Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the leading causes of tumor-related mortalities worldwide. Long noncoding RNAs have been reported to be associated with tumor initiation, progression and prognosis. The present study aimed to explore the association between long noncoding RNA LINC00668 and its co-expression correlated protein-coding genes (PCGs) in HCC. Data of 370 HCC patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas database were used for analysis. LINC00668 and its top 10 PCGs were selected to determine their diagnostic and prognostic value. Molecular mechanisms were explored to identify metabolic processes that LINC00668 and its PCGs are involved in. Prognosis-related clinical factors and PCGs were used to construct a nomogram for predicting prognosis in HCC. A Connectivity Map was constructed to identify candidate target drugs for HCC. The top 10 PCGs identified were: Pyrimidineregic receptor P2Y4 (P2RY4), signal peptidase complex subunit 2 (SPCS2), family with sequence similarity 86 member C1 (FAM86C1), tudor domain containing 5 (TDRD5), ferritin light chain (FTL), stratifin (SFN), nucleolar complex associated 2 homolog (NOC2L), peroxiredoxin 1 (PRDX1), cancer/testis antigen 2 CTAG2 and leucine zipper and CTNNBIP1 domain containing (LZIC). FAM86C1, CTAG2 and SFN had significant diagnostic value for HCC (total area under the curve ≥0.7, P≤0.05); LINC00668, FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL and SFN were of significant prognostic value for HCC (all P≤0.05). Investigation into the molecular mechanism indicated that LINC00668 affects cell division, cell cycle, mitotic nuclear division, and drug metabolism cytochrome P450 (all P≤0.05). The Connectivity Map identified seven candidate target drugs for the treatment of HCC, which were: Indolylheptylamine, mimosine, disopyramide, lidocaine, NU-1025, bumetanide, and DQNLAOWBTJPFKL-PKZXCIMASA-N (all P≤0.05). Our findings indicated that LINC00668 may function as an oncogene and its overexpression indicates poor prognosis of HCC. FAM86C1, CTAG2 and SFN are of diagnostic significance, while FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL and SFN are of prognostic significance for HCC.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, molecular mechanism, long-noncoding RNA, LINC00668, protein-coding gene

Introduction

Liver cancer ranked in the top 10 among estimated new cases of cancer and associated worldwide in 2018, across 20 world regions, with 841,080 (4.7%) new cases and 781,631 (8.2%) mortalities (1). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is not only the predominant histological type of liver cancer, but also accounts for the highest proportion of ~80% of all primary liver cancer incidences (2). In China, HCC is a common type of tumor and is the second leading cause of cancer mortality (3). Approximately 80-90% of all HCC cases are a result of liver cirrhosis, while the second highest percentage is a result of persistent hepatitis B or C virus (HBV) infection (4). Other risk factors for HCC include obesity, iron overload, alcohol abuse, environmental pollutants and aflatoxin contaminations (5,6). Early-stage HCC can be diagnosed and effectively treated through curative resection and liver transplantation, but treatments for advanced HCC are limited and have unsatisfactory outcomes (7,8). HCC tumor recurrence, drug resistance, and disease relapse after therapy are critical issues that result in poor prognosis (8,9).

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), of >200 nucleotides in length, are a subclass of functional noncoding RNAs that are capable affecting protein expression (10,11). These lncRNAs share several characteristics of mRNAs: LncRNAs are 5′capped, equipped with a 3′polyadenylate tail, are made up of a variety of exons and are transcribed by RNA polymerase II (11,12). Previous studies have indicated that lncRNAs play a pivotal role in many biological processes, including cell cycle regulation, cardiac development and X chromosome inactivation (11-14). In addition, lncRNAs are involved in several diseases (15). Microarray technology has identified both upregulated and downregulated lncRNAs in a large number of malignancies, such as breast cancer (16), prostate cancer (17), lung cancer (18) and HCC (19).

LncRNA LINC00668 has been identified to be associated with tumor progression and prognosis: LINC00668, along with LINC00710 and LINC00607, are the three most significantly downregulated lncRNAs in lung adenocarcinoma (20). LINC00668 has been identified as a potentially carcinogenic lncRNA and its knockdown can inhibit the proliferation, invasion and migration abilities of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) cell lines (21). Induced by E2F transcription factor 1, upregulated LINC00668 can predict poor prognosis of gastric cancer (GC) and promote cell proliferation by epigenetically silencing cyclin-dependent protein kinase inhibitors (22). However, the aforementioned studies did not report the tissues specificities of LINC00668 in tumor cells. Databases (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle/page?gene=LINC00668) indicate that tumor cells of these organs expressing LINC00668 highly are meningioma, colorectal, stomach, bile duct and liver. In addition, the association between LINC00668 and HCC remains unclear. Therefore, we conducted an analysis to explore the potential roles of LINC00668 in HCC diagnosis, prognosis and its molecular mechanism.

Materials and methods

Data source and genome-wide co-expression correlated genes

Clinical data and the gene expressions of HCC patients were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; https://cancergenome.nih.gov/). The treatments of these patients underwent can be accessed at https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?host=https%3A%2F%2Ftcga.xenahubs.net&removeHub=https%3A%2F%2Fxena.treehouse.gi.ucsc.edu%3A443. The co-expression correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the correlation between LINC00668 and genome-wide genes, using R 3.5.0 (https://www.r-project.org/). LncRNAs do not encode proteins alone, and their function has been associated with co-expressed protein coding genes (PCGs) (23,24). LINC00668 and its top 10 correlated genes, known as PCGs, were employed for further analysis based on the median levels of expression which served as the cut-off value; they were further divided as low and high expression PCGs.

Expression of LINC00668 and genes in tumor and non-tumor tissue

The expression of LINC00668 and its top 10 PCGs in tumor and non-tumor tissues were obtained from the Metabolic gEne RApid Visualizer (http://merav.wi.mit.edu/) (25). Scatter plots were then created in TCGA database using these data and were visualized using GraphPad 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Diagnostic, prognostic and joint-effect analysis of LINC00668 and its PCGs

The diagnostic value of LINC00668 and its top 10 PCGs were visualized in GraphPad 7.0, using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. An area under curve (AUC) value of <0.7 was considered significant for HCC diagnosis. Then, joint-effect analysis was performed between significant genes and LINC0068.

Thereafter, their prognostic value for overall survival (OS) were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Inc.) and the results were presented using Kaplan-Meier plots visualized using GraphPad 7.0. Joint-effect analysis with LINC00668 was performed on genes that were of prognostic significance for HCC.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp.), which includes Gene Ontology (GO): Biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), molecular function (MF) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) metabolic pathway analyses, was performed to explore the potential molecular mechanisms of LINC00668 and genes that are responsible for the development and progression of HCC. Then, the KEGG set (c2.cp.kegg. v6.1.symbols.gmt) and GO sets (c5.bp.v6.1.symbols.gmt, c5.cc. v6.1.symbols.gmt, c5.mf.v6.1.symbols.gmt) obtained were used for analysis.

