared with heterosexual men (M = 1.25, SD = 2.2) GB men endorsed significantly greater cancer-related distress (M = 13.6, SD = 10.6) compared with the heterosexual sample (M = 8.9, SD = 8.9) |

Five of six criteria met (“No” on “Strategies used to address confounders”) |

| Wassersug et al., 201355 | Cross-sectional study comparing diagnostic and outcome differences between nonheterosexual prostate cancer survivors and heterosexual prostate cancer survivors after cancer treatment | Nonheterosexual men (N = 96) recruited by distributing study information via websites, e-mail lists, and newsletters of prostate cancer information and support organizations in the United States, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand, as well as targeted Facebook advertising Age range: <46 years: 3.0% 46–55 years: 29.0% 55–65 years: 42.0% 66–75 years: 26.0% Country of residence: United States: 83.0% Canada: 9.0% Other: 7.0% Heterosexual men (N = 460) recruited by distributing study information via websites, e-mail lists, and newsletters of prostate cancer information and support organizations in the United States, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand, as well as targeted Facebook advertising Age range: <46 years: 2.0% 46–55 years: 23.0% 55–65 years: 43.0% 66–75 years: 26.0% >76 years: 4.0% Country of residence: United States: 59.0% Australia: 21.0% Other: 20.0% |

Measured self-reported current antidepressant use (yes/no) as a proxy for mental health/depression Conducted a logistic regression analysis comparing use of antidepressants between nonheterosexual and heterosexual men controlling for demographic variables that differed across groups (country of residence and relationship status) |

There was no statistically significant difference found in current antidepressant use between nonheterosexual (15%) and heterosexual (15%) samples when controlling for country of residence and relationship status | Four of six criteria met (“No” on “Inclusion criteria clearly defined” and “Outcome measures valid and reliable”) |

| Studies conducted with mixed-gender samples | |||||

| Kamen et al., 201556 | Cross-sectional study comparing psychological distress between LGBT and heterosexual cancer survivors | LGBT cancer survivors (N = 207) were recruited online and through LIVESTRONG partner organizations for a national dataset collected online by the LIVESTRONG Foundation Mean age: 47.6 (SE = 11.8) Self-reported sex: Male: 41.5% Female: 58.5% Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White: 87.0% Hispanic/Latino: 5.3% Non-Hispanic Black: 2.9% Asian/Pacific Islander: 0.5% Other: 4.3% Sexual orientation/gender identity: Lesbian/gay: 74.4% Bisexual: 24.6% Transgender: 2.9% Heterosexual cancer survivors (N = 621) were recruited online and through LIVESTRONG partner organizations for a national dataset collected online by the LIVESTRONG Foundation. Survivors were culled from a larger dataset (N = 4889) and selected using propensity matching Mean age: 48.5 (SE = 12.5) Self-reported sex: Male: 40.6% Female: 59.4% Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White: 87.4% Hispanic/Latino: 5.8% Non-Hispanic Black: 1.1% Asian/Pacific Islander: 0.5% Other: 4.5% Most frequently reported cancer types included breast cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, and testicular cancer |

LGBT cancer survivors were matched to heterosexual cancer survivors using a propensity-matching approach. Survivors were matched on age, self-reported sex, race, income, education, relationship status, insurance status, state, type of cancer, age at diagnosis, and time since treatment Using 35 LIVESTRONG dichotomous (yes/no) items about “emotional concerns,” conducted principal component analysis to extract the empirically strongest symptom clusters (eigenvalues ≥2), including a “depression related to cancer” cluster “Depression related to cancer” symptom cluster was compared across samples using Poisson regression analysis to compare count of depression symptoms (ranging from 0 to 6) between LGBT and heterosexual groups Poisson regression analyses comparing depression symptoms between LGBT and heterosexual groups were then stratified by self-reported sex |

LGBT identity was significantly associated with greater symptoms of depression, with LGBT cancer survivors reporting more symptoms (M = 2.4, SD = 1.8) than heterosexual survivors (M = 2.0, SD = 1.7) Stratified analyses revealed an interaction between depression symptoms and self-reported sex Among those identifying as male, GBT survivors reported significantly more depressive symptoms (M = 2.2) than heterosexual survivors (M = 1.7) Among those identifying as female, there was no statistically significant difference found between LBT (M = 2.5) and heterosexual (M = 2.4) survivors on count of depressive symptoms |

