ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects and mechanisms of hematopoietic-substrate-1-associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) on liver cancer cells. Information on HAX-1 from liver cancer patients was analyzed by the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) program. Cell migration and invasion abilities were respectively tested by scratch assay and transwell assay. Tube formation assay was applied to detect angiogenesis protein and mRNA was determined using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western blot. We found that the median month survival of HAX-1 overexpressing liver cancer patients was shorter than that of HAX-1 normal liver cancer patients. HAX-1 was overexpressed in liver cancer tissues and cells, and HAX-1 overexpression promoted the liver cancer cells growth, migration, and invasion, whereas silencing HAX-1 produced the opposite results. Inhibition of Akt by LY294002 reversed the migration and invasion abilities of liver cancer cells, and inhibited the ability of cells growth and angiogenesis. Silencing PIK3CA enhanced the inhibitory effects of HAX-1 silencing on the viability, migration, and invasion of liver cancer cells. HAX-1 affected liver cancer cells metastasis and angiogenesis by affecting Akt phosphorylation and FOXO3A expression.

KEYWORDS: Liver cancer, hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1, Akt, FOXO3A, angiogenesis

Introduction

Liver cancer is one of the most common malignancies, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has the fifth and the third highest the incidence and mortality.1 The metastasis and recurrence of liver cancer are direct factors that contribute to the difficulties of treating liver cancer.2,3 Researchers showed that the incidence of HCC was still increasing; however, no effective strategy for treating HCC is available.4

Hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) was first discovered in 1997.5 HAX-1 is highly expressed in tissues such as skeletal muscle and myocardium; however, it is under-expressed in tissues such as the nervous system and kidney.6 Studies showed that HAX-1 was involved in the process of tumor metastasis. HAX-1 is highly expressed in colorectal cancer,7 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma,8 and ovarian carcinoma cell.9 According to previous study, the abnormal regulation of HAX-1 protein played an important role in inhibiting cells’ apoptosis in lymphoma.10 In recent years, study also found that HAX-1 played a critical role in regulating angiogenesis.11

Studying the role of HAX-1 in tumors has attracted much attention. Study showed that HAX-1 could inhibit apoptosis of prostate cancer cells by inactivating caspase-9.12 In colon cancer, overexpression of HAX-1 may lead to poor prognosis in patients with the disease, and that it may act as an important marker of tumor progression and prognosis.7 However, research has hardly been done on HAX-1 in liver cancer. A recent study demonstrated that HAX-1 was elevated in HCC tissue, and that it was associated with clinical prognosis in HCC patients. Thus, HAX-1 could be considered a novel molecular marker for HCC.13

According to the previous researches, we found that HAX-1 was involved in the regulation of cancer cell migration, invasion, and angiogenesis by regulating JAK/STAT3 or Akt. Therefore, this study mainly explores the expression characteristics of HAX-1 in liver cancer and the mechanism that affects the metastasis of liver cancer.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

The HAX-1 expression data of liver cancer patients, which were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) program, included 48 patients with HAX-1 overexpression and 317 patients with normal expression of HAX-1, and the effects of different HAX-1 expression levels on the survival of liver cancer patients were analyzed.

Patients and samples

40 liver cancer tissues and adjacent tissues from 23 males and 17 females (aged 42–73 years old, with an average age of [52.84 ± 3.89] years old) were collected from April 2016 to October 2016. All patients enrolled were diagnosed with liver cancer by pathology and did not have other malignancies. The patients were diagnosed with the disease for the first time and did not receive radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy. The tissues were stored at −80°C for subsequent testing. The HAX-1 mRNA and protein levels in each sample were detected by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), Western blot, and streptavidin-perosidase (SP) staining.

Cells culture and transfection

Human normal liver cells THLE-2 and L02 were purchased from ATCC (USA) or Shanghai Academy (China), respectively. Human liver cancer cells line SK-Hep1, Hep3B, PLC/PRF/5, SNU-182, and SNU-387 were purchased from ATCC. The cells were cultured in DMEM or RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycinin in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cell culture-related reagents were purchased from Gibco (USA).

Plasmid transfection techniques were applied to silence or overexpress HAX-1. siHAX-1 and siPIK3CA were purchased from Oringeng (USA), HAX-1 or PIK3CA coding sequences were subcloned into pcDNA3.1 (Sangon Biotech, China). Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA) was carried out to transfect the cells at a seeding density of 1 × 105 cells/mL for 24 h. Negative-siRNA (Oringeng, USA) or the empty plasmid was used as control.

