Abstract

Host defence peptides (HDPs) are innate immune effector molecules found in diverse species. HDPs exhibit a wide range of functions ranging from direct antimicrobial properties to immunomodulatory effects. Research in the last decade has demonstrated that HDPs are critical effectors of both innate and adaptive immunity. Various studies have hypothesized that the antimicrobial property of certain HDPs may be largely due to their immunomodulatory functions. Mechanistic studies revealed that the role of HDPs in immunity is very complex and involves various receptors, signalling pathways and transcription factors. This review will focus on the multiple functions of HDPs in immunity and inflammation, with special reference to cathelicidins, e.g. LL-37, certain defensins and novel synthetic innate defence regulator peptides. We also discuss emerging concepts of specific HDPs in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including the potential use of cationic peptides as therapeutics for immune-mediated inflammatory disorders.

Key Words: Inflammation, Host defence peptides, Antimicrobial peptides, Host defence, Immunomodulation

Introduction

Antimicrobial peptides were described more than 25 years ago. The peptides cecropins were isolated from the pupae of the moth Hyalophora cecropia in 1980, followed by the discovery of magainins from the skin of the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) and defensins from mammalian neutrophils [1]. Cationic antimicrobial peptides have been described in a wide variety of species including plants, insects, amphibians and mammals [2]. Research has predominantly been focused on the structures, functions and potential uses of these peptides as ‘alternate’ antibiotic-like therapeutics against infections. Various models are proposed for the microbicidal activities of antimicrobial cationic peptides, which include interaction with the negatively charged membrane components of microbes resulting in pore formation, induction of non-specific membrane permeabilization, binding to intracellular targets and disruption of bacterial biofilms [3,4]. Natural cationic antimicrobial peptides can indeed protect against a wide range of infections, including bacterial, viral and parasitic [5,6,7,8]. However, it is now appreciated that the direct microbicidal activity of certain cationic antimicrobial peptides, e.g. human LL-37 and human β-defensin (hBD)-2, is antagonized in the presence of physiological salt concentrations and in the presence of anionic polysaccharides [6,9]. Moreover, two recent studies have conclusively shown that synthetic cationic peptides (based conceptually on natural antimicrobial cationic peptides) with no direct microbicidal properties can protect against various infections in vivo [10,11]. Consistent with this, various studies, primarily in the last decade, have demonstrated that several cationic antimicrobial peptides have multifunctional roles as immune effector molecules, provide a link between innate and adaptive immunity, contribute to resolution of inflammation, maintain homeostasis and aid in wound healing [reviewed in [1,12,13,14]] (table 1). Thus, it is likely that the antimicrobial functions of cationic peptides are largely due to their role in host immunity [5,6,15]. Therefore, the term host defence peptide (HDP) is currently used for natural cationic peptides, which takes into account their overall biological functions both as antimicrobial and immunomodulatory compounds.

Table 1.

Examples of immunomodulatory functions of HDPs and IDR peptides

| Biological function | Peptide | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Chemotaxis of cell types such as | LL-37, PR-39, HNP-1, | 52 |

| neutrophils, monocytes, DCs, T cells | HNP-2, hBD-1 and | 53 |

| and eosinophils | hBD-2 | 54 |

| 55 | ||

| 56 | ||

| Induction of chemokine expression, | LL-37, hBD-2, hBD-3, | 57 |

| e.g. MIP-1β/CCL4, IL-8/CXCL8, | IDR-1 and IDR-1002 | 58 |

| MCP-1/CCL2 and MIP-3α/CCL20 | 11 | |

| 40 | ||

| 10 | ||

| 59 | ||

| 15 | ||

| 22 | ||

| Regulation of chemokine receptor | LL-37 | 22 |

| expression, e.g. IL-8RB and CXCR4 | ||

| Suppression of neutrophil apoptosis | LL-37 and hBD-3 | 60 |

| 24 | ||

| Induction of anti-inflammatory | LL-37, IDR-1 and | 20 |

| cytokines, e.g. IL-10 and IL-1RA | IDR-1002 | 35 |

| 10 | ||

| 22 | ||

| Suppression of pro-inflammatory | LL-37, IDR-1 and | 20 |

| mediators, e.g. TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, | IDR-1002 | 10 |

| MIP-1α and nitric oxide | 15 | |

| 22 | ||

| Activation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK | LL-37 and hBD-2 | 61 |

