Abstract

Repeated cocaine causes enduring changes in dopamine and glutamate transmission in the nucleus accumbens, and dopamine and glutamate terminals synapse on GABAergic accumbens neurons. The present study demonstrates that there are changes in GABA transmission in the accumbens at 3 weeks after discontinuing daily cocaine injections. No-net flux microdialysis revealed a significant increase in the basal levels of extracellular GABA in the accumbens of cocaine-treated rats. The elevated extracellular GABA was normalized by blocking voltage-dependent Na+ channels and provided increased tone on GABAB presynaptic autoreceptors and heteroreceptors because blocking GABAB receptors produced a greater elevation in extracellular GABA, dopamine, and glutamate in cocaine-treated compared with control subjects. For many G-protein-coupled receptors, increased agonist can cause receptor desensitization. Consistent with GABAB receptor desensitization, baclofen-stimulated GTPγS binding was reduced, and the reduction in G-protein coupling was accompanied by reduced Ser phosphorylation of the GABAB2 receptor subunit. No effect by repeated cocaine was found in the levels of total GABAB1or GABAB2 protein. Together, these data demonstrate that withdrawal from repeated cocaine treatment produces an increase in the basal levels of extracellular GABA in the accumbens that depends on neuronal activity. The increase may be mediated in part by functional desensitization of GABAB receptors, likely the result of diminished Ser phosphorylation of the GABAB2 receptor.

Keywords: GABA, cocaine, immunoblot, phosphorylation, microdialysis, glutamate

Introduction

Research during the past decade shows that repeated cocaine administration causes a number of alterations in dopamine and glutamate transmission in the nucleus accumbens that may be linked to addiction (Vanderschuren and Kalivas, 2000; Nestler, 2001). These studies are in accord with experiments that point to the accumbens as a critical substrate for both drug reward and the expression of behaviors indicative of cocaine addiction (Everitt and Wolf, 2002). Dopamine and glutamate terminals synapse on GABAergic spiny cells in the nucleus accumbens (Sesack and Pickel, 1990), and spiny cell axons collateralize to provide GABAergic innervation of near adjacent spiny neurons (Pennartz et al., 1994). In addition, there are dense GABAergic afferents to the accumbens, as well as a small population of GABAergic interneurons (Brog et al., 1993; Pennartz et al., 1994). Despite the central physiological role played by GABA in the accumbens, compared with glutamate and dopamine, there is relatively less information on the capacity of repeated cocaine to produce neuroadaptations in accumbens GABA transmission, especially at late withdrawal times when many addiction-related behaviors, such as sensitization, craving, and paranoia continue to be expressed. Understanding long-lasting interactions between repeated cocaine and GABA transmission is especially important, because the cocaine-induced changes in gene expression in GABAergic spiny cells are mediated by dopamine and glutamate and are hypothesized to be primary adaptive events in the development and expression of addiction (Nestler, 2001). Also, there is evidence for reciprocal presynaptic modulation between GABA, dopamine, and glutamate in the accumbens (Harsing and Zigmond, 1997; Schoffelmeer et al., 2000), posing a role for altered GABA transmission in mediating the cocaine-induced adaptations in dopamine and glutamate transmission (Everitt and Wolf, 2002).

The present study evaluated the possibility that repeated cocaine combined with 3 weeks of withdrawal alters in vivopresynaptic GABA transmission in the accumbens. Microdialysis was used to demonstrate that the basal levels of extracellular GABA are elevated by repeated cocaine. This observation generated two additional hypotheses. (1) The elevated basal GABA levels result from a decreased capacity of GABAB autoreceptors to regulate GABA release. Previous studies supporting this possibility include repeated amphetamine treatment decreases G-protein coupling of GABAB receptors in the accumbens (Zhang et al., 2000) and repeated cocaine decreases the electrophysiological impact of GABAB receptor stimulation in the lateral septum (Shoji et al., 1997). (2) Elevated extracellular GABA provides increased tone on presynaptic GABABheteroreceptors that decreases the basal level of glutamate. Previous studies have shown a decrease in basal extracellular levels of glutamate in the accumbens after repeated cocaine (Pierce et al., 1996;Hotsenpiller et al., 2001). Also, repeated amphetamine treatment enhances tonic modulation of GABAB receptors regulating dopamine and glutamate release in the ventral tegmental area (Giorgetti et al., 2002). To evaluate these hypotheses, the level of GABAB receptor protein and phosphoprotein was measured, as was the efficiency of G-protein coupling. Also, in vivo microdialysis was used to examine the capacity of GABAB receptors to regulate the extracellular levels of glutamate and dopamine.

Materials and Methods

Animals housing and surgery. All experiments were conducted according to specifications of the National Institute of Health guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male Sprague Dawley (Raleigh, NC) rats, weighing between 250 and 300 gm, were individually housed and maintained on a 12 hr light/dark cycle (7:00 A.M., 7:00 P.M.) with access to food and waterad libitum. All experimentation was conducted during the light period. Using ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (3 mg/kg) anesthesia, dialysis guide cannulas (20 gauge, 14 mm; Small Parts, Roanoke, VA) were implanted over the nucleus accumbens [+1.6 mm anterior to bregma, ±1.6 mm mediolateral, and −4.7 mm ventral to the skull surface, according to the atlas ofPaxinos and Watson (1986)] using a 6° angle from vertical. The guide cannulas were fixed to the skull with four stainless steel skull screws (Small Parts) and dental acrylic.

Repeated cocaine treatment. Cocaine was donated by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. One week after arrival in the animal facility, rats were treated with either cocaine (15 mg/kg, i.p.) or the same volume (1.0 ml/kg, i.p.) of saline (day 1). On days 2–6 the rats received saline or 30 mg/kg cocaine and, on day 7, received 15 mg/kg cocaine. Brain dissection or microdialysis was performed after 3 weeks withdrawal from the last saline or cocaine injection. This treatment regimen has been shown previously to produce enduring behavioral sensitization and changes in extracellular glutamate levels (Pierce et al., 1996). In addition, examining 3 weeks of withdrawal potentially provides a better estimate of the neuroadaptations mediating the long-lasting behavioral effects of cocaine (for review, see White and Kalivas, 1998; Wolf, 1998).

Microdialysis. Dialysis probes were constructed as described by Robinson and Whishaw (1988) with some modifications (including using smaller silica tubing). The active region of the dialysis membrane is 0.8–1.5 mm in length and ∼175 μm in diameter Probes were inserted into the accumbens at least 12 hr before the experiment to minimize the effects of damage-induced dopamine and glutamate release during the experiment. On the day of the experiment, dialysis buffer (5 mm glucose, 2.5 mm KCl, 140 mm NaCl, 1.4 mmCaCl2, 1.2 mmMgCl2, and 0.15% PBS, pH 7.4) was perfused through the probe (2.0 μl/min) for at least 2 hr before sample collection. Dialysis samples were collected every 20 min into 10 μl of dialysis buffer (for glutamate and GABA) or mobile phase (for dopamine) containing an internal standard.

