Abstract

Killing infected or surplus-to-market livestock by free bullet is unavoidable in Foreign Animal Disease response in countries exporting large numbers of live animals. Correct targeting and placement of free bullet projectiles result in immediate death, thereby making this method acceptable for humane animal killing. Regulatory veterinarians will be responsible for animal welfare in overseeing emergency killing of livestock by free bullet. To assure humane fatal penetrating brain injury under field conditions, veterinarians as operational experts, need to fully understand the anatomy of all farmed animals and the pathophysiology of the terminal ballistics of weapon systems to make appropriate, on the ground decisions, in emergency situations.

Résumé

Atteinte de résultats humanitaires lors de l’abattage de bovins par balles de fusil II : Sélection de la cible. L’abattage par balles de fusil de bovins infectés ou en excès pour le marché est inévitable lors de la réponse à l’apparition d’une maladie exotique dans les pays exportant de grandes quantités d’animaux vivants. La mise-enjoue et le placement appropriés de balles de fusil résultent en mort immédiate, rendant ainsi cette méthode acceptable pour l’abattage humanitaire d’animaux. Les vétérinaires d’agences réglementaires seront responsables du bien-être animal en supervisant l’abattage d’urgence par balles des bovins. Afin d’assurer une blessure cérébrale pénétrante fatale dans des conditions de terrain, en tant qu’experts opérationnels, les vétérinaires doivent comprendre à fond l’anatomie de tous les animaux de la ferme et la pathophysiologie de la balistique terminale des armes afin de prendre les décisions appropriées sur le terrain lors de situations d’urgence.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Introduction

Slaughterhouse stunning of animals using a captive bolt (CB) and field humane euthanasia by firearm utilize penetrative brain injury to induce immediate unconsciousness, respiratory arrest (apnea), and death. Scientific literature on penetrating brain injury (PBI) originates largely from human military and civilian case studies (1,2) and from experimental models (3,4). In feral pest animal control by firearm “head-shot” is the goal as it causes immediate loss of sensibility and death. Head-shooting free ranging ruminants for commercial meat or pest control is achievable. Night shooting of kangaroo for commercial meat production has been reported to be able to achieve a 96% head-shot rate (5). In the commercial harvest of free ranging caribou (Rangifer tarandus pearyi) on Southampton Island, Kivalliq Region, Nunavut, Canada, head shot only was confirmed on the majority of harvested carcasses. High-powered rifle and expanding projectile systems were employed and long distance over 100 m shots were taken. Wind speed was identified as a primary cause for weapon system failure presumably because of a combination projectile drift and decreased visibility. Processing was halted in situations of significant wind and blowing snow (D. Will, unpublished data).

In human medicine, ballistic penetrating brain injury (PBI) has a very high case fatality rate. Civilian gunshot wound to the head is commonly self-inflicted, most often utilizes low energy .22 rimfire projectiles, and is most often fatal (6). In a series of 786 patients in the State of Maryland with gunshot wound to the head, 712 (91%) eventually died with 594 dying at the scene; no data on the type of firearm was reported (2). Current medical animal use ethics is in conflict with experiments using live animals and inducing penetrating brain injury (7); ongoing research tends to use models, other knowledge is gained by abattoir and killing for disease control studies.

Biomechanical effect of bullet to the brain

The transference of kinetic energy of projectiles during soft tissue penetration has been extensively investigated. Soft tissue injury is caused by the formation of a permanent cavity due to direct tissue crushing by the projectile and tissue is also stretched by creation of a temporary cavity due to lateral pressure causing tissue expansion away from the moving projectile. The lateral pressure of a missile in the brain encased in an intact cranium can create a temporary cavity of only limited size as brain tissue is forced into regions of less resistance such as the frontal sinus and various foramina of the skull. The cranium has limited ability to stretch, when that limit is exceeded skull bones are torn apart along suture lines (8,9). Gunshot wound to the brain is known to involve the development of high pressures based on volume and speed of back splatter patterns (10) and pressure measurement in simulant and animal models (11–13). In a histological review of 42 cases of fatal handgun penetrating brain injury the mechanism of death was consistent with acute intracranial pressure on the brain stem from the passage of the missile through the brain (14). With very high energy projectiles, massive skull fracture and displacement of the brain (15) has been described in human forensic medicine.

