Abstract

Astrocytes express transient receptor potential channels (TRPCs), which have been implicated in Ca 2+ influx triggered by intracellular Ca 2+ stores depletion, a phenomenon known as capacitative Ca 2+ entry. We studied the properties of capacitative Ca 2+ entry in astrocytes by means of single-cell Ca 2+ imaging with the aim of understanding the involvement of TRPCs in this function. We found that, in astrocytes, capacitative Ca 2+ entry is not attributable to TRPC opening because the TRPC-permeable ions Sr2+ and Ba2+ do not enter astrocytes during capacitative Ca 2+ entry. Instead, natively expressed oleyl-acetyl-glycerol (OAG) (a structural analog of DAG) -sensitive TRPCs, when activated, initiate oscillations of cytosolic Ca 2+ concentration ([Ca 2+]i) pharmacologically and molecularly consistent with TRPC3 activation. OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations are not affected by inhibition of inositol trisphosphate (InsP3) production or blockade of the InsP3 receptor, therefore representing a novel form of [Ca 2+]i signaling. Instead, high [Ca 2+]i inhibited oscillations, by closing the OAG-sensitive channel. Also, treatment of astrocytes with antisense against TRPC3 caused a consistent decrease of the cells responding to OAG. Exogenous OAG but not endogenous DAG seems to activate TRPC3. In conclusion, in glial cells, natively expressed TRPC3s mediates a novel form of Ca 2+ signaling, distinct from capacitative Ca 2+ entry, which suggests a specific signaling function for this channel in glial cells.

Keywords: astrocyte, transient receptor potential channel, store-operated Ca 2+ channels, [Ca 2+]i oscillations, capacitative Ca 2+ entry, C6 glioma cells

Introduction

Since the original description of Ca 2+ entry triggered by depletion of intracellular Ca 2+ stores (Putney, 1986), progress has been slow to identify the plasma-membrane channels involved in this phenomenon. Transient receptor potential channels (TRPCs), a family of relatively nonselective divalent cation channels, have been proposed as the molecular entity associated with store-operated Ca 2+ channel activity (Zhu et al., 1996). Several reports have shown functional similarities between storeoperated Ca 2+ channels and TRPCs, especially the type-3 TRPC (TRPC3) (Zhu et al., 1996; Vazquez et al., 2001; Montell et al., 2002). Both store-operated Ca 2+ channels and TRPCs may be operated through a physical link with the inositol trisphosphate (InsP3) receptor and/or by InsP3 itself (Ma et al., 2000; Vazquez et al., 2001). Several alternative or complementary TRPC operation models are still under investigation (Putney et al., 2001). However, recent studies also point out substantial differences between the properties of store-operated Ca 2+ channels and TRPCs (Montell et al., 2002).

Little is known about capacitative Ca 2+ entry, store-operated Ca 2+ channels, or TRPC function in the Ca 2+ homeostasis of type I astrocytes. In this study, we analyzed the properties and the behavior of capacitative Ca 2+ entry in type I astrocytes and C6 glioma cells, with the aim of clarifying the role of natively expressed TRPCs in this phenomenon. We were able to pharmacologically distinguish store-operated Ca 2+ channel function from TRPC activity. Furthermore, we identified a possible role for oleyl-acetyl-glycerol (OAG)-sensitive TRPC activation in the generation of a novel form of astrocytic [Ca 2+]i oscillations.

Materials and Methods

Cell cultures. Type I astrocyte cultures were obtained from embryonic day 17 rats according to a published protocol (Grimaldi et al., 1994). Briefly, fetuses were obtained by cesarean section from a 17 d pregnant Wistar rat and quickly decapitated. The heads were placed in PBS (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD) containing 4.5 gm/l glucose at room temperature. Cerebral cortices were dissected, minced, and enzymatically digested with papain. The tissue fragments were then mechanically dissociated. The cells in suspension were counted and plated in 25cm 2 flasks (106 cells per flask). The culture medium (DMEM, high glucose) was changed after 6–8 hr to wash away unattached cells. Subsequently, the medium was changed every 2 d. This yielded cultures consisting of >95% type I astrocytes as characterized by glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoreactivity (Grimaldi et al., 1999). C6 glioma cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), amplified, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Thawed cells retained functional characteristics for up to 25 passages, and then they were discarded. C6 glioma cells were maintained in high-glucose DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT) and penicillin–streptomycin. Subcultures were obtained by trypsin–EDTA exposure.

Single cell [Ca 2+]imeasurements. Nearly confluent type I astrocytes and C6 glioma cells were seeded onto 1.5-cm-diameter glass coverslips (Assistent, Sondheim/Rhön, Germany). Before the experiment, cells were washed once in Krebs'–Ringer's buffer (KRB) containing the following (in mm): 125 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 Na2HPO4, 1 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2 1, 5.5 glucose, and 20 HEPES, pH 7.3. They were then loaded with 4 μm fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 22 min at room temperature under continuous gentle agitation. After loading, cells were washed once with fresh KRB and then incubated for an additional 22 min in KRB without fura-2 AM, according to a previously published protocol (Grimaldi et al., 1999). Finally, the coverslips were mounted on a lowvolume, self-built 150 μl perfusion chamber and placed on an inverted microscope equipped with a 40× lens and a CCD video camera. Preparations were perfused with KRB through a peristaltic pump at ∼800 μl/min. Ca 2+-free solutions were prepared by omitting Ca 2+ from the KRB and including 100 μm EGTA. Ratio measurements were performed every 2 sec by collecting image pairs exciting the preparations at 340 and 380 nm, respectively. The excitation wavelengths were changed through a high-speed mechanical filter changer, and the emission wavelength was set at 510 nm. The captured images were digitized using an acquisition board and analyzed by using commercially available software. Ratio values were derived from the entire cytosolic area, obtained by delimiting the profile of the cells and averaging the signal within the delimited area, and were converted into [Ca 2+]i using the equation described by Grynkiewicz et al. (1985). Fmax in astrocytes and in C6 was obtained exposing cells to 10 μm ionomycin in 10 mm extracellular Ca 2+. Fmin was obtained with a Ca 2+-free solution containing 1 mm EDTA.

Reverse transcription-PCR. Primers to the six isoforms of TRPC1–TRPC6 and to β-actin were designed according to published sequences (Pizzo et al., 2001). RNA was extracted from type I astrocytes and C6 using the RNAeasy Qiagen Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and quantified by spectrometry. Total RNA (1 μg) was added to the reaction mixture containing two sets of primers, one for the specific TRPC and the other for β-actin. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR amplifications were performed using the Superscript One-Step RT-PCR with Platinum Taq Kit (Qiagen). Forty amplification cycles were conducted with denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, annealing at 57°C for 30 sec, and extension at 70°C for 1 min. Results were expressed as ratio of TRPC product to β-actin.

Antisense oligonucleotides were designed on the basis of the sequence specificity. We synthesized an antisense on the basis of the primers used for the PCR, specific for the isoform TRPC3. We also synthesized fluoresceinate antisense, sense, and scrambled oligonucleotides. Astrocytes were treated with 100 μg/ml antisense, sense, or scrambled oligonucleotides and with fluoresceinate antisense to control for uptake. After ∼2 hr of treatment, fluorescence was discretely accumulated within astrocytes in hot spots. Cells were treated with the oligonucleotides in the presence of serum for 36 hr, and loaded with fura-2, and then exposed to OAG.

Western blot. Proteins were extracted from type I astrocytes and C6 glioma cells using the Protease Arrest kit (Geno Technology, St. Louis, MO). Protein content of the samples was quantified using the Bradford assay (Bradford, 1976). Protein samples (100 μg) were prepared for SDSPAGE using the PAGE perfect kit (Geno Technology), mixed with 2× Laemmli buffer containing 100 mm dithiotretiol, and then heated at 70°C for 30 min. Protein extract (100 μg) were loaded in each lane of a 12–4% gradient gel and separated. Electrophoresed proteins were transferred and immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were exposed to 5% nonfat dry milk to block unspecific binding sites. Immunoblots with anti-TRPC3 or TRP4 antibodies (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) were conducted using a 1:200 dilution overnight, according to the instructions of the manufacturer, at room temperature. After washing the membranes, bound primary antibody was detected by exposing the filter to ImmunoPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (Pierce, Rockford, IL) at a 1:2500 dilution for 6 hr at room temperature. The SuperSignal Enhanced Chemiluminescence kit (Pierce) was used to visualize immunoreactive bands.

