Abstract

Purpose: This study examines trends in Medicare beneficiaries' mental health care use from 2009 to 2014 by gender minority and disability status.

Methods: Using 2009 to 2014 Medicare claims, we modeled mental health care use (outpatient mental health care, inpatient mental health care, and psychotropic drugs) over time, adjusting for age and behavioral health diagnoses. We compared trends for gender minority beneficiaries (identified using diagnosis codes) to trends for a 5% random sample of other beneficiaries, stratified by original entitlement reason (age vs. disability).

Results: Adjusted outpatient and inpatient mental health care use decreased and differences generally narrowed between gender minority and other beneficiaries over the study period. Among beneficiaries qualifying through disability, the gap in the number of outpatient and inpatient visits (among those with at least one visit in a given year) widened. Psychotropic drug use rose for all beneficiaries, but the proportion of gender minority beneficiaries in the aged cohort who had a psychotropic medication prescription rose faster than for other aged beneficiaries.

Conclusions: Mental health care needs for Medicare beneficiaries may be met increasingly by using psychotropic medications rather than outpatient visits, and this pattern is more pronounced for identified gender minority (especially aged) beneficiaries. These trends may indicate a growing need for research and provider training in safe and effective psychotropic medication prescribing alongside gender-affirming treatments such as hormone therapy, especially for aged gender minority individuals who likely already experience polypharmacy.

Keywords: disparities, gender dysphoria, gender minority, Medicare, mental health, transgender

Introduction

Over the last two decades, increased community organizing and empowerment within the transgender and gender non-binary communities (hereafter referred to as “gender minority individuals” when discussed together) have resulted in growing public awareness of social and health issues faced by these communities.1–5 The first Transgender Day of Remembrance in 1999 coincided with the beginning of this period. Since then, there has been an increase in both public health research with gender minority populations and policies relevant to gender identity.

From 2007 to 2015, 75 gender identity-related federal nondiscrimination policies were introduced in Congress.6 In May 2014, the United States Department of Health and Human Services reversed the Medicare policy on not covering gender-affirming surgery.7 The rate of PubMed-indexed articles with the terms “transgender” or “gender minority” in the title or abstract increased from 1.3 per 100,000 indexed articles in 2000 to 9.4 in 2009, reached 33.6 in 2014, and has continued to rise (results not shown). The 2011 Institute of Medicine report on the health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) people identified the need for more research on gender minority health and mental health disparities,8 and yet population-level data for gender minority individuals are scarce8 because few health databases collect information on gender identity.9

Existing data show that gender minority individuals often report discrimination in employment, housing, and health care,10–16 and experience structural barriers to wellness, such as poverty, disproportionately.8,17–21 They are also less likely to have health insurance22 or access regular primary care23,24 than the general population, despite having a higher physical and mental illness burden.18,25–30 In the context of a rapidly changing policy environment, we identified a gap in the evidence on trends in mental health care use by gender minority Medicare beneficiaries, a population that has higher rates of mental health conditions and mental health care use than other beneficiaries.18,26,31

We sought to fill this gap with this study by comparing trends from 2009 to 2014 in mental health care use by gender minority beneficiaries versus other Medicare beneficiaries, stratified by age versus disability status. Following the Institute of Medicine's definition of disparities32—differences in care due to clinical need only—we adjusted for age and behavioral health diagnoses, but not for socioeconomic status or other structural factors. This analysis sought to answer the question of whether mental health care utilization patterns from 2009 to 2014 for identified gender minority individuals were similar to those for other beneficiaries. We hypothesized that because of growing awareness of health disparities for this population, identified gender minority beneficiaries would have increased outpatient mental health care utilization and psychotropic drug use, but reduced inpatient mental health care utilization, relative to other beneficiaries. This study aims to inform policymakers and health systems seeking to understand and anticipate service needs for this population.

Methods

Cohort construction

In 100% of 2009–2014 Medicare Inpatient, Outpatient, Skilled Nursing Facility, Home Health, Carrier, and Part D Event Files claims, we identified gender minority beneficiaries using diagnosis codes as in previous analyses of the gender minority Medicare cohort,18,26,31 which identified individuals using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes for “Gender identity disorder in adolescents or adults” (302.85) and “Gender identity disorder in children” (302.6), or codes for “Trans-sexualism” (“with unspecified sexual history”: 302.50; “with asexual history”: 302.51; “with homosexual history”: 302.52; or “with heterosexual history”: 302.53). We applied the algorithm as described in prior work: beneficiaries were counted in the gender minority sample if they had at least one additional occurrence of one of the diagnosis codes within the same year or in a prior or subsequent year, or if they had received hormone therapy (for full details, see Proctor et al.18 or the online appendix from Progovac et al.26).

