Abstract

Background

Mast cells are implicated in allergic and innate immune responses in asthma, although their role in models using an allergen relevant for human disease is incompletely understood. House dust mite (HDM) allergy is common in asthma patients. Our aim was to investigate the role of mast cells in HDM-induced allergic lung inflammation.

Methods

Wild-type (Wt) and mast cell-deficient Kitw-sh mice on a C57BL/6 background were repetitively exposed to HDM via the airways.

Results

HDM challenge resulted in a rise in tryptase activity in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of Wt mice, indicative of mast cell activation. Kitw-sh mice showed a strongly attenuated HDM- induced recruitment of eosinophils in BALF and lung tissue, accompanied by reduced pulmonary levels of the eosinophil chemoattractant eotaxin. Remarkably, Kitw-sh mice demonstrated an unaltered capacity to develop lung pathology and increased mucus production in response to HDM. The increased plasma IgE in response to HDM in Wt mice was absent in Kitw-sh mice.

Conclusion

These data contrast with previous reports on the role of mast cells in models using ovalbumin as allergen in that C57BL/6 Kitw-sh mice display a selective impairment of eosinophil recruitment without differences in other features of allergic inflammation.

Key Words: Asthma, House dust mite, Mast cells, Eosinophils, Allergic lung inflammation

Introduction

Asthma is a disease characterized by episodes of reversible airway obstruction, dyspnea and wheezing. In Western countries asthma prevalence has reached 10% on average and remains to increase towards epidemic proportions [1]. The pathophysiology of asthma frequently involves a varying degree of allergen-induced lung inflammation that can be difficult to manage clinically and can lead to airway remodeling [2]. House dust mite (HDM) allergy - and subsequent HDM-induced allergic lung inflammation - is common in asthma patients: in most populations the majority of asthma patients are allergic for HDM [3, 4, 5]. Better understanding of the role of different cellular subsets contributing to HDM-induced allergic lung inflammation could lead to new anti-inflammatory treatment approaches.

Mast cells are resident tissue cells that are described to have important immunoregulatory functions in allergic lung inflammation and asthma [6, 7], but their precise involvement in HDM-induced allergic lung inflammation is not fully clarified [8]. Upon activation mast cells are able to release proinflammatory mediators such as histamine, tryptase, serotonin, heparin sulfates, lipid mediators, such as PGE2 and LTB4, and a vast range of interleukins [9, 10]. Mast cells can be activated by both IgE-dependent and IgE-independent pathways [8, 11]. A simplistic view of mast cells as ‘merely’ secretory proinflammatory and secretory cells has changed due to new insights in the involvement of mast cells in wound healing, UV irradiation protection, tumor biology [reviewed in [10]] and pulmonary fibrin and fibrinolysis homeostasis in asthma [reviewed in [12]]. Mast cell-deficient mice are a well-known tool for studying the role of mast cells in mouse asthma, but have not been investigated in a C57BL/6 strain-based model of HDM-induced allergic lung inflammation.

The hematopoietic system develops progenitor mast cells that further mature into mast cells at the target resident peripheral tissue. Mast cells especially reside around blood vessels, nerves and in epithelial organs such as the skin, gastrointestinal tract and lung [8, 10]. The expression of c-Kit tyrosine kinase receptor (CD117) on mast cells is essential for the appropriate development and proliferation of progenitor mast cells from the hematopoietic system [13]. Two genetic c-Kit mutant mouse strains have been investigated most frequently in asthma models: c-KitW/W-v and c-KitW-sh/W-sh (Kitw-sh) mice [14]. In contrast to Kitw-sh mice, which have an inversion mutation on chromosome 5 at the transcriptional site of c-Kit [15, 16], c-KitW/W-v mice have significant comorbidity (e.g. anemia, infertility, dermatitis, skin ulceration), which makes the latter mouse strain less suitable for asthma studies examining the role of mast cells.

