Abstract

Purpose: We examined differences in lifetime human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing in relation to both sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity among U.S. women and men.

Methods: We used 2013–2017 National Health Interview Survey data and multivariable logistic regression to assess the distribution of lifetime HIV testing across and within sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic groups of U.S. women (n = 60,867) and men (n = 52,201) aged 18–64 years.

Results: Among women, Black lesbian (74.1%) and bisexual (74.0%) women had the highest prevalence whereas Asian lesbian women (32.5%) had the lowest prevalence of lifetime HIV testing. Among men, the prevalence of lifetime HIV testing was the highest among Latino gay men (92.6%) and the lowest among Asian heterosexual men (32.0%). In most cases, Black women and Black and Latino men had significantly higher adjusted odds whereas Asian women and men had lower adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing compared with their White counterparts within sexual orientation identity groups. In many instances, bisexual women and gay men had significantly higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing relative to their heterosexual counterparts within racial/ethnic groups. Compared with White heterosexual individuals, most sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups had significantly higher adjusted odds whereas Asian heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women and Asian heterosexual and bisexual men may have lower adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing.

Conclusion: Culturally relevant, linguistically appropriate, and structurally competent programs and practices are needed to facilitate lifetime HIV testing among diverse sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups of women and men, including multiply marginalized subgroups that are undertested or disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS.

Keywords: HIV testing, intersectionality, men, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, women

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) remains a significant public health problem in the United States. In 2016, 32,131 U.S. men and 7529 U.S. women aged 13 years and older were newly diagnosed with HIV.1 In 2017, gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with men (MSM) accounted for the majority of new HIV diagnoses among U.S. individuals in general (66%) and U.S. men in particular (82%).2 Although, to our knowledge, no data exist on new HIV diagnoses among women in relation to sexual orientation, studies suggest that some subgroups of sexual minority women (SMW)—namely, bisexual women and women with both male and female sexual partners—may have higher levels of HIV risk factors, including sexually transmitted infections, total number of sexual partners, and sexual victimization, compared with non-SMW.3–5 Moreover, in 2010, Black men accounted for most (39%) new HIV infections among U.S. men6 and, in 2017, Black women accounted for the majority (59%) of new HIV diagnoses among U.S. women.7 At the intersection of sexual orientation and race/ethnicity, Black and Latino MSM had the highest number of new HIV diagnoses among U.S. MSM in 2016.1 Surveillance data are not collected in relation to both social categories among U.S. women; however, researchers have identified elevated levels of HIV risk factors, including incarceration, intimate partner violence, and transactional sex, among Black and Latina SMW.8,9

HIV testing is critical to informing individuals of their HIV status and preventing HIV/AIDS morbidity and mortality10 and HIV transmission.11 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend HIV testing at least once in a lifetime for individuals aged 13–64 years10 and at least annually for people at high risk of HIV infection, including MSM.12 Research has shown that gay or lesbian and bisexual U.S. men and women were significantly more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to have received an HIV test in their lifetime.13,14 Moreover, studies also indicate that Black and Latinx U.S. adults have a significantly higher prevalence of lifetime HIV testing relative to their White and Asian counterparts.15,16 At the intersection of sexual orientation and race/ethnicity, researchers have found that White, Latino, and Black gay and bisexual men were significantly more likely to have ever received an HIV test compared with their heterosexual counterparts and White heterosexual men.17 Moreover, they also found that Black SMW were significantly more likely to have obtained an HIV test in their lifetime relative to White heterosexual women.17 In a similar analysis that included Asian individuals, White, Black, Latinx, and Asian sexual minority adults had significantly higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing compared with their nonsexual minority counterparts.16,17

Although several studies have examined HIV testing in relation to both sexual orientation and race/ethnicity among U.S. men17–20 and one has specifically investigated this issue among U.S. women,17 prior research has been limited to subnational geographic areas,21,22 restricted to convenience samples,23,24 included only White, Black, and (less frequently) Latinx individuals,17–20 combined gay or lesbian and bisexual people into a single sexual orientation group,17,23,25 and/or aggregated women and men into one category.16,17 Thus, using a national probability sample of U.S. women and men, we designed a quantitative study to assess the distribution of lifetime HIV testing in relation to both sexual orientation identity, with gay or lesbian and bisexual individuals categorized separately, and race/ethnicity, including among White, Black, Latinx, and Asian individuals.

This study was guided by intersectionality, an analytic framework with roots in Black feminism26–29 that focuses on how the lived experiences of multiply marginalized groups are shaped by the mutually influencing effects of multiple social categories at the individual level (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation) and related forms of discrimination at the interpersonal and structural levels (e.g., sexism, racism, heterosexism).30–32 In line with intersectionality, we conceptualized sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity as individual-level social categories linked to not only individuals' social identity but also their position in the social hierarchy.30–32 Methodologically, we assessed the simultaneous effect of sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity on lifetime HIV testing among U.S. women and men in multiple ways. Specifically, we examined differences in lifetime HIV testing in relation to race/ethnicity among sexual orientation identity groups and in relation to sexual orientation identity among racial/ethnic groups. We also ascertained the distribution of lifetime HIV testing among sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups by using an interaction model.33–35

This study contributes to the scientific literature by identifying previously unanalyzed differences in lifetime HIV testing in relation to both sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity among U.S. women and men using an intersectional lens. Our findings will also help assess progress toward meeting the Healthy People 2020 lifetime HIV testing objective (i.e., 73.6% prevalence)36 among diverse sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups of women and men, including those who face the greatest HIV/AIDS burden as a result of heterosexism and racism. Further, our study results will help identify multiply marginalized subgroups with especially low levels of lifetime HIV testing. Thus, this study may help inform the development of tailored interventions that facilitate lifetime HIV testing among multiply marginalized sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups that are undertested and, along with HIV prevention and treatment promotion efforts, help reduce the burden of HIV/AIDS among those who are the most at risk of developing the disease.

Methods

Study participants

We analyzed 2013–2017 data from the annual National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which uses a stratified, multistage sampling design to generate a national probability sample of the civilian, non-institutionalized U.S. population.37 Our analyses were restricted to adults aged 18–64 years as only participants aged 18 years and older were asked about lifetime HIV testing, and lifetime HIV testing is recommended for individuals aged 13–64 years.10 Individuals who responded “something else” (n = 425; 0.36%) or “I don't know” (n = 713; 0.57%) or did not respond to the sexual orientation identity question (n = 3514; 3.0%) were excluded from our sample. Further, we also excluded Native American (namely, Indian American and Alaska Native individuals; n = 1036; 0.67%) and multiracial (n = 2272; 1.63%) individuals and those from other racial/ethnic backgrounds (n = 293; 0.16%) due to their small numbers in this study, which prevented reliable subgroup analyses. Individuals who did not provide data on lifetime HIV testing (n = 5634; 4.84%) were also excluded. Thus, our final analytic sample included 113,068 White, Black, Latinx, and Asian U.S. women (n = 60,867) and men (n = 52,201) who self-identified as heterosexual, bisexual, or gay or lesbian with no missing data on lifetime HIV testing.