Nomogram, co-expression matrix, gene-gene interaction (GGI) and GO interaction network

Prognosis-related genes, LINC00668 and clinical factors were included in the nomogram. The nomogram was constructed and used for 1 year, 3 year, and 5 year OS prediction. Afterwards, the co-expression matrix between top 10 genes and LINC00668 was constructed using R 3.5.0 software. The interaction network between the genes and LINC00668 was presented using the geneMANIA plugin of Cytoscape software (26,27). Moreover, GO terms were visualized using the BinGO plugin of Cytoscape software (28).

Pharmacological targets and drug selection

Genome-wide differentially expressed genes (DEGs), including upregulated and downregulated genes, as well as heatmaps and volcano plots were obtained using edgeR (29). The results with a fold change of >2 and P≤0.05 were used for further analysis. Then, target drugs were selected from the Connectivity Map (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/cmap/). The chemical composition of these drugs were acquired from PubChem Compound (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pccompound/). GO terms were visualized based on the DEGs using BinGO. Then, enrichment analysis was performed based on the DEGs using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery v6.8 (DAVID; https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) (30,31).

Statistical analysis

Survival analyses was performed using SPSS 16.0 software. Median survival time, log-rank P-values, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazards regression models. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Co-expression of correlated genome-wide genes and clinicopathological characteristics of HCC patients

Co-expression of correlated genome-wide genes with LINC00668 were calculated and are shown in Table SI. The top 10 PCGs of LINC00668 were pyrimidineregic receptor P2Y4 (P2RY4), signal peptidase complex subunit 2 (SPCS2), family with sequence similarity 86 member C1 (FAM86C1), tudor domain containing 5 (TDRD5), ferritin light chain (FTL), stratifin (SFN), nucleolar complex associated 2 homolog (NOC2L), peroxiredoxin 1 (PRDX1), cancer/testis antigen 2 (CTAG2) and leucine zipper and CTNNBIP1 domain containing (LZIC) (Table I). Then, LINC00668 and the top 10 PCGs were further explored for their diagnostic, prognostic significance, along with their molecular mechanisms in HCC. A total of 370 HCC patients were enrolled in the analysis. HBV status, tumor stage and radical resection status were found to be associated with OS (log-rank P<0.0001, P<0.0001, P 0.007, respectively; Table II).

Table I.

Top 10 PCGs associated with LINC00668.

| LncRNA | PCG | Coefficient | P-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LINC00668 | P2RY4 | 0.46 | 1.30E-20 | 0.37-0.54 |

| LINC00668 | SPCS2 | 0.4 | 6.54E-16 | 0.31-0.49 |

| LINC00668 | FAM86C1 | 0.39 | 1.20E-14 | 0.30-0.47 |

| LINC00668 | TDRD5 | 0.38 | 1.98E-14 | 0.29-0.47 |

| LINC00668 | FTL | 0.38 | 3.16E-14 | 0.29-0.46 |

| LINC00668 | SFN | 0.37 | 9.85E-14 | 0.28-0.46 |

| LINC00668 | NOC2L | 0.37 | 3.84E-13 | 0.27-0.45 |

| LINC00668 | PRDX1 | 0.36 | 1.01E-12 | 0.27-0.45 |

| LINC00668 | CTAG2 | 0.36 | 1.46E-12 | 0.26-0.44 |

| LINC00668 | LZIC | 0.36 | 1.54E-12 | 0.26-0.44 |

PCG, protein-coding gene; CI, confidence interval; CTAG2, cancer/testis antigen 2; FAM86C1, family with sequence similarity 86 member C1; FTL, ferritin light chain; LZIC, leucine zipper and CTNNBIP1 domain containing; NOC2L, nucleolar complex associated 2 homolog; P2RY4, pyrimidineregic receptor P2Y4; PRDX1, peroxiredoxin 1; SFN, stratifin; SPCS2, signal peptidase complex subunit 2; TDRD5, tudor domain containing 5.

Table II.

Demographic characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in The Cancer Genome Atlas database.

| Variables | Patients (n=370) | Overall survival

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of event | MST (days) | HR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Gender | 0.262 | ||||

| Female | 121 | 51 | 1,490 | Ref. | |

| Male | 249 | 79 | 2,486 | 0.817 (0.573-1.164) | |

| Age (years) | 0.217 | ||||

| ≤60 | 177 | 55 | 2,532 | Ref. | |

| >60 | 193 | 75 | 1,622 | 1.246 (0.879-1.766) | |

| Child-pugha | 0.184 | ||||

| A | 216 | 59 | 2,542 | Ref. | |

| B + C | 22 | 9 | 1,005 | 1.614 (0.796-3.270) | |

| HBV infectionb | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 247 | 104 | 1,210 | Ref. | |

| Yes | 104 | 20 | NA | 0.357 (0.221-0.578) | |

| HCV infectionc | 0.730 | ||||

| No | 295 | 105 | 1,791 | Ref. | |

| Yes | 56 | 19 | 1,229 | 1.090 (0.667-1.782) | |

| Histologic graded | 0.750 | ||||

| G1 | 55 | 18 | 2,116 | Ref. | |

| G2 | 177 | 60 | 1,685 | 1.181 (0.697-2.000) | 0.537 |

| G3 | 121 | 43 | 1,622 | 1.233 (0.711-2.140) | 0.456 |

| G4 | 12 | 5 | NA | 1.693 (0.626-4.584) | 0.300 |

| Tumor stagee | <0.001 | ||||

| I | 171 | 42 | 2,532 | Ref. | |

| II | 85 | 26 | 1,852 | 1.427 (0.874-2.330) | 0.155 |

| III + IV | 90 | 48 | 770 | 2.764 (1.823-4.190) | <0.001 |

| Ishak fibrosis scoref | 0.874 | ||||

| 0 | 74 | 30 | 2,131 | Ref. | |

| 1,2 | 31 | 9 | 1,372 | 0.917 (0.429-1.962) | 0.823 |

| 3,4 | 28 | 6 | NA | 0.682 (0.281-1.654) | 0.397 |

| 5 | 9 | 2 | 1,386 | 0.750 (0.177-3.167) | 0.695 |

| 6 | 69 | 17 | NA | 0.766 (0.418-1.403) | 0.388 |

| AFP (ng/ml)g | 0.832 | ||||

| ≤400 | 213 | 62 | 2,456 | Ref. | |

| >400 | 64 | 22 | 2,486 | 1.055 (0.645-1.724) | |

| Radical resectionh | 0.007 | ||||

| R0 | 323 | 110 | 1,875 | Ref. | |

| R1 + R2 + RX | 40 | 17 | 837 | 2.030 (1.213-3.395) | |

| Vascular invasioni | 0.155 | ||||

| No | 206 | 60 | 2,131 | Ref. | |

| Yes | 108 | 36 | 2,486 | 1.351 (0.892-2.047) | |

| Alcohol historyj | 0.896 | ||||

| No | 234 | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 117 | 1.026 (0.703-1.496) | |||

132 patients data were missing;

19 patients data were missing;

19 patients data were missing;

5 patients data were missing;

14 patients data were missing;

159 patients data were missing;

93 patients data were missing;

7 patients data were missing;

56 patients data were missing;

19 patients data were missing. Bold indicates significant P-values. HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; AFP, α-fetoprotein; MST, median survival time; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref., Reference.