The GABAB agonist R(+)-baclofen and the GABAB antagonist 2-OH-saclofen were purchased from Tocris Cookson (Ballwin, MO). GABA and tetrodotoxin (TTX) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Both baclofen and 2-OH-saclofen were initially dissolved in 1 equivalent NaOH (Sigma) and neutralized with 0.1N HCl (Sigma) to a concentration of 10−2m. Other drugs are directly dissolved in filtered dialysis buffer. Working concentrations were then made by diluting with filtered buffer.

Quantification of GABA. The concentration of GABA in each sample was determined using a modified “Fast Analysis of GABA” provided by ESA (Bedford, MA). The dialysis samples were collected into 10 μl of dialysis buffer (plus 40 μl of sample in 20 min) containingdl-α-amino-n-butyric acid (dl-ABA) as the internal standard for GABA. Methanol (15%) mobile phase containing 100 mmNaH2PO4, pH 4.6, and a reversed-phase column (4.6 × 80, 3 μm; model HR-80; Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN) were used to separate the amino acids. A coulometric electrochemical detection system using three electrodes [preinjection guard electrode, +0.7 V; reduction electrode 1 (E1), 0.4 V; reduction electrode 2 (E2), 0.65 V] was used for quantification. Area under the curve of the GABA anddl-ABA peaks was measured with an ESA 501 Chromatography Data System. GABA values were normalized to the internal standard dl-ABA and compared with an external standard curve for quantification.

Quantification of glutamate. Glutamate in the dialysis sample was measured using an HPLC system with fluorescent detector. The dialysis samples were collected into 10 μl of 0.05m HCl containing 2 pmol of homoserine as an internal standard. The mobile phase consisted of 13% acetylnitrile (v/v), 100 mmNaH2PO4, and 0.1 mm EDTA, pH 6.0. A reversed-phase column (10 cm, 3 μm C-18 reversed phase; Bioanalytical Systems) was used to separate the amino acids, and precolumn derivatization of amino acids with o-phthalaldehyde was performed using an ESA model 540 autosampler. Glutamate was detected by a fluorescence spectrophotometer (LINEAR FLOUR LC 305; ESA) using an excitation wavelength of 336 nm and an emission wavelength of 420 nm. Glutamate content in each sample was quantified with the ESA 501 Chromatography Data System.

Quantification of dopamine. For the measurement of extracellular dopamine, samples were collected into 10 μl of mobile phase (4.76 mm citric acid, 150 mm NaH2PO4, 50 μm EDTA, 3 mm SDS, 10% methanol (v/v), and 15% acetylnitrile (v/v), pH 5.6, plus 2.0 pmol of dihydroxybenzylamine as an internal standard), and all samples were frozen at −80°C. The samples were subsequently thawed and placed in an ESA model 540 autosampler connected to an HPLC system with electrochemical detection. Dopamine was separated using a 10 cm C18 reversed-phase column (Bioanalytical Systems) and oxidized–reduced using coulometric detection (ESA). Three electrodes were used: a preinjection port guard cell (+0.4 V) to oxidize the mobile phase, an oxidation analytical electrode (E1, −0.1 V), and a reduction analytical electrode (E2, +0.2 V). The area under curve of the dopamine peak was measured with ESA 501 Chromatography Data System. Dopamine values were normalized to the internal standard dihydroxybenzylamine and compared with an external standard curve for quantification.

[35S]GTPγS binding assay.Membrane proteins were prepared according to the method described bySim et al. (1996). Three weeks after cocaine or saline pretreatment, the nucleus accumbens (core and shell) was removed and homogenized in 20 vol of buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, 3 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm EGTA, pH 7.4. The homogenate was centrifuged twice at 48,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min and resuspended in assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EGTA, and 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.4). Proteins were assayed by using the Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) DC protein assay and then stored at −80°C for binding assay.

The [35S]GTPγS binding assay was modified from the procedures described by Schaffhauser et al. (2000). Briefly, 12 × 75 mm polystyrene test tubes had 1 ml of assay buffer containing 30 μg of proteins, 30 μm GDP, 1 U of adenosine deaminase, 0.1 nm[35S]GTPγS (Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL), and various concentrations of baclofen (10−8 to 10−4m). Basal binding was measured in the absence of agonist, and nonspecific binding was measured in the presence of 10 μm unlabeled GTPγS. The reaction was then terminated by filtration under vacuum through Whatman (Maidstone, UK) GF/B glass fiber filters, followed by three washes with cold Tris-HCl buffer. After transfer of the filters into glass vials containing 10 ml of Ecolite scintillation fluid, the radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of three experiments, each performed in duplicate.

GABAB immunoblotting. Three weeks after the last daily injection of saline or cocaine, rats were decapitated, and the brains were rapidly removed and dissected into coronal sections on ice. The nucleus accumbens (containing both core and shell) was dissected on an ice-cooled Plexiglas plate using a 15 gauge tissue punch. Brain punches were immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until homogenized for immunoblotting.

The dissected brain punches were homogenized with a hand-held tissue grinder in a buffer containing 100 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μmpepstatin, 1 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitors, 1 mmiodoacetimide, 250 μm PMSF, sodium fluoride, sodium pyrophosphate, sodium orthovanadate, and okadaic acid. Insoluble materials were removed from lysates by centrifugation at 22,000 ×g for 20 min at 4°C. Protein determinations were performed using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Samples (30 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE (8%) using a mini-gel apparatus (Bio-Rad), transferred via semidry apparatus (Bio-Rad) to nitrocellulose membrane, and probed for the proteins of interest (one gel per protein per brain region). GABAB receptors were identified using a rabbit anti-rat antibody against GABAB1 (1:2000) or guinea pig anti-rat antibody against GABAB2receptor (1:2000) purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA) that was made against a peptide containing the C terminus of GABAB1or GABAB2 subunit. In control experiments, a synthesized peptide having the same 21 amino acid sequence on the C-terminal of GABAB1 was used to competitively inhibit the binding of antibody to GABAB1. Skeletal muscle extract was used as a negative control for GABAB2 receptor-specific detection. Labeled proteins were detected using an HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary IgG diluted 1:30,000 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) or goat anti-guinea pig secondary IgG diluted 1:10,000 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). Assurance of even transfer and equal amount of protein loading was evaluated with Ponceau S (Sigma), followed by destaining with de-ionized water, and the blots were reprobed with anti-calnexin (BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY). Blots were stripped (62.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, and 100 mm β-mercaptoethanol) for 30 min at 50°C, washed with PBS twice for 10 min, reblocked in 5% dry milk for 1 hr, and probed with anti-calnexin (1:2000; BD Transduction Laboratories), followed by goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000). In no gel did calnexin density indicate differences in protein loading (for representative calnexin immunostaining, see Fig. 6A). Immunoreactive levels were quantified by integrating band density × area using computer-assisted densitometry (NIH Image version 1.60). GABAB densities were divided by the corresponding calnexin densities. The resulting values were averaged over three control samples for each gel, and all bands were normalized as percentage of the control values.