Measures

Sexual orientation identity was assessed by asking participants, “Which of the following best represents how you think of yourself?” Study participants were categorized as follows in terms of sexual orientation identity: “gay/lesbian,” “straight, that is, not gay” (henceforth, heterosexual), and “bisexual.” Participants self-reported both Hispanic ethnicity and race and were then categorized based on their race/ethnicity as Hispanic (namely, Puerto Rican, Cuban/Cuban American, Dominican, Mexican, Mexican American, Central or South American, “other” Latin American, and “other” Hispanic/Latino/Spanish individuals; henceforth, Latinx), non-Hispanic White (henceforth, White), non-Hispanic Black/African American (henceforth, Black), and non-Hispanic Asian (namely, Indian, Chinese, Filipino/a, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and “other” Asian individuals; henceforth, Asian). Sex was ascertained through a self-reported measure with two response categories: male or female. The outcome of interest, lifetime HIV testing (yes/no), was assessed by using the following item: “Except for tests you may have had as part of blood donations, have you ever been tested for HIV?” Covariates (shown in Table 1 with their categorization) included demographic (i.e., age, nativity, geographic region, and relationship status), socioeconomic (i.e., educational attainment and employment status), and health care (i.e., health insurance status, usual place of care, and number of health care visits in the past year) factors. The proportion of missing data for covariates was small and ranged from 0.03% (n = 36) for nativity to 0.18% (n = 190) for relationship status. NHIS staff imputed race/ethnicity for those missing data on this variable by using hot-deck imputation.38

Table 1.

Age-Standardized Percentage Distribution of Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Health Care Factors in Relation to Sexual Orientation Identity and Race/Ethnicity Among U.S. Women Aged 18–64 Years (N = 60,867)

| Variable (%) | Total | White heterosexual (n = 35,966) | Black heterosexual (n = 8844) | Latina heterosexual (n = 10,705) | Asian heterosexual (n = 3424) | White bisexual (n = 638) | Black bisexual (n = 123) | Latina bisexual (n = 126) | Asian bisexual (n = 21) | White lesbian (n = 662) | Black lesbian (n = 169) | Latina lesbian (n = 158) | Asian lesbian (n = 31) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||

| 18–29 | 24.0 | 21.7 | 25.5 | 28.0 | 26.8 | 49.4 | 61.7 | 63.9 | 66.4 | 21.4 | 38.7 | 37.8 | 21.5 |

| 30–39 | 22.0 | 19.7 | 23.0 | 28.7 | 26.8 | 26.0 | 18.6 | 22.6 | 3.1 | 20.3 | 29.1 | 18.8 | 40.1 |

| 40–49 | 19.9 | 19.7 | 19.9 | 20.9 | 22.4 | 11.3 | 10.3 | 11.0 | 25.4 | 20.3 | 17.6 | 19.3 | 18.3 |

| 50–64 | 34.1 | 38.9 | 31.6 | 22.3 | 24.0 | 13.3 | 9.4 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 38.0 | 14.6 | 24.1 | 20.1 |

| U.S.-born: yes | 82.8 | 94.8 | 89.2 | 44.8 | 22.1 | 96.5 | 97.8 | 57.8 | 41.9 | 97.1 | 96.5 | 60.8 | 37.0 |

| Geographic region | |||||||||||||

| Northeast | 17.0 | 17.7 | 15.0 | 15.3 | 19.5 | 16.6 | 9.0 | 12.7 | 21.8 | 18.0 | 10.7 | 17.6 | 32.0 |

| Midwest | 22.9 | 28.4 | 16.7 | 9.2 | 13.3 | 24.3 | 27.2 | 8.1 | 25.2 | 23.5 | 24.5 | 8.6 | 11.0 |

| South | 38.3 | 34.2 | 61.5 | 38.4 | 24.9 | 31.9 | 57.5 | 30.5 | 9.8 | 34.2 | 54.7 | 30.6 | 20.5 |

| West | 21.8 | 19.7 | 6.9 | 37.1 | 42.3 | 27.2 | 6.3 | 48.7 | 43.2 | 24.3 | 10.1 | 43.2 | 36.5 |

| Relationship status | |||||||||||||

| Never married | 28.2 | 23.8 | 48.2 | 25.5 | 24.9 | 33.1 | 62.2 | 36.1 | 48.8 | 42.4 | 70.1 | 42.2 | 42.0 |

| Married | 44.1 | 48.9 | 21.3 | 44.7 | 58.3 | 22.9 | 4.6 | 33.0 | 28.8 | 23.1 | 9.6 | 18.0 | 18.2 |

| Living with a partner | 7.5 | 7.8 | 5.0 | 8.1 | 3.7 | 14.3 | 6.8 | 12.5 | 7.4 | 25.8 | 8.4 | 25.6 | 26.2 |

| Divorced, widowed, or separated | 20.1 | 19.4 | 25.5 | 21.6 | 13.0 | 29.6 | 26.4 | 18.4 | 15.0 | 8.7 | 11.9 | 14.3 | 13.6 |

| Educational attainment | |||||||||||||

| Less than high school degree | 10.1 | 5.5 | 13.2 | 29.0 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 16.6 | 38.7 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 15.8 | 17.6 | 9.1 |

| High school diploma or GED | 21.1 | 19.8 | 25.4 | 24.5 | 14.8 | 16.2 | 33.1 | 19.5 | 3.8 | 14.3 | 24.8 | 18.9 | 6.2 |

| Some college or associate's degree | 33.9 | 34.9 | 37.7 | 29.5 | 22.1 | 38.7 | 35.7 | 26.4 | 16.9 | 33.1 | 39.4 | 34.2 | 38.0 |

| Bachelor's degree or more | 34.8 | 39.9 | 23.6 | 16.9 | 56.5 | 38.5 | 14.6 | 15.4 | 75.5 | 47.6 | 20.1 | 29.3 | 46.7 |

| Working for pay: yes | 67.4 | 70.1 | 64.6 | 60.7 | 62.9 | 71.4 | 56.1 | 64.7 | 74.3 | 75.1 | 62.3 | 70.9 | 62.9 |

| Uninsured: yes | 12.5 | 9.0 | 13.9 | 26.0 | 8.6 | 11.8 | 20.7 | 25.7 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 19.3 | 18.3 | 14.3 |

| Has usual place of care: yes | 87.9 | 89.2 | 90.2 | 82.7 | 85.5 | 84.9 | 85.4 | 83.3 | 91.3 | 84.3 | 80.8 | 81.0 | 77.1 |

| No. of health care visits in the past year | |||||||||||||

| None | 13.8 | 11.3 | 13.6 | 21.4 | 18.9 | 11.7 | 12.8 | 15.4 | 8.4 | 16.7 | 21.6 | 22.6 | 23.1 |

| 1–5 | 60.2 | 60.2 | 63.7 | 57.2 | 65.5 | 49.3 | 56.4 | 62.9 | 32.0 | 52.5 | 53.2 | 52.9 | 63.1 |

| 6–12 | 16.7 | 18.0 | 16.1 | 14.0 | 11.4 | 21.4 | 26.8 | 11.0 | 5.1 | 17.0 | 18.5 | 10.3 | 11.7 |

| 13 or more | 9.3 | 10.5 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 4.2 | 17.5 | 4.0 | 10.7 | 54.4 | 13.8 | 6.7 | 14.3 | 2.0 |

All prevalence estimates (%) account for the complex survey design and may not add to 100.0% due to rounding error. Distributions of all covariates other than age are age-standardized based on the 2010 U.S. Census.

