Abstract

Background:

Whether the efficient heat-generating mechanism of microwave ablation (MWA) is comparable with resection (RES) in treating hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains unclear.

Methods:

This retrospective cohort study comprised 126 and 1183 patients with HCC meeting the Milan criteria who received MWA or RES between 2002 and 2017. We compared 5-year overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) using both propensity-score matching (PSM) and inverse-probability-of-treatment-weighting (IPW) analysis and investigated the prognostic factors with multivariate Cox analysis.

Results:

After PSM (1:2), although MWA (n = 116) offered decreased 5-year RFS (30.6% versus 57.5%, p < 0.001) compared with RES (n = 212), both treatments provided similar 5-year OS (82.2% versus 80.5%, p = 0.360) because most patients with intrahepatic recurrence remained eligible for repeat treatments; similar results were found in the IPW analysis. Additionally, the comparable efficacy of MWA and RES was consistent across all subgroups: those with solitary HCC ⩽ 3.0 cm or >3.0 cm, or multifocal HCCs within the Milan criteria, patients with liver function of albumin–bilirubin grade 1 or 2, and older (⩾60 years) or younger (<60 years) patients. Multivariate Cox analysis confirmed that no difference was seen between MWA and RES in OS (hazard ratio = 0.85; p = 0.581) in the overall population; similar results were obtained in the propensity-score-matched and IPW cohorts.

Conclusions:

Compared with RES, MWA offered worse RFS for HCC within the Milan criteria; however, both treatments provided equivalent long-term OS because most patients with intrahepatic recurrence remained eligible for repeat treatments.

Keywords: hepatectomy, liver cancer, local ablation, outcomes

Introduction

Liver resection (RES) and local ablation are the two primary curative treatments for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).1,2 The latest clinical practice guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend radiofrequency ablation (RFA) as the standard ablation strategy for patients with early-stage HCC that is not amenable to RES.1,2 Moreover, the EASL notes that microwave ablation (MWA) shows promising performance in terms of local tumour recurrence control and survival, while the AASLD calls for future research focused on the comparative effectiveness of ablative strategies other than RFA, such as MWA.1,2 Our previous study comparing MWA and RFA in treating HCC within the Milan criteria also suggests MWA over RFA for its better long-term overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS).3 Thus, given the different heat-generation mechanism of MWA, we aimed to determine whether MWA would be comparable with RES in treating early-stage HCC. However, no prospective studies have compared the efficacy of MWA with the gold standard treatment of RES. Here, we compared the efficacy of MWA and RES for HCC meeting the Milan criteria using a retrospective cohort comprising a total of 1309 patients. Two complementary propensity-score analyses were employed to reduce potential confounding bias at baseline and to improve intergroup comparability.

Methods

Patients

All primary HCC patients who were initially treated with RES or percutaneous MWA with curative intent from January 2002 to January 2017 at the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre were identified. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) tumours within the Milan criteria4 (solitary HCC ⩽ 5.0 cm in diameter, or two to three HCC tumours, each ⩽3.0 cm in diameter); (b) no radiological evidence of major portal/hepatic vein branch invasion; (c) no extrahepatic metastasis; and (d) Child–Pugh A or B disease. Patients were excluded based on the following exclusion criteria: (a) patients did not achieve R0 resection for RES (R0 resection was defined as a negative surgical margin observed microscopically or macroscopically); or (b) patients did not achieve complete ablation after MWA (complete ablation was defined as no nodular or irregular enhancement within or adjacent to the ablation zone during the arterial phase on the first contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed approximately 1 month after ablation). Finally, a total of 1309 patients were enrolled, including 1183 patients who received RES and 126 patients who received MWA. A multidisciplinary team of surgeons, physicians and interventional radiologists specializing in the management of hepato-pancreato-biliary diseases evaluated the diagnosis of HCC and determined the final therapeutic regimen. The diagnosis of HCC was confirmed according to the HCC management guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) or the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).5,6 The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and obtained approval from the Ethics Committee of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre (no. B2018-044-01), and the need to obtain informed consent was waived.

Treatment and follow up

The MWA and RES procedures have been previously described.3,7 The first follow-up visit was performed approximately 1 month after treatment; then, patients were followed up every 3 months in the first 2 years and every 3–6 months thereafter until death or dropout. Each follow up consisted of a physical examination, serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) analysis and at least one imaging examination (abdominal contrast-enhanced CT or MRI). Treatment strategies for recurrence were according to the clinical practice guidelines from the EASL by a multidisciplinary team. In brief, salvage treatment was given to patients with recurrence whenever possible. Repeated ablation or resection was the first choice for patients with recurrent tumours meeting the BCLC 0/A stage criteria, while transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and other nonradical treatments were appropriately offered for more advanced HCC.

Subgroup analyses

Our primary interest was to perform a subgroup analysis of patients with solitary small HCC (⩽3.0 cm); however, we also investigated subgroups of medium-sized HCC (3.0–5.0 cm) and multifocal HCCs within the Milan criteria. Furthermore, to confirm that the treatment efficacy of MWA and RES in treating HCC was independent of age,8 we separated the study population into two prespecified groups as follows: elderly patients (⩾60 years) and younger patients (<60 years). Finally, since most of the patients had Child–Pugh A disease in the present study (RES: 97.0%; MWA: 78.6%), and the newly developed albumin–bilirubin (ALBI) grade can reveal two classes with clearly different prognoses in patients with Child–Pugh A disease,9 the treatment efficacy of MWA and RES was further compared between patients with liver function of ALBI grade 1 and those with ALBI grade 2.