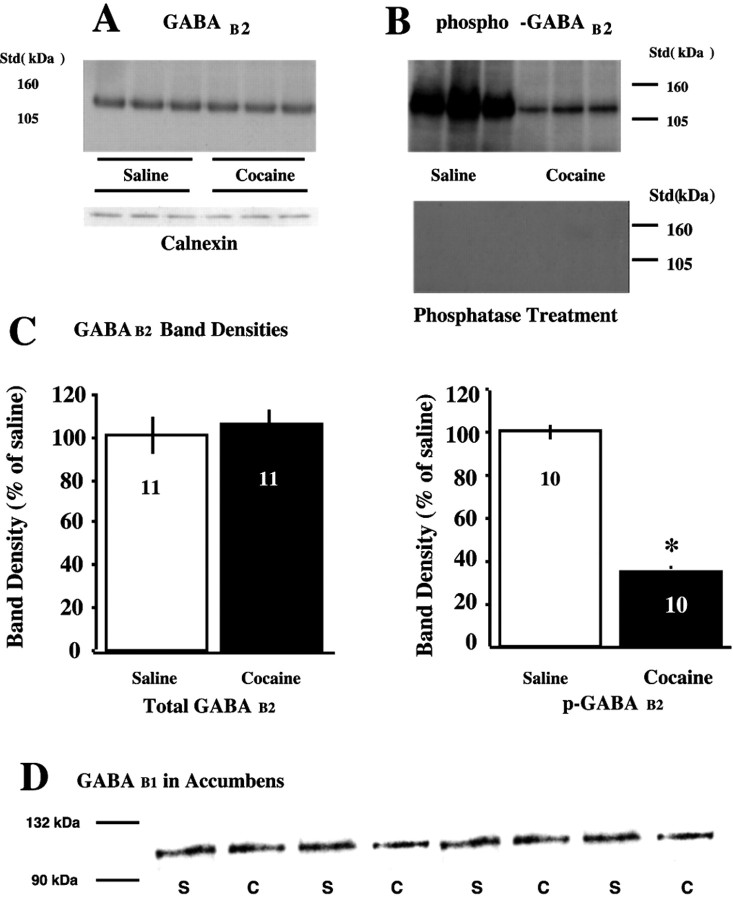

Fig. 6.

Cocaine treatment reduced p-GABAB2without altering total GABAB proteins. A, Representative immunoblots of GABAB2 total protein and reprobing for the loading control calnexin. B, Representative immunoblot of p-GABAB2 proteins using the same tissue as in A. The bottom blot is the top blot after incubation with phosphatase that eliminated immunoreactive staining of phosphorylated protein. C, Mean ± SEM percentage change from saline for total GABAB2 and p-GABAB2. D, Representative immunoblots of GABAB1 total protein showing no difference between treatment groups. *p < 0.05 comparing saline with cocaine treatment groups using a two-tailed Student's ttest.

Immunoprecipitation of GABAB2.Brain tissues were homogenized in cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing 100 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, and 1% sodium deoxycholate, supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μm pepstatin, 1 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitors, 1 mm iodoacetimide, and 250 μm PMSF). Phosphatase inhibitors such as sodium fluoride, sodium pyrophosphate, sodium orthovanadate, and okadaic acid were used in RIPA buffer to preserve the phosphorylation state of GABAB2 receptor proteins. Receptor proteins were immunoprecipitated from 400 μg of extract overnight at 4°C by the addition of the specific antibodies against GABAB2 (3 μg; Chemicon), followed by 3 hr incubation at 4°C with Protein A Sepharose beads (3 mg in 100 μl of RIPA buffer). The immunoprecipitates were washed three times with RIPA buffer, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted and subjected to SDS-PAGE (8%). Immunoblotting was performed using phospho (p)-Ser-specific monoclonal antibodies (1:1000; Chemicon). To verify that the identified band was a phosphoprotein, the blots were stripped as described above and incubated with phosphatase (5 U) in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 9.3, and 1 mm MgCl2 for 6 hr at 37°C. The blots were washed and probed with p-Ser antibody. Also, in a separate experiment, nucleus accumbens extracts from control subjects were treated with phosphatase (5 U) at 37°C for 6 hr, followed by immunoprecipitation and Western analysis with p-Ser antibody. The previously observed immunoreactivity of p-GABAB2 was absent, suggesting that assay is detecting p-GABAB2receptors. Immunoblots with p-Ser-specific antibodies from immunoprecipitated GABAB receptors were quantified using computer-assisted densitometry (NIH Image version 1.60).

Histology. After the dialysis experiments, rats were administered an overdose of pentobarbitol (>100 mg/kg, i.p.) and transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline, followed by 10% Formalin solution. Brains were removed and placed in 10% Formalin for at least 1 week to ensure proper fixation. The tissue was blocked, and coronal sections (100 μm thick) were made through the site of dialysis probe with a vibratome. The brains were then stained with cresyl violet to verify anatomical placement according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1986).

Statistical analysis. The StatView statistics package was used to estimate statistical significance. A one-way ANOVA with repeated measures over dose was used to determine the effect of individual drugs on extracellular dopamine, glutamate, or GABA levels. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures over time or dose was used to compare between treatments. During identification of statistical significance, post hoc comparisons were made with a Fischer's PLSD test.