Immunocytochemistry and confocal analysis of TRPC3 and TRPC4 localization. Type I astrocytes and C6 cells seeded on coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were incubated with primary antibody to TRPC3 and TRPC4, at 1:25 dilution, for 4 hr at room temperature (Alomone Labs). Preparations were washed several times in PBS. Secondary FITC-conjugated antibody at 1:200 dilution was incubated for 1 hr at room temperature. Preparations were washed several times in PBS. Coverslips were mounted using Immunomount containing the antifade agent DABCO (1,4-diazabicyclo-[2.2.2]octane). Preparations were observed with an inverted microscope using 40× oil immersion high numerical aperture Olympus Optical (Tokyo, Japan) lens. Images were enlarged using the optical zoom of the microscope; therefore, final magnification was 60×. Images were digitized using commercially available software.

Materials. All materials were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise specified in the text.

Use of laboratory animals. Adequate measures were taken to minimize unnecessary pain and discomfort to the animals and to minimize animal use according to NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Pregnant animals were killed by exposure to CO2 according to approved protocols.

Statistical analyses. Experiments were performed at least three times on different cell preparations. For [Ca 2+]i measurements, digital images were converted to analog data and imported to a spreadsheet. The numbers generated, representing the [Ca 2+]i determined every 2 sec, were averaged and SEs were calculated. Plots represent the average ± SE of all of the cells studied. In studies on [Ca 2+]i oscillations, graphs display representative cells, and frequency analysis of the population is displayed in an associated bar graph. When statistical validation was required, the values of the specified data points were analyzed by ANOVA, followed by Student's t test and shown as a bar inset. Differences were considered statistically significant when the p < 0.05. For experiments based on all-or-none responses, such as the one on the percentage of responding cells, a different statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon ranked test, which allows determining statistical significance in this type of response.

Results

Store-operated Ca 2+ channels in type I astrocytes and in C6 cells do not exhibit TRPC properties

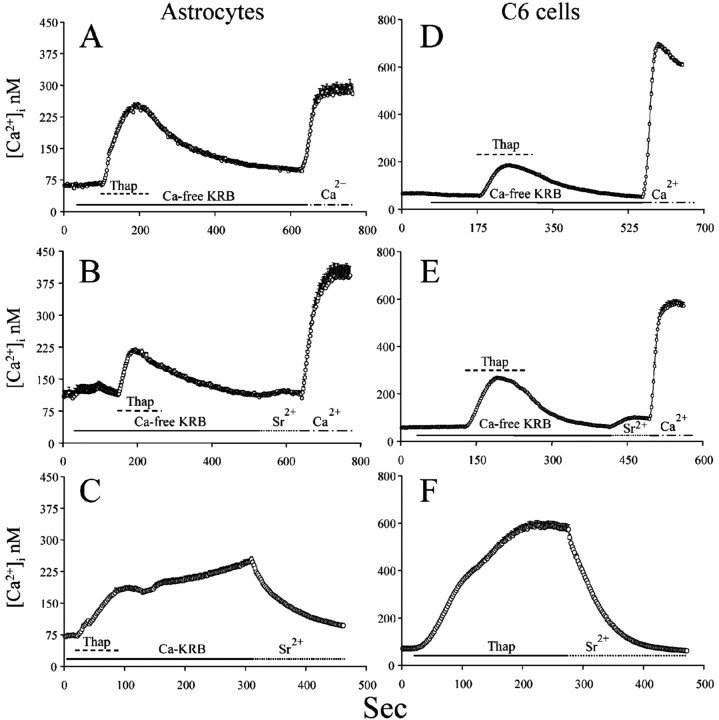

We depleted intracellular Ca 2+ stores by exposure to 2 μm thapsigargin, an irreversible inhibitor of the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca 2+ ATPase (SERCA) (Thastrup et al., 1989), in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+. After an initial rise, [Ca 2+]i requilibrated to baseline levels. When extracellular Ca 2+ was reintroduced to initiate capacitative Ca 2+ entry, a rapid and sustained elevation of [Ca 2+]i was detected in both astrocytes and C6 cells (Fig. 1A,D).

Figure 1.

Depletion of intracellular Ca 2+ stores achieved via exposure to thapsigargin is not associated with the opening of TRPC.A,D, Astrocytes and C6 were exposed to 2 μm thapsigargin (Thap) in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+ to deplete intracellular Ca 2+ stores, after which cells were reperfused with 1 mm extracellular Ca 2+ to initiate capacitative Ca 2+ entry. In both celltypes, initiation of capacitative Ca 2+entry generated a consistent elevation of[Ca 2+]ithat was larger in C6 than in astrocytes. B, E, Astrocytes and C6, respectively, were exposed to 2 μm thapsigargin. When intracellular Ca 2+ stores depletion was complete, 1 mm Sr 2+ was introduced in the extracellular solution. In both astrocytes and C6, very little Sr 2+ entered the cells during capacitative Ca 2+ entry. Successively, Sr 2+ was replaced with Ca 2+ to check that capacitative Ca 2+ entry was still activated in this condition. C, F, Astrocytes and C6, respectively, were exposed to 2 μm thapsigargin in the presence of 1 mm extracellular Ca 2+. When [Ca 2+]i elevation reached a plateau and stabilized, extracellular Ca 2+ was replaced by 1 mm Sr 2+. Capacitative Ca 2+ entry was promptly terminated, indicating that Sr 2+ is an antagonist of the store-operated Ca 2+ channels (note that, to ease readability, values are reported as calibrated Ca 2+ values even when Sr 2+ is present).

Store-operated Ca 2+ channels are highly selective (Hoth and Penner, 1992; Parekh and Penner, 1997), whereas TRPCs are less selective and also permeable to the larger Sr2+ and Ba2+ cations (Hoth and Penner, 1992; Estacion et al., 1999). Like Ca 2+, both Sr2+ and Ba2+ increase the ratio signal of fura-2 by, during binding to the probe, decreasing fluorescence emission at 510 nm when excitation is set at 380 nm and increasing the fluorescence emission at 510 nm when excitation is set at 340 nm (Kwan and Putney, 1990). After depleting intracellular Ca 2+ stores with thapsigargin, in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+, we perfused cells with 1 mm Sr2+ instead of 1 mm Ca 2+. Sr2+ treatment did not cause elevation of fura-2 fluorescence ratio in either astrocytes or C6 cells, indicating that TRPCs are not open during capacitative Ca 2+ entry (Fig. 1B,E). When we switched from 1 mm Sr2+ to 1 mm Ca 2+ extracellularly, we observed a robust [Ca 2+]i elevation, which indicated that capacitative Ca 2+ entry was still activated in the very same cells (Fig. 1B,E). Furthermore, once capacitative Ca 2+ entry was initiated, Sr2+ (similar results were obtained with Ba2+) rapidly terminated capacitative Ca 2+ entry (Fig. 1C,F).