Four of six criteria met (“No” on “Inclusion criteria clearly defined,”; “Unclear” on “Outcome measures valid and reliable”) |

| Kamen et al., 201657 | Pilot randomized controlled trial of a dyadic exercise intervention for psychological distress, partner support, and exercise adherence among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual cancer survivors Analyses were conducted to examine differences in psychological distress between lesbian/gay survivors and heterosexual survivors at baseline |

Gay and lesbian cancer survivors (N = 10) referred by nurses and oncologists at Wilmot Cancer Center at the University of Rochester, through word of mouth, and by outreach to local groups serving the lesbian and gay communities Mean age: 54.0 (SE = 4.8) Gender: Male: 50.0% Female: 50.0% Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White: 90.0% Hispanic/Latino: 10.0% Heterosexual cancer survivors (N = 12) referred by nurses and oncologists at Wilmot Cancer Center at the University of Rochester Mean age: 58.0 (SE = 2.3) Gender: Male: 25.0% Female: 75.0% Race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White: 100.0% Cancer types included breast, prostate, rectal, testicular, esophageal, ovarian, pancreatic, sinus, stomach, thyroid, and tongue |

Compared samples on depression symptoms at baseline using the CES-D Compared samples on anxiety symptoms at baseline using the Spielberger STAI Form Y-1, State Form For each comparison, conducted independent samples t-test |

Gay and lesbian cancer survivors reported significantly more depression symptoms (M = 12.4, SE = 3.3) than heterosexual cancer survivors (M = 6.3, SE = 0.8) There was no statistically significant difference in anxiety symptoms between gay and lesbian cancer survivors (M = 30.5, SE = 2.7) and heterosexual cancer survivors (M = 25.8, SE = 1.9) |

Four of six criteria met (“No” on “Confounding factors identified” and “Strategies used to address confounders”) |

Conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute Analytical Cross Sectional Studies Critical Appraisal Tool. Ratings for identification and management of confounders, outcome measures, and analytic techniques were assigned at the outcome level rather than the study level. See Table 3 for further details.

These studies had a large proportion of missing data on demographic variables.

BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; BSI-18, Brief Symptom Inventory-18; CaPSURE, Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression; FACT-P, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostate; GB, gay and bisexual; GBT, gay, bisexual, trans; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; LBT, lesbian, bisexual, trans; LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender; M, mean; MAX-PC, Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer; MCS, Mental Component Summary; N, number of participants; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; QOL, quality of life; RH, registry heterosexual; RSMW, registry SMW; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; SMW, sexual minority women; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

The majority of records were excluded because the study samples were not comprised of cancer survivors (n = 54) or they were review articles (n = 19) or qualitative studies (n = 11). One dissertation study58 was excluded because its findings were subsequently published in two peer-reviewed journal articles included in the review.49,50 One additional peer-reviewed article59 was excluded because the participant samples and outcomes of interest duplicated two previously published peer-reviewed research articles included in the review.47,48 In addition, one article60 fit the inclusion criteria but was published without the demographic and results tables described in the text. Relevant demographic and outcome measures were summarized in the tables and, thus, unavailable for extraction. Efforts to obtain the missing tables from the publisher and first author were not successful; consequently, this article was excluded from the current review.

Quality of evidence

Table 3 presents the quality analysis of the 12 studies included in this review by using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies.45 Nine studies clearly defined the inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants,46–50,52–54,57 whereas three did not.51,55,56 Ten studies46–51,54–57 provided adequate demographic information about participants, although some omitted the participants' geographic location47–50,54 and/or the period during which the study was completed.46,49,54 Two studies were rated “No” on the description of study subjects criterion because they either provided demographic information for the sample of SM survivors but not the comparison group52 or provided demographic information for a larger sample that included non-survivors but not for the subset of survivors.53

Table 3.

Critical Appraisal of Included Studies Using the Joanna Briggs Institute Analytical Cross Sectional Studies Critical Appraisal Tool

| Study | Inclusion criteria clearly defined | Subjects and setting described in detail | Confounding factors identified | Strategies used to address confounders | Outcome measures valid and reliable | Appropriate statistical analysis used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies conducted with sexual minority women | ||||||

| Arena et al., 200646 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Boehmer et al., 201247 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Boehmer et al., 201248 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Jabson and Bowen, 201449 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Jabson et al., 201150 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Studies conducted with sexual minority men | ||||||

| Allensworth-Davies, 201251 | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Hart et al., 201452 | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Kamen et al., 201453 | Y | N | N | N | U | Y |

| Ussher et al., 201654 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Wassersug et al., 201355 | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Studies conducted with mixed-gender samples | ||||||

| Kamen et al., 201556 | N | Y | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Kamen et al., 201657 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

Ratings for identification and management of confounders, reliability and validity of outcome measures, and suitability of analytic techniques were assigned at the outcome level rather than the study level, based on the specific comparisons of interest between sexual minority and heterosexual survivors.