Statistical analysis

We assessed the percentage distribution of covariates and lifetime HIV testing overall and in relation to sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity among U.S. women (i.e., those who selected “female”) and men (i.e., those who selected “male”) aged 18–64 years. Distributions were age standardized by using direct standardization based on the 2010 U.S. Census.39,40 Using the adjusted Wald test, we assessed differences in the prevalence of lifetime HIV testing both across and within sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic groups among women and men. We then tested for a statistical interaction between sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity in relation to lifetime HIV testing among women and men on the multiplicative scale using logistic regression modeling (adjusting for survey year only).

Moreover, we estimated stratified multivariable logistic regression models to assess differences in the odds of lifetime HIV testing by race/ethnicity (reference: White) among sexual orientation identity groups and by sexual orientation identity (reference: heterosexual) among racial/ethnic groups.

Further, we used a 12-category variable that combined sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity and multivariable logistic regression to assess difference in the odds of having ever received an HIV test among sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups (reference: White heterosexual). We first estimated these models adjusting for survey year only and then added age followed by other demographic factors (selected a priori based on the scientific literature and conceptualized as potential confounders) into the models. All analyses were conducted in Stata 15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) and adjusted for the NHIS's complex survey design. This study, which relied on the analysis of publicly available, de-identified data, was deemed to be exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review by the Office of Human Research Administration at Harvard Longwood Medical Area.

Results

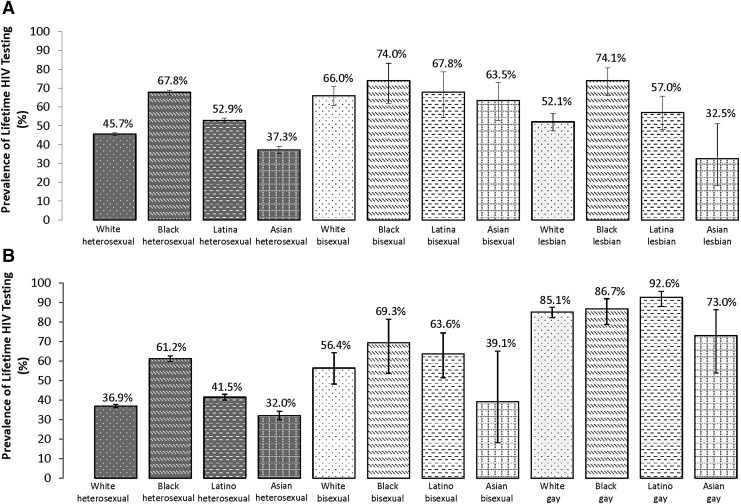

Tables 1 and 2 show that, overall, most U.S. women and men were born in the United States, living in the South, married, working for pay, and insured, had at least some college education and a usual place of care, and received one to five health care visits in the past year—with variation across sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups of women and men. Further, Table 3 indicates that a total of 49.8% of women and 41.4% of men had received an HIV test at some point in their lives. Among women, Black lesbian (74.1%) and bisexual (74.0%) women had the highest age-standardized prevalence whereas Asian lesbian women (32.5%) had the lowest age-standardized prevalence of lifetime HIV testing (Table 3 and Figure 1A). Moreover, among men, the age-standardized prevalence of lifetime HIV testing was the highest among Latino gay men (92.6%), followed by Black (86.7%) and White (85.1%) gay men, and the lowest among Asian heterosexual men (32.0%; Table 3 and Figure 1B).

Table 2.

Age-Standardized Percentage Distribution of Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Health Care Factors in Relation to Sexual Orientation Identity and Race/Ethnicity Among U.S. Men Aged 18–64 Years (N = 52,201)

| Variable (%) | Total | White heterosexual (n = 32,685) | Black heterosexual (n = 6011) | Latino heterosexual (n = 8733) | Asian heterosexual (n = 3168) | White bisexual (n = 243) | Black bisexual (n = 36) | Latino bisexual (n = 60) | Asian bisexual (n = 18) | White gay (n = 859) | Black gay (n = 130) | Latino gay (n = 208) | Asian gay (n = 50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||

| 18–29 | 25.0 | 23.3 | 26.0 | 29.1 | 28.4 | 47.1 | 31.9 | 37.6 | 31.8 | 23.7 | 37.6 | 31.7 | 50.2 |

| 30–39 | 21.2 | 19.6 | 20.7 | 27.1 | 26.3 | 14.9 | 28.0 | 25.0 | 31.9 | 20.2 | 21.1 | 20.9 | 28.9 |

| 40–49 | 20.6 | 20.1 | 20.3 | 22.4 | 23.3 | 10.5 | 16.7 | 15.2 | 10.5 | 20.0 | 20.9 | 25.2 | 11.4 |

| 50–64 | 33.2 | 36.9 | 32.9 | 21.4 | 22.0 | 27.5 | 23.3 | 22.1 | 25.8 | 36.2 | 20.4 | 22.3 | 9.4 |

| U.S.-born: yes | 82.0 | 94.7 | 85.0 | 42.7 | 24.0 | 97.3 | 82.7 | 45.9 | 37.2 | 95.6 | 96.5 | 53.6 | 52.5 |

| Geographic region | |||||||||||||

| Northeast | 16.7 | 17.4 | 14.6 | 13.6 | 20.6 | 15.7 | 23.8 | 13.0 | 41.2 | 17.6 | 23.8 | 18.6 | 17.4 |

| Midwest | 24.3 | 29.5 | 19.3 | 10.2 | 13.7 | 29.5 | 31.6 | 19.9 | 6.2 | 22.6 | 15.5 | 8.4 | 4.9 |

| South | 36.0 | 32.7 | 57.8 | 38.3 | 24.7 | 26.2 | 39.3 | 38.8 | 18.2 | 32.5 | 48.8 | 35.6 | 18.6 |

| West | 22.9 | 20.4 | 8.2 | 37.8 | 41.1 | 28.6 | 5.4 | 28.3 | 34.5 | 27.3 | 11.9 | 37.5 | 59.1 |

| Relationship status | |||||||||||||

| Never married | 32.7 | 31.2 | 40.4 | 27.8 | 32.7 | 53.6 | 63.5 | 45.5 | 30.8 | 59.3 | 73.5 | 53.1 | 83.6 |

| Married | 44.8 | 46.3 | 32.0 | 49.4 | 57.1 | 19.1 | 16.4 | 18.9 | 50.4 | 15.7 | 8.6 | 17.5 | 15.9 |

| Living with a partner | 7.6 | 7.3 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 2.3 | 7.9 | 9.9 | 7.6 | 0.0 | 18.5 | 8.5 | 18.1 | 0.6 |

| Divorced, widowed, or separated | 14.9 | 15.3 | 19.2 | 13.8 | 7.9 | 19.4 | 10.2 | 28.0 | 18.8 | 6.5 | 9.5 | 11.3 | 0.0 |

| Educational attainment | |||||||||||||

| Less than high school degree | 11.0 | 7.1 | 12.2 | 30.6 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 16.6 | 19.9 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 9.1 | 10.8 | 1.2 |

| High school diploma or GED | 24.9 | 24.1 | 33.5 | 27.4 | 12.3 | 17.6 | 26.6 | 23.9 | 3.7 | 13.8 | 25.6 | 19.8 | 9.6 |

| Some college or associate's degree | 31.3 | 33.1 | 32.3 | 26.4 | 20.4 | 39.6 | 26.2 | 29.2 | 21.2 | 30.4 | 38.6 | 31.1 | 13.7 |