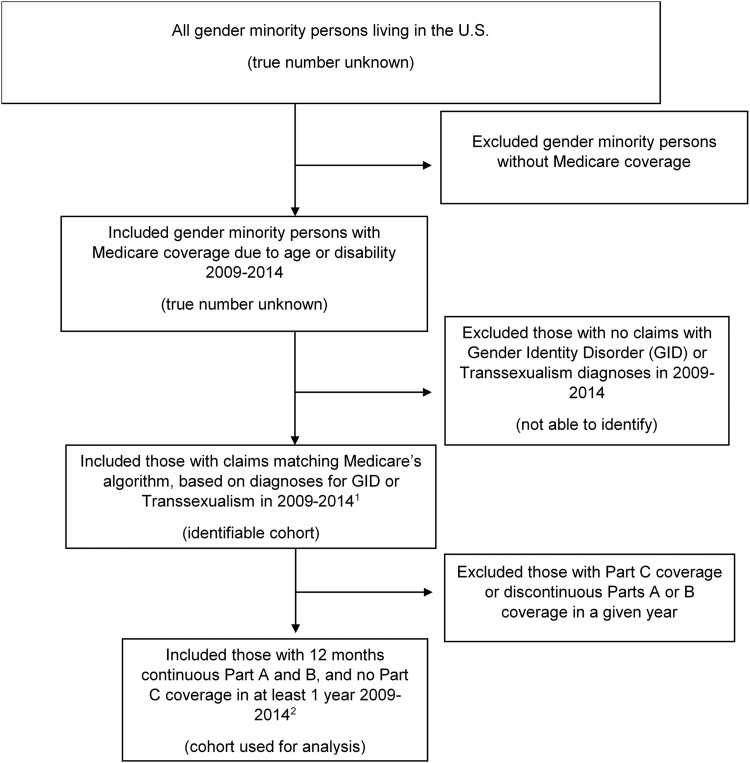

This sample is only a subset of gender minority beneficiaries (Fig. 1). The diagnosis codes used in the algorithm appear in billing claims when individuals receive medical care related to their gender identity. For example, treatments include hormone therapy (note that Medicare did not cover gender-affirming surgeries before 2014) and mental health treatment to address distress due to a mismatch between gender identity and sex assigned at birth. We also constructed a comparison group of other beneficiaries using a 5% random sample of all Medicare beneficiaries (excluding gender minority beneficiaries).

FIG. 1.

Conceptual overview of gender minority beneficiaries identified using Medicare's claims-based diagnosis algorithm. 1The identification algorithm cannot account for differential use of diagnosis codes by the provider. In addition, persons who do not seek medical treatment related to their gender identity (e.g., hormones) would be less likely to receive these diagnosis codes. 2These inclusion/exclusion criteria for Parts A, B, and C coverage also applied to the comparison cohort. The comparison cohort was also required to have at least one non-pharmacy claim of any type in a given year.

We included beneficiaries enrolled continuously in Medicare Parts A and B and never in Part C (Medicare Advantage; these claims were not available) for 12 months in each year, excluding beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease. We stratified analyses by beneficiaries' original reason for Medicare entitlement, age 65 years or older versus disability (which included the originally disabled who later reached age 65). We included comparison beneficiaries with at least one non-pharmacy claim in each year to improve comparability by requiring some use of care.26 Our final analytic cohort included n = 542,479 beneficiaries originally eligible due to disability (6678 gender minority beneficiaries and 535,801 other beneficiaries) and n = 1,702,026 beneficiaries originally eligible due to age (2018 gender minority and 1,700,008 other beneficiaries). This study received Institutional Review Board approval from Cambridge Health Alliance (CHA-IRB-1064/05/17).

Demographic information

Demographic information (age, dual eligibility status, and race/ethnicity) was captured from the annual Medicare Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF). The MBSF also contains Medicare Chronic Conditions Warehouse flags for “chronic or potentially disabling conditions” diagnoses, including behavioral and physical health conditions based on ICD-9 codes33; we used these indicator flags for descriptive analyses and we used the subset pertaining to behavioral health conditions in adjusted regression models.