Here, we investigated the impact of mast cell deficiency using mast cell-deficient Kitw-sh mice with a C57Bl/6 background in a recently developed HDM-evoked mouse asthma model [17]. We show that mast cell deficiency attenuated the recruitment of eosinophils and was associated with lower pulmonary levels of eotaxin. Remarkably, in this HDM-induced model C57Bl/6 mice that lack mast cells were able to develop increased mucus production and allergic lung pathology equivalent to Wt mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57Bl/6 wild-type (Wt) mice were purchased from Charles River Inc. (Maastricht, The Netherlands). Mast cell-deficient Kitw-sh on a C57Bl/6 background were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Me., USA), housed in standardized specific pathogen-free conditions, and sex and age matched. Experiments started when animals were 8-9 weeks old. Each group consisted of 8 mice (except for one of the Wt saline groups, n = 5; see figure legends). The Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Amsterdam approved all experiments.

HDM Asthma Model

HDM allergen whole body extract (Greer Laboratories, Lenoir, N.C., USA), derived from the common European HDM species Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Der p, was used to induce allergic lung inflammation as previously described [17]. Briefly, mice were inoculated intranasally on day 0, 1 and 2 with 25 μg HDM (sensitization phase) and on day 14, 15, 18 and 19 with 6.25 μg HDM (challenge phase). Controls received isotonic sterile saline intranasally on each occasion. Inoculum volume was 20 μl for every HDM and saline exposure and inoculation procedures were performed during isoflurane inhalation anesthesia. The experiment was ended at day 21 by euthanizing the mice and the subsequent collection and processing of samples: in one experiment bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and citrated blood was collected, in a separate experiment one lung was obtained for pathology and one lung for homogenization.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage and Tissue Handling

BALF was harvested after exposing the trachea through a midline incision and instilling and retrieving 1 ml of sterile saline 0.9% (in 500-μl aliquots) [17]. Cell counts were determined for each BALF sample in a hemocytometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, Calif., USA) and differential cell counts by Cytospin preparations stained with Giemsa stain (Diff-Quick; Dade Behring AG, Düdingen, Switzerland). In independent experiments nonlavaged lungs were homogenized in 5 volumes of sterile 0.9% saline using a tissue homogenizer (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla., USA) or fixed in 10% formalin.

Histology

Lungs were embedded in paraffin after fixation in 10% formalin; 4-μm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Parameters of allergic lung inflammation were scored by an experienced histopathologist who was blinded for treatment and strain of mice. The following parameters were scored: interstitial inflammation, peribronchial inflammation, edema, endothelialitis and pleuritis, each graded on a scale of 0-4 (0: absent, 1: mild, 2: moderate, 3: severe, 4: very severe). The total pathology score was expressed as the sum of the score for all parameters. Periodic acid Schiff (PAS)-D staining for carbohydrates in mucus was performed to quantify the amount of mucus. The amount of mucus per lung section was scored by a histopathologist in a semiquantitative fashion on a scale of 0-8 (0-4 for plug formation, 0-4 for mucus extent).

Immunohistochemistry and Digital Image Analysis

Eosinophil staining was performed using a monoclonal antibody against granule major basic protein (GMBP; kindly provided by Dr. Nancy Lee and Prof. James Lee, Mayo Clinic Arizona, Scottsdale, Ariz., USA) [17]. Entire sections were digitized with a slide scanner using the 10× objective (Olympus dotSlide, Tokyo, Japan). Images were exported in the TIFF format for quantification. Influx of eosinophils was determined by measuring the GMBP immunopositive area by digital image analysis (ImageJ 1.46, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Md., USA), and subsequently expressed as a percentage of the total lung area. The average of ten pictures was used for analysis of eosinophilic pulmonary influx.