| signalling pathways | 40 | |

| 62 | ||

| 63 | ||

| Modification of DC differentiation, | LL-37 and HNP-1-3 | 28 |

| endocytic capacity, phagocytic receptor | 27 | |

| expression and cytokine secretion | 25 | |

| 26 | ||

| Enhancement of phagocytosis | HNP-1-3 | 64 |

| Induction of autophagy | LL-37 | 18 |

| Promotion of wound/vascular healing | LL-37, HNP-1, hBD-2 and | 65 |

| hBD-3 | 66 | |

| Regulation of angiogenesis and | LL-37 and PR-39 | 67 |

| arteriogenesis | 68 | |

| Activation and degranulation of mast | LL-37 and hBD-2-4 | 61 |

| cells | 69 | |

| Regulation of T and B lymphocyte | CRAMP | 29 |

| response | ||

| Adjuvant-like functions | BMAP-28, indolicidin, | 70 |

| bactenecin 2A and | 71 | |

| IDR HH2 | 72 | |

| Protection against immune-mediated | IDR-1002 | 20 |

| inflammation in synovial fibroblasts | ||

| Protection against inflammatory shock | LL-37 | 73 |

| or sepsis in vivo | 22 | |

HDPs are gene encoded and vary in size, sequence and structure. They are typically 12–50 amino acids in length with a net positive charge of +2 to +9 and amphipathic with 40–50% hydrophobic residues [1]. HDPs are expressed both in circulating leukocytes and structural cells such as epithelial cells [16]. The structures of HDPs can be broadly classified as (1) amphipathic α-helix (e.g. cathelicidin LL-37), (2) β-sheet structures with disulphide bonds (e.g. protegrin), (3) extended structures (indolicidin) and (4) loop structures with one disulphide bond (e.g. bactenecin). To date, more than 1,200 HDPs have been described (http://aps.unmc.edu/AP/main.php). Defensins and cathelicidins are the two best characterized groups of HDPs in mammals. These peptides are expressed as larger precursor pre-pro-proteins, the structures of which allow for transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation for tightly controlled expression [16]. The pre-pro-proteins are proteolytically processed by endogenous proteases to generate biologically active mature HDPs. For example, the sole human cathelicidin is expressed as an 18-kDa pre-pro-protein, hCAP18, which is cleaved by a serine protease to form the biologically active 37-amino acid, α-helical, amphipathic peptide LL-37. Depending on the specific HDP and the cell type, the expression of these peptides can be constitutive or inducible, and their expression is typically induced by pathogens or other inflammatory effectors such as cytokines [16,17]. Examples of physiological concentrations and sources of certain HDPs are shown in table 2. Recent studies have also demonstrated that metabolites, such as the active metabolite of vitamin D3, can induce the expression of human cathelicidin LL-37 and hBD-4, which in turn contributes to protection against the intracellular pathogen mycobacteria, possibly by aiding in the process of autophagy [18]. Early research with cationic HDPs was focused on their ‘direct’ antimicrobial activity. Interest in this area was propelled by the potential of developing novel antibiotic-like therapeutics, especially for antibiotic-resistant pathogens. However, research in the last decade has solidified the critical role of HDPs as immune effector molecules for both innate and adaptive immune responses.

Table 2.

Examples of normal physiological concentrations of human HDPs

| HDP | Source | Physiological concentration | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| LL-37 | plasma (circulating levels in healthy controls) | 27.2±4.9 ng/ml | 74 |

| LL-37 | maternal plasma | 1.74 ng/ml | 75 |

| LL-37 | cord blood (from normal delivery) | 1.11 ng/ml | 75 |

| LL-37 | neonatal tracheal aspirate | 1–4 ng/ml | 76 |

| hBD-2 | neonatal tracheal aspirate | 250–750 pg/ml | 3 |

| HNP-1–3 | saliva | 1.3±0.22 (xg/ml | 77 |

| HNP-1–3 | bronchoalveolar fluid | 12.9±15 ng/ml | 78 |

| HNP-1–3 | plasma | 323±173 ng/ml | 78 |

In recent years, small synthetic cationic peptides have been designed based on the widely diverse sequences of HDPs used as templates [19]. These novel synthetic cationic peptides are known as innate defence regulator (IDR) peptides and typically exhibit enhanced immunomodulatory activities. IDR peptides described in recent studies (table 3) are essentially linear derivatives of cathelicidins, were selected based on their ability to stimulate chemokine production in human peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells, were shown to protect against endotoxin and infectious challenge and, in contrast to the natural cathelicidins, exhibit limited cytotoxicities [10,11,20,21]. In this review, we will focus on the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory role of HDPs defined so far, with emphasis on cathelicidins and novel synthetic IDR peptides, and further discuss the therapeutic potential of these peptides in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.

Table 3.

Sequences of immunomodulatory IDR peptides

| IDR peptide | Sequence | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|

| IDR-1 | KSRIVPAIPVSLL-NH2 | 10 |

| IDR-1002 | VQRWLIVWRIRK-NH2 | 11 |

| IDR-1018 | VRLIVAVRIWRR-NH2 | 21 |

| IDR HH-2 | VQLRIRVAVIRA-NH2 | 79 |

Diverse Immunity-Related Biological Effects

Various studies have demonstrated that HDPs and their synthetic derivatives, IDR peptides, have multifaceted roles in immunity (summarized in table 1). A primary function associated with certain HDPs is in the facilitation of chemotaxis of immune cells. HDPs, e.g. human cathelicidin LL-37 and defensins human neutrophil peptide (HNP)-1, HNP-2, hBD-1 and hBD-2, can either directly or indirectly promote recruitment of different immune cells such as neutrophils, monocytes, immature dendritic cells (iDCs), T lymphocytes, eosinophils and neutrophils to the site of infection. Human cathelicidin LL-37, human α-defensins HNP-1 and HNP-2, murine β-defensins and porcine cathelicidin PR-39 are direct chemoattractants for cell types such as iDCs, neutrophils and T lymphocytes (table 1). Moreover, at low to modest physiological concentrations, HDPs such as LL-37, hBD-2 and hBD-3 can promote chemotaxis of immune cells indirectly by inducing the production of chemokines such as MCP-1/CCL2, MIP-1β/CCL4, RANTES/CCL5, MIP-3α/CCL20, Gro-α/CXCL1 and IL-8/CXCL8 from both immune cells and structural cells such as epithelial cells and gingival fibroblasts (table 1). Similarly, synthetic derivatives, i.e. IDR-1 and IDR-1002, can also induce chemokine production [10,11]. Induction of chemokines by IDR peptides appears to be cell type dependent; for example, IDR-1002 can induce the production of chemokines from immune cells such as macrophages but not from stromal synovial fibroblasts [11,20]. In addition, HDPs such as LL-37 can up-regulate the expression of chemokine receptors such as IL-8RB, CXCR4 and CCR2 in macrophages [22]. Human defensins hBD-1 and hBD-2 chemoattract dendritic cells (DCs) and T lymphocytes via the chemokine receptor CCR6, which is preferentially expressed on iDCs and memory T cells [23]. Thus, it can be summarized that a critical innate immune function of certain HDPs and IDR peptides is the promotion of immune cell recruitment to the site of infection, which directly contributes to the clearance of infections. Another innate immune mechanism by which HDPs can protect against bacterial invasion is by prolonging the life span of neutrophils. It has been demonstrated that cathelicidin LL-37 and human defensin hBD-3 suppress neutrophil apoptosis (table 1). LL-37 induces the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein BcL-XL and inhibits caspase-3 activity to suppress neutrophil apoptosis [24]. As neutrophils phagocytose and destroy infectious agents, suppressing apoptosis of neutrophils would aid in host defence mechanisms for resolution of bacterial infections.