Results

Cocaine withdrawal elevates the basal levels of extracellular GABA

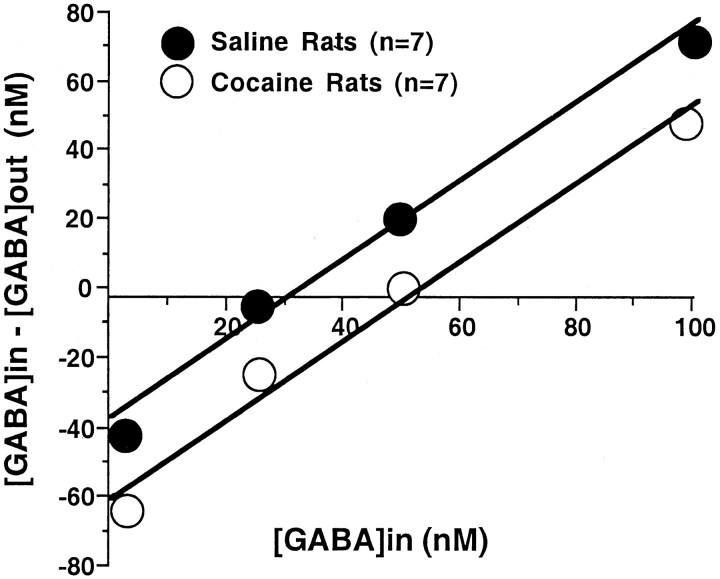

The in vivo basal levels of extracellular GABA in the nucleus accumbens were determined using no-net flux microdialysis (Parsons et al., 1991). After collecting five 20 min samples different concentrations of GABA (2.5 25, 50, 100 nm) were passed through the dialysis probe permitting extrapolation to the concentration of no net GABA flux across the dialysis membrane, which corresponds to the basal extracellular concentration. The slope of the line reflects the relative activity of processes eliminating GABA from the extracellular space by uptake, diffusion and enzymatic degradation. Figure 1 reveals a significant increase in the basal level of GABA from 32.7 ± 4.0 nm in saline rats to 50.3 ± 6.6 nm in cocaine-treated subjects after 3 weeks withdrawal. In contrast, the slopes of the two lines were statistically equivalent indicating no difference in GABA elimination from the extracellular space.

Fig. 1.

No-net flux microdialysis showing the increase in basal level of extracellular GABA in the accumbens in chronic cocaine- versus saline-treated rats. After collecting five 20 min baseline samples, 2.5, 25, 50, and 100 nm GABA was added to the dialysis buffer, and the net loss or gain in GABA in the collected dialysis buffer was quantified. The resulting linear equation estimates the basal level of extracellular GABA (concentration of no-net flux, i.e., y = 0) and the rate of elimination of GABA from the extracellular space (i.e., the slope of the line) in each subject (Parsons et al., 1991). The average of the basal levels of extracellular GABA was significantly increased in chronic cocaine-treated rats (32.7 ± 4.0 in saline-treated rats vs 50.3 ± 6.6 in cocaine-treated rats; a two-tail Student'st test; p < 0.05), whereas the elimination rates of GABA from extracellular space (the slopes) were not different (1.14 ± 0.08 in saline-treated rats vs 1.19 ± 0.05 in chronic cocaine-treated rats).

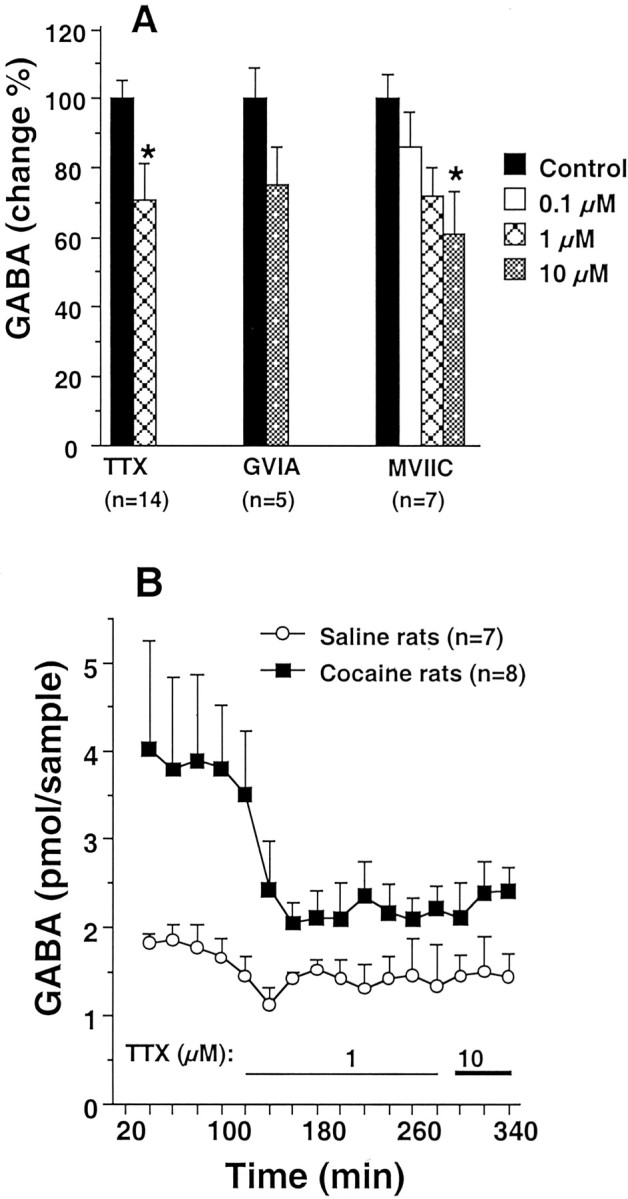

Increased extracellular GABA by chronic cocaine is from neurons

To determine the source of the extracellular GABA, voltage-dependent ion channel blockers were infused into the nucleus accumbens. Figure 2Ashows that blockade of the voltage-dependent Na+ channel by TTX (1 μm) or Ca2+channels by either ω-conotoxin GVIA (N-type blocker) or ω-conotoxin MVIIC (P/Q-type blocker) lowered the basal levels of extracellular GABA by ∼25%. This is consistent with other studies showing that the majority of extracellular GABA measured by microdialysis was not derived from neuronal or vesicular pools (for review, see Timmerman and Westerink, 1997).

Fig. 2.

Blockade of the voltage-dependent Na+ channels markedly reduces the elevated GABA levels measured after repeated cocaine treatment. Ashows that the basal levels of extracellular GABA in control subjects is only marginally reduced by TTX (Na+ channel blocker), ω-conotoxin GVIA (GVIA; N-type Ca2+channel blocker), or ω-conotoxin MVIIC (MVIIC; P/Q-type Ca2+ channel blocker). The value in each column represents the average of three 20 min dialysis samples collected for each drug or dose. B shows that blockade of the voltage-dependent Na+ channels by TTX reversed the increase in extracellular GABA observed in chronic cocaine-treated rats. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements revealed a significant difference between the treatment (chronic saline vs cocaine) (F(1,12) = 6.62; p= 0.025) and a significant interaction between treatment and time (F(16,192) = 3.85;p = 0.0001). *p < 0.05 compared with the average of the baseline samples (Control).

In contrast to the basal levels of extracellular GABA in control subjects, Figure 2B shows that the elevated extracellular GABA associated with cocaine-treated subjects was reduced substantially by 1 μm TTX and approached the level of extracellular GABA in control subjects. Increasing the dose from 1 to 10 μm TTX failed to produce additional reductions in extracellular GABA in either treatment group.