Expression of LINC00668 and PCGs in tumor and non-tumor tissues

LINC00668, P2RY4 and CTAG2 exhibited high expression in non-tumor tissues, whereas other PCGs showed low expression levels in non-tumor tissues (Fig. 1). TCGA indicated that the expression of LINC00668, FAM86C1, SFN, NOC2L, PRDX1 and CTAG2 were significantly different between tumor and non-tumor tissues (P<0.05; Fig. 2). Moreover, all the PCGs that were significantly differentially expressed were upregulated in tumor tissues.

Figure 1.

Expressions of LINC00668 and its co-expression correlated protein-coding genes. (A-J) Expressions of, LINC00668, P2RY4, SPC25 (SPCS2), TDRD5, FTL, SFN, NOC2L, PRDX1, CATG2 and LZIC. CTAG2, cancer/testis antigen 2; FTL, ferritin light chain; LZIC, leucine zipper and CTNNBIP1 domain containing; NOC2L, nucleolar complex associated 2 homolog; P2RY4, pyrimidineregic receptor P2Y4; PRDX1, peroxiredoxin 1; SFN, stratifin; SPCS2, signal peptidase complex subunit 2; TDRD5, tudor domain containing 5.

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of LINC00668 and its co-expression correlated protein-coding genes in tumor and non-tumor tissues. (A-K) Scatter plots of, LINC00668, P2RY4, SPCS2, FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL, SFN, NOC2L, PRDX1, CATG2 and LZIC. CTAG2, cancer/testis antigen 2; FTL, ferritin light chain; LZIC, leucine zipper and CTNNBIP1 domain containing; NOC2L, nucleolar complex associated 2 homolog; P2RY4, pyrimidineregic receptor P2Y4; PRDX1, peroxiredoxin 1; SFN, stratifin; SPCS2, signal peptidase complex subunit 2; FAM86C1, family with sequence similarity 86 member C1; TDRD5, tudor domain containing 5.

Diagnostic, prognostic and joint-effect Analysis of LINC00668 and PCGs

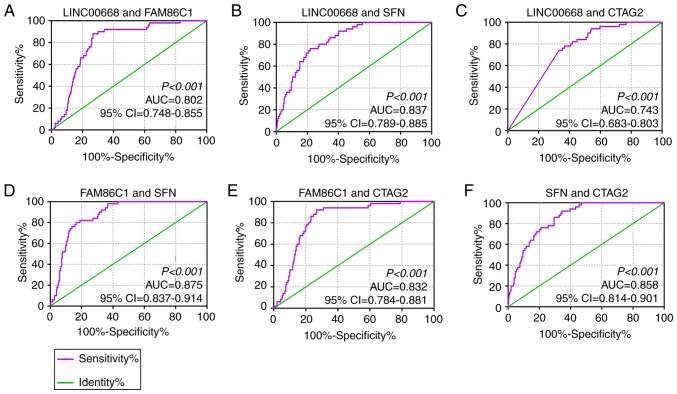

In the diagnostic analysis, FAM86C1, CTAG2 and SFN were found to be significant for the diagnosis of HCC (Fig. 3D, J and G, AUC=0.766, 0.725 and 0.820; P<0.0001, respectively), while LINC00668, P2RY4, and SPCS2 were found to be of weak diagnostic significance (Fig. 3A-C, AUC= 0.666, 0.640, and 0.614; P<0.001, P= 0.001, P= 0.009, respectively). Other PCGs, TDRD5, FTL, NOC2L, PRDX1 and LZIC, did not show any significance for the diagnosis of HCC (Fig. 3E-F, H-I, K, all AUCs<0.600). Then, joint-effect analysis was performed on LINC00668 and the significant PCGs (Fig. 4). Joint-effect analysis demonstrated that all of these have a larger AUC value than each alone.

Figure 3.

Diagnostic receiver operator curves of LINC00668 and its co-expression correlated protein-coding genes. (A-K) Diagnostic ROC curves of, in order, LINC00668, P2RY4, SPCS2, FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL, SFN, NOC2L, PRDX1, CATG2 and LZIC. CTAG2, cancer/testis antigen 2; FTL, ferritin light chain; LZIC, leucine zipper and CTNNBIP1 domain containing; NOC2L, nucleolar complex associated 2 homolog; P2RY4, pyrimidineregic receptor P2Y4; PRDX1, peroxiredoxin 1; SFN, stratifin; SPCS2, signal peptidase complex subunit 2; FAM86C1, family with sequence similarity 86 member C1; TDRD5, tudor domain containing 5; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; AUC, area under the curve; ROCs, receiver operator characteristic.

Figure 4.

Joint-effect analysis of diagnostic receiver operator curves of LINC00668 and diagnosis related genes. (A-F) Diagnostic receiver operator curves of, in order, LINC00668 and FAM86C1; LINC00668 and SFN; LINC00668 and CTAG2; FAM86C1 and SFN; FAM86C1 and CTAG2; SFN and CTAG2. CTAG2, cancer/testis antigen 2; FAM86C1, family with sequence similarity 86 member C1; SFN, stratifin; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; AUC, area under the curve.

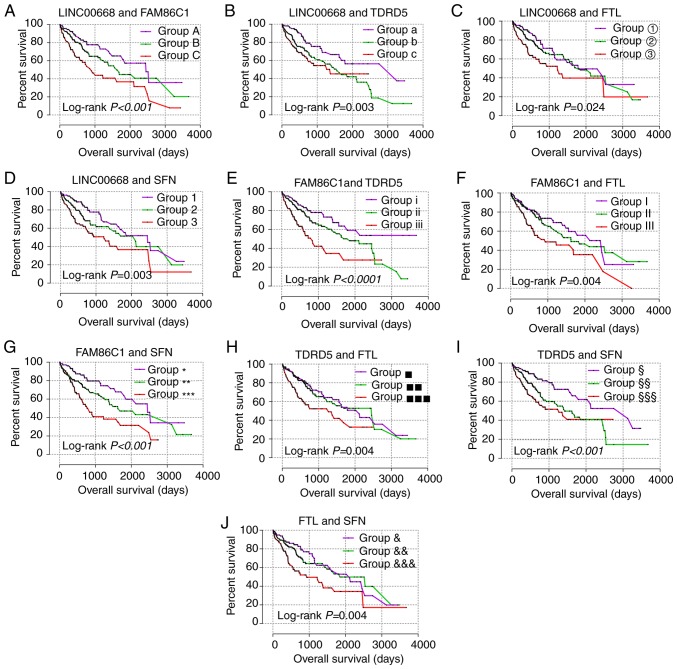

For the prognostic analysis, LINC00668, FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL and SFN exhibited prognostic significance in the multivariate analysis (Table III, adjusted P=0.029, 0.003, 0.012, 0.042 and 0.005, respectively), while LINC00668, FAM86C1, TDRD5, and SFN exhibited prognostic significance in the univariate analysis (Table III, Fig. 5, P=0.025, 0.001, 0.007, 0.003, respectively). Then, joint-effect analysis was performed on LINC00668 and the significant PCGs (Table IV, Fig. 6). The groups with low expression in both analyses exhibited the most significance for prognosis; and groups with high expression in both analyses presented as the poorest indicators of prognosis; while groups with both low and high expressions are set in the middle.