SP staining

SP staining was performed to detect HAX-1 in tissues. The SP kit was purchased from Bioss (USA). The primary antibody was added and incubated at 4°C for 12 h. Next, the secondary antibody was added and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. 100 μL of DAB was added for 5 min, and the staining was observed under a microscope.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

The CCK-8 assay was applied to test the cell viability and the kit was purchased from Tongren (Japan). The optical density (OD) values at 450 nm were measured (ELX 800, Bio-Teck, USA).

Scratch assay

A black marker pen was used to draw a horizontal line across the hole behind the 6-well plate. 5 × 105cells were added into each well and incubated overnight. The tip of the pipette was used for a vertical scratching and the cells were incubated in serum-free medium (Oringeng, USA) for 24 h. The relative migration distance was calculated.

Transwell assay

Transwell chamber and related reagents were purchased from Corning (USA). 600 μL of the culture medium containing 10% serum was added into the lower chamber, and 100 μL cell suspension (5 × 104 cells) was then added into the upper chamber and cultured for in the incubator for 24 h at 37°C. The invasion rate was calculated after the cells have been stained with Giemsa staining (Shanghai Gefan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China).

Tube formation assay

The cells were digested with trypsin to prepare a cell suspension. BD Matrigel (200 mL, BD Biosciences) was used to coat angiogenic slides. The cells were plated (2 × 104 cells/well) and incubated at 37°C for 6 h. An Olympus IX81 inverted microscope was used to observe the cells and take images.

Western blot

Cells were lysed and the supernatant was collected. BCA assay was performed to determine the protein concentration. SDS-PAGE gel was prepared and applied to electrophoresis. The PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, USA) was transferred by a Trans-Blot Transfer Slot (Bio-Rad, USA) and blocked with 5% fat-free milk for 2 h at room temperature. The primary antibodies (anti-HAX-1, Abcam, ab137613, 32 kD; anti-NICD, Abcam, ab8925, 80 kD; anti-p-Akt [phospho T308], Abcam, ab38449, 56 kD; anti-Akt, Abcam, ab8805, 55 kD; anti-p-STAT3 [phospho Y705], Abcam, ab76315, 88 kD; anti-STAT3, Abcam, ab119352, 88 kD; anti-p-mTOR [phospho S2448], Abcam, ab109268, 289 kD; anti-mTOR, Abcam, ab2732, 289 kD; anti-FOXO3A, Abcam, ab12162, 70 kD; anti-PIK3CA, Abcam, ab40776, 110 kD; anti-GAPDH, Abcam, ab8245, 36 kD) were added according to the instruction, and the samples were shaken twice at room temperature and incubated at 4°C for 12 h. The secondary antibodies (mouse anti-human IgG, Abcam, ab1927, dilution: 1:10000; rabbit anti-human IgG, Abcam, ab6759, dilution: 1:8000; rabbit anti-goat IgG, Abcam, ab6741, dilution: 1:10000; donkey anti-rabbit IgG, R&D, NL004, 1:5000; goat anti-mouse IgG, Abcam, ab6785, 1:8000) were added and incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h. Chemiluminescence detection was carried out using an ECL reagent (Huiying, Shanghai, China).

qRT-PCR

The cells were triturated and lysed, and the RNA was extracted by RNA extraction kit (Promega, Beijing, China). Reverse transcription kit (TaKaRa, Japan) was used to synthesize cDNA under the conditions set at 37°C for 15 min and reverse transcriptase inactivation condition was set at 85°C for 15 s. qRT-PCR was performed using qRT-PCR kit (TaKaRa, Japan) by activating the DNA polymerase at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of two-step PCR (at 95°C for 10 s and at 60°C for 30 s) and a final extension at 75°C for 10 min and held at 4°C. RNase-free water was used as the templates of negative control. All primers were obtained from Genewiz (Suzhou, Jiangsu, China) and listed in Table 1. The formula 2−ΔΔCT was implemented to determine the mRNA expression levels.

Table 1.

The sequences of primers.

| Primer name | Sequence (5ʹ-3ʹ) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| HAX-1-Forward | ACGCCTCGCTCAATTTCTCA | |