Apart from innate immune effector functions, HDPs serve as an important link between the innate and adaptive immune systems. Human HDP LL-37 is a potent modifier of DC differentiation from circulating hematopoietic precursor cells and pre-DCs (monocytes and plasmacytoid cells) and can influence adaptive immunity by interaction with iDCs [25,26]. LL-37 up-regulates the endocytic capacity of iDCs, modifies the expression of phagocytic receptors and enhances the secretion of Th1-inducing cytokines in mature DCs [26]. Similarly, defensins, e.g. human hBD-3 and HNP-1 to −3, can initiate the maturation of DCs, up-regulate the expression of co-stimulatory molecules and activate professional antigen-presenting cells [27,28]. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that effects on DCs mediated by the defensins HNP-1 to −3 are typically observed with low concentrations of defensins that do not have direct antimicrobial activity [28]. This observation also aligns with the recent paradigm that the anti-infective mechanism mediated by some HDPs is largely due to the modulation of host immunity. As iDCs can be activated by innate immune mediators and function as antigen-presenting cells to subsequently activate subsets of T and B lymphocytes for the development of the adaptive immune response, it may be proposed that one of the anti-infective mechanisms of HDPs is to influence the differentiation and subsequent change in DC phenotype to promote a robust adaptive immune response. Apart from influencing antigen-presenting cells for the initiation and polarization of adaptive immunity, certain HDPs were shown to have direct effects on lymphocytes. A recent study has demonstrated that the murine cathelicidin CRAMP can directly alter T and B cell responses and plays a role in regulating adaptive immune responses [29]. Similarly, human defensins HNP-1 to −3 can enhance the proliferation and cytokine responses of CD4+ T lymphoctyes from murine spleen and Peyer's patches [30]. The ability of HDPs to influence adaptive immunity is further supported by studies that show that the HDPs BMAP-28 and indolicidin and IDR peptides such as HH-2 have the potential to enhance production of antigen-specific serum antibodies, thus demonstrating adjuvant-like properties (table 1). HDPs are known to promote several other immune-related functions, which include promotion of wound healing, angiogenesis (capillary growth) and arteriogenesis (growth of pre-existing vessels), induction of mast cell degranulation and release of histamine and prostaglandin D2 (see table 1 for specific examples). Unfortunately, the relationship between the structures of the various HDPs and how this relates to the diverse immunity-related functions mediated by these endogenous peptides is not yet resolved.

Research in the last decade has demonstrated direct effects of cationic peptides on immune cells such as macrophages, DCs and T cells, as well as on structural cells, e.g. epithelial cells. These peptides influence both innate and adaptive immune functions. The paradox associated with HDP-mediated immune functions is that even though these peptides promote innate immune effector mechanisms which include certain ‘classical’ inflammatory responses required for resolution of infections, they also contribute to the resolution of inflammation, thus protecting against the detrimental effect of excessive inflammation (discussed below). Overall, direct effects of HDPs on immune functions contribute to a wide range of biological effects from infection control to wound healing and maintaining homeostasis.

Modulation of Inflammation

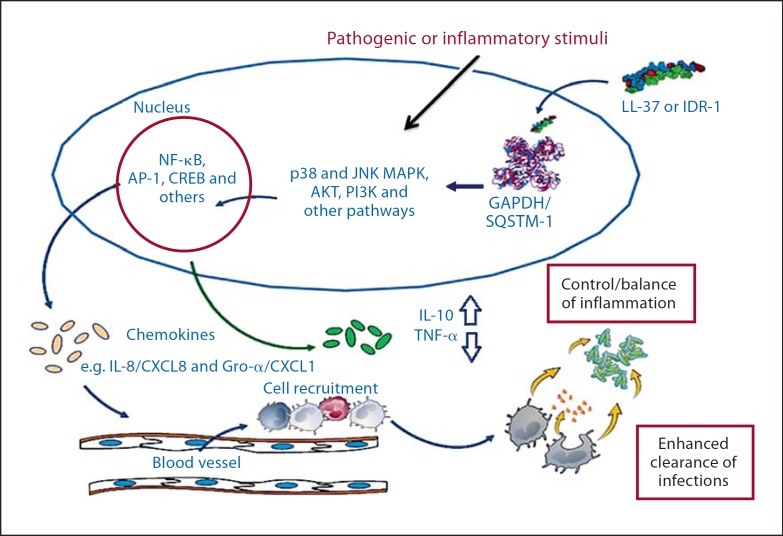

Several in vivo models of infections and sepsis have shown that HDPs such as cathelicidins LL-37 and BMAP-28 and defensin hBD-2, as well as the synthetic IDR peptides IDR-1 and IDR-1002, can modulate host immune responses for the resolution of pathogen-induced inflammation [10,11,31,32,33]. In a recent study, we also demonstrated that IDR-1002 can suppress immune-mediated inflammation under conditions that contribute to tissue destruction in inflammatory arthritis [20]. The anti-inflammatory activity of these cationic peptides appears to be targeted and selective. HDPs such as LL-37 and hBD-3 have been demonstrated to target inflammatory pathways such as Toll-like receptor to NF-ĸB in the presence of exogenous inflammatory stimuli, resulting in selective suppression of pro-inflammatory responses, while maintaining or enhancing critical immune responses such as cell recruitment and movement and crucial anti-inflammatory mechanisms [15,34]. Similar selective anti-inflammatory activity has also been described for the IDR peptides IDR-1 and IDR-1002 [10,11,20]. Cathelicidin peptides such as LL-37, BMAP-28 and mimetics IDR-1 and IDR-1002 have been shown to suppress specific pro-inflammatory responses such as induction of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1β, NF-ĸB1 (p105/p50), TNF-α-induced protein-2, MMP-3 and nitric oxide in the presence of either pathogenic or immune-mediated inflammatory stimuli, without suppressing production of certain chemokines that are required for cell recruitment and movement. In contrast, these peptides enhance or maintain crucial anti-inflammatory responses such as TNF-α-induced protein-3 (also known as A20), the NF-ĸB inhibitor NFĸBIA, expression of IL-10 and the IL-1 antagonist IL-1RA [10,11,15,20,35,36,37]. Mechanistic studies to date have demonstrated that the anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory activity of these peptides is very complex and involves intracellular uptake, endocytic mobilization and interaction with several receptors, resulting in altered signalling pathways (such as NF-ĸB, p38 and JNK MAPK, and PI3K) and transcription factor activities with different kinetics. Intracellular uptake has been shown to be important for the immunomodulatory activity of LL-37 [38], and intracellular uptake was also observed for IDR-1002 [20]. Even though putative cell surface receptors, including Gi-coupled protein receptors, have been described for both LL-37 and IDR-1002 [11,38,39], it is not yet determined whether the intracellular uptake of these peptides is receptor mediated. In addition, intracellular proteins, e.g. GAPDH and sequestosome-1, were demonstrated to be direct interacting protein partners or receptors for the HDP LL-37 and IDR peptide IDR-1, respectively, thus contributing to peptide-mediated immune responses [40,41]. Taken together, it may be speculated that these peptides interact with multiple receptors, with the interactions mediating different events dependent on cell type and perhaps the exogenous stimuli. Peptides such as LL-37 and IDR-1 may be taken up by an atypical endocytic pathway, possibly similar to that described for other cationic cell-penetrating peptides [25,38], followed by interaction with intracellular partners such as GAPDH and sequestosome-1, leading to the alteration of immune signalling mechanisms and resulting in the modulation of inflammatory responses in the presence of exogenous inflammatory stimuli (fig. 1). Specific receptor interaction of HDPs and IDR peptides and how this mediates different immune functions is not yet completely resolved. The targeted and selective anti-inflammatory activity described for specific HDPs (e.g. LL-37 and BMAP-28) and IDR peptides (IDR-1 and IDR-1002) overall results in a net balancing of inflammation and maintains the protective anti-infective responses without excessive harmful inflammation. Therefore, these peptides may prove to be valuable therapeutic agents for controlling the destructive effects of inflammatory diseases without abrogating host defence mechanisms.