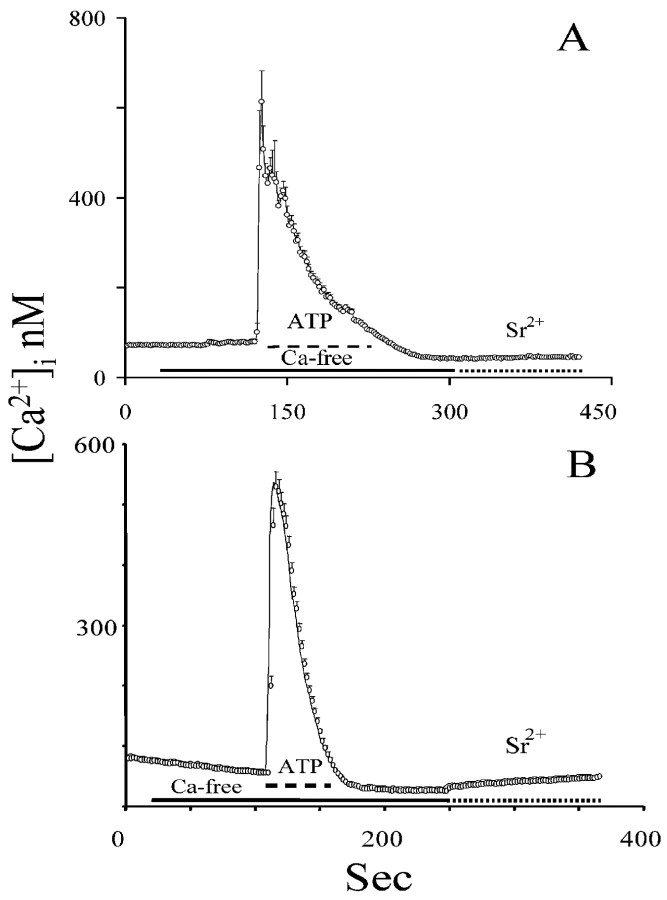

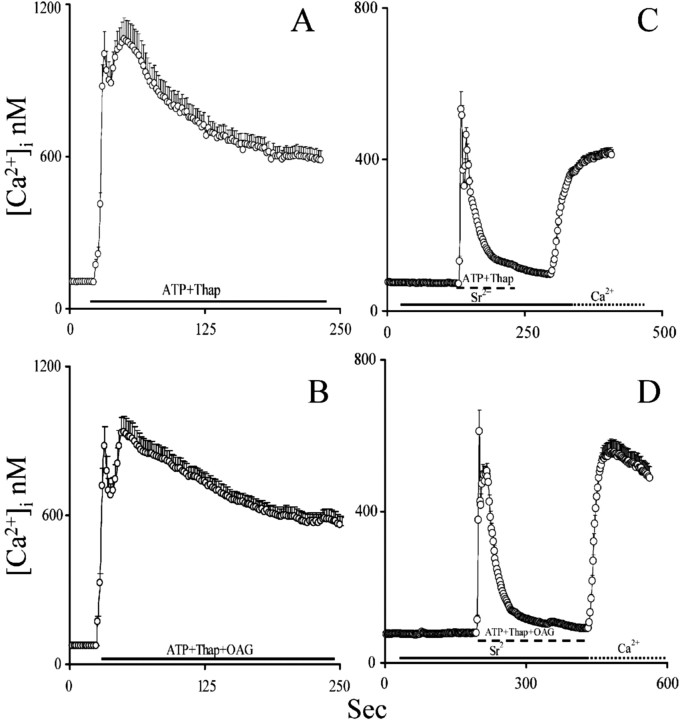

We also depleted intracellular Ca 2+ stores with ATP, a purinergic P2y receptor agonist that induces the production of the second messengers InsP3 and DAG (Shao and McCarthy, 1993). We exposed astrocytes and C6 cells to ATP [10 μm for astrocytes (Grimaldi et al., 1999) and 100 μm for C6 cells] because these two cell types have different sensitivity to ATP (Sabala et al., 2001) in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+. Cells were continuously perfused with ATP until [Ca 2+]i reequilibrated to baseline levels, at which time ATP was washed out. We demonstrated previously that such a treatment causes the complete depletion of intracellular Ca 2+ stores (Grimaldi et al., 2001). As during thapsigargin treatment, Sr2+ (Fig. 2) and Ba2+ (data not shown) did not enter both astrocytes and C6 cells, again suggesting that capacitative Ca 2+ entry is not achieved via the opening of a channel with TRP-like ion conductance selectivity.

Figure 2.

Depletion of intracellular Ca 2+ stores induced by InsP3-elevating agents is not associated with the opening of TRPC. A, B, Astrocytes and C6 cells, respectively, were challenged with ATP in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+ until intracellular Ca 2+ stores were emptied, as testified by the return to baseline of [Ca 2+]i. Next, 1 mm Sr 2+ was supplied in the extracellular solution. Sr 2+ did not enter the cells, indicating that intracellular Ca 2+ stores depletion induced by the ATP was not associated with TRPC opening (note that, to ease readability, values are reported as calibrated Ca 2+ values even when Sr 2+ is present).

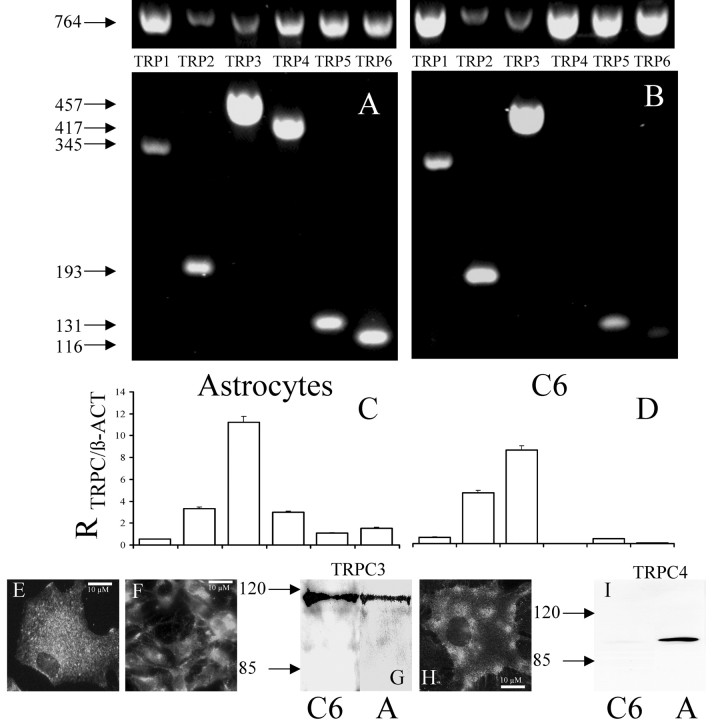

Astrocytes and C6 glioma cells differentially express TRPCs

Using RT-PCR, we showed that astrocytes express mRNA for all six TRPC subtypes (Fig. 3A) (Pizzo et al., 2001). C6 cells do not express TRPC4 and express very little if any TRPC6 (Fig. 3, B vs A). Lack of TRPC4 in C6 cells was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 3C–E) and immunocytochemistry. TRPC3 is the most abundant isoform to be expressed in the two cell types, as shown by densitometric analysis of the TRPCs versus β-actin amplification products in the same RT-PCR reactions (Fig. 3A,B, bar graphs) and by Western blot (Fig. 3G).

Figure 3.

Expression of TRPC in astrocytes and C6 glioma cells. A, mRNA extracted from astrocytes was amplified with primers designed to amplify TRPC1–TRPC6 andβ-actin (as an internal control to normalize amplification conditions and mRNA loading). The arrows flanking the gels highlight amplification product size (TRPC1, 345 bp; TRPC2, 193 bp; TRPC3, 457 bp; TRPC4, 417 bp; TRPC5, 131 bp; TRPC6, 116 bp). B, mRNA extracted from C6 was amplified with primers designed to amplify TRPC1–TRPC6 and β-actin. C, Ratio of TRPC1–TRPC6 versusβ-actin in type I astrocytes was calculated, and results were plotted in bar graphs. TRPC3 resulted to be the most abundant isoforms; TRPC4 and TRPC2 were also abundant. D, Ratio of TRPC1–TRPC6 versusβ-actin in C6 cells. TRPC3 was the most abundant isoform. TRPC4 yielded no amplification product, and TRPC6 was almost undetectable. E, Localization of TRPC3 in rat astrocytes obtained via indirect immunofluorescence detection. Scale bar, 10 μm. F, Localization of TRPC3 in C6 cells obtained via immunofluorescence detection. Scale bar, 10 μm distance. G, Western blot of TRPC3 in astrocytes and C6 cells. Proteins extracted from astrocytes and C6 cells were immunoblotted with anti TRPC3 antibody, and an immunoreactive band was detected at the expected molecular weight of ∼115 kDa in both cell types. H, Localization of TRPC4 in rat astrocytes obtained via immunofluorescence detection. Scale bar, 10 μm. I, Western blot with anti-TRPC4 antibody in type I astrocytes and C6 cells. An immunoreactive band was detected at the expected molecular weight of ∼97 kDa in astrocytes but not in C6 cells.