N = no; U = unclear; Y = yes.

Nine studies conducted analyses to identify possible confounding factors,46–51,54–56 whereas one study identified confounders in a broader sample but not among the subsamples of heterosexual and SM cancer survivors,53 and two studies did not assess for possible confounders.52,57 Six studies employed strategies to address confounders for the analyses of interest, such as matching participants on demographic variables46,56 or controlling for other variables (e.g., psychosocial and psychosexual factors and clinical characteristics) in regression analyses.46–49,55 Nine of the twelve studies used measures of psychological health that have been previously found to be valid and reliable46–52,54,57; however, two studies used outcome measures with uncertain validity and reliability,53,56 and another study used an outcome measure with poor validity (i.e., self-reported antidepressant use as a measure of mental health).55 All studies utilized appropriate statistical techniques.

Study characteristics

Of the 12 studies included in this review, all but one57 had a cross-sectional design. The latter was a small pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a dyadic exercise intervention for psychological distress. Six studies collected data via online surveys,49,50,52,54–56 three studies used data collected via telephone,47,48,53 one study used data collected in-person,57 one study collected data via mail-in survey,46 and one study used data collected via mail-in survey for the SM group but used data from an existing “clinic-based” sample for the comparison group.51 Of the 12 studies, 6 compared mental health between SM and heterosexual survivors as their primary objective,46–50,56 whereas such comparisons were secondary to broader study aims in the remaining studies.51–55,57

In addition, studies used a number of methods to obtain samples of SM survivors. One study used survey data collected as part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).53 The BRFSS used probability sampling to select participants via random digit dialing. However, the study reviewed only included participants from the five states in the United States that included questions about both sexual orientation and cancer history.53 One group of studies used a multistep approach to draw a population-based sample from a state cancer registry, augmented by a convenience sample drawn nationwide from the Internet and the community.47,48 The other studies used convenience sampling61 of SM individuals recruited from a number of sources, including from the Internet,55 from community locations,51 from a local cancer center and the community,57 a combination of clinics and community sources,46 a combination of the Internet and community sources,49,50,52,56 and a combination of clinics, the Internet, and community sources.54

Participant characteristics

Samples ranged in size from 10 to 207 for SM survivors and from 12 to 1545 for heterosexual survivors, and they were comprised predominantly of White individuals from the United States, with a few studies also including participants from Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.52,54,55 On average, participants were between 47.6 and 64.3 years of age for SM samples and between 48.5 and 71.5 years for comparison samples, although for certain studies some demographic information was not available or had a large proportion of missing data.49,50,52,53 Four studies were comprised exclusively of men with prostate cancer,51,52,54,55 one included men with heterogeneous cancers,53 five enrolled women with breast cancer,46–50 and two were comprised of men and women with heterogeneous cancers.56,57 Stage of enrolled participants on the cancer care continuum also varied, as five studies included participants exclusively in the post-treatment survivorship stage,47,48,51,52,57 three included participants who were in either active treatment or post-treatment survivorship,46,54,56 three included participants at any stage after diagnosis, including pre-treatment,49,53,55 and one study did not specify stages of participants on the cancer care continuum.50

Of the SM samples, two were comprised exclusively of gay men,51,53 two enrolled gay and bisexual men,52,54 and one included gay men, bisexual men, and MSM.55 Two studies were comprised exclusively of lesbian women46,50 and three were comprised of lesbian women, bisexual women, and women with a sexual preference for women.47–49 A minority of studies reflected a mixed-gender sample: One enrolled a sample of lesbian women and gay men57 and another included lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender individuals.56 Of the eight studies that had samples comprised of diverse sexual orientations,47–49,52,54–57 only two provided information about the proportions of different participant sexual identities or behaviors (e.g., gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, or MSM)56,57; thus, it is unclear how many individuals belonging to each group were included in each study. Seven of the twelve studies described the criteria by which individuals were classified as a SM48–51,53,55,56; the rest of the studies did not specify how SM status was assessed or how participants were categorized into each group.46,47,52,54,57

Mental health outcomes

Psychological distress

Although a number of studies' stated purpose was to measure psychological or emotional distress,53,54,56,57 most of these studies ultimately used measures of more specific psychological conditions, such as depression and anxiety, and are discussed in the next sections. Two studies used designated measures of psychological distress, finding that both gay men with heterogeneous cancers53 and gay and bisexual men with prostate cancer54 endorsed greater levels of distress than heterosexual survivors.