| Bachelor's degree or more | 32.8 | 35.7 | 21.9 | 15.6 | 60.9 | 36.7 | 30.6 | 27.0 | 75.1 | 52.9 | 26.7 | 38.3 | 75.5 |

| Working for pay: yes | 77.4 | 78.5 | 68.2 | 79.6 | 79.5 | 72.3 | 44.9 | 74.2 | 81.9 | 76.2 | 63.0 | 80.0 | 86.9 |

| Uninsured: yes | 15.7 | 11.7 | 20.2 | 31.0 | 10.0 | 15.7 | 30.2 | 10.4 | 0.0 | 9.5 | 16.8 | 22.6 | 6.3 |

| Has usual place of care: yes | 78.4 | 80.2 | 78.7 | 69.6 | 78.1 | 78.9 | 79.4 | 71.2 | 98.6 | 86.3 | 83.4 | 80.6 | 84.6 |

| No. of health care visits in the past year | |||||||||||||

| None | 27.6 | 25.3 | 29.4 | 37.5 | 29.0 | 24.1 | 25.7 | 24.0 | 12.8 | 13.8 | 19.5 | 20.4 | 16.5 |

| 1–5 | 57.5 | 58.9 | 56.9 | 51.1 | 62.1 | 49.4 | 54.7 | 46.1 | 77.7 | 60.8 | 65.5 | 49.8 | 75.5 |

| 6–12 | 9.9 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 7.8 | 6.5 | 14.8 | 15.3 | 23.0 | 5.8 | 13.9 | 10.0 | 20.3 | 3.7 |

| 13 or more | 5.0 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 11.7 | 4.4 | 6.9 | 3.7 | 11.5 | 4.9 | 9.5 | 4.3 |

All prevalence estimates (%) account for the complex survey design and may not add to 100.0% due to rounding error. Distributions of all covariates other than age are age-standardized based on the 2010 U.S. Census.

Table 3.

Age-Standardized Prevalence of Ever Receiving an HIV Test in Relation to Sexual Orientation Identity and Race/Ethnicity Among U.S. Women and Men Aged 18–64 Years (N = 113,068)

| Women (n = 60,867) | Men (n = 52,201) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (%) | Total | Heterosexual (n = 58,939) | Bisexual (n = 908) | Lesbian (n = 1020) | Total | Heterosexual (n = 50,597) | Bisexual (n = 357) | Gay (n = 1247) |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Total | 49.8 (49.2–50.4) | 49.5 (48.9–50.1) | 66.6 (62.0–70.9)* | 55.9 (52.4–59.5)* | 41.4 (40.7–42.1) | 40.1 (39.4–40.8) | 58.9 (52.4–65.1)* | 86.4 (84.1–88.4)* |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 46.1 (45.3–46.8) | 45.7 (44.9–46.4) | 66.0 (60.7–70.8)* | 52.1 (47.4–56.7)* | 38.3 (37.5–39.0) | 36.9 (36.1–37.7) | 56.4 (48.2–64.2)* | 85.1 (82.2–87.5)* |

| Black | 68.0 (66.7–69.2)** | 67.8 (66.4–69.0)** | 74.0 (61.9–83.2) | 74.1 (65.9–80.8)** | 61.9 (60.4–63.4)** | 61.2 (59.7–62.7)** | 69.3 (53.7–81.5) | 86.7 (78.8–91.9)* |

| Latinx | 53.0 (51.7–54.3)** | 52.9 (51.5–54.2)** | 67.8 (54.6–78.7)* | 57.0 (47.9–65.7) | 42.9 (41.4–44.3)** | 41.5 (40.0–42.9)** | 63.6 (51.4–74.4)* | 92.6 (87.9–95.6)*,** |

| Asian | 37.2 (35.4–39.0)** | 37.3 (35.4–39.2)** | 63.5 (52.8–73.0)* | 32.5 (18.1–51.2)** | 32.6 (30.4–34.8)** | 32.0 (29.9–34.2)** | 39.1 (18.2–65.0) | 73.0 (53.8–86.2)* |

Prevalence estimates (%) and 95% CIs account for the complex sampling design and are age-standardized based on the 2010 U.S. Census.

p-Value <0.05 for comparisons between heterosexual (reference), bisexual, and lesbian/gay women and men using adjusted Wald tests.

p-Value <0.05 for comparisons between White (reference), Black, Latinx, and Asian women and men using adjusted Wald tests.

CI, confidence interval.

FIG. 1.

Age-standardized prevalence of lifetime HIV testing among sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups of U.S. women (A) and men (B) aged 18–64 years (N = 113,068). HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

We found a statistically significant interaction between sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity in relation to lifetime HIV testing among both U.S. women (p = 0.04) and men (p = 0.01) on the multiplicative scale (adjusting for survey year only). Table 4 indicates that, among heterosexual women, Black (odds ratio [OR] = 2.68; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.50–2.88) and Latina (OR = 1.28; 95% CI: 1.19–1.37) women had significantly higher odds whereas Asian women (OR = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.64–0.78) had significantly lower odds of ever receiving an HIV test compared with White women, adjusting for survey year, age, and other demographic factors (Model 3, Table 4). Further, Black bisexual (OR = 3.40; 95% CI: 1.97–5.87) and lesbian (OR = 3.08; 95% CI: 1.94–4.88) women had significantly higher adjusted odds of ever receiving an HIV test relative to their White counterparts. In contrast, we observed no statistically significant difference between Latina and White women among bisexual or lesbian women. Although Asian women had appreciably lower adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing than White women among bisexual and lesbian women, this difference was not statistically significant. Moreover, White bisexual (OR = 1.85; 95% CI: 1.50–2.29) and lesbian (OR = 1.37; 95% CI: 1.11–1.70) women and Black bisexual women (OR = 1.71; 95% CI: 1.06–2.76) had significantly higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing compared with their heterosexual counterparts.

Table 4.

Adjusted Odds of Ever Receiving an HIV Test in Relation to Sexual Orientation Identity and Race/Ethnicity Among U.S. Women and Men Aged 18–64 Years (N = 113,068)

| Women (n = 60,867) | Men (n = 52,201) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 OR (95% CI) | Model 3 OR (95% CI) | Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 OR (95% CI) | Model 3 OR (95% CI) |

| Sexual Orientation Identity-Stratified Models | ||||||

| Heterosexual | ||||||

| White (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 2.63 (2.47–2.81) | 2.60 (2.43–2.78) | 2.68 (2.50–2.88) | 2.71 (2.53–2.90) | 2.77 (2.58–2.97) | 2.74 (2.55–2.94) |

| Latina/o | 1.50 (1.42–1.60) | 1.33 (1.25–1.41) | 1.28 (1.19–1.37) | 1.23 (1.15–1.31) | 1.20 (1.12–1.28) | 1.05 (0.97–1.13) |

| Asian | 0.80 (0.73–0.87) | 0.69 (0.64–0.76) | 0.71 (0.64–0.78) | 0.82 (0.74–0.91) | 0.80 (0.72–0.89) | 0.72 (0.64–0.80) |

| Bisexual | ||||||

| White (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 2.38 (1.46–3.88) | 2.71 (1.60–4.57) | 3.40 (1.97–5.87) | 2.47 (1.02–5.98) | 2.21 (0.90–5.41) | 2.67 (1.14–6.29) |

| Latina/o | 0.80 (0.51–1.26) | 0.88 (0.55–1.40) | 0.97 (0.61–1.54) | 1.83 (0.95–3.54) | 1.67 (0.83–3.33) | 2.63 (1.17–5.91) |