| HAX-1-Reverse | AAGCCAAATTCCTCAGGGGG | 188 |

| E-cadherin-Forward | TCCCATCAGCTGCCCAGAAA | |

| E-cadherin-Reverse | ATTGTCCTTGTGTCCTCAGT | 221 |

| PTEN-Forward | GAAGACCATAACCCACCACAGC | |

| PTEN -Reverse | TAGCTGGCAGACCACAAACTGG | 390 |

| Rb1-Forward | CTTCCTCATGCTGTTCAGGAGAC | |

| Rb1-Reverse | GAGGTATTGGTGACAAGGTAGGG | 160 |

| Cyclin D1-Forward | CCTGGATGCTGGAG GTCTG | |

| Cyclin D1-Reverse | GGATGGAGTTGTCGGTG | 108 |

| Vimentin-Forward | AATGGCTCGTCACCTTCG | |

| Vimentin-Reverse | CTAGTTTCAACCGTCTTAATCAG | 192 |

| C-myc-Forward | CGAGTTACTTGGAG | |

| C-myc-Reverse | GGCTGGTGCTGTCTTTGC | 204 |

| AFP-Forward | ACGTCTAGAAGGGATCGGTTGAAT | |

| AFP-Reverse | GATCTCGAGGCCAGAAGCCGCCGCTGT | 144 |

| GAPDH-Forward | CCATCTTCCAGGAGCGAGAT | |

| GAPDH-Reverse | TGCTGATGATCTTGAGGCTG | 180 |

Statistical analysis

All experimental data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS20 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following Turkey’s multiple comparison was carried out to analyze differences among the experimental groups. The statistical significant was expressed as P < 0.05.

Results

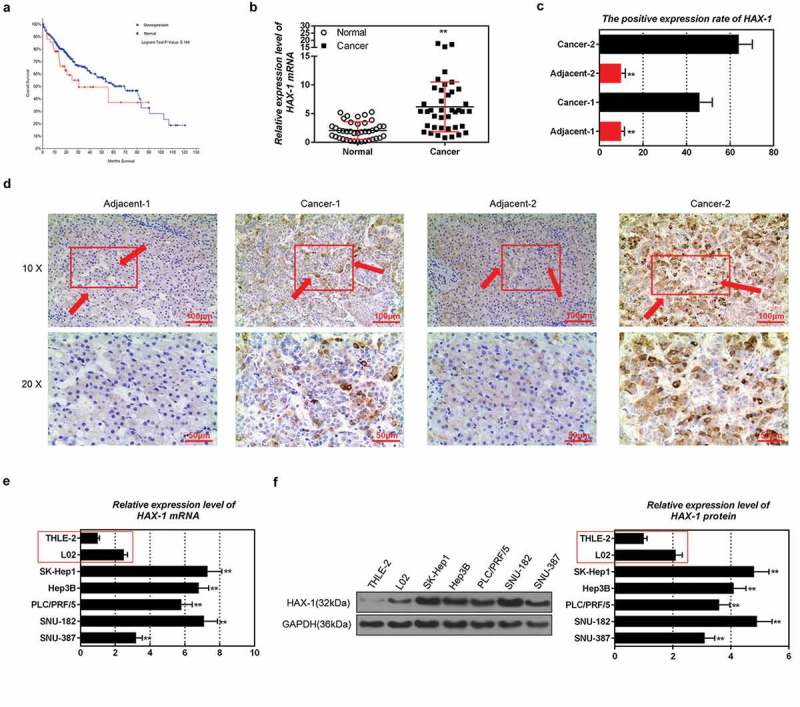

The effects of overexpression and normal expression of HAX-1 on survival of liver cancer patients from TCGA

Information from a total of 48 patients with HAX-1overexpression and 317 patients with normal expression was downloaded from TCGA. The results showed that the median month survival of liver cancer patients with HAX-1 overexpression was 31 months, and that the median month survival of those with normal HAX-1 expression was 69 months (Figure 1(a)). This indicated that patients with high expression of HAX-1 in liver cancer have a poor prognosis.

Figure 1.

Expression characteristics of hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) in liver cancer tissues and cells. (a) Information on HAX-1 from liver cancer patients was analyzed by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) program. (b-d) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), Western blot and streptavidin-perosidase (SP) staining were used to detect HAX-1 levels in liver cancer tissues and adjacent tissues. (e, f) QRT-PCR and Western blot were applied to tested HAX-1 mRNA and protein levels in different liver cancer cells.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus cancer tissues or human normal liver cells THLE-2 and L02.

Expression characteristics of HAX-1 in liver cancer tissues and cells

By detecting clinical liver cancer tissues and adjacent tissues, we found that the levels of HAX-1 mRNA and protein in liver cancer tissues were significantly higher than those in adjacent tissues (Figure 1(b–d)). Western blot and qRT-PCR results also showed that the expression level of HAX-1 in liver cancer cell lines was higher than that in human normal liver cells (Figure 1(e,f)). Moreover, HAX-1 had the highest expression level in SK-Hep1 cells but the lowest expression level in SUN387 cells. Thus, these two cell lines were selected for later experiment.