Depression

Six studies evaluated differences in depression symptoms and/or antidepressant use between SM and heterosexual samples.46,47,54–57 Two studies conducted with women with breast cancer found no significant difference in depression symptoms between heterosexual and SM groups.46,47 However, one of these studies found that lesbian breast cancer survivors were more likely to endorse self-reported antidepressant use compared with heterosexual survivors.47 Among studies conducted with men, one found that gay and bisexual men with prostate cancer had significantly greater depression symptoms than their heterosexual peers,54 although another study found no difference in self-reported antidepressant use between non-heterosexual and heterosexual prostate cancer survivors.55 Two studies were conducted with survivors of heterogeneous cancers, including gay and lesbian individuals57 and LGBT individuals.56 The former study found a mixed-gender sample of gay and lesbian cancer survivors enrolled in a small pilot RCT to have significantly greater depression symptoms than their heterosexual peers at baseline.57 The study of LGBT cancer survivors found in stratified analyses that self-reported male, but not female, LGBT cancer survivors had significantly greater depression related to cancer compared with their heterosexual counterparts.56

Anxiety

Three studies compared self-reported anxiety symptoms between SM and heterosexual cancer survivors.47,54,57 One study conducted among women47 found that SM and heterosexual breast cancer survivors recruited from the same cancer registry did not differ in anxiety symptoms when compared directly or in multiple regression analyses, but that SM women recruited from the registry, combined with a convenience sample, reported less anxiety than registry-based heterosexual women when controlling for seven demographic and clinical variables and two interactions. In addition, this study found no difference in self-reported use of anti-anxiety drugs between SM and heterosexual breast cancer survivors. Among men, one study found that gay and bisexual men with prostate cancer reported greater anxiety symptoms compared with heterosexual men with prostate cancer.54 One pilot RCT found no difference in anxiety symptoms between a combined sample of gay and lesbian survivors and their heterosexual peers at baseline.57

Stress

One study assessed differences in perceived stress among SM breast cancer survivors compared with heterosexual breast cancer survivors.49 This study found that SM women reported significantly more perceived stress than heterosexual women.

Mental and emotional QOL

Five studies evaluated differences in mental and emotional well-being between heterosexual and SM cancer survivors by using subscales of QOL measures.48,50–52,54 Among women, neither of the two studies comparing SM48 and lesbian50 breast cancer survivors with heterosexual breast cancer survivors found significant differences in emotional or mental well-being between groups. Among men, the findings were mixed: Two studies of prostate cancer survivors found a significant difference in emotional and mental QOL scores, between gay and bisexual survivors compared with heterosexual survivors,54 and between gay and bisexual survivors compared with a normative cohort assumed to be predominantly heterosexual,52 such that gay and bisexual prostate cancer survivors reported lower mental and emotional QOL compared with heterosexual men. In contrast, one dissertation study found no difference within this domain between gay prostate cancer survivors and a clinic-based sample of prostate cancer survivors assumed to be predominantly heterosexual.51

Discussion

This study is the first known systematic review conducted to examine mental health disparities among SM cancer survivors. In a qualitative synthesis of 12 articles, the review identified significant heterogeneity in study methodology and outcomes pertaining to psychological health among SM and heterosexual cancer survivors. Of note, although most studies reporting on mental health among women found no differences in psychological outcomes between SM and heterosexual survivors, SM men reported worse mental health outcomes than heterosexual men on numerous outcomes, including psychological distress,53,54 depression symptoms,54 anxiety,54 and mental or emotional QOL.52,54 This observed pattern of results was further supported by the findings of one study of LGBT individuals with heterogeneous cancers,56 which indicated that, among self-identified males, GBT survivors endorsed a greater number of depression symptoms compared with heterosexual survivors, but found no difference in depression symptoms between self-identified female heterosexual and LBT survivors. Given the small number of studies available to date exploring mental health specifically among SM cancer survivors relative to heterosexual survivors, conclusions must be made with caution; however, the findings of the present synthesis suggest that SM men diagnosed with cancer may be at risk for worse mental health compared with heterosexual survivors.