Propensity-score matching

To reduce patient selection bias, we used the propensity-score matching (PSM) method because it could generate a tangible ‘control’ (RES) group that had characteristics similar to those of the ‘intervention’ (MWA) group. Clinically important factors or variables associated with survival as indicated in univariate Cox models (p < 0.10) were used to calculate propensity scores.10 Thus, the covariables used to build the propensity score were tumour number, tumour size, age, sex, white blood cell count (WBC), red blood cell count (RBC), platelet counts (PLTs), serum albumin level (ALB), total bilirubin level (TBIL), alanine aminotransferase level (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase level (AST). Then, the propensity for MWA was estimated by a logistic regression model, with the response variable being MWA (yes/no). Since the sample size was greatly varied between the MWA and RES groups (126 versus 1183), a one-to-two nearest-neighbour matching algorithm with an optimal calliper of 0.2 and no replacement was used to decrease the sampling variability of the estimated treatment effect.11,12 The MatchIt R package (version 3.0.2; the CRAN package repository, Vienna, Austria) was used in PSM analyses.

Inverse-probability-of-treatment-weighting analysis

Although the PSM analysis was easy to explain, it had a side effect of throwing away large numbers of cases during the matching procedure. Hence, to validate the robustness of the results from the PSM analysis, we further applied inverse-probability-of-treatment weighting (IPW) to create pseudo cohorts that did not discard cases but weighted the full dataset.13,14 The propensity scores calculated from the PSM procedure were further used for case–weight estimation. Weights for patients treated with MWA were the inverse of the propensity score, and weights for patients treated with RES were the inverse of 1 minus the propensity score. Then, the IPW process created two pseudo cohorts that received MWA or RES. To preserve the sample size of the original cohorts in the pseudo cohorts and to avoid an increase in type I error rate, we stabilized the weights by multiplying each by the marginal probability of the treatment without considering which covariates were used.15,16 The IPW R package (version 1.0-11; the CRAN package repository, Vienna, Austria) and IPW survival R package (version 0.5; the CRAN package repository, Vienna, Austria) were used in the IPW analyses.17,18

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint of the study was OS (the time from the date of treatment to the date of death), and the secondary endpoint was RFS (the period after curative treatment when no disease was detected). Continuous and ordinal variables were assessed by the Mann–Whitney test; categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test (Fisher’s exact test if necessary). The weighted Mann–Whitney test and weighted chi-squared test were applied to compare continuous or categorical variables, respectively, in the pseudo cohorts generated by the IPW analyses. The survey R package (version 3.32; the CRAN package repository, Vienna, Austria) was used to calculate the effect sizes of covariates19 and to describe the differences in the baseline characteristics: values < 0.1 indicate very small differences; between 0.1 and 0.3 indicate small differences, between 0.3 and 0.5 indicate moderate differences, and >0.5 indicate large differences.20 Survival curves are depicted using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared by the log-rank test. Treatment modality and variables used to calculate propensity scores were introduced into the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to infer the effect of using MWA versus RES. In the pseudo cohorts generated in IPW analyses, Cox proportional hazard regression models, survival curves and log-rank tests were all adjusted based on inverse probability weights.21–23 All tests were two-tailed, and p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.5.0 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patients

During the study period, 126 patients received MWA, and 1183 patients received RES as the initial treatment for HCC meeting the Milan criteria. The median follow-up time was 36.8 months in the MWA group (range 1–115 months) and 37.8 months in the RES group (range 1–120 months). A comparison of the baseline clinical and laboratory parameters in the original cohort showed significantly more patients presenting with multifocal HCCs, smaller tumours and more advanced liver disease in the MWA group than in the RES group (all p values <0.05; Table 1). The PSM procedure (2:1 matching) generated two new cohorts of 212 and 116 patients in the RES and MWA groups, respectively, while the IPW procedure created two new pseudo cohorts of 1201 and 107 patients in the RES and MWA groups, respectively. All variables (especially tumour number, tumour size and liver function) were well balanced after PSM and IPW adjustment (Table 1 shows that p values were usually >0.05; online Supplementary Figure 1 shows that effect sizes were usually <0.1, and all were <0.3).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by treatment cohort.

| Variable | Overall population |

Propensity-score-matched cohort (2:1) |

Inverse-probability-of-treatment- weighted cohort |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RES (1183) | MWA (126) | p | RES (212) | MWA (116) | p | RES (1201) | MWA (107) | p | |

| Male (%) | 87.5 | 90.5 | 0.407 | 86.8 | 89.7 | 0.561 | 87.8 | 80.7 | 0.039 |

| Age (years) | 51 (17) | 54 (15) | 0.071 | 54 (16) | 54 (15) | 0.850 | 52 (17) | 54 (17) | 0.542 |

| Tumour number (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 93.9 | 78.6 | <0.001 | 80.7 | 81.0 | 1.000 | 90.5 | 91.3 | 0.869 |

| 2 | 5.7 | 14.3 | <0.001 | 17.9 | 13.8 | 0.419 | 8.4 | 6.9 | 0.643 |

| 3 | 0.4 | 7.1 | <0.001 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 0.072 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.347 |

| Tumour size (cm) | 3.1 (1.5) | 2.3 (1.2) | <0.001 | 2.2 (1) | 2.3 (1.2) | 0.615 | 3.0 (1.8) | 2.9 (1.8) | 0.234 |

| AFP (ng/ml) | 46 (504) | 63 (271) | 0.778 | 52 (328) | 60 (275) | 0.978 | 48.7 (477) | 62.8 (443) | 0.649 |

| Aetiology (%) | 1.000 | 0.324 | 0.056 | ||||||

| HBV/HCV | 92.5/1.2 | 89.7/4.0 | 95.3/0.9 | 88.8/4.3 | 92.4/1.7 | 86.8/2.3 | |||

| Other | 6.3 | 6.3 | 3.8 | 6.9 | 5.9 | 10.8 | |||

| Cirrhosis (%) | 77.1 | 80.2 | 0.503 | 86.3 | 78.4 | 0.092 | 78.5 | 79.9 | 0.937 |

| PLT (× 109) | 156 (74) | 106 (83) | <0.001 | 122 (83) | 109 (85) | 0.065 | 152 (78) | 135 (79.5) | 0.033 |

| RBC (× 109) | 4.7 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.8) | 0.005 | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.8) | 0.794 | 4.7 (0.7) | 4.7 (0.7) | 0.702 |