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of immunomodulatory activity of LL-37 and IDR-1. Intracellular uptake of LL-37 and IDR-1 is hypothesized to be mediated by an atypical endocytic process. Interaction of these peptides with intracellular receptors such as GAPDH and sequestosome (SQSTM)-1 facilitates alteration of pathogen- or inflammatory mediator-induced signalling pathways, leading to alteration of transcription factor activity with different kinetics. The overall downstream effect is selective control of inflammatory responses and enhanced pathogen clearance. Modified from Mookherjee et al. [35, 40] and Yu et al. [41].

Distribution and Potential Application of HDPs in Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases

Inflammation is an essential element of innate immunity, a breakdown in the regulation of which contributes to progressive tissue and organ damage associated with the pathology of a wide range of chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inflammatory bowel disease and atherosclerosis. The etiology and molecular mechanisms of these diverse chronic inflammatory diseases are poorly understood. Altered expression of various HDPs has been reported in immune-mediated chronic inflammatory diseases (summarized in table 4). Human hBD-2 is suppressed in Crohn's disease and allergic airway inflammation but found to be elevated in psoriasis (table 4). Likewise, cathelicidin LL-37 is suppressed in Crohn's and atopic dermatitis but elevated in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and RA (table 4). A recent study has also demonstrated that patients with SLE develop autoantibodies to LL-37 and proposed that LL-37-self DNA complex is crucial in the chronic activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells central to the pathogenesis of SLE [42]. Aggregates of LL-37 and extracellular self-DNA fragments have been shown to be taken up by plasmacytoid dendritic cells, triggering a robust interferon response [43]. These studies indicate that dysregulation of certain HDPs may be linked to the pathology of chronic inflammatory diseases.

Table 4.

Altered expression of HDPs in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases

| Inflammatory disease | Induction | Suppression | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn's disease | – | hBD-2, hBD-3 and LL-37 | 80 |

| RA and osteoarthritis | LL-37 and hBD-3 | – | 81 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | LL-37 | – | 82 |

| Asthma | – | hBD-2 | 83 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | hBD-1 | – | 84 |

| Bronchiolitis oblit-erans syndrome | hBD-2, HNP-1-3 and LL-37 | – | 85 86 |

| Atopic dermatitis | – | dermcidin and LL-37 |

87 88 |

| Psoriasis | hBD-2 and LL-37 | – | 43 |

| Rosacea | LL-37 | – | 89 |

A common element associated with chronic inflammatory diseases is the dysregulation of the cytokine and chemokine balance. Several critical pro-inflammatory cytokines are elevated in chronic inflammatory diseases such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-15 and IL-23. Therefore, current therapeutic strategies for these diseases include targeting inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α [44]. However, these current therapies often result in an increased risk of infections, including reactivation of tuberculosis, and the potential for development of cancers due to comprehensive immune suppression [45]. Therefore, there is a need to explore alternate therapeutic strategies, ideally a therapy that can suppress the elevated inflammatory responses without neutralizing immune mediators required for the resolution of infections and neoplasms. As discussed above, certain HDPs and IDR peptides can selectively regulate the inflammatory process while maintaining responses required for the resolution of infections. The ability of these peptides to result in a net balancing of inflammation, without compromising host immunity required for resolution of infections, makes them attractive candidates as potential therapeutics for controlling the destructive effects of the inflammatory processes in immune-mediated chronic inflammatory diseases.

