Abstract

Objectives:

It is uncertain whether consolidation in healthcare markets affects the quality of care provided and health outcomes. We examined whether changes in market competition resulting from acquisitions by two large national for-profit dialysis chains were associated with patient mortality.

Methods:

We identified patients initiating in-center hemodialysis between 2001 and 2009 from a registry of patients with end-stage renal disease in the U.S. We considered two scenarios when evaluating consolidation from dialysis facility acquisitions: one in which we considered only those patients receiving dialysis in markets that became substantially more concentrated to have been affected by consolidation; and another in which all patients living in Hospital Service Areas where a facility was acquired were potentially affected. We used a difference-in-differences study design to examine the associations between market consolidation and changes in mortality rates.

Results:

When we considered the 12,065 patients living in areas that became substantially more consolidated to have been affected by consolidation, we found a nominally significant, 8% (95% CI, 0% to 17%) increase in likelihood of death following consolidation. However, when we considered all 186,158 patients living in areas where an acquisition occurred to have been affected by consolidation, there was no observable effect of market consolidation on mortality.

Conclusions:

Decreased market competition may have led to increased mortality among a relatively small subset of patients initiating in-center hemodialysis in areas that became substantially more concentrated following two large dialysis acquisitions, but not for the majority of patients living in affected areas.

Prècis:

Acquisitions by two large for-profit dialysis chains were marginally associated with higher mortality among new dialysis patients in places where dialysis markets became highly concentrated.

INTRODUCTION:

Many healthcare markets have become increasingly consolidated.1,2 While healthcare market consolidation often leads to higher prices,3–5 its effects on the quality of care provided and health outcomes are less certain.6–9

More than 85% of patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) receiving dialysis are covered by Medicare. Because Medicare administers prices through reimbursement policy, dialysis providers must find ways to attract patients to their facilities other than through offering reduced prices to insurers. Potential associations among competition, quality of care, and health outcomes may be strongest in markets such as dialysis, where predominantly fixed prices may encourage competition on quality rather than price.3,10

Many local dialysis markets became more concentrated over the past 15 years, due primarily to acquisitions by two large for-profit dialysis chains. In 2011, more than 25% of patients had fewer than two nearby dialysis facilities to choose from, and most local dialysis markets were highly concentrated by Federal Trade Commission (FTC) standards.11 Dialysis markets can become concentrated for a variety of reasons, including closures and acquisitions. Dialysis facility closures have been relatively rare, however, and areas affected by closures may be different in important ways from other areas affected by consolidation.12,13 In this study, we examined whether consolidation in US dialysis markets resulting from two large national dialysis acquisitions announced in 2004 affected the likelihood of death among patients initiating in-center hemodialysis in the hospital service areas where facilities were acquired. We focused on mortality during the first 18 months of dialysis, since this is a time when many patients are the least stable clinically14 and would be most susceptible to health consequences from changes in quality of care.

METHODS:

Data Sources

We identified patients receiving in-center hemodialysis between 2001 and 2009 from a U.S. national ESRD registry. Patient comorbidity information came from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Evidence Report (CMS-2728), which nephrologists complete at the onset of ESRD. Information about large dialysis chain ownership came from annual facility surveys, while smaller chain ownership came from CMS Dialysis Facility Compare (DFC). We linked patient zip codes to census-based rural urban commuting area codes15 and data from the Dartmouth Atlas Project16 to identify population density and to assign patients to hospital service areas (HSAs).

Patient Selection

We analyzed two major acquisitions by for-profit U.S. dialysis chains announced in 2004: 1) Fresenius Medical Care’s (FMC) acquisition of Renal Care Group (RCG),17 and; 2) DaVita’s acquisition of Gambro Health Care’s U.S. facilities.18 More than 80% of facilities owned by RCG in 2005 were reported to be owned by FMC (or National Renal Institutes (NRI) due to forced divestiture) by 2007, while more than 80% of facilities owned by Gambro in 2004 were owned by DaVita (or Renal Advantage due to forced divestiture) in 2006.18 We considered facilities that changed ownership during these periods to have been acquired. We defined “transition periods” for the Fresenius and DaVita acquisitions as 2005–2006, and 2004–2005, respectively.

By focusing on consolidation resulting from two large acquisitions, we follow the same approach that has been used in prior studies of the effects of market consolidation in the insurance industry in multiple local markets across the country, such as an analysis of the effects of Aetna’s acquisition of Prudential.19,20 Although mergers and acquisitions have legally distinct definitions, the primary concern in both cases is the resulting impact of consolidation on patient welfare. Moreover, this form of consolidation is becoming more common in the healthcare sector, including several recent large vertical acquisitions, with the potential acquisition of Aetna by CVS21 and Humana’s acquisition of Kindred Healthcare.22