| WBC (× 109) | 5.8 (2.1) | 5.2 (0.9) | <0.001 | 5.3 (2.0) | 5.3 (2.0) | 0.861 | 5.7 (1.2) | 5.8 (2.0) | 0.575 |

| ALB (g/l) | 43.1 (4.7) | 40.6 (6.7) | <0.001 | 42.3 (5.4) | 41.3 (5.9) | 0.028 | 42.9 (4.8) | 41.8 (2.8) | 0.001 |

| ALT (U/l) | 34.8 (24.9) | 38.3 (26.8) | 0.010 | 38.5 (29.2) | 38.0 (27.7) | 0.548 | 35.5 (25.8) | 32.0 (19.3) | 0.662 |

| AST (U/l) | 30.0 (15.2) | 36.8 (25.0) | <0.001 | 34.3 (19.8) | 35.9 (24.7) | 0.383 | 30.9 (17.4) | 32.5 (16.7) | 0.621 |

| TBIL (μmol/l) | 13.5 (6.6) | 17.1 (11.6) | <0.001 | 14.7 (9.6) | 17.0 (10.0) | 0.102 | 13.7 (7.1) | 13.7 (7.3) | 0.043 |

| PT (s) | 11.7 (1.3) | 12.7 (2.6) | <0.001 | 12.1 (1.8) | 12.6 (2.3) | 0.001 | 11.8 (1.3) | 12.2 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| C–P grade (%) | <0.001 | 0.051 | 0.018 | ||||||

| A | 97.0 | 78.6 | 90.1 | 81.9 | 94.8 | 87.8 | |||

| B | 3.0 | 21.4 | 9.9 | 18.1 | 5.2 | 11.2 | |||

Continuous variables are reported as medians (interquartile range) and were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and were compared using Pearson’s Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALB, albumin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; C–P, Child–Pugh; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MWA, microwave ablation; PLT, platelets; PT, prothrombin time; RBC, red blood cell count; RES, resection; TBIL, total bilirubin; WBC, white blood cell count.