Assays

Plasma total IgE was measured as described using rat anti-mouse IgE as capture antibody, purified mouse IgE as standard and biotinylated rat-anti-mouse IgE as detection (all reagents from BD Biosciences Pharmingen, Breda, the Netherlands) [17]. Concentrations of lung eotaxin, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 were measured using Elisa (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). Tryptase enzyme activity was determined as described [18] using an amidolytic assay with chromogenic substrate s-2288. Shortly, 10 µl 6-mM chromogenic tryptase substrate S-2288 (Chromogenix Instrumentation Laboratory, Milan, Italy) was added to 70 µl 57-mM Tris-HCl with pH 8.3 in a 96-well microtiter plate. After initiating the reaction by adding 40 µl of BALF sample the ΔA405 nM was developed in 1 h with subtraction of the baseline measurement and monitored in a plate reader at 37°C (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, Vt., USA). Differences were calculated relative to optical density at the zero time point.

Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences between groups were tested by Mann-Whitney U test. GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif., USA) was used for all analyses. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

HDM Airway Exposure Results in Enhanced Tryptase Activity in BALF of Wt Mice

First, we established whether repeated HDM exposure resulted in enhanced mast cell degranulation. For this we measured tryptase activity in BALF at day 21, 2 days after the last challenge (fig. 1) [18, 19]. Tryptase activity was very low in saline-treated mice. HDM treatment increased tryptase activity in Wt mice (p < 0.01 vs. saline controls), but not in Kitw-sh mice (p < 0.05 vs. HDM-treated Wt mice). These data indicate that our HDM asthma model is associated with mast cell activation in the bronchoalveolar compartment.

Fig. 1.

Tryptase activity levels (ΔOD vs. OD at baseline): HDM airway exposure induces tryptase activity in BALF of Wt but not of Kitw-sh mice. Data are means ± SEM of 8 mice per group. ** p < 0.01 versus saline; † p < 0.05 versus HDM-exposed Wt mice. OD = Optical density.

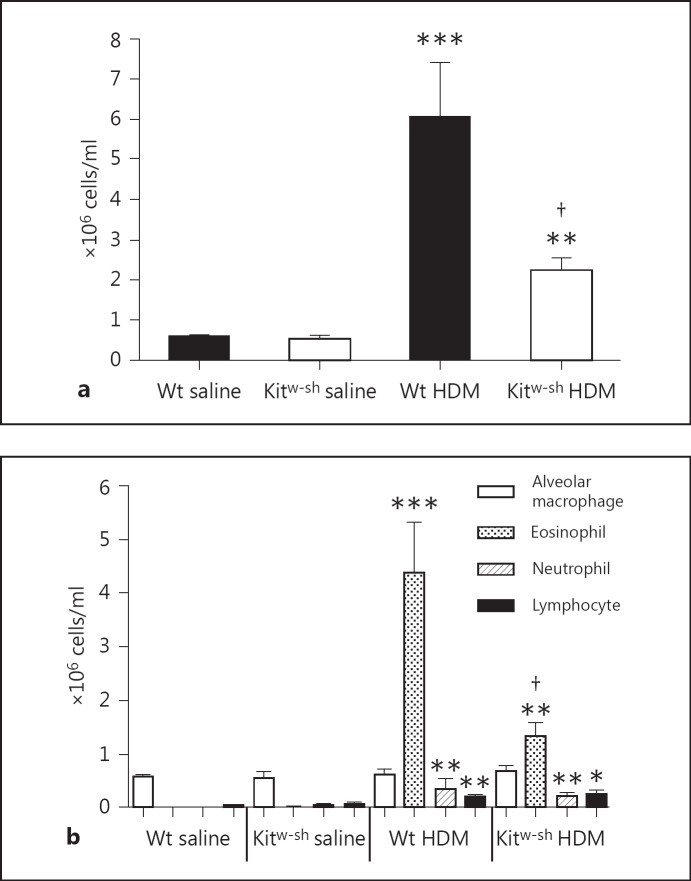

Kitw-sh Mice Have Reduced Influx of Cells in BALF after HDM Exposure due to Decreased Recruitment of Eosinophils