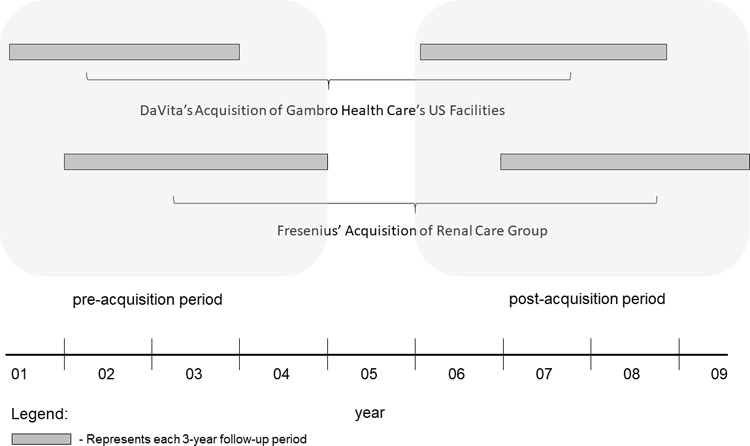

We selected patients initiating in-center hemodialysis in the three years before and after each major acquisition. We designated patients initiating dialysis from 2002–2004 and 2007–2009, as potentially affected by Fresenius’ acquisition of RCG and patients initiating dialysis from 2001–2003 and 2006–2008, as potentially affected by DaVita’s acquisition of Gambro. We considered patients initiating dialysis from 2001–2004 and 2006–2009 to be in the “pre-acquisition” and “post-acquisition” periods, respectively. Because competition for patients can influence all facilities operating in a market23, we considered all patients living in an HSA where a facility was acquired as potentially affected by an acquisition, regardless of whether they initiated dialysis at the acquired facility. Since we were interested in the overall effect of consolidation, rather than the effect of a particular acquisition, we combined the two acquisition cohorts by assigning patients to the acquisition with the largest effect on measured competition in their locality (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Model Selection Diagram.

Footnote: Patients were selected if they started dialysis in the pre-acquisition or post-acquisition period for a given acquisition group. Patients were censored at the end of their assigned pre-acquisition or post-acquisition period.

We excluded patients living in HSAs where an acquired facility was not reported to change ownership by the first year of the relevant post-acquisition period. We required that patients lived and received in-center hemodialysis for 90 days in order to identify a stable in-center hemodialysis population24 and assigned patients to dialysis facilities and zip codes based on where they lived and received dialysis after 90 days of dialysis.

Market Competition Measurement

On January 1 of each year, we identified all prevalent patients receiving in-center hemodialysis and their dialysis facilities and calculated a commonly-used metric of market competition – the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) – for local dialysis markets. The HHI ranges from near zero (perfectly competitive markets) to one (monopolistic markets). We adopted a method used to calculate HHI in healthcare markets that accounts for patients’ decisions to dialyze outside of the HSA where they live4,9,25 and that reflects the numbers of nearby competing facilities from which patients can choose.11 We assumed facilities that share ownership do not compete against one another for patients.

For each HSA, we calculated the average HHI in the three years before and after each acquisition. In order to focus on areas where acquisitions would be more likely lead to consolidation, and where providers would be more likely to respond to changes in competition, we restricted our study to patients initiating dialysis in HSAs that were highly concentrated (average HHI ≥0.25) – as defined by FTC guidelines – in the period prior to each acquisition.26

Exposure Groups

The main study exposure was market consolidation resulting from dialysis facility acquisitions. We applied two criteria to determine whether patients were affected by an acquisition, leading to two exposure groups. In our primary exposure group, we considered patients to be affected by consolidation if they lived in an HSA where an acquisition led to a “substantial” increase in HHI, defined as an average increase of ≥0.1. This is the magnitude of increase considered by the FTC to raise significant anti-competitive concerns in highly concentrated markets.26 In an alternative exposure group, we examined all acquisitions in highly concentrated areas, regardless of the change in HHI. Our rational for including a much broader exposure group is analogous to adoption of the intention to treat principle in clinical trials – we hoped to assess the potential effect of changes in market concentration from acquisitions without obligating that acquisitions had the expected effect on market concentration or whether acquisitions did or did not lead the FTC to require divestiture.

For each exposure group, we considered all remaining patients who started in-center hemodialysis and who lived for at least 90-days to be unaffected by consolidation. This included patients initiating dialysis in non-affected HSAs from 2002–2004 and 2007–2009 or 2001–2003 and 2006–2008. We assigned each unaffected patient to a specific acquisition (i.e. Fresenius’ acquisition of RCG or DaVita’s acquisition of Gambro) based on the year of dialysis initiation. In instances when an unaffected patient could be assigned to either acquisition, we randomly assigned them to an acquisition group (Appendix).