Mental health care use

We measured three types of mental health care use: outpatient visits, inpatient visits, and psychotropic drug claims. We began by identifying claims with mental health diagnosis codes (ICD-9 codes 291, 292, or 295–31434), excluding codes used to identify gender minority beneficiaries.26 That is, mental health visits that included only diagnosis codes used to identify gender minority beneficiaries were excluded from this comparative analysis because these codes were used to identify the gender minority sample, and therefore, mental health visits solely for treatment of “gender identity disorder” or “transsexualism” would be universally present in the gender minority sample and universally absent in the comparison sample. We then categorized the visits as inpatient or outpatient.35 Outpatient mental health visits had a mental health diagnosis code in the first position on a Part B Carrier or Outpatient claim file and a place of service code of homeless shelter, office, mobile unit, outpatient hospital, independent clinic, Federally Qualified Health Center, community mental health center, public health clinic, or rural health clinic as in prior literature.35 Because we do not differentiate by specific types of outpatient mental health procedures, this outcome measure includes all types of outpatient mental health visits, for example, those for individual or group psychotherapy, diagnostic evaluations or screenings, and medication management. When multiple claims were recorded in both the Carrier and Outpatient files in the same day, we took the maximum number of the two for count variables.

Inpatient mental health visits had one of the mental health diagnosis codes in either the admitting or primary diagnosis location on the Inpatient file, and were limited to acute care facilities, including psychiatric hospitals.26,35 We identified psychotropic drug use from the Part D Event file (outpatient pharmacy claims) using psychotropic medication lists from prior literature in Medicare.36 We recorded outpatient and inpatient mental health care use with binary indicators for any visit and the number of visits (given any visits) in each year. We measured psychotropic medication use as a binary variable indicating any use in each year.

Covariates

To capture group differences in mental health care service utilization, which were not due merely to group differences in mental health diagnoses, we used the Institute of Medicine's definition of disparities32 to measure disparate mental health service use in line with prior literature.37 This definition posits that a disparity between two groups in mental health care service use is the difference that remains after accounting for differences in need for mental health services or preferences for using specific services. We operationalized this definition using regression models that adjust for the following: (i) age (continuous) and (ii) behavioral health diagnoses (binary indicators for 17 MBSF chronic conditions warehouse flags based on the presence of mental health or tobacco-related ICD-9 codes33; for a full list of indicators used, see the online appendix in Progovac et al.26). No comparable data for treatment preferences are available in Medicare claims. We did not include chronic physical health condition diagnoses in regression models.

Statistical analyses

Baseline demographics of gender minority Medicare beneficiaries in the analytic cohort have been reported previously and compared using chi-square and t-tests as appropriate.26 We include relevant demographic data as appropriate and also report rates of depression diagnosis (as indicated by chronic conditions flags in the MBSF) because depression is the most common mental health diagnosis among gender minority individuals in Medicare.18 We also report rates of any outpatient or inpatient mental health visits and psychotropic drug use, including stratified by depression diagnosis condition indicators. We modeled binary outcomes with logistic regression and number of visits outcomes with generalized linear models (gamma distribution, log link) using the GENMOD procedure. The models included an interaction between each year (modeled continuously) and gender identity to identify differences in trends by gender minority versus other beneficiaries over time. We assumed a clustered error structure at the beneficiary level to account for both within- and between-subject variance. We reported the annualized predicted population marginal means (means by group after adjusting for covariates) and the significance of the interaction between year and gender identity. Analyses were conducted in SAS® 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Description of the cohort

Table 1 summarizes the age, Medicaid dual eligibility, race/ethnicity, and mental or physical health diagnosis indicators of the cohort; additional details are published elsewhere.26 Outpatient mental health care use was higher among gender minority beneficiaries than among other beneficiaries in both the disabled group (60% vs. 26%) and the aged group (21% vs. 7%). In the disabled group, 10% of gender minority beneficiaries used inpatient mental health care, compared to 2% of other beneficiaries. In the aged group, inpatient mental health care use was very low for both gender minority beneficiaries (∼1%) and other beneficiaries (<1%). Psychotropic medication use was higher for gender minority beneficiaries compared to other beneficiaries in both the disabled (71% vs. 49%) and the aged (31% vs. 21%) cohorts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries Enrolled Continuously in 2009–2014, by Cohort and Gender Minority Status (Unadjusted)

|

Originally eligible due to disability N = 542,479 |

Originally eligible due to age N = 1,702,026 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender minority (n = 6678) | Other (n = 535,801) | Gender minority (n = 2018) | Other (n = 1,700,008) | |

| 65 Years and older (%) | 7 | 26 | 100 | 100 |

| Dual eligible for Medicaid (%) | 72 | 47 | 17 | 11 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 73 | 70 | 88 | 84 |

| Black or African American | 16 | 18 | 4 | 7 |

| Hispanic | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 |

| Other or unknown | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Chronic conditions (%) | ||||