Recent studies have demonstrated that some HDPs and IDR peptides can alter immune-mediated cellular responses. For example, human cathelicidin LL-37 differentially alters cytokine-induced responses in blood-derived mononuclear cells, synergistically enhances certain responses induced by IL-1β and GM-CSF [46] and, in contrast, suppresses the interferon-γ-induced cellular response which is critical in Th1-polarized immune responses [47]. The duality of the pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of LL-37 was also demonstrated in psoriasis, which is a Th1-mediated inflammatory autoimmune disease, and it was hypothesized that LL-37-related peptides can act both as regulators and effectors in psoriasis [48]. In addition, a recent study has shown that LL-37 can interfere in the activation of AIM2 inflammasome, IL-1β production and autoimmune inflammation in psoriasis [49]. Based on these studies, it can thus be speculated that these HDPs or their synthetic IDR derivatives may be beneficial for the development of therapeutics for chronic inflammatory diseases, perhaps with a bias toward Th1-polarized chronic inflammatory diseases, which could also be peptide dependent. Consistent with this, the cathelicidin HDP rCRAMP was shown to heal gastric ulcers in an animal model of colitis [50]. Similarly, we have recently demonstrated that a 12-amino-acid cationic IDR peptide, IDR-1002, designed from a bovine cathelicidin, can indeed selectively limit immune-mediated pro-inflammatory responses, under conditions such as those that contribute to tissue destruction in RA [20], which is also largely a Th1-polarized autoimmune inflammatory disease. The IDR-1002 peptide exhibits a targeted and distinct immunomodulatory activity on both immune cells, e.g. macrophages and neutrophils (demonstrated both in vitro and in in vivo studies) [11], and stromal cells, e.g. human fibroblast-like synoviocytes [20]. In addition to the early proof-of-concept studies discussed above, a cationic peptide therapeutic, Omiganan (Migenix Pharmaceuticals), has been demonstrated to be effective against rosacea in phase II clinical trials. Even though investigating the use of HDPs and their synthetic IDR derivatives for controlling the destructive effects of sustained inflammation in chronic inflammatory diseases is in its infancy, these early studies have shown promise and therefore warrant further exploration. However, there are multiple challenges associated with the development of cationic peptide therapeutics. The first involves bioavailability. Cationic peptides are potentially vulnerable to proteases, for example trypsin-like enzymes that have a propensity for basic residues, which is a characteristic feature of cationic HDPs. Several studies have provided solutions to circumvent this problem, such as the use of D-amino acids, chemical modifications of the cationic peptides to make them protease resistant, use of a non-peptide backbone and formulations using liposomes to mask the peptides [51]. Secondly, there is the issue of potential toxicity; however, it appears that small IDR peptides designed from natural HDPs have significantly lower toxicity [10]. There is a lack of pharmacokinetic or toxicology data for cationic peptides, and this is essential for further development of these peptides as therapeutics. The third challenge is the cost of goods, as the cost of manufacturing synthetic peptides is significantly high. Exploring new methods for producing recombinant cationic peptides and designing smaller bioactive IDR peptides may be effective in lowering the cost for cationic peptide therapeutics. Overall, the development of cationic peptide therapeutics is focused on designing small IDR peptides, based conceptually on HDPs, with optimized bioactivity and lower cytotoxicity.

Summary

HDPs are widely distributed natural molecules that play a critical role in anti-infective immunity. Research in the last decade has demonstrated that the biological roles of natural HDPs are very diverse and influence multiple aspects of immunity. It is now well appreciated that the mechanism of the multifaceted role of HDPs in immunity is complex, involving various signalling pathways, and is often determined by physiological conditions, the cellular environment and the extracellular milieu. Specific interacting cellular partners or receptors for various HDPs or IDR peptides, the process of endocytic uptake of the peptides and how this mediates diverse immune functions need to be completely resolved. Moreover, there is limited understanding of the structure and immunomodulatory activity relationship for these peptides. Nevertheless, the paradoxical effect of certain HDPs in enhancing innate immune responses to control infections and at the same time their ability to control inflammation makes these peptides attractive candidates for both anti-infective and anti-inflammatory therapeutics. The multifaceted roles of HDPs and their synthetic mimics, i.e. IDR peptides, have resulted in research into their use as antimicrobials, anti-inflammatory agents and adjuvants and in wound healing. However, there are some challenges in the development of cationic peptide therapeutics, including limited bioavailability, associated toxicity and high manufacturing costs. Overall, cationic HDPs and IDR peptides represent an exciting avenue in immunomodulatory therapeutics, which, although still in its infancy, warrants further exploration.

Disclosure Statement

N.M. is supported by the Health Sciences Centre Foundation (Manitoba, Canada) and the Manitoba Health Research Council for peptide research.