Study Outcomes and Covariates

The main study outcome was time-to-death. We followed patients for the first 18 months of dialysis or until the end of the three-year pre- or post-acquisition window within which they initiated dialysis. We censored patients if they moved to a new HSA for >60 days or recovered renal function. We controlled for patient, geographic, and dialysis facility characteristics listed in Table 1, including dialysis at each of the largest five dialysis chains. We used multiple imputation to account for missing data on albumin, hemoglobin, and body mass index (BMI).27

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics among Patients in Areas with Largest Declines in Market Competition.

| Not affected by consolidation | Affected by consolidation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | diff† | Pre | Post | diff† | p-value (diff-in-diff) | |

| Number of patients | 234,622 | 266,138 | 5,672 | 6,393 | |||

| Patient Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics | |||||||

| Age | 62.7 | 62.6 | −0.1 | 63.0 | 62.8 | −0.2 | 0.61 |

| Male | 53.9 | 55.9 | 2.0 | 52.4 | 55.6 | 3.3 | 0.17 |

| Native American | 1.3 | 1.2 | −0.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.42 |

| Black | 29.0 | 29.2 | 0.2 | 33.1 | 33.6 | 0.5 | 0.67 |

| White | 63.7 | 65.0 | 1.3 | 62.7 | 63.5 | 0.8 | 0.60 |

| Other | 6.0 | 4.7 | −1.4 | 3.7 | 2.2 | −1.4 | 0.89 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 12.3 | 14.5 | 2.2 | 8.3 | 11.2 | 2.9 | 0.23 |

| Employed | 9.2 | 10.5 | 1.3 | 7.4 | 9.4 | 1.9 | 0.25 |

| Medicaid | 25.3 | 25.8 | 0.5 | 26.3 | 27.2 | 0.9 | 0.61 |

| Patient Health Characteristics | |||||||

| Diabetes | 51.2 | 55.2 | 4.0 | 52.1 | 55.1 | 3.0 | 0.28 |

| Coronary artery disease | 26.7 | 20.9 | −5.9 | 29.1 | 23.9 | −5.2 | 0.42 |

| Cancer | 5.8 | 6.8 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 7.1 | 1.2 | 0.66 |

| Heart failure | 32.4 | 32.9 | 0.5 | 36.4 | 36.3 | 0.0 | 0.51 |

| Lung disease | 7.8 | 8.8 | 1.0 | 8.5 | 9.3 | 0.8 | 0.70 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 9.1 | 9.5 | 0.4 | 10.0 | 9.7 | −0.2 | 0.25 |

| PVD | 14.7 | 13.9 | −0.8 | 17.2 | 15.9 | −1.3 | 0.39 |

| Immobility | 3.7 | 6.2 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 7.0 | 2.5 | 0.94 |

| Smokes | 5.2 | 6.4 | 1.2 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 0.21 |

| Drug or alcohol abuse | 1.9 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 0.52 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 27.7 | 29.0 | 1.3 | 28.1 | 29.3 | 1.2 | 0.28 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.9 | 10.0 | 0.1 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 0.89 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.57 |

| Dialysis Facility & Geographic Characteristics | |||||||

| Facility size (patients) | 95.1 | 92.7 | −2.4 | 94.0 | 95.3 | 1.3 | 0.001 |

| For-profit | 78.1 | 80.7 | 2.6 | 90.3 | 92.7 | 2.5 | 0.85 |

| Hospital based | 14.1 | 11.8 | −2.2 | 6.4 | 3.9 | −2.4 | 0.73 |

| Metropolitan | 80.2 | 80.1 | −0.1 | 72.4 | 72.1 | −0.2 | 0.87 |

| Micropolitan | 11.6 | 11.4 | −0.2 | 17.9 | 17.8 | −0.1 | 0.91 |

| Small town | 4.8 | 4.7 | −0.1 | 6.0 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 0.26 |

| Rural | 3.4 | 3.3 | −0.1 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 0.71 |

Diff is the absolute difference between the pre and post periods.

Note: We excluded patients receiving dialysis at Veterans Affairs, prisons, and military facilities, who were less likely to have a choice about where they received dialysis. P-values are obtained from estimates of the interaction term from univariate linear regression analyses where each characteristic is regressed against: 1) consolidation vs. no consolidation; 2) pre vs. post consolidation, and; 3) their interaction. PVD is peripheral vascular disease.

Study Design

We used difference-in-differences (DID) models to estimate the effect of industry consolidation on patient mortality. 23 In the context of a DID analysis, we compared changes in mortality rates following consolidation among patients living in areas that were and were not affected by consolidation. We conducted separate DID analyses using the two exposure groups outlined above. In Cox proportional hazards models, a variable denoting the interaction between being affected by consolidation and initiating dialysis in the post-consolidation period characterized the estimated effect of consolidation on mortality. Because the pre-acquisition and post-acquisition periods spanned different years depending on the acquisition, we included dummy variables for each calendar year.

Additional analyses

Dialysis facility acquisitions can influence care delivery and patient health for reasons unrelated to changes in market competition. For example, new owners may provide a different quality of care, or transitioning ownership may disrupt care for some patients. If the patient, geographic, and dialysis facility characteristics included in our regression models do not fully account for these differences, observed associations between consolidation and mortality could reflect changes in competition or the acquisitions themselves. To address this challenge, we conducted analyses where we excluded patients starting dialysis at acquired facilities. Similar to our primary models, we compared patients living near to acquired facilities (i.e. in the same HSA) to patients living in areas where no acquisitions occurred. This approach has been used to examine changes in competition resulting from consolidation in other healthcare markets.23

We also examined whether the association between consolidation and mortality depends on the magnitude of change in competition among the subset of patients initiating dialysis in HSAs affected by facility acquisitions. We did this by including indicator variables in our Cox models representing different magnitudes of change in HHI following acquisitions (≤0, 0–0.05, 0.05–0.1, >0.1). We included interaction terms denoting whether patients started dialysis in the post-consolidation period in each category of HHI change, and compared estimates associated with these interaction terms. We examined this relationship in separate analyses where we included, and excluded, patients at facilities that were acquired.