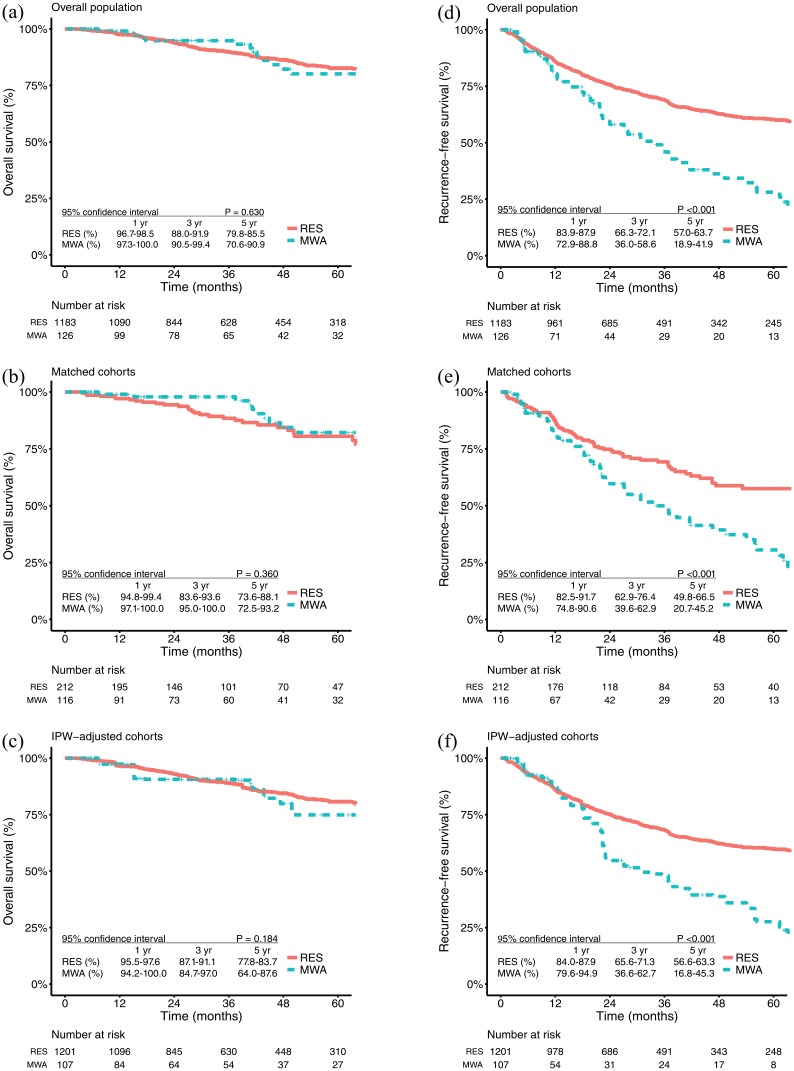

Overall survival

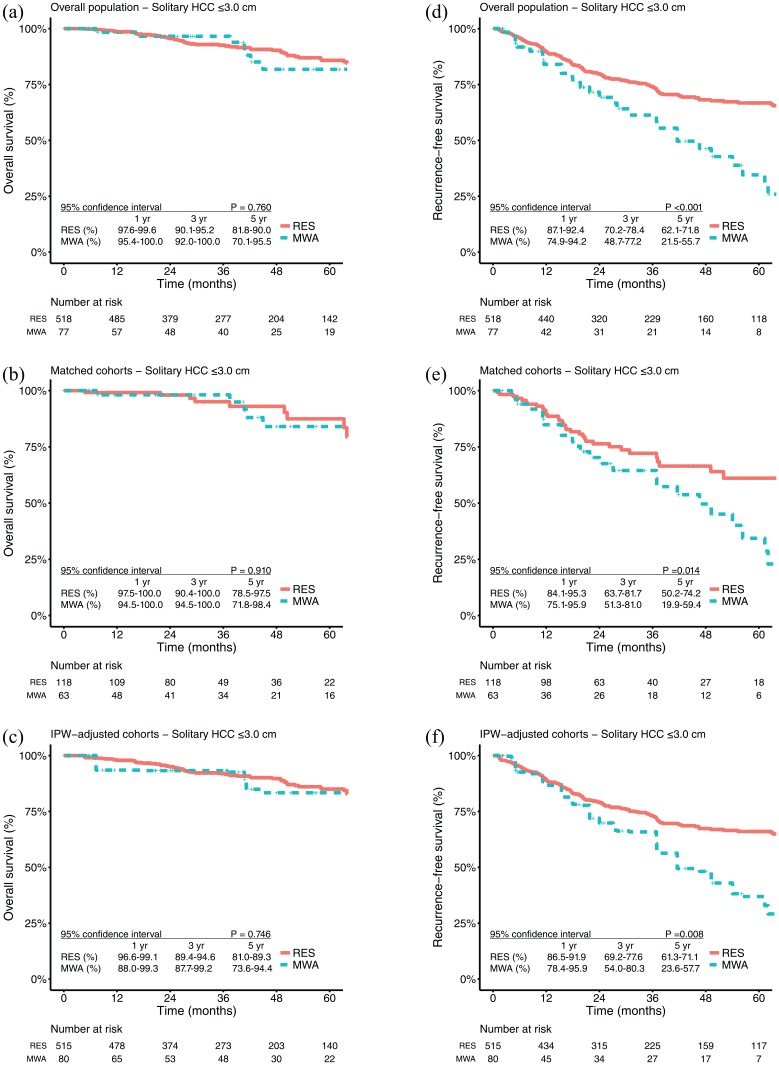

A total of 17 (17/126, 13.5%) patients in the MWA group and 154 (154/1183, 13.0%) patients in the RES group died (p = 0.991). The 1-, 3- and 5-year OS rates were 99.1%, 94.8%, and 80.1% in the MWA group and 97.6%, 89.9%, and 82.6% in the RES group, respectively [p = 0.630; Figure 1(a)]. For patients with solitary HCC ⩽ 3.0 cm, the OS rates at 1, 3 and 5 years were 98.4%, 96.6%, and 81.8% in the MWA group and 98.6%, 92.6%, and 85.8% in the RES group, respectively [p = 0.170; Figure 2(a)]. After PSM, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 99.0%, 97.9%, and 82.2% in the MWA group and 97.1%, 88.4%, and 80.5% in the RES group, respectively [p = 0.360; Figure 1(b)]. For patients with solitary HCC ⩽ 3.0 cm, the OS rates at 1, 3 and 5 years were 98.1%, 98.1%, and 84.0% in the MWA group and 99.1%, 95.1%, and 87.5% in the RES group, respectively [p = 0.910; Figure 2(b)]. Similar results were also found in the IPW-adjusted cohorts [Figures 1(c) and 2(c)].

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing 5-year overall survival and recurrence-free survival among patients who underwent microwave ablation or resection.

IPW, inverse-probability-of-treatment weighting; MWA, microwave ablation; OS, overall survival; RES, resection; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing 5-year overall survival and recurrence-free survival among patients with solitary HCC ⩽ 3 cm who underwent microwave ablation or resection.

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IPW, inverse-probability-of-treatment weighting; MWA, microwave ablation; OS, overall survival; RES, resection; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

OS in the (a) overall population, (b) propensity-score-matched cohorts, and (c) IPW-adjusted cohorts; RFS in the (d) overall population, (e) propensity-score-matched cohorts, and (f) IPW-adjusted cohorts.

Recurrence-free survival

A total of 64 (64/126, 50.8%) patients in the MWA group and 381 (381/1183, 32.2%) patients in the RES group had tumour recurrence (p < 0.001). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates were 80.4%, 46.0%, and 28.1% in the MWA group and 85.9%, 69.1%, and 60.3% in the RES group, respectively [p < 0.001; Figure 1(d)]. For patients with solitary HCC ⩽ 3.0 cm, the RFS rates at 1, 3 and 5 years were 84.0%, 61.3%, and 34.6% in the MWA group and 89.7%, 74.2%, and 66.8% in the RES group, respectively [p < 0.001; Figure 2(d)]. After PSM, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates were 82.3%, 49.9%, and 30.6% in the MWA group and 87.0%, 69.3%, and 57.5% in the RES group, respectively [p < 0.00; Figure 1(e)]. For patients with solitary HCC ⩽ 3.0 cm, the RFS rates at 1, 3 and 5 years were 84.8%, 64.5%, and 34.4% in the MWA group and 89.5%, 72.1%, and 61.1% in the RES group, respectively [p = 0.014; Figure 2(e)]. Similar results were also found in the IPW-adjusted cohorts [Figures 1(f) and 2(f)].

OS in the (a) overall population, (b) propensity-score-matched cohorts, and (c) IPW-adjusted cohorts; RFS in the (d) overall population, (e) propensity-score-matched cohorts, and (f) IPW-adjusted cohorts.

Prognostic factors associated with overall survival and recurrence-free survival

Multivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed that MWA was not an independent risk factor for OS [MWA versus RES, hazard ratio (HR) = 0.85; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.48–1.50, p = 0.581] but indicated that MWA was associated with worse RFS (MWA versus RES, HR = 1.97; 95% CI, 1.45–2.66, p < 0.001; Table 2). For subgroups with solitary HCC ⩽ 3 cm, MWA was also not an independent risk factor for OS (MWA versus RES, HR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.42–2.22, p = 0.940) but it indicated an assocition with worse RFS (MWA versus RES, HR = 2.04; 95% CI, 1.31–3.17, p = 0.001). Additionally, similar results were found in the multivariate Cox models for PSM- and IPW-adjusted cohorts (Table 3).

Table 2.