| Asian | 0.27 (0.10–0.73) | 0.33 (0.12–0.90) | 0.41 (0.14–1.20) | 0.46 (0.14–1.55) | 0.41 (0.11–1.47) | 0.65 (0.17–2.42) |

| Lesbian/gay | ||||||

| White (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 2.97 (1.92–4.58) | 3.03 (1.95–4.71) | 3.08 (1.94–4.88) | 1.15 (0.64–2.06) | 1.30 (0.69–2.46) | 1.43 (0.75–2.73) |

| Latina/o | 1.11 (0.73–1.68) | 1.16 (0.75–1.79) | 1.10 (0.67–1.81) | 2.09 (1.15–3.78) | 2.21 (1.22–4.01) | 2.26 (1.19–4.29) |

| Asian | 0.48 (0.20–1.15) | 0.42 (0.17–1.06) | 0.40 (0.15–1.08) | 0.54 (0.28–1.04) | 0.64 (0.33–1.23) | 0.45 (0.21–0.99) |

| Race/Ethnicity-Stratified Models | ||||||

| White | ||||||

| Heterosexual (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Bisexual | 2.11 (1.73–2.57) | 1.96 (1.60–2.40) | 1.85 (1.50–2.29) | 1.81 (1.33–2.46) | 2.10 (1.53–2.87) | 2.04 (1.47–2.82) |

| Lesbian/gay | 1.36 (1.12–1.65) | 1.37 (1.11–1.67) | 1.37 (1.11–1.70) | 9.96 (8.01–12.40) | 10.38 (8.35–12.89) | 10.10 (8.09–12.62) |

| Black | ||||||

| Heterosexual (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Bisexual | 1.82 (1.15–2.88) | 1.63 (1.02–2.60) | 1.71 (1.06–2.76) | 1.71 (0.73–4.00) | 1.73 (0.75–4.00) | 1.81 (0.76–4.28) |

| Lesbian/gay | 1.48 (1.01–2.18) | 1.28 (0.87–1.89) | 1.29 (0.87–1.91) | 4.27 (2.47–7.39) | 4.59 (2.62–8.05) | 4.86 (2.74–8.62) |

| Latina/o | ||||||

| Heterosexual (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Bisexual | 1.11 (0.75–1.66) | 1.09 (0.73–1.63) | 1.03 (0.68–1.55) | 2.62 (1.44–4.76) | 2.79 (1.53–5.11) | 2.89 (1.55–5.38) |

| Lesbian/gay | 1.02 (0.70–1.50) | 1.09 (0.73–1.61) | 1.02 (0.70–1.50) | 16.94 (9.69–29.63) | 17.91 (10.31–31.12) | 17.92 (10.29–31.19) |

| Asian | ||||||

| Heterosexual (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Bisexual | 0.78 (0.30–2.05) | 0.90 (0.33–2.42) | 0.79 (0.30–2.12) | 1.05 (0.35–3.15) | 1.07 (0.33–3.46) | 0.98 (0.32–3.03) |

| Lesbian/gay | 0.86 (0.37–1.97) | 0.76 (0.31–1.86) | 0.64 (0.25–1.68) | 6.14 (3.21–11.78) | 6.82 (3.72–12.53) | 6.43 (3.46–11.94) |

| Sexual Orientation Identity and Racial/Ethnic Subgroups | ||||||

| White heterosexual (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black heterosexual | 2.63 (2.47–2.81) | 2.60 (2.43–2.79) | 2.69 (2.50–2.88) | 2.71 (2.53–2.90) | 2.77 (2.59–2.97) | 2.74 (2.55–2.94) |

| Latinx heterosexual | 1.50 (1.42–1.60) | 1.33 (1.25–1.41) | 1.28 (1.20–1.38) | 1.23 (1.15–1.31) | 1.20 (1.12–1.28) | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) |

| Asian heterosexual | 0.80 (0.73–0.87) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) | 0.71 (0.65–0.79) | 0.82 (0.74–0.91) | 0.80 (0.72–0.89) | 0.72 (0.64–0.81) |

| White bisexual | 2.10 (1.73–2.57) | 1.92 (1.56–2.35) | 1.80 (1.46–2.22) | 1.81 (1.33–2.46) | 2.08 (1.53–2.85) | 2.03 (1.48–2.80) |

| Black bisexual | 4.82 (3.03–7.68) | 4.63 (2.87–7.47) | 5.24 (3.20–8.58) | 4.54 (1.91–10.78) | 4.70 (2.00–11.00) | 4.98 (2.14–11.61) |

| Latinx bisexual | 1.69 (1.13–2.52) | 1.49 (0.99–2.24) | 1.39 (0.93–2.10) | 3.20 (1.77–5.80) | 3.41 (1.89–6.16) | 3.09 (1.70–5.64) |

| Asian bisexual | 0.63 (0.24–1.62) | 0.60 (0.22–1.60) | 0.57 (0.21–1.50) | 0.85 (0.29–2.50) | 0.85 (0.27–2.73) | 0.77 (0.24–2.46) |

| White lesbian/gay | 1.36 (1.12–1.64) | 1.36 (1.11–1.67) | 1.34 (1.08–1.66) | 9.96 (8.00–12.39) | 10.33 (8.31–12.83) | 10.13 (8.11–12.64) |

| Black lesbian/gay | 3.92 (2.67–5.75) | 3.51 (2.40–5.13) | 3.84 (2.60–5.65) | 11.62 (6.73–20.06) | 12.60 (7.22–21.96) | 12.91 (7.36–22.64) |

| Latinx lesbian/gay | 1.53 (1.05–2.22) | 1.47 (0.99–2.20) | 1.37 (0.91–2.06) | 20.81 (11.85–36.57) | 21.89 (12.57–38.11) | 19.19 (11.01–33.44) |

| Asian lesbian/gay | 0.68 (0.29–1.55) | 0.53 (0.22–1.28) | 0.49 (0.19–1.25) | 5.14 (2.70–9.79) | 5.73 (3.13–10.50) | 5.14 (2.76–9.56) |

Bolded values refer to ORs with 95% CIs that exclude 1. Model 1 is adjusted for survey year only. Model 2 adds age to Model 1. Model 3 adds other demographic factors (i.e., nativity, geographic region, and relationship status) to Model 2. All models account for the complex survey design.

OR, odds ratio.

In contrast, we observed no statistically significant sexual orientation identity-related differences among Latina women. Although bisexual and lesbian women had appreciably lower adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing than their heterosexual counterparts among Asian women, these differences were not statistically significant. Lastly, compared with White heterosexual women, Black (OR = 2.69; 95% CI: 2.50–2.88) and Latina (OR = 1.28; 95% CI: 1.20–1.38) heterosexual women, White (OR = 1.80; 95% CI: 1.46–2.22) and Black (OR = 5.24; 95% CI: 3.20–8.58) bisexual women, and White (OR = 1.34; 95% CI: 1.08–1.66) and Black (OR = 3.84; 95% CI: 2.60–5.65) lesbian women had significantly higher adjusted odds whereas Asian heterosexual women (OR = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.65–0.79) had significantly lower adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing. Although Latina bisexual and lesbian women appeared to have higher adjusted odds whereas Asian bisexual and lesbian women appeared to have lower fully adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing than White heterosexual women, these differences were not statistically significant (Model 3, Table 4).