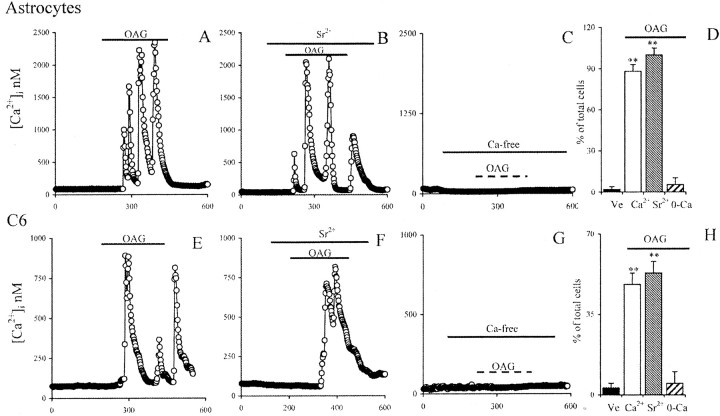

OAG activation of TRPCs induces high-amplitude, low-frequency [Ca 2+]i oscillations

Several studies have reported that OAG causes the opening of TRPC3 and TRPC6 and in some instances of TRPC1, independent of lipid-sensitive protein kinase C activation (Hofmann et al., 1999). OAG gates a nonselective cationic channel permeable to Ca 2+, Sr2+, and Ba2+ (Estacion et al., 1999). To determine whether OAG-activated TRPCs play a role in Ca 2+ homeostasis in glial cells, we exposed astrocytes and C6 cells to OAG (100 μm) and monitored [Ca 2+]i. After a short latency, OAG induced large, low-frequency [Ca 2+]i oscillations in both astrocytes (Fig. 4A) and C6 cells (Fig. 4E). Individual [Ca 2+]i oscillations reached very high [Ca 2+]i values and decreased almost to baseline over a period of several seconds. [Ca 2+]i oscillations were observed throughout a 10 min period of exposure to OAG (data not shown). During wash out, cells ceased oscillatory activity, demonstrating that the action of OAG was readily reversible. Approximately 90% of the astrocytes (n = 798) (Fig. 4D) and 45% of the C6 cells studied (n = 954) (Fig. 4H) responded to OAG with two or more large [Ca 2+]i oscillations. This result was completely unexpected because previous reports have not found an oscillatory component in OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i elevations (Shuttleworth, 1996; Estacion et al., 1999; Hofmann et al., 1999; Lintschinger et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2000; Vazquez et al., 2001; Montell et al., 2002; Trebak et al., 2002).

Figure 4.

Effect of activation of OAG-sensitive TRPC in astrocytes and C6 glioma cells. A, Exposure to 100 μm OAG evoked low-frequency, high-amplitude [Ca 2+]i oscillations after a brief delay. B, [Ca 2+]i oscillations were not affected when extracellular Ca 2+ was exchanged with Sr 2+, suggesting that they were attributable to activation of TRPC. C, Exposure of astrocytes to 100 μm OAG in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+ failed to cause oscillations. D, Percentage of astrocytes responding to OAG with [Ca 2+]i oscillations. Vehicle astrocytes (black bar), OAG-treated cells in the presence of 1 mm extracellular Ca 2+(white bar), 1 mmSr2+(gray bar), or 0 extracellular Ca 2+(hatched bar) in the extracellular solution.E, Exposure of C6 cells to 100 μm OAG evoked low-frequency, high-amplitude[Ca 2+]ioscillations.F, Also in C6 cells,[Ca 2+]ioscillations were not inhibited when extracellular Ca 2+was exchanged with Sr2+, suggesting that they were attributable to activation of TRPC. G, Exposure of C6 glioma cells to 100 μm OAG in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+ failed to cause oscillations. H, Percentage of C6 cells responding to OAG with [Ca 2+]i oscillations. Vehicle-treated cells (black bar), OAG-treated cells in the presence of 1 mm extracellular Ca 2+ (white bar), 1 mm Sr2+ (gray bar), or 0 extracellular Ca 2+ (hatched bar) in the extracellular solution. ** indicated a statistically significant difference versus control cells as assessed by Wilcoxon ranked test (note that, to ease readability, values are reported as calibrated Ca 2+ values even when Sr2+ is present).

OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations were maintained in extracellular solution containing 1 mm Sr2+ and no Ca 2+, indicating that they were, attributable to the opening of a nonselective cation channel, likely a TRPC (Fig. 4B,F). [Ca 2+]i oscillations are believed to be attributable to either cyclical release of InsP3 and/or Ca 2+-mediated desensitization and subsequent resensitization of the InsP3 receptor (Hajnoczky and Thomas, 1997). Hence, these are generally believed to be triggered by InsP3-mediated Ca 2+ release from intracellular Ca 2+ stores in an oscillatory manner (Hajnoczky and Thomas, 1997). Therefore, we studied the effect of altering [Ca 2+]i on OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations. In the absence of extracellular Ca 2+, OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations were completely inhibited, indicating that, in both astrocytes and C6 cells, they were initiated by the entrance of extracellular Ca 2+ (Fig. 4C,G; for statistical validation, see D,H).

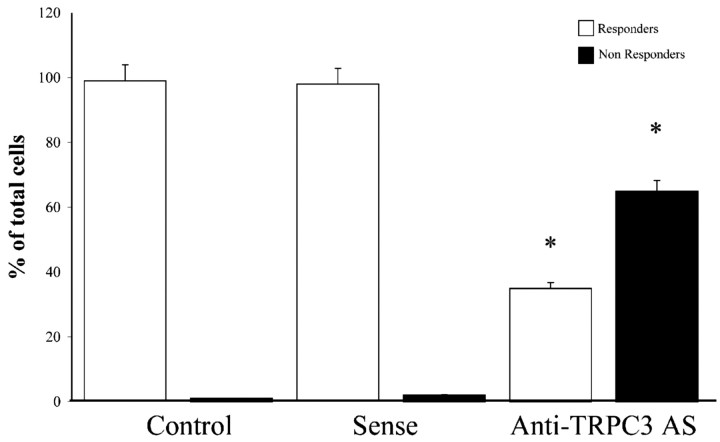

Treatment of astrocytes with an antisense (100 μg/ml) designed to inhibit the expression of TRPC3 greatly reduced the percentage of astrocytes responding to OAG (Fig. 5). Approximately 99% of the astrocytes treated with vehicle (n = 154; r = 3) or sense sequence (n = 130; r = 3) responded to OAG exposure with [Ca 2+]i oscillations as untreated cells. Only ∼35% of the antisense-treated astrocytes (n = 212; r = 4) responded to OAG (a 75% inhibition) versus both vehicle or sensetreated cells.

Figure 5.

Effect of anti-TRPC3 antisense oligonucleotides on OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations. Astrocytes were treated for 36 hr with vehicle, and 100 μg/ml TRPC3 sense or antisense oligonucleotides were loaded with fura-2 and then exposed to 100 μm OAG. Open bars indicate responding cells, and filled bars indicate nonresponding cells. Anti-TRPC3 oligunucleotide treatment significantly reduced the number of astrocytes (AS) responding to OAG. Statistical analysis was performed with Wilcoxon ranked test. * indicates a significant difference versus vehicle.

Regulation of OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations

We studied OAG-triggered [Ca 2+]i oscillations under conditions affecting InsP3 production.