The ballistic behavior of the .22 caliber rimfire system is widely documented. The .22 caliber firearms and ammunition are widely available and frequently used in human assault with firearm (6). The average .22 long rifle (LR) weapon system has sufficient kinetic energy (140 to 200 J) for solid ball projectiles to penetrate the human torso and stop under the elastic skin at the point where a larger caliber firearm would exit and perforate the torso (16). The .22 LR has ample energy to penetrate the human skull and has had military application in WWII and Vietnam primarily in covert assassination by close range PBI (17).

In small abattoir application in Saskatchewan, experienced workers have no difficulty in stunning American bison (Bison bison) cows and young bulls using .22 LR in situations in which the bison are well-restrained in a knocking box. Mature bull bison require the use of a .30 calibre center fire weapon system (.30 M1 carbine) to penetrate the thick hide and skull of this species. Penetration of the calvarium by free bullet or CB (18) is necessary for successful stunning.

Captive bolt pistol physics

Captive bolt (CB) technology (slaughterer’s guns, livestock stunners) started at the beginning of the 20th century with various tools to hold a bolt over the target area of the slaughter animal skull and then a second worker to drive the bolt into the brain with a heavy hammer (19). The modern penetrating bolt is intended to physically penetrate deeply in the calvarium to damage the reticular formation or the ascending reticular activating system, anatomically the thalamus in the anterior brainstem (20). Captive bolts are high mass, slow, 50 m/s, low energy tools to create penetrating brain injury. The penetrating end of the sliding bolt has an outside cutting edge which cuts a circular plug of skin, tissue, and skull and drives that plug some distance, 6 to 9 cm, into the brain tissue without creating secondary missiles of bone chips (21). After skull penetration, much of the remaining energy is converted into stress in the rubber compression washers or internal spring which provide automatic retraction of the bolt from the skull (22). If the bolt effectively penetrates the braincase (sheep model) the animal will be successfully stunned (23). In addition to frequent failure in male adult bison, the short bolt penetration limits effectiveness in livestock with pronounced frontal sinuses such as the Asian water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Free bullet stunning has been tested and specific ammunition recommended for this species (Geco .357 Magnum Hollow Point, 158 gr, 10.2 g, 796 J) (24).

Engineered to deliver 400 J or less (21), the action of the bolt pushing through brain tissue does not create a temporary cavity; however, the permanent cavity is significantly larger than with free bullet as the bolt is typically 10 to 12 mm in diameter, whereas the .22 rimfire is 5.56 mm in diameter (25). It is unlikely that livestock stunned with a CB develop sufficient intracranial pressure to sustain distant axonal injury in the midbrain or the brainstem as do livestock killed with a free bullet (26).

Using live sheep at the time of slaughter, Finnie (27) compared the extent of brain trauma between a commercial CB pistol (Schermer ME, Ettlingen, Germany, no longer in production) and two .22 rimfire projectiles. The CB had a penetration depth of 8 cm (27) and diameter of 12 mm (26). No information was provided on the kinetic energy of the CB. Based on the 1993 brand name of the .22 cartridges tested and current brand names, they may have been “superspeed” (Winchester Super Speed 22LR, Round Nose, 40 gr Lead Core, Copper Plated, 1265 ft/s) 193 J and “subsonic” (.22 Winchester Subsonic 42 Max Rimfire Ammo, Lead, Hollow Point 42 grain, 1065 ft/s) 143 J. In this study which targetted the temporal area of fresh sheep heads the hollow point bullets (low energy) were contained within the cranium while the solid point bullets (high energy) perforated the skull. The 143 J hollow point projectile typically fragmented early in the penetration of the skull accelerating bone fragments into the brain tissue. The bullet material was retained within the skull (7 sheep) or lodged in the subcutaneous tissue on the contralateral side (3 sheep). The experimental animals were not monitored for apnea post injury. On histological examination the projectiles caused distant brain injury consistent with temporary cavity and high pressure shear injury within the cranium, whereas the CB injury was largely limited to the compressed tissue of the permanent cavity (27).

The intracranial pressure effects that mediate the severe brain trauma of ballistic PBT are absent or much diminished in the application of the CB (25). Captive bolt kills by tissue damage alone while penetrating missiles can accelerate secondary bone fragments and distant injury due to the creation of intracranial overpressures.