The extent to which the divergent mental health outcomes observed among SM men and women are affected by gender, cancer type, cancer treatment, or a combination of these factors remains to be determined. Although male and female SM individuals share many experiences and clinical concerns, different identities also constitute distinct populations with unique needs and concerns.1 As noted previously, most of the studies conducted among SM women focused on experiences with breast cancer, whereas most of the studies conducted among SM men focused on prostate cancer. Experiences with different cancers and different types of treatment across genders may influence patients' mental health differentially. For example, men treated for prostate cancer commonly experience adverse sexual side effects,62 and multiple studies have found that SM prostate cancer survivors experience more distress related to certain sexual changes, such as ejaculatory difficulties, compared with heterosexual prostate cancer survivors.52,54,55 Greater concern about such side effects may contribute to the higher rates of psychological concerns observed among SM men relative to heterosexual men.

Further, there is evidence that men are less likely than women to seek mental health care.63 Consequently, it is possible that SM women in the included studies were more likely to seek mental health services than SM men when experiencing mental health concerns, thus experiencing and endorsing fewer psychiatric symptoms. This theory is supported by the pattern of findings observed in the review, wherein SM women endorsed greater use of antidepressants than heterosexual women47 but did not report greater depressive symptoms.46,47

In addition, it is possible that differences in social support may inform mental health disparities among SM men relative to SM women. This review found that SM women reported greater stress than heterosexual women49 but did not endorse greater psychopathology or worse psychological well-being.46–48,50,56 Studies have found that social isolation can contribute to coping difficulties and associated psychopathology, particularly in the context of chronic stress, whereas social support and affiliation with a community can buffer against the harmful effects of stress.12,16 Gay and bisexual men with prostate cancer frequently report feelings of isolation from the gay community, often as a result of morphological or sexual changes experienced due to prostate cancer treatment.64,65 In contrast, there is evidence that SM women actively utilize social support after breast cancer diagnosis46,60,66 and that this support protects against psychological distress.67

Thus, SM men may be more vulnerable to experiencing difficulty coping with prostate cancer and related psychopathology as a result of insufficient social support, whereas SM women may be more likely to obtain support that is protective against mental health concerns. Consistent with this hypothesis, a study of LGBT cancer survivors found that bisexual and lesbian women report having more social support available from romantic partners and friends compared with gay and bisexual men.66 More research is required to further assess the protective role of social support among SM cancer survivors.

The current review highlights numerous additional avenues for further study. More research is needed to identify potential mental health disparities among SM survivors diagnosed with cancers beyond prostate and breast cancer, as well as predisposing and protective factors influencing mental health disparities among SM cancer survivors. To date, SM populations have been largely underserved, and their needs neglected by research and health care institutions. The 12 studies included in the current review are among the first studies designed to assess the mental health of SM individuals with cancer and identify health inequalities among SM survivors relative to heterosexual populations. However, as early studies conducted predominantly with small convenience samples, they are not without their limitations. Many of the studies sampled participants from multiple populations (e.g., different organizations or geographic locations); however, only six utilized study designs that addressed the influence of possible confounders.46–49,55,56 Future research should match samples based on demographic and treatment characteristics,46,56 or alternatively assess for confounding variables and utilize appropriate statistical techniques to account for these factors.

In addition, 6 of the 12 studies49,50,52,54–56 were conducted by using Internet surveys. Although online surveys greatly increase the reach, scope, and ease of research conducted with SM individuals, such surveys may also be subject to fraudulent responding, such as participants submitting multiple survey responses and/or providing inconsistent or inaccurate responses,68 which can reduce the validity of study findings. Studies that rely on online surveys should consider the risks of Internet survey fraud and take steps to prevent and detect fraudulent responding (see ref.68).

Further, there was significant heterogeneity in the measures used to assess mental health outcomes, with some of these measures having unknown validity and reliability, particularly in cancer populations. Within the studies included in this review, anxiety was assessed with five different instruments, depression with six different assessments, and QOL with four. This heterogeneity of measurements precludes a comparison of mental health outcomes across studies and samples. Future work should standardize the conceptualization and measurement of mental health concerns among SM cancer survivors and utilize reliable and valid instruments for assessing mental health.