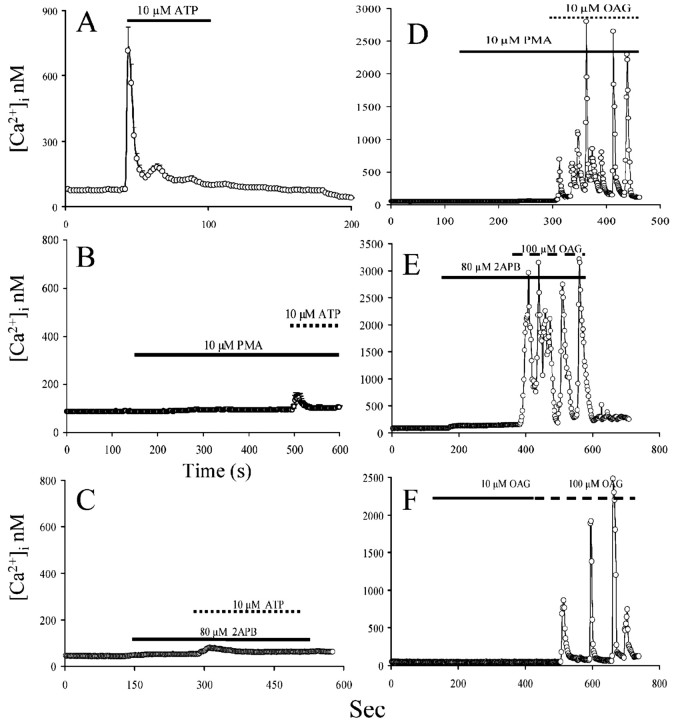

Pretreatment with phorbol esters has been shown to inhibit both phospholipase C (PLC) activity (Chuprun and Rapoport, 1997) and InsP3-sustained [Ca 2+]i oscillations (Chuprun and Rapoport, 1997). Moreover, phorbol esters have been shown to decrease Ca 2+ storage in the intracellular Ca 2+ stores without activating capacitative Ca 2+ entry, thus reducing Ca 2+ available to sustain the InsP3-induced Ca 2+ response (Ribeiro and Putney, 1996). We treated astrocytes with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and then stimulated the cells with the purinergic agonist ATP (10 μm). PMA pretreatment strongly reduced the ATP-triggered elevation of [Ca 2+]i (Fig. 6, compare A, B). However, PMA pretreatment did not affect OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations (Fig. 6D). 2-Amino phenyl borane (2-APB), a cell-permeable antagonist of InsP3 (Maruyama et al., 1997), also strongly reduced the ATP response (Fig. 6C) without affecting OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations (Fig. 6E). Finally, preexposure to a lower concentration of OAG before challenging the cells with a fully effective concentration of OAG did not abolish or reduce OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations (Fig. 6F).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of InsP3-mediated Ca 2+ mobilization does not affect OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations in type I astrocytes. A, Astrocytes exposed to 10 μm ATP respond with a typicalCa 2+transient response characterized by a fast, large initialrise, followed by a sustained [Ca 2+]i elevation phase to a lower [Ca 2+]i. B, Astrocytes treated with 10 μm PMA (solid horizontal bar) showed a severely inhibited response to ATP. C, 2-APB at 80 μm, a blocker of the InsP3 receptor, almost completely blocked the effect of ATP on [Ca 2+]i. D, Preexposure of astrocytes to PMA did not affect the appearance or the amplitude of OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations. E, Pretreatment with 80 μm 2-APB failed to affect OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations. F, Pretreatment of astrocytes with 10 μm OAG did not trigger [Ca 2+]i oscillations but also did not affect the ability of 100 μm OAG to trigger [Ca 2+]i oscillations.

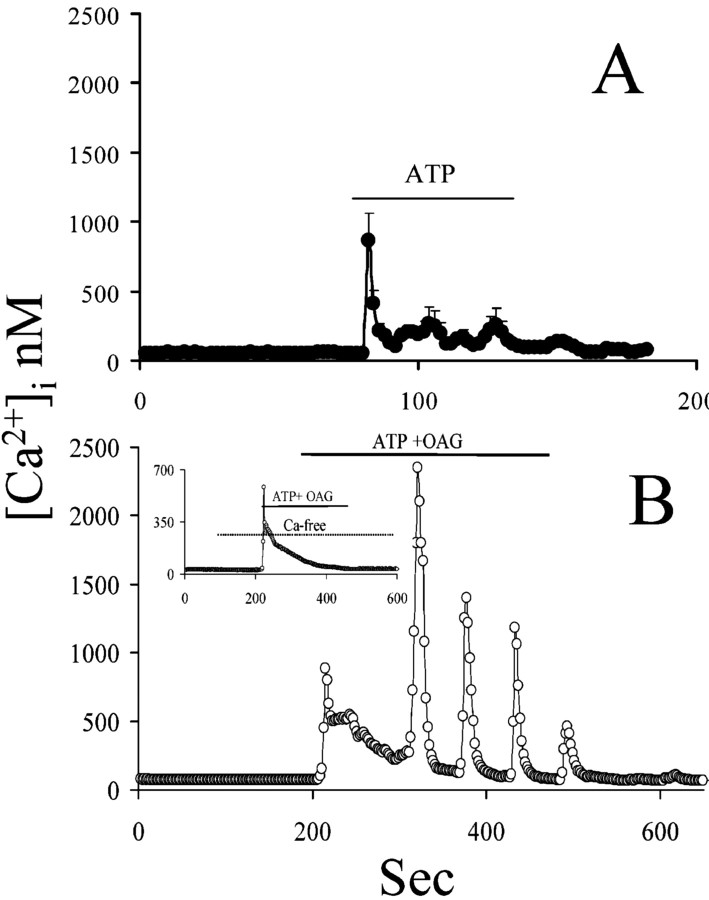

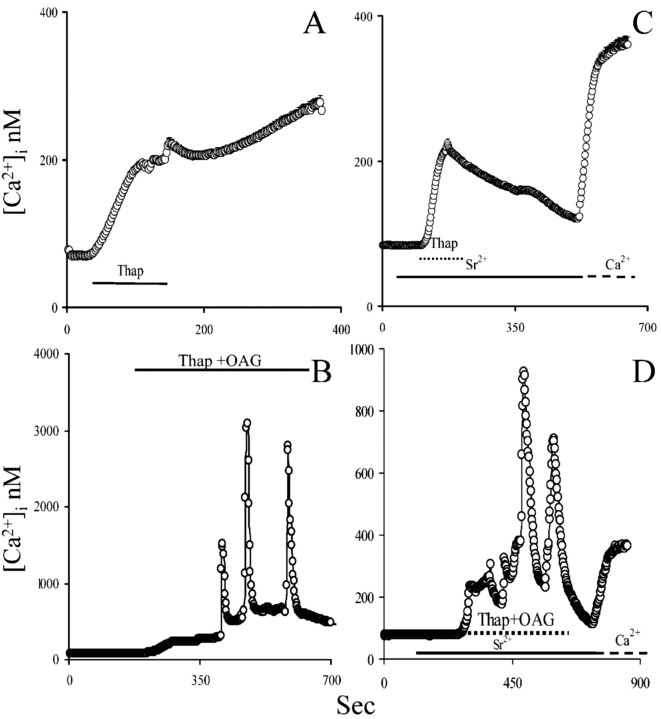

We next asked whether [Ca 2+]i could regulate the activity of the OAG-sensitive TRPC. We used different experimental approaches to elevate [Ca 2+]i to different levels and assessed the function of OAG-activated TRPC. ATP exposure was not able to trigger [Ca 2+]i oscillations (Fig. 7A), nor did it affect OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations (Fig. 7B). However, OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations in the presence of ATP were completely prevented by extracellular Ca 2+ withdrawal, whereas ATP response was completely preserved (Fig. 7B, inset). The [Ca 2+]i transient evoked by ATP is characterized by a rapid peak, followed by a prolonged plateau phase at a lower [Ca 2+]i. The latter could not be high enough to affect TRPCs. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of a more prolonged and marked [Ca 2+]i elevation. Thapsigargin causes a prolonged elevation of [Ca 2+]i and avoids reuptake in the intracellular Ca 2+ stores (Fig. 8A). In the presence of thapsigargin and extracellular Ca 2+, OAG-triggered [Ca 2+]i oscillations were still observed. The increasingly higher [Ca 2+]i reached after each oscillation was attributable to the inability of the thapsigargin-treated cells to take up Ca 2+ in the intracellular Ca 2+ stores (Fig. 8B). OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations in the presence of thapsigargin were preserved in the presence of extracellular Sr2+, indicating that TRPC can still be activated in this condition (Fig. 8D). Additionally, this set of experiments indicates that TRPC opening is not potentiated by intracellular Ca 2+ stores depletion, contrary to what one would expect, if TRPC was being operated by intracellular Ca 2+ stores depletion (Fig. 8B).

Figure 7.

Preexposure to an agonist mobilizing Ca 2+ from intracellular Ca 2+ stores does not affect OAG-triggered [Ca 2+]i oscillations. A, Exposure of astrocytes to ATP causes a typical [Ca 2+]i transient response characterized by a peak followed by much lower plateau phase. B, Astrocytes were exposed simultaneously to ATP and OAG. The ability of OAG to initiate [Ca 2+]i oscillations during the plateau phase of the ATP response was completely unaffected. The inset in B shows that, although the peak phase of the response to ATP is preserved in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+, both the plateau phase of the ATP response and OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations are prevented by removal of extracellular Ca 2+.

Figure 8.

Exposure to thapsigargin does not affect OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations in astrocytes. A, Treatment with 2 μm thapsigargin (Thap) elevates [Ca 2+]i. B, Astrocytes were exposed simultaneously to thapsigargin and 100 μm OAG. Depletion of intracellular Ca 2+ stores and mild [Ca 2+]i elevation of did not affect OAG-evoked [Ca 2+]i oscillations. C, When extracellular Ca 2+ is exchanged with 1 mm Sr 2+, 2 μm thapsigargin elevated [Ca 2+]i, but the prolonged plateau phase was lost. D, Effect of 2 μm thapsigargin and 100 μm OAG in the presence of 1 mm extracellular Sr 2+. OAG is still able to induce[Ca 2+]ioscillations(note that, to ease readability, values are reported as calibrated Ca 2+ values even when Sr 2+ is present).