Prognostic factors of overall survival and recurrence-free survival in the original cohort.

| Variable | Overall survival |

Recurrence-free survival |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age (⩾60 years) | 1.01 (0.99–1.00) | 0.255 | 1.23 (1.00–1.50) | 0.043 | 1.16 (0.94–1.43) | 0.169 | ||

| Sex (male) | 1.25 (0.75–2.10) | 0.388 | 1.50 (1.10–2.10) | 0.014 | 1.48 (1.06–2.07) | 0.023 | ||

| MWA/RES | 1.13 (0.69–1.90) | 0.630 | 0.85 (0.48–1.50) | 0.581 | 2.35 (1.80–3.10) | <0.001 | 1.97 (1.45–2.66) | <0.001 |

| Tumour size (per cm) | 1.18 (1.00–1.40) | 0.022 | 1.21 (1.04–1.41) | 0.014 | 1.06 (0.97–1.20) | 0.170 | 1.16 (1.06–1.28) | 0.002 |

| Tumour number | 1.27 (0.83–1.90) | 0.273 | 1.40 (0.89–2.20) | 0.150 | 1.88 (1.50–2.30) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.29–2.08) | <0.001 |

| WBC (< 4.0 × 109/l) | 1.64 (1.00–2.60) | 0.031 | 1.30 (0.80–2.11) | 0.289 | 1.43 (1.10–1.90) | 0.015 | 1.22 (0.90–1.67) | 0.204 |

| RBC (< 4.3 × 109/l) | 1.42 (1.00–2.00) | 0.037 | 1.26 (0.89–1.79) | 0.199 | 1.27 (1.00–1.60) | 0.027 | 1.16 (0.92–1.46) | 0.219 |

| PLT (< 100 × 109/l) | 1.59 (1.10–2.30) | 0.009 | 1.30 (0.88–1.93) | 0.184 | 1.45 (1.20–1.80) | 0.001 | 1.07 (0.83–1.38) | 0.594 |

| ALT ( > 50 U/l) | 1.53 (1.10–2.10) | 0.005 | 1.32 (0.94–1.86) | 0.108 | 1.39 (1.20–1.70) | <0.001 | 1.27 (0.79–1.03) | 0.028 |

| AST (> 40 U/l) | 1.75 (1.20–2.50) | 0.001 | 1.32 (0.89–1.95) | 0.172 | 1.47 (1.20–1.80) | <0.001 | 1.09 (0.84–1.40) | 0.529 |

| ALB (< 35 g/l) | 1.94 (0.99–3.80) | 0.054 | 1.46 (0.72–2.98) | 0.299 | 1.72 (1.10–2.70) | 0.015 | 1.13 (0.70–1.81) | 0.625 |

| TBIL (> 17.1 μmol/l) | 1.36 (0.99–1.90) | 0.060 | 1.22 (0.87–1.70) | 0.250 | 1.16 (0.94–1.40) | 0.167 | ||

| PT (prolongation > 3 s) | 1.33 (0.33–5.40) | 0.689 | 1.02 (0.38–2.70) | 0.974 | ||||

| Viral hepatitis | 1.22 (0.54–2.70) | 0.640 | 1.27 (0.79–2.00) | 0.317 | ||||

| Cirrhosis | 0.98 (0.69–1.40) | 0.886 | 1.31 (1.00–1.60) | 0.021 | 1.14 (0.90–1.45) | 0.270 | ||

| AFP (> 200 ng/mL) | 1.16 (0.85–1.60) | 0.343 | 0.92 (0.75–1.10) | 0.375 | ||||

Treatment option, tumour number, tumour size and variables with p value <0.10 in the univariate Cox analyses were retained for the multivariate Cox analysis.

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALB, albumin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MWA, microwave ablation; PLT, platelet; PT, prothrombin time; RES, resection; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell; TBIL, total bilirubin.

Table 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios of MWA versus RES from multivariate Cox regression models in propensity-score-matched and inverse-probability-of-treatment-weighted cohorts.

| Variable (MWA/RES) |

Propensity-score-matched cohort (2:1) |

Inverse-probability-of-treatment-weighted cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | Recurrence-free survival | Overall survival | Recurrence-free survival | |||||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Overall | 0.64 (0.33–1.27) | 0.203 | 2.12 (1.48–3.02) | <0.001 | 1.31 (0.82–2.09) | 0.258 | 2.14 (1.56–2.94) | <0.001 |

| Solitary HCC ⩽3 cm | 1.06 (0.36–3.06) | 0.916 | 1.80 (1.03–3.15) | 0.038 | 1.27 (0.65–2.47) | 0.481 | 1.98 (1.33–2.93) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; MWA, microwave ablation; RES, resection.

Subgroup analyses

In addition to the subgroup analysis of solitary HCC ⩽ 3 cm, subgroup analyses according to clinically relevant variables that we found most interesting were also conducted. Both treatments provided equivalent long-term OS across all patient subgroups as follows (online Supplementary Figures 2–7): patients with solitary, medium-sized HCC (>3.0 cm) or multifocal HCCs within the Milan criteria, patients with liver function of ALBI grade 1 or 2, and older (⩾60 years) or younger (<60 years) patients.

Procedure-related complications

Adverse events occurring after treatment are presented in Table 4. In the PSM cohort, a higher rate of overall adverse events was observed for RES (78.7% versus 71.6%, p = 0.013). Notably, more patients in the RES group had diarrhoea (14.6% versus 1.7%, p < 0.001) and underwent a blood transfusion (20.3% versus 4.3%, p < 0.001) in the PSM cohort.

Table 4.

