Abstract

Schwann cells require laminin-2 throughout nerve development, because mutations in the α2 chain in dystrophic mice interfere with sorting of axons before birth and formation of myelin internodes after birth. Mature Schwann cells express several laminin receptors, but their expression and roles in development are poorly understood. Therefore, we correlated the onset of myelination in nerve and synchronized myelinating cultures to the appearance of integrins and dystroglycan in Schwann cells. Only α6β1 integrin is expressed before birth, whereas dystroglycan and α6β4 integrin appear perinatally, just before myelination. Although dystroglycan is immediately polarized to the outer surface of Schwann cells,α6β4 appears polarized only after myelination. We showed previously that Schwann cells lacking β1 integrin do not relate properly to axons before birth. Here we show that the absence of β1 before birth is not compensated by other laminin receptors, whereas coexpression of both dystroglycan and β4 integrin is likely required for β1-null Schwann cells to myelinate after birth. Finally, both β1-null and dystrophic nerves contain bundles of unsorted axons, but they are predominant in different regions: in spinal roots in dystrophic mice and in nerves in β1-null mice. We show that differential compensation by laminin-1, but not laminin receptors may partially explain this. These data suggest that the action of laminin is mediated by β1 integrins during axonal sorting and by dystroglycan, α6β1, and α6β4 integrins during myelination.

Keywords: laminin receptors, Schwann cells, dystrophic mice, integrins, dystroglycan, myelination, adhesion

Introduction

Schwann cells (SCs) myelinate axons in the peripheral nervous system (PNS). SC precursors originate from neural crest at embryonic day (E) 12–E13 in mouse, migrate along neurites, and become embryonic SCs between E15 and E16 (for review, see Jessen and Mirsky, 1999). Later, SCs segregate large axons from axon bundles and establish a one-to-one relationship with them (promyelinating SCs). After birth, SCs wrap axons to form myelin (Webster et al., 1973), whereas non-myelin-forming SCs differentiate after postnatal day (P) 15 (Jessen and Mirsky, 1999). These events involve changes in cell shape and cytoskeletal organization that require adhesion to the basal lamina (BL) (Bunge, 1993) or laminin deposition (Podratz et al., 2001).

In mature PNS, laminin-2 (α2/β1/γ1) and minor amounts of laminin-8 (α4/β1/γ1) are present in the endoneurium, whereas laminin-1 (α1/β1/γ1), -9 (α4/β2/γ1), and -11 (α5/β2/γ1) are in the perineurium (Sanes et al., 1990; Patton et al., 1997). Mutations of the laminin α2 chain cause congenital muscular dystrophy and a dysmyelinating neuropathy (Xu et al., 1994; Shorer et al., 1995; Sunada et al., 1995). In dystrophic mice, the neuropathy consists of impaired axonal sorting, mainly in the proximal PNS (Bradley and Jenkison, 1973; Stirling, 1975), and myelination and paranodal abnormalities mainly in distal nerves (Bradley et al., 1977; Jaros and Bradley, 1979). The alterations in axonal sorting originate prenatally and in paranodes and internodes postnatally. The different timing and location of these abnormalities may result from differential expression of laminin receptors in developing nerves. Alternatively, other laminins, or their receptors, could differentially compensate for loss of laminin function.

In keeping with the first possibility, several laminin receptors are present in mature SCs, mainly integrins α6β1 and α6β4 and dystroglycan (DG). Integrins include α and β transmembrane subunits, which form receptors for different matrix components (for review, see Previtali et al., 2001). DG includes an α subunit and a trans-membrane β subunit (Ervasti and Campbell, 1993). Neural crest cells and SCs synthesize α6β1 (Hsiao et al., 1991; Bronner-Fraser et al., 1992; Einheber et al., 1993). Experiments with blocking antibody suggest a role for β1 in myelination (Fernandez-Valle et al., 1994), whereas selective inactivation of β1 in SCs impairs axonal sorting (Feltri et al., 2002). β4 integrin and DG are expressed at the outer surface of adult SCs (Yamada et al., 1994; Quattrini et al., 1996), and their expression is regulated axonally (Einheber et al., 1993; Feltri et al., 1994; Masaki et al., 2000). α-DG binds to laminin-2 in SC BL (Yamada et al., 1994) and forms a complex with periaxin and dystrophic-related protein (DRP)-2 (Sherman et al., 2001). Genetic alterations of periaxin cause a demyelinating neuropathy (Gillespie et al., 2000; Boerkoel et al., 2001; Guilbot et al., 2001). Hence, a role for α6β4 integrin and DG in myelination has been proposed. The onset of α6β4 and DG expression is not known.

We describe the sequential expression of laminin receptors from embryonic nerves to the mature PNS. Precursors and immature SCs expressed only α6β1. DG expression immediately preceded myelination, whereas α6β4 appeared polarized after myelination. In the absence of β1 integrin, no compensatory expression of α6β4 and DG occurs prenatally, explaining the severe prenatal defect. Dystrophic nerves, but not roots, show upregulation of laminin-1 that may compensate for laminin-2 defects. Thus, the complicated temporal and topographic phenotype of laminin and receptor mutants reflects both differences in receptor expression and differential compensation by laminins.

Materials and Methods

Mice and genotyping

FVB/N and C57BL6 mice were from Charles River (Calco, Italy). Dystrophic dy2J mice (B6.WK-Lama2dy-2J) were from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained by backcrosses to C57BL6. P0Cre mice have been described (Feltri et al., 1999a, 2002) and were maintained by backcrosses to either FVB/N or C57BL6 mice. Mice lacking β1 integrin in SCs were produced by crossing P0Cre mice with β1 heterozygous null mice and β1-floxed homozygous mice as described (Graus-Porta et al., 2001; Feltri et al., 2002). Most progeny in this study resulted from parents that were N2–N5 generations congenic for C57BL6. Mouse genotyping was performed by Southern blot and PCR analysis of tail genomic DNA as described previously (Kuang et al., 1998; Feltri et al., 1999a; Graus-Porta et al., 2001). All experiments involving animals were performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In situ hybridization

cDNAs for mouse dystroglycan, β1, β4, and α6 integrins were reverse transcribed from RNA extracted from mouse sciatic nerves as described (Feltri et al., 1999b) using the following primers: DAG sense: 5′-GCT CTA GAA CCC TTG AGG ACC AGG CCA C-3′; antisense: 5′-CAG AAG CTT AAC AGT GCT TCA GAG CCA TC-3′; α6 sense: 5′-GCT CTA GAA CTA CTT GGA CAT TCT CGT G-3′; antisense: 5′-CAG TTC GAA GGT GTC GTC AGT CTG AAA TC-3′; β1 sense: 5′-GCT CTA GAA TCG TGC ATG TTG TGG AGA C-3′; antisense: 5′-CAG TTC GAA GCT TGA TTC CAA TGG TCC AG-3′; β4 sense: 5′-GCT CTA GAC CTT GGC TAC CTG GTG ACC T-3′; antisense: 5′-CAG TTC GAA AGC CAG TCA GAA AGA CCT TG-3′. cDNAs were amplified by PCR, ligated into pBluescript SKII (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and sequenced. Generation of RNA probes and in situ hybridization was performed as described (Previtali et al., 1999).

Antibodies and immunohistochemistry

The antibodies used are listed in Table 1. Secondary antibodies included the following: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse or rat IgG (1:50) and FITC- or TRITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:100) (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for Western blots were from Sigma (Milan, Italy). A mouse-to-mouse Dako ARK-kit (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) was used to stain mouse tissues with mouse antibodies. Immunohistochemistry was performed as described in Feltri et al. (2002) and for α4 laminin chain as described in Miner et al. (1997). For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed 10 min in paraformaldehyde and 15 min in cold methanol. Slides were examined with confocal (Bio-Rad MRC 1024) or fluorescence microscopy (Olympus AX and BX).

Table 1.