References

- 1.Cederlund A, Gudmundsson GH, Agerberth B. Antimicrobial peptides important in innate immunity. FEBS J. 2011;278:3942–3951. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tossi A, Sandri L. Molecular diversity in gene-encoded, cationic antimicrobial polypeptides. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:743–761. doi: 10.2174/1381612023395475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guani-Guerra E, Santos-Mendoza T, Lugo-Reyes SO, Teran LM. Antimicrobial peptides: general overview and clinical implications in human health and disease. Clin Immunol. 2010;135:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molhoek EM, van Dijk A, Veldhuizen EJ, Haagsman HP, Bikker FJ. A cathelicidin-2-derived peptide effectively impairs Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37:476–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajanbabu V, Chen JY. Antiviral function of tilapia hepcidin 1–5 and its modulation of immune-related gene expressions against infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) in Chinook salmon embryo (CHSE)-214 cells. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011;30:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowdish DM, Davidson DJ, Lau YE, Lee K, Scott MG, Hancock RE. Impact of LL-37 on anti-infective immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:451–459. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0704380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnett E, Lehrer RI, Pratikhya P, Lu W, Seveau S. Defensins enable macrophages to inhibit the intracellular proliferation of Listeria monocytogenes. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:635–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haines LR, Hancock RE, Pearson TW. Cationic antimicrobial peptide killing of African trypanosomes and Sodalis glossinidius, a bacterial symbiont of the insect vector of sleeping sickness. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2003;3:175–186. doi: 10.1089/153036603322662165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bals R, Wang X, Wu Z, Freeman T, Bafna V, Zasloff M, Wilson JM. Human beta-defensin 2 is a salt-sensitive peptide antibiotic expressed in human lung. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:874–880. doi: 10.1172/JCI2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott MG, Dullaghan E, Mookherjee N, Glavas N, Waldbrook M, Thompson A, Wang A, Lee K, Doria S, Hamill P, Yu JJ, Li Y, Donini O, Guarna MM, Finlay BB, North JR, Hancock RE. An anti-infective peptide that selectively modulates the innate immune response. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:465–472. doi: 10.1038/nbt1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nijnik A, Madera L, Ma S, Waldbrook M, Elliott MR, Easton DM, Mayer ML, Mullaly SC, Kindrachuk J, Jenssen H, Hancock RE. Synthetic cationic peptide IDR-1002 provides protection against bacterial infections through chemokine induction and enhanced leukocyte recruitment. J Immunol. 2010;184:2539–2550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bevins CL, Salzman NH. Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:356–368. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallo RL. Sounding the alarm: multiple functions of host defense peptides. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:5–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allaker RP. Host defence peptides – a bridge between the innate and adaptive immune responses. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mookherjee N, Brown KL, Bowdish DM, Doria S, Falsafi R, Hokamp K, Roche FM, Mu R, Doho GH, Pistolic J, Powers JP, Bryan J, Brinkman FS, Hancock RE. Modulation of the TLR-mediated inflammatory response by the endogenous human host defense peptide LL-37. J Immunol. 2006;176:2455–2464. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diamond G, Beckloff N, Weinberg A, Kisich KO. The roles of antimicrobial peptides in innate host defense. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:2377–2392. doi: 10.2174/138161209788682325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosokawa I, Hosokawa Y, Komatsuzawa H, Goncalves RB, Karimbux N, Napimoga MH, Seki M, Ouhara K, Sugai M, Taubman MA, Kawai T. Innate immune peptide LL-37 displays distinct expression pattern from beta-defensins in inflamed gingival tissue. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146:218–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jo EK. Innate immunity to mycobacteria: vitamin D and autophagy. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:1026–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilpert K, Elliott MR, Volkmer-Engert R, Henklein P, Donini O, Zhou Q, Winkler DF, Hancock RE. Sequence requirements and an optimization strategy for short antimicrobial peptides. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1101–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner-Brannen E, Choi KY, Lippert DN, Cortens JP, Hancock RE, El-Gabalawy H, Mookherjee N. Modulation of interleukin-1β-induced inflammatory responses by a synthetic cationic innate defence regulator peptide, IDR-1002, in synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R129. doi: 10.1186/ar3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wieczorek M, Jenssen H, Kindrachuk J, Scott WR, Elliott M, Hilpert K, Cheng JT, Hancock RE, Straus SK. Structural studies of a peptide with immune modulating and direct antimicrobial activity. Chem Biol. 2010;17:970–980. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott MG, Davidson DJ, Gold MR, Bowdish D, Hancock R. The human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 is a multifunctional modulator of innate immune responses. J Immunol. 2002;169:3883–3891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang D, Chertov O, Bykovskaia SN, Chen Q, Buffo MJ, Shogan J, Anderson M, Schroder JM, Wang JM, Howard OM, Oppenheim JJ. Beta-defensins: linking innate and adaptive immunity through dendritic and T cell CCR6. Science. 1999;286:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagaoka I, Tamura H, Hirata M. An antimicrobial cathelicidin peptide, human CAP18/LL-37, suppresses neutrophil apoptosis via the activation of formyl-peptide receptor-like 1 and P2X7. J Immunol. 2006;176:3044–3052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandholtz L, Ekman GJ, Vilhelmsson M, Buentke E, Agerberth B, Scheynius A, Gudmundsson GH. Antimicrobial peptide LL-37 internalized by immature human dendritic cells alters their phenotype. Scand J Immunol. 2006;63:410–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.001752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davidson DJ, Currie AJ, Reid GS, Bowdish DM, MacDonald KL, Ma RC, Hancock RE, Speert DP. The cationic antimicrobial peptide LL-37 modulates dendritic cell differentiation and dendritic cell-induced T cell polarization. J Immunol. 2004;172:1146–1156. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Funderburg N, Lederman MM, Feng Z, Drage MG, Jadlowsky J, Harding CV, Weinberg A, Sieg SF. Human-defensin-3 activates professional antigen-presenting cells via toll-like receptors 1 and 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18631–18635. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.0702130104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez-Garcia M, Oliva H, Climent N, Escribese MM, Garcia F, Moran TM, Gatell JM, Gallart T. Impact of alpha-defensins1– 3 on the maturation and differentiation of human monocyte-derived DCs. Concentration-dependent opposite dual effects. Clin Immunol. 2009;131:374–384. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kin NW, Chen Y, Stefanov EK, Gallo RL, Kearney JF. Cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide differentially regulates T- and B-cell function. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3006–3016. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lillard JW, Jr, Boyaka PN, Chertov O, Oppenheim JJ, McGhee JR. Mechanisms for induction of acquired host immunity by neutrophil peptide defensins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:651–656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cirioni O, Giacometti A, Ghiselli R, Bergnach C, Orlando F, Silvestri C, Mocchegiani F, Licci A, Skerlavaj B, Rocchi M, Saba V, Zanetti M, Scalise G. LL-37 protects rats against lethal sepsis caused by gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1672–1679. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1672-1679.