Table III.

Prognostic analysis of LINC00668 and genes for overall survival in The Cancer Genome Atlas database.

| Variables | Patients (n=370) | Overall survival

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of event | MST (days) | HR (95% CI) | Crude P-value | HR (95% CI) | Adjusted P-valuea | ||

| LINC00668 | 0.025 | 0.029 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 58 | 1,852 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 72 | 1,397 | 1.486 (1.051-2.102) | 1.540 (1.044-2.270) | ||

| P2RY4 | 0.865 | 0.646 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 65 | 1,694 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 65 | 1,624 | 1.031 (0.729-1.457) | 0.914 (0.622-1.343) | ||

| SPCS2 | 0.362 | 0.884 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 70 | 1,694 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 60 | 1,685 | 0.851 (0.602-1.203) | 0.971 (0.659-1.433) | ||

| FAM86C1 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 54 | 2,456 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 76 | 1,088 | 1.796 (1.266-2.550) | 1.853 (1.241-2.768) | ||

| TDRD5 | 0.007 | 0.012 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 59 | 2,116 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 71 | 1,372 | 1.624 (1.142-2.308) | 1.680 (1.123-2.514) | ||

| FTL | 0.218 | 0.042 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 64 | 1,791 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 66 | 1,685 | 1.242 (0.880-1.754) | 1.499 (1.015-2.214) | ||

| SFN | 0.003 | 0.005 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 54 | 2,131 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 76 | 1,372 | 1.706 (1.201-2.421) | 1.777 (1.194-2.646) | ||

| NOC2L | 0.408 | 0.996 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 64 | 1,791 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 66 | 1,560 | 1.157 (0.819-1.633) | 0.999 (0.677-1.473) | ||

| PRDX1 | 0.172 | 0.160 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 62 | 1,685 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 68 | 1,694 | 1.272 (0.901-1.795) | 1.318 (0.897-1.936) | ||

| CTAG2 | 0.078 | 0.283 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 59 | 2,131 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 71 | 1,397 | 1.366 (0.966-1.931) | 1.235 (0.840-1.816) | ||

| LZIC | 0.990 | 0.898 | |||||

| Low expression | 185 | 64 | 1685 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High expression | 185 | 66 | 1694 | 0.998 (0.706-1.410) | 0.975 (0.662-1.435) | ||

P-values were adjusted for radical resection, tumor stage and HBV infection; bold indicates significant P-values. NA, not available; MST, median survival time; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref., Reference; CTAG2, cancer/testis antigen 2; FTL, ferritin light chain; LZIC, leucine zipper and CTNNBIP1 domain containing; NOC2L, nucleolar complex associated 2 homolog; P2RY4, pyrimidineregic receptor P2Y4; PRDX1, peroxiredoxin 1; SFN, stratifin; SPCS2, signal peptidase complex subunit 2; FAM86C1, family with sequence similarity 86 member C1; TDRD5, tudor domain containing 5.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier plots of LINC00668 and its co-expression correlated protein-coding genes. (A-K) Kaplan-Meier plots of, LINC00668, P2RY4, SPCS2, FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL, SFN, NOC2L, PRDX1, CATG2 and LZIC. CTAG2, cancer/testis antigen 2; FTL, ferritin light chain; LZIC, leucine zipper and CTNNBIP1 domain containing; NOC2L, nucleolar complex associated 2 homolog; P2RY4, pyrimidineregic receptor P2Y4; PRDX1, peroxiredoxin 1; SFN, stratifin; SPCS2, signal peptidase complex subunit 2; FAM86C1, family with sequence similarity 86 member C1; TDRD5, tudor domain containing 5.

Table IV.

Joint-effect analysis of LINC00668 and genes for overall survival.

| Group | LINC00668 expression | FAM86C1 | TDRD5 | FTL | SFN | Overall survival

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events/total | MST (days) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted P-valuea | ||||||

| A | Low | Low | 26/97 | 2456 | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| B | Low | High | 60/176 | 1624 | 1.604 (0.946-2.721) | 0.080 | |||

| High | Low | ||||||||

| C | High | High | 44/97 | 899 | 2.861 (1.618-5.058) | <0.001 | |||

| a | Low | Low | 27/110 | 3258 | Ref. | 0.004 | |||

| b | Low | High | 63/150 | 1560 | 2.190 (1.314-3.649) | 0.003 | |||

| High | Low | ||||||||

| c | High | High | 40/110 | 1372 | 2.380 (1.350-4.196) | 0.003 | |||

| ① | Low | Low | 29/91 | 1791 | Ref. | 0.005 | |||

| ② | Low | High | 64/188 | 1852 | 1.297 (0.785-2.142) | 0.310 | |||

| High | Low | ||||||||

| ③ | High | High | 37/91 | 1229 | 2.350 (1.356-4.073) | 0.002 | |||

| 1 | Low | Low | 31/107 | 2456 | Ref. | 0.006 | |||

| 2 | Low | High | 50/156 | 2116 | 1.512 (0.908-2.518) | 0.112 | |||

| High | Low | ||||||||

| 3 | High | High | 49/107 | 1229 | 2.284 (1.370-3.806) | 0.002 | |||

| i | Low | Low | 24/94 | NA | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| ii | Low | High | 65/182 | 1852 | 1.691 (0.996-2.873) | 0.052 | |||

| High | Low | ||||||||

| iii | High | High | 41/94 | 837 | 3.415 (1.882-6.195) | <0.0001 | |||

| I | Low | Low | 33/107 | 2456 | Ref. | 0.003 | |||

| II | Low | High | 52/156 | 1624 | 1.351 (0.823-2.216) | 0.234 | |||

| High | Low | ||||||||

| III | High | High | 45/107 | 931 | 2.321 (1.399-3.851) | 0.001 | |||

| * | Low | Low | 26/105 | 2456 | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| ** | Low | High | 56/160 | 1624 | 1.814 (1.068-3.079) | 0.027 | |||

| High | Low | ||||||||

| *** | High | High | 48/105 | 837 | 2.856 (1.662-4.910) | <0.001 | |||

| ▪ | Low | Low | 35/97 | 2116 | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| ▪▪ | Low | High | 53/176 | 2456 | 1.127 (0.684-1.857) | 0.640 | |||

| High | Low | ||||||||

| ▪▪▪ | High | High | 42/97 | 1271 | 2.613 (1.508-4.525) | <0.001 | |||

| § | Low | Low | 27/109 | 3125 | Ref. | 0.002 | |||

| §§ | Low | High | 59/152 | 1423 | 2.093 (1.253-3.495) | 0.005 | |||

| High | Low | ||||||||

| §§§ | High | High | 44/109 | 1271 | 2.683 (1.534-4.693) | <0.001 | |||

| & | Low | Low | 32/100 | 2116 | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| && | Low | High | 54/170 | 1852 | 1.031 (0.627-1.694) | 0.904 | |||

| High | Low | ||||||||

| &&& | High | High | 44/100 | 931 | 2.445 (1.461-4.092) | <0.001 | |||

P-values were adjusted for radical resection, tumor stage and HBV infection; bold indicates significant P-values. NA, not available; MST, median survival time; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref., Reference; FAM86C1, family with sequence similarity 86 member C1; FTL, ferritin light chain; SFN, stratifin; TDRD5, tudor domain containing 5.