List of antibodies used

|

Antigen |

Antibody |

Species |

Clone/name |

Dilution |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-dystroglycan | mAb | Mouse | VA41 | 1:20 | Upstate Biotechnology |

| β-dystroglycan | pAb | Rabbit | AP83 | 1:100 | K. Campbell |

| Integrin α2 | pAb | Rabbit | 1:200 | Chemicon | |

| Integrin α3 | pAb | Rabbit | 1:200 | Chemicon | |

| Integrin α6 | mAb | Rat | GoH3 | 1:25 | A. Sonnenberg |

| Integrin α7 | pAb | Rabbit | U31 | 1:400 | U. Mayer |

| Integrin β1 | pAb | Rabbit | 1:200 | K. Rubin | |

| Integrin β1 | pAb | Rat | MB1.2 | 1:100 | Chemicon |

| Integrin β4 | pAb | Rabbit | 6945 | 1:300 | V. Quaranta |

| Integrin β4 | pAb | Rabbit | β4-cyto | 1:400 | F. Giancotti |

| Integrin β4 | mAb | Rat | 346-11A | 1:25 | S. Kennel |

| Laminin EHS | pAb | Rabbit | 1:400 | Sigma | |

| Laminin α1 | mAb | Rat | 198 | 1:2 | L. Sorokin |

| Laminin α1 | pAb | Rabbit | 317 | 1:1000 | L. Sorokin |

| Laminin α2 | mAb | Rat | 4H8/2 | 1:100 | Alexis |

| Laminin α4 | pAb | Rabbit | 1:100 | J. Milner | |

| Laminin β2 | pAb | Rabbit | 1:100 | Santa Cruz | |

| Laminin γ1 | mAb | Rat | 1:500 | Chemicon | |

| MBP | mAb | Rat | 1:2 | V. Lee | |

| MBP | mAb | Mouse | 1:300 | Chemicon | |

| Neurofilament 160 kD | mAb | Mouse | NN18 | 1:200 | Chemicon |

| Neurofilament 200 kD | pAb | Rabbit | 1:400 | Chemicon | |

| Neurofilament | mAb | Rat | TA51 | 1:10 | V. Lee |

| p75NTR | pAb | Rabbit | 1:100 | Chemicon | |

| p75NTR

|

mAb

|

Rat

|

Ab8876

|

1:200

|

Abcam

|

mAb, Monoclonal antibody; pAb, polyclonal antibody.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was extracted from sciatic nerves and analyzed by Northern blot as described (Feltri et al., 1994), using the following cDNAs as probes: (1) the 630 bp mouse dystroglycan cDNA fragment described for in situ hybridization, (2) a full-length cDNA of rat P0 (Lemke and Axel, 1985), and (3) a full-length cDNA of rat glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Fort et al., 1985).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis

Sciatic nerves were dissected from 2- to 3-month-old dy2J homozygous or dy2J heterozygous littermates and used for RT-PCR as described (Feltri et al., 1999b), using the following primers: laminin α1: 5′-CACCCTGGACTTACGGCAGG-3′ and 5′-TTCGTTGTCTGCTCTGTAAG-3′ (Nguyet et al., 2001); GAPDH: 5′-GTATGACTCTACCCACGG-3′ and 5′-GTTCAGCTCTGGGATGAC-3′). Placentas from mouse embryos were used as positive controls.

Western blot analysis

Sciatic nerves were dissected from 2- to 3-month-old dy2J homozygous or dy2J heterozygous littermates and used for Western blot analysis as described (Wrabetz et al., 2000) with the following modifications: 60 μg of nerve homogenates was loaded on 5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, blotted, and stained using affinity-purified rabbit anti-laminin α1 (E3 fragment) antibodies (Durbeej et al., 1996). Homogenates from mouse kidneys were used as control, and equal loading of nerve homogenates was verified using mouse anti-neurofilament-M antibodies (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA).

Preparation of purified cell cultures

Neuronal cultures. Purified dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons were dissociated from E15.5 Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River) as reported previously (Kleitman et al., 1998). After excision, DRG neurons were trypsinized (0.25%; Invitrogen, San Giuliano Milanese, Italy) and mechanically dissociated. Cell suspension (approximately three DRG neurons) was plated as a drop onto 12 mm glass coverslips (Greiner) coated with rat collagen (0.2 mg/ml; Biomedical Technologies) in CB10 media, consisting of Eagle's Minimal Essential Medium (EMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Biological Industries Kibbutz), 5 mg/ml glucose (Sigma), and 50 μg/ml crude nerve growth factor (NGF) (Harlan or Calbiochem). To remove non-neuronal cells, CB10 media was alternated every 2 d with E2F media for the first 12 d. E2F media contained EMEM supplemented with 4 mg/ml glucose, 5 μg/ml insulin (Sigma), 10 μg/ml rat transferrin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), 100 μm putrescine (Sigma), 20 nm progesterone (Sigma), 30 nm sodium selenite (Sigma), 10 μm 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (Sigma), 10 μm uridine (Sigma), and 50 ng/ml NGF.

SC cultures. SCs were prepared from sciatic nerves of P3 Sprague Dawley rats by the method of Brockes et al. (1979) and expanded as described (Feltri et al., 1992).

Neuron–SC cocultures

After neuronal seeding (2.5 weeks), SCs were added to coverslips (75,000 each). Cocultures were maintained in medium consisting of DMEM/F12 (1:1 vol), 5 mg/ml glucose, 5 μg/ml insulin, 10 μg/ml rat transferrin, 100 μm putrescine, 20 nm progesterone, 30 nm sodium selenite, and 50 ng/ml NGF for 1 week. To initiate myelination, cocultures were treated with EMEM, 15% FCS, 5 mg/ml glucose, and 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma).

Electron microscopy

Transgenic mice and age-matched controls were killed at P28 and 6 months old for semithin and ultrathin analysis, as described (Quattrini et al., 1996; Wrabetz et al., 2000).

Image analysis

Micrographs were digitalized using an AGFA Arcus 2 scanner, and figures were prepared using Adobe Photoshop Version 5.0.

Results

α6β1 is the major laminin receptor synthesized by SCs during embryogenesis

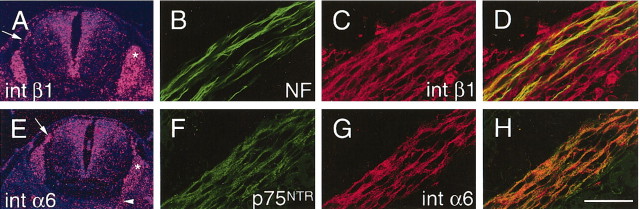

To study laminin receptors in the SC lineage, we examined the expression of α6, β1, β4 integrin subunits and DG by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry in mouse embryos beginning at E12.5. Anti-neurofilament antibodies were used to identify nerves. At E12.5, we only detected expression of α6 and β1 integrin, both at the level of message (Fig. 1, A and E, respectively), and protein (data not shown) in DRG, sensory and motor roots, and peripheral nerves. Identical results were observed at E15.5 for α6 and β1 (Fig. 1B–D,F–H) (and data not shown). Double staining with neurofilament (NF) and a marker for SCs or their precursors (p75NTR receptor) demonstrated that α6 and β1 were expressed in both axons and glial cells (Fig. 1B–D,F–H) (and data not shown). β4 integrin and DG were not detected at the level of message or protein at E12.5 or E15.5 in the PNS (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Expression of β1 and α6 integrin subunits in early PNS development. Cross sections of wild-type E12.5 mice (A, E) showing spinal cord, DRG (asterisks), spinal roots (arrows), and peripheral nerves (arrowhead), and E15.5 mice (B–H) showing motor roots. DRG neurons, spinal roots, and spinal nerves showed mRNA expression of β1 (A) and α6 (E). Double staining of spinal roots for β1 or α6 with either NF (which identified axons) or p75NTR (which identified Schwann cell precursors) showed that β1 and α6 were present in Schwann cells and axons. As an example, B–D illustrate that β1 is present both in Schwann cells and in axons; colocalization of NF (B) and β1 (C) is merged in D. In F–H, the colocalization of p75NTR (F) and α6 (G) is shown merged in H. Scale bar: (in H) A, E, 50 μm; B–H, 300 μm.