The effects of silencing or overexpressing HAX-1 on liver cancer cells

SK-Hep1 cells were used to establish HAX-1 low expression liver cell line, whereas SUN387 cells were used to establish HAX-1 overexpression liver cell line. qRT-PCR result showed that HAX-1 decreased sharply in SK-Hep1 cells but increased significantly in SUN387 cells after the transfection (Figure 2(a–h)). Next, we examined the expression levels of proto-oncogene and tumor suppressor genes in liver cancer cells of HAX-1, and the results showed that down-regulation of HAX-1 expression had no significant effects on PTEN or Rb1; however, it inhibited the expression of E-cadherin and promoted the expressions of Cyclin D1, Vimentin, c-myc, and AFP (Figure 2(b–h)). Our results also showed that up-regulation of HAX-1 expression had no significant effects on PTEN and AFP; however, it inhibited the expressions of Cyclin D1, Vimentin and c-myc, and promoted the expressions of E-cadherin and Rb1 (Figure 2(i–o)). This demonstrated that HAX-1 overexpressing promoted the expression of oncogenes but down-regulated the expressions of tumor suppressor genes, while the silencing produced the opposite results.

Figure 2.

The effects of silencing or overexpressing hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) on proto-oncogene and tumor suppressor gene. (a–o) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western blot were used to detect the expressions of proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes at different levels of HAX-1 expressions in SK-Hep1 and SUN387 cells.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus control group and siNC group.

The effects of silencing or overexpressing HAX-1 on cell viability, migration, and invasion

Down-regulation of HAX-1 expression inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion of SK-Hep1 cells (Figure 3(a–e)). However, increasing the expression level of HAX-1 promoted the proliferation, migration, and invasion of SUN387 cells (Figure 4(a–e)), showing that HAX-1 overexpressing promoted the growth and transfer of liver cancer cells, and that the silencing had the opposite results.

Figure 3.

The effects of silencing hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) on SK-Hep1 cells. (a–d) The migration and invasion abilities of SK-Hep1 cells were tested by the scratch assay and Transwell assay. (e) Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was applied to test the effects of HAX-1 low expression on SK-Hep1 cell viability.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus control group and siNC group.

Figure 4.

The effects of overexpressing hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) on SUN387 cells. (a–d) The migration and invasion abilities of SK-Hep1 cells were tested by the scratch assay and Transwell assay. (e) Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was applied to test the effects of HAX-1 low expression on SUN387 cell viability.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus control group and mock group.

The effects of HAX-1 on cellular signaling pathways

To explore the mechanism by which HAX-1 affected the growth, migration, and invasion of liver cancer cells, the effects of silencing and overexpressing HAX-1 on cellular signaling pathways were examined. The results showed that silencing HAX-1 inhibited the expression of NICD protein and phosphorylation levels of mTOR and Akt proteins but promoted the expression of FOXO3A protein (Figure 5(a–f)). We found that up-regulation of HAX-1 expression produced limited effects on NICD levels and mTOR phosphorylation levels; however, it promoted the phosphorylation of Akt protein and inhibited FOXO3A protein expression (Figure 5(g–l)). This suggested that HAX-1 might be involved in the growth, migration, and invasion of liver cancer cells by regulating Akt-associated pathway and FOXO3A protein expression.

Figure 5.

The effects of silencing or overexpressing hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) on signaling pathways. (a–l) Western blot was applied to test JAK/STAT3 and Akt signaling pathways-related protein levels in different liver cancer cells.

Mechanisms of HAX-1 regulating the growth, migration, and invasion of liver cancer cells

FOXO3A is a downstream functional medium of Akt. To further investigate, the involvement of HAX-1 in the growth and metastasis of liver cancer through FOXO3A, LY294002 was used as a PI3K/Akt inhibitor to help analyze the effects of HAX-1 on FOXO3A, and the results showed that the presence of LY294002 could not only further increase the level of FOXO3A overexpression caused by HAX-1 silencing (Figure 6(a)), but also reverse the decrease of FOXO3A levels caused by overexpression of HAX-1 (Figure 6(b)), indicating that HAX-1 could regulate the level of FOXO3A by regulating the phosphorylation of Akt protein, therefore regulating the growth and metastasis of liver cancer cells.

Figure 6.

The effects of silencing or overexpressing hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) and inhibiting Akt on FOXO3A. (a–b) LY294002 was used to inhibit Akt, and the expression level of FOXO3A protein was detected by Western blot. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus siNC group or mock group; #P < .05, ##P < 0.01, versus siHAX-1 group or HAX-1 group; ^P < 0.05, ^^P < 0.01, versus siNC+ LY294002 group.