There was also significant variability in the way in which researchers defined and assessed SM status, if they did so at all. Only seven studies48–51,53,55,56 noted how they defined and assessed sexual identity and/or behavior of participants, and several studies combined individuals with different sexual orientations into one group without indicating the number of individuals belonging to each group (e.g., number of individuals who were gay vs. bisexual vs. MSM). This is of concern given that different SM populations may have unique characteristics and vulnerabilities that predispose them to different challenges and needs in cancer survivorship care.39 Future work should standardize methods for defining, assessing, and reporting SM group membership.

Limitations

The current review has some limitations. With the exception of theses and dissertations, only peer-reviewed studies were included in the review; therefore, the review may have overlooked abstracts or unpublished studies examining mental health differences in SM and heterosexual cancer survivors. In addition, the review was limited to mental health outcomes and did not include commonly associated health behaviors, such as substance use. Overall, the small number of studies included in the review, combined with relatively small sample sizes per study, reliance on convenience sampling, and heterogeneity of outcome measures may limit the generalizability of the findings.

In addition, because the current review was designed to compare mental health outcomes between SM and heterosexual cancer survivors, it was limited to studies that had a heterosexual comparison group and, thus, focused solely on mental health outcomes that were relevant to both SM and heterosexual groups. Consequently, the review did not address issues specific to SM individuals that may contribute to distress and poor QOL in the context of cancer, such as experiences of stigma and discrimination, minority stress, difficulties accessing care, disclosure concerns, and low satisfaction with provider relationships.12,29,30 Recent studies have begun to examine how these concerns influence mental health among SM cancer survivors,69,70 and future research should continue to assess how these unique factors shape the mental health and health care needs of SM cancer survivors.

Further, this review focused specifically on SM populations while neglecting gender identity. Although one study included transgender individuals,56 most studies did not indicate whether any of the participants were transgender, in addition to being a SM. Research must be conducted to understand the needs of transgender individuals diagnosed with cancer, a profoundly understudied and underserved group to date.

Lastly, all but one of the studies included in the current review were cross-sectional in nature, and none of the studies assessed psychological symptoms over time or accounted for mental health concerns that participants may have experienced before their cancer diagnosis. Given that SM individuals in the general population have been found to experience higher rates of mental health disorders and distress than heterosexual individuals,7–9 the extent to which the mental health disparities identified in the included studies reflect baseline differences in mental health between heterosexual and SM individuals, as compared with distress related to cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship, is unclear. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine trajectories of psychological health before diagnosis and across the cancer care continuum in SGM individuals.

Implications

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the findings of this review have important implications for the provision of cancer care among SM individuals. This study suggests that significant mental health disparities may exist among SM men with cancer, particularly prostate cancer. Screening and interventions to identify and address mental health concerns among this group are warranted. Prior research indicates that many men treated for prostate cancer experience difficulties with sexual health and functioning, side effects that have been found to negatively disrupt self-identity and interpersonal relationships among gay, bisexual, and MSM.64,71 In addition, a recent qualitative study found that salient concerns for gay men with prostate cancer include minority stress, intimacy and sexuality concerns, and lack of social support.65 Therefore, psychosocial interventions that assist patients in increasing stress management skills (e.g., cognitive–behavioral stress management interventions72,73), navigating challenges in adjusting to sexual changes and associated intimacy and relationship concerns,74 and increasing social connection (e.g., peer support interventions75) may be of particular benefit to this population.

Further, this systematic review highlights the need for health care centers and providers to continue working to meet ASCO's 2017 recommendations on reducing SGM health care disparities in cancer care,39 including expanding and promoting SGM cultural competency training for health care providers and staff as well as health system assessment of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data for clinical care and research purposes. Collection of SOGI data by health care organizations would allow for higher quality research and the ability to conduct multi-site, multi-cancer, longitudinal studies on the experiences and outcomes of SGM cancer survivors. In addition, the availability of SOGI data in medical records, cancer registries, and nationally representative datasets would facilitate the use of probability sampling to recruit samples that are more representative of SGM cancer survivors at large. To date, most studies comparing outcomes between SM and heterosexual cancer survivors have relied on convenience samples of SM individuals, which carry the risk of selection bias and reduce the ability of researchers to generalize research findings outside of the study sample.61

Moreover, collecting SOGI data would enable health care institutions and providers to better identify and care for patients with LGBT-specific needs and concerns. A recent survey of oncologists found that only 26% of providers sampled inquire about sexual orientation when taking a patient's history.76 Unfortunately, few health care providers are trained to provide care for SGM patients, and many lack knowledge about the health risks and needs of SGM patients.29,77,78 Consequently, comprehensive SGM cultural competency training for health care providers and staff is essential.