The expression of DG briefly precedes and parallels myelination in the PNS

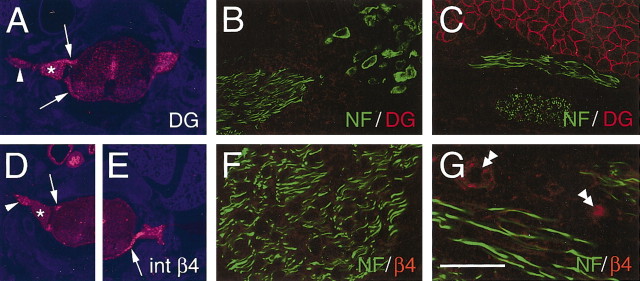

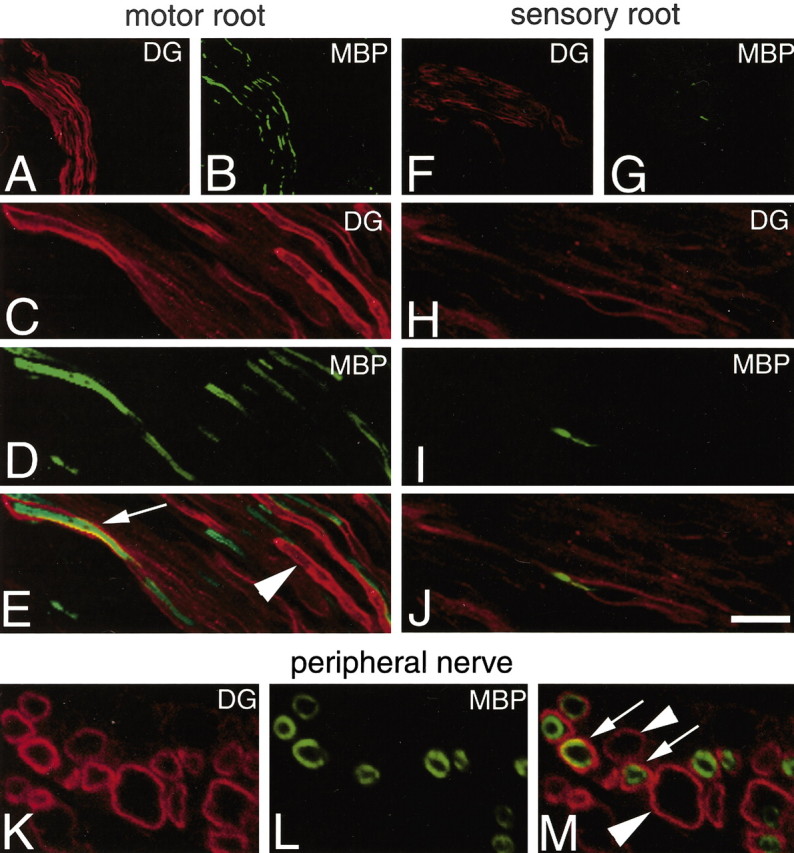

At E18.5, along with α6 and β1 message and protein (data not shown), we observed the onset of β4 integrin and DG mRNA expression in spinal roots, DRG, and nerve trunks (Fig. 2A,D,E); however, we could not yet detect β4 and DG protein (Fig. 2B,C,F,G). As internal positive controls, skeletal myofibers (Fig. 2C) stained for DG and blood vessels stained for β4 (Fig. 2G). Myelination occurs earlier in motor than sensory roots (Niebroj-Dobosz et al., 1980), and expression of myelin-specific mRNAs is detectable at P1 in motor but not sensory roots (Baron et al., 1994; Forghani et al., 2001). Thus, to correlate the onset of DG with the beginning of myelination, we stained motor and sensory roots at P1. As expected, motor roots were positive and sensory roots were mostly negative for MBP (Fig. 3B,D,G,I). Interestingly, DG staining was also stronger in motor than sensory roots (Fig. 3A,C,F,H). Analysis of the merged staining in the roots, and of single fibers by cross section in the nerve, showed that some fibers stained for both DG and MBP. The staining for DG was external to that of MBP (Fig. 3E,M) and appeared as a ring in cross sections (Fig. 3M), indicating that DG was immediately polarized at the ab-axonal surface of SCs. Other fibers were DG positive, with the same ring appearance, but MBP negative (Fig. 3M, arrowhead). This indicates that DG becomes polarized to the external SC surface (facing the basal lamina), just before the appearance of MBP. Because MBP protein is detectable when sheaths contain at least five to eight myelin lamellas (Hahn et al., 1987), these data suggest that DG appears and is polarized just before wrapping, in promyelinating SCs. At P5 and P15, expression of MBP and DG progressively increased in sensory roots and peripheral nerves to levels comparable with motor roots (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Expression of β4 integrin and β-DG in the PNS of E18.5 wild-type mice. Cross sections of whole-mount fetuses (A, D, E) including spinal cord, DRG (asterisk), spinal roots (arrows), and peripheral nerves (arrowheads). Magnification of motor roots (B, F) and intramuscular peripheral nerves (C, G) is shown. In situ hybridization showed β-DG (A) and β4 (D, E) mRNA expression in DRG, spinal roots, and spinal nerves. Double immunostaining for β-DG (red) and NF (green) or β4 (red) and NF (green) showed the absence of both DG and β4 proteins in motor roots (B, F) and peripheral nerves (C, G). As internal control, muscle stained positively for β-DG (C) and vessels stained positively for β4 (G, double arrowheads). Scale bar: (in G) A, D, E, 50 μm; B, C, F, G, 350 μm.

Figure 3.

Expression of β-DG protein in the PNS of P1 normal mice. Cryosections of motor roots (A–E), sensory roots (F–J), and peripheral nerve (K–M), double stained for β-DG and MBP. Onset of β-DG paralleled that of myelin proteins, beginning first in motor roots (compare A, B with F, G). β-DG was expressed with a polarized, ab-axonal pattern on the surface of myelinating SCs (MBP positive) (E, M, arrows). β-DG staining was also detectable with a similar ab-axonal (or ring) distribution in SCs still negative for MBP (E, M, arrowheads). Scale bar: (in J) A, B, F, G, 100 μm; C–E, H–J, 35 μm; K–M, 15 μm.

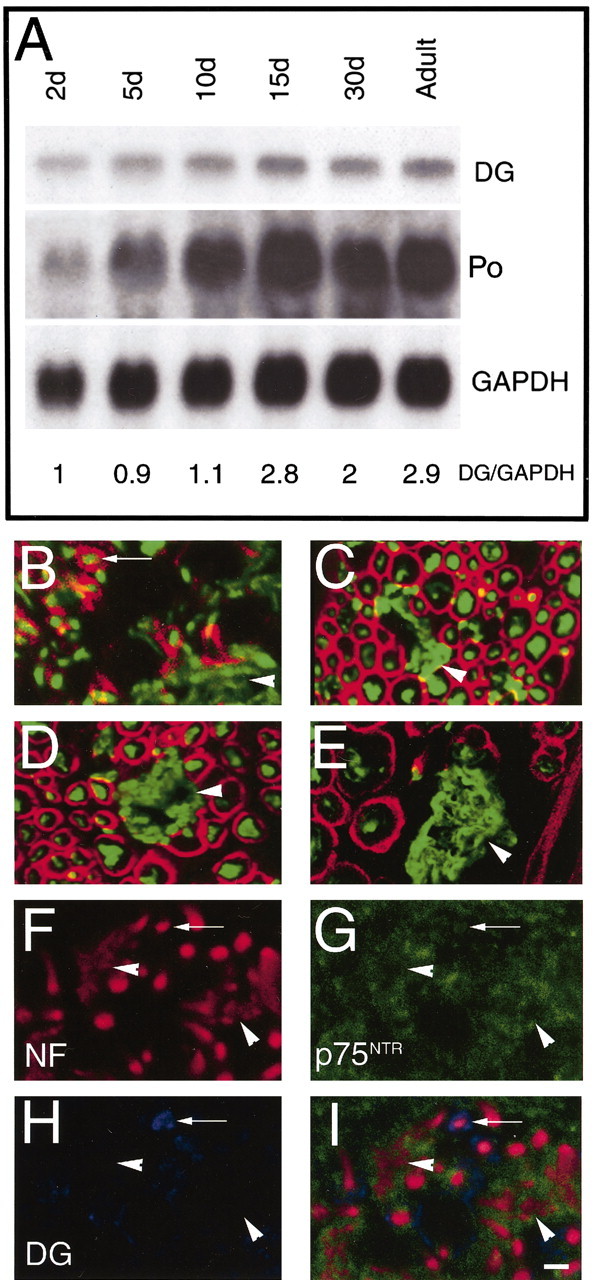

To further test the hypothesis that DG onset is in promyelinating SCs, we stained peripheral nerves at P1 for both NF and DG. As shown in Figure 4B, only SCs that surrounded a single axon (arrows) expressed DG. By the same logic, we stained mutant animals in which the absence of either laminin α2 or integrin β1 causes a subset of SCs to arrest at the stage of axonal sorting. We asked whether the SCs “frozen” at this developmental stage expressed DG. Indeed, SCs around bundles of unsorted axons (Fig. 8E) did not show any DG staining (Fig. 4C–E, arrowhead), whereas SCs containing only one axon expressed DG (Fig. 4C–E). To directly visualize ensheathing, DG-negative SCs, we triple stained P1 sciatic nerves for DG, NF, and p75NTR receptor. As shown in Figure 4F–I, axon bundles are surrounded by DG-negative, p75NTR-positive SCs (arrowhead), whereas some single axon are surrounded by a DG-positive SC (arrow), which has already downregulated p75NTR.

Figure 4.

Expression of DG in postnatal development and relative to SC–axonal relationships. A, Northern analysis of DG, P0 glycoprotein, and GAPDH expression in developing rat sciatic nerve. The ages of the rats are indicated above the lanes. The blot was successively hybridized with 32P-labeled cDNA probes for DG, P0, and GAPDH and exposed to film for 48, 3, and 24 hr, respectively. DG mRNA levels were low at P2 and P5 and rose at P15, similarly to a myelin gene, P0. GAPDH signal demonstrates equal loading of the RNA (10 μg total RNA per lane). Densitometric values of DG/GAPDH ratios are indicated at the bottom of each lane, relative to the P2 value arbitrarily indicated as 1. B–E, Cryosections of P1 normal mouse nerve (B), adult dy2J motor root (C), sciatic nerve (D), and adult β1-null sciatic nerve (E) double stained for NF (green) and DG (red). During development, only SCs around single axons express DG (B, arrow). Similarly in laminin α2-deficient or integrin β1-deficient mature PNS, only single axons in the mutant mice are surrounded by DG staining, whereas unsorted axons (C, D, E, arrowheads) are not surrounded by DG staining. F–G, cryosections of normal P1 mouse nerve, triple stained for NF (red), DG (blue), and p75NTR (green). SCs identified by staining with anti-p75NTR antibodies surround bundles of axons (stained by anti-NF antibodies; arrowhead) and do not express DG; in contrast only SCs in a 1:1 relationship with axons lose p75NTR and begin to express DG (arrow). Other Schwann cells associated with single axons are in a transition state, with p75NTR still detectable and DG synthesis just beginning. Scale bar: B, C, F–I, 10 μm; D, E, 12μm.