Upon HDM exposure of the airways, both Wt and Kitw-sh mice show increased total cell influx in BALF (fig. 2a; p < 0.001 and p < 0.01 vs. their respective saline controls). Total cell influx in BALF was significantly reduced in Kitw-sh mice after HDM instillation compared to Wt mice (fig. 2a; p < 0.05). The reduction in total cell influx was explained by a decrease in HDM-evoked eosinophil recruitment in Kitw-sh mice compared to Wt mice (fig. 2b; p < 0.05). Relative to saline controls, Wt and Kitw-sh mice showed similar increases in HDM-induced influx of neutrophils (both p < 0.01) and lymphocytes (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively). Together, these data indicate that Kitw-sh mice have decreased cell numbers in BALF in the HDM asthma model caused by a decreased migration of eosinophils to the bronchoalveolar compartment.

Fig. 2.

Kitw-sh mice have decreased total cell counts in BALF after HDM challenge due to lower eosinophil influx: total cell counts (a) and differential cell counts (alveolar macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils and lymphocytes; b). Data are means ± SEM (106 cells/ml) of 8 mice per group. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001 versus saline-challenged mice of the same genotype; † p < 0.05 versus Wt mice challenged with HDM.

Reduced Eosinophil Accumulation in Lung Tissue in Kitw-sh Mice upon HDM Administration

Lung tissue eosinophils were detected by GMBP staining, analyzed by digital imaging and expressed as the percentage of lung surface occupied by eosinophils (fig. 3). HDM instillation caused an increase in pulmonary eosinophils in both Wt and Kitw-sh mice compared to saline (fig. 3a; p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively). The number of eosinophils in lung tissue of Kitw-sh mice was decreased by 74% compared to Wt mice (p < 0.05), corroborating the findings in BALF shown in figure 2 and indicating decreased HDM-induced pulmonary recruitment of eosinophils in Kitw-sh mice.

Fig. 3.

Kitw-sh mice demonstrate a reduced influx of eosinophils in lung tissue after HDM challenge. a Percentage of lung surface stained positive for eosinophils quantified by digital imaging of GMBP staining (see Materials and Methods). Data are means ± SEM of 8 mice per group except for Wt saline (n = 5). * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 versus saline-challenged mice of the same genotype; † p < 0.05 versus Wt mice challenged with HDM. b Representative GMBP staining of lung tissue slides of Wt mice exposed to saline, Kitw-sh mice exposed to saline, Wt mice exposed to HDM and Kitw-sh mice exposed to HDM. Original magnification ×40.

Kitw-sh Mice Develop HDM-Evoked Lung Pathology to a Similar Extent as Wt Mice

HE-stained slides of lung tissue were scored for parameters of allergic lung inflammation in a semiquantitative fashion as described in Materials and Methods (fig. 4). Repeated HDM exposure resulted in lung pathology in both Wt and Kitw-sh mice (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001 vs. their respective saline controls). Surprisingly, there was no difference in the extent of lung pathology between Wt HDM- and Kitw-sh HDM-challenged groups. Moreover, the scores of distinct pathology features (i.e. perivascular inflammation, interstitial inflammation, endothelialitis, peribronchitis and edema) were not different between HDM-exposed groups (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Kitw-sh and Wt mice demonstrate similar lung pathology after HDM challenge. a Semiquantitative pathology scores (described in Materials and Methods). Data are means ± SEM of 8 mice per group except for Wt saline (n = 5). ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001 versus saline-challenged mice of the same genotype. b Representative HE-stained lung tissue slides of Wt mice exposed to saline, Kitw-sh mice exposed to saline, Wt mice exposed to HDM and Kitw-sh mice exposed to HDM. Original magnification ×40.

HDM-Induced Pulmonary Mucus Production Is Similar in Wt and Kitw-sh Mice

Lung tissue slides were PAS-D stained and subsequently scored for mucus production by procedures described in Materials and Methods (fig. 5). HDM challenge led to increased mucus scores in both Wt and Kitw-sh mice compared to saline controls (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively). However, HDM-induced mucus production did not differ between Wt and Kitw-sh mice.