Further studies have also shown that the inhibition of Akt by LY294002 could not only further aggravate the growth inhibition of liver cancer cells caused by HAX-1 silencing, but also inhibit cell migration and invasion (Figure 7(a–e)). Inhibiting Akt reversed the migration and invasion ability of liver cancer cells and also inhibited the ability of cell growth (Figure 8(a–e)). The results of tube formation assay also showed that the down-regulation of HAX-1 levels inhibited angiogenesis, and that LY294002 aggravated such an inhibitory effect (Figure 9(a,b)). Upregulation of HAX-1 expression levels promoted angiogenesis, whereas the inhibition of Akt reversed the effects of crude angiogenesis by HAX-1 (Figure 9(c,d)).

Figure 7.

The effects of silencing hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) and inhibiting Akt on SK-Hep1cells. (a–d) The migration and invasion abilities of SK-Hep1 cells were tested by the scratch assay and Transwell assay. (e) Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was applied to test the effects of HAX-1 low expression and LY294002 on SK-Hep1 cell viability. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus siNC group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, versus siHAX-1 group; ^P < 0.05, ^^P < 0.01, versus siNC+ LY294002 group.

Figure 8.

The effects of overexpressing hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) and inhibiting Akt on SUN387 cells. (a–d) The migration and invasion abilities of SUN387 cells were tested by the scratch assay and Transwell assay. (e) Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was applied to test the effects of HAX-1 low expression and LY294002 on SUN387 cell viability. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus mock group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, versus HAX-1 group; ^P < 0.05, ^^P < 0.01, versus mock+ LY294002 group.

Figure 9.

The effects of silencing or overexpressing hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) and LY294002 on angiogenesis. (a–d) The tube formation assay was applied to examine the effects of silencing or overexpressing hematopoietic-substrate-1-associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) on angiogenesis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus siNC group or mock group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, versus siHAX-1 group or HAX-1 group; ^P < 0.05, ^^P < 0.01, versus mock+ LY294002 group.

In addition, by silencing PIK3CA, we further explored the mechanism of HAX-1 regulating the growth, migration and invasion of liver cancer cells. The results showed that the silencing of PIK3CA partially reversed the promotive effect of HAX-1 overexpression on the phosphorylation level of Akt protein, however, it further aggravated the inhibitory effect of HAX-1 silencing on the phosphorylation level of Akt protein (Figure 10(a–f)). Furthermore, silencing PIK3CA reduced the promotive effect of HAX-1 overexpression on the viability, migration and invasion of liver cancer cells, and silencing PIK3CA further enhanced the inhibitory effect of HAX-1 silencing on the viability, migration, and invasion of liver cancer cells (Figure 10(g–p)). This suggested that HAX-1 might be involved in the growth, migration, and invasion of liver cancer cells via regulating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.

Figure 10.

The effect of silencing or overexpressing hematopoietic-substrate-1 associated protein X-1 (HAX-1) and PIK3CA on SK-Hep1 and SUN387 cells. (a–f) The effect of silencing PIK3C on the expression of Akt, and the protein levels of PIK3CA, p-Akt and Akt in SUN387 and SK-Hep1 cells were detected by Western blot. (g–h) Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was applied to detect the effects of HAX-1 overexpression or low expression and siPIK3CA on SK-Hep1 and SUN387 cell viability. (i–p) The migration and invasion abilities of SUN387 and SK-Hep1 cells were tested by the scratch assay and Transwell assay. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus mock group or siNC group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, versus HAX-1 group or siHAX-1 group; ^P < 0.05, ^^P < 0.01, versus mock+siPIK3CA group or siNC+ siPIK3CA group.

Discussion

The incidence of HCC is increasing. Though HCC may be related to hepatitis virus infection and alcohol intake, the cause of HCC still remains largely unclear.14 Chemotherapy is a first-line standard treatment program for advanced HCC; however, the observational remission rate is low.15,16 Malignant growth and metastasis of liver cancer cells are the main causes of treatment failure. Thus, studying the mechanism of liver cancer development and metastasis is an important way to discover new treatment methods.

A large number of human genes exist and their effects are highly complex. The development of bioinformatics can analyze tumor cases from multiple regions and improve the efficiency and accuracy of research focusing on genes and cancer.17,18 HAX-1, which is a tumor-associated gene, was shown to up-regulate proto-oncogene expression to promote tumor development; however, its role in liver cancer is still unclear.18 In this study, the survival differences of liver cancer patients with different HAX-1 expression levels were first analyzed by TCGA database. The results showed that liver cancer patients with high HAX-1 level had a shorter survival time. Therefore, HAX-1 was selected as the research target.