The physics of ricochet

One example of field testing of firearm systems for emergency slaughter of cattle emphasized the need to ensure that the longitudinal axis of the projectile impacted the frontal bone at an 85° to 90° angle…. to ensure proper targeting of the brain and brainstem and minimize the risk that the projectile ricochets (28). There is no scientific evidence, nor do the principles of Newtonian physics allow for a soft medium such as hair-skin-tissue-bone of the skull to significantly deflect the line of trajectory of common small arms bullets at angles of incidence where a competent shooter would operate.

In 1969, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) published an article in their journal, the “Law Enforcement Bulletin” on how to utilize hard surfaces like concrete and brick walls to indirectly shoot a target. That is to intentionally target a hard surface to ricochet a bullet (.38 Special, rifled 12 ga. slug) and strike a target that is not in the direct line of sight. A 22.5° angle of incidence provided the most predictable bullet bounce. Rifle projectiles travelling in the 1000 m/s range did not result in ricochet in this study as they disintegrated on impact with the hard surface (29).

There is a critical angle of incidence for any hard surface and projectile; above this angle the projectile will penetrate the surface. Slow projectiles (< 300 m/s) can ricochet where high speed projectiles will not. Projectiles lose 10% to 20% of their velocity on hard surface deflection and leave the hard surface at a lower angle than the angle of incidence (30,31). Shotgun slugs (velocity: 370 m/s) and rifle bullets (velocity: 740 m/s) can be made to ricochet from frozen or unfrozen concrete at an incident angle between 5° and 35° (shotgun), 2° to 20° (rifle), all tested ammunition showed remarkably high variations in the ricochet’s angular deviation (32).

Puddles of water have been identified as a ricochet hazard in the urban law enforcement environment. Using 9-mm FMJ (7.4 g, 115 gr, 407 m/s, 617 J) the critical angle of ricochet was 6.5°. At a critical angle of 6.6° the bullet consistently submerged. At angles greater than 4.1° the projectile tumbled upon exit from the water surface. This experiment demonstrated that bullets did not skip off the water but hydroplaned on the surface a distance of up to 62 cm (33).

If ricochet is defined as any measurable deviation in trajectory, then bullets can “ricochet” by tangential wounds to the human skull, more commonly described as a grazing gunshot injury. Grazing or tangential human gunshot injury typically results in a comminuted depressed fracture of the skull at the impact site (34,35) and intracranial hemorrhage (36). A skin-skull-brain model has been developed to better understand the grazing gunshot wound in humans (7,37).

Ricochet, in ballistic terms, bears no resemblance to the billiard table concept of slow-moving objects bouncing off one another. However, in penetrating brain injury there can be ricochet within the skull where energy depleted projectiles are unable to penetrate the internal lamina of the skull and rebound to cause an extended wound tract in the brain parenchyma (6,14,38). Ricochet as a risk of injury to others, in the case of livestock killing with free bullet is minimal and similar to the risk of missing the target, and risk of over-penetration.

Bullet placement

Penetrating the cranial vault is the single most important factor influencing the capacity of a bullet to cause immediate or rapid physiological incapacitation and death. Any projectile penetrating the cranium with residual energy of even a few Joules will cause a hydraulic pressure spike and acute brain dysfunction stunning of the animal. In battlefield triage, any penetrating head wound in a comatose patient combined with flaccid skeletal muscle is recognized as a predictor of imminent death due to midbrain injury (39). Pithing of cattle post-CB stunning physically destroys the brain stem and results in a flaccid carcass which enhances the worker safety when hoisting cattle for bleeding (40). Pithing has been recommended whenever a bovine animal has to be euthanized without exsanguination (41).

Traditional landmarks on the external surfaces of food animals for effective humane stunning are derived from industry experience in large slaughter plants using CB pistol with a limited penetration depth and a nearly immobilized target. The system is designed to have the bolt make perpendicular contact with the front of the animal’s skull. Restraint limits the possible movement of the animal’s head. Brainstem penetration in youthful feeder cattle using this approach is readily achieved (42), but not necessary in an industrial process where the animal will be immediately exsanguinated once stunned.