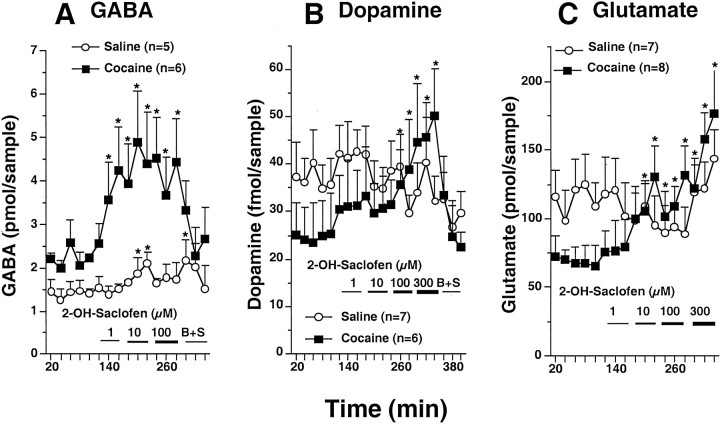

Enhanced GABA tone on GABAB autoreceptors and heteroreceptors by chronic cocaine

Figure 3 shows that reverse dialysis of the GABAB receptor antagonist 2-OH-saclofen into the accumbens elevated the extracellular content of GABA, dopamine, and glutamate in cocaine-treated rats. In contrast, in saline-treated subjects, much lower GABA tone was evident on GABAB presynaptic receptors. Reverse dialysis of 2-OH-saclofen produced no effect on the extracellular levels of dopamine or glutamate in control animals, whereas relatively small increases were measured in extracellular GABA. The repeated cocaine treatment group had elevated basal levels of GABA (1.40 ± 0.23 pmol/sample for saline; 2.22 ± 0.24 for cocaine;p < 0.05) and reduced basal levels of extracellular glutamate (115.4 ± 20.4 pmol/sample for saline; 72.6 ± 12.6 for cocaine; p < 0.05). In contrast the basal levels of dopamine were not significantly altered by repeated cocaine (36.8 ± 6.0 fmol/sample for saline; 25.6 ± 7.6 for cocaine).

Fig. 3.

Blockade of GABAB receptors by 2-OH-saclofen produced an enhanced elevation of extracellular GABA (A), dopamine (B), and glutamate (C) in the nucleus accumbens of chronic cocaine-treated rats. Increasing concentrations of 2-OH-saclofen were added to the dialysis buffer, and, in some experiments, 300 μm baclofen was added to the final concentration of 2-OH-saclofen to reverse the GABAB receptor blockade (B+S). A two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements over dose reveals a significant effect of baclofen dose (F(16,128) = 3.44,p = 0.0001 for GABA in A;F(16,126) = 2.14, p= 0.005 for dopamine in B; andF(19,247) = 6.59, p= 0.0001 for glutamate in C) and a time × treatment interaction for GABA (F(16,144) = 2.66;p = 0.001), dopamine (F(19,190) = 1.89;p = 0.017), or glutamate (F(19,247) = 2.07;p = 0.0063). *p < 0.05 compared with the average of the last three baseline samples using a PLSD post hoc comparison.

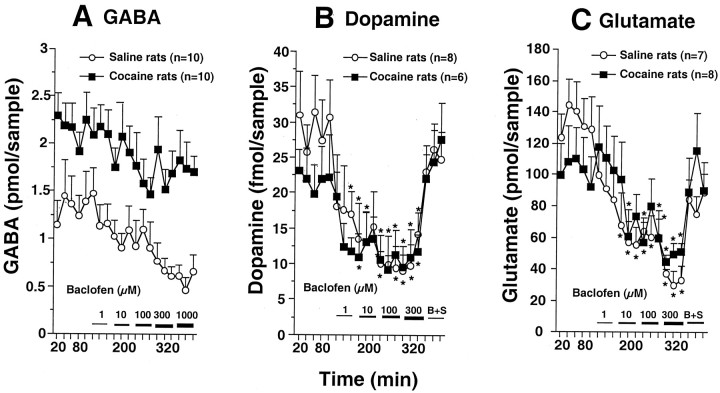

In contrast to the differential effects produced by antagonizing GABAB autoreceptors and heteroreceptors in repeated cocaine and saline animals, stimulating GABAB receptors with baclofen produced approximately equivalent reductions in the extracellular content of GABA, glutamate, or dopamine in both treatment groups (Fig.4). The basal levels of extracellular GABA were significantly elevated in the repeated cocaine group (1.30 ± 0.29 pmol/sample for saline; 2.16 ± 0.24 for cocaine; p < 0.05), whereas the basal levels of neither glutamate (135.6 ± 17.8 pmol/sample for saline; 102.8 ± 20.2 for cocaine) nor dopamine (28.2 ± 5.2 fmol/sample for saline; 22.8 ± 4.4 for cocaine) were significantly affected.

Fig. 4.

Effects of activation of GABABreceptors by reverse dialysis of baclofen on nucleus accumbens levels of GABA, dopamine, and glutamate in chronic saline- and cocaine-treated rats. Increasing concentrations of baclofen were added to the dialysis buffer, and, in some experiments, 300 μm 2-OH-saclofen was added to the final concentration of baclofen to block the stimulation of GABAB receptors (B+S). A, Baclofen produced parallel effects on GABA in both treatment groups. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures showed a significant difference between treatment (chronic saline vs cocaine;F(1,13) = 15.45; p= 0.0017) and over dose (F(16,208) = 2.03; p = 0.0128) but no time × treatment interaction (F(16,208) = 0.373;p = 0.987). B, Baclofen significantly decreased extracellular dopamine levels in both groups of rats. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measurement shows a significant difference over dose (F(17,204) = 8.05;p = 0.0001) but no difference between treatments (F(1,12) = 0.48; p= 0.51) or a time × treatment interaction (F(17,204) = 0.654;p = 0.845). C, Baclofen similarly decreased extracellular glutamate levels in both the saline- and cocaine-treated groups. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements shows a significant difference over dose (F(19,247) = 5.42;p = 0.0001) but no effect of treatment (F(1,13) = 0.1; p = 0.98) or the time × treatment interaction (F(19,247) = 1.09;p = 0.366). *p < 0.05 compared with the average of the last three of the five baseline samples.