Figure 8.

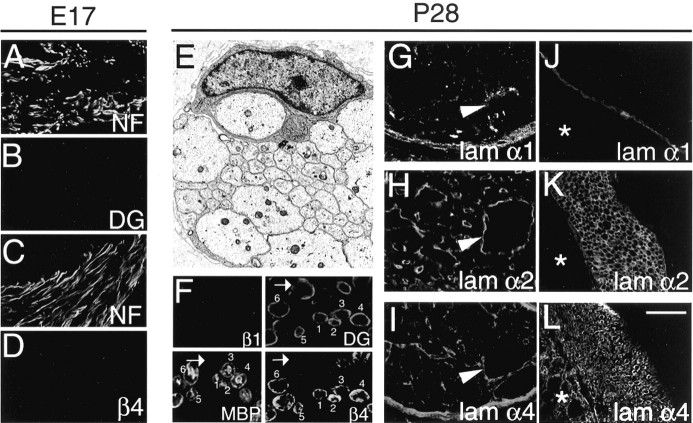

Consequences of deletion of β1 integrin in Schwann cells on the expression of laminins and their receptors. A–L, Ultrathin (E) and cryosections (A–D, F–L) of sciatic nerves from E17.5 (A–D) and P28 (E–I) and motor roots from P28 (J–L) conditional β1-null mice. In E, an electron micrograph of a bundle of unsorted axons of mixed caliber surrounded by a Schwann cell is shown. In A–D, expression of DG (B) and β4 (D) was not prematurely induced in embryonic β1-null nerves identified by neurofilament staining (A, C). In F, an area from a cross section of a P28 sciatic nerve showing MBP-positive and -negative fibers is shown. MBP and β1 integrin are double stained on one section; DG and β4 integrin are double stained on a serial section. MBP(+) fibers (marked 1–6) showed DG and β4 positivity. Incontrast, MBP(–)fibers (arrow) of ten expressed DG but usually not β4 (arrow). Laminin chains α2 and α4 were expressed in the endoneurium of sciatic nerves (G–I) and in motor roots (J–L). Laminin chains were present around, but not within, bundles of unsorted axons (arrowhead). Laminin α1 was also detected around axonal bundles in sciatic nerve (see Results). Asterisk identifies spinal cord. Scale bar: (inL) A–D, 40 μm; E, 2.5μm; F, 20μm; G–L, 80μm.

To determine whether the levels of DG expression were regulated during postnatal development, we performed Northern blot analysis of developing rat sciatic nerve, from P2 to adulthood. Figure 4A shows that the steady-state levels of DG mRNA increased between P10 and P15, in parallel with the increase of myelin mRNAs, such as P0 (Fig. 4). Thus, the perinatal appearance and rise of DG protein is likely transcriptionally regulated during myelination, similar to β4 integrin (Feltri et al., 1994).

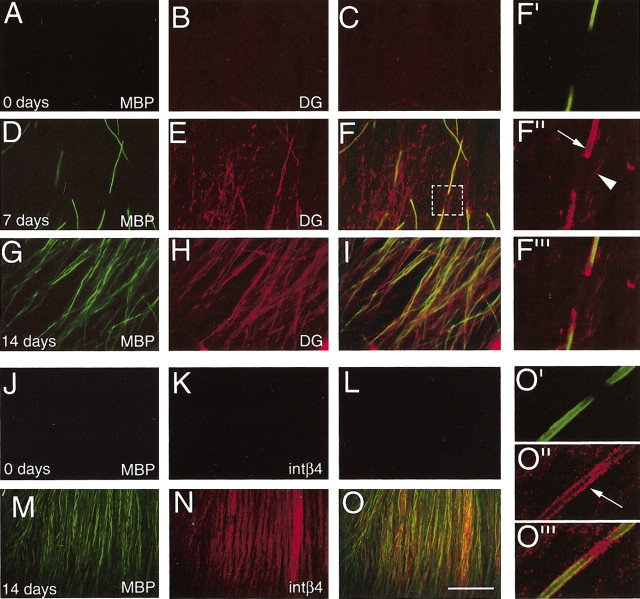

To correlate the appearance of DG with myelination in a more synchronized system, we stained rat SC–neuron cocultures (for review, see Bunge, 1993) in which the onset of myelination is triggered by the addition of ascorbic acid (Bunge, 1993). No DG staining was found when SCs were either cultured alone or cocultured with DRG neurons in non-myelinating medium (Fig. 5A–C). Only α6 and β1 integrins were detectable on SCs (data not shown). Staining for DG appeared in SCs 3 d after addition of ascorbic acid, when a minority of fibers also stained for MBP. Again, DG staining preceded and paralleled MBP expression and appeared outside the MBP-stained myelin sheaths (shown at 7 d) (Fig. 5D–F, F′–F‴, arrow). As we observed in vivo, DG was polarized even in MBP-negative fibers (F″, arrowhead). DG staining extended longitudinally in the paranodal region (F″–F‴). The in vivo and in vitro data indicate that DG expression immediately precedes myelination in single fibers.

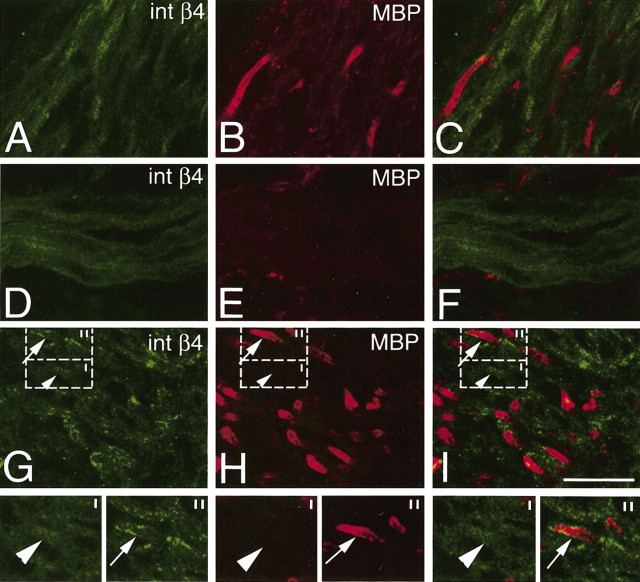

Figure 5.

Expression of β-DG and β4 integrin in Schwann cell–neuron cocultures. Primary rat Schwann cells were seeded onto cultures of dissociated sensory neurons. Ascorbic acid was added at day 0 to promote myelination. At day 0 (A–C, J–L), day 7 (D–F), and day 14 (G–I, M–O), cultures were fixed and double immunostained for MBP (A, D, G, J, M, F′, O′) and β-DG (B, E, H, F″) or β4 (K, N, O″). Merges are shown in C, F, I, L, O, F‴, and O‴). At day 0, MBP, DG, and β4 were not expressed (A–C, J–L). At day 7, MBP and DG were expressed in few fibers (D–F). DG was expressed at the ab-axonal surface of few Schwann cells, both in the absence of MBP staining or externally to MBP and in paranodal regions (F′–F‴; arrow indicates a DG + MBP + fiber; arrowhead indicates a DG + MBP – fiber). At day 14, the number of fibers MBP + DG + (G–I) increased. β4 staining was diffuse and weak in MBP-negative fibers but more intense and polarized in MBP-positive fibers (O′–O‴, arrow). Scale bar: (in O) A–O, 100 μm.

Polarized expression of integrin α6β4 occurs after onset of myelination

Next, we determined the onset of β4 integrin synthesis. At P1, we observed a faint and diffuse expression of β4 protein in spinal roots and peripheral nerves (Fig. 6). The diffuse staining of β4 preceded myelination but did not correlate with its onset, because there were no differences in β4 expression between sensory and motor roots (Fig. 6A,D). β4 staining became stronger only after MBP appeared in a single fiber and polarized outside the compact myelin sheath, resembling its mature ab-axonal distribution [Fig. 6G–I, compare left (′) with right (″) magnified insets].

Figure 6.

Expression of β4 integrin protein in the PNS of normal P1 mice. Cryosections of motor roots (A–C), sensory roots (D–F), and peripheral nerves (G–I) double stained for β4 and MBP. Insets below magnify the boxed areas in G–I. β4 was present at low levels in MBP-negative Schwann cells (magnified in left insets and identified by prime sign). β4 acquired a clearly polarized, ab-axonal expression only in MBP-positive Schwann cells (magnified in right insets and identified by double prime signs). Scalebar: (in I) A–I, 30 μm.

In vitro, SCs alone or cultured with DRG neurons under non-myelinating conditions expressed negligible amounts of β4 (Fig. 5J–L). After adding myelin-promoting medium, β4 integrin staining was low in MBP-negative fibers but stronger and polarized in MBP-positive internodes (Fig. 5M–O, O′–O‴) (and data not shown), in agreement with the findings of Einheber and co-workers (1993). Thus, these data confirm the in vivo observation that both DG and β4 integrin are expressed just before myelination, but β4, in contrast to DG, is not polarized until myelin synthesis begins.