Guidelines for humane killing with penetrating bolt usually use pictorial graphics that right-angle “target” the front of the skull with the limited bolt reach. The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Euthanasia and Slaughter Guidelines currently suggest the penetrating captive bolt (PCB) be placed perpendicular to the skull at an anatomic site defined as on the intersection of 2 lines each drawn from the lateral canthus of the eyes to the base of the opposite horn. An alternate method for identifying this anatomic site is on the midline of the forehead or skull half-way between 2 lines, one drawn laterally across the poll and the other from lateral canthus to lateral canthus of each eye (43). When the PCB is held perpendicular to the skull for maximum penetration depth, the bolt is directed toward the diencephalon and midbrain. The pons and medulla oblongata are not directly targeted using this external anatomic guidance. In actual application brain stem structures are frequently crushed because slight tilting of the PCB will direct the bolt caudally toward these structures.

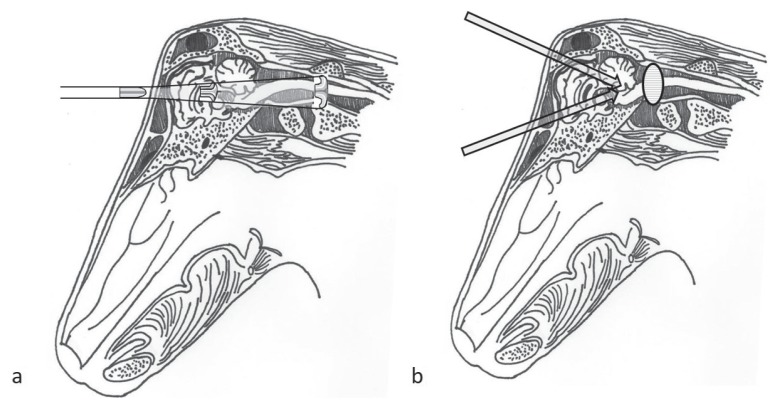

With the use of free bullet, minimizing the risk is over penetration and direct targeting of the pons and medulla oblongata is the objective. Visualizing the deep target from the front of the skull, the deep target is the point where the spinal canal joins the skull, the atlanto-occipital joint. Physical destruction of the midbrain is an additional safety measure in killing by free bullet as the midbrain is in most cases rendered non-functional by the extreme intra-cranial pressure secondary to temporary cavity formation. In any biological system there are exceptional cases in which calvarium penetration by free bullet will not result in immediate incapacitation.

In free-bullet systems, it is often not desirable or possible to achieve a right angle placement of a firearm trajectory with the line of penetration directed to the atlanto-occipital joint. Operators in the field who attempt to humanely kill tall horses using a firearm designed to be operated with 2 hands while standing at ground level in front of an animal, will find they are too short to achieve a right angle shot with the butt of the firearm against the shoulder. In human populations of European descent the average height of males is 178 cm and the average female is 165 cm ± 7 cm (44). A saddle or draft horse standing in an alert position will have skull positioned considerably higher than the shoulder of a person standing on the same elevation. In killing with free bullet midbrain target is available from a wide range of angles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lateral sagittal projection of a generic ruminant skull. a — Perfect shot terminal trajectory with a controlled expanding low energy projectile that comes to rest in the foramen magnum. b — With the energy transfer and penetration limitations of the captive bolt replaced with free missile the target area is significantly larger while retaining the target of the trans-brain penetration with the foramen magnum as the target (shaded oval).

The brainstem in all food animals is located at the floor of the cranial cavity, at the level of the internal acoustic meatus and midway between the bases of the attachment of both ears. To be consistently effective in field situations the operator must target the brainstem by planning each shot to the animal’s head in 3 dimensions. This is accomplished by looking at the animal’s head and ears and visualizing the location of the brainstem within the head. The bullet entry point on the surface of the animal’s head is adjusted as required (dorsally, ventrally, or laterally).