The results of this study showed that HAX-1 mRNA and protein were up-regulated in liver cancer tissues and liver cancer cell lines. In addition, HAX-1 overexpression could up-regulate the expressions of proto-oncogenes and inhibit the expressions of tumor suppressor genes; in contrast, the effects of silencing HAX-1 were opposite, suggesting that HAX-1 was involved in the development of liver cancer. To analyze the effects of HAX-1 on liver cancer cells, we established a HAX-1 silencing cell using the SK-Hep1 liver cancer cell line with the highest expression level of HAX-1. SUN387 cells line with a lower HAX-1 expression level was used to establish HAX-1 overexpression cells. The results showed that HAX-1 silencing inhibited the cells growth, migration, and invasion, while HAX-1 overexpression had the opposite effects. Previous studies demonstrated that HAX-1 could promote the proliferation and inhibit apoptosis of cancer cells.19,20 An article published in 2016 in Cell magazine also demonstrated that HAX-1 could affect the formation of slab pseudopods in neuronal cells and thereby regulate cell migration.21 Trebinska’s study suggested that HAX-1 had the ability to promote migration and invasion.22 This suggested that HAX-1 played a role in the promotion of the growth and metastasis of liver cancer cells.

By reviewing previous studies, we found that HAX-1 regulated cell growth and metastasis via JAK/STAT and Akt/mTOR signaling pathways.23,24 In addition, JAK/STAT and Akt/mTOR are ubiquitously expressed, and their activation is also one of the factors causing malignant proliferation and metastasis of liver cancer cells.25–27 The results of this study showed that silencing or overexpression of HAX-1 had no significant effect on the JAK/STAT pathway for SK-Hep1 and SUN387 cells. However, the upregulation of HAX-1 expression levels promoted phosphorylation of Akt protein, while the downregulation of HAX-1 levels inhibited phosphorylation of Akt protein. Further studies also showed that HAX-1 down-regulated FOXO3A protein, which could be reversed by using AKT inhibitor.

To further explore the mechanism by which HAX-1 regulated the growth, migration, and invasion of liver cancer cells, the effects of PI3K/Akt inhibitor LY294002 on silencing or overexpressing HAX-1 liver cancer cells were explored. The results showed that the inhibition of Akt could aggravate the inhibition of liver cancer cells caused by a low expression of HAX-1 and could reverse the promotive effects of 1ow overexpression of HAX on growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Furthermore, silencing PIK3CA enhanced the inhibitory effect of HAX-1 silencing on the viability, migration, and invasion of liver cancer cells. The PI3K/Akt signal pathway is an important regulatory pathway that affects cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.28,29 PIK3CA is the gene coding for the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K, and PIK3CA mutation can lead to enhanced kinase activity and then continuously stimulate downstream AKT to increase the abilities of tumor cell invasion and metastasis.30,31 In addition, a study reported that silencing the PIK3CA gene enhanced the sensitivity of childhood leukemia cells to chemotherapy drugs by inhibiting the phosphorylation of Akt.32 LY294002, which is an inhibitor of PI3K/Akt, can inhibit the PI3K activation by regulating the PI3K/110 and PI3K/85 phosphorylation.33 It has been reported that LY294002, which acts on colon cancer cells and ovarian cancer cells, could specifically inhibit PI3K, reduce the expression of phosphorylated Akt, and then block the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, thereby significantly inhibiting cell growth and inducing apoptosis.34,35 FOXO3A is a functional protein of Akt protein that regulates cell growth and migration.36 Studies have also shown that FOXO3A, as a tumor-suppressor gene, could induce the expressions of pro-apoptotic genes.37,38 Thus, LY294002 may reverse the effects of HAX-1 on cell proliferation and migration by regulating the phosphorylation of relevant subunits (p110 and p85) or the expressions of downstream regulatory proteins (FOXO3A) in PI3K/Akt. In mammals, FOXO3A is involved in the development and progression of tumors by regulating survivin, p27, p21, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).39,40 FOXO3A transcription factors can be used as targets for the treatment of HCC and myeloid leukemia.41 Wang’s study showed that the inhibition of Akt and FOXO3A activities in angiogenesis by vitexin compound 1 could inhibit angiogenesis,42 suggesting that HAX-1 was involved in the growth and metastasis of liver cancer by modulating Akt activation and FOXO3A levels.

In conclusion, HAX-1 was overexpressed in liver cancer tissues and cells, and silencing HAX-1 could inhibit cell growth, migration and invasion, and its mechanism of action was related to the promotion of Akt phosphorylation and the regulation of by HAX-1, which affected cell metastasis and angiogenesis. This suggested that HAX-1 inhibitors might become a new target for the treatment of liver cancer.