Table 4 also shows that Black heterosexual men (OR = 2.74; 95% CI: 2.55–2.94) had significantly higher adjusted odds whereas Asian heterosexual men (OR = 0.72; 95% CI: 0.64–0.80) had significantly lower adjusted odds of obtaining an HIV test in their lifetime compared with their White counterparts (Model 3). Among bisexual men, Black (OR = 2.67; 95% CI: 1.14–6.29) and Latino (OR = 2.63; 95% CI: 1.17–5.91) men had significantly higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing relative to White men. Although the adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing were appreciably lower among Asian compared with White bisexual men, this difference was not statistically significant. Further, among gay men, Latino men (OR = 2.26; 95% CI: 1.19–4.29) had significantly higher adjusted odds whereas Asian men (OR = 0.45; 95% CI: 0.21–0.99) had significantly lower adjusted odds of ever receiving an HIV test compared with White men. Although Black men appeared to have higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing than White men among gay men, this difference was not statistically significant. In addition, bisexual (OR = 2.04; 95% CI: 1.47–2.82) and gay (OR = 10.10; 95% CI: 8.09–12.62) men had significantly higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing relative to heterosexual men among White men; we observed similar differences between Latino bisexual (OR = 2.89; 95% CI: 1.55–5.38) and gay (OR = 17.92; 95% CI: 10.29–31.19) men and their heterosexual counterparts.

Among Black men, bisexual and gay men appeared to have higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing relative to heterosexual men; however, the difference was only statistically significant for gay men (OR = 4.86; 95% CI: 2.74–8.62). Among Asian men, we observed no appreciable difference between bisexual and heterosexual men but found that gay men had significantly higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing relative to their heterosexual counterparts (OR = 6.43; 95% CI: 3.46–11.94). Lastly, compared with White heterosexual men, Black heterosexual men (OR = 2.74; 95% CI: 2.55–2.94), White (OR = 2.03; 95% CI: 1.48–2.80), Black (OR = 4.98; 95% CI: 2.14–11.61), and Latino (OR = 3.09; 95% CI: 1.70–5.64) bisexual men, and White (OR = 10.13; 95% CI: 8.11–12.64), Black (OR = 12.91; 95% CI: 7.36–22.64), Latino (OR = 19.19; 95% CI: 11.01–33.44), and Asian (OR = 5.14; 95% CI: 2.76–9.56) gay men had significantly higher adjusted odds whereas Asian heterosexual men (OR = 0.72; 95% CI: 0.64–0.81) had significantly lower adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing. In contrast, we observed no appreciable difference between Latino and White heterosexual men. Although Asian bisexual men appeared to have lower adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing than White heterosexual men, this difference was not statistically significant (Model 3, Table 4).

Discussion

Using intersectionality30–35 as an analytic framework allowed us to address many of the conceptual and methodological limitations of prior studies on sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and lifetime HIV testing among U.S. women and men. Indeed, unlike prior research,16,17 our study examined not only sexual orientation identity-related differences in lifetime HIV testing within racial/ethnic groups but also race/ethnicity-related differences within sexual orientation identity groups of women and men separately. Moreover, this study also compared the prevalence of ever receiving an HIV test among sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups of women and men relative to their White heterosexual counterparts. In addition, these analyses included Asian women and men, who have been excluded from most prior research on HIV testing, and disaggregated gay or lesbian and bisexual individuals, who have been combined into single categories in several previous studies.16,17 Therefore, our study provides a more comprehensive assessment of the mutually influencing effects of sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity on lifetime HIV testing among U.S. women and men, which will help inform the development of tailored culturally relevant and structurally competent interventions.

By using an intersectional approach and a large national probability sample, this study identified previously unanalyzed, nationally representative prevalence estimates and patterns in lifetime HIV testing related to both sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity among U.S. women and men. Specifically, we found that the prevalence of lifetime HIV testing was below the Healthy People 2020 objective of 73.6%36 among most sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups of women and men, with the exception of Black lesbian and bisexual women and White, Black, and Latino gay men. Further, our study extends the findings of prior research16,17 by identifying a statistically significant interaction between sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity on the multiplicative scale in relation to the odds of lifetime HIV testing among both women and men and indicating that social factors related to being a Black woman, a Black or Latino man, a bisexual woman, or a gay man in U.S. society may independently or simultaneously be associated with higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing whereas social factors linked to being Asian may be associated with lower odds of ever receiving an HIV test.

Specifically, we found that the adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing may be higher among Black women and Black (and in some cases Latino) men and lower among Asian women and men compared with their White counterparts across all sexual orientation identity groups. In addition, bisexual women had higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing relative to heterosexual women among Black and White women, and gay men had higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing compared with heterosexual men among White, Black, Latino, and Asian men. Moreover, our results show that women who identified as both Black and bisexual had the highest adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing among all subgroups of women relative to White heterosexual women. In addition, men who identified as both Black or Latino and gay had the highest adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing among all subgroups of men relative to White heterosexual men. In contrast, Asian women and men from all sexual orientation identities (with the exception of Asian gay men) may have lower adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing relative to their White heterosexual counterparts.

We used intersectionality to interpret observed differences in lifetime HIV testing in relation to sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity among U.S. women and men. First, the higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing among Black heterosexual, bisexual, and gay men and White and Latino bisexual and gay men (especially Black and Latino gay and bisexual men) relative to White heterosexual men may be due to the elevated prevalence of HIV/AIDS among Black and Latino men and bisexual and gay men in general and Black and Latino gay and bisexual men in particular.6 The high burden of HIV/AIDS in these populations may lead to increased health care provider recommendation of HIV testing (indeed, HIV testing is recommended annually for MSM as opposed to once in a lifetime12) as well as uptake of HIV tests in these groups compared with others with a lower prevalence of HIV/AIDS.17,41 Further, HIV testing and prevention campaigns tend to target Black and MSM communities in general42 and Black43,44 and Latino MSM45–47 in particular, which may facilitate awareness of, access to, and utilization of HIV tests in these populations. In addition, health care providers' stereotypes about Black and Latinx individuals' and gay and bisexual men's sexual behavior (e.g., multiple sexual partners, unprotected sex) may, both alone and together, lead them to assume that individuals from these groups (especially Black and Latino gay and bisexual men) are at high risk for HIV and encourage them to obtain HIV tests more frequently than their White and heterosexual counterparts, regardless of their personal HIV risk profile.48–52

Second, the higher adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing among Black heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women and White bisexual and lesbian women (especially Black bisexual women) compared with White heterosexual women may be due to the high prevalence of HIV risk factors among Black53,54 and bisexual3–5 women in general and Black bisexual women in particular,8,9 which may lead to higher health care provider recommendation and patient uptake of HIV testing in these groups relative to others. Moreover, bias, assumptions, and stereotypes pertaining to Black and bisexual women's sexuality (e.g., erroneous and racist beliefs of promiscuity and hypersexuality) may lead health care providers to recommend HIV tests more frequently to women from these groups (especially Black bisexual women) than to White and heterosexual women, regardless of their individual sexual histories and HIV risk.48,49,51,52,55–58