Fig. 5.

Kitw-sh mice show unaltered mucus production in their airways upon HDM challenge. a Semiquantitative mucus scores (described in Materials and Methods). Data are means ± SEM of 8 mice per group except for Wt saline (n = 5). ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001 versus saline-challenged mice of the same genotype. b Representative PAS-D-stained lung tissue slides of Wt mice exposed to saline, Kitw-sh mice exposed to saline, Wt mice exposed to HDM and Kitw-sh mice exposed to HDM. Original magnification ×40.

Lung Levels of Eotaxin Are Reduced in Kitw-sh Mice after HDM Airway Challenge

Since Kitw-sh mice showed a specific defect in eosinophil recruitment to the lung, but not lung pathology or mucus production, upon HDM exposure, we determined whether mast cell deficiency in these mice was associated with reduced pulmonary production of cytokines implicated in eosinophil recruitment: IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 [20] and eotaxin [21]. Lung IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 concentrations were low in all groups and not significantly different between saline- and HDM-challenged mice (data not shown). In contrast, HDM induced a significant increase in lung eotaxin levels in Wt mice, but not in Kitw-sh mice (fig. 6; p < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Lung concentrations of eotaxin: pulmonary eotaxin levels are decreased in Kitw-sh mice after HDM exposure. Data are means ± SEM of 8 mice per group except for Wt saline (n = 5). * p < 0.05 versus saline-challenged Wt mice; † p < 0.05 versus HDM-challenged Wt mice.

Kitw-sh Mice Fail to Produce IgE upon HDM Exposure

Plasma IgE was below detection limit in saline control mice. HDM airway exposure resulted in a strong increase in plasma IgE in Wt, but not in Kitw-sh mice (fig. 7; p < 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Plasma concentrations of IgE: Kitw-sh mice do not show a plasma IgE response after HDM challenge. Data are means ± SEM of 8 mice per group. * p < 0.05 versus saline-challenged mice.

Discussion

Mast cells have been implicated as important players in the pathophysiology of allergic lung inflammation and asthma. Notably, however, the role of mast cells in allergic responses in the airways has been investigated predominantly in Th2-dependent ovalbumin (OVA)-based mouse models [21, 22, 23]. Important differences between OVA and HDM exist. In asthma patients allergy for HDM is highly prevalent [4], while OVA is not a relevant human allergen. Furthermore, whereas HDM can influence mast cell activity, OVA does not [24]. Moreover, relative to OVA-induced lung inflammation, the HDM-based model is characterized by epithelial involvement and mucosal defense, which is likely to be of influence on locally residing mast cells [25, 26]. Taken together, mouse models using HDM as allergen relate better to human asthma, yet are sparsely investigated in mast cell-deficient settings. Here we investigated mast cell-deficient Kitw-sh mice in a recently developed HDM asthma model [17]. We showed that HDM administration via the airways resulted in a local increase in tryptase activity, indicative of mast cell activation. Kitw-sh mice demonstrated decreased eosinophil numbers in BALF and lung tissue after HDM exposure, which was associated with lower eotaxin levels in the bronchoalveolar compartment. Remarkably, lung pathology and mucus production after instillation of HDM were similar in Kitw-sh and Wt mice. Together, these data point to a crucial role of mast cells in HDM-induced recruitment of eosinophils to the lungs, potentially in part via an eotaxin-dependent mechanism. Our results show that mast cells do not contribute to HDM-induced lung pathology or mucus production, suggesting that these responses occur via pathways that do not rely on recruited eosinophils.