It is possible that the effect of consolidation on patient health outcomes varies over time, as the consequences of staff and management changes evolve. We examined this possibility in an analysis where we included separate time-varying interaction terms denoting whether or not patients started dialysis in areas affected by acquisition in each post-acquisition year. Finally, we examined whether the effect of consolidation varied across the two major acquisitions (Supplemental Appendix: Detailed Methods).

This project was approved by an Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine (ID #: H-36408).

RESULTS:

Baseline Characteristics

In both exposure groups, approximately 20% of patients initiating dialysis in the pre-consolidation period died during follow-up, compared with 19% in the post-consolidation period. The unadjusted mortality rate was slightly lower among patients initiating dialysis in the period following acquisitions, regardless of whether patients lived in an area that was affected by consolidation (Appendix Figure 1).

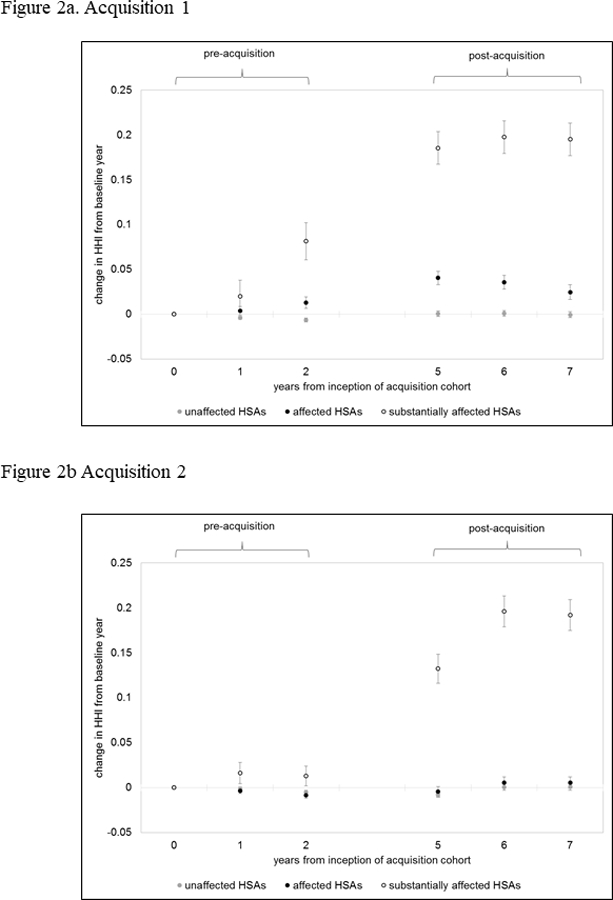

In our examination of patients affected by consolidation who lived in HSAs with a ≥0.1 increase in HHI, 12,065 patients (2.4% of total) were affected by consolidation and 500,760 were unaffected. Using a p-value of less than 0.01 as a marker of heterogeneity across comparison groups, differences over time among patients who were and were not affected by consolidation were balanced across all categories, except for the mean dialysis facility size, which decreased over time in HSAs not affected by consolidation and increased over time in affected HSAs (Table 1). The mean HHI in the period prior to acquisitions was 0.48 and 0.51 among patients living in areas that were and were not affected by consolidation, respectively. The mean HHI increased by 0.162 among patients affected by consolidation, and decreased by 0.001 among unaffected patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Change in Index of Market Competition over Time in Areas Affected by National Acquisitions.

Note: Data is presented at the level of the hospital service area (HSA). Data points represent mean changes from baseline year (i.e. year 0). Error bars represent standard errors of means.

When we considered all patients who lived in an HSA where a facility was acquired to be affected by consolidation, 186,158 (36.3%) patients initiated dialysis in affected HSAs while 326,667 patients were unaffected. In this exposure group, covariates were less balanced among patients who were and were not affected by consolidation (Table 2). The mean HHI in the period prior to acquisitions was 0.45 and 0.55 among patients living in areas affected and unaffected by consolidation, respectively. The mean HHI increased by 0.013 among patients affected by consolidation, and decreased by 0.003 among patients unaffected by consolidation (Figure 2).