Third, the lower adjusted odds of lifetime HIV testing among Asian heterosexual women and men, and possibly also Asian bisexual women and men and Asian lesbian women, relative to their White heterosexual counterparts may be due to HIV-related stigma,59 low self-perceived HIV risk,60,61 immigration- and language-related barriers to health care,62 a lack of culturally relevant and linguistically appropriate HIV testing services and campaigns,63,64 and health care provider perceptions of low HIV risk and lack of HIV testing recommendation among these groups.65

Limitations

Although our study relied on a large national probability sample and addressed several gaps in the scientific literature, our results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, analyses were based on self-reported, cross-sectional data such that HIV testing was not confirmed by using medical records and temporality and causality could not be established. Second, as a result of their small numbers in our study, estimates for Asian individuals often did not reach statistical significance, and we were not able to include Native American and multiracial individuals in the present analyses. Third, gender identity was not explicitly measured in the survey, and it is not possible to know whether participants responded to the survey's sex question based on their assigned sex at birth or current gender identity; thus, we were unable to categorize participants based on their self-reported gender identity or transgender status. Fourth, this study did not identify potential mechanisms of lifetime HIV testing differences at the intersection of sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity among women and men, which would have helped identify potential interventions that may mitigate disparities and increase low levels of HIV testing. Lastly, although we conceptualized sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity as individual-level social categories linked to both social identity and social inequality per intersectionality,30–32 we were unable to assess the effect of heterosexism or racism on lifetime HIV testing in this study.

Future research directions

Therefore, research that includes larger numbers of under- or un-represented sexual orientation identity, racial/ethnic, and gender identity subgroups, leverages longitudinal study designs, and examines the role of potential mechanisms is warranted. Moreover, studies that include measures of heterosexism, racism, sexism, and transphobia at the interpersonal and structural level are needed to further elucidate differences in lifetime HIV testing among sexual orientation identity, racial/ethnic, and gender identity subgroups from an intersectional perspective. Moreover, research that examines how other social categories (e.g., socioeconomic position, nativity) and related forms of discrimination (e.g., classism, xenophobia) intersect with sexual orientation identity and heterosexism, race/ethnicity and racism, and gender identity and sexism and transphobia to shape lifetime HIV testing in the United States is also warranted. Lastly, additional quantitative and qualitative research is needed to understand how social factors at the individual (e.g., HIV risk perceptions), interpersonal (e.g., patient–provider communication), institutional (e.g., access to health insurance), community (e.g., HIV testing norms), and structural (e.g., state health policies) levels contribute to differences in lifetime HIV testing across and within social groups situated at the intersection of sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, gender identity, and other social categories.

Conclusion

Using an intersectional approach to design our study, conceptualize our variables, analyze our data, and interpret our study results allowed us to identify and begin to understand the previously unanalyzed distribution of lifetime HIV testing in relation to both sexual orientation identity and race/ethnicity among U.S. women and men, including among multiply marginalized subgroups that are undertested or disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS. Our findings suggest that, among the vast majority of sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups of women and men with a prevalence of lifetime HIV testing below the Healthy People 2020 objective of 73.6%,36 culturally relevant, linguistically appropriate, and structurally competent health care practices (e.g., health care provider recommendation66–69) and public health initiatives (e.g., community-based programs70,71) that facilitate awareness of, access to, and utilization of HIV tests according to CDC guidelines are needed.

In addition, our study results indicate that patient-centered lifetime HIV testing interventions that address and are tailored to the unique needs and experiences of Asian women and men from diverse sexual orientation identity backgrounds, among whom lifetime HIV testing tended to be particularly low, are especially warranted. Further, among sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups of women and men with a prevalence of lifetime HIV testing that meets the Healthy People 2020 lifetime HIV testing objective, including Black lesbian and bisexual women and White, Black, and Latino gay men, health care institutions and public health programs should ensure that testing services address individuals' lived experiences at the intersection of sexual orientation identity and heterosexism and race/ethnicity and racism, relevant and accessible HIV prevention information and counseling is provided, HIV stigma is addressed, and HIV-positive individuals are linked to high-quality care.66,72–76 Together, these efforts will help prevent HIV/AIDS among diverse sexual orientation identity and racial/ethnic subgroups of U.S. women and men, including multiply marginalized subgroups that are undertested or disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS—which will, in turn, help promote not only population health but also health equity vis-à-vis HIV-related outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the 2013–2017 NHIS study participants and staff for the data used in this study. They also thank the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and Expression (SOGIE) Working Group at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health for their feedback on the data analyses presented in this article. The preparation of this article was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant 1R25GM111837-01.

Disclaimer

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2016. HIV Surveillance Report. 2017. Available at www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf Accessed July28, 2018

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States and dependent areas. Page last updated: January 29, 2019. Available at www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html Accessed April2, 2019

- 3. Saewyc E, Skay C, Richens K, et al. : Sexual orientation, sexual abuse, and HIV-risk behaviors among adolescents in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1104–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goodenow C, Szalacha LA, Robin LE, Westheimer K: Dimensions of sexual orientation and HIV-related risk among adolescent females: Evidence from a statewide survey. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1051–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Everett BG: Sexual orientation disparities in sexually transmitted infections: Examining the intersection between sexual identity and sexual behavior. Arch Sex Behav 2013;42:225–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among men in the United States. Page last updated: March 9, 2017. Available at www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/men/index.html Accessed September24, 2018

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among women. Page last updated: March 19, 2019. Available at www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html Accessed April2, 2019

- 8. Muzny CA, Pérez AE, Eaton EF, Agénor M: Psychosocial stressors and sexual health among southern African American women who have sex with women. LGBT Health 2018;5:234–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ward BW, Dahlhamer JM, Galinsky AM, Joestl SS: Sexual orientation and health among US adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2013. Natl Health Stat Report 2014;15:1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. : Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55:1–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shah M, Risher K, Berry SA, Dowdy DW: The epidemiologic and economic impact of improving HIV testing, linkage, and retention in care in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:220–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DiNenno EA, Prejean J, Irwin K, et al. : Recommendations for HIV screening of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:830–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agénor M, Muzny CA, Schick V, et al. : Sexual orientation and sexual health services utilization among women in the United States. Prev Med 2017;95:74–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jackson CL, Agénor M, Johnson DA, et al. : Sexual orientation identity disparities in health behaviors, outcomes, and services use among men and women in the United States: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ebrahim SH, Anderson JE, Weidle P, Purcell DW: Race/ethnic disparities in HIV testing and knowledge about treatment for HIV/AIDS: United States, 2001. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2004;18:27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lo CC, Runnels RC, Cheng TC: Racial/ethnic differences in HIV testing: An application of the health services utilization model. SAGE Open Med 2018;6:2050312118783414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trinh MH, Agénor M, Austin SB, Jackson CL: Health and healthcare disparities among U.S. women and men at the intersection of sexual orientation and race/ethnicity: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017;17:964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heckman TG, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, et al. : HIV risk differences between African-American and white men who have sex with men. J Natl Med Assoc 1999;91:92–100 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arnold EA, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM: “Triply cursed”: Racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young Black gay men. Cult Health Sex 2014;16:710–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R: Explaining disparities in HIV infection among Black and white men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS 2007;21:2083–2091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rendina HJ, Jimenez RH, Grov C, et al. : Patterns of lifetime and recent HIV testing among men who have sex with men in New York City who use Grindr. AIDS Behav 2014;18:41–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mannheimer SB, Wang L, Wilton L, et al. : Infrequent HIV testing and late HIV diagnosis are common among a cohort of Black men who have sex with men in six US cities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;67:438–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Metheny N, Stephenson R: Disclosure of sexual orientation and uptake of HIV testing and hepatitis vaccination for rural men who have sex with men. Ann Fam Med 2016;14:155–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nelson KM, Pantalone DW, Gamarel KE, et al. : Correlates of never testing for HIV among sexually active internet-recruited gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2018;32:9–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Operario D, Gamarel KE, Grin BM, et al. : Sexual minority health disparities in adult men and women in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2010. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e27–e34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Combahee River Collective: A Black feminist statement. In: All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women's Studies. Edited by Hull GT, Bell-Scott P, Smith B. New York: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1982, pp 13–22 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davis AY: Women, Race, & Class. New York: Vintage Books, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 28. hooks b: Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. Boston, MA: South End Press, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Collins PH: Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, Revised 10th Anniversary, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Collins PH, Bilge S: Intersectionality. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bowleg L: The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—An important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1267–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Crenshaw K: Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum 1989;1989:139–167 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Else-Quest NM, Hyde JS: Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: II. Methods and techniques. Psychol Women Q 2016;40:319–336 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Else-Quest NM, Hyde JS: Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: I. Theoretical and epistemological issues. Psychol Women Q 2016;40:155–170 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bowleg L, Bauer G: Invited reflection: Quantifying intersectionality. Psychol Women Q 2016;40:337–341 [Google Scholar]