Disclosure of Conflict-of-Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bruix J, Sherman M.. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.You A, Cao M, Guo Z, Zuo B, Gao J, Zhou H, Li H, Cui Y, Fang F, Zhang W, et al. Metformin sensitizes sorafenib to inhibit postoperative recurrence and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma in orthotopic mouse models. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:20. doi: 10.1186/s13045-016-0253-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugimachi K, Matsumura T, Hirata H, Uchi R, Ueda M, Ueo H, Shinden Y, Iguchi T, Eguchi H, Shirabe K, et al. Identification of a bona fide microRNA biomarker in serum exosomes that predicts hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:532–538. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruix J, Gores GJ, Mazzaferro V.. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical frontiers and perspectives. Gut. 2014;63:844–855. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki Y, Demoliere C, Kitamura D, Takeshita H, Deuschle U, Watanabe T. HAX-1, a novel intracellular protein, localized on mitochondria, directly associates with HS1, a substrate of Src family tyrosine kinases. J Immunol. 1997;158:2736–2744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam CK, Zhao W, Cai W, Vafiadaki E, Florea SM, Ren X, Liu Y, Robbins N, Zhang Z, Zhou X, et al. Novel role of HAX-1 in ischemic injury protection involvement of heat shock protein 90. Circ Res. 2013;112:79–89. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.279935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei XJ, Li SY, Yu B, Chen G, Du JF, Cai HY. Expression of HAX-1 in human colorectal cancer and its clinical significance. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:1411–1415. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li M, Tang Y, Zang W, Xuan X, Wang N, Ma Y, Wang Y, Dong Z, Zhao G. Analysis of HAX-1 gene expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomathinayagam R, Muralidharan J, Ha JH, Varadarajalu L, Dhanasekaran DN. Hax-1 is required for Rac1-Cortactin interaction and ovarian carcinoma cell migration. Genes Cancer. 2014;5:84–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumann U, Fernandez-Saiz V, Rudelius M, Lemeer S, Rad R, Knorn AM, Slawska J, Engel K, Jeremias I, Li Z, et al. Disruption of the PRKCD-FBXO25-HAX-1 axis attenuates the apoptotic response and drives lymphomagenesis. Nat Med. 2014;20:1401–1409. doi: 10.1038/nm.3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.You B, Cao X, Shao X, Ni H, Shi S, Shan Y, Gu Z, You Y. Clinical and biological significance of HAX-1 overexpression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:12505–12524. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan J, Ma C, Cheng J, Li Z, Liu C. HAX-1 inhibits apoptosis in prostate cancer through the suppression of caspase-9 activation. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:2776–2781. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Huo X, Cao Z, Xu H, Zhu J, Qian L, Fu H, Xu B. HAX-1 is overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes cell proliferation. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:8099–8106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan J-M, Govindarajan S, Arakawa K, Yu MC. Synergism of alcohol, diabetes, and viral hepatitis on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in blacks and whites in the U.S. Cancer. 2004;101:1009–1017. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda M, Shimizu S, Sato T, Morimoto M, Kojima Y, Inaba Y, Hagihara A, Kudo M, Nakamori S, Kaneko S, et al. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with cisplatin versus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: randomized phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:2090–2096. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satapathy SK, Das K, Kocak M, Helmick RA, Eason JD, Nair SP, Vanatta JM. No apparent benefit of preemptive sorafenib therapy in liver transplant recipients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma on explant. Clin Transplant. 2018;32:e13246. doi: 10.1111/ctr.2018.32.issue-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomczak K, Czerwinska P, Wiznerowicz M. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2015;19:A68–77. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.47136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qian L, Bradford AM, Cooke PH, Lyons BA. Grb7 and Hax1 may colocalize partially to mitochondria in EGF-treated SKBR3 cells and their interaction can affect Caspase3 cleavage of Hax1. J Mol Recognit. 2016;29:318–333. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang L, Liu R, Wang Y, Li C, Xi Q, Zhong J, Liu J, Yang S, Wang J, Huang M, et al. The role of Cyclin G1 in cellular proliferation and apoptosis of human epithelial ovarian cancer. J Mol Histol. 2015;46:291–302. doi: 10.1007/s10735-015-9622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Zhang X-F, Fleming MR, Amiri A, El-Hassar L, Surguchev AA, Hyland C, Jenkins DP, Desai R, Brown MR, et al. Kv3.3 channels bind Hax-1 and Arp2/3 to assemble a stable local actin network that regulates channel gating. Cell. 2016;165:434–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trebinska A, Konopinski R, Grzybowska EA. Comment on “HAX1 augments cell proliferation, migration, adhesion, and invasion induced by urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor”. J Oncol. 