Table 2:

Baseline Characteristics among Patients in All Areas Affected by Consolidation.

| not affected by consolidation | affected by consolidation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | diff† | Pre | Post | diff† | p-value (diff-in-diff) | |

| Number of patients | 154,119 | 172,548 | 86,175 | 99,983 | |||

| Patient Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics | |||||||

| Age | 63.1 | 63.1 | 0.0 | 62.1 | 61.9 | −0.2 | 0.02 |

| Male | 54.2 | 56.2 | 2.0 | 53.3 | 55.4 | 2.1 | 0.60 |

| Native American | 1.5 | 1.4 | −0.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | −0.1 | 0.68 |

| Black | 25.1 | 25.2 | 0.1 | 36.3 | 36.4 | 0.0 | 0.63 |

| White | 67.0 | 68.2 | 1.2 | 57.6 | 59.2 | 1.7 | 0.08 |

| Other race | 6.4 | 5.2 | −1.2 | 5.2 | 3.6 | −1.6 | 0.003 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 10.8 | 12.7 | 1.9 | 14.8 | 17.4 | 2.6 | 0.002 |

| Employed | 9.2 | 10.4 | 1.3 | 9.3 | 10.7 | 1.4 | 0.34 |

| Medicaid | 24.6 | 25.1 | 0.5 | 26.7 | 27.2 | 0.5 | 0.90 |

| Patient Health Characteristics | |||||||

| Diabetes | 51.3 | 55.6 | 4.3 | 51.0 | 54.5 | 3.4 | 0.004 |

| Coronary artery disease | 28.4 | 22.6 | −5.8 | 23.9 | 18.1 | −5.8 | 0.75 |

| Cancer | 6.1 | 7.2 | 1.1 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 0.8 | 0.08 |

| Heart failure | 33.5 | 33.7 | 0.2 | 30.5 | 31.6 | 1.1 | 0.001 |

| Lung disease | 8.5 | 9.6 | 1.1 | 6.7 | 7.6 | 0.9 | 0.30 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 9.5 | 9.8 | 0.3 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 0.6 | 0.09 |

| PVD | 15.7 | 14.9 | −0.9 | 13.0 | 12.4 | −0.6 | 0.16 |

| Immobility | 3.8 | 6.3 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 6.1 | 2.5 | 0.80 |

| Smokes | 5.5 | 6.7 | 1.2 | 4.6 | 6.0 | 1.4 | 0.09 |

| Drug or alcohol abuse | 1.8 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 0.82 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 27.7 | 29.1 | 1.4 | 27.6 | 28.9 | 1.3 | 0.17 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 0.1 | 0.03 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.002 |

| Dialysis Facility & Geographic Characteristics | |||||||

| Facility size (patients) | 93.7 | 91.8 | −2.0 | 97.4 | 94.5 | −2.9 | 0.01 |

| For-profit | 73.8 | 76.9 | 3.1 | 86.7 | 88.1 | 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Hospital based | 17.2 | 14.0 | −3.2 | 7.9 | 7.6 | −0.3 | <0.001 |

| Metropolitan | 75.5 | 75.5 | 0.0 | 88.1 | 87.5 | −0.6 | 0.01 |

| Micropolitan | 14.5 | 14.2 | −0.2 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 0.1 | 0.04 |

| Small town | 5.8 | 5.8 | −0.1 | 3.0 | 2.8 | −0.1 | 0.52 |

| Rural | 4.2 | 4.1 | −0.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.49 |

Diff is the absolute difference between the pre and post periods.

Note: We excluded patients receiving dialysis at Veterans Affairs, prisons, and military facilities, who were less likely to have a choice about where they received dialysis. P-values are obtained from estimates of the interaction term from univariate linear regression analyses where each characteristic is regressed against: 1) consolidation vs. no consolidation; 2) pre vs. post consolidation, and; 3) their interaction. PVD is peripheral vascular disease.

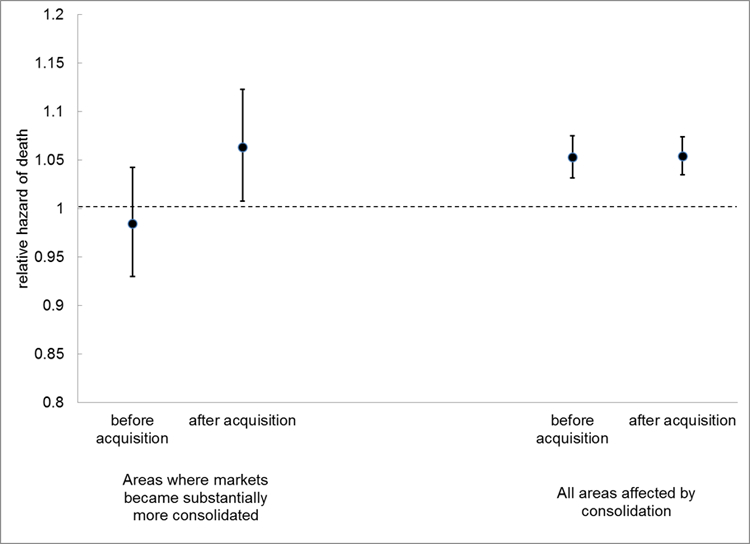

Regression Results

In our primary analysis of patients affected by consolidation who lived in HSAs where the HHI increased by ≥0.1, there was no significant difference in mortality between affected and unaffected patients at baseline (HR=0.98; 95% CI, 0.93–1.04). Affected patients experienced a nominally significant 8% increase in hazard of mortality following acquisitions relative to unaffected patients (HR=1.08; 95% CI, 1.00–1.17) (Figure 3; Appendix Table 1). When we considered all patients living in an HSA where an acquisition occurred to have been affected by consolidation, we did not observe an association between acquisitions and mortality (pinteraction=0.96) (Appendix Table 2).