| Any mental health conditions | 78 | 46 | 43 | 24 |

| Any physical health conditions | 78 | 77 | 91 | 88 |

| Two or more chronic conditions | 80 | 70 | 84 | 75 |

| Depression diagnoses | 60 | 30 | 26 | 13 |

| Mental health care use (%) | (n = 14,891 person-years) | (n = 2,203,289 person-years) | (n = 2962 person-years) | (n = 715,1126 person-years) |

| Any outpatient visit | 60 | 26 | 21 | 7 |

| With depression diagnosis | 78 | 57 | 51 | 34 |

| Without depression diagnosis | 33 | 13 | 10 | 3 |

| Any inpatient visit | 10 | 2 | 1 | <1 |

| With depression diagnosis | 15 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Without depression diagnosis | 3 | 1 | <1 | <1 |

| Any psychotropic drug use | 71 | 49 | 31 | 21 |

| With depression diagnosis | 83 | 75 | 56 | 57 |

| Without depression diagnosis | 52 | 37 | 23 | 16 |

Authors' analysis of data for 2009–2014 from the Medicare Research Identifiable Files. Demographic information was from the first year in which beneficiaries met the inclusion criteria. Mental health care use descriptors are based on comparison of person-years, and represent individuals meeting criteria for use in each year studied (2009–2014). Other beneficiaries were from a 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries in each year, who had at least one claim and who were not identified as gender minority beneficiaries. All beneficiaries in both cohorts were enrolled continuously in Medicare Parts A and B (and not Part C) for 12 months in each year studied. Inclusion criteria for other beneficiaries also included at least one non-pharmacy claim in the year studied. Beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease were excluded. All demographic comparisons between gender minority and other beneficiaries were significant (p < 0.001), except for any physical health condition in the disabled cohort. Service use was not compared statistically in Table 1.

Depression was twice as common for gender minority beneficiaries than for other beneficiaries in both the disabled group (60% vs. 30%) and the aged group (26% vs. 13%). Use of outpatient and inpatient care was typically higher for those with depression, as was psychotropic drug use. Beneficiaries without a depression diagnosis generally had lower mental health care utilization, but gender minority beneficiaries without depression diagnoses still tended to have more mental health care utilization, than other beneficiaries without depression diagnoses.

Adjusted mental health care use over time

Disabled beneficiaries

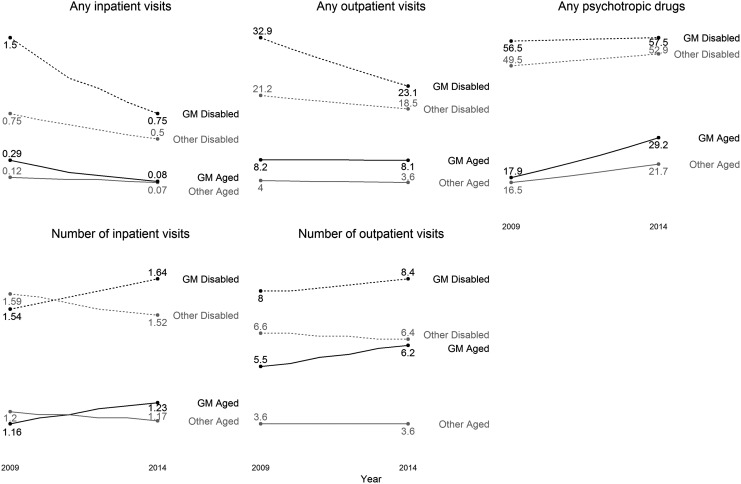

After adjusting for age and behavioral health diagnoses in the disabled cohort, gender minority beneficiaries were more likely to use any outpatient mental health care, but outpatient mental health care use generally declined in the disabled sample over time, and more quickly among disabled gender minority beneficiaries, whose rate of use fell from 32.9% to 23.1% from 2009 to 2014, whereas the rate for other beneficiaries fell from 21.2% to 18.5% (p for trends difference <0.0001, see Fig. 2). Gender minority beneficiaries also had a higher mean number of outpatient visits (conditional on having at least one visit in any year), and the adjusted mean number of outpatient visits for gender minority disabled beneficiaries grew from 8 visits in 2009 to 8.4 visits in 2014, whereas other disabled beneficiaries' mean number of visits fell from 6.6 to 6.4 (p < 0.0001).

FIG. 2.

Medicare beneficiary mental health care use 2009–2014 by gender minority and disability status. Predicted population marginal means (% for any visit; or number for number of visits). Adjusting for age and behavioral health diagnoses (as binary indicators). Mean number of visits was calculated among beneficiaries with at least one visit in each category. The p-values for trend differences are significant at p < 0.0001 in all conditions, except the following: number of outpatient visits (p = 0.563) or number of inpatient visits (p = 0.0891) in the aged cohort.