2013;2013:782327. doi: 10.1155/2013/782327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang M, Meng X-B, Yu Y-L, Sun G-B, Xu X-D, Zhang X-P, Dong X, Ye J-X, Xu H-B, Sun Y-F, et al. Elatoside C protects against hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyocytes through the reduction of endoplasmic reticulum stress partially depending on STAT3 activation. Apoptosis. 2014;19:1727–1735. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-1039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng X, Song L, Zhao W, Wei Y, Guo XB. HAX-1 protects glioblastoma cells from apoptosis through the Akt1 pathway. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:420. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li T, Dong Z-R, Guo Z-Y, Wang C-H, Tang Z-Y, Qu S-F, Chen Z-T, Li X-W, Zhi X-T. Aspirin enhances IFN-α-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma via JAK1/STAT1 pathway. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013;20:366–374. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2013.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J-S, Wang Q, Fu X-H, Huang X-H, Chen X-L, Cao L-Q, Chen L-Z, Tan H-X, Li W, Bi J, et al. Involvement of PI3K/PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway in invasion and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma: association with MMP-9. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:177–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samarin J, Laketa V, Malz M, Roessler S, Stein I, Horwitz E, Singer S, Dimou E, Cigliano A, Bissinger M, et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR-dependent stabilization of oncogenic far-upstream element binding proteins in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2016;63:813–826. doi: 10.1002/hep.28357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imai Y, Yoshimori M, Fukuda K, Yamagishi H, Ueda Y. The PI3K/Akt inhibitor LY294002 reverses BCRP-mediated drug resistance without affecting BCRP translocation. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:1703–1709. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng N, Luo J, Guo X. Silybin suppresses cell proliferation and induces apoptosis of multiple myeloma cells via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:3243–3248. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kidacki M, Lehman HL, Green MV, Warrick JI, Stairs DB. p120-catenin downregulation and PIK3CA mutations cooperate to induce invasion through MMP1 in HNSCC. Mol Cancer Res. 2017;15:1398–1409. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang S, Cai J, Xie W, Luo H, Yang F. miR-202 suppresses prostate cancer growth and metastasis by targeting PIK3CA. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:1499–1504. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang X, Xin X, Qi D, Fu C, Ding M. Silencing the PIK3CA gene enhances the sensitivity of childhood leukemia cells to chemotherapy drugs by suppressing the phosphorylation of Akt. Yonsei Med J. 2019;60:182–190. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Gan Y, Tan Z, Zhou J, Kitazawa R, Jiang X, Tang Y, Yang J. TDRG1 functions in testicular seminoma are dependent on the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:409–420. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S97294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang C, Wang MH, Zhou JD, Chi Q. Upregulation of miR-542-3p inhibits the growth and invasion of human colon cancer cells through PI3K/AKT/survivin signaling. Oncol Rep. 2017;38:3545–3553. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park S, Bazer FW, Lim W, Song G. The O-methylated isoflavone, formononetin, inhibits human ovarian cancer cell proliferation by sub G0/G1 cell phase arrest through PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 inactivation. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:7377–7387. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Das TP, Suman S, Alatassi H, Ankem MK, Damodaran C. Inhibition of AKT promotes FOXO3a-dependent apoptosis in prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2111. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bai M, Zhang M, Long F, Yu N, Zeng A, Zhao R. Circulating microRNA-194 regulates human melanoma cells via PI3K/AKT/FoxO3a and p53/p21 signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:2702–2710. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carbajo-Pescador S, Mauriz JL, Garcia-Palomo A, Gonzalez-Gallego J. FoxO proteins: regulation and molecular targets in liver cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:1231–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kashiwagi A, Fein MJ, Shimada M. Calpain modulates cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (p27(Kip1)) in cells of the osteoblast lineage. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;89:36–42. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9491-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang S, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Maiese K. WISP1 neuroprotection requires FoxO3a post-translational modulation with autoregulatory control of SIRT1. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2013;10:54–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naka K, Hoshii T, Muraguchi T, Tadokoro Y, Ooshio T, Kondo Y, Nakao S, Motoyama N, Hirao A. TGF-beta-FOXO signalling maintains leukaemia-initiating cells in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2010;463:676–680. doi: 10.1038/nature08734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Zheng X, Zeng G, Zhou Y, Yuan H. Purified vitexin compound 1 inhibits growth and angiogenesis through activation of FOXO3a by inactivation of Akt in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:441–448. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]