- 36. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. HIV. Page last updated: April 4, 2019. Available at www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/hiv/objectives Accessed April4, 2019

- 37. Parsons VL, Moriarity CL, Jonas K, et al. : Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2015. Vital Health Stat 2 2014:1–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Division of Health Interview Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics: NHIS Survey Description, National Health Interview Survey, 2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Hyattsville, MD, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 39. U.S. Census Bureau. Profile of general population and housing characteristics: 2010. Available at https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/download_center.xhtml Accessed July8, 2018

- 40. Aschengrau A, Seage GR: Essentials of Epidemiology in Public Health, 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cooley LA, Oster AM, Rose CE, et al. : Increases in HIV testing among men who have sex with men—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 20 US metropolitan statistical areas, 2008 and 2011. PLoS One 2014;9:e104162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. French RS, Bonell C, Wellings K, Weatherburn P: An exploratory review of HIV prevention mass media campaigns targeting men who have sex with men. BMC Public Health 2014;14:616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, et al. : A systematic review of HIV interventions for Black men who have sex with men (MSM). BMC Public Health 2013;13:625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Testing makes us stronger. Page last updated: March 26, 2019. Available at www.cdc.gov/actagainstaids/campaigns/tmus/index.html Accessed April4, 2019

- 45. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reasons. Page last updated: March 26, 2019. Available at www.cdc.gov/actagainstaids/campaigns/reasons/index.html Accessed April4, 2019

- 46. Solorio R, Norton-Shelpuk P, Forehand M, et al. : Tu Amigo Pepe: Evaluation of a multi-media marketing campaign that targets young Latino immigrant MSM with HIV testing messages. AIDS Behav 2016;20:1973–1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Martínez-Donate AP, Zellner JA, Sañudo F, et al. : Hombres Sanos: Evaluation of a social marketing campaign for heterosexually identified Latino men who have sex with men and women. Am J Public Health 2010;100:2532–2540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. : Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e60–e76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dovidio JF, Fiske ST: Under the radar: How unexamined biases in decision-making processes in clinical interactions can contribute to health care disparities. Am J Public Health 2012;102:945–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bowleg L: “Once you've blended the cake, you can't take the parts back to the main ingredients”: Black gay and bisexual men's descriptions and experiences of intersectionality. Sex Roles 2013;68:754–767 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Collins PH: Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism. New York: Routledge, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Israel T, Mohr JJ: Attitudes toward bisexual women and men: Current research, future directions. J Bisexuality 2004;4:117–134 [Google Scholar]

- 53. McNair LD, Prather CM: African American women and AIDS: Factors influencing risk and reaction to HIV disease. J Black Psychol 2004;30:106–123 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moreno CL, EI-Bassel N, Morrill AC: Heterosexual women of color and HIV risk: Sexual risk factors for HIV among Latina and African American women. Women Health 2007;45:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Greene B: African American lesbian and bisexual women. J Soc Issues 2000;56:239–249 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Klesse C: Bisexual women, non-monogamy and differentialist anti-promiscuity discourses. Sexualities 2005;8:445–464 [Google Scholar]

- 57. West CM: Mammy, Sapphire, and Jezebel: Historical images of Black women and their implications for psychotherapy. Psychother Theor Res Pract Train 1995;32:458–466 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sabin JA, Riskind RG, Nosek BA: Health care providers' implicit and explicit attitudes toward lesbian women and gay men. Am J Public Health 2015;105:1831–1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kang E, Rapkin BD, Springer C, Kim JH: The “demon plague” and access to care among Asian undocumented immigrants living with HIV disease in New York City. J Immigr Health 2003;5:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murray K, Oraka E: Racial and ethnic disparities in future testing intentions for HIV: United States, 2007–2010: Results from the National Health Interview Survey. AIDS Behav 2014;18:1247–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Huang ZJ, Wong FY, De Leon JM, Park RJ: Self-reported HIV testing behaviors among a sample of southeast Asians in an urban setting in the United States. AIDS Educ Prev 2008;20:65–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wong FY, Nehl EJ, Han JJ, et al. : HIV testing and management: Findings from a national sample of Asian/Pacific islander men who have sex with men. Public Health Rep 2012;127:186–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vu L, Choi KH, Do T: Correlates of sexual, ethnic, and dual identity: A study of young Asian and Pacific Islander men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev 2011;23:423–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wyatt GE, Williams JK, Gupta A, Malebranche D: Are cultural values and beliefs included in U.S. based HIV interventions? Prev Med 2012;55:362–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wall KM, Khosropour CM, Sullivan PS: Offering of HIV screening to men who have sex with men by their health care providers and associated factors. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2010;9:284–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schwarcz S, Richards TA, Frank H, et al. : Identifying barriers to HIV testing: Personal and contextual factors associated with late HIV testing. AIDS Care 2011;23:892–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zheng MY, Suneja A, Chou AL, Arya M: Physician barriers to successful implementation of US Preventive Services Task Force routine HIV testing recommendations. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2014;13:200–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lyss SB, Branson BM, Kroc KA, et al. : Detecting unsuspected HIV infection with a rapid whole-blood HIV test in an urban emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;44:435–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fernández MI, Bowen GS, Perrino T, et al. : Promoting HIV testing among never-tested Hispanic men: A doctor's recommendation may suffice. AIDS Behav 2003;7:253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bowles KE, Clark HA, Tai E, et al. : Implementing rapid HIV testing in outreach and community settings: Results from an advancing HIV prevention demonstration project conducted in seven U.S. cities. Public Health Rep 2008;123:78–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Williams MV, Palar K, Derose KP: Congregation-based programs to address HIV/AIDS: Elements of successful implementation. J Urban Health 2011;88:517–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chin MH, Lopez FY, Nathan AG, Cook SC: Improving shared decision making with LGBT racial and ethnic minority patients. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:591–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Metzl JM, Hansen H: Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med 2014;103:126–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mayer KH, Powderly WG, Mayer KH: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revised guidelines for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) counseling, testing, and referral: Targeting HIV specialists. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:813–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Epstein RM, Street RL, Jr.: The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:100–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S: Shared decision making—The pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 2012;366:780–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]