In field situations of free-bullet killing, the options for the bullet entry point on the external surface of the animal’s head can be any point along a semi-circle that starts near one temple and extends across the frontal bone to the opposite temple. The brainstem is the center or axis of this semi-circle. The firearm can be discharged from a position directly in front of the animal, or to the left or right of the medial plane of the animal’s head, as long as the brainstem and midbrain are the primary target within the cranium. The entry point on the exterior surface of the head is not a fixed point on the frontal bone necessary in the use of CB of limited penetrating depth (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Visualizing the line of sight to the mid-brain for free bullet humane killing. Free ranging beef cattle approaching the photographer across a 3-strand barb wire fence. Bos domesticus has small ears and high ear carriage; the lower point of ear-skull attachment is the primary landmark allowing for correct targeting of the brainstem with the angle of incidence of the projectile lower than 90°. Muzzle to target distance 5 to 7 m. Midbrain lies adjacent to the lateral meatus of the ear in all livestock.

Modern low energy pistol (< 800 J) penetrating ballistic wounds to the calvarium

Modern controlled expansion handgun projectiles expand up to twice their original penetrating surface area and do not break up during terminal flight. This class of ammunition is commonly referred to as “Safety” bullets as they do not exit the target, or “Action” bullets as their terminal performance is an active process of bullet deformation and expansion of the cross-sectional crushing surface. Action safety projectiles do not perforate the human or similarly sized soft tissue target. In a study using ballistic gelatin, 2 commonly available 9-mm controlled expanding rounds (Hornady XTP and Speer Gold Dot) achieved full expansion at 5 cm of penetration (45). In a study using the skulls of freshly killed market pigs using FMJ and custom built expanding 9-mm projectiles propelled at equivalent kinetic energy, hollow point, Action-4 and soft-point projectiles did not exit the skull and demonstrated complete conversion of kinetic energy to tissue damage (46).

Clinical experience

One author (DW) has spent over a decade auditing humane slaughter in small provincial abattoirs in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, where stunning of large ruminants with free bullet is common. Although in theory, ballistic penetration of the brain case should result in stun/death, evidence from splitting skulls from free bullet stunning, indicates that consistent effective stunning is assured only by penetration and physical disruption of the brainstem. In split skull examination the further the cranial permanent cavity tract is from the brainstem the greater the chance that it resulted in a poor stun (DM Will, unpublished data).

The preferred skull position targets published in best practices for abattoir CB placement assume the stunner operator is above the animal and the animal isn’t trying to look at the stunner operator (47). When an individual stands in front of animals to kill them with a firearm the unrestrained animals almost always raise their heads to look at the operator, or raise and turn their heads sideways (monocular vision). If you target the recommended point on the skull for CB use, with the animal’s head raised and turned slightly to the side the bullet travels just above and just to one side of the brain stem.

Experienced abattoir workers can effectively kill all domestic cattle breeds in Canada and immature bison and bison cows with a .22 LR carbine when the brainstem is targeted. The point of projectile impact with the skull varies on the front of the head (up, down, left, right) to ensure the bullet travels through the brainstem when it travels to/through the cranial vault.

In fractious animals such as bison, free bullet is safer for the operator as heavy CB stunners cannot be safely placed on the frontal bone. In our experience free bullet at 0.5 to 1 m muzzle-head distance is more accurate than attempts with the various CB stunners.

Discussion

This paper does not address the significant risk of failure associated with human fatigue — both mental and physical. In any emergency or disease control operation requiring free bullet killing, the .22 LR weapon system will be initially considered due to wide availability, general individual operator familiarity, and flexible nature of this weapon system. In a previously reported humane killing of surplus to market piglets using the .22 LR system (48) bolt-action and lever action rifle systems failed due to operator issues such as hand cramping, hand blisters, and deterioration of fine motor skills related to operating the loading actions. Auto loading and pump action (uses major muscle groups only) weapon systems were operated for 5 to 6 h without operator injury or obvious debilitating fatigue.