For disabled beneficiaries, rates of any inpatient mental health care use fell over time. However, rates for gender minority beneficiaries, which were nearly double that of other disabled beneficiaries in 2009, fell faster (1.5% to 0.75%) than the rates for other beneficiaries (0.75% to 0.5%). The difference in trends was significant (p < 0.0001). The mean number of inpatient visits among those with at least one visit was slightly lower in 2009 for gender minority beneficiaries compared to other disabled beneficiaries, but grew (1.54 visits to 1.64 visits) compared to the mean number for other disabled beneficiaries, which fell (1.59 visits to 1.52 visits). The difference in trends was significant, but the difference in numbers was quite small.

In the disabled group, rates of psychotropic medication use were higher in 2009 among gender minority beneficiaries. Although psychotropic medication use increased over time for all disabled beneficiaries, the rates rose slightly more slowly among disabled gender minority beneficiaries (from 56.5% to 57.5%) compared with other beneficiaries (49.5% to 52.9%; p < 0.0001 for difference in trends).

Aged beneficiaries

Compared to other beneficiaries, aged gender minority beneficiaries were also more likely to use outpatient mental health care, but while the rate of outpatient mental health care use was nearly constant among aged gender minority beneficiaries (8.2% in 2009 to 8.1% in 2014), it declined slightly among the other aged beneficiaries (4.0%–3.6%), resulting in a small, but statistically significant difference in trends (p < 0.0001). The adjusted mean number of outpatient visits (among beneficiaries with at least one visit) rose among gender minority beneficiaries versus other beneficiaries (whose number of visits remained steady), although this was not a significant finding.

Among the aged beneficiaries, the rate of having any inpatient mental health care use fell from 2009 to 2014. Aged gender minority beneficiaries' rate of inpatient mental health care use fell more quickly (0.29% to 0.08%) than it did for other aged beneficiaries (0.12% to 0.07%; p for trend difference <0.0001), such that by 2014, these groups had similar rates of use. There was no statistically significant difference in trends for the number of inpatient mental health care visits for gender minority versus other aged beneficiaries.

Mean rates of psychotropic medication use increased notably for aged beneficiaries from 2009 to 2014. Aged gender minority beneficiaries had higher rates of psychotropic medication use in 2009, and their rate of use increased more quickly (17.9% to 29.2%) than for other beneficiaries (16.5% to 21.7%) from 2009 to 2014 (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

In this study of Medicare beneficiaries, we observed high rates of mental health care use among gender minority Medicare beneficiaries compared to other beneficiaries with similar age and mental health diagnoses. Among disabled beneficiaries, and after adjusting for age and behavioral health diagnoses, we observed declines in inpatient and outpatient mental health care use as well as increased psychotropic medication use from 2009 to 2014. However, disabled gender minority beneficiaries had faster observed declines in inpatient and outpatient mental health visits, and slightly slower increasing rates of psychotropic medication use. Among aged beneficiaries, use of any inpatient mental health care declined, outpatient visit rates declined slightly, and psychotropic medication use increased markedly. Compared to other aged beneficiaries, gender minority beneficiaries had faster declines in inpatient mental health care use, slower declines in outpatient mental health care use, and faster increases in psychotropic medication use.

Although we anticipated increased outpatient mental health care utilization for gender minority beneficiaries relative to other beneficiaries, in the disabled cohort we found declining outpatient use (that outpaced declines for other disabled beneficiaries), but an increasing number of outpatient visits among those with at least one visit (compared to other beneficiaries). These results suggest that an increasingly smaller fraction of identified disabled gender minority beneficiaries is accessing outpatient mental health treatment, but that those who do are using care more frequently. Given that these declines persist despite adjustment, it is possible that over time, the cohort of identified gender minority beneficiaries includes a lower proportion of individuals with severe mental health needs, that policies (including those in Medicare) to increase access to mental health care by reducing out of pocket costs are affecting gender minority beneficiaries differentially, or that gender minority individuals are more likely to seek support in other ways (i.e., support groups).