Expression of α2, α3, and α7 integrin

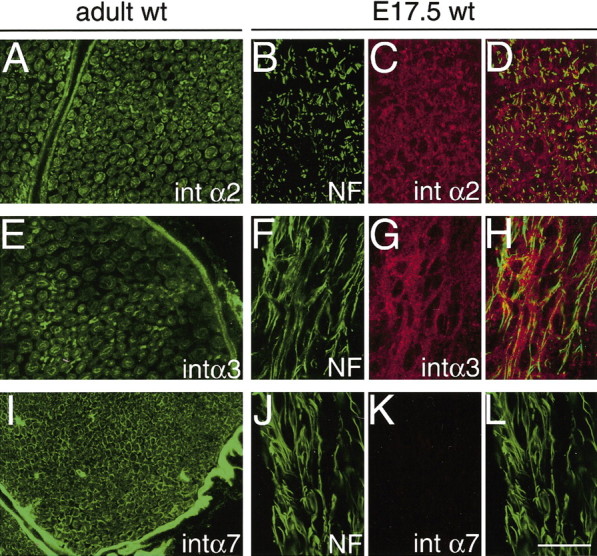

So far we focused on pure laminin receptors, but other laminin receptors expressed by SCs include α1β1 integrin, a dual collagen–laminin receptor expressed by non-myelin-forming SCs in mature nerves (Stewart et al., 1997), α2β1 integrin (Hsiao et al., 1991; Milner et al., 1997), which binds collagen, laminin, or tenascin depending on the cell type (Santoro, 1986; Elices and Hemler, 1989; Languino et al., 1989), and α7β1 integrin. We therefore looked at the expression of α2, α3, and α7 integrin during nerve development. We found that SCs expressed very low levels of α2 and α3 integrin subunits, and their expression did not change during development (Fig. 7). α7 integrin instead is synthesized by SCs in mature nerves (Fig. 7I) but not in fetal nerves (Fig. 7J–L) and appears 1 or 2 d after myelination begins in postnatal nerves (Previtali et al., 2003).

Figure 7.

Expression of α2, α3, and α7 integrin subunits in PNS development. Cryosections of peripheral nerves of adult (A, E, I) and E17.5 (B–L) mice were double labeled with neurofilament (B, F, J) and anti-α2 (A, C), α3 (E, G), or α7 (I, K) integrin antibodies. Low levels of α2 and α3 staining are present in fetal and adult nerves, whereas α7 integrin is absent in fetal SCs but robustly synthesized by adult SCs. Scale bar: (in L) A–L, 50 μm.

Compensation by laminins or their receptors

In adult β1-null sciatic nerves, most axons are grouped in large unsorted bundles, resembling the bundles normally found in fetal nerves (Fig. 8E) (Martin and Webster, 1973; Feltri et al., 2002) and in roots of dystrophic mice (Bradley and Jenkison, 1973). Interestingly, β1-null roots are less affected than nerves (Feltri et al., 2002), whereas dystrophic roots are more affected than nerves. The differential expression of laminin-2 receptors could explain why laminin-2 alterations produce variable effects across development. However, diverse receptor function cannot account for the varying topography of the phenotypes within laminin-2 and β1 integrin mutants (roots ≠ nerves) and between them (roots worse in dystrophic; nerves worse in β1-null). To investigate this question, we searched for compensatory expression of laminins or their receptors in dystrophic or β1-null roots and nerves.

No compensatory mechanisms protect prenatal SCs from the absence of β1 integrins

β1-null nerves manifest more axonal sorting defects in nerves than spinal roots; however, the expression of neither DG nor β4 integrin was upregulated in either β1-null roots (data not shown) or nerves (Fig. 8A–D) before birth, when axonal sorting normally occurs. Not surprisingly, expression of α2, α3, and α7 integrin, which normally pair only with β1, is similarly not upregulated before birth in β1-null nerves (data not shown). Thus, compensation by these laminin receptors does not explain the difference between β1-null nerves and roots.

Laminin receptors may cooperate during myelination

After birth in β1-null nerves, a few SCs achieve a one-to-one relationship with axons and proceed to form myelin, albeit with delay. The few SCs that myelinated axons were clearly β1-negative (Fig. 8F) (Feltri et al., 2002). To explore the expression of DG and β4 integrin in promyelinating versus myelinating β1-null Schwann cells, we first stained cross sections of β1-null nerves with neurofilament and then asked whether single axons were surrounded by DG, β4 integrin, or MBP-positive SCs. Almost 70% of single axons were surrounded by a DG-positive SCs (378 fibers double stained with DG and NF out of 540 NF-positive fibers; data not shown). Using serial sections in which DG-positive fibers were recognizable, we determined that among the DG-positive fibers, 30% were MBP positive and 70% were MBP negative. Interestingly, the MBP-positive fibers were always β4 positive (Fig. 8F, 1–6), whereas MBP-negative fibers were almost always β4 negative (Fig. 8F, arrow). Only 1–2% of fibers DG positive and MBP negative were faintly β4 positive (data not shown). These data suggest that all three receptors cooperate in myelination, because in the absence of β1, integrin myelination is possible but delayed, and the presence of both α6β4 and DG correlates with myelination in β1-null SCs.

Laminins in β1-null nerves

Because β1 integrin, in association with DG, has been proposed to play a role in BL organization in other tissues (Henry et al., 2001), we investigated the effects of β1 deletion on laminins. Normally, the endoneurium contains laminin chains α2, low levels of α4, β1, and γ1, and the perineurium contains α1, α4, α5, β1, β2, and γ1. Laminin chains α2, low levels of α4, and γ1 were present in the endoneurium of β1-null nerves, around single fibers and around bundles of nonsorted axons (Fig. 8H,I) (and data not shown). Instead, α1 and β2 laminin chains were present in the perineurium but also in the endoneurium, primarily around bundles of unsorted axons (Fig. 8G) (and data not shown) where perineurial-like cells are abnormally present (Feltri et al., 2002). No laminins were detectable within the bundles of nonsorted axons (Fig. 8G–I) (and data not shown). Thus, no alteration in the organization of normal endoneurial laminins was detectable at this resolution, other than the presence of perineurial laminins. In spinal roots, laminin chains were present similarly to controls. Laminin chains α2, α4, and γ1 were detected around SCs, whereas α1, α4, and β2 chains were detected in meninges (Fig. 8J–L, compare Fig. 9A–C) (and data not shown).

Figure 9.