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giacometti A, Cirioni O, Ghiselli R, Bergnach C, Orlando F, D'Amato G, Mocchegiani F, Silvestri C, Del Prete MS, Skerlavaj B, Saba V, Zanetti M, Scalise G. The antimicrobial peptide BMAP-28 reduces lethality in mouse models of staphylococcal sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2485–2490. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000148221.09704.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shu Q, Shi Z, Zhao Z, Chen Z, Yao H, Chen Q, Hoeft A, Stuber F, Fang X. Protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia and sepsis-induced lung injury by overexpression of beta-defensin-2 in rats. Shock. 2006;26:365–371. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000224722.65929.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Semple F, Macpherson H, Webb S, Cox SL, Mallin LJ, Tyrrell C, Grimes GR, Semple CA, Nix MA, Millhauser GL, Dorin JR. Human β-defensin 3 affects the activity of pro-inflammatory pathways associated with MyD88 and TRIF. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3291–3300. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mookherjee N, Hamill P, Gardy J, Blimkie D, Falsafi R, Chikatamarla A, Arenillas DJ, Doria S, Kollmann TR, Hancock RE. Systems biology evaluation of immune responses induced by human host defence peptide LL-37 in mononuclear cells. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5:483–496. doi: 10.1039/b813787k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown KL, Poon GF, Birkenhead D, Pena OM, Falsafi R, Dahlgren C, Karlsson A, Bylund J, Hancock RE, Johnson P. Host defense peptide LL-37 selectively reduces proinflammatory macrophage responses. J Immunol. 2011;186:5497–5505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mookherjee N, Wilson HL, Doria S, Popowych Y, Falsafi R, Yu JJ, Li Y, Veatch S, Roche FM, Brown KL, Brinkman FS, Hokamp K, Potter A, Babiuk LA, Griebel PJ, Hancock RE. Bovine and human cathelicidin cationic host defense peptides similarly suppress transcriptional responses to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1563–1574. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0106048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lau YE, Rozek A, Scott MG, Goosney DL, Davidson DJ, Hancock RE. Interaction and cellular localization of the human host defense peptide LL-37 with lung epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:583–591. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.583-591.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Y, Chen Q, Schmidt AP, Anderson GM, Wang JM, Wooters J, Oppenheim JJ, Chertov O. LL-37, the neutrophil granule- and epithelial cell-derived cathelicidin, utilizes formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) as a receptor to chemoattract human peripheral blood neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1069–1074. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mookherjee N, Lippert DN, Hamill P, Falsafi R, Nijnik A, Kindrachuk J, Pistolic J, Gardy J, Miri P, Naseer M, Foster LJ, Hancock RE. Intracellular receptor for human host defense peptide LL-37 in monocytes. J Immunol. 2009;183:2688–2696. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu HB, Kielczewska A, Rozek A, Takenaka S, Li Y, Thorson L, Hancock RE, Guarna MM, North JR, Foster LJ, Donini O, Finlay BB. Sequestosome-1/p62 is the key intracellular target of innate defense regulator peptide. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:36007–36011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.073627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lande R, Ganguly D, Facchinetti V, Frasca L, Conrad C, Gregorio J, Meller S, Chamilos G, Sebasigari R, Riccieri V, Bassett R, Amuro H, Fukuhara S, Ito T, Liu YJ, Gilliet M. Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self-DNA-peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:73ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilliet M, Lande R. Antimicrobial peptides and self-DNA in autoimmune skin inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feldmann M, Maini RN. Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award. TNF defined as a therapeutic target for rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Nat Med. 2003;9:1245–1250. doi: 10.1038/nm939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Botsios C. Safety of tumour necrosis factor and interleukin-1 blocking agents in rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu J, Mookherjee N, Wee K, Bowdish DM, Pistolic J, Li Y, Rehaume L, Hancock RE. Host defense peptide LL-37, in synergy with inflammatory mediator IL-1beta, augments immune responses by multiple pathways. J Immunol. 2007;179:7684–7691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nijnik A, Pistolic J, Wyatt A, Tam S, Hancock RE. Human cathelicidin peptide LL-37 modulates the effects of IFN-gamma on APCs. J Immunol. 2009;183:5788–5798. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanda N, Ishikawa T, Kamata M, Tada Y, Watanabe S. Increased serum leucine, leucine-37 levels in psoriasis: positive and negative feedback loops of leucine, leucine-37 and pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:1161–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dombrowski Y, Peric M, Koglin S, Kammerbauer C, Goss C, Anz D, Simanski M, Glaser R, Harder J, Hornung V, Gallo RL, Ruzicka T, Besch R, Schauber J. Cytosolic DNA triggers inflammasome activation in keratinocytes in psoriatic lesions. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:82ra38. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang YH, Wu WK, Tai EK, Wong HP, Lam EK, So WH, Shin VY, Cho CH. The cationic host defense peptide rCRAMP promotes gastric ulcer healing in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:547–554. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.102467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hadley EB, Hancock RE. Strategies for the discovery and advancement of novel cationic antimicrobial peptides. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10:1872–1881. doi: 10.2174/156802610793176648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soehnlein O, Zernecke A, Eriksson EE, Rothfuchs AG, Pham CT, Herwald H, Bidzhekov K, Rottenberg ME, Weber C, Lindbom L. Neutrophil secretion products pave the way for inflammatory monocytes. Blood. 2008;112:1461–1471. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tjabringa GS, Ninaber DK, Drijfhout JW, Rabe KF, Hiemstra PS. Human cathelicidin ll-37 is a chemoattractant for eosinophils and neutrophils that acts via formyl-peptide receptors. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;140:103–112. doi: 10.1159/000092305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang D, Chen Q, Chertov O, Oppenheim JJ. Human neutrophil defensins selectively chemoattract naive t and immature dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Territo MC, Ganz T, Selsted ME, Lehrer R. Monocyte-chemotactic activity of defensins from human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:2017–2020. doi: 10.1172/JCI114394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang HJ, Ross CR, Blecha F. Chemoattractant properties of pr-39, a neutrophil antibacterial peptide. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:624–629. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.5.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghosh SK, Gupta S, Jiang B, Weinberg A. Fusobacterium nucleatum and human beta defensins modulate the release of antimicrobial chemokine ccl20/mip-3{alpha} Infect Immun. 2011;79:4578–4587. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05586-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Montreekachon P, Chotjumlong P, Bolscher JG, Nazmi K, Reutrakul V, Krisanaprakornkit S. Involvement of p2x(7) purinergic receptor and mek1/2 in interleukin-8 up-regulation by ll-37 in human gingival fibroblasts. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:327–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bowdish DM, Davidson DJ, Hancock RE. Immunomodulatory properties of defensins and cathelicidins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;306:27–66. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29916-5_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nagaoka I, Niyonsaba F, Tsutsumi-Ishii Y, Tamura H, Hirata M. Evaluation of the effect of human beta-defensins on neutrophil apoptosis. Int Immunol. 2008;20:543–553. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, Hara M, Yokoi H, Tominaga M, Takamori K, Kajiwara N, Saito H, Nagaoka I, Ogawa H, Okumura K. Antimicrobial peptides human beta-defensins and cathelicidin ll-37 induce the secretion of a pruritogenic cytokine il-31 by human mast cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3526–3534. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bowdish DM, Davidson DJ, Speert DP, Hancock RE. The human cationic peptide ll-37 induces activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 kinase pathways in primary human monocytes. J Immunol. 2004;172:3758–3765. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tjabringa GS, Aarbiou J, Ninaber DK, Drijfhout JW, Sorensen OE, Borregaard N, Rabe KF, Hiemstra PS. The antimicrobial peptide ll-37 activates innate immunity at the airway epithelial surface by transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Immunol. 2003;171:6690–6696. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Soehnlein O, Kai-Larsen Y, Frithiof R, Sorensen OE, Kenne E, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Eriksson EE, Herwald H, Agerberth B, Lindbom L. Neutrophil primary granule proteins hbp and hnp1-3 boost bacterial phagocytosis by human and murine macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3491–3502. doi: 10.1172/JCI35740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soehnlein O, Wantha S, Simsekyilmaz S, Doring Y, Megens RT, Mause SF, Drechsler M, Smeets R, Weinandy S, Schreiber F, Gries T, Jockenhoevel S, Moller M, Vijayan S, van Zandvoort MA, Agerberth B, Pham CT, Gallo RL, Hackeng TM, Liehn EA, Zernecke A, Klee D, Weber C. Neutrophil-derived cathelicidin protects from neointimal hyperplasia. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:103ra198. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steinstraesser L, Koehler T, Jacobsen F, Daigeler A, Goertz O, Langer S, Kesting M, Steinau H, Eriksson E, Hirsch T. Host defense peptides in wound healing. Mol Med. 2008;14:528–537. doi: 10.2119/2008-00002.Steinstraesser. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koczulla R, von Degenfeld G, Kupatt C, Krotz F, Zahler S, Gloe T, Issbrucker K, Unterberger P, Zaiou M, Lebherz C, Karl A, Raake P, Pfosser A, Boekstegers P, Welsch U, Hiemstra PS, Vogelmeier C, Gallo RL, Clauss M, Bals R. An angiogenic role for the human peptide antibiotic ll-37/hcap-18. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1665–1672. doi: 10.1172/JCI17545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li J, Post M, Volk R, Gao Y, Li M, Metais C, Sato K, Tsai J, Aird W, Rosenberg RD, Hampton TG, Sellke F, Carmeliet P, Simons M. Pr39, a peptide regulator of angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:49–55. doi: 10.1038/71527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Niyonsaba F, Someya A, Hirata M, Ogawa H, Nagaoka I. Evaluation of the effects of peptide antibiotics human beta-defensins-1/-2 and ll-37 on histamine release and prostaglandin d(2) production from mast cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1066–1075. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1066::aid-immu1066>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van der Merwe J, Prysliak T, Gerdts V, Perez-Casal J. Protein chimeras containing the mycoplasma bovis gapdh protein and bovine host-defence peptides retain the properties of the individual components. Microb Pathog. 2011;50:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cao D, Li H, Jiang Z, Cheng Q, Yang Z, Xu C, Cao G, Zhang L. Cpg oligodeoxynucleotide synergizes innate defense regulator peptide for enhancing the systemic and mucosal immune responses to pseudorabies attenuated virus vaccine in piglets in vivo. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scruten E, Kovacs-Nolan J, Griebel PJ, Latimer L, Kindrachuk J, Potter A, Babiuk LA, Littel-van den Hurk SD, Napper S. Retro-inversion enhances the adjuvant and cpg co-adjuvant activity of host defence peptide bac2a. Vaccine. 2010;28:2945–2956. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Torossian A, Gurschi E, Bals R, Vassiliou T, Wulf HF, Bauhofer A. Effects of the antimicrobial peptide ll-37 and hyperthermic preconditioning in septic rats. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:437–441. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000278906.86815.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jeng L, Yamshchikov AV, Judd SE, Blumberg HM, Martin GS, Ziegler TR, Tangpricha V. Alterations in vitamin d status and anti-microbial peptide levels in patients in the intensive care unit with sepsis. J Transl Med. 2009;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mandic Havelka A, Yektaei-Karin E, Hultenby K, Sorensen OE, Lundahl J, Berggren V, Marchini G. Maternal plasma level of antimicrobial peptide ll37 is a major determinant factor of neonatal plasma ll37 level. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:836–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Starner TD, Agerberth B, Gudmundsson GH, McCray PB., Jr Expression and activity of beta-defensins and ll-37 in the developing human lung. J Immunol. 2005;174:1608–1615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dale BA, Tao R, Kimball JR, Jurevic RJ. Oral antimicrobial peptides and biological control of caries. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6((Suppl 1)):S13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mukae H, Iiboshi H, Nakazato M, Hiratsuka T, Tokojima M, Abe K, Ashitani J, Kadota J, Matsukura S, Kohno S. Raised plasma concentrations of alpha-defensins in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2002;57:623–628. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.7.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kindrachuk J, Jenssen H, Elliott M, Townsend R, Nijnik A, Lee SF, Gerdts V, Babiuk LA, Halperin SA, Hancock RE. A novel vaccine adjuvant comprised of a synthetic innate defence regulator peptide and cpg oligonucleotide links innate and adaptive immunity. Vaccine. 2009;27:4662–4671. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wehkamp J, Schmid M, Stange EF. Defensins and other antimicrobial peptides in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:370–378. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328136c580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Paulsen F, Pufe T, Conradi L, Varoga D, Tsokos M, Papendieck J, Petersen W. Antimicrobial peptides are expressed and produced in healthy and inflamed human synovial membranes. J Pathol. 2002;198:369–377. doi: 10.1002/path.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sun CL, Zhang FZ, Li P, Bi LQ. Ll-37 expression in the skin in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2011;20:904–911. doi: 10.1177/0961203311398515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Beisswenger C, Kandler K, Hess C, Garn H, Felgentreff K, Wegmann M, Renz H, Vogelmeier C, Bals R. Allergic airway inflammation inhibits pulmonary antibacterial host defense. J Immunol. 2006;177:1833–1837. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Andresen E, Gunther G, Bullwinkel J, Lange C, Heine H. Increased expression of beta-defensin 1 (defb1) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Anderson RL, Hiemstra PS, Ward C, Forrest IA, Murphy D, Proud D, Lordan J, Corris PA, Fisher AJ. Antimicrobial peptides in lung transplant recipients with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:670–677. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00110807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ross DJ, Cole AM, Yoshioka D, Park AK, Belperio JA, Laks H, Strieter RM, Lynch JP, Kubak B, Ardehali A, Ganz T. Increased bronchoalveolar lavage human beta-defensin type 2 in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:1222–1224. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000137265.18491.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rieg S, Steffen H, Seeber S, Humeny A, Kalbacher H, Dietz K, Garbe C, Schittek B. Deficiency of dermcidin-derived antimicrobial peptides in sweat of patients with atopic dermatitis correlates with an impaired innate defense of human skin in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174:8003–8010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ong PY, Ohtake T, Brandt C, Strickland I, Boguniewicz M, Ganz T, Gallo RL, Leung DY. Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1151–1160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yamasaki K, Di Nardo A, Bardan A, Murakami M, Ohtake T, Coda A, Dorschner RA, Bonnart C, Descargues P, Hovnanian A, Morhenn VB, Gallo RL. Increased serine protease activity and cathelicidin promotes skin inflammation in rosacea. Nat Med. 2007;13:975–980. doi: 10.1038/nm1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]