Access to mental health care, even under conditions of ostensible mental health parity, can be complicated further by issues that are difficult to regulate, such as narrow provider networks for those offering mental health services.38 Considering that 50% of transgender patients in national surveys report that they need to educate their providers about gender minority care,27 the “effective” network of mental health care providers prepared to provide high-quality mental health care to gender minority patients is likely much smaller than that available to the broader population. In focus groups of transgender women living with HIV who also had used mental health treatment, participants “discussed the need for more readily available mental health services aside from psychotropic medications,”39 in particular, because there was a perception that medications were being used more often because they were “more readily available than therapy, which participants viewed as a problem.”39 Whether gender minority Medicare beneficiaries have more difficulty than other Medicare beneficiaries in finding mental health care providers who meet their treatment needs may be an area for further study.

The decline in the prevalence of inpatient visits for Medicare beneficiaries overall, with faster declines for gender minority beneficiaries, was consistent with our hypothesis. The general decline was also consistent with overall health system reform efforts over this time period to reduce the most expensive types of health care utilization through efforts such as integrating physical and behavioral health care,40 implementing value-based payment contracts and bundled payments in Medicare and Medicaid,41–47 including for mental health care increasingly,48 and reducing out of pocket costs for outpatient services and medications (such as through the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act in Medicare49–51). The gender minority beneficiaries we identified, who tend to use more mental health services overall, may be affected more by such policy changes. However, the rise in the number of inpatient visits among identified gender minority beneficiaries with at least one inpatient visit suggests that some identified beneficiaries at highest risk may be experiencing greater emergency need.

We observed rising psychotropic prescription medication prevalence among the aged gender minority beneficiaries that outpaced the rise for other beneficiaries, consistent with our hypothesis. Our results parallel general trends in Medicare showing a declining share of Medicare spending in hospital inpatient services and physician payments, whereas outpatient prescription drug spending has increased,52 including for psychotropic medications.53–55 These findings would support calls to increase the education of psychiatrists and primary care providers in caring specifically for transgender and gender non-binary patients.56 A 2009–2010 survey of all medical schools in the United States and Canada found that few (if any) of the average of 5 hours per year of training devoted to LGBT-specific concerns covered transgender topics.57 Yet, these same providers may face increased demand to prescribe psychotropic medications safely and effectively to gender minority beneficiaries, especially those age 65 years or older. Additional research may be needed to support these providers in knowledge of how psychotropic drugs may interact with some gender-affirming care (such as hormones), in a population that is already vulnerable to high rates of polypharmacy and comorbidities, and increased serious side effects from psychotropic drugs due to aging-related factors.58

Limitations

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services diagnosis-based gender minority algorithm does not differentiate across the spectrum of gender identities and may be more likely to miss gender minority individuals who do not experience dysphoria, non-binary or gender fluid individuals, and those who do not have access to or who simply do not want gender-affirming medical care such as hormone therapy. Furthermore, health care providers sometimes do not use gender dysphoria-related ICD-9 codes to avoid potential for claims being denied. We excluded gender-minority-related ICD-9 codes from mental health care use measures. However, given that individuals receiving medical assistance with transitions are often required to receive mental health screenings to begin some types of care, it is likely that gender minority Medicare beneficiaries captured through this algorithm are more likely to have mental health conditions diagnosed, and have contact with mental health care services than other beneficiaries who do not routinely require similar evaluations.59,60 Another limitation is that gender minority Medicare beneficiaries may receive gender-affirming medical care (e.g., hormones) entirely at clinics that do not bill Medicare, in which case, they may be less likely to be identified using this algorithm.

The relatively smaller sample sizes for gender minority beneficiaries may mean that changes to mental health care utilization among fewer individuals more readily influence trends in mean changes for those analytic cohorts. Behavioral health diagnoses in claims data almost certainly underestimate true need for mental health treatment, and do not capture severity of diagnosed conditions. These analyses also exclude substance use claims. We did not have information about supplemental Medicare coverage, which may affect some health care utilization.

Conclusions

From 2009 to 2014, for identified aged gender minority beneficiaries, relative to other beneficiaries, the proportion using psychotropic medications increased, outpatient visits decreased slightly, and any inpatient use decreased. In the disabled cohort, a higher proportion of gender minority beneficiaries had psychotropic medication prescriptions (even as the gap between them and other beneficiaries narrowed slightly), whereas proportions with any inpatient or outpatient visits fell faster compared to other beneficiaries in this time period. Overall, these patterns suggest that psychotropic medications may be used increasingly to address the mental health needs of gender minority Medicare beneficiaries, relative to other beneficiaries with comparable rates of mental health diagnoses. These patterns may represent increased access to lower-cost mental health treatment. However, they also indicate the need for increased research and more provider training in the safe and effective administration of psychotropic medications alongside gender-affirming treatments, such as hormones and/or surgeries (including for primary care providers and other nonspecialists, who may be prescribing psychotropic medications). For aging gender minority individuals, research and provider training should also address psychotropic medication prescribing alongside common aging-related medications, given the concern for side effects and adverse outcomes from polypharmacy.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Ye Wang, PhD, for her initial contributions to the Medicare data analyses. The research in this article was supported by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities R03 MD012334-01 (Principal Investigator: A.M.P.), “Identifying Gender Minority Health Disparities in Medicare Claims Data,” as well as the Health Equity Data Access Program, Office of Minority Health, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) (B.L.C., Principal Investigator).