Figure 3. Estimated Change in Hazard of Death among Patients Affected by Consolidation Relative to Unaffected Patients.

Note: Dotted line represents hazard of death before and after acquisition among patients unaffected by acquisitions.

Additional Analyses

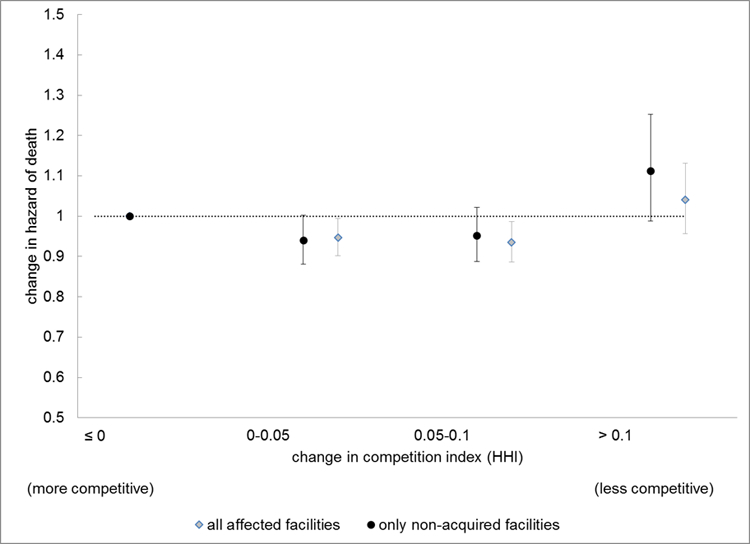

In an analysis where we excluded patients dialyzed at facilities that were directly involved in acquisitions, we found that consolidation led to a 13% increase in hazard of mortality (HR=1.13; 95% CI, 1.01–1.26) in areas where the HHI increased substantially (>0.1). When examining the effect of consolidation across different strata of HHI change (among patients living in areas affected by consolidation), we found that mortality only increased after acquisitions in areas where the HHIs increased by ≥ 0.1, but that this increase was not statistically significant (Figure 4). When examining for potential time-varying effects of consolidation, we found that consolidation was significantly associated with increased mortality in the first post-consolidation year (HR=1.12; 95% CI, 1.02–1.24), but not in the subsequent two years. However, a test for heterogeneity failed to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in the three post-acquisition interaction terms.

Figure 4. Estimated Changes in Mortality Following Acquisitions Stratified by Change in Market Concentration.

Note: Analysis includes all patients in Hospital Service Areas where acquisition occurred. Estimates are from a Cox Regression model identical to our primary analytic model, except that the category of Herfindahl-Hirschman (HHI) is interacted with the post-acquisition period to generate the illustrated estimates.

There was nominally significant variation in the estimated effect of consolidation across the two major acquisitions (Appendix: additional analyses).

DISCUSSION:

Traditional economic models predict that firms operating in less competitive markets are able to raise prices and earn higher profits. In cases where prices are fixed by government policy, firms in less competitive markets may still be able to increase profits by reducing costs through providing lower quality products. Studies of consolidation in hospital markets in the 1990s and early 2000s found that less competition was more closely associated with lower quality of care and worse health outcomes in markets with fixed prices. 3,10 Our findings are consistent with this observation in hospital markets, and suggest that less market competition may be associated with worse health outcomes in some highly concentrated dialysis markets where prices are predominantly fixed by Medicare reimbursement policy.

Although the small number of patients initiating dialysis in highly concentrated areas where the HHI increased by more than 0.1 limited our ability to make definitive conclusions about the effect of market competition on mortality, our finding is concerning when considering ongoing consolidation in markets for dialysis and other healthcare services. For instance, in 2011 DaVita acquired DSI, which directly involved 106 dialysis facilities and approximately 8,000 patients.28 Later that year, Fresenius acquired Liberty Dialysis and Renal Advantage, which involved 260 dialysis facilities and approximately 19,000 patients.29 As additional patient health data become available, it will be important to monitor the consequences of these and other more recent acquisitions in markets most affected by consolidation.

Our findings suggest that the health consequences associated with consolidation vary within and across markets and possibly over time. Dialysis facilities that are acquired may differ from those that are not acquired. Greater staffing intensity, lower facility capacity (i.e., fewer stations per patient), and larger size of markets predict acquisitions by large dialysis chains.30 Improvements in management associated with transition from a poorly managed facility to a large dialysis chain could mask negative health consequences from decreased market competition. However, when we excluded patients at facilities that were acquired, we continued to observe an increase in mortality in regions that became substantially less competitive following acquisitions. We also observed that the health consequences from consolidation may have depended upon which of the two major acquisitions affected an area, suggesting that changes in the delivery of care in response to market competition may depend on the acquiring facility (or chain).

When examining for time-varying effects of acquisitions, we found that increased mortality associated with acquisitions may only have occurred in the year immediately following acquisitions. It is possible that, due to disruptions in facility operations, ownership change is a time when care delivery may be compromised, and when competition may have an important role in preserving high quality of care. While we were unable to demonstrate that observed heterogeneity in the effect of consolidation was statistically significant, this secondary analysis may also have been limited by small numbers of patients in areas where acquisitions led to substantial market consolidation. It will be important for future studies to examine whether effects of market competition on quality of care are most pronounced during certain key times, such as when providers in a market undergo organizational change.