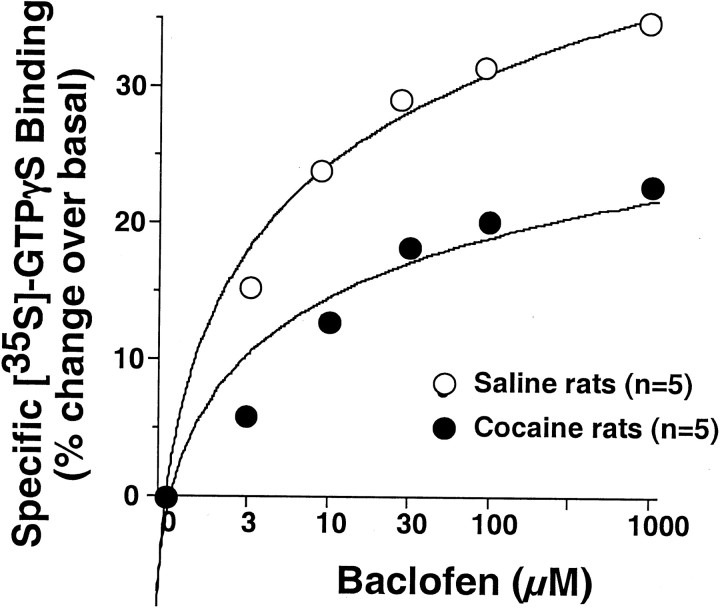

Repeated cocaine reduces the functional capacity of GABAB receptors

Elevated levels of extracellular GABA could arise from desensitization of GABAB receptors. To evaluate this possibility, the coupling of GABAB receptors to intracellular G-proteins was determined by measuring baclofen-stimulated GTPγS binding in membranes obtained from the accumbens of cocaine- and saline-treated rats. Figure5 shows that baclofen elicited a dose-dependent increase in [35S]GTPγS binding to G-proteins in both saline- and cocaine-treated rats. However, the maximum stimulation of binding was significantly reduced in the cocaine-treated subjects.

Fig. 5.

Chronic cocaine treatment decreased the baclofen-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding to G-proteins in the nucleus accumbens. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements revealed a significant effect of repeated cocaine treatment (F(5,40) = 2.79;p = 0.029).

GABAB1 and GABAB2 receptors

Figure 6A shows a representative immunoblot of GABAB2 protein in the nucleus accumbens. There was no significant difference in the levels of total GABAB2 protein between the cocaine and saline treatment groups (Fig. 6C). Similar to observations made by Couve et al. (2002) in neuronal cultures, the GABAB2 receptor is substantially Ser-phosphorylated in vivo. Cocaine treatment markedly reduced the amount of Ser-phosphorylated GABAB2(p-GABAB2) measured in the nucleus accumbens (Fig. 6B,C). Figure6B also shows the results of reprobing the blot with p-Ser antibody after stripping and incubating with phosphatase. The lack of immunostaining verifies that the original staining was a phosphoprotein.

Akin to the GABAB2 subunit, there was no difference in total GABAB1 protein content between saline- and cocaine-treated subjects (Fig.6D). The amount of p-GABAB1 was not sufficient to quantify in either cocaine or saline animals (data not shown).

Histology

All dialysis probe placements used for data analysis had >50% of the active membrane within the boundaries of the nucleus accumbens, as defined by Paxinos and Watson (1986). The probe placements were generally at the interface between the core and shell compartments of the nucleus accumbens. When a portion of the probe was outside the nucleus accumbens, it was in the ventrolateral septum, ventromedial diagonal band of Broca, or ventromedial striatum.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that, 3 weeks after discontinuing treatment with repeated cocaine injections, the basal level of extracellular GABA in the nucleus accumbens is increased. Because the Na+ channel blocker TTX substantially reduced the increase in basal extracellular GABA, the majority of the increase in cocaine-treated subjects is derived from a neuronal source. Moreover, the increase in extracellular GABA may be derived in part from the functional uncoupling of GABABautoreceptors, perhaps attributable to reduced Ser phosphorylation of the GABAB2 receptor subtype.

The origin of extracellular GABA in the accumbens

Confirming work by others (for review, see Timmerman and Westerink, 1997), extracellular GABA levels in control subjects were found to be derived primarily from Na+- and Ca2+-insensitive, presumably nonsynaptic, sources. However, the portion of extracellular GABA that was increased after repeated cocaine was exquisitely sensitive to blockade of Na+ channels, indicating primarily action potential-dependent, neuronal origin. Moreover, identical slopes in the no-net flux study indicate the involvement of release rather than elimination of GABA in mediating the increased levels (Parsons et al., 1991). Further supporting the role of release mechanisms, repeated cocaine administration does not alter GABA synthesis or presynaptic GABA content in the accumbens (Sorg et al., 1995; Meshul et al., 1998).

There are three potential neuronal sources of extracellular GABA in the accumbens. The majority of the accumbens neurons are medium-sized spiny GABAergic projection cells that possess extensive recurrent collaterals (Smith and Bolam, 1990; Pennartz et al., 1994). In addition, the accumbens contains ∼5% medium-sized aspiny GABAergic interneurons. Because these interneurons fire at a relatively high frequency (Kawaguchi et al., 1995), they may also contribute to extracellular GABA. Finally, GABAergic afferents from other brain nuclei, such as the ventral tegmental area, olfactory nucleus, and ventral pallidum, can contribute to extracellular GABA in the accumbens (Brog et al., 1993). Which of these potential sources of extracellular GABA that may be affected by repeated cocaine administration cannot be defined by microdialysis. Although spiny cells are thought to undergo a number of cocaine-induced neuroadaptations that could promote transmitter release, such as increased PKA and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II signaling (Gnegy, 2001; Nestler, 2001), electrophysiological studies indicate that the spiny cells may be relatively hyperpolarized and less active after repeated psychostimulant administration (Zhang et al., 1998; Thomas et al., 2001). Although this may signify less contribution by spiny cell recurrent collaterals, cocaine-induced neuroadaptations in dopamine-regulated GABA release in the ventral tegmental area could stimulate the activity of GABAergic neurons projecting to the accumbens (Bonci and Williams, 1996).

Elevating basal extracellular GABA increases tone on GABAB presynaptic receptors

Consistent with functionally significant elevations in extracellular GABA by repeated cocaine, blockade of GABAB autoreceptors and heteroreceptors caused an augmented increase in the extracellular levels of GABA, dopamine, and glutamate in the accumbens of cocaine-treated rats. These data not only support the presence of increased GABA tone on GABAB receptors but also provide in vivo evidence that the accumulation of extracellular GABA after withdrawal from repeated cocaine can influence near-adjacent heterosynapses to tonically inhibit the release of other neurotransmitters (for review of in vitro evidence, seeIsaacson, 2000). Similar to this finding, Giorgetti et al. (2002)recently found that chronic amphetamine treatment increased GABAergic tone on GABAB receptors regulating extracellular glutamate and dopamine in the ventral tegmental area. These studies suggest that increased GABA release could be a relatively prevalent feature of psychostimulant abuse and offers an explanation for the widespread reduction in basal metabolic activity produced in brain by repeated psychostimulants in both experimental animals and human addicts (Volkow et al., 1993; Breiter et al., 1997; London et al., 1999).