Disclaimer

Early results from this work were presented at the 7th Conference of the American Society of Health Economists (ASHEcon) on June 12, 2018 in Atlanta, GA. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of CMS or the United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Veldhuis CB, Drabble L, Riggle ED, et al. : “We won't go back into the closet now without one hell of a fight”: Effects of the 2016 presidential election on sexual minority women's and gender minorities' stigma-related concerns. Sex Res Soc Policy 2018;15:12–24 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stroumsa D: The state of transgender health care: Policy, law, and medical frameworks. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e31–e38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meerwijk EL, Sevelius JM: Transgender population size in the United States: A meta-regression of population-based probability samples. Am J Public Health 2017;107:e1–e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daniel H, Butkus R, Health and Public Policy Committee of American College of Physicians: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health disparities: Executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:135–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dubin SN, Nolan IT, Streed CG Jr, et al. : Transgender health care: Improving medical students' and residents' training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract 2018;9:377–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Human Rights Campaign: A history of federal non-discrimination legislation (93rd–114th Congress). 2016. Available at https://hrc.org/resources/a-history-of-federal-non-discrimination-legislation Accessed May30, 2018

- 7. Green J: Transsexual surgery may be covered by Medicare. LGBT Health 2014;1:256–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities: The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shankle MD, Maxwell CA, Katzman ES, Landers S: An invisible population: Older lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Clin Res Reg Affairs 2003;20:159–182 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Munro L, Travers R, Woodford MR: Overlooked and invisible: Everyday experiences of microaggressions for LGBTQ adolescents. J Homosex 2019;66:1439–1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burgess D, Lee R, Tran A, van Ryn M: Effects of perceived discrimination on mental health and mental health services utilization among gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender persons. J LGBT Health Res 2007;3:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jaffee KD, Shires DA, Stroumsa D: Discrimination and delayed health care among transgender women and men: Implications for improving medical education and health care delivery. Med Care 2016;54:1010–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. House AS, van Horn E, Coppeans C, Stepleman LM: Interpersonal trauma and discriminatory events as predictors of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury in gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender persons. Traumatology 2011;17:75–85 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seelman KL, Colón-Diaz MJP, LeCroix RH, et al. : Transgender noninclusive healthcare and delaying care because of fear: Connections to general health and mental health among transgender adults. Transgend Health 2017;2:17–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Romanelli M, Lu W, Lindsey MA: Examining mechanisms and moderators of the relationship between discriminatory health care encounters and attempted suicide among U.S. transgender help-seekers. Adm Policy Ment Health 2018;45:831–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Deutsch MB, Massarella C: Reported emergency department avoidance, use, and experiences of transgender persons in Ontario, Canada: Results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. Ann Emerg Med 2014;63:713–720.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crissman HP, Berger MB, Graham LF, Dalton VK: Transgender demographics: A household probability sample of US adults, 2014. Am J Public Health 2017;107:213–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Proctor K, Haffer SC, Ewald E, et al. : Identifying the transgender population in the Medicare program. Transgend Health 2016;1:250–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blosnich JR, Marsiglio MC, Dichter ME, et al. : Impact of social determinants of health on medical conditions among transgender veterans. Am J Prev Med 2017;52:491–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perez-Brumer A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Oldenburg CE, Bockting W: Individual- and structural-level risk factors for suicide attempts among transgender adults. Behav Med 2015;41:164–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reisner SL, Bailey Z, Sevelius J: Racial/ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the U.S. Women Health 2014;54:750–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22. Meyer IH, Brown TN, Herman JL, et al. : Demographic characteristics and health status of transgender adults in select US regions: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2014. Am J Public Health 2017;107:582–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clark BA, Veale JF, Greyson D, Saewyc E: Primary care access and foregone care: A survey of transgender adolescents and young adults. Fam Pract 2017:35;302–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feldman J, Bockting W: Transgender health. Minn Med 2003;86:25–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Advancing LGBT Health and Well-Being: 2016 Report of the HHS LGBT Policy Coordinating Committee. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Progovac AM, Cook BL, Mullin BO, et al. : Identifying gender minority patients' health and health care needs in administrative claims data. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:413–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, et al. : Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stotzer RL: Violence against transgender people: A review of United States data. Aggress Violent Behav 2009;14:170–179 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Streed CG , Jr, McCarthy EP, Haas JS: Association between gender minority status and self-reported physical and mental health in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1210–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reisner SL, Vetters R, Leclerc M, et al. : Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: A matched retrospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:274–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dragon CN, Guerino P, Ewald E, et al. : Transgender Medicare beneficiaries and chronic conditions: Exploring fee-for-service claims data. LGBT Health 2017;4:404–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care: In: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Chronic conditions data warehouse. 2014. Available at https://ccwdata.org/web/guest/home Accessed October15, 2018