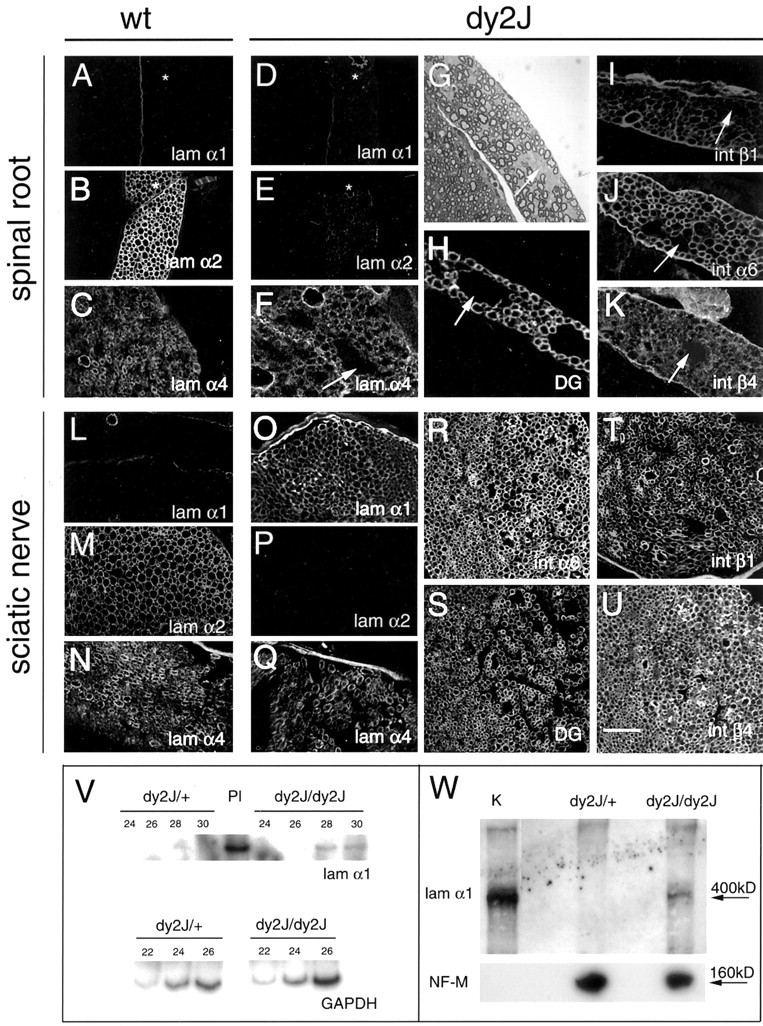

Expression of laminins and laminin receptors in the PNS of dy2J mice. Cryosections of motor root (A–K) and the sciatic nerve (L–U) from wild-type (A–C, L–N) or dy2J mice (D–K, O–U) were immunostained for laminin chain α1 (A, D, L, O), α2 (B, E, M, P), α4 (C, F, N, Q), and integrin subunit α6 (J, R), β1 (I, T), β4 (K, U), and β-DG (H, S). In both roots and sciatic nerve, the staining for α2 laminin chain was reduced in dy2J as compared with controls (compare B with E and M with P). The staining for α4 laminin chain was similar in dy2J and control mice. The α1 laminin chain was undetectable in spinal roots in both dy2J and controls, whereas it was upregulated in the sciatic nerve of dy2J mice (compare A with D and L with O). Laminin receptors were normally expressed in the endoneurium of dy2J mice (H–K, R–U). V, RT-PCR analysis of laminin α1 expression. Total RNA was extracted from either homozygous (dy2J/dy2J) or heterozygous (dy2J/+) dystrophic sciatic nerves and from mouseplacenta (Pl) as positive control. cDNA was synthesized and amplified with GAPDH-specific primers using 32P-αdCTP. On the basis of quantitative autoradiography for GAPDH product, equal amounts of cDNA template were reamplified with primer pairs specific to laminin α1. Laminin primers amplify the expected 201 nucleotide band in placenta and in dystrophic nerves but not in heterozygous control nerves. Cycles of amplification are indicated by 22, 24, 26, 28 and 30. W, Western blot analysis of laminin α1 expression. Homogenates from mouse kidney (K) as a source of laminin 1 and from either homozygous (dy2J/dy2J) or heterozygous (dy2J/+) dystrophic sciatic nerves were detected by anti-laminin α1 antibodies, and anti-NF-M antibodies were used to show equal loading of the nerve samples. Low levels of laminin α1 are present in dystrophic nerves but not in heterozygous control nerves. Scale bar: (in U) A–U, 50 μm.

Laminin receptors and laminins in dystrophic roots and nerves

Dystrophic mice show failure of axonal sorting that is more severe in the spinal roots than in distal PNS. This regional difference in severity could be attributable to a differential function of laminin-2 in roots versus nerves, e.g., via interaction with different receptors in the two locations. To address this, we asked whether the expression of laminin receptors was different in roots versus nerves of normal and dystrophic animals. We found no differences in the expression of α6, β1, and β4 integrin or DG in spinal roots and peripheral nerves of both wild-type and dy2J mice (Fig. 9G–J,Q–T) (and data not shown). Although the activation state of the receptors, particularly in dy2J mice, cannot be evaluated by this technique, our data do not support the hypothesis that laminin has a different function in roots versus nerves.

Increased laminin-1 in sciatic nerve but not roots of dy2J mice

An alternative explanation for the regional differences observed in dystrophic mice is that another laminin compensates for the lack of laminin-2 in nerves but not roots of dystrophic mice. Thus, we compared the expression of laminin α chains in the roots and peripheral nerves of normal and dy2J mice.

In the spinal roots and sciatic nerves of wild-type mice, we found expression of laminin α2, with low levels of α4 in the endoneurium (Fig. 9B,C,M,N). Laminin α1 was restricted to the perineurium and meninges (Figs. 9A,L). In dy2J mice, immunostaining of α2 chain was reduced, as reported previously (Sunada et al., 1995). Interestingly, α1 laminin chain was upregulated in the endoneurium of sciatic nerves but not in roots of dy2J mice (Fig. 9, compare A with D, L with O). This upregulation was confirmed by semiquantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analysis. Figure 9, V and W, shows that message and protein for α1 laminin chain were detectable in dy2J homozygous but not dy2J heterozygous sciatic nerves. Thus, compensation by laminin receptors does not explain the difference between roots and nerves in β1-null animals, but compensation by laminins may well explain this difference in dystrophic mice.

Discussion

Laminin-2 deficiency causes several alterations in PNS development, probably mediated by interaction with different receptors in SCs. We show that laminin receptors have a hierarchy of expression, positioning them as possible downstream effectors of laminin-2 at different times. Also, we show that laminin-1 may compensate for the deficiency of laminin-2 in distal nerves but not roots of dystrophic mice. In contrast, redundancy and compensation of laminin receptors play no role in prenatal development, whereas cooperation among receptors may allow myelination postnatally. These data are necessary to interpret the results of gene inactivation experiments and to produce working hypotheses that such experiments can test.

Integrin α6β1 is the first laminin receptor expressed by SCs

We show that α6β1 is the major laminin receptor expressed by precursors and immature SCs, in addition to α2β1. The exclusive expression of β1 integrins prenatally explains why SCs are incapable of sorting axons in fetal β1-null nerves. Because this phenotype strongly resembles the proximal PNS of dystrophic mice, binding of laminin-2 is likely required in early SC–axon interactions. Loss-of-function experiments have not shown an obvious role for α1 and α7 integrins in PNS and were not informative because of early lethality for integrin α2 (De Arcangelis and Georges-Laboeusse, 2000; Previtali et al., 2003). Thus, α6β1 integrin is likely the receptor involved in this process; however, because many other α partners such as α4 and α5 dimerize with β1 in SCs, we cannot exclude the possibility that receptors for other extracellular matrix components are involved. Conditional inactivation of α6 integrin in SCs will test this hypothesis.

DG and the onset of myelination

Myelination requires cytoskeletal rearrangements in SCs as they advance the mesaxon, eliminate cytoplasm from spirals, and compact myelin. We observed that DG appears in a SC just before initiation of myelination. Similarly to myelin proteins, DG was detected first in motor and then in sensory fibers (Fig. 3) (Baron et al., 1994; Forghani et al., 2001). The polarized pattern of DG expression, with a single axon within the DG ring, suggested that SCs express DG at the promyelinating stage. Also, we show that during myelination, DG mRNA expression is upregulated. These data extend previous reports on DG expression in mature SCs (Yamada et al., 1994, 1996) and agree with recent data by Masaki et al. (2002) who reported continuous DG staining by immunoelectron microscopy beginning in SCs in a one-to-one relationship with axons. It is possible that DG is important for the onset of myelination. Indeed DG interacts with utrophin, Dp116 (Saito et al., 1999), DRP-2, and periaxin, and both periaxin mutations and conditional inactivation of DG in SCs cause a dysmyelinating neuropathy (Saito et al., 2003).

α6β4 integrin distribution correlates with later events of myelination.

α6β4 integrin is required for the assembly of hemidesmosomes in epithelial cells to stabilize a link between the cytoskeleton and the BL (Nievers et al., 1999). Several authors suggested a correlation between α6β4 expression and myelination. β4 is polarized to the ab-axonal surface of SCs, parallels myelination in vivo and in vitro, and is induced by axonal contact in development and regeneration (Einheber et al., 1993; Feltri et al., 1994; Quattrini et al., 1996). β4-negative SCs from null mice form rudimental myelin in SC–neuron cocultures (Frei et al., 1999), however, suggesting that α6β4 is not strictly required for the onset of myelination. We show that shortly before myelination, β4 staining was weak and diffuse, whereas after the beginning of myelin synthesis it was stronger and polarized. Thus, α6β4 may stabilize the link-age of the BL to SCs by participating in a specialized adhesion system similar to hemidesmosomes for epithelia. The generation of mice null for β4 in SCs will address this.

Redundancy and compensation

Redundancy, the presence of molecules with similar function, or compensation, the new expression of such molecules, may explain why inactivation of genes for extracellular matrix and their receptors often produces phenotypes less severe than expected (Hynes, 1996). We investigated redundancy and compensation in loss-of-function of laminin-2 and one of its receptors. In the receptor mutant, β1-null, we previously described defects in late fetal development. Here we show that only α6β1 integrin was normally present in SCs before birth, and there was no compensation by earlier expression of the other receptors, accounting for the severe defect. In contrast, we show that DG, α6β4, and α7β1 are coexpressed with α6β1 at various points after a normal SC reaches the promyelinating stage and that β1-null SCs can myelinate (with delay) when they express both DG and α6β4. Thus DG, α6β4, and possibly α6β1 and α7β1 probably cooperate in the formation of a myelin sheath, even if their function in myelination is partially redundant. Conditional inactivation of multiple receptors will be necessary to test these hypotheses.

Second, we investigated the expression of laminins and laminin receptors in dystrophic mice. Interestingly, we observed ectopic expression of laminin chain α1 in the endoneurium of dystrophic nerves but not in roots. This may explain the more severe sorting defect seen in roots and proximal nerves of dy2J mice when compared with their distal nerves, because new expression of laminin-1 may compensate for the function of laminin-2 in axonal sorting. Our data on α4 laminin agrees with those reported on roots but differs from data reported in nerves (Patton et al., 1997; Nakagawa et al., 2001), in that we found a similar amount of α4 staining in the endoneurium of normal nerves and dystrophic mice. Possibly this difference is attributable to the different districts examined (roots and sciatic nerves in our study vs intramuscular nerves in their studies) or the different allelic variants of dystrophic mice (dy2J/dy2J in our study vs dy/dy and dy3k/dy3k in their studies).