Although the enhanced capacity of GABAB receptor blockade to elevate extracellular GABA indicates that the GABAB receptors are functional and may not be desensitized, repeated or prolonged exposure to agonist often desensitizes the responsiveness of G-protein-coupled receptors by altering receptor density, conformation, or trafficking (for review, see Tsao and von Zastrow, 2000; Ferguson, 2001). The present study demonstrated a decrease in baclofen-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the accumbens that was associated with increased extracellular GABA levels. This observation is consistent with the finding that repeated amphetamine caused a reduction in GABAB coupling to Giα in the nucleus accumbens, indicating that GABAB receptors may be desensitized (Zhang et al., 2000). The total protein content of GABAB1or GABAB2 receptors was unaltered in the cocaine group, indicating that changes in overall protein synthesis or degradation are not mediating the apparent desensitization. Similarly, a previous study found no significant alteration in GABAB1 receptor protein in repeated cocaine-treated rats (Li et al., 2001). However, GABAB1 forms a heterodimer with GABAB2 to make an active receptor (Bowery and Enna, 2000), and, although p-GABAB1 protein could not be detected in either the saline or cocaine treatment groups, a marked reduction in the amount of p-GABAB2 was measured in the cocaine group.

Reduced Ser phosphorylation of GABAB2 after repeated cocaine

Reduced Ser phosphorylation of GABABreceptors by PKA or PKC has been shown to both promote (Kamatchi and Ticku, 1990; Taniyama et al., 1992) and desensitize (Couve et al., 2002) GABAB receptor-mediated effects. The present findings are most consistent with the study by Couve et al. (2002) demonstrating that dephosphorylation of Ser892 in the cytoplasmic tail of GABAB2 mediates desensitization of GABAB receptor coupling to K+ channels and that GABAB agonists inhibit PKA, thereby promoting GABAB dephosphorylation and desensitization. Thus, the increase in extracellular GABA after cocaine withdrawal would be expected to decrease p-GABAB2 and thereby desensitize baclofen stimulation of GTPγS binding and presynaptic transmitter release. These data appear contradictory to the general consensus that repeated psychostimulant administration increases PKA signaling (for review, see Nestler, 2001). However, it is possible that the intracellular microdomain in the vicinity of GABAB receptors may not reflect whole-cell PKA activity. For example, an upregulation of whole-cell PKA by chronic cocaine may facilitate vesicular GABA release (Greengard et al., 1993;Trudeau et al., 1996), providing a source of the increased GABA tone on GABAB autoreceptors. However, GABAB receptors are Gicoupled, and increased tone on GABAB receptors will inhibit PKA in the vicinity of the receptor, thereby reducing GABAB receptor phosphorylation, desensitizing GABAB receptors, and further facilitating GABA release.

Repeated cocaine effects on GABAB heteroreceptors

Although the GTPγS binding assay cannot distinguish between GABAB autoreceptors and heteroreceptors, the dialysis study indicates that, similar to autoreceptors, the heteroreceptors regulating extracellular glutamate and dopamine levels are affected by repeated cocaine. Thus, akin to GABA autoreceptors, the cocaine-induced elevation in extracellular GABA provided increased GABAergic tone on heteroreceptors regulating glutamate and dopamine release. In one of the experiments, the basal levels of extracellular glutamate were reduced after repeated cocaine. A reduction in extracellular glutamate in the accumbens after repeated cocaine has been previously reported (Pierce et al., 1996; Bell et al., 2000;Hotsenpillar et al., 2001), and blocking GABABreceptors appeared to normalize the levels of glutamate in cocaine animals to the levels measured in saline animals (Fig. 3C). Basal extracellular glutamate content is derived primarily from the exchange of extracellular cystine with intracellular glutamate (Baker et al., 2002), posing the possibility that GABABreceptors may regulate extracellular glutamate in part by inhibiting cystine–glutamate exchange. Indeed, the activity of the exchanger is inhibited by reducing PKA activity (Baker et al., 2002).

Conclusions

After 3 weeks of withdrawal from repeated cocaine administration, there is an increase in extracellular GABA in the nucleus accumbens that is derived primarily from neuronal sources. The elevated extracellular GABA provides a corresponding increase in tone to GABAB autoreceptors and heteroreceptors that regulates the extracellular levels of GABA, glutamate, and dopamine. The increased tone to GABAB receptors decreases p-GABAB2, which may account for the desensitization of GABAB receptors, and contributes to the previously observed decrease in basal extracellular levels of glutamate in the accumbens of cocaine-treated animals (Pierce et al., 1996; Bell et al., 2000; Hotsenpillar et al., 2001). Decreased striatal GABAA receptor function or subunit composition has also been induced by repeated cocaine in some (Peris, 1996; Suzuki et al., 2000) but not all (Goeders, 1991) studies. This poses the possibility that increased extracellular GABA may downregulate GABAA as well as GABAB receptor function. Given the integral role in addiction that has been postulated for neuroadaptations in accumbens GABAergic spiny cells (Nestler, 2001; Everitt and Wolf, 2002), the elevation of extracellular GABA and corresponding impact on neurotransmission regulated by GABAB receptors may constitute a functionally important step in the development or expression of behaviors associated with psychostimulant addiction.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by United States Public Health Service Grants MH-40817 (P.W.K.), DA-03906 (P.W.K.), and MH-62612 (S.R.).

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Peter Kalivas, Department of Physiology and Neuroscience, Medical University of South Carolina, 173 Ashley Avenue, Suite BSB 403, Charleston, SC 29425. E-mail:kalivasp@musc.edu.