There are several possible reasons why we did not observe an association between acquisitions and mortality for a majority of patients initiating in-center hemodialysis. First, in many instances dialysis facility acquisitions did not actually lead to more concentrated markets. We previously demonstrated that, while the national market shares of the two largest dialysis providers have increased over time, patients did not – on average – face fewer choices among competing dialysis facilities in 2011 compared to 2001.11 In the current study, the mean HHI increased by only 0.016 more in HSAs where acquisitions occurred compared to HSAs where acquisitions did not occur. It is also possible that, in many areas where markets became more concentrated, dialysis facilities did not change how they cared for patients. Patients can be assigned to a dialysis facility for a number of reasons that may not change immediately in response to declining market competition. For example, nearly half of patients receive dialysis at the facility closest to where they live.9 A strong preference for receiving dialysis close to home may outweigh other benefits that dialysis facilities might offer in an effort to attract patients. Or, patients may be assigned to a dialysis facility based on existing financial arrangements between a facility and physicians or hospitals, such as medical directorships and/or joint ventures. It may take longer than three years for changes in these relationships to reflect less competitive dialysis markets. Facilities may compete for patients by offering incentives unrelated to health outcomes. Two studies suggest that more competitive dialysis markets led primarily to more “amenities” available to patients (e.g., high-definition television, expanded entertainment options, more comfortable chairs).7,31 While more amenities may improve patients’ satisfaction with the care they receive, they are unlikely to influence major health outcomes such as mortality. Finally, regulatory efforts by CMS and the ESRD Networks may ensure adequate quality of care in most markets irrespective of competition.

Our study design addressed two common sources of bias that can occur in observational studies examining the health consequences of market competition. First, our use of difference-in-differences enabled us to designate each group that was either affected or unaffected by consolidation as its own “control”, eliminating bias from unobserved differences between these comparison groups that do not change over time. Second, bias can occur when examining the association between metrics of market competition and health outcomes if patients choose to receive care from higher quality providers.19 However, any changes over time in the perceived quality of care delivered in dialysis markets would likely have been related to changing ownership due to acquisitions. It is reassuring, therefore, that our findings did not change noticeably when we excluded patients initiating dialysis at facilities that were acquired.

This study has several limitations. We focused on the effect of industry consolidation on mortality that can be explained by changes in competition. While understanding the independent effect of market competition on quality of care delivered and mortality is important, particularly given more recent consolidation in dialysis markets and other markets for healthcare services, this is only one way in which acquisitions and consolidation may affect patient health. For instance, competition in dialysis markets may also be associated with hospitalizations, including hospitalization for infection.32 In our primary analyses, we did not attempt to disentangle the effects of consolidation versus management change from acquisitions on patient health. It is reassuring, however, that our findings did not change substantively in a sensitivity analysis where we excluded facilities that were actually acquired. We did not examine the specific mechanisms by which changes in competition may have affected care delivery and mortality. We also did not study whether consolidation influenced providers’ decisions regarding how to deliver dialysis (dialysis modality), patients’ satisfaction with the care they receive, or access to care. Finally, observed imbalances in characteristics in our analysis of all acquisitions suggests that the treatment and control groups in this comparison may have also changed in unobserved ways, which could lead to bias.

In summary, for patients who initiated in-center hemodialysis in highly concentrated U.S. dialysis markets between 2001 and 2009 where acquisitions by two large dialysis chains led to substantial increases in market consolidation, we found a nominally significant relative increase in mortality risk of 8%. The estimated increase in mortality was larger (13%) and was statistically significant when we excluded patients initiating dialysis at facilities that were acquired. However, increased consolidation of this magnitude affected only a small subset of patients initiating hemodialysis. For the majority of patients living in areas where an acquisition occurred, we did not find evidence that acquisitions affected the risk of death. The observed association between consolidation and mortality may have been limited to the time-period immediately following acquisitions or could be due to chance.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our finding that industry consolidation resulting from two large national dialysis chain acquisitions may have led to increased mortality in areas where dialysis markets became substantially less competitive following acquisitions suggests that market competition may have an important role in preserving the quality of care in healthcare markets where prices are predominantly fixed by government reimbursement policy. This may be particularly relevant during periods of organizational transition. It will be important to identify areas where more recent – and future – acquisitions have the most substantial effect on market competition in order to assess for potential downstream effects on quality of care and health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS:

It is uncertain whether consolidation in healthcare markets affects the quality of care provided and health outcomes. Because Medicare covers a vast majority of patients receiving dialysis in the U.S., dialysis care is delivered in a predominantly fixed-price setting. The association between market competition and health outcomes may be more pronounced in fixed-price settings like dialysis, where providers must compete for patients on things other than prices.

We examined whether changes in market competition resulting from acquisitions by two large national for-profit dialysis chains were associated with patient mortality. We found a nominally significant 8 percent increase in mortality among patients living in areas that became substantially more consolidated following acquisitions. However, when considering all patients living in areas where acquisitions occurred, there was no observable effect of market consolidation on mortality

Decreased market competition may have led to increased mortality among a relatively small subset of patients initiating in-center hemodialysis in areas that became substantially more concentrated following two large dialysis acquisitions, but not for the majority of patients living in affected areas.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Author Access to Data: This work was conducted under a data use agreement between Dr. Winkelmayer and the National Institutes for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). An NIDDK officer reviewed the manuscript and approved it for submission. The data reported here have been supplied by the U S Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government.

FUNDING:

Funding: K23 1K23DK101693–01 from NIDDK (Dr. Erickson); DK085446 (Dr. Chertow); Dr. Bhattacharya would like to thank the National Institute on Aging for support for his work on this paper (R37 150127–5054662-0002). This material was also supported by the use of facilities and resources of the Houston VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN13–413). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the US government or Baylor College of Medicine.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Dafny L Hospital industry consolidation--still more to come? New England Journal of Medicine 2014;370(3):198–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai TC, Jha AK. Hospital consolidation, competition, and quality: is bigger necessarily better? JAMA 2014;312(1):29–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaynor M, Town R. The impact of hospital consolidation: update. June, 2012. (http://www.rwjf.org.laneproxy.stanford.edu/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2012/rwjf73261). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Royalty AB, Levin Z. Physician practice competition and prices paid by private insurers for office visits. JAMA 2014;312(16):1653–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dafny L, Duggan M, Ramanarayanan S. Paying a Premium on Your Premium? Consolidation in the US Health Insurance Industry. American Economic Review 2012;102(2):1161–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Town RJ, Vogt W. How has hospital consolidation affected the price and quality of hospital care? [Internet]. Research Synthesis Report 2006. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2006/rwjf12056/subassets/rwjf12056_1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Held PJ, Pauly MV. Competition and efficiency in the end stage renal disease program. Journal of Health Economics 1983;2(2):95–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang V, Lee S-YD, Patel UD, Maciejewski ML, Ricketts TC. Longitudinal analysis of market factors associated with provision of peritoneal dialysis services. Medical Care Research & Review 2011;68(5):537–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee DKK, Chertow GM, Zenios SA. Reexploring differences among for-profit and nonprofit dialysis providers. Health services research 2010;45(3):633–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaynor M What Do We Know About Competition And Quality In Health Care Markets? : National Bureau of Economic Research;2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson KF, Zheng Y, Ho V, Winkelmayer WC, Bhattacharya J, Chertow GM. Consolidation in the Dialysis Industry, Patient Choice, and Local Market Competition. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN 2016;Published online before print(doi: 10.2215/CJN.06340616). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. March 2015 Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 3/13/2015 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. March 2018 Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; March/2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson BM, Zhang J, Morgenstern H, et al. Worldwide, mortality risk is high soon after initiation of hemodialysis. Kidney Int 2014;85(1):158–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (RUCA) WWAMI Rural Health Research Center; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher ES, Goodman D, Skinner J, Bronner K. Health care spending, quality, and outcomes Hannover, NH: The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice;2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Businesswire Fresenius Medical Care to Acquire Renal Care Group, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.PRNewswire DaVita to Acquire Gambro Healthcare, a Renal Dialysis Services Company; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dafny L, Duggan M, Ramanarayanan S. Paying a Premium on Your Premium? Consolidation in the US Health Insurance Industry. American Economic Review 2012;102(2):1161–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guardado J, Emmons D, Kane C. The Price Effects of a Large Merger of Health Insurers: A Case Study of UnitedHealth-Sierra. Health Management, Policy and Innovation 2013;1(3):16–35. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Donnell C, Humer C. CVS Health to acquire Aetna for $69 billion in year’s largest acquisition. Reuters: Business News December 3, 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staff R Humana, private equity firms buy Kindred Healthcare for $810 million. Reuters December 19, 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.L D. Estimation and Identification of Merger Effects. The Journal of Law and Economics 2009;52(3). [Google Scholar]

- 24.USRDS. 2015 Researcher’s Guide to the USRDS Database Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases;2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler DP, McClellan MB. Is Hospital Competition Socially Wasteful? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2000;115(No. 2):577–615. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horizontal Merger Guidelines In: Commission USDoJatFT, ed. Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montez-Rath ME, Winkelmayer WC, Desai M. Addressing Missing Data in Clinical Studies of Kidney Diseases. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DaVita to Acquire DSI Renal, Inc; In: Businesswire, ed2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bryant C Fresenius acquires dialysis rivals for $2bn In: Times F, ed: London, UK; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pozniak AS, Hirth RA, Banaszak-Holl J, Wheeler JRC. Predictors of chain acquisition among independent dialysis facilities. Health services research 2010;45(2):476–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirth RA, Chernew ME, Orzol SM. Ownership, competition, and the adoption of new technologies and cost-saving practices in a fixed-price environment. Inquiry 2000;37(3):282–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erickson KF, Zheng Y, Ho V, Winkelmayer W, Bhattacharya J, Chertow GM. Market Competition and Health Outcomes in Hemodialysis. Health Services 2017;(in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.