There are a number of resources available online for medical providers looking to improve their knowledge of and sensitivity to SGM issues. These include The National LGBT Health Education Center at the Fenway Institute79 and the National LGBT Cancer Network80 in the United States, and resources and training at Rainbow Health Ontario in Canada.81 In the United Kingdom, resources available online for clinicians include the Stonewall Guide to Sexual Orientation for National Health Service (NHS) workers82 and Macmillan Cancer Support resources.83–85 The Fenway Institute has also created an online toolkit to assist health care providers and health care systems in collecting SOGI information in clinical settings,86 and the NHS has recently provided guidelines for collecting and monitoring sexual orientation data across NHS health service sites in England.87 Lastly, recent case studies provide information about the development and implementation of policies and training programs to enhance ethical care of LGBT individuals within large health care systems in the United States.88–90 In the United Kingdom, initiatives are underway to improve care for LGBT individuals within the NHS91 and further advance the health of LGBT individuals living in the United Kingdom.92

Conclusion

SM cancer survivors are an understudied population. This systematic review contributes to the literature by synthesizing research on mental health disparities among SM cancer survivors. The findings indicate that SM men, particularly those with prostate cancer, may experience worse mental health outcomes during cancer survivorship relative to heterosexual men. It is essential that further work be conducted to better understand and appropriately address this disparity, as poor mental health may have a negative impact on survivors' involvement in health care, response to treatment, and long-term survival,34,35 and contribute to greater health care costs and expenditures.36,37

Acknowledgments

S.H.B. is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute training grant T32CA193193. The authors would like to thank Ms. Katie Houk, health sciences librarian, for her assistance in developing the systematic search strategy, as well as Mr. Nicholas Lucido for his assistance in proofreading and verifying the accuracy of Table 2.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Mayer KH, Bradford JB, Makadon HJ, et al. : Sexual and gender minority health: What we know and what needs to be done. Am J Public Health 2008;98:989–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ward BW, Dahlhamer JM, Galinsky AM, Joestl SS: Sexual orientation and health among U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2013. Natl Health Stat Report 2014:1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Statistics Canada: Same-sex couples and sexual orientation… by the numbers. 2015. Available at http://statcan.gc.ca/eng/dai/smr08/2015/smr08_203_2015 Accessed December10, 2018

- 4. Wilson T, Shalley F: Estimates of Australia's non-heterosexual population. Aust Popul Stud 2018;2:26–38 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Office for National Statistics: Sexual identity UK: 2016. 2017. Available at http://ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/sexuality/bulletins/sexualidentityuk/2016 Accessed December10, 2018

- 6. Gates GJ: How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? The Williams Institute. 2011. Available at http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf Accessed September24, 2018

- 7. Blondeel K, Say L, Chou D, et al. : Evidence and knowledge gaps on the disease burden in sexual and gender minorities: A review of systematic reviews. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, et al. : A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cochran SD, Mays VM, Sullivan JG: Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71:53–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, et al. : Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2014;84:35–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS: State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am J Public Health 2009;99:2275–2281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meyer IH: Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feinstein BA, Goldfried MR, Davila J: The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:917–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuyper L, Fokkema T: Minority stress and mental health among Dutch LGBs: Examination of differences between sex and sexual orientation. J Couns Psychol 2011;58:222–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lehavot K, Simoni JM: The impact of minority stress on mental health and substance use among sexual minority women. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79:159–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J: How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychol Sci 2009;20:1282–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mereish EH, Poteat VP: A relational model of sexual minority mental and physical health: The negative effects of shame on relationships, loneliness, and health. J Couns Psychol 2015;62:425–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosario M, Corliss HL, Everett BG, et al. : Sexual orientation disparities in cancer-related risk behaviors of tobacco, alcohol, sexual behaviors, and diet and physical activity: Pooled youth risk behavior surveys. Am J Public Health 2014;104:245–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blosnich JR, Farmer GW, Lee JG, et al. : Health inequalities among sexual minority adults: Evidence from ten U.S. states, 2010. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:337–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, et al. : Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. Am J Public Health 2013;103:1802–1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosario M, Li F, Wypij D, et al. : Disparities by sexual orientation in frequent engagement in cancer-related risk behaviors: A 12-year follow-up. Am J Public Health 2016;106:698–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agénor M, Krieger N, Austin SB, et al. : Sexual orientation disparities in Papanicolaou test use among US women: The role of sexual and reproductive health services. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e68–e73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mansh M, Katz KA, Linos E, et al. : Association of skin cancer and indoor tanning in sexual minority men and women. JAMA Dermatol 2015;151:1308–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boehmer U, Ozonoff A, Miao X: An ecological analysis of colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: Differences by sexual orientation. BMC Cancer 2011;11:400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Denlinger CS, Carlson RW, Are M, et al. : Survivorship: Introduction and definition. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2014;12:34–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Cancer Institute: NCI dictionary of cancer terms: Survivor. n.d. Available at http://cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/survivor Accessed December10, 2018