Figure 6.

Joint-effect analysis of Kaplan-Meier plots of LINC00668 and diagnosis-related genes. (A-J) Kaplan-Meier plots of LINC00668 and FAM86C1; LINC00668 and TDRD5; LINC00668 and FTL; LINC00668 and SFN; FAM86C1 and TDRD5; FAM86C1 and FTL; FAM86C1 and SFN; TDRD5 and FTL; TDRD5 and SFN; and FTL and SFN. FTL, ferritin light chain; FAM86C1, family with sequence similarity 86 member C1; SFN, stratifin; TDRD5, tudor domain containing 5.

GSEA

GSEA was conducted to explore the genome-wide potential molecular mechanisms of LINC00668 and its PCGs. The GSEA of LINC00668 indicated that it is involved in 'cell division', 'mitotic nuclear division', 'sister chromatid segregation', cell cycle phase transition, 'cell cycle G2 M phase transition', 'spindle', 'chromosome centromeric region', 'DNA dependent ATPase activity', 'chromatin binding', 'drug metabolism cytochrome P450', and 'fatty acid metabolism' (Fig. 7). The GSEA of FAM86C1 indicated that it is involved in 'ncRNA processing', 'RNA modification', 'RNA catabolic process', 'ncRNA metabolic process', 'ribosome biogenesis', 'ribosomal small subunit biogenesis', 'preribosome', 'ribosomal subunit', 'RRNA binding', 'ribosome', 'oxidative phosphorylation' and 'Alzheimer's disease' (Fig. 8). The GSEA of FTL indicated that it is involved in 'ncRNA metabolic process', 'mitochondrial translation', 'amide biosynthetic process', 'ncRNA processing', 'RRNA metabolic process', 'cytosolic part', 'structural of constituent of ribosome', 'RRNA binding', 'ribosome', 'proteasome' and 'oxidative phosphorylation' (Fig. 9). The GSEA of SFN and TDRD5 indicated that they are involved in regulation of cell cycle, cell cycle phase transition, 'DNA repair', 'regulation of nuclear division', 'cellular respiration', 'mitochondrial translation', 'oxidative phosphorylation', 'respiratory chain', 'PPAR signaling pathway', 'Alzheimer's disease', 'fatty acid metabolism', as well as 'complement and coagulation cascades' (Figs. S1 and 2).

Figure 7.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of LINC00668 using GO and KEGG pathways. (A-I) Gene ontology results of LINC00668; (J-L) KEGG pathway results of LINC00668. GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score.

Figure 8.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of FAM86C1 using GO and KEGG pathways. (A-I) Gene ontology results of FAM86C1; (J-L) KEGG pathway results of FAM86C1. FAM86C1, family with sequence similarity 86 member C1; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score.

Figure 9.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of FTL using GO and KEGG pathways. (A-I) Gene ontology results of FTL; (J-L) KEGG pathway results of FTL. FTL, ferritin light chain; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score.

Nomogram, co-expression matrix, GGI and GO network

A nomogram was constructed using tumor stage, radical resection, HBV infection, LINC00668, FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL, and SFN (Fig. 10A). Low expression of LINC00668, FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL, and SFN had fewer points, while radical resection, without HBV infection, and a tumor stage of III and IV accounted for fewer points as well. Additionally, fewer points suggest better OS. The co-expression matrix among LINC00668 and the PCGs (Fig. 10B) was also constructed. Most of them were positively correlated and showed statistical significance. GGI showed the co-expression relationships among these PCGs (Fig. 10C). In addition, CC and MF were visualized, and complex BPs were found using 10 PCGs (Fig. S3). The intracellular ferritin complex, signal peptidase complex and protein kinase C inhibitor activity were enriched in the network.

Figure 10.

Nomogram, co-expression matrix and gene-gene interaction network of LINC00668 and protein-coding genes. (A) Nomogram constructed using LINC00668, FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL, SFN, tumor stage, radical resection and HBV infection status; (B) Co-expression matrix of LINC00668 and its protein-coding genes; blue and red indicate positive and negative correlation, respectively. *, **, and *** denote P≤0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively. (C) Co-expression network of gene-gene interactions of LINC00668 and its protein-coding genes. HBV, hepatitis B virus; FTL, ferritin light chain; FAM86C1, family with sequence similarity 86 member C1; SFN, stratifin; TDRD5, tudor domain containing 5.

Pharmacological targets and drugs

The DEGs were acquired using edgeR. Pharmacological targets and drugs were acquired from the Connectivity Map that was constructed using the DEGs. Negatively associated drugs are potential pharmacological targets toward LINC00668 (Tables V and SII). Heatmaps and volcano plots of these DEGs are presented in Fig. S4, while the chemical composition and 2D structure of these seven potential target drugs are presented in Fig. S5. Enrichment analysis of the DEGs was performed using DAVID. The results included 'cell division', 'mitotic nuclear division', 'sister chromatid cohesion', 'cell cycle' and 'spliceosome enrichment'. Detailed GO terms and KEGG pathways are presented in Tables SIII and SIV, respectively. The GO terms visualized by BinGO are shown in Fig. S6.

Table V.

Pharmacological target and drug.

| Drug | PubChem CID | Mean | Enrichment | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indolylheptylamine | 35874 | −0.82 | −0.974 | 0.00139 |

| Mimosine | 3862 | −0.47 | −0.900 | 0.00188 |

| Disopyramide | 3114 | −0.375 | −0.794 | 0.00358 |

| Lidocaine | 3676 | −0.441 | −0.720 | 0.00374 |

| NU-1025 | 135398517 | −0.585 | −0.947 | 0.00622 |

| Bumetanide | 2471 | −0.39 | −0.692 | 0.01930 |

| DQNLAOWBTJPFKL-PKZXCIMASA-N | 5279552 | −0.436 | −0.900 | 0.02014 |

Discussion

In the present study, we explored lncRNA LINC00668 and its associated PCGs for their potential implications in HCC. We found that LINC00668, FAM86C1, CTAG2 and SFN are of significance for the diagnosis of HCC. Joint-effect analysis of these genes revealed that their diagnostic significance was better when combined than alone. Then, prognostic analysis indicated that LINC00668, FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL and SFN are of prognostic significance in HCC. Furthermore, joint-effect analysis of these genes indicated that their diagnostic significance was better when combined than alone. In order to find their potential molecular mechanisms, GSEA found that LINC00668 and its PCGs have various functions in 'ncRNA processing', 'DNA repair', 'cell division', 'mitotic nuclear division', 'cell cycle phase transition', 'oxidative phosphorylation', 'drug metabolism cytochrome P450', and 'PPAR signaling pathway'. A nomogram was constructed using clinical factors, and LINC00668 and its PCGs were used to predict 1, 3 and 5 year HCC OS. Afterwards, pharmacological target drugs were identified and seven drugs: Indolylheptylamine, mimosine, disopyramide, lidocaine, NU-1025, bumetanide and DQNLAOWBTJPFKL-PKZXCIMASA-N, which may serve as potential targets with respect to LINC00668 for HCC treatment, were identified.