Procedure-related complications.

| Variable | Overall population |

Propensity-score-matched cohort (2:1) |

Inverse-probability-of-treatment- weighted cohort |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RES (1183) | MWA (126) | p | RES (1183) | MWA (126) | p | RES (1201) | MWA (107) | p | |

| Morbidity | |||||||||

| Total | 808 (68.3) | 87 (69.0) | 0.944 | 167 (78.8) | 83 (71.6) | 0.013 | 853 (71.0) | 83 (77.6) | 0.184 |

| Severe | 27 (2.3) | 3 (2.4) | 1.000 | 5 (2.4) | 3 (2.6) | 1.000 | 27 (2.2) | 3 (2.8) | 0.731 |

| Minor | 779 (65.9) | 84 (66.7) | 0.185 | 162 (76.4) | 80 (69.0) | 0.182 | 826 (68.8) | 80 (74.8) | 0.239 |

| Grade | |||||||||

| 1 | 628 (53.1) | 78 (61.9) | 116 (54.7) | 75 (64.7) | 639 (53.2) | 77 (72.6) | |||

| 2 | 151 (12.8) | 6 (4.8) | 46 (21.7) | 5 (4.3) | 187 (15.6) | 3 (2.8) | |||

| 3 | 23 (1.9) | 3 (2.4) | 4 (1.9) | 3 (2.6) | 23 (1.9) | 3 (2.8) | |||

| 4 | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 5 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Fever | 235 (19.9) | 16 (12.7) | 0.068 | 45 (21.2) | 15 (12.9) | 0.088 | 235 (19.6) | 10 (9.6) | 0.014 |

| Pain | 392 (33.1) | 62 (49.2) | <0.001 | 69 (32.5) | 60 (51.7) | 0.001 | 397 (33.0) | 70 (66.0) | <0.001 |

| Diarrhoea | 125 (10.6) | 2 (1.6) | <0.001 | 31 (14.6) | 2 (1.7) | <0.001 | 132 (11.0) | 1 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Minor ascites | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Vomiting | 77 (6.5) | 11 (8.7) | 0.448 | 14 (6.6) | 11 (9.5) | 0.470 | 76 (6.3) | 4 (4.2) | 0.398 |

| Arrhythmia | 23 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.158 | 5 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | 23 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.250 |

| Wound dehiscence | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | |

| Blood transfusion | 143 (12.1) | 6 (4.8) | 0.021 | 43 (20.3) | 5 (4.3) | <0.001 | 179 (14.9) | 3 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Lung infection | 16 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.390 | 7 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.054 | 18 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.390 |

| Significant pleural effusion | 21 (1.8) | 3 (2.4) | 0.497 | 4 (1.9) | 3 (2.6) | 0.701 | 21 (1.8) | 3 (2.9) | 0.439 |

| Severe ascites | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | |

| Liver failure | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Death | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | |

Adverse events were graded according to the Clavien–Dindo classification system, and a complication of grade ⩾ 3 was considered severe.

Data are presented as the numbers of cases (%) and were compared using Pearson’s Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

MWA, microwave ablation; RES, resection.

Management of tumour recurrence

The types of initial tumour recurrence after MWA or RES are presented in Table 5, indicating that the incidence of extrahepatic recurrence was low, while local tumour progression and intrahepatic distant recurrence were the main types of HCC recurrence. Notably, more patients who experienced recurrence in the MWA group (37/126, 29.4%) were amenable to therapies with curative intent (p < 0.001) than those in the RES group were (179/1183, 15.1%; Table 5). Among the 64 patients with recurrence in the MWA group, 57 underwent repeated ablation, 5 underwent RES, 47 underwent TACE and 1 received sorafenib. Among the 381 patients with recurrence in the RES group, 80 underwent repeated RES, 284 underwent ablation, 316 underwent TACE, 7 received sorafenib, 15 underwent conformal radiotherapy, 5 underwent liver transplantation, 9 received biotherapy, 2 received chemotherapy and 42 received best supportive care.

Table 5.

Characteristics of and therapies for initial tumour recurrences.

| Variable | Overall population |

Propensity-score-matched cohort (2:1) |

Inverse-probability-of-treatment- weighted cohort |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RES (1183) | MWA (126) | p | RES (1183) | MWA (126) | p | RES (1201) | MWA (107) | p | |

| Relapse pattern (%) | |||||||||

| LTP | 39 (3.3) | 17 (13.5) | <0.001 | 9 (4.2) | 16 (13.8) | 0.004 | 43 (3.6) | 19 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| IDR | 309 (26.1) | 46 (36.5) | 0.017 | 57 (26.9) | 41 (35.3) | 0.141 | 316 (26.3) | 25 (23.4) | 0.582 |

| EDR | 33 (2.8) | 1 (0.8) | 0.245 | 5 (2.4) | 1 (0.9) | 0.429 | 33 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.104 |

| Number of intrahepatic recurrent HCCs (%) | |||||||||

| Solitary | 232 (19.6) | 19 (15.1) | 0.267 | 44 (20.8) | 18 (15.5) | 0.312 | 235 (19.6) | 20 (18.7) | 0.927 |

| Multiple | 116 (9.8) | 44 (34.9) | <0.001 | 22 (10.4) | 39 (33.6) | <0.001 | 124 (10.3) | 24 (22.4) | <0.001 |

| Size of intrahepatic recurrent HCCs (cm) | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.5) | 0.900 | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.4) | 0.696 | 1.6 (1.3) | 2 (1.7) | 0.512 |

| Therapy for initial intrahepatic relapse | |||||||||

| Ablation | 130 (11.0) | 34 (27.0) | <0.001 | 15 (7.0) | 32 (27.6) | <0.001 | 128 (10.7) | 29 (27.1) | <0.001 |

| Resection | 49 (4.1) | 3 (2.4) | 0.472 | 7 (3.3) | 3 (2.6) | 1 | 54 (4.5) | 3 (2.8) | 0.619 |

| Noncurative | 169 (14.3) | 26 (20.6) | 0.077 | 44 (20.8) | 22 (19.0) | 0.808 | 177 (14.7) | 12 (11.2) | 0.396 |

Continuous variables are reported as medians (interquartile range) and were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and were compared using Pearson’s Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

EDR, extrahepatic distant recurrence; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IDR, intrahepatic distant recurrence; LTP, Local tumour progression; MWA, microwave ablation; RES, resection.

Discussion

After using two complimentary propensity-score analyses to reduce patient selection bias, the present study indicated that compared with RES, MWA resulted in lower 5-year RFS, and both treatments achieved comparable long-term OS because most patients with intrahepatic recurrence remained eligible for repeat treatments regardless of the initial treatment modality.