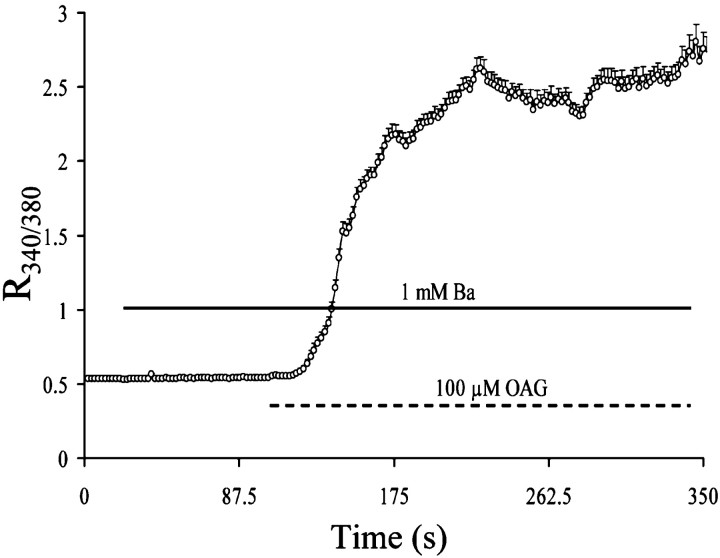

Whereas ATP and thapsigargin individually do not affect OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations, the simultaneous exposure to ATP and thapsigargin caused a high, long-lasting [Ca 2+]i elevation (Fig. 9A) and completely prevented OAG-induced oscillations. This suggests that a large [Ca 2+]i elevation may block OAG-sensitive TRPC function (Fig. 9A vs B). To assess whether, in the presence of ATP, thapsigargin, and OAG, the OAG-sensitive TRPCs are open and only the oscillatory activity is lost, we exposed the cells to ATP–thapsigarin–OAG in the presence of extracellular Sr2+. Stimulation of astrocytes with ATP and thapsigargin did not result in any Sr2+ entry (Fig. 9C). When astrocytes were exposed to ATP–thapsigargin–OAG, again no Sr2+ influx was recorded, suggesting that, after a large [Ca 2+]i elevation, as achieved with the simultaneous exposure to ATP and thapsigargin, the OAG-sensitive TRPC is closed (Fig. 9C vs D). We performed an additional experiment using Ba2+, which is also conducted by OAG-sensitive TRPCs, but is not pumped into the endoplasmic reticulum by SERCA (Vanderkooi and Martonosi, 1971; Kwan and Putney, 1990). Ba2+ is also not able to interact with most of the Ca 2+-binding proteins (Eckert and Tillotson, 1981; Hagiwara and Ohmori, 1982). However, Ba2+ still binds to fura-2 and causes an increase of 340:380 ratio, similar to Ca 2+ (Kwan and Putney, 1990). In the presence of extracellular Ba2+, OAG caused a progressive elevation of fura-2 ratio, indicating that, in the absence of [Ca 2+]i elevation, TRPCs are constantly opened by OAG (Fig. 10).

Figure 9.

Effect of high [Ca 2+]i on OAG-induced oscillations: A, We induced a large and persistent elevation of [Ca 2+]i by challenging astrocytes with both 10 μm ATP and 2 μm thapsigargin (Thap). B, Under this condition, OAG failed to cause [Ca 2+]i oscillations. C, In the presence of ATP and thapsigargin, there was no influx of Sr 2+, suggesting TRPC channel closure. D, Astrocytes were exposed to ATP, thapsigargin, and OAG simultaneously in the presence of 1 mm extracellular Sr 2+. In this condition, no Sr 2+ entry was detected. Extracellular Ca 2+ solution at 1 mm was then added and a large[Ca 2+]ielevation was detected, indicating a strong capacitative Ca 2+ entry activation (note that, to ease readability, values are reported as calibrated Ca 2+ values even when Sr 2+ is present).

Figure 10.

Effect of OAG in the presence of the large divalent cation Ba 2+. Astrocytes were perfused with 1 mm Ba 2+ and 0 Ca 2+. Cells were then exposed to 100 μm OAG, which caused a gradual and large elevation of fura-2 ratio signal (R340/380).

[Ca 2+]i oscillations are not mimicked by endogenous DAG elevation

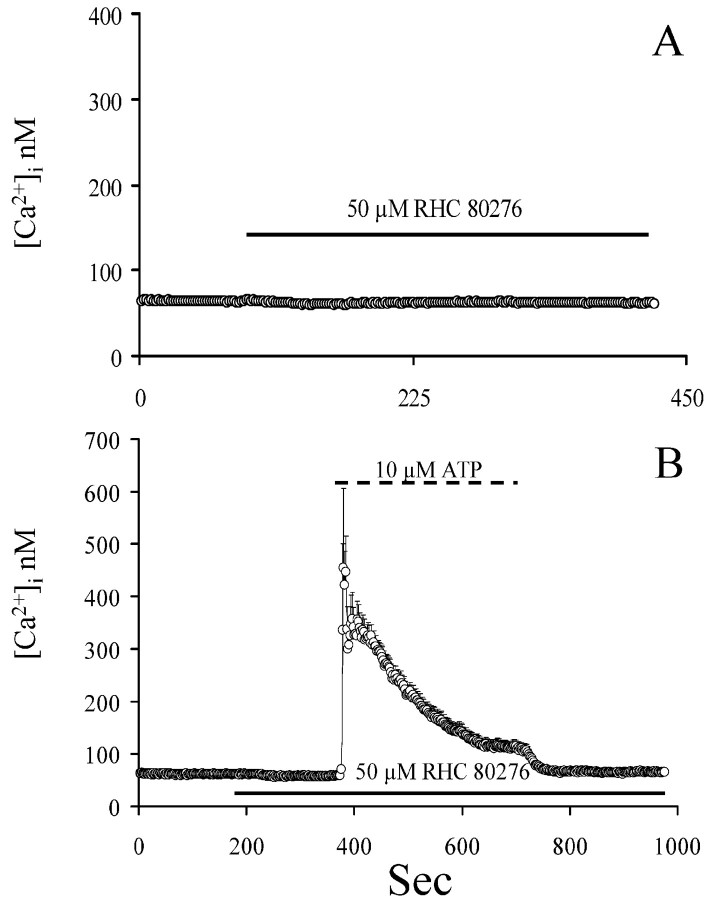

We conducted experiments designed to test whether endogenous DAG can trigger [Ca 2+]i oscillations similar to exogenously applied OAG. In other cells in which TRPCs were overexpressed, inhibition of DAG-lipase by RHC80276 activates TRPC channels, presumably via the accumulation of basally released and uncatabolized DAG (Hofmann et al., 1999; Ma et al., 2000). In astrocytes, RHC80276 alone did not evoke an elevation of [Ca 2+]i (Fig. 11A). Because it was conceivable that basal release of DAG in astrocytes may be very low, we analyzed the effect of RHC80276 in conjunction with a PLC-stimulating agonist, with the aim of causing a greater elevation of DAG concentration and unveiling DAG-activated [Ca 2+]i oscillations. Exposure to ATP, which did not affect OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations (Fig. 7A), in the presence of RHC80276, did not trigger [Ca 2+]i oscillations (Fig. 11B) or Sr2+ entry (data not shown). This finding indicates that endogenous DAG may not gain access to the OAG binding site on the TRPC naturally expressed in type I astrocytes.

Figure 11.

Effect of DAG-lipase blockade on [Ca 2+]i in un stimulated and ATP-stimulated astrocytes. A, Astrocytes were perfused with the compound RHC80276. The agent did not cause any change of[Ca 2+]i.B, RHC80276 did not affect[Ca 2+]ielevation induced by 10 μmATP, nor were oscillations observed.