BL assembly in SCs

Polymerization of laminin triggers assembly of the BL and induction of a matrix–receptor– cytoskeletal network that activates signaling (Colognato et al., 1999). Interaction between laminin and its receptors facilitates polymerization (Colognato and Yurchenco, 2000), and specific receptors, such as DG and β1 integrins, facilitate BL assembly, either directly (DiPersio et al., 1997; Henry and Campbell, 1998; Sasaki et al., 1998; Henry et al., 2001) or through the induction of laminin itself (Li et al., 2002). Tsiper and Yurchenko (2002) reported that DG is reorganized with laminin during assembly of BL of SCs in vitro, whereas β1 integrin mediates the formation of a fibrillar matrix organization, distinct from a BL and before real BL assembly. Although the SCs used in their study are removed from the physiological state of SCs in nerves (high passage number, absence of axons), these results are consistent with our observations and previous in vivo observations. In vivo, a discontinuous BL first appears before birth around “families” of SCs that surround bundles of axons (Ziskind-Conhaim, 1988; Masaki et al., 2002), whereas a continuous basal lamina appears only at birth (Webster et al., 1973). We show that only β1 integrins are present in SCs before birth, suggesting that they participate in the deposition of the immature BL at the time of axonal sorting. Consistent with this, sorting is impaired inβ1-null nerves; however, those β1-null SCs that generate myelin form an apparently normal BL. Therefore, β1 is not required for mature basal lamina formation. Instead, expression of DG first, and then recruitment of α6β4, at P1 may facilitate the formation of the mature BL during myelination. In support of this, we show that DG and α6β4 onset coincide with the appearance of a mature basal lamina, that DG is first polarized to the outer surface of single SCs just before myelination, and that β4 integrin polarization follows the expression of DG and MBP. In conclusion, we postulate that β1 favors the deposition of the immature BL in families of premyelinating SCs, whereas DG organizes, and recruitment of α6β4 and α7β1 stabilizes, the mature BL in promyelinating and myelinating SCs.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Telethon Grants D93 (M.L.F.) and 1177 (L.W.), Progetto Finalizzato Ministero della Sanitá (M.L.F., L.W.), Multiple Sclerosis Society of Great Britain (L.W.), Fondazione Italiano Sclerosi Multipla (L.W.), National Institutes of Health Grants NS 41319 (L.W.) and NS45630 (M.L.F.), and Amici Centro Sclerosi Multipla (S.C.P., A.Q.). We thank C. Ferri and M. Fasolini for excellent technical assistance, Dr. G. Zanazzi for help with cocultures, Alembic for confocal microscopy, and Drs. A. Sonnenberg (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), V. Quaranta (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), V. Lee (University of Pennsylvania Medical School, Philadelphia, PA), K. Rubin (Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden), S. J. Kennel (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN), F. Giancotti (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY), L. Sorokin (University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Erlangen, Germany), J. H. Miner (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO), U. Majer (School of Biological Sciences, Manchester, UK), and K. Campbell (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) for the gift of antibodies.

Correspondence should be addressed to M. Laura Feltri, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, DIBIT, Via Olgettina 58, 20132 Milan, Italy. E-mail: feltri.laura@hsr.it.

Copyright © 2003 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/03/235520-11$15.00/0

References

- Baron P, Shy M, Honda H, Sessa M, Kamholz J, Pleasure D ( 1994) Developmental expression of P0 mRNA and P0 protein in the sciatic nerve and the spinal nerve roots of the rat. J Neurocytol 23: 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerkoel C, Takashima H, Wtankiewicz P, Garcia C, Leber S, Rhee-Morris L, Lupski J ( 2001) Periaxin mutations cause recessive Dejerine-Sottas neuropathy. Am J Hum Genet 68: 325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley W, Jenkison M ( 1973) Abnormalities of peripheral nerves in murine muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Sci 18: 227–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley W, Jaros E, Jenkison M ( 1977) The nodes of Ranvier in the nerves of mice with muscular dystrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 36: 797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockes J, Fields K, Raff M ( 1979) Studies on cultured rat Schwann Cells. I. Establishment of purified populations from cultures of peripheral nerve. Brain Res 165: 105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner-Fraser M, Artinger M, Muschler J, Horwitz A ( 1992) Developmentally regulated expression of a6 integrin in avian embryos. Development 115: 197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge MB ( 1993) Schwann cell regulation of extracellular matrix biosynthesis and assembly. In: Peripheral neuropathy (Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Griffin J, Low PA, Poduslo JF, eds), pp 299–316. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

- Colognato H, Yurchenco P ( 2000) Form and function: the laminin family of heterotrimers. Dev Dyn 218: 213–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato H, Winkelmann D, Yurchenco P ( 1999) Laminin polymerization induces a receptor-cytoskeleton network. J Cell Biol 145: 619–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Arcangelis A, Georges-Laboeusse E ( 2000) Integrin and extracellular matrix functions. Trends Genet 16: 389–395.10973067 [Google Scholar]