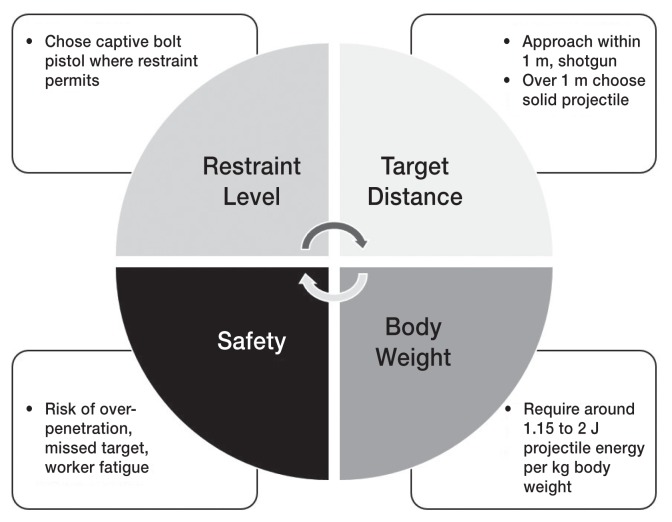

The choice of weapon system to achieve humane killing depends on situation-dependent variables (Figure 3). These are overall operational time pressure (restraint) often time constraints eliminate the option for individual restraint, minimum possible distance achievable between the muzzle of the firearm and the skull of the target, and the size of the animal targeted. Where the target is restrained and the muzzle of a tool can be placed on the skull, then CB is the preferred choice using the smallest effective chemical charge to avoid CB overheating concerns and operator fatigue. Small ruminants can generally be physically restrained to allow CB stunning. When the target can be approached to within 1 m muzzle-skull distance such as breeding pigs, many horses, and most dairy cows, the current system of choice would be the .410 shotgun with lead-free, shot loads. The .410 shotgun at < 1 m distance has sufficient energy to reliably kill any livestock as long as the trajectory includes penetration of the cranium. The .410 has almost no recoil and requires less muscular exertion and less fine motor control than chemically fired CB systems. In situations in which the target cannot be closely approached, more than a 1-meter muzzle-target distance, solid projectiles must be used. With solid projectiles, the rate of failure to stun/kill will increase with increasing distance due to targeting error. Experience using subsonic .30 caliber systems in wildlife management where noise and over penetration are a risk, there is very little margin for error in targeting (49). The choice of system at a distance of 1 to 7 m, indoors or in corals is a rifle chambered for appropriate pistol rounds using controlled expanding bullets carrying 400 to 800 J of energy. Lead-free ammunition, both projectile and accelerant, is preferred under all situations in which animals are humanely killed.

Figure 3.

Considerations in planning or reviewing use of free bullet weapon systems in humane killing of livestock under emergency conditions.

The North America meat complex currently operates as a commercial zone disease free without vaccination for foot and mouth disease, hog cholera, and African swine fever. Periodic failure is an inevitable consequence of complex systems. Any system expected to achieve a livestock humane kill using free bullet is also complex and should be accompanied by an active risk and reliability (50) evaluation system. Weapon systems are in continuous development and new products are frequently commercialized. At the time of a North American meat complex failure similar in scope to the British 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak there may be other specific choices in free bullet weapon systems. The veterinary considerations for any specific recommendation may be informed by the analysis and experience reported in this and sister publication (Can Vet J 2019;60:524–531).

Shooting of animals with free bullet can not guarantee immediate insensibility and death in all animals. All animals should be examined clinically and those showing signs of life should be euthanized before moving the carcass for disposal.