Discussion

Capacitative Ca 2+ entry is a well known phenomenon occurring in a wide variety of cell types. Capacitative Ca 2+ entry provides Ca 2+ for intracellular Ca 2+ stores refilling and to sustain prolonged [Ca 2+]i elevations in response to InsP3-linked agonists. We and others have shown in astrocytes that Ca 2+ entry is activated in response to intracellular Ca 2+ stores depletion and that capacitative Ca 2+ entry participates in regulating the magnitude of responses to Ca 2+-mobilizing agonists (Grimaldi et al., 1999, 2001; Jung et al., 2000). The duration and the magnitude of [Ca 2+]i transients are important determinants of the intracellular cascades activated by extracellular signals. Therefore, characterization of capacitative Ca 2+ entry regulation is necessary to tease apart multiple signaling pathways. The channels responsible for capacitative Ca 2+ entry have not yet been identified, but evidence supports an overlap of functions between storeoperated Ca 2+ channels activity and the TRPC family of ion channels (Zhu et al., 1996; Vazquez et al., 2001; Montell et al., 2002). However, several differences have been reported between store-operated Ca 2+ channels and TRPC function (Montell et al., 2002). Moreover, most studies that implicate TRPC isoforms in store-operated Ca 2+ channels function do so in heterologous systems in which the TRPC isoforms are overexpressed (Hofmann et al., 1999; Ma et al., 2000; Vazquez et al., 2001; Trebak et al., 2002). We studied capacitative Ca 2+ entry in the native environment of type I astrocytes and C6 glioma cells with the aim of characterizing store-operated Ca 2+ channels activity and TRPCs function, their involvement in capacitative Ca 2+ entry, and their contribution to intracellular Ca 2+ homeostasis. We were able to demonstrate that store-operated Ca 2+ channels and TRPC activity are functionally distinct entities. In fact, capacitative Ca 2+ entry triggered by intracellular Ca 2+ stores depletion via both agonist or SERCA inhibitor exposure resulted in extracellular Ca 2+ influx (capacitative Ca 2+ entry) via a channel activity that is extremely selective in its ion permeability, like typical storeoperated Ca 2+ channels. During capacitative Ca 2+ entry, Ca 2+ is allowed entry into astrocytes and C6 cells, but the larger cations Sr2+ and Ba2+ are not (Hoth and Penner, 1992; Parekh and Penner, 1997). This suggests that the Sr2+/Ba2+-permeable TRPCs are unlikely to be involved in capacitative Ca 2+ entry in astrocytes. Instead, Sr2+ and Ba2+ act as antagonists of capacitative Ca 2+ influx. These findings clearly demonstrate that TRPCs are not involved in capacitative Ca 2+ entry in glial cells.

Several isoforms of TRPC are expressed in type I astrocytes (Pizzo et al., 2001). Because intracellular Ca 2+ stores depletion and capacitative Ca 2+ entry activation did not open TRPC in either astrocytes or C6 cells, we wondered what role the abundant expression of these channels served in the Ca 2+ homeostasis of glial cells. To study the effect of TRPC opening in glial cells, we used the DAG analog OAG, which specifically activates certain subtypes of TRPC implicated in capacitative Ca 2+ entry in other systems (Ma et al., 2000; Vazquez et al., 2001), in a protein kinase C-unrelated manner (Hofmann et al., 1999). Surprisingly, OAG evoked low-frequency, high-amplitude [Ca 2+]i oscillations. These [Ca 2+]i oscillations were preserved when extracellular Ca 2+ was replaced by Sr2+, implicating the involvement of a nonselective Ca 2+ channel, such as TRPC3. TRPC1 and TRPC6 are not operated by OAG and are not permeable to Sr2+ (Hofmann et al., 1999; Lintschinger et al., 2000). TRPC6 is also not expressed in C6 cells. TRPC4, which is expressed in type I astrocytes, but not in C6, has been implicated in muscarinic receptoractivated [Ca 2+]i oscillations (Wu et al., 2002). However, TRPC4-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations required agonist exposure to be triggered, a substantial difference from OAG-induced oscillations, which do not require agonist exposure. Additionally, our finding that TRPC4s are not expressed in C6, although C6 cells responded to OAG exposure with [Ca 2+]i oscillations, further strengthen the view that TRPC4 plays no part in [Ca 2+]i oscillations triggered by OAG. Pharmacological and molecular evidence seemed to strongly implicate activation of TRPC3 in the OAG-triggered [Ca 2+]i oscillations observed in astrocytes and C6 cells. To directly implicate TRPC3 in [Ca 2+]i oscillations evoked by OAG exposure, we conducted an additional set of experiments molecularly ablating the channel with antisense oligonucleotides. We designed a specific antisense oligonucleotide directed toward TRPC3 in an isoform-specific region on the basis of the PCR template. When primers with the same sequence are used in PCR, they amplify a single band corresponding to the number of base pairs anticipated on the basis of TRPC3 sequence (Fig. 3). Treatment of astrocytes with this antisense inhibited the number of cells responding to OAG by 75%, strongly implicating this isoform of TRPC in the phenomenon we described in this study.

[Ca 2+]i oscillations have been observed in some cell types, including astrocytes (Berridge, 1990; Charles et al., 1991; Fatatis and Russell, 1992; Pasti et al., 1995, 1997, 2001; Yagodin et al., 1995; Parri et al., 2001). Oscillations are known to trigger several biological responses, including secretion and gene expression (Berridge, 1990; Dolmetsch et al., 1998). Uncontrolled [Ca 2+]i oscillations have also been implicated in specific neuropathological conditions, such as specific forms of epilepsy (Manning and Sontheimer, 1997; Tashiro et al., 2002). Classically, [Ca 2+]i oscillations in astrocytes are viewed as a phenomenon dependent on InsP3 signaling and intracellular Ca 2+ release (Hajnoczky and Thomas, 1997). The OAG-triggered [Ca 2+]i oscillations, which we report here for the first time and which we ascribe to TRPC3 activation, could also potentially involve InsP3 and mobilization of intracellular Ca 2+ (Hajnoczky and Thomas, 1997). However, blockade of InsP3 signaling with 2-APB or by downregulation of PLC by pretreatment with phorbol esters (Ribeiro and Putney, 1996; Chuprun and Rapoport, 1997; Maruyama et al., 1997) did not influence OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations. Instead, OAG-induced [Ca 2+]i oscillations were completely blocked by removal of extracellular Ca 2+. In addition, when intracellular Ca 2+ stores were depleted by thapsigargin or by ATP exposure, OAG still evoked oscillations. This latter evidence seems to exclude release from intracellular Ca 2+ stores as a player in the effect of OAG. Together, our data support the view that the initiation of OAG-triggered [Ca 2+]i oscillations does not require participation of intracellular signaling and relies primarily on the entry of extracellular Ca 2+. The oscillatory response may be explained by a U-shaped [Ca 2+]i dependency. In this model, a channel that opens at basal [Ca 2+]i will close when [Ca 2+]i reaches a certain high level so that clearing mechanisms can decrease [Ca 2+]i. The oscillation will reinitiate when Ca 2+ falls below a certain critical lower threshold. To explore whether Ca 2+ regulated TRPC activity in such a way, in astrocytes, we analyzed the behavior of the TRPC3 at different [Ca 2+]i. During the plateau phase of agonist stimulation and during thapsigargin treatment, both of which cause mild [Ca 2+]i elevations, oscillations triggered by OAG were not inhibited. This indicated that modest [Ca 2+]i elevation or intracellular Ca 2+ stores depletion did not block OAG-sensitive TRPC. In addition, these treatments also did not potentiate capacitative Ca 2+ entry, as expected if TRPCs were opened in a store depletion-dependent manner. However, when [Ca 2+]i was elevated to a greater extent, by simultaneous challenge with ATP and thapsigargin, exposure to OAG was no longer able to cause [Ca 2+]i oscillations. The inability of OAG to trigger [Ca 2+]i oscillations under conditions of high [Ca 2+]i was not because of a change in the kinetics of the channel activity but because of the closure of the channel. In fact, under these conditions, neither Sr2+ nor Ba2+ entered the cells, clearly indicating the complete closure of the channel rather than a maintained open state of the channel. This view is strengthened by the finding that, when cells were exposed to OAG in the presence of Ba2+ and in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+, TRPC remained open during the entire time of exposure to OAG, as shown by the gradual but constant increase in cytosolic Ba 2+. The latter finding is explained by the fact that Ba 2+ does not bind to most of the Ca 2+ sensors (Eckert and Tillotson, 1981; Hagiwara and Ohmori, 1982), causing the inhibition of the channel by high [Ca 2+]i to fail.

It is commonly believed that the second messenger operating the TRPC3 channels is DAG (Hofmann et al., 1999). The data we present here suggest that cytosolic DAG elevation is not able to trigger TRPC opening. Previous studies have demonstrated that, in cells overexpressing TRPC6 (Hofmann et al., 1999) and TRPC3 (Ma et al., 2000), DAG elevation by means of the DAG lipase inhibitor RHC80276 caused an influx of extracellular cations, such as Mg2+ and Ba2+ (Hofmann et al., 1999; Ma et al., 2000). In astrocytes and in C6 cells, we did not show such an effect of RHC80276 either in basal conditions or after the stimulation of the production of DAG by PLC activation by ATP. Therefore, we hypothesize that, in natively expressed TRPC3 in astrocytes, the OAG-sensitive site may be inaccessible to endogenously released DAG. This suggests the possibility that an extracellular substance, chemically related to OAG, may be the actual ligand responsible for the operation of OAG-sensitive TRPCs in physiological conditions.