In MWA, heat is generated from dipole molecule (water) rotation and ion displacement mediated by microwave transmission. Specifically, compared with conventional RFA, MWA heats up more rapidly, generates higher intratumoural temperatures, treats multifocal disease more quickly and homogeneously, leads to a larger ablation area and is insusceptible to tissue desiccation and charring.24–27 Additionally, MWA is less affected by the perfusion-mediated ‘heat-sink’ effect.28 Interestingly, Huang and colleagues found that MWA was a safe, efficient technology for treating HCC adjacent to large vessels without compromising local tumour recurrence control or OS.29 Recently, a meta-analysis reported that MWA outperformed conventional RFA in cases of larger tumours (OR = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.24–0.89, p = 0.020).30 Our previous study also demonstrated that MWA was superior to RFA in treating HCC within the Milan criteria.3 Thus, compared with RFA, MWA could be a more promising ablation modality.

As MWA has gained popularity in recent years because of the aforementioned advantages, several studies have compared the treatment efficacy of MWA and RES. In 2017, Zhang and colleagues performed a meta-analysis that included 9 studies with a total of 1480 patients and concluded that MWA might even be superior to RES due to no significant differences in OS or RFS between treatments and revealed a shorter operation time, lower blood-loss volumes and fewer complications after MWA treatment.31 In 2018, Chong and colleagues investigated the role of the ALBI score in patient selection for treatment.32 They found that RES offered better OS and RFS in patients with better liver function (ALBI grade 1), while MWA provided a significantly better OS (p = 0.025) and a trend towards better disease-free survival (p = 0.39) in patients with worse liver reserve (ALBI grade 2 or 3). However, the inclusion criteria of patients were different among those studies in the meta-analysis31 and were obscure in the recent study.32 However, compared with RES, MWA resulted in worse tumour recurrence control in our study. Pawlik and colleagues found that the incidence of microvascular invasion was associated with tumour size and number, and for solitary HCCs ⩽ 3 cm, approximately 28% of patients presented with microvascular invasion.33 Compared with MWA, RES may be more likely to guarantee an adequate safe margin and eradication of microvascular invasion, resulting in better tumour recurrence control. However, both treatments provided equivalent OS for the following reasons. First, most patients with intrahepatic recurrence remained eligible for repeat treatments. Rossi and colleagues explored the role of repeated RFA for the management of HCC in a prospective series of 706 patients with 859 HCCs ⩽ 3.5 cm initially treated with RFA and found that 69.4% (323/465) of patients with initial recurrence were restored to disease-free status by repeated RFA.34 In the present study, more than half (37/63 in the MWA group and 179/348 in the RES group) of the patients with intrahepatic recurrence also remained eligible for repeated ablation or RES with curative intent regardless of the initial treatment modality. Furthermore, Rossi and colleagues found that RFA remained highly repeatable for treating subsequent recurrence after initial recurrence, indicating that ablation was particularly valuable for controlling intrahepatic recurrences.34 Second, in the present study, more patients with recurrence in the MWA group (37/126, 29.4%) were amenable to therapies with curative intent than those in the RES group were (179/1183, 15.1%), which would offset the relatively shorter RFS resulting from MWA. Okuwaki and colleagues also found that patients receiving curative, repeated RFA for recurrences had better OS than the OS of patients with similar clinical and tumour characteristics who were treated with noncurative, repeated TACE.35 Third, liver reserve was also an important prognostic factor for the long-term survival of patients with HCC derived from cirrhosis. Patients treated with minimally invasive MWA might benefit from more remnant liver reserve.36 Finally, multivariate Cox analysis also confirmed that MWA was not an independent risk factor for OS.

This study was limited by its retrospective nature, which is susceptible to baseline confounding factors. Indeed, MWA was preferred in patients presenting with more advanced liver disease, smaller lesions and multifocal disease, while RES was usually performed in patients with adequate liver function and solitary large tumours. To improve the intergroup comparability, we applied both PSM and IPW methods to reduce patient selection bias. The conclusion that both treatments had comparable efficacy was maintained, as the results in the overall population and those in the clinically relevant patient subgroups were congruent and were confirmed in the multivariate Cox analysis. The complications recorded in this study were mainly those observed when patients were admitted to clinics, and the prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in this study could be an additional source of bias. Notably, it is prudent that a multidisciplinary team should evaluate tumour location for MWA, and localized, at-risk areas may be safely treated with evolving techniques.24 Moreover, prospective studies are warranted to confirm our findings because different MWA devices seem to produce substantially different ablation volumes and shapes.37 Finally, it is desirable to use appropriate models and advanced statistical methods to reduce the potential bias caused by the treatment after recurrence when comparing the OS of patients treated with MWA or RES.

In summary, although worse tumour recurrence control was observed with MWA than with RES, both treatments offered equivalent long-term OS for patients with HCC within the Milan criteria because most patients still benefited from repeat treatments for recurrent tumours.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_1 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_2 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_3 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_4 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_5 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_6 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_7 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_figure_legends for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuqi Zhang (PhD, Queensland University of Technology) for assisting us with the statistical analysis and American Journal Experts for polishing our manuscript (ID: A650-135D-599E-5E30-F46P). Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou and Chenwei Wang contributed equally to this work. Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81372571), the Sun Yat-Sen University Clinical Research 5010 Programme (no. 2012010), the State ‘973 Programme’ of China (no. 2014CB542005) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 17ykzd34).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Availability of data and material: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ORCID iDs: Wei He  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5801-9044

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5801-9044

Yun Zheng  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6717-3959

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6717-3959

Yunfei Yuan  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2467-3683

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2467-3683

Supplementary material: Supplementary material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Wenwu Liu, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Ruhai Zou, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Ultrasound, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Chenwei Wang, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Jiliang Qiu, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Jingxian Shen, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Medical Imaging, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Yadi Liao, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Zhiwen Yang, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Yuanping Zhang, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Yongjin Wang, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Yichuan Yuan, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Kai Li, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Dinglan Zuo, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Wei He, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Yun Zheng, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Binkui Li, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China; Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Centre, Guangzhou, PR China.