References

- 1.Baker DA, Xi Z-X, Shen H, Swanson CJ, Kalivas PW. The primary source and neuronal function of in vivo extracellular glutamate. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9134–9141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-09134.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell K, Duffy P, Kalivas PW. Context-specific enhancement of glutamate transmission by cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:335–344. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonci A, Williams JT. A common mechanism mediates long-term changes in synaptic transmission after chronic cocaine and morphine. Neuron. 1996;16:631–639. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowery NG, Enna SJ. γ-Aminobutyric acidB receptors: first of the functional metabotropic heterodimers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breiter HC, Gollub RL, Weisskoff RM, Kennedy DN, Makris N, Berke JD, Goodman JM, Kantor HL, Gasfriend DR, Riorden JP, Mathew RT, Rosen BR, Hyman SE. Acute effects of cocaine on human brain activity and emotion. Neuron. 1997;19:591–611. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brog JS, Salyapongse A, Deutch AY, Zahm DS. The patterns of afferent innervation of the core and shell in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum: immunohistochemical detection of retrogradely transported fluoro-gold. J Comp Neurol. 1993;338:255–278. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couve A, Thomas P, Calver AR, Hirst WD, Pangalos MN, Walsh FS, Smart TG, Moss SJ. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation facilitates GABAB receptor-effector coupling. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:415–424. doi: 10.1038/nn833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everitt BJ, Wolf ME. Psychomotor stimulant addiction: a neural systems perspective. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3312–3320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03312.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferguson SS. Evolving concepts in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis: the role in receptor desensitization and signaling. Pharmacol Rev 53 2001. 1 24 Rev. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giorgetti M, Hotsenpiller G, Froestl W, Wolf ME. In vivo modulation of ventral tegmental area dopamine and glutamate efflux by local GABAB receptors is altered after repeated amphetamine treatment. Neuroscience. 2002;109:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnegy ME. Ca2+/calmodulin signaling in NMDA-induced synaptic plasticity. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2001;14:91–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goeders NE. Cocaine differentially affects benzodiazepine recptoers in discrete regions of rat brain: persistence and potential mechanisms mediating these effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259:574–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greengard P, Valtorta F, Czernik AJ, Benfenati F. Synaptic vesicle phosphoproteins and regulation of synaptic function. Science. 1993;259:780–785. doi: 10.1126/science.8430330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harsing LG, Zigmond MJ. Influence of dopamine on GABA release in striatum: evidence for D1–D2 interactions and non-synaptic influences. Neuroscience. 1997;77:419–429. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hotsenpiller G, Giorgetti M, Wolf ME. Alterations in behaviour and glutamate transmission following presentation of stimuli previously associated with cocaine exposure. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1843–1855. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isaacson JS. Synaptic transmission: spillover in the spotlight. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R475–R477. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamatchi GL, Ticku MK. Functional coupling of presynaptic GABAB receptors with voltage-gated Ca++ channel: regulation by protein kinase A and C in cultured spinal neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;38:342–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawaguchi Y, Wilson CJ, Augood SJ, Emson PC. Striatal interneurons: chemical physiological and morphological characterization. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:527–535. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)98374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Olinger AB, Dassow MS, Abel MS. GABA(B) receptor gene expression is not altered in cocaine-sensitized rats. J Neurosci Res. 2001;68:241–247. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.London ED, Bonson KR, Ernst M, Grant S. Brain imaging studies of cocaine abuse: implications for medication development. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1999;13:227–242. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v13.i3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meshul CK, Noguchi K, Emre N, Ellison G. Cocaine-induced changes in glutamate and GABA immunolabeling within rat habenula and nucleus accumbens. Synapse. 1998;30:211–220. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199810)30:2<211::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nestler EJ. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:119–128. doi: 10.1038/35053570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parsons LH, Smith AD, Justice JB., Jr Basal extracellular dopamine is decreased in the rat nucleus accumbens during abstinence from chronic cocaine. Synapse. 1991;9:60–65. doi: 10.1002/syn.890090109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic; New York: 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pennartz CM, Groenewegen HJ, Lopes da Silva FH. The nucleus accumbens as a complex of functionally distinct neuronal ensembles: an integration of behavioural, electrophysiological and anatomical data. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;42:719–761. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peris J. Repeated cocaine injections decrease the function of striatal GABAA receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:1002–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierce RC, Bell K, Duffy P, Kalivas PW. Repeated cocaine augments excitatory amino acid transmission in the nucleus accumbens only in rats having developed behavioral sensitization. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1550–1560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01550.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson TE, Whishaw IQ. Normalization of extracellular dopamine in striatum following recovery from a partial unilateral 6-OHDA lesion of the substantia nigra: a microdialysis study in freely moving rats. Brain Res. 1988;450:209–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91560-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaffhauser H, Cai Z, Hubalek F, Macek TA, Pohl J, Murphy TJ, Conn PJ. cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits mGluR2 coupling to G-proteins by direct receptor phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5663–5670. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05663.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoffelmeer A, Vanderschuren L, De Vries T, Hogenboom F, Wardeh G, Mulder A. Synergistically interacting dopamine D1 and NMDA receptors mediate nonvesicular transporter-dependent GABA release from rat striatal medium spiny neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3496–3503. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03496.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sesack SR, Pickel VM. In the rat medial nucleus accumbens, hippocampal and catecholaminergic terminals converge on spiny neurons and are in apposition to each other. Brain Res. 1990;527:266–279. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shoji S, Simm D, McDaniel WC, Gallagher JP. Chronic cocaine enhances γ-aminobutyric acid and glutamate release by altering presynaptic and not postsynaptic gamma-aminobutyric acidB receptors within the rat dorsolateral septal nucleus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sim LJ, Selley DE, Dworkin SI, Childers SR. Effects of chronic morphine administration on mu opioid receptor-stimulated [35S]GTPγS autoradiography in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2684–2692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02684.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith AJ, Bolam JP. The neural network of the basal ganglia as revealed by the study of synaptic connections of identified neurons. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:259–265. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90106-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorg BA, Guminski BJ, Hooks MS, Kalivas PW. Cocaine alters glutamic acid decarboxylase differentially in the nucleus accumbens core and shell. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;29:381–386. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00281-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki T, Abe S, Yamaguchi M, Bab A, Hori T, Shiraishi H, Ito T. Effects of cocaine administration on receptor binding and subunits mRNA of GABAA-benzodiazepine receptor complexes. Synapse. 2000;38:198–215. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200011)38:2<198::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taniyama K, Niwa M, Kataoka Y, Yamashita K. Activation of protein kinase C suppresses the γ-aminobutyric acid B receptor-mediated inhibition of the vesicular release of noradrenaline and acetylcholine. J Neurochem. 1992;58:1239–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb11334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas MJ, Beurrier C, Bonci A, Malenka RC. Long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens: a neural correlate of behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1217–1223. doi: 10.1038/nn757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Timmerman W, Westerink BHC. Brain microdialysis of GABA and glutamate: what does it signify? Synapse. 1997;27:242–261. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199711)27:3<242::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trudeau LE, Emery DG, Haydon PG. Direct modulation of the secretory machinery underlies PKA-dependent synaptic facilitation in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1996;17:789–797. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsao P, von Zastrow M. Downregulation of G protein-coupled receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiology. 2000;10:365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vanderschuren LJ, Kalivas PW. Alterations in dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization: a critical review of preclinical studies. Psychopharmacology. 2000;151:99–120. doi: 10.1007/s002130000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Hitzemann R, Logan J, Schyler DJ, Dewey SL, Wolf AP. Decreased dopamine D2 receptor availability is associated with reduced frontal metabolism in cocaine abusers. Synapse. 1993;14:167–177. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White FJ, Kalivas PW. Neuroadaptations involved in amphetamine and cocaine addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:141–154. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolf ME. The role of excitatory amino acids in behavioral sensitization to psychomotor stimulants. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;54:679–720. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang K, Tarazi FI, Campbell A, Baldessarini RJ. GABA(B) receptors: altered coupling to G-proteins in rats sensitized to amphetamine. Neuroscience. 2000;101:5–10. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00344-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang XF, Hu XT, White FJ. Whole-cell plasticity in cocaine withdrawal: reduced sodium current in nucleus accumbens neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:488–498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00488.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]