The phenotype of the Kitw-sh mice in the current model of HDM-induced lung inflammation was mainly defined by a decreased pulmonary recruitment of eosinophils. This finding is in accordance with previous studies that investigated Kitw-sh mice in allergic lung inflammation elicited by OVA [19, 20, 27]. While the levels of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 remained low in all mice after HDM challenge, pulmonary concentrations of eotaxin, a key chemoattractant for eosinophils [21], were significantly reduced in Kitw-sh mice. The role of mast cells and eotaxin in eosinophil attraction was previously studied in allergen-challenged skin, identifying a role for histamine released from mast cells in inducing eotaxin expression by endothelial cells and subsequently the recruitment of eosinophils [17]. It would be interesting for future research to investigate interactions of mast cells and endothelium in HDM-induced lung inflammation.

Mast cell deficiency had no effect on HDM-evoked lung pathology in our study, which contrasts with data from earlier studies using OVA as allergen showing attenuated pulmonary inflammation in Kitw-sh mice [19, 20, 27]. This illustrates differences between OVA and HDM effects in the airways: while OVA-induced responses are almost completely dependent on mast cells, the heterogeneity of the HDM extract probably induces a broader symphony of allergenic effects that also involve activation of innate immunity [reviewed in [16]], initiating both mast cell-dependent and independent effects [reviewed in [3]]. It is also important to recognize differences in mouse strains in this respect. While BALB/c mice are skewed for Th-2 dependent inflammatory reactions, C57Bl/6 mice (the genetic background of the Kitw-sh mice used here), are more prone to Th1 inflammation [reviewed in [28]]. A potential ‘Th2 bias’ may occur when using BALB/c mice and/or OVA which may result in underestimation of the effect of Th1-dependent inflammatory reactions. The mouse strain used has been shown to be of importance for asthma models in a series of experiments [29], but only in an OVA Th2-dependent model. Importantly, the effects of HDM are not exclusively Th2 dependent: effects of HDM extract includes activating toll-like receptor 2- and 4-dependent pathways [30] and proteolytic activity targeted at airway epithelial tight junctions [26, 31, 32]. Additionally, HDM preparations contain protease-activated receptor agonists, which have diverse proinflammatory effects [33]. This extensive activation of multiple inflammatory pathways involves distinct cellular, epithelial and humoral components besides mast cells and they are hypothetically underestimated in OVA-based protocols. Comparable with the unaffected lung pathology between Wt and Kitw-sh mice, HDM-evoked mucus production was not dependent on mast cells in our C57Bl/6-based HDM model. Lower tryptase activity observed in Kitw-sh mice did not significantly impact lung pathology, indicating that tryptase-independent mechanisms were more important for the outcome of HDM-induced allergic lung inflammation. Of note, it is known that Kitw-sh mice have been described to develop lung pathology resembling emphysema beyond the age of 14 weeks [34]. We used mice at a younger age and lung pathology of saline-challenged Kitw-sh mice was unremarkable and not different from Wt mice.

The levels of total IgE were absent in Kitw-sh mice after HDM challenge compared to Wt mice, indicating as expected that the mast-cell-dependent recruitment of eosinophils is partly IgE dependent. However, since mast cells are essential for the initiation of immunoglobulin production, it could well be that the differences in IgE are due to lack of mast cell-induced sensitization capacities of Kitw-sh mice compared to Wt mice. Strongly attenuated IgE production in response to HDM was previously also shown in mast cell-deficient BALB/c mice; other parameters of allergic lung inflammation were not investigated in this study [35].

In conclusion, we have shown that mast cells play a key role in the recruitment of eosinophils to the lungs after airway exposure to HDM. Unexpectedly, mast cells did not impact on HDM-induced lung pathology or mucus production, contrasting with earlier findings in experimental allergic pulmonary inflammation elicited by OVA and adding important new information on the function of mast cells in the airway response to a clinically relevant human allergen.