The discovery of many lncRNAs has notably improved our understanding of the biological behavior of many complicated diseases, including tumors. Several studies have demonstrated abnormal expression of lncRNAs in tumors, which may pinpoint to the spectrum of cancer progression and predict patient prognosis (32,33). LncRNAs and microRNAs are major constituents of the ncRNA family, and it has been revealed that microRNAs serve a pivotal role in HCC progression (34). LncRNAs function as critical regulators of many biological behaviors via modulating chromatin organization, as well as regulation at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels (35,36). In addition, several studies have indicated that lncRNAs function as critical factors of tumorigenesis, and that their dysregulation induces tumor initiation, tumor growth and metastasis (37,38). Particularly in tumor cells, lncRNAs can affect the proliferation, growth, cycle progression, apoptosis and migration of transformed cancer cells (39,40). For instance, functioning as a molecular decoy for microRNA-221-3P, lncRNA GAPLINC modulates CD44-dependent cell invasion and is associated with poor prognosis of gastric cancer (41). LncRNA FAL1 has been identified as an oncogenic lncRNA, and is associated with BMI1 and suppresses p21 expression in tumors (42). Activated by TGF-β, lncRNA-ATB binds to interleukin (IL)-11 mRNA, and the autocrine induction of IL-11 and triggering of the STAT3 signaling pathway promotes the invasion-metastasis cascade in HCC cell lines (43). LncRNAs HULC (44) and LINC00974 (45) have been reported to be involved in HCC development and progression.

LncRNA LINC00668 (NR_034100.1) is a 1,751 bp lncRNA, which is located on chromosome 18p11.31 (46). Our study found that LINC00668 is upregulated in HCC tumor tissues and was associated with poor prognosis, which indicates that LINC00668 functions as an oncogene in HCC. Moreover, our present findings found that LINC00668 expression can affect cell division, cell cycle, mitotic nuclear division, sister chromosome segregation and drug metabolism cytochrome P450. Therefore, we speculate that LINC00668 may function by influencing tumor progression and development. Zhao et al (21) found that LINC00668 expression is associated with age, T stage, clinical stage, cervical lymph node metastasis, and pathological differentiation degrees. Experiments in vitro indicated that LINC00668 plays an important role by promoting cell proliferation, migration, and the invasion ability of TU177 and TU212 cell lines (21). LINC00668 was determined to function as an oncogene, is upregulated in tumor tissue and may serve as a potential biomarker for the targeted treatment of LSCC (21). In brief, we determined that LINC00668 plays a consistent role as an oncogene in tumors, and that its expression is upregulated in LSCC and HCC tumor tissues. Zhang (46) also indicated that LINC00668 is upregulated in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) tissues and cell lines, and induces poor prognosis. By competitively sponging microRNA-297, LINC00668 upregulates target gene vascular endothelial growth factor A of microRNA-297 and facilitates the proliferation of OSCC cells, which demonstrates that LINC00668 plays a role in the competitive endogenous RNA network (46). It was speculate that LINC00668 may serve its pivotal role via the initiation and progression of OSCC (46). These studies also indicated important roles of LINC00668 in OSCC progression and prognosis. In total, our findings are consistent with that of Zhang (46), in which LINC00668 is upregulated in tumor tissues and is an indicator of poor prognosis that may play important roles in tumor progression. Furthermore, its related top 10 PCGs were explored to investigate their significance in the diagnosis and prognosis of HCC. We found these genes to have distinct diagnostic and prognostic values in HCC. Of note, potential molecular mechanisms of these genes were explored as well as LINC00668, including FAM86C1, FTL, SFN and TDRD5. These potential processes included oxidative phosphorylation, preribosome, ribosome, NCRNA processing, fatty acid metabolism, complement and coagulation cascades. Subsequently, we visualized specific biological processes they were involved in.

In addition, LINC00668 has been found to be upregulated in GC tissues and functions as an independent prognosis indicator for OS (22). LINC00668 plays a role in cell cycle by epigenetically silencing cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors by binding to polycomb repressive complex 2, regulating cell growth (22). LINC00668 was also found to be a predictor of poor prognosis of GC, which is consistent with our present findings (22). LINC00668 has been reported to be downregulated in lung adenocarcinoma but was determined to no be associated with patient prognosis or a biomarker for lung adenocarcinoma (20).

LncRNAs function through their co-expressed PCGs, and accordingly LINC00668 exerts its role via its top 10 PCGs. Our study indicates that FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL and SFN have prognostic value for HCC, while FAM86C1, SFN, and CATG2 have diagnostic value for HCC. Joint-effect analysis of LINC00668 and FAM86C1, SFN and CATG2 was found to have better diagnostic value than any one of these genes alone. These results indicated their potential application in HCC. However, the significance of FAM86C1 in diseases requires further investigation. TDRD5 has been found to bind to piwi-interacting (pi)RNA precursors and selectively enhances pachytene piRNA processing in mice; it has been speculated that it is involved in piRNA biogenesis (47). Therefore, the potential values of the aforementioned genes need further investigation in other cancers. In addition, the diagnostic significance of α-fetoprotein in this dataset was also evaluated. AFP had AUC=0.613, P=0.010 (data not shown), which did not meet the criteria of candidate diagnostic biomarkers. Therefore, we concluded that some PCGs were potential diagnostic biomarkers for HCC.