Acknowledgments

No specific funding source is associated with the production of this paper. Dr. Will gratefully acknowledges the many small abattoir and slaughterhouse personnel in Saskatchewan and Manitoba who contributed to his understanding of humane slaughter with free bullets during his career with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. The line drawing in Figure 2 was done freehand by Willyn R. Whiting, referring to plate 17 “bovine heifer calf, sagittal section of the head”, in Popesko P. Atlas of Topographical Anatomy of the Domestic Animals. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: WB Saunders, 1978:30. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Aarabi B. Surgical outcome in 435 patients who sustained missile head wounds during the Iran-Iraq War. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:692–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aarabi B, Tofighi B, Kufera JA, et al. Predictors of outcome in civilian gunshot wounds to the head. J Neurosurg. 2014;120:1138–1146. doi: 10.3171/2014.1.JNS131869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falland-Cheung L, Waddell JN, Chun Li K, Tong D, Brunton P. Investigation of the elastic modulus, tensile and flexural strength of five skull simulant materials for impact testing of a forensic skin/skull/brain model. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2017;68:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Animal models of traumatic brain injury. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:128–142. doi: 10.1038/nrn3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anonomous. A Survey of the Extent of Compliance with the Requirements of the Code of Practice for the Humane Shooting of Kangaroos. Deakin ACT, Australia: RSPCA Australia; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suddaby L, Weir B, Forsyth C. The management of .22 caliber gunshot wounds of the brain: A review of 49 cases. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14:268–272. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100026597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thalia MJ, Kneubuehl BP, Zollinger U, Dirnhofer R. The “skin–skull–brain model:” A new instrument for the study of gunshot effects. Forensic Sci Int. 2002;125:178–189. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(01)00637-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perdekamp MG, Kneubuehl BP, Ishikawa T, et al. Secondary skull fractures in head wounds inflicted by captive bolt guns: Autopsy findings and experimental simulation. Int J Legal Med. 2010;124:605–612. doi: 10.1007/s00414-010-0450-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peschel O, Szeimies U, Vollmar C, Kirchhoff S. Postmortem 3-D reconstruction of skull gunshot injuries. Forensic Sci Int. 2013;233:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazarjan MS, Geoghegan PH, Jermy MC, Taylor M. Experimental investigation of the mechanical properties of brain simulants used for cranial gunshot simulation. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;239:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crockard HA, Brown FD, Johns LM, Mullan S. An experimental cerebral missile injury model in primates. J Neurosurg. 1977;46:776–783. doi: 10.3171/jns.1977.46.6.0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidsson J, Risling M. Characterization of pressure distribution in penetrating traumatic brain injuries. Front Neurol. 2015;6:51–62. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei G, Lu X, Yang X, Tortella F. Intracranial pressure following penetrating ballistic like brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1635–1641. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkpatrick JB, DiMao V. Civilian gunshot wounds of the brain. J Neurosurg. 1978;49:185–198. doi: 10.3171/jns.1978.49.2.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma L, Dagar T. A typical Kronlein shot: A rare case of submental-facio-cranial bullet trajectory with brain exenteration. Forensic Res. 2015;S3:002. doi: 10.4172/2157-7145.1000S3-002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sellier A, Kneubühl B. Wound Ballistic and the Scientific Background. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1994. Wound ballistics of handgun ammunition; pp. 215–278. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulson A. HDMS Silenced .22 Pistols in Vietnam. [Last Accessed 09-10-2018];Small Arms Review. 2002 5:7. Available from: http://www.smallarmsreview.com/display.article.cfm?idarticles=2452. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Can Ç, Bolatkale M, Sarıhan A, Savran Y, Acara AÇ, Bulut M. The effect of brain tomography findings on mortality in sniper shot head injuries. J R Army Med Corps. 2017;163:211–214. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2016-000632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zivotofsky AZ, Strous RD. A perspective on the electrical stunning of animals: Are there lessons to be learned from human electro-convulsive therapy (ECT)? Meat Sci. 2012;90:956–961. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terlouw C, Bourguet C, Deiss V. Consciousness, unconsciousness and death in the context of slaughter. Part I. Neurobiological mechanisms underlying stunning and killing. Meat Sci. 2016;118:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dörfler K, Troeger K, Lücker E, Schönekeß H, Frank M. Determination of impact parameters and efficiency of 6.8/15 caliber captive bolt guns. Int J Legal Med. 2014;128:641–646. doi: 10.1007/s00414-013-0961-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glardon M, Schwenk BK, Riva F, et al. Energy loss and impact of various stunning devices used for the slaughtering of water buffaloes. Meat Sci. 2018;135:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson T, Ridler A, Lamb C, Williams A, Giles S, Gregory N. Preliminary evaluation of the effectiveness of captive-bolt guns as a killing method without exsanguination for horned and unhorned sheep. Anim Welf. 2012;21:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meichtry C, Glauser U, Glardon M, et al. Assessment of a specifically developed bullet casing gun for the stunning of water buffaloes. Meat Sci. 2018;135:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perdekamp MG, Kneubuehl BP, Ishikawa T, et al. Secondary skull fractures in head wounds inflicted by captive bolt guns: autopsy findings and experimental simulation. Int J Legal Med. 2010;124:605–612. doi: 10.1007/s00414-010-0450-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollak S, Saukko P. Humane killing tools. In: Siegel JA, Saukko PJ, Houck MM, editors. Encyclopedia of Forensic Science. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finnie JW. Brain damage caused by a captive bolt pistol. J Comp Pathol. 1993;109:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(08)80250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomson DU, Wileman BW, Rezac DJ, Miesner MD, Johnson-Neitman JL, Biller DS. Computed tomographic evaluation to determine efficacy of euthanasia of yearling feedlot cattle by use of various firearmammunition combinations. Am J Vet Res. 2013;74:1385–1391. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.74.11.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anonomous. Bouncing bullet FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. Washington DC: United States Department of Justice; 1969. pp. 2–4.pp. 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burke T, Rowe W. Bullet ricochet: A comprehensive review. J Forensic Sci. 1992;37:1254–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yong Y-E. A systematic review on ricochet gunshot injuries. Leg Med. 2017;26(Suppl C):45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kunz S, Kirchhoff S, Eggersmann R, et al. Ricocheted rifle and shotgun projectiles: A ballistic evaluation. J Test Eval. 2013;42:277–784. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gold RE, Schecter B. Ricochet dynamics for the nine-millimetre parabellum bullet. J Forensic Sci. 1992;37:90–98. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs GB, Berg RA. Tangential wounds of the head. J Neurosurg. 1970;32:642–646. doi: 10.3171/jns.1970.32.6.0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dodge PR, Meirowsky AM. Tangential wounds of scalp and skull. J Neurosurg. 1952;9:472–483. doi: 10.3171/jns.1952.9.5.0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anglin D, Hutson HR, Luftman J, Qualls S, Moradzadeh D. Intracranial hemorrhage associated with tangential gunshot wounds to the head. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:672–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thali MJ, Kneubuehl BP, Zollinger U, Dirnhofer R. A high-speed study of the dynamic bullet–body interactions produced by grazing gunshots with full metal jacketed and lead projectiles. Forensic Sci Int. 2003;132:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(03)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harcke HT, Levy AD, Getz JM, Robinson SR. MDCT analysis of projectile injury in forensic investigation. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:W106–W111. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brandvold B, Levi L, Feinsod M, George ED. Penetrating craniocerebral injuries in the Israeli involvement in the Lebanese conflict, 1982–1985. Analysis of a less aggressive surgical approach. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:15–21. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.1.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leach TM, Wilkins LJ. Observations on the physiological effects of pithing cattle at slaughter. Meat Sci. 1985;15:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0309-1740(85)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Appelt M, Sperry J. Stunning and killing cattle humanely and reliably. Can Vet J. 2007;48:529–534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oliveira SEO, Gregory NG, Dalla Costa FA, Gibson TJ, Dalla Costa OA, Paranhos da Costa MJR. Effectiveness of pneumatically powered penetrating and non-penetrating captive bolts in stunning cattle. Meat Sci. 2018;140:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilliam J, Shearer J, Woods J, et al. Captive-bolt euthanasia of cattle: Determination of optimal-shot placement and evaluation of the Cash Special Euthanizer Kit® for euthanasia of cattle. Anim Welf. 2012;21:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Visscher PM. Sizing up human height variation. Nat Genet. 2008;40:489–490. doi: 10.1038/ng0508-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bresson F, Ducouret J, Peyre J, et al. Experimental study of the expansion dynamic of 9 mm Parabellum hollow point projectiles in ballistic gelatin. Forensic Sci Int. 2012;219:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von See C, Stuehmer A, Gellrich N-C, Blum KS, Bormann K-H, Rücker M. Wound ballistics of injuries caused by handguns with different types of projectiles. Mil Med. 2009;174:757–761. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-01-4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fries R, Schrohe K, Lotz F, Arndt G. Application of captive bolt to cattle stunning — A survey of stunner placement under practical conditions. Animal. 2012;6:1124–1128. doi: 10.1017/S1751731111002667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whiting TL, Steele GG, Wamnes S, Green C. Evaluation of methods of rapid mass killing of segregated early weaned piglets. Can Vet J. 2011;52:753–758. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caudell JN, Courtney MW, Turnage CT. Initial evidence for the effectiveness of subsonic 308 ammunition for use in wildlife damage management. In: Armstrong JB, Gallagher GR, editors. Proceedings of the 15th Wildlife Damage Management Conference; Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska; 2013. pp. 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 50.French S, Bedford T, Pollard SJ, Soane E. Human reliability analysis: A critique and review for managers. Safety Sci. 2011;49:753–763. [Google Scholar]