Acknowledgements

We thank Marieke ten Brink, Joost Daalhuizen, Monique Jeurissen and Danielle Kruijswijk for excellent laboratory assistance. We thank Onno J. de Boer for assistance with digital analysis of GMBP immunostaining. We are indebted to Dr. Nancy Lee and Prof. James Lee (Mayo Clinic Arizona, Scottsdale, Ariz., USA) for generously providing monoclonal antibody against major basic protein. J. Daan de Boer is supported by the Netherlands Asthma Foundation (project 3.2.08.009).

References

- 1.Braman SS. The global burden of asthma. Chest. 2006;130:4S–12S. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1_suppl.4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy DM, O'Byrne PM. Recent advances in the pathophysiology of asthma. Chest. 2010;137:1417–1426. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregory LG, Lloyd CM. Orchestrating house dust mite-associated allergy in the lung. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:402–411. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson RP, Jr, DiNicolo R, Fernandez-Caldas E, Seleznick MJ, Lockey RF, Good RA. Allergen-specific IgE levels and mite allergen exposure in children with acute asthma first seen in an emergency department and in nonasthmatic control subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:258–263. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)70148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, Gurrin LC, Hill DJ, Hosking CS, Khalafzai RU, Hopper JL, Matheson MC, Abramson MJ, Allen KJ, Dharmage SC. House dust mite sensitization in toddlers predicts current wheeze at age 12 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.038. e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brightling CE, Bradding P, Symon FA, Holgate ST, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Mast-cell infiltration of airway smooth muscle in asthma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1699–1705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wardlaw AJ, Brightling CE, Green R, Woltmann G, Bradding P, Pavord ID. New insights into the relationship between airway inflammation and asthma. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103:201–211. doi: 10.1042/cs1030201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galli SJ, Kalesnikoff J, Grimbaldeston MA, Piliponsky AM, Williams CM, Tsai M. Mast cells as ‘tunable’ effector and immunoregulatory cells: recent advances. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:749–786. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorentz A, Schwengberg S, Sellge G, Manns MP, Bischoff SC. Human intestinal mast cells are capable of producing different cytokine profiles: role of IgE receptor cross-linking and IL-4. J Immunol. 2000;164:43–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalesnikoff J, Galli SJ. New developments in mast cell biology. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1215–1223. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chodaczek G, Bacsi A, Dharajiya N, Sur S, Hazra TK, Boldogh I. Ragweed pollen-mediated IgE-independent release of biogenic amines from mast cells via induction of mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2505–2514. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Boer JD, Majoor CJ, van 't Veer C, Bel EHD, van der Poll T. Asthma and coagulation. Blood. 2012;119:3236–3244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-391532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirshenbaum AS, Goff JP, Kessler SW, Mican JM, Zsebo KM, Metcalfe DD. Effect of IL-3 and stem cell factor on the appearance of human basophils and mast cells from CD34+ pluripotent progenitor cells. J Immunol. 1992;148:772–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimbaldeston MA, Chen CC, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Tam SY, Galli SJ. Mast cell-deficient W-sash c-kit mutant Kit W-sh/W-sh mice as a model for investigating mast cell biology in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:835–848. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62055-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyon MF, Glenister PH. A new allele sash (Wsh) at the W-locus and a spontaneous recessive lethal in mice. Genet Res. 1982;39:315–322. doi: 10.1017/s001667230002098x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacquet A. The role of innate immunity activation in house dust mite allergy. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:604–611. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Boer J, Roelofs JJ, de Vos AF, de Beer R, Schouten M, Hommes TJ, Hoogendijk AJ, de Boer OJ, Stroo I, van der Zee JS, Veer CV, van der Poll T. Lipopolysaccharide inhibits Th2 lung inflammation induced by house dust mite allergens in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48:382–389. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0331OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishizaki M, Tanaka H, Kajiwara D, Toyohara T, Wakahara K, Inagaki N, Nagai H. Nafamostat mesilate, a potent serine protease inhibitor, inhibits airway eosinophilic inflammation and airway epithelial remodeling in a murine model of allergic asthma. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;108:355–363. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08162fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payne V, Kam PC. Mast cell tryptase: a review of its physiology and clinical significance. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:695–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wardlaw AJ. Molecular basis for selective eosinophil trafficking in asthma: a multistep paradigm. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:917–926. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dent G, Hadjicharalambous C, Yoshikawa T, Handy RL, Powell J, Anderson IK, Louis R, Davies DE, Djukanovic R. Contribution of eotaxin-1 to eosinophil chemotactic activity of moderate and severe asthmatic sputum. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1110–1117. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-855OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kung TT, Stelts D, Zurcher JA, Jones H, Umland SP, Kreutner W, Egan RW, Chapman RW. Mast cells modulate allergic pulmonary eosinophilia in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;12:404–409. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.12.4.7695919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reuter S, Dehzad N, Martin H, Heinz A, Castor T, Sudowe S, Reske-Kunz AB, Stassen M, Buhl R, Taube C. Mast cells induce migration of dendritic cells in a murine model of acute allergic airway disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;151:214–222. doi: 10.1159/000242359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrerias A, Torres R, Serra M, Marco A, Roca-Ferrer J, Picado C, de Mora F. Subcutaneous prostaglandin E2 restrains airway mast cell activity in vivo and reduces lung eosinophilia and Th2 cytokine overproduction in house dust mite-sensitive mice. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;149:323–332. doi: 10.1159/000205578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holgate ST. Pathophysiology of asthma: what has our current understanding taught us about new therapeutic approaches? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Post S, Nawijn MC, Hackett TL, Baranowska M, Gras R, van Oosterhout AJ, Heijink IH. The composition of house dust mite is critical for mucosal barrier dysfunction and allergic sensitisation. Thorax. 2012;67:488–495. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu M, Tsai M, Tam SY, Jones C, Zehnder J, Galli SJ. Mast cells can promote the development of multiple features of chronic asthma in mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1633–1641. doi: 10.1172/JCI25702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spellberg B, Edwards JE., Jr Type 1/type 2 immunity in infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:76–102. doi: 10.1086/317537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker M, Reuter S, Friedrich P, Doener F, Michel A, Bopp T, Klein M, Schmitt E, Schild H, Radsak MP, Echtenacher B, Taube C, Stassen M. Genetic variation determines mast cell functions in experimental asthma. J Immunol. 2011;186:7225–7231. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammad H, Chieppa M, Perros F, Willart MA, Germain RN, Lambrecht BN. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wan H, Winton HL, Soeller C, Tovey ER, Gruenert DC, Thompson PJ, Stewart GA, Taylor GW, Garrod DR, Cannell MB, Robinson C. Der p 1 facilitates transepithelial allergen delivery by disruption of tight junctions. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:123–133. doi: 10.1172/JCI5844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan H, Winton HL, Soeller C, Taylor GW, Gruenert DC, Thompson PJ, Cannell MB, Stewart GA, Garrod DR, Robinson C. The transmembrane protein occludin of epithelial tight junctions is a functional target for serine peptidases from faecal pellets of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:279–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho HJ, Lee HJ, Kim SC, Kim K, Kim YS, Kim CH, Lee JG, Yoon JH, Choi JY. Protease-activated receptor 2-dependent fluid secretion from airway submucosal glands by house dust mite extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:529–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindsey JY, Ganguly K, Brass DM, Li Z, Potts EN, Degan S, Chen H, Brockway B, Abraham SN, Berndt A, Stripp BR, Foster WM, Leikauf GD, Schulz H, Hollingsworth JW. C-kit is essential for alveolar maintenance and protection from emphysema-like disease in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1644–1652. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201007-1157OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 35.Coyle AJ, Wagner K, Bertrand C, Tsuyuki S, Bews J, Heusser C. Central role of immunoglobulin (Ig) E in the induction of lung eosinophil infiltration and T helper 2 cell cytokine production: inhibition by a non-anaphylactogenic anti-IgE antibody. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1303–1310. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]