- 34. Cook BL, Zuvekas SH, Chen J, et al. : Assessing the individual, neighborhood, and policy predictors of disparities in mental health care. Med Car Res Rev 2017;74:404–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Busch AB, Huskamp HA, McWilliams JM: Early efforts by Medicare Accountable Care Organizations have limited effect on mental illness care and management. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:1247–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Albrecht JS, Mullins DC, Smith GS, Rao V: Psychotropic medication use among Medicare beneficiaries following traumatic brain injury. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;25:415–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McGuire TG, Alegria M, Cook BL, et al. : Implementing the Institute of Medicine definition of disparities: An application to mental health care. Health Serv Res 2006;41:1979–2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McGuire TG: Achieving mental health care parity might require changes in payments and competition. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:1029–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sevelius JM, Patouhas E, Keatley JG, Johnson MO: Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann Behav Med 2014;47:5–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O'Donnell AN, Williams M, Kilbourne AM: Overcoming roadblocks: Current and emerging reimbursement strategies for integrated mental health services in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1667–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hussey PS, Mulcahy AW, Schnyer C, Schneider EC: Closing the quality gap: Revisiting the state of the science (vol. 1: Bundled payment: Effects on health care spending and quality). Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2012(208.1):1–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Baseman S, Boccuti C, Moon M, et al. : Payment and Delivery System Reform in Medicare: A Primer on Medical Homes, Accountable Care Organizations, and Bundled Payments. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pham HH, Pilotte J, Rajkumar R, et al. : Medicare's vision for delivery-system reform—the role of ACOs. N Engl J Med 2015;373:987–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gusmano MK, Thompson FJ: An examination of Medicaid delivery system reform incentive payment initiatives under way in six states. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:1162–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Crawford M, McGinnis T, Auerbach J, Golden K: Population Health in Medicaid Delivery System Reforms. New York: Milbank Memorial Fund, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Joynt Maddox KE, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM: Evaluation of Medicare's bundled payments initiative for medical conditions. N Engl J Med 2018;379:260–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bhatt SP, Wells JM, Iyer AS, et al. : Results of a Medicare bundled payments for care improvement initiative for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017;14:643–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mauri A, Harbin H, Unützer J, et al. : Payment Reform and Opportunities for Behavioral Health: Alternative Payment Model Examples. Thomas Scattergood Behavioral Health Foundation and Peg's Foundation, 2017. Available at https://chp-wp-uploads.s3.amazonaws.com/www.thekennedyforum.org/uploads/2017/09/Payment-Reform-and-Opportunities-for-Behavioral-Health-Alternative-Payment-Model-Examples-Final.pdf Accessed October15, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 49. 110th Congress: Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008. Public Law 110–275, 122 Stat 2494, 2008

- 50. LeMasurier JD, Edgar B: MIPPA: First broad changes to Medicare part D plan operations. Am Health Drug Benefits 2009;2:111–118 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Walker ER, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, Druss GB: Insurance status, use of mental health services, and unmet need for mental health care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:578–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cubanski J, Neuman T: The Facts on Medicare Spending and Financing. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zuvekas SH: Trends in mental health services use and spending, 1987–1996. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:214–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zuvekas SH, Meyerhoefer CD: State variations in the out-of-pocket spending burden for outpatient mental health treatment. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:713–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zuvekas SH: Prescription drugs and the changing patterns of treatment for mental disorders, 1996–2001. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:195–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kosman KA, AhnAllen CG, Fromson JA: A call to action: The need for integration of transgender topics in psychiatry education. Acad Psychiatry 2019;43:82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. : Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender–related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA 2011;306:971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lindsey PL: Psychotropic medication use among older adults: What all nurses need to know. J Gerontol Nurs 2009;35:28–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Streed CG, Jr, Arroyo H, Goldstein Z: Gender minority patients' mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Progovac AM, Cook BL, McDowell A: Gender minority patients: The authors reply. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]