Yunfei Yuan, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China, Collaborative Innovation Centre for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre, 651 Dongfeng East Road, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510060, PR China.

References

- 1. Galle PR, Forner A, Llovet JM, et al. EASL Clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018; 69: 182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2018; 67: 358–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu W, Zheng Y, He W, et al. Microwave vs radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity score analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 48: 671–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choi D, Lim HK, Rhim H, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma as a first-line treatment: long-term results and prognostic factors in a large single-institution series. Eur Radiol 2007; 17: 684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. European Association for the Study of the Liver; European Organisation for R and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012; 56: 908–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2005; 42: 1208–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. He W, Li B, Zheng Y, et al. Resection vs. ablation for alpha-fetoprotein positive hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity score analysis. Liver Int 2016; 36: 1677–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaibori M, Yoshii K, Hasegawa K, et al. Treatment optimization for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients in a Japanese nationwide cohort. Ann Surg 2018. (in press). DOI: 10.1097/sla.0000000000002751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Toyoda H, Lai PB, O’Beirne J, et al. Long-term impact of liver function on curative therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: application of the ALBI grade. Br J Cancer 2016; 114: 744–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Austin PC. The use of propensity score methods with survival or time-to-event outcomes: reporting measures of effect similar to those used in randomized experiments. Stat Med 2014; 33: 1242–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Austin PC. Statistical criteria for selecting the optimal number of untreated subjects matched to each treated subject when using many-to-one matching on the propensity score. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 172: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat 2011; 10: 150–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011; 46: 399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rajyaguru DJ, Borgert AJ, Smith AL, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized hepatocellular carcinoma in nonsurgically managed patients: analysis of the national cancer database. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu S, Ross C, Raebel MA, et al. Use of stabilized inverse propensity scores as weights to directly estimate relative risk and its confidence intervals. Value in Health 2010; 13: 273–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mohkam K, Dumont PN, Manichon AF, et al. No-touch multibipolar radiofrequency ablation vs. surgical resection for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma ranging from 2 to 5cm. J Hepatol 2018; 68: 1172–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van der Wal WM, Geskus RB. IPW: an R package for inverse probability weighting. J Stat Softw 2011; 43: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le Borgne F, Giraudeau B, Querard AH, et al. Comparisons of the performance of different statistical tests for time-to-event analysis with confounding factors: practical illustrations in kidney transplantation. Stat Med 2016; 35: 1103–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lumley T. Analysis of complex survey samples. J Stat Softw 2004; 9: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pompili M, Saviano A, De Matthaeis N, et al. Long-term effectiveness of resection and radiofrequency ablation for single hepatocellular carcinoma </=3 cm. Results of a multicenter Italian survey. J Hepatol 2013; 59: 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joffe MM, Ten Have TR, Feldman HI, et al. Model selection, confounder control, and marginal structural models. Am Stat 2004; 58: 272–279. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cole SR, Hernan MA. Adjusted survival curves with inverse probability weights. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2004; 75: 45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xie J, Liu C. Adjusted Kaplan-Meier estimator and log-rank test with inverse probability of treatment weighting for survival data. Stat Med 2005; 24: 3089–3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nault JC, Sutter O, Nahon P, et al. Percutaneous treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: state of the art and innovations. J Hepatol 2018; 68: 783–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liang P, Wang Y. Microwave ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 2007; 72(Suppl. 1): 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Andreano A, Huang Y, Meloni MF, et al. Microwaves create larger ablations than radiofrequency when controlled for power in ex vivo tissue. Aip Conf Proc 2010; 37: 2967–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yu J, Liang P, Yu X, et al. A comparison of microwave ablation and bipolar radiofrequency ablation both with an internally cooled probe: results in ex vivo and in vivo porcine livers. Eur J Radiol 2011; 79: 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu NC, Raman SS, Kim YJ, et al. Microwave liver ablation: influence of hepatic vein size on heat-sink effect in a porcine model. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2008; 19: 1087–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang S, Yu J, Liang P, et al. Percutaneous microwave ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma adjacent to large vessels: a long-term follow-up. Eur J Radiol 2014; 83: 552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roberts SK, Fazli O. Microwave ablation versus radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Hepatol 2016; 64: S701–S702. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang M, Ma H, Zhang J, et al. Comparison of microwave ablation and hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2017; 10: 4829–4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chong CCN, Lee KF, Chu CM, et al. Microwave ablation provides better survival than liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with borderline liver function: application of ALBI score to patient selection. HPB (Oxford) 2018; 20: 546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pawlik TM, Delman KA, Vauthey JN, et al. Tumor size predicts vascular invasion and histologic grade: implications for selection of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2005; 11: 1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rossi S, Ravetta V, Rosa L, et al. Repeated radiofrequency ablation for management of patients with cirrhosis with small hepatocellular carcinomas: a long-term cohort study. Hepatology 2011; 53: 136–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Okuwaki Y, Nakazawa T, Kokubu S, et al. Repeat radiofrequency ablation provides survival benefit in patients with intrahepatic distant recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 2747–2753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cucchetti A, Piscaglia F, Cescon M, et al. An explorative data-analysis to support the choice between hepatic resection and radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis 2014; 46: 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hoffmann R, Rempp H, Erhard L, et al. Comparison of four microwave ablation devices: an experimental study in ex vivo bovine liver. Radiology 2013; 268: 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_1 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_2 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_3 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_4 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_5 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_6 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_7 for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, Supplementary_figure_legends for Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis by Wenwu Liu, Ruhai Zou, Chenwei Wang, Jiliang Qiu, Jingxian Shen, Yadi Liao, Zhiwen Yang, Yuanping Zhang, Yongjin Wang, Yichuan Yuan, Kai Li, Dinglan Zuo, Wei He, Yun Zheng, Binkui Li and Yunfei Yuan in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology