Abstract

Oligodendrocytes are vulnerable to excitotoxic signals mediated by AMPA receptors and by high- and low-affinity kainate receptors. Here we investigated the nature of the cell death triggered by activation of these receptors in primary cultures of oligodendrocytes from the rat optic nerve. Activation of AMPA receptors at both submaximal and maximal concentrations of the agonist induced massive calcium entry, mitochondrial depolarization, and a rise in the level of reactive oxygen species that correlated with a decrease in the levels of reduced glutathione. In addition, excitotoxicity initiated by submaximal, but not maximal, activation of AMPA receptors was prevented by caspase-3 blockade and by the concomitant blockade of caspases 8 and 9. In turn, maximal activation of high- or low-affinity kainate receptors induced mitochondrial events and toxicity levels similar to those observed with submaximal activation of AMPA receptors. In contrast to AMPA receptor-mediated insults, calcineurin inhibition or caspase-9 blockade was sufficient to prevent cell death triggered by both types of kainate receptors. Consistent with these results, prolonged glutamate receptor activation in freshly isolated optic nerves caused selective activation of caspase-3 and chromatin condensation in oligodendrocytes. Overall, the evidence presented here indicates that oligodendrocyte death by excitotoxicity is mediated by caspase-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

Keywords: AMPA receptor, kainate receptor, calcium, mitochondria, apoptosis, excitotoxicity, optic nerve

Introduction

CNS neurons bearing glutamate receptors are vulnerable to excitotoxicity (Olney and Sharpe, 1969; Choi and Rothman, 1990), a feature whereby excessive activation of glutamate receptors triggers cell death. High concentrations of extracellular glutamate, generated after traumatic or ischemic CNS injury, results in NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptor activation and, consequently, in the massive influx of Na+ and Ca2+ overload, which trigger neuronal death (Choi, 1995). The characteristics of excitotoxic cell death are related to the intensity of receptor activation and involve two temporally distinct phases of necrosis and apoptosis depending on mitochondrial functioning (Nicotera and Lipton, 1999).

Two convergent cascades have been described to lead to apoptosis. The so-called extrinsic pathway is exemplified by a receptor-initiated proapoptotic signal, such as Fas (Ashkenazi and Dixit, 1999) or cytokines (Hengartner, 2000). In this pathway, ligands induce the formation of receptor complexes that recruit caspase-8 or caspase-10. These autocatalyze and thereby activate other caspases that kill the cell. In contrast, the intrinsic, or mitochondrial, apoptotic pathway is activated by cytotoxic stress and some developmental events, and it is thought to be triggered by translocation into the mitochondria of Bax, a proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member (Gross et al., 1999). This results in the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol, which in turn binds to apoptosis protease activating factor-1 (Apaf-1), forms an oligomeric assembly or “apoptosome,” and thus activates caspase-9 and subsequently caspase-3 (Hengartner, 2000). Other released mitochondrial proteins such as Smac/Diablo contribute to caspase activation, whereas apoptosis-inducing factor and endonuclease G appear to kill independently of caspases (Candé et al., 2002).

Cross talk between the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways occurs at several levels. For example, the former can recruit the latter by the use of intermediates such as Bid (Li et al., 1998). In addition, recent evidence suggests that mitochondria in some instances may act as amplifiers of caspase activity rather than initiators of caspase activation (Lassus et al., 2002; Marsden et al., 2002).

Oligodendrocytes also express glutamate receptors (Verkhratsky and Steinhäuser, 2000) and, like neurons, are liable to be damaged by excessive glutamate signaling in vitro and in vivo (Yoshioka et al., 1996; Matute et al., 1997; McDonald et al., 1998). Excitotoxicity in oligodendrocytes is initiated by Ca2+ influx through AMPA receptors and high- and low-affinity kainate receptors (Sánchez-Gómez and Matute, 1999; Alberdi et al., 2002). However, the biochemical events downstream of massive Ca2+ entry that lead to oligodendrocyte death have not yet been characterized. In the present study, we investigated the molecular cascades initiated by the activation of AMPA and kainate receptors that ultimately lead to oligodendrocyte death. Our results indicate that excitotoxic insults induce oligodendrocyte death by caspase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. The differential mechanisms involved are receptor specific and depend on the intensity of their activation.

Materials and Methods

Glutamate receptor drugs. AMPA and cyclothiazide (CTZ) (Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK), kainate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). and GYKI53655, kindly supplied by D. Leander (Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN), were first dissolved in an equimolar solution of NaOH (AMPA and kainate), ethanol (CTZ), or DMSO (GYKI53655) and were then added to culture medium to achieve the desired final concentration. l-Glutamic acid and CNQX (Sigma) were dissolved directly in the incubating solution.

Optic nerve cultures. Primary cultures of oligodendrocytes derived from the optic nerves of 12-d-old Sprague Dawley rats, C57BL/6J wild-type mice, and mice transgenic for the bcl-2 gene (Martinou et al., 1994) were obtained as described previously (Barres et al., 1992), with minor modifications (Alberdi et al., 2002). Cells were seeded into 24-well plates bearing 12-mm-diameter coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine (10 μg/ml) and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a chemically defined medium (Barres et al., 1992). After 3 d in vitro, cultures were composed of at least 98% O4/GalC+ cells; the majority of the remaining cells were GFAP+. No A2B5+ or microglial cells were detected in these cultures (Alberdi et al., 2002).

To select transgenic mice for culture, the presence of the bcl-2 transgene was assayed using PCR (Martinou et al., 1994) and immunocytochemical staining with monoclonal antibodies to the human Bcl-2 protein (Cambridge Research Biochemicals, London, UK). Oligodendrocyte cultures derived from transgenic mice were strongly immunoreactive to these antibodies, whereas those obtained from wild-type mice were only weakly stained.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i. The concentration of intracellular calcium [Ca2+]i was determined according to the method of Grynkiewikcz et al. (1985). Oligodendrocytes were incubated with fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at 5 μm in culture medium for 30-45 min at 37°C. Cells were washed of excess fura-2 AM by incubating in HBSS containing 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 mm glucose, and 2 mm CaCl2 (incubation buffer) for 5 min at room temperature (RT). Experiments were performed in a coverslip chamber, continuously perfused with incubation buffer at 2 ml/min. The perfusion chamber was mounted on the stage of a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) inverted epifluorescence microscope (Axiovert 35), equipped with a 150 W xenon Polychrome IV lamp (T.I.L.L. Photonics, Martinsried, Germany) and a Plan Neofluar 40 × oil immersion objective (Zeiss). Cells were visualized with a high-resolution digital B/W CCD camera (ORCA), and image acquisition and data analysis were performed using the AquaCosmos software program (Hamamatsu, Iberica, Spain). At the end of the assay, in situ calibration was performed with the successive addition of 10 mm ionomycin and 2 m Tris-50 mm EGTA, pH 8.5. The [Ca2+]i concentration was estimated by the 340/380 ratio method, using a Kd value of 224 nm. Data were analyzed with Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA) and Prism (Lake Forest, CA) software.

Measurement of mitochondrial potential. Oligodendrocyte cultures were exposed to AMPA and kainate receptor agonists as above. Thereafter, cells were loaded with 100 nm tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) and 1 μm calcein AM (both from Molecular Probes). Calcein fluorescence, a common agent used to test cell viability, was used here to quantify the number of cells within the reading field. Fluorescence was measured using a Fluoroskan Ascent plate fluorimeter (Thermo Lab Systems, Altrincham, UK), and data were expressed as a percentage of TMRE/calcein fluorescence in controls. Excitation and emission wavelengths for TMRE and calcein were as suggested by the supplier. All experiments (n = 5) were performed at least in triplicate and plotted as mean ± SEM.

Free radical and glutathione measurements. Oligodendroglial cultures were exposed to AMPA and kainate receptor agonists as described. Subsequently, cells were loaded with 40 μm dichloro-H2-fluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) (Molecular Probes) and 5 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (control dye) to assay the levels of free radicals; loading with 50 μm monochlorobimane (MclBim) (Molecular Probes) and 1 μm calcein AM (control dye) permitted an evaluation of the levels of reduced glutathione. Fluorescence was measured in a CytoFluor-2350 system (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and values were plotted as the percentage of DCFDA/Hoechst fluorescence (free radicals) or as the percentage of MClBim/calcein (glutathione) with respect to controls. Excitation and emission wavelengths for DCFDA and MClBim/Hoechst were as suggested by the supplier. All experiments (n = 5) were performed at least in triplicate and plotted as mean ± SEM.

Cell viability and toxicity assays. Cell toxicity and viability assays were performed as described previously (Sánchez-Gómez and Matute, 1999). After 2 d in culture, oligodendrocytes were exposed to 100 μm CTZ or 100 μm GYKI53655 for 10 min before incubation with AMPA or kainate, respectively. Agonists were applied for 15 min, and then the cells were incubated for 24 hr in fresh medium. For treatments with caspase inhibitors, cells were pretreated with the appropriate dilutions of drugs or DMSO (vehicle) in conjunction with GYKI5365 or CTZ, and they were present during incubation with agonist. The following caspase inhibitors were prepared in DMSO according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Peptides International, Louisville, KY): N-benzyloxycarbonyl-valyl-alanyl-aspart-(OMe)-fluoromethylketone (ZVAD) (Enzyme Systems Products, Dublin, CA); acetyl-tyrosyl-valyl-alanyl-aspart-1-aldehyde (Ac-YVAD-H); acetyl-aspartyl-glutamyl-valyl-aspart-1-aldehyde (Ac-DEVD-H); acetyl-isoleucyl-glutamyl-threonyl-aspart-1-aldehyde (Ac-IETD-H); and acetyl-leucyl-glutamyl-histidyl-aspart-1-aldehyde (Ac-LEHD-H). Oligodendrocyte viability was assessed 24 hr later using fluorescein diacetate (60 μg/ml) as described previously (Jones and Senft, 1985; Sánchez-Gómez and Matute, 1999). All experiments were performed in duplicate, and the values provided here are the average of at least three independent experiments. Hoechst 33258 (5 μg/ml; Sigma) staining was performed as indicated by the supplier.

Immunocytochemistry in oligodendrocyte cultures. Oligodendrocytes were exposed to agonists and fixed with 4% formaldehyde freshly generated from paraformaldehyde, in PBS at 15-120 min after stimulation. Immunocytochemistry using a polyclonal antibody to cytochrome c (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was performed as described previously (Ouyang et al., 1999). Cells were washed twice in PBS for 5 min at RT and permeabilized in PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (TX100) for 30 min, and nonspecific binding sites were blocked in 3% BSA in PBS-0.2% TX100 for 30 min. The primary antibody was diluted 1:100 in PBS-0.1% TX100 and 5% NGS and applied overnight at 4°C. Primary polyclonal antibodies to activated caspase-9 and caspase-3, diluted 1:100 in 5% BSA-PBS, were used according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Cell Signaling Technology; Beverly, MA). Cells were labeled for 2 hr at RT with fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (heavy and light). In all cases, cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 to simultaneously evaluate nuclear condensation. Cells presenting activated caspase-9 or caspase-3 immunoreactivity were counted, and data were plotted as a percentage of positive cells in control coverslips. Negative controls included omission of the primary antibody and preincubation with the corresponding immunizing peptide at the concentration suggested by the supplier. No staining was observed under these conditions. All experiments (n = 3) were performed in duplicate.

Preparation of optic nerves, drug perfusion, and immunohistochemistry. Adult male Sprague Dawley rats were anesthetized deeply with chloroform and then decapitated. Optic nerves were freed from of their meninges in artificial CSF (aCSF) (in mm: 126 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 2 mm CaCl2·2H2O) supplemented with 10 mm glucose. Subsequently, the nerves were placed into a chamber and perfused for 3 hr with oxygen-saturated aCSF, to which glutamate (1 mm) alone or in the presence of CNQX (30 μm) was applied. After perfusion, the nerves were fixed for 2 hr in 4% formaldehyde freshly generated from paraformaldehyde, in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, cryoprotected in 15% sucrose, and frozen. Cryostat sections (10 μm thick) were mounted onto glass slides and processed for double immunofluorescence with rabbit antibodies to caspase-3 (diluted 1:100; Cell Signaling Technology) and mouse monoclonal antibodies to the cell-type markers OX42 (mouse anti-rat CD11b; 10 μg/ml; Serotec, Kidlington, Oxford, UK) and APC (Ab-7) (anti-adenomatous polyposis coli; 1 μg/ml; Oncogene Research, Boston, MA) specific for microglia and oligodendrocytes, respectively. Rabbit antibodies were detected with fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Alexa Fluor 488; Molecular Probes). Monoclonal antibodies were detected with red-fluorescent Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Molecular Probes). When one of the primary antibodies was omitted, no corresponding fluorescence was observed, indicating the absence of secondary antibody cross-reactivity.

Data analyses. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n), where n refers to the number of cultures assayed. A one-way ANOVA (Fisher's PLSD test) followed by contrast testing was used to compare the data from multiple groups, and the Student's t test was used for data obtained from in situ experiments, in which only two groups were compared. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05.

Results

Mitochondria depolarization reveals massive calcium influx during AMPA and kainate receptor activation

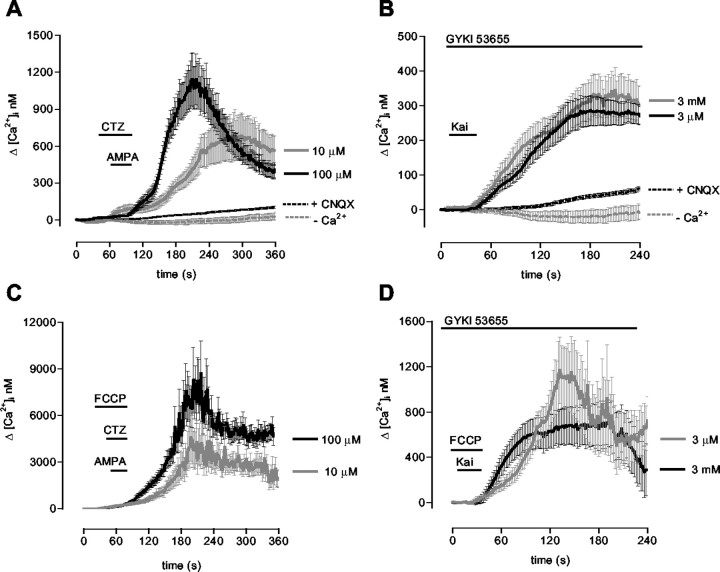

We showed previously that AMPA and kainate receptor activation evokes a substantial increase in cytosolic calcium levels in whole populations of cultured oligodendrocytes (Alberdi et al., 2002). Here, we analyzed by microfluorometry the changes of [Ca2+]i in individual oligodendrocytes after brief exposure (30 sec) to AMPA and kainate. Selective activation of AMPA receptors with 10 and 100 μm AMPA in the presence of 100 μm CTZ increased the [Ca2+]i basal levels by 696 ± 200 nm (n = 21) and 1143 ± 209 nm (n = 23), respectively (Fig. 1A). The rise in [Ca2+]i evoked by 10 μm AMPA was observed to occur more slowly.

Figure 1.

AMPA and kainate receptor activation in rat oligodendrocytes results in Ca2+ overload and rapid mitochondrial uptake. Cells loaded with fura-2 were exposed to 10 or 100 μm AMPA together 100 μm CTZ (A, C) or to 3 μm and 3 mm kainate in the presence of the AMPA receptor antagonist GYKI53655 (100 μm) (B, D). A, B, [Ca2+]i increases induced by receptor activation are abolished by 30 μm CNQX and are absent in Ca2+-free medium. C, D, Mitochondrial depolarization with FCCP (1 μm) while activating the receptors induces a drastic elevation in [Ca2+]i. The increase in [Ca2+]i was calculated by subtracting basal [Ca2+]i in the absence of agonists (A, B) and in the presence of FCCP alone (C, D). The curves illustrate average ± SEM responses of 61-87 cells from at least six different experiments. Kai, Kainate.

Kainate activates both AMPA and kainate receptors. To study the effects mediated by kainate receptors alone, we used kainate in the presence of GYKI53655 (100 μm), an AMPA receptor antagonist (Paternain et al., 1995). Oligodendrocytes express all kainate receptor subunits, and excitotoxicity initiated by kainate receptor activation can be mediated by high- and low-affinity receptors (Sánchez-Gómez and Matute, 1999). To activate both subclasses of kainate receptors, we used kainate at 3 μm and 3 mm. Under these conditions, we observed that [Ca2+]i increased with a similar amplitude and time course (Fig. 1B) and that peak [Ca2+]i values were 281 ± 37 nm (n = 20) and 345 ± 57 nm (n = 14) for high- and low-affinity kainate receptors, respectively. In all cells studied, basal [Ca2+]i remained unaltered after AMPA and kainate receptor activation in the presence of CNQX, an AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist, or in the absence of Ca2+ in the incubation buffer, indicating that the observed increase in [Ca2+]i is attributable to Ca2+ influx specifically triggered by receptor activation.

The mitochondrion is a major regulator of cytosolic Ca2+ levels. With a view to evaluating whether this organelle contributes to sequestering Ca2+ during activation of oligodendrocyte AMPA and kainate receptors, we evaluated changes in the [Ca2+]i in the presence of the a mitochondrial proton gradient uncoupler carbonylcyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP). This agent dissipates the mitochondrial membrane potential and releases Ca2+ from mitochondria but prevents further Ca2+ uptake. Application of FCCP alone (1 μm) increased [Ca2+]i by 1.1 ± 0.2 μm (n = 66; data not shown). However, the net rise in [Ca2+]i in oligodendrocytes exposed to 10 and 100 μm AMPA in the presence of both CTZ and FCCP was 4.6 ± 1.5 μm (n = 16) and 8.7 ± 2.1 μm (n = 47), respectively (Fig. 1C). In addition, selective activation of high- and low-affinity kainate receptors in the presence of GYKI 53655 and FCCP increased [Ca2+]i with a net maximal amplitude at 1125 ± 194 nm (n = 29) and 706 ± 194 nm (n = 29), respectively (Fig. 1D).

Overall, the results using FCCP indicate that Ca2+ influx during AMPA and kainate receptor activation in oligodendrocytes induces a massive increase in [Ca2+]i and that a substantial part of it is rapidly sequestered by mitochondria. In addition, these findings suggest that efficiency of mitochondrial calcium uptake is higher after activation of AMPA receptors.

Excitotoxic insults lead to mitochondrial depolarization, oxidative stress, and the release of cytochrome c

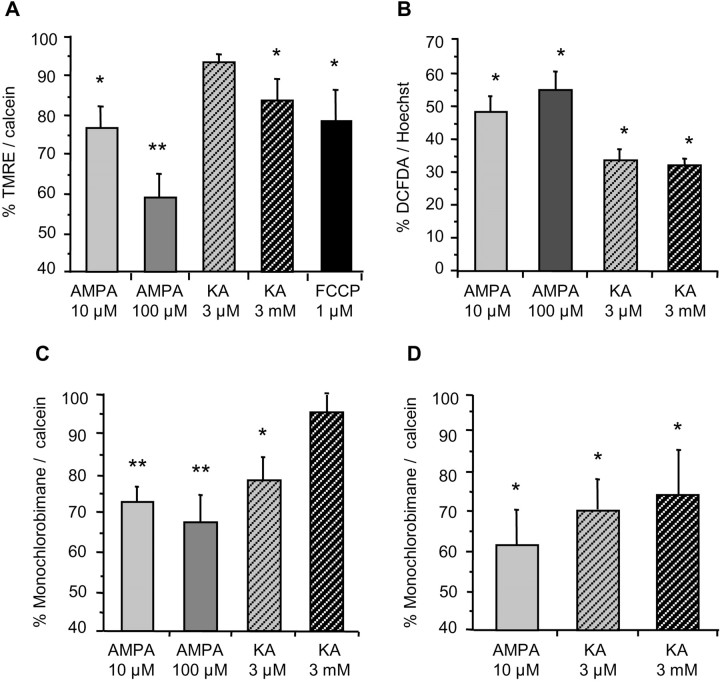

Mitochondrial calcium accumulation has been reported to cause a loss of transmembrane potential as well as the acute generation of reactive oxygen species (Lenaz et al., 2002). Using the cationic dye TMRE (100 nm), which accumulates in mitochondria under normal conditions, we monitored mitochondrial potential in oligodendrocytes after excitotoxic insults mediated by AMPA and kainate receptors. Application of the mitochondrial proton gradient uncoupler FCCP (1 μm, 10 min), as a positive control led to a reduction in TMRE fluorescence (77.9% of control, nontreated oligodendrocytes) (Fig. 2A). Selective activation of AMPA and kainate receptors also caused mitochondrial depolarization at 15 min after-stimulation, which was statistically significant for AMPA and low-affinity kainate receptors (Fig. 2A). Maximal mitochondrial depolarization was measured in cells treated with 100 μm AMPA (59.1% of control). Submaximal AMPA and low-affinity kainate receptor activation caused a lower but statistically significant reduction in TMRE fluorescence (23.5 and 16.2% decreases, respectively).

Figure 2.

Excitotoxic insults induce mitochondrial depolarization and oxidative stress in rat oligodendrocytes. Cultures were first exposed to glutamate receptor agonists for 15 min, and cells were immediately loaded with the corresponding dyes to monitor by fluorimetry depolarization of the mitochondria (A) and generation of radical species (B), both at 15 min after stimulation and levels of reduced glutathione at 15-30 min of agonist removal (C, D). A, Mitochondrial membrane potential diminishes significantly for all receptors assayed but for high-affinity kainate receptors (KA 3 μm). FCCP, a mitochondrial uncoupler, was used as an internal control. B, Radical species increase after activation of the receptor in all conditions studied. C, D, Levels of reduced glutathione start declining at 15 min (left) and decrease further at 30 min (right). Values represent mean ± SEM of triplicates from three to five different experiments. In A, C, and D, each culture measurements was normalized to calcein fluorescence, an indicator of cell viability, and 100% represents control values in the absence of agents. In B, fluorochrome signal was referred to chromatin stain with Hoechst 33258, and 0% represents basal signal in control cells. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA (Fisher's PLSD test). KA, Kainate.

We next examined whether AMPA/kainate receptor activation in oligodendrocytes generates reactive species as a consequence of oxidative stress. Using DCFDA, a dye that fluoresces during cleavage and subsequent oxidation within the living cell, we observed that the basal DCFDA signal in control oligodendrocyte cultures significantly increased 15 min after activation up to 54.9 and 48.6% in the case of maximal and submaximal AMPA receptor activation and to 33.6 and 32.0% in the case of selective activation of high- and low-affinity kainate receptors, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Reduced glutathione is a major free radical scavenger in the cell body at concentrations within the millimolar range. Levels of reduced glutathione can be monitored with fluorescence probes, such as monochlorobimane, that react with thiol-containing species (Rice et al., 1986). An acute production of radical species shifts reduced glutathione to an oxidized state and thus reduces the fluorescence signal. In oligodendrocyte cultures exposed to AMPA and kainate receptor agonists, we observed that, after 15 min stimulation, monochlorobimane fluorescence decreased in all conditions assayed (range of 5-33% lower than in control, nontreated oligodendrocytes) (Fig. 2C). Only a slight decrease in the level of reduced glutathione was observed at this time point after activation of low-affinity kainate receptors. However, it was more pronounced (23%) and statistically significant at 30 min after stimulation (Fig. 2D).

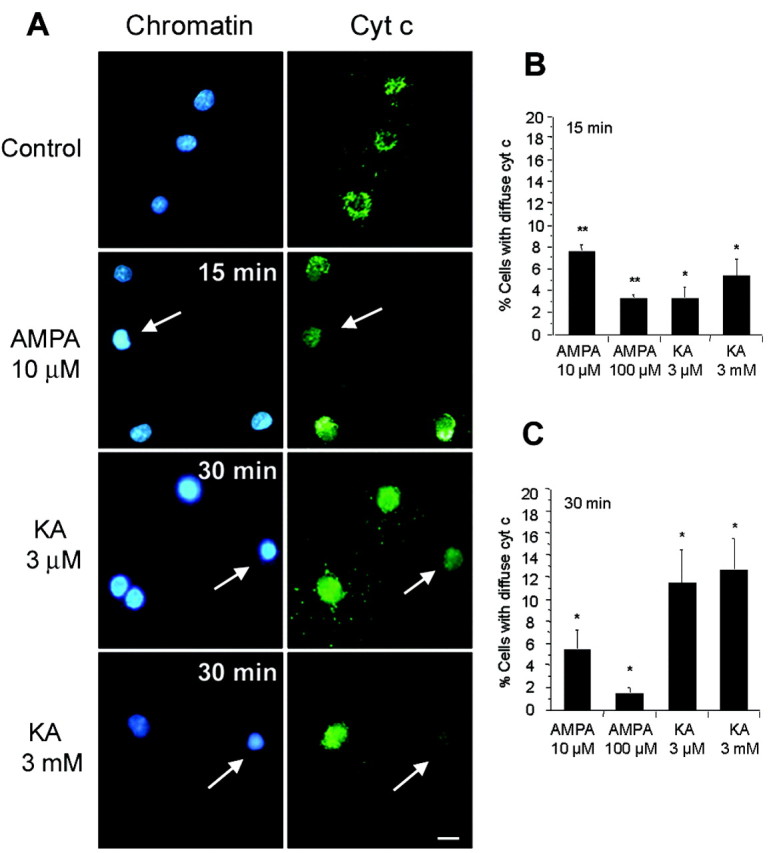

Damage to mitochondria can result in the release of cytochrome c into the cytoplasm, which can be detected immunocytochemically as a transition from a localized punctate-type labeling to a more diffuse-type labeling with antibodies to cytochrome c. In cultures of oligodendrocytes incubated with AMPA or kainate and immunostained with antibodies to cytochrome c (Fig. 3A), we observed punctate immunolabeling in oligodendrocytes with normal-appearing nuclei, consistent with the location of cytochrome c within mitochondria. In contrast, in oligodendrocytes presenting chromatin condensation, diffuse cytoplasmic labeling was observed. These features were not observed when agonists were applied together with CNQX or in the absence of Ca2+ in the culture medium, in accordance with previous findings indicating the lack of excitotoxicity in oligodendrocytes under these conditions (Alberdi et al., 2002). Importantly, both cytochrome c release into the cytoplasm (Fig. 3B,C) and the generation of free radicals (Fig. 2C,D) were observed to occur as early as 15 min after the excitotoxic insult.

Figure 3.

Release of cytochrome c after AMPA and kainate receptor activation in rat oligodendrocytes. Cultures treated with agonists for 15 min were immunostained with antibodies to cytochrome c (green), whereas chromatin was viewed with Hoechst 33258 (blue). A, Diffuse cytochrome c immunolabeling in oligodendrocytes with condensed nuclei (arrows) but not in control (top), at 15-30 min after activation of AMPA receptors, as well as high- and low-affinity kainate receptors. B, C, Diffuse cytochrome c immunostaining was observed under all conditions assayed, indicating that diffusion from mitochondria occurs soon after activation of AMPA and kainate receptors. Histograms represent mean ± SEM of triplicates from three to five different experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA (Fisher's PLSD test). Cyt c, Cytochrome c; KA, kainate. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Together, these results indicate that mitochondrial Ca2+ overload subsequent to AMPA and kainate receptor activation causes profound alterations in the functioning of mitochondria and the release of the proapoptotic factor cytochrome c.

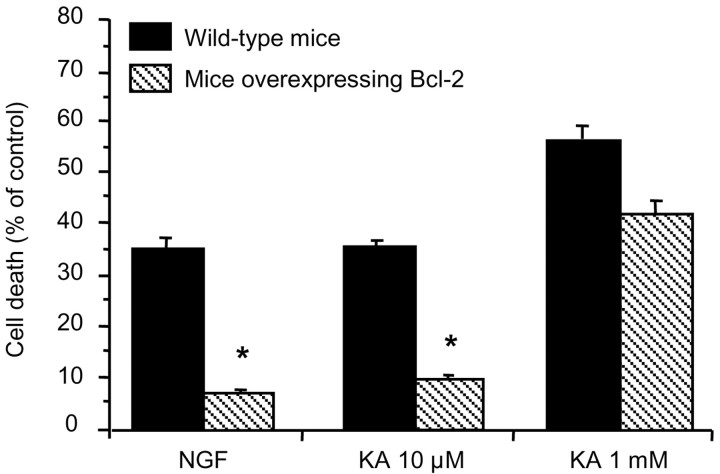

Oligodendrocytes overexpressing Bcl-2 are resistant to mild excitotoxic insults

Because Ca2+ deregulation can lead to apoptotic cell death (for review, see Vajda, 2002), we examined whether oligodendrocytes overexpressing Bcl-2, known to protect against apoptosis, were resistant to excitotoxicity. To this end, we used oligodendrocyte cultures derived from optic nerves of 12-d-old mice overexpressing Bcl-2 and of wild-type mice of the same age. Cell death induced by nerve growth factor (NGF) (100 ng/ml, 4 hr), which is known to induce apoptosis in oligodendrocytes (Casaccia-Bonnefil et al., 1996), was substantially diminished in oligodendrocytes overexpressing Bcl-2 (Fig. 4). Next, we similarly evaluated cell death 24 hr after 15 min application of kainate, a common agonist of AMPA and kainate receptors, at low (10 μm) and high (1 mm) concentrations. We found that oligodendrocytes overexpressing Bcl-2 were resistant to cell death induced by mild (kainate 10 μm) but not by intense (kainate 1 mm) excitotoxic insults (Fig. 4). These results suggest a dual form of oligodendrocyte death by excitotoxicity depending on insult intensity.

Figure 4.

Bcl-2 overexpression prevents oligodendrocyte death by mild excitotoxicity. Cell cultures derived from mouse optic nerves of 12-d-old animals were stimulated with kainate for 15 min, and viable cells were counted 24 hr later. Oligodendrocytes from mice overexpressing Bcl-2 were protected from mild but not severe excitotoxic insults. NGF (100 ng/ml, 4 hr) induced apoptosis was used as a positive control. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3-6). *p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA (Fisher's PLSD test). KA, Kainate.

Mild excitotoxicity can be prevented by caspase inhibitors and induces caspase activation

Mild excitotoxic insults to oligodendrocytes induced cytochrome c release and cell death, which was prevented by Bcl-2 overexpression, suggesting that cells died by apoptosis. To verify this possibility, we evaluated cell death in the presence of specific caspase inhibitors and monitored the activation of major caspases.

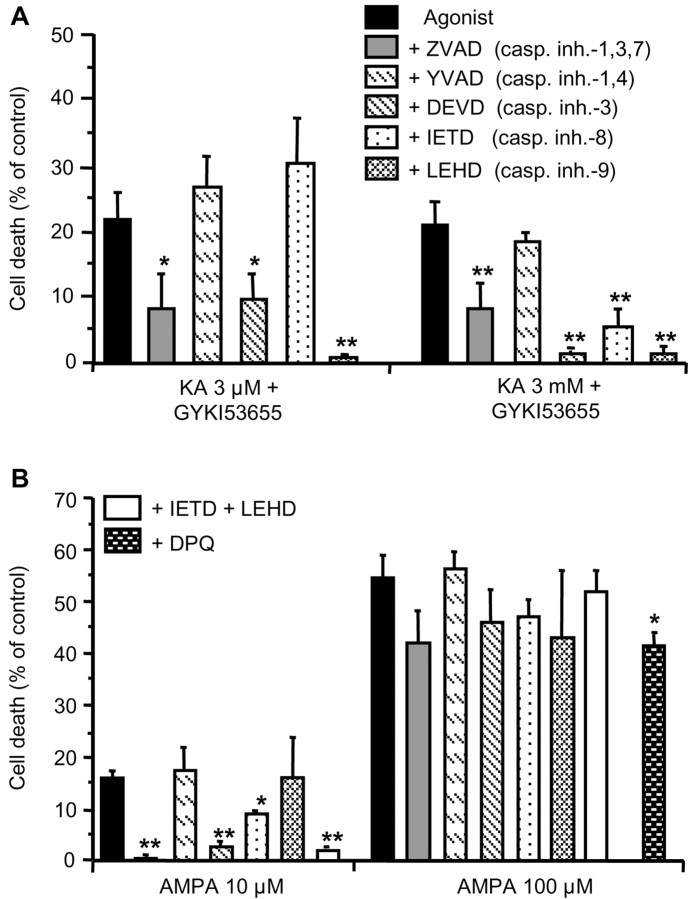

To characterize the caspases that mediate oligodendrocyte death during selective activation of AMPA and kainate receptors, we used site-specific tetrapeptide protease inhibitors that block caspase proteolytic activity (Garcia-Calvo et al., 1998; Thornberry and Lazebnik, 1998). Maximal activation of high- or low-affinity kainate receptors by 3 μm or 3 mm kainate, respectively, caused cell death that was significantly diminished in the presence of the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor ZVAD-F, the selective inhibitors of caspase-3, and the mitochondrial-associated caspase-9 (Fig. 5A). In contrast, activation of AMPA receptors at submaximal concentrations of the agonist (AMPA, 10 μm), applied together with CTZ (100 μm), caused oligodendroglial death that was diminished by inhibitors of caspase-8 and abolished by inhibitors of caspase-3, as well as by the concomitant inhibition of caspase-8 and caspase-9 (Fig. 5B). Thus, excitotoxicity initiated by the activation of kainate receptors and by submaximal activation of AMPA receptors leads to the alteration of mitochondria and the recruitment of apoptotic pathways.

Figure 5.

Caspase and PARP-1 inhibition reduces oligodendrocyte death induced by mild and severe excitotoxic insults, respectively. AMPA and kainate receptors in rat oligodendrocyte cultures were selectively activated for 15 min with AMPA (10 and 100 μm plus 100 μm CTZ) and with kainate (3 μm and 3 mm) in the presence of the AMPA receptor antagonist GYKI53655 (100 μm), respectively. The protective effect of caspase inhibitors (all at 100 μm, except ZVAD at 50 μm) was analyzed 24 hr after agonist stimulation. A, Inhibition of caspase-9 and caspase-3 protects from excitotoxic insults initiated by high- and low-affinity kainate receptors. B, Toxicity caused by AMPA receptors activated at low concentrations of the agonist is abolished by caspase-3 inhibitors and partly prevented by caspase-8 inhibitors. Combination of caspase-8 and caspase-9 inhibitors are fully protective. All inhibitors, except for the PARP-1 inhibitor DPQ, are ineffective after severe insults mediated by AMPA receptors. Cell death values (average ± SEM) are referred to control nontreated cultures (n ≥ 3). Error bars represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared with control. KA, Kainate.

In contrast, maximal activation of AMPA receptors resulted in oligodendroglial death that was independent of caspase activation. To check whether this type of insult causes apoptosis by activation of the nuclear enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1), we use 3,4-dihydro-5-[4-(1-piperidinyl)butoxy]-1(2H)isoquinolinone (DPQ) (30 μm), an inhibitor of PARP-1. We observed that this inhibitor reduced cell death induced by 100 μm AMPA by 24.1 ± 1.9% (Fig. 5B), indicating that activation of PARP-1 contributes to apoptosis as reported for NMDA in neuronal primary cultures (Yu et al., 2002).

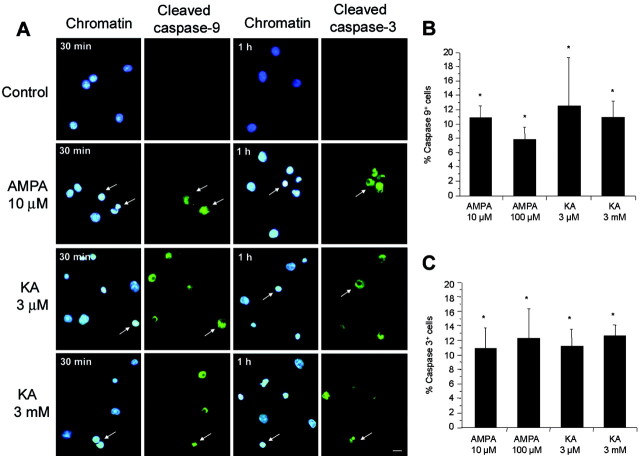

To further confirm the participation of activated caspase-9 and caspase-3 in the events induced by excitotoxic insults to oligodendrocytes in culture, we used immunocytochemistry with antibodies that recognize only the active form of the caspases. As expected, cells treated with AMPA (10 μm) or kainate (3 μm and 3 mm) for 15 min were found to be immunostained with antibodies to both active caspase-9 and caspase-3 (Fig. 6). Thus, caspase-9 labeling was intense at 15-30 min after stimulation in cells with apoptotic features, whereas caspase-3 staining was maximal after 1 hr of treatment in this type of cell.

Figure 6.

Caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation in oligodendrocytes during excitotoxicity. Rat oligodendrocyte cultures treated with agonists for 15 min were immunostained with antibodies to activated caspase-9 or caspase-3 (green), and chromatin was viewed with Hoechst 33258 (blue). A, After activation of glutamate receptors, but not in control cells (top row), caspase-9 and caspase-3 are cleaved (arrows). B, C, Caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation is maximal at 30 and 60 min after stimuli, respectively. Histograms represent mean ± SEM of triplicates from three to five different experiments. *p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA (Fisher's PLSD test). KA, Kainate. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Together, these results indicate that mild excitotoxicity kills oligodendrocytes by apoptosis. The events leading to oligodendrocyte apoptosis induced by excitotoxicity share common features with stress-induced apoptosis in other cell types.

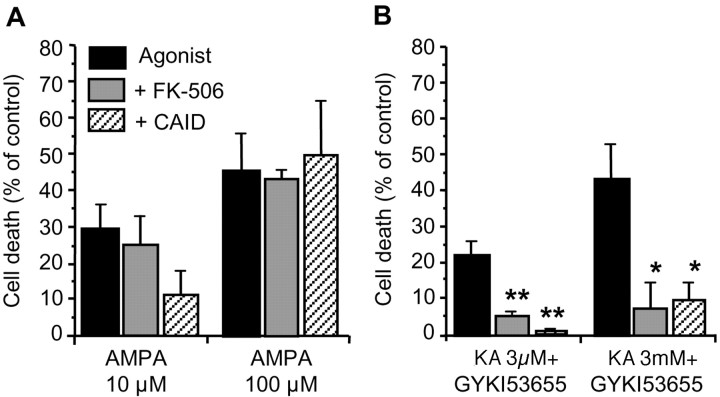

Calcineurin inhibition prevents cell death triggered by kainate but not AMPA receptors

High levels of activity of calcineurin, a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase, predispose cells to cytochrome c/caspase-3-dependent apoptosis by Bad dephosphorylation and its translocation into mitochondria (Asai et al., 1999; Springer et al., 2000). We therefore tested whether oligodendrocyte death initiated by AMPA or kainate receptors could be prevented by inhibitors of this phosphatase. Incubation with FK-506 (1 μm; Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany), an immunosuppresant that inhibits calcineurin activation (Asano et al., 1996), or with a synthetic autoinhibitory peptide (residues 457-482; 50 μm), which binds to the calmodulin-binding domain of calcineurin and inhibits its phosphatase activity (Perrino et al., 1995), reduced nonsignificantly the toxicity of mild insults caused by AMPA receptors but not by those of high intensity (Fig. 7A). In clear contrast, calcineurin inhibition by both agents prevented oligodendrocyte death caused by activation of both high- and low-affinity kainate receptors (Fig. 7B), suggesting that Bad dephosphorylation by calcineurin occurs in kainate receptor-mediated oligodendrocyte death.

Figure 7.

Calcineurin inhibition prevents excitotoxicity by kainate receptors. Rat oligodendrocyte cultures were treated with agonists for 15 min alone or together with FK-506 (1 μm) or with a calcineurin synthetic autoinhibitory peptide (residues 457-482; 50 μm). A, The viability of cells treated with AMPA was not significantly improved by these calcineurin inhibitors, whereas excitotoxicity mediated by kainate receptors of high- and low-affinity was abolished (B). Histograms represent mean ± SEM of triplicates from three to five different experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA (Fisher's PLSD test). CAID, Calcineurin-autoinhibitory domain; KA, kainate.

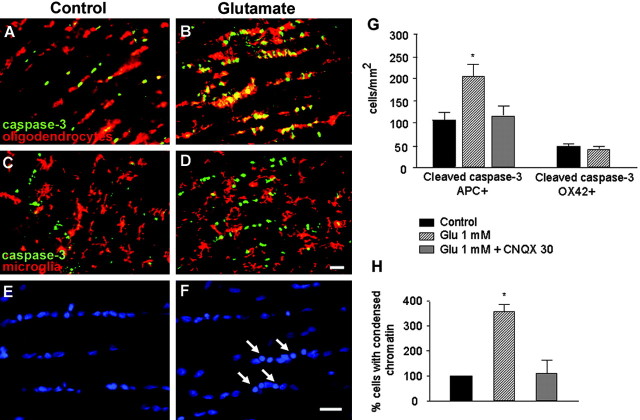

AMPA/kainate receptor activation cleaves caspase-3 in oligodendrocytes in situ

The previous results provide evidence that excitotoxic insults in cultured oligodendrocytes cause cell death by caspase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Next, we investigated whether prolonged glutamate receptor activation is toxic to oligodendrocytes in situ. Isolated adult optic nerves were perfused with oxygen-saturated aCSF, and the presence of activated caspase-3 was assayed by immunohistochemistry. Addition of glutamate (1 mm; 3 hr) to the perfusate caused a sharp increase in the number of caspase-3+ cells compared with controls (Fig. 8). Double immunofluorescence with cell-type markers showed that the vast majority of cells affected by the excitotoxic insult were mature interfascicular oligodendrocytes that were APC + (Fig. 8A,B,G). In contrast, microglial cells (OX42+) were resistant to excitotoxicity (Fig. 8C,D,G), a feature that it is consistent with the lack of glutamate receptors in these cells in their resting stage (García-Barcina and Matute, 1996, 1998). In addition, chromatin condensation was also observed in glutamate-treated nerves (Fig. 8E,F,H). Both caspase-3 activation and chromatin condensation was prevented by CNQX (30 μm), indicating that the associated cell death was specifically triggered by glutamate receptor activation (Fig. 8H).

Figure 8.

Glutamate selectively activates caspase-3 in oligodendrocytes in situ. Whole freshly isolated rat optic nerves were perfused in oxygenated aCSF alone or with glutamate (1 mm) added for 3 hr and processed thereafter for immunofluorescence with rabbit antibodies to cleaved caspase-3 and mouse antibodies APC and OX42 to identify oligodendrocytes and microglia, respectively. A, C, E, Cleaved caspase-3 and chromatin condensation was apparent in a few cells in control nerves. B, D, Treatment with glutamate specifically killed oligodendrocytes (yellow as a result of green and red fluorescence overlap) but not microglia and caused chromatin condensation (F). G, H, Quantification of double-labeled cells in control and in glutamate-treated nerves, as well as in glutamate plus CNQX-exposed optic nerves. Glutamate significantly increased the number of apoptotic oligodendrocytes, but, in the presence of CNQX, the number of oligodendrocytes with cleaved caspase-3 and chromatin condensation returned to control levels. Values (average ± SEM) are from at least four experiments. *p < 0.001; Student's t test. Glu, Glutamate. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Discussion

The results reported here show that oligodendrocyte death initiated by prolonged stimulation of kainate receptors and by submaximal activation of AMPA receptors exhibits some of the principal features of apoptosis, including loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, generation of free radicals, release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol, Bcl-2 protection, activation of initiator and effector caspases, and chromatin condensation. In contrast, maximal activation of AMPA receptors results in oligodendrocyte death that is not prevented by Bcl-2 overexpression or by caspase inhibitors.

Excitotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction in oligodendrocytes

We showed recently that activation of oligodendrocyte AMPA or kainate receptors triggers cell death by Ca2+ influx through the receptor channel complex (Alberdi et al., 2002). The specificity of the Ca2+ entry route that leads to oligodendrocyte death is consistent with the presence of spatially restricted enzyme systems, or cellular microdomains, activated by high local Ca2+ concentrations as proposed for neuronal cell death (Tymianski et al., 1993; Sattler et al., 1999). The current study was undertaken to characterize the molecular events downstream of Ca2+ overload, in the death cascade initiated by AMPA receptors and high- and low-affinity kainate receptors.

The mitochondrion is a critical organelle for Ca2+ buffering in neurons. However, excessive mitochondrial Ca2+ levels are detrimental to cell viability because they can lead to membrane depolarization and the production of free radicals (Schinder et al., 1996; White and Reynolds, 1996). Both brief and prolonged lethal activation of neuronal NMDA receptors involves an abrupt and persistent depolarization of mitochondria, suggesting that early mitochondrial damage is a critical event in excitotoxicity (Schinder et al., 1996; White and Reynolds, 1996). Likewise, brief AMPA and kainate receptor activation elicited a drastic increase in [Ca2+]i (2- to 50-fold, depending on the activated receptor and the intensity of the stimulus), the bulk of which was rapidly sequestered into mitochondria, resulting in attenuation of the mitochondrial membrane potential.

Excessive Ca2+ influx and mitochondrial depolarization in oligodendrocytes was found to be accompanied by an increase in the production of radical oxygen species, which correlated with a decrease in the levels of reduced glutathione. A similar process has been reported to occur in neurons in which the elevation of cytosolic [Ca2+] subsequent to NMDA receptor activation provokes a rise in mitochondrial [Ca2+], depolarization of this organelle, an increased rate of free radical generation, and damage to the respiratory chain (Dugan et al., 1995; Peng and Greenamyre, 1998; Votyakova and Reynolds, 2001). In addition to NMDA receptors, highly Ca2+-permeable AMPA and kainate receptors in neurons may cause mitochondrial depolarization, concomitant free radical formation, and cell death in motor neurons (Carriedo et al., 2000). In all of the aforementioned instances, the generation of free radicals contributed to irreversible neuronal damage (Stout et al., 1998; Nicholls and Budd, 2000); in the present study, free radical generation was found to be associated with irreversible damage to oligodendrocytes.

Increased levels of free radicals and calcium overload in mitochondria lead to the opening of the permeability transition pore (Nicholls and Budd, 2000), a hypothesized megachannel lying in the inner mitochondrial membrane that regulates exit to the cytoplasm of cytochrome c and other proapoptotic substances (Zamzami and Kroemer, 2001). The opening of this pore is under the control of members of the Bcl-2 protein family, and overexpression of Bcl-2 blocks apoptosis induced by a wide variety of stimuli (Nicholls and Budd, 2000). Consistently, we observed that oligodendrocytes overexpressing Bcl-2 were resistant to mild excitotoxic insults but not to severe stimuli, which suggests that, at least in the former conditions, apoptosis is the major mode of cell death.

Bcl-2 has multiple sites of action and can block apoptosis by inhibition of cytochrome c release, by inhibiting procaspase-3, or by regulating free radical levels (Rossé et al., 1998; Krebs et al., 1999; Kirkland and Franklin, 2001). It is not clear at present how Bcl-2 overexpression protects oligodendrocytes from mild excitotoxicity. However, the fact that the three events occur under conditions of mild excitotoxicity suggests that Bcl-2 may participate in the three mentioned processes.

Cytochrome c is a highly conserved protein that plays a crucial role in the electron transport chain. As cytochrome c is progressively released from depolarized mitochondria, electron transfer from complex III to complex IV becomes restricted (Nicholls and Budd, 2000). To monitor cytochrome c release from mitochondria, we used immunofluorescence and found that loss of punctate, mitochondrially located cytochrome c starts as early as 15-30 min and is completed by 2 hr after excitotoxic insults initiated at AMPA receptors (at submaximal activation) and by kainate receptors. The time course of cytochrome c release observed in our experimental paradigm is comparable with that observed in other cells undergoing apoptosis (Yu et al., 2002).

Caspase-dependent and caspase-independent oligodendrocyte death

Cytochrome c, when released from the mitochondria, interacts with Apaf-1 and initiates the caspase cascade (Li et al., 1997). Apaf-1 binds procaspase-9, initiating its cleavage to active protease, which in turn cleaves and activates caspase-3. Inhibitors of caspase-9 or caspase-3 protected against oligodendroglial excitotoxicity initiated by kainate receptors of both high and low affinity, thus indicating that insults mediated by these receptors activate the Apaf-1 cascade to apoptosis. In contrast, blockade of cell death by submaximal activation of AMPA receptors requires inhibition of both caspase-9 and caspase-8, which suggests that mediators of both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathway are activated. Together, these results are consistent with the consensus that submaximal activation of neuronal NMDA and AMPA receptors can induce apoptosis (Bonfoco et al., 1995; Larm et al., 1997; Tenneti et al., 1998).

Oligodendrocyte death triggered by maximal activation of AMPA receptors is not prevented by inhibitors of the principal caspases, as observed in neurons (Du et al., 1997). This finding would suggest that cell death under these conditions was necrotic rather than apoptotic in nature. However, the recent finding that cell death induced by apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) (Yu et al., 2002) is caspase independent but PARP-1 dependent suggests that this may not necessarily be the case. AIF released from mitochondria promotes the release of cytochrome c from this organelle and translocates to the nucleus, in which it induces lysis of chromatin and cell death, a biochemical cascade that does not occur in PARP-1 knock-out mice (Yu et al., 2002). Interestingly, ∼25% of oligodendrocytes vulnerable to severe insults mediated by AMPA receptors were rescued from dying by inhibition of PARP, suggesting that severe excitotoxicity can kill oligodendrocytes by both apoptosis and necrosis.

Apoptotic cell death mediated by kainate receptors, but not by AMPA receptors, involved activation of calcineurin. Thus, Ca2+ influx triggered by kainate receptors and the subsequent activation of calcineurin may dephosphorylate proapoptotic Bad upstream of its interaction with the 14-3-3 adapter protein. Bad dephosphorylation facilitates its association with Bcl-xL and thus counteracts the anti-apoptotic effects of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl (Yang et al., 1995; Zha et al., 1996). Calcineurin recruitment in the death cascade initiated by kainate but not AMPA receptors indicates that distinct apoptotic pathways are associated with the excitotoxic activation of AMPA and kainate receptors.

Oligodendrocyte death by excitotoxicity may be relevant to acute and chronic damage to white matter

Excitotoxic neuronal death is associated with acute injury and chronic neurodegenerative diseases of the CNS (Choi, 1988; Lipton and Rosenberg, 1994). Likewise, the vulnerability of oligodendrocytes to excitotoxic insults suggests that enhanced glutamate signaling may contribute to white matter damage after stroke and to oligodendrocyte loss in chronic demyelinating diseases, including multiple sclerosis (Matute et al., 2001; Goldberg and Ransom, 2003). Thus, AMPA/kainate antagonists preserve white matter function in brain slice models (Li and Stys, 2000; Tekkok and Goldberg, 2001) and reduce white matter injury in spinal cord ischemia (Kanellopoulos et al., 2000), as well as in transient focal cerebral ischemia (McCracken et al., 2002). In addition, recent studies suggest that AMPA/kainate receptor-mediated excitotoxicity may be a common pathway for white matter injury in several conditions, including perinatal ischemia (Follett et al., 2000) and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (Pitt et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2000), a model of multiple sclerosis. However, it is not clear at present how oligodendocytes die in white matter diseases. The results reported here define molecular events leading to oligodendrocyte death after excitotoxic insults mediated by AMPA and kainate receptors.

In conclusion, the evidence presented here indicates that caspase-dependent and -independent mechanisms mediate oligodendrocyte death by excitotoxicity. A thorough understanding of the events that mediate oligodendrocyte death downstream of receptor activation may prove to be of therapeutical value in the treatment white matter of damage in acute and chronic neurological disorders.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, La Caixa, Gobierno Vasco, and the University of País Vasco. E.A. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow, and G.I. and I.T. are supported by the Gobierno Vasco. We thank Dr. D. Leander (Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN) for providing GYKI 53655 and M. Dubois-Dauphin for the supply of Bcl-2 protein overexpressing mice. We are also grateful to Dr. D. J. Fogarty for reviewing this manuscript and Dr. F. Vidal Vanaclocha for providing access to equipment in his laboratory.

Correspondence should be addressed to Carlos Matute, Departamento de Neurociencias, Universidad del País Vasco, Barrio de Sarriena s/n, 48940 Leioa, Spain. E-mail: onpmaalc@lg.ehu.es.

Copyright © 2003 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/03/239519-10$15.00/0

References

- Alberdi E, Sánchez-Gómez MV, Marino A, Matute C ( 2002) Ca2+ influx through AMPA or kainate receptors alone is sufficient to initiate excitotoxicity in cultured oligodendrocytes. Neurobiol Dis 9: 234-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai A, Qiu J, Narita Y, Chi S, Saito N, Shinoura N, Hamada H, Kuchino Y, Kirino T ( 1999) High level calcineurin activity predisposes neuronal cells to apoptosis. J Biol Chem 274: 34450-34458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano K, Taki M, Matsuo S, Yamada K ( 1996) Mode of action of FK-506 on protective immunity to Hymenolepis nana in mice. In Vivo 10: 537-545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM ( 1999) Apoptosis control by death and decoy receptors. Curr Opin Cell Biol 11: 255-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres BA, Hart IK, Coles HS, Burne JF, Voyvodic JT, Richardson WD, Raff MC ( 1992) Cell death and control of cell survival in the oligodendrocyte lineage. Cell 70: 31-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfoco E, Krainc D, Ankarcrona M, Nicotera P, Lipton SA ( 1995) Apoptosis and necrosis: two distinct events induced respectively by mild and intense insults with NMDA or nitric oxide/superoxide in cortical cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 7162-7166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candé C, Cohen I, Daugas E, Ravagnan L, Larochette N, Zamzami N, Kroemer G ( 2002) Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF): a novel caspase-independent death effector released from mitochondria. Biochimie 84: 215-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriedo SG, Sensi SL, Yin HZ, Weiss JH ( 2000) AMPA exposures induce mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and ROS generation in spinal motorneurons in vitro J Neurosci 20: 240-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaccia-Bonnefil P, Carter BD, Dobrowsky RT, Chao MV ( 1996) Death of oligodendrocytes mediated by the interaction of nerve growth factor with its receptor p75. Nature 383: 716-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW ( 1988) Glutamate neurotoxicity and diseases of the nervous system. Neuron 1: 623-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW ( 1995) Calcium: still center-stage in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Trends Neurosci 18: 58-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW, Rothman SM ( 1990) The role of glutamate neurotoxicity in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Annu Rev Neurosci 13: 171-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Bales KR, Dodel RC, Hamilton-Byrd E, Horn JW, Czilli DL, Simmons LK, Ni B, Paul SM ( 1997) Activation of a caspase-3 related cysteine protease is required for glutamate-mediated apoptosis of cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 11657-11662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan LL, Sensi SL, Canzoniero LMT, Handran SD, Rothman SM, Lin TS, Goldberg MP, Choi DW ( 1995) Mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species in cortical neurons following exposure to NMDA. J Neurosci 15: 6377-6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follett PL, Rosenberg PA, Volpe JJ, Jensen FE ( 2000) NBQX attenuates excitotoxic injury in developing white matter. J Neurosci 20: 9235-9241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Barcina J, Matute C ( 1996) Expression of kainate-selective glutamate receptor subunits in glial cells of the adult bovine white matter. Eur J Neurosci 8: 2379-2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Barcina J, Matute C ( 1998) AMPA-selective glutamate receptor subunits in glial cells of the adult bovine white matter. Mol Brain Res 53: 270-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Calvo M, Peterson EP, Leiting B, Ruel R, Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA ( 1998) Inhibition of human caspases by peptide-based and macromolecular inhibitors. J Biol Chem 273: 32608-32613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MP, Ransom BR ( 2003) New light on white matter. Stroke 34: 330-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ ( 1999) BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev 13: 1899-1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewikcz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY ( 1985) A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440-3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner MO ( 2000) The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature 407: 770-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KH, Senft JA ( 1985) An improved method to determine cell viability by simultaneous staining with fluorescein diacetate-propidium iodide. J Histochem Cytochem 33: 77-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanellopoulos GK, Xu XM, Hsu CY, Lu X, Sundt TM, Kouchoukos NT ( 2000) White matter injury in spinal cord ischemia: protection by AMPA/kainate glutamate receptor antagonism. Stroke 31: 1945-1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland RA, Franklin JL ( 2001) Evidence for redox regulation of cytochrome c release during programmed neuronal death: antioxidant effects of protein synthesis and caspase inhibition. J Neurosci 21: 1949-1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs JF, Armstrong RC, Srinivasan A, Aja T, Wong AM, Aboy A, Sayers R, Pham B, Vu T, Hoang K, Karanewsky DS, Leist C, Schmitz A, Wu JC, Tomaselli KJ, Fritz LC ( 1999) Activation of membrane-associated procaspase-3 is regulated by Bcl-2. J Cell Biol 144: 915-926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larm JA, Cheung NS, Beart PM ( 1997) Apoptosis induced via AMPA-selective glutamate receptors in cultured murine cortical neurons. J Neurochem 69: 617-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassus P, Opitz-Araya X, Lazebnik Y ( 2002) Requirement for caspase-2 in stress-induced apoptosis before mitochondrial permeabilization. Science 297: 1352-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaz G, Bovina C, D'Aurelio M, Fato R, Formiggini G, Genova ML, Giuliano G, Pich MM, Paolucci U, Castelli GP, Ventura B ( 2002) Role of mitochondria in oxidative stress and aging. Ann NY Acad Sci 959: 199-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Znu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J ( 1998) Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell 94: 491-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, Wang X ( 1997) Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell 91: 479-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Stys PK ( 2000) Mechanisms of ionotropic glutamate receptor-mediated excitotoxicity in isolated spinal cord white matter. J Neurosci 20: 1190-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA, Rosenberg PA ( 1994) Excitatory amino acids as a final common pathway for neurologic disorders. N Engl J Med 330: 613-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden VS, O'Connor L, O'Reilly LA, Silke J, Metcalf D, Ekert PG, Huang DCS, Cecconi F, Kuida K, Tomaselli KJ, Roy S, Nicholson DW, Vaux DL, Bouillet P, Adams JM, Strasser A ( 2002) Apoptosis initiated by Bcl-2-regulated caspase activation independently of the cytochrome c/Apaf-1/caspase-9 apoptosome. Nature 419: 634-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinou JC, Dubois-Dauphin M, Staple JK, Rodriguez I, Frankowski H, Missotten M, Albertini P, Talabot D, Catsicas S, Pietra C ( 1994) Overexpression of BCL-2 in transgenic mice protects neurons from naturally occurring cell death and experimental ischemia. Neuron 13: 1017-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute C ( 1998) Characteristics of acute and chronic kainate excitotoxic damage to the optic nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 10229-10234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute C, Sánchez-Gómez MV, Martínez-Millán L, Miledi R ( 1997) Glutamate receptor-mediated toxicity in optic nerve oligodendrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 8830-8835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute C, Alberdi E, Domercq M, Perez-Cerdá F, Perez-Samartín A, Sánchez-Gómez MV ( 2001) The link between excitotoxic oligodendroglial death and demyelinating diseases. Trends Neurosci 24: 224-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken E, Fowler JH, Dewar D, Morrison S, McCulloch J ( 2002) Grey matter and white matter ischemic damage is reduced by the competitive AMPA receptor antagonist, SPD 502. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22: 1090-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JW, Althomsons SP, Hyrc KL, Choi DW, Goldberg MP ( 1998) Oligodendrocytes from forebrain are highly vulnerable to AMPA/kainate receptor-mediated excitotoxicity. Nat Med 4: 291-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DG, Budd SL ( 2000) Mitochondria and neuronal survival. Physiol Rev 80: 315-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotera P, Lipton SA ( 1999) Excitotoxins in neuronal apoptosis and necrosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 19: 583-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, Sharpe LG ( 1969) Brain lesions in an infant rhesus monkey treated with monosodium glutamate. Science 166: 386-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang YB, Tan Y, Comb M, Liu CL, Martone ME, Siesjo BK, Hu BR ( 1999) Survival- and death-promoting events after transient cerebral ischemia: phosphorylation of Akt, release of cytochrome C and activation of caspase-like proteases. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 19: 1126-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paternain AV, Morales M, Lerma J ( 1995) Selective antagonism of AMPA receptors unmask kainate receptor-mediated responses in hippocampal neurons. Neuron 14: 185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng TI, Greenamyre J ( 1998) Privileged access to mitochondria of calcium influx through NMDA receptors. Mol Pharmacol 53: 974-980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino BA, Ng LY, Soderling TR ( 1995) Calcium regulation of calcineurin phosphatase activity by its B subunit and calmodulin. Role of the autoinhibitory domain. J Biol Chem 270: 340-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt D, Werner P, Raine CS ( 2000) Glutamate excitotoxicity in a model of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med 6: 67-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice GC, Bump EA, Shrieve DC, Lee W, Kovacs M ( 1986) Quantitative analysis of cellular glutathione by flow cytometry utilizing monochlorobimane: some applications to radiation and drug resistance in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res 46: 6105-6110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossé T, Olivier R, Monney L, Rager M, Conus S, Fellay I, Jansen B, Borner C ( 1998) Bcl-2 prolongs cell survival after Bax-induced release of cytochrome c. Nature 391: 496-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gómez MV, Matute C ( 1999) AMPA and kainate receptors each mediate excitotoxicity in oligodendroglial cultures. Neurobiol Dis 6: 475-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R, Xiong Z, Lu WY, Hafner M, MacDonald JF, Tymianski M ( 1999) Specific coupling of NMDA receptor activation to nitric acid neurotoxicity by PSD-95 protein. Science 284: 1845-1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinder AF, Olson EC, Spitzer NC, Montal M ( 1996) Mitochondrial dysfunction is a primary event in glutamate toxicity. J Neurosci 16: 6125-6133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Groom A, Zhu B, Turski L ( 2000) Autoimmune encephalomyelitis ameliorated by AMPA antagonists. Nat Med 6: 62-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer JE, Azbil RD, Nottingham SA, Kennedy SE ( 2000) Calcineurin-mediated BAD dephosphorylation activates caspase-3 apoptotic cascade in traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 20: 7246-7251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout AK, Raphael HM, Kanterewicz BI, Klann E, Reynolds IJ ( 1998) Glutamate-induced neuron death requires mitochondrial calcium uptake. Nat Neurosci 1: 366-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekkok SB, Goldberg MP ( 2001) AMPA/kainate receptor activation mediates hypoxic oligodendrocyte death and axonal injury in cerebral white matter. J Neurosci 21: 4237-4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenneti L, D'Emilia DM, Troy CM, Lipton SA ( 1998) Role of caspases in N-methyl-d-aspartate-induced apoptosis of cerebro-cortical neurons. J Neurochem 71: 946-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y ( 1998) Caspases: enemies within. Science 281: 1312-1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tymianski M, Charlton MP, Carlen PL, Tator CH ( 1993) Source specificity of early calcium neurotoxicity in cultured embryonic spinal neurons. J Neurosci 13: 2085-2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vajda FJ ( 2002) Neuroprotection and neurodegenerative disease. J Clin Neurosci 9: 4-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A, Steinhäuser C ( 2000) Ion channels in glial cells. Brain Res Rev 32: 380-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votyakova TV, Reynolds IJ ( 2001) DeltaPsi(m)-dependent and -independent production of reactive oxygen species by rat brain mitochondria. J Neurochem 79: 266-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Reynolds IJ ( 1996) Mitochondrial depolarisation in glutamate-stimulated neurons: an early signal specific to excitotoxin exposure. J Neurosci 16: 5688-5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E, Zha J, Jockel J, Boise LH, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ ( 1995) Bad, a heterodimer partner for Bcl-xl and Bcl-2, displaces Bax and promotes cell death. Cell 80: 285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka A, Bacskai B, Pleasure D ( 1996) Pathophysiology of oligodendroglial excitotoxicity. J Neurosci Res 46: 427-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S-W, Wang H, Poitras MF, Coombs C, Bowers WJ, Federoff HJ, Poirier GG, Dawson TM, Dawson VL ( 2002) Mediation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cell death by apoptosis-inducing factor. Science 297: 259-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamzami N, Kroemer G ( 2001) The mitochondrion in apoptosis: how Pandora's box opens. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 67-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer SJ ( 1996) Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-Xl. Cell 87: 619-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]