- 27. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Distress management. 2016. Available at http://nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/distress.pdf Accessed September24, 2018

- 28. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, et al. : The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology 2001;10:19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities: The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jabson JM, Kamen CS: Sexual minority cancer survivors' satisfaction with care. J Psychosoc Oncol 2016;34:28–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rose D, Ussher JM, Perz J: Let's talk about gay sex: Gay and bisexual men's sexual communication with healthcare professionals after prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017;26:e12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Kegler C, et al. : The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement of black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e75–e82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Durso LE, Meyer IH: Patterns and predictors of disclosure of sexual orientation to healthcare providers among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Sex Res Social Policy 2013;10:35–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ: Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Cancer 2009;115:5349–5361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Greer JA, Pirl WF, Park ER, et al. : Behavioral and psychological predictors of chemotherapy adherence in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Psychosom Res 2008;65:549–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mausbach BT, Yeung P, Bos T, Irwin SA: Health care costs of depression in patients diagnosed with cancer. Psychooncology 2018;27:1735–1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pan X, Sambamoorthi U: Health care expenditures associated with depression in adults with cancer. J Community Support Oncol 2015;13:240–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. : Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:384–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Griggs J, Maingi S, Blinder V, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement: Strategies for reducing cancer health disparities among sexual and gender minority populations. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2203–2208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Drescher J: Out of DSM: Depathologizing homosexuality. Behav Sci (Basel) 2015;5:565–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. EndNote X7.3.1. Philadelphia, PA: Thomson Reuters, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 42. National Cancer Institute: NCI dictionary of cancer terms: Stress. n.d. Available at http://cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/stress Accessed March11, 2018

- 43. National Cancer Institute: NCI dictionary of cancer terms: Quality of life. n.d. Available at http://cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/quality-of-life Accessed March11, 2018

- 44. Healthy People 2020: Foundation health measure report: Health-related quality of life and well-being. 2010. Available at http://healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/HRQoLWBFullReport.pdf Accessed March11, 2019

- 45. The Joanna Briggs Institute: The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews: Checklist for analytical cross sectional studies. 2017. Available at http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/critical-appraisal-tools/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Analytical_Cross_Sectional_Studies2017.pdf Accessed March6, 2018

- 46. Arena PL, Carver CS, Antoni MH, et al. : Psychosocial responses to treatment for breast cancer among lesbian and heterosexual women. Women Health 2006;44:81–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M: Anxiety and depression in breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:382–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boehmer U, Glickman M, Milton J, Winter M: Health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. Qual Life Res 2012;21:225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jabson JM, Bowen DJ: Perceived stress and sexual orientation among breast cancer survivors. J Homosex 2014;61:889–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jabson JM, Donatelle RJ, Bowen DJ: Relationship between sexual orientation and quality of life in female breast cancer survivors. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:1819–1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Allensworth-Davies D: Assessing localized prostate cancer post-treatment quality of life outcomes among gay men. Dissertation. Boston University, 2012. Available at http://open.bu.edu/handle/2144/12263 Accessed February22, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hart TL, Coon DW, Kowalkowski MA, et al. : Changes in sexual roles and quality of life for gay men after prostate cancer: Challenges for sexual health providers. J Sex Med 2014;11:2308–2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kamen C, Palesh O, Gerry AA, et al. : Disparities in health risk behavior and psychological distress among gay versus heterosexual male cancer survivors. LGBT Health 2014;1:86–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ussher JM, Perz J, Kellett A, et al. : Health-related quality of life, psychological distress, and sexual changes following prostate cancer: A comparison of gay and bisexual men with heterosexual men. J Sex Med 2016;13:425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]