In conclusion, we determined that store-operated Ca 2+ channels activity is not mediated by TRPC opening in glial cells. We also identified a potentially novel mode of Ca 2+ signaling in glial cells attributable to the activation of TRPC3. This novel mode of Ca 2+ signaling takes the form of high-amplitude [Ca 2+]i oscillations repeating at low frequency that is independent of InsP3 and mobilization of intracellularly stored Ca 2+, hence differing from previously described oscillatory phenomenon. These [Ca 2+]i oscillations are blocked by high [Ca 2+]i and may be induced by an extracellular congener of DAG, released by nearby neurons or astrocytes. We propose that such a signaling pathway may play a relevant role in glial physiology.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Department of Defense Grants MDA905-02-2-0001 and MDA905-001-034 and National Institutes of Health Grant 5 RO1 NS37814 (A.V.). We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Laurel Haak for her critical discussion of the data and for her help in editing this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Maurizio Grimaldi, Department of Neurology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Room B3007, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD 20814. E-mail: mgrimaldi@usuhs.mil.

Copyright © 2003 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/03/234737-09$15.00/0

References

- Berridge MJ ( 1990) Calcium oscillations. J Biol Chem 265: 9583–9586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM ( 1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles AC, Merrill JE, Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ ( 1991) Intercellular signaling in glial cells: calcium waves and oscillations in response to mechanical stimulation and glutamate. Neuron 6: 983–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuprun JK, Rapoport RM ( 1997) Protein kinase C regulation of ATPinduced phosphoinositide hydrolysis in bovine aorta endothelial cells. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 17: 787–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Xu K, Lewis RS ( 1998) Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature 392: 933–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert R, Tillotson DL ( 1981) Calcium-mediated inactivation of the calcium conductance in caesium-loaded giant neurones of Aplysia californica. J Physiol (Lond) 314: 265–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estacion M, Sinkins WG, Schilling WP ( 1999) Stimulation of Drosophila TrpL by capacitative Ca 2+ entry. Biochem J 341: 41–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatatis A, Russell JT ( 1992) Spontaneous changes in intracellular calcium concentration in type I astrocytes from rat cerebral cortex in primary culture. Glia 5: 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi M, Pozzoli G, Navarra P, Preziosi P, Schettini G ( 1994) Vasoactive intestinal peptide and forskolin stimulate interleukin 6 production by rat cortical astrocytes in culture via a cyclic AMP-dependent, prostaglandinindependent mechanism. J Neurochem 63: 344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi M, Favit A, Alkon DL ( 1999) cAMP-induced cytoskeleton rearrangement increases calcium transients through the enhancement of capacitative calcium entry. J Biol Chem 274: 33557–33564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi M, Atzori M, Ray P, Alkon DL ( 2001) Mobilization of calcium from intracellular stores, potentiation of neurotransmitter-induced calcium transients, and capacitative calcium entry by 4-aminopyridine. J Neurosci 21: 3135–3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY ( 1985) A new generation of Ca 2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara S, Ohmori H ( 1982) Studies of calcium channels in rat clonal pituitary cells with patch electrode voltage clamp. J Physiol (Lond) 331: 231–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnoczky G, Thomas AP ( 1997) Minimal requirements for calcium oscillations driven by the IP3 receptor. EMBO J 16: 3533–3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G ( 1999) Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature 397: 259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoth M, Penner R ( 1992) Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature 355: 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S, Pfeiffer F, Deitmer JW ( 2000) Histamine-induced calcium entry in rat cerebellar astrocytes: evidence for capacitative and non-capacitative mechanisms. J Physiol (Lond) 527: 549–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan CY, Putney Jr JW ( 1990) Uptake and intracellular sequestration of divalent cations in resting and methacholine-stimulated mouse lacrimal acinar cells. Dissociation by Sr 2+ and Ba 2+ of agonist-stimulated divalent cation entry from the refilling of the agonist-sensitive intracellular pool. J Biol Chem 265: 678–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lintschinger B, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, Baskaran T, Graier WF, Romanin C, Zhu MX, Groschner K ( 2000) Coassembly of Trp1 and Trp3 proteins generates diacylglyceroland Ca 2+-sensitive cation channels. J Biol Chem 275: 27799–27805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma HT, Patterson RL, van Rossum DB, Birnbaumer L, Mikoshiba K, Gill DL ( 2000) Requirement of the inositol trisphosphate receptor for activation of store-operated Ca 2+ channels. Science 287: 1647–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning Jr TJ, Sontheimer H ( 1997) Spontaneous intracellular calcium oscillations in cortical astrocytes from a patient with intractable childhood epilepsy (Rasmussen's encephalitis). Glia 21: 332–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Kanaji T, Nakade S, Kanno T, Mikoshiba K ( 1997) 2APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, a membrane-penetrable modulator of Ins(1,4,5)P3-induced Ca 2+ release. J Biochem (Tokyo) 122: 498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C, Birnbaumer L, Flockerzi V ( 2002) The TRP channels, a remarkably functional family. Cell 108: 595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB, Penner R ( 1997) Store depletion and calcium influx. Physiol Rev 77: 901–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parri HR, Gould TM, Crunelli V ( 2001) Spontaneous astrocytic Ca 2+ oscillations in situ drive NMDAR-mediated neuronal excitation. Nat Neurosci 4: 803–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasti L, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G ( 1995) Long-lasting changes of calcium oscillations in astrocytes. A new form of glutamate-mediated plasticity. J Biol Chem 270: 15203–15210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasti L, Volterra A, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G ( 1997) Intracellular calcium oscillations in astrocytes: a highly plastic, bidirectional form of communication between neurons and astrocytes in situ. J Neurosci 17: 7817–7830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasti L, Zonta M, Pozzan T, Vicini S, Carmignoto G ( 2001) Cytosolic calcium oscillations in astrocytes may regulate exocytotic release of glutamate. J Neurosci 21: 477–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzo P, Burgo A, Pozzan T, Fasolato C ( 2001) Role of capacitative calcium entry on glutamate-induced calcium influx in type-I rat cortical astrocytes. J Neurochem 79: 98–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney Jr JW ( 1986) A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium 7: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney Jr JW, Broad LM, Braun FJ, Lievremont JP, Bird GS ( 2001) Mechanisms of capacitative calcium entry. J Cell Sci 114: 2223–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro CM, Putney JW ( 1996) Differential effects of protein kinase C activation on calcium storage and capacitative calcium entry in NIH 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem 271: 21522–21528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabala P, Czajkowski R, Przybylek K, Kalita K, Kaczmarek L, Baranska J ( 2001) Two subtypes of G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors, P2Y(1) and P2Y(2) are involved in calcium signalling in glioma C6 cells. Br J Pharmacol 132: 393–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, McCarthy KD ( 1993) Regulation of astroglial responsiveness to neuroligands in primary culture. Neuroscience 55: 991–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth TJ ( 1996) Arachidonic acid activates the noncapacitative entry of Ca 2+ during [Ca 2+]i oscillations. J Biol Chem 271: 21720–21725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Goldberg J, Yuste R ( 2002) Calcium oscillations in neocortical astrocytes under epileptiform conditions. J Neurobiol 50: 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thastrup O, Dawson AP, Scharff O, Foder B, Cullen PJ, Drobak BK, Bjerrum PJ, Christensen SB, Hanley MR ( 1989) Thapsigargin, a novel molecular probe for studying intracellular calcium release and storage. Agents Actions 27: 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebak M, Bird GS, McKay RR, Putney Jr JW ( 2002) Comparison of hTRPC3 channels in receptor-activated and store-operated modes. Differential sensitivity to channel blockers suggests fundamental differences in channel composition. J Biol Chem 277: 21617–21623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderkooi JM, Martonosi A ( 1971) Sarcoplasmic reticulum. XII. The interaction of 8-anilino-1-naphthalene sulfonate with skeletal muscle microsomes. Arch Biochem Biophys 144: 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez G, Lievremont JP, St JBG, Putney Jr JW ( 2001) Human Trp3 forms both inositol trisphosphate receptor-dependent and receptorindependent store-operated cation channels in DT40 avian B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 11777–11782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Babnigg G, Zagranichnaya T, Villereal ML ( 2002) The role of endogenous human Trp4 in regulating carbachol-induced calcium oscillations in HEK-293 cells. J Biol Chem 277: 13597–13608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagodin S, Holtzclaw LA, Russell JT ( 1995) Subcellular calcium oscillators and calcium influx support agonist-induced calcium waves in cultured astrocytes. Mol Cell Biochem 149–150: 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Jiang M, Peyton M, Boulay G, Hurst R, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L ( 1996) trp, a novel mammalian gene family essential for agonistactivated capacitative Ca 2+ entry. Cell 85: 661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]