FTL, an iron utilization gene, has been reported to be associated with OS and its low expression is linked to the poor prognosis of HCC (48). Our present results of GO analysis found that FTL was enriched in ferric iron binding (GO:0008199). However, our results also indicated that the high expression of FTL was associated with poor prognosis, which in inconsistent with the results of Shang et al (48). Specifically, Shang et al (48) identified that the low expression of FTL leads to poor prognosis, on the basis of univariate analysis, whereas our results were based on a multivariate analysis. Liu et al (49) found that FTL was a DEG and is upregulated in HCC, which is consistent with our the results of this study. Wang et al (50) reported that tumor-associated antigens combined with FTL, AHSG and KRT23 had high sensitivity and specificity, and these antigens can act as candidate biomarkers for HCC diagnosis. Given the inconsistency in the prognostic and diagnostic values of FTL, further investigation should be conducted to determine its role in HCC. Of note, its potential significance in diseases, especially in malignancies, should also be evaluated further. Moreover, we constructed a nomogram to predict possible risk for 1, 3- and 5-year OS. LINC00668, and prognosis-related genes, including FAM86C1, FTL, SFN and TDRD5, and clinical factors, including tumor stage, radical resection, HBV infection status, were employed in the nomogram for survival prediction at hepatectomy. According to the above findings, we concluded that this nomogram provided notable results for survival prediction in HCC. We also identified seven potential target drugs: Indolylheptylamine, mimosine, disopyramide, lidocaine, NU-1025, bumetanide and DQNLAOWBTJPFKL-PKZXCIMASA-N of LINC00668 in HCC via the Connectivity Map. The Connectivity Map database can provide a unique method of drug development through the comparison of potential chemical compounds that can be used to treat diseases, including tumors, and it has been accepted by several researchers (51,52). Xiao et al (53) utilized expression profile chip data and a Connectivity Map to explore the molecular mechanisms of Hirschsprung's disease and candidate target drugs. They found certain chemical compounds that may helpful for minimizing the damage induced by the progression of Hirschsprung's disease (53). We further visualized specific structures of these potential target drugs for their candidate clinical application. Further investigations concerning these potential target drugs may facilitate the development of novel strategies for the treatment of HCC.

Additionally, genetic variants concerning TP53 and catenin β-1 (CTNNB1) mutations have been linked to HCC, including diagnostic significance. Our study found that TP53 mutations did not indicate diagnostic significance (AUC:0.648, data not shown), which is less than the cutoff of 0.700. However, CTNNB1 mutations suggested diagnostic significance (AUC:0.702, data not shown), which is slightly higher than the cutoff value. In addition, genes exhibiting diagnostic significance, including FAM86C1, CTAG2 and SFN, had higher AUCs than CTNNB1 (AUC=0.766, 0.725 and 0.820, respectively). These results suggested that FAM86C1, CTAG2 and SFN may have greater diagnostic value for HCC than CTNNB1 and TP53; although further investigation is required.

There are certain limitations to the present study that need to be noted. Firstly, our findings need to be validated in a larger population. Secondly, a multi-center and validation cohort are warranted in order to explore clinical significance. In addition, functional trials regarding LINC00668 and its related PCGs are warranted to verify their function in HCC.

Our present study identified that lncRNA LINC00668 is differentially expressed and upregulated in HCC tissue. It functions as an oncogene and its high expression leads to poor prognosis for HCC. Its co-expressed correlated PCGs have been determined for diagnostic, value including FAM86C1, CTAG2 and SFN, and prognostic value, including FAM86C1, TDRD5, FTL and SFN for HCC. Investigation into the molecular mechanism indicated that LINC00668 affects cell division, cell cycle, mitotic nuclear division, sister chromosome segregation and drug metabolism cytochrome P450. We speculate that it serves important roles in the progression and development of HCC. Analysis of pharmacological targets revealed 7 candidate target drugs: Indolylheptylamine, mimosine, disopyramide, lidocaine, NU-1025, bumetanide and DQNLAOWBTJPFKL-PKZXCIMASA-N. Although these drugs need further validation, this study provides novel insight into potential treatment strategies for HCC. Additionally, further functional trials and validation with a larger cohort are warranted to verify the clinical value of these findings.

Supplementary Data

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- LSCC

laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- GC

gastric cancer

- OSCC

oral squamous cell carcinoma

- DEG

differentially expressed gene

- PCG

protein-coding gene

- AUC

area under curve

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- GSEA

gene set enrichment analysis

- BP

biological process

- CC

cellular component

- MF

molecular function

- GO

gene ontology

- OS

overall survival

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- GGI

gene-gene interaction

- DAVID

database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81560535, 81072321, 30760243, 30460143, 30560133 and 81802874), Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province of China (grant no. 2017JJB140189y), Key laboratory of High-Incidence-Tumor Prevention & Treatment (Guangxi Medical University), Ministry of Education (GKE2018-01), 2009 Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET), Guangxi Nature Sciences Foundation (grant no. GuiKeGong 1104003A-7), and Guangxi Health Ministry Medicine Grant (Key-Scientific Research-Grant, grant no. Z201018). The present study is also partly supported by Scientific Research Fund of the Health and Family Planning Commission of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (grant no. Z2016318), The Basic Ability Improvement Project for Middle-aged and Young Teachers in Colleges and Universities in Guangxi (grant no. 2018KY0110), 2018 Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education (grant no. YCBZ2018036). As well as, the present study is also partly supported by Research Institute of Innovative Think-tank in Guangxi Medical University (The gene-environment interaction in hepatocarcinogenesis in Guangxi HCCs and its translational applications in the HCC prevention). We also acknowledge the supported by the National Key Clinical Specialty Programs (General Surgery & Oncology) and the Key Laboratory of Early Prevention & Treatment for Regional High-Incidence-Tumor (Guangxi Medical University), Ministry of Education, China.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contribution

XW and TP designed this manuscript; XZ, JL, ZL, LZ, YG, JH, LY, QW, CY, XL, TY, CH, GZ, XY and TP conducted the study and analyzed the data. XW wrote the manuscript, and TP guided the writing.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Testino G, Leone S, Patussi V, Scafato E, Borro P. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Diagnosis and proposal of treatment. Minerva Med. 2016;107:413–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li S, Huang Y, Huang Y, Fu Y, Tang D, Kang R, Zhou R, Fan XG. The long non-coding RNA TP73-AS1 modulates HCC cell proliferation through miR-200a-dependent HMGB1/RAGE regulation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:51. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0519-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomaa AI, Khan SA, Toledano MB, Waked I, Taylor-Robinson SD. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology, risk factors and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4300–4308. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varnholt H, Drebber U, Schulze F, Wedemeyer I, Schirmacher P, Dienes HP, Odenthal M. MicroRNA gene expression profile of hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;47:1223–1232. doi: 10.1002/hep.22158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: From genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM. Liver cancer: Time to evolve trial design after everolimus failure. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:506–507. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka S, Arii S. Molecular targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma in the current and potential next strategies. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:289–296. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.St Laurent G, Wahlestedt C, Kapranov P. The Landscape of long noncoding RNA classification. Trends Genet. 2015;31:239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devaux Y, Zangrando J, Schroen B, Creemers EE, Pedrazzini T, Chang CP, Dorn GW, II, Thum T, Heymans S, Cardiolinc network Long noncoding RNAs in cardiac development and ageing. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:415–425. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma L, Bajic VB, Zhang Z. On the classification of long non-coding RNAs. RNA Biol. 2013;10:925–933. doi: 10.4161/rna.24604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penny GD, Kay GF, Sheardown SA, Rastan S, Brockdorff N. Requirement for Xist in X chromosome inactivation. Nature. 1996;379:131–137. doi: 10.1038/379131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Hedge VL, Kirkham L, Farzaneh F, Williams GT. Growth arrest in human T-cells is controlled by the non-coding RNA growth-arrest-specific transcript 5 (GAS5) J Cell Sci. 2008;121:939–946. doi: 10.1242/jcs.024646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huo X, Han S, Wu G, Latchoumanin O, Zhou G, Hebbard L, George J, Qiao L. Dysregulated long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in hepatocellular carcinoma: Implications for tumori-genesis, disease progression, and liver cancer stem cells. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:165. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0734-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pickard MR, Williams GT. Regulation of apoptosis by long non-coding RNA GAS5 in breast cancer cells: Implications for chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:359–370. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2974-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickard MR, Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Williams GT. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 regulates apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1613–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiaoguang Z, Meirong L, Jingjing Z, Ruishen Z, Qing Z, Xiaofeng T. Long noncoding RNA CPS1-IT1 suppresses cell proliferation and metastasis in human lung cancer. Oncol Res. 2017;25:373–380. doi: 10.3727/096504016X14741486659473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang M, Wang W, Li T, Yu X, Zhu Y, Ding F, Li D, Yang T. Long noncoding RNA SNHG1 predicts a poor prognosis and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;80:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao B, Xu H, Ai X, Adalat Y, Tong Y, Zhang J, Yang S. Expression profiles of long noncoding RNAs in lung adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:5383–5390. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S167633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao L, Cao H, Chi W, Meng W, Cui W, Guo W, Wang B. Expression profile analysis identifies the long non-coding RNA landscape and the potential carcinogenic functions of LINC00668 in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Gene. 2019;687:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang E, Yin D, Han L, He X, Si X, Chen W, Xia R, Xu T, Gu D, De W, et al. E2F1-induced upregulation of long noncoding RNA LINC00668 predicts a poor prognosis of gastric cancer and promotes cell proliferation through epigenetically silencing of CKIs. Oncotarget. 2016;7:23212–23226. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paci P, Colombo T, Farina L. Computational analysis identifies a sponge interaction network between long non-coding RNAs and messenger RNAs in human breast cancer. BMC Syst Biol. 2014;8:83. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-8-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao Q, Liu C, Yuan X, Kang S, Miao R, Xiao H, Zhao G, Luo H, Bu D, Zhao H, et al. Large-scale prediction of long non-coding RNA functions in a coding-non-coding gene co-expression network. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3864–3878. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaul YD, Yuan B, Thiru P, Nutter-Upham A, McCallum S, Lanzkron C, Bell GW, Sabatini DM. MERAV: A tool for comparing gene expression across human tissues and cell types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D560–D566. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montojo J, Zuberi K, Rodriguez H, Kazi F, Wright G, Donaldson SL, Morris Q, Bader GD. GeneMANIA Cytoscape plugin: Fast gene function predictions on the desktop. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2927–2928. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maere S, Heymans K, Kuiper M. BiNGO: A Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3448–3449. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maass PG, Luft FC, Bähring S. Long non-coding RNA in health and disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014;92:337–346. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang G, Lu X, Yuan L. LncRNA: A link between RNA and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:1097–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong CM, Kai AK, Tsang FH, Ng IO. Regulation of hepato-carcinogenesis by microRNAs. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2013;5:49–60. doi: 10.2741/E595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ulitsky I, Bartel DP. lincRNAs: Genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell. 2013;154:26–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagano T, Fraser P. No-nonsense functions for long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2011;145:178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai MC, Spitale RC, Chang HY. Long intergenic noncoding RNAs: New links in cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spizzo R, Almeida MI, Colombatti A, Calin GA. Long non-coding RNAs and cancer: A new frontier of translational research? Oncogene. 2012;31:4577–4587. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H, Chen Z, Wang X, Huang Z, He Z, Chen Y. Long non-coding RNA: A new player in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:37. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, Zhuang C, Liu Y, Chen M, Chen Y, Chen Z, He A, Lin J, Zhan Y, Liu L, et al. Synthetic tetracycline-controllable shRNA targeting long non-coding RNA HOXD-AS1 inhibits the progression of bladder cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:99. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu Y, Wang J, Qian J, Kong X, Tang J, Wang Y, Chen H, Hong J, Zou W, Chen Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA GAPLINC regulates CD44-dependent cell invasiveness and associates with poor prognosis of gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:6890–6902. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu X, Feng Y, Zhang D, Zhao SD, Hu Z, Greshock J, Zhang Y, Yang L, Zhong X, Wang LP, et al. A functional genomic approach identifies FAL1 as an oncogenic long noncoding RNA that associates with BMI1 and represses p21 expression in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:344–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan JH, Yang F, Wang F, Ma JZ, Guo YJ, Tao QF, Liu F, Pan W, Wang TT, Zhou CC, et al. A long noncoding RNA activated by TGF-β promotes the invasion-metastasis cascade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:666–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cui M, Xiao Z, Wang Y, Zheng M, Song T, Cai X, Sun B, Ye L, Zhang X. Long noncoding RNA HULC modulates abnormal lipid metabolism in hepatoma cells through an miR-9-mediated RXRA signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2015;75:846–857. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang J, Zhuo H, Zhang X, Jiang R, Ji J, Deng L, Qian X, Zhang F, Sun B. A novel biomarker Linc00974 interacting with KRT19 promotes proliferation and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1549. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang CZ. Long intergenic non-coding RNA 668 regulates VEGFA signaling through inhibition of miR-297 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;489:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding D, Liu J, Midic U, Wu Y, Dong K, Melnick A, Latham KE, Chen C. TDRD5 binds piRNA precursors and selectively enhances pachytene piRNA processing in mice. Nat Commun. 2018;9:127. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02622-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen Y, Li X, Zhao B, Xue Y, Wang S, Chen X, Yang J, Lv H, Shang P. Iron metabolism gene expression and prognostic features of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:9178–9204. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Y, Zhu X, Zhu J, Liao S, Tang Q, Liu K, Guan X, Zhang J, Feng Z. Identification of differential expression of genes in hepatocellular carcinoma by suppression subtractive hybridization combined cDNA microarray. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:943–951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang K, Xu X, Nie Y, Dai L, Wang P, Zhang J. Identification of tumor-associated antigens by using SEREX in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2009;281:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brum AM, van de Peppel J, Nguyen L, Aliev A, Schreuders-Koedam M, Gajadien T, van der Leije CS, van Kerkwijk A, Eijken M, van Leeuwen JPTM, van der Eerden BCJ. Using the Connectivity Map to discover compounds influencing human osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:4895–4906. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Busby J, Murray L, Mills K, Zhang SD, Liberante F, Cardwell CR. A combined connectivity mapping and pharmacoepidemiology approach to identify existing medications with breast cancer causing or preventing properties. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27:78–86. doi: 10.1002/pds.4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xiao SJ, Zhu XC, Deng H, Zhou WP, Yang WY, Yuan LK, Zhang JY, Tian S, Xu L, Zhang L, Xia HM. Gene expression profiling coupled with Connectivity Map database mining reveals potential therapeutic drugs for Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:1716–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.