- DiPersio CM, Hodivala-Dilke KM, Jaenisch R, Kreidberg JA, Hynes RO ( 1997) alpha3beta1 integrin is required for normal development of the epidermal basement membrane. J Cell Biol 137: 729–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbeej M, Fecker L, Hjalt T, Zhang HY, Salmivitra K, Klein G, Timpl R, Sorokin L, Ebendal T, Ekblom P, Ekblom M ( 1996) Expression of laminin α1, α5 and β2 chains during embryogenesis of the kidney and vasculature. Matrix Biol 15: 397–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einheber S, Milner T, Giancotti F, Salzer J ( 1993) Axonal regulation of Schwann cell integrin expression suggests a role for α6β4 in myelination. J Cell Biol 123: 1223–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elices M, Hemler M ( 1989) The human VLA-2 is a collagen receptor on some cells and a collagen/laminin receptor on others. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 9906–9910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti J, Campbell K ( 1993) A role for the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex as a transmembrane linker between laminin and actin. J Cell Biol 122: 809–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri M, Scherer S, Wrabetz L, Kamholz J, Shy M ( 1992) Mitogen-expanded Schwann cells retain the capacity to myelinate regenerating axons after transplantation into rat sciatic nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 8827–8831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri M, D'Antonio M, Previtali S, Fasolini M, Messing A, Wrabetz L ( 1999a) Po-Cre transgenic mice for inactivation of adhesion molecules in Schwann cells. Ann NY Acad Sci 14: 116–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri M, D'Antonio M, Quattrini A, Numerato R, Arona M, Previtali S, Chiu S, Messing A, Wrabetz L ( 1999b) A novel P0 glycoprotein transgene activates expression of lacZ in myelin-forming Schwann cells. Eur J Neurosci 11: 1577–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri M, Graus-Porta D, Previtali S, Nodari A, Migliavacca B, Cassetti A, Littlewood-Evans A, Reichardt L, Messing A, Quattrini A, Mueller U, Wrabetz L ( 2002) Conditional disruption of beta1 integrin in Schwann cells impedes interactions with axons. J Cell Biol 156: 199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri ML, Scherer SS, Nemni R, Kamholz J, Vogelbacker H, Oronzi Scotti M, Canal N, Wrabetz L ( 1994) β4 integrin expression in myelinating Schwann cells is polarized, developmentally-regulated and axonally-dependent. Development 120: 1287–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Valle C, Gwynn L, Wood P, Carbonetto S, Bunge M ( 1994) Anti β1 integrin antibody inhibits Schwann cell myelination. J Neurobiol 25: 1207–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort P, Marty L, Piechaczyk M, el Sabrouty S, Dani C, Jeanteur P, Blanchard J ( 1985) Various rat adult tissues express only one major mRNA species from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase multigenic family. Nucleic Acids Res 13: 1431–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei R, Dowling J, Carenini S, Fuchs E, Martini R ( 1999) Myelin formation by Schwann cells in the absence of beta4 integrin. Glia 3: 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie C, Sherman D, Fleetwood-Walker S, Cottrell D, Tait S, Garry E, Wallace V, Ure J, Griffiths J, Smith A, Brophy P ( 2000) Peripheral demyelination and neuropathic pain behavior in periaxin-deficient mice. Neuron 26: 523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graus-Porta D, Blaess S, Senften M, Littlewood-Evans A, Damsky C, Huang Z, Orban P, Klein R, Schittny JC, Mueller U ( 2001) b1-class integrins regulate the development of laminae and folia in the cerebral and cerebellar cortex. Neuron 31: 367–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilbot A, Williams A, Ravise N, Verny C, Brice A, Sherman D, Brophy P, LeGuern E, Delague V, Bareil C, Magarbane A, Claustres M ( 2001) A mutation in periaxin is responsible for CMT4F, an autosomal recessive form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Hum Mol Genet 10: 415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn A, Whitaker J, Kachar B, Webster H ( 1987) P2, P1, and P0 myelin protein expression in developing rat sixth nerve: a quantitative immunocytochemical study. J Comp Neurol 260: 501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry M, Campbell K ( 1998) A role for dystroglycan in basement membrane assembly. Cell 95: 859–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry M, Satz J, Brakebusch C, Costell M, Gustafsson E, Faessler R, Campbell K ( 2001) Distinct roles for dystroglycan, β1 integrin and perlecan in cell surface laminin organization. J Cell Sci 114: 1137–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao L, Peltonen J, Jaakkola S, Grainick H, Uitto J ( 1991) Plasticity of integrin expression by nerve-derived connective tissue cells. J Clin Invest 87: 811–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO ( 1996) Targeted mutations in cell adhesion genes: what have we learned from them? Dev Biol 180: 402–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaros E, Bradley W ( 1979) Atypical axon-Schwann cell relationships in the common peroneal nerve of the dystrophic mouse: an ultrastructural study. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 5: 133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR, Mirsky R ( 1999) Schwann cells and their precursors emerge as major regulators of nerve development. Trends Neurosci 22: 402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleitman N, Wood P, Bunge R ( 1998) Tissue culture methods for the study of myelination. In: Culturing nerve cells (Banker G, Goslin K, eds), pp 545–594. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- Kuang W, Xu H, Vachon P, Liu L, Loechel F, Wewer U, Engvall E ( 1998) Merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest 102: 844–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Languino L, Gehlsen K, Wayner E, Carter W, Engvall E, Ruoslahti E ( 1989) Endothelial cells use alpha 2 beta 1 integrin as a laminin receptor. J Cell Biol 109: 2455–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke G, Axel R ( 1985) Isolation and sequence of a cDNA encoding the major structural protein of peripheral myelin. Cell 40: 501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Harrison D, Carbonetto S, Fassler R, Smyth N, Edgar D, Yurchenco PD ( 2002) Matrix assembly, regulation, and survival functions of laminin and its receptors in embryonic stem cell differentiation. J Cell Biol 157: 1279–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JR, Webster Hd ( 1973) Mitotic Schwann cells in developing nerve: their changes in shape, fine structure, and axon relationship. Dev Biol 32: 417–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki T, Matsumura K, Saito F, Sunada Y, Shimizu T, Yorifuji H, Motoyoshi K, Kamakura K ( 2000) Expression of dystroglycan and laminin-2 in peripheral nerve under axonal degeneration and regeneration. Acta Neuropathol 99: 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki T, Matsumura K, Hirata A, Yamada H, Hase A, Arai K, Shimizu T, Yorifuji H, Motoyoshi K, Kamakura K ( 2002) Expression of dystroglycan and the laminin-alpha 2 chain in the rat peripheral nerve during development. Exp Neurol 174: 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner R, Wilby M, Nishimura S, Boylen K, Edwards G, Fawcett J, Streuli C, Pytela R, ffrench-Constant C ( 1997) Division of labor of Schwann cell integrins during migration on peripheral nerve extracellular matrix ligands. Dev Biol 185: 215–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner J, Patton B, Lentz S, Gilbert DJ, Snider W, Jenkins N, Copeland N, Sanes J ( 1997) The laminin alpha chains: expression, developmental transitions, and chromosomal location of alpha1-alpha5, identification of heterotrimeric laminins 8–11, and cloning of a novel alpha3 isoform. J Cell Biol 137: 685–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Ikezoe K, Miyata Y, Nonaka I, Harii K, Takeda S ( 2001) Schwann cell myelination occurred without basal lamina formation in laminin α2 chain-null mutant (dy3K/dy3K) mice. Glia 35: 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyet NM, Bai Y, Mochitate K, Senior RM ( 2001) Laminin α-chain expression and basement membrane formation by MLE-15 respiratory epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282: 1004–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebroj-Dobosz I, Fidzianska A, Rafalwska J, Sawicka E ( 1980) Correlative biochemical and morphological studies of myelination in human onto-genesis. II. Myelination of the nerve roots. Acta Neuropathol 49: 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nievers M, Schaapveld R, Sonnenberg A ( 1999) The cytoplasmic tail of b4 also transmits signals that affect cell survival, proliferation, and migration. Matrix Biol 18: 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton B, Miner J, Chiu A, Sanes J ( 1997) Distribution and function of laminins in the neuromuscular system of developing, adult, and mutant mice. J Cell Biol 139: 1507–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podratz J, Rodriguez E, Windebank A ( 2001) Role of the extracellular matrix in myelination of peripheral nerve. Glia 35: 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previtali S, Feltri M, Archelos J, Quattrini A, Wrabetz L, Hartung H-P ( 2001) Role of integrins in the peripheral nervous system. Prog Neurobiol 64: 35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previtali SC, Quattrini A, Pardini C, Boncinelli E, Canal N, Wrabetz L ( 1999) The laminin receptor α6β4 integrin is highly expressed in ENU-induced glioma in rat. Glia 26: 55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previtali SC, Dina G, Nodari A, Cassetti A, Maier U, Wrabetz L, Feltri ML, Quattrini A ( 2003) Schwann cells express alpha7beta1 integrin, which is dispensable for peripheral nerve myelination. Mol Cell Neurosci, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Quattrini A, Previtali S, Feltri ML, Canal N, Nemni R, Wrabetz L ( 1996) β4 integrin and other Schwann cell markers in axonal neuropathy. Glia 17: 294–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito F, Masaki T, Kamakura K, Anderson L, Fujita S, Fukuta-Ohi H, Sunada Y, Shimizu T, Matsumura K ( 1999) Characterization of the transmembrane molecular architecture of the dystroglycan complex in Schwann cells. J Biol Chem 274: 8240–8246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito F, Moore S, Barresi R, Henry M, Messing A, Ross-Barta S, Cohn R, Williamson R, Sluka K, Sherman D, Brophy P, Schmelzer J, Low P, Wrabetz L, Feltri M, Campbell K ( 2003) Unique role of dystroglycan in peripheral nerve myelination, nodal structure, and sodium channel stabilization. Neuron, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sanes J, Engvall E, Butkowski R, Hunter D ( 1990) Molecular heterogeneity of basal laminae: isoforms of laminin and collagen IV at the neuromuscular junction and elsewhere. J Cell Biol 111: 1685–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro S ( 1986) Identification of a 160,000 Dalton platelet membrane protein that mediates the initial divalent cation-dependent adhesion of platelets to collagen. Cell 46: 913–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Forsberg E, Bloch W, Addicks K, Fassler R, Timpl R ( 1998) Deficiency of beta 1 integrins in teratoma interferes with basement membrane assembly and laminin-1 expression. Exp Cell Res 238: 70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman D, Fabrizi C, Gillespie C, Brophy P ( 2001) Specific disruption of a Schwann cell dystrophin-related protein complex in a demyelinating neuropathy. Neuron 30: 677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorer Z, Philpot J, Muntoni F, Sewry C, Dubowitz V ( 1995) Demyelinating peripheral neuropathy in merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy. J Child Neurol 10: 472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart HJS, Turner D, Jessen KR, Mirsky R ( 1997) Expression and regulation of α1β1 integrin in Schwann cells. J Neurobiol 33: 914–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling C ( 1975) Abnormalities in Schwann cell sheaths in spinal nerve roots of dystrophic mice. J Anat 119: 169–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunada Y, Bernier S, Utani A, Yamada Y, Campbell K ( 1995) Identification of a novel mutant transcript of laminin alpha2 chain gene responsible for muscular dystrophy and dysmyelination in dy2J mice. Hum Mol Genet 4: 1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiper MV, Yurchenco PD ( 2002) Laminin assembles into separate basement membrane and fibrillar matrices in Schwann cells. J Cell Sci 115: 1005–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster Hd, Martin JR, O'Connell MF ( 1973) The relationships between interphase Schwann cells and axons before myelination: a quantitative electron microscopic study. Dev Biol 32: 401–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrabetz L, Feltri M, Quattrini A, Imperiale D, Previtali S, D'Antonio M, Martini R, Yin X, Trapp B, Zhou L, Chiu S, Messing A ( 2000) P0 overexpression causes congenital hypomyelination of peripheral nerves. J Cell Biol 148: 1021–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Wu X-R, Wewer U, Engvall E ( 1994) Murine muscular dystrophy caused by a mutation in the laminin alpha2 (Lama2) gene. Nat Genet 8: 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Shimizu T, Tanaka T, Campbell K ( 1994) Dystroglycan is a binding protein of laminin and merosin in peripheral nerve. FEBS Lett 352: 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Chiba A, Endo T, Kobata A, Anderson L, Hori H, Fukuta-Ohi H, Kanazawa I, Campbell K, Shimuzu T, Matsumura K ( 1996) Characterization of dystroglycan-laminin interaction in peripheral nerve. J Neurochem 66: 1518–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziskind-Conhaim L ( 1988) Physiological and morphological changes in developing peripheral nerves of rat embryos. Brain Res 470: 15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]